Mary Phelps Jacob on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Caresse Crosby (born Mary Phelps Jacob; April 20, 1892 – January 24, 1970) was the recipient of a patent for the first successful modern

Crosby filed for a patent for her invention on February 12, 1914, and in November that year the

Crosby filed for a patent for her invention on February 12, 1914, and in November that year the

On September 9, 1922, Harry reached New York aboard the ''Aquitania''. Polly met him at the customs barrier, and they were married in the Municipal Building in New York City that afternoon. Two days later, they re-boarded the ''Aquitania'' and moved with her children to

On September 9, 1922, Harry reached New York aboard the ''Aquitania''. Polly met him at the customs barrier, and they were married in the Municipal Building in New York City that afternoon. Two days later, they re-boarded the ''Aquitania'' and moved with her children to

Caresse and Harry published her first book, ''Crosses of Gold'', in late 1924. It was a volume of conventional, "unadventurous" poetry centering on themes such as love, beauty, and her husband.

In 1926 they published her second book, ''Graven Images,'' with

Caresse and Harry published her first book, ''Crosses of Gold'', in late 1924. It was a volume of conventional, "unadventurous" poetry centering on themes such as love, beauty, and her husband.

In 1926 they published her second book, ''Graven Images,'' with

In 1949 during a tour of Italy, she saw a run-down castle, Castello di Rocca Sinibalda, north of Rome.

In 1949 during a tour of Italy, she saw a run-down castle, Castello di Rocca Sinibalda, north of Rome.

Caresse Crosby: From Black Sun to Roccasinibalda

Open Road. New York. . * * *

Mary Phelps Jacob (Caresse Crosby)

at Phelps Family History

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20031211085100/http://www.cosmicbaseball.com/caresse8.html "Caresse Crosby, Infield." Cosmic Baseball Association, 1998 (December 2003)

Mary Phelps Jacob, Inventor of the Modern Brassiere

Caresse Crosby Papers

at Southern Illinois University Carbondale Special Collections Research Center

* (Video) ''This article was based upon material originally written by Brian Phelps and licensed for use in Wikipedia under the

bra

A bra, short for brassiere or brassière (, ; ), is a type of form-fitting underwear that is primarily used to support and cover a woman's breasts. A typical bra consists of a chest band that wraps around the torso, supporting two breast cups ...

, an American patron of the arts, a publisher, and the woman ''Time

Time is the continuous progression of existence that occurs in an apparently irreversible process, irreversible succession from the past, through the present, and into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequ ...

'' called the "literary godmother to the Lost Generation

The Lost Generation was the Demography, demographic Cohort (statistics), cohort that reached early adulthood during World War I, and preceded the Greatest Generation. The social generation is generally defined as people born from 1883 to 1900, ...

of expatriate writers in Paris." She and her second husband, Harry Crosby, founded the Black Sun Press, which was instrumental in publishing some of the early works of many authors who would later become famous, among them Anaïs Nin

Angela Anaïs Juana Antolina Rosa Edelmira Nin y Culmell ( ; ; February 21, 1903 – January 14, 1977) was a French-born American diarist, essayist, novelist, and writer of short stories and erotica. Born to Cuban parents in France, Nin was the d ...

, Kay Boyle

Kay Boyle (February 19, 1902 – December 27, 1992) was an American novelist, short story writer, educator, and political activist. Boyle is best known for her fiction, which often explored the intersections of personal and political themes. Her ...

, Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Miller Hemingway ( ; July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961) was an American novelist, short-story writer and journalist. Known for an economical, understated style that influenced later 20th-century writers, he has been romanticized fo ...

, Archibald MacLeish

Archibald MacLeish (May 7, 1892 – April 20, 1982) was an American poet and writer, who was associated with the modernist school of poetry. MacLeish studied English at Yale University and law at Harvard University. He enlisted in and saw action ...

, Henry Miller

Henry Valentine Miller (December 26, 1891 – June 7, 1980) was an American novelist, short story writer and essayist. He broke with existing literary forms and developed a new type of semi-autobiographical novel that blended character study, so ...

, Charles Bukowski

Henry Charles Bukowski ( ; born Heinrich Karl Bukowski, ; August 16, 1920 – March 9, 1994) was a German Americans, German-American poet, novelist, and short story writer. His writing was influenced by the social, cultural, and economic ambien ...

, Hart Crane

Harold Hart Crane (July 21, 1899 – April 27, 1932) was an American poet. Inspired by the Romantics and his fellow Modernists, Crane wrote highly stylized poetry, often noted for its complexity. His collection '' White Buildings'' (1926), feat ...

, and Robert Duncan.

Early life and education

Born on April 20, 1891, inNew Rochelle, New York

New Rochelle ( ; in ) is a Political subdivisions of New York State#City, city in Westchester County, New York, Westchester County, New York (state), New York, United States. It is a suburb of New York City, located approximately from Midtow ...

, she was the oldest child of Mary (née Phelps) Jacob and William Hearn Jacob, who were both descended from American colonial families—her mother from the William Phelps family, and her father from the Van Rensselaers. Her mother was the daughter of Civil War General Walter Phelps, and she had two brothers, Leonard and Walter "Bud" Phelps Jacob. She was nicknamed "Polly" to distinguish her from her mother.

Polly's family was not fabulously rich, but her father had been raised, as she put it, "to ride to hounds, sail boats, and lead cotillions," and he lived extravagantly. In 1914, the family presented her to the King of England

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the form of government used by the United Kingdom by which a hereditary monarch reigns as the head of state, with their powers Constitutional monarchy, regula ...

at a garden party. In keeping with the American aristocratic style of the times, she was even photographed as a child by Charles Dana Gibson

Charles Dana Gibson (September 14, 1867 – December 23, 1944) was an American illustrator who created the Gibson Girl, an iconic representation of the beautiful and independent American woman at the turn of the 20th century.

He published his ...

, for whom the iconic term "Gibson girl" was coined.

She grew up, she later said, "in a world where only good smells existed. What I wanted usually came to pass." She was an uninterested student. Author Geoffrey Wolff wrote that for the most part Polly "lived her life in dreams."

Her family divided its time between estates in Manhattan

Manhattan ( ) is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the Boroughs of New York City, five boroughs of New York City. Coextensive with New York County, Manhattan is the County statistics of the United States#Smallest, larg ...

at 59th Street 59th Street station may refer to:

*59th Street (BMT Fourth Avenue Line) in Brooklyn, New York; serving the trains

* 59th Street (IRT Third Avenue Line) a demolished elevated station in Manhattan

* 59th Street (IRT Ninth Avenue Line) a demolished e ...

and Fifth Avenue

Fifth Avenue is a major thoroughfare in the borough (New York City), borough of Manhattan in New York City. The avenue runs south from 143rd Street (Manhattan), West 143rd Street in Harlem to Washington Square Park in Greenwich Village. The se ...

, in Watertown, Connecticut

Watertown is a town in Litchfield County, Connecticut, United States. The town is part of the Naugatuck Valley Planning Region. The population was 22,105 at the 2020 census. It is a suburb of Waterbury. The urban center of the town is the Wat ...

, and in New Rochelle, New York, and she enjoyed the advantages of an upper-class lifestyle. She attended formal balls, Ivy League

The Ivy League is an American collegiate List of NCAA conferences, athletic conference of eight Private university, private Research university, research universities in the Northeastern United States. It participates in the National Collegia ...

school dances, and received equestrian training at a horse riding school. She studied dance at the studio of composer and society tastemaker Allen Dodsworth, attended Miss Chapin's School

Chapin School is an all-girls independent day school on Manhattan's Upper East Side neighborhood in New York City.

History

Maria Bowen Chapin opened "Miss Chapin's School for Girls and Kindergarten for Boys and Girls" in 1901. The school or ...

in New York City, and then boarded at Rosemary Hall, a prep school in Wallingford, Connecticut

Wallingford is a town in New Haven County, Connecticut, New Haven County, Connecticut, United States, centrally located between New Haven, Connecticut, New Haven and Hartford, Connecticut, Hartford, and Boston and New York City. The town is part ...

that later merged to form Choate Rosemary Hall

Choate Rosemary Hall ( ) is a Independent school, private, Mixed-sex education, co-educational, College-preparatory school, college-preparatory boarding school in Wallingford, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1890, it took its present na ...

, where she played the part of Rosalind in ''As You Like It

''As You Like It'' is a pastoral Shakespearean comedy, comedy by William Shakespeare believed to have been written in 1599 and first published in the First Folio in 1623. The play's first performance is uncertain, though a performance at Wil ...

'' to critical acclaim.

After her father's death in 1908, she lived with her mother at their home in Watertown, Connecticut. That same year she met her future husband, Richard Peabody, at summer camp. Her brother Len was boarding at Westminster School

Westminster School is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school in Westminster, London, England, in the precincts of Westminster Abbey. It descends from a charity school founded by Westminster Benedictines before the Norman Conquest, as do ...

, and Bud was a day student at Taft School

The Taft School is a private coeducational school located in Watertown, Connecticut, United States. It enrolls approximately 600 students in grades 9–12.

Overview

History

The school was founded in 1890 as Mr. Taft's School (renamed t ...

. Approaching her own debut, she danced in balls most nights, and slept from four in the morning until noon. "At twelve I was called and got ready for the customary debutante

A debutante, also spelled débutante ( ; from , ), or deb is a young woman of aristocratic or upper-class family background who has reached maturity and is presented to society at a formal "debut" ( , ; ) or possibly debutante ball. Origin ...

luncheon." She graduated from Rosemary Hall in 1910, at age 19.

Development of the backless brassiere

That same year, Crosby prepared to attend adébutante

A debutante, also spelled débutante ( ; from , ), or deb is a young woman of aristocratic or upper-class family background who has reached maturity and is presented to society at a formal "debut" ( , ; ) or possibly debutante ball. Original ...

ball one evening. As was customary, she put on a corset

A corset /ˈkɔːrsɪt/ is a support garment worn to constrict the torso into the desired shape and Posture correction, posture. They are traditionally constructed out of fabric with boning made of Baleen, whalebone or steel, a stiff panel in th ...

stiffened with whalebone

Baleen is a filter-feeding system inside the mouths of baleen whales. To use baleen, the whale first opens its mouth underwater to take in water. The whale then pushes the water out, and animals such as krill are filtered by the baleen and ...

and a restrictive, tight cover that flattened and jammed her breasts together. The point of a corset was to cinch the waist in as tightly as possible, holding a woman's torso erect. It would have been difficult to feel comfortable dressed in such a confining garment. Mary had worn that same dress at her debut to society a few weeks earlier. It was a sheer evening gown with a plunging neckline to display the cleavage. However, in this case the corset cover, a "boxlike armour of whalebone and pink cordage," poked out from under the gown, so she called her personal maid. She told her, "Bring me two of my pocket handkerchiefs and some pink ribbon ... And bring the needle and thread and some pins." She fashioned the handkerchiefs and ribbon into a simple bra.

Mary's devised undergarment complemented the new fashions of the time. She was mobbed after the dance by other girls who wanted to know how she moved so freely, and when she showed the garment to friends the next day, they all wanted one. One day, she received a request for one of her contraptions from a stranger, who offered a dollar for her efforts. She knew then that this could become a viable business.

Patent granted

Crosby filed for a patent for her invention on February 12, 1914, and in November that year the

Crosby filed for a patent for her invention on February 12, 1914, and in November that year the United States Patent and Trademark Office

The United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) is an List of federal agencies in the United States, agency in the United States Department of Commerce, U.S. Department of Commerce that serves as the national patent office and trademark ...

granted her a patent for the 'Backless Brassiere

A bra, short for brassiere or brassière (, ; ), is a type of form-fitting underwear that is primarily used to support and cover a woman's breasts. A typical bra consists of a chest band that wraps around the torso, supporting two breast cu ...

'. Crosby likened her design to earlier covers over the bosom when a woman wore a low corset. Her design had shoulder straps to attach to the garment's upper and lower corners, and wrap-around laces for the lower corners which tied at the woman's front, enabling her to wear gowns cut low in the back. Crosby wrote that her invention was "well-adapted to women of different size" and was "so efficient that it may be worn by persons engaged in violent exercise like tennis." Her design was lightweight, soft, and comfortable to wear. It naturally separated the breasts, unlike the corset, which was heavy, stiff, and uncomfortable, and had the effect of creating a single "monobosom" effect.

While Crosby's design was the first granted a patent within its category, The U.S. Patent Office and foreign patent offices had issued patents for various bra-like undergarment

Underwear, underclothing, or undergarments are items of clothing worn beneath outer clothes, usually in direct contact with the skin, although they may comprise more than a single layer. They serve to keep outer clothing from being soiled ...

s as early as the 1860s. Other brassiere designs

There are many brassiere designs suitable for a wide variety of business and social settings and suitable to wear with a variety of outer clothing. The bra's shape, coverage, functionality, fit, fashion, fabric, and color can vary widely. Some ...

had previously been invented and popularized for use within the United States since about 1910. By 1912, American mass-market brassiere manufacturers included Bien Jolie Brassieres and DeBevoise Brassieres. The latter first advertised its bust supporter in ''Vogue

Vogue may refer to:

Business

* ''Vogue'' (magazine), a US fashion magazine

** British ''Vogue'', a British fashion magazine

** '' Vogue Adria'', a fashion magazine for former Yugoslav countries

** ''Vogue Arabia'', an Arab fashion magazine

** ' ...

'' in 1904.

Leading European couturier Lucile actively endorsed bras, and both Lucile and Paul Poiret

Paul Poiret (20 April 1879 – 30 April 1944) was a French fashion designer, a master couturier during the first two decades of the 20th century. He was the founder of his namesake haute couture house.

Early life and career

Poiret was bor ...

refined and promoted the brassiere, influencing fashionable women to wear their designs, Paris couturier Herminie Cadolle

Herminie Cadolle (1845–1926) was a French inventor of the modern bra and founder of the Cadolle Lingerie House.

Early life

Herminie Cadolle was born, raised, and lived much of her early life in France. She was a close friend of the insurrec ...

introduced a breast supporter in 1889. His design was a sensation at the Great Exposition of 1900 and became a fast-selling design among wealthy Europeans in the next decade.

Business career

After she married Richard Peabody, Crosby filed a legal certificate with theCommonwealth of Massachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode ...

on May 19, 1920, declaring that she was a married woman conducting a business using funds that were from her husband's bank account. In 1922 she founded the Fashion Form Brassière Company, locating her manufacturing shop on Washington Street in Boston, where she opened a two-woman sweatshop

A sweatshop or sweat factory is a cramped workplace with very poor and/or illegal working conditions, including little to no breaks, inadequate work space, insufficient lighting and ventilation, or uncomfortably or dangerously high or low temperat ...

to manufacture her wireless brassières. The location also became a convenient place for romantic trysts with Harry Crosby, who would become her second husband.

In her later autobiography, ''The Passionate Years,'' she maintained that she had "a few hundred (units) of her design produced." She managed to secure a few orders from department stores, but her business never took off. Harry, who had a distaste for conventional business and a generous trust fund, discouraged her from pursuing the business and persuaded her to close it. She later sold the brassiere patent to The Warner Brothers Corset Company in Bridgeport, Connecticut, for US$1,500 (roughly equivalent to $ in current dollars). Warner manufactured the "Crosby" bra for a while, but it was not a popular style and was eventually discontinued. However, Warner would go on to earn more than US$15 million from the bra patent over the next thirty years.

In her later years, Crosby wrote, "I can't say the brassiere will ever take as great a place in history as the steamboat, but I did invent it."

Marriages and family life

In 1915, Polly Jacob and Richard ("Dick") Peabody were married by his grandfather,Endicott Peabody

Endicott Howard Peabody (February 15, 1920 – December 2, 1997) was an American politician from Massachusetts. A Democrat, he served a single two-year term as the 62nd Governor of Massachusetts, from 1963 to 1965. His tenure is probably ...

, the founder of the Groton School

Groton School is a Private school, private, college-preparatory school, college-preparatory, day school, day and boarding school located in Groton, Massachusetts, United States. It is affiliated with the Episcopal Church (United States), Episcop ...

, and whose family had been one of the wealthiest in America during the 19th century. By the early 20th century, a case could be made that the Peabodies had supplanted the Cabots and the Lodges as the most distinguished name in the region.

Crosby found Peabody's temperament to be far from her own. When they had a son, William Jacob, on February 4, 1916, she noted that "Dick was not the most indulgent of parents and like his father before him, he forbade the gurgles and cries of infancy; when they occurred he walked out, and often walked back unsteadily."

Crosby concluded that Peabody was a well-educated but undirected man, and a reluctant father. Less than a year later, he enlisted at the Mexican border and joined the Boston militia engaged in stopping Pancho Villa

Francisco "Pancho" Villa ( , , ; born José Doroteo Arango Arámbula; 5 June 1878 – 20 July 1923) was a Mexican revolutionary and prominent figure in the Mexican Revolution. He was a key figure in the revolutionary movement that forced ...

's cross-border raids. Less than a year after he returned home from that adventure, he enlisted to fight in World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. Their second child, a daughter, Polleen Wheatland ("Polly"), was born on August 12, 1917, but Peabody was already in Officers Training Camp at Plattsburgh, New York

Plattsburgh is a city in and the county seat of Clinton County, New York, United States, situated on the north-western shore of Lake Champlain. The population was 19,841 at the United States Census, 2020, 2020 census. The population of the sur ...

, where he was commissioned a Second Lieutenant in the Artillery. He became a Captain in the United States Army's 15th Field Artillery, 2nd Division, American Expeditionary Force

The American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) was a formation of the United States Armed Forces on the Western Front (World War I), Western Front during World War I, composed mostly of units from the United States Army, U.S. Army. The AEF was establis ...

. Baby Polly was largely cared for by Peabody's parents, but Crosby recalled that "My father-in-law was a stickler for polish, both of manners and minerals." Crosby's mother-in-law wore "nun-like dresses and in bed or out wore starched cuffs as sever as piping." Peabody, meanwhile, was enjoying life at the front as a bachelor.

Peabody returned home in early 1921 and was assigned to Columbia, South Carolina

Columbia is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the U.S. state of South Carolina. With a population of 136,632 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is List of municipalities in South Carolina, the second-mo ...

. Crosby and the children soon joined him, but when the war ended, Peabody found himself left with nothing but a family allowance. He suffered from his war experiences and returned to heavy drinking. Crosby found he had only three real interests, all acquired at Harvard

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher lear ...

: to play, to drink, and to turn out, at any hour, to chase after fire engines and watch buildings burn. Crosby's life was difficult during the war years, and when her husband returned home, significantly changed, her life soon changed abruptly, too.

Relationship with Harry Crosby

The catalyst for Polly Jacob Peabody's transformation was her introduction and eventual marriage to Harry Crosby, a wealthy scion of a socially prominent Boston family, and another veteran and victim of the recent war. Harry attended private schools and until age 19 appeared to be well on the path to a comfortable life as a member of the upper middle class. His experiences in World War I changed everything. In the pattern of other sons of the elite from New England, he was a volunteer in the American Field Service Ambulance Corps, along with Archibald MacLeish and Ernest Hemingway. On November 22, 1917, the ambulance he was driving was destroyed by artillery fire, but he emerged miraculously unhurt. His best friend, "Spud" Spaulding, was seriously wounded in the explosion, and Harry saved his life. The experience profoundly shaped Harry's future. He was at the SecondBattle of Verdun

The Battle of Verdun ( ; ) was fought from 21 February to 18 December 1916 on the Western Front (World War I), Western Front in French Third Republic, France. The battle was the longest of the First World War and took place on the hills north ...

. After the battle, his section (the 29th Infantry Division, attached to the 120th French Division) was cited for bravery, and in 1919 Crosby was one of the youngest Americans awarded the Croix de Guerre

The (, ''Cross of War'') is a military decoration of France. It was first created in 1915 and consists of a square-cross medal on two crossed swords, hanging from a ribbon with various degree pins. The decoration was first awarded during World ...

. Crosby wrote in his journal, "Most people die of a sort of creeping common sense and discover when it's too late that the only things one never regrets are one's mistakes." He vowed that he would live life on his own terms.

After returning from World War I and while completing his degree at Harvard, Harry met Polly on July 4, 1920, at an Independence Day

An independence day is an annual event memorialization, commemorating the anniversary of a nation's independence or Sovereign state, statehood, usually after ceasing to be a group or part of another nation or state, or after the end of a milit ...

picnic. Polly's husband Richard was in a sanitarium drying out from another drunken spell. Sensing Polly's isolation, Harry's mother Henrietta Crosby had invited Polly to chaperone Harry and some of his friends to a party, including dinner and a trip to the amusement park at Nantasket Beach

Nantasket Beach is a beach in the town of Hull, Massachusetts. It is part of the Nantasket Beach Reservation, administered by the state Department of Conservation and Recreation. The shore has fine, light gray sand and is one of the most highl ...

. Polly was 28, married, with two small children. Harry was 22, of slight build, with an unusual blonde hair style, a pale complexion, a weak constitution, a consuming gaze and enormous charisma. During dinner, Harry never spoke to the girl on his left, breaking decorum

Decorum (from the Latin: "right, proper") was a principle of classical rhetoric, poetry, and theatrical theory concerning the fitness or otherwise of a style to a theatrical subject. The concept of ''decorum'' is also applied to prescribed lim ...

. By some accounts, Harry fell in love with the buxom Mrs. Peabody in about two hours. He confessed his love for her in the Tunnel of Love at the amusement park. Crosby pressed her to see him alone, an unthinkable proposition for a member of Boston's upper class. She later wrote, "Harry was utterly ruthless ... to know Harry was a devastating experience." On July 20, they spent the night together and had sex, and two days later Polly accompanied Harry to New York. He had planned a trip to France to tour battle sites. They spent the night together in New York at the Belmont Hotel. Polly said of the night, "For the first time in my life, I knew myself to be a person."

Polly was seen by her social circle as someone who had betrayed the trust placed in her as a chaperone, and as an older woman who had taken advantage of a younger man. To the Crosbys, she was dishonorable and corrupt. Polly and Harry's scandalous courtship was the gossip of blue-blood Boston.

In the fall, Polly's husband Dick Peabody moved back home. His parents supplied a small living allowance and Dick, Polly, and the two children moved into a three-story tenement

A tenement is a type of building shared by multiple dwellings, typically with flats or apartments on each floor and with shared entrance stairway access. They are common on the British Isles, particularly in Scotland. In the medieval Old Town, E ...

building. Meanwhile, Crosby lived with his father while Dick continued his studies at Harvard. While Dick worked at the bank, Harry Crosby sent crates of flowers from his mother's garden to Polly's apartment and brought over toys for the children. They drove to the beach together. Dick volunteered to join the fire department, and persuaded the fire chief to wire a fire alarm bell to his home, so he could turn out at any hour. The fire chief soon let Dick go, and Dick retreated into drink again.

Crosby pursued Polly, and in May 1921, when she would not respond to his ardor, Crosby threatened suicide if Polly did not marry him. Polly's husband was in and out of sanitariums several times, fighting alcoholism. Crosby pestered Polly to tell her husband of their affair and to divorce him. In May, she revealed her adultery to Dick and suggested a separation, and he offered no resistance. Polly's mother insisted that she stop seeing Crosby for six months to avoid complete rejection by her society peers, a condition she agreed to, and she left Boston for New York. Divorce was "unheard of ... even among Boston Episcopalians." Peabody's parents were outraged at her affair with Crosby, and that she would ask for a divorce. Dick's father Jacob Peabody even visited Harry's father, Stephen Crosby, on January 4, 1922, to discuss the situation, but Harry's father would not meet with him, for despite his disapproval of Harry's irregular behavior, he loved his son. Stephen Crosby at first attempted to dissuade Harry from marrying Polly, and even bought him the Stutz

The Stutz Motor Car Company was an American automobile Automotive industry, manufacturer based in Indianapolis, Indiana that produced high-end Sports cars, sports and Luxury vehicle, luxury cars. The company was founded in 1911 as the Idea ...

motor car he had been asking for, but Harry would not be persuaded to change his mind. For her part, Polly's former friends pilloried her as an adulteress

Adultery is extramarital sex that is considered objectionable on social, religious, moral, or legal grounds. Although the sexual activities that constitute adultery vary, as well as the social, religious, and legal consequences, the concept e ...

, leaving Polly stunned by the quick turn-about in their attitudes toward her. Polly later described Harry's character as: "He seemed to be more expression and mood, than man," she wrote, "yet he was the most vivid personality I've ever known, electric with rebellion.

Divorce from Richard Peabody

In June 1921, she formally separated from Dick, and in December he offered to divorce her. In February 1922, Polly and Richard Peabody were legally divorced. Dick subsequently recovered from his alcoholism and published ''The Common Sense of Drinking'' (1933). He was the first to assert there was no cure for alcoholism. His book became a best seller and was a major influence onAlcoholics Anonymous

Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) is a global, peer-led Mutual aid, mutual-aid fellowship focused on an abstinence-based recovery model from alcoholism through its spiritually inclined twelve-step program. AA's Twelve Traditions, besides emphasizing anon ...

founder Bill Wilson. Crosby had been working for eight months at Shawmut National Bank. He went on a six-day drinking spree and resigned. In May 1922, he moved to Paris to work in a job arranged for him by his family at Morgan, Harjes et Cie, the Morgan family's bank in Paris. This was fitting, for Crosby, after all, was the nephew of Jessie Morgan, the wife of American capitalist

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

J. P. Morgan, Jr., but it was also awkward because he was both Richard Peabody's and Harry Crosby's godfather.

Polly had previously traveled to England to visit her cousins, so Crosby visited her there. From May through July, 1922 they lived together in Paris. In July, Polly returned to the U.S. In September, Harry proposed to Polly via transatlantic cable, and the next day he bribed his way aboard the RMS ''Aquitania'' bound for New York.

Move to Paris

Paris, France

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

. Harry continued his work in Paris at Morgan, Harjes & Co.

Polly's bubble in Paris burst when she learned shortly after their arrival that Harry had been flirting with a girl from Boston. It was the first of many flirtations and affairs that Polly would learn to live with. In early 1923, Polly introduced Harry to her friend Constance Crowninshield Coolidge. She was the niece of Frank Crowninshield

Francis Welch Crowninshield (June 24, 1872 – December 28, 1947) was an American journalist and art and theater critic best known for developing and editing the magazine ''Vanity Fair (American magazine 1913-1936), Vanity Fair'' for 21 years, m ...

, editor of '' Vanity Fair'', and had been married to American diplomat Ray Atherton

Ray Atherton (March 28, 1883 – March 14, 1960) was a career United States diplomat, who served as Ambassador to Greece, Bulgaria, and Denmark. He also served the role of Head of Mission as List of ambassadors of the United States to Canada, En ...

. Constance did not care what others thought about her. She loved anything risky and was addicted to gambling. She and Harry soon began a sexual relationship.

In the fall of 1923, Polly could not put up with their affair any longer and left for London. Harry told Constance that he could not meet Polly's demand that he "love her more than anyone in the world. This is absolutely impossible." But Harry also would not leave Polly, nor did Constance ask him to. But when Constance received a letter from Polly, who confessed that Constance's affair with her husband had made her "very miserable," Constance wrote Harry and told him she would not see him any more. Harry was devastated by her decision. "Your letter was bar none the worst blow I have ever received. ... I wouldn't leave her under any circumstances nor as you say would you ever marry me." But the three remained friends, and on October 1, 1924, Constance married the Count Pierre de Jumilhac, although the marriage only lasted five years. Polly appeared at least outwardly to tolerate Harry's dallying unconventional behavior, and she soon had her own courtiers. In her journals, she privately worried about whether Harry would remain loyal to her.

Their glamorous and luxurious lifestyle soon included an open marriage

Open marriage is a form of non-monogamy in which the partners of a dyadic marriage agree that each may engage in extramarital sexual or romantic relationships, without this being regarded by them as infidelity, and consider or establish an ope ...

, numerous affairs, and plenty of drugs and drinking. At the end of 1924, Harry persuaded Polly to formally change her first name. They briefly considered Clytoris before deciding on Caresse. Harry suggesting that her new name "begin with a C to go with Crosby and it must form a cross with mine." The two names intersected at right angles at the common "R," "the Crosby cross." They later named their second whippet

The Whippet is a British breed of dog of sighthound type. It closely resembles the Greyhound and the smaller Italian Greyhound, and is intermediate between them in size. In the nineteenth century it was sometimes called "the poor man's raceh ...

Clytoris, explaining to Caresse's young daughter Polleen she was named after a Greek goddess.

In July 1925, Harry had sexual relations with a 14-year-old girl he nicknamed "Nubile," with a "baby face and large breasts," whom he saw at Étretat, a town in Normandy. In Morocco, during one of their trips to North Africa, Harry and Caresse together took a 13-year-old dancing girl named Zora to bed with them. Harry also had sex with a boy of unspecified age, his only recorded homosexual dalliance.

In 1927, in the midst of his affair with Constance, Harry and Caresse met the Russian painter Polia Chentoff. Harry asked her to paint Caresse's portrait, and he soon fell in love with Polia. In November, Harry wrote to his mother that Polia was "very beautiful and terribly serious about art... she ran away from home when she was thirteen to paint." He was also said to be in love with his cousin Nina de Polignac.

In June 1928, Harry met Josephine Rotch at the Lido

Lido may refer to:

Geography

* Lido (Belgrade), a river beach on the Danube in Belgrade, Serbia

* Venice Lido, an 11-kilometre-long barrier island in the Venetian Lagoon, Venice, Italy

* Ruislip Lido, a reservoir and artificial beach in Ruisl ...

in Venice

Venice ( ; ; , formerly ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 islands that are separated by expanses of open water and by canals; portions of the city are li ...

, while she was shopping for her wedding trousseau, and they began an affair. In her autobiography, Caresse minimized Harry's dalliance with Josephine, eliminating a number of references to her. Harry told Caresse that Constance and Josephine wanted to marry him.

Expatriate life

From their arrival in 1922, the Crosbys led the life of richexpatriates

An expatriate (often shortened to expat) is a person who resides outside their native country.

The term often refers to a professional, skilled worker, or student from an affluent country. However, it may also refer to retirees, artists and ...

. They were attracted to the bohemian lifestyle

Bohemianism is a social and cultural movement that has, at its core, a way of life away from society's conventional norms and expectations. The term originates from the French ''bohème'' and spread to the English-speaking world. It was used to ...

s of the artists gathering in Montparnasse

Montparnasse () is an area in the south of Paris, France, on the left bank of the river Seine, centred at the crossroads of the Boulevard du Montparnasse and the Rue de Rennes, between the Rue de Rennes and boulevard Raspail. It is split betwee ...

. They settled into an apartment at 12, Quai d'Orléans on Île St-Louis

Ile or ILE may refer to:

Ile

* Ile, a Puerto Rican singer

* Ile District (disambiguation), multiple places

* Ilé-Ifẹ̀, an ancient Yoruba city in south-western Nigeria

* Interlingue (ISO 639:ile), a planned language

* Isoleucine, an amino ac ...

, and Caresse donned her red bathing suit and rowed Harry down the river to the Place de la Concorde

The Place de la Concorde (; ) is a public square in Paris, France. Measuring in area, it is the largest square in the French capital. It is located in the city's eighth arrondissement, at the eastern end of the Champs-Élysées.

It was the s ...

, where he walked the last few blocks to the bank. Harry wore his dark business suit, formal hat, and carried his umbrella and briefcase. Caresse rowed home alone, and in her swim suit her generously endowed chest drew whistles, jeers, and waves from workmen. She later wrote that she thought the exercise was good for her breasts, and she enjoyed the attention.

Harry enjoyed betting on the horse races. They first smoked opium together in Africa, and when their friend Constance Crowninshield Coolidge knocked on their door late one evening, they jumped at her invitation to join her at Drosso's apartment. Invitations to Drosso's were restricted to a few regulars and occasional friends, as it was an opium den. At Drosso's she found small rooms filled with low couches and decorations evoking a middle-Eastern setting. Caresse made a sensation when she arrived, because she had been ready for bed when Constance knocked, so she quickly put on a dress, but wore nothing underneath. After that introduction, Harry dropped in at Drosso's frequently, and it sometimes kept him away from home for days at a time.

After about a year, Harry soon tired of the predictable banker's life and quit, fully joining the Lost Generation

The Lost Generation was the Demography, demographic Cohort (statistics), cohort that reached early adulthood during World War I, and preceded the Greatest Generation. The social generation is generally defined as people born from 1883 to 1900, ...

of expatriate Americans disillusioned by the restrictive atmosphere of 1920s America. They were among about 15,000–40,000 Americans living in Paris. Harry wanted as little to do with Caresse's children as possible, so after the first year they shipped her son Billy off to Cheam School

Cheam School is a mixed preparatory school located in Headley, in the civil parish of Ashford Hill with Headley in Hampshire. Originally a boys school, Cheam was founded in 1645 by George Aldrich.

History

The school started in Cheam, Surre ...

in Hampshire, England.

The couple cared little for the future, spent their money recklessly, and never tried to live on a budget. This was in part because they had made a suicide pact

A suicide pact is an agreed plan between two or more individuals to die by suicide. The plan may be to die together, or separately and closely timed.

In England and Wales, a suicide pact is a partial defense, under section 4 of the Homicide Act ...

, which they planned to carry out on October 31, 1942. On that date the earth would be closer to the sun than it had been in several decades, and they promised to jump out of an airplane together. This was to be followed by cremation, after which heirs would disperse their ashes from another airplane.

Spending freely, Harry bought a silk-buttonhole gardenia tuxedo from an exclusive tailor on rue de la Paix. Caresse bought hats from Jean Patou

Jean Patou (; 27 September 1887 – 8 March 1936) was a French fashion designer, and founder of the Jean Patou brand.

Early life

Patou was born in Paris, France in 1880. Patou's family's business was tanning and furs. Patou worked with his u ...

and dresses from the fashion house Tolstoy's. On special occasions she wore an evening suit made of gold fabric, featuring a short skirt tailored by Vionnet, one of the most important Parisian fashion icons. Although perfectly chic by Parisian standards, it was nevertheless unacceptable to her cousins and aunts who lived in the aristocratic neighborhood of Faubourg

"Faubourg" () is an ancient French term historically equivalent to "fore-town" (now often termed suburb or ). The earliest form is , derived from Latin , 'out of', and Vulgar Latin (originally Germanic) , 'town' or 'fortress'. Traditionally, t ...

in Paris.

Caresse and Harry purchased their first race horse in June 1924, and then two more in April 1925. They rented a fashionable apartment at 19, Rue de Lille, and obtained a 20-year lease on a mill outside of Paris on the grounds of the Château d' Ermenonville

Ermenonville () is a commune in the Oise department, northern France. Located near Paris, Ermenonville is notable for its park named for Jean-Jacques Rousseau by René Louis de Girardin. Rousseau's tomb was designed by the painter Hubert Robe ...

, which belonged to their friend Armand de la Rochefoucauld, for 2,200 dollar gold pieces (about $ today). They named it "Le Moulin du Soleil" ("The Mill of the Sun"), and she used a wall as a "guest book" for guests to paint pictures and sign their names.

In the first year there, they made friends with a group of students who attended the Académie des Beaux-Arts

The (; ) is a French learned society based in Paris. It is one of the five academies of the . The current president of the academy (2021) is Alain-Charles Perrot, a French architect.

Background

The academy was created in 1816 in Paris as a me ...

, located at the end of their street. The students invited Harry and Caresse to their annual Quartre Arts Ball, an invitation the couple embraced with enthusiasm. Harry fashioned a necklace out of four dead pigeons, sported a red loincloth, and brought along a bag of snakes. Caresse wore a sheer garment that only came up to her waist, a huge turquoise wig, and nothing else. They both dyed their skin with red ochre. The students cheered Caresse's toplessness, and 10 of them carried her around on their shoulders.

In January 1925 they traveled to North Africa

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

, where they again smoked opium

Opium (also known as poppy tears, or Lachryma papaveris) is the dried latex obtained from the seed Capsule (fruit), capsules of the opium poppy ''Papaver somniferum''. Approximately 12 percent of opium is made up of the analgesic alkaloid mor ...

, a habit to which they would return again and again. In 1928, they traveled to Lebanon

Lebanon, officially the Republic of Lebanon, is a country in the Levant region of West Asia. Situated at the crossroads of the Mediterranean Basin and the Arabian Peninsula, it is bordered by Syria to the north and east, Israel to the south ...

to visit the Temple of Baalbek.

In 1928, Harry inherited his cousin Walter Berry's considerable collection of over 8,000 mostly rare books, a collection he prized but which he also scaled back by giving away hundreds of volumes. He was known to slip rare first editions into the bookstalls that lined the Seine. Caresse took on lovers of her own, including Ortiz Manolo, Lord Lymington, Jacques Porel, Cord Meier, and in May, 1928, the Count Armand de La Rochefoucauld, son of the duke de Doudeauville, president of the Jockey Club

The Jockey Club is the largest commercial horse racing organisation in the United Kingdom. It owns 15 of Britain's famous racecourses, including Aintree Racecourse, Aintree, Cheltenham Racecourse, Cheltenham, Epsom Downs Racecourse, Epsom ...

. But behind closed doors, Harry applied a double standard, quarreling violently with Caresse about her affairs. Occasionally they were swingers together, as when they met two other couples and drove to the country near Bois de Boulogne, drew the cars into a circle with their headlights on, and changed partners.

Affair with Cartier-Bresson

In 1929, Harry metHenri Cartier-Bresson

Henri Cartier-Bresson (; 22 August 1908 – 3 August 2004) was a French artist and Humanist photography, humanist photographer considered a master of candid photography, and an early user of 135 film, 35mm film. He pioneered the genre of street ...

at Le Bourget

Le Bourget () is a commune in the northeastern suburbs of Paris, France. It is located from the center of Paris.

The commune features Le Bourget Airport, which in turn hosts the Musée de l'Air et de l'Espace (Air and Space Museum). A very ...

, where Cartier-Bresson's air squadron commandant had placed him under house arrest for hunting without a license. Harry persuaded the officer to release Cartier-Bresson into his custody for a few days. The men found they shared an interest in photography, and they spent their time together taking and printing pictures at Harry and Caresse's home, Le Moulin du Soleil. Harry later said Cartier-Bresson "looked like a fledgling, shy and frail, and mild as whey." A friend of Crosby's from Texas encouraged Cartier-Bresson to take photography more seriously. Embracing the open sexuality offered by Caresse and Harry, Cartier-Bresson fell into an intense sexual relationship with her. In 1931, two years after Harry's suicide, the end of his affair with Caresse Crosby left Cartier-Bresson broken-hearted, and he escaped to Ivory Coast

Ivory Coast, also known as Côte d'Ivoire and officially the Republic of Côte d'Ivoire, is a country on the southern coast of West Africa. Its capital city of Yamoussoukro is located in the centre of the country, while its largest List of ci ...

of French colonial Africa.

Publication of poetry

Caresse and Harry published her first book, ''Crosses of Gold'', in late 1924. It was a volume of conventional, "unadventurous" poetry centering on themes such as love, beauty, and her husband.

In 1926 they published her second book, ''Graven Images,'' with

Caresse and Harry published her first book, ''Crosses of Gold'', in late 1924. It was a volume of conventional, "unadventurous" poetry centering on themes such as love, beauty, and her husband.

In 1926 they published her second book, ''Graven Images,'' with Houghton Mifflin

The asterisk ( ), from Late Latin , from Ancient Greek , , "little star", is a typographical symbol. It is so called because it resembles a conventional image of a heraldic star.

Computer scientists and mathematicians often vocalize it as ...

in Boston. This was the only time they used another publisher. Harry later wrote that his cousin, Walter Berry, suggested that Houghton Mifflin would publish Caresse's poetry because "they have just lost Amy Lowell

Amy Lawrence Lowell (February 9, 1874 – May 12, 1925) was an American poet of the imagist school. She posthumously won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1926.

Life

Amy Lowell was born on February 9, 1874, in Boston, Massachusetts, the daughte ...

." Her work remained relatively conventional, "still rhyming love with dove," by her own admission. A ''Boston Transcript'' reviewer said her "poetry sings," and a ''Literary Review'' contributor admired her "charming" child poems and French flavor. But a critic in the ''New York Herald Tribune'' wrote that " r all its enthusiasm there is no impact to thought or phrase, the emotion is meager, the imagination bridled."

In April 1927 they founded an English-language publishing company that they first named Éditions Narcisse, after their black whippet, Narcisse Noir. They used the press as an avenue to publish their own poetry in small editions of finely-made, hard-bound volumes. Their first effort was Caresse's ''Painted Shores,'' in which she wrote about their relationship, including their reconciliation after one of Harry's affairs. Her writing matured somewhat, and the book was more creatively organized than her prior efforts. In 1928 she wrote an epic poem which was published as ''The Stranger.'' The writing is addressed to the men in her life: her father, husband, and son. In an experimental fashion she explored the various kinds of love she had known. Later that year, ''Impossible Melodies'' explored similar themes. The Crosbys enjoyed such a positive reception of their initial work and decided to expand the press to serve other authors.

Publishing in Paris during the 1920s and 1930s put the company in the milieu of so many American writers who were living abroad. In 1928, Éditions Narcisse published a limited edition of 300 numbered copies of "The Fall of the House of Usher

"The Fall of the House of Usher" is a short story by American writer Edgar Allan Poe, first published in 1839 in ''Burton's Gentleman's Magazine'', then included in the collection ''Tales of the Grotesque and Arabesque'' in 1840. The short stor ...

" by Edgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe (; January 19, 1809 – October 7, 1849) was an American writer, poet, editor, and literary critic who is best known for his poetry and short stories, particularly his tales involving mystery and the macabre. He is widely re ...

with illustrations by Alastair.

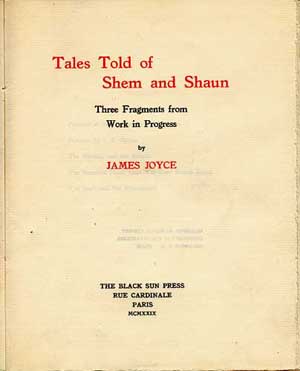

In 1928, Harry and Caresse changed the name of the publishing house to the Black Sun Press, in keeping with Harry's fascination with death and the symbolism of the sun. Harry developed a private mythology around the sun as a symbol for both life and death, creation, and destruction. The press rapidly gained notice for publishing beautifully bound, typographically flawless editions of unusual books. They took exquisite care with the books they published, choosing the finest papers and inks.

They published early works of a number of avant-garde

In the arts and literature, the term ''avant-garde'' ( meaning or ) identifies an experimental genre or work of art, and the artist who created it, which usually is aesthetically innovative, whilst initially being ideologically unacceptable ...

writers before those writers were well-known, including James Joyce's ''Tales Told of Shem and Shaun,'' which was later integrated into ''Finnegans Wake

''Finnegans Wake'' is a novel by Irish literature, Irish writer James Joyce. It was published in instalments starting in 1924, under the title "fragments from ''Work in Progress''". The final title was only revealed when the book was publishe ...

.'' They published Kay Boyle's first book-length work, ''Short Stories,'' in 1929, and works by Hart Crane, Ernest Hemingway, Eugene Jolas

John George Eugène Jolas (October 26, 1894 – May 26, 1952) was a writer, translator and literary critic.

Early life

John George Eugène Jolas was born October 26, 1894, in Union Hill, New Jersey (what is today Union City, New Jersey). His p ...

, D. H. Lawrence

David Herbert Lawrence (11 September 1885 – 2 March 1930) was an English novelist, short story writer, poet, playwright, literary critic, travel writer, essayist, and painter. His modernist works reflect on modernity, social alienation ...

, Archibald MacLeish, Ezra Pound

Ezra Weston Loomis Pound (30 October 1885 – 1 November 1972) was an List of poets from the United States, American poet and critic, a major figure in the early modernist poetry movement, and a Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Ita ...

, and Laurence Sterne

Laurence Sterne (24 November 1713 – 18 March 1768) was an Anglo-Irish novelist and Anglican cleric. He is best known for his comic novels ''The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman'' (1759–1767) and ''A Sentimental Journey Thro ...

. The Black Sun Press evolved into one of the most important small presses in Paris in the 1920s. In 1929, Caresse and Harry both signed poet Eugene Jolas

John George Eugène Jolas (October 26, 1894 – May 26, 1952) was a writer, translator and literary critic.

Early life

John George Eugène Jolas was born October 26, 1894, in Union Hill, New Jersey (what is today Union City, New Jersey). His p ...

' ''The Revolution of the Word Proclamation'', which appeared in issue 16/17 of the literary journal '' transition.'' After Harry died, Caresse continued publishing until 1936, when she left Europe for the United States.

Harry's suicide

On July 9, 1928, Harry met 20-year-old Josephine Noyes Rotch, whom he would call the "Youngest Princess of the Sun" and the "Fire Princess." She was descended from a family that first settled inProvincetown

Provincetown () is a New England town located at the extreme tip of Cape Cod in Barnstable County, Massachusetts, in the United States. A small coastal resort town with a year-round population of 3,664 as of the 2020 United States census, Pr ...

, Cape Cod

Cape Cod is a peninsula extending into the Atlantic Ocean from the southeastern corner of Massachusetts, in the northeastern United States. Its historic, maritime character and ample beaches attract heavy tourism during the summer months. The ...

in 1690. Josephine inspired Harry's next collection of poems called ''Transit of Venus.'' Though she was several years his junior, Harry fell in love with Josephine. In a letter to his mother, dated July 24, 1928, Harry wrote:

Josephine and Harry had an ongoing affair until she married, when their relationship temporarily ended. However, Josephine rekindled the affair, and in late November 1929, Harry and Josephine met and traveled to Detroit, where they checked into an expensive Book-Cadillac Hotel

The Westin Book Cadillac Detroit is an historic skyscraper hotel in downtown Detroit, Michigan, within the Washington Boulevard Historic District. Designed in the Neo-Renaissance style, and opened as the Book-Cadillac Hotel in 1924, the , 31-s ...

as Mr. and Mrs. Harry Crane. For four days they took meals in their room, smoked opium, and had sex.

On November 29, 1929, the lovers returned to New York, where once again they attempted to end the affair, and Josephine agreed that she would return to Boston and her husband. But two days later, she had delivered a 36-line poem to Harry, who was staying with Caresse at the Savoy-Plaza Hotel. The last line of the poem read "Death is our marriage." On December 9, Harry Crosby wrote in his journal for the last time: "One is not in love unless one desires to die with one's beloved. There is only one happiness it is to love and to be loved."

Harry was found at 10 that night in bed at Stanley Mortimer's studio in the Hotel des Artistes. He had a .25 caliber bullet hole in his right temple. He lay next to Josephine, who had a matching hole in her left temple. They were in an affectionate embrace. Both were dressed, but had bare feet. Harry sported red-painted toenails and tattoos on the bottom of his feet. The coroner said that Josephine died at least two hours before Harry did. There was no suicide note, and newspapers ran sensational articles for days, calling it a murder-suicide or double suicide pact, and unable to decide which was more fitting.

Later life

Harry left Caresse US$100,000 (about $ today) in his will, along with generous bequests to Josephine, Constance, and others. His parents Stephen and Henrietta had the will declared invalid, but reassured Caresse that she would receive US$2000 (approximately $ today) a year until she received money from Walter Berry's estate. Upon Caresse Crosby's return to Europe, she asked her friend Bill Sykes to bring Polleen from Chamonix. She also welcomed Billy home when another friend brought him from boarding school, and the family and friends spent some time at the Mill. Polleen stayed with her mother for a few months, refusing to return to school. Billy returned to Choam, and in 1931 returned to the U.S. to attend the Lenox School. Crosby decided to reclaim her birth name, Mary, and thus was known after her husband's death as "Mary Caresse Crosby." She pursued ambitions as an actress that she had had since her 20s, and appeared as a dancer in two shortexperimental film

Experimental film or avant-garde cinema is a mode of filmmaking that does not apply standard cinematic conventions, instead adopting Non-narrative film, non-narrative forms or alternatives to traditional narratives or methods of working. Many e ...

s directed by artist Emlen Etting, ''Poem 8'' (1932) and ''Oramunde'' (1933).

Crosby broadened the scope of the Black Sun Press after Harry's death. Although the press published few works after 1952, it printed James Joyce's ''Collected Poems'' in 1963. Despite the slowdown, it did not officially close until Crosby's death in 1970.

Continuation of Black Sun Press

After Harry's suicide, Caresse dedicated herself to the Black Sun Press. She also established, with Jacques Porel, a side venture to publish paperback books when they were not yet popular, which she named Crosby Continental Editions. Ernest Hemingway, a long-time friend, offered her a choice of ''The Torrents of Spring

''The Torrents of Spring'' is a novella written by Ernest Hemingway, published in 1926. Subtitled "A Romantic Novel in Honor of the Passing of a Great Race", Hemingway used the work as a spoof of the world of writers. It is Hemingway's first l ...

'' (1926) or ''The Sun Also Rises

''The Sun Also Rises'' is the first novel by the American writer Ernest Hemingway, following his experimental novel-in-fragments '' In Our Time (short story collection)'' (1925). It portrays American and British expatriates who travel from Par ...

'' (1926) as a debut volume for her new venture. Caresse picked the former, which was less well-received than ''The Sun Also Rises''. She followed Hemingway's work with nine more books in 1932, including William Faulkner's ''Sanctuary,'' Kay Boyle's ''Year Before Last,'' Dorothy Parker's ''Laments for the Living,'' and Antoine de Saint-Exupéry's '' Night Flight,'' along with works by Paul Eluard, Max Ernst

Max Ernst (; 2 April 1891 – 1 April 1976) was a German-born painter, sculptor, printmaker, graphic artist, and poet. A prolific artist, Ernst was a primary pioneer of the Dada movement and surrealism in Europe. He had no formal artistic trai ...

, Alain-Fournier

Henri-Alban Fournier (; 3 October 1886 – 22 September 1914),Mémoire des hommes

Secrétariat ...

, Secrétariat ...

George Grosz

George Grosz (; ; born Georg Ehrenfried Groß; July 26, 1893 – July 6, 1959) was a German artist known especially for his caricatural drawings and paintings of Berlin life in the 1920s. He was a prominent member of the Berlin Dada and New Obj ...

, C. G. Jung, and Charles-Louis Philippe

Charles-Louis Philippe (; 4 August 1874 – 21 December 1909) French novelist, was born in Cérilly, Allier, Auvergne (region), Auvergne, on 4 August 1874, and died in Paris on 21 December 1909.

Life

Son of a village clogmaker, Charles-Lou ...

. After six months of sales, the books only grossed about US$1200. Crosby was unable to persuade U.S. publishers to distribute her work, as paperbacks were not yet widely engaged, because publishers were not convinced that readers would buy them. She closed the press in 1933.

Interracial affair with Canada Lee

In 1934, she began a love affair with the black actor-boxerCanada Lee

Leonard Lionel Cornelius Canegata (March 3, 1907 – May 9, 1952), known professionally as Canada Lee, was an American professional boxer and actor who pioneered roles for African Americans. After careers as a jockey, boxer and musician, he beca ...

, despite living under the threat of miscegenation laws. They had lunch uptown in Harlem

Harlem is a neighborhood in Upper Manhattan, New York City. It is bounded roughly by the Hudson River on the west; the Harlem River and 155th Street on the north; Fifth Avenue on the east; and Central Park North on the south. The greater ...

at the then-new restaurant ''Franks,'' where they could maintain their secret relationship. By the 1940s, Lee was a Broadway star and featured in the nationwide run of the play '' Native Son.'' But the only establishment in Washington, D.C. where they could eat together was an African restaurant named the ''Bugazi.'' Lee, unlike so many of her lovers, did not ask for money, even when his nightclub ''The Chicken Coop'' had a difficult time. When, during a dinner in the early 1940s, Crosby's brother Walter expressed his dismay at their relationship, Crosby was so offended that she made little contact with Walter over the next 10 years. Crosby and Lee's intimate relationship continued into the mid-1940s and contributed to her worldview. Crosby wrote a never-published play, ''The Cage,'' transparently based on their relationship.

Marriage to Bert Saffold Young

While taking her daughter Polly to Hollywood, where the latter aspired to become an actor, Crosby met Selbert "Bert" Saffold Young (1910-1971), an unemployed aspiring actor and former football player 18 years her junior. When he saw her staring at him in a restaurant, he immediately came over and asked her to dance. She described him as "handsome as Hermes" and "as militant as Mars." Her friend Constance described Bert as "untamed" and "entirely ruled by impulse." Without a job, he convinced Crosby he just wanted to own a farm, and they decided to look for land on the East Coast. They drove through Virginia, looking for an old plantation house smothered in roses. When their car broke down, she accidentally discovered Hampton Manor, a Hereford cattle farm with a dilapidated brick mansion on a estate inBowling Green, Virginia

Bowling Green is an incorporated town in Caroline County, Virginia, United States. The population was 1,111 at the 2010 census.

The county seat of Caroline County since 1803, Bowling Green is best known as the "cradle of American horse racing" ...

. It had been built in 1838 by John Hampton DeJarnette from plans by his friend, Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (, 1743July 4, 1826) was an American Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the third president of the United States from 1801 to 1809. He was the primary author of the United States Declaration of Indepe ...

. John Hampton was the brother of Virginia Legislator Daniel Coleman DeJarnette, Sr.

On September 30, 1936, she wrote to the New York Trust Company

The New York Trust Company was a large trust and wholesale-banking business that specialized in servicing large industrial accounts. It merged with the Chemical Corn Exchange Bank and eventually the merged entity became Chemical Bank.

History 19t ...

and instructed them to send 433 shares of stock that she used to buy the property, which was in need of renovation. Crosby and Young were married in Virginia on March 24, 1937. There were problems, however. He was always asking her for money, he crashed her car, he ran up the telephone bill, and he used all her credit at the local liquor store. Bert ended one bout of drinking with a solo trip to Florida, and he did not come back to Virginia until the next year.

A ghostwriter of erotica

In Paris during 1933, Crosby had met Henry Miller. When he returned to the U.S. in 1940, Miller confessed to Crosby his lack of success in getting his work published. Miller's autobiographical book ''Tropic of Cancer

The Tropic of Cancer, also known as the Northern Tropic, is the Earth's northernmost circle of latitude where the Sun can be seen directly overhead. This occurs on the June solstice, when the Northern Hemisphere is tilted toward the Sun ...

'' was banned in the U.S. as pornographic

Pornography (colloquially called porn or porno) is sexually suggestive material, such as a picture, video, text, or audio, intended for sexual arousal. Made for consumption by adults, pornographic depictions have evolved from cave paintings ...

, and he could get no other work published. She invited him to take a room in her spacious New York apartment on East 54th Street, where she infrequently lived. He accepted, although she did not provide him with money.

Desperate for cash, Miller fell to churning out erotica on commission for an Oklahoma oil baron at a dollar per page, but after two 100-page stories that brought him US$200, he felt he could do no more. Now he wanted to tour the United States by car and write about it. He got a US$750 advance and persuaded the oil man's agent to advance him another $200. He was preparing to leave on the trip but still had not provided the work promised. He thought then of Crosby. She was already pitching ideas and pieces of writing to Anaïs Nin's New York City smut club for fun, but not for money. In her journal, Nin wrote, " Harvey Breit, Robert Duncan, George Barker, Caresse Crosby, all of us concentrating our skills in a tour de force, supplying the old man with such an abundance of perverse felicities, that now he begged for more." Crosby was facile and clever, writing easily and quickly with little effort.

Crosby accepted Miller's proposal. She wrote at the top the title given her by Henry Miller, ''Opus Pistorum'' (later republished as Miller's work as ''Under the Roofs of Paris''), and started right in. Miller left for his car tour of America. Crosby churned out 200 pages, and the collector's agent asked for more. Crosby's smut was just what the oil man wanted, according to his New York agent. No literary aspirations, just plain sex. In her journal, Nin wrote, "'Less poetry,' said the voice over the telephone. 'Be specific.'" In Crosby the agent had found himself a more basic and pornographic version of Henry Miller.

While Crosby's husband fell into a drunken stupor every night, she spent some of her time churning out another 200 pages of pornography. In her diary, Nin observed that everyone who wrote pornography

Pornography (colloquially called porn or porno) is Sexual suggestiveness, sexually suggestive material, such as a picture, video, text, or audio, intended for sexual arousal. Made for consumption by adults, pornographic depictions have evolv ...

with her wrote out of a self that was opposite to his or her identity, but identical with his or her desire. Crosby had grown up amid the social constraints imposed by her upper-class family in New York. She maintained a doomed and troublesome romanticism about Harry Crosby, nurtured or inflamed by having participated in a decade or more of taking both intellectual and physical lovers in Paris during the 1920s.

Political and artistic activity

Although Young was often drunk and infrequently home, Crosby did not lack for company. She extended an invitation toSalvador Dalí

Salvador Domingo Felipe Jacinto Dalí i Domènech, Marquess of Dalí of Púbol (11 May 190423 January 1989), known as Salvador Dalí ( ; ; ), was a Spanish Surrealism, surrealist artist renowned for his technical skill, precise draftsmanship, ...

and his wife Gala, who became long-term guests, during which he wrote much of his autobiography. In 1934, Dalí and his wife attended a masquerade party in New York, hosted for them by Crosby. Other visitors included Max Ernst, Buckminster Fuller

Richard Buckminster Fuller (; July 12, 1895 – July 1, 1983) was an American architect, systems theorist, writer, designer, inventor, philosopher, and futurist. He styled his name as R. Buckminster Fuller in his writings, publishing more t ...

, Stuart Kaiser, Henry Miller, Anaïs Nin, Ezra Pound, and other friends from her time in Paris. She had a brief affair with Fuller during this time. By 1941, having finally divorced Young, Crosby moved to live in Washington, D.C. full-time, where she owned a home at 2008 Q Street NW from 1937 to 1950, and she opened the Caresse Crosby Modern Art Gallery, what was then the city's only modern art gallery, at 1606 Twentieth Street, near Dupont Circle

Dupont Circle is a historic roundabout park and Neighborhoods in Washington, D.C., neighborhood of Washington, D.C., located in Northwest (Washington, D.C.), Northwest D.C. The Dupont Circle neighborhood is bounded approximately by 16th St ...

. Crosby planned to open the “World Gallery of Art” at Delphi in Greece to establish a capital for her peace organization, Citizens of the World. She was already a collector of American artist Joseph Glasco’s works and she approached Glasco’s art dealer Catherine Viviano to include fourteen works by Glasco with 100 other drawings by Miro, Picasso, Calder, and others. The plan was never realized and the fate of the drawings is not known.

In December, 1943, she wrote Henry Miller to ask if he had heard about her gallery, and if he would be interested in exhibiting some of his paintings there. In 1944, she spent some time with him at his home in Big Sur

Big Sur () is a rugged and mountainous section of the Central Coast (California), Central Coast of the U.S. state of California, between Carmel Highlands and San Simeon, where the Santa Lucia Range, Santa Lucia Mountains rise abruptly from th ...

and later opened his first one-man art show at her gallery.

Publication of ''Portfolio''

With the Black Sun Press she also published '' Portfolio: An Intercontinental Quarterly,'' in which she continued her work with young and avant-garde writers and artists. She printed issues 1, 3, and 5 in the U.S. The second issue was published in Paris in December 1945, less than seven months after the end of World War II. It featured primarily French writers and artists; the fourth issue was published in Rome and focused on Italian writers and artists; and the last issue was focused on Greek artists and writers. During World War II and for some time afterward, paper was in short supply. Crosby printed the magazine on a variety of different sizes, colors, and types of paper stock printed by different printers, stuffed into a by folder. She printed 1,000 copies of each issue, and as she had done with the Black Sun Press, giving special treatment to 100 or so deluxe copies that featured original artwork byRomare Bearden

Romare Bearden (, ) (September 2, 1911 – March 12, 1988) was an American artist, author, and songwriter. He worked with many types of media including cartoons, oils, and collages. Born in Charlotte, North Carolina, Bearden grew up in New York C ...

, Henri Matisse

Henri Émile Benoît Matisse (; 31 December 1869 – 3 November 1954) was a French visual arts, visual artist, known for both his use of colour and his fluid and original draughtsmanship. He was a drawing, draughtsman, printmaking, printmaker, ...

, and others. She secured contributions from a wide variety of well-known artists and writers, including: Louis Aragon

Louis Aragon (; 3 October 1897 – 24 December 1982) was a French poet who was one of the leading voices of the Surrealism, surrealist movement in France. He co-founded with André Breton and Philippe Soupault the surrealist review ''Littératur ...

, Kay Boyle

Kay Boyle (February 19, 1902 – December 27, 1992) was an American novelist, short story writer, educator, and political activist. Boyle is best known for her fiction, which often explored the intersections of personal and political themes. Her ...

, Gwendolyn Brooks

Gwendolyn Elizabeth Brooks (June 7, 1917 – December 3, 2000) was an American poet, author, and teacher. Her work often dealt with the personal celebrations and struggles of ordinary people in her community. She won the Pulitzer Prize for Poet ...

, Sterling A. Brown, Charles Bukowski, Albert Camus

Albert Camus ( ; ; 7 November 1913 – 4 January 1960) was a French philosopher, author, dramatist, journalist, world federalist, and political activist. He was the recipient of the 1957 Nobel Prize in Literature at the age of 44, the s ...

(''Letter to a German Friend,'' his first appearance in an English-language publication), Henri Cartier-Bresson

Henri Cartier-Bresson (; 22 August 1908 – 3 August 2004) was a French artist and Humanist photography, humanist photographer considered a master of candid photography, and an early user of 135 film, 35mm film. He pioneered the genre of street ...

, René Char, Paul Éluard

Paul Éluard (), born Eugène Émile Paul Grindel (; 14 December 1895 – 18 November 1952), was a French poet and one of the founders of the Surrealist movement.

In 1916, he chose the name Paul Éluard, a matronymic borrowed from his maternal ...

, Jean Genet

Jean Genet (; ; – ) was a French novelist, playwright, poet, essayist, and political activist. In his early life he was a vagabond and petty criminal, but he later became a writer and playwright. His major works include the novels '' The Th ...

, Natalia Ginzburg

Natalia Ginzburg (, ; ; 14 July 1916 – 7 October 1991) was an Italian author whose work explored family relationships, politics during and after the Fascist years and World War II, and philosophy. She wrote novels, short stories and essays, f ...

, Victor Hugo

Victor-Marie Hugo, vicomte Hugo (; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French Romanticism, Romantic author, poet, essayist, playwright, journalist, human rights activist and politician.

His most famous works are the novels ''The Hunchbac ...

, Weldon Kees, Robert Lowell

Robert Traill Spence Lowell IV (; March 1, 1917 – September 12, 1977) was an American poet. He was born into a Boston Brahmin family that could trace its origins back to the ''Mayflower''. His family, past and present, were important subjects ...

, Henri Matisse, Henry Miller, Eugenio Montale

Eugenio Montale (; 12 October 1896 – 12 September 1981) was an Italian poet, prose writer, editor and translator. In 1975, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature for 'for his distinctive poetry which, with great artistic sensitivity, has ...

, Anaïs Nin, Charles Olson

Charles John Olson (27 December 1910 – 10 January 1970) was a second generation modernist United States poetry, American poet who was a link between earlier Literary modernism, modernist figures such as Ezra Pound and William Carlos Williams an ...

, Pablo Picasso

Pablo Diego José Francisco de Paula Juan Nepomuceno María de los Remedios Cipriano de la Santísima Trinidad Ruiz y Picasso (25 October 1881 – 8 April 1973) was a Spanish painter, sculptor, printmaker, Ceramic art, ceramicist, and Scenic ...

, Francis Ponge

Francis Jean Gaston Alfred Ponge (; 27 March 1899 – 6 August 1988) was a French poet. He developed a form of prose poem, minutely examining everyday objects. He was the third recipient of the Neustadt International Prize for Literature in 1974.

...

, Kenneth Rexroth

Kenneth Charles Marion Rexroth (December 22, 1905 – June 6, 1982) was an American poet, translator, and critical essayist. He is regarded as a central figure in the San Francisco Renaissance, and paved the groundwork for the movement. Althoug ...

, Arthur Rimbaud

Jean Nicolas Arthur Rimbaud (, ; ; 20 October 1854 – 10 November 1891) was a French poet known for his transgressive and surreal themes and for his influence on modern literature and arts, prefiguring surrealism.

Born in Charleville, he s ...

, Yannis Ritsos, Jean-Paul Sartre

Jean-Paul Charles Aymard Sartre (, ; ; 21 June 1905 – 15 April 1980) was a French philosopher, playwright, novelist, screenwriter, political activist, biographer, and literary criticism, literary critic, considered a leading figure in 20th ...

(''The End of the War''), Karl Shapiro

Karl Jay Shapiro (November 10, 1913 – May 14, 2000) was an American poet. He was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1945 for his collection ''V-Letter and Other Poems''. He was appointed the fifth Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to ...

, Stephen Spender