Marshall Taylor on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

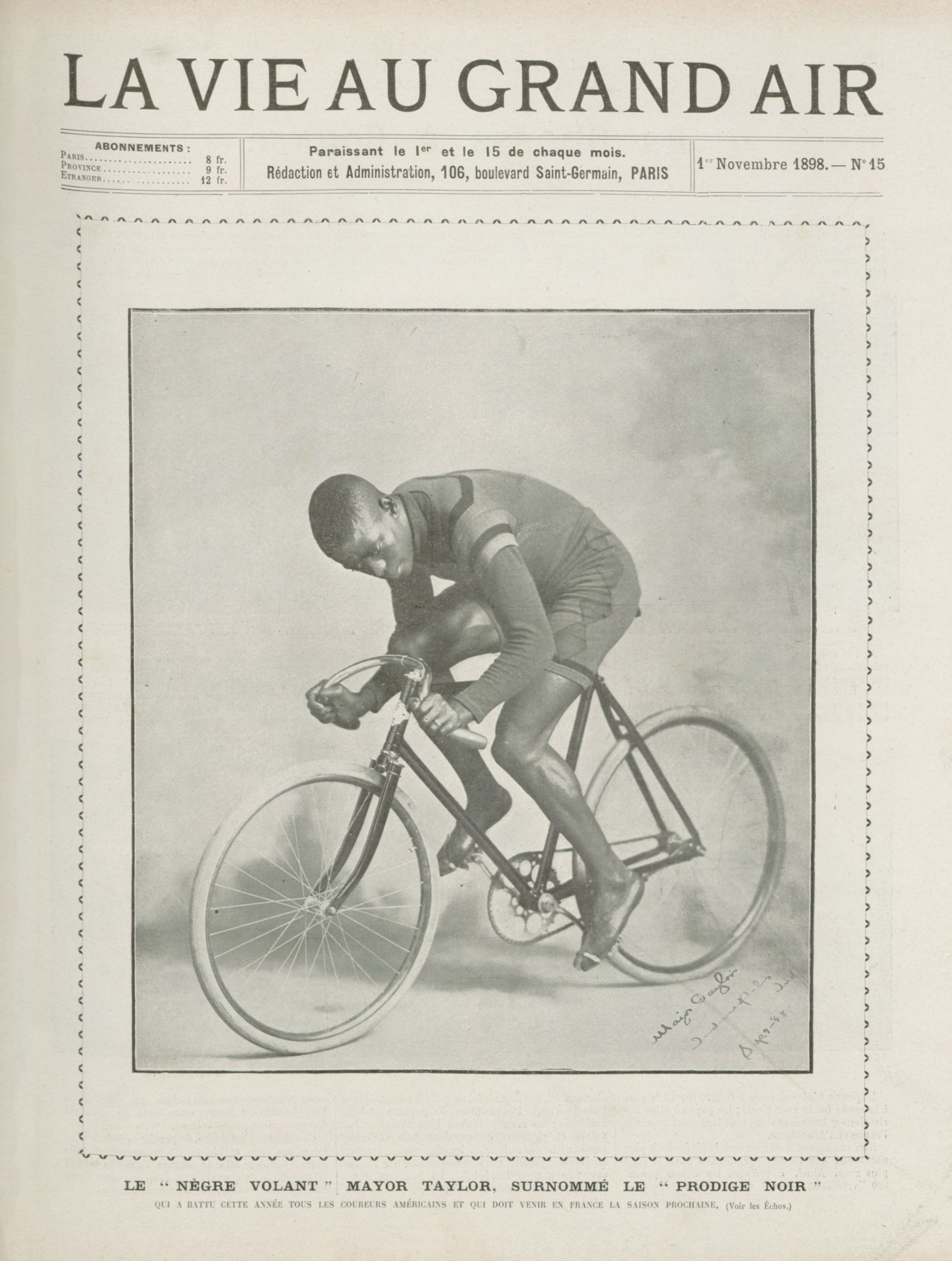

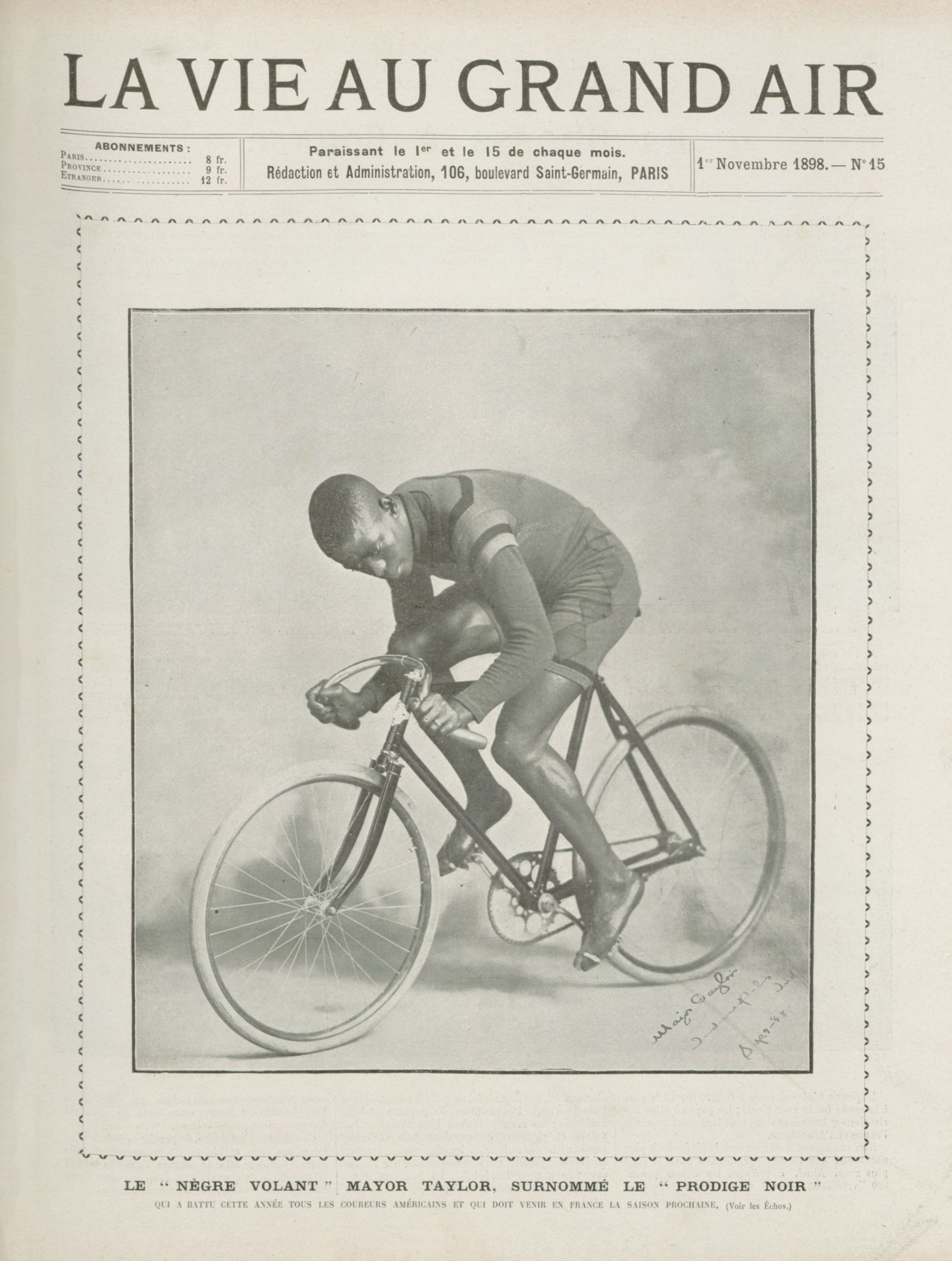

Marshall Walter "Major" Taylor (November 26, 1878 – June 21, 1932) was an

Taylor left the Hay and Willits shop in 1892 or early 1893 to take a job as head trainer for Harry T. Hearsey's bicycle shop in Indianapolis, teaching local residents how to ride. While working at Hearsey's shop, Taylor got to know Louis D. "Birdie" Munger, a former

Taylor left the Hay and Willits shop in 1892 or early 1893 to take a job as head trainer for Harry T. Hearsey's bicycle shop in Indianapolis, teaching local residents how to ride. While working at Hearsey's shop, Taylor got to know Louis D. "Birdie" Munger, a former

In 1895, Taylor and Munger relocated from Indianapolis to Worcester. At that time it was a center of the U.S.

In 1895, Taylor and Munger relocated from Indianapolis to Worcester. At that time it was a center of the U.S.

Taylor turned professional in 1896, at the age of eighteen, and soon emerged as the "most formidable racer in America." Taylor's first professional race took place in front of 5,000 spectators on December 5, 1896. He competed in a half-mile handicap event on an indoor track at

Taylor turned professional in 1896, at the age of eighteen, and soon emerged as the "most formidable racer in America." Taylor's first professional race took place in front of 5,000 spectators on December 5, 1896. He competed in a half-mile handicap event on an indoor track at

Taylor initially raced for Munger's Worcester Cycle Manufacturing Company. After the company went into receivership in 1897 he joined other racing teams. Taylor competed in his first full year on the professional racing circuit in 1897. Early in the season, at the Bostonian Cycle Club's "Blue Ribbon Meet" on May 19, 1897, Taylor rode a Comet bicycle to win first place in the one-mile open professional race. On June 26, he won a quarter-mile () race at the track at

Taylor initially raced for Munger's Worcester Cycle Manufacturing Company. After the company went into receivership in 1897 he joined other racing teams. Taylor competed in his first full year on the professional racing circuit in 1897. Early in the season, at the Bostonian Cycle Club's "Blue Ribbon Meet" on May 19, 1897, Taylor rode a Comet bicycle to win first place in the one-mile open professional race. On June 26, he won a quarter-mile () race at the track at  Early in the 1898 racing season Taylor beat Bald at Manhattan Beach, but lost to Eddie McDuffie at

Early in the 1898 racing season Taylor beat Bald at Manhattan Beach, but lost to Eddie McDuffie at

At the 1899 world championships in

At the 1899 world championships in

African-American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American ...

professional cyclist

Cycling, also, when on a two-wheeled bicycle, called bicycling or biking, is the use of cycles for transport, recreation, exercise or sport. People engaged in cycling are referred to as "cyclists", "bicyclists", or "bikers". Apart from two ...

. Even by modern cycling standards, Taylor could be considered the greatest American sprinter of all time.

He was born and raised in Indianapolis, where he worked in bicycle shops and began racing multiple distances in the track

Track or Tracks may refer to:

Routes or imprints

* Ancient trackway, any track or trail whose origin is lost in antiquity

* Animal track, imprints left on surfaces that an animal walks across

* Desire path, a line worn by people taking the short ...

and road

A road is a linear way for the conveyance of traffic that mostly has an improved surface for use by vehicles (motorized and non-motorized) and pedestrians. Unlike streets, the main function of roads is transportation.

There are many types of ...

disciplines of cycling. As a teenager, he moved to Worcester, Massachusetts

Worcester ( , ) is a city and county seat of Worcester County, Massachusetts, United States. Named after Worcester, England, the city's population was 206,518 at the 2020 census, making it the second- most populous city in New England after ...

, with his employer/coach/mentor and continued his successful amateur career, which included breaking track records.

Taylor turned professional in 1896, at the age of 18, living in cities on the East Coast

East Coast may refer to:

Entertainment

* East Coast hip hop, a subgenre of hip hop

* "East Coast" (ASAP Ferg song), 2017

* "East Coast" (Saves the Day song), 2004

* East Coast FM, a radio station in Co. Wicklow, Ireland

* East Coast Swing, a f ...

and participating in multiple track events including six-day races. He moved his focus to the sprint

Sprint may refer to:

Aerospace

*Spring WS202 Sprint, a Canadian aircraft design

*Sprint (missile), an anti-ballistic missile

Automotive and motorcycle

* Alfa Romeo Sprint, automobile produced by Alfa Romeo between 1976 and 1989

* Chevrolet Sprin ...

event in 1897, competing in a national racing circuit, winning many races and gaining popularity with the public. In 1898 and 1899, he set numerous world records

A world record is usually the best global and most important performance that is ever recorded and officially verified in a specific skill, sport, or other kind of activity. The book ''Guinness World Records'' and other world records organization ...

in race distances ranging from the quarter-mile () to the two-mile ().

Taylor won the 1-mile sprint event

Sprinting is running over a short distance at the top-most speed of the body in a limited period of time. It is used in many sports that incorporate running, typically as a way of quickly reaching a target or goal, or avoiding or catching an op ...

at the 1899 world track championships to become the first African American to achieve the level of cycling world champion

A world championship is generally an international competition open to elite competitors from around the world, representing their nations, and winning such an event will be considered the highest or near highest achievement in the sport, game, ...

and the second black

Black is a color which results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without hue, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness. Black and white ha ...

athlete to win a world championship in any sport (following Canadian

Canadians (french: Canadiens) are people identified with the country of Canada. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Canadians, many (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of ...

boxer George Dixon, 1890). Taylor was also a national sprint champion in 1899 and 1900. He raced in the U.S., Europe and Australasia

Australasia is a region that comprises Australia, New Zealand and some neighbouring islands in the Pacific Ocean. The term is used in a number of different contexts, including geopolitically, physiogeographically, philologically, and ecolo ...

from 1901 to 1904, beating the world's best riders. After a -year hiatus, he made a comeback in 1907–1909, before retiring at age 32 to his home in Worcester in 1910.

Towards the end of his life Taylor faced severe financial difficulties. He spent the final two years of his life in Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

, Illinois, where he died of a heart attack in 1932. Throughout his career he challenged the racial prejudice he encountered on and off the track and became a pioneering role model for other athletes facing racial discrimination. Several cycling clubs, trails, and events in the U.S. have been named in his honor, as well as the Major Taylor Velodrome

The Major Taylor Velodrome is an outdoor, concrete velodrome in Indianapolis, Indiana, U.S., named for 1899 cycling world champion Major Taylor. The track with 28 degree banked turns and 9 degree straights. The Velodrome is located immediately no ...

in Indianapolis and Major Taylor Boulevard in Worcester. Other tributes include memorials and historic markers in Worcester, Indianapolis, and at his gravesite in Chicago. He has also been memorialized in film, music and fashion.

Early life

Marshall Walter Taylor was the son of Gilbert Taylor, aCivil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polic ...

veteran, and Saphronia Kelter Taylor. His parents migrated from Louisville, Kentucky

Louisville ( , , ) is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky and the 28th most-populous city in the United States. Louisville is the historical seat and, since 2003, the nominal seat of Jefferson County, on the Indiana borde ...

, and settled on a farm in Bucktown, a rural area on the western edge of Indianapolis, Indiana. Taylor, who was born on November 26, 1878, in Indianapolis was one of eight children in the family that included five girls and three boys. Around 1887, his father began working in Indianapolis as a coachman

A coachman is an employee who drives a coach or carriage, a horse-drawn vehicle designed for the conveyance of passengers. A coachman has also been called a coachee, coachy, whip, or hackman.

The coachman's first concern is to remain in full ...

for a wealthy white family named Southard.

When Taylor was a child he occasionally accompanied his father to work. Taylor soon became a close friend of the Southards' son, Daniel, who was the same age. Approximately from the age of 8 until he was about 12, Taylor lived with the family and along with Daniel was tutored at their home. Taylor's living arrangement with the Southards provided him with more advantages than his parents could provide; however, this period of his life abruptly ended when the Southards moved to Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

, Illinois. Taylor, who remained in Indianapolis, returned to live at his parents' home and "was soon thrust into the real world."

The Southards provided Taylor with his first bicycle. By 1891 or early 1892, he had become such an expert trick rider that Tom Hay, an Indianapolis bicycle shop owner, hired him to perform bicycle stunts in front of the Hay and Willits bicycle shop. Taylor earned $6 a week for cleaning the shop and performing the stunts, plus a free bicycle worth $35. It is likely that Taylor received his nickname of "Major" because he performed the cycling stunts wearing a military uniform.

Taylor left the Hay and Willits shop in 1892 or early 1893 to take a job as head trainer for Harry T. Hearsey's bicycle shop in Indianapolis, teaching local residents how to ride. While working at Hearsey's shop, Taylor got to know Louis D. "Birdie" Munger, a former

Taylor left the Hay and Willits shop in 1892 or early 1893 to take a job as head trainer for Harry T. Hearsey's bicycle shop in Indianapolis, teaching local residents how to ride. While working at Hearsey's shop, Taylor got to know Louis D. "Birdie" Munger, a former high-wheel bicycle

The penny-farthing, also known as a high wheel, high wheeler or ordinary, is an early type of bicycle. It was popular in the 1870s and 1880s, with its large front wheel providing high speeds (owing to its travelling a large distance for every ...

racer who owned the Munger Cycle Manufacturing Company, a racing bicycle

A racing bicycle, also known as a road bike is a bicycle designed for competitive road cycling, a sport governed by and according to the rules of the Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI).

Racing bicycles are designed for maximum performance ...

factory in Indianapolis. (Munger later established the Worcester Cycle Manufacturing Company factory in Worcester, Massachusetts

Worcester ( , ) is a city and county seat of Worcester County, Massachusetts, United States. Named after Worcester, England, the city's population was 206,518 at the 2020 census, making it the second- most populous city in New England after ...

.) With a shared interest in bicycle racing, the two became friends and Munger hired the teenaged Taylor to work odd jobs that included sending Taylor to area high schools and colleges to train cyclists and promote Munger's line of racing bicycles. Munger had also "made up his mind to make Taylor a champion" and coached him to become a racer.

Early years and East Coast move

Although he competed in bothroad

A road is a linear way for the conveyance of traffic that mostly has an improved surface for use by vehicles (motorized and non-motorized) and pedestrians. Unlike streets, the main function of roads is transportation.

There are many types of ...

and track races during his amateur career, Taylor excelled in the track sprints, especially the race. The first cycling race Taylor won was a amateur event in Indianapolis in 1890. He received a 15-minute handicap (head start) in the road race because of his young age. Taylor subsequently traveled to Peoria, Illinois

Peoria ( ) is the county seat of Peoria County, Illinois, United States, and the largest city on the Illinois River. As of the 2020 census, the city had a population of 113,150. It is the principal city of the Peoria Metropolitan Area in Centr ...

, to compete in another meet, finishing in third place in the under-16 age category.

Taylor encountered racial prejudice throughout his racing career from some of his competitors. In addition, some local track owners feared that other cyclists would refuse to compete if Taylor was present for a bicycle race and banned him from their tracks. In 1893, for example, after 15-year-old Taylor beat a one-mile amateur track record, he was "hooted" and then barred from the track. Taylor joined the See-Saw Cycling Club

A cycling club is a society for cyclists. Clubs tend to be mostly local, and can be general or specialised. In the United Kingdom, for example, the Cyclists' Touring Club, (CTC) is a national cycling association; the Tricycle Association, Tan ...

, which was formed by black

Black is a color which results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without hue, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness. Black and white ha ...

cyclists of Indianapolis who were unable to join the local all-white

White is the lightness, lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully diffuse reflection, reflect and scattering, scatter all the ...

Zig-Zag Cycling Club.

Major Taylor won his first significant cycling competition on June 30, 1895, when he was the only rider to finish a grueling road race near his hometown of Indianapolis. During the race Taylor received threats from his white competitors, who did not know that he had entered the event until the start of the race. A few days later, on July 4, 1895, Taylor won a ten-mile road race in Indianapolis that made him eligible to compete at the national championships for black racers in Chicago. Later that summer, he won the ten-mile championship race in Chicago by ten lengths and set a new record for black cyclists of 27:32.

In 1895, Taylor and Munger relocated from Indianapolis to Worcester. At that time it was a center of the U.S.

In 1895, Taylor and Munger relocated from Indianapolis to Worcester. At that time it was a center of the U.S. bicycle industry The bicycle industry or cycling industry can broadly be defined as the industry concerned with bicycles and cycling. It includes at least bicycle manufacturers, part or component manufacturers, and accessory manufacturers. It can also include dis ...

that included half a dozen factories and thirty bicycle shops. Munger, who was Taylor's employer, lifelong friend, and mentor, had decided to move his bicycle manufacturing business to the state of Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut assachusett writing systems, məhswatʃəwiːsət'' English: , ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is the most populous U.S. state, state in the New England ...

, which was also a more tolerant area of the country.

Munger and Charles Boyd, a business partner, established the Worcester Cycle Manufacturing Company with factories in Worcester, and Middletown, Connecticut

Middletown is a city located in Middlesex County, Connecticut, United States, Located along the Connecticut River, in the central part of the state, it is south of Hartford. In 1650, it was incorporated by English settlers as a town under it ...

. For Taylor, who continued to work for Munger as a bicycle mechanic

A bicycle mechanic or bike mechanic is a mechanic who can perform a wide range of repairs on bicycles. Bicycle mechanics can be employed in various types of stores, ranging from large department stores to small local bike shops; cycling teams, or ...

and messenger between the company's two factory locations, the move to the East Coast

East Coast may refer to:

Entertainment

* East Coast hip hop, a subgenre of hip hop

* "East Coast" (ASAP Ferg song), 2017

* "East Coast" (Saves the Day song), 2004

* East Coast FM, a radio station in Co. Wicklow, Ireland

* East Coast Swing, a f ...

offered "higher visibility, larger crowds, increased sponsorship dollars, and greater access to world-class cycling venues." After Taylor's relocation to Massachusetts, he joined the all-black Albion Cycling Club in 1895 and trained at YMCA

YMCA, sometimes regionally called the Y, is a worldwide youth organization based in Geneva, Switzerland, with more than 64 million beneficiaries in 120 countries. It was founded on 6 June 1844 by George Williams (philanthropist), Georg ...

in Worcester. Taylor is first mentioned in ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' on September 26, 1895, as a competitor in the Citizen Handicap event, a ten-mile race on Ocean Parkway in Brooklyn

Brooklyn () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Kings County, in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. Kings County is the most populous Administrative divisions of New York (state)#County, county in the State of New York, ...

, New York. Taylor raced with a 1:30 handicap in a field of 200 competitors that included nine scratch riders.

In 1896, Taylor entered numerous races in the Northeastern states

The Northeastern United States, also referred to as the Northeast, the East Coast, or the American Northeast, is a geographic region of the United States. It is located on the Atlantic coast of North America, with Canada to its north, the Southe ...

of Massachusetts, New Jersey

New Jersey is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic States, Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern United States, Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York (state), New York; on the ea ...

, and Connecticut

Connecticut () is the southernmost state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It is bordered by Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. Its cap ...

. After winning a ten-mile road race in Worcester, Taylor competed in the Irvington–Millburn race in New Jersey, also known as the Derby of the East. Within half a mile () of the finish line, someone startled Taylor by tossing ice water into his face and he finished in 23rd place. Taylor's first major East Coast race was in a League of American Wheelmen

The League of American Bicyclists (LAB), officially the League of American Wheelmen, is a membership organization that promotes cycling for fun, fitness and transportation through advocacy and education.

A Section 501(c)(3) nonprofit organizatio ...

(LAW) one-mile contest in New Haven

New Haven is a city in the U.S. state of Connecticut. It is located on New Haven Harbor on the northern shore of Long Island Sound in New Haven County, Connecticut and is part of the New York City metropolitan area. With a population of 134,023 ...

, Connecticut, where he started in last place but won the event. In August 1896, Taylor made a trip to Indianapolis, where he set an unofficial new track record of 2:11 for a distance of one mile at the Capital City velodrome

A velodrome is an arena for track cycling. Modern velodromes feature steeply banked oval tracks, consisting of two 180-degree circular bends connected by two straights. The straights transition to the circular turn through a moderate easement c ...

, beating Walter Sanger's official track record of 2:19 . (Taylor could not compete with Sanger, a professional racer, in a head-to-head contest because he was still an amateur.) Taylor's final amateur race took place on November 26, 1896, in the 25-mile Tatum Handicap at Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of Hispan ...

, New York. Taylor finished the race in 14th place.

Professional career

1896: First races

Taylor turned professional in 1896, at the age of eighteen, and soon emerged as the "most formidable racer in America." Taylor's first professional race took place in front of 5,000 spectators on December 5, 1896. He competed in a half-mile handicap event on an indoor track at

Taylor turned professional in 1896, at the age of eighteen, and soon emerged as the "most formidable racer in America." Taylor's first professional race took place in front of 5,000 spectators on December 5, 1896. He competed in a half-mile handicap event on an indoor track at New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the U ...

's Madison Square Garden II

Madison Square Garden (1890–1926) was an indoor arena in New York City, the second by that name, and the second and last to be located at 26th Street (Manhattan), 26th Street and Madison Avenue in Manhattan. Opened in 1890 at the cost of about ...

on the opening day of a multi-day event. Although the main event was a six-day race fm December 6–12, other contests in shorter distances were held on December 5 to entertain the crowd. These races included the half-mile handicap for professionals in which Taylor competed, a half-mile race between Jay Eaton and Teddy Goodman, and a half-mile scratch race

A scratch race is a track cycling race in which all riders start together and the objective is simply to be first over the finish line after a certain number of laps.

UCI regulations specify that a scratch race should be held over 15 km for E ...

. In addition, there were half-mile scratch and handicap races for amateurs.

Taylor began the half-mile handicap race on December 5, with a advantage over the scratch racers. He beat a field of competitors that included Tom Cooper, Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

's A.C. Meixwell, and scratch rider Eddie C. Bald, who represented New York's Syracuse

Syracuse may refer to:

Places Italy

*Syracuse, Sicily, or spelled as ''Siracusa''

*Province of Syracuse

United States

* Syracuse, New York

** East Syracuse, New York

** North Syracuse, New York

* Syracuse, Indiana

*Syracuse, Kansas

*Syracuse, M ...

, and rode a Barnes bicycle. Taylor won the race riding Munger's "Birdie Special" bicycle and beat Bald by in a sprint to the finish.

From December 6–12, 1896, Taylor participated as one of 28 competitors in a six-day event at Madison Square Garden. Although Taylor had just become a professional, he had achieved enough notoriety, possibly because of his stunning win on December 5, to be listed among the "American contestants" that also included A.A. Hansen (the Minneapolis "rainmaker") and Teddy Goodman. In addition, many "experts from abroad" participated in the meet such as Switzerland's Albert Schock, Germany's Frank J. Waller, Frank Forster, and Ed von Hoeg, and Canada's Burns W. Pierce. Several countries were represented in the event, including Scotland, Wales, France, England, and Denmark.

As the fascination with six-day races spread across the Atlantic from its origins in the United Kingdom, their appeal to base instincts attracted large crowds. The more spectators who paid at the gate, the bigger the prizes, which provided riders with the incentive to stay awake–or be kept awake–in order to ride the greatest distance. To prepare for the event, Taylor went to Brooklyn, where he became a member of the South Brooklyn Wheelmen. An estimated crowd of 6,000 spectators attended the final day of the Madison Square Garden races in December 1896. During these long, grueling races, riders suffered delusions and hallucinations, which may have been caused by exhaustion, lack of sleep, or perhaps use of drugs.

Madison Square Garden's six-day event in 1896 was the longest race Taylor had ever entered. After Taylor refused to continue racing on the final day of the long-distance competition, exhausted from physical exertion and lack of sleep, a ''Bearnings'' reporter overheard him comment: "I cannot go on with safety, for there is a man chasing me around the ring with a knife in his hand." Taylor completed a total of in 142 hours of racing to finish in eighth place. Teddy Hale, the race winner, completed and took home $5,000 in prize money. Taylor never competed in another race that long.

After Taylor's move to the East Coast in 1896, he initially lived in Worcester, where he worked for Munger, and in Middletown, the site of another of Munger's cycle factories. Taylor also lived in other eastern cities, such as South Brooklyn, where he once trained, but it is not known how long he still resided in New York after he became a professional racer.

1897–1898: Fame and records

Taylor initially raced for Munger's Worcester Cycle Manufacturing Company. After the company went into receivership in 1897 he joined other racing teams. Taylor competed in his first full year on the professional racing circuit in 1897. Early in the season, at the Bostonian Cycle Club's "Blue Ribbon Meet" on May 19, 1897, Taylor rode a Comet bicycle to win first place in the one-mile open professional race. On June 26, he won a quarter-mile () race at the track at

Taylor initially raced for Munger's Worcester Cycle Manufacturing Company. After the company went into receivership in 1897 he joined other racing teams. Taylor competed in his first full year on the professional racing circuit in 1897. Early in the season, at the Bostonian Cycle Club's "Blue Ribbon Meet" on May 19, 1897, Taylor rode a Comet bicycle to win first place in the one-mile open professional race. On June 26, he won a quarter-mile () race at the track at Manhattan Beach, Brooklyn

Manhattan Beach is a residential neighborhood in the New York City borough of Brooklyn. It is bounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the south and east, by Sheepshead Bay on the north, and Brighton Beach to the west. Traditionally known as an Italian ...

. Taylor also beat Eddie Bald in a one-mile race in Reading, Pennsylvania

Reading ( ; Pennsylvania Dutch: ''Reddin'') is a city in and the county seat of Berks County, Pennsylvania, United States. The city had a population of 95,112 as of the 2020 census and is the fourth-largest city in Pennsylvania after Phila ...

, but finished fourth in the prestigious LAW convention in Philadelphia.

As a professional racer Taylor continued to experience racial prejudice as a black cyclist in a white-dominated sport. In November and December 1897, when the circuit extended to the racially-segregated South, local race promoters refused to let Taylor compete because he was black. Taylor returned to Massachusetts for the remainder of the season and Eddie Bald became the American sprint champion in 1897. Despite the obstacles, Taylor was determined to race.

In the early years of his professional racing career, Taylor's reputation continued to increase as he competed in and won more races. Newspapers began referring to him as the "Worcester Whirlwind," the "Black Cyclone," the "Ebony Flyer," the "Colored Cyclone," and the "Black Zimmerman," among other nicknames. He also gained popularity among the spectators. One of his fans was President Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

who kept track of Taylor throughout his seventeen-year racing career.

Early in the 1898 racing season Taylor beat Bald at Manhattan Beach, but lost to Eddie McDuffie at

Early in the 1898 racing season Taylor beat Bald at Manhattan Beach, but lost to Eddie McDuffie at Cambridge, Massachusetts

Cambridge ( ) is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States. As part of the Greater Boston, Boston metropolitan area, the cities population of the 2020 United States Census, 2020 U.S. census was 118,403, making it the fourth most ...

, in a paced race. On July 17 at Philadelphia, Taylor won his biggest victories of the season: first place in the one-mile championship and second place in the one-mile handicap races. On August 27, in a head-to-head race with Jimmy Michael

Jimmy Michael (18 August 1877 – 21 November 1904) was a Welsh world cycling champion and one of the top riders in the sport for several years.

Origins

Jimmy Michael was tall. He was born in Aberaman, Cynon Valley, Wales. His parents had a b ...

of Wales, Taylor set a new world record of 1:41 for a one-mile paced match and beat the Welsh racer to the finish by .

Taylor was among several top cyclists who could claim the national championship in 1898; however, scoring variations and the formation of a new cycling league that year "clouded" his claim to the title. Early in the year a group of professional racers that included Taylor had left the LAW to join a rival group, the American Racing Cyclists' Union (ARCU), and its professional racing group, the National Cycling Association (NCA). During the ARCU sprint championship in St. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

and Cape Girardeau, Missouri

Cape Girardeau ( , french: Cap-Girardeau ; colloquially referred to as "Cape") is a city in Cape Girardeau and Scott Counties in the U.S. state of Missouri. At the 2020 census, the population was 39,540. The city is one of two principal citi ...

, Taylor, who was a devout Baptist

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christianity, Christian believers only (believer's baptism), and doing so by complete Immersion baptism, immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe ...

, refused to compete for religious reasons in the finals of the championship races because they were held on a Sunday. As a result of Taylor's decision not to race in the finals at Cape Girardeau, the ARCU suspended him from membership. Taylor petitioned the LAW for reinstatement in 1898 and was accepted, but Tom Butler, who had remained a LAW member after the break-up, was declared the League's champion that year.

During 1898–99, at the peak of his cycling career, Taylor established seven world records

A world record is usually the best global and most important performance that is ever recorded and officially verified in a specific skill, sport, or other kind of activity. The book ''Guinness World Records'' and other world records organization ...

; the quarter-mile, the one-third-mile (), the half-mile, the two-thirds-mile (), the three-quarters-mile (), the one-mile, and the two-mile () distances. His one-mile world record of 1:41 from a standing start stood for 28 years.

1899: World sprint champion

Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the second-most populous city in Canada and most populous city in the Canadian province of Quebec. Founded in 1642 as '' Ville-Marie'', or "City of Mary", it is named after Mount Royal, the triple- ...

, Canada, Taylor won the one-mile sprint, to become the first African American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American ...

to win a world championship in cycling. Taylor was the second black athlete, after Canadian bantamweight boxer George Dixon of Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the capital city, state capital and List of municipalities in Massachusetts, most populous