Marcel Petiot on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Marcel André Henri Félix Petiot (17 January 1897 – 25 May 1946) was a French medical doctor and

Petiot's first murder victim might have been Louise Delaveau, an elderly patient's daughter with whom Petiot had an affair in 1926. Delaveau disappeared during May of that year, and neighbors later said they had seen Petiot load a trunk into his car. Police investigated but eventually dismissed her case as a runaway. That same year, Petiot campaigned for mayor of Villeneuve-sur-Yonne and hired somebody to disrupt a political debate with his opponent. He won, and while in office

Petiot's first murder victim might have been Louise Delaveau, an elderly patient's daughter with whom Petiot had an affair in 1926. Delaveau disappeared during May of that year, and neighbors later said they had seen Petiot load a trunk into his car. Police investigated but eventually dismissed her case as a runaway. That same year, Petiot campaigned for mayor of Villeneuve-sur-Yonne and hired somebody to disrupt a political debate with his opponent. He won, and while in office

In addition to those found in his basement, human remains were also found in a pit filled partly with

In addition to those found in his basement, human remains were also found in a pit filled partly with

"Dr. Petiot Will See You Now"

in ''Crime'' magazine {{DEFAULTSORT:Petiot, Marcel 1897 births 1946 deaths 20th-century French criminals Burials at Ivry Cemetery Executed French people Executed French serial killers Antisemitic attacks and incidents in Europe Executed people from Burgundy French male criminals French military personnel of World War I French murderers of children French people convicted of murder French people convicted of tax crimes French people of World War II French politicians Male serial killers Medical practitioners convicted of murdering their patients Medical serial killers People convicted of murder by France People executed by France by decapitation People executed by guillotine People executed by the Provisional Government of the French Republic People from Auxerre Poisoners

serial killer

A serial killer is typically a person who murders three or more persons,A

*

*

*

* with the murders taking place over more than a month and including a significant period of time between them. While most authorities set a threshold of three ...

. He was convicted of multiple murders after the discovery of the remains of 23 people in the basement of his home in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

. He is suspected of the murder of about 60 victims during his lifetime, although the true number remains unknown.

Early life

Marcel Petiot was born on 17 January 1897 inAuxerre

Auxerre ( , ) is the capital of the Yonne department and the fourth-largest city in Burgundy. Auxerre's population today is about 35,000; the urban area (''aire d'attraction'') comprises roughly 113,000 inhabitants. Residents of Auxerre are re ...

, Yonne

Yonne () is a department in the Bourgogne-Franche-Comté region in France. It is named after the river Yonne, which flows through it, in the country's north-central part. One of Bourgogne-Franche-Comté's eight constituent departments, it is l ...

, in north central France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan ar ...

. At the age of 11, Petiot fired his father's gun in class and propositioned a female classmate for sex. During his teenage years, he robbed a postbox and was charged with damage of public property and theft

Theft is the act of taking another person's property or services without that person's permission or consent with the intent to deprive the rightful owner of it. The word ''theft'' is also used as a synonym or informal shorthand term for so ...

. Petiot was ordered to undergo a psychiatric evaluation, resulting in charges being dismissed when it was judged that he had a mental illness

A mental disorder, also referred to as a mental illness or psychiatric disorder, is a behavioral or mental pattern that causes significant distress or impairment of personal functioning. Such features may be persistent, relapsing and remitt ...

.

Later accounts make various claims of Petiot's delinquency

Delinquent or delinquents may refer to:

* A person who commits a felony

* A juvenile delinquent, often shortened as delinquent is a young person (under 18) who fails to do that which is required by law; see juvenile delinquency

* A person who fa ...

and criminal acts during his youth, but it is unknown whether they were invented afterwards for public consumption. A psychiatrist reaffirmed Petiot's mental illness on 26 March 1914. After being expelled from school many times, he finished his education in a special academy in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. ...

in July 1915.

Petiot volunteered for the French Army in World War I

During World War I, France was one of the Triple Entente powers allied against the Central Powers. Although fighting occurred worldwide, the bulk of the conflict in Europe occurred in Belgium, Luxembourg, France and Alsace-Lorraine along what cam ...

, entering service in January 1916. He was wounded and gassed during the Second Battle of the Aisne

The Second Battle of the Aisne (french: Bataille du Chemin des Dames or french: Seconde bataille de l'Aisne, 16 April – mid-May 1917) was the main part of the Nivelle Offensive, a Franco-British attempt to inflict a decisive defeat on the Germ ...

, and exhibited more symptoms of a mental breakdown

A mental disorder, also referred to as a mental illness or psychiatric disorder, is a behavioral or mental pattern that causes significant distress or impairment of personal functioning. Such features may be persistent, relapsing and remitt ...

. Petiot was sent to various rest homes, where he was arrested for stealing army blankets, morphine

Morphine is a strong opiate that is found naturally in opium, a dark brown resin in poppies ('' Papaver somniferum''). It is mainly used as a pain medication, and is also commonly used recreationally, or to make other illicit opioids. Ther ...

, and other army supplies, as well as wallets, photographs, and letters; he was jailed in Orléans

Orléans (;"Orleans"

(US) and Fleury-les-Aubrais Fleury-les-Aubrais () is a commune in the Loiret department, Centre-Val de Loire, France. It is a northern suburb of Orléans. As a part of German-occupied France The Military Administration in France (german: Militärverwaltung in Frank ...

, Petiot was again diagnosed with various mental illnesses, but was returned to the front in June 1918. He was transferred three weeks later after he allegedly injured his own foot with a grenade, but was attached to a new regiment in September. A new diagnosis was enough to get him discharged with a disability pension.

(US) and Fleury-les-Aubrais Fleury-les-Aubrais () is a commune in the Loiret department, Centre-Val de Loire, France. It is a northern suburb of Orléans. As a part of German-occupied France The Military Administration in France (german: Militärverwaltung in Frank ...

Medical and political career

After the war, Petiot entered the accelerated education program intended for war veterans, completed medical school in eight months, and became an intern at the mental hospital inÉvreux

Évreux () is a commune in and the capital of the department of Eure, in the French region of Normandy.

Geography

The city is on the Iton river.

Climate

History

In late Antiquity, the town, attested in the fourth century CE, was named ...

. He received his medical degree in December 1921 and relocated to Villeneuve-sur-Yonne, where he received payment for his services both from the patients and from government medical assistance funds. At this time Petiot was already using addictive narcotics. While working at Villeneuve-sur-Yonne, he gained a reputation for dubious medical practices, such as supplying narcotics and performing illegal abortion

Abortion is the termination of a pregnancy by removal or expulsion of an embryo or fetus. An abortion that occurs without intervention is known as a miscarriage or "spontaneous abortion"; these occur in approximately 30% to 40% of pregn ...

s, as well as for petty theft.

Petiot's first murder victim might have been Louise Delaveau, an elderly patient's daughter with whom Petiot had an affair in 1926. Delaveau disappeared during May of that year, and neighbors later said they had seen Petiot load a trunk into his car. Police investigated but eventually dismissed her case as a runaway. That same year, Petiot campaigned for mayor of Villeneuve-sur-Yonne and hired somebody to disrupt a political debate with his opponent. He won, and while in office

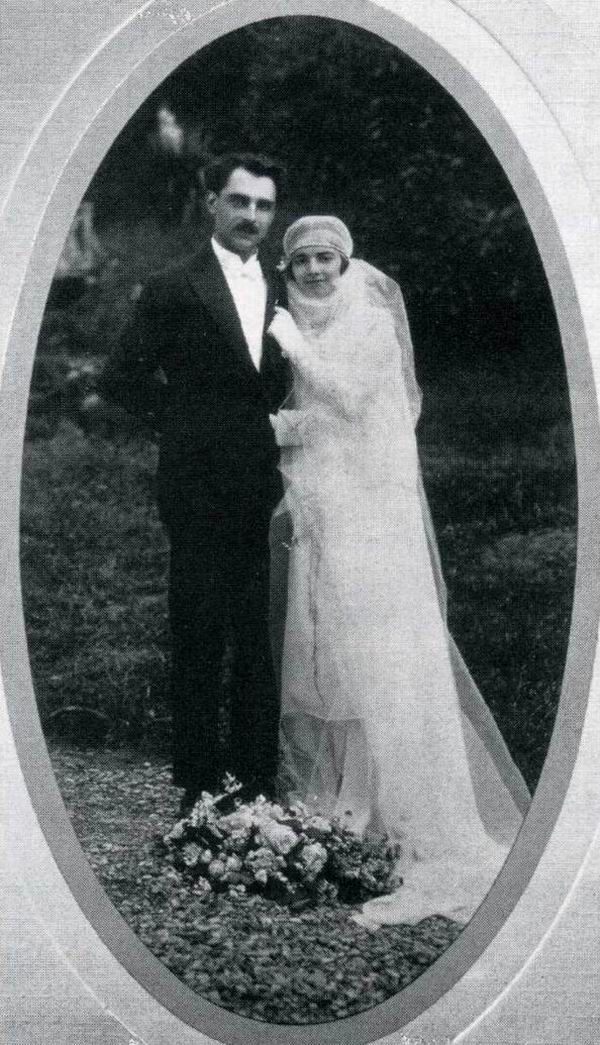

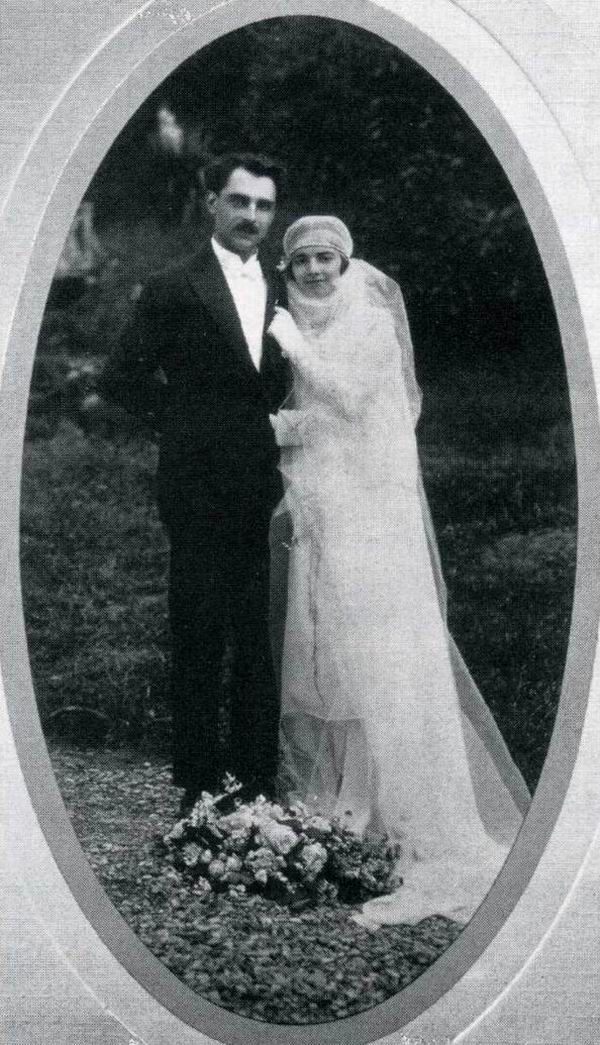

Petiot's first murder victim might have been Louise Delaveau, an elderly patient's daughter with whom Petiot had an affair in 1926. Delaveau disappeared during May of that year, and neighbors later said they had seen Petiot load a trunk into his car. Police investigated but eventually dismissed her case as a runaway. That same year, Petiot campaigned for mayor of Villeneuve-sur-Yonne and hired somebody to disrupt a political debate with his opponent. He won, and while in office embezzled

Embezzlement is a crime that consists of withholding assets for the purpose of conversion of such assets, by one or more persons to whom the assets were entrusted, either to be held or to be used for specific purposes. Embezzlement is a type ...

town funds. The next year, Petiot married Georgette Lablais, the 23-year-old daughter of a wealthy landowner and butcher in Seignelay

Seignelay () is a commune in the Yonne department in Bourgogne-Franche-Comté in north-central France. The regional historian Vaast Barthélemy Henry (1797–1884) was born in Seignelay.

See also

*Communes of the Yonne department

The follo ...

. Their son Gerhardt was born in April 1928.

The prefect

Prefect (from the Latin ''praefectus'', substantive adjectival form of ''praeficere'': "put in front", meaning in charge) is a magisterial title of varying definition, but essentially refers to the leader of an administrative area.

A prefect's ...

of Yonne received many complaints about Petiot's thefts and dubious financial dealings. He was eventually suspended as mayor in August 1931 and resigned. However, Petiot still had many supporters, and the village council also resigned in sympathy with him. Five weeks later, on 18 October, he was elected as a councilor of Yonne Département. In 1932, he was accused of stealing electricity from the village and lost his council seat. By this time he had already relocated to Paris.

In Paris, Petiot attracted patients by using fake credentials, and built an impressive reputation for his practice at 66 Rue de Caumartin. However, there were rumors of illegal abortions and excessive prescriptions of addictive remedies. In 1936, Petiot was appointed ''médecin d'état-civil'', with authority to write death certificate

A death certificate is either a legal document issued by a medical practitioner which states when a person died, or a document issued by a government civil registration office, that declares the date, location and cause of a person's death, as ...

s. The same year, he was institutionalized briefly for kleptomania

Kleptomania is the inability to resist the urge to steal items, usually for reasons other than personal use or financial gain. First described in 1816, kleptomania is classified in psychiatry as an impulse control disorder. Some of the main ch ...

, but was released the next year. He persisted in tax evasion

Tax evasion is an illegal attempt to defeat the imposition of taxes by individuals, corporations, trusts, and others. Tax evasion often entails the deliberate misrepresentation of the taxpayer's affairs to the tax authorities to reduce the tax ...

.

World War II activities

After the 1940 German defeat of France, French citizens were drafted forforced labor in Germany

The use of slave and forced labour in Nazi Germany (german: Zwangsarbeit) and throughout German-occupied Europe during World War II took place on an unprecedented scale. It was a vital part of the German economic exploitation of conquered ...

. Petiot provided false medical disability certificates to people who were drafted. He also treated the illnesses of workers who had returned. In July 1942, he was convicted of overprescribing narcotics, even though two addicts who would have testified against him had disappeared. He was fined 2,400 franc

The franc is any of various units of currency. One franc is typically divided into 100 centimes. The name is said to derive from the Latin inscription ''francorum rex'' (King of the Franks) used on early French coins and until the 18th centur ...

s.

Petiot later claimed that during the period of German occupation, he was engaged in Resistance activities. He supposedly developed secret weapons that killed Germans without leaving forensic evidence

Forensic identification is the application of forensic science, or "forensics", and technology to identify specific objects from the trace evidence they leave, often at a crime scene or the scene of an accident. Forensic means "for the courts".

H ...

, planted booby traps all over Paris, had high-level meetings with Allied commanders, and worked with a (nonexistent) group of Spanish anti-fascists.

There is no evidence for any of these statements. However, in 1980, he was cited by former U.S. spymaster Col. John F. Grombach as a World War II source. Grombach had been founder and commander of a small independent espionage

Espionage, spying, or intelligence gathering is the act of obtaining secret or confidential information ( intelligence) from non-disclosed sources or divulging of the same without the permission of the holder of the information for a tang ...

agency, known later as " The Pond", which operated from 1942 to 1955. Grombach asserted that Petiot had reported the Katyn Forest massacre, German missile development at Peenemünde, and the names of Abwehr

The ''Abwehr'' ( German for ''resistance'' or ''defence'', but the word usually means ''counterintelligence'' in a military context; ) was the German military-intelligence service for the '' Reichswehr'' and the ''Wehrmacht'' from 1920 to 1944. ...

agents sent to the U.S. While these claims were not corroborated by any records of other intelligence services, in 2001, some "Pond" records were discovered, including a cable that mentioned Petiot.

Fraudulent escape network

Petiot's most lucrative activity during the Occupation was his false escape route. Using the codename "Dr. Eugène", Petiot pretended to have a means of getting people wanted by the Germans or theVichy government

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its terr ...

to safety outside France. Petiot claimed that he could arrange a passage to Argentina

Argentina (), officially the Argentine Republic ( es, link=no, República Argentina), is a country in the southern half of South America. Argentina covers an area of , making it the second-largest country in South America after Brazil, t ...

or elsewhere in South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the souther ...

through Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, In recognized minority languages of Portugal:

:* mwl, República Pertuesa is a country located on the Iberian Peninsula, in Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Macaronesian ...

, for a price of 25,000 francs

The franc is any of various units of currency. One franc is typically divided into 100 centimes. The name is said to derive from the Latin inscription ''francorum rex'' ( King of the Franks) used on early French coins and until the 18th cent ...

per person. Three accomplices, Raoul Fourrier, Edmond Pintard, and René-Gustave Nézondet, directed victims to "Dr. Eugène", including Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""T ...

, Resistance fighters, and ordinary criminals. Once victims were in his control, Petiot told them that Argentine officials required all entrants to the country to be inoculated against disease, and with this excuse injected them with cyanide

Cyanide is a naturally occurring, rapidly acting, toxic chemical that can exist in many different forms.

In chemistry, a cyanide () is a chemical compound that contains a functional group. This group, known as the cyano group, consists of ...

. He then took all their valuables and disposed of the bodies.

At first, Petiot dumped the bodies in the Seine

The Seine ( , ) is a river in northern France. Its drainage basin is in the Paris Basin (a geological relative lowland) covering most of northern France. It rises at Source-Seine, northwest of Dijon in northeastern France in the Langres plate ...

, but he later destroyed the bodies by submerging them in quicklime

Calcium oxide (CaO), commonly known as quicklime or burnt lime, is a widely used chemical compound. It is a white, caustic, alkaline, crystalline solid at room temperature. The broadly used term "'' lime''" connotes calcium-containing inorganic ...

or incinerating them. In 1941, Petiot bought a house at 21 Rue le Sueur, near the Arc de Triomphe

The Arc de Triomphe de l'Étoile (, , ; ) is one of the most famous monuments in Paris, France, standing at the western end of the Champs-Élysées at the centre of Place Charles de Gaulle, formerly named Place de l'Étoile—the ''étoile'' ...

. He purchased the house the same week that Henri Lafont

Henri Lafont (born Henri Chamberlin, 22 April 1902 – 26 December 1944) was a French criminal based in Paris who headed the French Gestapo during the Nazi German occupation in World War II.

He was executed by firing squad on 26 December 1944 a ...

returned to Paris with money and permission from the Abwehr

The ''Abwehr'' ( German for ''resistance'' or ''defence'', but the word usually means ''counterintelligence'' in a military context; ) was the German military-intelligence service for the '' Reichswehr'' and the ''Wehrmacht'' from 1920 to 1944. ...

to recruit new members for the French Gestapo

The Carlingue (or French Gestapo) were French auxiliaries who worked for the Gestapo, Sicherheitsdienst and Geheime Feldpolizei during the German occupation of France in the Second World War.

The group, which was based at 93 rue Lauriston in th ...

.

The Gestapo

The (), abbreviated Gestapo (; ), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of Prussia into one or ...

eventually learned about this "route" for the escape of wanted persons, which they assumed was part of the Resistance. Gestapo agent Robert Jodkum forced prisoner Yvan Dreyfus to approach the supposed network, but Dreyfus simply vanished. A later informer successfully infiltrated the operation, and the Gestapo arrested Fourrier, Pintard and Nézondet. During torture, they confessed that "Dr. Eugène" was Marcel Petiot.

Nézondet was later released, but three others spent eight months in prison, suspected of helping Jews to escape. Even during torture, they did not identify any other members of the Resistance because they knew of none. The Gestapo released the three men in January 1944.

Discovery of murders

On 11 March 1944, Petiot's neighbors in Rue Le Sueur complained to police about a foul stench in the area and large amounts of smoke billowing from a chimney of the house. Fearing a chimney fire, the police summoned firemen, who entered the house and found a great fire in a coal stove in the basement. In the fire, and scattered in the basement, were human remains. In addition to those found in his basement, human remains were also found in a pit filled partly with

In addition to those found in his basement, human remains were also found in a pit filled partly with quicklime

Calcium oxide (CaO), commonly known as quicklime or burnt lime, is a widely used chemical compound. It is a white, caustic, alkaline, crystalline solid at room temperature. The broadly used term "'' lime''" connotes calcium-containing inorganic ...

in the back yard and in a canvas bag. In his home, enough body parts were found to account for at least ten victims. Also scattered throughout his property were suitcases, clothing, and assorted property of his victims.

The media reaction was an intense media circus

Media circus is a colloquial metaphor, or idiom, describing a news event for which the level of media coverage—measured by such factors as the number of reporters at the scene and the amount of material broadcast or published—is perceived t ...

, with news reaching Switzerland, Belgium

Belgium, ; french: Belgique ; german: Belgien officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. The country is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeast, France to ...

, and Scandinavia

Scandinavia; Sámi languages: /. ( ) is a subregion in Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. In English usage, ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and Swe ...

.

Evasion and capture

During the intervening seven months, Petiot hid with friends, claiming that the Gestapo wanted him because he had killed Germans and informers. He eventually began living with a patient, Georges Redouté, let his beard grow, and adopted various aliases. During the liberation of Paris in 1944, Petiot adopted the name "Henri Valeri" and joined theFrench Forces of the Interior

The French Forces of the Interior (french: Forces françaises de l'Intérieur) were French resistance fighters in the later stages of World War II. Charles de Gaulle used it as a formal name for the resistance fighters. The change in designation ...

(FFI) in the uprising. He became a captain in charge of counterespionage and prisoner interrogations.

When the newspaper ''Resistance'' published an article about Petiot, his defense attorney from the 1942 narcotics case received a letter in which his fugitive client claimed that the published allegations were mere lies. This gave police a hint that Petiot was still in Paris. The search began anew – with "Henri Valeri" among those who were drafted to find him. Finally, on 31 October, Petiot was recognized at a Paris Métro

The Paris Métro (french: Métro de Paris ; short for Métropolitain ) is a rapid transit system in the Paris metropolitan area, France. A symbol of the city, it is known for its density within the capital's territorial limits, uniform architec ...

station, and arrested. Among his possessions were a pistol, 31,700 francs, and 50 sets of identity documents.

Trial and sentence

Petiot was imprisoned inLa Santé Prison

La Santé Prison (named after its location on the Rue de la Santé) (french: Maison d'arrêt de la Santé or ) is a prison operated by the French Prison Service of the Ministry of Justice located in the east of the Montparnasse district of the 14 ...

. He claimed that he was innocent and that he had killed only enemies of France. He said that he had discovered the pile of bodies in 21 Rue le Sueur in February 1944, but had assumed that they were collaborators killed by members of his Resistance "network".

However, the police found that Petiot had no friends in any of the major Resistance groups. Some of the Resistance groups he spoke of had never existed, and there was no proof of any of his claimed exploits. Prosecutors eventually charged him with at least 27 murders for profit. Their estimate of his gains was as much as 200 million francs.

Petiot was tried on 19 March 1946, accused of 135 criminal charges. Celebrity attorney René Floriot acted for the defense, against a team comprising state prosecutors and twelve civil lawyers hired by relatives of Petiot's victims. Petiot taunted the prosecuting lawyers, and claimed that various victims had been collaborators or double agent

In the field of counterintelligence, a double agent is an employee of a secret intelligence service for one country, whose primary purpose is to spy on a target organization of another country, but who is now spying on their own country's organ ...

s, or that vanished people were alive and well in South America using new names. He admitted to killing 19 of the 27 victims found in his house, and claimed that they were Germans and collaborators – part of a total of 63 "enemies" killed. Floriot attempted to portray Petiot as a Resistance hero, but the judges and jurors were unimpressed. Petiot was convicted of 26 counts of murder, and sentenced to death.

On 25 May 1946, Petiot was beheaded, after a stay of a few days due to a problem with the release mechanism of the guillotine

A guillotine is an apparatus designed for efficiently carrying out executions by beheading. The device consists of a tall, upright frame with a weighted and angled blade suspended at the top. The condemned person is secured with stocks at t ...

, and buried at Ivry Cemetery

Ivry Cemetery (''cimetière parisien d'Ivry'') is one of the extramural cemeteries of Paris, located in the neighbouring town of Ivry-sur-Seine in Val-de-Marne, less than 500 metres outside Paris's intramural area. As well as a green space, it is ...

.

In popular culture

Petiot's murder of Jews and his fraudulent escape network were depicted by the 1990 French movie '' Docteur Petiot'' that chronicles his life between 1941 and 1944. Petiot was portrayed by actorMichel Serrault

Michel Serrault (24 January 1928 – 29 July 2007) was a French stage and film actor who appeared from 1954 until 2007 in more than 130 films.

Life and career

His first professional job was in a touring production in Germany of Molière's '' Les ...

.

'' The Butcher of Paris'', written by Stephanie Phillips with art by Dean Kotz, is a 2019 five-issue comic book mini-series that dramatized the investigation, arrest, and eventual conviction of Petiot.

See also

*Carlingue

The Carlingue (or French Gestapo) were French auxiliaries who worked for the Gestapo, Sicherheitsdienst and Geheime Feldpolizei during the German occupation of France in the Second World War.

The group, which was based at 93 rue Lauriston in th ...

*John Bodkin Adams

John Bodkin Adams (21 January 18994 July 1983) was an Irish-born British general practitioner, convicted fraudster, and suspected serial killer. Between 1946 and 1956, 163 of his patients died while in comas, which was deemed to be worthy of i ...

* Thomas Neill Cream

*Hawley Harvey Crippen

Hawley Harvey Crippen (September 11, 1862 – November 23, 1910), usually known as Dr. Crippen, was an American homeopath, ear and eye specialist and medicine dispenser. He was hanged in Pentonville Prison in London for the murder of his wife Co ...

*H. H. Holmes

Herman Webster Mudgett (May 16, 1861 – May 7, 1896), better known as Dr. Henry Howard Holmes or H. H. Holmes, was an American con artist and serial killer, the subject of more than 50 lawsuits in Chicago alone. Until his execution in 1896, he ...

*William Palmer (murderer)

William Palmer (6 August 1824 – 14 June 1856), also known as the Rugeley Poisoner or the Prince of Poisoners, was an English doctor found guilty of murder in one of the most notorious cases of the 19th century. Charles Dickens called Palmer "t ...

* Maxim Petrov

*Harold Shipman

Harold Frederick Shipman (14 January 1946 – 13 January 2004), known by the public as Doctor Death and to acquaintances as Fred Shipman, was an English general practitioner and serial killer. He is considered to be one of the most prolif ...

*Michael Swango

Michael Joseph Swango (born October 21, 1954) is an American serial killer and licensed physician who is estimated to have been involved in as many as 60 fatal poisonings of patients and colleagues, although he admitted to only causing four deat ...

*List of serial killers by number of victims

A serial killer is typically a person who murders three or more people, in two or more separate events over a period of time, for primarily psychological reasons.A serial killer is most commonly defined as a person who kills three or more peop ...

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * Tomlins Marilyn Z. (2013) ''Die in Paris'', Raven Crest Books, London: * Jourdan Edouard (2017) ''Devil's Score: A tale of decadent omen'', Amazon PublishingExternal links

* *Tomlins, Marilyn Z"Dr. Petiot Will See You Now"

in ''Crime'' magazine {{DEFAULTSORT:Petiot, Marcel 1897 births 1946 deaths 20th-century French criminals Burials at Ivry Cemetery Executed French people Executed French serial killers Antisemitic attacks and incidents in Europe Executed people from Burgundy French male criminals French military personnel of World War I French murderers of children French people convicted of murder French people convicted of tax crimes French people of World War II French politicians Male serial killers Medical practitioners convicted of murdering their patients Medical serial killers People convicted of murder by France People executed by France by decapitation People executed by guillotine People executed by the Provisional Government of the French Republic People from Auxerre Poisoners