Manning Johnson on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

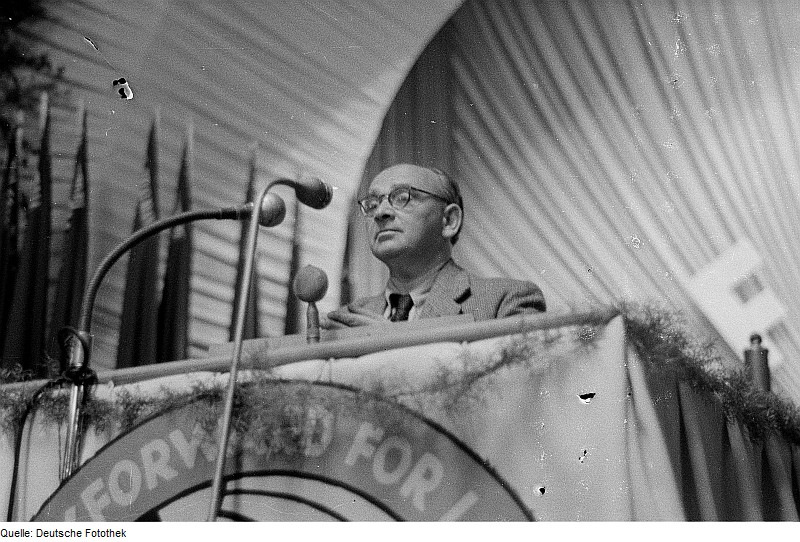

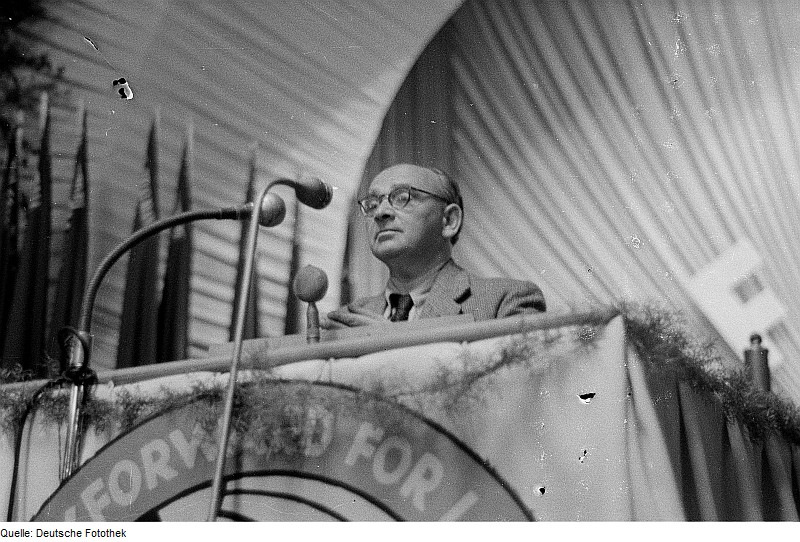

Manning Rudolph Johnson (December 17, 1908 – July 2, 1959)

was a

From 1930 to 1939, Manning Johnson was a member of the

From 1930 to 1939, Manning Johnson was a member of the

After leaving the Communist Party, Johnson said, he found Communists constantly trying to keep him out of the (non-communist) labor movement.

During

After leaving the Communist Party, Johnson said, he found Communists constantly trying to keep him out of the (non-communist) labor movement.

During  Johnson also testified against

Johnson also testified against  In December 1949 during the perjury trial of labor union leader

In December 1949 during the perjury trial of labor union leader

While testifying for Congress, Johnson spoke positively about the

While testifying for Congress, Johnson spoke positively about the

In a December 26, 1949, a ''

In a December 26, 1949, a ''

''Color, Communism, and Common Sense''

(1958) Johnson's book, ''Color, Communism, and Common Sense'', was quoted by G. Edward Griffin in his 1969 motion picture lecture ''More Deadly than War ... the Communist Revolution in America''. Archibald Roosevelt, a son of US President

ManningJohnson.org

MP3 of Johnson's Farewell Address

Johnson testimony to Canwell Committee

{{DEFAULTSORT:Johnson, Manning African-American non-fiction writers Activists for African-American civil rights American communists American political writers American male non-fiction writers American anti-racism activists 1964 deaths 1908 births Communist Party USA politicians American anti-communists Black conservatism in the United States

Communist Party USA

The Communist Party USA (CPUSA), officially the Communist Party of the United States of America, also referred to as the American Communist Party mainly during the 20th century, is a communist party in the United States. It was established ...

African-American leader and the party's candidate for U.S. Representative from New York's 22nd congressional district during a special election in 1935. Later, he left the Party and became an anti-communist government informant and witness.

Background

Manning Rudolph Johnson was born on December 17, 1908, in Washington, DC. He attended Lovejoy Elementary School, Lovejoy Junior High School, and the Armstrong Technical High School (now Friendship Armstrong Academy). He graduated from the Naval Air Technical School (at Naval Support Activity Mid-South, then inMemphis, Tennessee

Memphis is a city in Shelby County, Tennessee, United States, and its county seat. Situated along the Mississippi River, it had a population of 633,104 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, making it the List of municipalities in Tenne ...

, now at Naval Air Station Pensacola

Naval Air Station Pensacola or NAS Pensacola (formerly NAS/KNAS until changed circa 1970 to allow Nassau International Airport, now Lynden Pindling International Airport, to have IATA code NAS), "The Cradle of Naval Aviation", is a United Sta ...

).

In 1932, he studied for three months by J. Peters, William Z. Foster, Jack Stachel, Alexander Bittelman, Max Bedacht, Israel Amter, Gil Green, Harry Haywood, and James S. Allen among others at the "National Training School," part of the New (York

York is a cathedral city in North Yorkshire, England, with Roman Britain, Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers River Ouse, Yorkshire, Ouse and River Foss, Foss. It has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a Yor ...

?) Workers School, a "secret school" devoted to training "development of professional revolutionists, professional revolutionaries, or active functionaries of the Communist party."

Tuition was free with expenses paid and accommodations provided at the "Cooperative Colony" (Allerton Avenue, the Bronx) (now known as the United Workers Cooperatives). Jacob Golos of World Tourists provided transportation via the "Martell Bus Line."

Career

Communist

From 1930 to 1939, Manning Johnson was a member of the

From 1930 to 1939, Manning Johnson was a member of the Communist Party USA

The Communist Party USA (CPUSA), officially the Communist Party of the United States of America, also referred to as the American Communist Party mainly during the 20th century, is a communist party in the United States. It was established ...

; he left shortly after the announcement of the Hitler-Stalin Pact. He served as a national organizer for the Trade Union Unity League

The Trade Union Unity League (TUUL) was an industrial union umbrella organization under the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA) between 1929 and 1935. The group was an American affiliate of the Red International of Labor Unions. The fo ...

. From 1931 to 1932, he served as a District agitation propaganda director for Buffalo, New York

Buffalo is a Administrative divisions of New York (state), city in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York and county seat of Erie County, New York, Erie County. It lies in Western New York at the eastern end of Lake Erie, at the head of ...

. From 1932 to 1934, he was district organizer for Buffalo. In 1935, Manning Johnson ran as a Communist Party candidate for New York's 22nd Congressional District for the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is a chamber of the Bicameralism, bicameral United States Congress; it is the lower house, with the U.S. Senate being the upper house. Together, the House and Senate have the authority under Artic ...

. From 1936 to 1939, he served on the Party's National Committee, National Trade Union Commission, and Negro Commission.

Fellow members of the Party's national Negro Commission were: James S. Allen, Elizabeth Lawson, Robert Minor, and George Blake Charney. Johnson knew Steve Nelson "very well." From 1930 "until the American party, on the surface, severed" ties, the CPUSA followed the Communist International

The Communist International, abbreviated as Comintern and also known as the Third International, was a political international which existed from 1919 to 1943 and advocated world communism. Emerging from the collapse of the Second Internationa ...

("Comintern").

Johnson claimed later to have left the Communist Party because of his original religiosity, his disagreement with the Party's promotion of a Soviet Negro Republic in the Black Belt in the American South

The Black Belt in the American South refers to the social history, especially concerning slavery and black workers, of the geological region known as the Black Belt. The geology emphasizes the highly fertile black soil. Historically, the bla ...

, and the insincerity of the Party in saving the Scottsboro Boys. The final straw was the Hitler-Stalin Pact of 1939.

Anti-Communist

After leaving the Communist Party, Johnson said, he found Communists constantly trying to keep him out of the (non-communist) labor movement.

During

After leaving the Communist Party, Johnson said, he found Communists constantly trying to keep him out of the (non-communist) labor movement.

During World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, Johnson served in the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

.

By his own estimation in 1950, Johnson testified in 18-20 cases as a witness for the government.

In 1947, Johnson served for the first time as a government witness, this time in a case against Gerhart Eisler.

In 1948, Johnson and George Hewitt testified before the Canwell Committee in the State of Washington

Washington, officially the State of Washington, is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. It is often referred to as Washington State to distinguish it from the national capital, both named after George Washington ...

that University of Washington

The University of Washington (UW and informally U-Dub or U Dub) is a public research university in Seattle, Washington, United States. Founded in 1861, the University of Washington is one of the oldest universities on the West Coast of the Uni ...

professor Melvin Rader had been a communist.

As of 1949, Johnson was worked as an "international representative" of the Retail Clerks' International Association ( Retail Clerks International Union), which he claimed was the eighth largest union member with the American Federation of Labor

The American Federation of Labor (A.F. of L.) was a national federation of labor unions in the United States that continues today as the AFL-CIO. It was founded in Columbus, Ohio, in 1886 by an alliance of craft unions eager to provide mutual ...

thanks to a membership of 250,000.

On July 14, 1949, Johnson testified on "Communist Infiltration of Minority Groups":

Johnson also testified against

Johnson also testified against Paul Robeson

Paul Leroy Robeson ( ; April 9, 1898 – January 23, 1976) was an American bass-baritone concert artist, actor, professional American football, football player, and activist who became famous both for his cultural accomplishments and for h ...

accusing him of having been a member of the Communist Party, although Johnson said "in the Negro commission of the national committee of the Communist Party we were told, under threat of expulsion never to reveal that Paul Robeson was a member of the Communist Party, because Paul Robeson's assignment was highly confidential and secret." During 1949 testimony, Johnson summed up Robeson's career by saying, "It is regrettable, indeed, that such a man has sold himself to Moscow. He has enjoyed many of the benefits of this country.

In December 1949 during the perjury trial of labor union leader

In December 1949 during the perjury trial of labor union leader Harry Bridges

Harry Bridges (28 July 1901 – 30 March 1990) was an Australian-born American union leader, first with the International Longshoremen's Association (ILA). In 1937, he led several Pacific Coast chapters of the ILA to form a new union, the In ...

, Johnson was a government witness. ''TIME

Time is the continuous progression of existence that occurs in an apparently irreversible process, irreversible succession from the past, through the present, and into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequ ...

'' magazine reported his testimony. In 1936, Johnson had taken part in the Party's National Committee re-election of Bridges under the alias "Rossi." When James M. MacInnis, defense attorney, confirmed that Johnson had not seen him since then, Johnson explained, "The reason I didn't see him again was because, at the national committee meeting at which Harry Bridges was introduced... Jack Stachel said to the meeting that in the future Harry Bridges would not be brought to committee meetings for security reasons." Johnson's testimony hurt Bridges defense from 1945 naturalization proceedings, when he denied Communist Party membership.

In 1950, Johnson testified against the International Workers Order.

In 1953, Johnson testified before the Committee on Un-American Activities of the U.S. House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is a chamber of the bicameral United States Congress; it is the lower house, with the U.S. Senate being the upper house. Together, the House and Senate have the authority under Article One of th ...

, 83rd Congress. Robert L. Kunzig, chief counsel for the committee, asked "Was deceit a major policy of Communist propaganda and activity?" Manning R. Johnson answered, "Yes, it was. They made fine gestures and honeyed words to the church people which could be well likened unto the song of the fabled sea nymphs luring millions to moral decay, spiritual death, and spiritual slavery...".

In May 1954, Johnson testified against Ralph Bunche

Ralph Johnson Bunche ( ; August 7, 1904 – December 9, 1971) was an American political scientist, diplomat, and leading actor in the mid-20th-century decolonization process and US civil rights movement, who received the 1950 Nobel Peace Priz ...

before the International Organizations' Employees Loyalty Board, as did Leonard Patterson.

In a July 1954 article entitled "The Profession of Perjury," Professor Melvin Rader attacked Johnson's credibility: Johnson's entire testimony was false; the facts were told by Edwin O, Guthman of the ''Seattle Times ''The Seattle Times'' is an American daily newspaper based in Seattle, Washington. Founded in 1891, ''The Seattle Times'' has the largest circulation of any newspaper in the state of Washington and the Pacific Northwest region. The Seattle Time ...'' in articles which won the Pulitzer prize for the best national reporting of 1949, and by Vern Countryman, Professor of Law atYale University Yale University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701, Yale is the List of Colonial Colleges, third-oldest institution of higher education in the United Stat ...in ''Un-American Activities in the State of Washington'', Cornell University Press, 1951... Even though the facts that prove Johnson a perjurer have been widely publicized, he has continued his career as a consultant and professional witness in the employ of the Justice Department.

Attacks on NAACP

National Association for the Advancement of Colored People

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) is an American civil rights organization formed in 1909 as an interracial endeavor to advance justice for African Americans by a group including W. E. B. Du&nbs ...

(NAACP). In July 1949, for example, he said, "The record of NAACP has been remarkably fine." (During the same set of hearings, HUAC investigator Alvin Williams Stokes said, "I think it is something that should go on record. I

think this is a proper point to state that were it not for the NAACP, which has fought and is still fighting to legally correct injustices, the Urban League, to which much credit must be given for the continuing accelerated integration of Negroes in the industrial and business life of the Nation, and the many city commissions on human relations and unity, together with hundreds of Protestants, Catholics, and Jewish ministerial and interracial councils, what success communism may have obtained among Negroes must be left to speculation.")

In his last years, however, Johnson spoke negatively about the NAACP. During an undated recorded speech known as "Manning Johnson's Farewell Address," he stated: The NAACP collects millions of dollars through racial incitement. They go out of their way to create race issues, because the more race issues they create the more they have got an appeal for begging for funds, but what do they do with that money. What do they do with it?An issue which he attacked in that speech was NAACP support for

racial integration

Racial integration, or simply integration, includes desegregation (the process of ending systematic racial segregation), leveling barriers to association, creating equal opportunity regardless of Race (classification of human beings), race, and t ...

. He said, "This integration stuff has gone to all sorts of extremes." For instance, he said "Now the NAACP has gotten a token number of Negroes integrated in schools... a Pyrrhic victory

A Pyrrhic victory ( ) is a victory that inflicts such a devastating toll on the victor that it is tantamount to defeat. Such a victory negates any true sense of achievement or damages long-term progress.

The phrase originates from a quote from ...

" and that the "Supreme Court

In most legal jurisdictions, a supreme court, also known as a court of last resort, apex court, high (or final) court of appeal, and court of final appeal, is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

, in its decision, upset the question of separate but equal, educational facilities," thus attacking the 1954 ''Brown v. Board of Education

''Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka'', 347 U.S. 483 (1954), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court that ruled that U.S. state laws establishing racial segregation in public schools are unconstitutional, even if the ...

'' decision. Johnson noted, "What is significant, that this whole integration campaign coincided with Russia’s stepped-up campaign in Africa and Asia," implying some Communist influence. Johnson clearly was concerned with racial equality

Racial equality is when people of all Race (human categorization), races and Ethnic group, ethnicities are treated in an egalitarian/equal manner. Racial equality occurs when institutions give individuals legal, moral, and Civil and political r ...

in this same issue. He was concerned: The Supreme Court, by its decision, has relieved the South of all its responsibility to equalize educational facilities in the South. The Supreme Court doesn't make appropriations. It doesn't. And if the legislators in the Southern States don’t make the appropriations to equalize schools the Supreme Court's not going to do it, and you can't force them to do it. And the result is that they have relieved the South of any responsibility to equalize the education for Negroes.Clearly, Johnson felt ''Brown v. Board of Education'' was a mistake:

What the Supreme Court did was open the Pandora box. They have created the fertile soil for the operation of the worst type of elements on both sides. And as a result of this, race relations have been set back 50 years in this country.Referring again and again to "Red" or "Russian" support for the African nationalist movement, Johnson seems to have drawn on his US experience in promoting a Negro Soviet Republic in the Black Belt with the African nationalist movement two decades later. Like many ex-Communists, he continued to see Communist influence, as he directly stated: "Beneath all of the racial unrest, at the root of all racial unrest in the country, is the clammy, cold, bloody hand of Communism."

Personal life and death

In a December 26, 1949, a ''

In a December 26, 1949, a ''Time

Time is the continuous progression of existence that occurs in an apparently irreversible process, irreversible succession from the past, through the present, and into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequ ...

'' magazine article entitled "You'd Be Thin, Too" described him as a "husky, big-jawed... smooth, deep-voiced Negro."

During the late 1930s, Johnson was a member of the American League Against War and Fascism.

Johnson wrote of poet Claude McKay

Festus Claudius "Claude" McKay OJ (September 15, 1890See Wayne F. Cooper, ''Claude McKay, Rebel Sojourner In The Harlem Renaissance'' (New York, Schocken, 1987) p. 377 n. 19. As Cooper's authoritative biography explains, McKay's family predate ...

that "I knew imvery well."

Manning Johnson died following an auto accident which had occurred on June 26, 1959 just south of Lake Arrowhead Village, California

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

. He is buried at Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery

Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery is a federal United States National Cemetery System, military cemetery in San Diego, California. It is located on the grounds of the former Army coastal artillery station Naval Base Point Loma, Fort Rosecrans a ...

in San Diego, California

San Diego ( , ) is a city on the Pacific coast of Southern California, adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a population of over 1.4 million, it is the List of United States cities by population, eighth-most populous city in t ...

.

Legacy

During the July 1949 hearing into Communist infiltration of minority groups, Manning told HUAC of his interactions with HUAC investigator Alvin Williams Stokes. He said that Stokes "talked to us in New York about 2 years ago and convinced me I should take part before this committee." Johnson also stated (without prompting from the committee):The information that you have gotten from me today was not prepared before I came here. Mr. Stokes spoke to me about a couple years ago in New York, and met with me again several months ago, and I discussed with him some of the things which I have put in the record. They are more or less familiar to me. To answer some of the questions you ask thoroughly and as they should be answered would necessitate my refreshing my recollection and checking on certain records and so forth which I have. I will be glad to come at any future time to assist you in establishing the facts as to Communist activities in this republic.In 1966, W. Cleon Skousen called Johnson "the most important Negro Communist in the United States." In 1981, Victor S. Navasky (then, publisher of ''

The Nation

''The Nation'' is a progressive American monthly magazine that covers political and cultural news, opinion, and analysis. It was founded on July 6, 1865, as a successor to William Lloyd Garrison's '' The Liberator'', an abolitionist newspaper ...

'' magazine and who refers to Johnson only with the epithet "informant") documented Manning Johnson's 1951 admission to lying in 1949 during the second trial of Harry Bridges: Works

Writings of Johnson include: * "Party Organizer" (1933) * "An American Holiday" (1939)''Color, Communism, and Common Sense''

(1958) Johnson's book, ''Color, Communism, and Common Sense'', was quoted by G. Edward Griffin in his 1969 motion picture lecture ''More Deadly than War ... the Communist Revolution in America''. Archibald Roosevelt, a son of US President

Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

, wrote the book's preface as president of The Alliance, Inc.

In describing his Communist experience, he claimed that the CPUSA was under the control of the Soviet Politburo

A politburo () or political bureau is the highest organ of the central committee in communist parties. The term is also sometimes used to refer to similar organs in socialist and Islamist parties, such as the UK Labour Party's NEC or the Poli ...

, of which he claimed to be a member, and that Gerhart Eisler (named in 1946 by Louis F. Budenz as head of Soviet espionage in the USA) was the Soviet's country representative. The book's table of contents lists:

: Preface by Archibald B. Roosevelt

: I. In the Web

: II. Subverting Negro Churches

: III. Red Plot to Use Negroes

: IV. Bane of Red Integration

: V. Destroying the Opposition

: VI. The Real “Uncle Toms”

: VII. Creating Hate

: VIII. Modern Day Carpet Baggers

: IX. Race Pride is Passé

: X. Wisdom Needed

: Appendices

Johnson claimed that the Communist Party controlled the unions including American Negro Labor Congress, League of Struggle for Negro Rights, International Labor Defense

The International Labor Defense (ILD) (1925–1947) was a legal advocacy organization established in 1925 in the United States as the American section of the Comintern's International Red Aid network. The ILD defended Sacco and Vanzetti, was active ...

, National Negro Congress

In African-American history, the National Negro Congress (NNC; 1936–ca. 1946) was an African-American organization formed in 1936 at Howard University as a broadly based coalition organization with the goal of fighting for Black liberation; it ...

, Sharecroppers' Union, Civil Rights Congress

The Civil Rights Congress (CRC) was a United States civil rights organization, formed in 1946 at a national conference for radicals and disbanded in 1956. It succeeded the International Labor Defense, the National Federation for Constitutional L ...

, Negro Labor Victory Committee, Southern Negro Youth Congress, and Negro Labor Councils. (NOTE: International Labor Defense

The International Labor Defense (ILD) (1925–1947) was a legal advocacy organization established in 1925 in the United States as the American section of the Comintern's International Red Aid network. The ILD defended Sacco and Vanzetti, was active ...

was not a union but a legal defense group.) In the book's appendix, Johnson attacked Howard University

Howard University is a private, historically black, federally chartered research university in Washington, D.C., United States. It is classified among "R1: Doctoral Universities – Very high research activity" and accredited by the Mid ...

.

See also

*Communist Party USA

The Communist Party USA (CPUSA), officially the Communist Party of the United States of America, also referred to as the American Communist Party mainly during the 20th century, is a communist party in the United States. It was established ...

* Anti-Communism

Anti-communism is Political movement, political and Ideology, ideological opposition to communism, communist beliefs, groups, and individuals. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in Russia, and it reached global ...

* Harry Bridges

Harry Bridges (28 July 1901 – 30 March 1990) was an Australian-born American union leader, first with the International Longshoremen's Association (ILA). In 1937, he led several Pacific Coast chapters of the ILA to form a new union, the In ...

* Paul Robeson

Paul Leroy Robeson ( ; April 9, 1898 – January 23, 1976) was an American bass-baritone concert artist, actor, professional American football, football player, and activist who became famous both for his cultural accomplishments and for h ...

References

External links

ManningJohnson.org

MP3 of Johnson's Farewell Address

Johnson testimony to Canwell Committee

{{DEFAULTSORT:Johnson, Manning African-American non-fiction writers Activists for African-American civil rights American communists American political writers American male non-fiction writers American anti-racism activists 1964 deaths 1908 births Communist Party USA politicians American anti-communists Black conservatism in the United States