The Man in the Iron Mask (; died 19 November 1703) was an unidentified

prisoner of state during the reign of

Louis XIV

LouisXIV (Louis-Dieudonné; 5 September 16381 September 1715), also known as Louis the Great () or the Sun King (), was King of France from 1643 until his death in 1715. His verified reign of 72 years and 110 days is the List of longest-reign ...

of France (1643–1715). The strict measures taken to keep his imprisonment secret resulted in a long-lasting legend about his identity. Warranted for arrest on 19 July 1669 under the name of "Eustache Dauger", he was apprehended near

Calais

Calais ( , , traditionally , ) is a French port city in the Pas-de-Calais department, of which it is a subprefecture. Calais is the largest city in Pas-de-Calais. The population of the city proper is 67,544; that of the urban area is 144,6 ...

on 28 July, incarcerated on 24 August, and held for 34 years in the custody of the same jailer, , in four successive French prisons, including the

Bastille

The Bastille (, ) was a fortress in Paris, known as the Bastille Saint-Antoine. It played an important role in the internal conflicts of France and for most of its history was used as a state prison by the kings of France. It was stormed by a ...

. When he died there on 19 November 1703, his

inhumation

Burial, also known as interment or inhumation, is a method of final disposition whereby a dead body is placed into the ground, sometimes with objects. This is usually accomplished by excavating a pit or trench, placing the deceased and object ...

certificate bore the name of "Marchioly", leading several historians to conclude the prisoner was Italian diplomat

Ercole Antonio Mattioli.

His true identity remains a mystery, even though it has been extensively debated by historians, and various theories have been expounded in numerous books, articles, poems, plays, and films. During his lifetime, it was rumoured that he was a

Marshal of France

Marshal of France (, plural ') is a French military distinction, rather than a military rank, that is awarded to General officer, generals for exceptional achievements. The title has been awarded since 1185, though briefly abolished (1793–1804) ...

or a President of ''

Parlement

Under the French Ancien Régime, a ''parlement'' () was a provincial appellate court of the Kingdom of France. In 1789, France had 13 ''parlements'', the original and most important of which was the ''Parlement'' of Paris. Though both th ...

''; the

Duke of Beaufort

Duke of Beaufort ( ) is a title in the Peerage of England. It was created by Charles II in 1682 for Henry Somerset, 3rd Marquess of Worcester, a descendant of Charles Somerset, 1st Earl of Worcester, legitimised son of Henry Beaufort, 3rd D ...

, or a son of

Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English statesman, politician and soldier, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in British history. He came to prominence during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, initially ...

, and some of these rumours were initiated by Saint-Mars himself. Among the oldest theories is one proposed by French philosopher and writer

Voltaire

François-Marie Arouet (; 21 November 169430 May 1778), known by his ''Pen name, nom de plume'' Voltaire (, ; ), was a French Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment writer, philosopher (''philosophe''), satirist, and historian. Famous for his wit ...

, who claimed in his (1771) that the prisoner was an older, illegitimate brother of Louis XIV. Other writers similarly believed he was the King's twin or younger brother. In all, more than 50 candidates, real and hypothetical, have been proposed by historians and other authors aiming to solve the mystery.

What little is known about the prisoner is based on contemporary documents uncovered during the 19th century, mainly some of the correspondence between and his superiors in Paris, initially

Louvois, Louis XIV's secretary of state for war. These documents show that the prisoner was labelled "only a valet" and that he was jailed for "what he was employed to do" before his arrest. Legend has it that no one ever saw his face, as it was hidden by a mask of black velvet cloth, later misreported by Voltaire as an iron mask. Official documents reveal, however, that the prisoner was made to cover his face only when travelling between prisons after 1687, or when going to prayers within the Bastille in the final years of his incarceration; modern historians believe the latter measure was imposed by Saint-Mars solely to increase his own prestige, thus causing persistent rumours to circulate about this seemingly important prisoner.

In 1932, French historian Maurice Duvivier proposed that the prisoner was

Eustache Dauger de Cavoye, a nobleman associated with several political scandals of the late 17th century. This solution, however, was disproved in 1953 when previously unpublished family letters were discovered by another French historian,

Georges Mongrédien, who concluded that the enigma remained unsolved owing to the lack of reliable historical documents about the prisoner's identity and the cause of his long incarceration.

He has been the subject of many works of fiction, most prominently in 1850 by

Alexandre Dumas

Alexandre Dumas (born Alexandre Dumas Davy de la Pailleterie, 24 July 1802 – 5 December 1870), also known as Alexandre Dumas , was a French novelist and playwright.

His works have been translated into many languages and he is one of the mos ...

. A section of his novel ''

The Vicomte of Bragelonne: Ten Years Later''—the final installment of his

D'Artagnan saga—features this prisoner, portrayed as Louis XIV's identical twin and forced to wear an iron mask. In 1840, Dumas had first presented a review of the popular theories about the prisoner extant in his time in the chapter "", published in the eighth volume of his non-fiction . This approach was adopted by many subsequent authors, and speculative works have continued to appear on the subject.

Prisoner

Arrest and imprisonment

The earliest surviving records of the masked prisoner are from 19 July 1669, when

Louis XIV

LouisXIV (Louis-Dieudonné; 5 September 16381 September 1715), also known as Louis the Great () or the Sun King (), was King of France from 1643 until his death in 1715. His verified reign of 72 years and 110 days is the List of longest-reign ...

's minister, the

Marquis de Louvois, sent a letter to

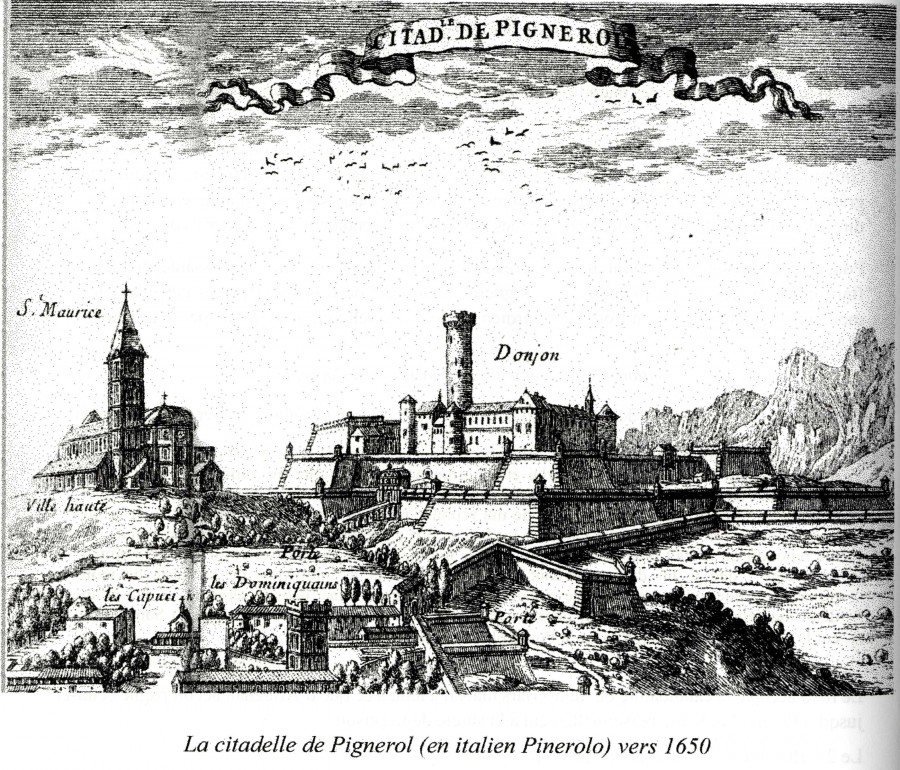

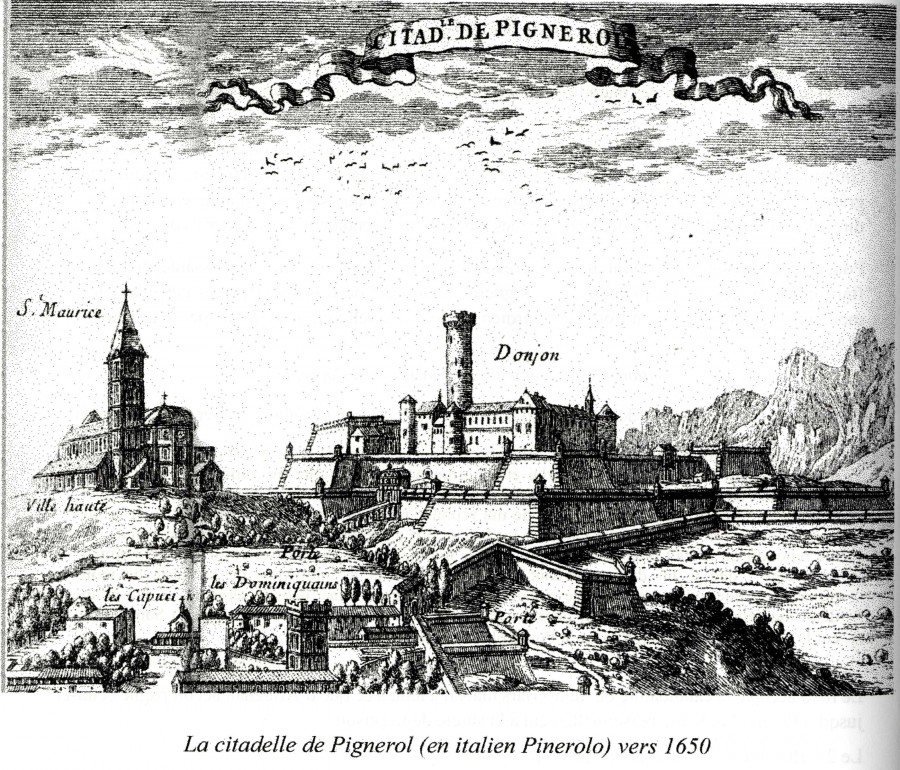

Bénigne Dauvergne de Saint-Mars, governor of the prison of

Pignerol (which at the time was part of France). In his letter, Louvois informed Saint-Mars that a prisoner named "Eustache Dauger" was due to arrive in the next month or so.

He instructed Saint-Mars to prepare a cell with multiple doors, one closing upon the other, which were to prevent anyone from the outside listening in. Saint-Mars was to see Dauger only once a day to provide food and whatever else he needed. Dauger was to be told that if he ever spoke of anything other than his immediate needs he would be killed, but, according to Louvois, the prisoner should not require much since he was "only a valet". Historians have noted that the name "Eustache Dauger" was written in a handwriting different from that used in the rest of the letter's text, suggesting that a clerk wrote the letter under Louvois' dictation, while someone else, very likely Louvois, added the name afterward.

Dauger was arrested by Captain Alexandre de Vauroy, garrison commander of

Dunkerque

Dunkirk ( ; ; ; Picard language, Picard: ''Dunkèke''; ; or ) is a major port city in the Departments of France, department of Nord (French department), Nord in northern France. It lies from the Belgium, Belgian border. It has the third-larg ...

, on 28 July and taken to Pignerol, where he arrived on 24 August. Evidence has been produced to suggest that the arrest was actually made in

Calais

Calais ( , , traditionally , ) is a French port city in the Pas-de-Calais department, of which it is a subprefecture. Calais is the largest city in Pas-de-Calais. The population of the city proper is 67,544; that of the urban area is 144,6 ...

and that not even the local governor was informed of the event—Vauroy's absence being explained away by his hunting for Spanish soldiers who had strayed into France via the

Spanish Netherlands

The Spanish Netherlands (; ; ; ) (historically in Spanish: , the name "Flanders" was used as a '' pars pro toto'') was the Habsburg Netherlands ruled by the Spanish branch of the Habsburgs from 1556 to 1714. They were a collection of States of t ...

. The first rumours of the prisoner's identity (specifically as a

Marshal of France

Marshal of France (, plural ') is a French military distinction, rather than a military rank, that is awarded to General officer, generals for exceptional achievements. The title has been awarded since 1185, though briefly abolished (1793–1804) ...

) began to circulate at this point.

Dauger serves as a valet

The prison at Pignerol, like the others at which Dauger was later held, was used for men who were considered an embarrassment to the state and usually held only a handful of prisoners at a time. Saint-Mars's other prisoners at Pignerol included Count

Ercole Antonio Mattioli, an Italian diplomat who had been kidnapped and jailed for double-crossing the French over the purchase of the important fortress town of

Casale on the

Mantuan border. There was

Nicolas Fouquet

Nicolas Fouquet, marquis de Belle-Île, vicomte de Melun et Vaux (; 27 January 1615 – 23 March 1680) was the Superintendent of Finances in France from 1653 until 1661 under King Louis XIV. He had a glittering career, and acquired enormous weal ...

, Marquis of Belle-Île, a former superintendent of finances who had been jailed by Louis XIV on the charge of embezzlement, and the

Marquis de Lauzun, who had become engaged to the

Duchess of Montpensier

Countess of Montpensier

House of Valois, 1362?–1434

House of Bourbon-Montpensier, 1434–1523

Duchess of Montpensier

House of Bourbon-Vendôme, 1561–1627

House of Bourbon-Orléans

House of Bourbon-Orléans (in pretence) ...

, a cousin of the king, without the king's consent. Fouquet's cell was above that of Lauzun. In his letters to Louvois, Saint-Mars describes Dauger as a quiet man, giving no trouble, "disposed to the will of God and to the king", compared to his other prisoners, who were always complaining, constantly trying to escape, or simply mad.

Dauger was not always isolated from the other prisoners. Wealthy and important ones usually had manservants; Fouquet, for instance, was served by a man called La Rivière. These servants, however, would become as much prisoners as their masters and it was thus difficult to find people willing to volunteer for such an occupation. Because La Rivière was often ill, Saint-Mars applied for permission for Dauger to act as servant for Fouquet. In 1675, Louvois gave permission for such an arrangement on condition that he was to serve Fouquet only while La Rivière was unavailable and that he was not to meet anyone else; for instance, if Fouquet and Lauzun were to meet, Dauger was not to be present. Fouquet was never expected to be released; thus, meeting Dauger was no great matter, but Lauzun was expected to be set free eventually, and it would have been important not to have him spread rumours of Dauger's existence or of secrets he might have known. The important fact that Dauger served as a valet to Fouquet strongly indicates he was born a

commoner

A commoner, also known as the ''common man'', ''commoners'', the ''common people'' or the ''masses'', was in earlier use an ordinary person in a community or nation who did not have any significant social status, especially a member of neither ...

.

On 23 November 1678, Louvois wrote directly to Fouquet to inform him that the King was disposed to soften considerably the strictures of his incarceration, subject to Fouquet writing back to Louvois—without informing Saint-Mars of the contents of his reply—concerning whether or not Dauger had talked to him, Fouquet, in front of La Rivière, "about what he was employed to do before being brought to Pignerol". From this revealing letter, French historian Mongrédien concluded that Louvois was clearly anxious that any details about Dauger's former employment should not leak out if the King decided to relax the conditions of Fouquet's or Lauzun's incarceration.

After Fouquet's death on 23 March 1680, Saint-Mars discovered a secret hole between Fouquet and Lauzun's cells. He was sure that they had communicated through this hole without detection by him or his guards and thus that Lauzun must have been made aware of Dauger's existence. On 8 April 1680, Louvois therefore wrote to Saint-Mars and instructed him to move Lauzun to Fouquet's cell and to tell him that Dauger and La Rivière had been released, after secretly relocating them to a new cell in the lower tower of Pignerol's dungeon. They became henceforth identified in official correspondence only as "the two gentlemen of the lower tower" ("les messieurs de la tour d'en bas"). After La Rivière died in early 1687, Dauger continued to be referred to as "La Tour" by prison staff and as the "old prisoner" ("l'ancien prisonnier") in correspondence.

Dauger's subsequent prisons

Lauzun was freed on 22 April 1681. Two months later, Saint-Mars was appointed governor of the prison of the

Exiles Fort (now

Exilles

Exilles (Occitan: ''Eissilhas''; nonstandard Occitan: ''Isiya''; Piedmontese: ''Isiles''; Latin: ''Excingomagus'' or ''Scingomagus''; Italianization under Italian Fascism: ''Esille'') is a municipality in the Metropolitan City of Turin in the Itali ...

in Italy); he went there in September 1681, taking Dauger and La Rivière with him. La Rivière's death was reported in January 1687; in May of that year, Saint-Mars and Dauger moved to

Sainte-Marguerite, one of the

Lérins Islands, half a mile offshore from Cannes. It was during the journey to Sainte-Marguerite that rumours spread that the prisoner was wearing an iron mask. Again, he was placed in a cell with multiple doors.

On 18 September 1698, Saint-Mars took up his new post as governor of the

Bastille

The Bastille (, ) was a fortress in Paris, known as the Bastille Saint-Antoine. It played an important role in the internal conflicts of France and for most of its history was used as a state prison by the kings of France. It was stormed by a ...

prison in Paris, bringing Dauger with him. He was placed in a solitary cell in the prefurnished third chamber of the Bertaudière tower. The prison's second-in-command, de Rosarges, was to feed him. Lieutenant du Junca, another officer of the Bastille, noted that the new prisoner wore "a mask of black velvet". Dauger died there on 19 November 1703 and was buried the next day under the name of "Marchioly".

Candidates

In the third edition (2004) of his book on the subject, French historian Jean-Christian Petitfils collated a list of 52 candidates, real or imagined, whose names had been either mentioned as rumours in contemporary documents, or proposed in printed works, between 1669 and 1992.

Contemporary rumours

A week after Dauger's arrival at Pignerol, Saint-Mars wrote to Louvois (31 August 1669), reporting that the prisoner was rumoured to be a "

Marshall of France or President of ''

Parlement

Under the French Ancien Régime, a ''parlement'' () was a provincial appellate court of the Kingdom of France. In 1789, France had 13 ''parlements'', the original and most important of which was the ''Parlement'' of Paris. Though both th ...

''". Eight months later, Saint-Mars informed Louvois (12 April 1670) that he initiated some of these rumours himself, when asked about the prisoner: "I tell them tall tales to make fun of them."

A few months after Dauger was relocated to his new prison cell at the Île Sainte-Marguerite Fort in January 1687, Saint-Mars wrote to Louvois about the latest rumours (3 May 1687): "Everyone tries to guess who my prisoner might be." On 4 September 1687, the ''Nouvelles Écclésiastiques'' published a letter by Nicolas Fouquet's brother Louis, quoting a statement made by Saint-Mars: "All the people that one believes dead are not", a hint that the prisoner might be the

Duke of Beaufort

Duke of Beaufort ( ) is a title in the Peerage of England. It was created by Charles II in 1682 for Henry Somerset, 3rd Marquess of Worcester, a descendant of Charles Somerset, 1st Earl of Worcester, legitimised son of Henry Beaufort, 3rd D ...

. Four months later, Saint-Mars reiterated this "rumour" in writing to Louvois (8 January 1688), adding: "(...) others say that he is a son of the late

Cromwell".

English milord

On 10 October 1711, King Louis XIV's sister-in-law,

Elizabeth Charlotte, Princess Palatine, sent a letter to her aunt,

Sophia, Electress of Hanover, stating that the prisoner had "two

musketeers at his side to kill him if he removed his mask". She described him as very devout, and stated that he was well treated and received everything he desired. In another letter sent less than two weeks later, on 22 October, she added having just learnt that he was "an English milord connected with the affair of the

Duke of Berwick against

King William III

William III (William Henry; ; 4 November 1650 – 8 March 1702), also known as William of Orange, was the sovereign Prince of Orange from birth, Stadtholder of Holland, Zeeland, Utrecht, Guelders, and Overijssel in the Dutch Republic from 167 ...

." The Princess was clearly reporting rumours she had heard at court.

King's relative

Some of the most enduring theories about the prisoner's identity, outlined in the sections below, assume that he was a relative of Louis XIV, because of the importance attached to secrecy during his incarceration which, in turn, fed the legend that he must have been one of the most important persons in the realm. These theories emerged during the 1700s, long before historians were able to consult the archives revealing that the prisoner was "only a valet", imprisoned for "what he was employed to do", and for "what he knew". These early theories arose solely from their author's imagination, and boosted the romantic appeal of a sensational elucidation of the enigma. Historians such as Mongrédien (1952) and Noone (1988), however, pointed out that the solution whereby Louis XIV is supposed to have had an illegitimate brother—whether older, twin, or younger—does not provide a credible explanation, for example, on how it would have been possible for Queen

Anne of Austria

Anne of Austria (; ; born Ana María Mauricia; 22 September 1601 – 20 January 1666) was Queen of France from 1615 to 1643 by marriage to King Louis XIII. She was also Queen of Navarre until the kingdom's annexation into the French crown ...

to conceal a pregnancy throughout its full course and bear, then deliver, a child in secret. Mongrédien concluded that "historians cannot give it the slightest credence."

King's illegitimate son

In 1745, an anonymous writer published a book in Amsterdam, ''Mémoires pour servir à l'Histoire de la Perse'', romanticising life at the French Court in the form of Persian history. Members of the royal family and locations were given fictitious Persian names, and their key was published in the book's third edition (1759). In this tale, Louis XIV's illegitimate son,

Louis, Count of Vermandois

Louis de Bourbon, ''Légitimé de France'', Count of Vermandois, born Louis de La Blaume Le Blanc, also known as Louis de/of Vermandois (2 October 1667 – 18 November 1683) was a French nobleman, Illegitimacy, illegitimate but legitimised s ...

, is alleged to have struck his half-brother,

Louis, Grand Dauphin

Louis, Dauphin of France (1 November 1661 – 14 April 1711), commonly known as le Grand Dauphin, was the eldest son and heir apparent of King Louis XIV and his spouse, Maria Theresa of Spain. He became known as the Grand Dauphin after the birth ...

, causing the King to banish him to life imprisonment, first at the Île Sainte-Marguerite and later at the Bastille. He was made to wear a mask whenever he was to be seen or attended to, when sick or in other circumstances. The theory of Vermandois as the prisoner in the mask was later mentioned by

Henri Griffet, in 1769, as having circulated during the reign of Louis XIV, therefore long before 1745.

In reality, there are no historical records of gossip confirming that Vermandois ever struck the Grand Dauphin. In the memoirs of Louis XIV's first cousin, the

Duchess of Montpensier

Countess of Montpensier

House of Valois, 1362?–1434

House of Bourbon-Montpensier, 1434–1523

Duchess of Montpensier

House of Bourbon-Vendôme, 1561–1627

House of Bourbon-Orléans

House of Bourbon-Orléans (in pretence) ...

, there is mention of Vermandois having displeased the King for taking part in orgies in 1682, and being temporarily banished from court as a result. After promising to mend his way, he was sent—soon after his 16th birthday—to join the army in

Courtrai

Kortrijk ( , ; or ''Kortrik''; ), sometimes known in English as Courtrai or Courtray ( ), is a Belgian city and municipality in the Flemish province of West Flanders.

With its 80,000 inhabitants (2024) Kortrijk is the capital and largest cit ...

during the

War of the Reunions (1683–84), in early November 1683. He distinguished himself in the battle line, but died of a fever during the night of 17 November. The King was reported to be deeply affected by his son's death, and Vermandois' sister,

Marie Anne de Bourbon, was inconsolable while their mother,

Louise de La Vallière

Françoise-Louise de La Baume Le Blanc, Duchess of La Vallière and Vaujours (6 August 1644 – 6 June 1710) was a French nobility, French noblewoman and the Royal mistress, mistress of King Louis XIV of France from 1661 to 1667.

La Vallière ...

, sought solace in endless prayer at her

Carmelites

The Order of the Brothers of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Mount Carmel (; abbreviated OCarm), known as the Carmelites or sometimes by synecdoche known simply as Carmel, is a mendicant order in the Catholic Church for both men and women. Histo ...

convent

A convent is an enclosed community of monks, nuns, friars or religious sisters. Alternatively, ''convent'' means the building used by the community.

The term is particularly used in the Catholic Church, Lutheran churches, and the Anglican ...

in Paris.

King's elder brother

During his two sojourns in the Bastille in 1717–18 and 1726, Voltaire became aware of the traditions and legends circulating among the staff at the fortress. On 30 October 1738, he wrote to the

Abbé Dubos: "I am somewhat knowledgeable about the adventure of the Man in the Iron Mask, who died at the Bastille; I spoke to people who had served him." In the second edition of his (1771), Voltaire claimed that the prisoner was an illegitimate first son of Anne of Austria and an unknown father, and therefore an older half-brother of Louis XIV. This assertion was partly based on the historical fact that the birth of Louis XIV on 5 September 1638 had come as a surprise: since

Louis XIII

Louis XIII (; sometimes called the Just; 27 September 1601 – 14 May 1643) was King of France from 1610 until his death in 1643 and King of Navarre (as Louis II) from 1610 to 1620, when the crown of Navarre was merged with the French crown.

...

and Anne of Austria had been childless for 23 years, it was believed they were unable to conceive, despite evidence to the contrary of the Queen's well-known miscarriages. In fact, the royal couple had been living for years in mutual distrust and had become estranged since the mid-1620s. Furthermore, in August 1637, the Queen had been found guilty of treasonable correspondence with Spain and had been placed under house arrest at the

Louvre Palace

The Louvre Palace (, ), often referred to simply as the Louvre, is an iconic French palace located on the Right Bank of the Seine in Paris, occupying a vast expanse of land between the Tuileries Gardens and the church of Saint-Germain l'Auxe ...

. However, contemporary accounts nonetheless indicate that the royal couple shared a bed and conceived the future Louis XIV, either in early December 1637 or, as historians deem more likely, sometime during the previous month. The Queen's pregnancy was made public on 30 January 1638.

Based on the assumption that the royal couple were unable to conceive, Voltaire theorised that an earlier, secret birth of an illegitimate child persuaded the Queen that she was not infertile, in turn prompting

Cardinal Richelieu

Armand Jean du Plessis, 1st Duke of Richelieu (9 September 1585 – 4 December 1642), commonly known as Cardinal Richelieu, was a Catholic Church in France, French Catholic prelate and statesman who had an outsized influence in civil and religi ...

to arrange an outing during which the royal couple had to share a bed, which led to the birth of Louis XIV.

The theme of an imagined elder brother of Louis XIV resurfaced in 1790, when French historian Pierre-Hubert Charpentier asserted that the prisoner was an illegitimate son of Anne of Austria and

George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham

George Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham ( ; 20 August 1592 – 23 August 1628), was an English courtier, statesman, and patron of the arts. He was a favourite and self-described "lover" of King James VI and I. Buckingham remained at the heigh ...

, supposedly born in 1626, two years before the latter's death. Louis XIV was presumed to have had this elder brother imprisoned upon the Queen's death in 1666. According to Charpentier, this theory had originated with a certain Mademoiselle de Saint-Quentin, a mistress of the

Marquess of Barbezieux, son of Louvois and his successor as War Minister to Louis XIV in 1691. A few days before his sudden death on 5 January 1701, Barbezieux had told her the secret of the prisoner's identity, which she disclosed publicly to several people in

Chartres

Chartres () is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Eure-et-Loir Departments of France, department in the Centre-Val de Loire Regions of France, region in France. It is located about southwest of Paris. At the 2019 census, there were 1 ...

towards the end of her life in the mid-1700s. Charpentier also stated that Voltaire had heard this version in

Geneva

Geneva ( , ; ) ; ; . is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland and the most populous in French-speaking Romandy. Situated in the southwest of the country, where the Rhône exits Lake Geneva, it is the ca ...

, but chose to omit Buckingham's name when he began to develop his own variant of this theory in the first edition of ''

The Age of Louis XIV

''The Age of Louis XIV'' (''Le Siècle de Louis XIV'', also translated ''The Century of Louis XIV'') is a historical work by the French historian, philosopher, and writer Voltaire, first published in 1751. Through it, the French 17th century becam ...

'' (1751), finally revealed in full in (1771).

King's twin brother

Many authors supported the theory of the prisoner being a twin brother of King Louis XIV:

Michel de Cubières (1789),

Jean-Louis Soulavie (1791),

Las Cases (1816),

Victor Hugo

Victor-Marie Hugo, vicomte Hugo (; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French Romanticism, Romantic author, poet, essayist, playwright, journalist, human rights activist and politician.

His most famous works are the novels ''The Hunchbac ...

(1839), Alexandre Dumas (1840), Paul Lecointe (1847), and others.

In a 1965 essay, ''Le Masque de fer'' (revised in 1973 under the title ''

Le secret du Masque de Fer''), French novelist and playwright

Marcel Pagnol

Marcel Paul Pagnol (, also ; ; 28 February 1895 – 18 April 1974) was a French novelist, playwright, and filmmaker. Regarded as an auteur, in 1946, he became the first filmmaker elected to the . Pagnol is generally regarded as one of France's ...

, proposing his hypothesis in particular on the circumstances of Louis XIV's birth, claimed that the Man in the Iron Mask was indeed a twin brother, but born second, who would have been hidden in order to avoid any dispute over the throne holder. At the time, there was a controversy over which one of twins was the elder: the one born first, or the one born second, who was then thought to have been conceived first.

Historians who reject this hypothesis (including

Jean-Christian Petitfils) highlight the conditions of childbirth for the queen: it usually took place in the presence of multiple witnesses—the main court's figures. According to Pagnol, immediately after the birth of the future Louis XIV at 11 a.m. on 5 September 1638, Louis XIII took his whole court (about 40 people) to the

''Château de Saint-Germain'''s chapel to celebrate a ''

Te Deum

The ( or , ; from its incipit, ) is a Latin Christian hymn traditionally ascribed to a date before AD 500, but perhaps with antecedents that place it much earlier. It is central to the Ambrosian hymnal, which spread throughout the Latin ...

'' in great pomp, contrary to the common practice of celebrating it several days before childbirth. Pagnol contends that the court's removal to this ''Te Deum'' had been rushed to enable the queen to deliver the second twin in secret and attended only by the midwife.

Pagnol's solution—combining earlier theories by

Soulavie (1790),

Andrew Lang

Andrew Lang (31 March 1844 – 20 July 1912) was a Scottish poet, novelist, literary critic, and contributor to the field of anthropology. He is best known as a folkloristics, collector of folklore, folk and fairy tales. The Andrew Lang lectur ...

(1903),

Arthur Barnes (1908), and Edith Carey (1924)—speculates that this twin was born a few hours after Louis XIV and grew up on the Island of

Jersey

Jersey ( ; ), officially the Bailiwick of Jersey, is an autonomous and self-governing island territory of the British Islands. Although as a British Crown Dependency it is not a sovereign state, it has its own distinguishing civil and gov ...

under the name

James de la Cloche, believing himself to be an illegitimate son of

Charles II. During a hypothetical, secret meeting in January 1669, Charles is assumed to have recognised the twin for his resemblance to the French king and revealed to him his true identity. Shortly thereafter, the twin would supposedly have adopted the new identity of "Martin" as a valet to

Roux de Marcilly, with whom he conspired against Louis XIV, which led to his arrest in Calais in July 1669. Historically, however, the real valet Martin (distinct from Pagnol's reinterpreted "Martin") could not have become "Eustache Dauger" because he had fled to London when the Roux conspiracy failed; this is well known because his extradition from England to France had at first been requested by Foreign Minister

Hugues de Lionne on 12 June 1669, but subsequently cancelled by him on 13 July. Pagnol explained this historical fact away by claiming, without any evidence, that "Martin" must have been secretly abducted in London in early July and transported to France on 7 or 8 July, and that the extradition order had therefore been cancelled because it was no longer necessary, its objective having already been achieved.

King's younger brother

In 1791, Jean Baptiste De Saint-Mihiel proposed that the prisoner was an illegitimate younger brother of Louis XIV, fathered by

Cardinal Mazarin

Jules Mazarin (born Giulio Raimondo Mazzarino or Mazarini; 14 July 1602 – 9 March 1661), from 1641 known as Cardinal Mazarin, was an Italian Catholic prelate, diplomat and politician who served as the chief minister to the Kings of France Lou ...

. This theory was based on the fact, mentioned by Voltaire in (1771), that the prisoner had told his doctor that he "believed himself to be about 60 years old", a few days before his death in 1703. De Saint-Mihiel extrapolated that the prisoner was therefore born around 1643, and could therefore only be a younger brother to the King, born in 1638. It is a historical fact that, four days after Louis XIII's death on 14 May 1643, the Queen was declared Regent and appointed Mazarin as her chief minister and head of government that evening. Mazarin was soon believed to be her lover, and even her secret

morganatic husband. The theory of the prisoner being an imagined, younger son of the Queen and Mazarin was rekindled in 1868 by Charles-Henri, baron de Gleichen.

King's father

In 1955, Hugh Ross Williamson argued that the Man in the Iron Mask was the natural father of Louis XIV. According to this theory, the "miraculous" birth of Louis XIV in 1638 would have come after Louis XIII had been estranged from his wife Anne of Austria for 14 years.

The theory then suggests that Cardinal Richelieu had arranged for a substitute, probably an illegitimate grandson of

Henry IV, to become intimate with the queen and father an heir in the king's stead. At the time, the

heir presumptive

An heir presumptive is the person entitled to inherit a throne, peerage, or other hereditary honour, but whose position can be displaced by the birth of a person with a better claim to the position in question. This is in contrast to an heir app ...

was Louis XIII's brother

Gaston, Duke of Orléans

''Monsieur'' Gaston, Duke of Orléans (Gaston Jean Baptiste; 24 April 1608 – 2 February 1660), was the third son of King Henry IV of France and his second wife, Marie de' Medici. As a son of the king, he was born a . He later acquired the title ...

, who was Richelieu's enemy. If Gaston became king, Richelieu would quite likely have lost both his job as minister and his life, and so it was in his best interests to thwart Gaston's ambitions.

Supposedly, the substitute father then left for the

Americas

The Americas, sometimes collectively called America, are a landmass comprising the totality of North America and South America.''Webster's New World College Dictionary'', 2010 by Wiley Publishing, Inc., Cleveland, Ohio. When viewed as a sing ...

but returned to France in the 1660s with the aim of extorting money for keeping his secret and was promptly imprisoned. This theory would explain the secrecy surrounding the prisoner, whose true identity would have destroyed the legitimacy of Louis XIV's claim to the throne had it been revealed.

This theory had been suggested by British politician

Hugh Cecil, 1st Baron Quickswood, who nonetheless added that the idea has no historical basis and is entirely hypothetical. Williamson held that: "to say it is a guess with no solid historical basis is merely to say that it is like every other theory on the matter, although it makes more sense than any of the other theories. There is no known evidence that is incompatible with it, even the age of the prisoner, which Cecil had considered a weak point; and it explains every aspect of the mystery." His time spent as a valet to another prisoner renders this idea doubtful, however.

Italian diplomat

Another candidate, much favoured in the 1800s, was Fouquet's fellow prisoner Count Ercole Antonio Mattioli ( Matthioli). He was an Italian diplomat who acted on behalf of the debt-ridden

Charles IV, Duke of Mantua in 1678, in selling

Casale, a strategic fortified town near the border with France. A French occupation would be unpopular, so discretion was essential, but Mattioli leaked the details to France's Spanish enemies after pocketing his commission once the sale had been concluded, and they made a bid of their own before the French forces could occupy the town. Mattioli was kidnapped by the French and thrown into nearby Pignerol in April 1679. The French took possession of Casale two years later.

George Agar-Ellis reached the conclusion that Mattioli was the Man in the Iron Mask when he reviewed documents extracted from French archives in the 1820s. His book, published in English in 1826, was translated into French and published in 1830. German historian Wilhelm Broecking came to the same conclusion independently seventy years later.

Robert Chambers' ''

Book of Days'' supports the claim and places Matthioli in the Bastille for the last 13 years of his life. Since that time, letters sent by Saint-Mars, which earlier historians missed, indicate that Mattioli was held only at Pignerol and Sainte-Marguerite and was not at Exilles or the Bastille and, therefore, it is argued that he can be discounted.

French general

In 1890, Louis Gendron, a French military historian, came across some coded letters and passed them on to

Étienne Bazeries

Étienne Bazeries (21 August 1846, in Port Vendres – 7 November 1931, in Noyon) was a French military cryptanalyst active between 1890 and the World War I, First World War. He is best known for developing the "Bazeries Cylinder", an improved v ...

in the French Army's cryptographic department. After three years, Bazeries managed to read some messages in the

Great Cipher of Louis XIV. One of them referred to a prisoner and identified him as General Vivien de Bulonde. One of the letters written by Louvois made specific reference to de Bulonde's crime.

At the

Siege of Cuneo in 1691, Bulonde was concerned about enemy troops arriving from Austria and ordered a hasty withdrawal, leaving behind his munitions and wounded men. Louis XIV was furious and in another of the letters specifically ordered him "to be conducted to the fortress at Pignerol where he will be locked in a cell and under guard at night, and permitted to walk the battlements during the day with a 330 309." It has been suggested that the 330 stood for ''masque'' and the 309 for full stop. However, in 17th-century French ''avec un masque'' would mean "in a mask".

Some believe that the evidence of the letters means that there is now little need for an alternative explanation of the man in the mask. Other sources, however, claim that Bulonde's arrest was no secret and was actually published in a newspaper at the time. Bulonde was released by order of the king on 11 December 1691. His death is also recorded as happening in 1709, six years after that of the man in the mask.

Son of Charles II

In 1908, Monsignor

Arthur Barnes proposed that the prisoner was

James de la Cloche, the alleged illegitimate son of the reluctant Protestant Charles II of England, who would have been his father's secret intermediary with the Catholic court of France. One of Charles's confirmed illegitimate sons, the

Duke of Monmouth

Duke is a male title either of a monarch ruling over a duchy, or of a member of royalty, or nobility. As rulers, dukes are ranked below emperors, kings, grand princes, grand dukes, and above sovereign princes. As royalty or nobility, they ar ...

, has also been proposed as the man in the mask. A Protestant, he led

a rebellion against his uncle, the Catholic

King James II

James II and VII (14 October 1633 – 16 September 1701) was King of England and Ireland as James II and King of Scotland as James VII from the death of his elder brother, Charles II, on 6 February 1685, until he was deposed in the 1688 Glori ...

. The rebellion failed and Monmouth was executed in 1685. However, in 1768, a writer named Saint-Foix claimed that another man was executed in his place and that Monmouth became the masked prisoner, it being in Louis XIV's interests to assist a fellow Catholic like James, who would not necessarily want to kill his own nephew. Saint-Foix's case was based on unsubstantiated rumours and allegations that Monmouth's execution was faked.

Eustache Dauger de Cavoye

In his letter to Saint-Mars announcing the imminent arrival of the prisoner who would become the Man in the Iron Mask, Louvois gave his name as "Eustache Dauger". Historically, this was deemed to be a prison pseudonym, and a succession of historians therefore attempted to find out the prisoner's real identity. Among them, Maurice Duvivier (1932) wondered if, instead, "Eustache Dauger" might not be the real name of a person whose life and history could be traced; he therefore combed the archives for surnames such as Dauger, Daugers, d'Auger, d'Oger, d'Ogiers and similar forms. He discovered the family of François d'Oger de Cavoye, a captain of Cardinal Richelieu's guard of musketeers, who was married to Marie de Sérignan, a

lady-in-waiting

A lady-in-waiting (alternatively written lady in waiting) or court lady is a female personal assistant at a Royal court, court, attending on a royal woman or a high-ranking nobility, noblewoman. Historically, in Europe, a lady-in-waiting was o ...

at the court of Louis XIV's mother, Queen Anne of Austria. François and Marie had 11 children, of whom six boys and three girls survived into adulthood.

Their third son was named Eustache, who signed his name as "Eustache Dauger de Cavoye". He was born on 30 August 1637 and baptised on 18 February 1639. When his father and two eldest brothers were killed in battle, Eustache became the nominal head of the family. In his 1932 book, Duvivier published evidence that this man had been involved in scandalous and embarrassing events, first in 1659, then again in 1665, and speculated that he had also been linked with ''

l'Affaire des Poisons''.

Disgrace

In April 1659, Eustache Dauger de Cavoye and others were invited by the

duke of Vivonne to an Easter weekend party at the castle of

Roissy-en-Brie. By all accounts, it was a debauched affair of merry-making, with the men involved in all sorts of sordid activities, including attacking an elderly man who claimed to be Cardinal Mazarin's attorney. It was also rumoured, among other things, that a

black mass was enacted and that a pig was baptised as "

Carp

The term carp (: carp) is a generic common name for numerous species of freshwater fish from the family (biology), family Cyprinidae, a very large clade of ray-finned fish mostly native to Eurasia. While carp are prized game fish, quarries and a ...

" in order to allow them to eat pork on Good Friday.

When news of these events became public, an inquiry was held and the various perpetrators jailed or exiled. There is no record as to what happened to Dauger de Cavoye but, in 1665, near the

Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye

The Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye () is a former royal palace in the commune of Saint-Germain-en-Laye, in the department of Yvelines, about 19 km west of Paris, France. Today, it houses the '' Musée d'Archéologie nationale'' (Nationa ...

, he allegedly killed a young

page boy in a drunken brawl involving the Duc de Foix. The two men claimed that they had been provoked by the boy, who was drunk, but the fact that the killing took place close to where Louis XIV was staying at the time meant that this crime was deemed a personal affront to the king and, as a result, Dauger de Cavoye was forced to resign his

commission

In-Commission or commissioning may refer to:

Business and contracting

* Commission (remuneration), a form of payment to an agent for services rendered

** Commission (art), the purchase or the creation of a piece of art most often on behalf of anot ...

. His mother died shortly afterwards. In her will, written a year earlier, she passed over her eldest surviving sons Eustache and Armand, leaving the bulk of the estate to their younger brother Louis. Eustache was restricted in the amount of money to which he had access, having built up considerable debts, and left with barely enough for "food and upkeep".

Affair of the Poisons

In his 1932 book, Duvivier also linked Eustache Dauger de Cavoye to the

Affair of the Poisons, a notorious scandal of 1677–1682 in which people in high places were accused of being involved in black mass and poisonings. An investigation had been launched, but Louis XIV instigated a cover-up when it appeared that his mistress

Madame de Montespan

Françoise-Athénaïs de Rochechouart de Mortemart, Marquise of Montespan (5 October 1640 – 27 May 1707), commonly known as Madame de Montespan (), was a French noblewoman and the most celebrated maîtresse-en-titre, royal mistress of King Lou ...

was involved. The records show that, during the inquiry, the investigators were told about a surgeon named Auger, who had supplied poisons for a black mass that took place before March 1668. Duvivier became convinced that Dauger de Cavoye, disinherited and short of money, had become Auger, the supplier of poisons, and subsequently "Eustache Dauger".

In a letter sent by Louvois to Saint-Mars on 10 July 1680, a few months after Fouquet's death in prison while "Eustache Dauger" was acting as his valet, the minister adds a note in his own handwriting, asking how it was possible that Dauger had made certain objects found in Fouquet's pockets—which Saint-Mars had mentioned in a previous correspondence, now lost—and "how he got the drugs necessary to do so". Duvivier suggested that Dauger had poisoned Fouquet as part of a complex power struggle between Louvois and his rival

Colbert.

Dauger de Cavoye in prison at Saint-Lazare

In 1953, however, French historian Georges Mongrédien published historical documents confirming that, in 1668, Eustache Dauger de Cavoye was already held at the

Prison Saint-Lazare

Saint-Lazare Prison was a prison in the 10th arrondissement of Paris, France. It existed from 1793 until 1935 and was housed in a former motherhouse of the Congregation of the Mission, Vincentians.

History

in the 12th century a Leper colony, ...

in Paris—an asylum, run by monks, which many families used in order to imprison their "

black sheep

In the English language, black sheep is an idiom that describes a member of a group who is different from the rest, especially a family member who does not fit in. The term stems from sheep whose fleece is colored black rather than the more comm ...

"—and that he was still there in 1680, at the same time that "Eustache Dauger", was in custody in Pignerol, hundreds of miles away in the south. These documents include a letter dated 20 June 1678, full of self-pity, sent by Dauger de Cavoye to his sister, the Marquise de Fabrègues, in which he complains about his treatment in prison, where he had already been held "for more than 10 years", and how he was deceived by their brother Louis and by Clérac, their brother-in-law and the manager of Louis's estate.

Dauger de Cavoye also wrote a second letter, this time to the King but undated, outlining the same complaints and requesting his freedom. The best the King would do, however, was to send a letter to the head of Saint-Lazare on 17 August 1678, telling him that "M. de Cavoye should have communication with no one at all, not even with his sister, unless in your presence or in the presence of one of the priests of the mission". The letter was signed by the King and Colbert. A poem written by Louis-Henri de Loménie de Brienne, an inmate in Saint-Lazare at the time, indicates that Eustache Dauger de Cavoye died as a result of heavy drinking in the late 1680s. Historians consider all this proof enough that he was not involved in any way with the man in the mask.

Valet

In 1890, French historian

Jules Lair published an extensive, two-volume biography of Nicolas Fouquet in which he relates Eustache Dauger's arrival at Pignerol in August 1669, his subsequent role as Fouquet's valet, and their secret interactions with Lauzun. Lair believed that "Eustache Dauger" was the new prisoner's real name, that he was French,

catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

and a professional valet who had been employed for a specific task which was never clarified: "he was probably one of these men tasked with a shady mission—such as the removal of documents or kidnapping, or perhaps worse—and whose silence is secured by death or imprisonment once the deed is done." Lair also conjectured an explanation for Louvois's obsessive insistence that Dauger and Lauzun should be kept apart at all times, by reference to the fact that Dauger was arrested near Dunkirk during the negotiations of the

Secret Treaty of Dover, in which Lauzun had also participated. Lair asserted that the two men knew each other or, at the very least, had been aware of each other.

In 2016, American historian Paul Sonnino speculated that Eustache Dauger could have been a valet of Cardinal Mazarin's treasurer, Antoine-Hercule Picon. A native of Languedoc, Picon, upon entering the service of Colbert after Mazarin's death, might have picked up a valet from Senlis, where the name "Dauger" abounds. In his book, Sonnino asserts that Mazarin led a double life, "one as a statesman, the other as a loan shark", and that one of the clients he embezzled was

Henrietta Maria

Henrietta Maria of France (French language, French: ''Henriette Marie''; 25 November 1609 – 10 September 1669) was List of English royal consorts, Queen of England, List of Scottish royal consorts, Scotland and Ireland from her marriage to K ...

, the widow of

Charles I of England

Charles I (19 November 1600 – 30 January 1649) was King of Kingdom of England, England, Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland, and Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland from 27 March 1625 until Execution of Charles I, his execution in 1649.

Charles was born ...

. According to Sonnino's theory, Louis XIV was complicit and instructed his ambassador in England to stonewall Charles II over the return of his parents' possessions. In 1669, however, Louis wanted to enlist Charles in a war against the Dutch and therefore worried about the subject of Mazarin's estate entering into the negotiations. Sonnino concludes by stating that Eustache Dauger, who might have been Picon's valet, was arrested and incarcerated for revealing something about the disposition of Mazarin's fortune, and that this is why he was threatened with death if he disclosed anything about his past.

In 2021, British historian Josephine Wilkinson mentioned the theory proposed by French historian Bernard Caire in 1987, whereby "Eustache" was not the prisoner's first name but his real surname. Since French historian Jean-Christian Petitfils had earlier asserted that "Dauger" was a misspelling of "Danger" (or d'Angers), Caire suggested that this appellation was used to indicate the prisoner originated from the town of

Angers

Angers (, , ;) is a city in western France, about southwest of Paris. It is the Prefectures of France, prefecture of the Maine-et-Loire department and was the capital of the province of Duchy of Anjou, Anjou until the French Revolution. The i ...

. Wilkinson also supported the theory proposed by Petitfils—and by Jules Lair in 1890—that, as a valet (perhaps to

Henrietta of England), this "Eustache" had committed some indiscretion which risked compromising the relations between Louis XIV and Charles II at a sensitive time during the negotiations of the Secret Treaty of Dover against the

Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, commonly referred to in historiography as the Dutch Republic, was a confederation that existed from 1579 until the Batavian Revolution in 1795. It was a predecessor state of the present-day Netherlands ...

. In July 1669, Louis had suddenly and inexplicably fallen out with Henrietta and, since the two had previously been very close, it did not go unnoticed. Wilkinson therefore suggested a link between this event and this valet's arrest in Calais later that month.

Historical documents and archives

History of the Bastille archives

When the Bastille was stormed on 14 July 1789, the mob were surprised to find only seven prisoners, as well as a room full of neatly kept boxes containing documents that had been carefully filed since 1659. These archives held records, not only of all the prisoners who had been incarcerated there, but also of all the individuals who had been locked up, banished into exile, or simply tried within the limits of Paris as a result of a ''

lettre de cachet

''Lettres de cachet'' (; ) were letters signed by the king of France, countersigned by one of his ministers, and closed with the royal seal. They contained orders directly from the king, often to enforce actions and judgments that could not b ...

''. Throughout the 18th century, archivists had been working zealously at keeping these records in good order and which, on the eve of the French revolution, had amounted to hundreds of thousands of documents.

As the fortress was being ransacked, the pillaging lasted for two days during which documents were burned, torn, thrown from the top of towers into the moats and trailed through the mud. Many documents were stolen, or taken away by collectors, writers, lawyers, and even by Pierre Lubrowski, an attaché in the Russian embassy—who sold them to emperor

Alexander I Alexander I may refer to:

* Alexander I of Macedon, king of Macedon from 495 to 454 BC

* Alexander I of Epirus (370–331 BC), king of Epirus

* Alexander I Theopator Euergetes, surnamed Balas, ruler of the Seleucid Empire 150-145 BC

* Pope Alex ...

in 1805, when they were deposited at the

Hermitage Palace—and many ended up dispersed throughout France and the rest of Europe. A company of soldiers was posted on 15 July to guard the fortress and, in particular, to prevent any more looting of the archives. On 16 July, the Electoral Assembly created a commission assigned to rescue the archives; on arrival at the fortress, they found that many boxes had been emptied or destroyed, leaving an enormous pile of papers in a complete state of disorder. During the session of 24 July, the Electoral Assembly passed a resolution enjoining citizens to return documents to the Hôtel de Ville; restitutions were numerous and the surviving documents eventually stored at the city's library, then located at the convent of Saint-Louis-de-la-Culture.

On 22 April 1797,

Hubert-Pascal Ameilhon was appointed chief librarian of the

Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal and obtained a decree that secured the Bastille archive under his care. However, the librarians were so daunted by this volume of 600,000 documents that they stored them in a backroom, where they languished for over forty years. In 1840, François Ravaisson found a mass of old papers under the floor in his kitchen at the Arsenal library and realised he had rediscovered the archives of the Bastille, which required a further fifty years of laborious restoration; the documents were numbered, and a catalogue was compiled and published as the 20th century was about to dawn. Eventually, the archives of the Bastille were made available for consultation by any visitor to the Arsenal library, in rooms specially fitted up for them.

Other archives

In addition to the Bibliothèque de l'Arsenal, several other archives host historical documents that were consulted by historians researching the enigma of the Man in the Iron Mask: the

Archives of the Foreign Ministry (Archives des Affaires étrangères),

the

Archives Nationales,

the

Bibliothèque nationale de France

The (; BnF) is the national library of France, located in Paris on two main sites, ''Richelieu'' and ''François-Mitterrand''. It is the national repository of all that is published in France. Some of its extensive collections, including bo ...

,

the

Sainte-Geneviève Library,

and the

Service Historique de la Défense ( Anciennes Archives de la Guerre).

Historians of the Man in the Iron Mask

In his historical essay published in 1965 and expanded in 1973, Marcel Pagnol praised a number of historians who consulted the archives with the goal of elucidating the enigma of the Man in the Iron Mask: Joseph Delort (1789–1847), Marius Topin (1838–1895), Théodore Iung (1833–1896), Maurice Duvivier (18??–1936), and Georges Mongrédien (1901–1980). Along with Pierre Roux-Fazillac (1746–1833), François Ravaisson (1811–1884), Jules Loiseleur (1816–1900),

Jules Lair (1836–1907), and

Frantz Funck-Brentano (1862–1947), these historians uncovered and published the bulk of historical documents that enabled some progress to be made towards that goal.

In particular, Mongrédien was the first to publish (1952) a complete reference of historical documents on which previous authors had relied only selectively. He was also one of the few historians who did not champion any particular candidate, preferring instead to review and analyse objectively the facts revealed by the documents. Giving full credit to Jules Lair for being the first to propose the candidacy of "Eustache Dauger" in 1890, Mongrédien demonstrated that, among all the state prisoners who were ever in the care of Saint-Mars, only the one arrested under that name in 1669 could have died in the Bastille in 1703, and was therefore the only possible candidate for the man in the mask. Although he also pointed out that no documents had yet been found that revealed either the real identity of this prisoner or the cause of his long incarceration, Mongrédien's work was significant in that it made it possible to eliminate all the candidates whose vital dates, or life circumstances for the period of 1669–1703, were already known to modern historians.

In October 1965, Mongrédien published a review, in the journal ''La Revue des Deux Mondes'', of the first edition of Pagnol's essay. At the end of this review, Mongrédien mentioned being told that the

Archives of the Ministry of Defense located at the Château de Vincennes still held unsorted and uncatalogued bundles of Louvois's correspondence. He speculated that, if this were the case, then these bundles might contain a letter from July 1669 revealing the reasons for "Eustache Daugers arrest near Dunkirk.

In popular culture

Literature

In addition to being the subject of scholarly research carried out by historians, the Man in the Iron Mask inspired literary works of fiction, many of which elaborate on the legend of the prisoner being a twin brother of Louis XIV, such as Alexandre Dumas's popular novel, ''Le Vicomte de Bragelonne'' (1850).

Novels

* Mouhy, Charles de Fieux, Chevalier de, (1747). ''Le Masque de Fer ou les Aventures admirables du Père et du Fils''. The Hague: Pierre de Hondt.

*

Regnault-Warin, Jean-Joseph (1804). ''L'Homme Au Masque de Fer'', 4 vol. in-12. Paris: Frechet.

* Guénard Brossin de Méré, Élisabeth (1821). ''Histoire de l'Homme Au Masque de Fer, ou les Illustres Jumeaux'', 4 vol. Paris: Lebègue.

* Dumas, Alexandre (1848–1850). ''Le Vicomte de Bragelonne, ou Vingt ans plus tard'', 19 vol. Paris: Michel Lévy.

* Letourneur, L. (1849). ''Histoire de l'Homme au masque de fer''. Nancy.

* Leynadier, Camille (1857). ''Le Masque de fer''. Paris.

* Meynaud, Joachim (1869)

st pub. 1858 ''Le Masque de fer, journal de sa captivité à Sainte-Marguerite''. Nancy: Wagner.

* Robville de, T. (1865). ''L'Homme au masque de fer ou Les Deux Jumeaux''. Paris.

* Koenig, E. A. (1873). ''L'Homme au masque de fer, ou le somnambule de Paris''. Zurich: Robert.

*

Féré, Octave (1876). ''L'Homme au masque de fer''. Paris.

*

Du Boisgobey, Fortuné (1878). ''Les deux merles de M. de Saint-Mars''. Paris: E. Dentu.

* Ladoucette, Edmond (1910). ''Le Masque de fer''. Paris: A. Fayard.

*

Féval (fils), Paul; Lassez, Michel (1928). ''L'évasion du masque de fer''. Paris: A. Fayard.

*

Dunan, Renée (1929). ''Le masque de fer ou l'amour prisonnier''. Paris: Bibliothèque des Curieux.

*

Bernède, Arthur (1930). ''L'Homme au masque de fer''. Paris: Éditions Tallandier.

* Kerleck de, Jean (1931)

st pub. 1927 ''La Maîtresse du Masque de Fer''. Paris: Baudinière.

* Refreger, Omer (alias

Léo Malet) (1945). ''L'Évasion du Masque de fer''. Paris: Les Éditions et Revues Françaises.

* Masini de, Clément (1964). ''La Plus dramatique énigme du 18ème siècle : la véritable histoire de l'homme au masque de fer''. Paris: Édition du Scorpion.

* Cyrille (1966). ''Masques de fer''. Paris: Éditions Alsatia.

* Desprat, Jean-Paul (1991). ''Le Secret des Bourbons''. Paris: André Balland. .

* Dufreigne, Jean-Pierre (1993). ''Le Dernier Amour d'Aramis''. Paris: Grasset. .

* Benzoni, Juliette (1998). ''Secret d'État, tome III, Le Prisonnier masqué''. Paris: Plon. .

Plays

* Arnould (1790). ''L'Homme au masque de fer ou le Souterrain''. Pantomime in four acts, performed at the ''

Théâtre de l'Ambigu-Comique

The (, literally, Theatre of the Comic-Ambiguity), a former Parisian theatre, was founded in 1769 on the boulevard du Temple immediately adjacent to the Théâtre de Nicolet. It was rebuilt in 1770 and 1786, but in 1827 was destroyed by fire. A ...

'' on 7 January 1790.

* Le Grand, Jérôme (1791). ''Louis XIV et le Masque de fer ou Les Princes jumeaux''. Tragedy in five acts and in verse, first performed at the ''

Théâtre Molière'' in Paris on 24 September 1791.

* Arnould & Fournier (1831). ''L'Homme au masque de fer''. Drama in five acts, performed at the ''

Théâtre de l'Odéon'' on 3 August 1831.

*

Serle, Thomas James (1832). ''The Man in the Iron Mask : an historical play in five acts''. First performed at the

Royal Coburg Theatre, 1832.

*

Hugo, Victor (1839). ''Les Jumeaux''. Unfinished drama. Paris, 1884.

* Dumas, Alexandre (1861). ''Le Prisonnier de la Bastille''. Drama in five acts, first performed at the ''

Théâtre du Cirque Impérial'' on 22 March 1861.

* Maurevert, Georges (1884). ''Le Masque de fer''. Fantasy in one act. Paris.

Max Goldberg(1899). ''The Man in the Iron Mask''. Performed at the London

Adelphi Theatre

The Adelphi Theatre is a West End theatre, located on the Strand in the City of Westminster, central London. The present building is the fourth on the site. The theatre has specialised in comedy and musical theatre, and today it is a receiv ...

, 11 March–20 May 1899 (68 perf.). The cast included

Norman Forbes,

Valli Valli, and

William L. Abingdon.

* Villia (1909). ''L'Homme au masque de fer''. Drama in three acts, preceded by a historical review of recent works. Paris.

*

Rostand, Maurice (1923). ''Le Masque de fer''. Play in four acts and in verse, first performed at the ''

Théâtre Cora Laparcerie'' on 1 October 1923.

* Richter, Charles de (1955). ''Le Masque de fer''. Comedy in one act. Toulon.

Poems

*

Vigny, Alfred de, (1821). ''La Prison'', in ''Poèmes antiques et modernes'' (1826). Paris: Urbain Canel.

* Quinet, Benoît (1837). ''Derniers moments de l'Homme au masque de fer''. Dramatic poem. Bruxelles: Hauman, Cattoir et Cie.

* Leconte, Sebastien-Charles (1911). ''Le Masque de fer''. Paris: Mercure de France.

Music

*

John St John (1789). ''The Island of St. Marguerite'' (Opera).

*

Hugo Riesenfeld

Hugo Riesenfeld (January 26, 1879 – September 10, 1939) was an Austrian-American composer. As a film director, he began to write his own orchestral compositions for silent films in 1917, and co-created modern production techniques where film ...

(1929). Soundtrack of the film ''

The Iron Mask''.

*

Lud Gluskin &

Lucien Moraweck (1939). Soundtrack of the film ''

The Man in the Iron Mask''.

*

Allyn Ferguson

Allyn Malcolm Ferguson Jr. (October 18, 1924 – June 23, 2010) was an American composer, whose works include the themes for 1970s television programs ''Barney Miller'' and ''Charlie's Angels'' (1976-1981), which he co-wrote with Jack Elliott ( ...

(1977). Soundtrack of the film ''

The Man in the Iron Mask''.

*

Billy Bragg

Stephen William Bragg (born 20 December 1957) is an English singer, songwriter, musician, author and political activist. His music blends elements of folk music, punk rock and protest songs, with lyrics that mostly span political or romantic th ...

(1983). "The Man in the Iron Mask" (Song), in ''

Life's a Riot with Spy vs Spy''.

*

Paul Young (1985). "The Man in the Iron Mask" (Song), in ''

The Secret of Association''.

*

Nick Glennie-Smith

Nickolas Glennie-Smith is an English film score composer, Conducting, conductor, and musician who is a frequent collaborator with Hans Zimmer, contributing to scores including ''The Rock (film), The Rock'' (nominated for the Academy Awards, Acad ...

(1998). Soundtrack of the film ''

The Man in the Iron Mask''.

*

Heartland (2002). "The Man in the Iron Mask" (Song), in ''Communication Down''.

* Samurai Of Prog (2023). ''The Man in the Iron Mask'' (Album).

Film and television

Several films have been made around the mystery of the Man in the Iron Mask, including: l

''

The Iron Mask'' (1929) starring

Douglas Fairbanks

Douglas Elton Fairbanks Sr. (born Douglas Elton Thomas Ullman; May 23, 1883 – December 12, 1939) was an American actor and filmmaker best known for being the first actor to play the masked Vigilante Zorro and other swashbuckler film, swashbu ...

;

''

The Man in the Iron Mask'' (1939) starting

Louis Hayward;

the British television production starring

Richard Chamberlain (1977); and

the American film starring

Leonardo DiCaprio

Leonardo Wilhelm DiCaprio (; ; born November 11, 1974) is an American actor and film producer. Known for Leonardo DiCaprio filmography, his work in biographical and period films, he is the recipient of List of awards and nominations received ...

(1998). These films were all loosely adapted from Dumas' book ''

The Vicomte de Bragelonne'', where the prisoner was an identical twin of Louis XIV and made to wear an iron mask, per the legend created by Voltaire.

In the Japanese Manga ''

Berserk'' (1989), one of the protagonists,

Griffith

Griffith may refer to:

People

* Griffith (name)

* Griffith (surname)

* Griffith (given name)

Places Antarctica

* Mount Griffith, Ross Dependency

* Griffith Peak (Antarctica), Marie Byrd Land

* Griffith Glacier, Marie Byrd Land

* Griffith Ridge, ...

, was imprisoned, tortured, and forced to wear an iron mask. He becomes an antagonist shortly thereafter. In the Japanese manga ''

One Piece

''One Piece'' (stylized in all caps) is a Japanese manga series written and illustrated by Eiichiro Oda. It follows the adventures of Monkey D. Luffy and his crew, the Straw Hat Pirates, as he explores the Grand Line in search of the myt ...

'' (1997), one of the protagonists,

Sanji, was imprisoned during childhood and forced to wear an iron mask, resembling the story of the French prisoner.

The movie ''

G.I. Joe: The Rise of Cobra'' (2009) features fictional character James McCullen IX who is the ancestor of the modern day antagonist James McCullen XXIV. In the 1600s, McCullen IX was caught selling weapons to both sides of an unspecified war, and an example was made of him by welding a burning iron mask to his face.

In the second season of the television show ''

The Flash

The Flash is the name of several superheroes appearing in American comic books published by DC Comics. Created by writer Gardner Fox and artist Harry Lampert, the original Flash first appeared in ''Flash Comics'' #1 (cover date, cover-dated Jan ...

'' in 2014, the Man in the Iron Mask is held hostage by ''

Hunter Zolomon

Hunter Zolomon, otherwise known as Zoom is a supervillain appearing in American comic books published by DC Comics. The second character to assume the Reverse-Flash mantle, he serves as the archnemesis of Wally West and an enemy of Barry Allen.

...

''/Zoom, who pretends to be the superhero ''

Flash''. The Man in the Iron Mask is eventually revealed to be the real Jay Garrick of his universe, and a doppelganger of Henry Allen, Barry Allen/The Flash's father.

The Man in the Iron Mask is portrayed as the Duc de Sullun (inversion of ''nullus'', Latin for 'no one') in the first two episodes of the third season of the TV drama series ''

Versailles

The Palace of Versailles ( ; ) is a former royal residence commissioned by King Louis XIV located in Versailles, Yvelines, Versailles, about west of Paris, in the Yvelines, Yvelines Department of Île-de-France, Île-de-France region in Franc ...

'' (2018). In the program, he is visited in the Bastille by

Philippe I, Duke of Orléans

''Monsieur'' Philippe I, Duke of Orléans (21 September 1640 – 9 June 1701) was the younger son of King Louis XIII of France and Anne of Austria, and the younger brother of King Louis XIV. He was the founder of the House of Orléans, a ...

on his search to find men to send to the Americas and is revealed to be the secret older brother of

Louis XIV

LouisXIV (Louis-Dieudonné; 5 September 16381 September 1715), also known as Louis the Great () or the Sun King (), was King of France from 1643 until his death in 1715. His verified reign of 72 years and 110 days is the List of longest-reign ...

and Philippe I, born from an affair between

Louis XIII

Louis XIII (; sometimes called the Just; 27 September 1601 – 14 May 1643) was King of France from 1610 until his death in 1643 and King of Navarre (as Louis II) from 1610 to 1620, when the crown of Navarre was merged with the French crown.

...

and Louise de La Fayette since his wife struggled to produce him an heir.

In "

What If... the Avengers Assembled in 1602?", the eighth episode of the

second season (2023) of the

Marvel Cinematic Universe

The Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU) is an American media franchise and shared universe centered on List of Marvel Cinematic Universe films, a series of superhero films produced by Marvel Studios. The films are based on characters that appe ...

Disney+

The Walt Disney Company, commonly referred to as simply Disney, is an American multinational mass media and entertainment industry, entertainment conglomerate (company), conglomerate headquartered at the Walt Disney Studios (Burbank), Walt Di ...

series ''

What If...?'', the Man in the Iron Mask is a variant of

Bruce Banner

The Hulk is a superhero appearing in American comic books published by Marvel Comics. Created by writer Stan Lee and artist Jack Kirby, the character first appeared in the debut issue of ''The Incredible Hulk (comic book), The Incredible Hulk ...

, who is freed by

Captain Peggy Carter, breaking the iron mask after transforming into

the Hulk

The Hulk is a superhero appearing in American comic books published by Marvel Comics. Created by writer Stan Lee and artist Jack Kirby, the character first appeared in the debut issue of '' The Incredible Hulk'' (May 1962). In his comic book ...

.

Gallery

Explanatory footnotes

References

Citations

Sources

Books

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

Conference proceedings

*

*

AV Media

*

Websites

*

*

*

*

*

*

Magazines and newspapers

*

*

Further reading

Books

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

Conference proceedings

*

**

*

**

**

**

**

**

**

**

**

**

Websites

*

External links

*

List of plays and films about the Man in the Iron Mask at the Encyclopaedia of South African Theatre, Film, Media and Performance (ESAT)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Man In The Iron Mask, The

Works based on The Three Musketeers

17th-century births

1703 deaths

17th-century French people

18th-century French people

People of the Ancien Régime

Prisoners and detainees of France

Unidentified people

French people who died in prison custody

French folklore

Masks

People associated with the Affair of the Poisons

Year of birth unknown

Punitive masks

Alexandre Dumas characters

The earliest surviving records of the masked prisoner are from 19 July 1669, when

The earliest surviving records of the masked prisoner are from 19 July 1669, when  On 18 September 1698, Saint-Mars took up his new post as governor of the

On 18 September 1698, Saint-Mars took up his new post as governor of the  * Arnould (1790). ''L'Homme au masque de fer ou le Souterrain''. Pantomime in four acts, performed at the ''

* Arnould (1790). ''L'Homme au masque de fer ou le Souterrain''. Pantomime in four acts, performed at the '' Several films have been made around the mystery of the Man in the Iron Mask, including: l

'' The Iron Mask'' (1929) starring

Several films have been made around the mystery of the Man in the Iron Mask, including: l

'' The Iron Mask'' (1929) starring