Major Taylor on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

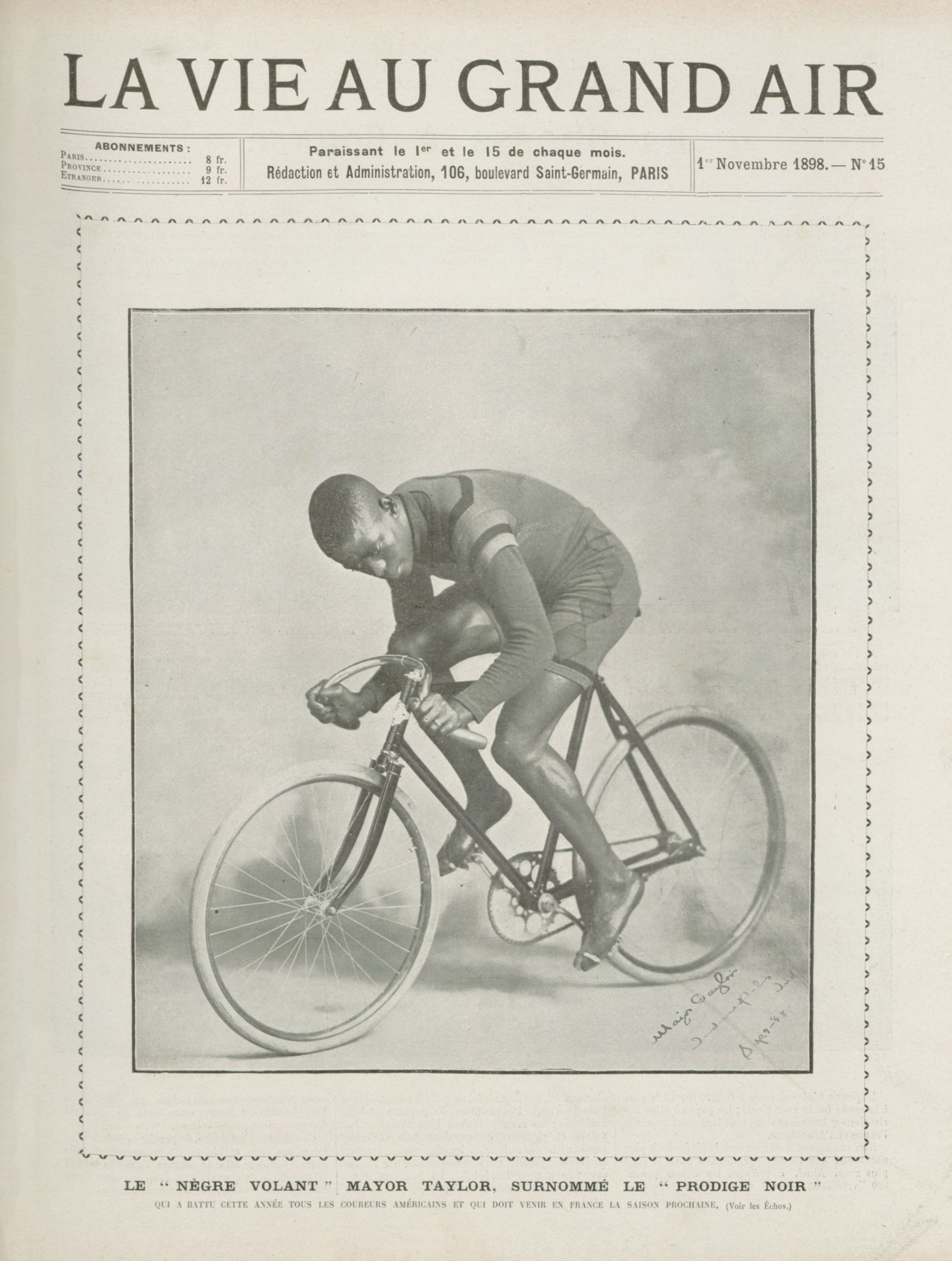

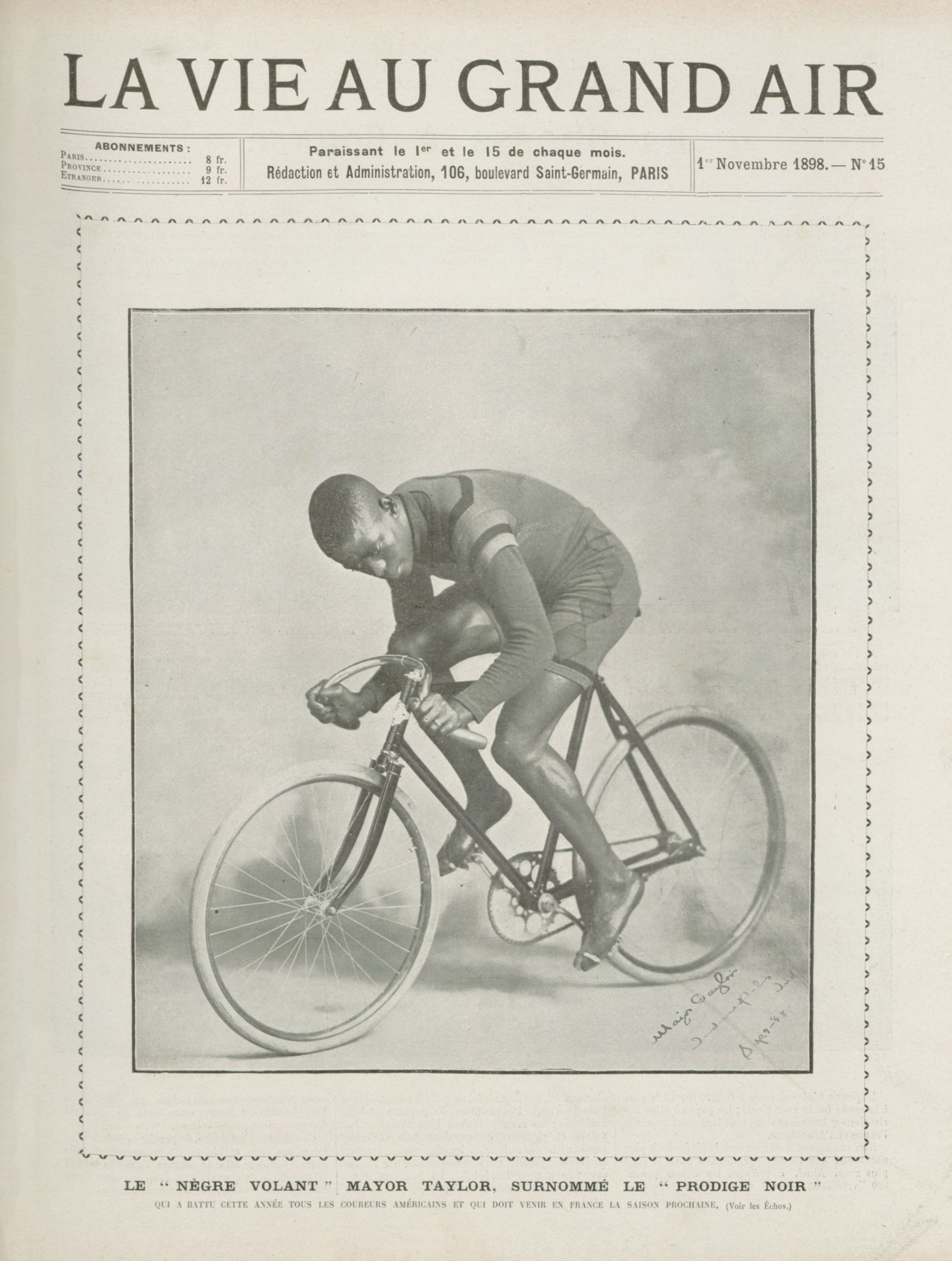

Marshall Walter "Major" Taylor (November 26, 1878 – June 21, 1932) was an American professional

Major Taylor won his first significant cycling competition on June 30, 1895, when he was the only rider to finish a grueling road race near his hometown of Indianapolis. During the race Taylor received threats from his white competitors, who did not know that he had entered the event until the start of the race. A few days later, on July 4, 1895, Taylor won a ten-mile road race in Indianapolis that made him eligible to compete at the national championships for Black racers in Chicago. Later that summer, he won the ten-mile championship race in Chicago by ten lengths and set a new record for Black cyclists of 27:32. In 1895, Taylor and Munger relocated from Indianapolis to Worcester which, at that time, was a center of the U.S. bicycle industry and included half-a-dozen factories and thirty bicycle shops. Munger, who was Taylor's employer, lifelong friend, and mentor, had decided to move his bicycle manufacturing business to the state of

In 1895, Taylor and Munger relocated from Indianapolis to Worcester which, at that time, was a center of the U.S. bicycle industry and included half-a-dozen factories and thirty bicycle shops. Munger, who was Taylor's employer, lifelong friend, and mentor, had decided to move his bicycle manufacturing business to the state of

Taylor initially raced for Munger's Worcester Cycle Manufacturing Company. After the company went into receivership in 1897 he joined other racing teams. 1897 was the first full year in which Taylor competed on the professional racing circuit. Early in the season, at the Bostonian Cycle Club's "Blue Ribbon Meet" on May 19, 1897, Taylor rode a Comet bicycle to win first place in the one-mile open professional race. On June 26, he won a quarter-mile () race at the track at Manhattan Beach, Brooklyn. Taylor also beat Eddie Bald in a one-mile race in

Taylor initially raced for Munger's Worcester Cycle Manufacturing Company. After the company went into receivership in 1897 he joined other racing teams. 1897 was the first full year in which Taylor competed on the professional racing circuit. Early in the season, at the Bostonian Cycle Club's "Blue Ribbon Meet" on May 19, 1897, Taylor rode a Comet bicycle to win first place in the one-mile open professional race. On June 26, he won a quarter-mile () race at the track at Manhattan Beach, Brooklyn. Taylor also beat Eddie Bald in a one-mile race in  Early in the 1898 racing season Taylor beat Bald at Manhattan Beach, Brooklyn,, NY. On June 17th at the Charles River Track in

Early in the 1898 racing season Taylor beat Bald at Manhattan Beach, Brooklyn,, NY. On June 17th at the Charles River Track in

Following his record-setting successes in the U.S. and Canada, Taylor agreed to a European tour. In 1901, Taylor made his first trip to Europe, but returned to compete in the U.S. after the conclusion of the European spring racing season. During his European tour Taylor still refused to race on Sundays, when most of the finals were held, because of his religious convictions. It was reported that Taylor took a

Following his record-setting successes in the U.S. and Canada, Taylor agreed to a European tour. In 1901, Taylor made his first trip to Europe, but returned to compete in the U.S. after the conclusion of the European spring racing season. During his European tour Taylor still refused to race on Sundays, when most of the finals were held, because of his religious convictions. It was reported that Taylor took a  ]

Taylor was popular among the European race fans and news reporters: "Everywhere he went he was mobbed, talked about, or written up." In 1901, Taylor won 18 of the 24 European races he entered, notching up 42 victories when the individual heats are counted. A highlight of Taylor's European tour in 1901 was the two match races with French champion Edmond Jacquelin at the

]

Taylor was popular among the European race fans and news reporters: "Everywhere he went he was mobbed, talked about, or written up." In 1901, Taylor won 18 of the 24 European races he entered, notching up 42 victories when the individual heats are counted. A highlight of Taylor's European tour in 1901 was the two match races with French champion Edmond Jacquelin at the

Indy Cycloplex

include the Major Taylor Racing League track series, and from 2015, the Major Taylor Cross Cup second division UCI

Major Taylor Association

was formed by locals with the goal of erecting a permanent memorial to Taylor outside the Worcester Public Library and telling his story. On July 24, 2006, the city renamed the Worcester Center Boulevard, a high-traffic downtown street, to Major Taylor Boulevard. At the same time, funding for the memorial was secured with the Massachusetts Legislature approving $205,000, signed by governor

National Brotherhood of Cyclists

(NBC), a nonprofit organization that aims to further diversity in cycling. The Major Taylor Trail, a

Taylor's wife, Daisy Victoria Morris, was born on January 28, 1876, in

Taylor's wife, Daisy Victoria Morris, was born on January 28, 1876, in

The Major Taylor Association

The Major Taylor Society

Major Taylor: Fastest Cyclist in the World

{{DEFAULTSORT:Taylor, Major 1878 births 1932 deaths African-American sportsmen American male cyclists American track cyclists Cyclists from Indiana Sportspeople from Indianapolis Sportspeople from Worcester, Massachusetts UCI Track Cycling World Champions (men) 20th-century African-American sportsmen History of cycling in the United States

cyclist

Cycling, also known as bicycling or biking, is the activity of riding a bicycle or other types of pedal-driven human-powered vehicles such as balance bikes, unicycles, tricycles, and quadricycles. Cycling is practised around the world fo ...

. He has been called "the first Black American global sports superstar."

He was born and raised in Indianapolis

Indianapolis ( ), colloquially known as Indy, is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Indiana, most populous city of the U.S. state of Indiana and the county seat of Marion County, Indiana, Marion ...

, where he worked in bicycle shops and began racing multiple distances in the track and road

A road is a thoroughfare used primarily for movement of traffic. Roads differ from streets, whose primary use is local access. They also differ from stroads, which combine the features of streets and roads. Most modern roads are paved.

Th ...

disciplines of cycling. As a teenager, he moved to Worcester, Massachusetts

Worcester ( , ) is the List of municipalities in Massachusetts, second-most populous city in the U.S. state of Massachusetts and the list of United States cities by population, 113th most populous city in the United States. Named after Worcester ...

, with his employer/coach/mentor and continued his successful amateur career, which included breaking track records.

Taylor turned professional in 1896, at the age of 18, living in cities on the East Coast and participating in multiple track events including six-day races. He moved his focus to the sprint event in 1897, competing in a national racing circuit, winning many races and gaining popularity with the public. In 1898 and 1899, he set numerous world records in race distances ranging from the quarter-mile () to the two-mile ().

Taylor won the 1-mile sprint event at the 1899 world track championships to become the first Black American to achieve the level of world champion and the second Black

Black is a color that results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without chroma, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness.Eva Heller, ''P ...

athlete to win a world championship in any sport (following Canadian

Canadians () are people identified with the country of Canada. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Canadians, many (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of their being ''C ...

boxer George Dixon, 1890). Taylor was also a national sprint champion in 1899 and 1900. He raced in the U.S., Europe and Australia from 1901 to 1904, beating the world's best riders. After a -year hiatus, he made a comeback in 1907–1909, before retiring at age 32 to his home in Worcester in 1910.

Towards the end of his life Taylor faced severe financial difficulties. He spent the final two years of his life in Chicago

Chicago is the List of municipalities in Illinois, most populous city in the U.S. state of Illinois and in the Midwestern United States. With a population of 2,746,388, as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, it is the List of Unite ...

, Illinois, where he died of a heart attack in 1932.

Throughout his career he challenged the racial prejudice he encountered on and off the track and became a pioneering role model for other athletes facing racial discrimination

Discrimination is the process of making unfair or prejudicial distinctions between people based on the groups, classes, or other categories to which they belong or are perceived to belong, such as race, gender, age, class, religion, or sex ...

. Several cycling clubs, trails, and events in the U.S. have been named in his honor, as well as the Major Taylor Velodrome in Indianapolis and Major Taylor Boulevard in Worcester. Other tributes include memorials and historic markers in Worcester MA, Indianapolis, and at his gravesite in Chicago. He has also been memorialized in film, music and fashion.

Early life

Marshall Walter Taylor was the son of Gilbert Taylor, aCivil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

veteran, and Saphronia Kelter Taylor. His parents migrated from Louisville, Kentucky

Louisville is the List of cities in Kentucky, most populous city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky, sixth-most populous city in the Southeastern United States, Southeast, and the list of United States cities by population, 27th-most-populous city ...

, and settled on a farm in Bucktown, Indiana, a rural area on the western edge of Indianapolis

Indianapolis ( ), colloquially known as Indy, is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Indiana, most populous city of the U.S. state of Indiana and the county seat of Marion County, Indiana, Marion ...

. Taylor, born on November 26, 1878 in Indianapolis, was one of eight children in the family of five girls and three boys. Around 1887, his father began working in Indianapolis as a coachman

A coachman is a person who drives a Coach (carriage), coach or carriage, or similar horse-drawn vehicle. A coachman has also been called a coachee, coachy, whip, or hackman.

The coachman's first concern is to remain in full control of the hors ...

for a wealthy white family named Southard.

When Taylor was a child, he occasionally accompanied his father to work and soon became a close friend of the Southards' son, Daniel, who was the same age. Approximately from the age of 8 until he was about 12, Taylor lived with the Southards family and along with Daniel was tutored at their home. Taylor's living arrangement with the Southards provided him with more advantages than his parents could provide; however, this period of his life abruptly ended when the Southards moved to Chicago. Taylor, who remained in Indianapolis, returned to live at his parents' home and "was soon thrust into the real world."

The Southards had provided Taylor with his first bicycle

A bicycle, also called a pedal cycle, bike, push-bike or cycle, is a human-powered transport, human-powered or motorized bicycle, motor-assisted, bicycle pedal, pedal-driven, single-track vehicle, with two bicycle wheel, wheels attached to a ...

. By 1891 or early 1892, he had become such an expert trick rider that Tom Hay, an Indianapolis bicycle shop owner, hired him to perform bicycle stunts in front of the Hay and Willits bicycle shop. Taylor earned $6 a week to clean the shop and perform the stunts, plus a free bicycle worth $35. It is likely that Taylor received his nickname of "Major" because he performed the cycling stunts wearing a military uniform.

Early years and move to East Coast

Although Major Taylor competed in bothroad

A road is a thoroughfare used primarily for movement of traffic. Roads differ from streets, whose primary use is local access. They also differ from stroads, which combine the features of streets and roads. Most modern roads are paved.

Th ...

and track races during his amateur career, he excelled in the track sprints, especially the race. The first cycling race Taylor won was a amateur event in Indianapolis in 1890. He received a 15-minute handicap (head start) in the road race because of his young age. Taylor subsequently traveled to Peoria, Illinois

Peoria ( ) is a city in Peoria County, Illinois, United States, and its county seat. Located on the Illinois River, the city had a population of 113,150 as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, making it the List of municipalities in Ill ...

, to compete in another meet, finishing in third place in the under-16 age category.

Major Taylor encountered racial prejudice throughout his racing career from some of his competitors. In addition, some local track owners feared that other cyclists would refuse to compete if Taylor was present for a bicycle race and banned him from their tracks. In 1893, for example, after the 15-year-old Taylor beat a one-mile amateur track record, he was "hooted" and then barred from the track. Taylor joined the See-Saw Cycling Club, which was formed by black

Black is a color that results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without chroma, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness.Eva Heller, ''P ...

cyclists of Indianapolis who were unable to join the local all-white

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no chroma). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully (or almost fully) reflect and scatter all the visible wa ...

br>Zig-Zag Cycling ClubMajor Taylor won his first significant cycling competition on June 30, 1895, when he was the only rider to finish a grueling road race near his hometown of Indianapolis. During the race Taylor received threats from his white competitors, who did not know that he had entered the event until the start of the race. A few days later, on July 4, 1895, Taylor won a ten-mile road race in Indianapolis that made him eligible to compete at the national championships for Black racers in Chicago. Later that summer, he won the ten-mile championship race in Chicago by ten lengths and set a new record for Black cyclists of 27:32.

In 1895, Taylor and Munger relocated from Indianapolis to Worcester which, at that time, was a center of the U.S. bicycle industry and included half-a-dozen factories and thirty bicycle shops. Munger, who was Taylor's employer, lifelong friend, and mentor, had decided to move his bicycle manufacturing business to the state of

In 1895, Taylor and Munger relocated from Indianapolis to Worcester which, at that time, was a center of the U.S. bicycle industry and included half-a-dozen factories and thirty bicycle shops. Munger, who was Taylor's employer, lifelong friend, and mentor, had decided to move his bicycle manufacturing business to the state of Massachusetts

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode ...

, which was also a more tolerant area of the country.

Munger and business partner Charles Boyd established the Worcester Cycle Manufacturing Company with factories in Worcester and Middletown, Connecticut

Middletown is a city in Middlesex County, Connecticut, United States. Located along the Connecticut River, in the central part of the state, 16 miles (25.749504 km) south of Hartford, Connecticut, Hartford. Middletown is the largest city in the L ...

. For Taylor, who continued to work for Munger as a bicycle mechanic and messenger between the company's two factory locations, the move to the East Coast offered "higher visibility, larger crowds, increased sponsorship dollars, and greater access to world-class cycling venues." After Taylor's relocation to Massachusetts, he joined the all-Black Albion Cycling Club in 1895 and trained at the Worcester YMCA

YMCA, sometimes regionally called the Y, is a worldwide youth organisation based in Geneva, Switzerland, with more than 64 million beneficiaries in 120 countries. It has nearly 90,000 staff, some 920,000 volunteers and 12,000 branches w ...

. Taylor is first mentioned in ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' on September 26, 1895, as a competitor in the Citizen Handicap event, a ten-mile race on Ocean Parkway in Brooklyn

Brooklyn is a Boroughs of New York City, borough of New York City located at the westernmost end of Long Island in the New York (state), State of New York. Formerly an independent city, the borough is coextensive with Kings County, one of twelv ...

, New York. Taylor raced with a 1:30 handicap in a field of 200 competitors that included nine scratch riders.

In 1896, Taylor entered numerous races in the Northeastern states of Massachusetts, New Jersey

New Jersey is a U.S. state, state located in both the Mid-Atlantic States, Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern United States, Northeastern regions of the United States. Located at the geographic hub of the urban area, heavily urbanized Northeas ...

, and Connecticut

Connecticut ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Rhode Island to the east, Massachusetts to the north, New York (state), New York to the west, and Long Island Sound to the south. ...

. After winning a ten-mile road race in Worcester, Taylor competed in the Irvington–Millburn race in New Jersey, also known as the Derby of the East. Within half a mile () of the finish line, someone startled Taylor by tossing ice water into his face and he finished in 23rd place. Taylor's first major East Coast race was in a League of American Wheelmen (LAW) one-mile contest in New Haven

New Haven is a city of the U.S. state of Connecticut. It is located on New Haven Harbor on the northern shore of Long Island Sound. With a population of 135,081 as determined by the 2020 U.S. census, New Haven is the third largest city in Co ...

, Connecticut, where he started in last place but won the event. In August 1896, Taylor made a trip to Indianapolis, where he set an unofficial new track record of 2:11 for a distance of one mile at the Capital City velodrome

A velodrome is an arena for track cycling. Modern velodromes feature steeply banked oval tracks, consisting of two 180-degree circular bends connected by two straights. The straights transition to the circular turn through a moderate easement ...

, beating Walter Sanger's official track record of 2:19 . (Taylor was not allowed to compete with Sanger, a professional racer, in a head-to-head contest because he was still an amateur.) Taylor's final amateur race took place on November 26, 1896, in the 25-mile Tatum Handicap at Jamaica

Jamaica is an island country in the Caribbean Sea and the West Indies. At , it is the third-largest island—after Cuba and Hispaniola—of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean. Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, west of Hispaniola (the is ...

, New York. Taylor finished the race in 14th place.

Professional career

1896: First races

Taylor turned professional in 1896, at the age of eighteen, and soon emerged as the "most formidable racer in America." Taylor's first professional race took place in front of 5,000 spectators on December 5, 1896. He competed in a half-mile handicap event on an indoor track atNew York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

's Madison Square Garden II on the opening day of a multi-day event. Although the main event was a six-day race from December 6–12, other contests in shorter distances were held on December 5 to entertain the crowd. These races included the half-mile handicap for professionals in which Taylor competed, a half-mile race between Jay Eaton and Teddy Goodman, and a half-mile scratch race. In addition, there were half-mile scratch and handicap races for amateurs.

On December 5, Taylor began the half-mile handicap race with a advantage over the scratch racers. He beat a field of competitors that included Tom Cooper, Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

's A.C. Meixwell, and scratch rider Eddie C. Bald, who represented New York's Syracuse, and rode a Barnes bicycle. Taylor won the race riding Munger's "Birdie Special" bicycle and beat Bald by in a sprint to the finish.

From December 6–12, 1896, Taylor participated as one of 28 competitors in the six-day event. Although Taylor had just become a professional, he had achieved enough notoriety, possibly because of his stunning win on December 5, to be listed among the "American contestants" that also included A.A. Hansen (the Minneapolis "rainmaker") and Teddy Goodman. In addition, many "experts from abroad" participated in the meet such as Switzerland's Albert Schock, Germany's Frank J. Waller, Frank Forster, and Ed von Hoeg, and Canada's Burns W. Pierce. Several countries, including Scotland, Wales, France, England, and Denmark, were represented in the event.

As the fascination with six-day races spread from its origins in the United Kingdom across the Atlantic, their appeal to base instincts was attracting large crowds. The more spectators who paid at the gate, the bigger the prizes, which provided riders with the incentive to stay awake–or be kept awake–in order to ride the greatest distance. To prepare for the event, Taylor went to Brooklyn, where he became a member of the South Brooklyn Wheelmen. An estimated crowd of 6,000 spectators attended the final day of the Madison Square Garden races in December 1896. During these long, grueling races, riders suffered delusions and hallucinations, which may have been caused by exhaustion, lack of sleep, or perhaps use of drugs.

Madison Square Garden's six-day event in 1896 was the longest race Taylor had ever entered. On the final day of the long-distance competition, he refused to continue racing, exhausted from physical exertion and lack of sleep; a ''Bearnings'' reporter overheard him comment: "I cannot go on with safety, for there is a man chasing me around the ring with a knife in his hand." Nonetheless, Taylor completed a total of in 142 hours of racing to finish in eighth place. Teddy Hale, the race winner, completed and took home $5,000 in prize money. Taylor never competed in another race that long.

After Taylor's move to the East Coast in 1896, he initially lived in Worcester, where he worked for Munger, and in Middletown, the site of another of Munger's cycle factories. Taylor also lived in other eastern cities, such as South Brooklyn, where he once had trained, but it is not known how long he still resided in New York after he became a professional racer.

1897–1898: Fame and records

Taylor initially raced for Munger's Worcester Cycle Manufacturing Company. After the company went into receivership in 1897 he joined other racing teams. 1897 was the first full year in which Taylor competed on the professional racing circuit. Early in the season, at the Bostonian Cycle Club's "Blue Ribbon Meet" on May 19, 1897, Taylor rode a Comet bicycle to win first place in the one-mile open professional race. On June 26, he won a quarter-mile () race at the track at Manhattan Beach, Brooklyn. Taylor also beat Eddie Bald in a one-mile race in

Taylor initially raced for Munger's Worcester Cycle Manufacturing Company. After the company went into receivership in 1897 he joined other racing teams. 1897 was the first full year in which Taylor competed on the professional racing circuit. Early in the season, at the Bostonian Cycle Club's "Blue Ribbon Meet" on May 19, 1897, Taylor rode a Comet bicycle to win first place in the one-mile open professional race. On June 26, he won a quarter-mile () race at the track at Manhattan Beach, Brooklyn. Taylor also beat Eddie Bald in a one-mile race in Reading, Pennsylvania

Reading ( ; ) is a city in Berks County, Pennsylvania, United States, and its county seat. The city had a population of 95,112 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census and is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, fourth-most populous ...

, but finished fourth in the prestigious LAW convention in Philadelphia.

As a professional racer, Taylor continued to experience racial prejudice as a black cyclist in a white-dominated sport. In November and December 1897, when the circuit extended to the racially-segregated South, local race promoters refused to let Taylor compete because he was black. Taylor returned to Massachusetts for the remainder of the season and Eddie Bald became the American sprint champion in 1897. Despite the obstacles, Taylor was determined to race.

Yet, in the early years of his professional racing career, as he competed in and won more races, Taylor's reputation continued to increase. Newspapers began referring to him as the "Worcester Whirlwind," the "Black Cyclone," the "Ebony Flyer," the "Colored Cyclone," and the "Black Zimmerman," among other nicknames. He also gained popularity among the spectators. One of his fans was President Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

, who kept track of Taylor throughout Taylor's seventeen-year racing career.

Early in the 1898 racing season Taylor beat Bald at Manhattan Beach, Brooklyn,, NY. On June 17th at the Charles River Track in

Early in the 1898 racing season Taylor beat Bald at Manhattan Beach, Brooklyn,, NY. On June 17th at the Charles River Track in Cambridge, Massachusetts

Cambridge ( ) is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States. It is a suburb in the Greater Boston metropolitan area, located directly across the Charles River from Boston. The city's population as of the 2020 United States census, ...

, in a fast paced race, he lost to Eddie McDuffie, both of whom were on the same team and racing Orient Bicycles manufactured by the Waltham Manuracturing Company. One bicycle model and iinnovation that company owner Charles Metz developed was nicknamed the "Major Taylor," which featured a drop-down handlebar, a bar extension and a smaller wheel.

On July 17 at Philadelphia, Taylor won his biggest victories of the season: first place in the one-mile championship and second place in the one-mile handicap races. On August 27, in a head-to-head race with Jimmy Michael of Wales, Taylor set a new world record of 1:41 for a one-mile paced match and beat the Welsh racer to the finish by .

Taylor was among several top cyclists who could claim the national championship in 1898; however, scoring variations and the formation of a new cycling league that year "clouded" his claim to the title. Early in the year a group of professional racers that included Taylor had left the LAW to join a rival group, the American Racing Cyclists' Union (ARCU), and its professional racing group, the National Cycling Association (NCA). During the ARCU sprint championship in St. Louis

St. Louis ( , sometimes referred to as St. Louis City, Saint Louis or STL) is an independent city in the U.S. state of Missouri. It lies near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a populatio ...

and Cape Girardeau, Missouri

Cape Girardeau ( , ; colloquially referred to as "Cape") is a city in Cape Girardeau County, Missouri, Cape Girardeau and Scott County, Missouri, Scott Counties in the U.S. state of Missouri. At the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the ...

, Taylor, who was a devout Baptist

Baptists are a Christian denomination, denomination within Protestant Christianity distinguished by baptizing only professing Christian believers (believer's baptism) and doing so by complete Immersion baptism, immersion. Baptist churches ge ...

, refused to compete for religious reasons in the finals of the championship races because they were held on a Sunday. As a result of Taylor's decision not to race in the finals at Cape Girardeau, the ARCU suspended him from membership. Taylor petitioned the LAW for reinstatement in 1898 and was accepted, but Tom Butler, who had remained a LAW member after the break-up, was declared the League's champion that year.

During 1898–99, at the peak of his cycling career, Taylor established seven world records; the quarter-mile, the one-third-mile (), the half-mile, the two-thirds-mile (), the three-quarters-mile (), the one-mile, and the two-mile () distances. His one-mile world record of 1:41 from a standing start stood for 28 years.

1899: World sprint champion

At the 1899 world championships inMontreal

Montreal is the List of towns in Quebec, largest city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Quebec, the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-largest in Canada, and the List of North American cit ...

, Canada, Major Taylor won the one-mile sprint, to become the first African American

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from an ...

to win a world championship in cycling. He was the second black athlete, after Canadian bantamweight boxer George Dixon of Boston

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

, to win a world championship in any sport. For decades he was the only black athlete to be a world champion in cycling. Taylor won the one-mile world championship sprint in a close finish a few feet ahead of Frenchman Courbe d'Outrelon and American Tom Butler. In addition, Taylor placed second in the two-mile championship sprint at Montreal behind Charles McCarthy and won the half-mile championship race. Because the finals were held on Sundays, when Taylor refused to compete for religious reasons, he did not compete in another world championship contest until 1909 in Copenhagen

Copenhagen ( ) is the capital and most populous city of Denmark, with a population of 1.4 million in the Urban area of Copenhagen, urban area. The city is situated on the islands of Zealand and Amager, separated from Malmö, Sweden, by the ...

, Denmark. Taylor lost in a preliminary heat at Copenhagen and did not compete in the finals.

After Major Taylor's 1899 world championship win, many claimed that the event "had been a farce, because Taylor had not competed against the strongest riders." World cycling's governing body, the International Cycling Association The International Cycling Association (ICA) was the first international body for cycle racing. Founded by Henry Sturmey in 1892 to establish a common definition of amateurism and to organise world championships its role was taken over by the Unio ...

(replaced with the Union Cycliste Internationale

The Union Cycliste Internationale (; UCI; ) is the world governing body for sports cycling and oversees international competitive cycling events. The UCI is based in Aigle, Switzerland.

The UCI issues racing licenses to riders and enforces di ...

(UCI) in 1900), did not allow NCA racers to compete at the world championships in Montreal. As a result, Taylor's accomplishments were somewhat diminished. Because the rival organizations (LAW and the NCA) would not recognize each other, two American champions were crowned in 1899. Tom Cooper was the NCA champion and Taylor was the LAW champion.

In addition to the world championship wins in the one-mile and two-mile distances at Montreal and the LAW Championship, which he won on points, Taylor's victories in 1899 included twenty-two first-place finishes in major championship races around the U.S. Taylor's record-setting times were impossible to dismiss. No other rider had matched the "range and variety" of his winning performances, which made him an international celebrity. In 1899, Taylor made several unsuccessful attempts to recapture his world record for a one-mile paced distance in two "strenuous record-breaking campaigns," before he finally achieved the new world record of 1:19 in November to regain the title of "the fastest man in the world."

For the 1899 racing season, Major Taylor went to Syracuse and with Munger's assistance he signed a contract to race for the E. C. Stearns Company. Taylor, Munger, and Harry Sager, who was Taylor's bicycle parts sponsor, initially planned to negotiate a deal with the Olive Wheel Company; however, the men were able to work out a more lucrative contract with Stearns, who agreed to build Taylor's bicycles using a chainless gear mechanism that Sanger had designed. The bicycles only weighed about and had an gear for sprinting and a gear for longer, paced runs. Stearns "also agreed to build Taylor a revolutionary steam-powered pacing tandem

Tandem, or in tandem, is an arrangement in which two or more animals, machines, or people are lined up one behind another, all facing in the same direction. ''Tandem'' can also be used more generally to refer to any group of persons or objects w ...

, behind which he could attack world records and challenge the leading exponents of paced racing." Although the tandem was temperamental, it helped Taylor break his former teammate and competitor Eddie McDuffie's one-mile world record on November 15, 1899, with a time of 1:19 at a speed of . In late 1899, Taylor signed a contract to race with the Iver Johnson's Arms & Cycle Works team of Fitchburg, Massachusetts

Fitchburg is a city in northern Worcester County, Massachusetts, United States. The third-largest city in the county, its population was 41,946 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. Fitchburg State University is located here.

History

...

, during the 1900 racing season.

1900: American sprint champion

In 1900, when the LAW no longer governed professional bicycle races in the U.S., Taylor's future as a professional racer was in jeopardy. Fortunately, the ARCU and the NCA, who had banned Taylor from competing in their leagues, readmitted him after payment of a $500 fine. Taylor won the American sprint championship on points in 1900. He also beat Tom Cooper, the 1899 NCA champion, in a head-to-head match in a one-mile race at Madison Square Garden in front of 50,000 to 60,000 spectators. In addition, Taylor set world records in the half-mile and two-thirds-mile sprints and raced indoors using a "home trainer" in head-to-head competitions with other riders as a vaudeville act. Taylor eventually settled in Worcester, where, in 1900, he purchased a home on Hobson Street.1901–1904: Europe and Australia

Following his record-setting successes in the U.S. and Canada, Taylor agreed to a European tour. In 1901, Taylor made his first trip to Europe, but returned to compete in the U.S. after the conclusion of the European spring racing season. During his European tour Taylor still refused to race on Sundays, when most of the finals were held, because of his religious convictions. It was reported that Taylor took a

Following his record-setting successes in the U.S. and Canada, Taylor agreed to a European tour. In 1901, Taylor made his first trip to Europe, but returned to compete in the U.S. after the conclusion of the European spring racing season. During his European tour Taylor still refused to race on Sundays, when most of the finals were held, because of his religious convictions. It was reported that Taylor took a Bible

The Bible is a collection of religious texts that are central to Christianity and Judaism, and esteemed in other Abrahamic religions such as Islam. The Bible is an anthology (a compilation of texts of a variety of forms) originally writt ...

with him when he travelled and began each race with a silent prayer because of his religious beliefs.

]

Taylor was popular among the European race fans and news reporters: "Everywhere he went he was mobbed, talked about, or written up." In 1901, Taylor won 18 of the 24 European races he entered, notching up 42 victories when the individual heats are counted. A highlight of Taylor's European tour in 1901 was the two match races with French champion Edmond Jacquelin at the

]

Taylor was popular among the European race fans and news reporters: "Everywhere he went he was mobbed, talked about, or written up." In 1901, Taylor won 18 of the 24 European races he entered, notching up 42 victories when the individual heats are counted. A highlight of Taylor's European tour in 1901 was the two match races with French champion Edmond Jacquelin at the Parc des Princes

The Parc des Princes (, ) is an all-seater stadium, all-seater football stadium in Paris, France. It is located in the south-west of the French capital, inside the 16th arrondissement of Paris, 16th arrondissement, near the Stade Jean-Bouin (P ...

in Paris, the winner in each decided over the best of three heats. Jacquelin won the first match, on May 16, two heats to nil, a wheel length sealing the win in the first heat, two lengths the gap in the second. Taylor triumphed in the second match, on May 27, two heats to nil, four lengths his margin of victory in the first heat, three the gap in the second.

Major Taylor also participated in a European tour in 1902, when he entered 57 races and won 40 of them to defeat the champions of Germany, England, and France. In addition to racing in Europe, Taylor also competed in Australia and New Zealand in 1903 and 1904. In February 1903, for example, Taylor, lured by a £1,200 appearance fee and a world record 1st prize of £750, competed in the inaugural Sydney Thousand handicap. His fee the next year hit £2,000. During his world tour in 1903, Taylor earned prize money estimated at $35,000 ($ in 2015 chained dollars).

1907–1910: Later years

Following a collapse from the mental and physical strain of professional competition, Taylor took a -year hiatus from cycling between 1904 and 1906, before returning to race in France. He set two world records in Paris in 1907 for the half-mile standing start at 0:42 and the quarter-mile standing start at 0:25 . Taylor also returned to Europe for the racing season in 1908 and in 1909. He finally broke his long-standing decision to avoid Sunday races in 1909 when he was nearing the end of his racing career. Taylor's last professional race took place on October 10, 1909, in Roanne, France, in a match race against French world champion Charles Dupré. Taylor won the race, but he did not return to Europe for the 1910 season and retired from competitive cycling. Taylor was still breaking records in 1908, but his age was starting to "creep up on him." He retired from racing in 1910 at the age of 32. When Taylor returned to his home in Worcester at the end of his racing career, his estimated net worth was $75,000 ($ in 2015 chained dollars) to $100,000 ($ in 2015 chained dollars). Taylor won his final competition, an "old-timers race" among former professional racers, in New Jersey in September 1917.Racism in cycling

As Taylor gained fame as an amateur then as a professional, he did not escape racial segregation. In 1894, the League of American Wheelmen changed its bylaws to exclude blacks from membership; however, it did permit them to compete in its races. Although Taylor's cycling was greatly celebrated abroad, particularly in France, his career was still restricted byracism

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one Race (human categorization), race or ethnicity over another. It may also me ...

, particularly in the Southern U.S., where some local promoters would not permit him to compete against white cyclists. Some restaurants and hotels also refused to serve him or provide him lodging.

Taylor asserted in his autobiography that prominent bicycle racers of his era often cooperated to defeat him; the Butler brothers ( Nat and Tom), for example, were accused of so doing in the one-mile world championship race at Montreal in 1899. At the LAW races in Boston, shortly after Taylor had won the world championship, he accused the entire field, that included Tom Cooper and Eddie Bald among others, of fouling him. Taylor complained after the event that he had been "bumped, jostled, and elbowed until I was sorely tried." Racing promoter William A. Brady, who was also Taylor's manager, chastised the other riders for their "rough treatment" of Taylor during the race.

While some of Taylor's fellow racers refused to compete with him, others resorted to intimidation, verbal insults, and threats to physically harm him. While racing in Savannah, Georgia

Savannah ( ) is the oldest city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia and the county seat of Chatham County, Georgia, Chatham County. Established in 1733 on the Savannah River, the city of Savannah became the Kingdom of Great Brita ...

in the Winter of 1898, he received a written threat saying "Clear out if you value your life;" the previous day, Taylor had challenged three riders together to a race after one of them had said they "didn't pace niggers." Taylor recalled that ice water had been thrown at him during races and nails were scattered in front of his wheels. Taylor further stated in his autobiography that he had been elbowed and "pocketed" (boxed in) by other riders to prevent him from sprinting to the front of the pack, a tactic at which he was so successful.

Taylor's competitors also tried to injure him. One incident occurred on September 23, 1897 after the one-mile Massachusetts Open race at Taunton. At the conclusion of the race, William Becker, who placed third behind Taylor in second place, tackled Taylor on the race track and choked him into unconsciousness. Becker, who claimed that Taylor had crowded him during the race, was temporarily suspended while the incident was investigated. Becker received a $50 fine as punishment for his actions but was reinstated and allowed to continue racing. In another incident, which occurred in February 1904 when Taylor was competing in Australia, he was seriously injured on the final turn of a race when his fellow competitor Iver Lawson veered his bicycle toward him and collided with his front wheel. Taylor crashed and lay unconscious on the track before he was taken to a local hospital; he later made a full recovery. Lawson, as a result of his actions, was suspended from racing anywhere in the world for a year.

Taylor explained that he included details of these incidents in his autobiography, along with his comments about his experiences, to serve as an inspiration for other African American athletes trying to overcome racial prejudice and discriminatory treatment in sports. Taylor cited exhaustion as well as the physical and mental strain caused by the racial prejudice he experienced on and off the track as his reasons for retiring from competitive cycling in 1910. His advice to African American youths wishing to emulate him straightforward was that although bicycle racing had been the appropriate route to success for him, he would not recommend it in general. He suggested that individuals "practice clean living, fair play and good sportsmanship" and develop their best talent with a strong character, significant willpower, and "physical courage." Despite many obstacles, Taylor rose to the top of his sport and became "one of the dominant athletes of his era."

Retirement and death

After retiring from competition, Major Taylor applied toWorcester Polytechnic Institute

The Worcester Polytechnic Institute (WPI) is a Private university, private research university in Worcester, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1865, WPI was one of the United States' first engineering and technology universities and now h ...

to study engineering although he did not have a high school diploma, but he was denied admission and took up various business ventures.

Nearly 20 years after his retirement, Taylor wrote and self-published his autobiography, ''The Fastest Bicycle Rider in the World: The Story of a Colored Boy's Indomitable Courage and Success Against Great Odds: An Autobiography'' (1928). According to his book, Taylor was upbeat about his retirement: "I felt I had my day, and a wonderful day it was too." Taylor also claimed he had no regrets and "no animosity toward any man," but his autobiography included hints of bitterness in regard to his treatment as a competitor: "I always played the game fairly and tried my hardest, although I was not always given a square deal or anything like it."

By 1930, Taylor had experienced severe financial difficulties from bad investments (including self-publishing his autobiography), the stock market crash

A stock market crash is a sudden dramatic decline of stock prices across a major cross-section of a stock market, resulting in a significant loss of paper wealth. Crashes are driven by panic selling and underlying economic factors. They often fol ...

, and businesses that proved unsuccessful. Taylor's home in Worcester and some of the family's personal property were sold to pay off debts. He also suffered from persistent ill health in his later years.

Little is known of Taylor's life after the failure of his marriage and his move to Chicago around 1930. Taylor spent the final two years of his life in poverty, selling copies of his autobiography to earn a meagre income and residing at YMCA Hotel in Chicago's Bronzeville neighborhood.

In March 1932, Taylor suffered a heart attack and was hospitalized in the Provident Hospital. After an unsuccessful heart operation, he was moved to Cook County Hospital

The John H. Stroger Jr. Hospital of Cook County (shortened ''Stroger Hospital'', formerly Cook County Hospital) is a public hospital in Chicago, Illinois, United States. It is part of Cook County Health, along with Provident Hospital of Cook Cou ...

's charity ward in April, where he died on June 21, at age 53. The official cause on his death certificate is " nephrosclerosis and hypertension

Hypertension, also known as high blood pressure, is a Chronic condition, long-term Disease, medical condition in which the blood pressure in the artery, arteries is persistently elevated. High blood pressure usually does not cause symptoms i ...

," contributed by "Chronic myocarditis

Myocarditis is inflammation of the cardiac muscle. Myocarditis can progress to inflammatory cardiomyopathy when there is associated ventricular remodeling and cardiac dysfunction due to chronic inflammation. Symptoms can include shortness of bre ...

." His wife and daughter, who survived him, did not immediately learn of his death and no one claimed his remains. He was initially buried at Mount Glenwood Cemetery in Thornton Township, Cook County, near Chicago, in an unmarked pauper's grave. In 1948, a group of former professional bicycle racers used funds donated by Frank W. Schwinn, owner of the Schwinn Bicycle Co. at that time, to organize the exhumation and reburial of Taylor's remains in a more prominent location at the cemetery. The plaque at the grave reads: "World's champion bicycle racer who came up the hard way without hatred in his heart, an honest, courageous and God-fearing, clean-living gentlemanly athlete. A credit to his race who always gave out his best. Gone but not forgotten."

Legacy

Major Taylor's legacy lies in his willingness to challenge racial prejudice as an African American athlete in the white-dominated sport of cycling. He was also hailed as a sports hero in France and Australia. Taylor, who became a role model for other athletes facing racial prejudice and discrimination, was "the first great black celebrity athlete" and a pioneer in his efforts to challenge segregation in sports. He also paved the way for others facing similar circumstances. Taylor explained in his autobiography that he had no other African Americans to offer him advice and "therefore had to blaze my own trail." An image by Kadir Nelson of Major Taylor racing down a tree-lined street with bicyclists from the past and the present trying to keep up behind him was the illustrated cover and cover story of the " New Yorker" magazine online edition of May 26, 2025 and print edition of June 2, 2025.Honors and tributes

Taylor's legacy remained largely unknown until 1982, when the Major Taylor Velodrome in Indianapolis opened for the city's hosting of the U.S. Olympic Festival. Annual events taking place in the velodrome or the wideIndy Cycloplex

include the Major Taylor Racing League track series, and from 2015, the Major Taylor Cross Cup second division UCI

cyclo-cross

Cyclo-cross (cyclocross, CX, cyclo-X or cross) is a form of bicycle racing. Races typically take place in the autumn and winter (the international or "World Cup" season is October–February), and consist of many laps of a short (2.5–3.5&nb ...

event. Taylor was posthumously inducted into the U.S. Bicycling Hall of Fame in 1989. In 1996 and 1997, Taylor was posthumously awarded with the USA Cycling Korbel Lifetime Achievement Award and the Massachusetts Hall of Black Achievement, respectively. In 2002, he was one of the nine track cyclists inducted into the UCI Hall of Fame, created to commemorate 100 years of the Paris–Roubaix

Paris–Roubaix is a one-day professional bicycle road race in northern France, starting north of Paris and finishing in Roubaix, at the border with Belgium. It is one of cycling's oldest races, and is one of the 'Cycling monument, Monuments' ...

one-day road race and the inauguration of the World Cycling Centre. In 2003, he was named a Sports Ethics Fellow by the Institute for International Sport. During the 2005 UCI Track Cycling World Championships in Los Angeles, a Peugeot bicycle that Taylor had owned and then was donated to the U.S. Bicycling Hall of Fame, was put on display inside the ADT Event Center. In 2009, a state historical marker was installed as a tribute to Taylor near the Indiana State Fairgrounds in Indianapolis, where the Capital City track once stood, and where he had set an unofficial track record in 1896. In 2018, he was honored with a special tribute award at the International Athletic Association's Jesse Owens Awards held at the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

In 1998, in Taylor's adopted hometown of Worcester, MA, where he had lived for 35 years, thMajor Taylor Association

was formed by locals with the goal of erecting a permanent memorial to Taylor outside the Worcester Public Library and telling his story. On July 24, 2006, the city renamed the Worcester Center Boulevard, a high-traffic downtown street, to Major Taylor Boulevard. At the same time, funding for the memorial was secured with the Massachusetts Legislature approving $205,000, signed by governor

Mitt Romney

Willard Mitt Romney (born March 12, 1947) is an American businessman and retired politician. He served as a United States Senate, United States senator from Utah from 2019 to 2025 and as the 70th governor of Massachusetts from 2003 to 2007 ...

. The opening ceremony took place on May 21, 2008, attended by Tour de France

The Tour de France () is an annual men's multiple-stage cycle sport, bicycle race held primarily in France. It is the oldest and most prestigious of the three Grand Tour (cycling), Grand Tours, which include the Giro d'Italia and the Vuelta a ...

winner Greg LeMond

Gregory James LeMond (born June 26, 1961) is an American former Road bicycle racing, road racing cyclist. He won the Tour de France thrice and the UCI Road World Championships – Men's road race, Road Race World Championship twice, becoming t ...

. The memorial features a bronze sculpture

Bronze is the most popular metal for Casting (metalworking), cast metal sculptures; a cast bronze sculpture is often called simply "a bronze". It can be used for statues, singly or in groups, reliefs, and small statuettes and figurines, as w ...

of Taylor surrounded by granite

Granite ( ) is a coarse-grained (phanerite, phaneritic) intrusive rock, intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly coo ...

, created by Antonio Tobias Mendez, who was chosen from more than 60 others. At the grand opening of Worcester's Applebee's restaurant in 2000, Taylor was selected as its "hometown hero" and has a display of his memorabilia. In 2002, the Educational Association of Worcester and the Worcester Public Schools, together with the Major Taylor Association, developed a curriculum

In education, a curriculum (; : curriculums or curricula ) is the totality of student experiences that occur in an educational process. The term often refers specifically to a planned sequence of instruction, or to a view of the student's experi ...

guide on Taylor, which has since been expanded and used in schools nationwide. Since 2003, Worcester has hosted the annual "George Street Bike Challenge for Major Taylor" amateur hillclimb event.

In 1979, the first of what came to be numerous cycling clubs across the country named in Taylor's honor was organized in Columbus, Ohio. In 2008, a number of these clubs joined with other African-American clubs to form thNational Brotherhood of Cyclists

(NBC), a nonprofit organization that aims to further diversity in cycling. The Major Taylor Trail, a

rail trail

A rail trail or railway walk is a shared-use path on a Right of way#Rail right of way, railway right of way. Rail trails are typically constructed after a railway has been abandoned and the track has been removed but may also share the rail corr ...

that navigates through South Side, Chicago, opened in 2007. Eleven years later, Chicagoan artist Bernard Williams oversaw the creation of a community mural honoring Taylor along the metal siding of the Little Calumet River

The Calumet River is a system of industrialized rivers and canals in the region between the South Side, Chicago, south side of Chicago, Illinois, and the city of Gary, Indiana. Historically, the Little Calumet River and the Grand Calumet River ...

bridge, which the trail crosses. Taylor is also celebrated along the Alum Creek Greenway Trail in Columbus, Ohio

Columbus (, ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of cities in Ohio, most populous city of the U.S. state of Ohio. With a 2020 United States census, 2020 census population of 905,748, it is the List of United States ...

. In 2009, the Cascade Bicycle Club community organization of Washington state launched The Major Taylor Project, a youth cycling program.

A small museum devoted to Taylor opened in 2021 in the former Worcester County Courthouse. Taylor's great-granddaughter attended the dedication.

A mural was dedicated in Indianapolis, in September 2021, to honor his legacy.

The Charles River Museum of Industry and Innovation, in Waltham, MA, has several displays dedicated to Major Taylor and his rivalry with Eddie McDuffee, both of whom rode Orient Bicycles, manufactured by the Metz

Metz ( , , , then ) is a city in northeast France located at the confluence of the Moselle (river), Moselle and the Seille (Moselle), Seille rivers. Metz is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Moselle (department), Moselle Departments ...

Waltham Manufacturing Company.

In Dec. 2023, U.S. Rep. Jim Baird of Indiana, (R) and U.S. Rep. Jonathan L. Jackson of Illinois, (D), spearheaded an effort to award the Congressional Gold Medal to Taylor. The measure was, co-sponsored by U.S. Rep. James P. McGovern, D-Worcester. (Status of that unknown.)

In popular culture

Actor Philip Morris portrayed Taylor in the 1992 television mini-series '' Tracks of Glory''. Blues musician Otis Taylor (no relation) recorded "He Never Raced on Sunday," a song about Taylor for his 2004 album ''Double V''. In 2007, Nike produced the Major Taylor "premium" collection of their most iconicsneakers

Sneakers (American English, US) or trainers (British English, UK), also known by a #Names, wide variety of other names, are shoes primarily designed for sports or other forms of physical exercise, but are also widely used for everyday casual ...

in a light brown/neon yellow/white colorway. In the same year, SOMA Fabrications began making a set of bicycle handlebar

A bicycle handlebar is the steering control for bicycles. It is the equivalent of a tiller for vehicles and vessels, as it is most often directly mechanically linked to a pivoting front wheel via a Stem (bike), stem which in turn attaches it to ...

s called the Major Taylor Bar, which is a replica of 1930s drop handlebar that was named for Taylor. Dewshane Williams portrayed Taylor in the 2013 episode of television drama series ''Murdoch Mysteries

''Murdoch Mysteries'' is a Canadian television drama series that premiered on Citytv on January 20, 2008, and currently airs on CBC. The series is based on characters from the ''Detective Murdoch'' novels by Maureen Jennings and stars Yannick ...

'', "Tour de Murdoch."

On April 12, 2018, at a private exhibition in The Times Center in New York City, cognac brand Hennessy announced that Taylor would become the subject of the company's fifth instalment of their "Wild Rabbit" advertising campaign

An advertising campaign or marketing campaign is a series of advertisement messages that share a single idea and theme which make up an integrated marketing communication (IMC). An IMC is a platform in which a group of people can group their ide ...

, created with agency Droga5, which through a series of partnerships tells inspirational the stories of culturally influential people, with the slogan "Never stop. Never settle." The event included the unveiling some of the partnerships including Kadir Nelson's bronze sculpture

Bronze is the most popular metal for Casting (metalworking), cast metal sculptures; a cast bronze sculpture is often called simply "a bronze". It can be used for statues, singly or in groups, reliefs, and small statuettes and figurines, as w ...

of Taylor, ''The Major''. The campaign launched to the public with a television commercial during the 2018 NBA Finals in April. The ''Major'' directed by Derek Cianfrance

Derek M. Cianfrance (; born January 23, 1974) is an American film director, cinematographer, screenwriter, and editor. He is best known for writing and directing the films ''Blue Valentine (film), Blue Valentine'' (2010), ''The Place Beyond the P ...

, which has cuts in various lengths, features a voiceover from rapper Nas

Nas (born 1973) is the stage name of American rapper Nasir Jones.

Nas, NaS, or NAS may also refer to:

Aviation

* Nasair, a low-cost airline carrier and subsidiary based in Eritrea

* National Air Services, an airline in Saudi Arabia

** Nas Air (S ...

and recreates Taylor racing in an indoor velodrome. The 30-second cut was shown during third and fourth quarters of the Super Bowl LIII in February 2019, Hennessy's first appearance in a Super Bowl commercial. On April 22, 2018, ESPN

ESPN (an initialism of their original name, which was the Entertainment and Sports Programming Network) is an American international basic cable sports channel owned by the Walt Disney Company (80% and operational control) and Hearst Commu ...

premiered the Hennessy-sponsored television documentary short ''The Six Day Race: The Story of Marshall "Major" Taylor''; directed by Colin Barnicle, it features interviews with contemporary African-American athletes, road cyclist Ayesha McGowan and BMX rider Nigel Sylvester.

In 2019, two Taylor-inspired brand collaborations were released, with part of the proceeds going to the NBC. Kerby Jean-Raymond, under his ''haute couture

(; ; French for 'high sewing', 'high dressmaking') is the creation of exclusive custom-fitted high-end fashion design. The term ''haute couture'' generally refers to a specific type of upper garment common in Europe during the 16th to the ...

'' fashion label Pyer Moss, designed a five-piece collection "MMT 140," and Affinity Cycles made limited-run of a modern replica Taylor-era track bicycle

A track bicycle or track bike is a bicycle optimized for racing at a velodrome or outdoor track. Unlike road bicycles, the track bike is a fixed-gear bicycle; thus, it has only a single gear ratio and has neither a freewheel nor brakes. Bicycle t ...

. In partnership with the NBC, a series of tribute bicycle rides took place across the U.S. in November and December marking Taylor's birth date, and the creation of the $25,000 "MMT Higher Education Scholarship", awarded to one winner with the best "Never stop. Never settle." story. Also in 2019, Taylor's name and likeness was licensed to Major Taylor Cycling Wear of Columbus Ohio to manufacture and distribute official sports- and cycling-wear bearing the image of Major Taylor.

Graphic novel

A graphic novel is a self-contained, book-length form of sequential art. The term ''graphic novel'' is often applied broadly, including fiction, non-fiction, and Anthology, anthologized work, though this practice is highly contested by comics sc ...

publisher Drawn and Quarterly planned to publish a biography of Taylor by comic artist Frederick Noland in 2023.

Marriage and family

Taylor's wife, Daisy Victoria Morris, was born on January 28, 1876, in

Taylor's wife, Daisy Victoria Morris, was born on January 28, 1876, in Hudson, New York

Hudson is a Administrative divisions of New York#City, city in and the county seat of Columbia County, New York, United States. At the 2020 United States Census, 2020 census, it had a population of 5,894. On the east side of the Hudson River, f ...

. Taylor married Morris in Ansonia, Connecticut, on March 21, 1902. Taylor met her around 1900 when she was living in Worcester, with her aunt and uncle.

While in Australia in 1904, Taylor and his wife had their only child, a daughter that they named Rita Sydney in honor of Sydney, where she was born on May 11. When Taylor, his wife, and daughter were not traveling, they lived in a large home on Hobson Avenue in Worcester that Taylor had purchased in 1900.

After his retirement from racing in 1910 and the failure of subsequent business ventures in the 1920s, Taylor and his wife became estranged. In 1930 she left him and moved to New York City. Around the same time Taylor left Worcester and moved to Chicago; he never saw his wife or daughter again.

Taylor's daughter Sydney, who graduated from the Sargent School of Culture in Boston

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

in 1925 and the University of Chicago

The University of Chicago (UChicago, Chicago, or UChi) is a Private university, private research university in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Its main campus is in the Hyde Park, Chicago, Hyde Park neighborhood on Chicago's South Side, Chic ...

in 1936, taught physical education at West Virginia State University. She died in 2005 at age 101; her survivors include a son, Dallas C. Brown Jr., and his five children. In 1984, Taylor's daughter Sydney donated an extensive scrapbook collection on her father to the University of Pittsburgh

The University of Pittsburgh (Pitt) is a Commonwealth System of Higher Education, state-related research university in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, United States. The university is composed of seventeen undergraduate and graduate schools and colle ...

Archives. The original scrapbooks were donated to the Indiana State Museum and Historic Sites in 1988.

World records

See also

*List of African-American firsts

African Americans are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, ethnic group in the United States. The first achievements by African Americans in diverse fields have historically marked footholds, often leading to more widespread cultural chan ...

* List of African-American sports firsts

* List of cyclists

* List of former students of the Conservatoire de Paris

* List of Indiana state historical markers in Marion County

* List of people from Indianapolis

* List of people from Worcester, Massachusetts

* Thomas Gascoyne

* Major Taylor Trail

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * (reprinted Ayer, 2004: )Further reading

* * * * * * * * *External links

*The Major Taylor Association

The Major Taylor Society

Major Taylor: Fastest Cyclist in the World

{{DEFAULTSORT:Taylor, Major 1878 births 1932 deaths African-American sportsmen American male cyclists American track cyclists Cyclists from Indiana Sportspeople from Indianapolis Sportspeople from Worcester, Massachusetts UCI Track Cycling World Champions (men) 20th-century African-American sportsmen History of cycling in the United States