Major General John A. Logan on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Major General John A. Logan'', also known as the General John A. Logan Monument and Logan Circle Monument, is an

Logan was elected as a Republican to the U.S. House of Representatives and later to the

Logan was elected as a Republican to the U.S. House of Representatives and later to the

The monument is sited in the center of Logan Circle, a 1.8 acre (0.73 ha) public park and traffic circle in the Logan Circle neighborhood at the convergence of 13th Street,

The monument is sited in the center of Logan Circle, a 1.8 acre (0.73 ha) public park and traffic circle in the Logan Circle neighborhood at the convergence of 13th Street,

equestrian statue

An equestrian statue is a statue of a rider mounted on a horse, from the Latin ''eques'', meaning 'knight', deriving from ''equus'', meaning 'horse'. A statue of a riderless horse is strictly an equine statue. A full-sized equestrian statue is a ...

in Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

, that honors politician and Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

general John A. Logan. The monument is sited in the center of Logan Circle, a traffic circle and public park in the Logan Circle neighborhood. The statue was sculpted by artist Franklin Simmons

Franklin Bachelder Simmons (January 11, 1839 – December 8, 1913) was a prominent American sculptor of the nineteenth century. Three of his statues are in the National Statuary Hall Collection, three of his busts are in the United States Senat ...

, whose other prominent works include the Peace Monument

The Peace Monument, also known as the Navy Monument, Naval Monument or Navy-Peace Monument, stands on the western edge of the United States Capitol Complex in Washington, D.C. It is in the middle of Peace Circle, where First Street and Pennsy ...

and statues in the National Statuary Hall Collection

The National Statuary Hall Collection in the United States Capitol is composed of statues donated by individual states to honor persons notable in their history. Limited to two statues per state, the collection was originally set up in the old Hal ...

. The architect of the statue base was Richard Morris Hunt

Richard Morris Hunt (October 31, 1827 – July 31, 1895) was an American architect of the nineteenth century and an eminent figure in the history of architecture of the United States. He helped shape New York City with his designs for the 1902 ...

, designer of prominent buildings including the Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, colloquially referred to as the Met, is an Encyclopedic museum, encyclopedic art museum in New York City. By floor area, it is the List of largest museums, third-largest museum in the world and the List of larg ...

in New York City and The Breakers

The Breakers is a Gilded Age mansion located at 44 Ochre Point Avenue, Newport, Rhode Island, US. It was built between 1893 and 1895 as a summer residence for Cornelius Vanderbilt II, a member of the wealthy Vanderbilt family.

The 70-room mans ...

in Newport

Newport most commonly refers to:

*Newport, Wales

*Newport, Rhode Island, US

Newport or New Port may also refer to:

Places Asia

*Newport City, Metro Manila, a Philippine district in Pasay

* Newport (Vietnam), a United States Army and Army of t ...

, Rhode Island. Prominent attendees at the dedication ceremony in 1901 included President William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until Assassination of William McKinley, his assassination in 1901. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Repub ...

, members of his cabinet, Senator Chauncey Depew

Chauncey Mitchell Depew (April 23, 1834April 5, 1928) was an American attorney, businessman, and Republican politician. He is best remembered for his two terms as United States Senator from New York and for his work for Cornelius Vanderbilt, a ...

, Senator Shelby Moore Cullom

Shelby Moore Cullom (November 22, 1829 – January 28, 1914) was an American politician who served in the United States House of Representatives, the United States Senate and as the 17th Governor of Illinois. He was Illinois's longest serving s ...

, and General Grenville M. Dodge

Grenville Mellen Dodge (April 12, 1831 – January 3, 1916) was a Union Army officer on the frontier and a pioneering figure in military intelligence during the Civil War, who served as Ulysses S. Grant's intelligence chief in the Western Th ...

.

The sculpture is one of eighteen Civil War monuments in Washington, D.C., which were collectively listed on the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government's official United States National Register of Historic Places listings, list of sites, buildings, structures, Hist ...

in 1978. The bronze sculpture rests on a bronze and granite base adorned with two reliefs depicting historically inaccurate moments in Logan's life. The monument and surrounding park are owned and maintained by the National Park Service

The National Park Service (NPS) is an List of federal agencies in the United States, agency of the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government, within the US Department of the Interior. The service manages all List ...

, a federal agency of the Interior Department

An interior ministry or ministry of the interior (also called ministry of home affairs or ministry of internal affairs) is a government department that is responsible for domestic policy, public security and law enforcement.

In some states, the i ...

.

History

Background

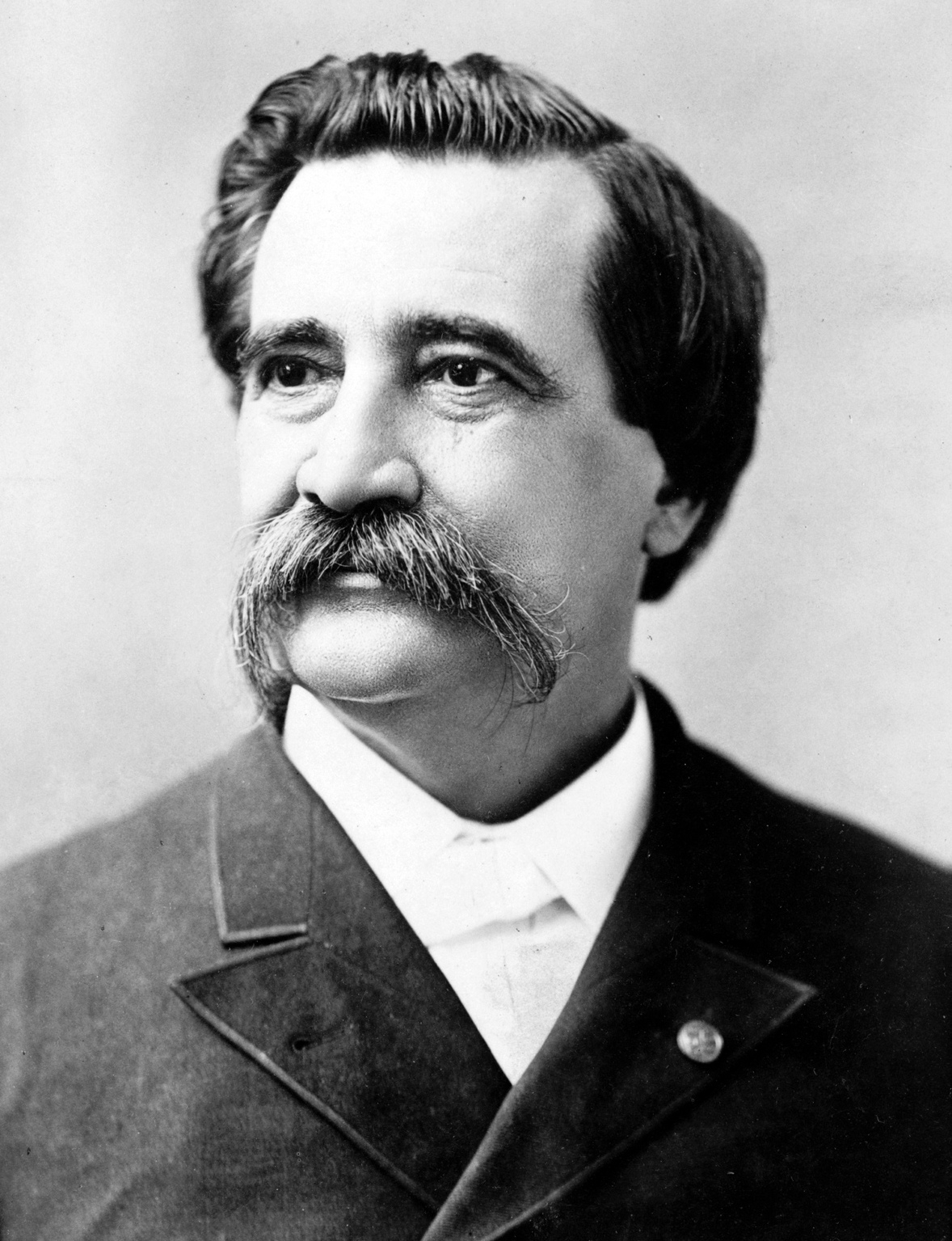

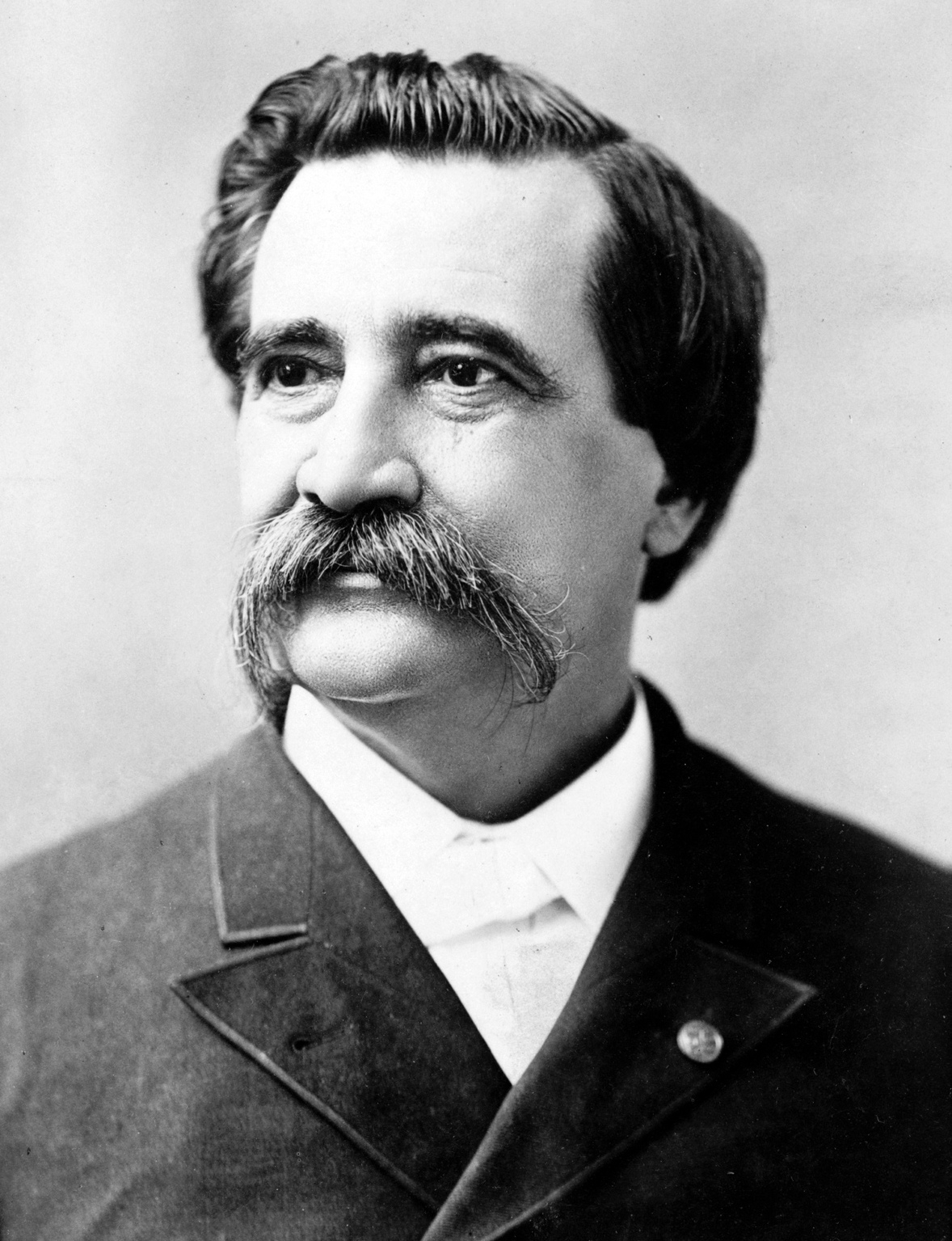

John A. Logan (1826–1886) was a native ofIllinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. It borders on Lake Michigan to its northeast, the Mississippi River to its west, and the Wabash River, Wabash and Ohio River, Ohio rivers to its ...

who served as a second lieutenant in the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War (Spanish language, Spanish: ''guerra de Estados Unidos-México, guerra mexicano-estadounidense''), also known in the United States as the Mexican War, and in Mexico as the United States intervention in Mexico, ...

before studying at the University of Louisville

The University of Louisville (UofL) is a public university, public research university in Louisville, Kentucky, United States. It is part of the Kentucky state university system. Chartered in 1798 as the Jefferson Seminary, it became in the 19t ...

to become a lawyer. Originally a member of the Democratic Party, he was elected state senator and later a member of the U.S. House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives is a chamber of the bicameral United States Congress; it is the lower house, with the U.S. Senate being the upper house. Together, the House and Senate have the authority under Article One of th ...

. During the onset of the Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

, Logan denounced what he considered extremists on both sides, but eventually volunteered to fight with the Union Army during the First Battle of Bull Run

The First Battle of Bull Run, called the Battle of First Manassas

. by Confederate States ...

. He then resigned from Congress and was made colonel after he organized the . by Confederate States ...

31st Illinois Volunteer Infantry Regiment

The 31st Regiment Illinois Volunteer Infantry, nicknamed the "Dirty-First," was an infantry regiment that served in the Union Army during the American Civil War.

Service

The 31st Illinois Infantry was organized at Jacksonville, Illinois and must ...

. Logan was wounded twice while serving in the war and considered an outstanding field commander. He was promoted to brigadier general following the victory at Fort Donelson

Fort Donelson was a fortress built early in 1862 by the Confederacy during the American Civil War to control the Cumberland River, which led to the heart of Tennessee, and thereby the Confederacy. The fort was named after Confederate general Da ...

. Logan played a significant role in the Union success at Vicksburg and served as that district's military governor. Following the death of General James B. McPherson

James Birdseye McPherson (/məkˈfərsən/) (November 14, 1828 – July 22, 1864) was a career United States Army officer who served as a general in the Union Army during the American Civil War. McPherson was on the general staff of Henr ...

, Logan was given command of the Army of the Tennessee

The Army of the Tennessee was a Union Army, Union army in the Western Theater of the American Civil War, named for the Tennessee River. A 2005 study of the army states that it "was present at most of the great battles that became turning points ...

, but was soon relieved by General Oliver O. Howard

Oliver Otis Howard (November 8, 1830 – October 26, 1909) was a career United States Army officer and a Union Army, Union General officer, general in the American Civil War, Civil War. As a brigade commander in the Army of the Potomac, Howard ...

after Logan became too involved with the 1864 presidential election. He left the army in 1865 and resumed his career in politics.

Logan was elected as a Republican to the U.S. House of Representatives and later to the

Logan was elected as a Republican to the U.S. House of Representatives and later to the U.S. Senate

The United States Senate is a chamber of the bicameral United States Congress; it is the upper house, with the U.S. House of Representatives being the lower house. Together, the Senate and House have the authority under Article One of the ...

. In the 1884 presidential election, Logan unsuccessfully ran with Senator James G. Blaine

James Gillespie Blaine (January 31, 1830January 27, 1893) was an American statesman and Republican politician who represented Maine in the United States House of Representatives from 1863 to 1876, serving as speaker of the U.S. House of Rep ...

as his vice presidential candidate, narrowly losing the race. During his time in office, Logan was considered one of the most vocal advocates for military veterans. He helped organize two veteran fraternal organizations, the Grand Army of the Republic

The Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) was a fraternal organization composed of veterans of the Union Army (United States Army), Union Navy (United States Navy, U.S. Navy), and the United States Marine Corps, Marines who served in the American Ci ...

(GAR) and the Society of the Army of the Tennessee (SAT), and was instrumental in the federal government recognizing Memorial Day

Memorial Day (originally known as Decoration Day) is a federal holiday in the United States for mourning the U.S. military personnel who died while serving in the United States Armed Forces. It is observed on the last Monday of May.

It i ...

(originally called Decoration Day) as an official holiday, first celebrated in 1868.

Soon after Logan's death in 1886, the SAT began work on erecting a monument to the military hero. The organization worked closely with the GAR and Logan's widow, Mary, to raise funds and lobby Congress for a monument. It would be the second equestrian monument in Washington, D.C., commissioned by the SAT, the first being the '' Major General James B. McPherson'' statue. Erection of the monument was approved by an act of Congress on March 2, 1889. A memorial commission was created to select a sculptor and site for the statue. Members of the commission asked sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens

Augustus Saint-Gaudens (; March 1, 1848 – August 3, 1907) was an American sculpture, sculptor of the Beaux-Arts architecture, Beaux-Arts generation who embodied the ideals of the American Renaissance. Saint-Gaudens was born in Dublin to an Iris ...

who he would recommend. He suggested Franklin Simmons

Franklin Bachelder Simmons (January 11, 1839 – December 8, 1913) was a prominent American sculptor of the nineteenth century. Three of his statues are in the National Statuary Hall Collection, three of his busts are in the United States Senat ...

(1839–1913), an American artist working in Rome. Simmons had previously sculpted several Civil War monuments, including the Peace Monument

The Peace Monument, also known as the Navy Monument, Naval Monument or Navy-Peace Monument, stands on the western edge of the United States Capitol Complex in Washington, D.C. It is in the middle of Peace Circle, where First Street and Pennsy ...

in Washington, D.C. His other works in the city include several statues in the National Statuary Hall Collection

The National Statuary Hall Collection in the United States Capitol is composed of statues donated by individual states to honor persons notable in their history. Limited to two statues per state, the collection was originally set up in the old Hal ...

and the United States Senate Vice Presidential Bust Collection

The United States Senate Vice Presidential Bust Collection is a series of 46 busts in the United States Capitol, each one bearing the likenesses of a vice president of the United States. Each sculpture, from John Adams to Dick Cheney, honors th ...

.

The commission considered models by several sculptors before selecting Simmons in December 1892, whose model was the "most agreeable to Mrs. Logan." She admired not only the posture of Simmon's model, but his idea to have the statue rest on a bronze base, unlike other monuments in the city that featured granite bases. Mary also liked that Simmons and members of the commission would follow her recommendations for the reliefs

Relief is a sculptural method in which the sculpted pieces remain attached to a solid background of the same material. The term ''relief'' is from the Latin verb , to raise (). To create a sculpture in relief is to give the impression that th ...

to be found on the statue base. Simmons was paid $65,000 for his work; around $13,000 from the SAT and the remainder from the federal government. Sculpting the piece proved more difficult than Simmons had expected since the Logan statue was his first and only equestrian work. He was forced to ask for several extensions beginning in 1896. Simmons paid founder

Founder or Founders may refer to:

Places

*Founders Park, a stadium in South Carolina, formerly known as Carolina Stadium

* Founders Park, a waterside park in Islamorada, Florida

Arts, entertainment, and media

* Founders (''Star Trek''), the ali ...

Fonderia Nelli extra money to work around the clock on the base, designed by prominent architect Richard Morris Hunt

Richard Morris Hunt (October 31, 1827 – July 31, 1895) was an American architect of the nineteenth century and an eminent figure in the history of architecture of the United States. He helped shape New York City with his designs for the 1902 ...

, whose other works include the Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, colloquially referred to as the Met, is an Encyclopedic museum, encyclopedic art museum in New York City. By floor area, it is the List of largest museums, third-largest museum in the world and the List of larg ...

in New York City and The Breakers

The Breakers is a Gilded Age mansion located at 44 Ochre Point Avenue, Newport, Rhode Island, US. It was built between 1893 and 1895 as a summer residence for Cornelius Vanderbilt II, a member of the wealthy Vanderbilt family.

The 70-room mans ...

in Newport

Newport most commonly refers to:

*Newport, Wales

*Newport, Rhode Island, US

Newport or New Port may also refer to:

Places Asia

*Newport City, Metro Manila, a Philippine district in Pasay

* Newport (Vietnam), a United States Army and Army of t ...

Rhode Island.

It only took Nelli three-and-a-half months to complete the process instead of the planned year. The Cranford Paving Company was contracted to prepare the site and lay the granite foundation. Simmons was not pleased with the company's work and new stone was ordered in September 1897. Following the new stone's placement, the base was installed on April 18, 1898. It wasn't until 1900 that Simmons completed the sculpture and it was cast in Rome. Upon its completion, a ceremony attended by King Umberto I

Umberto I (; 14 March 1844 – 29 July 1900) was King of Italy from 9 January 1878 until his assassination in 1900. His reign saw Italy's expansion into the Horn of Africa, as well as the creation of the Triple Alliance among Italy, Germany and ...

of Italy and his wife, Queen Margherita

Margherita of Savoy (''Margherita Maria Teresa Giovanna''; 20 November 1851 – 4 January 1926) was Queen of Italy by marriage to her first cousin King Umberto I of Italy. She was the daughter of Prince Ferdinando of Savoy, Duke of Genoa and ...

, was held at the foundry where Simmons was honored with knighthood. The sculpture was shipped to the United States and arrived in Brooklyn

Brooklyn is a Boroughs of New York City, borough of New York City located at the westernmost end of Long Island in the New York (state), State of New York. Formerly an independent city, the borough is coextensive with Kings County, one of twelv ...

in December 1900. Because the sculpture was too large to be transported by train, it was placed onto a two-masted schooner

A schooner ( ) is a type of sailing ship, sailing vessel defined by its Rig (sailing), rig: fore-and-aft rigged on all of two or more Mast (sailing), masts and, in the case of a two-masted schooner, the foremast generally being shorter than t ...

and arrived in Washington, D.C., on January 16, 1901. It was installed on top of the base one week later.

The site chosen for the monument was the center of Iowa Circle, a park in an upscale neighborhood in the city's northwest

The points of the compass are a set of horizontal, radially arrayed compass directions (or azimuths) used in navigation and cartography. A '' compass rose'' is primarily composed of four cardinal directions—north, east, south, and west— ...

quadrant

Quadrant may refer to:

Companies

* Quadrant Cycle Company, 1899 manufacturers in Britain of the Quadrant motorcar

* Quadrant (motorcycles), one of the earliest British motorcycle manufacturers, established in Birmingham in 1901

* Quadrant Privat ...

. The park was completely redesigned in 1891 to make room for the monument. By the time it was dedicated in 1901, nearby Dupont Circle

Dupont Circle is a historic roundabout park and Neighborhoods in Washington, D.C., neighborhood of Washington, D.C., located in Northwest (Washington, D.C.), Northwest D.C. The Dupont Circle neighborhood is bounded approximately by 16th St ...

was lined with mansions and had become more popular with the city's wealthy residents while Iowa Circle, surrounded by stately row houses, had become a middle-class neighborhood.

Dedication

The monument was formally dedicated on April 9, 1901. Temporary platforms for invited and distinguished guests were built near the base. Guests included PresidentWilliam McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until Assassination of William McKinley, his assassination in 1901. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Repub ...

, members of his cabinet, Senator Chauncey Depew

Chauncey Mitchell Depew (April 23, 1834April 5, 1928) was an American attorney, businessman, and Republican politician. He is best remembered for his two terms as United States Senator from New York and for his work for Cornelius Vanderbilt, a ...

, Senator Shelby Moore Cullom

Shelby Moore Cullom (November 22, 1829 – January 28, 1914) was an American politician who served in the United States House of Representatives, the United States Senate and as the 17th Governor of Illinois. He was Illinois's longest serving s ...

, General Grenville M. Dodge

Grenville Mellen Dodge (April 12, 1831 – January 3, 1916) was a Union Army officer on the frontier and a pioneering figure in military intelligence during the Civil War, who served as Ulysses S. Grant's intelligence chief in the Western Th ...

, Mary Logan and several members of the Logan family, representatives from the GAR and SAT, and Simmons. Prior to the ceremony, there was a large military parade led by Colonel Francis L. Guenther. The parade consisted of soldiers, marines, seamen from the nearby Navy Yard, the District of Columbia militia, and GAR and SAT veterans. Dodge, who was president of the SAT and the only living general depicted on one of the relief panels, presided over the ceremonies. George Tucker, a grandson of Logan, pulled a cord, parting the flags that had draped over the statue. This was followed by cheers and applause from the crowd while the Fourth Artillery fired a national salute.

McKinley, the last Civil War veteran to occupy the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. Located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue Northwest (Washington, D.C.), NW in Washington, D.C., it has served as the residence of every U.S. president ...

, gave an address which included the following remarks: "It is a good token when patriots are honored and patriotism exalted. Monuments which express the nation's gratitude for great deeds inspire great deeds. The statue unveiled today proclaims our country's appreciation of one of her heroic sons whose name is dear to the American people, the ideal volunteer soldier of two wars, the eminent senator and commoner, General John A. Logan." Following the president's speech, Depew also gave an address. His remarks included: "The history of our country is condensed in the Revolutionary and civil wars. As Washington stands out in the first of our crucial contests, so does Lincoln in the second. About Lincoln cluster Grant, Sherman, Sheridan, Logan, McPherson, and a host of other heroes...Among those successful Americans in many lines who have won and held the public eye and died mourned by all their countrymen, there will live in the future in the history of the Republic no nobler figure, in peace and in war, in the pursuits of the citizen, and in work for the welfare of his fellow citizens, than General John A. Logan." Cullom then read a letter from Illinois governor Richard Yates Jr.

Richard Yates Jr. (December 12, 1860 – April 11, 1936) was the 22nd Governor of Illinois from 1901 to 1905—the first native-born governor of the state. From 1919 to 1933, he served in the U.S. House of Representatives from Illinois.

Earl ...

, who was unable to attend, which paid tribute to Logan and noted how proud the state's citizens were of the Illinois native. The ceremony concluded following the benediction by Reverence J. G. Butler.

Reception

Initial reception to the statue was very positive. ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' described it as producing "an impression of dignity, beauty, and power." But in the weeks following the dedication ceremony, praise turned to criticism and reporters noted "absurdities" in the relief panels. They noted that the relief depicting Logan gathered with other Civil War leaders plotting strategy together was very unlikely. The second panel, depicting Logan being sworn in as senator by Vice President Chester A. Arthur

Chester Alan Arthur (October 5, 1829 – November 18, 1886) was the 21st president of the United States, serving from 1881 to 1885. He was a Republican from New York who previously served as the 20th vice president under President James A. ...

was called "impossible" and "ridiculous." Logan was sworn into the Senate in 1879 and Arthur himself was not sworn in as vice president until 1881. Two of the senators depicted in that relief were not sworn in until 1882 and 1884, respectively, and another one died in 1877. Mary Logan initially took credit for selecting the scenes depicted in the reliefs and received all of the blame when the errors were discovered. In a heated letter to the '' Evening Star'', she said the reliefs were not meant to be historically accurate: "Of course, we knew all this, but we disregarded it because we wanted these panels to portray the most prominent men of the history of the country who were in the Senate during the 16 years that my husband was Senator." She added to reproduce historically accurate scenes would have been "absurd."

Later history

In 1930, Congress renamed Iowa Circle in honor of Logan, who had briefly lived at 4 Logan Circle in 1885. The statue is one of eighteen Civil War monuments in Washington, D.C., that were collectively listed on theNational Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government's official United States National Register of Historic Places listings, list of sites, buildings, structures, Hist ...

(NRHP) on September 20, 1978, and the District of Columbia Inventory of Historic Sites

The District of Columbia Inventory of Historic Sites is a register of historic places in Washington, D.C. that are designated by the District of Columbia Historic Preservation Review Board (HPRB), a component of the District of Columbia Govern ...

on March 3, 1979. It is also designated a contributing property

In the law regulating historic districts in the United States, a contributing property or contributing resource is any building, object, or structure which adds to the historical integrity or architectural qualities that make the historic dist ...

to the Logan Circle Historic District, listed on the NRHP on June 30, 1972, and the Fourteenth Street Historic District

The Fourteenth Street Historic District is located in the Logan Circle and U Street Corridor (a.k.a. Cardozo/Shaw) neighborhoods of Washington, D.C. It was listed on both the District of Columbia Inventory of Historic Sites and the National Regi ...

, listed on the NRHP on November 9, 1994. The monument and surrounding park are owned and maintained by the National Park Service

The National Park Service (NPS) is an List of federal agencies in the United States, agency of the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government, within the US Department of the Interior. The service manages all List ...

, a federal agency of the Interior Department

An interior ministry or ministry of the interior (also called ministry of home affairs or ministry of internal affairs) is a government department that is responsible for domestic policy, public security and law enforcement.

In some states, the i ...

.

Design and location

P Street

P Street refers to four different streets within the city of Washington, D.C. The streets were named by President George Washington in 1791 as part of a general street naming program, in which east–west running streets were named alphabeticall ...

, Rhode Island Avenue

Rhode Island Avenue is a diagonal avenue in the Northwest and Northeast quadrants of Washington, D.C., and the capital's inner suburbs in Prince George's County, Maryland. Paralleling New York Avenue, Rhode Island Avenue was one of the origina ...

and Vermont Avenue NW. Sidewalks lead from the edge of the circle to the monument on axis with the surrounding streets. Around twenty oak trees are planted throughout the circle and a small, ornamental iron fence surrounds the statue base.

The bronze equestrian statue measures tall, long, and wide. It weighs approximately . Logan is depicted with collar-length hair and a moustache, wearing his Civil War military uniform; a long belted jacket, boots, gloves, and a hat. He holds the horse's reins with his left hand and his right hand holds his sword, pointed downward. The horse is striding forward, with its right foot raised. The inscriptions "FOND. NELLI ROMA 1897" and "FRANKLIN SIMMONS" are found on the statue.

The statue rests on a rectangular bronze base which is itself on top of a low granite base. The base is high, long, and wide. It weighs approximately . A bald eagle

The bald eagle (''Haliaeetus leucocephalus'') is a bird of prey found in North America. A sea eagle, it has two known subspecies and forms a species pair with the white-tailed eagle (''Haliaeetus albicilla''), which occupies the same niche ...

symbolizing Patriotism adorns the upper section of each corner of the bronze base. Around the inscription "LOGAN" are palm leaves symbolizing Victory. These are located on the east and west sides of the lower portion of the bronze base. The relief on the west side of the base depicts Logan surrounded by fellow officers discussing the Civil War. The officers include Generals Francis Preston Blair Jr.

Francis Preston Blair Jr. (February 19, 1821 – July 8, 1875) was a United States Senator, a United States Congressman and a Union Army major general during the American Civil War. He represented Missouri in both the House of Representatives a ...

, Dodge, William Babcock Hazen

William Babcock Hazen (September 27, 1830 – January 16, 1887) was a career United States Army officer who served in the Indian Wars, as a Union general in the American Civil War, and as Chief Signal Officer of the U.S. Army. His most famous ser ...

, Mortimer Dormer Leggett, Joseph A. Mower, and Henry Warner Slocum

Henry Warner Slocum Sr. (September 24, 1827 – April 14, 1894), was a Union general during the American Civil War and later served in the United States House of Representatives from New York. During the war, he was one of the youngest major ...

, and Captain Bill Strong. On Logan's proper right is a map spread on a table with three of the officers studying it. The remaining officers are looking towards Logan who has his left hand resting on the map. The relief on the east side of the base depicts Logan being sworn into office as a senator by Vice President Arthur. Logan's right arm is raised while Arthur's left hand is raised and holding a book. Other senators depicted in the relief include Roscoe Conkling

Roscoe Conkling (October 30, 1829April 18, 1888) was an American lawyer and Republican Party (United States), Republican politician who represented New York (state), New York in the United States House of Representatives and the United States Se ...

, Cullom, William M. Evarts, John F. Miller, Oliver P. Morton, Allen G. Thurman, and Daniel W. Voorhees

Daniel Wolsey Voorhees (September 26, 1827April 10, 1897) was an American lawyer and politician who served as a United States Senator from Indiana from 1877 to 1897. He was the leader of the Democratic Party and an anti-war Copperhead during ...

. A female allegorical figure is on the north and south sides of the base. The figure on the north side, representing Peace or Victory, is holding a laurel wreath

A laurel wreath is a symbol of triumph, a wreath (attire), wreath made of connected branches and leaves of the bay laurel (), an aromatic broadleaf evergreen. It was also later made from spineless butcher's broom (''Ruscus hypoglossum'') or cher ...

in her right hand and a fasces

A fasces ( ; ; a , from the Latin word , meaning 'bundle'; ) is a bound bundle of wooden rods, often but not always including an axe (occasionally two axes) with its blade emerging. The fasces is an Italian symbol that had its origin in the Etrus ...

in her left hand. She is wearing long robes and has a laurel wreath on her head. The figure on the south side, representing War, is holding a shield with her left hand and a sword with her right hand. She is wearing a dress adorned with armor details and a crown-shaped helmet.

See also

*List of equestrian statues in the United States

This is a list of equestrian statues in the United States.

List

Alabama

Alaska

*Girdwood, Anchorage, Girdwood

**''Mountain Man'', by Frederic Remington, Alyeska Resort cast 1907(?)

Arizona

*Phoenix, Arizona, Phoenix

** ''Lariat Cowboy'' ...

* List of public art in Washington, D.C., Ward 2

* Outdoor sculpture in Washington, D.C.

There are many outdoor sculptures in Washington, D.C. In addition to the capital's most famous monuments and memorials, many figures recognized as national heroes (either in government or military) have been posthumously awarded with their own s ...

References

External links

* {{Public art in Washington, D.C., state=collapsed 1901 sculptures Bronze sculptures in Washington, D.C.Logan

Logan may refer to:

Places

* Mount Logan (disambiguation)

Australia

* Logan (Queensland electoral district), an electoral district in the Queensland Legislative Assembly

* Logan, Victoria, small locality near St. Arnaud

* Logan City, local gove ...

Logan

Logan may refer to:

Places

* Mount Logan (disambiguation)

Australia

* Logan (Queensland electoral district), an electoral district in the Queensland Legislative Assembly

* Logan, Victoria, small locality near St. Arnaud

* Logan City, local gove ...

Historic district contributing properties in Washington, D.C.

Logan Circle (Washington, D.C.)

Outdoor sculptures in Washington, D.C.