Mae West (life Preserver) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Mary Jane "Mae" West (August 17, 1893 – November 22, 1980) was an American actress, singer, comedian, screenwriter, and playwright whose career spanned more than seven decades. Recognized as a prominent

West continued to build her career in

West continued to build her career in

In June 1932, after signing a two-month contract with Paramount that provided her a weekly salary of $5,000 ($110,000 in 2023), West left New York by train for California. The veteran stage performer was by then nearly 40 years old, yet managed to keep her age ambiguous for some time. She made her film debut in the role of Maudie Triplett in '' Night After Night'' (1932) starring

In June 1932, after signing a two-month contract with Paramount that provided her a weekly salary of $5,000 ($110,000 in 2023), West left New York by train for California. The veteran stage performer was by then nearly 40 years old, yet managed to keep her age ambiguous for some time. She made her film debut in the role of Maudie Triplett in '' Night After Night'' (1932) starring  By 1933, West was one of the largest box-office draws in the United States and, by 1935, she was also the highest paid woman and the second-highest paid person in the United States (after

By 1933, West was one of the largest box-office draws in the United States and, by 1935, she was also the highest paid woman and the second-highest paid person in the United States (after

After appearing in ''The Heat's On'' in 1943, West returned to a highly active stage and nightclub career. Among her notable performances was the title role in '' Catherine Was Great'' (1944) on Broadway, a play she wrote as a satirical take on the life of

After appearing in ''The Heat's On'' in 1943, West returned to a highly active stage and nightclub career. Among her notable performances was the title role in '' Catherine Was Great'' (1944) on Broadway, a play she wrote as a satirical take on the life of

In 1975, West released the books ''Sex, Health, and ESP'' and ''Pleasure Man'', the latter based on her 1928 stage play. Her 1959 autobiography, ''Goodness Had Nothing to Do With It'', was also updated and reissued during this period. She managed her own stage acts and invested in real estate, including property in

In 1975, West released the books ''Sex, Health, and ESP'' and ''Pleasure Man'', the latter based on her 1928 stage play. Her 1959 autobiography, ''Goodness Had Nothing to Do With It'', was also updated and reissued during this period. She managed her own stage acts and invested in real estate, including property in

In August 1980, West tripped while getting out of bed. After the fall, she was unable to speak and was taken to Good Samaritan Hospital in Los Angeles, where tests revealed that she had suffered a

In August 1980, West tripped while getting out of bed. After the fall, she was unable to speak and was taken to Good Samaritan Hospital in Los Angeles, where tests revealed that she had suffered a

''Mae West''

on

Mae West

', on

Mae West

on

Mae West

on

sex symbol

A sex symbol or icon is a person or character widely considered sexually attractive and often synonymous with sexuality. Pam Cook, "The trouble with sex: Diana Dors and the Blonde bombshell phenomenon", In: Bruce Babinigton (ed.), ''British St ...

of her time, she was known for portraying sexually confident characters and for her use of double entendre

A double entendre (plural double entendres) is a figure of speech or a particular way of wording that is devised to have a double meaning, one of which is typically obvious, and the other often conveys a message that would be too socially unacc ...

s, often delivering her lines in a distinctive contralto

A contralto () is a classical music, classical female singing human voice, voice whose vocal range is the lowest of their voice type, voice types.

The contralto's vocal range is fairly rare, similar to the mezzo-soprano, and almost identical to ...

voice. West began performing in vaudeville

Vaudeville (; ) is a theatrical genre of variety entertainment which began in France in the middle of the 19th century. A ''vaudeville'' was originally a comedy without psychological or moral intentions, based on a comical situation: a drama ...

and on stage in New York City before moving on to film in Los Angeles.

She was frequently associated with controversies over censorship

Censorship is the suppression of speech, public communication, or other information. This may be done on the basis that such material is considered objectionable, harmful, sensitive, or "inconvenient". Censorship can be conducted by governmen ...

and once stated, "I believe in censorship. I made a fortune out of it." As her film career declined, she remained active by writing books and plays, performing in Las Vegas

Las Vegas, colloquially referred to as Vegas, is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Nevada and the county seat of Clark County. The Las Vegas Valley metropolitan area is the largest within the greater Mojave Desert, and second-l ...

and London, and appearing on radio and television. In later years, she also released rock and roll

Rock and roll (often written as rock & roll, rock-n-roll, and rock 'n' roll) is a Genre (music), genre of popular music that evolved in the United States during the late 1940s and early 1950s. It Origins of rock and roll, originated from African ...

recordings. In 1999, the American Film Institute

The American Film Institute (AFI) is an American nonprofit film organization that educates filmmakers and honors the heritage of the History of cinema in the United States, motion picture arts in the United States. AFI is supported by private fu ...

ranked her 15th among the greatest female screen legends of classic American cinema.

Early life

Mary Jane West was born on August 17, 1893, in either the Greenpoint orBushwick

Bushwick is a neighborhood in the northern part of the New York City borough of Brooklyn. It is bounded by the neighborhood of Ridgewood, Queens, to the northeast; Williamsburg to the northwest; the cemeteries of Highland Park to the southe ...

neighborhood of Brooklyn

Brooklyn is a Boroughs of New York City, borough of New York City located at the westernmost end of Long Island in the New York (state), State of New York. Formerly an independent city, the borough is coextensive with Kings County, one of twelv ...

, New York, before the consolidation of New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

. She was delivered at home by her aunt, a midwife

A midwife (: midwives) is a health professional who cares for mothers and Infant, newborns around childbirth, a specialisation known as midwifery.

The education and training for a midwife concentrates extensively on the care of women throughou ...

.

She was the eldest surviving child of Mathilde Delker (originally "Doelger" and later Americanized to "Delker" or "Dilker") West, a corset

A corset /ˈkɔːrsɪt/ is a support garment worn to constrict the torso into the desired shape and Posture correction, posture. They are traditionally constructed out of fabric with boning made of Baleen, whalebone or steel, a stiff panel in th ...

and fashion model, and John Patrick "Battlin' Jack" West, a former prizefighter who later worked as a "special policeman" and founded a private investigation agency.

Her mother, known as "Tillie" or "Matilda", was a German immigrant from Bavaria

Bavaria, officially the Free State of Bavaria, is a States of Germany, state in the southeast of Germany. With an area of , it is the list of German states by area, largest German state by land area, comprising approximately 1/5 of the total l ...

, who arrived in 1886 with her siblings and parents, Christiana (née Brüning) and Jakob Doelger. West's paternal grandmother, Mary Jane (née Copley), was of Irish descent, and her paternal grandfather, John Edwin West, was of English and Scottish ancestry.

Her parents married in Brooklyn on January 18, 1889. According to reports, the groom's parents approved of the union, while the bride's family opposed it. They raised their children in the Protestant

Protestantism is a branch of Christianity that emphasizes Justification (theology), justification of sinners Sola fide, through faith alone, the teaching that Salvation in Christianity, salvation comes by unmerited Grace in Christianity, divin ...

faith.

West's eldest sister, Katie, died in infancy. Her surviving siblings were Mildred Katherine "Beverly" West and John Edwin West II (often incorrectly referred to as "Jr."). During her childhood, the family lived in various areas of Woodhaven, Queens

Woodhaven is a neighborhood in the southwestern section of the New York City borough of Queens. It is bordered on the north by Park Lane South and Forest Park, on the east by Richmond Hill, on the south by Ozone Park and Atlantic Avenue, an ...

and the Williamsburg

Williamsburg may refer to:

Places

*Colonial Williamsburg, a living-history museum and private foundation in Virginia

*Williamsburg, Brooklyn, neighborhood in New York City

*Williamsburg, former name of Kernville (former town), California

*Williams ...

and Greenpoint neighborhoods of Brooklyn.

West may have first performed publicly at Neir's Social Hall in Woodhaven.

Career

Beginning of stage career

West was five when she first entertained a crowd at a church social, and she began appearing in amateur shows at the age of seven. She frequently won prizes at local talent contests. She began performing professionally in vaudeville in the Hal Clarendon Stock Company in 1907, at the age of 14. As a child performer, West used the stage name "Baby Mae" (''the baby may behave like this''), and later tried various personas, including a male impersonator. Early in her career, she sometimes used the alias "Jane Mast". Her distinctive walk was said to have been inspired or influenced by female impersonatorsBert Savoy

Bert Savoy (January 7, 1876 or 1888 – June 26, 1923), born Everett McKenzie, was an American entertainer who specialized in cross-dressing as a vaudeville act. His comedic skits contributed to popular culture with phrases such as "You slay me" ...

and Julian Eltinge

Julian Eltinge (May 14, 1881 – March 7, 1941), born William Julian Dalton, was an American Stage (theatre), stage and film actor and female impersonator. After appearing in the Boston Cadets Revue at the age of ten in feminine garb, Elting ...

, who were prominent during the Pansy Craze

The Pansy Craze was a period of increased LGBT visibility in American popular culture from the late 1920s until the mid-1930s. During the " craze," drag queens — known as "pansy performers" — experienced a surge in underground popularity, ...

.

West made her first appearance in a Broadway

Broadway may refer to:

Theatre

* Broadway Theatre (disambiguation)

* Broadway theatre, theatrical productions in professional theatres near Broadway, Manhattan, New York City, U.S.

** Broadway (Manhattan), the street

** Broadway Theatre (53rd Stre ...

show in 1911, at age 18, in a revue titled ''A La Broadway'' staged by her former dancing teacher, Ned Wayburn

Ned Wayburn ''(né'' Edward Claudius Weyburn; 30 March 1874 – 2 September 1942) was an American choreographer.

Career

Edward Claudius Weyburn was born on March 30, 1874 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania to Elbert Delos Weyburn and his wife, Harri ...

. The show closed after only eight performances, but West was praised in a ''New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'' review, which noted that "a girl named Mae West, hitherto unknown, pleased by her grotesquerie and snappy way of singing and dancing." She next appeared in '' Vera Violetta'', which also featured Al Jolson

Al Jolson (born Asa Yoelson, ; May 26, 1886 – October 23, 1950) was a Lithuanian-born American singer, comedian, actor, and vaudevillian.

Self-billed as "The World's Greatest Entertainer," Jolson was one of the United States' most famous and ...

, and in 1912, she played La Petite Daffy, a "baby vamp", in ''A Winsome Widow

''A Winsome Widow'' is a 1912 musical produced by Florenz Ziegfeld, Jr., which was a revised version of Charles Hale Hoyt's 1891 hit, '' A Trip to Chinatown'', with a score by Raymond Hubbell.

History

The show debuted at the Moulin Rouge on Ap ...

''.

West continued to build her career in

West continued to build her career in vaudeville

Vaudeville (; ) is a theatrical genre of variety entertainment which began in France in the middle of the 19th century. A ''vaudeville'' was originally a comedy without psychological or moral intentions, based on a comical situation: a drama ...

, appearing in circuits such as that run by Gus Sun of Ohio. She credited her mother as a constant supporter who believed everything Mae did was "fantastic", though other family members—including an aunt and her paternal grandmother—disapproved of her performing career. In 1918, West gained significant attention in the Shubert Brothers

The Shubert family was responsible for the establishment of Broadway theaters in New York City's Theater District, as the hub of the theatre industry in the United States. Through the Shubert Organization, founded by brothers Lee, Sam, and Jac ...

revue ''Sometime'', starring opposite Ed Wynn

Isaiah Edwin Leopold (November 9, 1886 – June 19, 1966), better known as Ed Wynn, was an American actor and comedian. He began his career in vaudeville in 1903 and was known for his ''Perfect Fool'' comedy character, his pioneering radio show ...

. Her character, Mayme, danced the shimmy

A shimmy or shoulder shakes is a dance move in which the body is held still, except for the shoulders, which are quickly alternated back and forth. When the right shoulder goes back, the left one comes forward.

United States

In 1917, a dance ...

, and her photograph was featured on the sheet music for the popular number "Ev'rybody Shimmies Now".

Broadway stardom and jail

Eventually, West began writing her own risqué plays using the pen name Jane Mast. Her first starring role on Broadway was in the 1926 play ''Sex

Sex is the biological trait that determines whether a sexually reproducing organism produces male or female gametes. During sexual reproduction, a male and a female gamete fuse to form a zygote, which develops into an offspring that inheri ...

'', which she wrote, produced, and directed. Although conservative critics panned the show, ticket sales were strong. The production did not go over well with city officials, who had received complaints from religious groups, and the theater was raided and West arrested along with the cast. She was taken to the Jefferson Market Court House, where she was prosecuted on morals charges, and on April 19, 1927, she was sentenced to 10 days for "corrupting the morals of youth". Though West could have paid a fine and been released, she chose the jail sentence for the publicity it would garner. While incarcerated on Welfare Island, she dined with the warden and his wife and told reporters she had worn her silk panties while serving time, instead of the "burlap" issued to other inmates. She served eight days, with two days off for good behavior, and afterward told reporters that her play was "a work of art". Media attention surrounding the incident enhanced her career, with reporters dubbing her a "bad girl" who "had climbed the ladder of success wrong by wrong."

Her next play, '' The Drag'', dealt with homosexuality and was what West called one of her "comedy-dramas of life." After a series of try-outs in Connecticut and New Jersey, West announced she would open the play in New York. However, ''The Drag'' never opened on Broadway, owing to efforts by the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice

The New York Society for the Suppression of Vice (NYSSV or SSV) was an organization dedicated to supervising the morality of the public, founded in 1873. Its specific mission was to monitor compliance with state laws and work with the courts and d ...

to ban any attempt by West to stage it. West explained, "The city fathers begged me not to bring the show to New York because they were not equipped to handle the commotion it would cause." West was an early supporter of the women's liberation movement

The women's liberation movement (WLM) was a political alignment of women and feminist intellectualism. It emerged in the late 1960s and continued till the 1980s, primarily in the industrialized nations of the Western world, which resulted in g ...

, though she said she was not a "burn your bra" type of feminist

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideology, ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social gender equality, equality of the sexes. Feminism holds the position that modern soci ...

. Since the 1920s, she also supported gay rights and spoke publicly against police brutality toward gay men. She expressed the then-modern belief that gay men were women's souls in men's bodies, and said that hitting a gay man was akin to hitting a woman.

In her 1959 autobiography, ''Goodness Had Nothing to Do With It'', ghostwritten by Stephen Longstreet, West condemned hypocrisy while also voicing concerns about homosexuality:

This perspective seems at odds with her later statements, such as in her 1975 book ''Mae West: Sex, Health, and ESP'', in which she wrote:

Between the late 1920s and early 1930s, West continued to write plays, including '' The Wicked Age'', '' Pleasure Man'', and '' The Constant Sinner''. These productions stirred controversy, which helped keep West in the headlines and filled seats at performances. Her 1928 play '' Diamond Lil'', a story about a racy but clever lady of the 1890s, became a Broadway hit. West revived it many times throughout her career.

Three years later, she played Babe Gordon in ''The Constant Sinner'', which opened at the Royale Theatre

The Bernard B. Jacobs Theatre (formerly the Royale Theatre and the John Golden Theatre) is a Broadway theater at 242 West 45th Street ( George Abbott Way) in the Theater District of Midtown Manhattan in New York City, New York, U.S. Opened ...

on September 14, 1931. ''New York Times'' critic J. Brooks Atkinson gave the show a scathing review:

Other critics similarly dismissed the play as "clumsy", "deliberately outlandish", and referred to West as an "atrocious playwright". The play closed after 64 performances. Compared to ''Diamond Lil'', which ran for 323 performances, ''The Constant Sinner'' was a disappointment. Still, its notoriety enhanced West's public image as a daring and provocative performer. Soon afterward, she accepted a contract from Paramount Pictures

Paramount Pictures Corporation, commonly known as Paramount Pictures or simply Paramount, is an American film production company, production and Distribution (marketing), distribution company and the flagship namesake subsidiary of Paramount ...

to begin her Hollywood film career.

Motion pictures and censorship

In June 1932, after signing a two-month contract with Paramount that provided her a weekly salary of $5,000 ($110,000 in 2023), West left New York by train for California. The veteran stage performer was by then nearly 40 years old, yet managed to keep her age ambiguous for some time. She made her film debut in the role of Maudie Triplett in '' Night After Night'' (1932) starring

In June 1932, after signing a two-month contract with Paramount that provided her a weekly salary of $5,000 ($110,000 in 2023), West left New York by train for California. The veteran stage performer was by then nearly 40 years old, yet managed to keep her age ambiguous for some time. She made her film debut in the role of Maudie Triplett in '' Night After Night'' (1932) starring George Raft

George Raft (né Ranft; September 26, 1901 – November 24, 1980) was an American film actor and dancer identified with portrayals of gangsters in crime melodramas of the 1930s and 1940s. A stylish leading man in dozens of movies, Raft is remembe ...

, who had suggested West for the part. She did not like her small supporting role in the drama at first, but was appeased when she was allowed to rewrite portions of her character's dialogue. One of several revisions she made is in her first scene in ''Night After Night'', when a hat-check girl exclaims, "Goodness, what beautiful diamonds", and West replies, "Goodness had nothing to do with it, dearie." Reflecting on the overall result of her rewritten scenes, Raft is reported to have said, "She stole everything but the cameras."

For her next role for Paramount, West brought her ''Diamond Lil'' character, now renamed "Lady Lou", to the screen in ''She Done Him Wrong

''She Done Him Wrong'' is a 1933 pre-Code American crime/comedy film starring Mae West and Cary Grant, directed by Lowell Sherman. The plot includes melodramatic and musical elements, with a supporting cast featuring Owen Moore, Gilbert Roland, ...

'' (1933). The film was one of Cary Grant

Cary Grant (born Archibald Alec Leach; January 18, 1904November 29, 1986) was an English and American actor. Known for his blended British and American accent, debonair demeanor, lighthearted approach to acting, and sense of comic timing, he ...

's early major roles, which boosted his career. West claimed she spotted Grant at the studio and insisted that he be cast as the male lead. She claimed to have told a Paramount director, "If he can talk, I'll take him!" The film was a box office hit and earned an Academy Award

The Academy Awards, commonly known as the Oscars, are awards for artistic and technical merit in film. They are presented annually by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS) in the United States in recognition of excellence ...

nomination for Best Picture

The following is a list of categories of awards commonly awarded through organizations that bestow film awards, including those presented by various films, festivals, and people's awards.

Best Actor/Best Actress

*See Best Actor#Film awards, Bes ...

. The success of the film saved Paramount from bankruptcy, grossing over $2 million, the equivalent of $46 million in 2023. Paramount recognizes that debt of gratitude today, with a building on the lot named after West.

Her next release, ''I'm No Angel

''I'm No Angel'' is a 1933 American pre-Code black comedy film directed by Wesley Ruggles, and starring Mae West and Cary Grant. West received sole story and screenplay credit. It is one of her early films, and, as such, was not subjected to t ...

'' (1933), teamed her again with Grant. The film was also a box-office hit and was the most successful of her entire screen career. In the months after its release, references to West could be found almost everywhere, from the song lyrics of Cole Porter

Cole Albert Porter (June 9, 1891 – October 15, 1964) was an American composer and songwriter. Many of his songs became Standard (music), standards noted for their witty, urbane lyrics, and many of his scores found success on Broadway the ...

, to a Works Progress Administration

The Works Progress Administration (WPA; from 1935 to 1939, then known as the Work Projects Administration from 1939 to 1943) was an American New Deal agency that employed millions of jobseekers (mostly men who were not formally educated) to car ...

(WPA) mural of San Francisco's newly built Coit Tower

Coit Tower (also known as Coit Memorial Tower) is a tower in the Telegraph Hill, San Francisco, Telegraph Hill neighborhood of San Francisco, California, overlooking the city and San Francisco Bay. The tower, in the city's Pioneer Park, San Franc ...

, to '' She Done Him Right'', a Pooch the Pup

Pooch the Pup is a cartoon animal character, an anthropomorphic dog, appearing in Walter Lantz cartoons during the studio's black-and-white era. The character appeared in 13 shorts made in 1932 and 1933.

Biography

In 1931, Walter Lantz was en ...

cartoon, to '' My Dress Hangs There'', a painting by Mexican artist Frida Kahlo

Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderón (; 6 July 1907 – 13 July 1954) was a Mexican painter known for her many portraits, self-portraits, and works inspired by the nature and artifacts of Mexico. Inspired by Culture of Mexico, the country' ...

. Kahlo's husband, Diego Rivera

Diego Rivera (; December 8, 1886 – November 24, 1957) was a Mexican painter. His large frescoes helped establish the Mexican muralism, mural movement in Mexican art, Mexican and international art.

Between 1922 and 1953, Rivera painted mural ...

, paid his own tribute: "West is the most wonderful machine for living I have ever known—unfortunately on the screen only." To F. Scott Fitzgerald

Francis Scott Key Fitzgerald (September 24, 1896 – December 21, 1940), widely known simply as Scott Fitzgerald, was an American novelist, essayist, and short story writer. He is best known for his novels depicting the flamboyance and exces ...

, West was especially unique: "The only Hollywood actress with both an ironic edge and a comic spark." As ''Variety

Variety may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Entertainment formats

* Variety (radio)

* Variety show, in theater and television

Films

* ''Variety'' (1925 film), a German silent film directed by Ewald Andre Dupont

* ''Variety'' (1935 film), ...

'' put it, "Mae West's films have made her the biggest conversation-provoker, free-space grabber, and all-around box office bet in the country. She's as hot an issue as Hitler."

By 1933, West was one of the largest box-office draws in the United States and, by 1935, she was also the highest paid woman and the second-highest paid person in the United States (after

By 1933, West was one of the largest box-office draws in the United States and, by 1935, she was also the highest paid woman and the second-highest paid person in the United States (after William Randolph Hearst

William Randolph Hearst (; April 29, 1863 – August 14, 1951) was an American newspaper publisher and politician who developed the nation's largest newspaper chain and media company, Hearst Communications. His extravagant methods of yellow jou ...

). Hearst invited West to Hearst Castle

Hearst Castle, known formally as La Cuesta Encantada ( Spanish for "The Enchanted Hill"), is a historic estate in San Simeon, located on the Central Coast of California. Conceived by William Randolph Hearst, the publishing tycoon, and his arc ...

, his massive estate in San Simeon

San Simeon ( Spanish: ''San Simeón'', meaning "St. Simon") is an unincorporated community on the Pacific coast of San Luis Obispo County, California, United States. Its position along State Route 1 is about halfway between Los Angeles and San ...

, California, where Hollywood celebrities and prominent political and business figures frequently gathered to socialize. "I could'a married him," West later commented, "but I got no time for parties. I don't like those big crowds." On July 1, 1934, the censorship guidelines of the film industry's Production Code

The Motion Picture Production Code was a set of industry guidelines for the self-censorship of content that was applied to most motion pictures released by major studios in the United States from 1934 to 1968. It is also popularly known as th ...

began to be meticulously enforced. As a result, West's scripts were subjected to more editing. She, in turn, would often intentionally place extremely risqué lines in her scripts, knowing they would be cut by the censors. She hoped they would then not object as much to her other less suggestive lines. Her next film was ''Belle of the Nineties

''Belle of the Nineties'' is a 1934 American Western film directed by Leo McCarey and released by Paramount Pictures. Mae West's fourth motion picture, it was based on her original story ''It Ain't No Sin'', which was also to be the film's title ...

'' (1934). The original title, ''It Ain't No Sin'', was changed because of censors' objections. Despite Paramount's early objections regarding costs, West insisted the studio hire Duke Ellington

Edward Kennedy "Duke" Ellington (April 29, 1899 – May 24, 1974) was an American Jazz piano, jazz pianist, composer, and leader of his eponymous Big band, jazz orchestra from 1924 through the rest of his life.

Born and raised in Washington, D ...

and his orchestra to accompany her in the film's musical numbers. Their collaboration was a success; the classic "My Old Flame "My Old Flame" is a 1934 song composed by Arthur Johnston with lyrics by Sam Coslow for the film '' Belle of the Nineties''. It has since become a jazz standard.

History

"My Old Flame" first appeared in the 1934 film '' Belle of the Nineties'' whe ...

" was introduced in this film. Her next film, ''Goin' to Town

''Goin' To Town'' is a 1935 musical film, musical comedy film directed by Alexander Hall and written by Mae West. The film stars Mae West, Paul Cavanagh, Gilbert Emery, Marjorie Gateson, Tito Coral, and Ivan Lebedeff. The film was released on Ap ...

'' (1935), received mixed reviews, as censorship continued to take its toll by preventing West from including her best lines.

Her following effort, ''Klondike Annie

''Klondike Annie'' is a 1936 American Western film starring Mae West and Victor McLaglen. The film was co-written by West from her play ''Frisco Kate'', which she wrote in 1921 and a story written by the duo Marion Morgan and George Brendan Do ...

'' (1936), dealt, as best it could given the heavy censorship, with religion and hypocrisy. Some critics called the film her magnum opus

A masterpiece, , or ; ; ) is a creation that has been given much critical praise, especially one that is considered the greatest work of a person's career or a work of outstanding creativity, skill, profundity, or workmanship.

Historically, ...

, but not everyone agreed. Press baron William Randolph Hearst, offended by a remark West made about his mistress Marion Davies

Marion Davies (born Marion Cecilia Douras; January 3, 1897 – September 22, 1961) was an American actress, producer, screenwriter, and philanthropist. Educated in a religious convent, Davies left the school to pursue a career as a chorus girl ...

, sent a private memo to his editors stating: "That Mae West picture ''Klondike Annie'' is a filthy picture... DO NOT ACCEPT ANY ADVERTISING OF THIS PICTURE." Paramount executives felt they had to tone down West's characterization. "I was the first liberated woman, you know. No guy was going to get the best of me. That's what I wrote all my scripts about."

Around the same time, West played opposite Randolph Scott

George Randolph Scott (January 23, 1898 – March 2, 1987) was an American film actor, whose Hollywood career spanned from 1928 to 1962. As a leading man for all but the first three years of his cinematic career, Scott appeared in dramas, come ...

in ''Go West, Young Man

"Go West, young man" is a phrase, the origin of which is often credited to the American author and newspaper editor Horace Greeley, concerning America's expansion westward as related to the concept of Manifest destiny. No one has yet proven who ...

'' (1936), adapting Lawrence Riley

Lawrence Riley (1896–1974) was a successful American playwright and screenwriter. He gained fame in 1934 as the author of the Broadway hit '' Personal Appearance'', which was turned by Mae West into the film ''Go West, Young Man'' (1936).

Bio ...

's Broadway hit '' Personal Appearance''. Directed by Henry Hathaway

Henry Hathaway (March 13, 1898 – February 11, 1985) was an American film director and producer. He is best known as a director of Western (genre), Westerns, especially starring Randolph Scott and John Wayne. He directed Gary Cooper in seven f ...

, it is considered one of West's weaker films of the era due to censor cuts.

West next starred in '' Every Day's a Holiday'' (1937) for Paramount before their association ended. Censorship had increasingly made West's sexually suggestive humor difficult to sustain on screen. She was included in the " Box Office Poison" list published by the Independent Theatre Owners Association. This did not stop producer David O. Selznick

David O. Selznick (born David Selznick; May 10, 1902June 22, 1965) was an American film producer, screenwriter and film studio executive who produced ''Gone with the Wind (film), Gone with the Wind'' (1939) and ''Rebecca (1940 film), Rebecca'' (1 ...

from offering her the role of Belle Watling in ''Gone with the Wind Gone with the Wind most often refers to:

* Gone with the Wind (novel), ''Gone with the Wind'' (novel), a 1936 novel by Margaret Mitchell

* Gone with the Wind (film), ''Gone with the Wind'' (film), the 1939 adaptation of the novel

Gone with the Wind ...

'', but West declined, saying it was too small and would need rewriting.

In 1939, Universal Studios Universal Studios may refer to:

* Universal Studios, Inc., an American media and entertainment conglomerate

** Universal Pictures, an American film studio

** Universal Studios Lot, a film and television studio complex

* Various theme parks operat ...

approached West to star opposite W. C. Fields

William Claude Dukenfield (January 29, 1880 – December 25, 1946), better known as W. C. Fields, was an American actor, comedian, juggler and writer. His career in show business began in vaudeville, where he attained international success as a ...

in ''My Little Chickadee

''My Little Chickadee'' is a 1940 American comedy-western film starring Mae West and W. C. Fields, featuring Joseph Calleia, Ruth Donnelly, Margaret Hamilton, Donald Meek, Willard Robertson, Dick Foran, William B. Davidson, and Addison ...

'' (1940). Although West and Fields had a combative relationship, the film was a box office success. Religious leaders condemned West's on-screen persona, taking offense at lines such as: "When I'm caught between two evils, I generally like to take the one I never tried."

West's final film of the period was ''The Heat's On

''The Heat's On'' (1943) is a musical movie starring Mae West, William Gaxton, and Victor Moore, and released by Columbia Pictures.

Plot

Broadway star Fay Lawrence is a temperamental diva who is reluctantly persuaded by a Broadway producer t ...

'' (1943), produced by Columbia Pictures. She only agreed to star as a personal favor to director Gregory Ratoff

Gregory Ratoff (born Grigory Vasilyevich Ratner; ; April 20, c. 1893 – December 14, 1960) was a Russian-American film director, actor and producer. As an actor, he was best known for his role as producer "Max Fabian" in ''All About Eve'' (195 ...

. It was the only film where she was not allowed to write her own dialogue. The result was poorly received, and West later cited her frustration with censorship as a key reason for her departure from filmmaking. Instead, she found continued success in nightclubs, stage shows, and Broadway revivals where she retained creative control over her performances.

Radio and censorship

On December 12, 1937, West appeared in two separate sketches onventriloquist

Ventriloquism or ventriloquy is an act of stagecraft in which a person (a ventriloquist) speaks in such a way that it seems like their voice is coming from a different location, usually through a puppet known as a "dummy". The act of ventrilo ...

Edgar Bergen

Edgar John Bergen (né Berggren; February 16, 1903 – September 30, 1978) was an American ventriloquist, comedian, actor, vaudevillian and radio performer. He was best known for his characters Charlie McCarthy and Mortimer Snerd. Bergen ...

's radio show

A radio program, radio programme, or radio show is a segment of content intended for broadcast on radio. It may be a one-time production, or part of a periodically recurring series. A single program in a series is called an episode.

Radio netw ...

''The Chase and Sanborn Hour

''The Chase and Sanborn Hour'' is the umbrella title for a series of American comedy and variety radio shows sponsored by Standard Brands' Chase and Sanborn Coffee, usually airing Sundays on NBC from 8 p.m. to 9 p.m. during the years 1929 t ...

''. Appearing as herself, West flirted with Charlie McCarthy

Charlie McCarthy was a dummy partner of American ventriloquist Edgar Bergen. Charlie was part of Bergen's act as early as high school, and by 1930 was attired in a top hat, tuxedo and monocle. The character was so well known that his popularity ex ...

, Bergen's dummy, using her usual brand of wit and risqué sexual references. West referred to Charlie as "all wood and a yard long" and commented, "Charles, I remember our last date, and have the splinters to prove it!" West was on the verge of being banned from radio.

Another controversial sketch aired the same night on NBC

The National Broadcasting Company (NBC) is an American commercial broadcast television and radio network serving as the flagship property of the NBC Entertainment division of NBCUniversal, a subsidiary of Comcast. It is one of NBCUniversal's ...

, written by Arch Oboler

Arch Oboler (December 7, 1907 – March 19, 1987) was an American playwright, screenwriter, novelist, producer, and director who was active in radio, films, theater, and television. He generated much attention with his radio scripts, particular ...

, and featured Don Ameche

Don Ameche (; born Dominic Felix Amici; May 31, 1908 – December 6, 1993) was an American actor, comedian and vaudevillian. After playing in college shows, repertory theatre, and vaudeville, he became a major radio star in the early 19 ...

and West as Adam and Eve

Adam and Eve, according to the creation myth of the Abrahamic religions, were the first man and woman. They are central to the belief that humanity is in essence a single family, with everyone descended from a single pair of original ancestors. ...

in the Garden of Eden

In Abrahamic religions, the Garden of Eden (; ; ) or Garden of God ( and ), also called the Terrestrial Paradise, is the biblical paradise described in Genesis 2–3 and Ezekiel 28 and 31..

The location of Eden is described in the Book of Ge ...

. She tells Ameche to "get me a big one... I feel like doin' a big apple!" This ostensible reference to the then-current dance craze

''Dance Craze'' is a 1981 documentary film about the British Two-tone (music genre), 2 Tone music genre.

The film was directed by Joe Massot, who originally wanted to do a film only about the band Madness (band), Madness, whom he met during th ...

was one of the many double entendres

A double entendre (plural double entendres) is a figure of speech or a particular way of wording that is devised to have a double meaning, one of which is typically obvious, and the other often conveys a message that would be too socially unacc ...

in the dialogue. Days after the broadcast, the studio received letters calling the show "immoral" and "obscene". Several conservative women's clubs and religious groups admonished the show's sponsor, Chase & Sanborn Coffee Company

Chase & Sanborn Coffee is an American brand of coffee created by the coffee roasting and tea and coffee importing company of the same name, established in 1864 in Boston, Massachusetts, by Caleb Chase (1831-1908) and James Solomon Sanborn (18 ...

, for "prostituting" their services for allowing "impurity oinvade the air".

Under pressure, the Federal Communications Commission

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) is an independent agency of the United States government that regulates communications by radio, television, wire, internet, wi-fi, satellite, and cable across the United States. The FCC maintains j ...

later deemed the broadcast "vulgar and indecent" and "far below even the minimum standard which should control in the selection and production of broadcast programs". Some debate existed regarding the reaction to the skit. Conservative religious groups took umbrage far more swiftly than the mainstream. These groups found it easy to make West their target. They took exception to her outspoken use of sexuality and sexual imagery, which she had employed in her career since at least the pre-Code

Pre-Code Hollywood was an era in the Cinema of the United States, American film industry that occurred between the widespread adoption of sound in film in the late 1920s and the enforcement of the Motion Picture Production Code censorship gui ...

films of the early 1930s and for decades before on Broadway, but which was now being broadcast into American living rooms on a popular family-friendly radio program. The groups reportedly warned the sponsor of the program they would protest her appearance.

NBC Radio banned West (and the mention of her name) from their stations following the backlash. She did not return to radio until January 1950, when she appeared on an episode of ''The Chesterfield Supper Club

''The Chesterfield Supper Club'' is an NBC Radio musical variety program (1944–1950), which was also telecast by NBC Television (1948–1950).

Radio

''The Chesterfield Supper Club'' began on December 11, 1944, as a 15-minute radio program, a ...

'', hosted by Perry Como

Pierino Ronald "Perry" Como (; May 18, 1912 – May 12, 2001) was an American singer, actor, and television personality. During a career spanning more than half a century, he recorded exclusively for RCA Victor for 44 years, from 1943 until 1987 ...

. Ameche's career did not suffer any serious repercussions, however, as he was playing the "straight" character. West subsequently continued to perform in venues such as Lou Walters's The Latin Quarter, Broadway, and London.

Middle years

After appearing in ''The Heat's On'' in 1943, West returned to a highly active stage and nightclub career. Among her notable performances was the title role in '' Catherine Was Great'' (1944) on Broadway, a play she wrote as a satirical take on the life of

After appearing in ''The Heat's On'' in 1943, West returned to a highly active stage and nightclub career. Among her notable performances was the title role in '' Catherine Was Great'' (1944) on Broadway, a play she wrote as a satirical take on the life of Catherine the Great

Catherine II. (born Princess Sophie of Anhalt-Zerbst; 2 May 172917 November 1796), most commonly known as Catherine the Great, was the reigning empress of Russia from 1762 to 1796. She came to power after overthrowing her husband, Peter I ...

. In the production, she surrounded herself with a group of tall, muscular actors described as an "imperial guard". Produced by theater and film impresario Mike Todd

Michael Todd (born Avrom Hirsch Goldbogen; June 22, 1907 – March 22, 1958) was an American theater and film producer, celebrated for his 1956 ''Around the World in 80 Days (1956 film), Around the World in 80 Days'', which won an Academy ...

, the play ran for 191 performances before going on tour.

West revived her 1928 play ''Diamond Lil'' in 1949, returning it to Broadway. A reviewer for ''The New York Times'' referred to her as an "American institution—as beloved and indestructible as Donald Duck. Like Chinatown, and Grant's Tomb, Mae West should be seen at least once." In the 1950s, she performed in her own Las Vegas stage show at the newly opened Sahara Hotel

Sahara Las Vegas is a hotel and casino located on the Las Vegas Strip in Winchester, Nevada. It is owned and operated by the Meruelo Group. The hotel has 1,616 rooms, and the casino contains . The Sahara anchors the northern end of the Las Veg ...

, where she sang while flanked by bodybuilders. The show proved popular with both male and female audiences, with West commenting, "Men come to see me, but I also give the women something to see: wall to wall men."

During the casting of Billy Wilder

Billy Wilder (; ; born Samuel Wilder; June 22, 1906 – March 27, 2002) was an American filmmaker and screenwriter. His career in Hollywood (film industry), Hollywood spanned five decades, and he is regarded as one of the most brilliant and ver ...

's 1950 film ''Sunset Boulevard

Sunset Boulevard is a boulevard in the central and western part of Los Angeles, California, United States, that stretches from the Pacific Coast Highway (California), Pacific Coast Highway in Pacific Palisades, Los Angeles, Pacific Palisad ...

'', West was offered the role of Norma Desmond

''Sunset Boulevard'' is a 1950 American dark comedy film noir directed by Billy Wilder and co-written by Wilder, Charles Brackett and D. M. Marshman Jr. It is named after a major street that runs through Hollywood.

The film stars William Ho ...

. Still frustrated by the censorship imposed on ''The Heat's On'', she declined the role, stating that its pathos did not suit her comedic sensibility, which she characterized as focused on uplifting audiences. The role ultimately went to Gloria Swanson

Gloria Mae Josephine Swanson (March 27, 1899April 4, 1983) was an American actress. She first achieved fame acting in dozens of silent films in the 1920s and was nominated three times for the Academy Award for Best Actress, most famously for h ...

, after Mary Pickford

Gladys Louise Smith (April 8, 1892 – May 29, 1979), known professionally as Mary Pickford, was a Canadian-American film actress and producer. A Canadian pioneers in early Hollywood, pioneer in the American film industry with a Hollywood care ...

also declined.

West was later offered additional film roles, including Vera Simpson opposite Frank Sinatra

Francis Albert Sinatra (; December 12, 1915 – May 14, 1998) was an American singer and actor. Honorific nicknames in popular music, Nicknamed the "Chairman of the Board" and "Ol' Blue Eyes", he is regarded as one of the Time 100: The Most I ...

in the 1957 musical ''Pal Joey Pal Joey may refer to:

* ''Pal Joey'' (novel), a 1940 epistolary novel by John O'Hara

* ''Pal Joey'' (musical), a 1940 musical based on the novel

* ''Pal Joey'' (film), a 1957 film, loosely adapted from the musical of the same name

* ''Pal Joey' ...

'', which she declined, with the part going to Rita Hayworth

Rita Hayworth (born Margarita Carmen Cansino; October 17, 1918May 14, 1987) was an American actress, dancer, and Pin-up model, pin-up girl. She achieved fame in the 1940s as one of the top stars of the Classical Hollywood cinema, Golden Age of ...

. She also turned down a role in ''Roustabout

Roustabout (Australia/New Zealand English: rouseabout) is an occupational term. Traditionally, it referred to a worker with broad-based, non-specific skills. In particular, it was used to describe show or circus workers who put up tents and boo ...

'' (1964) alongside Elvis Presley

Elvis Aaron Presley (January 8, 1935 – August 16, 1977) was an American singer and actor. Referred to as the "King of Rock and Roll", he is regarded as Cultural impact of Elvis Presley, one of the most significant cultural figures of the ...

, which was subsequently played by Barbara Stanwyck

Barbara Stanwyck (; born Ruby Catherine Stevens; July 16, 1907 – January 20, 1990) was an American actress and dancer. A stage, film, and television star, during her 60-year professional career, she was known for her strong, realistic screen p ...

. West rejected offers from Federico Fellini

Federico Fellini (; 20 January 1920 – 31 October 1993) was an Italian film director and screenwriter. He is known for his distinctive style, which blends fantasy and baroque images with earthiness. He is recognized as one of the greatest and ...

to appear in both ''Juliet of the Spirits

''Juliet of the Spirits'' () is a 1965 fantasy comedy-drama film directed by Federico Fellini and starring Giulietta Masina, Sandra Milo, Mario Pisu, Valentina Cortese, and Valeska Gert. The film is about the visions, memories, and mysticism ...

'' and ''Satyricon

The ''Satyricon'', ''Satyricon'' ''liber'' (''The Book of Satyrlike Adventures''), or ''Satyrica'', is a Latin work of fiction believed to have been written by Gaius Petronius in the late 1st century AD, though the manuscript tradition identifi ...

''.

Television, and the next generations

On March 26, 1958, West appeared at the live televisedAcademy Awards

The Academy Awards, commonly known as the Oscars, are awards for artistic and technical merit in film. They are presented annually by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS) in the United States in recognition of excellence in ...

and performed the song "Baby, It's Cold Outside

"Baby, It's Cold Outside" is a popular song written by Frank Loesser in 1944 and popularized in the 1949 film '' Neptune's Daughter''. While the lyrics make no mention of a holiday, it is commonly regarded as a Christmas song owing to its winter ...

" with Rock Hudson

Rock Hudson (born Roy Harold Scherer Jr.; November 17, 1925 – October 2, 1985) was an American actor. One of the most popular film stars of his time, he had a screen career spanning more than three decades, and was a prominent figure in the G ...

, which received a standing ovation. In 1959, she released an autobiography, ''Goodness Had Nothing to Do With It'', which became a best-seller. West made several television appearances to promote the book, including on '' The Dean Martin Variety Show'' in 1959 and ''The Red Skelton Show

''The Red Skelton Show'' is an American television comedy/variety show that aired from 1951 to 1971. In the decade prior to hosting the show, Richard "Red" Skelton had a successful career as a radio and motion pictures star. Although his tele ...

'' in 1960. She also recorded a lengthy interview for ''Person to Person

''Person to Person'' is a popular television program in the United States that originally ran from 1953 to 1961, with two episodes of an attempted revival airing in 2012. Edward R. Murrow hosted the original series from its inception in 1953 un ...

'' with Charles Collingwood in 1959, which was ultimately not broadcast; CBS executives reportedly felt viewers were not prepared to see a nude marble statue of West that appeared in the segment. In 1964, she guest-starred on the sitcom ''Mister Ed

''Mister Ed'' is an American television sitcom produced by Filmways that aired in syndication from January 5 to July 2, 1961, and then on CBS from October 1, 1961, to February 6, 1966. The show's title character is a talking horse which orig ...

''. In 1976, she appeared on a CBS special, ''Back Lot U.S.A.'', hosted by Dick Cavett

Richard Alva Cavett (; born November 19, 1936) is an American television personality and former talk show host. He appeared regularly on nationally broadcast television in the United States from the 1960s through the 2000s.

In later years, Cave ...

, where she was interviewed and performed two songs.

Recording career

West's recording career began in the early 1930s with releases of songs from her films on78 rpm records

A phonograph record (also known as a gramophone record, especially in British English) or a vinyl record (for later varieties only) is an analog signal, analog sound Recording medium, storage medium in the form of a flat disc with an inscribed, ...

. These were issued alongside sheet music for home use. In 1955, she recorded her first LP album, ''The Fabulous Mae West''. In 1965, she recorded two songs, "Am I Too Young" and "He's Good for Me", for a 45 rpm single released by Plaza Records. She also recorded novelty songs such as "Santa, Come Up to See Me", featured on the album ''Wild Christmas'', which was later reissued in 1980 as ''Mae in December''. In 1966, she released the rock-and-roll album '' Way Out West'', followed in 1972 by ''Great Balls of Fire

"Great Balls of Fire" is a 1957 popular song recorded by American rock and roll musician Jerry Lee Lewis on Sun Records and featured in the 1957 movie '' Jamboree''. It was written by Otis Blackwell and Jack Hammer. The Jerry Lee Lewis 1957 reco ...

'', which included covers of songs by The Doors

The Doors were an American rock band formed in Los Angeles in 1965, comprising vocalist Jim Morrison, keyboardist Ray Manzarek, guitarist Robby Krieger and drummer John Densmore. They were among the most influential and controversial rock acts ...

and tracks written by English songwriter-producer Ian Whitcomb

Ian Timothy Whitcomb (10 July 1941 – 19 April 2020) was an English entertainer, singer-songwriter, record producer, writer, broadcaster and actor. As part of the British Invasion, his hit song " You Turn Me On" reached number 8 on the ''B ...

.

Later years

West's likeness was used on the front cover ofthe Beatles

The Beatles were an English Rock music, rock band formed in Liverpool in 1960. The core lineup of the band comprised John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr. They are widely regarded as the Cultural impact of the Beatle ...

' 1967 album ''Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band

''Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band'' (often referred to simply as ''Sgt. Pepper'') is the eighth studio album by the English rock band the Beatles. Released on 26May 1967, ''Sgt. Pepper'' is regarded by musicologists as an early concept ...

''. When approached for permission, West initially declined, reportedly asking, "What would I be doing in a Lonely Hearts Club?" She changed her mind after receiving a letter from the band expressing admiration for her work.

After a 27-year absence from motion pictures, West returned to the screen as Leticia Van Allen in ''Myra Breckinridge

''Myra Breckinridge'' is a 1968 satirical novel by Gore Vidal written in the form of a diary. Described by the critic Dennis Altman as "part of a major cultural assault on the assumed norms of gender and sexuality which swept the western world ...

'' (1970), based on the novel by Gore Vidal

Eugene Luther Gore Vidal ( ; born Eugene Louis Vidal, October 3, 1925 – July 31, 2012) was an American writer and public intellectual known for his acerbic epigrammatic wit. His novels and essays interrogated the Social norm, social and sexual ...

. The film starred Raquel Welch

Jo Raquel Welch (; September 5, 1940 – February 15, 2023) was an American actress. Welch first gained attention for her role in ''Fantastic Voyage'' (1966), after which she signed a long-term contract with 20th Century Fox. They lent her con ...

, Rex Reed

Rex Taylor Reed (born October 2, 1938) is an American film critic, journalist, and media personality.

Raised throughout the southern United States and educated at Louisiana State University, Reed moved to New York City in the early 1960s to begi ...

, Farrah Fawcett

Farrah Fawcett (born Ferrah Leni Fawcett; February 2, 1947 – June 25, 2009) was an American actress. A four-time Primetime Emmy Award nominee and six-time Golden Globe Award nominee, Fawcett rose to international fame when she played a ...

, and Tom Selleck

Thomas William Selleck (; born January 29, 1945) is an American actor. His breakout role was playing private investigator Thomas Magnum in the television series ''Magnum, P.I.'' (1980–1988), for which he received five Emmy Award nominations fo ...

, but was hampered by production difficulties and poor critical reception. Though West received top billing, her role was reduced during editing. In 1971, she was voted "Woman of the Century" by students at University of California, Los Angeles

The University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) is a public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Los Angeles, California, United States. Its academic roots were established in 1881 as a normal school the ...

(UCLA) for her legacy as an outspoken figure on issues of sexuality and censorship.

In 1975, West released the books ''Sex, Health, and ESP'' and ''Pleasure Man'', the latter based on her 1928 stage play. Her 1959 autobiography, ''Goodness Had Nothing to Do With It'', was also updated and reissued during this period. She managed her own stage acts and invested in real estate, including property in

In 1975, West released the books ''Sex, Health, and ESP'' and ''Pleasure Man'', the latter based on her 1928 stage play. Her 1959 autobiography, ''Goodness Had Nothing to Do With It'', was also updated and reissued during this period. She managed her own stage acts and invested in real estate, including property in Van Nuys

Van Nuys ( ) is a neighborhood in the central San Fernando Valley region of Los Angeles, California. Home to Van Nuys Airport and the Valley Municipal Building, it is the most populous neighborhood in the San Fernando Valley.

History

In 1 ...

, Los Angeles.

She appeared on the CBS television special ''Back Lot U.S.A.'' in 1976, where she was interviewed by Dick Cavett

Richard Alva Cavett (; born November 19, 1936) is an American television personality and former talk show host. He appeared regularly on nationally broadcast television in the United States from the 1960s through the 2000s.

In later years, Cave ...

and performed "Frankie and Johnny" and "After You've Gone".

That year, she began production on her final film, ''Sextette

''Sextette'' is a 1978 American musical comedy film directed by Ken Hughes, and starring Mae West in her final film, alongside an ensemble cast including Timothy Dalton, Dom DeLuise, Tony Curtis, Ringo Starr, Keith Moon, George Hamilton, Alice ...

'' (1978), based on a script she had written in 1959. Frequent revisions and production delays led to a decision to feed her lines via a speaker concealed in her wig due to her deteriorating eyesight. Despite these challenges, director Ken Hughes

Kenneth Graham Hughes (19 January 1922 – 28 April 2001) was an English film director and screenwriter. He worked on over 30 feature films between 1952 and 1981, including the 1968 musical fantasy film ''Chitty Chitty Bang Bang'', based on th ...

later described her as committed to completing the film. ''Sextette'' was not a commercial success. Its cast included George Raft

George Raft (né Ranft; September 26, 1901 – November 24, 1980) was an American film actor and dancer identified with portrayals of gangsters in crime melodramas of the 1930s and 1940s. A stylish leading man in dozens of movies, Raft is remembe ...

, Tony Curtis

Tony Curtis (born Bernard Schwartz; June 3, 1925September 29, 2010) was an American actor with a career that spanned six decades, achieving the height of his popularity in the 1950s and early 1960s. He acted in more than 100 films, in roles co ...

, Timothy Dalton

Timothy Leonard Dalton Leggett (; born 21 March 1946) is a British actor. He gained international prominence as the fourth actor to portray fictional secret agent James Bond in the Eon Productions film series, starring in '' The Living Dayli ...

, Walter Pidgeon

Walter Davis Pidgeon (September 23, 1897 – September 25, 1984) was a Canadian-American actor. A major leading man during the Golden Age of Hollywood, known for his "portrayals of men who prove both sturdy and wise," Pidgeon earned two Academy ...

, Ringo Starr

Sir Richard Starkey (born 7 July 1940), known professionally as Ringo Starr, is an English musician, songwriter and actor who achieved international fame as the drummer for the Beatles. Starr occasionally sang lead vocals with the group, us ...

, Alice Cooper

Vincent Damon Furnier (born February 4, 1948), known by his stage name Alice Cooper, is an American rock singer and songwriter whose career spans sixty years. With a raspy voice and a stage show that features numerous props and stage illusion ...

, Dom DeLuise

Dominick DeLuise (August 1, 1933 – May 4, 2009) was an American actor, comedian, director, musician, chef, and author. Known primarily for comedy roles, he rose to fame in the 1970s as a frequent guest on television variety shows. He is widely ...

, and Rona Barrett

Rona Barrett (born Rona Burstein, October 8, 1936) is an American gossip columnist and businesswoman. She runs the Rona Barrett Foundation, a non-profit organization in Santa Ynez, California, dedicated to the aid and support of senior citizen ...

, along with several of West's former Las Vegas performers, such as Reg Lewis. The film reunited her with costume designer Edith Head

Edith Claire Head (née Posener, October 28, 1897 – October 24, 1981) was an American film costume designer who won a record eight Academy Awards for Academy Award for Best Costume Design, Best Costume Design between 1949 and 1973, making he ...

, who had worked on ''She Done Him Wrong'' in 1933.

West was awarded a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame

The Hollywood Walk of Fame is a landmark which consists of 2,813 five-pointed terrazzo-and-brass stars embedded in the sidewalks along 15 blocks of Hollywood Boulevard and three blocks of Vine Street in the Hollywood, Los Angeles, Hollywood dist ...

at 1560 Vine Street for her work in film and was later inducted into the American Theater Hall of Fame

The American Theater Hall of Fame was founded in 1972 in New York City. The first head of its executive committee was Earl Blackwell. In an announcement in 1972, he said that the new ''Theater Hall of Fame'' would be located in the Uris Theatre, ...

for her contributions to stage performance.

Public image

Mae West was known for her distinctive appearance, often characterized by figure-hugging, floor-length gowns with low necklines. Her style typically featured details such as fishtail trains and feather trim, which became associated with her on-screen persona.Personal life

West was married on April 11, 1911, inMilwaukee, Wisconsin

Milwaukee is the List of cities in Wisconsin, most populous city in the U.S. state of Wisconsin. Located on the western shore of Lake Michigan, it is the List of United States cities by population, 31st-most populous city in the United States ...

, to Frank Szatkus (1892–1966), whose stage name was Frank Wallace, a fellow vaudevillian whom she met in 1909. She was 17. She kept the marriage a secret, but a filing clerk discovered the certificate in 1935 and alerted the press. The clerk also uncovered an affidavit

An ( ; Medieval Latin for "he has declared under oath") is a written statement voluntarily made by an ''affiant'' or ''deposition (law), deponent'' under an oath or affirmation which is administered by a person who is authorized to do so by la ...

from her 1927 ''Sex'' trial, in which she had declared herself married. At first, West denied the marriage but admitted it in July 1937 in response to a legal interrogatory. The couple never lived together as husband and wife; she stated they had separate bedrooms and soon sent him away to headline his own show. She obtained a divorce on July 21, 1942, during which Wallace withdrew his request for separate maintenance, and West testified that they had lived together for only "several weeks". The final divorce decree was granted on May 7, 1943.

In 1913, West met Guido Deiro

Count Guido Pietro Deiro (1 September 1886 – 26 July 1950) was a famous vaudeville star, international recording artist, composer and teacher. He was the first piano-accordionist to appear on big-time vaudeville, records, radio and the screen. ...

(1886–1950), an Italian-born vaudeville star and accordionist. According to his son, Guido Roberto Deiro, West married Deiro in 1914, though this has not been conclusively proven. Their relationship reportedly ended after West had an abortion at her mother's urging, which left her infertile and nearly killed her. West later quipped, "Marriage is a great institution. I'm not ready for an institution."

In 1916, West began a relationship with James Timony (1884–1954), an attorney and her manager. By the mid-1930s, they were no longer a couple but remained close until his death.

She was also romantically linked to Owney Madden

Owen Vincent "Owney" Madden (December 18, 1891 – April 24, 1965) was an Irish-American gangsterhttps://www.theirishstory.com/2022/06/01/owney-the-killer-madden-irish-bootlegger-who-became-the-hotelier-for-the-mob/ who was a leading underworld f ...

, owner of the Cotton Club

The Cotton Club was a 20th-century nightclub in New York City. It was located on 142nd Street and Lenox Avenue from 1923 to 1936, then briefly in the midtown Theater District until 1940. The club operated during the United States' era of P ...

.

West remained close to her family throughout her life and was especially affected by her mother's death in 1930. She moved into the penthouse at The Ravenswood

The Ravenswood is a historic apartment building in Art Deco style at 570 North Rossmore Avenue in the Hancock Park neighborhood of Los Angeles, California. It was designed by Max Maltzman, and built by Paramount Pictures in 1930 just five block ...

in Hollywood that year, remaining there until her death. She later brought her father, sister, and brother to Hollywood and supported them. She also had a relationship with boxer Gorilla Jones

William Landon Jones (1906–1982) known as "Gorilla" Jones, was an American boxer who held the NBA Middleweight Boxing Championship of the World. Although he was nicknamed "Gorilla" for his exceptional reach, Jones is to be distinguished from th ...

(1906–1982). When her apartment building barred Jones from entry because he was African American, she bought the building and lifted the ban.

In her sixties, West became romantically involved with Chester Rybinski (1923–1999), a former Mr. California and member of her Las Vegas stage show. He later changed his name to Paul Novak. He was 30 years her junior and remained with her until her death. Novak once commented, "I believe I was put on this Earth to take care of Mae West."

West would sometimes refer to herself in the third person

Third person, or third-person, may refer to:

* Third person (grammar), a point of view (in English, ''he'', ''she'', ''it'', and ''they'')

** Illeism, the act of referring to oneself in the third person

* Third-person narrative, a perspective in p ...

and speak of "Mae West" as the entertainment character she had created.

West was a Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Protestant tradition named for its form of church government by representative assemblies of elders, known as "presbyters". Though other Reformed churches are structurally similar, the word ''Pr ...

.

Death

In August 1980, West tripped while getting out of bed. After the fall, she was unable to speak and was taken to Good Samaritan Hospital in Los Angeles, where tests revealed that she had suffered a

In August 1980, West tripped while getting out of bed. After the fall, she was unable to speak and was taken to Good Samaritan Hospital in Los Angeles, where tests revealed that she had suffered a stroke

Stroke is a medical condition in which poor cerebral circulation, blood flow to a part of the brain causes cell death. There are two main types of stroke: brain ischemia, ischemic, due to lack of blood flow, and intracranial hemorrhage, hemor ...

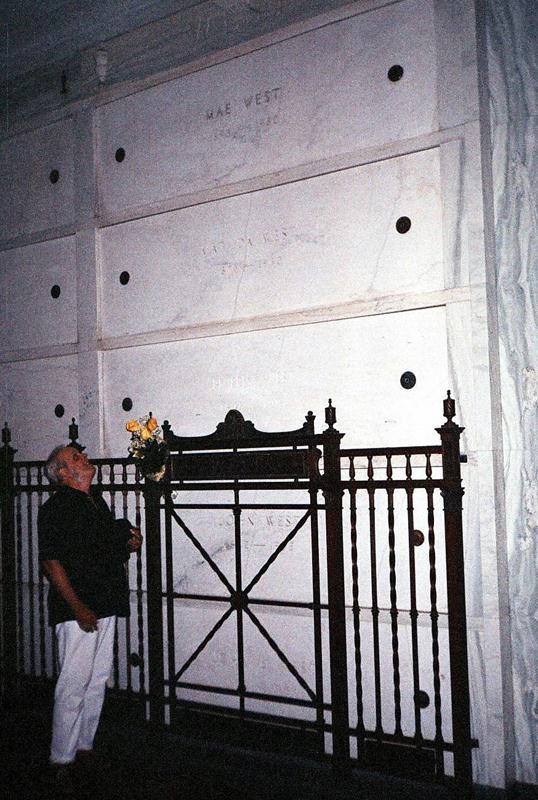

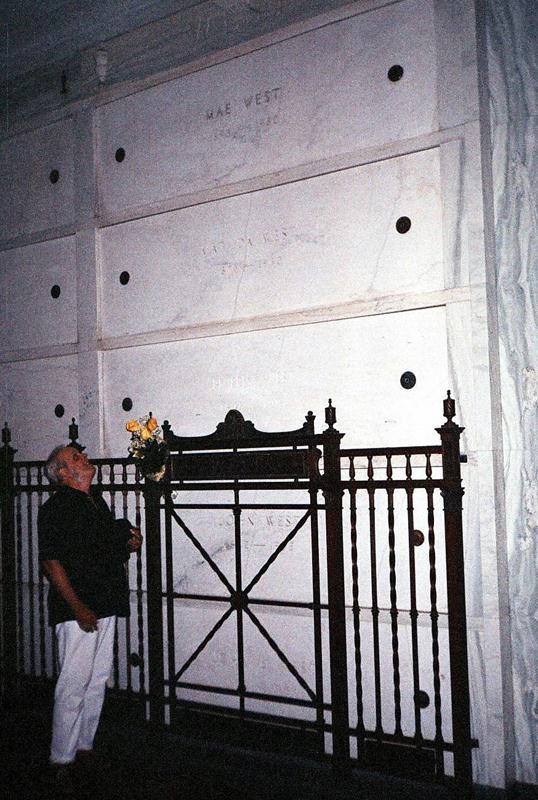

. She died three months later on November 22 at the age of 87.

A private service was held three days later at the church in Forest Lawn Memorial Park Forest Lawn may refer to:

Cemeteries

California

* Forest Lawn Memorial-Parks & Mortuaries, a chain of cemeteries in southern California

* Forest Lawn Cemetery (Cathedral City), California

* Forest Lawn Memorial Park (Glendale), California

* Fore ...

. Her friend, Bishop Andre Penachio, officiated at the entombment in the family mausoleum at Cypress Hills Cemetery

Cypress Hills Cemetery is a non-sectarian/non-denominational cemetery corporation organized in the boroughs of Brooklyn and Queens in New York City, the first of its type in the city. The cemetery is run as a non-profit organization and is lo ...

in Brooklyn

Brooklyn is a Boroughs of New York City, borough of New York City located at the westernmost end of Long Island in the New York (state), State of New York. Formerly an independent city, the borough is coextensive with Kings County, one of twelv ...

, which had been purchased in 1930 when her mother died. Her father and brother had also been entombed there, and her younger sister Beverly was laid to rest in the last of the five crypts less than 18 months later.

In popular culture

* In the 1935 Laurel and Hardy film ''Bonnie Scotland

''Bonnie Scotland'' is a 1935 American film directed by James W. Horne and starring Laurel and Hardy. It was produced by Hal Roach for Hal Roach Studios. Although the film begins in Scotland, a large part of the action is set in British India ...

'', in response to the character Mrs. Burns saying to Mr. Miggs, "The next time you drop down to Glasgow, you must come up and see me some time," Stan comments, "It's Mae West."

* In the 1937 film ''Stand-In

A stand-in, sometimes a lighting double, for film and television is a person who substitutes for the actor before filming, for technical purposes such as lighting and camera setup.

Stand-ins are helpful in the initial processes of film and tele ...

'', the stage mother (Anne O'Neal

Anne O'Neal (born Patsy Ann Epperson; December 23, 1893 – November 24, 1971) was an American actress. She appeared in many films portraying matronly landladies, for example.

On television, in 1957, she appeared on ''Gunsmoke'' as “Sabina P ...

) who has her young daughter (Marianne Edwards

Marianne Edwards (December 9, 1930 – November 8, 2013) was an American child actress who appeared in the ''Our Gang'' film series from 1934 to 1936. She also appeared in several feature films in the 1930s, including ''Gold Diggers Of 1933'', ...

) auditioning for Dodd (Leslie Howard

Leslie Howard Steiner (3 April 18931 June 1943) was an English actor, director, producer and writer.Obituary, '' Variety'', 9 June 1943. He wrote many stories and articles for ''The New York Times'', ''The New Yorker'', and '' Vanity Fair'' an ...

) tells her, "Now, do the Mae West number."

* During World War II, Allied aircrews called their yellow inflatable, vest-like personal flotation device

A personal flotation device (PFD; also referred to as a life jacket, life preserver, life belt, Mae West, life vest, life saver, cork jacket, buoyancy aid or flotation suit) is a flotation device in the form of a vest or suit that is worn by a u ...

s "Mae Wests", partly from rhyming slang

Rhyming slang is a form of slang word construction in the English language. It is especially prevalent among Cockneys in England, and was first used in the early 19th century in the East End of London; hence its alternative name, Cockney rhymin ...

for "breasts" and partly because of the resemblance to her torso. A "Mae West" is also a type of round parachute malfunction that contorts the shape of the canopy into the appearance of a large brassiere

A bra, short for brassiere or brassière (, ; ), is a type of form-fitting underwear that is primarily used to support and cover a woman's breasts. A typical bra consists of a chest band that wraps around the torso, supporting two breast cu ...

.

* West is referenced in songs, including the title number of Cole Porter

Cole Albert Porter (June 9, 1891 – October 15, 1964) was an American composer and songwriter. Many of his songs became Standard (music), standards noted for their witty, urbane lyrics, and many of his scores found success on Broadway the ...

's Broadway musical ''Anything Goes

''Anything Goes'' is a musical with music and lyrics by Cole Porter. The original book was a collaborative effort by Guy Bolton and P. G. Wodehouse, revised considerably by the team of Howard Lindsay and Russel Crouse. The story concerns madc ...

'' and in "You're the Top".

* Surrealist

Surrealism is an art movement, art and cultural movement that developed in Europe in the aftermath of World War I in which artists aimed to allow the unconscious mind to express itself, often resulting in the depiction of illogical or dreamlike s ...

artist Salvador Dalí

Salvador Domingo Felipe Jacinto Dalí i Domènech, Marquess of Dalí of Púbol (11 May 190423 January 1989), known as Salvador Dalí ( ; ; ), was a Spanish Surrealism, surrealist artist renowned for his technical skill, precise draftsmanship, ...

created works inspired by West, including ''Face of Mae West Which May Be Used as an Apartment'' and the '' Mae West Lips Sofa'', completed in 1938 for Edward James

Edward Frank Willis James (16 August 1907 – 2 December 1984) was a British poet known for his patronage of the surrealist art movement.

Early life and marriage

James was born on 16 August 1907, the only son of William James (who had inheri ...

.

* Several of West's comedy lines are used in the parody musical ''Wild Side Story

''Wild Side Story'' is a parody musical that originated in 1973 as a drag show on the gay scene of Miami Beach, soon developed there into an underground happening for mixed audiences, and up until 2004 was performed hundreds of times in Florida, ...

'' (1973–2004).

* In 1982, actress Ann Jillian

Ann Jillian (born Ann Jura Nauseda; January 29, 1950) is an American former actress and singer whose career began as a child actress in 1960. She is best known for her role as the sultry waitress Cassie Cranston on the 1980s sitcom ''It's a Liv ...

portrayed West in the television biopic ''Mae West

Mary Jane "Mae" West (August 17, 1893 – November 22, 1980) was an American actress, singer, comedian, screenwriter, and playwright whose career spanned more than seven decades. Recognized as a prominent sex symbol of her time, she was known ...

''.

* In 2000, '' Dirty Blonde'', written by Claudia Shear

Claudia Shear is an American actress and playwright. She was nominated for the Tony Award, Best Play and Best Actress for her play ''Dirty Blonde (play), Dirty Blonde''.

Early life

Shear was born to Julian "Bud" and Helaine Catoggio. Her mother ...

, opened on Broadway at the Helen Hayes Theater

The Hayes Theater (formerly the Little Theatre, New York Times Hall, Winthrop Ames Theatre, and Helen Hayes Theatre) is a Broadway theater at 240 West 44th Street in the Theater District of Midtown Manhattan in New York City, New York, U.S. ...

.

* MAE-West

MAE-West was an Internet exchange point located on the west coast of the United States in Silicon Valley, in the south San Francisco Bay Area in California. It was established in November, 1994. Its name officially stands for "Metropolitan Area ...

("Metropolitan Area Exchange, West") was a major Internet exchange point

Internet exchange points (IXes or IXPs) are common grounds of Internet Protocol, IP networking, allowing participant Internet service provider, Internet service providers (ISPs) to exchange data destined for their respective networks. IXPs are ...

in the United States, with a corresponding MAE-East

The MAE (later, MAE-East) was the first non-governmental Internet Exchange Point (IXP). It began in 1992 with four locations in Washington, D.C., quickly extended to Vienna, Reston, and Ashburn, Virginia; and then subsequently to New York and Mi ...

on the East Coast.

* In 2016, West was portrayed by drag performer Alaska

Alaska ( ) is a non-contiguous U.S. state on the northwest extremity of North America. Part of the Western United States region, it is one of the two non-contiguous U.S. states, alongside Hawaii. Alaska is also considered to be the north ...

on season 2 of ''RuPaul's Drag Race All Stars

''RuPaul's Drag Race All Stars'' is an American reality competition spin off edition of the original ''RuPaul's Drag Race'', which is produced by World of Wonder, for Logo TV and later VH1. The show premiered on October 22, 2012, on Logo TV, ...

''.

* In 2017, West was the subject of an episode of the TV series ''Over My Dead Body'' on Amazon Prime

Amazon Prime (styled as prime) is a paid subscription service of Amazon which is available in many countries and gives users access to additional services otherwise unavailable or available at a premium to other Amazon customers. Services inclu ...

.

* West was the subject of the 2020 PBS

The Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) is an American public broadcaster and non-commercial, free-to-air television network based in Arlington, Virginia. PBS is a publicly funded nonprofit organization and the most prominent provider of educat ...

documentary ''Mae West: Dirty Blonde'', part of the ''American Masters

''American Masters'' is a PBS television series which produces biographies on enduring writers, musicians, visual and performing artists, dramatists, filmmakers, and those who have left an indelible impression on the cultural landscape of the U ...

'' series and produced by Bette Midler

Bette Midler ( ;''Inside the Actors Studio'', 2004 born December 1, 1945) is an American actress, comedian, singer, and author. Throughout her five-decade career Midler has received List of awards and nominations received by Bette Midler, numero ...

.

* The Canadian dessert cake May West