Madison Grant on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Madison Grant (November 19, 1865 – May 30, 1937) was an American lawyer, zoologist, anthropologist, and writer known for his work as a conservationist,

He was also a developer of

He was also a developer of

Grant was the author of the once much-read book ''

Grant was the author of the once much-read book ''

Grant advocated restricted immigration to the United States through limiting immigration from Eastern Europe and Southern Europe, as well as the complete end of immigration from East Asia. He also advocated efforts to purify the American population through selective breeding. He served as the vice president of the

Grant advocated restricted immigration to the United States through limiting immigration from Eastern Europe and Southern Europe, as well as the complete end of immigration from East Asia. He also advocated efforts to purify the American population through selective breeding. He served as the vice president of the

At the postwar

At the postwar

''The Caribou.''

New York: Office of the New York Zoological Society, 1902. * "Moose". New York: Report of the Forest, Fish, Game Commission, 1903.

''The Origin and Relationship of the Large Mammals of North America.''

New York: Office of the New York Zoological Society, 1904. *

The Rocky Mountain Goat.

' Office of the New York Zoological Society, 1905.

''The Passing of the Great Race; or, The Racial Basis of European History.''

New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1916. *

New ed.

rev. and Amplified, with a New Preface by Henry Fairfield Osborn. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1918 *

Rev. ed.

with a Documentary Supplement, and a Preface by Henry Fairfield Osborn. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1921. *

Fourth rev. ed.

with a Documentary Supplement, and a Preface by Henry Fairfield Osborn. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1936. *

Saving the Redwoods; an Account of the Movement During 1919 to Preserve the Redwoods of California

'' New York: Zoological Society, 1919.Reprinted i

''The National Geographic''

Vol. XXXVII, January/June, 1920.

''Early History of Glacier National Park, Montana.''

Washington: Govt. print. off., 1919.

''The Conquest of a Continent; or, The Expansion of Races in America''

Charles Scribner's Sons, 1933.

"The Depletion of American Forests"

''Century Magazine'', Vol. XLVIII, No. 1, May 1894.

"The Vanishing Moose, and their Extermination in the Adirondacks"

''Century Magazine'', Vol. XLVII, 1894.

"A Canadian Moose Hunt"

In: Theodore Roosevelt (ed.), ''Hunting in Many Lands.'' New York: Forest and Stream Publishing Company, 1895.

"The Future of Our Fauna"

''Zoological Society Bulletin'', No. 34, June 1909.

"History of the Zoological Society"

''Zoological Society Bulletin'', Decennial Number, No. 37, January 1910.

"Condition of Wild Life in Alaska"

In: ''Hunting at High Altitudes.'' New York: Harper & Brothers, Publishers, 1913.

"Wild Life Protection"

''Zoological Society Bulletin'', Vol. XIX, No. 1, January 1916.

"The Passing of the Great Race"

''Geographical Review'', Vol. 2, No. 5, Nov., 1916.

"The Physical Basis of Race"

''Journal of the National Institute of Social Sciences'', Vol. III, January 1917.

"Discussion of Article on Democracy and Heredity"

''The Journal of Heredity'', Vol. X, No. 4, April, 1919.

"Restriction of Immigration: Racial Aspects"

''Journal of the National Institute of Social Sciences'', Vol. VII, August 1921.

"Racial Transformation of America"

''The North American Review'', March 1924.

"America for the Americans"

''The Forum'', September 1925.

"Grant, Madison"

''American National Biography''. Oxford University Press. Online. * Degler, Carl N. (1991). ''In Search of Human Nature: The Decline and Revival of Darwinism in American Social Thought''. Oxford University Press. * Field, Geoffrey G. (1977). "Nordic Racism", ''Journal of the History of Ideas'' 38 (3), pp. 523–540. * Guterl, Matthew Press (2001). ''The Color of Race in America, 1900–1940''. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. * Lee, Erika. "America first, immigrants last: American xenophobia then and now." ''Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era'' 19.1 (2020): 3-18. * Leonard, Thomas C. ''Illiberal Reformers: Race, Eugenics, and American Economics in the Progressive Era'' (Princeton UP, 2016). * Leonard, Thomas C

More Merciful and Not Less Effective': Eugenics and American Economics in the Progressive Era"

''History of Political Economy'' 35.4 (2003): 687-712. * Marcus, Alan P. "The Dangers of the Geographical Imagination in the US Eugenics Movement". ''Geographical Review'' 111.1 (2021): 36-56. * Purdy, Jedediah (2015)

"Environmentalism's Racist History"

''

Excerpt

* Spiro, Jonathan P. "Nordic vs. Anti-Nordic: The Galton Society and the American Anthropological Association", ''Patterns of Prejudice'' 36#1 (2002): 35–48. * Regal, Brian (2002). ''Henry Fairfield Osborn: Race and the Search for the Origins of Man''. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate. * Regal, Brian (2004). "Maxwell Perkins and Madison Grant: Eugenics Publishing at Scribners", ''Princeton University Library Chronicle'' 65#2, pp. 317–341.

Excerpts from ''Passing of the Great Race'' used at the Nuremberg Trials

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Grant, Madison 1865 births 1937 deaths 20th-century American lawyers 20th-century American writers 20th-century American anthropologists Amateur anthropologists American conservationists American conspiracy theorists American Eugenics Society members American hunters American people of English descent American people of French descent American political writers American white nationalists American white supremacists American zoologists Burials at Sleepy Hollow Cemetery Columbia Law School alumni Deaths from nephritis Lawyers from New York City Nordicism Philanthropists from New York (state) People involved in race and intelligence controversies Proponents of scientific racism Writers from New York City Yale University alumni

eugenicist

Eugenics is a set of largely discredited beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetics, genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter the frequency of various human Phenotype, phenotypes by ...

, and advocate of scientific racism

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscience, pseudoscientific belief that the Human, human species is divided into biologically distinct taxa called "race (human categorization), races", and that empirical evi ...

. Grant is less noted for his far-reaching achievements in conservation than for his pseudoscientific

Pseudoscience consists of statements, beliefs, or practices that claim to be both scientific and factual but are incompatible with the scientific method. Pseudoscience is often characterized by contradictory, exaggerated or unfalsifiable cl ...

advocacy of Nordicism

Nordicism is a racialist ideology which views the "Nordic race" (a historical race concept) as an endangered and superior racial group. Some notable and influential Nordicist works include Madison Grant's book '' The Passing of the Great Rac ...

, a form of racism which views the "Nordic race

The Nordic race is an obsolete racial classification of humans based on a now-disproven theory of biological race. It was once considered a race or one of the putative sub-races into which some late-19th to mid-20th century anthropologists di ...

" as superior.

As a white supremacist eugenicist, Grant was the author of ''The Passing of the Great Race

''The Passing of the Great Race: Or, The Racial Basis of European History'' is a 1916 racist and pseudoscientific book by American lawyer, anthropologist, and proponent of eugenics Madison Grant (1865–1937). Grant expounds a theory of Nordi ...

'' (1916), one of the most famous racist texts, a book Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

referred to as his personal Bible. Grant also played an active role in crafting immigration restriction and anti-miscegenation laws in the United States

In the United States, many U.S. states historically had anti-miscegenation laws which prohibited interracial marriage and, in some states, interracial sexual relations. Some of these laws predated the establishment of the United States, and som ...

. As a conservationist, he is credited with the saving of species including the American bison

The American bison (''Bison bison''; : ''bison''), commonly known as the American buffalo, or simply buffalo (not to be confused with Bubalina, true buffalo), is a species of bison that is endemic species, endemic (or native) to North America. ...

, helped create the Bronx Zoo

The Bronx Zoo (also historically the Bronx Zoological Park and the Bronx Zoological Gardens) is a zoo within Bronx Park in the Bronx, New York City. It is one of the largest zoos in the United States by area and the largest Metropolis, metropol ...

, Glacier National Park, and Denali National Park

Denali National Park and Preserve, formerly known as Mount McKinley National Park, is a United States national park and preserve located in Interior Alaska, centered on Denali (federally designated as Mount McKinley), the highest mountain in Nor ...

, and co-founded the Save the Redwoods League. Grant developed much of the discipline of wildlife management

Wildlife management is the management process influencing interactions among and between wildlife, its Habitat, habitats and people to achieve predefined impacts. Wildlife management can include wildlife conservation, population control, gamekeepi ...

.

Early life

Grant was born in New York City, the son of Gabriel Grant, a physician andAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

surgeon, and Caroline Manice. Madison Grant's mother was a descendant of Jessé de Forest

Jessé de Forest ( – October 22, 1624) was the leader of a group of Walloons, Walloon Huguenots who fled Europe due to religious persecution. They emigrated to what would become New Netherland in 1624.

Background

Jessé de Forest was born be ...

, the Walloon Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , ; ) are a Religious denomination, religious group of French people, French Protestants who held to the Reformed (Calvinist) tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, ...

who in 1623 recruited the first band of colonists to settle in New Netherland

New Netherland () was a colony of the Dutch Republic located on the East Coast of what is now the United States. The claimed territories extended from the Delmarva Peninsula to Cape Cod. Settlements were established in what became the states ...

, the Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, commonly referred to in historiography as the Dutch Republic, was a confederation that existed from 1579 until the Batavian Revolution in 1795. It was a predecessor state of the present-day Netherlands ...

's territory on the American East Coast. On his father's side, Madison Grant's first American ancestor was Richard Treat, dean of Pitminster Church in England, who in 1630 was one of the first Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to rid the Church of England of what they considered to be Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should b ...

settlers of New England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

. Grant's forebears through Treat's line include Robert Treat

Robert Treat (February 23, 1622July 12, 1710) was an English-born politician, military officer and colonial administrator who served as the governor of Connecticut from 1683 to 1687 and 1689 to 1698. In 1666, he co-founded the colonial settlemen ...

(a colonial governor of New Jersey), Robert Treat Paine (a signer of the Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of the territory of another state or failed state, or are breaka ...

), Charles Grant (Madison Grant's grandfather, who served as an officer in the War of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States United States declaration of war on the Uni ...

), and Gabriel Grant (father of Madison), a prominent physician and the health commissioner of Newark, New Jersey

Newark ( , ) is the List of municipalities in New Jersey, most populous City (New Jersey), city in the U.S. state of New Jersey, the county seat of Essex County, New Jersey, Essex County, and a principal city of the New York metropolitan area. ...

. Grant was a lifelong resident of New York City.

Grant was the oldest of four siblings. The children's summers, and many of their weekends, were spent at Oatlands, the Long Island

Long Island is a densely populated continental island in southeastern New York (state), New York state, extending into the Atlantic Ocean. It constitutes a significant share of the New York metropolitan area in both population and land are ...

country estate built by their grandfather DeForest Manice in the 1830s. As a child, he attended private schools and traveled Europe and the Middle East with his father. He attended Yale University

Yale University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701, Yale is the List of Colonial Colleges, third-oldest institution of higher education in the United Stat ...

, graduating early and with honors in 1887. He received a law degree from Columbia Law School

Columbia Law School (CLS) is the Law school in the United States, law school of Columbia University, a Private university, private Ivy League university in New York City.

The school was founded in 1858 as the Columbia College Law School. The un ...

, and practiced law after graduation; however, his interests were primarily those of a naturalist. He never married and had no children. He first achieved a political reputation when he and his brother, DeForest Grant, took part in the 1894 electoral campaign of New York mayor William Lafayette Strong.

Career and conservation efforts

Thomas C. Leonard wrote that "Grant was a cofounder of the American environmental movement, a crusading conservationist who preserved the California redwoods; saved the American bison from extinction; fought for stricter gun control laws; helped create Glacier and Denali national parks; and worked to preserve whales, bald eagles, and pronghorn antelopes." Grant was a friend of several U.S. presidents, includingTheodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

and Herbert Hoover

Herbert Clark Hoover (August 10, 1874 – October 20, 1964) was the 31st president of the United States, serving from 1929 to 1933. A wealthy mining engineer before his presidency, Hoover led the wartime Commission for Relief in Belgium and ...

. He is credited with saving many species from extinction, and co-founded the Save the Redwoods League with Frederick Russell Burnham

Major (rank), Major Frederick Russell Burnham Distinguished Service Order, DSO (May 11, 1861 – September 1, 1947) was an American scout and world-traveling adventurer. He is known for his service to the British South Africa Company and to t ...

, John C. Merriam, and Henry Fairfield Osborn in 1918. He is also credited with helping develop the first deer hunting laws in New York state, legislation which spread to other states as well over time.

He was also a developer of

He was also a developer of wildlife management

Wildlife management is the management process influencing interactions among and between wildlife, its Habitat, habitats and people to achieve predefined impacts. Wildlife management can include wildlife conservation, population control, gamekeepi ...

; he believed its development to be harmonized with the concept of eugenics

Eugenics is a set of largely discredited beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter the frequency of various human phenotypes by inhibiting the fer ...

. Grant helped to found the Bronx Zoo

The Bronx Zoo (also historically the Bronx Zoological Park and the Bronx Zoological Gardens) is a zoo within Bronx Park in the Bronx, New York City. It is one of the largest zoos in the United States by area and the largest Metropolis, metropol ...

, build the Bronx River Parkway

The Bronx River Parkway (sometimes abbreviated as the Bronx Parkway) is a limited-access Parkways in New York, parkway in downstate New York in the United States. It is named for the nearby Bronx River, which it parallels. The southern terminus ...

, save the American bison

The American bison (''Bison bison''; : ''bison''), commonly known as the American buffalo, or simply buffalo (not to be confused with Bubalina, true buffalo), is a species of bison that is endemic species, endemic (or native) to North America. ...

as an organizer of the American Bison Society, and helped to create Glacier National Park and Denali National Park

Denali National Park and Preserve, formerly known as Mount McKinley National Park, is a United States national park and preserve located in Interior Alaska, centered on Denali (federally designated as Mount McKinley), the highest mountain in Nor ...

. In 1906, as Secretary of the New York Zoological Society

New or NEW may refer to:

Music

* New, singer of K-pop group The Boyz

* ''New'' (album), by Paul McCartney, 2013

** "New" (Paul McCartney song), 2013

* ''New'' (EP), by Regurgitator, 1995

* "New" (Daya song), 2017

* "New" (No Doubt song), 1 ...

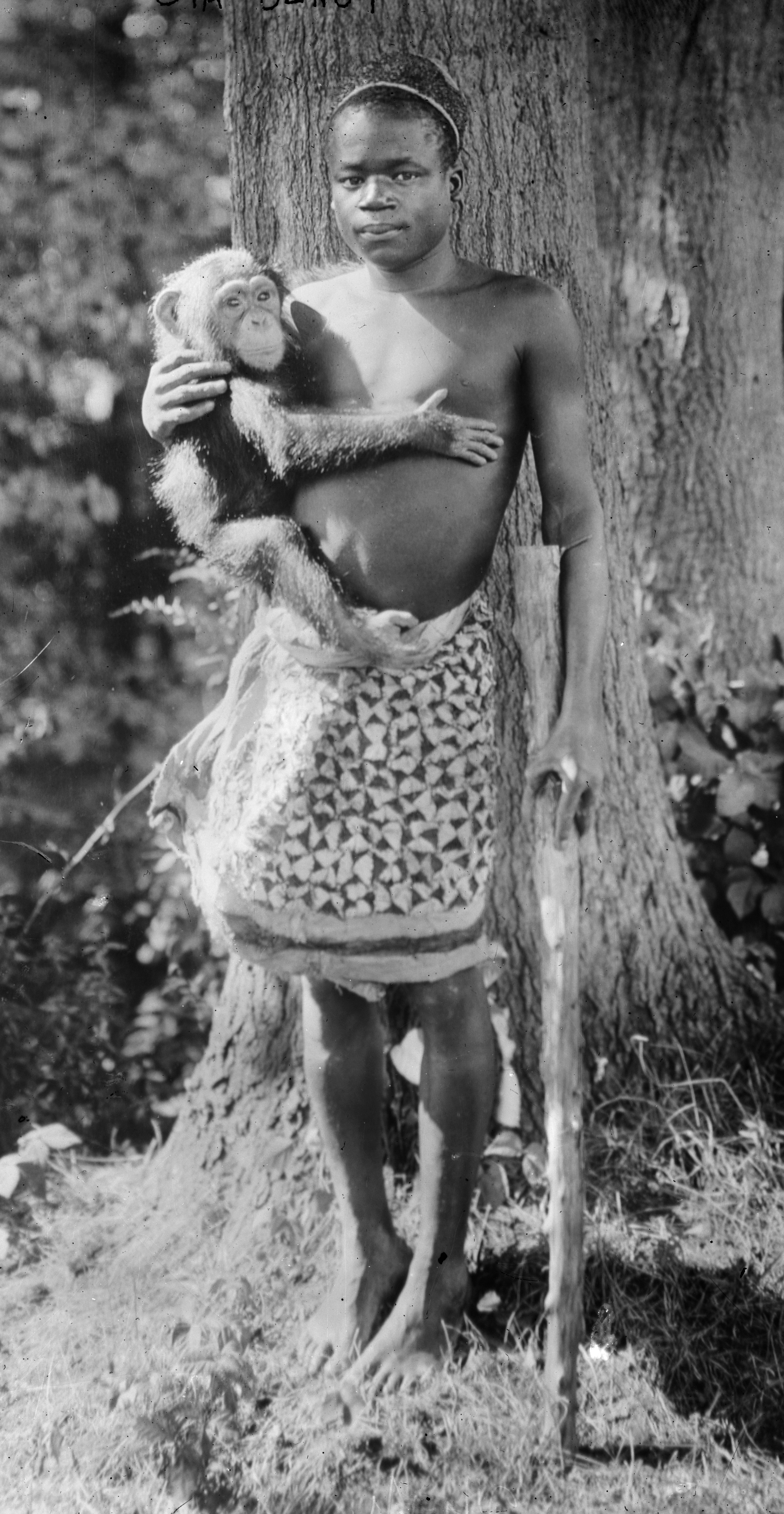

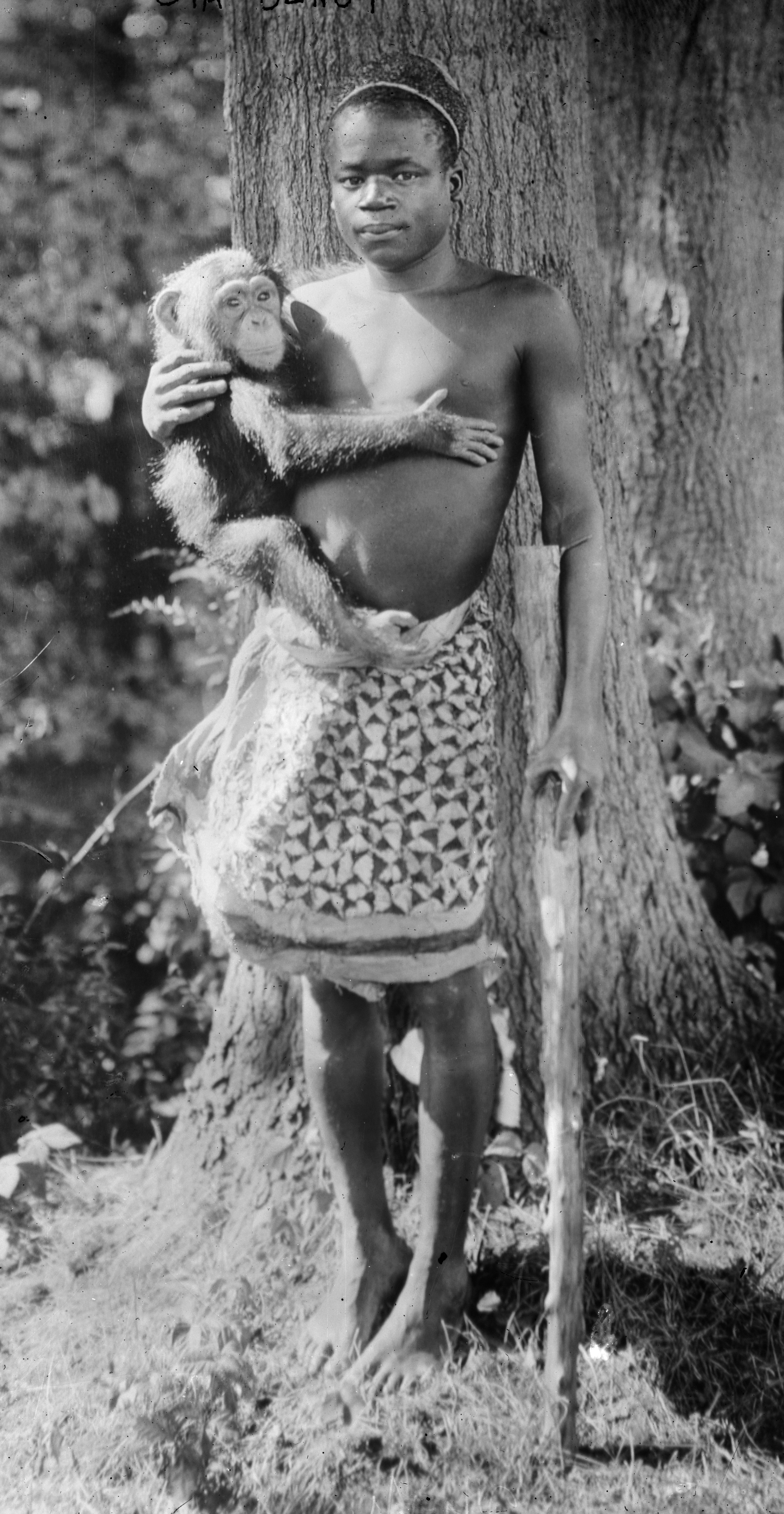

, he lobbied to put Ota Benga, a Congolese man from the Mbuti people (a tribe of "pygmies"), on display alongside apes at the Bronx Zoo

The Bronx Zoo (also historically the Bronx Zoological Park and the Bronx Zoological Gardens) is a zoo within Bronx Park in the Bronx, New York City. It is one of the largest zoos in the United States by area and the largest Metropolis, metropol ...

.

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, he served on the boards of many eugenic and philanthropic societies, including the board of trustees at the American Museum of Natural History

The American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) is a natural history museum on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City. Located in Theodore Roosevelt Park, across the street from Central Park, the museum complex comprises 21 interconn ...

, as director of the American Eugenics Society

The American Eugenics Society (AES) was a pro-eugenics organization dedicated to "furthering the discussion, advancement, and dissemination of knowledge about biological and sociocultural forces which affect the structure and composition of huma ...

, vice president of the Immigration Restriction League

The Immigration Restriction League was an American nativist and anti-immigration organization founded by Charles Warren, Robert DeCourcy Ward, and Prescott F. Hall in 1894. According to Erika Lee, in 1894 the old stock Yankee upper-class f ...

, a founding member of the Galton Society, and one of the eight members of the International Committee of Eugenics. He was awarded the gold medal of the Society of Arts and Sciences in 1929. In 1931, the world's largest tree (in Dyerville, California) was dedicated to Grant, Merriam, and Osborn by the California State Board of Parks in recognition for their environmental efforts. A subspecies of caribou

The reindeer or caribou (''Rangifer tarandus'') is a species of deer with circumpolar distribution, native to Arctic, subarctic, tundra, boreal, and mountainous regions of Northern Europe, Siberia, and North America. It is the only represe ...

was named after Grant as well ('' Rangifer tarandus granti'', also known as Grant's Caribou). He was an early member of the Boone and Crockett Club

The Boone and Crockett Club is an American nonprofit organization that advocates fair chase hunting in support of habitat conservation. The club is North America's oldest wildlife and habitat conservation organization, founded in the United S ...

(a big game hunting

Hunting is the Human activity, human practice of seeking, pursuing, capturing, and killing wildlife or feral animals. The most common reasons for humans to hunt are to obtain the animal's body for meat and useful animal products (fur/hide (sk ...

and conservation organization) since 1893, and he mobilized its wealthy members to influence the government to conserve vast areas of land against encroaching industries. He was the head of the New York Zoological Society

New or NEW may refer to:

Music

* New, singer of K-pop group The Boyz

* ''New'' (album), by Paul McCartney, 2013

** "New" (Paul McCartney song), 2013

* ''New'' (EP), by Regurgitator, 1995

* "New" (Daya song), 2017

* "New" (No Doubt song), 1 ...

from 1925 until his death.

Grant's campaigns for conservationism and eugenics were not unrelated: both assumed the need for various types of stewardship over their charges. Grant was generally indifferent to forms of animal life that he did not regard as aristocratic, and assigned such a hierarchy to humans as well. Historian Jonathan Spiro wrote, "Whereas wildlife managers felt that the survival of the species as a whole was more important than the lives of a few individuals, so Grant preached that the fate of the race outweighed that of a few particular humans who were 'of no value to the community'." In Grant's mind, natural resources needed to be conserved for the "Nordic race" to the exclusion of other races. Grant viewed the Nordic race as he did any of his endangered species, and considered the modern industrial society as infringing just as much on its existence as it did on the redwoods. Like many eugenicists, Grant saw modern civilization as a violation of "survival of the fittest", whether it manifested itself in the over-logging of the forests, or the survival of the poor via welfare or charity. In the words of the ''New Yorker'', for figures such as Grant, "it was an unsettlingly short step from managing forests to managing the human gene pool".

Nordicism

Grant was the author of the once much-read book ''

Grant was the author of the once much-read book ''The Passing of the Great Race

''The Passing of the Great Race: Or, The Racial Basis of European History'' is a 1916 racist and pseudoscientific book by American lawyer, anthropologist, and proponent of eugenics Madison Grant (1865–1937). Grant expounds a theory of Nordi ...

'' (1916), an elaborate work of racial hygiene

The term racial hygiene was used to describe an approach to eugenics in the early 20th century, which found its most extensive implementation in Nazi Germany (Nazi eugenics). It was marked by efforts to avoid miscegenation, analogous to an anim ...

attempting to explain the racial history of Europe. The most significant of Grant's concerns was with the changing "stock" of American immigration of the early 20th century (characterized by increased numbers of immigrants from Southern Europe

Southern Europe is also known as Mediterranean Europe, as its geography is marked by the Mediterranean Sea. Definitions of southern Europe include some or all of these countries and regions: Albania, Andorra, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, C ...

and Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the Europe, European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural and socio-economic connotations. Its eastern boundary is marked by the Ural Mountain ...

, as opposed to Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's extent varies depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the Western half of the ancient Mediterranean ...

and Northern Europe

The northern region of Europe has several definitions. A restrictive definition may describe northern Europe as being roughly north of the southern coast of the Baltic Sea, which is about 54th parallel north, 54°N, or may be based on other ge ...

), ''Passing of the Great Race'' was a "racial" interpretation of contemporary anthropology and history, stating race as the basic motor of civilization.

Similar ideas were proposed by prehistorian Gustaf Kossinna in Germany. Grant promoted the idea of the "Nordic race

The Nordic race is an obsolete racial classification of humans based on a now-disproven theory of biological race. It was once considered a race or one of the putative sub-races into which some late-19th to mid-20th century anthropologists di ...

", a loosely defined biological-cultural grouping rooted in Scandinavia

Scandinavia is a subregion#Europe, subregion of northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and Sweden. It can sometimes also ...

, as the key social group responsible for human development; thus the subtitle of the book was ''The racial basis of European history''. As an avid eugenicist, Grant further advocated the separation, quarantine, and eventual collapse of "undesirable" traits and "worthless race types" from the human gene pool and the promotion, spread, and eventual restoration of desirable traits and "worthwhile race types" conducive to Nordic society. He wrote, "A rigid system of selection through the elimination of those who are weak or unfit—in other words social failures—would solve the whole question in one hundred years, as well as enable us to get rid of the undesirables who crowd our jails, hospitals, and insane asylums. The individual himself can be nourished, educated and protected by the community during his lifetime, but the state through sterilization must see to it that his line stops with him, or else future generations will be cursed with an ever increasing load of misguided sentimentalism. This is a practical, merciful, and inevitable solution of the whole problem, and can be applied to an ever widening circle of social discards, beginning always with the criminal, the diseased, and the insane, and extending gradually to types which may be called weaklings rather than defectives, and perhaps ultimately to worthless race types."

Grant's work is considered one of the most influential and vociferous works of scientific racism

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscience, pseudoscientific belief that the Human, human species is divided into biologically distinct taxa called "race (human categorization), races", and that empirical evi ...

and eugenics

Eugenics is a set of largely discredited beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter the frequency of various human phenotypes by inhibiting the fer ...

to come out of the United States. Stephen Jay Gould

Stephen Jay Gould ( ; September 10, 1941 – May 20, 2002) was an American Paleontology, paleontologist, Evolutionary biology, evolutionary biologist, and History of science, historian of science. He was one of the most influential and widely re ...

described ''The Passing of the Great Race'' as "the most influential tract of American scientific racism". ''The Passing of the Great Race'' was published in multiple printings in the United States, and was translated into other languages, including German in 1925. By 1937, the book had sold 16,000 copies in the United States alone.

The book was embraced by proponents of the Nazi

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right politics, far-right Totalitarianism, totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During H ...

movement in Germany and was the first non-German book ordered to be reprinted by the Nazis when they took power. Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

wrote to Grant, "The book is my Bible."

One of Grant's long-time opponents was the anthropologist Franz Boas

Franz Uri Boas (July 9, 1858 – December 21, 1942) was a German-American anthropologist and ethnomusicologist. He was a pioneer of modern anthropology who has been called the "Father of American Anthropology". His work is associated with the mov ...

. Grant disliked Boas and for several years tried to get him fired from his position at Columbia University

Columbia University in the City of New York, commonly referred to as Columbia University, is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Churc ...

. Boas and Grant were involved in a bitter struggle for control over the discipline of anthropology

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, society, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including archaic humans. Social anthropology studies patterns of behav ...

in the United States, while they both served (along with others) on the National Research Council Committee on Anthropology after the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

.

Grant represented the " hereditarian" branch of physical anthropology

Biological anthropology, also known as physical anthropology, is a natural science discipline concerned with the biological and behavioral aspects of human beings, their extinct hominin ancestors, and related non-human primates, particularly from ...

at the time, despite his relatively amateur status, and was staunchly opposed to and by Boas himself (and the latter's students), who advocated cultural anthropology

Cultural anthropology is a branch of anthropology focused on the study of cultural variation among humans. It is in contrast to social anthropology, which perceives cultural variation as a subset of a posited anthropological constant. The term ...

. Boas and his students eventually wrested control of the American Anthropological Association

The American Anthropological Association (AAA) is an American organization of scholars and practitioners in the field of anthropology. With 10,000 members, the association, based in Arlington, Virginia, includes archaeologists, cultural anthropo ...

from Grant and his supporters, who had used it as a flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of navy, naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically ...

organization for his brand of anthropology. In response, Grant, along with American eugenicist and biologist Charles B. Davenport, in 1918 founded the Galton Society as an alternative to Boas.

Immigration restriction

Grant advocated restricted immigration to the United States through limiting immigration from Eastern Europe and Southern Europe, as well as the complete end of immigration from East Asia. He also advocated efforts to purify the American population through selective breeding. He served as the vice president of the

Grant advocated restricted immigration to the United States through limiting immigration from Eastern Europe and Southern Europe, as well as the complete end of immigration from East Asia. He also advocated efforts to purify the American population through selective breeding. He served as the vice president of the Immigration Restriction League

The Immigration Restriction League was an American nativist and anti-immigration organization founded by Charles Warren, Robert DeCourcy Ward, and Prescott F. Hall in 1894. According to Erika Lee, in 1894 the old stock Yankee upper-class f ...

from 1922 to his death. Acting as an expert on world racial data, Grant also provided statistics for the Immigration Act of 1924

The Immigration Act of 1924, or Johnson–Reed Act, including the Asian Exclusion Act and National Origins Act (), was a United States federal law that prevented immigration from Asia and set quotas on the number of immigrants from every count ...

to set the quotas on immigrants from certain European countries. Even after passing the statute, Grant continued to be irked that even a smattering of non-Nordics were allowed to immigrate to the country each year. His support for anti-miscegenation laws was quoted in arguments for the Racial Integrity Act of 1924 in Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

.

Though Grant was extremely influential in legislating his view of racial theory, he began to fall out of favor in the United States in the early 1930s. The declining interest in his work has been attributed both to the effects of the Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

, which resulted in a general backlash against Social Darwinism

Charles Darwin, after whom social Darwinism is named

Social Darwinism is a body of pseudoscientific theories and societal practices that purport to apply biological concepts of natural selection and survival of the fittest to sociology, economi ...

and related philosophies, and to the changing dynamics of racial issues in the United States during the interwar period. Rather than subdivide Europe into separate racial groups, the bi-racial (black vs. white) views of Grant's protegé Lothrop Stoddard became more dominant in the aftermath of the Great Migration of African-Americans from Southern States to Northern and Western ones (Guterl 2001).

Legacy

According to historian of economics Thomas C. Leonard: "Prominent American eugenicists, including movement leaders Charles Davenport and Madison Grant, were conservatives. They identified fitness with social and economic position, and they also were hard hereditarians, dubious of the Lamarckian inheritance clung to by progressives. But as eugenicists, these conservatives were not classical liberals. Like all eugenicists, they were illiberal. Conservatives do not object to state coercion so long as it is used for what they regard as the right purposes, and these men were happy to trample on individual rights to obtain the greater good of improved hereditary health.... Historians invariably style Madison Grant a conservative, because he was a blueblood clubman from a patrician family, and his best- known work, ''The Passing of the Great Race'', is a museum piece of scientific racism. But Grant's eugenic ideas originated from a corner of the conservative impulse intimately connected to Progressivism: conservation." Leonard wrote that Grant also opposed war, had doubts about imperialism, and supportedbirth control

Birth control, also known as contraception, anticonception, and fertility control, is the use of methods or devices to prevent pregnancy. Birth control has been used since ancient times, but effective and safe methods of birth control only be ...

.

Leonard's view that eugenicists such as Grant were conservatives is an outlier, however. Writer Jonah Goldberg has noted that "eugenics lay at the heart of the progressive enterprise" and was embraced by almost all early progressives, from Margaret Sanger to H.G. Wells and John Maynard Keynes. Likewise, Thomas Sowell has noted that most leading eugenicists were firmly ensconced within progressive intellectual circles, where the desire for the government to take strong action to protect the gene pool went hand-in-hand with other statist views, including opposition to free-market capitalism. Similarly, historian Edwin Black has stated that the eugenic crusade was "created in the publications and academic research rooms of the Carnegie Institution, verified by the research grants of the Rockefeller Foundation, validated by leading scholars from the best Ivy League universities, and financed by the special efforts of the Harriman railroad fortune." From this perspective, it is perfectly understandable that Madison Grant—a graduate of elite Ivy League universities and a strong advocate for various progressive causes of the day—would also be a eugenicist.

Grant became a part of popular culture in 1920s America, especially in New York. Grant's conservationism and fascination with zoological natural history made him influential among the New York elite, who agreed with his cause, most notably Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. (October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), also known as Teddy or T.R., was the 26th president of the United States, serving from 1901 to 1909. Roosevelt previously was involved in New York (state), New York politics, incl ...

. Author F. Scott Fitzgerald featured a reference to Grant in ''The Great Gatsby

''The Great Gatsby'' () is a 1925 novel by American writer F. Scott Fitzgerald. Set in the Jazz Age on Long Island, near New York City, the novel depicts first-person narrator Nick Carraway's interactions with Jay Gatsby, a mysterious mi ...

''. Tom Buchanan, a fatuous Long Island aristocrat married to Daisy, was reading a book called ''The Rise of the Colored Empires'' by "this man Goddard", blending Grant's ''Passing of the Great Race'' and his colleague Lothrop Stoddard's '' The Rising Tide of Color Against White World Supremacy''.

Grant left no offspring when he died in 1937 of nephritis

Nephritis is inflammation of the kidneys and may involve the glomeruli, tubules, or interstitial tissue surrounding the glomeruli and tubules. It is one of several different types of nephropathy.

Types

* Glomerulonephritis is inflammation ...

. Several hundred people attended Grant's funeral, and he was buried in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery

Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Sleepy Hollow, New York, is the cemetery, final resting place of numerous famous figures, including Washington Irving, whose 1820 short story "The Legend of Sleepy Hollow" is set in the adjacent burying ground of the ...

in Tarrytown, New York

Tarrytown is a administrative divisions of New York#Village, village in the administrative divisions of New York#Town, town of Greenburgh, New York, Greenburgh in Westchester County, New York, Westchester County, New York (state), New York, Unit ...

. He left a bequest of $25,000 to the New York Zoological Society

New or NEW may refer to:

Music

* New, singer of K-pop group The Boyz

* ''New'' (album), by Paul McCartney, 2013

** "New" (Paul McCartney song), 2013

* ''New'' (EP), by Regurgitator, 1995

* "New" (Daya song), 2017

* "New" (No Doubt song), 1 ...

to create "The Grant Endowment Fund for the Protection of Wild Life", $5,000 to the American Museum of Natural History

The American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) is a natural history museum on the Upper West Side of Manhattan in New York City. Located in Theodore Roosevelt Park, across the street from Central Park, the museum complex comprises 21 interconn ...

, and another $5,000 to the Boone and Crockett Club

The Boone and Crockett Club is an American nonprofit organization that advocates fair chase hunting in support of habitat conservation. The club is North America's oldest wildlife and habitat conservation organization, founded in the United S ...

. Relatives destroyed his personal papers and correspondence after his death.

At the postwar

At the postwar Nuremberg Trials #REDIRECT Nuremberg trials

{{redirect category shell, {{R from other capitalisation{{R from move ...

, three pages of excerpts from Grant's ''Passing of the Great Race'' were introduced into evidence by the defense of Karl Brandt

Karl Brandt (8 January 1904 – 2 June 1948) was a German physician and ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS) officer in Nazi Germany. Trained in surgery, Brandt joined the Nazi Party in 1932 and became Adolf Hitler's escort doctor in August 1934. A member of ...

, Hitler's personal physician and head of the Nazi euthanasia program, in order to justify the population policies of the Third Reich, or at least indicate that they were not ideologically unique to Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

.

Grant's works of scientific racism

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscience, pseudoscientific belief that the Human, human species is divided into biologically distinct taxa called "race (human categorization), races", and that empirical evi ...

have been cited to demonstrate that many of the genocidal and eugenic ideas associated with the Third Reich did not arise specifically in Germany, and in fact that many of them had origins in other countries, including the United States. As such, because of Grant's well-connected and influential friends, he is often used to illustrate the strain of race-based eugenic thinking in the United States, which had some influence until the Second World War. Because of the use made of Grant's eugenics work by the policy-makers of Nazi Germany, his work as a conservationist has been somewhat ignored and obscured, as many organizations with which he was once associated (such as the Sierra Club

The Sierra Club is an American environmental organization with chapters in all 50 U.S. states, Washington, D.C., Washington D.C., and Puerto Rico. The club was founded in 1892, in San Francisco, by preservationist John Muir. A product of the Pro ...

) wanted to minimize their association with him. His racial theories, which were popularized in the 1920s, are today seen as discredited. The work of Franz Boas

Franz Uri Boas (July 9, 1858 – December 21, 1942) was a German-American anthropologist and ethnomusicologist. He was a pioneer of modern anthropology who has been called the "Father of American Anthropology". His work is associated with the mov ...

and his students, Ruth Benedict

Ruth Fulton Benedict (June 5, 1887 – September 17, 1948) was an American anthropologist and folklorist.

She was born in New York City, attended Vassar College, and graduated in 1909. After studying anthropology at the New School of Social ...

and Margaret Mead

Margaret Mead (December 16, 1901 – November 15, 1978) was an American cultural anthropologist, author and speaker, who appeared frequently in the mass media during the 1960s and the 1970s.

She earned her bachelor's degree at Barnard Col ...

, demonstrated that there were no inferior or superior races.

On June 15, 2021, California State Parks removed a memorial to Madison Grant from Prairie Creek Redwoods State Park placed in the park in 1948. The monument's removal is part of a broader effort in California Parks to address outdated exhibits and interpretations related to the founders of Save the Redwoods. In spring 2022, California State Parks will install a new interpretive panel, co-written with academic scholars, that tells a fuller story about Grant, his conservation legacy, and his central role in the eugenics movement.

Works

''The Caribou.''

New York: Office of the New York Zoological Society, 1902. * "Moose". New York: Report of the Forest, Fish, Game Commission, 1903.

''The Origin and Relationship of the Large Mammals of North America.''

New York: Office of the New York Zoological Society, 1904. *

The Rocky Mountain Goat.

' Office of the New York Zoological Society, 1905.

''The Passing of the Great Race; or, The Racial Basis of European History.''

New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1916. *

New ed.

rev. and Amplified, with a New Preface by Henry Fairfield Osborn. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1918 *

Rev. ed.

with a Documentary Supplement, and a Preface by Henry Fairfield Osborn. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1921. *

Fourth rev. ed.

with a Documentary Supplement, and a Preface by Henry Fairfield Osborn. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1936. *

Saving the Redwoods; an Account of the Movement During 1919 to Preserve the Redwoods of California

'' New York: Zoological Society, 1919.Reprinted i

''The National Geographic''

Vol. XXXVII, January/June, 1920.

''Early History of Glacier National Park, Montana.''

Washington: Govt. print. off., 1919.

''The Conquest of a Continent; or, The Expansion of Races in America''

Charles Scribner's Sons, 1933.

Selected articles

"The Depletion of American Forests"

''Century Magazine'', Vol. XLVIII, No. 1, May 1894.

"The Vanishing Moose, and their Extermination in the Adirondacks"

''Century Magazine'', Vol. XLVII, 1894.

"A Canadian Moose Hunt"

In: Theodore Roosevelt (ed.), ''Hunting in Many Lands.'' New York: Forest and Stream Publishing Company, 1895.

"The Future of Our Fauna"

''Zoological Society Bulletin'', No. 34, June 1909.

"History of the Zoological Society"

''Zoological Society Bulletin'', Decennial Number, No. 37, January 1910.

"Condition of Wild Life in Alaska"

In: ''Hunting at High Altitudes.'' New York: Harper & Brothers, Publishers, 1913.

"Wild Life Protection"

''Zoological Society Bulletin'', Vol. XIX, No. 1, January 1916.

"The Passing of the Great Race"

''Geographical Review'', Vol. 2, No. 5, Nov., 1916.

"The Physical Basis of Race"

''Journal of the National Institute of Social Sciences'', Vol. III, January 1917.

"Discussion of Article on Democracy and Heredity"

''The Journal of Heredity'', Vol. X, No. 4, April, 1919.

"Restriction of Immigration: Racial Aspects"

''Journal of the National Institute of Social Sciences'', Vol. VII, August 1921.

"Racial Transformation of America"

''The North American Review'', March 1924.

"America for the Americans"

''The Forum'', September 1925.

See also

*Eugenics in the United States

Eugenics, the set of beliefs and practices which aims at improving the Genetics, genetic quality of the human population, played a significant role in the history and culture of the United States from the late 19th century into the mid-20th c ...

* Institutional racism

Institutional racism, also known as systemic racism, is a form of institutional discrimination based on Race (human categorization), race or ethnic group and can include policies and practices that exist throughout a whole society or organizati ...

* Henry Fairfield Osborn

* Racism

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one Race (human categorization), race or ethnicity over another. It may also me ...

References

Further reading

* Allen, Garland E. (2013). "'Culling the Herd': Eugenics and the Conservation Movement in the United States, 1900-1940". ''Journal of the History of Biology'' 46, pp. 31–72. * Barkan, Elazar (1992). ''The Retreat of Scientific Racism: Changing Concepts of Race in Britain and the United States between the World Wars''. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. * Cooke, Kathy J. (2000)"Grant, Madison"

''American National Biography''. Oxford University Press. Online. * Degler, Carl N. (1991). ''In Search of Human Nature: The Decline and Revival of Darwinism in American Social Thought''. Oxford University Press. * Field, Geoffrey G. (1977). "Nordic Racism", ''Journal of the History of Ideas'' 38 (3), pp. 523–540. * Guterl, Matthew Press (2001). ''The Color of Race in America, 1900–1940''. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. * Lee, Erika. "America first, immigrants last: American xenophobia then and now." ''Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era'' 19.1 (2020): 3-18. * Leonard, Thomas C. ''Illiberal Reformers: Race, Eugenics, and American Economics in the Progressive Era'' (Princeton UP, 2016). * Leonard, Thomas C

More Merciful and Not Less Effective': Eugenics and American Economics in the Progressive Era"

''History of Political Economy'' 35.4 (2003): 687-712. * Marcus, Alan P. "The Dangers of the Geographical Imagination in the US Eugenics Movement". ''Geographical Review'' 111.1 (2021): 36-56. * Purdy, Jedediah (2015)

"Environmentalism's Racist History"

''

The New Yorker

''The New Yorker'' is an American magazine featuring journalism, commentary, criticism, essays, fiction, satire, cartoons, and poetry. It was founded on February 21, 1925, by Harold Ross and his wife Jane Grant, a reporter for ''The New York T ...

''.

*

* Spiro, Jonathan P. ''Defending the Master Race: Conservation, Eugenics, and the Legacy of Madison Grant'' (Univ. of Vermont Press, 2009Excerpt

* Spiro, Jonathan P. "Nordic vs. Anti-Nordic: The Galton Society and the American Anthropological Association", ''Patterns of Prejudice'' 36#1 (2002): 35–48. * Regal, Brian (2002). ''Henry Fairfield Osborn: Race and the Search for the Origins of Man''. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate. * Regal, Brian (2004). "Maxwell Perkins and Madison Grant: Eugenics Publishing at Scribners", ''Princeton University Library Chronicle'' 65#2, pp. 317–341.

External links

*Excerpts from ''Passing of the Great Race'' used at the Nuremberg Trials

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Grant, Madison 1865 births 1937 deaths 20th-century American lawyers 20th-century American writers 20th-century American anthropologists Amateur anthropologists American conservationists American conspiracy theorists American Eugenics Society members American hunters American people of English descent American people of French descent American political writers American white nationalists American white supremacists American zoologists Burials at Sleepy Hollow Cemetery Columbia Law School alumni Deaths from nephritis Lawyers from New York City Nordicism Philanthropists from New York (state) People involved in race and intelligence controversies Proponents of scientific racism Writers from New York City Yale University alumni