MacRobertson Race on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

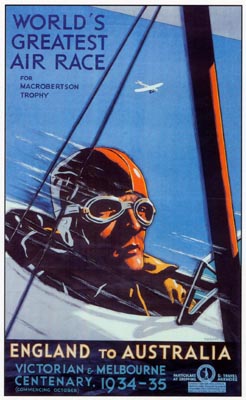

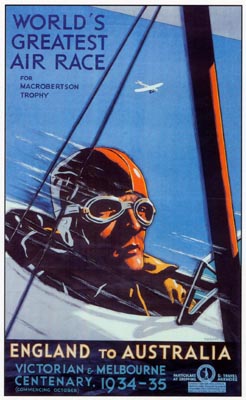

The MacRobertson Trophy Air Race (also known as the London to Melbourne Air Race) took place in October

The basic rules were: no limit to the size of aircraft or power, no limit to crew size, and no pilot to join the aircraft after it had left England. Aircraft had to carry three days' rations per crew member, floats (e.g. buoyancy aids or

The basic rules were: no limit to the size of aircraft or power, no limit to crew size, and no pilot to join the aircraft after it had left England. Aircraft had to carry three days' rations per crew member, floats (e.g. buoyancy aids or  Significantly, both second and third quickest times were taken by airliners, the

Significantly, both second and third quickest times were taken by airliners, the  During the race, the ''Uiver'', low on fuel after the crew had become lost when caught in severe thunderstorms, ended up over

During the race, the ''Uiver'', low on fuel after the crew had become lost when caught in severe thunderstorms, ended up over

MacRobertson Air Race - State Library of NSW

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20040604024806/http://www.pjcomputing.flyer.co.uk/comet/ Comet DH88 - fastest from England to Australia

''The Great Air Race'', a TV Movie about MacRobertson Air Race

The Uiver Collection, Albury NSW

Tom Campbell Black co-winner of the MacRobertson London to Melbourne Air Race 1934

{{DEFAULTSORT:Macrobertson Air Race Air races Air sports in the United Kingdom Aviation in Victoria (state) Aviation history of the United Kingdom 1934 in Australian sport 1934 in aviation Articles containing video clips 1934 in Australia 1934 in London 1930s in Melbourne Air France–KLM

1934

Events

January–February

* January 1 – The International Telecommunication Union, a specialist agency of the League of Nations, is established.

* January 15 – The 8.0 1934 Nepal–Bihar earthquake, Nepal–Bihar earthquake strik ...

as part of the Melbourne Centenary celebrations. The race was devised by the Lord Mayor of Melbourne

Melbourne ( , ; Boonwurrung language, Boonwurrung/ or ) is the List of Australian capital cities, capital and List of cities in Australia by population, most populous city of the States and territories of Australia, Australian state of Victori ...

, Sir Harold Gengoult Smith, and the prize money of £15,000 was provided by Sir Macpherson Robertson

Sir Macpherson Robertson Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire, KBE (6 September 185920 August 1945) was an Australian philanthropist, entrepreneur and founder of chocolate and confectionery company ''MacRobertson's''.

He was als ...

, a wealthy Australian confectionery manufacturer, on the conditions that the race be named after his MacRobertson confectionery company, and that it was organised to be as safe as possible. A further condition was that a gold medal be awarded to each pilot who completed the course within 16 days.

Organisation and rules

The race was organised by an Air Race Committee, with representatives from the Australian government, aviation, and Melbourne Centenary authorities. TheRoyal Aero Club

The Royal Aero Club (RAeC) is the national co-ordinating body for air sport in the United Kingdom. It was founded in 1901 as the Aero Club of Great Britain, being granted the title of the "Royal Aero Club" in 1910.

History

The Aero Club was foun ...

oversaw the event. The race ran from RAF Mildenhall

Royal Air Force Mildenhall, or more simply RAF Mildenhall , is a Royal Air Force List of Royal Air Force stations, station located near Mildenhall, Suffolk, Mildenhall in Suffolk, England. Despite its status as a List of Royal Air Force stations, ...

in East Anglia

East Anglia is an area of the East of England, often defined as including the counties of Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire, with parts of Essex sometimes also included.

The name derives from the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the East Angles, ...

to Flemington Racecourse

Flemington Racecourse is a major horse racing venue located in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. It is most notable for hosting the Melbourne Cup, which is the world's richest handicap and the world's richest 3200-metre horse race. The race ...

, Melbourne, approximately . There were five compulsory stops, at Baghdad

Baghdad ( or ; , ) is the capital and List of largest cities of Iraq, largest city of Iraq, located along the Tigris in the central part of the country. With a population exceeding 7 million, it ranks among the List of largest cities in the A ...

, Allahabad

Prayagraj (, ; ISO 15919, ISO: ), formerly and colloquially known as Allahabad, is a metropolis in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh.The other five cities were: Agra, Kanpur, Kanpur (Cawnpore), Lucknow, Meerut, and Varanasi, Varanasi (Benar ...

, Singapore

Singapore, officially the Republic of Singapore, is an island country and city-state in Southeast Asia. The country's territory comprises one main island, 63 satellite islands and islets, and one outlying islet. It is about one degree ...

, Darwin, and Charleville, Queensland

Charleville () is a rural town and Suburbs and localities (Australia), locality in the Shire of Murweh, Queensland, Australia. In the , the locality of Charleville had a population of 2,992.

Geography

Located in southwestern Queensland, Aust ...

; otherwise the competitors could choose their own routes. A further 22 optional stops were provided with stocks of fuel and oil provided by Shell

Shell may refer to:

Architecture and design

* Shell (structure), a thin structure

** Concrete shell, a thin shell of concrete, usually with no interior columns or exterior buttresses

Science Biology

* Seashell, a hard outer layer of a marine ani ...

and Stanavo. The Royal Aero Club put some effort into persuading the countries along the route to improve the facilities at the stopping points.

The basic rules were: no limit to the size of aircraft or power, no limit to crew size, and no pilot to join the aircraft after it had left England. Aircraft had to carry three days' rations per crew member, floats (e.g. buoyancy aids or

The basic rules were: no limit to the size of aircraft or power, no limit to crew size, and no pilot to join the aircraft after it had left England. Aircraft had to carry three days' rations per crew member, floats (e.g. buoyancy aids or personal flotation device

A personal flotation device (PFD; also referred to as a life jacket, life preserver, life belt, Mae West, life vest, life saver, cork jacket, buoyancy aid or flotation suit) is a flotation device in the form of a vest or suit that is worn by a u ...

s), smoke signals, and efficient instruments. There were prizes for the outright fastest aircraft (£10,000 and a trophy, £1,500 and £500) and for the best performance on a handicap formula (£2000 and £1000) by any aircraft finishing within 16 days.

The start was set at dawn (6:30) on 20 October 1934. By then, the initial field of over 60 had been reduced to 20, including three purpose-built de Havilland DH.88 Comet racers, two of the new generation of American all-metal airliners, and a mixture of earlier racers, light transports, and old bombers.

First off the line, watched by a crowd of 60,000, were Jim Mollison

James Allan Mollison MBE (19 April 1905 – 30 October 1959) was a Scottish pioneer aviator who, flying solo or with his wife, Amy Johnson, set many records during the rapid development of aviation in the 1930s.

Early years

Mollison wa ...

and his wife Amy Johnson

Amy Johnson (born 1 July 1903 – disappeared 5 January 1941) was a pioneering English pilot who was the first woman to fly solo from London to Australia.

Flying solo or with her husband, Jim Mollison, she set many long-distance records dur ...

in the Comet ''Black Magic'', and they were early leaders in the race until forced to retire at Allahabad with engine trouble. This left the DH.88 ''Grosvenor House'' flown by Flight lieutenant C. W. A. Scott

Flight Lieutenant Charles William Anderson Scott, Air Force Cross (United Kingdom), AFC (13 February 1903 – 15 April 1946Dunnell ''Aeroplane'', November 2019, p. 46.) was an English aviator. He won the MacRobertson Air Race, a race from Londo ...

and Captain Tom Campbell Black

Tom Campbell Black (December 1899 – 19 September 1936) was an English aviator.

He was the son of Alice Jean McCullough and Hugh Milner Black. He became a world-famous aviator when he and C. W. A. Scott won the London to Melbourne Centenary ...

well ahead of the rest of field, and they went on to win in a time of less than three days, despite flying the last stage with one engine throttled back because of an oil-pressure indicator giving a faulty low reading. They would have also won the handicap prize, but the race rules stipulated that no aircraft could win more than one prize. For their efforts the Royal Aeronautical Society

The Royal Aeronautical Society, also known as the RAeS, is a British multi-disciplinary professional institution dedicated to the global aerospace community. Founded in 1866, it is the oldest Aeronautics, aeronautical society in the world. Memb ...

awarded them the silver medal for Aeronautics.

Significantly, both second and third quickest times were taken by airliners, the

Significantly, both second and third quickest times were taken by airliners, the KLM

KLM Royal Dutch Airlines, or simply KLM (an abbreviation for their official name Koninklijke Luchtvaart Maatschappij N.V. , ),

Douglas DC-2

The Douglas DC-2 is a retired 14-passenger, twin-engined airliner that was produced by the American company Douglas Aircraft Company starting in 1934. It competed with the Boeing 247. In 1935, Douglas produced a larger version called the DC-3 ...

PH-AJU ''Uiver'' ("Stork") and Roscoe Turner

Roscoe Turner (September 29, 1895 – June 23, 1970) was a record-breaking American aviator who was a three-time winner of the Thompson Trophy air race and widely recognized by his flamboyant style and his pet, Gilmore the lion, Gilmore the L ...

's Boeing 247

The Boeing Model 247 is an early American airliner, and one of the first such aircraft to incorporate advances such as all-metal ( anodized aluminum) semimonocoque construction, a fully cantilevered wing, and retractable landing gear.

D. Both completed the course in less than a day more than the winner; KLM's DC-2 was even flying a regular route with passengers.

During the race, the ''Uiver'', low on fuel after the crew had become lost when caught in severe thunderstorms, ended up over

During the race, the ''Uiver'', low on fuel after the crew had become lost when caught in severe thunderstorms, ended up over Albury

Albury (; ) is a major regional city that is located in the Murray River, Murray region of New South Wales, Australia. It is part of the twin city of Albury–Wodonga, Albury-Wodonga and is located on the Hume Highway and the northern side of ...

, New South Wales

New South Wales (commonly abbreviated as NSW) is a States and territories of Australia, state on the Eastern states of Australia, east coast of :Australia. It borders Queensland to the north, Victoria (state), Victoria to the south, and South ...

. Lyle Ferris, the chief electrical engineer of the post office, went to the power station and signalled "A-L-B-U-R-Y" to the aircraft in Morse code by turning the town street lights on and off. Arthur Newnham, the announcer on radio station 2CO Corowa appealed for cars to line up on the racecourse to light up a makeshift runway.

The ''Uiver'' landed successfully, and next morning was pulled out of the mud by locals to fly on to Melbourne and win the handicap section of the race, coming second overall. In gratitude KLM made a large donation to Albury District Hospital and Alf Waugh, the Mayor of Albury

Mayors of City of Albury, Albury, a city and Local government in New South Wales, local government area in the Riverina region of New South Wales, Australia.

Mayors of Albury Town of Albury

City of Albury

Albury was proclaimed a city in ...

, was awarded an Officer of the Order of Orange-Nassau

The Order of Orange-Nassau () is a civil and military Dutch order of chivalry founded on 4 April 1892 by the queen regent, Emma of the Netherlands.

The order is a chivalric order open to "everyone who has performed acts of special merits for ...

.

Later that year the DC-2, on a flight from The Netherlands to Batavia, crashed in the Syrian desert near Rutbah Wells in western Iraq, killing all seven on board; it is commemorated by a flying replica.

Comet G-ACSR promptly flew film of the race back to Britain setting a round trip record of 13 days 6 hr 43 min.Lewis, Peter. ''British Racing and Record Breaking Aircraft''. London: Putnam, 1970. . p272

The race was the basis for a 1991 Australian television miniseries ''The Great Air Race''.

Competitors

See also

*England to Australia flight

The 1919 England to Australia flight, also known as The Great Air Race, was the first ever flight from the United Kingdom to Australia. Of the six entries that started the race, the winners were South Australian brothers Ross Smith and Keith ...

Notes

References

*Lewis, Peter. 1970. British Racing and Record-Breaking Aircraft. Putnam *Further reading

*External links

MacRobertson Air Race - State Library of NSW

* ttps://web.archive.org/web/20040604024806/http://www.pjcomputing.flyer.co.uk/comet/ Comet DH88 - fastest from England to Australia

''The Great Air Race'', a TV Movie about MacRobertson Air Race

The Uiver Collection, Albury NSW

Tom Campbell Black co-winner of the MacRobertson London to Melbourne Air Race 1934

{{DEFAULTSORT:Macrobertson Air Race Air races Air sports in the United Kingdom Aviation in Victoria (state) Aviation history of the United Kingdom 1934 in Australian sport 1934 in aviation Articles containing video clips 1934 in Australia 1934 in London 1930s in Melbourne Air France–KLM