Mabel Russell on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Mabel Philipson (née Russell; 2 January 1886 – 9 January 1951), known as Mrs Hilton Philipson when not on the stage, was a British actress and politician. Having starred in multiple plays in London, including a period as a Gaiety Girl, Philipson left acting to marry Hilton Philipson in 1917. Her husband stood for the

After leaving school Philipson found work in a Clapham Junction theatre box office before taking on a role in a play. She understudied for a lead

After leaving school Philipson found work in a Clapham Junction theatre box office before taking on a role in a play. She understudied for a lead

National Liberal

National liberalism is a variant of liberalism, combining liberal policies and issues with elements of nationalism. Historically, national liberalism has also been used in the same meaning as conservative liberalism (right-liberalism).

A serie ...

party in the 1922 general election and although he was successful, the result was declared void. Philipson ran for the Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

party in the subsequent by-election in 1923, securing a larger majority than her husband did. In doing so, she became the third woman to take a seat in the House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the Bicameralism, bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of ...

after it became legally possible in 1918, as Member of Parliament (MP) for Berwick-upon-Tweed

Berwick-upon-Tweed (), sometimes known as Berwick-on-Tweed or simply Berwick, is a town and civil parish in Northumberland, England, south of the Anglo-Scottish border, and the northernmost town in England. The 2011 United Kingdom census recor ...

.

Philipson did not enjoy speaking in Parliament, so focused her energies on committee work and in her constituency

An electoral (congressional, legislative, etc.) district, sometimes called a constituency, riding, or ward, is a geographical portion of a political unit, such as a country, state or province, city, or administrative region, created to provi ...

. She was part of a parliamentary delegation to Italy 1924, meeting Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

, who described her as "la bella Russell". In 1927, she submitted a private member's bill

A private member's bill is a bill (proposed law) introduced into a legislature by a legislator who is not acting on behalf of the executive branch. The designation "private member's bill" is used in most Westminster system jurisdictions, in wh ...

that subsequently passed as the Nursing Homes Registration Act 1927

Nursing is a health care profession that "integrates the art and science of caring and focuses on the protection, promotion, and optimization of health and human functioning; prevention of illness and injury; facilitation of healing; and alle ...

. Philipson retired from politics in 1929, when her husband left politics to focus on his business, stating that "the reason why I have held the seat has ceased to exist". She returned to acting for a period, before leaving that profession to focus on her children.

Early life

Philipson was born Mabel Russell on 2 January 1886,There is some doubt regarding Philipson's birthdate, sources vary between 1886 and 1887 and also 1 or 2 January. at 1 Copeland Avenue,Peckham

Peckham ( ) is a district in south-east London, within the London Borough of Southwark. It is south-east of Charing Cross. At the 2001 Census the Peckham ward had a population of 14,720.

History

"Peckham" is a Saxon place name meaning the vi ...

. She was the eldest of three children of Albert Russell, a travelling sales representative from Birmingham

Birmingham ( ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in the metropolitan county of West Midlands (county), West Midlands, within the wider West Midlands (region), West Midlands region, in England. It is the Lis ...

and Alice Russell (née Shaw), a dressmaker. Due to the travelling nature of her father's role, Philipson helped to raise her siblings when her mother died in 1898.

Acting career

After leaving school Philipson found work in a Clapham Junction theatre box office before taking on a role in a play. She understudied for a lead

After leaving school Philipson found work in a Clapham Junction theatre box office before taking on a role in a play. She understudied for a lead pantomime

Pantomime (; informally panto) is a type of musical comedy stage production designed for family entertainment, generally combining gender-crossing actors and topical humour with a story more or less based on a well-known fairy tale, fable or ...

actress, and took on the role when the leading lady became ill. This break led to a number of other roles, including becoming a Gaiety Girl at the London Gaiety Theatre where she was given a role in ''Havana

Havana (; ) is the capital and largest city of Cuba. The heart of La Habana Province, Havana is the country's main port and commercial center. before taking on the role of Fifi in the 1907 London opening production of ''

Hilton Philipson was elected as the

Hilton Philipson was elected as the

In February 1911, Philipson married Thomas Stanley Rhodes, nephew of

In February 1911, Philipson married Thomas Stanley Rhodes, nephew of

Merry Widow

''The Merry Widow'' ( ) is an operetta by the Austria-Hungary, Austro-Hungarian composer Franz Lehár. The Libretto, librettists, Viktor Léon and Leo Stein (writer), Leo Stein, based the story – concerning a rich widow, and her countrymen's ...

''. In 1913, Philipson took on a role in '' Within The Law'', a drama as recommended by Sir Herbert Tree. She was considered for the role of Eliza Doolittle

Eliza Doolittle is a fictional character and the protagonist in George Bernard Shaw's play '' Pygmalion'' (1913) and its 1956 musical adaptation, ''My Fair Lady''.

Eliza (from Lisson Grove, London) is a Cockney flower seller, who comes to Prof ...

in '' Pygmalion'', but ultimately could not take it on due to contractual obligations. Instead she was the triumphant leading actress in the 1916 play, '' London Pride'', produced by Frank Curzon

Frank Curzon (17 September 1868 – 2 July 1927) was an English actor who became an important theatre manager, leasing the Royal Strand Theatre, Playhouse Theatre, Avenue Theatre, Criterion Theatre, Comedy Theatre, Prince of Wales Theatre and W ...

and Gerald du Maurier

Sir Gerald Hubert Edward Busson du Maurier (26 March 1873 – 11 April 1934) was an English actor and Actor-manager, manager. He was the son of author George du Maurier and his wife, Emma Wightwick, and the brother of Sylvia Llewelyn Davies ...

, to positive reviews.

In 1916, Philipson decided to take a break from acting, eventually leaving it as a career when she married her second husband, Hilton Philipson. However, in 1925 she returned to acting in a midnight benefit for Middlesex Hospital

Middlesex Hospital was a teaching hospital located in the Fitzrovia area of London, England. First opened as the Middlesex Infirmary in 1745 on Windmill Street, it was moved in 1757 to Mortimer Street where it remained until it was finally clos ...

and again for a run of a musical version '' The Beloved Vagabond'' during the parliamentary recess of 1927. For each role, she remained known by her maiden name, Mabel Russell.

After retiring from politics in 1929, Philipson returned to her acting career, with one significant film role in '' Tilly of Bloomsbury''. There, she regularly referred to the director as " Mr. Speaker", to his surprise. Philipson's final performance was a run in '' Other People's Lives'' in 1933 at Wyndham's Theatre

Wyndham's Theatre is a West End theatre, one of two opened by actor/manager Charles Wyndham (the other is the Criterion Theatre). Located on Charing Cross Road in the City of Westminster, it was designed c. 1898 by W. G. R. Sprague, the arch ...

.

Political career

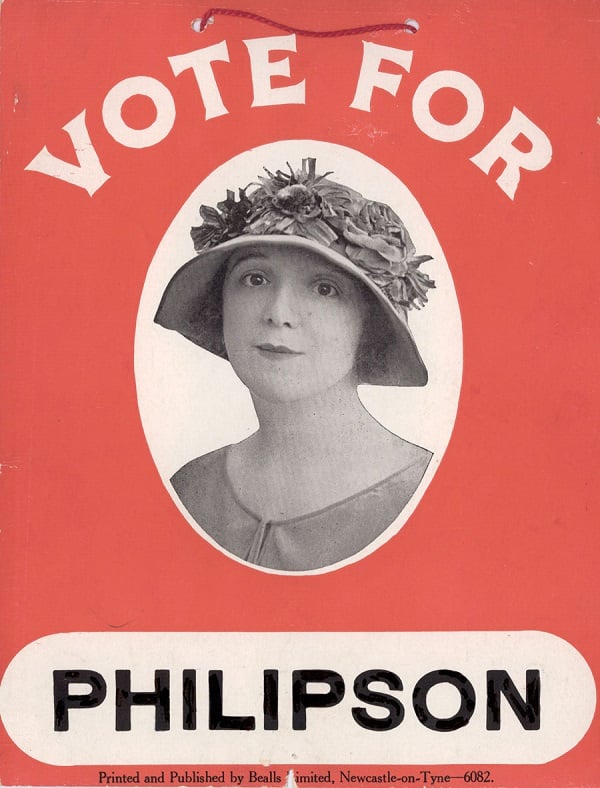

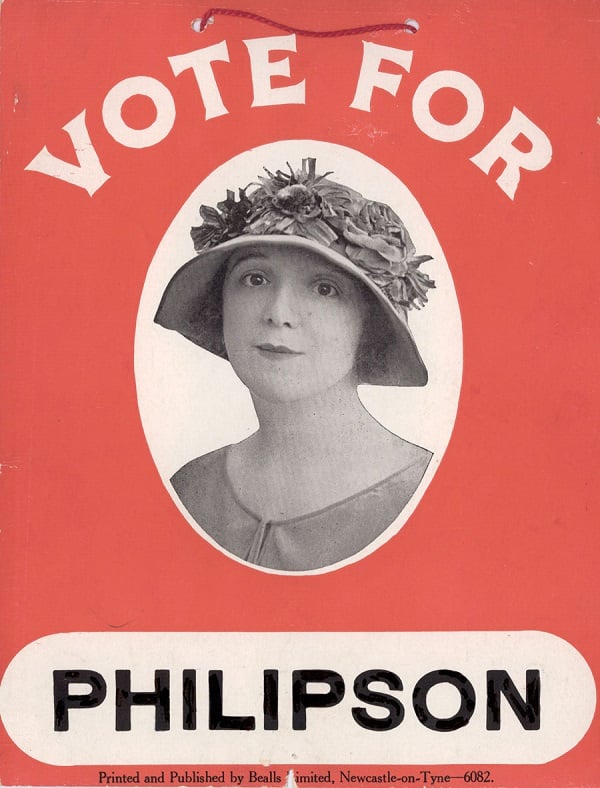

Election

Hilton Philipson was elected as the

Hilton Philipson was elected as the National Liberal

National liberalism is a variant of liberalism, combining liberal policies and issues with elements of nationalism. Historically, national liberalism has also been used in the same meaning as conservative liberalism (right-liberalism).

A serie ...

party's Member of Parliament for Berwick-upon-Tweed

Berwick-upon-Tweed (), sometimes known as Berwick-on-Tweed or simply Berwick, is a town and civil parish in Northumberland, England, south of the Anglo-Scottish border, and the northernmost town in England. The 2011 United Kingdom census recor ...

in the 1922 general election. He was, however, unseated on petition in 1923, due to campaign violations involving his agent. Although he was personally exonerated, he was also barred from standing in the constituency for seven years. Mabel Philipson agreed to stand in the resulting by-election, but only as a Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

. Philipson was considered a natural campaigner, who would court the press, blow kisses to the crowd and sign autographs. She was quick witted with heckler

A heckler is a person who harasses and tries to disconcert others with questions, challenges, or gibes. Hecklers are often known to shout discouraging comments at a performance or event, or to interrupt set-piece speeches, with the intent of d ...

s and her theatrical training made her an excellent public speaker, so even after her election she would carry on speaking at political rallies. Philipson was also happy to canvass the more deprived areas of Berwick, bringing up members of the public to join her for press photographs.

Also standing in the by-election were Harold Burge Robson

Hon. Harold Burge Robson (10 March 1888 – 13 October 1964) was a British soldier, barrister and Liberal Party politician.

Background

Robson was born the son of former Liberal Minister Lord Robson. He was educated at Eton and New College, Oxfo ...

for the Liberal party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world.

The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left. For example, while the political systems ...

and Gilbert Oliver for the Labour party. There was significant interest in speeches from the candidates, so the Mayor had to allocate the Town Hall steps to each party on different nights. During the election the MPs Margaret Wintringham

Margaret Wintringham (née Longbottom; 4 August 1879 – 10 March 1955) was a British Liberal Party politician. She was the second woman, and the first British-born woman, to take her seat in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom.

Early ...

and Nancy Astor

Nancy Witcher Astor, Viscountess Astor (19 May 1879 – 2 May 1964) was an American-born British politician who was the first woman seated as a Member of Parliament (MP), serving from 1919 to 1945. Astor was born in Danville, Virginia and rai ...

, as well as Philipson, were named at "Piety, Sobriety and Variety". Philipson won the by-election, taking the seat that the Liberal party had held for 37 years since the Redistribution of Seats Act 1885

The Redistribution of Seats Act 1885 (48 & 49 Vict. c. 23) was an Act of Parliament (United Kingdom), act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom (sometimes called the "Reform Act of 1885"). It was a piece of electoral reform legislation that r ...

. Her majority was over 6000, larger than her husband's the previous year.Mabel Philipson received 12,000 votes in the by-election, followed by Harold Burge Robson

Hon. Harold Burge Robson (10 March 1888 – 13 October 1964) was a British soldier, barrister and Liberal Party politician.

Background

Robson was born the son of former Liberal Minister Lord Robson. He was educated at Eton and New College, Oxfo ...

who received 5,858 and Gilbert Oliver who received 3,966 – a majority of 6,142. In the ''Dundee Courier & Argus

''The Courier'' (known as ''The Courier & Advertiser'' between 1926 and 2012) is a newspaper published by DC Thomson in Dundee, Scotland. As of 2013, it is printed in six regional editions: Dundee, Angus & The Mearns, Fife, West Fife, Perths ...

'', her success put down to "local conditions, sympathy with Captain Philipson, and resentment at his unseating", while she herself attributed it to the support of women and ex-service men.

Thousands attended the announcement of the results on 31 May 1922, enthusiastically cheering despite the High Sheriff's appeals for quiet while the numbers were being announced. Philipson was unable to speak after the result, having developed a sore throat during the campaign, she was escorted by six police bodyguards back to the Conservative Committee Rooms, where she appeared at the window and her husband expressed her thanks on her behalf. Philipson was then escorted through the crowds to her hotel but was accidentally elbowed by a policeman trying to make a passage through, resulting in a black eye

A periorbital hematoma, commonly called a black eye or a shiner (associated with boxing or stick sports such as hockey), is bruising around the eye commonly due to an injury to the face rather than to the eye. The name refers to the dark-colo ...

.

Time in Parliament

On 7 June 1923, Philipson became the third woman to take a seat in Parliament, nearly five years after theParliament (Qualification of Women) Act 1918

The Parliament (Qualification of Women) Act 1918 is an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It gave women over 21 the right to stand for election as a Member of Parliament.

At 41 words, it is the shortest UK statute.

Background

The ...

had been given Royal assent

Royal assent is the method by which a monarch formally approves an act of the legislature, either directly or through an official acting on the monarch's behalf. In some jurisdictions, royal assent is equivalent to promulgation, while in othe ...

. When she entered the House of Commons for the first time, she was surrounded by the Members of Parliament from both sides who congratulated her. As debate was ongoing, the Speaker

Speaker most commonly refers to:

* Speaker, a person who produces speech

* Loudspeaker, a device that produces sound

** Computer speakers

Speaker, Speakers, or The Speaker may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* "Speaker" (song), by David ...

had to actively call the House to order.

Philipson signed the roll, shook the Speaker's hand and then joined the other two women in Parliament for a long conversation. The gallery was full of ladies watching Philipson taking her seat. During the signing, there were a few comments from other members reportedly in good humour, including a call of "Cheer up, Mabel", a sarcastic "Good old National Liberals" – who had previously held her seat and a comment that Nancy Astor would soon be "on the dole

On, on, or ON may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Music

* On (band), a solo project of Ken Andrews

* ''On'' (EP), a 1993 EP by Aphex Twin

* ''On'' (Echobelly album), 1995

* ''On'' (Gary Glitter album), 2001

* ''On'' (Imperial Teen album), 200 ...

".

While sitting in Parliament, Philipson took a particular interest in housing, agriculture, infant welfare and women's issues. Although each woman of the time spoke more than the average man in Parliament, Philipson herself disliked parliamentary speaking, instead focussing on her constituency and committee work. She was part of the Joint Select Committee regarding Guardianship of Infants Bill 1923.

She joined the Air Committee in 1925.

In 1924, Philipson was part of a parliamentary delegation to Italy, where she was the only woman on the trip. There she met Pope Pius XI

Pope Pius XI (; born Ambrogio Damiano Achille Ratti, ; 31 May 1857 – 10 February 1939) was head of the Catholic Church from 6 February 1922 until his death in February 1939. He was also the first sovereign of the Vatican City State u ...

and Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

. Mussolini had previously expressed amusement at the idea of women in Parliament, referring to Philipson as "la bella Russell".

In 1927, Philipson began a movement for stricter registration of nursing homes

A nursing home is a facility for the residential care of older people, senior citizens, or disabled people. Nursing homes may also be referred to as care homes, skilled nursing facilities (SNF), or long-term care facilities. Often, these terms ...

, and when she drew the ballot to present a private member's bill

A private member's bill is a bill (proposed law) introduced into a legislature by a legislator who is not acting on behalf of the executive branch. The designation "private member's bill" is used in most Westminster system jurisdictions, in wh ...

, she chose to present the Nursing Homes Registration Act 1927

Nursing is a health care profession that "integrates the art and science of caring and focuses on the protection, promotion, and optimization of health and human functioning; prevention of illness and injury; facilitation of healing; and alle ...

requiring nursing homes to register and ensuring that they would be regularly inspected.

Outside of Parliament, she was 1927 Vice President of the Electric Association for Women, a member of the Women's Engineering Society

The Women's Engineering Society is a United Kingdom professional learned society and networking body for women engineers, scientists and technologists. It was the first professional body set up for women working in all areas of engineering, pred ...

and life governor of the Middlesex Hospital

Middlesex Hospital was a teaching hospital located in the Fitzrovia area of London, England. First opened as the Middlesex Infirmary in 1745 on Windmill Street, it was moved in 1757 to Mortimer Street where it remained until it was finally clos ...

.

Retirement

Throughout her time in office, Philipson considered her seat to be held until her husband could return, and would not step down unless he could be considered in her place. Her husband acknowledged that she wanted to focus on being a mother in 1924, but she remained in Parliament until she announced her resignation in 1928. Philipson cited her young family as one of the main reasons for leaving, but also that her husband had decided to move away from politics and focus on his business work due to the effect of coal disputes and residual costs from his unseating. Philipson's own summation was "the reason why I have held the seat has ceased to exist".Personal life

In February 1911, Philipson married Thomas Stanley Rhodes, nephew of

In February 1911, Philipson married Thomas Stanley Rhodes, nephew of Cecil Rhodes

Cecil John Rhodes ( ; 5 July 185326 March 1902) was an English-South African mining magnate and politician in southern Africa who served as Prime Minister of the Cape Colony from 1890 to 1896. He and his British South Africa Company founded th ...

. Less than six months later, in August, Stanley Rhodes was killed in a car crash near Brooklands

Brooklands was a motor racing circuit and aerodrome built near Weybridge in Surrey, England, United Kingdom. It opened in 1907 and was the world's first purpose-built 'banked' motor racing circuit as well as one of Britain's first airfields, ...

racing circuit. Philipson was also injured in the same accident, losing her vision in one eye.

In 1917 she married Hilton Philipson, then a lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a Junior officer, junior commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations, as well as fire services, emergency medical services, Security agency, security services ...

in the Scots Guards

The Scots Guards (SG) is one of the five Foot guards#United Kingdom, Foot Guards regiments of the British Army. Its origins are as the personal bodyguard of King Charles I of England and Scotland. Its lineage can be traced back to 1642 in the Ki ...

, and had three children, twin sons and a daughter. One of her sons died soon after childbirth. Hilton Philipson left the Scots Guards as a captain, becoming a director of the North Eastern Railway Company

The North Eastern Railway (NER) was an English railway company. It was incorporated in 1854 by the combination of several existing railway companies. Later, it was amalgamated with other railways to form the London and North Eastern Railwa ...

. Philipson announced her retirement from both politics in 1929 and acting in 1933, to focus on looking after her children. Her husband died in 1941 at the age of 48 at Vale Royal Abbey

Vale Royal Abbey is a former England in the Middle Ages, medieval abbey and later country house in Whitegate, Cheshire, Whitegate, England. The precise location and boundaries of the abbey are difficult to determine in today's landscape. The o ...

in Cheshire, and Philipson herself died on 9 January 1951 in a nursing home in Brighton

Brighton ( ) is a seaside resort in the city status in the United Kingdom, city of Brighton and Hove, East Sussex, England, south of London.

Archaeological evidence of settlement in the area dates back to the Bronze Age Britain, Bronze Age, R ...

.

Selected filmography

*'' Sons of Martha'' (1907) *'' Masks and Faces'' (1917) * '' Tilly of Bloomsbury'' (1931)Notes

References

External links

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Philipson, Mabel 1886 births 1951 deaths 20th-century British women politicians 20th-century English actresses Actors from the London Borough of Southwark British actor-politicians British actors with disabilities British politicians with disabilities Conservative Party (UK) MPs for English constituencies Female members of the Parliament of the United Kingdom for English constituencies National Liberal Party (UK, 1922) politicians People from Peckham UK MPs 1922–1923 UK MPs 1923–1924 UK MPs 1924–1929