Lunatic asylum on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The lunatic asylum, insane asylum or mental asylum was an institution where people with mental illness were confined. It was an early precursor of the modern

The level of specialist institutional provision for the care and control of the insane remained extremely limited at the turn of the 18thcentury. Madness was seen principally as a domestic problem, with families and parish authorities in Europe and England central to regimens of care. Various forms of outdoor relief were extended by the parish authorities to families in these circumstances, including financial support, the provision of parish nurses and, where family care was not possible, lunatics might be 'boarded out' to other members of the local community or committed to private madhouses. Exceptionally, if those deemed mad were judged to be particularly disturbing or violent, parish authorities might meet the not inconsiderable costs of their confinement in charitable asylums such as Bethlem, in Houses of Correction or in workhouses.

In the late 17thcentury, this model began to change, and privately run asylums for the insane began to proliferate and expand in size. Already in 1632 it was recorded that

The level of specialist institutional provision for the care and control of the insane remained extremely limited at the turn of the 18thcentury. Madness was seen principally as a domestic problem, with families and parish authorities in Europe and England central to regimens of care. Various forms of outdoor relief were extended by the parish authorities to families in these circumstances, including financial support, the provision of parish nurses and, where family care was not possible, lunatics might be 'boarded out' to other members of the local community or committed to private madhouses. Exceptionally, if those deemed mad were judged to be particularly disturbing or violent, parish authorities might meet the not inconsiderable costs of their confinement in charitable asylums such as Bethlem, in Houses of Correction or in workhouses.

In the late 17thcentury, this model began to change, and privately run asylums for the insane began to proliferate and expand in size. Already in 1632 it was recorded that  A second public charitable institution was opened in 1713. Known as the Bethel in

A second public charitable institution was opened in 1713. Known as the Bethel in

William Tuke led the development of a radical new type of institution in

William Tuke led the development of a radical new type of institution in

Although Tuke, Pinel and others had tried to do away with physical restraint, it remained widespread in the 19thcentury. At the Lincoln Asylum in England,

Although Tuke, Pinel and others had tried to do away with physical restraint, it remained widespread in the 19thcentury. At the Lincoln Asylum in England,

The use of psychosurgery was narrowed to a very small number of people for specific indications. Egas Moniz performed the first leucotomy, or

The use of psychosurgery was narrowed to a very small number of people for specific indications. Egas Moniz performed the first leucotomy, or

In a monolithic state, psychiatry can be used to bypass standard legal procedures for establishing guilt or innocence and allow political incarceration without the ordinary odium attaching to such political trials. In

In a monolithic state, psychiatry can be used to bypass standard legal procedures for establishing guilt or innocence and allow political incarceration without the ordinary odium attaching to such political trials. In

The new antipsychotics had an immense impact on the lives of psychiatrists and patients. For instance, Henri Ey, a French psychiatrist at Bonneval, related that between 1921 and 1937 only 6% of patients with schizophrenia and chronic delirium were discharged from his institution. The comparable figure for the period from 1955 to 1967, after the introduction of chlorpromazine, was 67%. Between 1955 and 1968 the residential psychiatric population in the United States dropped by 30%. Newly developed

The new antipsychotics had an immense impact on the lives of psychiatrists and patients. For instance, Henri Ey, a French psychiatrist at Bonneval, related that between 1921 and 1937 only 6% of patients with schizophrenia and chronic delirium were discharged from his institution. The comparable figure for the period from 1955 to 1967, after the introduction of chlorpromazine, was 67%. Between 1955 and 1968 the residential psychiatric population in the United States dropped by 30%. Newly developed

psychiatric hospital

A psychiatric hospital, also known as a mental health hospital, a behavioral health hospital, or an asylum is a specialized medical facility that focuses on the treatment of severe Mental disorder, mental disorders. These institutions cater t ...

.

Modern psychiatric hospitals evolved from and eventually replaced the older lunatic asylum. The treatment of inmates in early lunatic asylums was sometimes brutal and focused on containment and restraint. The discovery of anti-psychotic drugs and mood-stabilizing drugs resulted in a shift in focus from containment in lunatic asylums to treatment in psychiatric hospitals. Later, there was further and more thorough critique in the form of the deinstitutionalization

Deinstitutionalisation (or deinstitutionalization) is the process of replacing long-stay psychiatric hospitals with less isolated community mental health services for those diagnosed with a mental disorder or developmental disability. In the 195 ...

movement which focuses on treatment at home or in less isolated institutions.

History

Medieval era

In the Islamic world, the ''Bimaristan

A bimaristan (; ), or simply maristan, known in Arabic also as ("house of healing"; in Turkish), is a hospital in the historic Islamic world. Its origins can be traced back to Sassanian Empire prior to the Muslim conquest of Persia.

The word ...

s'' were described by European travellers, who wrote about their wonder at the care and kindness shown to lunatics. In 872, Ahmad ibn Tulun

Ahmad ibn Tulun (; c. 20 September 835 – 10 May 884) was the founder of the Tulunid dynasty that ruled Egypt in the Middle Ages, Egypt and Bilad al-Sham, Syria between 868 and 905. Originally a Turkic peoples, Turkic slave-soldier, in 868 Ibn ...

built a hospital in Cairo

Cairo ( ; , ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Egypt and the Cairo Governorate, being home to more than 10 million people. It is also part of the List of urban agglomerations in Africa, largest urban agglomeration in Africa, L ...

that provided care to the insane, which included music therapy. Nonetheless, British historian of medicine Roy Porter

Roy Sydney Porter (31 December 1946 – 3 March 2002) was a British historian known for his work on the history of medicine. He retired in 2001 as the director of the Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine at University College London ...

cautioned against idealising the role of hospitals generally in medieval Islam, stating that "They were a drop in the ocean for the vast population that they had to serve, and their true function lay in highlighting ideals of compassion and bringing together the activities of the medical profession."

In Europe during the medieval era, a small subsection of the population of those considered mad were housed in a variety of institutional settings. Mentally ill people were often held captive in cages or kept up within the city walls, or they were compelled to amuse members of courtly society. Porter gives examples of such locales where some of the insane were cared for, such as in monasteries. A few towns had towers where madmen were kept (called '' Narrentürme'' in German, or "fools' towers"). The ancient Parisian hospital ''Hôtel-Dieu'' also had a small number of cells set aside for lunatics, whilst the town of Elbing boasted a madhouse, the '' Tollhaus,'' attached to the Teutonic Knights' hospital. Dave Sheppard's ''Development of Mental Health Law and Practice'' begins in 1285 with a case that linked "the instigation of the devil" with being "frantic and mad".

In Spain, other such institutions for the insane were established after the Christian Reconquista

The ''Reconquista'' (Spanish language, Spanish and Portuguese language, Portuguese for ) or the fall of al-Andalus was a series of military and cultural campaigns that European Christian Reconquista#Northern Christian realms, kingdoms waged ag ...

; facilities included hospitals in Valencia

Valencia ( , ), formally València (), is the capital of the Province of Valencia, province and Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Valencian Community, the same name in Spain. It is located on the banks of the Turia (r ...

(1407), Zaragoza

Zaragoza (), traditionally known in English as Saragossa ( ), is the capital city of the province of Zaragoza and of the autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Aragon, Spain. It lies by the Ebro river and its tributaries, the ...

(1425), Seville

Seville ( ; , ) is the capital and largest city of the Spain, Spanish autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the Guadalquivir, River Guadalquivir, ...

(1436), Barcelona

Barcelona ( ; ; ) is a city on the northeastern coast of Spain. It is the capital and largest city of the autonomous community of Catalonia, as well as the second-most populous municipality of Spain. With a population of 1.6 million within c ...

(1481) and Toledo (1483). In London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

, England, the Priory of Saint Mary of Bethlehem, which later became known more notoriously as Bedlam, was founded in 1247. At the start of the 15thcentury, it housed six insane men. The former lunatic asylum, Het Dolhuys, established in the 16thcentury in Haarlem

Haarlem (; predecessor of ''Harlem'' in English language, English) is a List of cities in the Netherlands by province, city and Municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality in the Netherlands. It is the capital of the Provinces of the Nether ...

, the Netherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

, has been adapted as a museum of psychiatry, with an overview of treatments from the origins of the building up to the 1990s.

Emergence of public lunatic asylums

The level of specialist institutional provision for the care and control of the insane remained extremely limited at the turn of the 18thcentury. Madness was seen principally as a domestic problem, with families and parish authorities in Europe and England central to regimens of care. Various forms of outdoor relief were extended by the parish authorities to families in these circumstances, including financial support, the provision of parish nurses and, where family care was not possible, lunatics might be 'boarded out' to other members of the local community or committed to private madhouses. Exceptionally, if those deemed mad were judged to be particularly disturbing or violent, parish authorities might meet the not inconsiderable costs of their confinement in charitable asylums such as Bethlem, in Houses of Correction or in workhouses.

In the late 17thcentury, this model began to change, and privately run asylums for the insane began to proliferate and expand in size. Already in 1632 it was recorded that

The level of specialist institutional provision for the care and control of the insane remained extremely limited at the turn of the 18thcentury. Madness was seen principally as a domestic problem, with families and parish authorities in Europe and England central to regimens of care. Various forms of outdoor relief were extended by the parish authorities to families in these circumstances, including financial support, the provision of parish nurses and, where family care was not possible, lunatics might be 'boarded out' to other members of the local community or committed to private madhouses. Exceptionally, if those deemed mad were judged to be particularly disturbing or violent, parish authorities might meet the not inconsiderable costs of their confinement in charitable asylums such as Bethlem, in Houses of Correction or in workhouses.

In the late 17thcentury, this model began to change, and privately run asylums for the insane began to proliferate and expand in size. Already in 1632 it was recorded that Bethlem Royal Hospital

Bethlem Royal Hospital, also known as St Mary Bethlehem, Bethlehem Hospital and Bedlam, is a psychiatric hospital in Bromley, London. Its famous history has inspired several horror books, films, and television series, most notably ''Bedlam (194 ...

, London had "below stairs a parlor, a kitchen, two larders, a long entry throughout the house, and 21 rooms wherein the poor distracted people lie, and above the stairs eight rooms more for servants and the poor to lie in". Inmates who were deemed dangerous or disturbing were chained, but Bethlem was an otherwise open building. Its inhabitants could roam around its confines and possibly throughout the general neighborhood in which the hospital was situated. In 1676, Bethlem expanded into newly built premises at Moorfields

Moorfields was an open space, partly in the City of London, lying adjacent to – and outside – its London Wall, northern wall, near the eponymous Moorgate. It was known for its marshy conditions, the result of the defensive wall acting a ...

with a capacity for 100 inmates.

A second public charitable institution was opened in 1713. Known as the Bethel in

A second public charitable institution was opened in 1713. Known as the Bethel in Norwich

Norwich () is a cathedral city and district of the county of Norfolk, England, of which it is the county town. It lies by the River Wensum, about north-east of London, north of Ipswich and east of Peterborough. The population of the Norwich ...

, it was a small facility which generally housed between twenty and thirty inmates. In 1728 at Guy's Hospital

Guy's Hospital is an NHS hospital founded by philanthropist Thomas Guy in 1721, located in the borough of Southwark in central London. It is part of Guy's and St Thomas' NHS Foundation Trust and one of the institutions that comprise the Kin ...

, London, wards were established for chronic lunatics. From the mid-eighteenth century the number of public charitably funded asylums expanded moderately with the opening of St Luke's Hospital in 1751 in Upper Moorfields, London; the establishment in 1765 of the Hospital for Lunatics at Newcastle upon Tyne

Newcastle upon Tyne, or simply Newcastle ( , Received Pronunciation, RP: ), is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England. It is England's northernmost metropolitan borough, located o ...

; the Manchester Lunatic Hospital, which opened in 1766; the York

York is a cathedral city in North Yorkshire, England, with Roman Britain, Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers River Ouse, Yorkshire, Ouse and River Foss, Foss. It has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a Yor ...

Asylum in 1777 (not to be confused with the York Retreat

The Retreat, commonly known as the York Retreat, is a place in England for the treatment of people with mental health needs. Located in Lamel Hill in York, it operates as a not for profit charitable organisation.

Opened in 1796, it is famous ...

); the Leicester

Leicester ( ) is a city status in the United Kingdom, city, Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority area, and the county town of Leicestershire in the East Midlands of England. It is the largest city in the East Midlands with a popula ...

Lunatic Asylum (1794), and the Liverpool

Liverpool is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. It is situated on the eastern side of the River Mersey, Mersey Estuary, near the Irish Sea, north-west of London. With a population ...

Lunatic Asylum (1797).

A similar expansion took place in the British America

British America collectively refers to various British colonization of the Americas, colonies of Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and its predecessors states in the Americas prior to the conclusion of the American Revolutionary War in 1 ...

n colonies. The Pennsylvania Hospital

Pennsylvania Hospital is a Private hospital, private, non-profit, 515-bed teaching hospital located at 800 Spruce Street (Philadelphia), Spruce Street in Center City, Philadelphia, Center City Philadelphia, The hospital was founded on May 11, 17 ...

was founded in Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

in 1751 as a result of work begun in 1709 by the Religious Society of Friends

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations. Members refer to each other as Friends after in the Bible, and originally, others referred to them as Quakers ...

. A portion of this hospital was set apart for the mentally ill, and the first patients were admitted in 1752. Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States between the East Coast of the United States ...

is recognized as the first state to establish an institution for the mentally ill. Eastern State Hospital, located in Williamsburg, Virginia

Williamsburg is an Independent city (United States), independent city in Virginia, United States. It had a population of 15,425 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. Located on the Virginia Peninsula, Williamsburg is in the northern par ...

, was incorporated in 1768 under the name of the "Public Hospital for Persons of Insane and Disordered Minds" and its first patients were admitted in 1773.

Trade in lunacy

There was no centralised state response to “madness” in society in centuryBritain

Britain most often refers to:

* Great Britain, a large island comprising the countries of England, Scotland and Wales

* The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, a sovereign state in Europe comprising Great Britain and the north-eas ...

until the 19thcentury, however private madhouses proliferated there in the 18thcentury on a scale unseen elsewhere. References to such institutions are limited for the 17thcentury but it is evident that by the start of the 18thcentury, the so-called 'trade in lunacy' was well established. Daniel Defoe

Daniel Defoe (; born Daniel Foe; 1660 – 24 April 1731) was an English writer, merchant and spy. He is most famous for his novel ''Robinson Crusoe'', published in 1719, which is claimed to be second only to the Bible in its number of translati ...

, an ardent critic of private madhouses, estimated in 1724 that there were fifteen then operating in the London area. Defoe may have exaggerated but exact figures for private metropolitan madhouses are available only from 1774, when licensing legislation was introduced: sixteen institutions were recorded. At least two of these, Hoxton House and Wood's Close, Clerkenwell

Clerkenwell ( ) is an area of central London, England.

Clerkenwell was an Civil Parish#Ancient parishes, ancient parish from the medieval period onwards, and now forms the south-western part of the London Borough of Islington. The St James's C ...

, had been in operation since the 17thcentury. By 1807, the number had increased to seventeen. This limited growth in the number of London madhouses is believed likely to reflect the fact that vested interests, especially the College of Physicians

A college (Latin: ''collegium'') may be a tertiary educational institution (sometimes awarding degrees), part of a collegiate university, an institution offering vocational education, a further education institution, or a secondary school ...

, exercised considerable control in preventing new entrants to the market. Thus, rather than there being a proliferation of private madhouses in London, existing institutions tended to expand considerably in size. The establishments which increased most during the 18thcentury, such as Hoxton House, did so by accepting pauper patients rather than private, middle class, fee-paying patients. Significantly, pauper patients, unlike their private counterparts, were not subject to inspection under the 1774 legislation.

Fragmentary evidence indicates that some provincial madhouses existed in Britain from at least the 17thcentury and possibly earlier. A madhouse at Kingsdown, Box, Wiltshire was opened during the 17thcentury. Further locales of early businesses include one at Guildford

Guildford () is a town in west Surrey, England, around south-west of central London. As of the 2011 census, the town has a population of about 77,000 and is the seat of the wider Borough of Guildford, which had around inhabitants in . The nam ...

in Surrey which was accepting patients by 1700, one at Fonthill Gifford

Fonthill Gifford is a village and civil parish in Wiltshire, England, to the north of the Nadder valley, west of Salisbury.

History

The name of the village and parish derives from the Giffard family, landowners, beginning with Berenger Gif ...

in Wiltshire from 1718, another at Hook Norton in Oxfordshire from about 1725, one at St Albans

St Albans () is a cathedral city in Hertfordshire, England, east of Hemel Hempstead and west of Hatfield, Hertfordshire, Hatfield, north-west of London, south-west of Welwyn Garden City and south-east of Luton. St Albans was the first major ...

dating from around 1740, and a madhouse at Fishponds

Fishponds is a suburb in the north-east of the English city of Bristol, about from Bristol city centre, the city centre. It is mainly residential, and housing is typically terraced Victorian. It has a small student population from the presence ...

in Bristol from 1766. It is likely that many of these provincial madhouses, as was the case with the exclusive Ticehurst House, may have evolved from householders who were boarding lunatics on behalf of parochial authorities and later formalised this practice into a business venture. The vast majority were small in scale with only seven asylums outside London with in excess of thirty patients by 1800 and somewhere between ten and twenty institutions had fewer patients than this.

Humanitarian reform

During theAge of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment (also the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment) was a Europe, European Intellect, intellectual and Philosophy, philosophical movement active from the late 17th to early 19th century. Chiefly valuing knowledge gained th ...

, attitudes began to change, in particular among the educated classes in Western Europe. “Mental illness” came to be viewed as a disorder that required some form of compassionate but clinical, “rational” treatment that would aid in the rehabilitation of the patient into a rational being. When the ruling monarch of the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

, George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland, Ireland from 25 October 1760 until his death in 1820. The Acts of Union 1800 unified Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and ...

, who had a mental disorder, experienced a remission in 1789, mental illness came to be seen as something which could be treated and cured. The introduction of moral treatment was initiated independently by the French doctor Philippe Pinel and the English Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations. Members refer to each other as Friends after in the Bible, and originally, others referred to them as Quakers ...

William Tuke.Elkes, A. & Thorpe, J.G. (1967). ''A Summary of Psychiatry''. London: Faber & Faber, p. 13.

In 1792, Pinel became the chief physician at the Bicêtre Hospital in Le Kremlin-Bicêtre

Le Kremlin-Bicêtre () is a commune in the southern suburbs of Paris, France. It is from the center of Paris. It is one of the most densely populated municipalities in Europe.

Le Kremlin-Bicêtre is most famous as the location of the Bicêtre ...

, near Paris. Before his arrival, inmates were chained in cramped cell-like rooms where there was poor ventilation, led by a man named Jackson 'Brutis' Taylor. Taylor was then killed by the inmates leading to Pinel's leadership. In 1797, Jean-Baptiste Pussin, the "governor" of mental patients at Bicêtre, first freed patients of their chains and banned physical punishment, although straitjackets could be used instead. Patients were allowed to move freely about the hospital grounds, and eventually dark dungeons were replaced with sunny, well-ventilated rooms. Pinel argued that mental illness was the result of excessive exposure to social and psychological stresses, to heredity

Heredity, also called inheritance or biological inheritance, is the passing on of traits from parents to their offspring; either through asexual reproduction or sexual reproduction, the offspring cells or organisms acquire the genetic infor ...

and physiological damage.

Pussin and Pinel's approach was seen as remarkably successful, and they later brought similar reforms to a mental hospital in Paris for female patients, La Salpetrière. Pinel's student and successor, Jean Esquirol

Jean may refer to:

People

* Jean (female given name)

* Jean (male given name)

* Jean (surname)

Fictional characters

* Jean Grey, a Marvel Comics character

* Jean Valjean, fictional character in novel ''Les Misérables'' and its adaptations

* Jea ...

, went on to help establish 10 new mental hospitals that operated on the same principles. There was an emphasis on the selection and supervision of attendants in order to establish a suitable setting to facilitate psychological work, and particularly on the employment of ex-patients as they were thought most likely to refrain from inhumane treatment while being able to stand up to patients' pleas, menaces, or complaints.

William Tuke led the development of a radical new type of institution in

William Tuke led the development of a radical new type of institution in Northern England

Northern England, or the North of England, refers to the northern part of England and mainly corresponds to the Historic counties of England, historic counties of Cheshire, Cumberland, County Durham, Durham, Lancashire, Northumberland, Westmo ...

, following the death of a fellow Quaker in a local asylum in 1790. In 1796, with the help of fellow Quakers and others, he founded the York Retreat

The Retreat, commonly known as the York Retreat, is a place in England for the treatment of people with mental health needs. Located in Lamel Hill in York, it operates as a not for profit charitable organisation.

Opened in 1796, it is famous ...

, where eventually about 30 patients lived as part of a small community in a quiet country house and engaged in a combination of rest, talk, and manual work. Rejecting medical theories and techniques, the efforts of the York Retreat centred around minimising restraints and cultivating rationality and moral strength.

The entire Tuke family became known as founders of moral treatment. They created a family-style ethos, and patients performed chores to give them a sense of contribution. There was a daily routine of both work and leisure time. If patients behaved well, they were rewarded; if they behaved poorly, there was some minimal use of restraints or instilling of fear. The patients were told that treatment depended on their conduct. In this sense, the patient's moral autonomy was recognised. William Tuke's grandson, Samuel Tuke, published an influential work in the early 19thcentury on the methods of the retreat; Pinel's ''Treatise on Insanity'' had by then been published, and Samuel Tuke translated his term as "moral treatment". Tuke's Retreat became a model throughout the world for humane and moral treatment of patients with mental disorders.

The York Retreat inspired similar institutions in the United States, most notably the Brattleboro Retreat and the Hartford Retreat (now the Institute of Living

''The'' is a grammatical article in English, denoting nouns that are already or about to be mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in English. ''The ...

). Benjamin Rush

Benjamin Rush (April 19, 1813) was an American revolutionary, a Founding Father of the United States and signatory to the U.S. Declaration of Independence, and a civic leader in Philadelphia, where he was a physician, politician, social refor ...

of Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

also promoted humane treatment of the insane outside dungeons and without iron restraints, as well as sought their reintegration into society. In 1792, Rush successfully campaigned for a separate ward for the insane at the Pennsylvania Hospital. His talk-based approach could be considered as a rudimentary form of modern occupational therapy, although most of his physical approaches have long been discredited, such as bleeding and purging, hot and cold baths, mercury pills, a "tranquilizing chair" and gyroscope.

A similar reform was carried out in Italy by Vincenzo Chiarugi, who discontinued the use of chains on the inmates in the early 19thcentury. In the town of Interlaken

Interlaken (; lit.: ''between lakes'') is a Swiss town and municipality in the Interlaken-Oberhasli administrative district in the canton of Bern. It is an important and well-known tourist destination in the Bernese Oberland region of the Swiss ...

, Johann Jakob Guggenbühl

Johann Jakob Guggenbühl (August 13, 1816, Meilen – February 2, 1863 Montreux

Montreux (, ; ; ) is a Municipalities of Switzerland, Swiss municipality and List of towns in Switzerland, town on the shoreline of Lake Geneva at the foot of the ...

started a retreat for mentally disabled children in 1841.

Institutionalisation

The modern era of institutionalized provision for the care of the mentally ill, began in the early 19thcentury with a large state-led effort. Public mental asylums were established in Britain after the passing of the 1808 County Asylums Act. This empoweredmagistrate

The term magistrate is used in a variety of systems of governments and laws to refer to a civilian officer who administers the law. In ancient Rome, a '' magistratus'' was one of the highest ranking government officers, and possessed both judi ...

s to build rate-supported asylums in every county

A county () is a geographic region of a country used for administrative or other purposesL. Brookes (ed.) '' Chambers Dictionary''. Edinburgh: Chambers Harrap Publishers Ltd, 2005. in some nations. The term is derived from the Old French denoti ...

to house the many 'pauper lunatics'. Nine counties first applied, and the first public asylum opened in 1811 in Nottinghamshire

Nottinghamshire (; abbreviated ''Notts.'') is a ceremonial county in the East Midlands of England. The county is bordered by South Yorkshire to the north-west, Lincolnshire to the east, Leicestershire to the south, and Derbyshire to the west. Th ...

. Parliamentary Committee

A committee or commission is a body of one or more persons subordinate to a deliberative assembly or other form of organization. A committee may not itself be considered to be a form of assembly or a decision-making body. Usually, an assembly o ...

s were established to investigate abuses at private madhouses like Bethlem Hospital

Bethlem Royal Hospital, also known as St Mary Bethlehem, Bethlehem Hospital and Bedlam, is a psychiatric hospital in Bromley, London. Its famous history has inspired several horror books, films, and television series, most notably '' Bedlam'', ...

– its officers were eventually dismissed and national attention was focused on the routine use of bars, chains and handcuffs and the filthy conditions the inmates lived in. However, it was not until 1828 that the newly appointed Commissioners in Lunacy were empowered to license and supervise private asylums.

The Lunacy Act 1845 was an important landmark in the treatment of the mentally ill, as it explicitly changed the status of mentally ill

A mental disorder, also referred to as a mental illness, a mental health condition, or a psychiatric disability, is a behavioral or mental pattern that causes significant distress or impairment of personal functioning. A mental disorder is ...

people to patients

A patient is any recipient of health care services that are performed by healthcare professionals. The patient is most often ill or injured and in need of treatment by a physician, nurse, optometrist, dentist, veterinarian, or other healt ...

who required treatment. The Act created the Lunacy Commission, headed by Lord Shaftesbury, to focus on lunacy legislation reform. The commission was made up of eleven Metropolitan Commissioners who were required to carry out the provisions of the Act: the compulsory construction of asylums in every county, with regular inspections on behalf of the Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, more commonly known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom and the head of the Home Office. The position is a Great Office of State, maki ...

. All asylums were required to have written regulations and to have a resident qualified physician

A physician, medical practitioner (British English), medical doctor, or simply doctor is a health professional who practices medicine, which is concerned with promoting, maintaining or restoring health through the Medical education, study, Med ...

. A national body for asylum superintendents – the ''Medico-Psychological Association'' – was established in 1866 under the Presidency of William A. F. Browne, although the body appeared in an earlier form in 1841.

In 1838, France enacted a law to regulate both the admissions into asylums and asylum services across the country. Édouard Séguin

Édouard Séguin (January 20, 1812 – October 28, 1880) was a French physician and educationist born in Clamecy, Nièvre. He is remembered for his work with children having cognitive impairments in France and the United States.

Background and ...

developed a systematic approach for training individuals with mental deficiencies, and, in 1839, he opened the first school for the "severely retarded". His method of treatment was based on the assumption that the "mentally deficient" did not suffer from disease.

In the United States, the erection of state asylums began with the first law for the creation of one in New York, passed in 1842. The Utica State Hospital

The Utica Psychiatric Center, also known as Utica State Hospital, opened in Utica, New York, Utica on January 16, 1843.

It was New York (state), New York's first state-run facility designed to care for the mentally ill, and one of the ...

was opened approximately in 1850. The creation of this hospital, as of many others, was largely the work of Dorothea Lynde Dix, whose philanthropic efforts extended over many states, and in Europe as far as Constantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

. Many state hospitals in the United States were built in the 1850s and 1860s on the Kirkbride Plan

The Kirkbride Plan was a system of mental asylum design advocated by American psychiatrist Thomas Story Kirkbride (1809–1883) in the mid-19th century. The asylums built in the Kirkbride design, often referred to as Kirkbride Buildings (or simp ...

, an architectural style meant to have curative effect.

Looking into the late 19thand early 20thcentury history of the Homewood Retreat of Guelph, Ontario, and the context of commitments to asylums in North America and Great Britain, Cheryl Krasnick Warsh states that "the kin of asylum patients were, in fact, the major impetus behind commitment, but their motivations were based not so much upon greed as upon the internal dynamics of the family, and upon the economic structure of western society in the 19th and early 20thcenturies."

Women in psychiatric institutions

Based on her study of cases from the Homewood Retreat, Cheryl Krasnick Warsh concludes that "the realities of the household in late Victorian and Edwardian middle class society rendered certain elements—socially redundant women in particular—more susceptible to institutionalization than others." In the 18th to the early 20thcentury, women were sometimes institutionalised due to their opinions, their unruliness and their inability to be controlled properly by a primarily male-dominated culture. There were financial incentives too; before the passage of theMarried Women's Property Act 1882

The Married Women's Property Act 1882 (45 & 46 Vict. c. 75) was an Act of Parliament (United Kingdom), act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom that significantly altered English law regarding the property rights of married women, which besid ...

, all of a wife's assets passed automatically to her husband.

The men who were in charge of these women, either a husband, father or brother, could send these women to mental institutions, stating that they believed that these women were mentally ill because of their strong opinions. "Between the years of 1850–1900, women were placed in mental institutions for behaving in ways the male society did not agree with." These men had the last say when it came to the mental health of these women, so if they believed that these women were mentally ill, or if they simply wanted to silence the voices and opinions of these women, they could easily send them to mental institutions. This was an easy way to render them vulnerable and submissive.

An early fictional example is Mary Wollstonecraft

Mary Wollstonecraft ( , ; 27 April 175910 September 1797) was an English writer and philosopher best known for her advocacy of women's rights. Until the late 20th century, Wollstonecraft's life, which encompassed several unconventional ...

's posthumously published novel '' Maria: or, The Wrongs of Woman'' (1798), in which the title character is confined to an insane asylum when she becomes inconvenient to her husband. Real women's stories reached the public through court cases: Louisa Nottidge was abducted by male relatives to prevent her committing her inheritance and her life to live in a revivalist clergyman's intentional community

An intentional community is a voluntary residential community designed to foster a high degree of group cohesiveness, social cohesion and teamwork. Such communities typically promote shared values or beliefs, or pursue a common vision, wh ...

. Wilkie Collins

William Wilkie Collins (8 January 1824 – 23 September 1889) was an English novelist and playwright known especially for ''The Woman in White (novel), The Woman in White'' (1860), a mystery novel and early sensation novel, and for ''The Moonsto ...

based his 1859 novel '' The Woman in White'' on this case, dedicating it to Bryan Procter, the Commissioner for Lunacy. A generation later, Rosina Bulwer Lytton, daughter of the women's rights advocate Anna Wheeler, was locked up by her husband Edward Bulwer-Lytton

Edward George Earle Lytton Bulwer-Lytton, 1st Baron Lytton (; 25 May 1803 – 18 January 1873) was an English writer and politician. He served as a Whig member of Parliament from 1831 to 1841 and a Conservative from 1851 to 1866. He was Secr ...

and subsequently wrote of this in '' A Blighted Life'' (1880).

In 1887, journalist Nellie Bly

Elizabeth Cochrane Seaman (born Elizabeth Jane Cochran; May 5, 1864 – January 27, 1922), better known by her pen name Nellie Bly, was an American journalist who was widely known for her record-breaking circumnavigation, trip around the world ...

had herself committed to the Blackwell's Island Insane Asylum in New York City, in order to investigate conditions there. Her account was published in the ''New York World

The ''New York World'' was a newspaper published in New York City from 1860 to 1931. The paper played a major role in the history of American newspapers as a leading national voice of the Democratic Party. From 1883 to 1911 under publisher Jo ...

'' newspaper, and in book form as '' Ten Days in a Mad-House''.

In 1902, Margarethe von Ende, wife of the German arms manufacturer Friedrich Alfred Krupp, was consigned to an insane asylum by Kaiser Wilhelm II

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor Albert; 27 January 18594 June 1941) was the last German Emperor and King of Prussia from 1888 until his abdication in 1918, which marked the end of the German Empire as well as the Hohenzollern dynasty ...

, a family friend, when she asked him to respond to reports of her husband's gay orgies on Capri.

New practices

Incontinental Europe

Continental Europe or mainland Europe is the contiguous mainland of Europe, excluding its surrounding islands. It can also be referred to ambiguously as the European continent, – which can conversely mean the whole of Europe – and, by som ...

, universities often played a part in the administration of the asylums. In Germany, many practising psychiatrists were educated in universities associated with particular asylums. However, because Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

remained a loosely bound conglomerate of individual states, it lacked a national regulatory framework for asylums.

Although Tuke, Pinel and others had tried to do away with physical restraint, it remained widespread in the 19thcentury. At the Lincoln Asylum in England,

Although Tuke, Pinel and others had tried to do away with physical restraint, it remained widespread in the 19thcentury. At the Lincoln Asylum in England, Robert Gardiner Hill

Robert Gardiner Hill MD (26 February 1811 – 30 May 1878) was a British surgeon specialising in the treatment of lunatic, lunacy. He is normally credited with being the first superintendent of a small Insane asylum, asylum (approximately 100 p ...

, with the support of Edward Parker Charlesworth, pioneered a mode of treatment that suited "all types" of patients, so that mechanical restraints and coercion could be dispensed with—a situation he finally achieved in 1838. In 1839 Sergeant John Adams and Dr. John Conolly were impressed by the work of Hill, and introduced the method into their Hanwell Asylum, by then the largest in the country. Hill's system was adapted, since Conolly was unable to supervise each attendant as closely as Hill had done. By September 1839, mechanical restraint was no longer required for any patient.Edited by: Bynum, W. F; Porter, Roy; Shepherd, Michael (1988) ''The Anatomy of Madness: Essays in the history of psychiatry''. Vol.3. The Asylum and its psychiatry. Routledge. London EC4

William A. F. Browne (1805–1885) introduced activities for patients including writing, art, group activity and drama, pioneered early forms of occupational therapy

Occupational therapy (OT), also known as ergotherapy, is a healthcare profession. Ergotherapy is derived from the Greek wiktionary:ergon, ergon which is allied to work, to act and to be active. Occupational therapy is based on the assumption t ...

and art therapy

Art therapy is a distinct discipline that incorporates creative methods of expression through visual art media. Art therapy, as a creative arts therapy profession, originated in the fields of art and psychotherapy and may vary in definition. Art ...

, and initiated one of the earliest collections of artistic work by patients, at Montrose Asylum.

=Rapid expansion

= By the end of the 19thcentury, national systems of regulated asylums for the mentally ill had been established in most industrialized countries. At the turn of the century,Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* Great Britain, a large island comprising the countries of England, Scotland and Wales

* The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, a sovereign state in Europe comprising Great Britain and the north-eas ...

and France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

combined had only a few hundred people in asylums, but by the end of the century this number had risen to the hundreds of thousands. The United States housed 150,000 patients in mental hospitals by 1904. Germany housed more than 400 public and private sector asylums. These asylums were critical to the evolution of psychiatry as they provided places of practice throughout the world.

However, the hope that mental illness could be ameliorated through treatment during the mid-19thcentury was disappointed. Instead, psychiatrists were pressured by an ever-increasing patient population. The average number of patients in asylums in the United States jumped 927%. Numbers were similar in Britain and Germany. Overcrowding was rampant in France, where asylums would commonly take in double their maximum capacity. Increases in asylum populations may have been a result of the transfer of care from families and poorhouse

A poorhouse or workhouse is a government-run (usually by a county or municipality) facility to support and provide housing for the dependent or needy.

Workhouses

In England, Wales and Ireland (but not in Scotland), "workhouse" has been the more ...

s, but the specific reasons as to why the increase occurred are still debated today. No matter the cause, the pressure on asylums from the increase was taking its toll on the asylums and psychiatry as a specialty. Asylums were once again turning into custodial institutionsRothman, D.J. (1990). ''The Discovery of the Asylum: Social Order and Disorder in the New Republic''. Boston: Little Brown, p. 239. and the reputation of psychiatry in the medical world had hit an extreme low.

In the 1800s, middle class facilities became more common, replacing private care for wealthier persons. However, facilities in this period were largely oversubscribed. Individuals were referred to facilities either by the community or by the criminal justice system. Dangerous or violent cases were usually given precedence for admission. A survey taken in 1891 in Cape Town

Cape Town is the legislature, legislative capital city, capital of South Africa. It is the country's oldest city and the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. Cape Town is the country's List of municipalities in South Africa, second-largest ...

, South Africa shows the distribution between different facilities. Out of 2046 persons surveyed, 1,281 were in private dwellings, 120 in jails and 645 in asylums, with men representing nearly two-thirds of the number surveyed.

Defining someone as insane was a necessary prerequisite for being admitted to a facility. A doctor was only called after someone was labelled insane on social terms and had become socially or economically problematic. Until the 1890s, little distinction existed between the lunatic and criminal lunatic. The term was often used to police vagrancy

Vagrancy is the condition of wandering homelessness without regular employment or income. Vagrants usually live in poverty and support themselves by travelling while engaging in begging, waste picker, scavenging, or petty theft. In Western ...

as well as paupers and the insane. In the 1850s, lurid rumours that medical doctors were declaring normal people "insane" in Britain, were spread by the press causing widespread public anxiety. The fear was that people who were a source of embarrassment to their families were conveniently disposed of into asylums with the willing connivance of the psychiatric profession. This sensationalism

In journalism and mass media, sensationalism is a type of editorial tactic. Events and topics in news stories are selected and worded to excite the greatest number of readers and viewers. This style of news reporting encourages biased or emoti ...

appeared in widely read novel

A novel is an extended work of narrative fiction usually written in prose and published as a book. The word derives from the for 'new', 'news', or 'short story (of something new)', itself from the , a singular noun use of the neuter plural of ...

s of the time, including '' The Woman in White''.

20th century

Physical therapies

A series of radical physical therapies were developed in central and continental Europe in the late 1910s, the 1920s and most particularly, the 1930s. Among these, we may note theAustria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

n psychiatrist Julius Wagner-Jauregg's malarial therapy for general paresis of the insane (or neurosyphilis

Neurosyphilis is the infection of the central nervous system by '' Treponema pallidum'', the bacterium that causes the sexually transmitted infection syphilis. In the era of modern antibiotics, the majority of neurosyphilis cases have been report ...

) first used in 1917, and for which he won a Nobel Prize in 1927. This treatment heralded the beginning of a radical and experimental era in psychiatric medicine that increasingly broke with an asylum-based culture of therapeutic nihilism in the treatment of chronic psychiatric disorders

A mental disorder, also referred to as a mental illness, a mental health condition, or a psychiatric disability, is a behavioral or mental pattern that causes significant distress or impairment of personal functioning. A mental disorder is ...

, most particularly dementia praecox (increasingly known as schizophrenia

Schizophrenia () is a mental disorder characterized variously by hallucinations (typically, Auditory hallucination#Schizophrenia, hearing voices), delusions, thought disorder, disorganized thinking and behavior, and Reduced affect display, f ...

from the 1910s, although the two terms were used more or less interchangeably until at least the end of the 1930s), which were typically regarded as hereditary degenerative disorders and therefore unamenable to any therapeutic intervention. Malarial therapy was followed in 1920 by barbiturate

Barbiturates are a class of depressant, depressant drugs that are chemically derived from barbituric acid. They are effective when used medication, medically as anxiolytics, hypnotics, and anticonvulsants, but have physical and psychological a ...

-induced deep sleep therapy to treat dementia praecox, which was popularised by the Swiss

Swiss most commonly refers to:

* the adjectival form of Switzerland

* Swiss people

Swiss may also refer to: Places

* Swiss, Missouri

* Swiss, North Carolina

* Swiss, West Virginia

* Swiss, Wisconsin

Other uses

* Swiss Café, an old café located ...

psychiatrist Jakob Klaesi. In 1933 the Vienna

Vienna ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital, List of largest cities in Austria, most populous city, and one of Federal states of Austria, nine federal states of Austria. It is Austria's primate city, with just over two million inhabitants. ...

-based psychiatrist Manfred Sakel

Manfred Joshua Sakel (June 6, 1900 – December 2, 1957) was an Austrian-American neurophysiologist and psychiatrist, credited with developing insulin shock therapy in 1927.

Biography

Sakel was born to a Jewish family on June 6, 1900, in Nadvir ...

introduced insulin shock therapy

Insulin shock therapy or insulin coma therapy was a form of psychiatric treatment in which patients were repeatedly injected with large doses of insulin in order to produce daily comas over several weeks.Neustatter WL (1948) ''Modern psychiatry ...

, and in August 1934 Ladislas J. Meduna, a Hungarian neuropathologist and psychiatrist working in Budapest

Budapest is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns of Hungary, most populous city of Hungary. It is the List of cities in the European Union by population within city limits, tenth-largest city in the European Union by popul ...

, introduced cardiazol shock therapy (cardiazol is the tradename of the chemical compound pentylenetetrazol, known by the tradename metrazol

Pentylenetetrazol (PTZ), also known as pentylenetetrazole, pentetrazol (International Nonproprietary Name, INN), and pentamethylenetetrazol, is a drug formerly used as a circulatory and respiratory stimulant. High doses cause convulsions, as dis ...

in the United States), which was the first convulsive or seizure therapy for a psychiatric disorder. Again, both of these therapies were initially targeted at curing dementia praecox. Cardiazol shock therapy, founded on the theoretical notion that there existed a biological antagonism between schizophrenia

Schizophrenia () is a mental disorder characterized variously by hallucinations (typically, Auditory hallucination#Schizophrenia, hearing voices), delusions, thought disorder, disorganized thinking and behavior, and Reduced affect display, f ...

and epilepsy

Epilepsy is a group of Non-communicable disease, non-communicable Neurological disorder, neurological disorders characterized by a tendency for recurrent, unprovoked Seizure, seizures. A seizure is a sudden burst of abnormal electrical activit ...

and that therefore inducing epileptiform fits in schizophrenic patients might effect a cure, was superseded by electroconvulsive therapy

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is a psychiatry, psychiatric treatment that causes a generalized seizure by passing electrical current through the brain. ECT is often used as an intervention for mental disorders when other treatments are inadequ ...

(ECT), invented by the Italian neurologist Ugo Cerletti

Ugo Cerletti (26 September 1877 – 25 July 1963) was an Italian neurology, neurologist who discovered the method of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) used in psychiatry. Electroconvulsive therapy is a therapy in which electric current is used to pro ...

in 1938.

The use of psychosurgery was narrowed to a very small number of people for specific indications. Egas Moniz performed the first leucotomy, or

The use of psychosurgery was narrowed to a very small number of people for specific indications. Egas Moniz performed the first leucotomy, or lobotomy

A lobotomy () or leucotomy is a discredited form of Neurosurgery, neurosurgical treatment for mental disorder, psychiatric disorder or neurological disorder (e.g. epilepsy, Depression in childhood and adolescence, depression) that involves sev ...

in Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, is a country on the Iberian Peninsula in Southwestern Europe. Featuring Cabo da Roca, the westernmost point in continental Europe, Portugal borders Spain to its north and east, with which it share ...

in 1935, which targets the brain's frontal lobes. This was shortly thereafter adapted by Walter Freeman and James W. Watts in what is known as Freeman–Watts procedure or the standard prefrontal lobotomy. From 1946, Freeman developed the transorbital lobotomy, using a device akin to an ice-pick. This was an "office" procedure which did not have to be performed in a surgical theatre and took as little as fifteen minutes to complete. Freeman is credited with the popularisation of the technique in the United States. In 1949, 5,074 lobotomies were carried out in the United States and by 1951, 18,608 people had undergone the controversial procedure in that country. One of the most famous people to have a lobotomy was the sister of John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), also known as JFK, was the 35th president of the United States, serving from 1961 until his assassination in 1963. He was the first Roman Catholic and youngest person elected p ...

, Rosemary Kennedy, who was rendered profoundly intellectually disabled as a result of the surgery.

In modern times, insulin shock therapy and lobotomies are viewed as being almost as barbaric as the Bedlam "treatments", although the insulin shock therapy was still seen as the only option which produced any noticeable effect on patients. ECT is still used in the West in the 21stcentury, but it is seen as a last resort for treatment of mood disorders and is administered much more safely than in the past. Elsewhere, particularly in India, use of ECT is reportedly increasing, as a cost-effective alternative to drug treatment. The effect of a shock on an overly excitable patient often allowed these patients to be discharged to their homes, which was seen by administrators (and often guardians) as a preferable solution to institutionalisation. Lobotomies were performed in the thousands from the 1930s to the 1950s, and were ultimately replaced with modern psychotropic drugs.

Eugenics movement

Theeugenics

Eugenics is a set of largely discredited beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter the frequency of various human phenotypes by inhibiting the fer ...

movement of the early 20thcentury led to a number of countries enacting laws for the compulsory sterilization of the "feeble minded", which resulted in the forced sterilization of numerous psychiatric inmates. As late as the 1950s, laws in Japan allowed the forcible sterilization of patients with psychiatric illnesses.

Under Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

, the Aktion T4

(German, ) was a campaign of Homicide#By state actors, mass murder by involuntary euthanasia which targeted Disability, people with disabilities and the mentally ill in Nazi Germany. The term was first used in post-WWII, war trials against d ...

euthanasia

Euthanasia (from : + ) is the practice of intentionally ending life to eliminate pain and suffering.

Different countries have different Legality of euthanasia, euthanasia laws. The British House of Lords Select committee (United Kingdom), se ...

program resulted in the killings of thousands of the mentally ill housed in state institutions. In 1939, the Nazis secretly began to exterminate the mentally ill in a euthanasia campaign. Around 6,000 disabled babies, children and teenagers were murdered by starvation or lethal injection.

Psychiatric internment as a political device

Psychiatrists around the world have been involved in the suppression of individual rights by states wherein the definitions of mental disease had been expanded to include political disobedience. Nowadays, in many countries, political prisoners are sometimes confined to mental institutions and abused therein. Psychiatry possesses a built-in capacity for abuse which is greater than in other areas of medicine. The diagnosis of mental disease can serve as proxy for the designation of social dissidents, allowing the state to hold persons against their will and to insist upon therapies that work in favour of ideologicalconformity

Conformity or conformism is the act of matching attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors to social group, group norms, politics or being like-minded. Social norm, Norms are implicit, specific rules, guidance shared by a group of individuals, that guide t ...

and in the broader interests of society.

Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

in the 1940s, the 'duty to care' was violated on an enormous scale: A reported 300,000 individuals were sterilised and 100,000 killed in Germany alone, as were many thousands further afield, mainly in Eastern Europe.

From the 1960s up to 1986, political abuse of psychiatry

Political abuse of psychiatry, also known as punitive psychiatry, refers to the misuse of psychiatric diagnosis, detention, and treatment to suppress individual or group human rights in society. This abuse involves the deliberate psychiatric dia ...

was reported to be systematic in the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

, and to surface on occasion in other Eastern European countries such as Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

, Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

, Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia ( ; Czech language, Czech and , ''Česko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland beca ...

and Yugoslavia

, common_name = Yugoslavia

, life_span = 1918–19921941–1945: World War II in Yugoslavia#Axis invasion and dismemberment of Yugoslavia, Axis occupation

, p1 = Kingdom of SerbiaSerbia

, flag_p ...

. A "mental health genocide" reminiscent of the Nazi aberrations has been located in the history of South African oppression during the apartheid

Apartheid ( , especially South African English: , ; , ) was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. It was characterised by an ...

era. A continued misappropriation of the discipline was subsequently attributed to the People's Republic of China.

Drugs

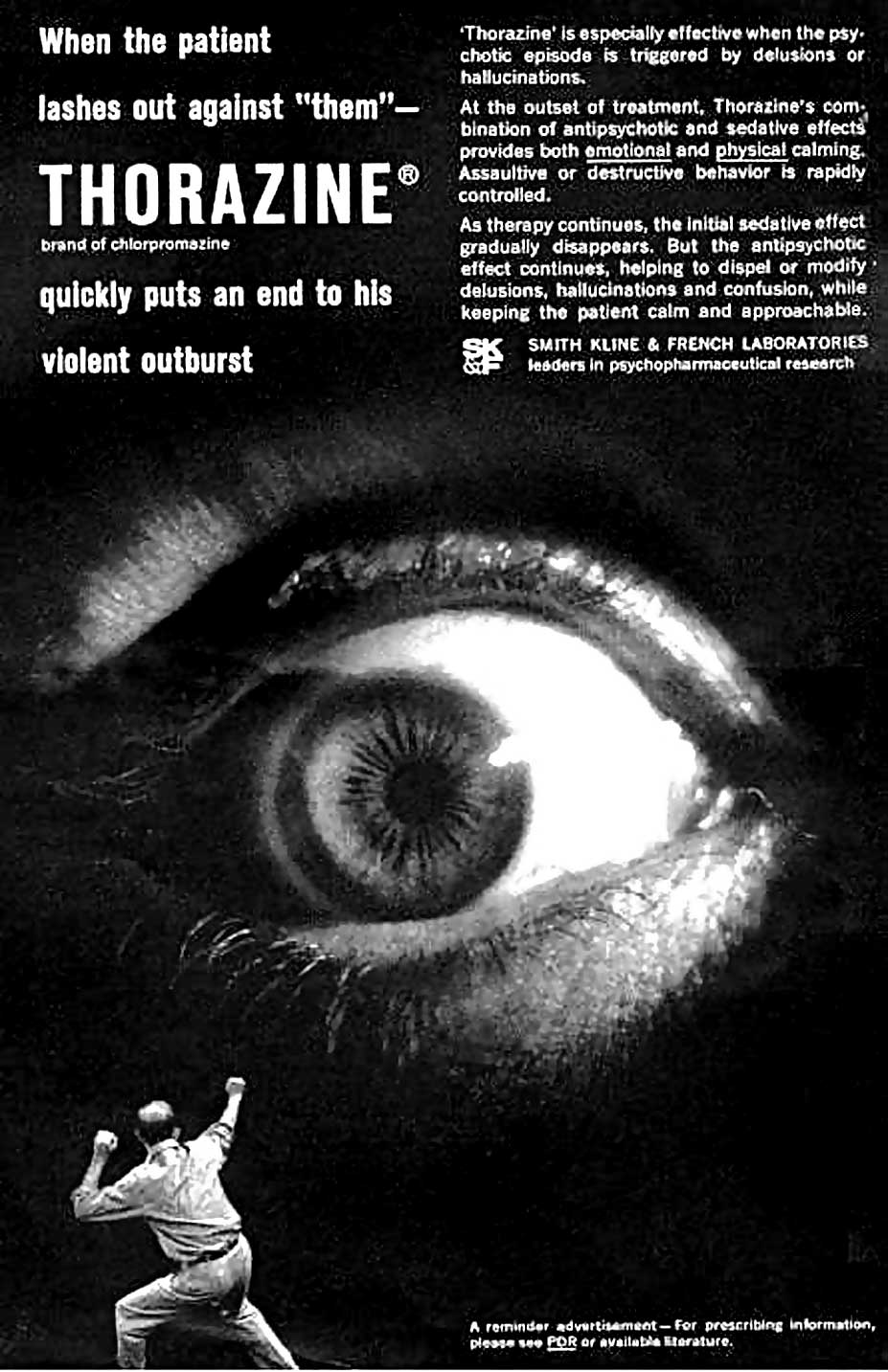

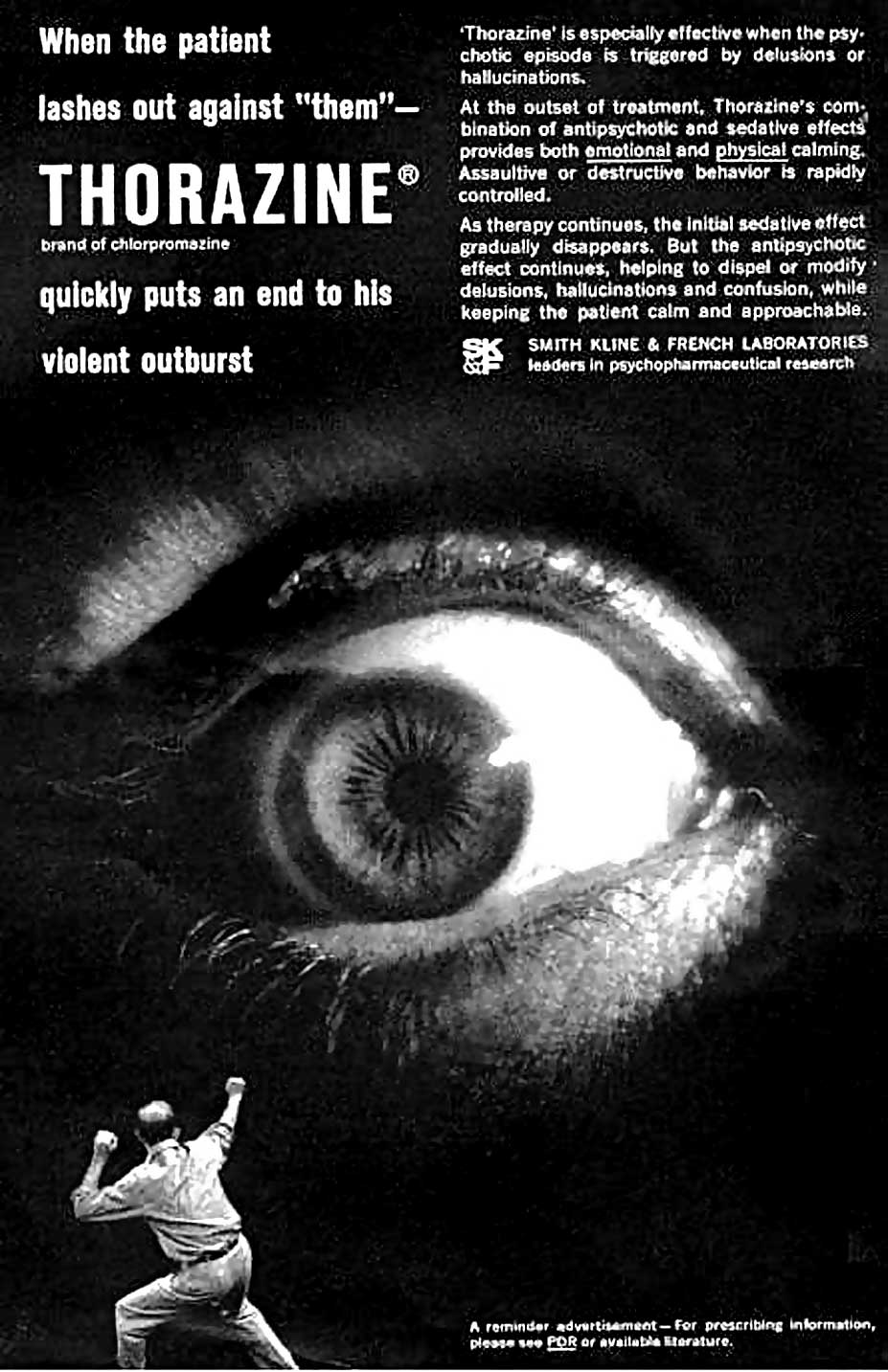

The 20thcentury saw the development of the first effective psychiatric drugs. The first anti-psychotic drug,chlorpromazine

Chlorpromazine (CPZ), marketed under the brand names Thorazine and Largactil among others, is an antipsychotic medication. It is primarily used to treat psychotic disorders such as schizophrenia. Other uses include the treatment of bipolar d ...

(known under the trade name Largactil in Europe and Thorazine in the United States), was first synthesized in France in 1950. Pierre Deniker, a psychiatrist of the Saint-Anne Psychiatric Center in Paris, is credited with first recognising the specificity of action of the drug in psychosis in 1952. Deniker traveled with a colleague to the United States and Canada promoting the drug at medical conferences in 1954. The first publication regarding its use in North America was made in the same year by the Canadian psychiatrist Heinz Lehmann, who was based in Montreal

Montreal is the List of towns in Quebec, largest city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Quebec, the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-largest in Canada, and the List of North American cit ...

. Also in 1954 another antipsychotic, reserpine

Reserpine is a drug that is used for the treatment of hypertension, high blood pressure, usually in combination with a thiazide diuretic or vasodilator. Large clinical trials have shown that combined treatment with reserpine plus a thiazide diur ...

, was first used by an American psychiatrist based in New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

New York may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* ...

, Nathan S. Kline. At a Paris-based colloquium on neuroleptics

Antipsychotics, previously known as neuroleptics and major tranquilizers, are a class of psychotropic medication primarily used to manage psychosis (including delusions, hallucinations, paranoia or disordered thought), principally in schizoph ...

(antipsychotics) in 1955 a series of psychiatric studies were presented by, among others, Hans Hoff

Hans Harald Hoff, (born 9 April 1963),Ratsit: Hans Hoff

Oct ...

(Vienna), Dr. Ihsan Aksel (Istanbul), Felix Labarth (Basle), Linford Rees (London), Sarro (Barcelona), Oct ...

Manfred Bleuler Manfred Bleuler (4 January 1903 – 4 November 1994) was a Swiss physician and psychiatrist. Following in the footsteps of his father, doctoral supervisor, and colleague, Eugen Bleuler, Manfred Bleuler was devoted primarily to the study and treatmen ...

(Zurich), Willi Mayer-Gross (Birmingham), Winford (Washington) and Denber (New York) attesting to the effective and concordant action of the new drugs in the treatment of psychosis.

The new antipsychotics had an immense impact on the lives of psychiatrists and patients. For instance, Henri Ey, a French psychiatrist at Bonneval, related that between 1921 and 1937 only 6% of patients with schizophrenia and chronic delirium were discharged from his institution. The comparable figure for the period from 1955 to 1967, after the introduction of chlorpromazine, was 67%. Between 1955 and 1968 the residential psychiatric population in the United States dropped by 30%. Newly developed

The new antipsychotics had an immense impact on the lives of psychiatrists and patients. For instance, Henri Ey, a French psychiatrist at Bonneval, related that between 1921 and 1937 only 6% of patients with schizophrenia and chronic delirium were discharged from his institution. The comparable figure for the period from 1955 to 1967, after the introduction of chlorpromazine, was 67%. Between 1955 and 1968 the residential psychiatric population in the United States dropped by 30%. Newly developed antidepressants

Antidepressants are a class of medications used to treat major depressive disorder, anxiety disorders, chronic pain, and addiction.

Common side effects of antidepressants include dry mouth, weight gain, dizziness, headaches, akathisia, sexu ...

were used to treat cases of depression, and the introduction of muscle relaxants

A muscle relaxant is a drug that affects skeletal muscle function and decreases the muscle tone. It may be used to alleviate symptoms such as muscle spasms, pain, and hyperreflexia. The term "muscle relaxant" is used to refer to two major therapeu ...

allowed ECT to be used in a modified form for the treatment of severe depression and a few other disorders.

The discovery of the mood stabilizing effect of lithium carbonate

Lithium carbonate is an inorganic compound, the lithium salt of carbonic acid with the chemical formula, formula . This white Salt (chemistry), salt is widely used in processing metal oxides. It is on the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines, Wor ...

by John Cade

John Frederick Joseph Cade AO (18 January 1912 – 16 November 1980) was an Australian psychiatrist who in 1948 discovered the effects of lithium carbonate as a mood stabilizer in the treatment of bipolar disorder, then known as manic depressi ...

in 1948 would eventually revolutionise the treatment of bipolar disorder

Bipolar disorder (BD), previously known as manic depression, is a mental disorder characterized by periods of Depression (mood), depression and periods of abnormally elevated Mood (psychology), mood that each last from days to weeks, and in ...

, although its use was banned in the United States until the 1970s.

United States: reform in the 1940s

From 1942 to 1947,conscientious objectors

A conscientious objector is an "individual who has claimed the right to refuse to perform military service" on the grounds of freedom of conscience or freedom of religion, religion. The term has also been extended to objecting to working for ...

in the US assigned to psychiatric hospitals under Civilian Public Service

The Civilian Public Service (CPS) was a program of the United States government that provided conscientious objectors with an alternative service, alternative to military service during World War II. From 1941 to 1947, nearly 12,000 draftees, wil ...

exposed abuses throughout the psychiatric care system and were instrumental in reforms of the 1940s and 1950s. The CPS reformers were especially active at the Philadelphia State Hospital where four Quakers

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestantism, Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations. Members refer to each other as Friends after in the Bible, and originally ...

initiated ''The Attendant'' magazine as a way to communicate ideas and promote reform. This periodical later became ''The Psychiatric Aide'', a professional journal for mental health workers. On 6 May 1946, ''Life

Life, also known as biota, refers to matter that has biological processes, such as Cell signaling, signaling and self-sustaining processes. It is defined descriptively by the capacity for homeostasis, Structure#Biological, organisation, met ...

'' magazine printed an exposé of the psychiatric system by Albert Q. Maisel based on the reports of COs. Another effort of CPS, namely the ''Mental Hygiene Project'', became the national Mental Health Foundation. Initially skeptical about the value of Civilian Public Service, Eleanor Roosevelt

Anna Eleanor Roosevelt ( ; October 11, 1884November 7, 1962) was an American political figure, diplomat, and activist. She was the longest-serving First Lady of the United States, first lady of the United States, during her husband Franklin D ...

, impressed by the changes introduced by COs in the mental health system, became a sponsor of ''the National Mental Health Foundation'' and actively inspired other prominent citizens including Owen J. Roberts, Pearl Buck

Pearl Comfort Sydenstricker Buck (June 26, 1892 – March 6, 1973) was an American writer and novelist. She is best known for ''The Good Earth'', the best-selling novel in the United States in 1931 and 1932 and which won her the Pulitzer Prize ...

and Harry Emerson Fosdick

Harry Emerson Fosdick (May 24, 1878 – October 5, 1969) was an American pastor. Fosdick became a central figure in the fundamentalist–modernist controversy within American Protestantism in the 1920s and 1930s and was one of the most prominen ...

to join her in advancing the organization's objectives of reform and humane treatment of patients.

Deinstitutionalisation

By the beginning of the 20thcentury, ever-increasing admissions had resulted in serious overcrowding. Funding was often cut, especially during periods of economic decline, and during wartime in particular many patients starved to death. Asylums became notorious for poor living conditions, lack of hygiene, overcrowding, and ill-treatment and abuse of patients. The first community-based alternatives were suggested and tentatively implemented in the 1920s and 1930s, although asylum numbers continued to increase up to the 1950s. The movement for deinstitutionalisation came to the fore in various Western countries in the 1950s and 1960s. The prevailing public arguments, time of onset, and pace of reforms varied by country.Class action lawsuit

A class action

A class action is a form of lawsuit.

Class Action may also refer to:

* ''Class Action'' (film), 1991, starring Gene Hackman and Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio

* Class Action (band), a garage house band

* "Class Action" (''Teenage R ...

s in the United States, and the scrutiny of institutions through disability activism and antipsychiatry, helped expose the poor conditions and treatment. Sociologists and others argued that such institutions maintained or created dependency, passivity, exclusion and disability, causing people to be institutionalised.

There was an argument that community services would be cheaper. It was suggested that new psychiatric medications made it more feasible to release people into the community.

There were differing views on deinstitutionalization, however, in groups such as mental health professionals, public officials, families, advocacy groups, public citizens and unions.

Today

Africa

* Uganda had one psychiatric hospital as of 2007. * South Africa had 27 registered psychiatric hospitals as of 2018. These hospitals are spread throughout the country. Some of the most well-known institutions are: Weskoppies Psychiatric Hospital, colloquially known as Groendakkies ("Little Green Roofs") and Denmar Psychiatric Hospital in Pretoria, TARA in Johannesburg, and Valkenberg Hospital in Cape Town.Asia

In Japan, the number of hospital beds has risen steadily over the last few decades. In Hong Kong, a number of residential care services such as half-way houses, long-stay care homes, and supported hostels are provided for the discharged patients. In addition, a number of community support services such as Community Rehabilitation Day Services, Community Mental Health Link, Community Mental Health Care, etc. have been launched to facilitate the re-integration of patients into the community.Europe

Countries where deinstitutionalisation has happened may be experiencing a process of "re-institutionalisation" or relocation to different institutions, as evidenced by increases in the number ofsupported housing

Supportive housing is a combination of housing and services intended as a cost-effective way to help people live more stable, productive lives, and is an active "community services and funding" stream across the United States. It was developed by ...

facilities, forensic psychiatric beds and rising numbers in the prison population.

New Zealand

New Zealand established areconciliation

Reconciliation or reconcile may refer to:

Accounting

* Reconciliation (accounting)

Arts, entertainment, and media Books

* Reconciliation (Under the North Star), ''Reconciliation'' (''Under the North Star''), the third volume of the ''Under the ...

initiative in 2005 in the context of ongoing compensation payouts to ex-patients of state-run mental institutions in the 1970s to 1990s. The forum heard of poor reasons for admissions; unsanitary and overcrowded conditions; lack of communication to patients and family members; physical violence and sexual misconduct and abuse; inadequate complaints mechanisms; pressures and difficulties for staff, within an authoritarian

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political ''status quo'', and reductions in democracy, separation of powers, civil liberties, and ...

psychiatric

Psychiatry is the medical specialty devoted to the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of deleterious mental conditions. These include matters related to cognition, perceptions, mood, emotion, and behavior.

Initial psychiatric assessment of ...

hierarchy based on containment; fear and humiliation in the misuse of seclusion; over-use and abuse of ECT, psychiatric medication

A psychiatric or psychotropic medication is a psychoactive drug taken to exert an effect on the chemical makeup of the brain and nervous system. Thus, these medications are used to treat mental illnesses. These medications are typically made of ...

and other treatments/punishments, including group therapy

Group psychotherapy or group therapy is a form of psychotherapy in which one or more therapists treat a small group of clients together as a group. The term can legitimately refer to any form of psychotherapy when delivered in a group format, i ...

, with continued adverse effects

An adverse effect is an undesired harmful effect resulting from a medication or other intervention, such as surgery. An adverse effect may be termed a "side effect", when judged to be secondary to a main or therapeutic effect. The term complic ...