Lunar Terrain on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Selenography is the study of the surface and physical features of the

Selenography is the study of the surface and physical features of the

The word" selenography" is derived from the

The word" selenography" is derived from the

The oldest known illustration of the Moon was found in a

The oldest known illustration of the Moon was found in a  In 1647,

In 1647,

The following historically notable lunar maps and atlases are arranged in chronological order by publication date.

*

The following historically notable lunar maps and atlases are arranged in chronological order by publication date.

*

NASA Catalogue of Lunar Nomenclature

(1982), Leif E. Andersson and Ewen A. Whitaker

Observing the Moon: The Modern Astronomer's GuideLunar control networks (USGS)

, Kevin S. Jung

Consolidated Lunar Atlas

Virtual exhibition about the topography of the Moon

on the digital library of

Selenography is the study of the surface and physical features of the

Selenography is the study of the surface and physical features of the Moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It Orbit of the Moon, orbits around Earth at Lunar distance, an average distance of (; about 30 times Earth diameter, Earth's diameter). The Moon rotation, rotates, with a rotation period (lunar ...

(also known as geography of the Moon, or selenodesy). Like geography

Geography (from Ancient Greek ; combining 'Earth' and 'write', literally 'Earth writing') is the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, and phenomena of Earth. Geography is an all-encompassing discipline that seeks an understanding o ...

and areography

Areography, also known as the geography of Mars, is a subfield of planetary science that entails the delineation and characterization of regions on Mars. Areography is mainly focused on what is called physical geography on Earth; that is the di ...

, selenography is a subdiscipline within the field of planetary science

Planetary science (or more rarely, planetology) is the scientific study of planets (including Earth), celestial bodies (such as moons, asteroids, comets) and planetary systems (in particular those of the Solar System) and the processes of ...

. Historically, the principal concern of selenographists was the mapping and naming of the lunar terrane identifying maria, crater

A crater is a landform consisting of a hole or depression (geology), depression on a planetary surface, usually caused either by an object hitting the surface, or by geological activity on the planet. A crater has classically been described ...

s, mountain ranges, and other various features. This task was largely finished when high resolution images of the near

NEAR or Near may refer to:

People

* Thomas J. Near, US evolutionary ichthyologist

* Near, a developer who created the higan emulator

Science, mathematics, technology, biology, and medicine

* National Emergency Alarm Repeater (NEAR), a form ...

and far sides of the Moon were obtained by orbiting spacecraft during the early space era. Nevertheless, some regions of the Moon remain poorly imaged (especially near the poles) and the exact locations of many features (like crater depth

The depth of an impact crater in a solid planet or moon

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It Orbit of the Moon, orbits around Earth at Lunar distance, an average distance of (; about 30 times Earth diameter, Earth's diameter). ...

s) are uncertain by several kilometers. Today, selenography is considered to be a subdiscipline of selenology, which itself is most often referred to as simply "lunar science."

History

The word" selenography" is derived from the

The word" selenography" is derived from the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

word ''Σελήνη'' (Selene, meaning Moon) and ''γράφω'' (graphō, meaning to write).

The idea that the Moon is not perfectly smooth originates to at least , when Democritus

Democritus (, ; , ''Dēmókritos'', meaning "chosen of the people"; – ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek Pre-Socratic philosophy, pre-Socratic philosopher from Abdera, Thrace, Abdera, primarily remembered today for his formulation of an ...

asserted that the Moon's "lofty mountains and hollow valleys" were the cause of its markings. However, not until the end of the 15th century AD did serious selenography begin. Around AD 1603, William Gilbert made the first lunar drawing based on naked-eye observation. Others soon followed, and when the telescope

A telescope is a device used to observe distant objects by their emission, Absorption (electromagnetic radiation), absorption, or Reflection (physics), reflection of electromagnetic radiation. Originally, it was an optical instrument using len ...

was invented, initial drawings of poor accuracy were made, but soon thereafter improved in tandem with optics

Optics is the branch of physics that studies the behaviour and properties of light, including its interactions with matter and the construction of optical instruments, instruments that use or Photodetector, detect it. Optics usually describes t ...

. In the early 18th century, the libration

In lunar astronomy, libration is the cyclic variation in the apparent position of the Moon that is perceived by observers on the Earth and caused by changes between the orbital and rotational planes of the moon. It causes an observer to see ...

s of the Moon were measured, which revealed that more than half of the lunar surface was visible to observers on Earth. In 1750, Johann Meyer produced the first reliable set of lunar coordinates

In geometry, a coordinate system is a system that uses one or more numbers, or coordinates, to uniquely determine and standardize the Position (geometry), position of the Point (geometry), points or other geometric elements on a manifold such as ...

that permitted astronomers to locate lunar features.

Lunar mapping became systematic in 1779 when Johann Schröter

Johann, typically a male given name, is the German form of ''Iohannes'', which is the Latin form of the Greek name ''Iōánnēs'' (), itself derived from Hebrew name '' Yochanan'' () in turn from its extended form (), meaning "Yahweh is Gracious ...

began meticulous observation and measurement of lunar topography

Topography is the study of the forms and features of land surfaces. The topography of an area may refer to the landforms and features themselves, or a description or depiction in maps.

Topography is a field of geoscience and planetary sci ...

. In 1834 Johann Heinrich von Mädler

Johann Heinrich von Mädler (29 May 1794, Berlin – 14 March 1874, Hannover) was a German astronomer.

Life and work

His father was a master tailor and when 12 he studied at the Friedrich‐Werdersche Gymnasium in Berlin. He was orphaned at ag ...

published the first large cartograph (map) of the Moon, comprising 4 sheets, and he subsequently published ''The Universal Selenography''. All lunar measurement was based on direct observation until March 1840, when J.W. Draper, using a 5-inch reflector, produced a daguerreotype

Daguerreotype was the first publicly available photography, photographic process, widely used during the 1840s and 1850s. "Daguerreotype" also refers to an image created through this process.

Invented by Louis Daguerre and introduced worldwid ...

of the Moon and thus introduced photography to astronomy

Astronomy is a natural science that studies celestial objects and the phenomena that occur in the cosmos. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and their overall evolution. Objects of interest includ ...

. At first, the images were of very poor quality, but as with the telescope

A telescope is a device used to observe distant objects by their emission, Absorption (electromagnetic radiation), absorption, or Reflection (physics), reflection of electromagnetic radiation. Originally, it was an optical instrument using len ...

200 years earlier, their quality rapidly improved. By 1890 lunar photography had become a recognized subdiscipline of astronomy.

Lunar photography

The 20th century witnessed more advances in selenography. In 1959, theSoviet

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

spacecraft Luna 3

Luna 3, or E-2A No.1 (), was a Soviet spacecraft launched in 1959 as part of the Luna programme. It was the first mission to photograph the far side of the Moon and the third Soviet space probe to be sent to the neighborhood of the Moon. The hi ...

transmitted the first photographs of the far side of the Moon

The far side of the Moon is the hemisphere of the Moon that is facing away from Earth, the opposite hemisphere is the near side. It always has the same surface oriented away from Earth because of synchronous rotation in the Moon's orbit. C ...

, giving the first view of it in history. The United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

launched the Ranger spacecraft between 1961 and 1965 to photograph the lunar surface until the instant they impacted it, the Lunar Orbiters between 1966 and 1967 to photograph the Moon from orbit, and the Surveyors

Surveying or land surveying is the technique, profession, art, and science of determining the terrestrial two-dimensional or three-dimensional positions of points and the distances and angles between them. These points are usually on the ...

between 1966 and 1968 to photograph and softly land on the lunar surface. The Soviet Lunokhod

Lunokhod ( rus, Луноход, p=lʊnɐˈxot, "Moonwalker") was a series of Soviet robotic lunar rovers designed to land on the Moon between 1969 and 1977. Lunokhod 1 was the first roving remote-controlled robot to land on an extraterrestrial ...

s 1 (1970) and 2 (1973) traversed almost 50 km of the lunar surface, making detailed photographs of the lunar surface. The Clementine

A clementine (''Citrus × clementina'') is a tangor, a citrus fruit hybrid between a willowleaf mandarin orange ( ''C.'' × ''deliciosa'') and a sweet orange (''C. × sinensis''), named in honor of Clément Rodier, a French missionary who f ...

spacecraft obtained the first nearly global cartograph (map) of the lunar topography

Topography is the study of the forms and features of land surfaces. The topography of an area may refer to the landforms and features themselves, or a description or depiction in maps.

Topography is a field of geoscience and planetary sci ...

, and also multispectral images. Successive missions transmitted photographs of increasing resolution.

Lunar topography

The Moon has been measured by the methods of laser altimetry and stereo image analysis, including data obtained during several missions. The most visibletopographical

Topography is the study of the forms and features of land surfaces. The topography of an area may refer to the landforms and features themselves, or a description or depiction in maps.

Topography is a field of geoscience and planetary scienc ...

feature is the giant far-side South Pole-Aitken basin

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both west and east.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþaz ...

, which possesses the lowest elevation

The elevation of a geographic location (geography), ''location'' is its height above or below a fixed reference point, most commonly a reference geoid, a mathematical model of the Earth's sea level as an equipotential gravitational equipotenti ...

s of the Moon. The highest elevations are found just to the northeast of this basin, and it has been suggested that this area might represent thick ejecta

Ejecta (; ) are particles ejected from an area. In volcanology, in particular, the term refers to particles including pyroclastic rock, pyroclastic materials (tephra) that came out of a explosive eruption, volcanic explosion and magma eruption v ...

deposits that were emplaced during an oblique South Pole-Aitken basin impact event. Other large impact basins, such as the maria Imbrium, Serenitatis, Crisium, Smythii, and Orientale, also possess regionally low elevations and elevated rims.

Another distinguishing feature of the Moon's shape is that the elevations are on average about 1.9 km higher on the far side than the near side. If it is assumed that the crust is in isostatic equilibrium, and that the density of the crust is everywhere the same, then the higher elevations would be associated with a thicker crust. Using gravity, topography and seismic

Seismology (; from Ancient Greek σεισμός (''seismós'') meaning "earthquake" and -λογία (''-logía'') meaning "study of") is the scientific study of earthquakes (or generally, quakes) and the generation and propagation of elastic ...

data, the crust is thought to be on average about thick, with the far-side crust being on average thicker than the near side by about 15 km.

Lunar cartography and toponymy

The oldest known illustration of the Moon was found in a

The oldest known illustration of the Moon was found in a passage grave

A passage grave or passage tomb consists of one or more burial chambers covered in earth or stone and having a narrow access passage made of large stones. These structures usually date from the Neolithic Age and are found largely in Western Europ ...

in Knowth

Knowth (; ) is a prehistoric tomb overlooking the River Boyne in County Meath, Ireland. It comprises a large passage tomb surrounded by 17 smaller tombs, built during the Neolithic era around 3200 BC. It contains the largest assemblage of megali ...

, County Meath

County Meath ( ; or simply , ) is a Counties of Ireland, county in the Eastern and Midland Region of Republic of Ireland, Ireland, within the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster. It is bordered by County Dublin to the southeast, County ...

, Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

. The tomb was carbon dated

Radiocarbon dating (also referred to as carbon dating or carbon-14 dating) is a method for determining the age of an object containing organic material by using the properties of radiocarbon, a radioactive isotope of carbon.

The method was ...

to 3330–2790 BC. Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (15 April 1452 - 2 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. While his fame initially rested o ...

made and annotated some sketches of the Moon in c. 1500. William Gilbert made a drawing of the Moon in which he denominated a dozen surface features in the late 16th century; it was published posthumously in ''De Mondo Nostro Sublunari Philosophia Nova''. After the invention of the telescope

A telescope is a device used to observe distant objects by their emission, Absorption (electromagnetic radiation), absorption, or Reflection (physics), reflection of electromagnetic radiation. Originally, it was an optical instrument using len ...

, Thomas Harriot

Thomas Harriot (; – 2 July 1621), also spelled Harriott, Hariot or Heriot, was an English astronomer, mathematician, ethnographer and translator to whom the theory of refraction is attributed. Thomas Harriot was also recognized for his con ...

(1609), Galileo Galilei

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642), commonly referred to as Galileo Galilei ( , , ) or mononymously as Galileo, was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a poly ...

(1609), and Christoph Scheiner

Christoph Scheiner (25 July 1573 (or 1575) – 18 June 1650) was a Jesuit priest, physicist and astronomer in Ingolstadt.

Biography Augsburg/Dillingen: 1591–1605

Scheiner was born in Markt Wald near Mindelheim in Swabia, earlier margravate Burg ...

(1614) made drawings also.

Denominations of the surface features of the Moon, based on telescopic observation, were made by Michael van Langren

Michael van Langren (April 1598 May 1675) was an astronomer and cartographer of the Low Countries. A Catholic, he chiefly found employment in service to the Spanish Monarchy.

Family

Michael van Langren was the youngest member of a family of Du ...

in 1645. Many of his denominations were distinctly Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

, denominating craters in honor of Catholic royalty

Royalty may refer to:

* the mystique/prestige bestowed upon monarchs

** one or more monarchs, such as kings, queens, emperors, empresses, princes, princesses, etc.

*** royal family, the immediate family of a king or queen-regnant, and sometimes h ...

and capes and promontories in honor of Catholic saint

In Christianity, Christian belief, a saint is a person who is recognized as having an exceptional degree of sanctification in Christianity, holiness, imitation of God, likeness, or closeness to God in Christianity, God. However, the use of the ...

s. The lunar ''maria'' were denominated in Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

for terrestrial seas and oceans. Minor craters were denominated in honor of astronomers, mathematicians, and other famous scholars. In 1647,

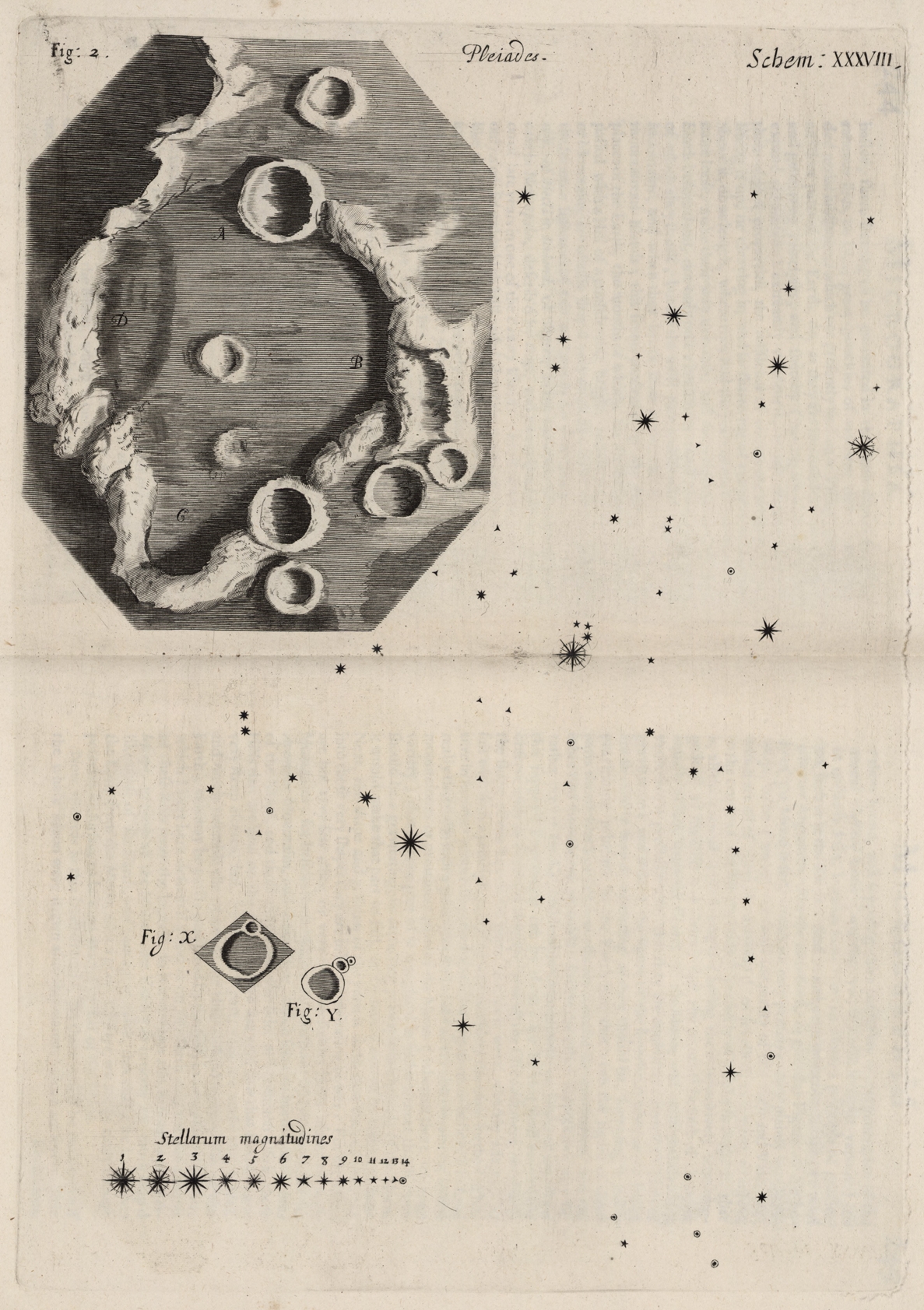

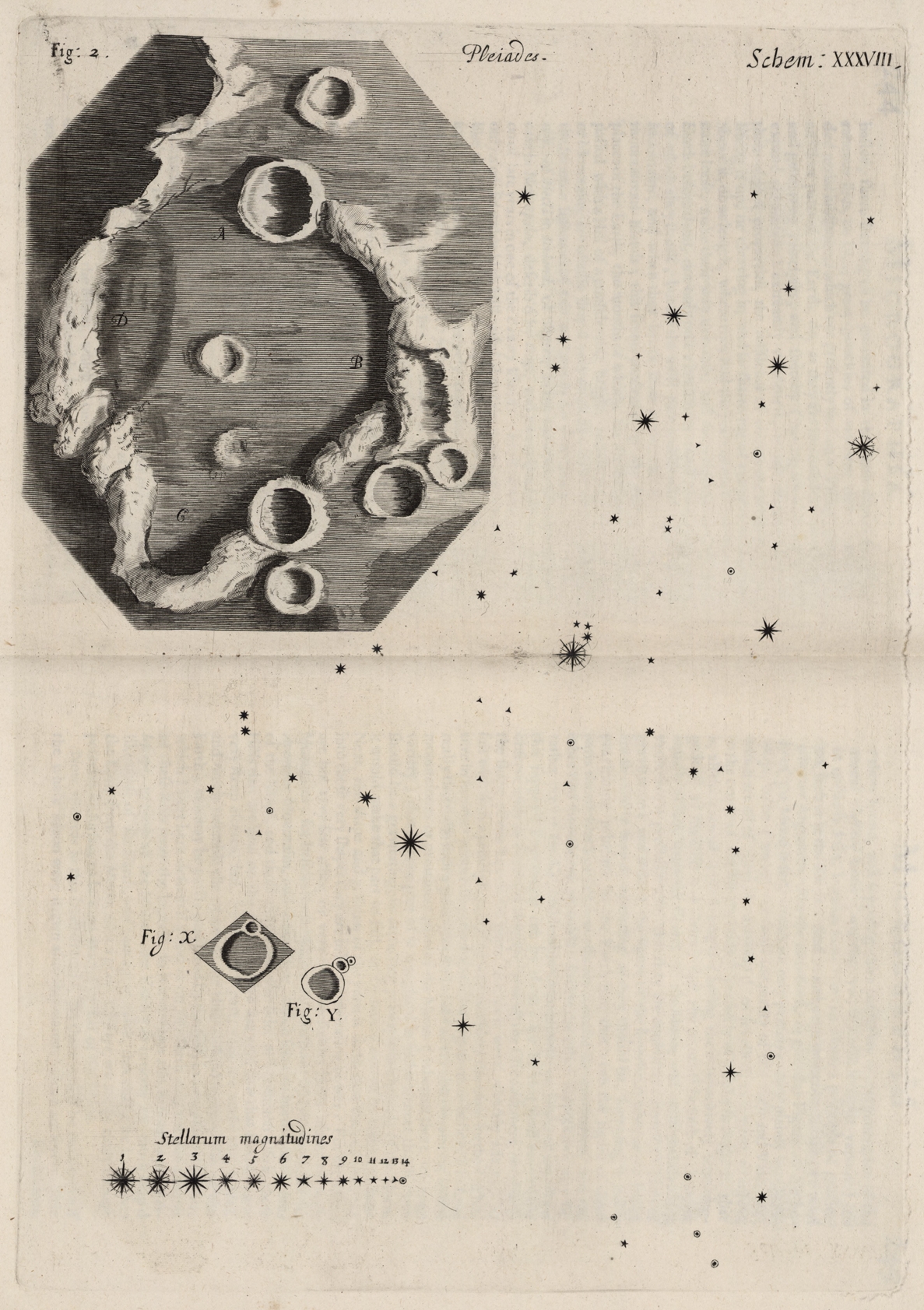

In 1647, Johannes Hevelius

Johannes Hevelius

Some sources refer to Hevelius as Polish:

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

Some sources refer to Hevelius as German:

*

*

*

*

*of the Royal Society

* (in German also known as ''Hevel''; ; – 28 January 1687) was a councillor and mayor of Danz ...

produced the rival work ''Selenographia

''Selenographia, sive Lunae descriptio'' (''Selenography, or A Description of The Moon'') was printed in 1647 and is a milestone work by Johannes Hevelius. It includes the first detailed map of the Moon, created from Hevelius's personal observati ...

'', which was the first lunar atlas. Hevelius ignored the nomenclature of Van Langren and instead denominated the lunar topography

Topography is the study of the forms and features of land surfaces. The topography of an area may refer to the landforms and features themselves, or a description or depiction in maps.

Topography is a field of geoscience and planetary sci ...

according to terrestrial features, such that the names of lunar features corresponded to the toponyms of their geographical terrestrial counterparts, especially as the latter were denominated by the ancient Roman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of Roman civilization

*Epistle to the Romans, shortened to Romans, a letter w ...

and Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

civilizations. This work of Hevelius influenced his contemporary European astronomers, and the ''Selenographia'' was the standard reference on selenography for over a century.

Giambattista Riccioli, SJ, a Catholic priest

The priesthood is the office of the ministers of religion, who have been commissioned ("ordained") with the holy orders of the Catholic Church. Technically, bishops are a priestly order as well; however, in common English usage ''priest'' refe ...

and scholar who lived in northern Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

authored the present scheme of Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

lunar nomenclature. His '' Almagestum novum'' was published in 1651 as summary of then current astronomical thinking and recent developments. In particular he outlined the arguments in favor of and against various cosmological models, both heliocentric and geocentric. ''Almagestum Novum'' contained scientific reference matter based on contemporary knowledge, and contemporary educators across Europe widely used it. Although this handbook of astronomy has long since been superseded, its system of lunar nomenclature is used even today.

The lunar illustrations in the ''Almagestum novum'' were drawn by a fellow Jesuit

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

educator named Francesco Grimaldi, SJ. The nomenclature was based on a subdivision of the visible lunar surface into octants that were numbered in Roman style from I to VIII. Octant I referenced the northwest section and subsequent octants proceeded clockwise in alignment with compass directions. Thus Octant VI was to the south and included Clavius

Christopher Clavius, (25 March 1538 – 6 February 1612) was a Jesuit German mathematician, head of mathematicians at the , and astronomer who was a member of the Vatican commission that accepted the proposed calendar invented by Aloysius ...

and Tycho Craters.

The Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

nomenclature had two components: the first denominated the broad features of ''terrae'' (lands) and ''maria'' (seas) and the second denominated the craters. Riccioli authored lunar toponym

Toponymy, toponymics, or toponomastics is the study of ''wikt:toponym, toponyms'' (proper names of places, also known as place names and geographic names), including their origins, meanings, usage, and types. ''Toponym'' is the general term for ...

s derived from the names of various conditions, including climactic ones, whose causes were historically attributed to the Moon. Thus there were the seas of crises ("Mare Crisium"), serenity ("Mare Serenitatis"), and fertility ("Mare Fecunditatis"). There were also the seas of rain ("Mare Imbrium"), clouds ("Mare Nubium"), and cold ("Mare Frigoris"). The topographical features between the ''maria'' were comparably denominated, but were opposite the toponyms of the ''maria''. Thus there were the lands of sterility ("Terra Sterilitatis"), heat ("Terra Caloris"), and life ("Terra Vitae"). However, these names for the highland regions were supplanted on later cartographs (maps). See ''List of features on the Moon

The geology of the Moon, surface of the Moon has many features, including mountains and valleys, craters, and ''maria''—wide flat areas that look like seas from a distance but are probably solidified molten rock. Some of these features are listed ...

'' for a complete list.

Many of the craters were denominated topically pursuant to the octant in which they were located. Craters in Octants I, II, and III were primarily denominated based on names from ancient Greece

Ancient Greece () was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity (), that comprised a loose collection of culturally and linguistically r ...

, such as Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

, Atlas

An atlas is a collection of maps; it is typically a bundle of world map, maps of Earth or of a continent or region of Earth. Advances in astronomy have also resulted in atlases of the celestial sphere or of other planets.

Atlases have traditio ...

, and Archimedes

Archimedes of Syracuse ( ; ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek Greek mathematics, mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and Invention, inventor from the ancient city of Syracuse, Sicily, Syracuse in History of Greek and Hellenis ...

. Toward the middle in Octants IV, V, and VI craters were denominated based on names from the ancient Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

, such as Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (12 or 13 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in Caesar's civil wa ...

, Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historians by modern scholars.

Tacitus’ two major historical works, ''Annals'' ( ...

, and Taruntius. Toward the southern half of the lunar cartograph (map) craters were denominated in honor of scholars, writers, and philosophers

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, value, mind, and language. It is a rational and critical inquiry that reflects on ...

of medieval Europe

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of World history (field), global history. It began with the fall of the West ...

and Arabic regions. The outer extremes of Octants V, VI, and VII, and all of Octant VIII were denominated in honor of contemporaries of Giambattista Riccioli. Features of Octant VIII were also denominated in honor of Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath who formulated a mathematical model, model of Celestial spheres#Renaissance, the universe that placed heliocentrism, the Sun rather than Earth at its cen ...

, Kepler

Johannes Kepler (27 December 1571 – 15 November 1630) was a German astronomer, mathematician, astrologer, natural philosopher and writer on music. He is a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution, best known for his laws of p ...

, and Galileo

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642), commonly referred to as Galileo Galilei ( , , ) or mononymously as Galileo, was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a poly ...

. These persons were "banished" to it far from the "ancients," as a gesture to the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

. Many craters around the Mare Nectaris

Mare Nectaris (Latin ''nectaris'', the "Sea of Nectar") is a small lunar mare or sea (a volcanic lava plain noticeably darker than the rest of the Moon's surface) located south of Mare Tranquillitatis southwest of Mare Fecunditatis, on the near ...

were denominated in honor of Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

saint

In Christianity, Christian belief, a saint is a person who is recognized as having an exceptional degree of sanctification in Christianity, holiness, imitation of God, likeness, or closeness to God in Christianity, God. However, the use of the ...

s pursuant to the nomenclature of Van Langren. All of them were, however, connected in some mode with astronomy

Astronomy is a natural science that studies celestial objects and the phenomena that occur in the cosmos. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and their overall evolution. Objects of interest includ ...

. Later cartographs (maps) removed the "St." from their toponym

Toponymy, toponymics, or toponomastics is the study of ''wikt:toponym, toponyms'' (proper names of places, also known as place names and geographic names), including their origins, meanings, usage, and types. ''Toponym'' is the general term for ...

s.

The lunar nomenclature of Giambattista Riccioli was widely used after the publication of his ''Almagestum Novum'', and many of its toponyms are presently used. The system was scientifically inclusive and was considered eloquent and poetic in style, and therefore it appealed widely to his contemporaries. It was also readily extensible with new toponyms for additional features. Thus it replaced the nomenclature of Van Langren and Hevelius.

Later astronomers and lunar cartographers augmented the nomenclature with additional toponym

Toponymy, toponymics, or toponomastics is the study of ''wikt:toponym, toponyms'' (proper names of places, also known as place names and geographic names), including their origins, meanings, usage, and types. ''Toponym'' is the general term for ...

s. The most notable among these contributors was Johann H. Schröter, who published a very detailed cartograph (map) of the Moon in 1791 titled the ''Selenotopografisches Fragmenten''. Schröter's adoption of Riccioli's nomenclature perpetuated it as the universally standard lunar nomenclature. A vote of the International Astronomical Union

The International Astronomical Union (IAU; , UAI) is an international non-governmental organization (INGO) with the objective of advancing astronomy in all aspects, including promoting astronomical research, outreach, education, and developmen ...

(IAU) in 1935 established the lunar nomenclature of Riccioli

Giovanni Battista Riccioli (17 April 1598 – 25 June 1671) was an Italian astronomer and a Catholic priest in the Jesuit order. He is known, among other things, for his experiments with pendulums and with falling bodies, for his discussion of ...

, which included 600 lunar toponyms, as universally official and doctrinal.

The IAU later expanded and updated the lunar nomenclature in the 1960s, but new toponyms were limited to toponyms honoring deceased scientists. After Soviet

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

spacecraft photographed the far side of the Moon, many of the newly discovered features were denominated in honor of Soviet scientists and engineers. The IAU

The International Astronomical Union (IAU; , UAI) is an international non-governmental organization (INGO) with the objective of advancing astronomy in all aspects, including promoting astronomical research, outreach, education, and developmen ...

assigned all subsequent new lunar toponyms. Some craters were denominated in honor of space explorers.

Satellite craters

Johann H. Mädler authored the nomenclature for satellite craters. The subsidiary craters surrounding a major crater were identified by a letter. These subsidiary craters were usually smaller than the crater with which they were associated, with some exceptions. The craters could be assigned letters "A" through "Z," with "I" omitted. Because the great majority of thetoponym

Toponymy, toponymics, or toponomastics is the study of ''wikt:toponym, toponyms'' (proper names of places, also known as place names and geographic names), including their origins, meanings, usage, and types. ''Toponym'' is the general term for ...

s of craters were masculine, the major craters were generically denominated "patronymic

A patronymic, or patronym, is a component of a personal name based on the given name of one's father, grandfather (more specifically an avonymic), or an earlier male ancestor. It is the male equivalent of a matronymic.

Patronymics are used, b ...

" craters.

The assignment of the letters to satellite craters was originally somewhat haphazard. Letters were typically assigned to craters in order of significance rather than location. Precedence depended on the angle of illumination from the Sun

The Sun is the star at the centre of the Solar System. It is a massive, nearly perfect sphere of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core, radiating the energy from its surface mainly as visible light a ...

at the time of the telescopic observation, which could change during the lunar day. In many cases the assignments were seemingly random. In a number of cases the satellite crater was located closer to a major crater with which it was not associated. To identify the patronymic crater, Mädler placed the identifying letter to the side of the midpoint of the feature that was closest to the associated major crater. This also had the advantage of permitting omission of the toponym

Toponymy, toponymics, or toponomastics is the study of ''wikt:toponym, toponyms'' (proper names of places, also known as place names and geographic names), including their origins, meanings, usage, and types. ''Toponym'' is the general term for ...

s of the major craters from the cartographs (maps) when their subsidiary features were labelled.

Over time, lunar observers assigned many of the satellite craters an eponym

An eponym is a noun after which or for which someone or something is, or is believed to be, named. Adjectives derived from the word ''eponym'' include ''eponymous'' and ''eponymic''.

Eponyms are commonly used for time periods, places, innovati ...

. The International Astronomical Union

The International Astronomical Union (IAU; , UAI) is an international non-governmental organization (INGO) with the objective of advancing astronomy in all aspects, including promoting astronomical research, outreach, education, and developmen ...

(IAU) assumed authority to denominate lunar features in 1919. The commission for denominating these features formally adopted the convention of using capital Roman letters to identify craters and valleys.

When suitable maps of the far side of the Moon became available by 1966, Ewen Whitaker denominated satellite features based on the angle of their location relative to the major crater with which they were associated. A satellite crater located due north of the major crater was identified as "Z". The full 360° circle around the major crater was then subdivided evenly into 24 parts, like a 24-hour clock. Each "hour" angle, running clockwise, was assigned a letter, beginning with "A" at 1 o'clock. The letters "I" and "O" were omitted, resulting in only 24 letters. Thus a crater due south of its major crater was identified as "M".

Reference elevation

The Moon obviously lacks anymean sea level

A mean is a quantity representing the "center" of a collection of numbers and is intermediate to the extreme values of the set of numbers. There are several kinds of means (or "measures of central tendency") in mathematics, especially in statist ...

to be used as vertical datum

In geodesy, surveying, hydrography and navigation, vertical datum or altimetric datum is a reference coordinate surface used for vertical positions, such as the elevations of Earth-bound features (terrain, bathymetry, water level, and built stru ...

.

The USGS

The United States Geological Survey (USGS), founded as the Geological Survey, is an government agency, agency of the United States Department of the Interior, U.S. Department of the Interior whose work spans the disciplines of biology, geograp ...

's Lunar Orbiter Laser Altimeter (LOLA), an instrument on NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter

The Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) is a NASA robotic spacecraft currently orbiting the Moon in an eccentric Polar orbit, polar mapping orbit. Data collected by LRO have been described as essential for planning NASA's future human and robotic ...

(LRO), employs a digital elevation model

A digital elevation model (DEM) or digital surface model (DSM) is a 3D computer graphics representation of elevation data to represent terrain or overlaying objects, commonly of a planet, Natural satellite, moon, or asteroid. A "global DEM" refer ...

(DEM) that uses the nominal lunar radius

The Moon is Earth's only natural satellite. It Orbit of the Moon, orbits around Earth at Lunar distance, an average distance of (; about 30 times Earth diameter, Earth's diameter). The Moon rotation, rotates, with a rotation period (lunar ...

of .

The selenoid (the geoid

The geoid ( ) is the shape that the ocean surface would take under the influence of the gravity of Earth, including gravitational attraction and Earth's rotation, if other influences such as winds and tides were absent. This surface is exte ...

for the Moon) has been measured gravimetrically by the GRAIL

The Holy Grail (, , , ) is a treasure that serves as an important motif in Arthurian literature. Various traditions describe the Holy Grail as a cup, dish, or stone with miraculous healing powers, sometimes providing eternal youth or sustenanc ...

twin satellites.

Historical lunar maps

The following historically notable lunar maps and atlases are arranged in chronological order by publication date.

*

The following historically notable lunar maps and atlases are arranged in chronological order by publication date.

* Michael van Langren

Michael van Langren (April 1598 May 1675) was an astronomer and cartographer of the Low Countries. A Catholic, he chiefly found employment in service to the Spanish Monarchy.

Family

Michael van Langren was the youngest member of a family of Du ...

, engraved map, 1645.

* Johannes Hevelius

Johannes Hevelius

Some sources refer to Hevelius as Polish:

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

Some sources refer to Hevelius as German:

*

*

*

*

*of the Royal Society

* (in German also known as ''Hevel''; ; – 28 January 1687) was a councillor and mayor of Danz ...

, ''Selenographia

''Selenographia, sive Lunae descriptio'' (''Selenography, or A Description of The Moon'') was printed in 1647 and is a milestone work by Johannes Hevelius. It includes the first detailed map of the Moon, created from Hevelius's personal observati ...

'', 1647.

* Giovanni Battista Riccioli

Giovanni Battista Riccioli (17 April 1598 – 25 June 1671) was an Italian astronomer and a Catholic priest in the Jesuit order. He is known, among other things, for his experiments with pendulums and with falling bodies, for his discussion of ...

and Francesco Maria Grimaldi

Francesco Maria Grimaldi (2 April 1618 – 28 December 1663) was an Italian Jesuit priest, mathematician and physicist who taught at the Jesuit college in Bologna. He was born in Bologna to Paride Grimaldi and Anna Cattani.

Work

Between 164 ...

, '' Almagestum novum'', 1651.

* Giovanni Domenico Cassini

Giovanni Domenico Cassini (8 June 1625 – 14 September 1712) was an Italian-French mathematician, astronomer, astrologer and engineer. Cassini was born in Perinaldo, near Imperia, at that time in the County of Nice, part of the Savoyard sta ...

, engraved map, 1679 (reprinted in 1787).

* Tobias Mayer, engraved map, 1749, published in 1775.

* Johann Hieronymus Schröter

Johann Hieronymus Schröter (30 August 1745, Erfurt – 29 August 1816, Lilienthal) was a German astronomer.

Life

Schröter was born in Erfurt, and studied law at Göttingen University from 1762 until 1767, after which he started a ten- ...

, ''Selenotopografisches Fragmenten'', 1st volume 1791, 2nd volume 1802.

* John Russell, engraved images, 1805.

* Wilhelm Lohrmann, ''Topographie der sichtbaren Mondoberflaeche'', Leipzig, 1824.

* Wilhelm Beer

Wilhelm Wolff Beer (4 January 1797 – 27 March 1850) was a banker and astronomer from Berlin, Prussia, and the brother of Giacomo Meyerbeer.

Astronomy

Beer's fame derives from his hobby, astronomy. He built a private observatory with a ...

and Johann Heinrich Mädler

Johann, typically a male given name, is the German form of ''Iohannes'', which is the Latin form of the Greek name ''Iōánnēs'' (), itself derived from Hebrew name '' Yochanan'' () in turn from its extended form (), meaning "Yahweh is Gracious ...

, ''Mappa Selenographica totam Lunae hemisphaeram visibilem complectens'', Berlin, 1834-36.

* Edmund Neison, ''The Moon'', London, 1876.

* Julius Schmidt, ''Charte der Gebirge des Mondes'', Berlin, 1878.

* Thomas Gwyn Elger, ''The Moon'', London, 1895.

* Johann Krieger, ''Mond-Atlas'', 1898. Two additional volumes were published posthumously in 1912 by the Vienna Academy of Sciences.

* Walter Goodacre, ''Map of the Moon'', London, 1910.

* Mary A. Blagg and Karl Müller, ''Named Lunar Formations'', 2 volumes, London, 1935.

* Philipp Fauth, ''Unser Mond'', Bremen, 1936.

* Hugh P. Wilkins, ''300-inch Moon map'', 1951.

* Gerard Kuiper

Gerard Peter Kuiper ( ; born Gerrit Pieter Kuiper, ; 7 December 1905 – 23 December 1973) was a Dutch-American astronomer, planetary scientist, selenographer, author and professor. The Kuiper belt is named after him.

Kuiper is consi ...

''et al.'', ''Photographic Lunar Atlas'', Chicago, 1960.

* Ewen A. Whitaker

Ewen Adair Whitaker (22 June 1922 – 11 October 2016) was a British-born astronomer known for his work in selenography and lunar cartography. Together with Gerard Kuiper, Whitaker founded the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory at the University of Ar ...

''et al.'', ''Rectified Lunar Atlas'', Tucson, 1963.

* Hermann Fauth and Philipp Fauth (posthumously), ''Mondatlas'', 1964.

* Gerard Kuiper

Gerard Peter Kuiper ( ; born Gerrit Pieter Kuiper, ; 7 December 1905 – 23 December 1973) was a Dutch-American astronomer, planetary scientist, selenographer, author and professor. The Kuiper belt is named after him.

Kuiper is consi ...

''et al.'', ''System of Lunar Craters'', 1966.

* Yu I. Efremov ''et al.'', ''Atlas Obratnoi Storony Luny'', Moscow, 1967–1975.

* NASA

The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA ) is an independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the federal government of the United States, US federal government responsible for the United States ...

, ''Lunar Topographic Orthophotomaps'', 1978.

* Antonín Rükl

Antonín Rükl (22 September 1932 – 12 July 2016) was a Czech astronomer, cartographer, and author.

He was born in Čáslav, Czechoslovakia. As a student, he developed what was to be a lifelong interest in astronomy. He graduated from the Cz ...

, ''Atlas of the Moon'', 2004.

Galleries

See also

*Gravitation of the Moon

300px, Radial gravity anomaly at the surface of the Moon in mGal

The acceleration due to gravity on the surface of the Moon is approximately 1.625 m/s2, about 16.6% that on Earth's surface or 0.166 . Over the entire surface, the variatio ...

* Google Moon

*Grazing lunar occultation __NOTOC__

A grazing lunar occultation (also lunar grazing occultation, lunar graze, or just graze) is a lunar occultation in which as the occulted star disappears and reappears intermittently on the edge of the Moon.

A team of many observers can ...

*Planetary nomenclature

Planetary nomenclature, like terrestrial nomenclature, is a system of uniquely identifying features on the surface of a planet or natural satellite so that the features can be easily located, described, and discussed. Since the invention of the ...

* Selenographic coordinate system

* List of maria on the Moon

*List of craters on the Moon

This is a list of named lunar craters. The large majority of these features are impact craters. The Planetary nomenclature, crater nomenclature is governed by the International Astronomical Union, and this listing only includes features that are ...

*List of mountains on the Moon

This is a list of mountains on the Moon (with a scope including all named ''mons'' and ''montes'', planetary science jargon terms roughly equivalent to 'isolated mountain'/'massif' and 'mountain range').

Caveats

* This list is not comprehensiv ...

* List of valleys on the Moon

References

Citations

Bibliography

* * *External links

NASA Catalogue of Lunar Nomenclature

(1982), Leif E. Andersson and Ewen A. Whitaker

, Kevin S. Jung

Consolidated Lunar Atlas

Virtual exhibition about the topography of the Moon

on the digital library of

Paris Observatory

The Paris Observatory (, ), a research institution of the Paris Sciences et Lettres University, is the foremost astronomical observatory of France, and one of the largest astronomical centres in the world. Its historic building is on the Left Ban ...

{{Authority control

Topography

Geodesy

Lunar science

Cartography