Louisiana VooDoo on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Louisiana Voodoo, also known as New Orleans Voodoo, was an African diasporic religion that existed in

Louisiana Voodoo was a religion, and more specifically an "African diasporic religion", an African American religion, and a creole religion.

Louisiana Voodoo has also been referred to as New Orleans Voodoo, and—in some older texts—Voodooism. The scholar Ina J. Fandrich described it as the "Afro-Creole counterculture religion of southern Louisiana".

Louisiana Voodoo emerged along the

Louisiana Voodoo was a religion, and more specifically an "African diasporic religion", an African American religion, and a creole religion.

Louisiana Voodoo has also been referred to as New Orleans Voodoo, and—in some older texts—Voodooism. The scholar Ina J. Fandrich described it as the "Afro-Creole counterculture religion of southern Louisiana".

Louisiana Voodoo emerged along the

The civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s marked a new period in which the New Orleans tourist industry increasingly recognized African American culture as an integral aspect of the city's heritage. From the 1960s onward, the city's tourist industry increasingly referenced Louisiana Voodoo as a means of attracting visitors. In 1972, Charles Gandolfo established the tourist-oriented New Orleans Historic Voodoo Museum. In New Orleans' French Quarter, as well as through mail-order catalogs and later the Internet, salespeople began selling paraphernalia that they claimed was associated with Voodoo.

Several companies also began providing walking tours of the city pointing out locations alleged to have a prominent role in the history of Voodoo, and in some cases staging Voodoo rituals for paying onlookers. One company, Voodoo Authentica, began organizing an annual Voodoofest in Congo Square each

The civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s marked a new period in which the New Orleans tourist industry increasingly recognized African American culture as an integral aspect of the city's heritage. From the 1960s onward, the city's tourist industry increasingly referenced Louisiana Voodoo as a means of attracting visitors. In 1972, Charles Gandolfo established the tourist-oriented New Orleans Historic Voodoo Museum. In New Orleans' French Quarter, as well as through mail-order catalogs and later the Internet, salespeople began selling paraphernalia that they claimed was associated with Voodoo.

Several companies also began providing walking tours of the city pointing out locations alleged to have a prominent role in the history of Voodoo, and in some cases staging Voodoo rituals for paying onlookers. One company, Voodoo Authentica, began organizing an annual Voodoofest in Congo Square each

This revival was established through the efforts of several different groups. In 1990, the African American Miriam Chamani established the Voodoo Spiritual Temple in the French Quarter, which venerated deities from Haitian Vodou and Cuban Santería. A Ukrainian-Jewish American initiate of Haitian Vodou, Sallie Ann Glassman, launched another group, La Source Ancienne, in the Bywater neighborhood; she also operated the Island of Salvation Botanica store. The most publicly prominent of the new Voodoo practitioners was Ava Kay Jones, a Louisiana Creole woman who had been initiated into both Haitian Vodou and Orisha-Vodu, a U.S.-based derivative of Santería.

These groups sought to promote understanding of their religion through websites, newsletters, and workshops. Long noted that the "Voodoo revival" of the late 20th century had attracted many "well-educated" and middle-class Americans, both black and white. Glassman's group has been described as having a white-majority membership.

This revival was established through the efforts of several different groups. In 1990, the African American Miriam Chamani established the Voodoo Spiritual Temple in the French Quarter, which venerated deities from Haitian Vodou and Cuban Santería. A Ukrainian-Jewish American initiate of Haitian Vodou, Sallie Ann Glassman, launched another group, La Source Ancienne, in the Bywater neighborhood; she also operated the Island of Salvation Botanica store. The most publicly prominent of the new Voodoo practitioners was Ava Kay Jones, a Louisiana Creole woman who had been initiated into both Haitian Vodou and Orisha-Vodu, a U.S.-based derivative of Santería.

These groups sought to promote understanding of their religion through websites, newsletters, and workshops. Long noted that the "Voodoo revival" of the late 20th century had attracted many "well-educated" and middle-class Americans, both black and white. Glassman's group has been described as having a white-majority membership.

New Orleans Historic Voodoo Museum

{{Afro-American Religions Afro-American religion Christianity and religious syncretism Louisiana culture

Louisiana

Louisiana ( ; ; ) is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It borders Texas to the west, Arkansas to the north, and Mississippi to the east. Of the 50 U.S. states, it ranks 31st in area and 25 ...

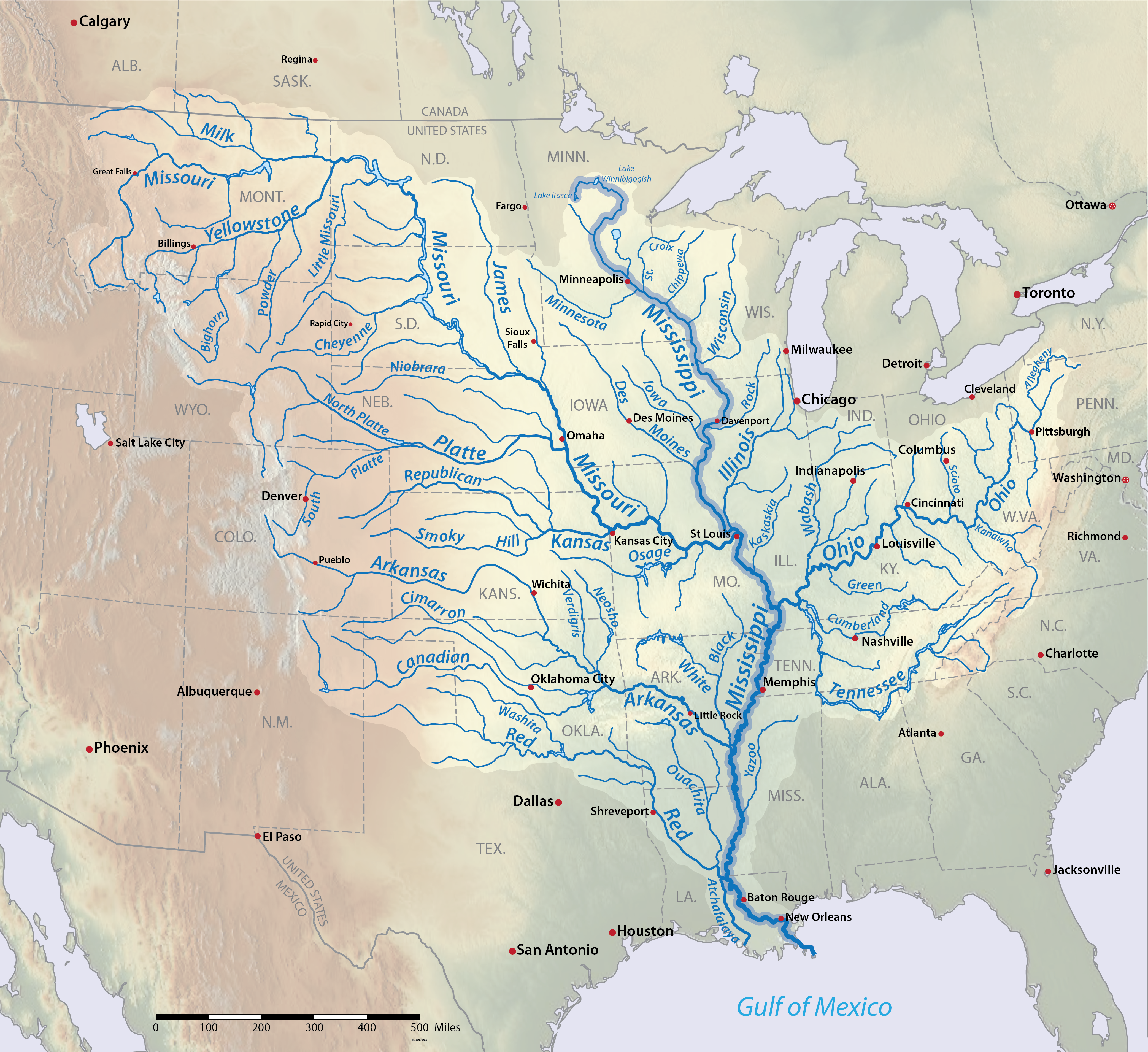

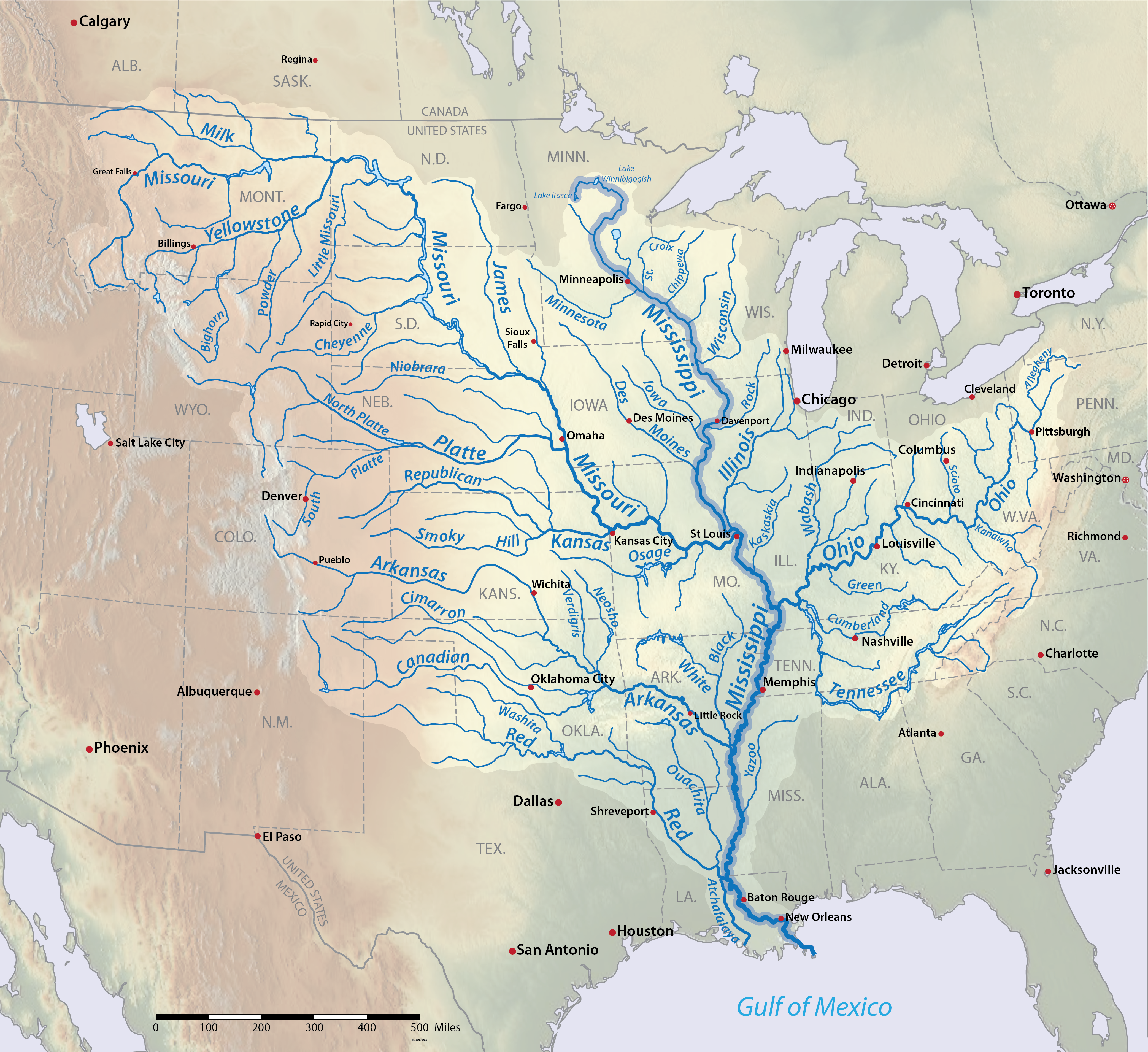

and the broader Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the main stem, primary river of the largest drainage basin in the United States. It is the second-longest river in the United States, behind only the Missouri River, Missouri. From its traditional source of Lake Ita ...

valley between the 18th and early 20th centuries. It arose through a process of syncretism

Syncretism () is the practice of combining different beliefs and various school of thought, schools of thought. Syncretism involves the merging or religious assimilation, assimilation of several originally discrete traditions, especially in the ...

between the traditional religions of West

West is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from east and is the direction in which the Sun sets on the Earth.

Etymology

The word "west" is a Germanic word passed into some Romance langu ...

and Central Africa

Central Africa (French language, French: ''Afrique centrale''; Spanish language, Spanish: ''África central''; Portuguese language, Portuguese: ''África Central'') is a subregion of the African continent comprising various countries accordin ...

, and Haitian Vodou

Haitian Vodou () is an African diasporic religions, African diasporic religion that developed in Haiti between the 16th and 19th centuries. It arose through a process of syncretism between several traditional religions of West Africa, West and ...

. No central authority controlled Louisiana Voodoo, which was organized through autonomous groups.

From the early 18th century, enslaved West and Central Africans—the majority of them Bambara and Bakongo

The Kongo people (also , singular: or ''M'kongo; , , singular: '') are a Bantu ethnic group primarily defined as the speakers of Kikongo. Subgroups include the Beembe, Bwende, Vili, Sundi, Yombe, Dondo, Lari, and others.

They have li ...

—were brought to the French colony of Louisiana. There, their traditional religions syncretized with each other and with the Catholic beliefs of the French. This continued as Louisiana came under Spanish control and was then purchased by the United States in 1803. In the early 19th century, many migrants fleeing the Haitian Revolution

The Haitian Revolution ( or ; ) was a successful insurrection by slave revolt, self-liberated slaves against French colonial rule in Saint-Domingue, now the sovereign state of Haiti. The revolution was the only known Slave rebellion, slave up ...

arrived in Louisiana, bringing with them Haitian Vodou, which contributed to the formation of Louisiana Voodoo. Practiced primarily by black people, but with some white involvement, Voodoo spread up the Mississippi River to Missouri

Missouri (''see #Etymology and pronunciation, pronunciation'') is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it border ...

. Although the religion was never banned, its practice was restricted through laws regulating when and where black people could gather. Growing government opposition in the mid-19th century brought multiple arrests and prosecutions, while increased press attention directed greater attention to prominent Voodoo practitioners like Marie Laveau. Voodoo died out in the early 20th century, although some of its practices survived through hoodoo.

Information about Voodoo's beliefs and practices comes from various historical records, but this material is partial and much about the religion is not known. Historical records reveal the names of various deities who were worshiped in Voodoo. Prominent among them were Blanc Dani, the Grand Zombi, and Papa Lébat, whose identities derived from various African divinities. These were venerated at altars and offered animal sacrifice

Animal sacrifice is the ritual killing and offering of animals, usually as part of a religious ritual or to appease or maintain favour with a deity. Animal sacrifices were common throughout Europe and the Ancient Near East until the spread of Chris ...

s; several sources refer to the involvement of live snakes in rituals. Spirits of the dead and Catholic saints

In Christian belief, a saint is a person who is recognized as having an exceptional degree of holiness, likeness, or closeness to God. However, the use of the term ''saint'' depends on the context and denomination. In Anglican, Oriental Orth ...

also played a prominent role. Each Voodoo group was independent and typically led by a priestess or less commonly a priest. Membership of these groups was provided through an initiation ceremony. Major celebrations occurred at Saint John's Eve

Saint John's Eve, starting at sunset on 23 June, is the eve of the Nativity of St John the Baptist, feast day of Saint John the Baptist. This is one of the very few feast days marking a saint's birth, rather than their death. The Gospel of Luke ...

(23 or 24 June), which in the 19th century was marked by large gatherings on the shores of Lake Pontchartrain. Also playing an important part of Voodoo practice was the production of material charms, often known as '' gris-gris'', for purposes such as healing and cursing.

Louisiana Voodoo has long faced opposition from non-practitioners, who have characterized it as witchcraft

Witchcraft is the use of Magic (supernatural), magic by a person called a witch. Traditionally, "witchcraft" means the use of magic to inflict supernatural harm or misfortune on others, and this remains the most common and widespread meanin ...

and devil-worship, negative attitudes that have resulted in many sensationalist portrayals of the religion in popular culture. From the 1960s, the New Orleans

New Orleans (commonly known as NOLA or The Big Easy among other nicknames) is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city-parish located along the Mississippi River in the U.S. state of Louisiana. With a population of 383,997 at the 2020 ...

tourist industry increasingly used references to Voodoo to attract visitors, while the 1990s saw the start of a Voodoo revival, the practitioners of which drew heavily on other African diasporic religions such as Haitian Vodou and Cuban Santería

Santería (), also known as Regla de Ocha, Regla Lucumí, or Lucumí, is an African diaspora religions, Afro-Caribbean religion that developed in Cuba during the late 19th century. It arose amid a process of syncretism between the traditional ...

.

Definitions

Louisiana Voodoo was a religion, and more specifically an "African diasporic religion", an African American religion, and a creole religion.

Louisiana Voodoo has also been referred to as New Orleans Voodoo, and—in some older texts—Voodooism. The scholar Ina J. Fandrich described it as the "Afro-Creole counterculture religion of southern Louisiana".

Louisiana Voodoo emerged along the

Louisiana Voodoo was a religion, and more specifically an "African diasporic religion", an African American religion, and a creole religion.

Louisiana Voodoo has also been referred to as New Orleans Voodoo, and—in some older texts—Voodooism. The scholar Ina J. Fandrich described it as the "Afro-Creole counterculture religion of southern Louisiana".

Louisiana Voodoo emerged along the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the main stem, primary river of the largest drainage basin in the United States. It is the second-longest river in the United States, behind only the Missouri River, Missouri. From its traditional source of Lake Ita ...

valley, and especially in the city of New Orleans, during the 18th and early 19th centuries before dying out in the early 20th century. It was informed heavily by the traditional African religions brought to the region, predominantly from West Central Africa and Senegambia

The Senegambia (other names: Senegambia region or Senegambian zone,Barry, Boubacar, ''Senegambia and the Atlantic Slave Trade'', (Editors: David Anderson, Carolyn Brown; trans. Ayi Kwei Armah; contributors: David Anderson, American Council of Le ...

, but also took influence from the Native Americans of the Mississippi River Valley, French and Spanish settlers, Anglo-Americans, and Haitian migrants bringing with them Haitian Vodou

Haitian Vodou () is an African diasporic religions, African diasporic religion that developed in Haiti between the 16th and 19th centuries. It arose through a process of syncretism between several traditional religions of West Africa, West and ...

.

The historical record for Voodoo is fragmentary, with much information about the religion being lost and not recoverable. It was a largely oral tradition, with its followers often being illiterate or uninterested in committing information about their practices to writing. It had no formal creed, nor a specific sacred text, and had no unifying organized structure or hierarchy. Practitioners often adapted Voodoo to suit their specific requirements, in doing so often mixing it with other religious traditions. Throughout its history, many Voodoo practitioners also practiced Catholicism and integrated Catholic elements into their practice of Voodoo. In turn, the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

largely ignored Voodoo throughout much of the 18th and early 19th centuries. The prominent 19th-century Voodoo priestess Marie Laveau for instance regularly attended Mass

Mass is an Intrinsic and extrinsic properties, intrinsic property of a physical body, body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the physical quantity, quantity of matter in a body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physi ...

at a Catholic church, and was close friends with the Catholic Friar

A friar is a member of one of the mendicant orders in the Catholic Church. There are also friars outside of the Catholic Church, such as within the Anglican Communion. The term, first used in the 12th or 13th century, distinguishes the mendi ...

Antonio de Sedella, who worked with her in ministering to the sick.

Etymology and terminology

The term ''Voodoo'' derives ultimately from ''vodu'', a term meaning "spirit" or "deity" among the Fon and Ewe languages of West Africa. Although the spelling ''Voodoo'' is now the most popular way of referring to the Louisiana religion, variant spellings have been used over the years, including ''Voudou'' and ''Vaudou''. In modern scholarship, the spelling ''Voodoo'' is sometimes used for the Louisiana practice to distinguish it from Haitian Vodou. When the religion was active, its practitioners often referred to themselves as ''Voodoos'', although elsewhere they have been called ''Voodooists''. A related term is '' hoodoo'', which may originally have been largely synonymous with ''Voodoo''. The historian Jeffrey Anderson noted that the distinction between the two terms is "blurry" and "depends heavily on who explains them". Some Voodoo practitioners evidently called what they did ''hoodoo''; in 1940, one practitioner was recorded as saying that "Voodoo means the worker, hoodoo the things they do". The historian Katrina Hazzard-Donald noted that in parts of Louisiana, hoodoo and Voodoo would have been "viewed as indistinguishable in many respects by outsiders and believers alike." Attempting to clarify things, by the 21st century there was a general scholarly consensus that the terms ''Voodoo'' and ''hoodoo'' should be used to describe two distinct phenomena. Thus, the term ''hoodoo'' has come to describe "the brand of African American supernaturalism found along the Mississippi", meaning the use of charms and spells, often to heal or to harm, that need not make any reference to deities. In this, hoodoo differs from the specific religion, with its priesthood and organised deity worship, that is characterized by the term ''Voodoo''.Beliefs

Deities

Although it displayed its own spiritual hierarchy, Louisiana Voodoo had no formal theology. Many practitioners of Voodoo did not see their religion as being in intrinsic conflict with the Catholicism that was dominant along the Mississippi River, and thus practiced both religions. Despite this, there was no clear evidence of the Christian God being incorporated into the Voodoo pantheon. Anderson suggested that Voodooists may have seen the worship of God as something that was best done in a Christian church. The names of Louisiana Voodoo's deities were recorded in various 19th-century sources. These deities seem to derive predominantly from spirits venerated around the Bight of Benin. In contrast to Haitian Vodou, there is no evidence that these were divided into groups known as ''nanchon'' (nations). One of the most important deities was Blanc Dani, also known as Daniel Blanc or Monsieur Danny. The earliest records of him date from 1880, and it is probable that he derives from Dan or Da, a deity venerated by the Fon and Ewe people and whose worship centred largely around Ouidah (in modern Benin). In West Africa, Dan is associated with the color white and this may explain suggestions from the Louisiana material that Blanc Dani was perceived as a white man. Although there are no specific references to Blanc Dani being a serpent, the prominence of snakes within Louisiana Voodoo might have been an allusion to Blanc Dani, for Dan is often associated with snakes in both West Africa and in his Haitian form, Damballa. Another recorded name, Dambarra Soutons, may be an additional name for Blanc Dani. A similar figure, Grandfather Rattlesnake, appeared in the 19th-century folklore of African-American Missourians and may also be a development of the same West African character. It is also possible that Blanc Dani was ultimately equated with another deity, known as the Grand Zombi, whose name meant "Great God" or "Great Spirit;" the term ''Zombi'' derives from the Kongo Bantu term ''nzambi'' (god). Another prominent deity was Papa Lébat, also called Liba, LaBas, or Laba Limba, and he was seen as a trickster as well as a doorkeeper; his name stems from the Yoruba deity Legba, with Fandrich suggesting that he was the only one of these New Orleans deities with an unequivocally Yoruba origin. Monsieur Assonquer, also known as Onzancaire and On Sa Tier, was associated with good fortune in Louisiana Voodoo. His name may suggest an origin in the Yoruba figure Osanyin. Another Louisiana character, Monsieur Agoussou or Vert Agoussou, was associated with love. Vériquité was a spirit associated with the causing of illness, while Monsieur d'Embarass was linked to death. Charlo was a child deity. The names of several other deities are recorded, but with little known about their associations, including Jean Macouloumba, who was also known as Colomba; Maman You; and Yon Sue. There was also a deity called Samunga, called upon by practitioners in Missouri when they were collecting mud.Ancestors and saints

The spirits of the dead played a prominent role in Louisiana Voodoo during the 19th century. The prominence of these spirits of the dead may owe something to the fact that New Orleans' African American population was heavily descended from enslaved Bakongo people, whose traditional religion placed strong emphasis on such entities. The importance of the dead is also suggested by the significance that was accorded to graveyard soil by Voodoo practitioners, something that also bears parallels in the religions of West Central Africa. In Louisiana, the term ''zombi''—probably derived from the Kikongo term ''nzambi''—was historically often used to describe a ghost or spirit, or sometimes also a wizard or ritual specialist. As Africans arrived in Louisiana, they adopted from Catholicism and so various West African deities became associated with specific Catholic saints. Papa Lébat was for instance linked toSaint Peter

Saint Peter (born Shimon Bar Yonah; 1 BC – AD 64/68), also known as Peter the Apostle, Simon Peter, Simeon, Simon, or Cephas, was one of the Twelve Apostles of Jesus and one of the first leaders of the Jewish Christian#Jerusalem ekklēsia, e ...

, and Mama You to the Virgin Mary

Mary was a first-century Jewish woman of Nazareth, the wife of Saint Joseph, Joseph and the mother of Jesus. She is an important figure of Christianity, venerated under titles of Mary, mother of Jesus, various titles such as Perpetual virginity ...

. These linkages were largely forged by similarities between the corresponding figures; Papa Lébat was for instance seen to open the way for practitioners, while Saint Peter is traditionally portrayed holding keys. Interviews with elderly New Orleanians conducted in the 1930s and 1940s suggested that, as it existed in the closing three decades of the 19th century, Voodoo primarily entailed supplications to the saints for assistance. Among the most popular was Saint Anthony of Padua

Anthony of Padua, OFM, (; ; ) or Anthony of Lisbon (; ; ; born Fernando Martins de Bulhões; 15 August 1195 – 13 June 1231) was a Portuguese Catholic priest and member of the Order of Friars Minor.

Anthony was born and raised by a wealth ...

; this figure is also the patron saint of the Bakongo, a likely link to the heavily Bakongo-descended population of New Orleans. These correspondences between Catholic saints and African-derived deities are similarly evident in many other African diasporic religions.

Morality, ethics, and gender roles

Various commentators have described Louisiana Voodoo as matriarchal because of the dominant role priestesses have played in it. The feminist theorist Tara Green defined the term "Voodoo Feminism" to describe instances whereby African American women drew upon both Louisiana Voodoo and conjure to resist racial and gender oppression that they experienced. Fandrich suggested that Voodoo offered women the opportunity to venerate female deities and witness role models for female leadership that were not offered by other religions in Louisiana at the time. Michelle Gordon believed that the fact that free women of color dominated Voodoo in the 19th century represented a direct threat to the ideological foundations of "white supremacy

White supremacy is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White supremacy has roots in the now-discredited doctrine ...

and patriarchy."

Practices

Present knowledge of Voodoo ceremonies is limited. There are no surviving systematic or detailed accounts of small-scale rituals, and the better recorded accounts of Voodoo ceremonies are restricted primarily to New Orleans rather than other areas of the Mississippi River Valley. From these accounts, it is apparent that rituals often took place in private homes, sometimes in a room set aside for ceremonial purposes. In other cases they occurred outdoors, as in Congo Square or Saint John's Bayou. There are four phases to a Voodoo ritual, all identifiable by the song being sung: preparation, invocation, possession, and farewell. The songs are used to open the gate between the deities and the human world and invite the spirits to possess someone.Initiation and leadership

Voodoo was an initiatory religion and various accounts of initiation ceremonies survive, with the emphasis on initiation showing strong similarities with practices from Sub-Saharan Africa. Fees would often be charged for initiation, something that is common among African traditional religions and African diasporic traditions. Given that various extant African diasporic religions feature multiple degrees or progressive initiations through which a person can pass, Anderson suggested that a similar process might have been evident in Louisiana Voodoo. One Voodoo specialist, King Alexander, for instance reported that there were four degrees in the religion. For Voodoo's leaders, the tradition provided both a religion and a career. There are various references to these leaders charging people to attend their rituals. Some Voodoo leaders were able to achieve significant economic success through their activities; Marie Laveux for instance was wealthy enough to become a slave-owner. Leaders seemed to have worn distinctive clothing during ritual.Altars and offerings

When practitioners had a room set-aside for their ceremonies, it sometimes contained an altar which Ould include bowls of stones and prints of Roman Catholic saints. Historical records describe the altars created by famous 19th-century Voodoo priestess Marie Laveau in her home; Long noted that these descriptions resemble those of altars used in Haitian Vodou. On being arrested, reports were also made describing the altar of the 19th-century Voodoo priestess Betsey Toledo, indicating that it was decorated with pictures of Catholic saints and apostles. Sacrifice was a recurring element of Louisiana Voodoo as it was historically practiced, as it continues to be in Haitian Vodou. Although there is little proof that human sacrifice took place in Louisiana Voodoo, persistent rumors claimed that white children were being abducted and killed during some of its rites. Plates of food may be left out, encircled in a ring of coins. Candles also featured in Louisiana Voodoo rituals, potentially through the influence of Catholicism and Haitian Vodou. Their prominent use in Voodoo contrasted with the apparent absence of candles in "the old black belt Hoodoo tradition" elsewhere in North America. Laveau used to hold weekly services, which were called ''parterres''. Many historical Voodoo rituals involved the presence of a snake; Marie Laveau was for instance described as communing with a snake during her ceremonies. Fandrich described the use of a living snake, probably representing the Gran Zombi, as "the trademark of New Orleanian Voodoo".Gris-Gris and healing

Charms, created to either harm or help, were called ''gris-gris''. This term derives from West Africa, where related words are widespread among many ethnic and linguistic groups, but in North America was restricted to the lower Mississippi River Valley and a strip along theGulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico () is an oceanic basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, mostly surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north, and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United States; on the southw ...

near the river's mouth. In the Mississippi River Valley, references to ''gris-gris'' first date from the 1750s.

Another term, ''Zinzin'', sometimes referring to positive charms, derives from the Bamana language. Another term, ''Wanga'', was more commonly used for harmful charms in Voodoo and probably derives from West Central Africa, where the terms ''oganga'' and ''nganga'' were used for priests in Kikongo.

Some ''gris-gris'' comprised animal body parts; a ''gris-gris'' created in 1773, and which was reportedly intended to kill someone, was made from the gall and heart of an alligator.

A common charm for protection or luck would consist of material wrapped up in red flannel and worn around the neck.

Brick dust was also a distinctive feature in the ritual practices of the lower Mississippi River Valley. There are early 20th-century accounts of brick dust being used for washing floors of a business to increase custom, or to scrub a doorstep to protect the household from curses. The brick dust used was red, a color which in much of Africa is associated with the spirit world.

Touchstone believed that gris-gris that caused actual harm did so either through the power of suggestion or by the fact that they contained poisons to which the victim was exposed.

One example of a Voodoo curse was to place an object inside the pillow of the victim. Another involves placing a coffin (sometimes a small model; sometimes much larger) inscribed with the victim's name on their doorstep. In other instances, Voodoo practitioners sought to hex others by placing black crosses, salt, or mixtures incorporating mustard, lizards, bones, oil, and grave dust on a victim's doorstep. To counter these hexes, some people cleaned their doorstep or sprinkled it with powdered brick.

The practice of making and wearing charms and amulets for protection, healing, or the harm of others was a key aspect to early Louisiana Voodoo. The ''Ouanga'', a charm used to poison an enemy, contained the toxic roots of the ''figuier maudit'' tree, brought from Africa and preserved in Louisiana. The ground-up root was combined with other elements, such as bones, nails, roots, holy water, holy candles, holy incense, holy bread, or crucifixes. The administrator of the ritual frequently evoked protection from Jehovah

Jehovah () is a Romanization, Latinization of the Hebrew language, Hebrew , one Tiberian vocalization, vocalization of the Tetragrammaton (YHWH), the proper name of the God in Judaism, God of Israel in the Hebrew BibleOld Testament. The Tetr ...

and Jesus Christ

Jesus (AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ, Jesus of Nazareth, and many Names and titles of Jesus in the New Testament, other names and titles, was a 1st-century Jewish preacher and religious leader. He is the Jesus in Chris ...

. This openness of African belief allowed for the adoption of Catholic practices into Louisiana Voodoo.

Despite its name, the idea of the Voodoo doll

A voodoo doll is an effigy that is typically used for the insertion of pins. Such practices are found in various forms in the magic (paranormal), magical traditions of many cultures around the world.

Despite its name, the voodoo doll is not prom ...

has little to do with either Louisiana Voodoo or Haitian Vodou; it derives from the European tradition of poppets. It is possible that the act of inserting pins into a human-shaped doll to cause harm was erroneously linked to African-derived traditions due to a misunderstanding of the '' nkisi nkondi'' of Bakongo religion.

Communal festivals

Communal festivals were also part of Mississippi River Voodoo, with two dates appearing to have been important: All Saints Day (1 November) andSaint John's Eve

Saint John's Eve, starting at sunset on 23 June, is the eve of the Nativity of St John the Baptist, feast day of Saint John the Baptist. This is one of the very few feast days marking a saint's birth, rather than their death. The Gospel of Luke ...

(23 or 24 June). Of these, we know less about how Voodoo practitioners marked All Saints Day. By the late 19th century, large celebrations marking Saint John's Eve were being held on the shores of Lake Pontchartrain, having become a festival marked by feasting and associated with water.

The purpose of the Saint John's Eve ritual is unclear, but to some extent it may have been a celebration of spring. Its focus on the lake as a location may be related to rituals focusing around water than can be found in both West Africa and Haiti.

History

French and Spanish Louisiana

Much mystery surrounds the origins of Louisiana Voodoo, with its history often being embellished with legend. French settlers arrived in Louisiana in the 1660s, and in 1682 France claimed all lands drained by the Mississippi River and its tributaries. In 1719, the first enslaved Africans were brought to the colony, a group of around 450 people from the port at Ouidah. The religions of the West African slaves combined with elements of the folk Catholicism practiced by the dominant French and Spanish colonists to provide the origins of Louisiana Voodoo. Records of African traditional religious practices being practiced in Louisiana go back to the 1730s, when Antoine-Simon Le Page du Pratz wrote about the use of ''gris-gris''. In 1763 the Spanish Empire took control and remained in power until 1803. Under Spanish rule, Louisiana's economy grew and increasing numbers of enslaved Africans were imported to work on the plantations. The Spanish period also saw the emergence of a class of free people of color, from whom much of Voodoo's leadership would derive. No one African ethnic group contributed the bulk of beliefs for what became Voodoo. Many of the earliest slaves came from theBight of Benin

The Bight of Benin, or Bay of Benin, is a bight in the Gulf of Guinea area on the western African coast that derives its name from the historical Kingdom of Benin.

Geography

The Bight of Benin was named after the Kingdom of Benin. It extends ea ...

and were often Ewe, Fon, and Yoruba, whose traditional religions would prove important influences over Louisiana Voodoo. By the second half of the 1720s Africans imported from Ouidah were being outnumbered by those from Senegambia

The Senegambia (other names: Senegambia region or Senegambian zone,Barry, Boubacar, ''Senegambia and the Atlantic Slave Trade'', (Editors: David Anderson, Carolyn Brown; trans. Ayi Kwei Armah; contributors: David Anderson, American Council of Le ...

; these included members of the Bambara, Mandinka, Wolof, and Fula peoples, who practiced a mix of traditional religions and Islam

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

. After the Spanish took control, increasing numbers of slaves were imported from West-Central Africa, many being Bakongo. The Bakongo traditional religion had already absorbed Christian elements, having been exposed to Catholicism from the late 15th century. Bakongo people became the dominant ethnicity in Louisiana, resulting in what Fandrich called a "Kongolization of New Orleans's African American community".

In the Mississippi River Valley, Native American groups like the Natchez, Caddo

The Caddo people comprise the Caddo Nation of Oklahoma, a federally recognized tribe headquartered in Binger, Oklahoma. They speak the Caddo language.

The Caddo Confederacy was a network of Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands, who ...

, and Choctaw

The Choctaw ( ) people are one of the Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States, originally based in what is now Louisiana, Mississippi and Alabama. The Choctaw language is a Western Muskogean language. Today, Choct ...

remained present throughout the colonial period and into the 19th century, where they operated as trading partners of the Europeans. Close contact between Africans and Native Americans may have helped to preserve African traditional beliefs due to a shared view of the world as being populated by spirits. Certain indigenous plants that were used by the Natives, like sassafras and devil's shoestring, were incorporated into Louisiana's African-derived herbal lore.

The enslaved community quickly outnumbered white European colonists who emigrated there. The French colony was not a stable society when the enslaved sub-Saharan Africans arrived, and the newly arrived sub-Saharan Africans dominated the slave community. According to a census of 1731–1732, the ratio of enslaved sub-Saharan Africans to European settlers was more than two to one. A relatively small number of colonists were planters and slaveholders, owners of sugar plantations with work that required large labor forces. Because the Africans were held in large groups relatively isolated from interaction with whites, their preservation of African indigenous practices and culture was enabled. In northern Louisiana and other European colonies in the American South, enslaved families were usually divided; large numbers of African slaves who were once closely related by family or community were sent to different plantations. However, in southern Louisiana, families, cultures, and languages were kept more intact than in the north. This allowed the cultural traditions, languages, and religious practices of the enslaved to continue there.

Under the French and Spanish colonial governments, Voodoo did not experience strong persecution; there are no records of the Catholic Church waging "anti-superstition campaigns" against the religion in Louisiana. Voodoo was largely tolerated by the authorities throughout the 18th century and there was only one recorded case of Voodoo practitioners being prosecuted during the colonial period. This was the Gris-Gris Case of 1773, in which a group of enslaved men were arrested, accused of making poisonous ''gris-gris'' and plotting to kill their master and plantation owner. In this case, it seems that it was the act of rebellion against the slave-owners, rather than the practice of Voodoo, that principally concerned the authorities.

19th Century

In 1803, the United States took control of Louisiana through theLouisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase () was the acquisition of the Louisiana (New France), territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. This consisted of most of the land in the Mississippi River#Watershed, Mississipp ...

. This resulted in a large influx of Anglo-Americans into the region. These Anglo-Americans often had some familiarity with African-derived traditions, such as the John Canoe festivities on the Atlantic coast and the Pinkster celebrations in New York, but were unaccustomed to a fully developed African-derived religion with its own deities and priests. They thus often regarded Voodoo as an exotic and primitive superstition. The Anglo-American influx also brought new influences to Voodoo as well as increased attention, including a surge in 19th and early 20th-century newspaper coverage.

The start of the 19th centuries also saw the Haitian Revolution

The Haitian Revolution ( or ; ) was a successful insurrection by slave revolt, self-liberated slaves against French colonial rule in Saint-Domingue, now the sovereign state of Haiti. The revolution was the only known Slave rebellion, slave up ...

, whereby African-descended populations in the French Caribbean colony of Saint-Domingue

Saint-Domingue () was a French colonization of the Americas, French colony in the western portion of the Caribbean island of Hispaniola, in the area of modern-day Haiti, from 1659 to 1803. The name derives from the Spanish main city on the isl ...

overthrew the French colonial government and established an independent republic, Haiti. As a result of the upheaval, between 15,000 and 20,000 Francophone migrants from Saint-Domingue arrived in the Mississippi River Valley, including those of African, European, and mixed descent. Many would have been familiar with, or actively involved in, Haitian Vodou and their arrival in continental North America likely reinforced and influenced Louisiana Voodoo. Further influences on the Louisiana religion likely came from Spiritualism

Spiritualism may refer to:

* Spiritual church movement, a group of Spiritualist churches and denominations historically based in the African-American community

* Spiritualism (beliefs), a metaphysical belief that the world is made up of at leas ...

, which had emerged in northeastern parts of the U.S. during the 1840s; the Spiritualist term "séance" would come to be applied to various Voodoo ceremonies.

According to legend, the first meeting place of the Voodoo practitioners in New Orleans was at an abandoned brickyard in Dumaine Street. Those meetings here faced police disruption and so future meetings took place largely in Bayou St. John and along the shores of Lake Pontchartrain. The religion probably appealed to members of the African diaspora, whether enslaved or free, who lacked recourse to retribution for the poor treatment they received through other means. Voodoo probably spread out from Louisiana and into African American communities throughout the Mississippi River Valley, as there are 19th-century references to Voodoo rituals in both St. Louis and St. Joseph in Missouri

Missouri (''see #Etymology and pronunciation, pronunciation'') is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it border ...

; the latter the most northernmost known outpost of the religion. Fandrich suggested that the 1820s and 1830s might have represented the "heyday" of Voodoo, during New Orleans' economic boom.

Growing persecution

Voodoo was never explicitly banned in Louisiana. However, amid establishment fears that Voodoo may be used to foment a slave rebellion, in 1817 the Municipal issued an ordinance preventing slaves from dancing on days other than on Sundays and in locations other than those specifically designated for that purpose. The main location permitted was New Orleans' Congo Square. In the early part of the 19th century, newspapers articles began denouncing the religion. Growing hostility from municipal authorities resulted in various arrests of Voodoo practitioners in the 1850s and 1860s, all of whom were women. These arrests also resulted in much press coverage of the tradition. In April 1850, eight women were arrested and fined for taking part at a Voodoo ceremony in Dauphine Street. In June, 17 women — including the high priestess Betsey Toledano —were arrested for engaging in a Voodoo dance ceremony in Saint Bernard Street, ostensibly because enslaved people, free blacks, and whites were all present together, in contravention of the law. The following month, Toledano and her group were again arrested after a police raid on her Conti Street home. That same month, a group of women were arrested for performing a ceremony near the lake; they subsequently sought to sue the police, claiming disruption of their legal right to religious assembly. By representing themselves in court, these women revealed the they were aware of their legal right to free exercise of religion under theFirst Amendment to the United States Constitution

The First Amendment (Amendment I) to the United States Constitution prevents Federal government of the United States, Congress from making laws respecting an Establishment Clause, establishment of religion; prohibiting the Free Exercise Cla ...

.

During the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

, the Union Army occupied New Orleans and sought to suppress Voodoo. In one instance, the Union authorities broke up a ceremony of free blacks who they accused of trying to use Voodoo powers to aid the Confederacy. In 1863, women were arrested at a Voodoo dance ceremony in Marais Street; a crowd of over 400 women turned up outside the courtroom, and the charges were subsequently dropped. Repression of Voodoo intensified following the Civil War; the 1870s onward saw white writers display an increased concern that Voodoo rituals were facilitating the interaction between black men and white women. That decade saw large gatherings at Lake Pontchartrain on St John's Eve, including many onlookers and reporters; these declined after 1876. In the 1880s and 1890s, the New Orleans authorities again clamped down on Voodoo. Voodoo was used as evidence to bolster the white elite's claim that Africans were inferior to Europeans and thus bolster their belief in the necessity of legalized segregation.

Various practitioners set up shops selling paraphernalia and charms, they also began exploiting the commercial opportunities of the religion by staging ceremonies which charged entry.

Prominent figures

Free women of color dominated the leadership of Voodoo in New Orleans during the 19th century. Among the fifteen "voodoo queens" in neighborhoods scattered around 19th-century New Orleans, Marie Laveau was known as "the Voodoo Queen", the most eminent and powerful of them all. Her religious rite on the shore of Lake Pontchartrain on St. John's Eve in 1874 attracted some 12,000 black and white New Orleanians. Although her help seemed non-discriminatory, she may have favored enslaved servants: Her most "influential, affluent customers...runaway slaves...credited their successful escapes to Laveau's powerful charms".Fandrich, J. Ina. "The Birth of New Orleans' Voodoo Queen: A Long-Held Mystery Resolved. ''Louisiana History:'' The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association, Vol. 46, No. 3 (Summer, 2005) Print. Both her mother and grandmother had practiced Voodoo; she was also baptized a Catholic and attended mass throughout her life. Laveau worked as a hairdresser, but also assisted others with the preparation of herbal remedies and charms. She died in 1881. Her influence continues in the city. In the 21st century, her gravesite in the oldest cemetery is a major tourist attraction; believers of Voodoo offer gifts here and pray to her spirit. Across the street from the cemetery where Laveau is buried, offerings of pound cake are left to the statue of Saint Expedite; these offerings are believed to expedite the favors asked of the Voodoo queen. Saint Expedite represents the spirit standing between life and death. The chapel where the statue stands were once used only for holding funerals. Marie Laveau continues to be a central figure of Louisiana Voodoo and of New Orleans culture. Gamblers shout her name when throwing dice, and multiple tales of sightings of the Voodoo Queen have been told. Another of the most prominent practitioners of the mid-19th century was Jean Montanée or "Dr John", a free black man who sold cures and other material to various clients, amassing sufficient funds to purchase several slaves. He alleged that he was a prince from Senegal who had been taken to Cuba and there freed before coming to Louisiana.Decline and extinction

Anderson argued that Voodoo remained a vibrant religion into the late 19th century, at which it went into decline. The last significant evidence for Voodoo as a living tradition in the Upper Mississippi Valley was from a late 19th-century article by Mary Alicia Owen. By the early 20th century, there were no longer any publicly prominent Voodoo practitioners active in New Orleans, and after the early 1940s there was no more evidence that Voodoo was being actively practiced. According to the historian Carolyn Morrow Long, "Voodoo, as an organized religion, had been thoroughly suppressed by the legal system, public opinion, and Christianity." In the late 1930s and early 1940s, the first serious attempts to document Voodoo's history were made. As part of the government'sWorks Progress Administration

The Works Progress Administration (WPA; from 1935 to 1939, then known as the Work Projects Administration from 1939 to 1943) was an American New Deal agency that employed millions of jobseekers (mostly men who were not formally educated) to car ...

, the Federal Writers' Project

The Federal Writers' Project (FWP) was a federal government project in the United States created to provide jobs for out-of-work writers and to develop a history and overview of the United States, by state, cities and other jurisdictions. It was ...

financed fieldworkers to interview seventy elderly black New Orleanians regarding their experience with Voodoo as it existed between the 1870s and 1890s; many recounted tales of Marie Laveau. This interview material was used as a partial basis for the journalist Robert Tallant's ''Voodoo in New Orleans''; first published in 1946, it engaged in sensationalist coverage although came to be regarded as the pre-eminent work on the subject throughout the century.

As Voodoo as a communal religion devoted to worshiping deities and ancestors declined, a belief in both benevolent and malevolent supernaturalism, coupled with various practices to control and influence events, survived, often being termed '' hoodoo''. In New Orleans, hoodoo displayed greater Catholic influences than similar African American folk practices elsewhere in the southern states. Specialists in hoodoo, known as "doctors" or "workers", often worked out of their homes or shops providing gris-gris, powders, oils, perfume, and incense to clients. Such practices concerned the Anglo-Protestant elite, with regulations being introduced to restrict various healing and fortune-telling practices in the city, resulting in many hoodoo practitioners being convicted, and either fined or imprisoned, in the first half of the 20th century.

Elements of Voodoo were incorporated into the black Spiritual churches whose teachings drew upon Catholicism, Spiritualism

Spiritualism may refer to:

* Spiritual church movement, a group of Spiritualist churches and denominations historically based in the African-American community

* Spiritualism (beliefs), a metaphysical belief that the world is made up of at leas ...

, and Pentecostalism. These Spiritual churches shared some of Voodoo's practices, including an emphasis on healing and on obtaining advice from spirits, and similarly shared a clear Catholic influence. Despite this, Afro-Creole Spiritualists often drew a firm distinction between their practices and Voodoo. Some commentators have argued that Voodoo survived in the form of the Spiritual church movement. Anderson argued against the notion that Voodoo transformed into the Spiritual Churches, stressing the fact that key elements of Voodoo are absent from these organisations.

Demographics

Anderson suggested that had Louisiana Voodoo had involved "a substantial segment of the Mississippi River valley's population". In 1873, the '' Times Picayune'' estimated that there were about 300 dedicated practitioners of Voodoo in New Orleans, with about a thousand looser adherents. Anderson suggested that the majority of both Voodoo practitioners and leaders were women. Most Voodoo priestesses, and a significant proportion of the religion's followers, were free women of color. Anderson thought that the female dominance reflected the fact that women could be priestesses in many African traditional religions, and potentially because in Louisiana, women were disproportionately highly represented among freed persons of color, having been freed from slavery by their white lovers. Fandrich believed that Voodoo had "widespread support" in 19th-century New Orleans, principally among women of color. Fandrich noted that historical accounts suggest that Voodoo groups were "consistently racially integrated", comprising members of various racial groups. The 19th-century police raids that arrested Voodoo practitioners consistently caught up white women, and oral accounts recorded in the 1930s and 1940s suggest that many of Marie Laveau's followers and clients had been white. The 19th-century accounts suggest that white involvement was always a minority in Voodoo.Reception and legacy

Like New Orleans itself, Louisiana Voodoo has long evoked both "fascination and disapproval" from the Anglo-dominated American mainstream. Louisiana Voodoo has gained negative connotations in wider American society, being linked towitchcraft

Witchcraft is the use of Magic (supernatural), magic by a person called a witch. Traditionally, "witchcraft" means the use of magic to inflict supernatural harm or misfortune on others, and this remains the most common and widespread meanin ...

and hexing; Protestant groups, including those present among the black New Orleanian population, have denounced Voodoo as devil worship. During the 19th century, many Anglo-Protestant arrivals to New Orleans also considered Voodoo a threat to public safety and morality; white writers in the late 19th century often expressed concern about the opportunities for miscegenation

Miscegenation ( ) is marriage or admixture between people who are members of different races or ethnicities. It has occurred many times throughout history, in many places. It has occasionally been controversial or illegal. Adjectives describin ...

provided by Voodoo ceremonies, especially the presence of white women near to black men. By the late 20th century, it was gaining increasing recognition as a legitimate religion of the African diaspora.

Tourism

The civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s marked a new period in which the New Orleans tourist industry increasingly recognized African American culture as an integral aspect of the city's heritage. From the 1960s onward, the city's tourist industry increasingly referenced Louisiana Voodoo as a means of attracting visitors. In 1972, Charles Gandolfo established the tourist-oriented New Orleans Historic Voodoo Museum. In New Orleans' French Quarter, as well as through mail-order catalogs and later the Internet, salespeople began selling paraphernalia that they claimed was associated with Voodoo.

Several companies also began providing walking tours of the city pointing out locations alleged to have a prominent role in the history of Voodoo, and in some cases staging Voodoo rituals for paying onlookers. One company, Voodoo Authentica, began organizing an annual Voodoofest in Congo Square each

The civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s marked a new period in which the New Orleans tourist industry increasingly recognized African American culture as an integral aspect of the city's heritage. From the 1960s onward, the city's tourist industry increasingly referenced Louisiana Voodoo as a means of attracting visitors. In 1972, Charles Gandolfo established the tourist-oriented New Orleans Historic Voodoo Museum. In New Orleans' French Quarter, as well as through mail-order catalogs and later the Internet, salespeople began selling paraphernalia that they claimed was associated with Voodoo.

Several companies also began providing walking tours of the city pointing out locations alleged to have a prominent role in the history of Voodoo, and in some cases staging Voodoo rituals for paying onlookers. One company, Voodoo Authentica, began organizing an annual Voodoofest in Congo Square each Halloween

Halloween, or Hallowe'en (less commonly known as Allhalloween, All Hallows' Eve, or All Saints' Eve), is a celebration geography of Halloween, observed in many countries on 31 October, the eve of the Western Christianity, Western Christian f ...

, involving various stalls selling food and paraphernalia and a public Voodoo ceremony.

Revivalist movements

The closing decades of the 20th century saw a resurgence of people claiming to practice Voodoo in New Orleans, a phenomenon reflecting some survivals from earlier practices, some imports from other African diasporic traditions, and some consciously revivalist approaches. Long believed that these groups reflected a "Voodoo revival" rather than a direct continuation of 18th and 19th century traditions; she noted that this new Voodoo typically resembled Haitian Vodou orSantería

Santería (), also known as Regla de Ocha, Regla Lucumí, or Lucumí, is an African diaspora religions, Afro-Caribbean religion that developed in Cuba during the late 19th century. It arose amid a process of syncretism between the traditional ...

more than the 19th-century Louisiana Voodoo. Anderson deemed the link between the historical tradition and the revivalist practices to be "quite tenuous", stating that "today's New Orleans Voodoo" is "an emerging faith inspired by and seeking to reconstruct the older religion".

This revival was established through the efforts of several different groups. In 1990, the African American Miriam Chamani established the Voodoo Spiritual Temple in the French Quarter, which venerated deities from Haitian Vodou and Cuban Santería. A Ukrainian-Jewish American initiate of Haitian Vodou, Sallie Ann Glassman, launched another group, La Source Ancienne, in the Bywater neighborhood; she also operated the Island of Salvation Botanica store. The most publicly prominent of the new Voodoo practitioners was Ava Kay Jones, a Louisiana Creole woman who had been initiated into both Haitian Vodou and Orisha-Vodu, a U.S.-based derivative of Santería.

These groups sought to promote understanding of their religion through websites, newsletters, and workshops. Long noted that the "Voodoo revival" of the late 20th century had attracted many "well-educated" and middle-class Americans, both black and white. Glassman's group has been described as having a white-majority membership.

This revival was established through the efforts of several different groups. In 1990, the African American Miriam Chamani established the Voodoo Spiritual Temple in the French Quarter, which venerated deities from Haitian Vodou and Cuban Santería. A Ukrainian-Jewish American initiate of Haitian Vodou, Sallie Ann Glassman, launched another group, La Source Ancienne, in the Bywater neighborhood; she also operated the Island of Salvation Botanica store. The most publicly prominent of the new Voodoo practitioners was Ava Kay Jones, a Louisiana Creole woman who had been initiated into both Haitian Vodou and Orisha-Vodu, a U.S.-based derivative of Santería.

These groups sought to promote understanding of their religion through websites, newsletters, and workshops. Long noted that the "Voodoo revival" of the late 20th century had attracted many "well-educated" and middle-class Americans, both black and white. Glassman's group has been described as having a white-majority membership.

In popular culture

Sensationalist portrayals of Voodoo have been featured in a range of films and popular novels. The 1987 film '' Angel Heart'' connected Louisiana Voodoo with Satanism; the 2004 film '' The Skeleton Key'' evoked many older stereotypes although made greater reference to the actual practices of Louisiana Voodoo. The 2009Disney

The Walt Disney Company, commonly referred to as simply Disney, is an American multinational mass media and entertainment industry, entertainment conglomerate (company), conglomerate headquartered at the Walt Disney Studios (Burbank), Walt Di ...

film ''The Princess and the Frog

''The Princess and the Frog'' is a 2009 American Animation, animated musical film, musical Romance film, romantic fantasy comedy film produced by Walt Disney Animation Studios and released by Walt Disney Pictures. Inspired in part by the 2002 ...

'', which is set in New Orleans, depicted the character of Mama Odie as a practitioner of Vodou. Characters practicing Louisiana Voodoo were also incorporated into the 2013 U.S. television series '' American Horror Story: Coven'', where they were described as a coven of witches active since the 17th century.

Voodoo has also influenced popular music, as seen in songs like Jimi Hendrix

James Marshall "Jimi" Hendrix (born Johnny Allen Hendrix; November 27, 1942September 18, 1970) was an American singer-songwriter and musician. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest and most influential guitarists of all time. Inducted ...

's " Voodoo Chile" and Colin James' "Voodoo Thing". The New Orleans singer Mac Rebennack took on the stage name of Dr. John after the 19th-century Voodoo practitioner and made heavy use of Voodoo terminology and aesthetics in his music; his first album, released in 1968, was titled '' Gris-Gris''.

References

Notes

Citations

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

New Orleans Historic Voodoo Museum

{{Afro-American Religions Afro-American religion Christianity and religious syncretism Louisiana culture