Louis Botha on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Louis Botha ( , ; 27 September 1862 – 27 August 1919) was a South African politician who was the first

Botha was prominent in efforts to achieve a peace with the British, representing the Boers at the peace negotiations in 1902, and was signatory to the

Botha was prominent in efforts to achieve a peace with the British, representing the Boers at the peace negotiations in 1902, and was signatory to the

Botha, Louis

in

, - , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Botha, Louis 1862 births 1919 deaths Afrikaner people Prime ministers of South Africa Members of the House of Assembly (South Africa) Members of the Dutch Reformed Church in South Africa South African Republic generals South African Republic military personnel of the Second Boer War South African Party (Union of South Africa) politicians World War I political leaders South African military personnel of World War I Deaths from the Spanish flu pandemic Infectious disease deaths in South Africa People from Greytown, KwaZulu-Natal South African people of Dutch descent 1900s in the South African Republic 1900s in Transvaal 1910s in South Africa 20th-century South African people South African members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom South African Freemasons Colony of Natal people Military personnel from KwaZulu-Natal

prime minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

of the Union of South Africa

The Union of South Africa (; , ) was the historical predecessor to the present-day South Africa, Republic of South Africa. It came into existence on 31 May 1910 with the unification of the British Cape Colony, Cape, Colony of Natal, Natal, Tra ...

, the forerunner of the modern South African state. A Boer

Boers ( ; ; ) are the descendants of the proto Afrikaans-speaking Free Burghers of the eastern Cape frontier in Southern Africa during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. From 1652 to 1795, the Dutch East India Company controlled the Dutch ...

war veteran during the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War (, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, Transvaal War, Anglo–Boer War, or South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer republics (the South African Republic and ...

, Botha eventually fought to have South Africa become a British Dominion

A dominion was any of several largely self-governance, self-governing countries of the British Empire, once known collectively as the ''British Commonwealth of Nations''. Progressing from colonies, their degrees of self-governing colony, colon ...

.

Early life

Louis Botha was born in Greytown, Natal one of seven sons and eight daughters born to Louis Botha Senior ( Somerset East,Eastern Cape

The Eastern Cape ( ; ) is one of the nine provinces of South Africa. Its capital is Bhisho, and its largest city is Gqeberha (Port Elizabeth). Due to its climate and nineteenth-century towns, it is a common location for tourists. It is also kno ...

, 26 March 1827 – Harrismith, Orange Free State

The Orange Free State ( ; ) was an independent Boer-ruled sovereign republic under British suzerainty in Southern Africa during the second half of the 19th century, which ceased to exist after it was defeated and surrendered to the British Em ...

, 5 July 1883) and Salomina Adriana van Rooyen (Somerset East, 31 March 1829 – Harrismith, 9 January 1886). Louis Botha briefly attended the school at Hermannsburg

Hermannsburg is a village and a former municipality in the Celle (district), Celle district, in Lower Saxony, Germany. Since 1 January 2015 it is part of the municipality Südheide (municipality), Südheide. It has been a state-recognised resort t ...

before his family relocated to the Orange Free State

The Orange Free State ( ; ) was an independent Boer-ruled sovereign republic under British suzerainty in Southern Africa during the second half of the 19th century, which ceased to exist after it was defeated and surrendered to the British Em ...

. The name Louis runs throughout the family, with every generation since General Louis Botha having the eldest son named Louis. Botha had three brothers who also served as generals in the Second Boer War: an older brother Philip Rudolf (1851–1901), and two younger brothers, Chris

Chris is a short form of various names including Christopher, Christian, Christina, and Christine. Chris is also used as a name in its own right, however it is not as common.

People with the given name

* Chris Abani (born 1966), Nigerian autho ...

(1864–1902), a police officer, and Theunis Jacobus Botha (1867–1930).

Zulu conflict

Louis Botha led " Dinuzulu's Volunteers", a group of Boers that had supported Dinuzulu against Zibhebhu in 1884.Politician

Botha later became a member of the parliament of Transvaal in 1897, representing the district ofVryheid

Vryheid (/Abaqulusi) is a coal mining and cattle ranching town in northern KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Vryheid is the Afrikaans word for "freedom", while its original name of Abaqulusi reflects the AbaQulusi (Zulu), abaQulusi clan based in the loc ...

.

Second Boer War

Early battles

In 1899, Louis Botha fought in theSecond Boer War

The Second Boer War (, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, Transvaal War, Anglo–Boer War, or South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer republics (the South African Republic and ...

, initially joining the Krugersdorp Commando, continuing to fight under Lucas Meyer in Northern Natal, and later as a general commanding and leading Boer forces impressively at Colenso and Spion Kop. On the death of P. J. Joubert, he was made commander-in-chief of the Transvaal Boers

Boers ( ; ; ) are the descendants of the proto Afrikaans-speaking Free Burghers of the eastern Cape frontier in Southern Africa during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries. From 1652 to 1795, the Dutch East India Company controlled the Dutch ...

, where he demonstrated his abilities again at Belfast-Dalmanutha. After one of the battles at the Tugela River

The Tugela River (; ) is the largest river in KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa. With a total length of , and a drop of 1370 metres in the lower 480 km, it is one of the most important rivers of the country.

The river originates in M ...

, Botha granted a twenty-four-hour armistice to General Buller to enable him to bury his dead.

Capture of Winston Churchill

Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

revealed that General Botha was the man who captured him at the Battle of Chieveley. also claims that Botha captured Churchill at train ambush 15 November 1899. Churchill was not aware of the man's identity until 1902, when Botha travelled to London seeking loans to assist his country's reconstruction, and the two met at a private luncheon. The incident is also mentioned in Arthur Conan Doyle

Sir Arthur Ignatius Conan Doyle (22 May 1859 – 7 July 1930) was a British writer and physician. He created the character Sherlock Holmes in 1887 for ''A Study in Scarlet'', the first of four novels and fifty-six short stories about Hol ...

's book, '' The Great Boer War'', published in 1902. However more recent sources claim that Field cornet

Field cornet () is a term formerly used in South Africa for either a local government official or a military officer.

The office had its origins in the position of ''veldwachtmeester'' in the Dutch Cape colony, and was regarded as being equivalent ...

Sarel Oosthuizen was in fact the Boer soldier who, at gunpoint, captured Churchill. Another version claims that the unit to capture Churchill was the Italian Volunteer Legion and its commander, Camillo Ricchiardi.

Later campaigns

After the fall ofPretoria

Pretoria ( ; ) is the Capital of South Africa, administrative capital of South Africa, serving as the seat of the Executive (government), executive branch of government, and as the host to all foreign embassies to the country.

Pretoria strad ...

in June 1900, Louis Botha led a concentrated guerrilla

Guerrilla warfare is a form of unconventional warfare in which small groups of irregular military, such as rebels, Partisan (military), partisans, paramilitary personnel or armed civilians, which may include Children in the military, recruite ...

campaign against the British together with Koos de la Rey and Christiaan de Wet

Christiaan Rudolf de Wet (7 October 1854 – 3 February 1922) was a Boer general, rebel leader and politician.

Life

Born on the Leeuwkop farm, in the district of Smithfield in the Boer Republic of the Orange Free State, he later resided at ...

. The success of his measures was seen in the steady resistance offered by the Boers to the very close of the three-year war.

Role after the Boer War

Botha was prominent in efforts to achieve a peace with the British, representing the Boers at the peace negotiations in 1902, and was signatory to the

Botha was prominent in efforts to achieve a peace with the British, representing the Boers at the peace negotiations in 1902, and was signatory to the Treaty of Vereeniging

The Treaty of Vereeniging was a peace treaty, signed on 31 May 1902, that ended the Second Boer War between the South African Republic and the Orange Free State on the one side, and the United Kingdom on the other.

This settlement provided ...

. In the period of reconstruction under British rule, Botha went to Europe with de Wet and de la Rey to raise funds to enable the Boers to resume their former avocations. Botha, who was still looked upon as the leader of the Boer people, took a prominent part in politics, advocating always measures which he considered as tending to the maintenance of peace and good order and the re-establishment of prosperity in the Transvaal. His war record made him prominent in the politics of Transvaal and he was a major player in the postwar reconstruction of that country, founding with Jan Smuts

Field Marshal Jan Christian Smuts, (baptismal name Jan Christiaan Smuts, 24 May 1870 11 September 1950) was a South African statesman, military leader and philosopher. In addition to holding various military and cabinet posts, he served as P ...

the Het Volk Party in the Transvaal Colony

The Transvaal Colony () was the name used to refer to the Transvaal region during the period of direct British rule and military occupation between the end of the Second Boer War in 1902 when the South African Republic was dissolved, and the ...

in 1904, which served as a springboard to campaign for responsible self-government for the colony.

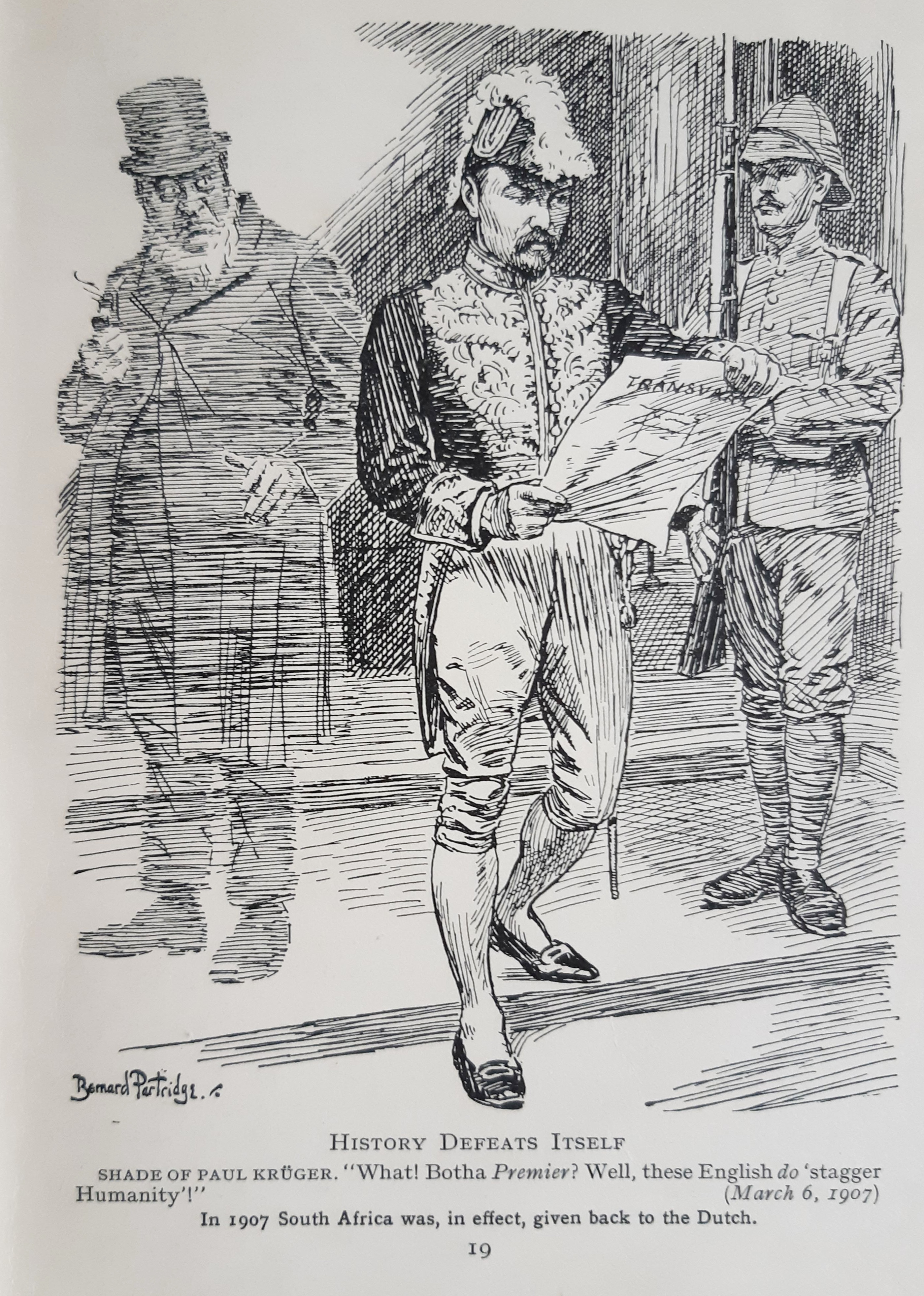

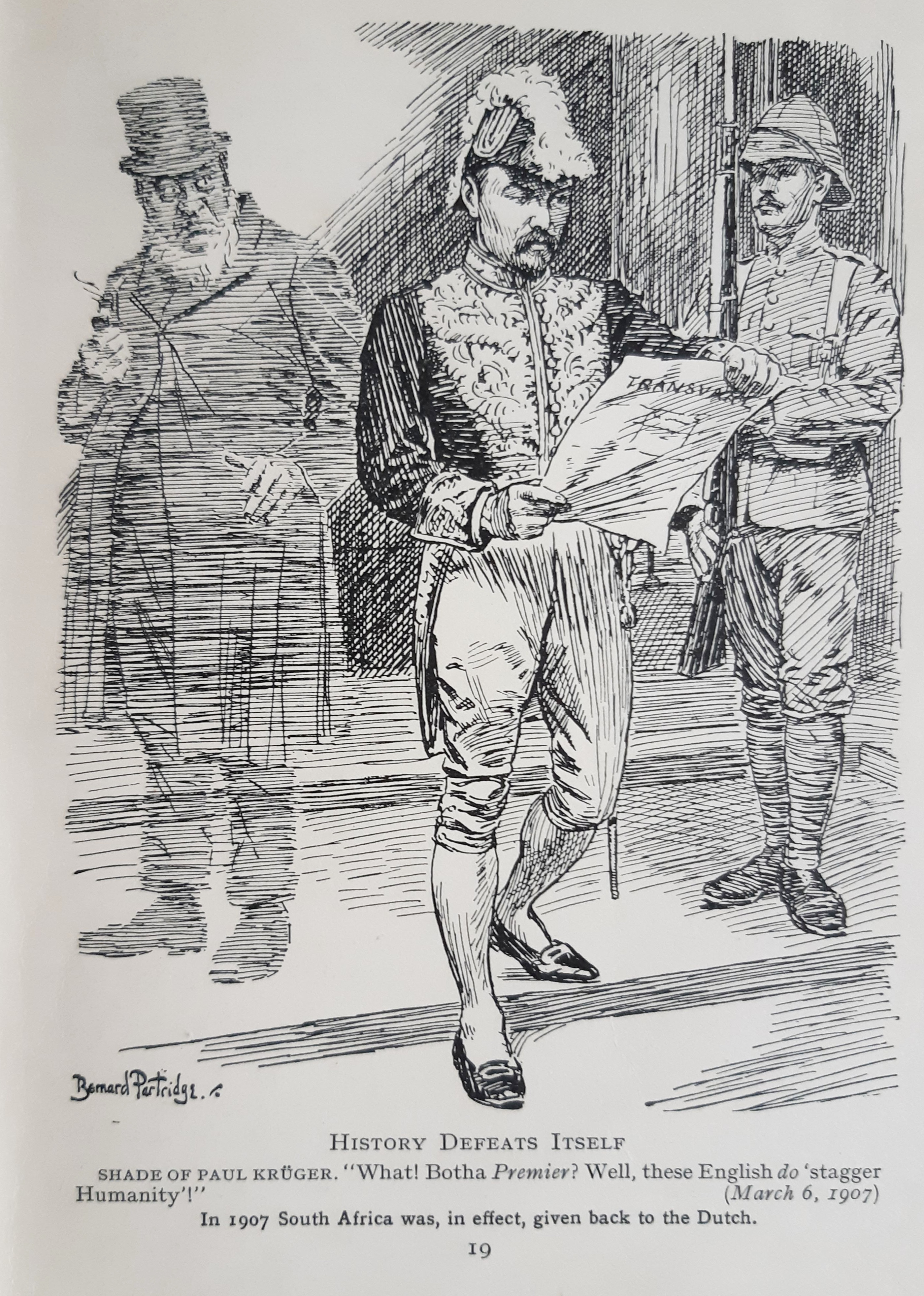

After the grant of self-government to the Transvaal on 6 December 1906 and the success of his Het Volk Party at the first elections in February 1907, Botha was called upon by Lord Selborne to form a government as Prime Minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

on 4 March 1907, and in the spring of the same year he took part in the conference of colonial premiers held in London. During his visit to England on this occasion General Botha declared the wholehearted adhesion of the Transvaal to the British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

, and his intention to work for the welfare of the country regardless of racial differences. The following year Botha participated in the National Convention (South Africa) which opened up the way for the passage of the South Africa Act of 1909 by the British parliament

The Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, and may also legislate for the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of ...

which in turn allowed for the formation of the Union of South Africa

The Union of South Africa (; , ) was the historical predecessor to the present-day South Africa, Republic of South Africa. It came into existence on 31 May 1910 with the unification of the British Cape Colony, Cape, Colony of Natal, Natal, Tra ...

.

When South Africa obtained dominion

A dominion was any of several largely self-governance, self-governing countries of the British Empire, once known collectively as the ''British Commonwealth of Nations''. Progressing from colonies, their degrees of self-governing colony, colon ...

status in 1910, Botha became the first Prime Minister of the Union of South Africa. In 1911, together with another Boer war hero, Jan Smuts

Field Marshal Jan Christian Smuts, (baptismal name Jan Christiaan Smuts, 24 May 1870 11 September 1950) was a South African statesman, military leader and philosopher. In addition to holding various military and cabinet posts, he served as P ...

, he formed the South African Party

The South African Party (, ) was a political party that existed in the Union of South Africa from 1911 to 1934.

History

The outline and foundation for the party was realized after the election of a 'South African party' in the 1910 South Af ...

, or SAP. Widely viewed as too conciliatory with Britain, Botha faced revolts from within his own party and opposition from James Barry Munnik Hertzog's National Party. He was a South African Freemason. Botha, like Hertzog, advocated for the preservation of black traditions, which ultimately led to the segregation of the black and white races.

Later career

After theFirst World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

started, he sent troops to take German South-West Africa

German South West Africa () was a colony of the German Empire from 1884 until 1915, though Germany did not officially recognise its loss of this territory until the 1919 Treaty of Versailles.

German rule over this territory was punctuated by ...

, a move unpopular among Boers, which provoked the Boer Revolt.

Praise for the British

At Versailles on 1 June 1919, 17 years after the signing of the Treaty of Vereeniging, General Botha, now a member of the British Empire Delegation, put his hand on Lord Milner's shoulder, and said "Seventeen years ago, my friend and I made peace at Vereeniging – it was a bitter peace for us, bitter hard. We lost all for which we had fought – our independence, our flag, our country. But we turned our thoughts and efforts then to saving our people; and they, the victors, helped us. It was a hard peace for us to accept, but as I know it now, when time has shown us the truth, it was not unjust – it was a generous peace that the British people made with us, and that is why we stand with them today side by side in the cause which has brought us all together." At the end of the War he briefly led a British Military Mission to Poland during thePolish–Soviet War

The Polish–Soviet War (14 February 1919 – 18 March 1921) was fought primarily between the Second Polish Republic and the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, following World War I and the Russian Revolution.

After the collapse ...

. He argued that the terms of the Versailles Treaty

The Treaty of Versailles was a peace treaty signed on 28 June 1919. As the most important treaty of World War I, it ended the state of war between Germany and most of the Allied Powers. It was signed in the Palace of Versailles, exactl ...

were too harsh on the Central Powers

The Central Powers, also known as the Central Empires,; ; , ; were one of the two main coalitions that fought in World War I (1914–1918). It consisted of the German Empire, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and the Kingdom of Bulga ...

, but signed the treaty. Botha was unwell for most of 1919. He was plagued by fatigue and ill health that arose from his robust waistline.

Marriage and children

Botha married Annie Emmett at the Dutch Reformed Church in Vryheid on 13 December 1886. Annie Botha later converted from Anglicanism to Dutch Reformed Protestantism. Shortly after their wedding, they settled on the Waterval Farm in Vryheid. They had five children together, three sons and two daughters.Death

General Louis Botha died ofheart failure

Heart failure (HF), also known as congestive heart failure (CHF), is a syndrome caused by an impairment in the heart's ability to Cardiac cycle, fill with and pump blood.

Although symptoms vary based on which side of the heart is affected, HF ...

at his home following an attack of Spanish influenza

The 1918–1920 flu pandemic, also known as the Great Influenza epidemic or by the common misnomer Spanish flu, was an exceptionally deadly global influenza pandemic caused by the H1N1 subtype of the influenza A virus. The earliest docum ...

on 27 August 1919 in the early hours of the morning. He was 56. His wife Annie was at home and was joined by Engelenburg who had acted as a private secretary to Botha. Botha was laid to rest in the Rebecca Street Cemetery in Pretoria.

Of Botha, Winston Churchill wrote in ''Great Contemporaries'' "The three most famous generals I have known in my life won no great battles over a foreign foe. Yet their names, which all begin with a 'B', are household words. They are General Booth, General Botha and General Baden-Powell..."

After Botha's death in 1919, Annie Botha settled on a farm in Rusthof and spent winters in Sezela, where she died in 1937.

Honours

Sculptor Raffaello Romanelli won the competition to create the equestrian statue of Botha that stands in front of theSouth African Parliament

The Parliament of the Republic of South Africa is South Africa's legislature. It is located in Cape Town; the country's legislative capital.

Under the present Constitution of South Africa, the bicameral Parliament comprises a National Asse ...

building but died before completing it. His son Romano Romanelli, and his grandson's family Arend Botha was contracted to finish his father's work.

In 1917, parts of the M11 route in Johannesburg

Johannesburg ( , , ; Zulu language, Zulu and Xhosa language, Xhosa: eGoli ) (colloquially known as Jozi, Joburg, Jo'burg or "The City of Gold") is the most populous city in South Africa. With 5,538,596 people in the City of Johannesburg alon ...

, previously named Morgan Road and Pretoria Main Road,were renamed to Louis Botha Avenue.

Sculptor Anton van Wouw created a statue of Botha in Durban unveiled in 1921.

Sculptor Coert Steynberg was commissioned to create the equestrian statue of Botha in front of the Union Buildings in Pretoria. It was unveiled in 1946.

The General Botha Regiment of the South African Army

The South African Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of South Africa, a part of the South African National Defence Force (SANDF), along with the South African Air Force, South African Navy and South African Military Health Servi ...

is named after Botha.

References

Sources

* * * * * * *Further reading

Biographical

*Historical

* (insights of Botha) * (comprehensive commentaries on Smuts and Botha, or as William's titled them in the last chapter of this book ''par nobile fratrum'' *Fiction

* (a heroic Boer character in this Australian/Boer War novel)External links

* * Anne SamsonBotha, Louis

in

, - , - , - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Botha, Louis 1862 births 1919 deaths Afrikaner people Prime ministers of South Africa Members of the House of Assembly (South Africa) Members of the Dutch Reformed Church in South Africa South African Republic generals South African Republic military personnel of the Second Boer War South African Party (Union of South Africa) politicians World War I political leaders South African military personnel of World War I Deaths from the Spanish flu pandemic Infectious disease deaths in South Africa People from Greytown, KwaZulu-Natal South African people of Dutch descent 1900s in the South African Republic 1900s in Transvaal 1910s in South Africa 20th-century South African people South African members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom South African Freemasons Colony of Natal people Military personnel from KwaZulu-Natal