List Of Common Misconceptions About History on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Each entry on this list of common misconceptions is worded as a correction; the misconceptions themselves are implied rather than stated. These entries are concise summaries; the main subject articles can be consulted for more detail.

* The ancient Greeks did not use the word " idiot" () to disparage people who did not take part in civic life. An was simply a private citizen as opposed to a government official. The word also meant any sort of non-expert or layman,

* The ancient Greeks did not use the word " idiot" () to disparage people who did not take part in civic life. An was simply a private citizen as opposed to a government official. The word also meant any sort of non-expert or layman,''

''s.v.''

* Wealthy Ancient Romans did not use rooms called ''vomitoria'' to purge food during meals so they could continue eating

* Wealthy Ancient Romans did not use rooms called ''vomitoria'' to purge food during meals so they could continue eating

* George Washington also did not say "I cannot tell a lie" when being caught cutting down his father's cherry tree. Both the phrase and the tree were a fabricated anecdote created by one of Washington's biographers, Mason Locke Weems, to portray him as exceptionally honest.

* George Washington also did not say "I cannot tell a lie" when being caught cutting down his father's cherry tree. Both the phrase and the tree were a fabricated anecdote created by one of Washington's biographers, Mason Locke Weems, to portray him as exceptionally honest.

*

*  *

* a.

b.

c. (See also:

* Betsy Ross did not design or make the first official U.S. flag, despite it being widely known as the Betsy Ross flag. The claim was first made by her grandson a century later.

* Betsy Ross did not design or make the first official U.S. flag, despite it being widely known as the Betsy Ross flag. The claim was first made by her grandson a century later. *

*  * While it was praised by one architectural magazine before it was built as "the best high apartment of the year", the Pruitt–Igoe

* While it was praised by one architectural magazine before it was built as "the best high apartment of the year", the Pruitt–Igoe

Ancient history

* The Pyramids of Egypt were not constructed withslave labor

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

. Archaeological evidence shows that the laborers were a combination of skilled workers and poor farmers working in the off-season with the participants paid in high-quality food and tax exemptions.Herodotus

Herodotus (; BC) was a Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus (now Bodrum, Turkey), under Persian control in the 5th century BC, and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria, Italy. He wrote the '' Histori ...

, and the idea that they were Israelites

Israelites were a Hebrew language, Hebrew-speaking ethnoreligious group, consisting of tribes that lived in Canaan during the Iron Age.

Modern scholarship describes the Israelites as emerging from indigenous Canaanites, Canaanite populations ...

arose centuries after the pyramids were constructed.Galley

A galley is a type of ship optimised for propulsion by oars. Galleys were historically used for naval warfare, warfare, Maritime transport, trade, and piracy mostly in the seas surrounding Europe. It developed in the Mediterranean world during ...

s in ancient times were not commonly operated by chained slaves or prisoners, as depicted in films such as '' Ben Hur'', but by paid laborers or soldiers, with slaves used only in times of crisis, in some cases even gaining freedom after the crisis was averted. Ptolemaic Egypt Ptolemaic is the adjective formed from the name Ptolemy, and may refer to:

Pertaining to the Ptolemaic dynasty

* Ptolemaic dynasty, the Macedonian Greek dynasty that ruled Egypt founded in 305 BC by Ptolemy I Soter

*Ptolemaic Kingdom

Pertaining ...

was a possible exception.Tutankhamun

Tutankhamun or Tutankhamen, (; ), was an Egyptian pharaoh who ruled during the late Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt, Eighteenth Dynasty of ancient Egypt. Born Tutankhaten, he instituted the restoration of the traditional polytheistic form of an ...

's tomb is not inscribed with a curse on those who disturb it. This was a media invention of 20th-century tabloid journalists.Minoan civilization

The Minoan civilization was a Bronze Age culture which was centered on the island of Crete. Known for its monumental architecture and energetic art, it is often regarded as the first civilization in Europe. The ruins of the Minoan palaces at K ...

was not destroyed by the eruption of Thera and was not the inspiration for Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

's parable of Atlantis

Atlantis () is a fictional island mentioned in Plato's works '' Timaeus'' and ''Critias'' as part of an allegory on the hubris of nations. In the story, Atlantis is described as a naval empire that ruled all Western parts of the known world ...

. * The ancient Greeks did not use the word " idiot" () to disparage people who did not take part in civic life. An was simply a private citizen as opposed to a government official. The word also meant any sort of non-expert or layman,

* The ancient Greeks did not use the word " idiot" () to disparage people who did not take part in civic life. An was simply a private citizen as opposed to a government official. The word also meant any sort of non-expert or layman,Oxford English Dictionary

The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' (''OED'') is the principal historical dictionary of the English language, published by Oxford University Press (OUP), a University of Oxford publishing house. The dictionary, which published its first editio ...

''''s.v.''

Ancient Rome

* The so-called Roman salute, in which the arm is fully extended forwards or diagonally with palm down and fingers touching, was not used in ancient Rome. The gesture was first associated with ancient Rome in the 1784 painting '' The Oath of the Horatii'' by the French artistJacques-Louis David

Jacques-Louis David (; 30 August 1748 – 29 December 1825) was a French painter in the Neoclassicism, Neoclassical style, considered to be the preeminent painter of the era. In the 1780s, his cerebral brand of history painting marked a change in ...

, which inspired later salutes, most notably the Nazi salute

The Nazi salute, also known as the Hitler salute, or the ''Sieg Heil'' salute, is a gesture that was used as a greeting in Nazi Germany. The salute is performed by extending the right arm from the shoulder into the air with a straightened han ...

.Scipio Aemilianus

Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus Aemilianus (185 BC – 129 BC), known as Scipio Aemilianus or Scipio Africanus the Younger, was a Roman general and statesman noted for his military exploits in the Third Punic War against Carthage and durin ...

did not sow salt over the city of Carthage

Carthage was an ancient city in Northern Africa, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the classic ...

after defeating it in the Third Punic War

The Third Punic War (149–146 BC) was the third and last of the Punic Wars fought between Carthage and Rome. The war was fought entirely within Carthaginian territory, in what is now northern Tunisia. When the Second Punic War ended in 20 ...

.Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (12 or 13 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in Caesar's civil wa ...

was not born via caesarean section

Caesarean section, also known as C-section, cesarean, or caesarean delivery, is the Surgery, surgical procedure by which one or more babies are Childbirth, delivered through an incision in the mother's abdomen. It is often performed because va ...

. Such a procedure would have been fatal to the mother at the time, and Caesar's mother was still alive when he was 45 years old.Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (12 or 13 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in Caesar's civil wa ...

by William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

.Middle Ages

Europe

* TheMiddle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

were not "a time of ignorance, barbarism and superstition"; the Church did not place religious authority over personal experience and rational activity; and the term " Dark Ages" is rejected by modern historians.Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus (; between 25 August and 31 October 1451 – 20 May 1506) was an Italians, Italian explorer and navigator from the Republic of Genoa who completed Voyages of Christopher Columbus, four Spanish-based voyages across the At ...

' efforts to obtain support for his voyages were not hampered by belief in a flat Earth, but by valid worries that the East Indies were farther than he realized.Washington Irving

Washington Irving (April 3, 1783 – November 28, 1859) was an American short-story writer, essayist, biographer, historian, and diplomat of the early 19th century. He wrote the short stories "Rip Van Winkle" (1819) and "The Legend of Sleepy ...

in '' A History of the Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus''.Leif Erikson

Leif Erikson, also known as Leif the Lucky (), was a Norsemen, Norse explorer who is thought to have been the first European to set foot on continental Americas, America, approximately half a millennium before Christopher Columbus. According ...

, and possibly other Vikings before him, explored Vinland

Vinland, Vineland, or Winland () was an area of coastal North America explored by Vikings. Leif Erikson landed there around 1000 AD, nearly five centuries before the voyages of Christopher Columbus and John Cabot. The name appears in the V ...

, an area of coastal North America. Ruins at L'Anse aux Meadows

L'Anse aux Meadows () is an archaeological site, first excavated in the 1960s, of a Norse colonization of North America, Norse settlement dating to approximately 1,000 years ago. The site is located on the northernmost tip of the island of Newf ...

prove that at least one Norse settlement was built in Newfoundland, confirming a story in the '' Saga of Erik the Red''.

Vikings

* There is no evidence that Viking warriors wore horns on their helmets; this would have been impractical in battle.skald

A skald, or skáld (Old Norse: ; , meaning "poet"), is one of the often named poets who composed skaldic poetry, one of the two kinds of Old Norse poetry in alliterative verse, the other being Eddic poetry. Skaldic poems were traditionally compo ...

ic poetic use of ''ór bjúgviðum hausa'' (branches of skulls) to refer to drinking horn

A drinking horn is the horn (anatomy), horn of a bovid used as a cup. Drinking horns are known from Classical Antiquity, especially the Balkans. They remained in use for ceremonial purposes throughout the Middle Ages and the Early Modern period ...

s.Sagas of Icelanders

The sagas of Icelanders (, ), also known as family sagas, are a subgenre, or text group, of Icelandic Saga, sagas. They are prose narratives primarily based on historical events that mostly took place in Iceland in the ninth, tenth, and earl ...

, Hrafna-Flóki Vilgerðarson saw icebergs on the island when he traveled there, and named the island after them.Early modern

* TheMexica

The Mexica (Nahuatl: ; singular ) are a Nahuatl-speaking people of the Valley of Mexico who were the rulers of the Triple Alliance, more commonly referred to as the Aztec Empire. The Mexica established Tenochtitlan, a settlement on an island ...

people of the Aztec Empire

The Aztec Empire, also known as the Triple Alliance (, Help:IPA/Nahuatl, �jéːʃkaːn̥ t͡ɬaʔtoːˈlóːjaːn̥ or the Tenochca Empire, was an alliance of three Nahuas, Nahua altepetl, city-states: , , and . These three city-states rul ...

did not mistake Hernán Cortés

Hernán Cortés de Monroy y Pizarro Altamirano, 1st Marquis of the Valley of Oaxaca (December 1485 – December 2, 1547) was a Spanish ''conquistador'' who led an expedition that caused the fall of the Aztec Empire and brought large portions o ...

and his landing party for gods during Cortés' conquest of the empire. This notion came from Francisco López de Gómara, who never went to Mexico and concocted the myth while working for the retired Cortés in Spain years after the conquest.Dutch Golden Age

The Dutch Golden Age ( ) was a period in the history of the Netherlands which roughly lasted from 1588, when the Dutch Republic was established, to 1672, when the '' Rampjaar'' occurred. During this period, Dutch trade, scientific development ...

wore black clothes primarily as a status symbol rather than out of Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to rid the Church of England of what they considered to be Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should b ...

self-restraint. The clothes attracted status from the difficulty of the dyeing process and the cost of elaborate embellishments.Shah Jahan

Shah Jahan I, (Shahab-ud-Din Muhammad Khurram; 5 January 1592 – 22 January 1666), also called Shah Jahan the Magnificent, was the Emperor of Hindustan from 1628 until his deposition in 1658. As the fifth Mughal emperor, his reign marked the ...

, the Indian Mughal Emperor

The emperors of the Mughal Empire, who were all members of the Timurid dynasty (House of Babur), ruled the empire from its inception on 21 April 1526 to its dissolution on 21 September 1857. They were supreme monarchs of the Mughal Empire in ...

who commissioned the Taj Mahal

The Taj Mahal ( ; ; ) is an ivory-white marble mausoleum on the right bank of the river Yamuna in Agra, Uttar Pradesh, India. It was commissioned in 1631 by the fifth Mughal Empire, Mughal emperor, Shah Jahan () to house the tomb of his belo ...

, did not cut off the hands of the rumored 40,000 workers or lead designers so as to not allow the construction of another monument more beautiful than the Taj Mahal. This is an urban myth that goes back to the 1960s.Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton () was an English polymath active as a mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author. Newton was a key figure in the Scientific Revolution and the Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment that followed ...

was inspired to research the nature of gravity when an apple fell on his head is almost certainly apocryphal. All Newton himself ever said was that the idea came to him as he sat "in a contemplative mood" and "was occasioned by the fall of an apple".Marie Antoinette

Marie Antoinette (; ; Maria Antonia Josefa Johanna; 2 November 1755 – 16 October 1793) was the last List of French royal consorts, queen of France before the French Revolution and the establishment of the French First Republic. She was the ...

did not say " let them eat cake" when she heard that the French peasantry were starving due to a shortage of bread. The phrase was first published in Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher ('' philosophe''), writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects ...

's '' Confessions'', written when Marie Antoinette was only nine years old and not attributed to her, just to "a great princess". It was first attributed to her in 1843.North America

* The early settlers (commonly known as Pilgrims) of thePlymouth Colony

Plymouth Colony (sometimes spelled Plimouth) was the first permanent English colony in New England from 1620 and the third permanent English colony in America, after Newfoundland and the Jamestown Colony. It was settled by the passengers on t ...

in North America usually did not wear all black, and their capotains (hats) did not include buckles. Instead, their fashion was based on that of the late Elizabethan era.Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to rid the Church of England of what they considered to be Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should b ...

s, who settled in the adjacent Massachusetts Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony (1628–1691), more formally the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, was an English settlement on the east coast of North America around Massachusetts Bay, one of the several colonies later reorganized as the Province of M ...

shortly after the Pilgrims arrived in Plymouth, ''did'' frequently wear all black.)Salem witch trials

The Salem witch trials were a series of hearings and prosecutions of people accused of witchcraft in Province of Massachusetts Bay, colonial Massachusetts between February 1692 and May 1693. More than 200 people were accused. Not everyone wh ...

. Of the accused, nineteen people convicted of witchcraft were executed by hanging, at least five died in prison, and one man was pressed to death by stones while trying to extract a confession from him.George Washington

George Washington (, 1799) was a Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father and the first president of the United States, serving from 1789 to 1797. As commander of the Continental Army, Washington led Patriot (American Revoluti ...

did not have wooden teeth. His dentures were made of lead, gold, hippopotamus ivory, the teeth of various animals, including horse and donkey teeth, * George Washington also did not say "I cannot tell a lie" when being caught cutting down his father's cherry tree. Both the phrase and the tree were a fabricated anecdote created by one of Washington's biographers, Mason Locke Weems, to portray him as exceptionally honest.

* George Washington also did not say "I cannot tell a lie" when being caught cutting down his father's cherry tree. Both the phrase and the tree were a fabricated anecdote created by one of Washington's biographers, Mason Locke Weems, to portray him as exceptionally honest.United States Declaration of Independence

The Declaration of Independence, formally The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen States of America in the original printing, is the founding document of the United States. On July 4, 1776, it was adopted unanimously by the Second Continen ...

did not occur on July 4, 1776. After the Second Continental Congress

The Second Continental Congress (1775–1781) was the meetings of delegates from the Thirteen Colonies that united in support of the American Revolution and American Revolutionary War, Revolutionary War, which established American independence ...

voted to declare independence on July 2, the final language of the document was approved on July 4, and it was printed and distributed on July 4–5.Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin (April 17, 1790) was an American polymath: a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher and Political philosophy, political philosopher.#britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the m ...

did not propose that the wild turkey

The wild turkey (''Meleagris gallopavo'') is an upland game bird native to North America, one of two extant species of Turkey (bird), turkey and the heaviest member of the order Galliformes. It is the ancestor to the domestic turkey (''M. g. dom ...

be used as the symbol for the United States instead of the bald eagle. While he did serve on a commission that tried to design a seal after the Declaration of Independence, his proposal was an image of Moses. His objections to the eagle as a national symbol and preference for the turkey were stated in a 1784 letter to his daughter in response to the Society of the Cincinnati

The Society of the Cincinnati is a lineage society, fraternal, hereditary society founded in 1783 to commemorate the American Revolutionary War that saw the creation of the United States. Membership is largely restricted to descendants of milita ...

's use of the former; he never expressed that sentiment publicly.Modern

*

* Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

Bonaparte was not especially short for a Frenchman of his time. He was the height of an average French male in 1800, but short for an aristocrat or officer.Great Sphinx of Giza

The Great Sphinx of Giza is a limestone statue of a reclining sphinx, a mythical creature with the head of a human and the body of a lion. Facing east, it stands on the Giza Plateau on the west bank of the Nile in Giza, Egypt. The original sh ...

was not shot off by Napoleon's troops during the French campaign in Egypt (1798–1801); it has been missing since at least the 10th century.Battle of Puebla

The Battle of Puebla (; ), also known as the Battle of May 5 () took place on 5 May 1862, near Puebla de los Ángeles, during the second French intervention in Mexico. French troops under the command of Charles de Lorencez repeatedly failed to s ...

on May 5, 1862. Mexico's Declaration of Independence from Spain in 1810 is celebrated on September 16. *

* Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein (14 March 187918 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist who is best known for developing the theory of relativity. Einstein also made important contributions to quantum mechanics. His mass–energy equivalence f ...

did not fail mathematics classes in school. Einstein remarked, "I never failed in mathematics.... Before I was fifteen I had mastered differential and integral calculus."Alfred Nobel

Alfred Bernhard Nobel ( ; ; 21 October 1833 – 10 December 1896) was a Swedish chemist, inventor, engineer, and businessman. He is known for inventing dynamite, as well as having bequeathed his fortune to establish the Nobel Prizes. He also m ...

did not omit mathematics in the Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; ; ) are awards administered by the Nobel Foundation and granted in accordance with the principle of "for the greatest benefit to humankind". The prizes were first awarded in 1901, marking the fifth anniversary of Alfred N ...

due to a rivalry with mathematician Gösta Mittag-Leffler

Magnus Gustaf "Gösta" Mittag-Leffler (16 March 1846 – 7 July 1927) was a Sweden, Swedish mathematician. His mathematical contributions are connected chiefly with the theory of functions that today is called complex analysis. He founded the pre ...

, as there is little evidence the two ever met, nor was it because Nobel's spouse had an affair with a mathematician, as Nobel was never married. The more likely explanation is that Nobel believed mathematics was too theoretical to benefit humankind, as well as his personal lack of interest in the field.b.

c.

Nobel Prize controversies

Since the first award in 1901, conferment of the Nobel Prize has engendered criticismGrigori Rasputin

Grigori Yefimovich Rasputin ( – ) was a Russian Mysticism, mystic and faith healer. He is best known for having befriended the imperial family of Nicholas II of Russia, Nicholas II, the last Emperor of all the Russias, Emperor of Russia, th ...

was not assassinated by being fed cyanide-laced cakes and wine

Wine is an alcoholic drink made from Fermentation in winemaking, fermented fruit. Yeast in winemaking, Yeast consumes the sugar in the fruit and converts it to ethanol and carbon dioxide, releasing heat in the process. Wine is most often made f ...

, shot multiple times, and then thrown into the Little Nevka river when he survived the former two. A contemporary autopsy reported that he was just killed with gunshots. A sensationalized account from the memoirs of co-conspirator Prince

A prince is a male ruler (ranked below a king, grand prince, and grand duke) or a male member of a monarch's or former monarch's family. ''Prince'' is also a title of nobility (often highest), often hereditary, in some European states. The ...

Felix Yusupov is the only source of this story.Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who, upon assuming office as Prime Minister of Italy, Prime Minister, became the dictator of Fascist Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 un ...

did not "make the trains run on time". Much of the repair work had been performed before he and the Fascist Party came to power in 1922. Moreover, the Italian railways' supposed adherence to timetables was more propaganda than reality.invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland, also known as the September Campaign, Polish Campaign, and Polish Defensive War of 1939 (1 September – 6 October 1939), was a joint attack on the Second Polish Republic, Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany, the Slovak R ...

in 1939. This story may have originated from German propaganda efforts following the charge at Krojanty.occupation of Denmark

At the outset of World War II in September 1939, Denmark declared itself Neutral countries in World War II, neutral, but that neutrality did not prevent Nazi Germany from Military occupation, occupying the country soon after the outbreak of ...

by the Nazis during World War II, King Christian X of Denmark did not thwart Nazi attempts to identify Jews by wearing a yellow star himself. Jews in Denmark were never forced to wear the Star of David

The Star of David (, , ) is a symbol generally recognized as representing both Jewish identity and Judaism. Its shape is that of a hexagram: the compound of two equilateral triangles.

A derivation of the Seal of Solomon was used for decora ...

. The Danish resistance did help most Jews flee the country before the end of the war.skinhead

A skinhead or skin is a member of a subculture that originated among working-class youth in London, England, in the 1960s. It soon spread to other parts of the United Kingdom, with a second working-class skinhead movement emerging worldwide i ...

s are white supremacists; many skinheads identify as left-wing or apolitical, and many oppose racism, such as the Skinheads Against Racial Prejudice

Skinheads Against Racial Prejudice (SHARP) are anti-racist skinheads who oppose white power skinheads, neo-fascists and other political racists, particularly if they identify themselves as skinheads. SHARPs claim to reclaim the original multicul ...

. Originating from the 1960s British working class, many of its initial adherents were black

Black is a color that results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without chroma, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness.Eva Heller, ''P ...

and West Indian

A West Indian is a native or inhabitant of the West Indies (the Antilles and the Lucayan Archipelago). According to the ''Oxford English Dictionary'' (''OED''), the term ''West Indian'' in 1597 described the indigenous inhabitants of the West In ...

; it became associated with white supremacy in the 1970s as a result of far-right groups like the National Front recruiting from the subculture for grassroot support.United States

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

did not write his Gettysburg Address

The Gettysburg Address is a Public speaking, speech delivered by Abraham Lincoln, the 16th President of the United States, U.S. president, following the Battle of Gettysburg during the American Civil War. The speech has come to be viewed as one ...

speech on the back of an envelope on his train ride to Gettysburg. The speech was substantially complete before Lincoln left Washington for Gettysburg.Emancipation Proclamation

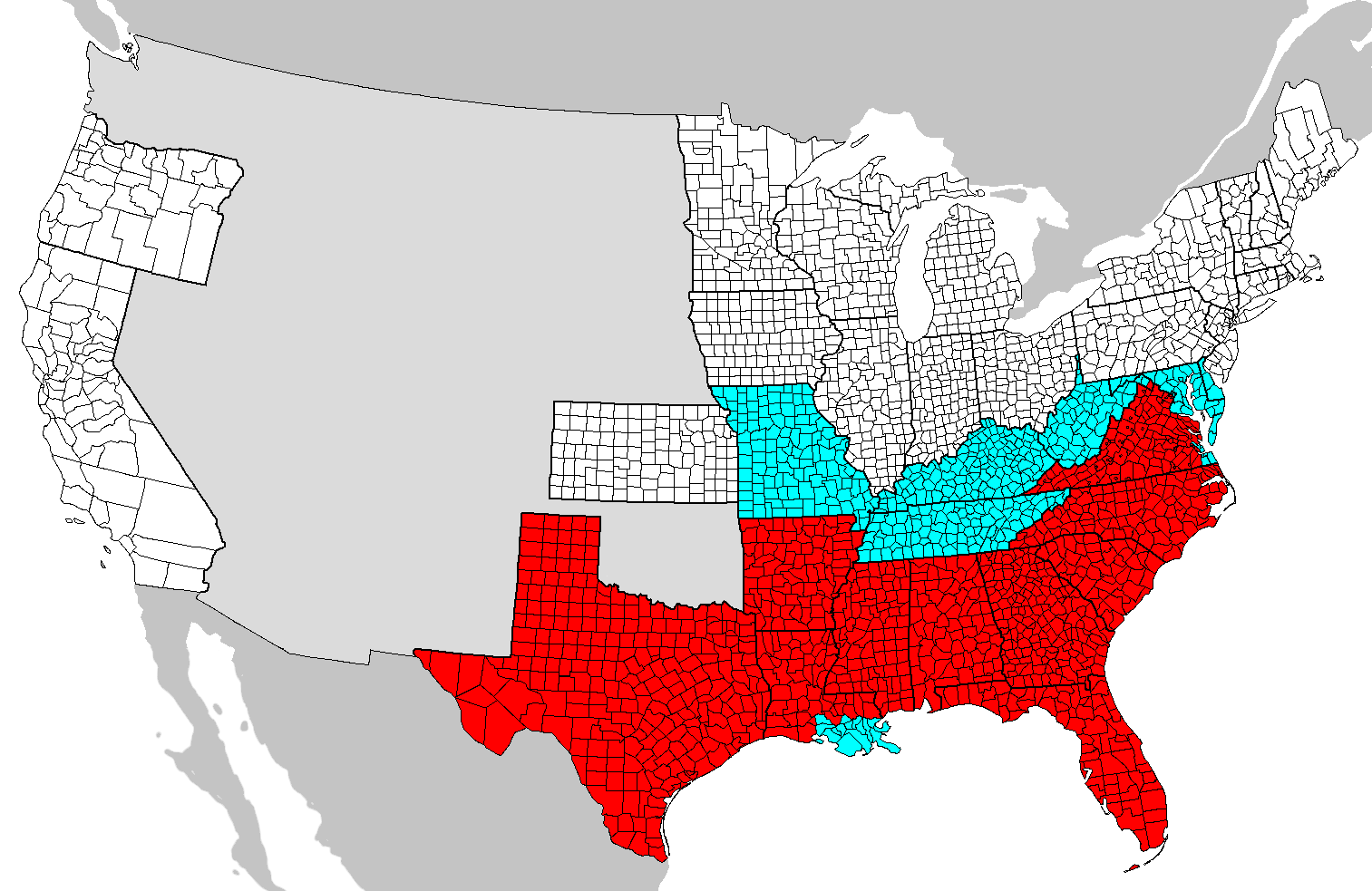

The Emancipation Proclamation, officially Proclamation 95, was a presidential proclamation and executive order issued by United States President Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, during the American Civil War. The Proclamation had the eff ...

did not free all slaves in the United States; the Proclamation applied in the ten states that were still in rebellion

Rebellion is an uprising that resists and is organized against one's government. A rebel is a person who engages in a rebellion. A rebel group is a consciously coordinated group that seeks to gain political control over an entire state or a ...

in 1863, and thus did not cover the nearly five hundred thousand slaves in the slaveholding border states that had not seceded.Abolition of slavery timeline

The abolition of slavery occurred at different times in different countries. It frequently occurred sequentially in more than one stage – for example, as abolition of the trade in slavery, slaves in a specific country, and then as abolition of ...

)

* Likewise, the June 19, 1865 order celebrated annually as "Juneteenth

Juneteenth is a federal holiday in the United States, federal holiday in the United States. It is celebrated annually on June 19 to commemorate the End of slavery in the United States, ending of slavery in the United States. The holiday's n ...

" only applied ''in Texas'', not the United States at large. The Thirteenth Amendment, ratified and proclaimed in December 1865, was the article that banned slavery nationwide except as punishment for a crime.Alaska Purchase

The Alaska Purchase was the purchase of Russian colonization of North America, Alaska from the Russian Empire by the United States for a sum of $7.2 million in 1867 (equivalent to $ million in ). On May 15 of that year, the United St ...

was generally viewed as positive or neutral in the United States, both among the public and the press. The opponents of the purchase who characterized it as " Seward's Folly", alluding to William H. Seward, the Secretary of State who negotiated it, represented a minority opinion at the time.Cowboy hat

The cowboy hat is a high-crowned, wide-brimmed hat best known as the defining piece of attire for the North American cowboy. Today it is worn by many people, and is particularly associated with ranch workers in the United States, Canada, Mexico, C ...

s were not initially popular in the Western American frontier, with derby or bowler hats being the typical headgear of choice.Boss of the Plains

The Boss of the Plains was a lightweight all-weather hat designed in 1865 by John Batterson Stetson, John B. Stetson for the demands of the American West. It was intended to be durable, waterproof and elegant. The term "Stetson" eventually becam ...

" model in the years following the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

was the primary driving force behind the cowboy hat's popularity, with its characteristic dented top not becoming standard until near the end of the 19th century.Great Chicago Fire

The Great Chicago Fire was a conflagration that burned in the American city of Chicago, Illinois during October 8–10, 1871. The fire killed approximately 300 people, destroyed roughly of the city including over 17,000 structures, and left mor ...

of 1871 was not caused by Mrs. O'Leary's cow kicking over a lantern. A newspaper reporter later admitted to having invented the story to make colorful copy.William Randolph Hearst

William Randolph Hearst (; April 29, 1863 – August 14, 1951) was an American newspaper publisher and politician who developed the nation's largest newspaper chain and media company, Hearst Communications. His extravagant methods of yellow jou ...

: "There will be no war. I wish to return," nor that Hearst responded: "Please remain. You furnish the pictures, and I'll furnish the war". The anecdote was originally included in a book by James Creelman and probably never happened.Mary Mallon

Mary Mallon (September 23, 1869 – November 11, 1938), commonly known as Typhoid Mary, was an Irish Americans, Irish-born American cook who is believed to have infected between 51 and 122 people with typhoid fever. The infections caused ...

, known as " Typhoid Mary", testified at her 1909 trial that she did not believe she was contagious while an asymptomatic carrier

An asymptomatic carrier is a person or other organism that has become infected with a pathogen, but shows no signs or symptoms.

Although unaffected by the pathogen, carriers can transmit it to others or develop symptoms in later stages of the d ...

of the bacteria

Bacteria (; : bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one Cell (biology), biological cell. They constitute a large domain (biology), domain of Prokaryote, prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micr ...

'' Salmonella typhi''.Ellis Island

Ellis Island is an island in New York Harbor, within the U.S. states of New Jersey and New York (state), New York. Owned by the U.S. government, Ellis Island was once the busiest immigrant inspection and processing station in the United State ...

. Officials there kept no records other than checking ship manifests created at the point of origin, and there was simply no paperwork that would have let them recast surnames, let alone any law. At the time in New York, anyone could change the spelling of their name simply by using that new spelling.Prohibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcoholic b ...

did not make drinking alcohol illegal in the United States. The Eighteenth Amendment and the subsequent Volstead Act prohibited the production, sale, and transport of "intoxicating liquors" within the United States, but their possession and consumption were never outlawed.Orson Welles

George Orson Welles (May 6, 1915 – October 10, 1985) was an American director, actor, writer, producer, and magician who is remembered for his innovative work in film, radio, and theatre. He is among the greatest and most influential film ...

' 1938 radio adaptation of H.G. Wells

Herbert George Wells (21 September 1866 – 13 August 1946) was an English writer, prolific in many genres. He wrote more than fifty novels and dozens of short stories. His non-fiction output included works of social commentary, politics, hist ...

' ''The War of the Worlds

''The War of the Worlds'' is a science fiction novel by English author H. G. Wells. It was written between 1895 and 1897, and serialised in '' Pearson's Magazine'' in the UK and ''Cosmopolitan'' magazine in the US in 1897. The full novel was ...

''. Only a very small share of the radio audience was listening to it, but newspapers, being eager to discredit radio as a competitor for advertising, played up isolated reports of incidents and increased emergency calls. Both Welles and CBS, which had initially reacted apologetically, later came to realize that the myth benefited them and actively embraced it in later years.flying saucer

A flying saucer, or flying disc, is a purported type of disc-shaped unidentified flying object (UFO). The term was coined in 1947 by the United States (US) news media for the objects pilot Kenneth Arnold UFO sighting, Kenneth Arnold claimed fl ...

''; he did not use that phrase when describing his 1947 UFO sighting at Mount Rainier

Mount Rainier ( ), also known as Tahoma, is a large active stratovolcano in the Cascade Range of the Pacific Northwest in the United States. The mountain is located in Mount Rainier National Park about south-southeast of Seattle. With an off ...

, Washington. '' The East Oregonian'', the first newspaper to report on the incident, merely quoted him as saying the objects "flew like a saucer" and were "flat like a pie pan".Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

did not order the construction of the Interstate Highway System

The Dwight D. Eisenhower National System of Interstate and Defense Highways, commonly known as the Interstate Highway System, or the Eisenhower Interstate System, is a network of controlled-access highways that forms part of the National Hi ...

for the sole purpose of evacuating cities in the event of nuclear warfare. While military motivations were present, the primary motivations were civilian.Rosa Parks

Rosa Louise McCauley Parks (February 4, 1913 – October 24, 2005) was an American civil rights activist. She is best known for her refusal to move from her seat on a Montgomery, Alabama, bus, in defiance of Jim Crow laws, which sparke ...

was not sitting in the front ("white") section of the bus during the event that made her famous and incited the Montgomery bus boycott

The Montgomery bus boycott was a political and social boycott, protest campaign against the policy of racial segregation on the public transit system of Montgomery, Alabama. It was a foundational event in the civil rights movement in the United ...

. Rather, she was sitting in the front of the back ("colored") section of the bus, where African Americans were expected to sit, and rejected an order from the driver to vacate her seat in favor of a white passenger when the "white" section of the bus had become full.W. E. B. Du Bois

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois ( ; February 23, 1868 – August 27, 1963) was an American sociologist, socialist, historian, and Pan-Africanist civil rights activist.

Born in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, Du Bois grew up in a relativel ...

did not renounce his U.S. citizenship while living in Ghana shortly before his death.passport

A passport is an official travel document issued by a government that certifies a person's identity and nationality for international travel. A passport allows its bearer to enter and temporarily reside in a foreign country, access local aid ...

while he was already in Ghana. After leaving the embassy, he stated his intention to renounce his citizenship in protest, but while he took Ghanaian citizenship, he never actually renounced his American citizenship.jelly doughnut

A jelly doughnut, or jam doughnut, is a doughnut with a fruit preserve filling.

Varieties include the German ''Berliner (pastry), Berliner'', the Polish ''pączki'', the Jewish ''sufganiyot'', the Southern European ''krafne'' and the Italian '' ...

, amusing Germans. * While it was praised by one architectural magazine before it was built as "the best high apartment of the year", the Pruitt–Igoe

* While it was praised by one architectural magazine before it was built as "the best high apartment of the year", the Pruitt–Igoe housing project

Public housing, also known as social housing, refers to Subsidized housing, subsidized or affordable housing provided in buildings that are usually owned and managed by local government, central government, nonprofit organizations or a ...

in St. Louis, Missouri never won any awards for its design.Apollo program

The Apollo program, also known as Project Apollo, was the United States human spaceflight program led by NASA, which Moon landing, landed the first humans on the Moon in 1969. Apollo followed Project Mercury that put the first Americans in sp ...

was worth the time and money invested peaked at 51% for a few months after the 1969 Apollo 11 moon landing, and otherwise had fluctuated between 35–45% support.potassium cyanide

Potassium cyanide is a compound with the formula KCN. It is a colorless salt, similar in appearance to sugar, that is highly soluble in water. Most KCN is used in gold mining, organic synthesis, and electroplating. Smaller applications include ...

-fruit punch mix ingested as part of the Jonestown massacre.Asia

*Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

did not say " Let China sleep, for when she wakes she will shake the world," or any similar declaration. References

{{Reflisthistory

History is the systematic study of the past, focusing primarily on the Human history, human past. As an academic discipline, it analyses and interprets evidence to construct narratives about what happened and explain why it happened. Some t ...

common misconceptions