Liberal Theory on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Liberalism is a

Locke also originated the concept of the

Locke also originated the concept of the

political

Politics () is the set of activities that are associated with decision-making, making decisions in social group, groups, or other forms of power (social and political), power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of Social sta ...

and moral philosophy

Ethics is the philosophical study of moral phenomena. Also called moral philosophy, it investigates normative questions about what people ought to do or which behavior is morally right. Its main branches include normative ethics, applied et ...

based on the rights of the individual, liberty

Liberty is the state of being free within society from oppressive restrictions imposed by authority on one's way of life, behavior, or political views. The concept of liberty can vary depending on perspective and context. In the Constitutional ...

, consent of the governed

In political philosophy, consent of the governed is the idea that a government's political legitimacy, legitimacy and natural and legal rights, moral right to use state power is justified and lawful only when consented to by the people or society o ...

, political equality

Politics () is the set of activities that are associated with making decisions in groups, or other forms of power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of status or resources.

The branch of social science that studies poli ...

, the right to private property, and equality before the law

Equality before the law, also known as equality under the law, equality in the eyes of the law, legal equality, or legal egalitarianism, is the principle that all people must be equally protected by the law. The principle requires a systematic ru ...

. Liberals espouse various and often mutually conflicting views depending on their understanding of these principles but generally support private property

Private property is a legal designation for the ownership of property by non-governmental Capacity (law), legal entities. Private property is distinguishable from public property, which is owned by a state entity, and from Collective ownership ...

, market economies

A market economy is an economic system in which the decisions regarding investment, production, and distribution to the consumers are guided by the price signals created by the forces of supply and demand. The major characteristic of a mark ...

, individual rights (including civil rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' political freedom, freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and ...

and human rights

Human rights are universally recognized Morality, moral principles or Social norm, norms that establish standards of human behavior and are often protected by both Municipal law, national and international laws. These rights are considered ...

), liberal democracy

Liberal democracy, also called Western-style democracy, or substantive democracy, is a form of government that combines the organization of a democracy with ideas of liberalism, liberal political philosophy. Common elements within a liberal dem ...

, secularism

Secularism is the principle of seeking to conduct human affairs based on naturalistic considerations, uninvolved with religion. It is most commonly thought of as the separation of religion from civil affairs and the state and may be broadened ...

, rule of law

The essence of the rule of law is that all people and institutions within a Body politic, political body are subject to the same laws. This concept is sometimes stated simply as "no one is above the law" or "all are equal before the law". Acco ...

, economic

An economy is an area of the Production (economics), production, Distribution (economics), distribution and trade, as well as Consumption (economics), consumption of Goods (economics), goods and Service (economics), services. In general, it is ...

and political freedom

Political freedom (also known as political autonomy or political agency) is a central concept in history and political thought and one of the most important features of democratic societies.Hannah Arendt, "What is Freedom?", ''Between Past and ...

, freedom of speech

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The rights, right to freedom of expression has been r ...

, freedom of the press

Freedom of the press or freedom of the media is the fundamental principle that communication and expression through various media, including printed and electronic Media (communication), media, especially publication, published materials, shoul ...

, freedom of assembly

Freedom of assembly, sometimes used interchangeably with the freedom of association, is the individual right or ability of individuals to peaceably assemble and collectively express, promote, pursue, and defend their ideas. The right to free ...

, and freedom of religion

Freedom of religion or religious liberty, also known as freedom of religion or belief (FoRB), is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or community, in public or private, to manifest religion or belief in teaching, practice ...

.Generally support:

*

*

*

*

*

*

*constitutional government

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organization or other type of entity, and commonly determines how that entity is to be governed.

When these princ ...

and privacy rights

The right to privacy is an element of various legal traditions that intends to restrain governmental and private actions that threaten the privacy of individuals. Over 185 national constitutions mention the right to privacy.

Since the global ...

*

Liberalism is frequently cited as the dominant ideology

An ideology is a set of beliefs or values attributed to a person or group of persons, especially those held for reasons that are not purely about belief in certain knowledge, in which "practical elements are as prominent as theoretical ones". Form ...

of modern history

The modern era or the modern period is considered the current historical period of human history. It was originally applied to the history of Europe and Western history for events that came after the Middle Ages, often from around the year 1500, ...

.Wolfe, p. 23.

Liberalism became a distinct movement in the Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment (also the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment) was a Europe, European Intellect, intellectual and Philosophy, philosophical movement active from the late 17th to early 19th century. Chiefly valuing knowledge gained th ...

, gaining popularity among Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

philosophers and economist

An economist is a professional and practitioner in the social sciences, social science discipline of economics.

The individual may also study, develop, and apply theories and concepts from economics and write about economic policy. Within this ...

s. Liberalism sought to replace the norms of hereditary privilege, state religion, absolute monarchy, the divine right of kings and traditional conservatism

Traditionalist conservatism, often known as classical conservatism, is a political philosophy, political and social philosophy that emphasizes the importance of transcendent moral principles, manifested through certain posited natural laws t ...

with representative democracy

Representative democracy, also known as indirect democracy or electoral democracy, is a type of democracy where elected delegates represent a group of people, in contrast to direct democracy. Nearly all modern Western-style democracies func ...

, rule of law, and equality under the law. Liberals also ended mercantilist

Mercantilism is a nationalist economic policy that is designed to maximize the exports and minimize the imports of an economy. It seeks to maximize the accumulation of resources within the country and use those resources for one-sided trade. ...

policies, royal monopolies, and other trade barrier

Trade barriers are government-induced restrictions on international trade. According to the comparative advantage, theory of comparative advantage, trade barriers are detrimental to the world economy and decrease overall economic efficiency.

Most ...

s, instead promoting free trade

Free trade is a trade policy that does not restrict imports or exports. In government, free trade is predominantly advocated by political parties that hold Economic liberalism, economically liberal positions, while economic nationalist politica ...

and marketization. The philosopher John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.) – 28 October 1704 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.)) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of the Enlightenment thi ...

is often credited with founding liberalism as a distinct tradition based on the ''social contract

In moral and political philosophy, the social contract is an idea, theory, or model that usually, although not always, concerns the legitimacy of the authority of the state over the individual. Conceptualized in the Age of Enlightenment, it ...

'', arguing that each man has a natural right

Some philosophers distinguish two types of rights, natural rights and legal rights.

* Natural rights are those that are not dependent on the laws or customs of any particular culture or government, and so are ''universal'', '' fundamental'' and ...

to life, liberty and property, and governments must not violate these rights

Rights are law, legal, social, or ethics, ethical principles of freedom or Entitlement (fair division), entitlement; that is, rights are the fundamental normative rules about what is allowed of people or owed to people according to some legal sy ...

. While the British liberal tradition emphasized expanding democracy, French liberalism emphasized rejecting authoritarianism

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political ''status quo'', and reductions in democracy, separation of powers, civil liberties, and ...

and is linked to nation-building

Nation-building is constructing or structuring a national identity using the power of the state. Nation-building aims at the unification of the people within the state so that it remains politically stable and viable. According to Harris Mylonas, ...

.Kirchner, p. 3.

Leaders in the British Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution, also known as the Revolution of 1688, was the deposition of James II and VII, James II and VII in November 1688. He was replaced by his daughter Mary II, Mary II and her Dutch husband, William III of Orange ...

of 1688, the American Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

of 1776, and the French Revolution of 1789 used liberal philosophy to justify the armed overthrow of royal sovereignty

Sovereignty can generally be defined as supreme authority. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within a state as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the person, body or institution that has the ultimate au ...

. The 19th century saw liberal governments established in Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

and South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a considerably smaller portion in the Northern Hemisphere. It can also be described as the southern Subregion#Americas, subregion o ...

, and it was well-established alongside republicanism in the United States

The values and ideals of republicanism are foundational in the constitution and history of the United States. As the United States constitution prohibits granting titles of nobility, ''republicanism'' in this context does not refer to a ...

. In Victorian Britain, it was used to critique the political establishment, appealing to science and reason on behalf of the people. During the 19th and early 20th centuries, liberalism in the Ottoman Empire and the Middle East

The Middle East (term originally coined in English language) is a geopolitical region encompassing the Arabian Peninsula, the Levant, Turkey, Egypt, Iran, and Iraq.

The term came into widespread usage by the United Kingdom and western Eur ...

influenced periods of reform, such as the Tanzimat

The (, , lit. 'Reorganization') was a period of liberal reforms in the Ottoman Empire that began with the Edict of Gülhane of 1839 and ended with the First Constitutional Era in 1876. Driven by reformist statesmen such as Mustafa Reşid Pash ...

and Al-Nahda, and the rise of constitutionalism

Constitutionalism is "a compound of ideas, attitudes, and patterns of behavior elaborating the principle that the authority of government derives from and is limited by a body of fundamental law".

Political organizations are constitutional to ...

, nationalism

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation, Smith, Anthony. ''Nationalism: Theory, I ...

, and secularism

Secularism is the principle of seeking to conduct human affairs based on naturalistic considerations, uninvolved with religion. It is most commonly thought of as the separation of religion from civil affairs and the state and may be broadened ...

. These changes, along with other factors, helped to create a sense of crisis within Islam

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

, which continues to this day, leading to Islamic revivalism

Islamic revival ('' '', lit., "regeneration, renewal"; also ', "Islamic awakening") refers to a revival of the Islamic religion, usually centered around enforcing sharia. A leader of a revival is known in Islam as a ''mujaddid''.

Within the Isl ...

. Before 1920, the main ideological opponents of liberalism were communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

, conservatism

Conservatism is a Philosophy of culture, cultural, Social philosophy, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, Convention (norm), customs, and Value (ethics and social science ...

, and socialism

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

; liberalism then faced major ideological challenges from fascism

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural social hie ...

and Marxism–Leninism

Marxism–Leninism () is a communist ideology that became the largest faction of the History of communism, communist movement in the world in the years following the October Revolution. It was the predominant ideology of most communist gov ...

as new opponents. During the 20th century, liberal ideas spread even further, especially in Western Europe, as liberal democracies found themselves as the winners in both world wars

A world war is an international conflict that involves most or all of the world's major powers. Conventionally, the term is reserved for two major international conflicts that occurred during the first half of the 20th century, World War I (19 ...

and the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

.

Liberals sought and established a constitutional order that prized important individual freedoms, such as freedom of speech

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The rights, right to freedom of expression has been r ...

and freedom of association

Freedom of association encompasses both an individual's right to join or leave groups voluntarily, the right of the group to take collective action to pursue the interests of its members, and the right of an association to accept or decline membe ...

; an independent judiciary

Judicial independence is the concept that the judiciary should be independent from the other branches of government. That is, courts should not be subject to improper influence from the other branches of government or from private or partisan inte ...

and public trial by jury

A jury trial, or trial by jury, is a legal proceeding in which a jury makes a decision or findings of fact. It is distinguished from a bench trial, in which a judge or panel of judges makes all decisions.

Jury trials are increasingly used ...

; and the abolition of aristocratic

Aristocracy (; ) is a form of government that places power in the hands of a small, privileged ruling class, the aristocrats.

Across Europe, the aristocracy exercised immense economic, political, and social influence. In Western Christian co ...

privileges. Later waves of modern liberal thought and struggle were strongly influenced by the need to expand civil rights.Worell, Judith. ''Encyclopedia of women and gender, Volume I''. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2001. Liberals have advocated gender and racial equality in their drive to promote civil rights, and global civil rights movements

Civil rights movements are a worldwide series of political movements for equality before the law, that peaked in the 1960s. In many situations they have been characterized by nonviolent protests, or have taken the form of campaigns of civil r ...

in the 20th century achieved several objectives towards both goals. Other goals often accepted by liberals include universal suffrage

Universal suffrage or universal franchise ensures the right to vote for as many people bound by a government's laws as possible, as supported by the " one person, one vote" principle. For many, the term universal suffrage assumes the exclusion ...

and universal access to education

Universal access to education is the ability of all people to have equal opportunity in education, regardless of their social class, race (human categorization), race, gender, sexuality, ethnicity, ethnic background or physical and mental disab ...

. In Europe and North America, the establishment of social liberalism

Social liberalism is a political philosophy and variety of liberalism that endorses social justice, social services, a mixed economy, and the expansion of civil and political rights, as opposed to classical liberalism which favors limited g ...

(often called simply ''liberalism'' in the United States) became a key component in expanding the welfare state

A welfare state is a form of government in which the State (polity), state (or a well-established network of social institutions) protects and promotes the economic and social well-being of its citizens, based upon the principles of equal oppor ...

. 21st-century liberal parties continue to wield power and influence throughout the world. The fundamental elements of contemporary society have liberal roots. The early waves of liberalism popularised economic individualism while expanding constitutional government and parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

ary authority.Gould, p. 3.

Definitions

Origins

'' Liberal'', ''liberty

Liberty is the state of being free within society from oppressive restrictions imposed by authority on one's way of life, behavior, or political views. The concept of liberty can vary depending on perspective and context. In the Constitutional ...

'', ''libertarian

Libertarianism (from ; or from ) is a political philosophy that holds freedom, personal sovereignty, and liberty as primary values. Many libertarians believe that the concept of freedom is in accord with the Non-Aggression Principle, according ...

'', and ''libertine

A libertine is a person questioning and challenging most moral principles, such as responsibility or Human sexual activity, sexual restraints, and will often declare these traits as unnecessary, undesirable or evil. A libertine is especially som ...

'' all trace their etymology

Etymology ( ) is the study of the origin and evolution of words—including their constituent units of sound and meaning—across time. In the 21st century a subfield within linguistics, etymology has become a more rigorously scientific study. ...

to ''liber

In Religion in ancient Rome, ancient Roman religion and Roman mythology, mythology, Liber ( , ; "the free one"), also known as Liber Pater ("the free Father"), was a god of viticulture and wine, male fertility and freedom. He was a patron de ...

'', a root

In vascular plants, the roots are the plant organ, organs of a plant that are modified to provide anchorage for the plant and take in water and nutrients into the plant body, which allows plants to grow taller and faster. They are most often bel ...

from Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

that means " free".Gross, p. 5. One of the first recorded instances of ''liberal'' occurred in 1375 when it was used to describe the liberal arts

Liberal arts education () is a traditional academic course in Western higher education. ''Liberal arts'' takes the term ''skill, art'' in the sense of a learned skill rather than specifically the fine arts. ''Liberal arts education'' can refe ...

in the context of an education desirable for a free-born man. The word's early connection with the classical education of a medieval university soon gave way to a proliferation of different denotations and connotations. ''Liberal'' could refer to "free in bestowing" as early as 1387, "made without stint" in 1433, "freely permitted" in 1530, and "free from restraint"—often as a pejorative remark—in the 16th and the 17th centuries.

In the 16th-century Kingdom of England

The Kingdom of England was a sovereign state on the island of Great Britain from the late 9th century, when it was unified from various Heptarchy, Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, until 1 May 1707, when it united with Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland to f ...

, ''liberal'' could have positive or negative attributes in referring to someone's generosity or indiscretion. In ''Much Ado About Nothing

''Much Ado About Nothing'' is a Shakespearean comedy, comedy by William Shakespeare thought to have been written in 1598 and 1599.See textual notes to ''Much Ado About Nothing'' in ''The Norton Shakespeare'' (W. W. Norton & Company, 1997 ) p. ...

'', William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

wrote of "a liberal villaine" who "hath ... confest his vile encounters". With the rise of the Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment (also the Age of Reason and the Enlightenment) was a European intellectual and philosophical movement active from the late 17th to early 19th century. Chiefly valuing knowledge gained through rationalism and empirici ...

, the word acquired decisively more positive undertones, defined as "free from narrow prejudice" in 1781 and "free from bigotry" in 1823. In 1815, the first use of ''liberalism'' appeared in English. In Spain, the '' liberales'', the first group to use the liberal label in a political context, fought for decades to implement the Spanish Constitution of 1812

The Political Constitution of the Spanish Monarchy (), also known as the Constitution of Cádiz () and nicknamed ''La Pepa'', was the first Constitution of Spain and one of the earliest codified constitutions in world history. The Constitution ...

. From 1820 to 1823, during the ''Trienio Liberal

The , () or Three Liberal Years, was a period of three years in Spain between 1820 and 1823 when a liberal government ruled Spain after a military uprising in January 1820 by the lieutenant-colonel Rafael del Riego against the absolutist rule ...

'', King Ferdinand VII

Ferdinand VII (; 14 October 1784 – 29 September 1833) was King of Spain during the early 19th century. He reigned briefly in 1808 and then again from 1813 to his death in 1833. Before 1813 he was known as ''el Deseado'' (the Desired), and af ...

was compelled by the ''liberales'' to swear to uphold the 1812 Constitution. By the middle of the 19th century, ''liberal'' was used as a politicised term for parties and movements worldwide.

Yellow

Yellow is the color between green and orange on the spectrum of light. It is evoked by light with a dominant wavelength of roughly 575585 nm. It is a primary color in subtractive color systems, used in painting or color printing. In t ...

is the political colour

Political colours are colours used to represent a political ideology, movement or party, either officially or unofficially. They represent the intersection of colour symbolism and political symbolism. Politicians making public appearances ...

most commonly associated with liberalism. The United States differs from other countries in that conservatism is associated with red and liberalism

Liberalism is a Political philosophy, political and moral philosophy based on the Individual rights, rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality, the right to private property, and equality before the law. ...

with blue.

Modern usage and definitions

In Europe and Latin America, ''liberalism'' means a moderate form ofclassical liberalism

Classical liberalism is a political tradition and a branch of liberalism that advocates free market and laissez-faire economics and civil liberties under the rule of law, with special emphasis on individual autonomy, limited governmen ...

and includes both conservative liberalism

Conservative liberalism, also referred to as right-liberalism, is a variant of liberalism combining liberal values and policies with conservative stances, or simply representing the right wing of the liberal movement. In the case of modern con ...

(centre-right

Centre-right politics is the set of right-wing politics, right-wing political ideologies that lean closer to the political centre. It is commonly associated with conservatism, Christian democracy, liberal conservatism, and conservative liberalis ...

liberalism) and social liberalism

Social liberalism is a political philosophy and variety of liberalism that endorses social justice, social services, a mixed economy, and the expansion of civil and political rights, as opposed to classical liberalism which favors limited g ...

(centre-left

Centre-left politics is the range of left-wing political ideologies that lean closer to the political centre. Ideologies commonly associated with it include social democracy, social liberalism, progressivism, and green politics. Ideas commo ...

liberalism). In North America, ''liberalism'' almost exclusively refers to social liberalism. The dominant Canadian party is the Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world.

The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left. For example, while the political systems ...

, and the Democratic Party is usually considered liberal in the United States. In the United States, conservative liberals are usually called ''conservatives'' in a broad sense.

Social liberalism

Over time, the meaning of ''liberalism'' began to diverge in different parts of the world. Since the 1930s, ''liberalism'' is usually used without a qualifier in the United States, to refer tosocial liberalism

Social liberalism is a political philosophy and variety of liberalism that endorses social justice, social services, a mixed economy, and the expansion of civil and political rights, as opposed to classical liberalism which favors limited g ...

, a variety of liberalism that endorses a regulated market

A regulated market (RM) or coordinated market is an idealized system where the government or other organizations oversee the market, control the forces of supply and demand, and to some extent regulate the market actions. This can include tasks s ...

economy and the expansion of civil and political rights

Civil and political rights are a class of rights that protect individuals' political freedom, freedom from infringement by governments, social organizations, and private individuals. They ensure one's entitlement to participate in the civil and ...

, with the common good considered as compatible with or superior to the freedom of the individual.

According to the ''Encyclopædia Britannica

The is a general knowledge, general-knowledge English-language encyclopaedia. It has been published by Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. since 1768, although the company has changed ownership seven times. The 2010 version of the 15th edition, ...

'', "In the United States, liberalism is associated with the welfare-state policies of the New Deal programme of the Democratic administration of Pres. Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

, whereas in Europe it is more commonly associated with a commitment to limited government

In political philosophy, limited government is the concept of a government limited in power. It is a key concept in the history of liberalism.Amy Gutmann, "How Limited Is Liberal Government" in Liberalism Without Illusions: Essays on Liberal ...

and ''laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( , from , ) is a type of economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies or regulations). As a system of thought, ''laissez-faire'' ...

'' economic policies." This variety of liberalism is also known as '' modern liberalism'' to distinguish it from ''classical liberalism'', which evolved into modern conservatism. In the United States, the two forms of liberalism comprise the two main poles of American politics, in the forms of '' modern American liberalism'' and '' modern American conservatism''.

Some liberals, who call themselves ''classical liberals'', ''fiscal conservatives

In American political theory, fiscal conservatism or economic conservatism is a political and economic philosophy regarding fiscal policy and fiscal responsibility with an ideological basis in capitalism, individualism, limited government, ...

'', or ''libertarians

Libertarianism (from ; or from ) is a political philosophy that holds freedom, personal sovereignty, and liberty as primary values. Many libertarians believe that the concept of freedom is in accord with the Non-Aggression Principle, according ...

'', endorse fundamental liberal ideals but diverge from modern liberal thought on the grounds that economic freedom is more important than social equality

Social equality is a state of affairs in which all individuals within society have equal rights, liberties, and status, possibly including civil rights, freedom of expression, autonomy, and equal access to certain public goods and social servi ...

. Consequently, the ideas of individualism

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology, and social outlook that emphasizes the intrinsic worth of the individual. Individualists promote realizing one's goals and desires, valuing independence and self-reliance, and a ...

and ''laissez-faire'' economics previously associated with classical liberalism

Classical liberalism is a political tradition and a branch of liberalism that advocates free market and laissez-faire economics and civil liberties under the rule of law, with special emphasis on individual autonomy, limited governmen ...

are key components of modern American conservatism

Conservatism in the United States is one of two major political ideologies in the United States, with the other being liberalism. Traditional American conservatism is characterized by a belief in individualism, traditionalism, capitalism, ...

and movement conservatism, and became the basis for the emerging school of modern American libertarian thought. In this American context, ''liberal'' is often used as a pejorative.

This political philosophy is exemplified by enactment of major social legislation and welfare programs. Two major examples in the United States are Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), also known as FDR, was the 32nd president of the United States, serving from 1933 until his death in 1945. He is the longest-serving U.S. president, and the only one to have served ...

's New Deal

The New Deal was a series of wide-reaching economic, social, and political reforms enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1938, in response to the Great Depression in the United States, Great Depressi ...

policies and later Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), also known as LBJ, was the 36th president of the United States, serving from 1963 to 1969. He became president after the assassination of John F. Kennedy, under whom he had served a ...

's Great Society

The Great Society was a series of domestic programs enacted by President Lyndon B. Johnson in the United States between 1964 and 1968, aimed at eliminating poverty, reducing racial injustice, and expanding social welfare in the country. Johnso ...

, as well as other accomplishments such as the Works Progress Administration

The Works Progress Administration (WPA; from 1935 to 1939, then known as the Work Projects Administration from 1939 to 1943) was an American New Deal agency that employed millions of jobseekers (mostly men who were not formally educated) to car ...

and the Social Security Act

The Social Security Act of 1935 is a law enacted by the 74th United States Congress and signed into law by U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt on August 14, 1935. The law created the Social Security (United States), Social Security program as ...

in 1935, as well as the Civil Rights Act of 1964

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 () is a landmark civil rights and United States labor law, labor law in the United States that outlaws discrimination based on Race (human categorization), race, Person of color, color, religion, sex, and nationa ...

and the Voting Rights Act of 1965

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 is a landmark piece of federal legislation in the United States that prohibits racial discrimination in voting. It was signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson during the height of the civil rights move ...

. Modern liberalism, in the United States and other major Western countries, now includes issues such as same-sex marriage

Same-sex marriage, also known as gay marriage, is the marriage of two people of the same legal Legal sex and gender, sex. marriage between same-sex couples is legally performed and recognized in 38 countries, with a total population of 1.5 ...

, transgender rights

The legal status of transgender people varies greatly around the world. Some countries have enacted laws protecting the rights of transgender individuals, but others have criminalized their gender identity or expression. In many cases, transg ...

, the abolition of capital punishment

Capital punishment, also known as the death penalty and formerly called judicial homicide, is the state-sanctioned killing of a person as punishment for actual or supposed misconduct. The sentence (law), sentence ordering that an offender b ...

, reproductive rights

Reproductive rights are legal rights and freedoms relating to human reproduction, reproduction and reproductive health that vary amongst countries around the world. The World Health Organization defines reproductive rights:

Reproductive rights ...

and other women's rights

Women's rights are the rights and Entitlement (fair division), entitlements claimed for women and girls worldwide. They formed the basis for the women's rights movement in the 19th century and the feminist movements during the 20th and 21st c ...

, voting rights

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise is the right to vote in representative democracy, public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in ...

for all adult citizens, civil rights, environmental justice

Environmental justice is a social movement that addresses injustice that occurs when poor or marginalized communities are harmed by hazardous waste, resource extraction, and other land uses from which they do not benefit. The movement has gene ...

, and government protection of the right to an adequate standard of living

The right to an adequate standard of living is listed as part of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights that was accepted by the General Assembly of the United Nations on December 10, 1948.United Nations''Universal Declaration of Human Rights ...

. National social services

Social services are a range of public services intended to provide support and assistance towards particular groups, which commonly include the disadvantaged. Also available amachine-converted HTML They may be provided by individuals, private and i ...

, such as equal educational opportunities, access to health care, and transportation infrastructure are intended to meet the responsibility to promote the general welfare of all citizens as established by the United States Constitution

The Constitution of the United States is the Supremacy Clause, supreme law of the United States, United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, on March 4, 1789. Originally includi ...

.

Classical liberalism

Classical liberalism is a political tradition and abranch

A branch, also called a ramus in botany, is a stem that grows off from another stem, or when structures like veins in leaves are divided into smaller veins.

History and etymology

In Old English, there are numerous words for branch, includ ...

of liberalism that advocates free market

In economics, a free market is an economic market (economics), system in which the prices of goods and services are determined by supply and demand expressed by sellers and buyers. Such markets, as modeled, operate without the intervention of ...

and laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( , from , ) is a type of economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies or regulations). As a system of thought, ''laissez-faire'' ...

economics and civil liberties

Civil liberties are guarantees and freedoms that governments commit not to abridge, either by constitution, legislation, or judicial interpretation, without due process. Though the scope of the term differs between countries, civil liberties of ...

under the rule of law

The essence of the rule of law is that all people and institutions within a Body politic, political body are subject to the same laws. This concept is sometimes stated simply as "no one is above the law" or "all are equal before the law". Acco ...

, with special emphasis on individual autonomy, limited government

In political philosophy, limited government is the concept of a government limited in power. It is a key concept in the history of liberalism.Amy Gutmann, "How Limited Is Liberal Government" in Liberalism Without Illusions: Essays on Liberal ...

, economic freedom, political freedom

Political freedom (also known as political autonomy or political agency) is a central concept in history and political thought and one of the most important features of democratic societies.Hannah Arendt, "What is Freedom?", ''Between Past and ...

and freedom of speech

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The rights, right to freedom of expression has been r ...

. Classical liberalism, contrary to liberal branches like social liberalism

Social liberalism is a political philosophy and variety of liberalism that endorses social justice, social services, a mixed economy, and the expansion of civil and political rights, as opposed to classical liberalism which favors limited g ...

, looks more negatively on social policies

Some professionals and universities consider social policy a subset of public policy, while other practitioners characterize social policy and public policy to be two separate, competing approaches for the same public interest (similar to Compar ...

, tax

A tax is a mandatory financial charge or levy imposed on an individual or legal entity by a governmental organization to support government spending and public expenditures collectively or to regulate and reduce negative externalities. Tax co ...

ation and the state involvement in the lives of individuals, and it advocates deregulation

Deregulation is the process of removing or reducing state regulations, typically in the economic sphere. It is the repeal of governmental regulation of the economy. It became common in advanced industrial economies in the 1970s and 1980s, as a ...

.

In the context of current American politics of the present day, ''classical liberalism'' may be described as "fiscally conservative" and "socially liberal". Despite this, classical liberals tend to reject the right's higher tolerance for economic protectionism and the left's inclination for collective group rights

Individual rights, also known as natural rights, are rights held by individuals by virtue of being human. Some theists believe individual rights are bestowed by God. An individual right is a moral claim to freedom of action.

Group rights, also k ...

due to classical liberalism's central principle of individualism

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology, and social outlook that emphasizes the intrinsic worth of the individual. Individualists promote realizing one's goals and desires, valuing independence and self-reliance, and a ...

. Additionally, in the United States ''classical liberalism'' is considered closely tied to, or synonymous with, American libertarianism.

Until the Great Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

and the rise of social liberalism, classical liberalism was called economic liberalism

Economic liberalism is a political and economic ideology that supports a market economy based on individualism and private property in the means of production. Adam Smith is considered one of the primary initial writers on economic liberalism ...

. Later, the term was applied as a retronym

A retronym is a newer name for something that differentiates it from something else that is newer, similar, or seen in everyday life; thus, avoiding confusion between the two.

Etymology

The term ''retronym'', a neologism composed of the combi ...

, to distinguish earlier 19th-century liberalism from social liberalism. By modern standards, in the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

the bare term ''liberalism'' often means social liberalism whereas in Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

and Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising mainland Australia, the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and list of islands of Australia, numerous smaller isl ...

it often means classical liberalism.

Classical liberalism gained full flowering in the early 18th century, building on ideas dating at least as far back as the 16th century, within the Iberian, British, and Central European contexts, and it was foundational to the American Revolution

The American Revolution (1765–1783) was a colonial rebellion and war of independence in which the Thirteen Colonies broke from British America, British rule to form the United States of America. The revolution culminated in the American ...

and "American Project" more broadly. Notable liberal individuals whose ideas contributed to classical liberalism include John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.) – 28 October 1704 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.)) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of the Enlightenment thi ...

,Steven M. Dworetz (1994). ''The Unvarnished Doctrine: Locke, Liberalism, and the American Revolution''. Jean-Baptiste Say

Jean-Baptiste () is a male French name, originating with Saint John the Baptist, and sometimes shortened to Baptiste. The name may refer to any of the following:

Persons

* Charles XIV John of Sweden, born Jean-Baptiste Jules Bernadotte, was K ...

, Thomas Malthus

Thomas Robert Malthus (; 13/14 February 1766 – 29 December 1834) was an English economist, cleric, and scholar influential in the fields of political economy and demography.

In his 1798 book ''An Essay on the Principle of Population'', Mal ...

, and David Ricardo

David Ricardo (18 April 1772 – 11 September 1823) was a British political economist, politician, and member of Parliament. He is recognized as one of the most influential classical economists, alongside figures such as Thomas Malthus, Ada ...

. It drew on classical economics

Classical economics, also known as the classical school of economics, or classical political economy, is a school of thought in political economy that flourished, primarily in Britain, in the late 18th and early-to-mid 19th century. It includ ...

, especially the economic ideas espoused by Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptised 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the field of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as the "father of economics"——— or ...

in Book One of ''The Wealth of Nations

''An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations'', usually referred to by its shortened title ''The Wealth of Nations'', is a book by the Scottish people, Scottish economist and moral philosophy, moral philosopher Adam Smith; ...

'', and on a belief in natural law

Natural law (, ) is a Philosophy, philosophical and legal theory that posits the existence of a set of inherent laws derived from nature and universal moral principles, which are discoverable through reason. In ethics, natural law theory asserts ...

. In contemporary times, Friedrich Hayek

Friedrich August von Hayek (8 May 1899 – 23 March 1992) was an Austrian-born British academic and philosopher. He is known for his contributions to political economy, political philosophy and intellectual history. Hayek shared the 1974 Nobe ...

, Milton Friedman

Milton Friedman (; July 31, 1912 – November 16, 2006) was an American economist and statistician who received the 1976 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for his research on consumption analysis, monetary history and theory and ...

, Ludwig von Mises

Ludwig Heinrich Edler von Mises (; ; September 29, 1881 – October 10, 1973) was an Austrian-American political economist and philosopher of the Austrian school. Mises wrote and lectured extensively on the social contributions of classical l ...

, Thomas Sowell

Thomas Sowell ( ; born June 30, 1930) is an American economist, economic historian, and social and political commentator. He is a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution. With widely published commentary and books—and as a guest on T ...

, George Stigler

George Joseph Stigler (; January 17, 1911 – December 1, 1991) was an American economist. He was the 1982 laureate in Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences and is considered a key leader of the Chicago school of economics.

Early life and e ...

, Larry Arnhart, Ronald Coase

Ronald Harry Coase (; 29 December 1910 – 2 September 2013) was a British economist and author. Coase was educated at the London School of Economics, where he was a member of the faculty until 1951. He was the Clifton R. Musser Professor of Eco ...

and James M. Buchanan are seen as the most prominent advocates of classical liberalism; however, other scholars have made reference to these contemporary thoughts as '' neoclassical liberalism'', distinguishing them from 18th-century classical liberalism.Mayne, Alan James (1999). ''From Politics Past to Politics Future: An Integrated Analysis of Current and Emergent Paradigmss''. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 124–125. .

Philosophy

Liberalism—both as a political current and an intellectual tradition—is mostly a modern phenomenon that started in the 17th century, although some liberal philosophical ideas had precursors inclassical antiquity

Classical antiquity, also known as the classical era, classical period, classical age, or simply antiquity, is the period of cultural History of Europe, European history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD comprising the inter ...

and Imperial China

The history of China spans several millennia across a wide geographical area. Each region now considered part of the Chinese world has experienced periods of unity, fracture, prosperity, and strife. Chinese civilization first emerged in the Y ...

. The Roman Emperor Marcus Aurelius

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus ( ; ; 26 April 121 – 17 March 180) was Roman emperor from 161 to 180 and a Stoicism, Stoic philosopher. He was a member of the Nerva–Antonine dynasty, the last of the rulers later known as the Five Good Emperors ...

praised "the idea of a polity administered with regard to equal rights and equal freedom of speech, and the idea of a kingly government which respects most of all the freedom of the governed". Scholars have also recognised many principles familiar to contemporary liberals in the works of several Sophists

A sophist () was a teacher in ancient Greece in the fifth and fourth centuries BCE. Sophists specialized in one or more subject areas, such as philosophy, rhetoric, music, athletics and mathematics. They taught ''arete'', "virtue" or "excellen ...

and the ''Funeral Oration'' by Pericles

Pericles (; ; –429 BC) was a Greek statesman and general during the Golden Age of Athens. He was prominent and influential in Ancient Athenian politics, particularly between the Greco-Persian Wars and the Peloponnesian War, and was acclaimed ...

.. Liberal philosophy is the culmination of an extensive intellectual tradition that has examined and popularized some of the modern world's most important and controversial principles. Its immense scholarly output has been characterized as containing "richness and diversity", but that diversity often has meant that liberalism comes in different formulations and presents a challenge to anyone looking for a clear definition..

Major themes

Although all liberal doctrines possess a common heritage, scholars frequently assume that those doctrines contain "separate and often contradictory streams of thought". The objectives of liberal theorists and philosophers have differed across various times, cultures and continents. The diversity of liberalism can be gleaned from the numerous qualifiers that liberal thinkers and movements have attached to the term "liberalism", including classical,egalitarian

Egalitarianism (; also equalitarianism) is a school of thought within political philosophy that builds on the concept of social equality, prioritizing it for all people. Egalitarian doctrines are generally characterized by the idea that all h ...

, economic

An economy is an area of the Production (economics), production, Distribution (economics), distribution and trade, as well as Consumption (economics), consumption of Goods (economics), goods and Service (economics), services. In general, it is ...

, social

Social organisms, including human(s), live collectively in interacting populations. This interaction is considered social whether they are aware of it or not, and whether the exchange is voluntary or not.

Etymology

The word "social" derives fro ...

, the welfare state

A welfare state is a form of government in which the State (polity), state (or a well-established network of social institutions) protects and promotes the economic and social well-being of its citizens, based upon the principles of equal oppor ...

, ethical

Ethics is the philosophical study of moral phenomena. Also called moral philosophy, it investigates normative questions about what people ought to do or which behavior is morally right. Its main branches include normative ethics, applied e ...

, humanist

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential, and agency of human beings, whom it considers the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "humanism" ha ...

, deontological

In moral philosophy, deontological ethics or deontology (from Greek language, Greek: and ) is the normative ethics, normative ethical theory that the morality of an action should be based on whether that action itself is right or wrong under a ...

, perfectionist, democratic, and institution

An institution is a humanly devised structure of rules and norms that shape and constrain social behavior. All definitions of institutions generally entail that there is a level of persistence and continuity. Laws, rules, social conventions and ...

al, to name a few. Despite these variations, liberal thought does exhibit a few definite and fundamental conceptions.

Political philosopher John Gray identified the common strands in liberal thought as individualist

Individualism is the moral stance, political philosophy, ideology, and social outlook that emphasizes the intrinsic worth of the individual. Individualists promote realizing one's goals and desires, valuing independence and self-reliance, and a ...

, egalitarian, meliorist and universalist. The individualist element avers the ethical primacy of the human being against the pressures of social collectivism

In sociology, a social organization is a pattern of relationships between and among individuals and groups. Characteristics of social organization can include qualities such as sexual composition, spatiotemporal cohesion, leadership, struct ...

; the egalitarian element assigns the same moral

A moral (from Latin ''morālis'') is a message that is conveyed or a lesson to be learned from a story or event. The moral may be left to the hearer, reader, or viewer to determine for themselves, or may be explicitly encapsulated in a maxim. ...

worth and status to all individuals; the meliorist element asserts that successive generations can improve their sociopolitical arrangements, and the universalist element affirms the moral unity of the human species and marginalises local cultural

Culture ( ) is a concept that encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and Social norm, norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, Social norm, customs, capabilities, Attitude (psychology), attitudes ...

differences.Gray, p. xii. The meliorist element has been the subject of much controversy, defended by thinkers such as Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (born Emanuel Kant; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German Philosophy, philosopher and one of the central Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works ...

, who believed in human progress, while suffering criticism by thinkers such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Republic of Geneva, Genevan philosopher (''philosophes, philosophe''), writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment through ...

, who instead believed that human attempts to improve themselves through social cooperation

Cooperation (written as co-operation in British English and, with a varied usage along time, coöperation) takes place when a group of organisms works or acts together for a collective benefit to the group as opposed to working in competition ...

would fail.

The liberal philosophical tradition has searched for validation and justification through several intellectual projects. The moral and political suppositions of liberalism have been based on traditions such as natural rights and utilitarian theory, although sometimes liberals even request support from scientific and religious circles. Through all these strands and traditions, scholars have identified the following major common facets of liberal thought:

* believing in equality and individual liberty

Civil liberties are guarantees and freedoms that governments commit not to abridge, either by constitution, legislation, or judicial interpretation, without due process. Though the scope of the term differs between countries, civil liberties of ...

* supporting private property and individual rights

* supporting the idea of limited constitutional government

* recognising the importance of related values such as pluralism, toleration

Toleration is when one allows or permits an action, idea, object, or person that they dislike or disagree with. Political scientist Andrew R. Murphy explains that "We can improve our understanding by defining 'toleration' as a set of social or ...

, autonomy, bodily integrity

Bodily integrity is the inviolability of the physical body and emphasizes the importance of personal autonomy, self-ownership, and self-determination of human beings over their own bodies. In the field of human rights, violation of the bodily int ...

, and consent

Consent occurs when one person voluntarily agrees to the proposal or desires of another. It is a term of common speech, with specific definitions used in such fields as the law, medicine, research, and sexual consent. Consent as understood i ...

Classical and modern

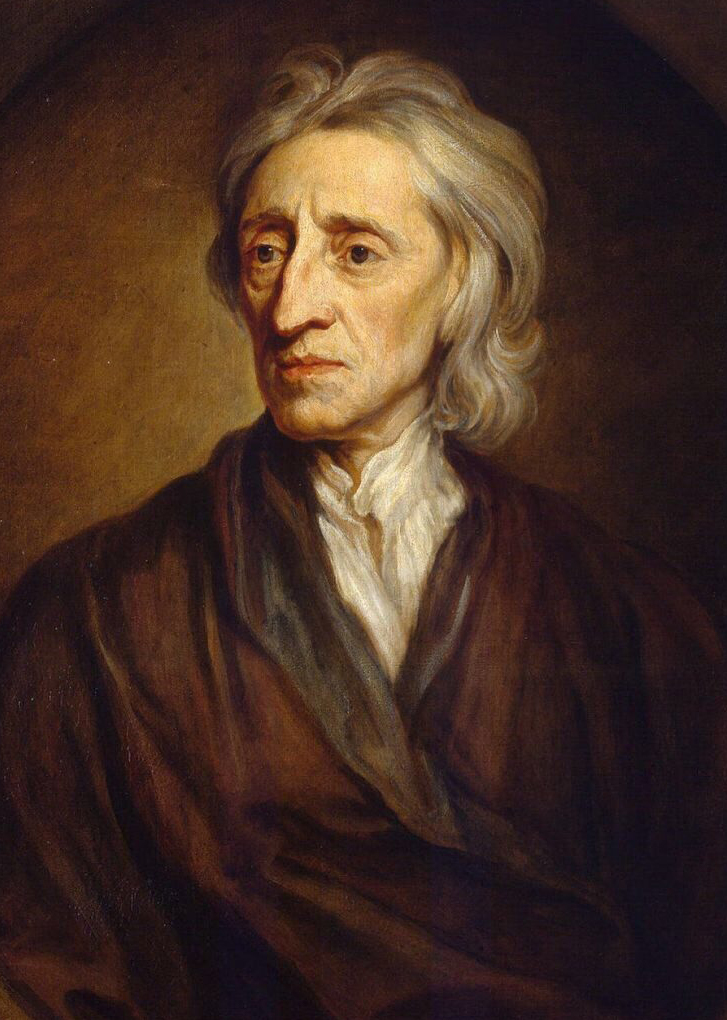

John Locke and Thomas Hobbes

Enlightenment philosophers are given credit for shaping liberal ideas. These ideas were first drawn together and systematized as a distinctideology

An ideology is a set of beliefs or values attributed to a person or group of persons, especially those held for reasons that are not purely about belief in certain knowledge, in which "practical elements are as prominent as theoretical ones". Form ...

by the English philosopher John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.) – 28 October 1704 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.)) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of the Enlightenment thi ...

, generally regarded as the father of modern liberalism.Taverne, p. 18.Godwin et al., p. 12. Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes ( ; 5 April 1588 – 4 December 1679) was an English philosopher, best known for his 1651 book ''Leviathan (Hobbes book), Leviathan'', in which he expounds an influential formulation of social contract theory. He is considered t ...

attempted to determine the purpose and the justification of governing authority in post-civil war England. Employing the idea of a ''state of nature

In ethics, political philosophy, social contract theory, religion, and international law, the term state of nature describes the hypothetical way of life that existed before humans organised themselves into societies or civilisations. Philosoph ...

'' — a hypothetical war-like scenario prior to the state — he constructed the idea of a ''social contract

In moral and political philosophy, the social contract is an idea, theory, or model that usually, although not always, concerns the legitimacy of the authority of the state over the individual. Conceptualized in the Age of Enlightenment, it ...

'' that individuals enter into to guarantee their security and, in so doing, form the State, concluding that only an absolute sovereign would be fully able to sustain such security. Hobbes had developed the concept of the social contract, according to which individuals in the anarchic and brutal state of nature came together and voluntarily ceded some of their rights to an established state authority, which would create laws to regulate social interactions to mitigate or mediate conflicts and enforce justice. Whereas Hobbes advocated a strong monarchical commonwealth (the Leviathan

Leviathan ( ; ; ) is a sea serpent demon noted in theology and mythology. It is referenced in several books of the Hebrew Bible, including Psalms, the Book of Job, the Book of Isaiah, and the pseudepigraphical Book of Enoch. Leviathan is of ...

), Locke developed the then-radical notion that government acquires consent from the governed, which has to be constantly present for the government to remain legitimate. While adopting Hobbes's idea of a state of nature and social contract, Locke nevertheless argued that when the monarch becomes a tyrant

A tyrant (), in the modern English usage of the word, is an absolute ruler who is unrestrained by law, or one who has usurped a legitimate ruler's sovereignty. Often portrayed as cruel, tyrants may defend their positions by resorting to ...

, it violates the social contract, which protects life, liberty and property as a natural right. He concluded that the people have a right to overthrow a tyrant. By placing the security of life, liberty and property as the supreme value of law and authority, Locke formulated the basis of liberalism based on social contract theory. To these early enlightenment thinkers, securing the essential amenities of life—liberty

Liberty is the state of being free within society from oppressive restrictions imposed by authority on one's way of life, behavior, or political views. The concept of liberty can vary depending on perspective and context. In the Constitutional ...

and private property

Private property is a legal designation for the ownership of property by non-governmental Capacity (law), legal entities. Private property is distinguishable from public property, which is owned by a state entity, and from Collective ownership ...

—required forming a "sovereign" authority with universal jurisdiction.

His influential '' Two Treatises'' (1690), the foundational text of liberal ideology, outlined his major ideas. Once humans moved out of their natural state and formed societies

A society () is a group of individuals involved in persistent social interaction or a large social group sharing the same spatial or social territory, typically subject to the same political authority and dominant cultural expectations. ...

, Locke argued, "that which begins and actually constitutes any political society is nothing but the consent of any number of freemen capable of a majority to unite and incorporate into such a society. And this is that, and that only, which did or could give beginning to any lawful government in the world". The stringent insistence that lawful government did not have a supernatural

Supernatural phenomena or entities are those beyond the Scientific law, laws of nature. The term is derived from Medieval Latin , from Latin 'above, beyond, outside of' + 'nature'. Although the corollary term "nature" has had multiple meanin ...

basis was a sharp break with the dominant theories of governance, which advocated the divine right of kings and echoed the earlier thought of Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

. Dr John Zvesper described this new thinking: "In the liberal understanding, there are no citizens within the regime who can claim to rule by natural or supernatural right, without the consent of the governed".

Locke had other intellectual opponents besides Hobbes. In the ''First Treatise'', Locke aimed his arguments first and foremost at one of the doyens of 17th-century English conservative philosophy: Robert Filmer

Sir Robert Filmer (c. 1588 – 26 May 1653) was an English political theorist who defended the divine right of kings. His best known work, '' Patriarcha'', published posthumously in 1680, was the target of numerous Whig attempts at rebuttal ...

. Filmer's ''Patriarcha'' (1680) argued for the divine right of kings by appealing to biblical

The Bible is a collection of religious texts that are central to Christianity and Judaism, and esteemed in other Abrahamic religions such as Islam. The Bible is an anthology (a compilation of texts of a variety of forms) biblical languages ...

teaching, claiming that the authority granted to Adam

Adam is the name given in Genesis 1–5 to the first human. Adam is the first human-being aware of God, and features as such in various belief systems (including Judaism, Christianity, Gnosticism and Islam).

According to Christianity, Adam ...

by God

In monotheistic belief systems, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. In polytheistic belief systems, a god is "a spirit or being believed to have created, or for controlling some part of the un ...

gave successors of Adam in the male line of descent a right of dominion over all other humans and creatures in the world. However, Locke disagreed so thoroughly and obsessively with Filmer that the ''First Treatise'' is almost a sentence-by-sentence refutation of ''Patriarcha''. Reinforcing his respect for consensus, Locke argued that "conjugal society is made up by a voluntary compact between men and women". Locke maintained that the grant of dominion in Genesis

Genesis may refer to:

Religion

* Book of Genesis, the first book of the biblical scriptures of both Judaism and Christianity, describing the creation of the Earth and of humankind

* Genesis creation narrative, the first several chapters of the Bo ...

was not to men over women, as Filmer believed, but to humans over animals. Locke was not a feminist

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideology, ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social gender equality, equality of the sexes. Feminism holds the position that modern soci ...

by modern standards, but the first major liberal thinker in history accomplished an equally major task on the road to making the world more pluralistic: integrating women into social theory

Social theories are analytical frameworks, or paradigms, that are used to study and interpret social phenomena.Seidman, S., 2016. Contested knowledge: Social theory today. John Wiley & Sons. A tool used by social scientists, social theories re ...

.

Locke also originated the concept of the

Locke also originated the concept of the separation of church and state

The separation of church and state is a philosophical and Jurisprudence, jurisprudential concept for defining political distance in the relationship between religious organizations and the State (polity), state. Conceptually, the term refers to ...

.Feldman, Noah (2005). ''Divided by God''. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, p. 29 ("It took John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.) – 28 October 1704 (Old Style and New Style dates, O.S.)) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of the Enlightenment thi ...

to translate the demand for liberty of conscience into a systematic argument for distinguishing the realm of government from the realm of religion.") Based on the social contract principle, Locke argued that the government lacked authority in the realm of individual conscience

A conscience is a Cognition, cognitive process that elicits emotion and rational associations based on an individual's ethics, moral philosophy or value system. Conscience is not an elicited emotion or thought produced by associations based on i ...

, as this was something rational

Rationality is the quality of being guided by or based on reason. In this regard, a person acts rationally if they have a good reason for what they do, or a belief is rational if it is based on strong evidence. This quality can apply to an ...

people could not cede to the government for it or others to control. For Locke, this created a natural right to the liberty of conscience, which he argued must remain protected from any government authority. In his ''Letters Concerning Toleration'', he also formulated a general defence for religious toleration

Religious tolerance or religious toleration may signify "no more than forbearance and the permission given by the adherents of a dominant religion for other religions to exist, even though the latter are looked on with disapproval as inferior, ...

. Three arguments are central:

# Earthly judges, the state in particular, and human beings generally, cannot dependably evaluate the truth claims of competing religious standpoints;

# Even if they could, enforcing a single " true religion" would not have the desired effect because belief cannot be compelled by violence

Violence is characterized as the use of physical force by humans to cause harm to other living beings, or property, such as pain, injury, disablement, death, damage and destruction. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines violence a ...

;

# Coercing religious uniformity would lead to more social disorder than allowing diversity.

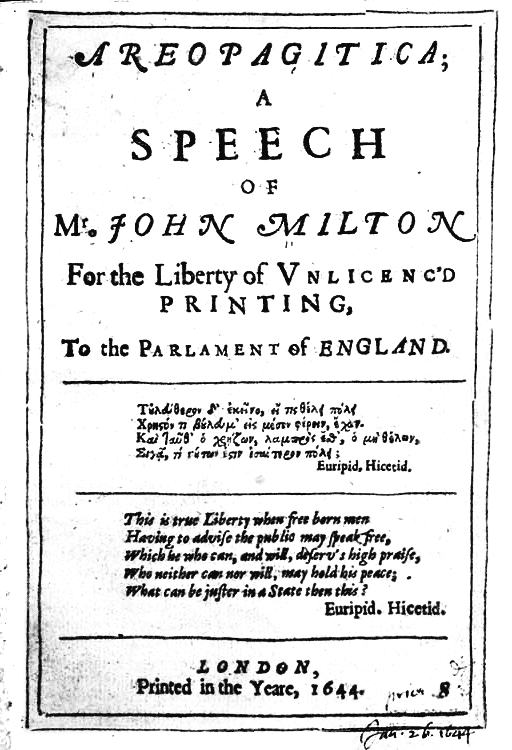

Locke was influenced by the liberal ideas of Presbyterian politician and poet John Milton

John Milton (9 December 1608 – 8 November 1674) was an English poet, polemicist, and civil servant. His 1667 epic poem ''Paradise Lost'' was written in blank verse and included 12 books, written in a time of immense religious flux and politic ...

, who was a staunch advocate of freedom in all its forms. Milton argued for disestablishment

The separation of church and state is a philosophical and jurisprudential concept for defining political distance in the relationship between religious organizations and the state. Conceptually, the term refers to the creation of a secular s ...

as the only effective way of achieving broad toleration

Toleration is when one allows or permits an action, idea, object, or person that they dislike or disagree with. Political scientist Andrew R. Murphy explains that "We can improve our understanding by defining 'toleration' as a set of social or ...

. Rather than force a man's conscience, the government should recognise the persuasive force of the gospel. As assistant to Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English statesman, politician and soldier, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in British history. He came to prominence during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, initially ...

, Milton also drafted a constitution of the independents (''Agreement of the People''; 1647) that strongly stressed the equality of all humans as a consequence of democratic tendencies. In his '' Areopagitica'', Milton provided one of the first arguments for the importance of freedom of speech—"the liberty to know, to utter, and to argue freely according to conscience, above all liberties". His central argument was that the individual could use reason to distinguish right from wrong. To exercise this right, everyone must have unlimited access to the ideas of his fellow men in " a free and open encounter", which will allow good arguments to prevail.

In a natural state of affairs, liberals argued that humans were driven by the instincts of survival and self-preservation

Self-preservation is a behavior or set of behaviors that ensures the survival of an organism. It is thought to be universal among all living organisms.

Self-preservation is essentially the process of an organism preventing itself from being harm ...

, and the only way to escape from such a dangerous existence was to form a common and supreme power capable of arbitrating between competing human desires.. This power could be formed in the framework of a civil society

Civil society can be understood as the "third sector" of society, distinct from government and business, and including the family and the private sphere. These early liberals often disagreed about the most appropriate form of government, but all believed that liberty was natural and its restriction needed strong justification. Liberals generally believed in limited government, although several liberal philosophers decried government outright, with

Beginning in the late 19th century, a new conception of liberty entered the liberal intellectual arena. This new kind of liberty became known as

Beginning in the late 19th century, a new conception of liberty entered the liberal intellectual arena. This new kind of liberty became known as

Thomas Paine

Thomas Paine (born Thomas Pain; – In the contemporary record as noted by Conway, Paine's birth date is given as January 29, 1736–37. Common practice was to use a dash or a slash to separate the old-style year from the new-style year. In ...

writing, "Government even in its best state is a necessary evil.".

James Madison and Montesquieu

As part of the project to limit the powers of government, liberal theorists such asJames Madison

James Madison (June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison was popularly acclaimed as the ...

and Montesquieu

Charles Louis de Secondat, baron de La Brède et de Montesquieu (18 January 168910 February 1755), generally referred to as simply Montesquieu, was a French judge, man of letters, historian, and political philosopher.

He is the principal so ...

conceived the notion of separation of powers

The separation of powers principle functionally differentiates several types of state (polity), state power (usually Legislature#Legislation, law-making, adjudication, and Executive (government)#Function, execution) and requires these operat ...

, a system designed to equally distribute governmental authority among the executive

Executive ( exe., exec., execu.) may refer to:

Role or title

* Executive, a senior management role in an organization

** Chief executive officer (CEO), one of the highest-ranking corporate officers (executives) or administrators

** Executive dir ...