Lex Salica on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Salic law ( or ; ), also called the was the ancient Frankish civil law code compiled around AD 500 by Clovis, the first

The original edition of the code was commissioned by the first king of all the Franks,

The original edition of the code was commissioned by the first king of all the Franks,

* Old Dutch and Early Modern and earlier versions of English used the second-person singular pronouns, such as ''thou'' and ''thee''.

:** A ''lito'' was a form of

Several military conflicts in European history have stemmed from the application of, or disregard for, Salic law. The Carlist Wars occurred in

Several military conflicts in European history have stemmed from the application of, or disregard for, Salic law. The Carlist Wars occurred in

Information on the ''Salic law'' and its manuscript tradition on the ' website

A database on Carolingian secular law texts (Karl Ubl, Cologne University, Germany). {{Authority control Prose texts in Latin Law of France Old Dutch Earliest known manuscripts by language 6th-century books in Latin 6th century in Francia 6th century in law 6th-century Frankish writers 6th-century jurists Succession acts Germanic legal codes

Frankish King

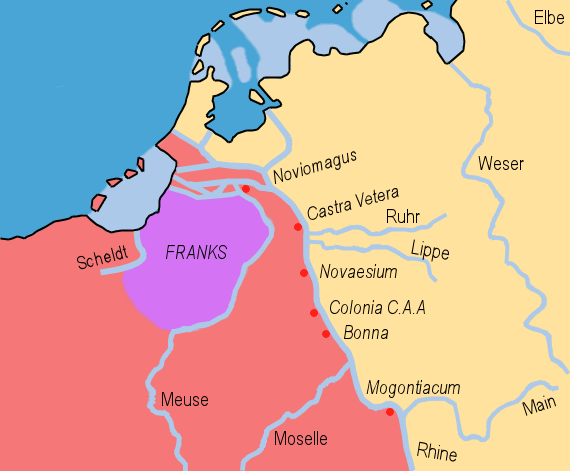

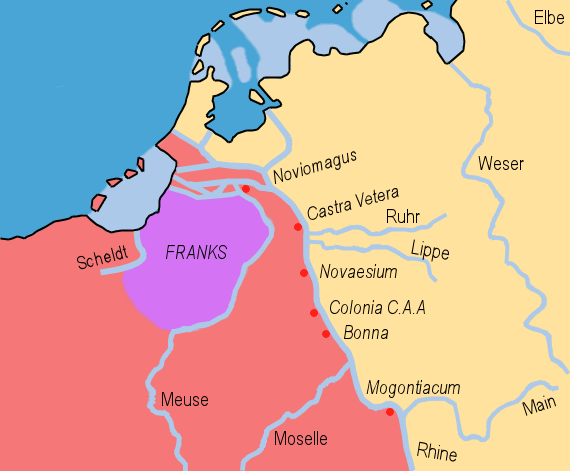

The Franks, Germanic peoples that invaded the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century, were first led by individuals called dux, dukes and monarch, reguli. The earliest group of Franks that rose to prominence was the Salian Franks, Salian Mero ...

. The name may refer to the Salii, or "Salian Franks

The Salian Franks, or Salians, sometimes referred to using the Latin word or , were a Frankish people who lived in what was is now the Netherlands in the fourth century. They are only mentioned under this name in historical records relating to ...

", but this is debated. The written text is in Late Latin

Late Latin is the scholarly name for the form of Literary Latin of late antiquity.Roberts (1996), p. 537. English dictionary definitions of Late Latin date this period from the 3rd to 6th centuries CE, and continuing into the 7th century in ...

, and contains some of the earliest known instances of Old Dutch

In linguistics, Old Dutch ( Modern Dutch: ') or Old Low Franconian (Modern Dutch: ') is the set of dialects that evolved from Frankish spoken in the Low Countries during the Early Middle Ages, from around the 6th Page 55: "''Uit de zesde eeu ...

. It remained the basis of Frankish law throughout the early Medieval period

The Early Middle Ages (or early medieval period), sometimes controversially referred to as the Dark Ages, is typically regarded by historians as lasting from the late 5th to the 10th century. They marked the start of the Middle Ages of Europe ...

, and influenced future European legal systems. The best-known tenet of the old law is the principle of exclusion of women from inheritance of thrones, fiefs, and other property. The Salic laws were arbitrated by a committee appointed and empowered by the King of the Franks

The Franks, Germanic peoples that invaded the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century, were first led by individuals called dux, dukes and monarch, reguli. The earliest group of Franks that rose to prominence was the Salian Franks, Salian Mero ...

. Dozens of manuscripts dating from the sixth to eighth centuries and three emendations as late as the ninth century have survived.

Salic law provided written codification of both civil law, such as the statutes governing inheritance

Inheritance is the practice of receiving private property, titles, debts, entitlements, privileges, rights, and obligations upon the death of an individual. The rules of inheritance differ among societies and have changed over time. Offi ...

, and criminal law

Criminal law is the body of law that relates to crime. It proscribes conduct perceived as threatening, harmful, or otherwise endangering to the property, health, safety, and Well-being, welfare of people inclusive of one's self. Most criminal l ...

, such as the punishment for murder

Murder is the unlawful killing of another human without justification (jurisprudence), justification or valid excuse (legal), excuse committed with the necessary Intention (criminal law), intention as defined by the law in a specific jurisd ...

. Although it was originally intended as the law of the Franks

file:Frankish arms.JPG, Aristocratic Frankish burial items from the Merovingian dynasty

The Franks ( or ; ; ) were originally a group of Germanic peoples who lived near the Rhine river, Rhine-river military border of Germania Inferior, which wa ...

, it has had a formative influence on the tradition of statute law

A statute is a law or formal written enactment of a legislature. Statutes typically declare, command or prohibit something. Statutes are distinguished from court law and unwritten law (also known as common law) in that they are the expressed wil ...

that extended to modern history

The modern era or the modern period is considered the current historical period of human history. It was originally applied to the history of Europe and Western history for events that came after the Middle Ages, often from around the year 1500, ...

in much of Europe, especially in the German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

states and Austria-Hungary

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe#Before World War I, Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military ...

in Central Europe

Central Europe is a geographical region of Europe between Eastern Europe, Eastern, Southern Europe, Southern, Western Europe, Western and Northern Europe, Northern Europe. Central Europe is known for its cultural diversity; however, countries in ...

, the Low Countries

The Low Countries (; ), historically also known as the Netherlands (), is a coastal lowland region in Northwestern Europe forming the lower Drainage basin, basin of the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta and consisting today of the three modern "Bene ...

in Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's extent varies depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the Western half of the ancient Mediterranean ...

, Balkan

The Balkans ( , ), corresponding partially with the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throug ...

kingdoms in Southeastern Europe

Southeast Europe or Southeastern Europe is a geographical sub-region of Europe, consisting primarily of the region of the Balkans, as well as adjacent regions and Archipelago, archipelagos. There are overlapping and conflicting definitions of t ...

, and parts of Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

and Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

in Southern Europe

Southern Europe is also known as Mediterranean Europe, as its geography is marked by the Mediterranean Sea. Definitions of southern Europe include some or all of these countries and regions: Albania, Andorra, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, C ...

. Its use of agnatic succession governed the succession of kings in kingdoms such as France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

and Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

.

History of the law

The original edition of the code was commissioned by the first king of all the Franks,

The original edition of the code was commissioned by the first king of all the Franks, Clovis I

Clovis (; reconstructed Old Frankish, Frankish: ; – 27 November 511) was the first List of Frankish kings, king of the Franks to unite all of the Franks under one ruler, changing the form of leadership from a group of petty kings to rule by a ...

(c. 466–511), and published sometime between 507 and 511. He appointed four commissioners to research customary law that, until the publication of the Salic law, had been recorded only in the minds of designated elders, who would meet in council when their knowledge was required. Transmission was entirely oral. Salic law, therefore, reflects ancient usages and practices. To govern more effectively, having a written code was desirable for monarchs and their administrations.

For the next 300 years, the code was copied by hand, and was amended as required to add newly enacted laws, revise laws that had been amended, and delete laws that had been repealed. In contrast with printing, hand copying is an individual act by an individual copyist with ideas and a style of his own. Each of the several dozen surviving manuscripts features a unique set of errors, corrections, content, and organization. The laws are called "titles", as each one has its own name, generally preceded by ''de'', "of", "concerning". Different sections of titles acquired individual names, which revealed something about their provenances. Some of these dozens of names have been adopted for specific reference, often given the same designation as the overall work, ''lex''.

Merovingian phase

Therecension

Recension is the practice of editing or revising a text based on critical analysis. When referring to manuscripts, this may be a revision by another author. The term is derived from the Latin ("review, analysis").

In textual criticism (as is the ...

of Hendrik Kern organizes all of the manuscripts into five families according to similarity and relative chronological sequence, judged by content and dateable material in the text. Family I is the oldest, containing four manuscripts dated to the eighth and ninth centuries, but containing 65 titles believed to be copies of originals published in the sixth century. In addition, they feature the ''Malbergse Glossen'', " Malberg Glosses", marginal glosses stating the native court word for some Latin words. These are named from native ''malbergo'', "language of the court". Kern's Family II, represented by two manuscripts, is the same as Family I, except that it contains "interpolations or numerous additions, which point to a later period".

Carolingian phase

Family III is split into two divisions. The first, comprising three manuscripts, dated to the eighth–ninth centuries, presents an expanded text of 99 or 100 titles. The Malberg Glosses are retained. The second division, with four manuscripts, not only drops the glosses, but also "bears traces of attempts to make the language more concise".. A statement gives the provenance: "in the 13th year of the reign of our most glorious king of the Franks, Pipin". Some of the internal documents were composed after the reign ofPepin the Short

the Short (; ; ; – 24 September 768), was King of the Franks from 751 until his death in 768. He was the first Carolingian dynasty, Carolingian to become king.

Pepin was the son of the Frankish prince Charles Martel and his wife Rotrude of H ...

, but it is considered to be an emendation initiated by Pepin, so is termed the ''Pipina Recensio''.

Family IV also has two divisions – the first comprised 33 manuscripts; the second, one manuscript. They are characterized by the internal assignment of Latin names to various sections of different provenances. Two of the sections are dated to 768 and 778, but the emendation is believed to be dated to 798, late in the reign of Charlemagne

Charlemagne ( ; 2 April 748 – 28 January 814) was List of Frankish kings, King of the Franks from 768, List of kings of the Lombards, King of the Lombards from 774, and Holy Roman Emperor, Emperor of what is now known as the Carolingian ...

. This edition calls itself the ''Lex Salica Emendata'', or the ''Lex Reformata'', or the ''Lex Emendata'', and is clearly the result of a law code reform by Charlemagne.

By that time, Charlemagne's Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

comprised most of Western Europe. He added laws of choice (free will) taken from the earlier law codes of Germanic peoples not originally part of Francia. These are numbered into the laws that were there, but they have their own, quasisectional title. All the Franks of Francia were subject to the same law code, which retained the overall title of ''Lex Salica''. These integrated sections borrowed from other Germanic codes are the '' Lex Ribuariorum'', later ''Lex Ribuaria'', laws adopted from the Ripuarian Franks

The Rhineland or Ripuarian Franks, also often referred to using the Latin plurals ''Ribuarii'', or ''Ripuarii'', were the Franks who established themselves in and around the formerly Roman city of Cologne, on the Rhine river in what is now Germa ...

, who, before Clovis, had been independent. The ''Lex Alamannorum The Lex Alamannorum and Pactus Alamannorum were two early medieval law codes of the Alamanni. They were first edited in parts in 1530 by Johannes Sichard in Basel.

Pactus Alamannorum

The ''Pactus Alamannorum'' or ''Pactus legis Alamannorum'' is t ...

'' took laws from the Alamanni

The Alemanni or Alamanni were a confederation of Germanic tribes

*

*

*

on the Upper Rhine River during the first millennium. First mentioned by Cassius Dio in the context of the campaign of Roman emperor Caracalla of 213 CE, the Alemanni c ...

, then subject to the Franks. Under the Franks, they were governed by Frankish law, not their own. The inclusion of some of their law as part of the Salic law must have served as a palliative. Charlemagne goes back even earlier to the ''Lex Suauorum'', the ancient code of the Suebi

file:1st century Germani.png, 300px, The approximate positions of some Germanic peoples reported by Graeco-Roman authors in the 1st century. Suebian peoples in red, and other Irminones in purple.

The Suebi (also spelled Suavi, Suevi or Suebians ...

preceding the Alemanni.

Malberg glosses

The Salic law code contains the ''Malberg glosses'', which, despite the name, are not technically glosses in the traditional sense, but rather Germanic terms interspersed through the Latin legal docoment.Hans Henning Hoff, ''Hafliði Másson und die Einflüsse des römischen Rechts in der Grágás'', Walter de Gruyter, 2012, p. 193. These Germanic words and several short sentences are, though heavily corrupted by subsequent copyists unfamiliar with the original language, have been used toreconstruct

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Union ...

the earliest stage of the Dutch language, Old Dutch

In linguistics, Old Dutch ( Modern Dutch: ') or Old Low Franconian (Modern Dutch: ') is the set of dialects that evolved from Frankish spoken in the Low Countries during the Early Middle Ages, from around the 6th Page 55: "''Uit de zesde eeu ...

Elmar Seebold, edited by Elmar Seebold with assistance by Brigitte Bulitta, Elke Krotz, Judith Stieglbauer-Schwarz and Christiane Wanzeck, ''Chronologisches Wörterbuch des deutschen Wortschatzes: Der Wortschatz des 8. Jahrhunderts (und früherer Quellen) (Titelabkürzung: ChWdW8)'', Walter de Gruyter: Berlin & New York, 2001, p. 64, containing what is likely the earliest surviving full sentence in the language:

:serf

Serfdom was the status of many peasants under feudalism, specifically relating to manorialism and similar systems. It was a condition of debt bondage and indentured servitude with similarities to and differences from slavery. It developed du ...

in the feudal system

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was a combination of legal, economic, military, cultural, and political customs that flourished in medieval Europe from the 9th to 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of structuring socie ...

, a half-free farmer, connected to the lord's land, but not owned by that lord. In contrast, a slave was fully owned by the lord.

This sentence is also given as the following:

Some tenets of the law

These laws and their interpretations give an insight into Frankish society. The criminal laws established damages to be paid and fines levied in recompense for injuries to persons and damage to goods,theft

Theft (, cognate to ) is the act of taking another person's property or services without that person's permission or consent with the intent to deprive the rightful owner of it. The word ''theft'' is also used as a synonym or informal shor ...

, and unprovoked insults. One-third of the fine paid court costs. Judicial interpretation was by a jury of peers.

The civil law establishes that an individual person is legally unprotected if he or she does not belong to a family

Family (from ) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). It forms the basis for social order. Ideally, families offer predictabili ...

. The rights of family members were defined; for example, the equal division of land among all living male heirs, in contrast to primogeniture

Primogeniture () is the right, by law or custom, of the firstborn Legitimacy (family law), legitimate child to inheritance, inherit all or most of their parent's estate (law), estate in preference to shared inheritance among all or some childre ...

.

Agnatic succession

One tenet of the civil law is agnatic succession, explicitly excluding females from the inheritance of a throne orfief

A fief (; ) was a central element in medieval contracts based on feudal law. It consisted of a form of property holding or other rights granted by an overlord to a vassal, who held it in fealty or "in fee" in return for a form of feudal alle ...

. Indeed, "Salic law" has often been used simply as a synonym

A synonym is a word, morpheme, or phrase that means precisely or nearly the same as another word, morpheme, or phrase in a given language. For example, in the English language, the words ''begin'', ''start'', ''commence'', and ''initiate'' are a ...

for agnatic succession, but the importance of Salic law extends beyond the rules of inheritance, as it is a direct ancestor of the systems of law in use in many parts of continental Europe today.

Salic law regulates succession according to sex. "Agnatic succession" means succession to the throne or fief going to an agnate of the predecessor – for example, a brother, a son, or nearest male relative through the male line, including collateral agnate branches, for example very distant cousins. Chief forms are agnatic seniority

Agnatic seniority is a patrilineality, patrilineal principle of inheritance where the order of succession to the throne prefers the monarch's younger brother over the monarch's own sons. A monarch's children (the next generation) succeed only ...

and agnatic primogeniture

Primogeniture () is the right, by law or custom, of the firstborn legitimate child to inherit all or most of their parent's estate in preference to shared inheritance among all or some children, any illegitimate child or any collateral relat ...

. The latter, which has been the most usual, means succession going to the eldest son of the monarch; if the monarch had no sons, the throne would pass to the nearest male relative in the male line.

Female inheritance

Concerning the inheritance of land, Salic law said: or, another transcript: The law merely prohibited women from inheriting ancestral "Salic land"; this prohibition did not apply to other property (such aspersonal property

Personal property is property that is movable. In common law systems, personal property may also be called chattels or personalty. In civil law (legal system), civil law systems, personal property is often called movable property or movables—a ...

); and under Chilperic I

Chilperic I ( 539 – September 584) was the king of Neustria (or Soissons) from 561 to his death. He was one of the sons of the Franks, Frankish king Clotaire I and Queen Aregund.

Life

Immediately after the death of his father in 561, he ...

sometime around the year 570, the law was actually amended to permit inheritance of land by a daughter if a man had no surviving sons (This amendment, depending on how it is applied and interpreted, offers the basis for either Semi-Salic succession or male-preferred primogeniture

Primogeniture () is the right, by law or custom, of the firstborn Legitimacy (family law), legitimate child to inheritance, inherit all or most of their parent's estate (law), estate in preference to shared inheritance among all or some childre ...

, or both).

The wording of the law, as well as common usage in those days and centuries afterwards, seems to support an interpretation that inheritance is divided between brothers, and if it is intended to govern succession, it can be interpreted to mandate agnatic seniority, not direct primogeniture. In its use by continental hereditary monarchies since the 15th century, aiming at agnatic succession, the Salic law is regarded as excluding all females from the succession, and prohibiting the transfer of succession rights through any woman. At least two systems of hereditary succession are direct and full applications of the Salic Law: agnatic seniority

Agnatic seniority is a patrilineality, patrilineal principle of inheritance where the order of succession to the throne prefers the monarch's younger brother over the monarch's own sons. A monarch's children (the next generation) succeed only ...

and agnatic primogeniture

Primogeniture () is the right, by law or custom, of the firstborn legitimate child to inherit all or most of their parent's estate in preference to shared inheritance among all or some children, any illegitimate child or any collateral relat ...

.

The Semi-Salic version of succession order stipulates that firstly all-male descendance is applied, including all collateral male lines, but if all such lines are extinct, then the closest female agnate (such as a daughter) of the last male holder of the property inherits, and after her, her own male heirs according to the Salic order. In other words, the female closest to the last incumbent is "regarded as a male" for the purposes of inheritance and succession. This has the effect of following the closest extant blood line (at least in the first instance) and not involving any more distant relatives. The closest female relative might be a child of a relatively junior branch of the whole dynasty, but still inherits due to her position in the male line, due to the longevity of her own branch; any existing senior female lines come behind that of the closest female.

From the Middle Ages, another system of succession, known as cognatic male primogeniture, actually fulfills apparent stipulations of the original Salic law; succession is allowed also through female lines, but excludes the females themselves in favour of their sons. For example, a grandfather, without sons, is succeeded by a son of his daughter, when the daughter in question is still alive. Or an uncle, with no children of his own, is succeeded by a son of his sister, when the sister in question is still alive. This fulfils the Salic condition of "no land comes to a woman, but the land comes to the male sex". This can be called a "quasi-Salic" system of succession and it should be classified as primogenitural, cognatic, and male-preferred.

Applications of the succession and inheritance laws

In France

The Merovingian kings divided their realm equally among all living sons, leading to much conflict and fratricide among the rival heirs. The Carolingians did likewise, but they also possessed the imperial dignity, which was indivisible and passed to only one person at a time. Primogeniture, or the preference for the eldest line in the transmission of inheritance, eventually emerged in France, under the Capetian kings. The early Capetians had only one heir, the eldest son, whom they crowned during their lifetimes. Instead of an equal portion of the inheritance, the younger sons of the Capetian kings received anappanage

An appanage, or apanage (; ), is the grant of an estate, title, office or other thing of value to a younger child of a monarch, who would otherwise have no inheritance under the system of primogeniture (where only the eldest inherits). It was ...

, which is a feudal territory under the suzerainty of the king. Feudal law allowed the transmission of fiefs to daughters in default of sons, which was also the case for the early appanages. Whether feudal law also applied to the French throne, no one knew, until 1316.

The succession in 1316

For a remarkably long period, from the inception of the Capetian dynasty in 987 until the death of Louis X in 1316, the eldest living son of the King of France succeeded to the throne upon his demise. No prior occasion existed to demonstrate whether or not females were excluded from the succession to the crown. Louis X died without a son, but left his wife pregnant. The king's brother, Philip, Count of Poitiers, became regent. Philip prepared for the contingencies withOdo IV, Duke of Burgundy

Odo IV or Eudes IV (1295 – 3 April 1349) was Duke of Burgundy from 1315 until his death and Count of Burgundy and Artois

Artois ( , ; ; Picard: ''Artoé;'' English adjective: ''Artesian'') is a region of northern France. Its territ ...

, maternal uncle of Louis X's daughter and prospective heiress, Joan. If the unborn child were male, he would succeed to the French throne as king; if female, Philip would maintain the regency until the daughters of Louis X reached their majority. The opportunity remained for either daughter to succeed to the French throne.

The unborn child proved to be male, John I John I may refer to:

People

Religious figures

* John I (bishop of Jerusalem)

* John Chrysostom (349 – c. 407), Patriarch of Constantinople

* John I of Antioch (died 441)

* Pope John I of Alexandria, Coptic Pope from 496 to 505

* Pope John I, P ...

, to the relief of the kingdom, but the infant lived for only a few days. Philip saw his chance and broke the agreement with the Duke of Burgundy by having himself anointed at Reims in January 1317 as Philip V of France

Philip V ( 1291 – 3 January 1322), known as the Tall (), was King of France and List of Navarrese monarchs, Navarre (as Philip II) from 1316 to 1322. Philip engaged in a series of domestic reforms intended to improve the management of the kingd ...

. Agnes of France, daughter of Louis IX

Louis IX (25 April 1214 – 25 August 1270), also known as Saint Louis, was King of France from 1226 until his death in 1270. He is widely recognized as the most distinguished of the Direct Capetians. Following the death of his father, Louis ...

, mother of the Duke of Burgundy, and maternal grandmother of the Princess Joan, considered it a usurpation and demanded an assembly of the peers, which Philip V accepted.

An assembly of prelates, lords, the bourgeois of Paris, and doctors of the university, known as the Estates-General of 1317, gathered in February. Philip V asked them to write an argument justifying his right to the throne of France. These "general statements" agreed in declaring that "Women do not succeed in the kingdom of France", formalizing Philip's usurpation and the impossibility for a woman to ascend the throne of France, a principle that remains in force to this day. The Salic law, at the time, was not yet invoked; the arguments put forward in favor of Philip V relied only on the degree of proximity of Philip V with Louis X. Philip had the support of the nobility and had the resources for his ambitions.

Philip won over the Duke of Burgundy by giving him his daughter, also named Joan, in marriage, with the counties of Artois

Artois ( , ; ; Picard: ''Artoé;'' English adjective: ''Artesian'') is a region of northern France. Its territory covers an area of about 4,000 km2 and it has a population of about one million. Its principal cities include Arras (Dutch: ...

and Burgundy

Burgundy ( ; ; Burgundian: ''Bregogne'') is a historical territory and former administrative region and province of east-central France. The province was once home to the Dukes of Burgundy from the early 11th until the late 15th century. ...

as her eventual inheritance. On March 27, 1317, a treaty was signed at Laon

Laon () is a city in the Aisne Departments of France, department in Hauts-de-France in northern France.

History

Early history

The Ancient Diocese of Laon, which rises a hundred metres above the otherwise flat Picardy plain, has always held s ...

between the Duke of Burgundy and Philip V, wherein Joan renounced her right to the throne of France.

The succession in 1328

Philip, too, died without a son, and his brother Charles succeeded him as Charles IV unopposed. Charles, too, died without a son, but also left his wife pregnant. It was another succession crisis, the same as that in 1316; it was necessary both to prepare for a possible regency (and choose a regent) and prepare for a possible succession to the throne. At this point, it had been accepted that women could not claim the crown of France (without any written rule stipulating it yet). Under the application of the agnatic principle, the following were excluded: *The daughters of Louis X, Philip V and Charles IV, including the possible unborn daughter of the pregnant Queen Jeanne d'Évreux *Isabella of France

Isabella of France ( – 22 August 1358), sometimes described as the She-Wolf of France (), was List of English royal consorts, Queen of England as the wife of Edward II of England, King Edward II, and ''de facto'' regent of England from 1327 ...

, sister of Louis X, Philip V, and Charles IV, wife of King Edward II of England

Edward II (25 April 1284 – 21 September 1327), also known as Edward of Caernarfon or Caernarvon, was King of England from 1307 until he was deposed in January 1327. The fourth son of Edward I, Edward became the heir to the throne follo ...

The widow of Charles IV gave birth to a daughter. Isabella of France

Isabella of France ( – 22 August 1358), sometimes described as the She-Wolf of France (), was List of English royal consorts, Queen of England as the wife of Edward II of England, King Edward II, and ''de facto'' regent of England from 1327 ...

, sister of Charles IV, claimed the throne for her son, Edward III of England

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring royal authority after t ...

. The French rejected the claim, noting that "Women cannot transmit a right which they do not possess", a corollary to the succession principle in 1316. The regent, Philip of Valois, became Philip VI of France

Philip VI (; 1293 – 22 August 1350), called the Fortunate (), the Catholic (''le Catholique'') and of Valois (''de Valois''), was the first king of France from the House of Valois, reigning from 1328 until his death in 1350. Philip's reign w ...

in 1328. Philip became king without serious opposition, until his attempt to confiscate Gascony

Gascony (; ) was a province of the southwestern Kingdom of France that succeeded the Duchy of Gascony (602–1453). From the 17th century until the French Revolution (1789–1799), it was part of the combined Province of Guyenne and Gascon ...

in 1337 made Edward III press his claim to the French throne.

Emergence of the Salic law

As far as can be ascertained, Salic law was not explicitly mentioned either in 1316 or 1328. It had been forgotten in the feudal era, and the assertion that the French crown can only be transmitted to and through males made it unique and exalted in the eyes of the French. In 1358 the monk Richard Lescot invoked it to dispute the claim ofCharles II of Navarre

Charles II (, , , 10 October 1332 – 1 January 1387), known as the Bad, was King of Navarre beginning in 1349, as well as Count of Évreux beginning in 1343, holding both titles until his death in 1387.

Besides the Kingdom of Navarre nestled in ...

to the French crown, an argument that would later be echoed by other jurists in defence of the Valois dynasty.

In its origin, therefore, the agnatic principle was limited to the succession to the crown of France. Prior to the Valois succession, Capetian kings granted appanages to their younger sons and brothers, which could pass to male and female heirs. The appanages given to the Valois princes, though, in imitation of the succession law of the monarchy that gave them, limited their transmission to males. Another Capetian lineage, the Montfort of Brittany, claimed male succession in the Duchy of Brittany

The Duchy of Brittany (, ; ) was a medieval feudal state that existed between approximately 939 and 1547. Its territory covered the northwestern peninsula of France, bordered by the Bay of Biscay to the west, and the English Channel to the north. ...

. In this they were supported by the King of England, while their rivals who claimed the traditional female succession in Brittany were supported by the King of France. The Montforts eventually won the duchy by warfare, but had to recognize the suzerainty of the King of France.

This law was by no means intended to cover all matters of inheritance – for example, not the inheritance of movables — only to lands considered " Salic" – and debate remains as to the legal definition of this word, although it is generally accepted to refer to lands in the royal fisc

Under the Merovingians and Carolingians, the fisc (from Latin '' fiscus,'' whence we derive "fiscal") applied to the royal demesne which paid taxes, entirely in kind, from which the royal household was meant to be supported, though it rarely was. ...

. Only several hundred years later, under the direct Capetian kings of France and their English contemporaries who held lands in France, did Salic law become a rationale for enforcing or debating succession.

Shakespeare says that Charles VI rejected Henry V Henry V may refer to:

People

* Henry V, Duke of Bavaria (died 1026)

* Henry V, Holy Roman Emperor (1081/86–1125)

* Henry V, Duke of Carinthia (died 1161)

* Henry V, Count Palatine of the Rhine (–1227)

* Henry V, Count of Luxembourg (1216–1281 ...

's claim to the French throne on the basis of Salic law's inheritance rules, leading to the Battle of Agincourt

The Battle of Agincourt ( ; ) was an English victory in the Hundred Years' War. It took place on 25 October 1415 (Saint Crispin's Day) near Azincourt, in northern France. The unexpected victory of the vastly outnumbered English troops agains ...

. In fact, the conflict between Salic and English law was a justification for many overlapping claims between the French and English monarchs over the French throne.

More than a century later, during the French wars of religion

The French Wars of Religion were a series of civil wars between French Catholic Church, Catholics and Protestantism, Protestants (called Huguenots) from 1562 to 1598. Between two and four million people died from violence, famine or disease di ...

, Philip II of Spain

Philip II (21 May 152713 September 1598), sometimes known in Spain as Philip the Prudent (), was King of Spain from 1556, King of Portugal from 1580, and King of Naples and List of Sicilian monarchs, Sicily from 1554 until his death in 1598. He ...

attempted to claim the French crown for his daughter Isabella Clara Eugenia

Isabella Clara Eugenia (; 12 August 1566 – 1 December 1633), sometimes referred to as Clara Isabella Eugenia, was sovereign of the Spanish Netherlands, which comprised the Low Countries and the north of modern France, with her husband Albert ...

, born of his third wife, Elisabeth of Valois

Elisabeth of France, or Elisabeth of Valois (; ; 2 April 1546 – 3 October 1568), was Queen of Spain as the third wife of Philip II of Spain. She was the eldest daughter of Henry II of France and Catherine de' Medici.

Early life

Elisabeth was ...

in order to prevent the Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , ; ) are a Religious denomination, religious group of French people, French Protestants who held to the Reformed (Calvinist) tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, ...

candidate Henry of Navarre from becoming king. Philip's agents were instructed to "insinuate cleverly" that the Salic law was a "pure invention". Even if the "Salic law" did not really apply to the throne of France, though, the very principle of agnatic succession had become a cornerstone of the French royal succession; they had upheld it in the Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War (; 1337–1453) was a conflict between the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England and Kingdom of France, France and a civil war in France during the Late Middle Ages. It emerged from feudal disputes over the Duchy ...

with the English, and it had produced their kings for more than two centuries. The eventual recognition of Henry of Navarre as King Henry IV of France following his conversion to Catholicism, the first of the Bourbon kings, further solidified the agnatic principle in France.

Although no reference was made to the Salic law, the imperial constitutions of the Bonapartist

Bonapartism () is the political ideology supervening from Napoleon Bonaparte and his followers and successors. The term was used in the narrow sense to refer to people who hoped to restore the House of Bonaparte and its style of government. In ...

First French Empire

The First French Empire or French Empire (; ), also known as Napoleonic France, was the empire ruled by Napoleon Bonaparte, who established French hegemony over much of continental Europe at the beginning of the 19th century. It lasted from ...

and Second French Empire

The Second French Empire, officially the French Empire, was the government of France from 1852 to 1870. It was established on 2 December 1852 by Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, president of France under the French Second Republic, who proclaimed hi ...

continued to exclude women from the succession to the throne. In the lands that Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

conquered, Salic law was adopted, including the Kingdom of Westphalia

The Kingdom of Westphalia was a client state of First French Empire, France in present-day Germany that existed from 1807 to 1813. While formally independent, it was ruled by Napoleon's brother Jérôme Bonaparte. It was named after Westphalia, ...

, the Kingdom of Holland

The Kingdom of Holland ( (contemporary), (modern); ) was the successor state of the Batavian Republic. It was created by Napoleon Bonaparte in March 1806 in order to strengthen control over the Netherlands by replacing the republican governmen ...

, and under Napoleonic influence, Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. It borders Norway to the west and north, and Finland to the east. At , Sweden is the largest Nordic count ...

under the House of Bernadotte

The House of Bernadotte is the monarchy of Sweden, royal family of Sweden, founded there in 1818 by King Charles XIV John of Sweden. It was also the monarchy of Norway, royal family of Norway between 1818 and 1905. Its founder was born in Pau, Py ...

.

Other European applications

Spain

Spain, or the Kingdom of Spain, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe with territories in North Africa. Featuring the Punta de Tarifa, southernmost point of continental Europe, it is the largest country in Southern Eur ...

over the question of whether the heir to the throne should be a female or a male relative. The War of the Austrian Succession

The War of the Austrian Succession was a European conflict fought between 1740 and 1748, primarily in Central Europe, the Austrian Netherlands, Italian Peninsula, Italy, the Atlantic Ocean and Mediterranean Sea. Related conflicts include King Ge ...

was triggered by the Pragmatic Sanction of 1713, in which Charles VI of Austria, who himself had inherited the Austrian patrimony over his nieces as a result of Salic law, attempted to ensure the inheritance directly to his own daughter Maria Theresa of Austria

Maria Theresa (Maria Theresia Walburga Amalia Christina; 13 May 1717 – 29 November 1780) was the ruler of the Habsburg monarchy from 1740 until her death in 1780, and the only woman to hold the position in her own right. She was the sovereig ...

, which was an example of an operation of quasi-Salic law.

In the modern Kingdom of Italy

The Kingdom of Italy (, ) was a unitary state that existed from 17 March 1861, when Victor Emmanuel II of Kingdom of Sardinia, Sardinia was proclamation of the Kingdom of Italy, proclaimed King of Italy, until 10 June 1946, when the monarchy wa ...

, under the House of Savoy

The House of Savoy (, ) is a royal house (formally a dynasty) of Franco-Italian origin that was established in 1003 in the historical region of Savoy, which was originally part of the Kingdom of Burgundy and now lies mostly within southeastern F ...

, succession to the throne was regulated by Salic law.

The British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

and the Hanoverian thrones separated after the death of King William IV of the United Kingdom

William IV (William Henry; 21 August 1765 – 20 June 1837) was King of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and King of Hanover from 26 June 1830 until his death in 1837. The third son of George III, William succeeded h ...

and of Hanover in 1837 because Hanover practiced quasi-Salic law, unlike Britain. King William's niece, Victoria, ascended to the British throne, but the Hanover throne went to William's brother Ernest, Duke of Cumberland.

Salic law was also an important issue in the Schleswig-Holstein Question

Schleswig-Holstein (; ; ; ; ; occasionally in English ''Sleswick-Holsatia'') is the northernmost of the 16 states of Germany, comprising most of the historical Duchy of Holstein and the southern part of the former Duchy of Schleswig. Its c ...

and played a day-to-day role in the inheritance and marriage decisions of common princedoms of the German states, such as Saxe-Weimar

Saxe-Weimar () was one of the Saxon duchies held by the Ernestine branch of the Wettin dynasty in present-day Thuringia. The chief town and capital was Weimar. The Weimar branch was the most genealogically senior extant branch of the House of W ...

, to cite a representative example. European nobility would have confronted Salic issues at every turn in the practice of diplomacy, particularly when they negotiated marriages, since the entire male line had to be extinguished for a land title to pass (by marriage) "to a female's husband". Women rulers were anathema in the German states well into the modern era.

In a similar way, the thrones of the Kingdom of the Netherlands

The Kingdom of the Netherlands (, ;, , ), commonly known simply as the Netherlands, is a sovereign state consisting of a collection of constituent territories united under the monarch of the Netherlands, who functions as head of state. The re ...

and the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg

Luxembourg, officially the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, is a landlocked country in Western Europe. It is bordered by Belgium to the west and north, Germany to the east, and France on the south. Its capital and most populous city, Luxembourg ...

were separated in 1890, with the succession of Princess Wilhelmina as the first Queen regnant

A queen regnant (: queens regnant) is a female monarch, equivalent in rank, title and position to a king. She reigns ''suo jure'' (in her own right) over a realm known as a kingdom; as opposed to a queen consort, who is married to a reigning ...

of the Netherlands. As a remnant of Salic law, the office of the reigning monarch

A monarch () is a head of stateWebster's II New College Dictionary. "Monarch". Houghton Mifflin. Boston. 2001. p. 707. Life tenure, for life or until abdication, and therefore the head of state of a monarchy. A monarch may exercise the highest ...

of the Netherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

is always formally known as "King", though her title may be "Queen". Luxembourg passed to the House of Orange-Nassau

The House of Orange-Nassau (, ), also known as the House of Orange because of the prestige of the princely title of Orange, also referred to as the Fourth House of Orange in comparison with the other noble houses that held the Principality of Or ...

's distantly related agnates, the House of Nassau-Weilburg

The House of Nassau-Weilburg, a branch of the House of Nassau, ruled a division of the County of Nassau, which was a state in what is now Germany, then part of the Holy Roman Empire, from 1344 to 1806.

On 17 July 1806, upon the dissolution of t ...

, but that house also faced extinction in the male line less than two decades later. With no other male-line agnates in the remaining branches of the House of Nassau, Grand Duke William IV adopted a quasi-Salic law of succession to allow him to be succeeded by his daughters.

Literary references

*Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

uses the Salic law as a plot device in ''Henry V Henry V may refer to:

People

* Henry V, Duke of Bavaria (died 1026)

* Henry V, Holy Roman Emperor (1081/86–1125)

* Henry V, Duke of Carinthia (died 1161)

* Henry V, Count Palatine of the Rhine (–1227)

* Henry V, Count of Luxembourg (1216–1281 ...

'', saying it was upheld by the French to bar Henry V's claiming the French throne. ''Henry V'' begins with the Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the Primus inter pares, ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the bishop of the diocese of Canterbury. The first archbishop ...

being asked if the claim might be upheld despite the Salic law. The archbishop replies, "That the ''land Salique'' is in Germany, between the floods of Sala and of Elbe

The Elbe ( ; ; or ''Elv''; Upper Sorbian, Upper and , ) is one of the major rivers of Central Europe. It rises in the Giant Mountains of the northern Czech Republic before traversing much of Bohemia (western half of the Czech Republic), then Ge ...

", implying that the law is German, not French. The archbishop's justification for Henry's claim, which Shakespeare intentionally renders obtuse and verbose (for comedic, as well as politically expedient reasons) is also erroneous, as the Salian Franks

The Salian Franks, or Salians, sometimes referred to using the Latin word or , were a Frankish people who lived in what was is now the Netherlands in the fourth century. They are only mentioned under this name in historical records relating to ...

settled along the lower Rhine

The Rhine ( ) is one of the List of rivers of Europe, major rivers in Europe. The river begins in the Swiss canton of Graubünden in the southeastern Swiss Alps. It forms part of the Swiss-Liechtenstein border, then part of the Austria–Swit ...

and Scheldt

The Scheldt ( ; ; ) is a river that flows through northern France, western Belgium, and the southwestern part of Netherlands, the Netherlands, with its mouth at the North Sea. Its name is derived from an adjective corresponding to Old Englis ...

, which today is for the most part in the Flemish Region

The Flemish Region (, ), usually simply referred to as Flanders ( ), is one of the three communities, regions and language areas of Belgium, regions of Belgium—alongside the Wallonia, Walloon Region and the Brussels, Brussels-Capital Region. ...

.

*The concept of Salic law figures heavily into the story of French author Maurice Druon

Maurice Druon (; 23 April 1918 – 14 April 2009) was a French novelist and a member of the Académie Française, of which he served as "Perpetual Secretary" (chairman) between 1985 and 1999.

Life and career

Born in Paris, France, Druon was the ...

's historical fiction novel series, '' The Accursed Kings (''known as ''Les Rois maudits'' in French). The series, which revolves around the Capetian succession crisis in the early-to-mid 14th century after Philip IV's sons all three die without a male heir, contains seven books which were published between the 1950s-1970s. In the fourth book (''The Royal Succession''), Philip V uses his position as regent while his sister-in-law is pregnant to get his lawyers to come up with a plan to use Salic law to get his niece Joan out of the line of succession. He becomes king after his nephew John I John I may refer to:

People

Religious figures

* John I (bishop of Jerusalem)

* John Chrysostom (349 – c. 407), Patriarch of Constantinople

* John I of Antioch (died 441)

* Pope John I of Alexandria, Coptic Pope from 496 to 505

* Pope John I, P ...

(who'd been swapped with another baby) is ostensibly poisoned by Philip's mother-in-law Mahaut, Countess of Artois

Mahaut of Artois also known as Mathilda (1268 27 November 1329), ruled as Countess of Artois from 1302 to 1329. She was furthermore regent of the County of Burgundy from 1303 to 1315 during the minority and the absence of her daughter, Joan II, ...

e during his christening. In reality, it is widely believed that John died of natural causes and Giannino Baglioni, the man who claimed to be him, was a Pretender

A pretender is someone who claims to be the rightful ruler of a country although not recognized as such by the current government. The term may often be used to either refer to a descendant of a deposed monarchy or a claim that is not legitimat ...

. During the fifth and sixth books, Queen Isabella begins to press her son Edward III's claim to the French throne as the last-living grandson of Philip IV. However, the French nobility are more inclined to bypass her claim under Salic Law in lieu of that of her cousin, Philip VI, the next male-line descendant. The relationship between the two men begins to sour once Edward III reaches his majority and begins to rule on his own, eventually ending with Robert of Artois

Robert I (25 September 1216 – 8 February 1250), called the Good, was the first Count of Artois. He was the fifth (and second surviving) son of King Louis VIII of France and Blanche of Castile.

Life

He received Artois as an appanage, in accordan ...

(who's also fallen out with Philip) convincing him to stake his claim once and for all at the end of the sixth book. The seventh book, ''A King Without a Kingdom,'' skips ahead significantly in time to the lead-up to the devastating defeat of the French at The Battle of Poitiers, which ends with the capture of Philip VI's son John II at the hand of Edward III's son Edward the Black Prince

Edward of Woodstock (15 June 1330 – 8 June 1376), known as the Black Prince, was the eldest son and heir apparent of King Edward III of England. He died before his father and so his son, Richard II, succeeded to the throne instead. Edward n ...

.

*In the novel '' Royal Flash'', by George MacDonald Fraser

George MacDonald Fraser (2 April 1925 – 2 January 2008) was a Scottish author and screenwriter. He is best known for a series of works that featured the character Harry Paget Flashman, Flashman. Over the course of his career he wrote eleven n ...

, the hero, Harry Flashman

Sir Harry Paget Flashman is a fictional character created by Thomas Hughes (1822–1896) in the semi-autobiographical '' Tom Brown's School Days'' (1857) and later developed by George MacDonald Fraser (1925–2008). Harry Flashman appears in a ...

, on his marriage, is presented with the royal consort's portion of the crown jewels, and "The Duchess did rather better"; the character, feeling hard done-by, thinks, "It struck me then, and it strikes me now, that the Salic law was a damned sound idea".G. M. Fraser (2006) ''Royal Flash'', p. 172, Grafton paperback.

*In his novel '' Waverley'', Sir Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European literature, European and Scottish literature, notably the novels ''Ivanhoe'' (18 ...

quotes "Salique Law" when discussing the protagonist's prior requests for a horse and guide to take him to Edinburgh.

See also

* Agnatic descent *Early Germanic law

Germanic law is a scholarly term used to describe a series of commonalities between the various law codes (the ''Leges Barbarorum'', 'laws of the barbarians', also called Leges) of the early Germanic peoples. These were compared with statements i ...

* Paris, BN, lat. 4404

References

Citations

General and cited references

* * * * * * * *External links

Information on the ''Salic law'' and its manuscript tradition on the ' website

A database on Carolingian secular law texts (Karl Ubl, Cologne University, Germany). {{Authority control Prose texts in Latin Law of France Old Dutch Earliest known manuscripts by language 6th-century books in Latin 6th century in Francia 6th century in law 6th-century Frankish writers 6th-century jurists Succession acts Germanic legal codes