Lex Papiria on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The ballot laws of the Roman Republic (Latin: ''leges tabellariae'') were four laws which introduced the

The only detailed ancient account of the ballot laws is

The only detailed ancient account of the ballot laws is

The ballot itself was a small wooden tablet covered with wax, called a ''tabella cerata''. Voters would walk across a narrow causeway, called the ''pons'', and be handed a ballot by an attendant (''rogator''). The voter would mark the ballot and deposit it into a ballot box (''cista'') made of wicker. The ''cista'' was watched over by guards (''custodes''). It was a great honor to be asked to be a ''rogator'' or ''custos'', and only distinguished men were assigned to these roles. In addition to the guards appointed by the presiding officer, each candidate was entitled to a guard at each ballot box.

The ballot itself was a small wooden tablet covered with wax, called a ''tabella cerata''. Voters would walk across a narrow causeway, called the ''pons'', and be handed a ballot by an attendant (''rogator''). The voter would mark the ballot and deposit it into a ballot box (''cista'') made of wicker. The ''cista'' was watched over by guards (''custodes''). It was a great honor to be asked to be a ''rogator'' or ''custos'', and only distinguished men were assigned to these roles. In addition to the guards appointed by the presiding officer, each candidate was entitled to a guard at each ballot box.

To elect magistrates, voters expressed their preference by inscribing the initials of their preferred candidate with a stylus. They were expected to write in their own hand, and discovering multiple ballots with the same handwriting was considered evidence of fraud. When voting to fill multiple positions, such as the ten

To elect magistrates, voters expressed their preference by inscribing the initials of their preferred candidate with a stylus. They were expected to write in their own hand, and discovering multiple ballots with the same handwriting was considered evidence of fraud. When voting to fill multiple positions, such as the ten

The voting reforms have also been linked to a significant change in Roman coin designs. Crawford noted that the

The voting reforms have also been linked to a significant change in Roman coin designs. Crawford noted that the

secret ballot

The secret ballot, also known as the Australian ballot, is a voting method in which a voter's identity in an election or a referendum is anonymous. This forestalls attempts to influence the voter by intimidation, blackmailing, and potential vote ...

to all popular assemblies in the Republic.Yakobson (1995), p. 426. They were all introduced by tribune

Tribune () was the title of various elected officials in ancient Rome. The two most important were the Tribune of the Plebs, tribunes of the plebs and the military tribunes. For most of Roman history, a college of ten tribunes of the plebs ac ...

s, and consisted of the ''lex Gabinia tabellaria'' (or ''lex Gabinia'') of 139 BC, applying to the election of magistrates; the ''lex Cassia tabellaria'' of 137 BC, applying to juries except in cases of treason; the ''lex Papiria'' of 131 BC, applying to the passing of laws; and the ''lex Caelia'' of 107 BC, which expanded the ''lex Cassia'' to include matters of treason. Prior to the ballot laws, voters announced their votes orally to a teller, essentially making every vote public. The ballot laws curtailed the influence of the aristocratic class and expanded the freedom of choice for voters. Elections became more competitive.Yakobson (1995), p. 437. In short, the secret ballot made bribery more difficult.Yakobson (1995), p. 441.

Background

Political context

From the founding of the Roman Republic in 509 BC to the mid second century BC, Rome had expanded from a small city state to a world power. After decisively winning theMacedonian Wars

The Macedonian Wars (214–148 BC) were a series of conflicts fought by the Roman Republic and its Greek allies in the eastern Mediterranean against several different major Greek kingdoms. They resulted in Roman control or influence over Ancient ...

, destroying Carthage in 146 BC, and destroying Corinth in the same year, Rome became the hegemonic power of the Mediterranean. Aside from controlling the Italian Peninsula, it had gained provinces

A province is an administrative division within a country or state. The term derives from the ancient Roman , which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire's territorial possessions outside Italy. The term ''provi ...

in Iberia

The Iberian Peninsula ( ), also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in south-western Europe. Mostly separated from the rest of the European landmass by the Pyrenees, it includes the territories of peninsular Spain and Continental Portugal, compri ...

, Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

, Corsica

Corsica ( , , ; ; ) is an island in the Mediterranean Sea and one of the Regions of France, 18 regions of France. It is the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fourth-largest island in the Mediterranean and lies southeast of the Metro ...

, Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; ; ) is the Mediterranean islands#By area, second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, and one of the Regions of Italy, twenty regions of Italy. It is located west of the Italian Peninsula, north of Tunisia an ...

, Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

, and North Africa

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

, in addition to its many client states and allies.

During this 400 year expansion, Roman politics was largely peaceful, with no civil wars and no recorded political murders. However, the conquest of an empire would cause significant political and social changes. With an empire, political office offered more opportunities for wealth and personal advancement, increasing the stakes of elections. The Italian land conquered by Rome—technically ager publicus

The ''ager publicus'' (; ) is the Latin name for the state land of ancient Rome. It was usually acquired via the means of expropriation from enemies of Rome.

History

In the earliest periods of Roman expansion in central Italy, the ''ager pub ...

, or public land—in practice fell into the hands of rich aristocrats, leading to the rise of large estates called latifundia

A ''latifundium'' (Latin: ''latus'', "spacious", and ''fundus'', "farm", "estate") was originally the term used by ancient Romans for great landed estates specialising in agriculture destined for sale: grain, olive oil, or wine. They were charac ...

. These large estates were worked by slaves from conquered territories, who flooded into Italy in the hundreds of thousands. Due to economies of scale

In microeconomics, economies of scale are the cost advantages that enterprises obtain due to their scale of operation, and are typically measured by the amount of Productivity, output produced per unit of cost (production cost). A decrease in ...

, the use of slave labor

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

, and the appropriation of previously public land, many small farmers found it impossible to compete with the latifundia

A ''latifundium'' (Latin: ''latus'', "spacious", and ''fundus'', "farm", "estate") was originally the term used by ancient Romans for great landed estates specialising in agriculture destined for sale: grain, olive oil, or wine. They were charac ...

and were forced to sell their farms. The dispossession of these farmers, many of whom moved to Rome and became part of the landless poor, caused profound social tension and political upheaval.

The 130s and 120s BC were a turning point for Roman politics. The ballot laws were introduced at a time of rising popular sentiment that saw the rise of populares

''Optimates'' (, ; Latin for "best ones"; ) and ''populares'' (; Latin for "supporters of the people"; ) are labels applied to politicians, political groups, traditions, strategies, or ideologies in the late Roman Republic. There is "heated ...

politicians, who gained power by appealing to the lower classes. Most notably, these included Tiberius Gracchus

Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus (; 163 – 133 BC) was a Roman politician best known for his agrarian reform law entailing the transfer of land from the Roman state and wealthy landowners to poorer citizens. He had also served in the ...

in 133 BC and Gaius Gracchus

Gaius Sempronius Gracchus ( – 121 BC) was a reformist Roman politician and soldier who lived during the 2nd century BC. He is most famous for his tribunate for the years 123 and 122 BC, in which he proposed a wide set of laws, i ...

a decade later. The resulting conflict between populares

''Optimates'' (, ; Latin for "best ones"; ) and ''populares'' (; Latin for "supporters of the people"; ) are labels applied to politicians, political groups, traditions, strategies, or ideologies in the late Roman Republic. There is "heated ...

and optimates

''Optimates'' (, ; Latin for "best ones"; ) and ''populares'' (; Latin for "supporters of the people"; ) are labels applied to politicians, political groups, traditions, strategies, or ideologies in the late Roman Republic. There is "heated ...

would lead to the dissolution of political norms and the rise of political violence. Within decades, mob violence

A riot or mob violence is a form of civil disorder commonly characterized by a group lashing out in a violent public disturbance against authority, property, or people.

Riots typically involve destruction of property, public or private. The p ...

, political assassination

Assassination is the willful killing, by a sudden, secret, or planned attack, of a personespecially if prominent or important. It may be prompted by political, ideological, religious, financial, or military motives.

Assassinations are orde ...

, and even civil war

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

would become routine.Lutz (2006), p. 502. These conflicts would cause the end of the republic in 27 BC. This extended period of unrest is termed the crisis of the Roman Republic

The crisis of the Roman Republic was an extended period of political instability and social unrest from about to 44 BC that culminated in the demise of the Roman Republic and the advent of the Roman Empire.

The causes and attributes of the cri ...

.

Roman constitution

The constitution of the Roman Republic consisted of a complex mix of elected officials (magistrates), popular assemblies, and the Senate. The assemblies elected all magistrates, in addition to passing legislation and having some judicial functions. The magistrates had a wide range of duties, including leading armies, presiding over assemblies, judging cases, managing state finances, and managing public works. The Senate was the only deliberative body of the republic, and was composed of ex-magistrates appointed by a magistrate known as the censor. It nominally had largely advisory powers, but in practice its advice was almost always taken, and it was the predominant body in charge of foreign policy and the treasury. The Republic had three popular assemblies: the Centuriate Assembly, Tribal Assembly, and Plebeian Council. The first elected the higher magistrates,Hall, p. 17. including the twoconsul

Consul (abbrev. ''cos.''; Latin plural ''consules'') was the title of one of the two chief magistrates of the Roman Republic, and subsequently also an important title under the Roman Empire. The title was used in other European city-states thro ...

s, who held extensive powers over all Roman citizens and were commanders-in-chief of the army. The Tribal Assembly elected the lower magistrates: the quaestors

A quaestor ( , ; ; "investigator") was a public official in ancient Rome. There were various types of quaestors, with the title used to describe greatly different offices at different times.

In the Roman Republic, quaestors were elected officia ...

, who managed state finances, and the curule aediles

Aedile ( , , from , "temple edifice") was an elected office of the Roman Republic. Based in Rome, the aediles were responsible for maintenance of public buildings () and regulation of public festivals. They also had powers to enforce public orde ...

, responsible for public works. The Plebeian Council elected the plebeian tribunes

Tribune of the plebs, tribune of the people or plebeian tribune () was the first office of the Roman state that was open to the plebeians, and was, throughout the history of the Republic, the most important check on the power of the Roman Senate ...

and the plebeian aediles. The tribunes presided over the Plebeian Council, proposed legislation, and could veto the actions of all other magistrates. The plebeian aediles had a similar role to the curule aediles.

The Centuriate Assembly consisted of 193 groupings called centuries, each of which had one vote.Hall, p. 18 The vote of a century was determined by the votes of the members of that century who were present to vote. Membership in a century was determined by a citizen's wealth, geographic location, and age (junior or senior). The centuries were heavily weighted in favor of the wealthy, so that the equites

The (; , though sometimes referred to as " knights" in English) constituted the second of the property/social-based classes of ancient Rome, ranking below the senatorial class. A member of the equestrian order was known as an ().

Descript ...

and first class, despite comprising a small portion of the population, were only 8 votes short of a majority of the centuries. Similarly, the landless proletarii, which might have made up 14% of the population, were allocated one century. The centuries voted by class, so that the wealthiest centuries voted first, followed by the less wealthy centuries, and so on. When a majority was reached, voting stopped. The poorer centuries, therefore, rarely had a chance to vote.

The Tribal Assembly was composed of groupings called tribes, where membership in a tribe was determined by geographic location and not, as the name implies, by ancestry. Each tribe had one vote, and the vote of a tribe was determined by the votes of the members. Unlike in the Centuriate Assembly, there is no property requirement. The Plebeian Assembly was similar to the Tribal Assembly, except that only plebeians were permitted, and it was presided by a plebeian tribune. The Plebeian Assembly eventually became the main legislative body of the republic.Hall (1998), p. 20.

In addition to their roles in electing magistrates and passing legislation, the Tribal and Plebeian assemblies could try judicial cases. The Centuriate Assembly also served as the court of highest appeal, especially for capital cases.

In summary, Rome had a mixed constitution

Mixed government (or a mixed constitution) is a form of government that combines elements of democracy, aristocracy and monarchy, ostensibly making impossible their respective degenerations which are conceived in Aristotle's ''Politics'' as an ...

,Lintott (1994), p. 645. with monarchic

A monarchy is a form of government in which a person, the monarch, reigns as head of state for the rest of their life, or until abdication. The extent of the authority of the monarch may vary from restricted and largely symbolic (constitutio ...

, oligarchic

Oligarchy (; ) is a form of government in which power rests with a small number of people. Members of this group, called oligarchs, generally hold usually hard, but sometimes soft power through nobility, fame, wealth, or education; or throug ...

, and democratic elements represented by the senior magistrates, the Senate, and the assemblies respectively. The ancient Greek writer Polybius

Polybius (; , ; ) was a Greek historian of the middle Hellenistic period. He is noted for his work , a universal history documenting the rise of Rome in the Mediterranean in the third and second centuries BC. It covered the period of 264–146 ...

wrote that at the time of the Second Punic War

The Second Punic War (218 to 201 BC) was the second of Punic Wars, three wars fought between Ancient Carthage, Carthage and Roman Republic, Rome, the two main powers of the western Mediterranean Basin, Mediterranean in the 3rd century BC. For ...

, the aristocratic element was dominant in Rome. Even so, the people of Rome (populus romanus

SPQR or S.P.Q.R., an initialism for (; ), is an emblematic phrase referring to the government of the Roman Republic. It appears on documents made public by an inscription in stone or metal, in dedications of monuments and public works, and on ...

) held important practical and theoretical standing in the Roman state. Only the people, as represented by the assemblies, could elect magistrates, declare war, or try capital cases. In the second century BC, the assemblies would pass important laws on a wide range of issues, including citizenship, finance, social matters, religion, and war and peace. Voting by the Roman people

The Roman people was the ethnicity and the body of Roman citizens

(; ) during the Roman Kingdom, the Roman Republic, and the Roman Empire. This concept underwent considerable changes throughout the long history of the Roman civilisation, as i ...

, therefore, was critical to the functioning of the Republic. It was necessary not only for elections

An election is a formal group decision-making process whereby a population chooses an individual or multiple individuals to hold public office.

Elections have been the usual mechanism by which modern representative democracy has operated ...

, but also for legislative and judicial reasons.

Voting before the ballot laws

Before the ballot laws were introduced, votes were conducted by voice. Voters in a certain century or tribe would gather together in a venue and express their preference, one by one, to a teller (''rogator''). The teller would tabulate the votes and announce the result to the presiding official. Votes were therefore impossible to keep secret. Although there are few recorded instances of direct voter intimidation, a variety of social pressures reduced voter freedom. For example, both centuries and tribes were based on geographic location, so voters voted with the people most likely to know them. The ''rogator'' himself was a man of distinction, such as a Senator. Voters might be reluctant to offend their family, their landlords, or their military commanders. More significantly, Rome had a strong system of patronage. In this system, a wealthy patron would support his less wealthy client with food, money, business advice, and legal assistance. In exchange, the client would grant the patron favours in his personal and public life. One of the most significant was political support, which included campaigning for the patron and voting for him in elections. Another major source of influence was largess (largitio), also calledambitus

In ancient Roman law, ''ambitus'' was a crime of political corruption, mainly a candidate's attempt to influence the outcome (or direction) of an election through bribery or other forms of soft power. The Latin word ''ambitus'' is the origin of ...

. In an attempt to buy votes, candidates would hold lavish banquets and games, or even directly bribe voters with wine, oil, or money. For example, Titus Annius Milo

Titus Annius Milo (died 48 BC) was a Roman politician and agitator. The son of Gaius Papius Celsus, he was adopted by his maternal grandfather, Titus Annius Luscus. In 52 BC, he was prosecuted for the murder of Publius Clodius Pulcher and exile ...

, when canvassing for the consulate in 53 BC, promised each voter in the tribes 1000 asses. In the course of the second century BC, a long series of laws were passed to crack down on ambitus

In ancient Roman law, ''ambitus'' was a crime of political corruption, mainly a candidate's attempt to influence the outcome (or direction) of an election through bribery or other forms of soft power. The Latin word ''ambitus'' is the origin of ...

. This included the ''lex Orchia'' of 182 BC, which restricted the amount one could spend on banquets, and the '' lex Baebia'' one year later, aimed at directly combating ambitus. Despite Plutarch's claim that the giving of gifts in exchange for votes was punishable by death, these laws appeared to have little effect.

Ballot laws

The ballot laws were not the first election laws to be passed. Due to the apparent ineffectiveness of the anti-corruption ''lex Baebia'' of 181 BC, the Cornelian-Fulvian law of 159 BC was passed, again targeting corruption. Extending the sumptuary law (''lex Orchia'') of 182 BC, the ''lex Didia'' of 143 BC restricted spending on banquets in all of Italy. In 145 BC, a bill by the tribuneLucius Licinius Crassus

Lucius Licinius Crassus (140 – September 91 BC) was a Roman orator and statesman who was a Roman consul and Roman censor, censor and who is also one of the main speakers in Cicero's dramatic dialogue on the art of oratory ''De Oratore'', set jus ...

proposed that priesthoods be elected instead of co-opted

Co-option, also known as co-optation and sometimes spelt cooption or cooptation, is a term with three common meanings. It may refer to:

1) The process of adding members to an elite group at the discretion of members of the body, usually to manag ...

. While advocating for his proposal, he pointedly turned his back on the senators in the comitium

The Comitium () was the original open-air public meeting space of Ancient Rome, and had major religious and prophetic significance. The name comes from the Latin word for "assembly". The Comitium location at the northwest corner of the Roman Foru ...

and spoke directly to the people in the Roman Forum

A forum (Latin: ''forum'', "public place outdoors", : ''fora''; English : either ''fora'' or ''forums'') was a public square in a municipium, or any civitas, of Ancient Rome reserved primarily for the vending of goods; i.e., a marketplace, alon ...

.

The only detailed ancient account of the ballot laws is

The only detailed ancient account of the ballot laws is Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, orator, writer and Academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises tha ...

's De Legibus

''On the Laws'', also known by its Latin name ( abbr. ), is a Socratic dialogue written by Marcus Tullius Cicero during the last years of the Roman Republic. It bears the same name as Plato's famous dialogue, '' The Laws''. Unlike his previou ...

(III. 33–9). Written in the last years of the Republic, ''De legibus

''On the Laws'', also known by its Latin name ( abbr. ), is a Socratic dialogue written by Marcus Tullius Cicero during the last years of the Roman Republic. It bears the same name as Plato's famous dialogue, '' The Laws''. Unlike his previou ...

'' is a fictional dialogue between Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, orator, writer and Academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises tha ...

, his brother Quintus

Quintus is a male given name derived from ''Quintus (praenomen), Quintus'', a common Latin language, Latin forename (''praenomen'') found in the culture of ancient Rome. Quintus derives from Latin word ''quintus'', meaning "fifth".

Quintus is ...

, and their mutual friend Atticus. In the dialogue, the three discuss their conception of the ideal Roman constitution. In Book III 33–9, Cicero summarizes the passage of the ballot laws; the three subsequently criticize the laws and propose repeal or alteration. Cicero, an opponent of the laws, portrays the sponsors of the ballot laws as demagogues currying favor with the masses.Williamson (2005), p. 306.

The ballot laws were highly controversial and strongly opposed by the optimates

''Optimates'' (, ; Latin for "best ones"; ) and ''populares'' (; Latin for "supporters of the people"; ) are labels applied to politicians, political groups, traditions, strategies, or ideologies in the late Roman Republic. There is "heated ...

. Pliny remarks:

lex Gabinia tabellaria

The first ballot law (the ''lex Gabinia tabellaria'') was introduced in 139 BC for the election ofmagistrates

The term magistrate is used in a variety of systems of governments and laws to refer to a civilian officer who administers the law. In ancient Rome, a ''magistratus'' was one of the highest ranking government officers, and possessed both judici ...

by the tribune Aulus Gabinius

Aulus Gabinius ( – 48 or 47 BC) was a politician and general of the Roman Republic. He had an important career, culminating with a consulship in 58 BC, mainly thanks to the patronage of Pompey. His name is mostly associated with the '' le ...

, whom Cicero called "an unknown and sordid agitator".Cicero, p. 477. The law mandated a secret ballot for the election of magistrates in all assemblies. Gabinius, the first person of that name known to hold political office in Rome, was from a family that had low-status (possibly slave origins) in Cales

Cales was an ancient city of Campania, in today's ''comune'' of Calvi Risorta in southern Italy, belonging originally to the Aurunci/ Ausoni, on the Via Latina.

The Romans captured it in 335 BC and established a colony with Latin rights of ...

, and was able to enter politics due to the military success of his father.

The reasons behind the law are unclear, as are the circumstances surrounding its passage. It is thought that this law was adopted following the acquittal that Lucius Aurelius Cotta obtained by corrupting the judges in 138 BC. According to the Cambridge Ancient History

''The Cambridge Ancient History'' is a multi-volume work of ancient history from Prehistory to Late Antiquity, published by Cambridge University Press. The first series, consisting of 12 volumes, was planned in 1919 by Irish historian J. B. Bur ...

, the law was undoubtedly justified as giving freedom to the people, but may also have been intended to curb bribery of voters by candidates. Ursula Hall believes that the law "was undoubtedly largely supported by men of substance wanting to challenge aristocratic control of office. In purpose this law was not, in a modern sense, 'democratic', not designed to give more power to voters, much less candidates, from lower ranks in the Roman system." Hall and Harris both claim because literacy was uncommon in ancient Rome and the written ballot would have required literacy, the Gabinian law must have restricted voting to a small and prosperous minority, with Harris suggesting that this was intentional. However, Alexander Yakobson

Alexander Anatolyevich Yakobson () is an Israeli historian, professor of Ancient history at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, political activist, and commentator.

Background

Alexander Anatolyevich Yakobson was born on October 5, 1959, in Mo ...

argues that the Gabinian law was a genuine piece of popular legislation benefiting a broad section of the electorate. He points out that the law applied just as much to the Tribal Assembly, which had no property qualification, as it did to the Centuriate Assembly. He also claims that the level of literacy necessary for voting was low as voters only had to write the initials of the preferred candidate. The assumption that literacy was low is itself controversial. In fact, Edward Best flipped the argument around, using the ballot laws as evidence that literacy was widespread in Rome. Subsequent improvements or extensions to the law were the '' lex Papiria''(131 BC), the ''lex Maria'' and ''lex Caelia'' (107 BC), all aimed at limiting corruption. Together these laws are called ''leges tabellariae''.

lex Cassia tabellaria

The second law was introduced byLucius Cassius Longinus Ravilla

Lucius Cassius Longinus Ravilla was a Roman politician. He served as consul in 127 BC and censor at the following lustrum in 125 BC.

His first recorded office was that of tribune of the plebs in 137 BC. As a tribune of the plebs, h ...

in 137 BC. It extended the secret ballot

The secret ballot, also known as the Australian ballot, is a voting method in which a voter's identity in an election or a referendum is anonymous. This forestalls attempts to influence the voter by intimidation, blackmailing, and potential vote ...

for trials in the popular assembly. It mandated the secret ballot for judicial votes, with the exception of cases on treason. The passing of the law was resisted by the tribune Marcus Antius Briso who threatened to apply his veto

A veto is a legal power to unilaterally stop an official action. In the most typical case, a president (government title), president or monarch vetoes a bill (law), bill to stop it from becoming statutory law, law. In many countries, veto powe ...

, with the support of one of the consuls of the year. The threat of veto was unusual, since it was not customary for it to be applied on matters held to be in the plebeians

In ancient Rome, the plebeians or plebs were the general body of free Roman citizens who were not Patrician (ancient Rome), patricians, as determined by the Capite censi, census, or in other words "commoners". Both classes were hereditary.

Et ...

' interest. Briso was apparently dissuaded from actually applying the veto by Scipio Aemilianus

Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus Aemilianus (185 BC – 129 BC), known as Scipio Aemilianus or Scipio Africanus the Younger, was a Roman general and statesman noted for his military exploits in the Third Punic War against Carthage and durin ...

, perhaps displaying populares

''Optimates'' (, ; Latin for "best ones"; ) and ''populares'' (; Latin for "supporters of the people"; ) are labels applied to politicians, political groups, traditions, strategies, or ideologies in the late Roman Republic. There is "heated ...

sentiments.

Cassius was a noble Plebeian who would become consul in 127 BC and censor in 125 BC. Cicero writes of the opposition to this law:

In his speech ''Pro Sestio'', he further comments that "A ballot law was proposed by Lucius Cassius. The people thought that their liberty was at stake. The leaders of the State held a different opinion; in a matter that concerned the safety of the optimates, they dreaded the impetuosity of the masses and the licence afforded by the ballot."Cicero Pro Sestio 103

133 BC was a turning point in Roman politics, marking the beginning of the crisis of the Roman Republic

The crisis of the Roman Republic was an extended period of political instability and social unrest from about to 44 BC that culminated in the demise of the Roman Republic and the advent of the Roman Empire.

The causes and attributes of the cri ...

. In that year, Tiberius Gracchus

Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus (; 163 – 133 BC) was a Roman politician best known for his agrarian reform law entailing the transfer of land from the Roman state and wealthy landowners to poorer citizens. He had also served in the ...

was elected tribune and forced through a land redistribution law without consulting the Senate and against the veto of another tribune—both of which violated custom, if not the law. At the end of the year, he sought re-election, breaking another unwritten rule forbidding consecutive terms. While the assembly was voting, a group of senators beat Tiberius to death, along with more than 300 of his supporters. This act of violence marked the first instance of political bloodshed in Republican history, and was considered especially egregious because the person of a tribune was sacrosanct.

lex Papiria

The third ballot law was introduced in 131 BC by Gaius Papirius Carbo, and applied to the ratification and repeal of legislation—which, by this point, was mainly the duty of the Plebeian Council. Carbo, called a "rabble-rouser" by Cicero, was at the time on the land commission charged with implementingTiberius Gracchus

Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus (; 163 – 133 BC) was a Roman politician best known for his agrarian reform law entailing the transfer of land from the Roman state and wealthy landowners to poorer citizens. He had also served in the ...

' land redistribution law. Pointing to this association, Hall argues that unlike the earlier ''lex Gabinia'', the ''lex Papiria'' was undoubtedly passed in the interests of popular reform.

Serious political violence would erupt again with the rise of another populares

''Optimates'' (, ; Latin for "best ones"; ) and ''populares'' (; Latin for "supporters of the people"; ) are labels applied to politicians, political groups, traditions, strategies, or ideologies in the late Roman Republic. There is "heated ...

tribune--Gaius Gracchus

Gaius Sempronius Gracchus ( – 121 BC) was a reformist Roman politician and soldier who lived during the 2nd century BC. He is most famous for his tribunate for the years 123 and 122 BC, in which he proposed a wide set of laws, i ...

, the brother of Tiberius Gracchus

Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus (; 163 – 133 BC) was a Roman politician best known for his agrarian reform law entailing the transfer of land from the Roman state and wealthy landowners to poorer citizens. He had also served in the ...

. In both 123 BC and 122 BC, Gaius was elected tribune of the people. He proposed a series of popular laws, far more wide-ranging than those of his brother. These included an extension to Tiberius' land redistribution bill; a grain subsidy for poorer citizens; reforms to the judicial system; the free issue of clothes and equipment to soldiers; the founding of overseas colonies to help the landless; a reduction in the length of military service; and citizenship for Italian allies. In 121 BC, after Gaius failed re-election, one of his supporters killed an attendant of the consul Lucius Opimius

Lucius Opimius was a Roman politician who held the consulship in 121 BC, in which capacity and year he ordered the execution of 3,000 supporters of popular leader Gaius Gracchus without trial, using as pretext the state of emergency declared aft ...

. A confrontation ensued between the Gaius and the Senate, which quickly turned violent after the Senate urged the overthrow of Gaius. The consul rallied a militia, and together with Cretan archers who happened to be near the city, attacked Gaius and his supporters. Gaius committed suicide rather than be captured, and Opimius subsequently executed 3000 of his supporters.

The first three ballot laws were apparently not perfectly effective, as they were followed by a series of further laws enforcing the secrecy of the ballot. In 119 BC, the tribune Gaius Marius

Gaius Marius (; – 13 January 86 BC) was a Roman general and statesman. Victor of the Cimbrian War, Cimbric and Jugurthine War, Jugurthine wars, he held the office of Roman consul, consul an unprecedented seven times. Rising from a fami ...

introduced a law that narrowed the causeway leading to the ballot box, in order to prevent non-voters from standing on the causeway and intimidating voters. The law was passed despite vigorous Senate opposition.Yakobson (1995), p. 433. The other secrecy-enforcing laws are not explicitly mentioned by ancient sources, but Cicero indicates their existence by proposing to abolish:

Yakobson views this passage as evidence that these laws were effective at ensuring the secrecy of the ballot, which explains why Cicero, an opponent of the ballot laws, proposed to abolish them. As additional evidence, he points out that there is no record of any further attempts to violate the secrecy of the ballot after the Marian law.

lex Coelia tabellaria

The fourth and final law was introduced in 107 BC by the tribuneGaius Coelius Caldus

Gaius Coelius Caldus was a consul of the Roman Republic in 94 BC alongside his colleague Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus.

In 107 BC, Coelius Caldus was elected tribune of the plebs and passed a '' lex tabellaria,'' which ordained that in cases of ...

, and expanded the Cassian law to cases of treason. In 107 BC, a Roman army under the consul Lucius Cassius Longinus was dealt a crushing defeat by the Tigurini at the Battle of Burdigala

The Battle of Burdigala (Roman name for Bordeaux) took place during the Cimbrian War in 107 BC. The battle was fought between a combined Germano-Celtic army including the Helvetian Tigurini under the command of Divico, and the forces of the ...

. His legate

Legate may refer to: People

* Bartholomew Legate (1575–1611), English martyr

* Julie Anne Legate (born 1972), Canadian linguistics professor

* William LeGate (born 1994), American entrepreneur

Political and religious offices

*Legatus, a hig ...

Gaius Popilius Laenas negotiated a humiliating agreement to save the lives of the soldiers.Santangelo (2015), p. 42 The agreement was considered unacceptable at Rome, and Coelius planned to prosecute him in an assembly of the people. Before he did so, he introduced the final ballot law. The law was passed and the prosecution was successful, resulting in Popilius being sentenced to exile. Cicero, who wrote in relation to the Cassian law that the optimates dreaded the "impetuosity of the masses and the licence accorded by the ballot" on matters affecting their safety, wrote:

"as long as he oeliuslived he repented of having injured the republic, for the purpose of oppressing Caius Popilius".

Voting after the ballot laws

The ballot itself was a small wooden tablet covered with wax, called a ''tabella cerata''. Voters would walk across a narrow causeway, called the ''pons'', and be handed a ballot by an attendant (''rogator''). The voter would mark the ballot and deposit it into a ballot box (''cista'') made of wicker. The ''cista'' was watched over by guards (''custodes''). It was a great honor to be asked to be a ''rogator'' or ''custos'', and only distinguished men were assigned to these roles. In addition to the guards appointed by the presiding officer, each candidate was entitled to a guard at each ballot box.

The ballot itself was a small wooden tablet covered with wax, called a ''tabella cerata''. Voters would walk across a narrow causeway, called the ''pons'', and be handed a ballot by an attendant (''rogator''). The voter would mark the ballot and deposit it into a ballot box (''cista'') made of wicker. The ''cista'' was watched over by guards (''custodes''). It was a great honor to be asked to be a ''rogator'' or ''custos'', and only distinguished men were assigned to these roles. In addition to the guards appointed by the presiding officer, each candidate was entitled to a guard at each ballot box.

To elect magistrates, voters expressed their preference by inscribing the initials of their preferred candidate with a stylus. They were expected to write in their own hand, and discovering multiple ballots with the same handwriting was considered evidence of fraud. When voting to fill multiple positions, such as the ten

To elect magistrates, voters expressed their preference by inscribing the initials of their preferred candidate with a stylus. They were expected to write in their own hand, and discovering multiple ballots with the same handwriting was considered evidence of fraud. When voting to fill multiple positions, such as the ten tribune

Tribune () was the title of various elected officials in ancient Rome. The two most important were the Tribune of the Plebs, tribunes of the plebs and the military tribunes. For most of Roman history, a college of ten tribunes of the plebs ac ...

s, it is unclear whether citizens inscribed the initials of only one candidate or of all ten. Nicolet argues for the single vote theory, pointing out that one round of voting sometimes failed to fill all tribune positions or even both consulships.Nicolet (1988), p. 275. Taylor believes the balance of evidence is against the single vote theory.Hall (1998), p. 27. However individuals were expected to vote and however the votes were aggregated, it is clear that a century or tribe was expected to send forth as many names as there were positions to be filled.

For judicial assemblies, jurymen were handed pre-inscribed ballots with A on one side and D on the other, representing Absolvo ("I acquit") or Damno ("I condemn"). The jurymen were expected to erase one of the letters without revealing their verdict. It was also possible for the ballot to contain L ("libero") instead of A, or C ("condemno") instead of D. The juror could even erase both sides of the ballot to indicate that the matter is unclear to him.

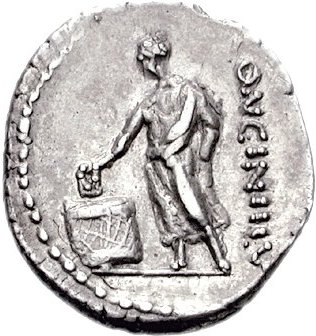

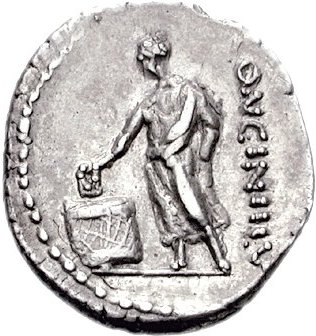

For legislation, voters wrote V for Uti rogas (“as you ask”) or A for antiquo “as they are” to express approval or disapproval of a proposal. A coin from 63 BCE (right) depicts a voter dropping a ballot inscribed with "V" into a cista, indicating approval of a proposal.

Aftermath

The ballot laws had various effects on the republic. In the traditional view, they were a democratic reform that increased voter choice and reduced the influence of the upper classes. This is the view taken by Cicero, an aristocrat and opponent of the ballot laws: Cicero further comments: "the people cherishes its privileges of voting by ballot, which allows a man to wear a smooth brow while it cloaks the secrets of his heart, and leaves him free to act as he chooses, while he gives any promise he may be asked to give". This reduction in influence was especially true for patrons and clients, as clients were expected to do favours for their patrons in return for financial support. With the secret ballot, clients could simply vote for the candidate of their choice without losing their patrons’ support. Yakobson suspects that this "must have had its impact on the nature of patron-client relations in this period." One of the justifications for the ballot laws—aside from protecting the freedom of the people—may have been to curb corruption, since it was no longer possible for candidates to check whether a citizen voted for him. If that was the intention, the ballot laws had the opposite effect. Candidates could no longer rely on the support of their clients or of other citizens to whom they owed favours, making canvassing more important. In addition, candidates could previously bribe voters by promising payment upon receiving their vote. With the secret ballot, this was no longer possible, making it necessary to bribe potential as well as actual voters. Furthermore, voters had the option of accepting bribes from every candidate and voting for the highest bidder, or voting their conscience. This made bribery a more competitive affair as candidates attempted to outbid each other, either by holding lavish games and feasts or by directly promising money to voters. Despite the expansion in voter freedom, the ballot laws did not reduce the aristocratic dominance of elections. The list of consuls and other elected officials is not any less aristocratic after the laws than before. In the last two centuries of the republic, more than half of the consuls were sons or grandsons of former consuls, and a third of consuls had at least one son who would become a consul. One of the practical effects of the ballot laws was to increase the amount of time needed for voting, as ballot voting was much slower than voice voting due to the time needed to hand out the ballots, inscribe them, and count the votes. As a possible consequence, voting for elections in the Tribal Assembly became simultaneous in the late Republic. Previously, the tribes voted sequentially, with the votes of each tribe announced after the members finished voting. Voting in the Centuriate Assembly also became simultaneous in the late Republic, with the centuries in each class voting at one call—although the classes still voted in sequence. It is not clear whether these changes occurred before or after the ballot laws. There are other possible reasons for the change to simultaneous voting, including putting the tribes on an equal footing, or avoiding the bandwagon effect. Therefore, it is not certain that the ballot laws were the cause of the change.Coinage

The voting reforms have also been linked to a significant change in Roman coin designs. Crawford noted that the

The voting reforms have also been linked to a significant change in Roman coin designs. Crawford noted that the denarius

The ''denarius'' (; : ''dēnāriī'', ) was the standard Ancient Rome, Roman silver coin from its introduction in the Second Punic War to the reign of Gordian III (AD 238–244), when it was gradually replaced by the ''antoninianus''. It cont ...

of 137 BC marked a ‘decisive break with the traditional approach to selection of coin types’. Coin designs began to show a great variety of different themes, changing each year, and this continued until the end of the Republic. The process was summarised by Flower:Traditionally, the Roman mint had favored repetitive coin types in patterns similar to the coins of Greek cities, especially of those in southern Italy. Now coin types started to change annually and to reflect designs chosen by the individual officials in charge of the mint each year. The new coins displayed a varied array of types that could refer to religious symbols, political ideas, anniversaries of historical events, monuments or buildings in Rome, or to the achievements and status of the moneyer's ancestors. The effort put into coin designs suggests that an audience for these images was envisioned, presumably beyond the circle of the moneyer's immediate family and friends. At the same time, the shift gave the moneyers themselves and their traditionally relatively humble job at the mint much more publicity and symbolic political capital than ever before. It has been argued that these new coin designs were aimed at the voters, who were now less open to more direct forms of pressure and influence.Thus, as the mint magistrates were mostly young men at the start of their political career, the selection of coin design now offered an unrivalled opportunity to canvass the entire voting population:

The moneyer had the right to put a design of his own choosing on the state's money. Each coin offered the chance to introduce the moneyer's name to the public, whose votes he would soon seek in his bid for thequaestorship A quaestor ( , ; ; "investigator") was a public official in ancient Rome. There were various types of quaestors, with the title used to describe greatly different offices at different times. In the Roman Republic, quaestors were elected officia ...… The object was self-promotion.

Loss of relevance

After the violent deaths ofTiberius Gracchus

Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus (; 163 – 133 BC) was a Roman politician best known for his agrarian reform law entailing the transfer of land from the Roman state and wealthy landowners to poorer citizens. He had also served in the ...

in 133 BC and Gaius Gracchus

Gaius Sempronius Gracchus ( – 121 BC) was a reformist Roman politician and soldier who lived during the 2nd century BC. He is most famous for his tribunate for the years 123 and 122 BC, in which he proposed a wide set of laws, i ...

in 121 BC, political violence in Rome continued to intensify, soon becoming the norm and not the exception. The following century was occupied by numerous civil wars

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.James Fearon"Iraq' ...

. In 88 BC, for the first time in Republican history, Sulla

Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix (, ; 138–78 BC), commonly known as Sulla, was a Roman people, Roman general and statesman of the late Roman Republic. A great commander and ruthless politician, Sulla used violence to advance his career and his co ...

marched on Rome and occupied the city. This was followed by (among others) Sulla's civil war

Sulla's civil war was fought between the Roman general Sulla and his opponents, the Cinna-Marius faction (usually called the Marians or the Cinnans after their former leaders Gaius Marius and Lucius Cornelius Cinna), in the years 83–82 BC. ...

, the Catiline Conspiracy, Caesar's Civil War

Caesar's civil war (49–45 BC) was a civil war during the late Roman Republic between two factions led by Julius Caesar and Pompey. The main cause of the war was political tensions relating to Caesar's place in the Republic on his expected ret ...

, the Battle of Philippi

The Battle of Philippi was the final battle in the Liberators' civil war between the forces of Mark Antony and Octavian (of the Second Triumvirate) and the leaders of Julius Caesar's assassination, Brutus and Cassius, in 42 BC, at Philippi in ...

, and finally the War of Actium

The War of Actium (32–30 BC) was the last civil war of the Roman Republic, fought between Mark Antony (assisted by Cleopatra and by extension Ptolemaic Egypt) and Octavian. In 32 BC, Octavian convinced the Roman Senate to declare war on the ...

.

After the Final War ended in 30 BC, Octavius controlled all of Rome. He concentrated the powers of consul, tribune, and pontifex maximus in his own hands, ruling as an autocrat in all but name. Octavius, renamed Augustus

Gaius Julius Caesar Augustus (born Gaius Octavius; 23 September 63 BC – 19 August AD 14), also known as Octavian (), was the founder of the Roman Empire, who reigned as the first Roman emperor from 27 BC until his death in A ...

in 27 BC, would be the first Roman emperor. These events marked the end of the Republic and the beginning of the Principate

The Principate was the form of imperial government of the Roman Empire from the beginning of the reign of Augustus in 27 BC to the end of the Crisis of the Third Century in AD 284, after which it evolved into the Dominate. The principate was ch ...

. Although the assemblies continued to meet during the Principate, Augustus removed their judicial role and began transferring their electoral power to the Senate; his successor Tiberius would completely end the electoral role of the assemblies.Garzetti (2014), p. 24 The assemblies continued to have legislative powers, but even under Augustus this power was exercised more and more rarely. Rome became an autocratic state in all but name, and the ballot laws became irrelevant to the running of the state.

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{Ancient Rome topics Election law Roman law Reform in the Roman Republic 2nd century BC in the Roman Republic Crisis of the Roman Republic