Leonard MacNally on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Leonard McNally or MacNally (27 September 1752 – 13 February 1820) was an Irish barrister, playwright, lyricist, founding member of the

Returning to Ireland, McNally developed a successful career as a barrister in Dublin. He developed an expertise in the

Returning to Ireland, McNally developed a successful career as a barrister in Dublin. He developed an expertise in the

After his death in 1820, it emerged that McNally had for many years been an informant for the government, and one of the most successful British spies in Irish republican circles that there has ever been. When, in 1794, a United Irishmen plot to seek aid from Revolutionary France was uncovered by the British government, McNally turned informer to save himself, although, subsequently, he also received payment for his services. McNally was paid an annual pension in respect of his work as an informer of £300 a year, from 1794 until his death in 1820.

From 1794, McNally systematically informed on his United Irishmen colleagues, who often gathered at his house for meetings. It was McNally that betrayed

After his death in 1820, it emerged that McNally had for many years been an informant for the government, and one of the most successful British spies in Irish republican circles that there has ever been. When, in 1794, a United Irishmen plot to seek aid from Revolutionary France was uncovered by the British government, McNally turned informer to save himself, although, subsequently, he also received payment for his services. McNally was paid an annual pension in respect of his work as an informer of £300 a year, from 1794 until his death in 1820.

From 1794, McNally systematically informed on his United Irishmen colleagues, who often gathered at his house for meetings. It was McNally that betrayed

McNally was a successful dramatist and wrote a number of well-constructed but derivative comedies, as well as comic operas. His first dramatic work was ''The Ruling Passion'', a comic opera written in 1771, and he is known to have authored at least twelve plays between 1779 and 1796 as well as other comic operas. His works include ''The Apotheosis of Punch'' (1779), a satire on the Irish playwright

McNally was a successful dramatist and wrote a number of well-constructed but derivative comedies, as well as comic operas. His first dramatic work was ''The Ruling Passion'', a comic opera written in 1771, and he is known to have authored at least twelve plays between 1779 and 1796 as well as other comic operas. His works include ''The Apotheosis of Punch'' (1779), a satire on the Irish playwright

'Saunders's Newsletter'

seeking damages for the severe injury caused by the circulation of his death. In June 1820, McNally was on his deathbed, and although he had been a Protestant for most of his adult life, he sought

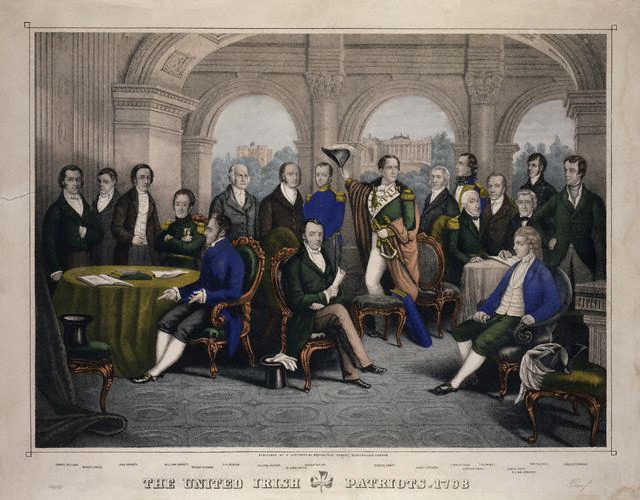

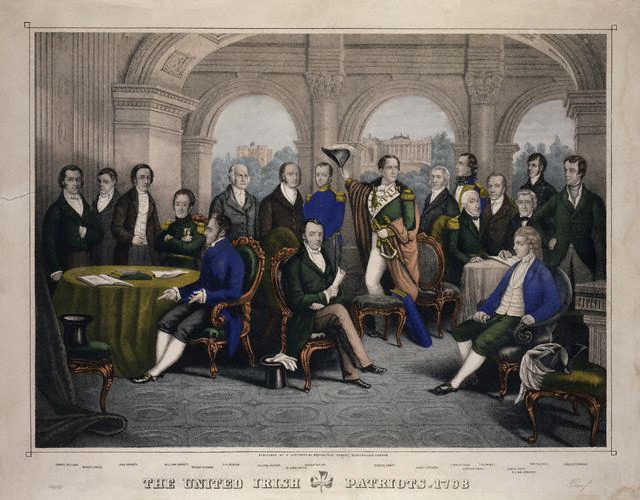

United Irishmen

The Society of United Irishmen was a sworn association, formed in the wake of the French Revolution, to secure Representative democracy, representative government in Ireland. Despairing of constitutional reform, and in defiance both of British ...

and spy for the British Government within Irish republican circles.

He was a successful lawyer in late 18th and early 19th century Dublin

Dublin is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. Situated on Dublin Bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, and is bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, pa ...

, and wrote a law book that was crucial in the development of the "beyond reasonable doubt" standard in criminal trials. However, during his time, he was best known for his popular comic operas and plays, together with his most enduring work, the romantic song " The Lass of Richmond Hill". He is now mainly remembered as a very important informer for the British government within the Irish revolutionary society, the United Irishmen

The Society of United Irishmen was a sworn association, formed in the wake of the French Revolution, to secure Representative democracy, representative government in Ireland. Despairing of constitutional reform, and in defiance both of British ...

and played a major role in the defeat of the Irish Rebellion of 1798

The Irish Rebellion of 1798 (; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ''The Turn out'', ''The Hurries'', 1798 Rebellion) was a popular insurrection against the British Crown in what was then the separate, but subordinate, Kingdom of Ireland. The m ...

. In return for payments from the government, McNally would betray his United Irishmen colleagues to the authorities and then, as defence counsel

A counsel or a counsellor at law is a person who gives advice and deals with various issues, particularly in legal matters. It is a title often used interchangeably with the title of ''lawyer''.

The word ''counsel'' can also mean advice given ...

at their trial, secretly collaborate with the prosecution to secure a conviction. His notable republican clients included Napper Tandy, Wolfe Tone

Theobald Wolfe Tone, posthumously known as Wolfe Tone (; 20 June 176319 November 1798), was a revolutionary exponent of Irish independence and is an iconic figure in Irish republicanism. Convinced that, so long as his fellow Protestantism in ...

, Robert Emmet

Robert Emmet (4 March 177820 September 1803) was an Irish Republican, orator and rebel leader. Following the suppression of the United Irish uprising in 1798, he sought to organise a renewed attempt to overthrow the British Crown and Prote ...

and Lord Edward FitzGerald

Lord Edward FitzGerald (15 October 1763 – 4 June 1798) was an Irish aristocrat and revolutionary proponent of Irish independence from Britain. He abandoned his prospects as a distinguished veteran of British service in the American War of Ind ...

.

Early life

McNally was born in Dublin in 1752, the son of a merchant and wine importer. He was raised by his mother with the support of his uncle. McNally was born into aRoman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

family, but at some point in the 1760s he converted to the Church of Ireland

The Church of Ireland (, ; , ) is a Christian church in Ireland, and an autonomy, autonomous province of the Anglican Communion. It is organised on an all-Ireland basis and is the Christianity in Ireland, second-largest Christian church on the ...

. He was passionate about theatre, entirely self-educated and initially became a merchant in Bordeaux

Bordeaux ( ; ; Gascon language, Gascon ; ) is a city on the river Garonne in the Gironde Departments of France, department, southwestern France. A port city, it is the capital of the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region, as well as the Prefectures in F ...

like his father.

However, in 1774 he went to London to study law at the Middle Temple

The Honourable Society of the Middle Temple, commonly known simply as Middle Temple, is one of the four Inns of Court entitled to Call to the bar, call their members to the English Bar as barristers, the others being the Inner Temple (with whi ...

but returned to Dublin to be called to the Irish bar in 1776. After returning to London in the late 1770s he qualified as a barrister in England, as well, in 1783. He practised for a short time in London, and, while there, supplemented his income by writing plays and editing ''The Public Ledger

''The Public Ledger'' was one of the world's longest continuously running commodity magazines. When established in 1760, it not only contained prices of commodities in London, but a wide variety of political, commercial and society news and comme ...

''.

Career

Radical lawyer

Returning to Ireland, McNally developed a successful career as a barrister in Dublin. He developed an expertise in the

Returning to Ireland, McNally developed a successful career as a barrister in Dublin. He developed an expertise in the law of evidence

The law of evidence, also known as the rules of evidence, encompasses the rules and legal principles that govern the proof of facts in a legal proceeding. These rules determine what evidence must or must not be considered by the trier of fa ...

and, in 1802, published what became a much-used textbook

A textbook is a book containing a comprehensive compilation of content in a branch of study with the intention of explaining it. Textbooks are produced to meet the needs of educators, usually at educational institutions, but also of learners ( ...

, ''The Rules of Evidence on Pleas of the Crown''. The text played a crucial role in defining and publicising the ''beyond reasonable doubt'' standard for criminal trials.

Not long after returning to Ireland, he became involved in radical politics, having already, in 1782, published a pamphlet in support of the Irish cause. He became Dublin's leading radical lawyer of the day. In 1792, he represented Napper Tandy, a radical member of the Irish Parliament, in a legal dispute over parliamentary privilege. In the early 1790s, McNally became a founder member of the United Irishmen

The Society of United Irishmen was a sworn association, formed in the wake of the French Revolution, to secure Representative democracy, representative government in Ireland. Despairing of constitutional reform, and in defiance both of British ...

, a clandestine society which soon developed into a revolutionary Irish republican organisation. He ranked high in its leadership and acted as the organisation's chief lawyer, representing many United Irishmen in court. This included defending Wolfe Tone

Theobald Wolfe Tone, posthumously known as Wolfe Tone (; 20 June 176319 November 1798), was a revolutionary exponent of Irish independence and is an iconic figure in Irish republicanism. Convinced that, so long as his fellow Protestantism in ...

and Robert Emmet

Robert Emmet (4 March 177820 September 1803) was an Irish Republican, orator and rebel leader. Following the suppression of the United Irish uprising in 1798, he sought to organise a renewed attempt to overthrow the British Crown and Prote ...

, the leaders of the 1798 and 1803 rebellions respectively, at their trials for treason. In 1793, McNally was wounded in a duel with Sir Jonah Barrington, who had insulted the United Irishmen. Barrington subsequently described McNally as "a good-natured, hospitable, talented and dirty fellow". John O'Keeffe described McNally as having "a handsome, expressive countenance and alive sparkling eyes".

Informer and government agent

After his death in 1820, it emerged that McNally had for many years been an informant for the government, and one of the most successful British spies in Irish republican circles that there has ever been. When, in 1794, a United Irishmen plot to seek aid from Revolutionary France was uncovered by the British government, McNally turned informer to save himself, although, subsequently, he also received payment for his services. McNally was paid an annual pension in respect of his work as an informer of £300 a year, from 1794 until his death in 1820.

From 1794, McNally systematically informed on his United Irishmen colleagues, who often gathered at his house for meetings. It was McNally that betrayed

After his death in 1820, it emerged that McNally had for many years been an informant for the government, and one of the most successful British spies in Irish republican circles that there has ever been. When, in 1794, a United Irishmen plot to seek aid from Revolutionary France was uncovered by the British government, McNally turned informer to save himself, although, subsequently, he also received payment for his services. McNally was paid an annual pension in respect of his work as an informer of £300 a year, from 1794 until his death in 1820.

From 1794, McNally systematically informed on his United Irishmen colleagues, who often gathered at his house for meetings. It was McNally that betrayed Lord Edward FitzGerald

Lord Edward FitzGerald (15 October 1763 – 4 June 1798) was an Irish aristocrat and revolutionary proponent of Irish independence from Britain. He abandoned his prospects as a distinguished veteran of British service in the American War of Ind ...

, one of the leaders of the 1798 rebellion, as well as Robert Emmet in 1803. A significant factor in the failure of the 1798 rebellion was the efficacious intelligence provided to the government by its agents. McNally was considered to be one of the most damaging informers.

The United Irishmen represented by McNally at their trials were invariably convicted and McNally was paid by the crown for passing the secrets of their defence to the prosecution. During the trial of Emmet, McNally provided details of the defence's strategy to the crown and conducted his client's case in a way that would assist the prosecution. For example, three days before the trial he assured the authorities that Emmet "does not intend to call a single witness, nor to trouble any witness for the Crown with a cross-examination, unless they misrepresent facts… He will not controvert the charge by calling a single witness". For his assistance to the prosecution in Emmet's case, he was paid a bonus of £200, on top of his pension, half of which was paid five days before the trial.

After McNally's death, his activities as a government agent became generally known when his heir attempted to continue to collect his pension of £300 per year. He is still remembered with opprobrium by Irish nationalists. In 1997, the Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( ; ; ) is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active in both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The History of Sinn Féin, original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur Griffit ...

newspaper, ''An Phoblacht

''An Phoblacht'' (Irish pronunciation: ; ) is a Sinn Féin-affiliated online Irish republicanism, Irish republican news platform which also publishes a quarterly print magazine format. Editorially the paper takes a Left-wing politics, left-wing ...

'' in an article on McNally, described him as "undoubtedly one of the most treacherous informers of Irish history".

Playwright and lyricist

McNally was a successful dramatist and wrote a number of well-constructed but derivative comedies, as well as comic operas. His first dramatic work was ''The Ruling Passion'', a comic opera written in 1771, and he is known to have authored at least twelve plays between 1779 and 1796 as well as other comic operas. His works include ''The Apotheosis of Punch'' (1779), a satire on the Irish playwright

McNally was a successful dramatist and wrote a number of well-constructed but derivative comedies, as well as comic operas. His first dramatic work was ''The Ruling Passion'', a comic opera written in 1771, and he is known to have authored at least twelve plays between 1779 and 1796 as well as other comic operas. His works include ''The Apotheosis of Punch'' (1779), a satire on the Irish playwright Richard Brinsley Sheridan

Richard Brinsley Butler Sheridan (30 October 17517 July 1816) was an Anglo-Irish playwright, writer and Whig politician who sat in the British House of Commons from 1780 to 1812, representing the constituencies of Stafford, Westminster and I ...

, ''Tristram Shandy'' (1783), which was an adaptation of Lawrence Sterne's novel, ''Robin Hood'' (1784), '' Fashionable Levities'' (1785), ''Richard Cœur de Lion'' (1786), and ''Critic Upon Critic'' (1788).

He also wrote a number of songs and operettas

Operetta is a form of theatre and a genre of light opera. It includes spoken dialogue, songs and including dances. It is lighter than opera in terms of its music, orchestral size, and length of the work. Apart from its shorter length, the ope ...

for Covent Garden

Covent Garden is a district in London, on the eastern fringes of the West End, between St Martin's Lane and Drury Lane. It is associated with the former fruit-and-vegetable market in the central square, now a popular shopping and tourist sit ...

. One of his songs, '' Sweet Lass of Richmond Hill'', became very well-known and popular following its first public performance at Vauxhall Gardens

Vauxhall Gardens is a public park in Kennington in the London Borough of Lambeth, England, on the south bank of the River Thames.

Originally known as New Spring Gardens, it is believed to have opened before the Restoration of 1660, being me ...

in London in 1789. It was said to be a favourite of George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland, Ireland from 25 October 1760 until his death in 1820. The Acts of Union 1800 unified Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and ...

and popularised the romantic metaphor

A metaphor is a figure of speech that, for rhetorical effect, directly refers to one thing by mentioning another. It may provide, or obscure, clarity or identify hidden similarities between two different ideas. Metaphors are usually meant to cr ...

"a rose without a thorn", a phrase which McNally had used in the song.

Personal life and family

Nothing is known of McNally's first wife Mary O'Brien, other than that she died in 1786. In London in 1787, McNally eloped with Frances I'Anson, as her father William I'Anson a solicitor, disapproved of McNally. Frances, and her family's estate, Hill House inRichmond, Yorkshire

Richmond is a market town and civil parish in North Yorkshire, England. It is located at the point where Swaledale, the upper valley of the River Swale, opens into the Vale of Mowbray. The town's population at the 2011 census was 8,413. The t ...

, was the subject of a song with lyrics by McNally and composed by James Hook, Sweet Lass of Richmond Hill. In 1795, Frances died during child birth at age 29 and was survived by only one daughter. In 1799, McNally married his third wife Louisa Edgeworth, the daughter of a clergy

Clergy are formal leaders within established religions. Their roles and functions vary in different religious traditions, but usually involve presiding over specific rituals and teaching their religion's doctrines and practices. Some of the ter ...

man from County Longford

County Longford () is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster. It is named after the town of Longford. Longford County Council is the Local government in the Republic ...

, and with his third wife he had at least three sons.

When his son, who had the same professions, died on 13 February 1820, it was widely reported to have been McNally. The son was buried in Donnybrook, Dublin

Donnybrook () is a district of Dublin, Republic of Ireland, Ireland, on the southside (Dublin), southside of the city, in the Dublin 4 postal district. It is home to the Irish public service broadcaster Raidió Teilifís Éireann (RTÉ) and wa ...

on 17 February 1820, and McNally sent a letter on 6 March 1820 (from 20 Cuffe Street

Cuffe Street (Irish language, Irish: or ) is a street in Dublin, Republic of Ireland, Ireland which runs from St Stephen's Green at the eastern end to Kevin Street Lower at the western end.

The street is intersected by Mercer Street and Monta ...

, Dublin) to the Proprietor o'Saunders's Newsletter'

seeking damages for the severe injury caused by the circulation of his death. In June 1820, McNally was on his deathbed, and although he had been a Protestant for most of his adult life, he sought

absolution

Absolution is a theological term for the forgiveness imparted by ordained Priest#Christianity, Christian priests and experienced by Penance#Christianity, Christian penitents. It is a universal feature of the historic churches of Christendom, alth ...

from a Roman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

priest, and was also buried in Donnybrook on 8 June 1820.Brief Sketches of the Parishes of Booterstown & Donneybrook in County Dublin by Rev. Beaver H. Blacker.(1860) Page 90-91

References

Bibliography

The most extensive modern study on McNally is: * See also * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:McNally, Leonard 1752 births 1820 deaths Lawyers from Dublin (city) Irish dramatists and playwrights Irish male dramatists and playwrights Irish poets Irish spies United Irishmen Burials at Donnybrook Cemetery