Leighton Durham Reynolds on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Leighton Durham Reynolds () was a British

After publishing his work on Seneca's ''Letters'', Reynolds collaborated with Nigel Guy Wilson, a Hellenist and fellow of the neighbouring Lincoln College, to produce a general introduction to the transmission of classical texts. They were tasked with this endeavour after

After publishing his work on Seneca's ''Letters'', Reynolds collaborated with Nigel Guy Wilson, a Hellenist and fellow of the neighbouring Lincoln College, to produce a general introduction to the transmission of classical texts. They were tasked with this endeavour after

Latinist

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area around Rome, Italy. Through the expansion of ...

who was known for his work on textual criticism

Textual criticism is a branch of textual scholarship, philology, and literary criticism that is concerned with the identification of textual variants, or different versions, of either manuscripts (mss) or of printed books. Such texts may rang ...

. Spending his entire teaching career at Brasenose College, Oxford

Brasenose College (BNC) is one of the Colleges of the University of Oxford, constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom. It began as Brasenose Hall in the 13th century, before being founded as a college in 1509. The l ...

, he prepared the most commonly cited edition of Seneca the Younger

Lucius Annaeus Seneca the Younger ( ; AD 65), usually known mononymously as Seneca, was a Stoicism, Stoic philosopher of Ancient Rome, a statesman, a dramatist, and in one work, a satirist, from the post-Augustan age of Latin literature.

Seneca ...

's ''Letters

Letter, letters, or literature may refer to:

Characters typeface

* Letter (alphabet), a character representing one or more of the sounds used in speech or none in the case of a silent letter; any of the symbols of an alphabet

* Letterform, the g ...

''.

The central academic achievement of Reynolds's career was his monograph ''The Medieval Tradition of Seneca's Letters'' (1965), in which he reconstructed how the text was transmitted through the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

and revealed that most of the younger manuscripts

A manuscript (abbreviated MS for singular and MSS for plural) was, traditionally, any document written by hand or typewritten, as opposed to mechanically printed or reproduced in some indirect or automated way. More recently, the term has c ...

were of little use for the establishment of the text. He also produced critical editions

Textual criticism is a branch of textual scholarship, philology, and literary criticism that is concerned with the identification of textual variants, or different versions, of either manuscripts (mss) or of printed books. Such texts may range i ...

of Seneca's ''Dialogues'', the works of the historian Sallust

Gaius Sallustius Crispus, usually anglicised as Sallust (, ; –35 BC), was a historian and politician of the Roman Republic from a plebeian family. Probably born at Amiternum in the country of the Sabines, Sallust became a partisan of Julius ...

, and Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, orator, writer and Academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises tha ...

's '' De finibus bonorum et malorum''. In 1968, Reynolds and his Oxford colleague Nigel Guy Wilson co-authored ''Scribes and Scholars: A Guide to the Transmission of Greek and Latin Literature'', a well-received introduction to textual criticism.

Writing about the set of critical editions authored by Reynolds, the Latinist Michael Reeve stated that Reynolds's scholarship had the ability "to cut through dozens of manuscripts to the serviceable core". At the time of its publication, his work on Seneca was considered by some commentators to be difficult to surpass.

Early life and education

Leighton Durham Reynolds was born on 11 February 1930 in the Welsh village of Abercanaid, south ofMerthyr Tydfil

Merthyr Tydfil () is the main town in Merthyr Tydfil County Borough, Wales, administered by Merthyr Tydfil County Borough Council. It is about north of Cardiff. Often called just Merthyr, it is said to be named after Tydfil, daughter of K ...

. His father, Edgar Reynolds, was a civil servant

The civil service is a collective term for a sector of government composed mainly of career civil service personnel hired rather than elected, whose institutional tenure typically survives transitions of political leadership. A civil service offic ...

working as a national health insurance

National health insurance (NHI), sometimes called statutory health insurance (SHI), is a system of health insurance that insures a national population against the costs of health care. It may be administered by the public sector, the private sector ...

clerk. The family of his mother, Hester Hale, had moved to Wales from the English county of Somerset

Somerset ( , ), Archaism, archaically Somersetshire ( , , ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by the Bristol Channel, Gloucestershire, and Bristol to the north, Wiltshire to the east ...

in the previous generation. William Hale, his maternal grandfather, exerted a strong influence on Reynolds during his childhood; a coal miner

Coal mining is the process of extracting coal from the ground or from a mine. Coal is valued for its energy content and since the 1880s has been widely used to generate electricity. Steel and cement industries use coal as a fuel for extrac ...

by profession, he shared with Reynolds a passion for gardening, leading his grandson to join a society for natural history

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

in Cardiff

Cardiff (; ) is the capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of Wales. Cardiff had a population of in and forms a Principal areas of Wales, principal area officially known as the City and County of Ca ...

. Supported by the naturalists Bruce Campbell

Bruce Lorne Campbell (born June 22, 1958) is an American actor and filmmaker. He is known best for his role as Ash Williams in Sam Raimi's ''Evil Dead'' horror series, beginning with the short movie '' Within the Woods'' (1978). He has also f ...

and A. E. Wade, he wrote his first publications on the birds of the Caerphilly Basin.

Reynolds attended Caerphilly Grammar School and won a scholarship to study Modern languages at The Queen's College, Oxford

The Queen's College is a constituent college of the University of Oxford, England. The college was founded in 1341 by Robert de Eglesfield in honour of Philippa of Hainault, queen of England. It is distinguished by its predominantly neoclassi ...

. Due to a short-lived regulation stipulating that holders of state scholarships attend the institution nearest to their hometown, he did not take up his place, enrolling instead at University College Cardiff

Cardiff University () is a public research university in Cardiff, Wales. It was established in 1883 as the University College of South Wales and Monmouthshire and became a founding college of the University of Wales in 1893. It was renamed Unive ...

in 1947. Reynolds initially focused on French and Italian and spent some time at the Università per Stranieri di Perugia in Italy. Influenced by the Latinist

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area around Rome, Italy. Through the expansion of ...

R. G. Austin, he increasingly turned to the study of Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

, culminating in the award of a first-class degree in 1950.

With Austin's support, Reynolds went on to obtain a scholarship for a second undergraduate degree at St John's College, Cambridge

St John's College, formally the College of St John the Evangelist in the University of Cambridge, is a Colleges of the University of Cambridge, constituent college of the University of Cambridge, founded by the House of Tudor, Tudor matriarch L ...

. He completed the Classical Tripos

The Classical Tripos is the taught course in classics at the Faculty of Classics, University of Cambridge. It is equivalent to '' Literae Humaniores'' at Oxford University. It is traditionally a three-year degree, but for those who have not previ ...

, the Classics

Classics, also classical studies or Ancient Greek and Roman studies, is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, ''classics'' traditionally refers to the study of Ancient Greek literature, Ancient Greek and Roman literature and ...

degree offered by the University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209, the University of Cambridge is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, wo ...

, in two years instead of the usual three and received several awards for his performance, including a Craven Fellowship from the university. At St John's, he made the acquaintance of Bryan Peter Reardon, an expert on Ancient Greek novels

Five ancient Greek novels or ancient Greek romances survive complete from antiquity: Chariton's '' Callirhoe'' (mid 1st century), Achilles Tatius' ''Leucippe and Clitophon'' (early 2nd century), Longus' ''Daphnis and Chloe'' (2nd century), Xenoph ...

, the Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

scholar Michael Stokes, and the Latinist John Patrick Sullivan. In 1952, after travelling to Greece, Reynolds began his national service

National service is a system of compulsory or voluntary government service, usually military service. Conscription is mandatory national service. The term ''national service'' comes from the United Kingdom's National Service (Armed Forces) Act ...

at the Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the Air force, air and space force of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. It was formed towards the end of the World War I, First World War on 1 April 1918, on the merger of t ...

, where most of his time was spent studying Russian in a programme introduced by the linguist

Linguistics is the scientific study of language. The areas of linguistic analysis are syntax (rules governing the structure of sentences), semantics (meaning), Morphology (linguistics), morphology (structure of words), phonetics (speech sounds ...

Elizabeth Hill. After completing the course, he lodged with a Russian émigré in Paris to improve his fluency in spoken Russian. He left the air force after two years with the rank of pilot officer

Pilot officer (Plt Off or P/O) is a junior officer rank used by some air forces, with origins from the Royal Air Force. The rank is used by air forces of many countries that have historical British influence.

Pilot officer is the lowest ran ...

.

Career at Oxford

In 1954, Reynolds was elected to his first academic appointment, aresearch fellowship

A research fellow is an academic research position at a university or a similar research institution, usually for list of academic ranks, academic staff or faculty members. A research fellow may act either as an independent investigator or under ...

at The Queen's College, Oxford. During his three years there, he worked mainly on the ''Letters

Letter, letters, or literature may refer to:

Characters typeface

* Letter (alphabet), a character representing one or more of the sounds used in speech or none in the case of a silent letter; any of the symbols of an alphabet

* Letterform, the g ...

'' of Seneca the Younger

Lucius Annaeus Seneca the Younger ( ; AD 65), usually known mononymously as Seneca, was a Stoicism, Stoic philosopher of Ancient Rome, a statesman, a dramatist, and in one work, a satirist, from the post-Augustan age of Latin literature.

Seneca ...

, which would later form the basis of his reputation as a Latinist. In this period, he came under the influence of three textual critics working at Oxford: Neil Ripley Ker

Neil Ripley Ker (; 1908–1982) was a scholar of Anglo-Saxon literature. He was Reader in Palaeography at the University of Oxford and a fellow of Magdalen College, Oxford until he retired in 1968. He is known especially for his ''Catalogue of M ...

, Richard William Hunt

Richard William Hunt (11 April 1908 – 13 November 1979) was a scholar, grammarian, palaeographer, editor, and author of a number of books about medieval history. He began his career as a lecturer in palaeography at Liverpool University, an ...

, and R. A. B. Mynors, the senior chair of Latin at the university. They encouraged him to study the transmission of the text of Seneca.

The post of Classics tutor at Brasenose College, Oxford

Brasenose College (BNC) is one of the Colleges of the University of Oxford, constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom. It began as Brasenose Hall in the 13th century, before being founded as a college in 1509. The l ...

, had fallen vacant after its incumbent, Maurice Platnauer

Maurice Platnauer (18 June 1887 – 19 December 1974) was Principal of Brasenose College, Oxford, from 1956 to 1960.

Platnauer was educated at Shrewsbury School and New College, Oxford. A classicist, he was a master at Winchester College from 1 ...

, had become the college's new Principal. In 1957, after the end of his research fellowship, Reynolds was selected as Platnauer's replacement and duly elected to a tutorial fellowship. He was also appointed a University Lecturer in Greek and Latin Literature. He held both appointments for the rest of his academic career. Reynolds played an active part in the college's governing body, where, according to the Brasenose fellow and chemist Graham Richards, he "held a position of quiet authority". From 1985 to 1987, he served as Vice-Principal and, in 1997, as acting Principal of the college. He supported Brasenose's decision to become the first all-male college of the university to admit female students. In 1996 he was raised to the rank of a professor.

In 1962, he married Susan Mary Buchanan, an optometrist

Optometry is the healthcare practice concerned with examining the eyes for visual defects, prescribing corrective lenses, and detecting eye abnormalities.

In the United States and Canada, optometrists are those that hold a post-baccalaureate f ...

and daughter of the Scottish town planner Colin Buchanan. Their wedding reception was held at Brasenose College, where Reynolds was jokingly given an ''exeat

The Latin word ''exeat'' ("he/she may leave") is most commonly used to describe a period of absence from a centre of learning.Boars Hill

Boars Hill is a hamlet southwest of Oxford, straddling the boundary between the civil parishes of Sunningwell and Wootton. It consists of about 360 dwellings spread over an area of nearly two square miles as shown on thimapfrom the long establ ...

near Oxford, which they later bought from the college. Reynolds and his wife had two daughters and a son.

Reynolds was elected a Fellow of the British Academy

Fellowship of the British Academy (post-nominal letters FBA) is an award granted by the British Academy to leading academics for their distinction in the humanities and social sciences. The categories are:

# Fellows – scholars resident in t ...

in 1987. Over the course of his career, he held a number of visiting fellowships and professorships; he spent periods at the University of Texas at Austin

The University of Texas at Austin (UT Austin, UT, or Texas) is a public university, public research university in Austin, Texas, United States. Founded in 1883, it is the flagship institution of the University of Texas System. With 53,082 stud ...

, the Institute for Advanced Study

The Institute for Advanced Study (IAS) is an independent center for theoretical research and intellectual inquiry located in Princeton, New Jersey. It has served as the academic home of internationally preeminent scholars, including Albert Ein ...

at Princeton

Princeton University is a private Ivy League research university in Princeton, New Jersey, United States. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the Unit ...

(twice), and at Cornell University

Cornell University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university based in Ithaca, New York, United States. The university was co-founded by American philanthropist Ezra Cornell and historian and educator Andrew Dickson W ...

(twice). From 1975 to 1987, he was co-editor of ''The Classical Review

''The'' is a grammatical article in English, denoting nouns that are already or about to be mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in English. ''The ...

''.

Retirement and death

Reynolds retired from his teaching duties in 1997, one year after being appointed to a professorship. Around this time, he was diagnosed with cancer. In an obituary in the ''Proceedings of the British Academy

The ''Proceedings of the British Academy'' is a series of academic volumes on subjects in the humanities and social sciences. The first volume was published in 1905. Up to 1991, the volumes (appearing annually from 1927) mostly consisted of the te ...

'', the Latinist Michael Winterbottom

Michael Winterbottom (born 29 March 1961) is an English film director. He began his career working in British television before moving into features. Three of his films—''Welcome to Sarajevo'', ''Wonderland (1999 film), Wonderland'' and ''24 ...

wrote that Reynolds underwent oncological surgery in 1995 and was later treated at Churchill Hospital

The Churchill Hospital is a teaching hospital in Oxford, England. It is managed by the Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust.

History

The original hospital on the site was built in 1940 with the intention of providing medical aid to ...

, Oxford. According to the Hellenist Nigel Guy Wilson, the diagnosis was made only in 1999 with Reynolds opting for palliative treatment. He died on 4 December 1999 in Oxford.

Contributions to scholarship

Seneca's ''Letters''

In the application for his position at Brasenose, Reynolds wrote that he had been working on the textual transmission of Seneca the Younger's ''Letters'', and that he aimed to publish a newcritical edition

Textual criticism is a branch of textual scholarship, philology, and literary criticism that is concerned with the identification of textual variants, or different versions, of either manuscripts (mss) or of printed books. Such texts may range i ...

of the text together with a general survey of the topic. While conducting this research, he had travelled extensively in Europe to study the relevant manuscripts

A manuscript (abbreviated MS for singular and MSS for plural) was, traditionally, any document written by hand or typewritten, as opposed to mechanically printed or reproduced in some indirect or automated way. More recently, the term has c ...

. In 1965, he published the results of his work: an edition of the ''Letters'' in the Oxford Classical Texts

Oxford Classical Texts (OCT), or Scriptorum Classicorum Bibliotheca Oxoniensis, is a series of books published by Oxford University Press. It contains texts of ancient Greek and Latin literature, such as Homer's ''Odyssey'' and Virgil's ''Aeneid'' ...

series and a monograph

A monograph is generally a long-form work on one (usually scholarly) subject, or one aspect of a subject, typically created by a single author or artist (or, sometimes, by two or more authors). Traditionally it is in written form and published a ...

entitled ''The Medieval Tradition of Seneca's Letters''.

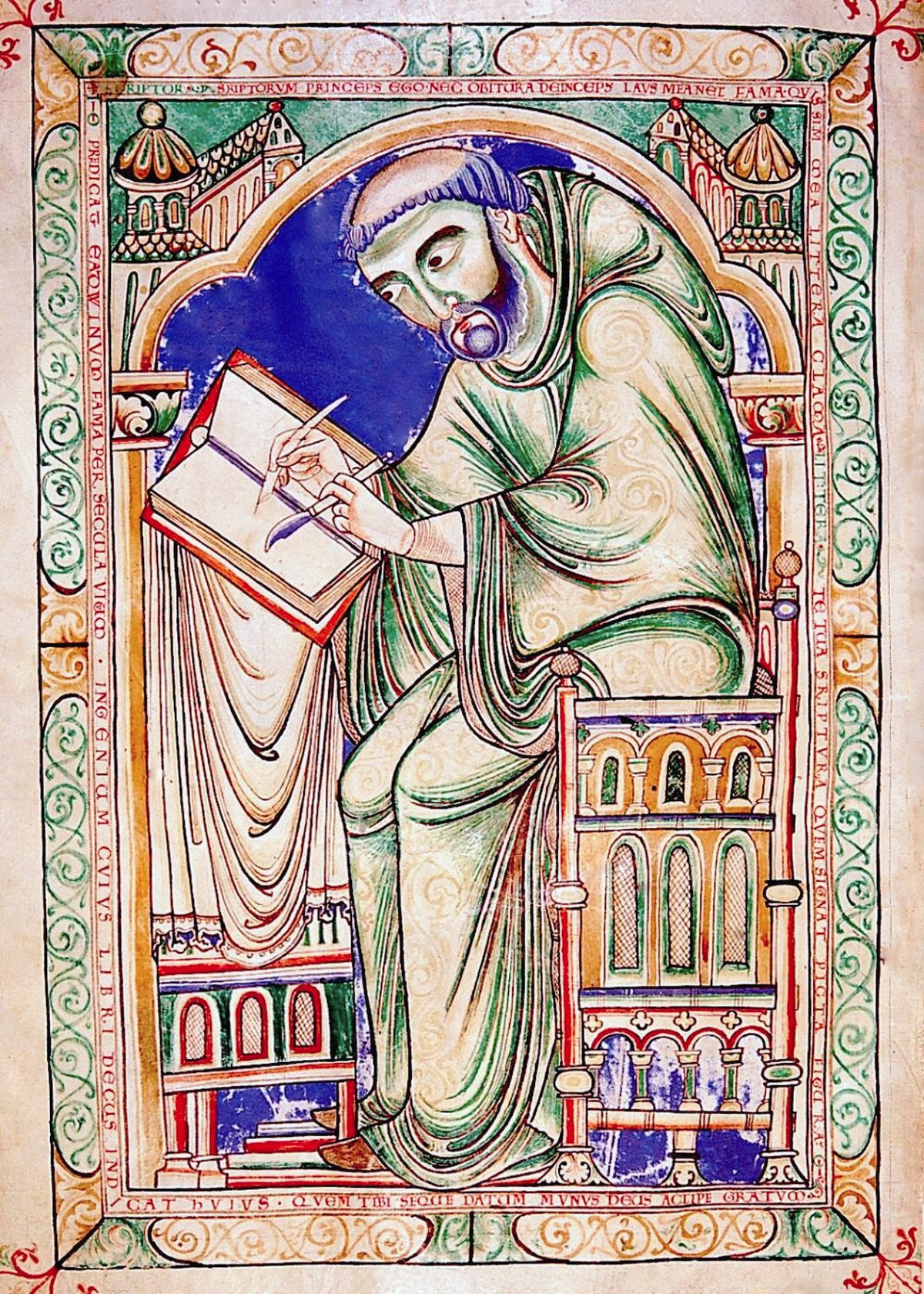

Reynolds set out to answer two central questions regarding the medieval manuscripts of the ''Letters'': how authoritative are the 'younger' manuscripts, written after the 12th century, in establishing the text, and how do they relate to the older segment of the tradition? For ''Letters'' 1–88, which were transmitted separately, he elaborated the stemma introduced by the German philologist Otto Foerster. Reynolds established a transmission in three distinct branches (p, α, γ) in which α and γ characteristically offer common readings. He demonstrated more thoroughly than his predecessor how the younger manuscripts descended through the γ branch. This breakthrough in particular is described by the classicist Gregor Maurach as the result of time-consuming scholarly groundwork.

The transmission of ''Letters'' 89–124 depends on a much narrower manuscript base which he sought to supplement. Previously, three individual manuscripts had been considered the key textual witnesses (B, Q, p); Reynolds showed that p and Q were in fact representatives of larger groups of manuscripts comprising several more recent manuscripts. This part of his research drew praise from reviewers, with the classicist B. L. Hijmans commenting that its method of reconstruction would "be very useful in seminars on textual criticism". Reynolds's concluding remarks about the younger manuscripts stated that, with few exceptions, "they have no contribution to make to the reconstruction of the text". Writing for ''The Classical Review'', the Latinist E. J. Kenney said that this conclusion was "an altogether Herculean feat" but added that it "hardly prepare readers for the large role these manuscripts played in editions of the ''Letters''.

Appearing in two volumes, Reynolds's edition of the ''Letters'' was based on the results of his monograph. For Kenney, the edition displayed "almost constantly sound" judgement of textual problems and had a critical apparatus

A critical apparatus () in textual criticism of primary source material, is an organized system of notations to represent, in a single text, the complex history of that text in a concise form useful to diligent readers and scholars. The apparatu ...

without "serious inconsistencies". Although he criticised a number of editorial aspects, he concluded by writing that " eynolds'sedition will surely be for a long time to come the standard text of this undervalued work". Hijmans expressed a similar opinion while stating that Reynolds's work may not have provided the final assessment of all available manuscripts.

Further critical editions

In 1977, Reynolds published a critical edition of Seneca's ''Dialogues''. Having identified the ''Codex Ambrosianus'' (A) as the most important source of the text, he relied heavily on it and drew on the readings of younger manuscripts only where A showed signs of corruption. For Latinist D. R. Shackleton Bailey, the result was a text which surpassed that published in 1905 by the German scholar Emil Hermes. Shackleton Bailey further stated that "it seems unlikely that eynolds's textcan ever be greatly bettered". According to the reviewer Daniel Knecht, Reynolds was more willing than previous editors to posit cruces in places where the text was irremediably corrupt and to delete passages he considered inauthentic. Reynolds continued his work on Latin prose authors in 1991 with an edition of the collected works of the Roman historianSallust

Gaius Sallustius Crispus, usually anglicised as Sallust (, ; –35 BC), was a historian and politician of the Roman Republic from a plebeian family. Probably born at Amiternum in the country of the Sabines, Sallust became a partisan of Julius ...

. At that time, the standard text had been a 1954 edition by Alfons Kurfess in the Bibliotheca Teubneriana

The Bibliotheca Teubneriana, or ''Bibliotheca Scriptorum Graecorum et Romanorum Teubneriana'', also known as Teubner editions of Greek and Latin texts, comprise one of the most thorough modern collections published of ancient (and some medieval ...

series. Reynolds innovated by limiting himself to reporting five manuscripts in passages where Kurfess had provided unnecessary detail. For Stephen Oakley

Stephen Phelps Oakley, FBA (born 20 November 1958) is a British classicist and academic. An expert on the work of Livy, he is the ninth Kennedy Professor of Latin at the University of Cambridge and a Fellow of Emmanuel College.

Early life an ...

, the Kennedy Professor of Latin

The Kennedy Professorship of Latin is the senior professorship of Latin at the University of Cambridge.

In 1865, when Benjamin Hall Kennedy retired as headmaster of Shrewsbury School

Shrewsbury School is a Public school (United Kingdom), pu ...

at Cambridge, the greatest merit of the edition was its judicious provision of readings from less reliable manuscripts, which has led to the solution of a difficult textual problem in chapter 114 of Sallust's ''Jugurtha

Jugurtha or Jugurthen (c. 160 – 104 BC) was a king of Numidia, the ancient kingdom of the Numidians in northwest Africa. When the Numidian king Micipsa, who had adopted Jugurtha, died in 118 BC, Micipsa's two sons, Hiempsal and Adherbal ...

''. The classicist Stephen Shierling considered the differences between the editions of Kurfess and Reynolds of "modest importance" but said the new text was "cleaner and more consistent".

Published in 1998, the final critical edition of his career covered Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, orator, writer and Academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises tha ...

's philosophical text '' De finibus bonorum et malorum''. This work had been edited competently by the Danish classical scholar Johan Nicolai Madvig

Johan Nicolai Madvig (; 7 August 1804 – 12 December 1886), was a Danish philologist and Kultus Minister.

Life

Madvig was born on the Danish island of Bornholm, south of Sweden. He was educated at the classical school of Frederiksborg and th ...

in 1839 but technological and methodological advances had necessitated a new rendition of the text. Reynolds remodelled the stemma by defining two principal transmission groups (α and φ) to which all available manuscripts belong. In addition to a concise critical apparatus, he fitted the text with a secondary apparatus providing background information on the philosophical concepts discussed.

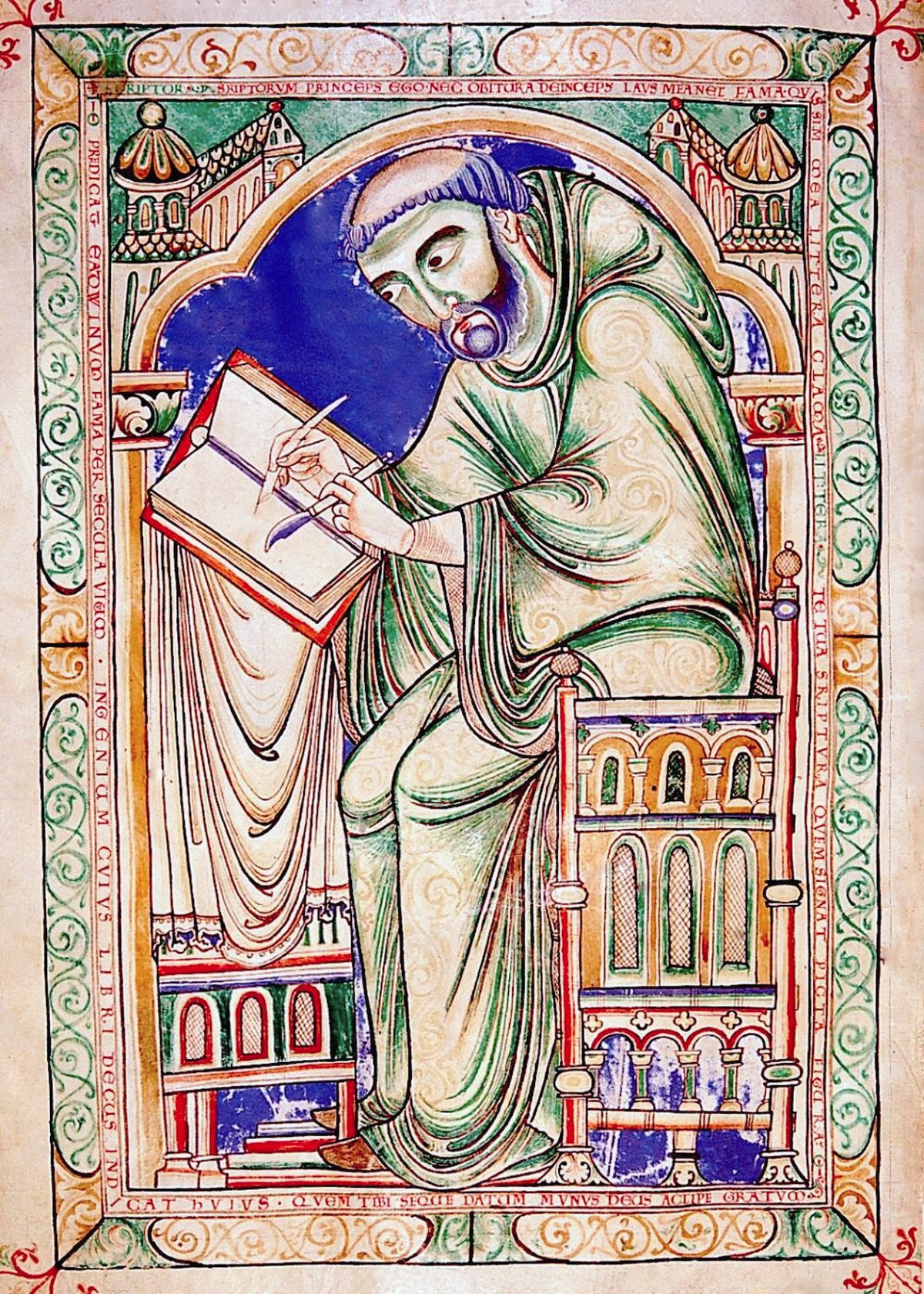

''Scribes and Scholars''

After publishing his work on Seneca's ''Letters'', Reynolds collaborated with Nigel Guy Wilson, a Hellenist and fellow of the neighbouring Lincoln College, to produce a general introduction to the transmission of classical texts. They were tasked with this endeavour after

After publishing his work on Seneca's ''Letters'', Reynolds collaborated with Nigel Guy Wilson, a Hellenist and fellow of the neighbouring Lincoln College, to produce a general introduction to the transmission of classical texts. They were tasked with this endeavour after Oxford University Press

Oxford University Press (OUP) is the publishing house of the University of Oxford. It is the largest university press in the world. Its first book was printed in Oxford in 1478, with the Press officially granted the legal right to print books ...

had been made aware of the need for such a book. Their joint volume was published in 1968 as ''Scribes and Scholars: A Guide to the Transmission of Greek and Latin Literature''. The book appeared in two further editions (1974 and 1991) and was translated into Italian, French, Greek, Spanish, and Japanese. The book contained chapters on the afterlife of classical texts in antiquity, the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

, and the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

; the last chapter discussed modern textual criticism.

''Scribes and Scholars'' was met with enthusiastic reviews from the scholarly world. The Hellenist Patricia Easterling considered it to have achieved its aim of providing a general introduction with "striking success". She commented that the book had "one serious drawback: its scholarship is so good that more advanced students will also want to use it, and for them it will be frustrating to find that there are no footnotes". The philologist Conor Fahy termed it an "excellent short manual" though he criticised the authors' assertion that Greek was the only language spoken in Southern Italy and Sicily during the Middle Ages. For the reviewer Wolfgang Hörmann, the book constituted "a work of art in its own way" (). Commenting on the final chapter on modern textual criticism, he praised Reynolds and Wilson for avoiding the common pitfall of forcing the discipline into a rigid methodological system.

Legacy

Reynolds's reputation as a scholar rests on his contributions to textual criticism. In an obituary for ''The Independent

''The Independent'' is a British online newspaper. It was established in 1986 as a national morning printed paper. Nicknamed the ''Indy'', it began as a broadsheet and changed to tabloid format in 2003. The last printed edition was publis ...

'', the Latinist Michael Reeve wrote that Reynolds's scholarship had the ability "to cut through dozens of manuscripts to the serviceable core". ''Scribes and Scholars'', the introduction to textual criticism co-authored with Wilson, was described by Reeve as "the kind of book that one simply cannot imagine not being there". Even though his scholarship on Seneca was at the time of its publication considered by some commentators to be insurpassable, Winterbottom considers the transmission of the ''Letters'' much more open than Reynolds envisaged. As of 2001, his text was nonetheless still consulted as the standard edition. Writing in 2019 for the bibliographical repository ''Oxford Bibliographies Online

Oxford Bibliographies Online (OBO), also known as Oxford Bibliographies, is a web-based compendium of peer-reviewed annotated bibliographies and short encyclopedia entries maintained by Oxford University Press.

History

Oxford Bibliographies Onl ...

'', the Seneca scholars Ermanno Malaspina, Jula Wildberger, and Veronica Revello named Reynolds's editions as "the best and most cited" texts of Seneca's works.

Publications

The following monographs and editions were written by Reynolds: * Reynolds, L. D. (1965). ''L. Annaei Senecae Ad Lucilium Epistulae Morales''. 2 Volumes. Oxford: Oxford University Press * * * * * * Reynolds also published the following articles or chapters: * * * * * * * * * *Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Reynolds, Leighton Durham 1930 births 1999 deaths British Latinists Fellows of Brasenose College, Oxford Alumni of St John's College, Cambridge Fellows of the British Academy Alumni of Cardiff University Università per Stranieri di Perugia alumni People from Merthyr Tydfil County Borough British classical scholars Welsh scholars and academics