Legbiter on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Magnus III Olafsson (

The strongman behind Haakon's monarchy had been his foster-father Tore Tordsson ("Steigar-Tore"), who refused to recognise Magnus as king after Haakon's death. With Egil Aslaksson and other noblemen, he had the otherwise-unknown Sweyn Haraldsson set up as a

The strongman behind Haakon's monarchy had been his foster-father Tore Tordsson ("Steigar-Tore"), who refused to recognise Magnus as king after Haakon's death. With Egil Aslaksson and other noblemen, he had the otherwise-unknown Sweyn Haraldsson set up as a

After his arrival, Magnus began negotiations with Scottish and Irish kings about the ''hird'' and control of land in Scotland, Ireland and the surrounding islands. Upon arriving in Orkney, he sent the earls

After his arrival, Magnus began negotiations with Scottish and Irish kings about the ''hird'' and control of land in Scotland, Ireland and the surrounding islands. Upon arriving in Orkney, he sent the earls  In Scotland internal fighting continued between rival kings, although King

In Scotland internal fighting continued between rival kings, although King

According to Randi Helene Førsund, the Norwegians in Kållandsö appear to have been characterized by arrogance (perhaps due to their successes under Magnus) and taunted the Swedish king for taking so long to arrive. After newly formed ice connected the island to the mainland, Inge arrived with about 3,000 men. Although he offered several times to allow the Norwegians to return home in peace (with their plunder and possessions), Inge's offers were rejected. The Swedes finally attacked, burning the fort. The Norwegians were spared and allowed to return home, after being beaten with sticks and surrendering all their possessions. Angry at the humiliating defeat, Magnus planned revenge. He entered Sweden the following year, reconquering the same areas. During the hasty campaign Magnus and his men were ambushed by Swedish forces and forced to flee back to their ships, suffering heavy losses. The war continued until 1100 or 1101.

Danish king Eric Evergood, concerned that the conflict would escalate, began peace talks between the two kings. Relations had been strained between Denmark and Norway after Magnus's 1096 raids into Halland, and Eric feared that the conflict might spill over into his own country. The three Scandinavian kings eventually agreed to negotiate peace in the border area near Göta älv. After a constructive meeting, they agreed to preserve ancestral borders; by marrying Inge's daughter

According to Randi Helene Førsund, the Norwegians in Kållandsö appear to have been characterized by arrogance (perhaps due to their successes under Magnus) and taunted the Swedish king for taking so long to arrive. After newly formed ice connected the island to the mainland, Inge arrived with about 3,000 men. Although he offered several times to allow the Norwegians to return home in peace (with their plunder and possessions), Inge's offers were rejected. The Swedes finally attacked, burning the fort. The Norwegians were spared and allowed to return home, after being beaten with sticks and surrendering all their possessions. Angry at the humiliating defeat, Magnus planned revenge. He entered Sweden the following year, reconquering the same areas. During the hasty campaign Magnus and his men were ambushed by Swedish forces and forced to flee back to their ships, suffering heavy losses. The war continued until 1100 or 1101.

Danish king Eric Evergood, concerned that the conflict would escalate, began peace talks between the two kings. Relations had been strained between Denmark and Norway after Magnus's 1096 raids into Halland, and Eric feared that the conflict might spill over into his own country. The three Scandinavian kings eventually agreed to negotiate peace in the border area near Göta älv. After a constructive meeting, they agreed to preserve ancestral borders; by marrying Inge's daughter

Magnus Barefoot's saga

' (in ''Heimskringla''). English translation: Samuel Laing (London, 1844). *

The Ancient History of the Norwegian Kings

'. English translation: David and Ian McDougall (London, 1998). *

Ágrip af Nóregskonungasögum

' (c. 1180s). English translation: M. J. Driscoll (London, 2008). *

' (c. 1262). English translation: Rev. Goss (Douglas, 1874). *

Fagrskinna

' (c. 1220s), in Old Norse. Edited by Finnur Jónsson (Copenhagen, 1902). *

Morkinskinna

' (c. 1220s), in Old Norse. Edited by Finnur Jónsson (Copenhagen, 1932). *

' (c. 1230). English translation: George W. Dasent (London, 1894). *

Annals of Inisfallen

'. English translation (2008). *

'. English translation (2013). *

Annales Cambriæ

', in Latin. Edited by John Williams ab Ithel (London, 1860). *

Brut y Tywysogion

'. English translation: John Williams ab Ithel (1860). Books * * * * * * * * Journals * * * * * *

Old Norse

Old Norse, also referred to as Old Nordic or Old Scandinavian, was a stage of development of North Germanic languages, North Germanic dialects before their final divergence into separate Nordic languages. Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants ...

: ''Magnús Óláfsson'', Norwegian: ''Magnus Olavsson''; 1073 – 24 August 1103), better known as Magnus Barefoot (Old Norse: ''Magnús berfœttr'', Norwegian: ''Magnus Berrføtt''), was the King of Norway

The Norwegian monarch is the head of state of Norway, which is a constitutional and hereditary monarchy with a parliamentary system. The Norwegian monarchy can trace its line back to the reign of Harald Fairhair and the previous petty king ...

from 1093 until his death in 1103. His reign was marked by aggressive military campaigns and conquest, particularly in the Norse-dominated parts of the British Isles

The British Isles are an archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner Hebrides, Inner and Outer Hebr ...

, where he extended his rule to the Kingdom of the Isles

The Kingdom of the Isles, also known as Sodor, was a Norse–Gaelic kingdom comprising the Isle of Man, the Hebrides and the islands of the Clyde from the 9th to the 13th centuries. The islands were known in Old Norse as the , or "Southern I ...

and Dublin

Dublin is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. Situated on Dublin Bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, and is bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, pa ...

.

As the only son of King Olaf Kyrre

Olaf III or Olaf Haraldsson (Old Norse: ''Óláfr Haraldsson'', Norwegian: ''Olav Haraldsson''; – 22 September 1093), known as Olaf the Peaceful (Old Norse: ''Óláfr kyrri'', Norwegian: ''Olav Kyrre''), was King of Norway from 1067 until hi ...

, Magnus was proclaimed king in southeastern Norway shortly after his father's death in 1093. In the north his claim was contested by his cousin, Haakon Magnusson (son of King Magnus Haraldsson), and the two co-ruled uneasily until Haakon's death in 1095. Disgruntled members of the nobility refused to recognise Magnus after his cousin's death, but the insurrection was short-lived. After securing his position domestically, Magnus campaigned around the Irish Sea

The Irish Sea is a body of water that separates the islands of Ireland and Great Britain. It is linked to the Celtic Sea in the south by St George's Channel and to the Inner Seas off the West Coast of Scotland in the north by the North Ch ...

from 1098 to 1099. He raided through Orkney

Orkney (), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago off the north coast of mainland Scotland. The plural name the Orkneys is also sometimes used, but locals now consider it outdated. Part of the Northern Isles along with Shetland, ...

, the Hebrides

The Hebrides ( ; , ; ) are the largest archipelago in the United Kingdom, off the west coast of the Scotland, Scottish mainland. The islands fall into two main groups, based on their proximity to the mainland: the Inner Hebrides, Inner and Ou ...

and Mann

Mann may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media

* ''Mann'' (film), a 1999 Indian Hindi-language romantic drama

* Mann (chess), a variant chess piece

* ''Mann'' (magazine), a Norwegian magazine

* Mann (rapper), Dijon Shariff Thames (born 19 ...

(the Northern and Southern Isles), and ensured Norwegian control by a treaty with the Scottish king. Based on Mann during his time in the west, Magnus had a number of forts and houses built on the island and probably also obtained suzerainty of Galloway

Galloway ( ; ; ) is a region in southwestern Scotland comprising the counties of Scotland, historic counties of Wigtownshire and Kirkcudbrightshire. It is administered as part of the council areas of Scotland, council area of Dumfries and Gallow ...

. He sailed to Wales later in his expedition, gaining the support of Anglesey

Anglesey ( ; ) is an island off the north-west coast of Wales. It forms the bulk of the Principal areas of Wales, county known as the Isle of Anglesey, which also includes Holy Island, Anglesey, Holy Island () and some islets and Skerry, sker ...

(and the Gwynedd

Gwynedd () is a county in the north-west of Wales. It borders Anglesey across the Menai Strait to the north, Conwy, Denbighshire, and Powys to the east, Ceredigion over the Dyfi estuary to the south, and the Irish Sea to the west. The ci ...

) after aiding against the invading Norman forces from the island.

Following his return to Norway, Magnus led campaigns into Dalsland

Dalsland () is a Swedish traditional province, or ''landskap'', situated in Götaland in southern Sweden. Lying to the west of Lake Vänern, it is bordered by Värmland to the north, Västergötland to the southeast, Bohuslän to the west, ...

and Västergötland

Västergötland (), also known as West Gothland or the Latinized version Westrogothia in older literature, is one of the 25 traditional non-administrative provinces of Sweden (''landskap'' in Swedish), situated in the southwest of Sweden.

Vä ...

in Sweden, claiming an ancient border with the country. After two unsuccessful invasions and a number of skirmishes Danish king Eric Evergood initiated peace talks among the three Scandinavian monarchs, fearing that the conflict would get out of hand. Magnus concluded peace with the Swedes in 1101 by agreeing to marry Margaret

Margaret is a feminine given name, which means "pearl". It is of Latin origin, via Ancient Greek and ultimately from Iranian languages, Old Iranian. It has been an English language, English name since the 11th century, and remained popular thro ...

, daughter of the Swedish king Inge Stenkilsson. In return, Magnus gained Dalsland as part of her dowry. He set out on his final western campaign in 1102, and may have sought to conquer Ireland. Magnus entered into an alliance with Irish king Muirchertach Ua Briain

Muirchertach Ua Briain (anglicised as Murtaugh O'Brien; c. 1050 – c. 10 March 1119), son of Toirdelbach Ua Briain and great-grandson of Brian Boru, was King of Munster and later self-declared High King of Ireland.

Background and early career ...

of Munster

Munster ( or ) is the largest of the four provinces of Ireland, located in the south west of the island. In early Ireland, the Kingdom of Munster was one of the kingdoms of Gaelic Ireland ruled by a "king of over-kings" (). Following the Nor ...

, who recognised Magnus's control of Dublin. Under unclear circumstances, while obtaining food supplies for his return to Norway, Magnus was killed in an ambush by the Ulaid

(Old Irish, ) or (Irish language, Modern Irish, ) was a Gaelic Ireland, Gaelic Provinces of Ireland, over-kingdom in north-eastern Ireland during the Middle Ages made up of a confederation of dynastic groups. Alternative names include , which ...

the next year; territorial advances characterising his reign ended with his death.

Into modern times, his legacy has remained more pronounced in Ireland and Scotland than in his native Norway. Among the few domestic developments known during his reign, Norway developed a more centralised rule and moved closer to the European model of church organisation. Popularly portrayed as a Viking

Vikings were seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway, and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded, and settled throughout parts of Europe.Roesdahl, pp. 9� ...

warrior rather than a medieval monarch, Magnus was the last Norwegian king to fall in battle abroad, and he may in some respects be considered the final Viking king.

Background

Most information about Magnus is gleaned from Norsesaga

Sagas are prose stories and histories, composed in Iceland and to a lesser extent elsewhere in Scandinavia.

The most famous saga-genre is the (sagas concerning Icelanders), which feature Viking voyages, migration to Iceland, and feuds between ...

s and chronicles, which began appearing during the 12th century. The most important sources still available are the Norwegian chronicles ''Historia de Antiquitate Regum Norwagiensium'' by Theodoric the Monk

Theodoric the Monk (; also ''Tjodrik munk''; in Old Norse his name was most likely ''Þórir'') was a 12th-century Norwegian Benedictine monk, perhaps at the Nidarholm Abbey. He may be identical with either Bishop Thorfinn of Hamar, Tore of the An ...

and the anonymous ''Ágrip af Nóregskonungasögum

( Icelandic for "''Summary of the Norwegian Kings' Sagas''"), often shortened to ''Ágrip'', is a history of the kings of Norway. Written in Old Norse, it is, along with the '' Historia Norvegiæ'', one of the Norwegian synoptic histories.

The ...

'' (or simply ''Ágrip'') from the 1180s and the Iceland

Iceland is a Nordic countries, Nordic island country between the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic and Arctic Oceans, on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge between North America and Europe. It is culturally and politically linked with Europe and is the regi ...

ic sagas ''Heimskringla

() is the best known of the Old Norse kings' sagas. It was written in Old Norse in Iceland. While authorship of ''Heimskringla'' is nowhere attributed, some scholars assume it is written by the Icelandic poet and historian Snorri Sturluson (117 ...

'' (by Snorri Sturluson

Snorri Sturluson ( ; ; 1179 – 22 September 1241) was an Icelandic historian, poet, and politician. He was elected twice as lawspeaker of the Icelandic parliament, the Althing. He is commonly thought to have authored or compiled portions of th ...

), ''Morkinskinna

''Morkinskinna'' is an Old Norse kings' saga, relating the history of Norwegian kings from approximately 1025 to 1157. The saga was written in Iceland around 1220, and has been preserved in a manuscript from around 1275.

The name ''Morkinskinn ...

'' and ''Fagrskinna

''Fagrskinna'' ( ; ; trans. "Fair Leather" from the type of parchment) is one of the kings' sagas, written around 1220. It is assumed to be a source for what is known as the '' Heimskringla'', containing histories of Norwegian kings from the 9th ...

'', which date to about the 1220s. While the later sagas are the most detailed accounts, they are also generally considered the least reliable. Additional information about Magnus, in particular his campaigns, is found in sources from the British Isles, which included contemporary accounts.

Magnus was born around the end of 1073 as the only son of King Olaf Kyrre

Olaf III or Olaf Haraldsson (Old Norse: ''Óláfr Haraldsson'', Norwegian: ''Olav Haraldsson''; – 22 September 1093), known as Olaf the Peaceful (Old Norse: ''Óláfr kyrri'', Norwegian: ''Olav Kyrre''), was King of Norway from 1067 until hi ...

. His mother's identity is uncertain; she is identified as Tora Arnesdatter (daughter of otherwise-unknown Arne Låge) in ''Morkinskinna'' and ''Fagrskinna'', as Tora Joansdatter in ''Heimskringla'', '' Hrokkinskinna'' and '' Hryggjarstykki''Førsund (2012) p. 14 and an unnamed daughter of "Ragnvald jarl" from Godøy, Sunnmøre

Sunnmøre (, ) is the southernmost traditional district of the western Norwegian county of Møre og Romsdal. Its main city is Ålesund. The region comprises the municipalities () of Fjord, Giske, Hareid, Herøy, Sande, Haram, Stranda Mu ...

in the genealogical text ''Af en gl. ætleg'' (commonly known as ''Sunnmørsættleggen''). The historical consensus (including P. A. Munch

Peter Andreas Munch (15 December 1810 – 25 May 1863), usually known as P. A. Munch, was a Norwegian historian, known for his work on the medieval history of Norway. Munch's scholarship included Norwegian archaeology, geography, ethnography, ...

and Claus Krag

Claus Krag (born April 21, 1943) is a Norwegian educator, historian, and writer. He is a noted specialist in Old Norse

Old Norse, also referred to as Old Nordic or Old Scandinavian, was a stage of development of North Germanic languages ...

) has favoured Tora Arnesdatter, but the other claims have also gained support. Anders Stølen has argued that she was a daughter of Ragnvald jarl (who has been identified as Rognvald Brusason Ragnvald, Rögnvald or Rognvald or Rægnald is an Old Norse name (Old Norse ''Rǫgnvaldr'', modern Icelandic ''Rögnvaldur''; in Old English ''Regenweald'' and in Old Irish, Middle Irish '' Ragnall''). Notable people with the name include:

* Ragnva ...

, Earl of Orkney

Earl of Orkney, historically Jarl of Orkney, is a title of nobility encompassing the archipelagoes of Orkney and Shetland, which comprise the Northern Isles of Scotland. Originally Scandinavian Scotland, founded by Norse invaders, the status ...

by Ola Kvalsund), while historian Randi Helene Førsund has considered Tora Joansdatter more likely.

Magnus grew up among the ''hird

The hird (also named "De Håndgangne Menn" in Norwegian), in Scandinavian history, was originally an informal retinue of personal armed companions, hirdmen or housecarls. Over time, it came to mean not only the nucleus ('Guards') of the royal arm ...

'' (royal retinue) of his father in Nidaros

Nidaros, Niðarós or Niðaróss () was the medieval name of Trondheim when it was the capital of Norway's first Christian kings. It was named for its position at the mouth (Old Norse: ''óss'') of the River Nid (the present-day Nidelva).

Althou ...

(modern Trondheim

Trondheim ( , , ; ), historically Kaupangen, Nidaros, and Trondhjem (), is a city and municipality in Trøndelag county, Norway. As of 2022, it had a population of 212,660. Trondheim is the third most populous municipality in Norway, and is ...

), ''de facto'' capital of Norway at the time. His father's cousin, the chieftain Tore Ingeridsson, was foster-father to Magnus. In his youth, he was apparently more similar to his warlike grandfather, King Harald Hardrada

Harald Sigurdsson (; – 25 September 1066), also known as Harald III of Norway and given the epithet ''Hardrada'' in the sagas, was List of Norwegian monarchs, King of Norway from 1046 to 1066. He unsuccessfully claimed the Monarchy of Denma ...

, than to his father (who bore the byname

An epithet (, ), also a byname, is a descriptive term (word or phrase) commonly accompanying or occurring in place of the name of a real or fictitious person, place, or thing. It is usually literally descriptive, as in Alfred the Great, Suleima ...

''Kyrre'': "the Peaceful"). According to Snorri Sturluson, Magnus was considered handsome and gifted in learning; although he was shorter in stature than his grandfather Harald, he was reportedly known as "Magnus the Tall". Magnus's more-common byname, "Barefoot" or "Barelegs", was—according to Snorri—due to his adopting the Gaelic

Gaelic (pronounced for Irish Gaelic and for Scots Gaelic) is an adjective that means "pertaining to the Gaels". It may refer to:

Languages

* Gaelic languages or Goidelic languages, a linguistic group that is one of the two branches of the Insul ...

dress of the Irish and Scots: a short tunic, which left the lower legs bare. Another version (by Danish historian Saxo Grammaticus

Saxo Grammaticus (), also known as Saxo cognomine Longus, was a Danish historian, theologian and author. He is thought to have been a clerk or secretary to Absalon, Archbishop of Lund, the main advisor to Valdemar I of Denmark. He is the author ...

) maintains that he acquired the nickname because he was forced to flee from a Swedish attack in his bare feet, while a third explains that he rode barefoot (like the Irish). Due to Magnus's aggressive nature and his campaigns abroad, he also had the nickname ''styrjaldar-Magnús'' ("Warrior Magnus" or "Magnus the Strife-lover").''Magnus Barefoot's saga'', chapter 18.

Reign

Establishing authority

Norway had experienced a long period of peace during the reign of Magnus's father, Olaf. Magnus may have been present when Olaf died in Rånrike, Båhuslen (southeastern Norway) in September 1093 and was probably proclaimed king at theBorgarting

The Borgarting () was one of the four regional legislative assemblies or '' lawthings'' (') of medieval Norway. Historically, it was the site of the court and assembly for the south-eastern coastal region of Norway, covering from Göta älv (now i ...

, the thing

Thing or The Thing may refer to:

Philosophy

* An object

* Broadly, an entity

* Thing-in-itself (or ''noumenon''), the reality that underlies perceptions, a term coined by Immanuel Kant

* Thing theory, a branch of critical theory that focuses ...

(assembly) of the adjacent region of Viken

Viken may refer to:

*Viken, Scandinavia, a historical region

*Viken (county), a Norwegian county established in 2020

*Viken, Sweden, a bimunicipal locality in Skåne County, Sweden

*Viken (lake), a lake in Sweden, part of the Göta canal

*IF Viken, ...

later that month. When Magnus became king, he already had a network of support among the Norwegian aristocracy. Although sources are unclear about the first year of his reign, it is apparent that Magnus's focus was on the west (towards the British Isles). Since conditions were chaotic in Norse-dominated parts of the British Isles since the death of Thorfinn the Mighty

Thorfinn Sigurdsson (1009? – 1058?), also known as Thorfinn the Mighty (Old Norse: ''Þorfinnr inn riki''), was an 11th-century Jarl of Orkney. He was the youngest of five sons of Jarl Sigurd Hlodvirsson and the only one resulting from S ...

, this provided Magnus an opportunity to intervene in local power struggles. According to some accounts, he made his first expedition west in 1093–94 (or 1091–92), helping Scottish

Scottish usually refers to something of, from, or related to Scotland, including:

*Scottish Gaelic, a Celtic Goidelic language of the Indo-European language family native to Scotland

*Scottish English

*Scottish national identity, the Scottish ide ...

king Donald Bane to conquer Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. The city is located in southeast Scotland and is bounded to the north by the Firth of Forth and to the south by the Pentland Hills. Edinburgh ...

and the Scottish throne and possibly gaining control of the Southern Isles (''Suðreyjar'') in return. It is unclear if this early expedition took place, since it is not directly referenced in early reliable sources or the sagas.

Magnus was opposed by his cousin Haakon Magnusson, son of King Olaf's brother and short-lived co-ruler King Magnus Haraldsson, who claimed half the kingdom. Haakon was proclaimed king in the Uplands and at the Øyrating, the thing of Trøndelag

Trøndelag (; or is a county and coextensive with the Trøndelag region (also known as ''Midt-Norge'' or ''Midt-Noreg,'' "Mid-Norway") in the central part of Norway. It was created in 1687, then named Trondhjem County (); in 1804 the county was ...

(in central Norway). According to Førsund, Haakon took control of the entire portion of the kingdom once held by his father (also including the Frostating

Frostating () was one of the four ancient popular assemblies or things () of medieval Norway. Historically, it was the site of court and assembly for Trøndelag, Nordmøre, and Hålogaland. The assembly had its seat at Tinghaugen in what is n ...

—the thing of Hålogaland

Hålogaland was the northernmost of the Norwegian provinces in the medieval Norse sagas. In the early Viking Age, before Harald Fairhair, Hålogaland was a kingdom extending between the Namdalen valley in Trøndelag county and the Lyng ...

in northern Norway

Northern Norway (, , ; ) is a geographical region of Norway, consisting of the three northernmost counties Nordland, Troms and Finnmark, in total about 35% of the Norwegian mainland. Some of the largest towns in Northern Norway (from south to no ...

—and the Gulating

Gulating () was one of the four ancient popular assemblies or things (') of medieval Norway. Historically, it was the site of court and assembly for most of Western Norway, and assembled at Gulen. It functioned as a judicial and legislative bo ...

—the thing of western Norway

Western Norway (; ) is the Regions of Norway, region along the Atlantic coast of southern Norway. It consists of the Counties of Norway, counties Rogaland, Vestland, and Møre og Romsdal. The region has no official or political-administrative fu ...

). Haakon secured support by relieving farmers of taxes and duties (including taxes dating back to the Danish rule of Sweyn Knutsson

Svein Knutsson ( ; c. 1016–1035) was the son of Cnut the Great, king of Denmark, Norway, and England, and his first wife Ælfgifu of Northampton, a Mercian noblewoman. In 1017 Cnut married Emma of Normandy, but there is no evidence that Ælfg ...

during the early 1030s), while Magnus pursued costly policies and demanded lengthy military service. After Magnus settled at the new royal estate in Nidaros for the winter of 1094–95, Haakon also travelled to the city and took up residence at the old royal estate. Their relationship became increasingly tense, culminating when Haakon saw Magnus's longships fully rigged at sea. Haakon summoned the Øyrating in response, leading Magnus to sail southwards. Haakon attempted to intercept Magnus by travelling south to Viken by land (over the mountains of Dovrefjell

Dovrefjell is a mountain range in Central Norway that forms a natural barrier between Eastern Norway and Trøndelag. The mountain range is located in Innlandet, Møre og Romsdal, and Trøndelag counties in Norway. As a result of its central loca ...

), but he died unexpectedly while hunting in February 1095.

The strongman behind Haakon's monarchy had been his foster-father Tore Tordsson ("Steigar-Tore"), who refused to recognise Magnus as king after Haakon's death. With Egil Aslaksson and other noblemen, he had the otherwise-unknown Sweyn Haraldsson set up as a

The strongman behind Haakon's monarchy had been his foster-father Tore Tordsson ("Steigar-Tore"), who refused to recognise Magnus as king after Haakon's death. With Egil Aslaksson and other noblemen, he had the otherwise-unknown Sweyn Haraldsson set up as a pretender

A pretender is someone who claims to be the rightful ruler of a country although not recognized as such by the current government. The term may often be used to either refer to a descendant of a deposed monarchy or a claim that is not legitimat ...

. Although later sagas maintain that Sweyn was Danish, some modern historians have speculated that he may have been a son of Harald Hardrada. The revolt was based in the Uplands, but also gained support from noblemen elsewhere in the country. After several weeks of fighting, Magnus captured Tore and his supporters and had them hanged on the island of Vambarholm (outside Hamnøy, Lofoten

Lofoten ( , ; ; ) is an archipelago and a Districts of Norway, traditional district in the county of Nordland, Norway. Lofoten has distinctive scenery with dramatic mountains and peaks, open sea and sheltered bays, beaches, and untouched lands. T ...

, in northern Norway). Magnus was reportedly furious because he could not pardon Egil, a potentially useful, young and resourceful nobleman. As king, his honour would only allow a pardon if other noblemen pleaded for Egil's life; this did not happen.

Magnus's final domestic dispute was with the noble Sveinke Steinarsson, who refused to recognise him as king. Although Sveinke reduced piracy in Viken, he was forced into exile for three years after negotiating with Magnus's men. Since piracy increased soon after Sveinke's departure (possibly encouraged by Sveinke himself), Magnus met him in the Danish province of Halland

Halland () is one of the traditional provinces of Sweden (''landskap''), on the western coast of Götaland, southern Sweden. It borders Västergötland, Småland, Skåne, Scania and the sea of Kattegat. Until 1645 and the Second Treaty of Br ...

to request his return to Norway. They reconciled; Sveinke became a loyal supporter of Magnus, now the undisputed king of Norway.

Other developments

Since the Norse sources (including the skaldic verses which were the sagas' main sources) chiefly describe war-related matters, less is known about other events during the reigns of the early Norwegian kings. Snorri, for instance, wrote fifteen pages about Magnus and only two pages about Magnus's peaceful father Olaf Kyrre (despite Olaf's reign lasting almost three times longer than Magnus's). Modern historians have noted that this probably has made the image of kings like Magnus Barefoot one-sided (in Magnus's case, skewed towards his deeds as a warrior). Magnus's rule was generally marked by Norway's increasing similarity to other European kingdoms. Royal rule became established, and he consolidated power through a network of powerful noblemen (some of whom were relatives); church organisation also developed. The Nordic bishops belonged to theArchdiocese of Hamburg-Bremen

The Prince-Archbishopric of Bremen () was an Hochstift, ecclesiastical principality (787–1566/1648) of the Holy Roman Empire and the Catholic Church that after its definitive secularization in 1648 became the hereditary Bremen-Verden, Duchy of ...

until a year after Magnus's death (when the Archdiocese of Lund

The Diocese of Lund () is a diocese within the Church of Sweden which corresponds to the provinces of Blekinge and Skåne. There are 217 parishes within the diocese, the most significant number in any of the dioceses of the Church of Sweden. Th ...

was formed); priests and bishops were largely foreigners from England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

and Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

. In reality, however, Magnus ruled the church in Norway.

Through numismatics

Numismatics is the study or collection of currency, including coins, tokens, paper money, medals, and related objects.

Specialists, known as numismatists, are often characterized as students or collectors of coins, but the discipline also inclu ...

, it is known that minting reform began during Magnus's reign. The reform restored silver content in coins to around 90 percent, the level at Harald Hardrada's 1055 reform (''Haraldsslåtten'') which reduced silver content to about 30 percent (the remainder of the coin was copper). Coin size in Magnus's reform was reduced to .45 gram, half the previous weight. Although the silver value of a coin remained about the same, copper was not needed in coins.

First Irish Sea campaign

Magnus sought to re-establish Norwegian influence around theIrish Sea

The Irish Sea is a body of water that separates the islands of Ireland and Great Britain. It is linked to the Celtic Sea in the south by St George's Channel and to the Inner Seas off the West Coast of Scotland in the north by the North Ch ...

. He attempted to install vassal king Ingemund in the Southern Isles in 1097, but the latter was killed in a revolt. It is unclear what Magnus's ultimate ambitions were, and the significance of his campaign has been downplayed by modern English historians. English chronicler William of Malmesbury

William of Malmesbury (; ) was the foremost English historian of the 12th century. He has been ranked among the most talented English historians since Bede. Modern historian C. Warren Hollister described him as "a gifted historical scholar and a ...

believed that Magnus sought to capture the throne from William II of England

William II (; – 2 August 1100) was List of English monarchs, King of England from 26 September 1087 until his death in 1100, with powers over Duchy of Normandy, Normandy and influence in Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland. He was less successfu ...

(in common with the ambitions of his grandfather, Harald Hardrada).Oram (2011) p. 48 Historians have speculated that he wanted to establish an empire which included Scotland and Ireland, although most modern Norwegian and Scottish historians believe his chief aim was simply to control the Norse communities around the Irish Sea. While he may have been influenced by Ingemund's murder, the ''Orkneyinga saga

The ''Orkneyinga saga'' (Old Norse: ; ; also called the ''History of the Earls of Orkney'' and ''Jarls' Saga'') is a narrative of the history of the Orkney and Shetland islands and their relationship with other local polities, particularly No ...

'' claims that Magnus was persuaded by a son of an Orkney earl, Haakon Paulsson

Haakon Paulsson (Old Norse: ''Hákon Pálsson''; died 1123) was a Norwegian ''jarl'' who ruled the earldom of Orkney together with his cousin Magnus Erlendsson from 1105 to 1123. Their lives and times are recounted in the ''Orkneyinga saga'', ...

, who wanted an earldom for himself. It is also possible that Magnus wished to provide a realm outside Norway for his eight-year-old son Sigurd

Sigurd ( ) or Siegfried (Middle High German: ''Sîvrit'') is a legendary hero of Germanic heroic legend, who killed a dragon — known in Nordic tradition as Fafnir () — and who was later murdered. In the Nordic countries, he is referred t ...

, who accompanied him. Magnus sailed into the Western Sea in 1098, arriving in Orkney

Orkney (), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago off the north coast of mainland Scotland. The plural name the Orkneys is also sometimes used, but locals now consider it outdated. Part of the Northern Isles along with Shetland, ...

with a large fleet. The '' Chronicles of the Kings of Mann and the Isles'' claim that he had 160 ships, but English chronicler Orderic Vitalis

Orderic Vitalis (; 16 February 1075 – ) was an English chronicler and Benedictine monk who wrote one of the great contemporary chronicles of 11th- and 12th-century Normandy and Anglo-Norman England.Hollister ''Henry I'' p. 6 Working out of ...

states that his fleet consisted of 60 ships. Based on this, P. A. Munch suggests an initial fleet of 160 ships, of which 100 were from the ''leidang

The institution known as ''leiðangr'' (Old Norse), ''leidang'' ( Norwegian), ''leding'' ( Danish), ''ledung'' ( Swedish), ''expeditio'' (Latin) or sometimes lething (English), was a form of conscription ( mass levy) to organize coastal fleets for ...

'' (public levy) and returned shortly after arrival; the fleet accompanying Magnus southward in the campaigns consisted of 60 royal and baronial ships. According to Førsund, the low estimate of 120 men per ship means 8,000 men in the royal and baronial ships and 12,000 from the ''leidang'' ships. However, many historians believe that ship numbers in old naval campaign accounts are exaggerated.

After his arrival, Magnus began negotiations with Scottish and Irish kings about the ''hird'' and control of land in Scotland, Ireland and the surrounding islands. Upon arriving in Orkney, he sent the earls

After his arrival, Magnus began negotiations with Scottish and Irish kings about the ''hird'' and control of land in Scotland, Ireland and the surrounding islands. Upon arriving in Orkney, he sent the earls Paul and Erlend Thorfinnsson

Paul Thorfinnsson (died 1098) and Erlend Thorfinnsson (died 1098) were brothers who ruled together as Earls of Orkney. Paul and Erlend were the sons of Thorfinn Sigurdsson and Ingibiorg Finnsdottir. Through Ingibiorg's father Finn Arnesson an ...

away to Norway as prisoners on a ''leidang'' ship, took their sons Haakon Paulsson, Magnus Erlendsson and Erling Erlendsson as hostages and installed his own son Sigurd as earl. Magnus then raided Scotland, the Southern Isles and Lewis

Lewis may refer to:

Names

* Lewis (given name), including a list of people with the given name

* Lewis (surname), including a list of people with the surname

Music

* Lewis (musician), Canadian singer

* " Lewis (Mistreated)", a song by Radiohe ...

. Meeting no significant opposition, he continued pillaging the Hebridean islands of Uist

Uist is a group of six islands that are part of the Outer Hebridean Archipelago, which is part of the Outer Hebrides of Scotland.

North Uist and South Uist ( or ; ) are two of the islands and are linked by causeways running via the isles of Ben ...

, Skye

The Isle of Skye, or simply Skye, is the largest and northernmost of the major islands in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland. The island's peninsulas radiate from a mountainous hub dominated by the Cuillin, the rocky slopes of which provide some o ...

, Tiree

Tiree (; , ) is the most westerly island in the Inner Hebrides of Scotland. The low-lying island, southwest of Coll, has an area of and a population of around 650.

The land is highly fertile, and crofting, alongside tourism, and fishing are ...

, Mull and Islay

Islay ( ; , ) is the southernmost island of the Inner Hebrides of Scotland. Known as "The Queen of the Hebrides", it lies in Argyll and Bute just south west of Jura, Scotland, Jura and around north of the Northern Irish coast. The island's cap ...

, and the peninsula of Kintyre

Kintyre (, ) is a peninsula in western Scotland, in the southwest of Argyll and Bute. The peninsula stretches about , from the Mull of Kintyre in the south to East Loch Tarbert, Argyll, East and West Loch Tarbert, Argyll, West Loch Tarbert in t ...

; Iona

Iona (; , sometimes simply ''Ì'') is an island in the Inner Hebrides, off the Ross of Mull on the western coast of Scotland. It is mainly known for Iona Abbey, though there are other buildings on the island. Iona Abbey was a centre of Gaeli ...

was visited, but not pillaged.Power (1986) p. 118 Magnus is also recorded as warring in Sanday, although the exact location is unclear (there are three islands with that name in the region). On entering the Irish Sea, he lost three ''leidang'' ships and 120 men in Ulster

Ulster (; or ; or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional or historic provinces of Ireland, Irish provinces. It is made up of nine Counties of Ireland, counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kingdom); t ...

. Magnus then continued to Mann

Mann may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media

* ''Mann'' (film), a 1999 Indian Hindi-language romantic drama

* Mann (chess), a variant chess piece

* ''Mann'' (magazine), a Norwegian magazine

* Mann (rapper), Dijon Shariff Thames (born 19 ...

, where the earl Óttar fell in a violent battle; he also chased (or captured) Lagman Godredsson, King of the Isles

The Kingdom of the Isles, also known as Sodor, was a Norse–Gaelic kingdom comprising the Isle of Man, the Hebrides and the islands of the Clyde from the 9th to the 13th centuries. The islands were known in Old Norse as the , or "Southern Is ...

. Mann came under Norwegian control, and Magnus and his men stayed on the island for a time. During his time there, he organised Norwegian immigration to the island and had several forts and houses built (or rebuilt) using timber from Galloway

Galloway ( ; ; ) is a region in southwestern Scotland comprising the counties of Scotland, historic counties of Wigtownshire and Kirkcudbrightshire. It is administered as part of the council areas of Scotland, council area of Dumfries and Gallow ...

on the Scottish mainland. This implied he had subdued part of that region too,Power (1986) p. 119 reducing its chieftains to tributaries.

Magnus may have intended to invade Ireland next, only to find he had overextended himself. He may have been approached by Gruffudd ap Cynan

Gruffudd ap Cynan (–1137) was List of rulers of Gwynedd, King of Gwynedd from 1081 until his death in 1137. In the course of a long and eventful life, he became a key figure in Welsh resistance to House of Normandy, Norman rule.

As a descen ...

, King of Gwynedd

This is a list of the rulers of the Kingdom of Gwynedd. Many of them were also acclaimed "King of the Britons" or "Prince of Wales".

List of kings or princes of Gwynedd House of Cunedda

* Cunedda (Cunedda the Imperator) (c. 450 – c. 46 ...

, who had been driven to Ireland by the Norman earls Hugh of Montgomery and Hugh d'Avranches

Hugh d'Avranches ( 1047 – 27 July 1101), nicknamed ''le Gros'' (the Large) or ''Lupus'' (the Wolf), was from 1071 the second Norman Earl of Chester and one of the great magnates of early Norman England.

Early life and career

Hugh d'Avra ...

. With six ships (according to Orderic Vitalis), Magnus steered towards Anglesey

Anglesey ( ; ) is an island off the north-west coast of Wales. It forms the bulk of the Principal areas of Wales, county known as the Isle of Anglesey, which also includes Holy Island, Anglesey, Holy Island () and some islets and Skerry, sker ...

in Gwynedd

Gwynedd () is a county in the north-west of Wales. It borders Anglesey across the Menai Strait to the north, Conwy, Denbighshire, and Powys to the east, Ceredigion over the Dyfi estuary to the south, and the Irish Sea to the west. The ci ...

, Wales

Wales ( ) is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is bordered by the Irish Sea to the north and west, England to the England–Wales border, east, the Bristol Channel to the south, and the Celtic ...

. Appearing off the coast at Puffin Island, he interrupted a Norman victory celebration after their defeat of the Gwynedd kingLloyd, J.E., ''A History of Wales; From the Norman Invasion to the Edwardian Conquest'', Barnes & Noble Publishing, Inc. 2004—for the Welsh, "so opportunely it was ascribed to divine providence" according to historian Rosemary Power (although Magnus had not necessarily intended to side with them). In the ensuing battle (known as the Battle of Anglesey Sound, according to Power "the most widely reported event in the history of Magnus"), Magnus shot Hugh of Montgomery dead with an arrow through his eye and defeated the Norman forces.Oram (2011) p. 50 The sources indicate that Magnus regretted killing Montgomery, suggesting that he may have been interested in an alliance with the Normans. He abruptly returned to Mann with his men, leaving the Norman army weak and demoralized. After this battle, Anglesey was considered the southern border of Norway. Gruffudd ap Cynan soon returned to the island, awarding Magnus gifts and honour (which may indicate that Gwynedd had capitulated).Duffy (1997) p. 110 The extension of Magnus's kingdom probably began to concern the English, who remembered the invasion of Magnus's grandfather Harald Hardrada in 1066, war with Danish king Sweyn II Estridson in 1069–70 and the threat of invasion by Cnut IV in 1085.

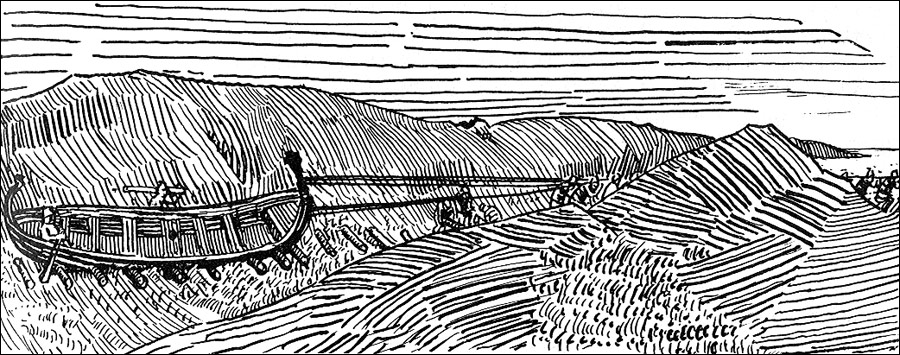

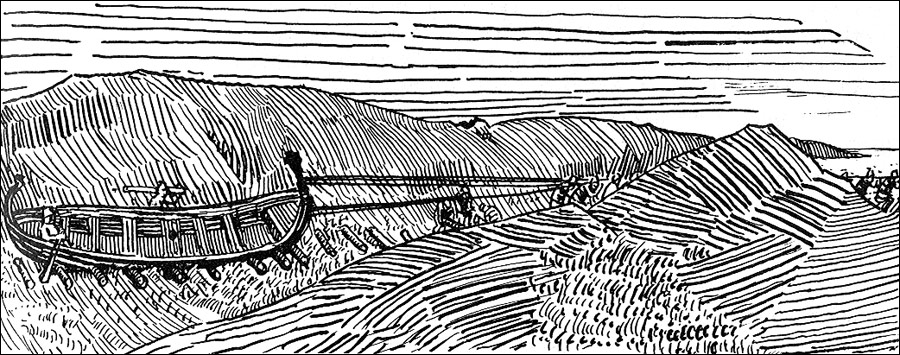

In Scotland internal fighting continued between rival kings, although King

In Scotland internal fighting continued between rival kings, although King Edgar

Edgar is a commonly used masculine English given name, from an Anglo-Saxon name ''Edgar'' (composed of ''wikt:en:ead, ead'' "rich, prosperous" and ''Gar (spear), gar'' "spear").

Like most Anglo-Saxon names, it fell out of use by the Late Midd ...

had gained a slight advantage. Perhaps fearing to meet Magnus in battle after the internecine strife, according to the sagas Edgar—mistakenly called Malcolm—told Magnus he would renounce all Scottish claims to islands west of Scotland in exchange for peace. Magnus accepted the offer, which reportedly gave him every island a ship could reach with its rudder set. He gained recognition of his rule in the Southern Isles, including Kintyre after demonstrating that it should be included by sitting at the rudder of his ship as it was dragged across the narrow isthmus

An isthmus (; : isthmuses or isthmi) is a narrow piece of land connecting two larger areas across an expanse of water by which they are otherwise separated. A tombolo is an isthmus that consists of a spit or bar, and a strait is the sea count ...

at Tarbert.Power (1986) p. 121 Historian Richard Oram

Professor Richard D. Oram F.S.A. (Scot.) is a Scottish historian. He is a professor of medieval and environmental history at the University of Stirling. He is also the director of the Centre for Environmental History and Policy at the Universi ...

has claimed that references to a formal agreement with the Scottish king is a "post-Norwegian civil war confection" designed to legitimise the agenda of Haakon IV Haakonsson. Rosemary Power agrees with the Norse sources that a formal agreement with the Scots was probably concluded, and Seán Duffy notes that Edgar "happily ceded" the isles to Magnus since he had "little or no authority there in any case". Magnus spent the winter in the Hebrides (continuing to fortify the islands), while many of his men returned to Norway. There may have been talks at this time of Magnus marrying Matilda, daughter of late Scottish king Malcolm III Canmore, but no marriage took place. Magnus returned to Norway a year later during the summer of 1099, although many of the islands he had conquered (such as Anglesey) were only nominally under Norwegian control.

Campaign in Sweden

After returning to Norway, Magnus turned east. By claiming an ancient border between Norway and Sweden, he set his course for the Swedish provinces ofDalsland

Dalsland () is a Swedish traditional province, or ''landskap'', situated in Götaland in southern Sweden. Lying to the west of Lake Vänern, it is bordered by Värmland to the north, Västergötland to the southeast, Bohuslän to the west, ...

and Västergötland

Västergötland (), also known as West Gothland or the Latinized version Westrogothia in older literature, is one of the 25 traditional non-administrative provinces of Sweden (''landskap'' in Swedish), situated in the southwest of Sweden.

Vä ...

in late 1099. In Magnus's view, the border with Sweden should be set further east: at the Göta älv

The (; "River of (the) Geats") is a river that drains lake Vänern into the Kattegat, at the city of Gothenburg, on the western coast of Sweden. It was formed at the end of the last glaciation, as an outflow channel from the Baltic Ice Lake to ...

river, through the Vänern

Vänern ( , , ) is the largest lake in Sweden, the largest lake in the European Union and the third-largest lake in Europe after Ladoga and Onega in Russia. It is located in the provinces of Västergötland, Dalsland, and Värmland in the sou ...

lake and north to the province of Värmland

Värmland () is a ''Provinces of Sweden, landskap'' (historical province) in west-central Sweden. It borders Västergötland, Dalsland, Dalarna, Västmanland, and Närke, and is bounded by Norway in the west.

Name

Several Latinized version ...

. He claimed all land west of Vänern (chiefly Dalsland). Swedish king Inge Stenkilsson refuted the claim, and Magnus began a campaign in response. He raided his way through the forest villages, and Inge began amassing an army. When advised by his men to retreat, Magnus became more aggressive; he believed that once begun, a campaign should never be aborted. In a surprise nighttime attack, Magnus assaulted Swedish forces east of Göta älv at Fuxerna (near Lilla Edet

Lilla Edet is a locality and the seat of Lilla Edet Municipality in Västra Götaland County, Sweden. It had 4,862 inhabitants in 2010.

Lilla Edet was the smallest of three settlements that were burnt down in Sweden on 25 June 1888. The wooden to ...

). After defeating the Swedes at Fuxerna, he conquered part of Västergötland. According to a skald

A skald, or skáld (Old Norse: ; , meaning "poet"), is one of the often named poets who composed skaldic poetry, one of the two kinds of Old Norse poetry in alliterative verse, the other being Eddic poetry. Skaldic poems were traditionally compo ...

, Magnus conquered "fifteen hundreds from the Geats

The Geats ( ; ; ; ), sometimes called ''Geats#Goths, Goths'', were a large North Germanic peoples, North Germanic tribe who inhabited ("land of the Geats") in modern southern Sweden from antiquity until the Late Middle Ages. They are one of ...

". He had a wooden fort, surrounded by a moat, built on the island of Kållandsö

Kållandsö is an island in lake Vänern in Sweden. With an area of 56.78 km² it is the second largest island in the lake after Torsö. It is the northernmost part of the municipality of Lidköping

Lidköping () is a locality and the sea ...

in the southern portion of Vänern. Before returning to Norway, Magnus left 300 men on the island for the winter (led by Finn Skofteson and Sigurd Ullstreng).

According to Randi Helene Førsund, the Norwegians in Kållandsö appear to have been characterized by arrogance (perhaps due to their successes under Magnus) and taunted the Swedish king for taking so long to arrive. After newly formed ice connected the island to the mainland, Inge arrived with about 3,000 men. Although he offered several times to allow the Norwegians to return home in peace (with their plunder and possessions), Inge's offers were rejected. The Swedes finally attacked, burning the fort. The Norwegians were spared and allowed to return home, after being beaten with sticks and surrendering all their possessions. Angry at the humiliating defeat, Magnus planned revenge. He entered Sweden the following year, reconquering the same areas. During the hasty campaign Magnus and his men were ambushed by Swedish forces and forced to flee back to their ships, suffering heavy losses. The war continued until 1100 or 1101.

Danish king Eric Evergood, concerned that the conflict would escalate, began peace talks between the two kings. Relations had been strained between Denmark and Norway after Magnus's 1096 raids into Halland, and Eric feared that the conflict might spill over into his own country. The three Scandinavian kings eventually agreed to negotiate peace in the border area near Göta älv. After a constructive meeting, they agreed to preserve ancestral borders; by marrying Inge's daughter

According to Randi Helene Førsund, the Norwegians in Kållandsö appear to have been characterized by arrogance (perhaps due to their successes under Magnus) and taunted the Swedish king for taking so long to arrive. After newly formed ice connected the island to the mainland, Inge arrived with about 3,000 men. Although he offered several times to allow the Norwegians to return home in peace (with their plunder and possessions), Inge's offers were rejected. The Swedes finally attacked, burning the fort. The Norwegians were spared and allowed to return home, after being beaten with sticks and surrendering all their possessions. Angry at the humiliating defeat, Magnus planned revenge. He entered Sweden the following year, reconquering the same areas. During the hasty campaign Magnus and his men were ambushed by Swedish forces and forced to flee back to their ships, suffering heavy losses. The war continued until 1100 or 1101.

Danish king Eric Evergood, concerned that the conflict would escalate, began peace talks between the two kings. Relations had been strained between Denmark and Norway after Magnus's 1096 raids into Halland, and Eric feared that the conflict might spill over into his own country. The three Scandinavian kings eventually agreed to negotiate peace in the border area near Göta älv. After a constructive meeting, they agreed to preserve ancestral borders; by marrying Inge's daughter Margaret

Margaret is a feminine given name, which means "pearl". It is of Latin origin, via Ancient Greek and ultimately from Iranian languages, Old Iranian. It has been an English language, English name since the 11th century, and remained popular thro ...

(who acquired the byname ''Fredkulla'': "Maiden of Peace"), Magnus acquired the lands he claimed on behalf of his ancestors. Since the marriage was childless, Dalsland never became established as a Norwegian province and was returned to Sweden after his death.

Second Irish Sea campaign and death

Magnus again set his course for Ireland in 1101 or 1102, this time probably with a greater army than he had in his previous campaign. One of his biggest challenges was the number of petty kings and alliances on the island. Irish sources maintain that Magnus came to "take Ireland", "invade Ireland" or "besiege Ireland".Duffy (1997) p. 111 He received reinforcements from Orkney on his way to Mann, where he set up a base to survey conditions. Tensions ran high between Magnus and the king ofMunster

Munster ( or ) is the largest of the four provinces of Ireland, located in the south west of the island. In early Ireland, the Kingdom of Munster was one of the kingdoms of Gaelic Ireland ruled by a "king of over-kings" (). Following the Nor ...

and High King of Ireland

High King of Ireland ( ) was a royal title in Gaelic Ireland held by those who had, or who are claimed to have had, lordship over all of Ireland. The title was held by historical kings and was later sometimes assigned anachronously or to leg ...

, Muirchertach Ua Briain

Muirchertach Ua Briain (anglicised as Murtaugh O'Brien; c. 1050 – c. 10 March 1119), son of Toirdelbach Ua Briain and great-grandson of Brian Boru, was King of Munster and later self-declared High King of Ireland.

Background and early career ...

(''Mýrjartak''), who was struggling with his rival Domnall Ua Lochlainn

Domhnall Ua Lochlainn (old spelling: Domnall Ua Lochlainn) (1048 – 10 February 1121), also known as Domhnall Mac Lochlainn (old spelling: Domnall Mac Lochlainn), was king of the Cenél Eogain, over-king of Ailech, and alleged High King o ...

. Magnus may have tested the situation in 1101, when unnamed sailors are said to have raided Scattery Island (near Muirchertach's base).Power (2005) p. 15 After his arrival at Mann, Irish sources describe Magnus as agreeing to "a year's peace" with the Irish (suggesting enmity; such agreements were diplomatic devices, usually negotiated between two sides in war). The marriage agreement described in other sources was part of the treaty; Magnus's son, Sigurd, married Muirchertach's daughter Bjaðmunjo. On their wedding day, Magnus named Sigurd his co-king and put him in charge of the western lands.Duffy (1997) p. 112 Muirchertach also recognised Magnus's control over Dublin

Dublin is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. Situated on Dublin Bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, and is bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, pa ...

and Fingal

Fingal ( ; ) is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster and is part of the Eastern and Midland Region. It is one of three successor counties to County Dublin, which ...

.

Around the same time Muirchertach married a daughter of Arnulf of Montgomery

Arnulf de Montgomery (born 1066; died 1118/1122) was an Anglo-Norman magnate. He was a younger son of Roger de Montgomery and Mabel de Bellême. Arnulf's father was a leading magnate in Normandy and England, and played an active part in the ...

, brother of Hugh (who was killed by Magnus in 1098).Power (2005) p. 17 The account in ''Morkinskinna'' concerning a "foreign knight" named "Giffarðr", who appeared at the court of Magnus before his Swedish campaign, is suggested by Rosemary Power as evidence that Magnus may have conspired with the Norman Walter Giffard, Earl of Buckingham (or a family member) in the revolt against Henry I of England

Henry I ( – 1 December 1135), also known as Henry Beauclerc, was King of England from 1100 to his death in 1135. He was the fourth son of William the Conqueror and was educated in Latin and the liberal arts. On William's death in 1087, Henr ...

. According to Orderic Vitalis, Magnus left treasure with a wealthy citizen in Lincoln which was confiscated by King Henry after Magnus's death. This treasure could have been paid by Norman earls for Magnus's support, and possibly arranged by the Giffarðr who is said to have visited Magnus's court in the sagas. This could have provided Magnus with a lucrative return for his costly western campaigns, which were unpopular in Norway at the time.

Muirchertach was skilled in diplomacy, and negotiation with the dowries of his daughters may have been part of a political game. While he may not have intended to honour his agreements with Magnus (or others), he needed the latter's assistance to crush Domnall. Magnus and Muirchertach went on joint raiding expeditions after the peace agreement, only interrupted by the winter of 1102–03. The sagas claim that Magnus wintered in Connacht

Connacht or Connaught ( ; or ), is the smallest of the four provinces of Ireland, situated in the west of Ireland. Until the ninth century it consisted of several independent major Gaelic kingdoms (Uí Fiachrach, Uí Briúin, Uí Maine, C ...

, but since Connacht is incorrectly claimed to be Muirchertach's kingdom the location was corrected to Kincora, Munster by modern historians.Førsund (2012) p. 125 Rosemary Power considered it more likely that Magnus would have kept his fleet near Dublin. Magnus was probably allied with Muirchertach during his campaigns against Domnall and the Cenél nEógain

Cenél is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

*Cenél Conaill, the name of the "kindred" or descendants of Conall Gulban, son of Niall Noígiallach defined by oral and recorded history

* Cenél nEógain (in English, Cenel Eogan) is ...

in 1103, but (in contrast to the Norse sources) Irish sources (the ''Annals of Ulster

The ''Annals of Ulster'' () are annals of History of Ireland, medieval Ireland. The entries span the years from 431 AD to 1540 AD. The entries up to 1489 AD were compiled in the late 15th century by the scribe Ruaidhrí Ó Luin� ...

'' and ''Annals of the Four Masters

The ''Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland'' () or the ''Annals of the Four Masters'' () are chronicles of Middle Ages, medieval Irish history. The entries span from the Genesis flood narrative, Deluge, dated as 2,242 Anno Mundi, years after crea ...

'') do not describe their campaigns as successful. On 5 August 1103, Muirchertach unsuccessfully tried to subdue Domnall in the Battle of Mag Coba.Duffy (1997) p. 113 Magnus did not take part, but his Dublin subjects fought with Muirchertach. Since Magnus was closing in on the Irish throne, Muirchertach may have wanted him out of the way. According to ''Morkinskinna'' and ''Heimskringla'', the two agreed that Muirchertach was to bring Magnus and his men cattle provisions for their return to Norway; as this dragged on past the agreed time, Magnus became suspicious that the Irish planned an attack. He gathered his men on St. Bartholomew's Day (or the day before, according to ''Ágrip''), 24 August 1103, and ventured into the country. It is possible that Magnus and his men made an incautious landing to raid cattle,Power (1986) p. 128 or the Ulaid mistook the Norwegians for cattle-raiding Hebrideans. Alternatively, Muirchertach may have ordered the Ulaid to bring provisions to Magnus, inciting the Ulaid to ambush the Norwegians.

Norse sources describe a large force emerging from hiding places in an ambush. The Norwegian forces were taken by surprise, and were not in battle order. Magnus attempted to assert control over his disordered army, ordering part of his force to seize secure ground and use archery fire to slow the Irish. In the melee Magnus was pierced by a spear through both thighs above the knees but he fought on, attempting to get his men back to the level campsite. An axe-wielding Irishman charged him, striking a lethal blow to his neck. When his men said that he proceeded incautiously in his campaigns, Magnus is reported to have responded "Kings are made for honour, not for long life"; he was the last Norwegian king to fall in battle abroad.

Perhaps betrayed by Muirchertach, Magnus may also have been betrayed by his own men (in particular the contingent of nobleman Torgrim Skinnluve from the Uplands, who fled to the ships during the battle). It is possible that Torgrim and his men may have been directed by powerful men in Norway, who wanted Magnus removed from the Norwegian throne. More Irishmen than Norwegians fell in the battle, according to Snorri Sturluson, and Magnus's reign could have been different if Torgrim and his men had fought as directed. Magnus's son Sigurd returned to Norway without his child bride after his father's defeat, and direct Norwegian control in the region came to an end. Although Norwegian influence remained, no Norwegian king returned for more than 150 years.

Descendants

Magnus married Margaret Fredkulla, daughter of Swedish king Inge Stenkilsson, as part of the peace agreement of 1101. Their marriage did not produce any children. His three sons (who succeeded him as king) were born to different women, and he had two known daughters by unidentified women: * Eystein: Born 1089 to a mother "of low birth". *Sigurd

Sigurd ( ) or Siegfried (Middle High German: ''Sîvrit'') is a legendary hero of Germanic heroic legend, who killed a dragon — known in Nordic tradition as Fafnir () — and who was later murdered. In the Nordic countries, he is referred t ...

: Born 1090; his mother's name was Tora.

* Olaf

Olaf or Olav (, , or differences between General American and Received Pronunciation, British ; ) is a Dutch, Polish, Scandinavian and German given name. It is presumably of Proto-Norse origin, reconstructed as ''*Anu-laibaz'', from ''anu'' "ances ...

: Born ; his mother was Sigrid Saxesdatter from Vik in Strinda, Trøndelag

Trøndelag (; or is a county and coextensive with the Trøndelag region (also known as ''Midt-Norge'' or ''Midt-Noreg,'' "Mid-Norway") in the central part of Norway. It was created in 1687, then named Trondhjem County (); in 1804 the county was ...

.

* Ragnild: Married Harald Kesja, Danish pretender and son of Danish king Eric Evergood.

* Tora

Tora or TORA may refer to:

People

* Tora (given name), female given name

* Tora (surname)

* Tora people of Arabia and northern Africa

* Torá language, an extinct language once spoken in Brazil

Places

* Tora, Benin, in Borgou Department

* T ...

: Married Icelandic chieftain Loftur Sæmundsson.

Years after Magnus's death, other men came forward claiming to be his sons; however, it is impossible to ascertain the veracity of these claims:

* Harald Gille

Harald Gille (, c. 1102 − 14 December 1136), also known as Harald IV, was king of Norway from 1130 until his death. His byname Gille is probably .

Background

Harald was born ca. 1102 in Ireland or the Hebrides, more likely the former. Accord ...

: Born 1103 in Ireland, his claim was recognised by Magnus's son Sigurd.

* Sigurd Slembe

Sigurd Magnusson Slembe (or Slembedjakn) (died 12 November 1139) was a Norwegian pretender to the throne.

He was the subject of '' Sigurd Slembe'', the historical drama written by the Norwegian playwright Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson in 1862.

Biogr ...

: His mother was Tora Saxesdatter from Vik; his claim was not recognised (by Harald Gille).

* Magnus Raude: Mentioned only in ''Fagrskinna''.

Aftermath

Burial

Magnus probably died in the vicinity of theRiver Quoile

The Quoile (; ) is a river in County Down, Northern Ireland.

Course

The river begins its life as the Ballynahinch River which flows from west of the town of Ballynahinch to Annacloy where it is known as the Annacloy River. This then becomes ...

. According to the ''Chronicles of the Kings of Mann and the Isles'', Magnus was "buried near the Church of St Patrick, in Down". About two miles (1.2 km) south of the cathedral on Horse Island is a mound which became known as Magnus's Grave after its identification on an 1859 map attributed to Danish archaeologist Jens Jacob Asmussen Worsaae

Jens Jacob Asmussen Worsaae (14 March 1821 – 15 August 1885) was a Danish archaeologist, historian and politician, who was the second director of the National Museum of Denmark (1865–1874). He played a key role in the foundation of scientifi ...

. Snorri Sturluson's description of the marshy and difficult terrain where Magnus and his men were attacked fits the conditions in and around Horse Island, making it a strong candidate for the burial site. According to Finbar McCormick, the people who ambushed Magnus may not have wanted a Christian burial for him and his men, instead burying them near where they had been slain. The Downpatrick runestone monument marking the site was erected in March 2003 to mark the 900th anniversary of his death. The burial site is largely only accessible via the heritage railway in Downpatrick; a halt overlooking the barrow and runestone has been carved by James Higgins and erected by Philip Campbell, local viking history enthusiast, chairman and founder of the Magnus Viking Association and the Ballydugan Medieval Settlement which is located a short distance from the Runestone on the Drumcullan Road.

Succession

Magnus was succeeded peacefully by his three sons:Sigurd

Sigurd ( ) or Siegfried (Middle High German: ''Sîvrit'') is a legendary hero of Germanic heroic legend, who killed a dragon — known in Nordic tradition as Fafnir () — and who was later murdered. In the Nordic countries, he is referred t ...

, Eystein and Olaf

Olaf or Olav (, , or differences between General American and Received Pronunciation, British ; ) is a Dutch, Polish, Scandinavian and German given name. It is presumably of Proto-Norse origin, reconstructed as ''*Anu-laibaz'', from ''anu'' "ances ...

. Near the end of Sigurd's reign (he having outlived his brothers) during the late 1120s, the previously unknown Harald Gille

Harald Gille (, c. 1102 − 14 December 1136), also known as Harald IV, was king of Norway from 1130 until his death. His byname Gille is probably .

Background

Harald was born ca. 1102 in Ireland or the Hebrides, more likely the former. Accord ...

came to Norway from the west claiming to be a son of Magnus Barefoot and legitimate successor to the kingdom. Sigurd recognised Harald as his brother (and successor) after Harald walked uninjured over nine burning ploughshares in a trial by ordeal

Trial by ordeal was an ancient judicial practice by which the guilt or innocence of the accused (called a "proband") was determined by subjecting them to a painful, or at least an unpleasant, usually dangerous experience.

In medieval Europe, like ...

, and he was proclaimed king after Sigurd's death in 1130 with Sigurd's son Magnus Sigurdsson. Since Harald was accompanied by his mother to Norway, Sigurd may have recognised a former lover of his father.Power (2005) p. 18

Relations between Harald and Magnus Sigurdsson soured, and several years later Harald had Magnus mutilated and deposed (hence his byname "the Blind"). Soon afterwards, Harald was murdered by another pretender: Sigurd Slembe

Sigurd Magnusson Slembe (or Slembedjakn) (died 12 November 1139) was a Norwegian pretender to the throne.

He was the subject of '' Sigurd Slembe'', the historical drama written by the Norwegian playwright Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson in 1862.

Biogr ...

, who also claimed to be a son of Magnus Barefoot and had been outlawed by Harald. After Harald's death Slembe allied himself with Magnus the Blind, but they were defeated by chieftains loyal to Harald Gille's family in the Battle of Holmengrå

The Battle of Holmengrå () was a naval battle fought on 12 November 1139 near the island Holmengrå south of Hvaler, between the forces of the child kings Sigurd Haraldsson and Inge Haraldsson on the one side, and on the other side the preten ...

. Magnus was killed during the battle; Sigurd was captured, tortured and executed. This began what would become the century-long Norwegian civil-war era.

Legacy

The earliest-known native Irishman to have been named Magnus may have been the son of Muirchertach's greatest rival, Domnall Ua Lochlainn; Magnus became a name among the Ulaid during the 12th century. According to ''Morkinskinna'', tribute from Ireland was received in Norway as late as about twelve years after Magnus's death. Magnus became the subject of at least two Gaelic ballads as the character Manus Mór. In the best-known version, he returns to Norway after an expedition to the west; he is killed in the second version. The different versions are probably derived from Magnus's two expeditions. There are also traditions concerning Magnus in Scotland in legends, poems and local history.Førsund (2012) p. 11 In modern times, a "Magnus Barelegs festival" has been held near Downpatrick at Delamont Country park bi-annually. Traditionally held on the last weekend of August every second year (27 and 28 August 2022) it is organised, funded and carried out by the Magnus Viking Association. There is a beer named after his sword, Legbiter. In Norway, according to Førsund, Magnus has "been reduced to a sigh" in history books; little remains to commemorate him. When King Magnus was killed in an ambush by the Men ofUlster

Ulster (; or ; or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional or historic provinces of Ireland, Irish provinces. It is made up of nine Counties of Ireland, counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kingdom); t ...

, his sword was retrieved and sent home.

References

Bibliography

Primary sources * Sturluson, Snorri (c. 1230).Magnus Barefoot's saga

' (in ''Heimskringla''). English translation: Samuel Laing (London, 1844). *

Theodoric the Monk

Theodoric the Monk (; also ''Tjodrik munk''; in Old Norse his name was most likely ''Þórir'') was a 12th-century Norwegian Benedictine monk, perhaps at the Nidarholm Abbey. He may be identical with either Bishop Thorfinn of Hamar, Tore of the An ...

(c. 1180). The Ancient History of the Norwegian Kings

'. English translation: David and Ian McDougall (London, 1998). *

Ágrip af Nóregskonungasögum

' (c. 1180s). English translation: M. J. Driscoll (London, 2008). *

' (c. 1262). English translation: Rev. Goss (Douglas, 1874). *

Fagrskinna

' (c. 1220s), in Old Norse. Edited by Finnur Jónsson (Copenhagen, 1902). *

Morkinskinna

' (c. 1220s), in Old Norse. Edited by Finnur Jónsson (Copenhagen, 1932). *

' (c. 1230). English translation: George W. Dasent (London, 1894). *

Annals of Inisfallen

'. English translation (2008). *

'. English translation (2013). *

Annales Cambriæ

', in Latin. Edited by John Williams ab Ithel (London, 1860). *

Brut y Tywysogion

'. English translation: John Williams ab Ithel (1860). Books * * * * * * * * Journals * * * * * *

Further reading

* * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Magnus 3 1073 births 1103 deaths 11th-century rulers of the Kingdom of the Isles 12th-century rulers of the Kingdom of the Isles 11th-century Norwegian monarchs 12th-century Norwegian monarchs Monarchs of the Isle of Man Monarchs of Dublin House of Hardrada Monarchs killed in action Illegitimate children of Norwegian monarchs Sons of kings