Lazar Kaganovich on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Lazar Moiseyevich Kaganovich (; – 25 July 1991) was a Soviet politician and one of

/ref> In 1932, he led the suppression of the workers' strike in Ivanovo-Voznesensk.

In July 1932, Molotov and Kaganovich travelled to

In July 1932, Molotov and Kaganovich travelled to

Encyclopedia of History of Ukraine

In spring 1935, Kaganovich was replaced as the secretary in charge of party organisation, and as chairman of the purge commission, by

In spring 1935, Kaganovich was replaced as the secretary in charge of party organisation, and as chairman of the purge commission, by

/ref> and criticized Soviet media attacks on Stalin: "First, Stalin is disowned, now, little by little, it gets to prosecute socialism, the October Revolution, and in no time they will also want to prosecute Lenin and Marx." Shortly before death he suffered a heart attack. In 1991 Kaganovich was interviewed about the alleged murder of Lenin's widow, in which he suggested

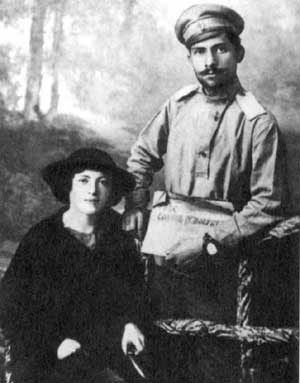

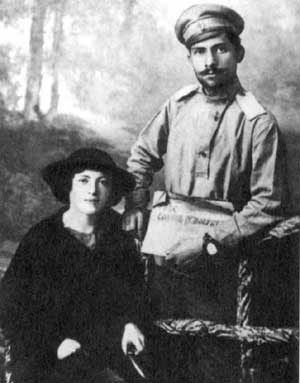

Kaganovich was married to Maria Markovna Kaganovich (née Privorotskaya) (1894–1961), a fellow assimilated Kievan Jew who was part of the revolutionary effort since 1909. Mrs Kaganovich spent many years as a powerful municipal official, directly ordering the demolition of the Iberian Gate and Chapel and

Kaganovich was married to Maria Markovna Kaganovich (née Privorotskaya) (1894–1961), a fellow assimilated Kievan Jew who was part of the revolutionary effort since 1909. Mrs Kaganovich spent many years as a powerful municipal official, directly ordering the demolition of the Iberian Gate and Chapel and

Profile at http://www.hrono.ru

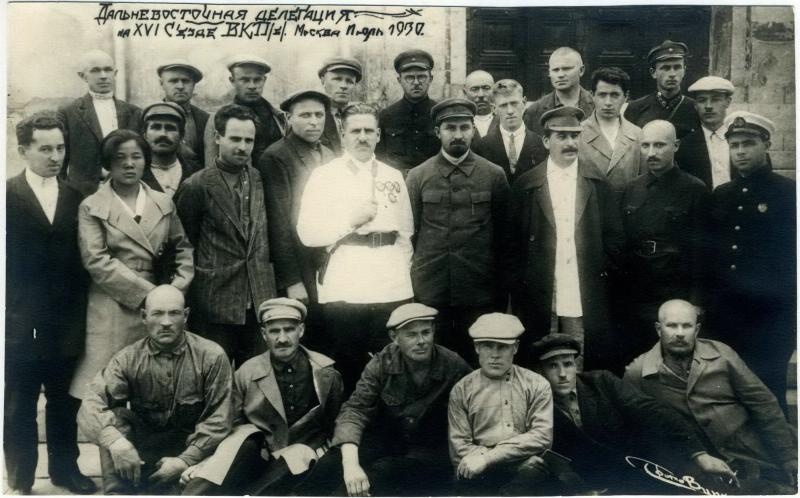

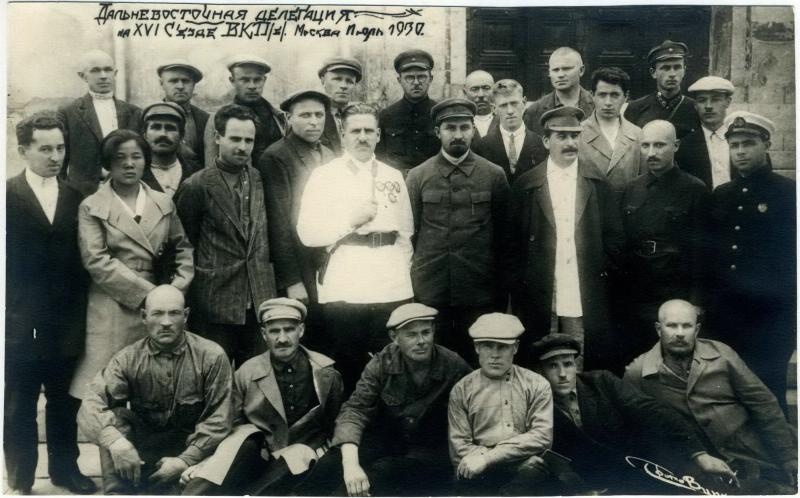

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Kaganovich, Lazar 1893 births 1991 deaths Stalinism Anti-revisionists Burials at Novodevichy Cemetery Deputy heads of government of the Soviet Union Expelled members of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union First convocation members of the Verkhovna Rada of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic First secretaries of the Communist Party of Ukraine (Soviet Union) Genocide perpetrators Great Purge perpetrators Heroes of Socialist Labour Holodomor Jewish socialists Jewish Soviet politicians Old Bolsheviks People from Kiev Governorate Politicians from Kyiv Oblast People's Commissariat of Heavy Industry People's commissars and ministers of the Soviet Union Members of the Orgburo of the 15th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Orgburo of the 16th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Orgburo of the 17th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Orgburo of the 18th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Secretariat of the 13th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Secretariat of the 14th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Secretariat of the 15th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Secretariat of the 16th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Secretariat of the 17th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Candidates of the Politburo of the 14th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Candidates of the Politburo of the 15th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Politburo of the 16th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Politburo of the 17th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Politburo of the 18th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Presidium of the 19th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union Members of the Presidium of the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union Candidates of the Central Committee of the 12th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 13th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 14th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 15th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 16th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 17th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 18th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 19th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union Members of the Central Committee of the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union Anti-Party Group Recipients of the Order of Lenin Recipients of the Order of the Red Banner of Labour Russian Social Democratic Labour Party members Soviet people of World War II Ukrainian communists Russian Constituent Assembly members

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

's closest associates.

Born to a Jewish family in Ukraine, Kaganovich worked as a shoemaker and joined the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party

The Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP), also known as the Russian Social Democratic Workers' Party (RSDWP) or the Russian Social Democratic Party (RSDP), was a socialist political party founded in 1898 in Minsk, Russian Empire. The ...

in 1911. During and after the 1917 October Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

, he held leading positions in Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

organizations in Belarus and Russia, and helped consolidate Soviet rule in Turkestan

Turkestan,; ; ; ; also spelled Turkistan, is a historical region in Central Asia corresponding to the regions of Transoxiana and East Turkestan (Xinjiang). The region is located in the northwest of modern day China and to the northwest of its ...

. In 1922, Stalin placed Kaganovich in charge of an organizational department of the Communist Party, assisting the former in consolidating his grip on the party. Kaganovich was appointed First Secretary of the Communist Party of Ukraine

First most commonly refers to:

* First, the ordinal form of the number 1

First or 1st may also refer to:

Acronyms

* Faint Images of the Radio Sky at Twenty-Centimeters, an astronomical survey carried out by the Very Large Array

* Far Infrared a ...

in 1925, and a full member of the Politburo

A politburo () or political bureau is the highest organ of the central committee in communist parties. The term is also sometimes used to refer to similar organs in socialist and Islamist parties, such as the UK Labour Party's NEC or the Poli ...

and Stalin's deputy party secretary in 1930. In 1932–33, he helped enforce grain quotas in Ukraine which contributed to the Holodomor

The Holodomor, also known as the Ukrainian Famine, was a mass famine in Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, Soviet Ukraine from 1932 to 1933 that killed millions of Ukrainians. The Holodomor was part of the wider Soviet famine of 1930–193 ...

famine. From the mid-1930s on, Kaganovich variously served as the People's Commissar

Commissar (or sometimes ''Kommissar'') is an English language, English transliteration of the Russian language, Russian (''komissar''), which means 'commissary'. In English, the transliteration ''commissar'' often refers specifically to the pol ...

for Railways

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport using wheeled vehicles running in tracks, which usually consist of two parallel steel rails. Rail transport is one of the two primary means of land transport, next to roa ...

, Heavy Industry

Heavy industry is an industry that involves one or more characteristics such as large and heavy products; large and heavy equipment and facilities (such as heavy equipment, large machine tools, huge buildings and large-scale infrastructure); o ...

and Oil Industry

The petroleum industry, also known as the oil industry, includes the global processes of exploration, extraction, refining, transportation (often by oil tankers and pipelines), and marketing of petroleum products. The largest volume products ...

, and during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

was appointed a member of the State Defence Committee.

After Stalin's death

Joseph Stalin, second leader of the Soviet Union, died on 5 March 1953 at his Kuntsevo Dacha after suffering a stroke, at age 74. He was given a state funeral in Moscow on 9 March, with four days of national mourning declared. On the day of t ...

in 1953 and the rise of Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and the Premier of the Soviet Union, Chai ...

, Kaganovich quickly lost his influence. After joining in a failed coup against Khrushchev in 1957, Kaganovich was dismissed from the Presidium and demoted to the director of a small potash

Potash ( ) includes various mined and manufactured salts that contain potassium in water- soluble form.

works in the Urals

The Ural Mountains ( ),; , ; , or simply the Urals, are a mountain range in Eurasia that runs north–south mostly through Russia, from the coast of the Arctic Ocean to the river Ural (river), Ural and northwestern Kazakhstan.

. He was expelled from the party in 1961 and lived out his life as a pensioner in Moscow

Moscow is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Russia by population, largest city of Russia, standing on the Moskva (river), Moskva River in Central Russia. It has a population estimated at over 13 million residents with ...

. At his death in 1991, he was the last surviving Old Bolshevik

The Old Bolsheviks (), also called the Old Bolshevik Guard or Old Party Guard, were members of the Bolshevik faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party prior to the Russian Revolution of 1917. Many Old Bolsheviks became leading politi ...

. The Soviet Union itself outlasted him by only five months, dissolving on 26 December 1991.

Early life

Kaganovich was born in 1893 toJew

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, religion, and community are highly inte ...

ish parents

in the village of Kabany, Radomyshl uyezd

An uezd (also spelled uyezd or uiezd; rus, уе́зд ( pre-1918: уѣздъ), p=ʊˈjest), or povit in a Ukrainian context () was a type of administrative subdivision of the Grand Duchy of Moscow, the Tsardom of Russia, the Russian Empire, the R ...

, Kiev Governorate

Kiev Governorate was an administrative-territorial unit ('' guberniya'') of the Russian Empire (1796–1917), Ukrainian People's Republic (1917–18; 1918–1921), Ukrainian State (1918), and the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic (1919–19 ...

, Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

(today Dibrova, Kyiv Oblast

Kyiv Oblast (, ), also called Kyivshchyna (, ), is an Administrative divisions of Ukraine, oblast (province) in central and northern Ukraine. It surrounds, but does not include, the city of Kyiv, which is administered as a city with special sta ...

, Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

). Although not from a "fanatically observant" family, according to Kaganovich, he spoke Yiddish

Yiddish, historically Judeo-German, is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated in 9th-century Central Europe, and provided the nascent Ashkenazi community with a vernacular based on High German fused with ...

at home. He was the son of Moisei Benovich Kaganovich (1863–1923) and Genya Iosifovna Dubinskaya (1860–1933). Of the 13 children born to the family, 6 died in infancy. Lazar had four elder brothers, all of whom became members of the Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

party. Several of Lazar's brothers ended up occupying positions of varying significance in the Soviet government. Mikhail Kaganovich (1888–1941) served as People's Commissar of Defence Industry before being appointed Head of the People's Commissariat of the Aviation Industry of the USSR, while Yuli Kaganovich (1892–1962) became the 3rd First Secretary of the Gorky Regional Committee of the CPSU. Israel Kaganovich (1884–1973) was made the head of the Main Directorate for Cattle Harvesting of the Ministry of Meat and Dairy Industry. However, Aron Moiseevich Kaganovich (1888–1960s) apparently decided against following his siblings into government, and did not pursue a career in politics. Lazar also had a sister, Rachel Moiseevna Kaganovich (1883–1926), who married Mordechai Ber Lantzman; they lived together in Chernobyl

Chernobyl, officially called Chornobyl, is a partially abandoned city in Vyshhorod Raion, Kyiv Oblast, Ukraine. It is located within the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, to the north of Kyiv and to the southwest of Gomel in neighbouring Belarus. ...

for a period, but she subsequently died in the 1920s and was interred in Kiev

Kyiv, also Kiev, is the capital and most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city of Ukraine. Located in the north-central part of the country, it straddles both sides of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2022, its population was 2, ...

.

Lazar Kaganovich left school at 14, to work in shoe factories and cobblers' shops. Around 1911, he joined the Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

party (his older brother Mikhail Kaganovich had become a member in 1905). Early in his political career, in 1915, Kaganovich became a Communist organizer at a shoe factory where he worked. During the same year he was arrested and sent back to Kabany.

Revolution and Civil War

During March and April 1917, he served as the Chairman of the Tanners Union and as the vice-chairman of the YuzovkaSoviet

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

. In May 1917, he became the leader of the military organization of Bolsheviks in Saratov

Saratov ( , ; , ) is the largest types of inhabited localities in Russia, city and administrative center of Saratov Oblast, Russia, and a major port on the Volga River. Saratov had a population of 901,361, making it the List of cities and tow ...

, and in August 1917, he became the leader of the '' Polessky Committee'' of the Bolshevik party in Belarus

Belarus, officially the Republic of Belarus, is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by Russia to the east and northeast, Ukraine to the south, Poland to the west, and Lithuania and Latvia to the northwest. Belarus spans an a ...

. During the October Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

of 1917 he led the revolt in Gomel

Gomel (, ) or Homyel (, ) is a city in south-eastern Belarus. It serves as the administrative centre of Gomel Region and Gomel District, though it is administratively separated from the district. As of 2025, it is the List of cities and largest ...

.

In 1918 Kaganovich acted as Commissar

Commissar (or sometimes ''Kommissar'') is an English transliteration of the Russian (''komissar''), which means ' commissary'. In English, the transliteration ''commissar'' often refers specifically to the political commissars of Soviet and ...

of the propaganda department of the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

. From May 1918 to August 1919 he was the Chairman of the Ispolkom (Committee) of the Nizhny Novgorod Governorate

Nizhny Novgorod Governorate was an administrative-territorial unit (''guberniya'') of the Russian Empire, Russian Republic, and the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Russian SFSR, roughly corresponding to the Volga region, Upper and ...

. In 1919–1920, he served as governor of the Voronezh Governorate. The years 1920 to 1922 he spent in Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan is a landlocked country in Central Asia bordered by Kazakhstan to the northwest, Uzbekistan to the north, east and northeast, Afghanistan to the southeast, Iran to the south and southwest and the Caspian Sea to the west. Ash ...

as one of the leaders of the Bolshevik struggle against local Muslim

Muslims () are people who adhere to Islam, a Monotheism, monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God ...

rebels ('' basmachi''), and also commanding the succeeding punitive expeditions against local opposition.

Communist functionary

In June 1922, two months afterStalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

became the General Secretary of the Communist Party

The title of General Secretary or First Secretary is commonly used for the leaders of most communist parties. When a communist party is the ruling party of a socialist state—often labeled as communist states by external observers—the general s ...

, Kaganovich was appointed head of the party's Organisation and Instruction Department (''Orgotdel''), which was expanded a year later by absorbing the Records and Assignment Department, and renamed the Organisation-Assignment Department (''Orgraspred''). This department was responsible for all assignments within the apparatus of the Communist Party. Working there, Kaganovich helped to place Stalin's supporters in important jobs within the Communist Party bureaucracy. In this position he became noted for his great work capacity and for his personal loyalty to Stalin. He stated publicly that he would execute absolutely any order from Stalin, which at that time was a novelty.

In May 1924, Kaganovich became a full member of the Central Committee, after having first been elected as a candidate one year earlier, a member of the Orgburo

The Orgburo (), also known as the Organisational Bureau (), of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union existed from 1919 to 1952, when it was abolished at the 19th Congress of the Communist Party and its functions wer ...

, and a Secretary of the Central Committee.

From 1925 to 1928, Kaganovich was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Ukrainian SSR. In July 1926, he was also elected a candidate member of the Politburo

A politburo () or political bureau is the highest organ of the central committee in communist parties. The term is also sometimes used to refer to similar organs in socialist and Islamist parties, such as the UK Labour Party's NEC or the Poli ...

of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. He was given the task of "ukrainizatsiya" – meaning at that time the building up of Ukrainian communist popular cadres, and encouraging 'low' Ukrainian culture, by removing bureaucratic obstacles to the use of the Ukrainian language; but he treated high culture with great suspicion. He was particularly suspicious of the poet, Mykola Khvylovy, and sent Stalin a selection of quotations from Khvylovy's verses, which incited Stalin to launch an attack on the poet. He clashed frequently with the two most prominent ethnic Ukrainian Bolsheviks Vlas Chubar and Alexander Shumsky. Shumsky obtained an audience with Stalin in 1926 to insist that Kaganovich be recalled, but Kaganovich succeeded in getting Shumsky dismissed the following year, over his support for Khvylovy. Later, Stalin had a similar visit from Chubar, and the Ukraine President, Grigory Petrovsky

Grigory Ivanovich Petrovsky (, ; 4 February 1878 – 10 January 1958) was a Ukrainian Soviet politician and Old Bolshevik. He participated in signing the Treaty on the Creation of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics and the Treaty of Brest-L ...

. In 1928, Stalin reluctantly agreed to recall Kaganovich.

In Moscow, he returned to his position as a Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party, a job he held until 1939. As Secretary, he endorsed Stalin's struggle against the so-called Left

Left may refer to:

Music

* ''Left'' (Hope of the States album), 2006

* ''Left'' (Monkey House album), 2016

* ''Left'' (Helmet album), 2023

* "Left", a song by Nickelback from the album ''Curb'', 1996

Direction

* Left (direction), the relativ ...

and Right

Rights are law, legal, social, or ethics, ethical principles of freedom or Entitlement (fair division), entitlement; that is, rights are the fundamental normative rules about what is allowed of people or owed to people according to some legal sy ...

oppositions within the Communist Party, and backed Stalin's decision to enforce rapid collectivisation of agriculture, against the more moderate policy of Nikolai Bukharin

Nikolai Ivanovich Bukharin (; rus, Николай Иванович Бухарин, p=nʲɪkɐˈlaj ɪˈvanəvʲɪdʑ bʊˈxarʲɪn; – 15 March 1938) was a Russian revolutionary, Soviet politician, and Marxist theorist. A prominent Bolshevik ...

, who argued in favor of the "peaceful integration of kulaks into socialism." In summer 1930, he was warned that Lenin's widow, Nadezhda Krupskaya

Nadezhda Konstantinovna Krupskaya ( rus, links=no, Надежда Константиновна Крупская, p=nɐˈdʲeʐdə kənstɐnʲˈtʲinəvnə ˈkrupskəjə; – 27 February 1939) was a Russian revolutionary, politician and politic ...

had delivered a speech at a district party branch in Moscow, in which she criticised collectivisation. Kaganovich rushed to the meeting, and subjected Krupskaya to "coarse and scathing abuse."

In July 1930, Kaganovich was promoted to full membership of the Politburo

A politburo () or political bureau is the highest organ of the central committee in communist parties. The term is also sometimes used to refer to similar organs in socialist and Islamist parties, such as the UK Labour Party's NEC or the Poli ...

, which he retained for 27 years.

Stalin's deputy

In December 1930, whenVyacheslav Molotov

Vyacheslav Mikhaylovich Molotov (; – 8 November 1986) was a Soviet politician, diplomat, and revolutionary who was a leading figure in the government of the Soviet Union from the 1920s to the 1950s, as one of Joseph Stalin's closest allies. ...

was promoted to the post of chairman of the Soviet government, Kaganovich replaced him as Stalin's deputy in the party secretariat, a position he held until February 1935. In these four years, he was the third most powerful figure in the Soviet leadership, behind Stalin and Molotov. He was left in Moscow in charge of party affairs when Stalin was on vacation. In 2001, a collection of 836 letters and telegrams that Stalin and Kaganovich exchanged in 1931–36 were published in Russia. The bulk of them were translated and published in the US in 2003.

In 1933 and 1934, he served as the Chairman of the Commission for Vetting of the Party Membership (''Tsentralnaya komissiya po proverke partiynykh ryadov'') and ensured personally that nobody associated with anti-Stalin opposition would be permitted to remain a Communist Party member. In 1934, at the XVII Congress of the Communist Party, Kaganovich chaired the Counting Committee. He falsified voting for positions in the Central Committee, deleting 290 votes opposing the Stalin candidacy. His actions resulted in Stalin's being re-elected as the General Secretary instead of Sergey Kirov

Sergei Mironovich Kirov (born Kostrikov; 27 March 1886 – 1 December 1934) was a Russian and Soviet politician and Bolshevik revolutionary. Kirov was an early revolutionary in the Russian Empire and a member of the Bolshevik faction of the Russ ...

. By the rules, the candidate receiving fewer opposing votes should become the General Secretary. Before Kaganovich's falsification, Stalin received 292 opposing votes and Kirov only three. However, the "official" result (due to the interference of Kaganovich) saw Stalin with just two opposing votes.

In 1930–35, he was also First Secretary of the Moscow

Moscow is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Russia by population, largest city of Russia, standing on the Moskva (river), Moskva River in Central Russia. It has a population estimated at over 13 million residents with ...

Obkom of the Communist Party (1930–1935). He later headed the Moscow Gorkom of the Communist Party (1931–1934). During this period, he also supervised destruction of many of the city's oldest monuments, including the Cathedral of Christ the Saviour

The Cathedral of Christ the Saviour (, ) is a Russian Orthodox Church, Russian Orthodox cathedral in Moscow, Russia, on the northern bank of the Moskva River, a few hundred metres southwest of the Kremlin. With an overall height of , it is the ...

.Rees, Edward Afron. 1994. Stalinism and Soviet Rail Transport, 1928–41. Birmingham: Palgrave Macmilla/ref> In 1932, he led the suppression of the workers' strike in Ivanovo-Voznesensk.

Moscow Metro

In the 1930s, Kaganovich – along with project managers Ivan Kuznetsov and, later Isaac Segal – organized and led the building of the first Soviet underground rapid-transport system, theMoscow Metro

The Moscow Metro) is a rapid transit system in the Moscow Oblast of Russia. It serves the capital city of Moscow and the neighbouring cities of Krasnogorsk, Moscow Oblast, Krasnogorsk, Reutov, Lyubertsy, and Kotelniki. Opened in 1935 with one l ...

, known as ''Metropoliten imeni L.M. Kaganovicha'' after him until 1955. The decision to construct the metro was made at a plenum of the Central Committee on June 15, 1931, after a report by Kaganovich.

On October 15, 1941, L. M. Kaganovich received an order to close the Moscow Metro, and within three hours to prepare proposals for its destruction, as a strategically important object. The metro was supposed to be destroyed, and the remaining cars and equipment removed. On the morning of October 16, 1941, on the day of the panic in Moscow, the metro was not opened for the first time. It was the only day in the history of the Moscow metro when it did not work. By evening, the order to destroy the metro was canceled.

In 1955, after the death of Stalin, the Moscow Metro was renamed to no longer include Kaganovich's name.

Responsibility for the 1932–1933 famine

In July 1932, Molotov and Kaganovich travelled to

In July 1932, Molotov and Kaganovich travelled to Kharkov

Kharkiv, also known as Kharkov, is the second-largest List of cities in Ukraine, city in Ukraine.

, then the capital of Ukraine, to order the Politburo of the Ukrainian Communist party to set a quote of grain procurement of 356 million pood

''Pood'' ( rus, пуд, r=pud, p=put, plural: or ) is a unit of mass equal to 40 Funt (mass), ''funt'' (, Russian pound). Since 1899 it is set to approximately 16.38 kilograms (36.11 pound (mass), pounds). It was used in Russia, Belarus, and Ukr ...

a year. Every member of the Ukrainian Poliburo pleaded for a reduction in the quantity of grain peasants were required to hand over to the state, but Kaganovich and Molotov "categorically refused". Later the same month, they sent the Ukrainian party leaders a secret telegram ordering them to intensify grain production and impose harsh penalties on peasants who failed to comply. In August, Stalin and Kaganovich pushed through a decree that made theft or sabotage of state property, including the property of collective farms, punishable by death, and Kaganovich sent a telegram to the Ukrainian leaders on "the unsatisfactory pace of grain procurement." On 13 January 2010, years later, when the Kyiv Court of Appeal had investigated the causes of the 1932–33 famine, known as the Holodomor

The Holodomor, also known as the Ukrainian Famine, was a mass famine in Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, Soviet Ukraine from 1932 to 1933 that killed millions of Ukrainians. The Holodomor was part of the wider Soviet famine of 1930–193 ...

, the court cited these four incidents as proof that Kaganovich was complicit in an act of genocide against the Ukrainian nation. Though he and others were pronounced guilty as criminals, the case was ended immediately according to paragraph 8 of Article 6 of the Criminal Procedural Code of Ukraine. The court's ruling also referred to Kaganovich's return visit to Kharkiv in December 1932, when, during a Politburo session that lasted until 4.00 am, Ukrainians present begged that peasants should be allowed to retain more grain for their own consumption and seeds for the next year's crop, but Kaganovich overruled them and messaged Stalin accusing them of "seriously hampering and undermining the entire grain procurement."

Kaganovich also travelled to the Northern Caucasus in October 1932 to "struggle with the class enemy who sabotaged the grain collection and sowing." Meeting resistance from Cossacks, he had the entire population of 16 Cossack villages, of more than 1,000 people each, deported, and brought in peasants from less fertile land to replace them.

He also traveled to the central regions of the USSR, and Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

demanding the acceleration of collectivization and repressions against the Kulaks, who were generally blamed for the slow progress of collectivization.

Repression of Poltavskaya

Poltavskaya sabotaged and resisted collectivization period of the Soviet Union more than any other area in the Kuban which was perceived by Lazar Kaganovich to be connected to Ukrainian nationalist andCossack

The Cossacks are a predominantly East Slavic Eastern Christian people originating in the Pontic–Caspian steppe of eastern Ukraine and southern Russia. Cossacks played an important role in defending the southern borders of Ukraine and Rus ...

conspiracy. Kaganovich relentlessly pursued the policy of requisition of grain in Poltavskaya and the rest of the Kuban and personally oversaw the purging of local leaders and Cossacks. Kaganovich viewed the resistance of Poltavskaya through Ukrainian lens delivering oration in a mixed Ukrainian language. To justify this Kaganovich cited a letter allegedly written by a stanitsa

A stanitsa or stanitza ( ; ), also spelled stanycia ( ) or stanica ( ), was a historical administrative unit of a Cossack host, a type of Cossack polity that existed in the Russian Empire.

Etymology

The Russian word is the diminutive of the word ...

ataman

Ataman (variants: ''otaman'', ''wataman'', ''vataman''; ; ) was a title of Cossack and haidamak leaders of various kinds. In the Russian Empire, the term was the official title of the supreme military commanders of the Cossack armies. The Ukra ...

(local Cossack leader) named Grigorii Omel'chenko advocating Cossack separatism and local reports of resistance to collectivization in association with this figure to substantiate this suspicion of the area. However Kaganocvich did not reveal in speeches throughout the region that many of those targeted by persecution in Poltavskaya had their family members and friends deported or shot including in years before the supposed Omel'chenko crisis even started. Ultimately due to being perceived as the most rebellious area almost all (or 12,000) members of the Poltavskaya stanitsa were deported to the north. This coincided with and was a part of a wider deportation of 46,000 Cossacks from Kuban. At the same time, Poltavskaya was renamed Krasnoarmeyskaya ().ПОЛТАВСЬКА СТАНИЦЯEncyclopedia of History of Ukraine

"Iron Lazar"

In spring 1935, Kaganovich was replaced as the secretary in charge of party organisation, and as chairman of the purge commission, by

In spring 1935, Kaganovich was replaced as the secretary in charge of party organisation, and as chairman of the purge commission, by Nikolai Yezhov

Nikolai Ivanovich Yezhov ( rus, Николай Иванович Ежов, p=nʲɪkɐˈlaj ɪˈvanəvʲɪtɕ (j)ɪˈʐof; 1 May 1895 – 4 February 1940), also spelt Ezhov, was a Soviet Chekism, secret police official under Joseph Stalin who ...

, the future head of the NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (, ), abbreviated as NKVD (; ), was the interior ministry and secret police of the Soviet Union from 1934 to 1946. The agency was formed to succeed the Joint State Political Directorate (OGPU) se ...

, whose rise was a harbinger of the Great Purge

The Great Purge, or the Great Terror (), also known as the Year of '37 () and the Yezhovshchina ( , ), was a political purge in the Soviet Union that took place from 1936 to 1938. After the Assassination of Sergei Kirov, assassination of ...

. Kaganovich had handpicked Yezhov in 1933 to be deputy head of the purge commission, significantly boosting his career. In March 1935, Kaganovich was replaced as first secretary of the Moscow party organisation, by Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and the Premier of the Soviet Union, Chai ...

.

From February 1935 to 1937, Kaganovich was Narkom

A People's Commissariat (; Narkomat) was a structure in the Soviet state (in the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, in other union and autonomous republics, in the Soviet Union) from 1917–1946 which functioned as the central executive ...

(Minister) for the railways

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport using wheeled vehicles running in tracks, which usually consist of two parallel steel rails. Rail transport is one of the two primary means of land transport, next to roa ...

. This was the first step in his eventual switch from party to economic work, but in 1935, he played a significant role in preparations for the Great Purge. Even before it started, he organized the arrests of thousands of railway administrators and managers accused of sabotage.. Before the opening of the first of the Moscow show trials in August 1936, Kaganovich and Yezhov jointly reported to Stalin, who was on vacation, about progress in forcing the defendants to confess. He was also in Moscow to facilitate Yezhov's appointment as head of the NKVD, after Stalin had demanded the sacking of the incumbent, Genrikh Yagoda

Genrikh Grigoryevich Yagoda (, born Yenokh Gershevich Iyeguda; 7 November 1891 – 15 March 1938) was a Soviet secret police official who served as director of the NKVD, the Soviet Union's security and intelligence agency, from 1934 to 1936. A ...

, which Kaganovich praised as a "remarkable and wise decision of our father."

During the Great Purge, Kaganovich was sent from Moscow to Ivanovo

Ivanovo (, ) is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, city in Russia and the administrative center and largest city of Ivanovo Oblast, located northeast of Moscow and approximately from Yaroslavl, Vladimir, Russia, Vladimir and Kostroma. ...

, the Kuban

Kuban ( Russian and Ukrainian: Кубань; ) is a historical and geographical region in the North Caucasus region of southern Russia surrounding the Kuban River, on the Black Sea between the Don Steppe, the Volga Delta and separated fr ...

, Smolensk

Smolensk is a city and the administrative center of Smolensk Oblast, Russia, located on the Dnieper River, west-southwest of Moscow.

First mentioned in 863, it is one of the oldest cities in Russia. It has been a regional capital for most of ...

and elsewhere, to instigate sackings and arrests. In Ivanovo, he ordered the arrests of the provincial party secretary, and the head of the propaganda department, and accused a majority of the executive of being "enemies of the people". His visit became known as the "black tornado".

In all Party conferences of the later 1930s, he made speeches demanding increased efforts in the search for and prosecution of "foreign spies" and "saboteurs." For his ruthlessness in the execution of Stalin's orders, he was nicknamed "Iron Lazar." During his time serving as Railways Commissar, Kaganovich participated in the murder of 36,000 people by signing death lists. Kaganovich had exterminated so many railwaymen that one official called to warn that one line was entirely unmanned. In 1936–39, Kaganovich's signature appears on 188 out of 357 documented execution lists.

Kaganovich was appointed People's Commissar for Heavy Industry after his predecessor, Sergo Ordzhonikidze

Sergo Konstantinovich Ordzhonikidze, ; (born Grigol Konstantines dze Orjonikidze; 18 February 1937) was an Old Bolshevik and a Soviet statesman.

Born and raised in Georgia, in the Russian Empire, Ordzhonikidze joined the Bolsheviks at an e ...

committed suicide, in February 1937. In August 1938, he was named as a Deputy Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars. In 1939, he was appointed People's Commissar for the Oil Industry. During World War II (known as the Great Patriotic War

The Eastern Front, also known as the Great Patriotic War (term), Great Patriotic War in the Soviet Union and its successor states, and the German–Soviet War in modern Germany and Ukraine, was a Theater (warfare), theatre of World War II ...

in the USSR), Kaganovich was Commissar (Member of the Military Council) of the North Caucasian and Transcaucasian Fronts. During 1943–1944, he was again the Narkom for the railways. In 1943, he was presented with the title of Hero of Socialist Labour

The Hero of Socialist Labour () was an Title of honor, honorific title in the Soviet Union and other Warsaw Pact countries from 1938 to 1991. It represented the highest degree of distinction in the USSR and was awarded for exceptional achievem ...

. From 1944 to 1947, Kaganovich was the Minister for Building Materials

The Ministry of Construction Materials Industry (Minstroymaterialov; ) was a government ministry in the Soviet Union.

Originally established in 1939: disestablished in 1957; reestablished in 1963 as State Committee and renamed Ministry of Construc ...

.

Kaganovich's NKPS ( People's Commissariat of Communication Routes of the Soviet Union) was largely responsible for organizing the deportation of the Volga Germans

The Volga Germans (, ; ) are ethnic Germans who settled and historically lived along the Volga River in the region of southeastern European Russia around Saratov and close to Ukraine nearer to the south.

Recruited as immigrants to Russia in the ...

in 1941. Even though the forcible transfer of populations was determined to be a crime against humanity

Crimes against humanity are certain serious crimes committed as part of a large-scale attack against civilians. Unlike war crimes, crimes against humanity can be committed during both peace and war and against a state's own nationals as well as ...

at the Nuremberg trials #REDIRECT Nuremberg trials

{{redirect category shell, {{R from other capitalisation{{R from move ...

, Kaganovich never faced trial for his actions.

Political decline

Politically, Kaganovich was a much diminished figure after the war. An early sign of his weakened position was that in 1941, his brother, Mikhail, committed suicide when facing arrest, just after the German invasion. Lazar Kaganovich reputedly made no attempt to help him. When the State Defence Committee was formed to direct the war, Kaganovich was initially excluded, though he was co-opted in February 1942. In 1946, he was officially ranked ninth in seniority in the Kremlin pecking order. In 1947, after Ukraine had failed to deliver its grain quota in the wake of a drought, Kaganovich was sent to replace Khrushchev as First Secretary of the Ukrainian CP, while Khrushchev was downgraded to the post of head of government. However, Kaganovich was recalled and Khrushchev reinstated in December 1947. From 1949, until Stalin's death in March 1953, Kaganovich was in a precarious situation because of the state-sponsored anti-semitism, culminating in theSlánský trial

The Slánský trial (officially English: "Trial of the Leadership of the Anti-State Conspiracy Centre Headed by Rudolf Slánský") was a 1952 antisemiticBlumenthal, Helaine. (2009). Communism on Trial: The Slansky Affair and Anti-Semitism in P ...

in Prague, and the Doctors' plot

The "doctors' plot" () was a Soviet state-sponsored anti-intellectual and anti-cosmopolitan campaign based on a conspiracy theory that alleged an anti-Soviet cabal of prominent medical specialists, including some of Jewish ethnicity, intend ...

, during which hundreds of Jews, including Molotov's wife, Polina Zhemchuzhina

Polina Semyonovna Zhemchuzhina. (born Perl Solomonovna Karpovskaya; 27 February 1897 – 1 April 1970) was a Soviet politician and the wife of the Soviet foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov. Zhemchuzhina was the director of the Soviet national ...

, were arrested, and many were tortured and shot. Kaganovich remained in office throughout, as the most prominent Jew in the Soviet leadership, but was no longer invited to meet Stalin socially, and "was lying low, watching the course of events in fear and trembling".

From 1948 to 1952, he was the Chairman of Gossnab (State Committee for Material-Technical Supply, charged with the primary responsibility for the allocation of producer goods to enterprises, a critical state function in the absence of markets).

After Stalin's death, Kaganovich appeared to regain some of the influence he had lost. In March 1953, he was appointed one of four First Vice-Premiers of the Council of Ministers

Council of Ministers is a traditional name given to the supreme Executive (government), executive organ in some governments. It is usually equivalent to the term Cabinet (government), cabinet. The term Council of State is a similar name that also m ...

, and confirmed as a full member of the ten-man Praesidium (the new name given to the Politburo), and on 24 May 1955, he was appointed the first Chairman of Goskomtrud.

But his position rapidly deteriorated with the rise of Nikita Khrushchev. In the 1930s, he had been Khrushchev's mentor, but Khrushchev had not forgiven the interlude when Kaganovich supplanted him as the Ukrainian party leader in 1947, and had come to despise him. In his memoirs, Khrushchev wrote:

In 1956–57, Kaganovich joined Molotov, Georgy Malenkov

Georgy Maximilianovich Malenkov (8 January 1902 O.S. 26 December 1901">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="/nowiki>Old Style and New Style dates">O.S. 26 December 1901ref name=":6"> – 14 January 1988) was a Soviet politician who br ...

, and Dmitri Shepilov in an attempt to remove Khrushchev from office, partly in reaction against Khrushchev's Secret Speech

"On the Cult of Personality and Its Consequences" () was a report by Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, made to the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union on 25 Februa ...

in February 1956, denouncing Stalin and the persecution of innocent party officials. On 6 June 1956, Kaganovich was removed from the chairmanship of the State Committee on Labour and Wages. When the Central Committee convened to resolve this dispute, in June 1957, Kaganovich was accused of "inactivity and crude violations of revolutionary legality" in his management of the state committees he chaired, and was expelled from the Praesidium, with the other three members of what was now officially called the Anti-Party Group'. He was reportedly terrified that he would be arrested and shot, and phoned Khrushchev to beg for clemency. He was given the job of director of a small potash

Potash ( ) includes various mined and manufactured salts that contain potassium in water- soluble form.

works in the Urals

The Ural Mountains ( ),; , ; , or simply the Urals, are a mountain range in Eurasia that runs north–south mostly through Russia, from the coast of the Arctic Ocean to the river Ural (river), Ural and northwestern Kazakhstan.

.

In 1961, Kaganovich was expelled from the Party and became a pensioner living in Moscow. His grandchildren reported that after his dismissal from the Central Committee, Kaganovich (who had a reputation for his temperamental and allegedly violent nature) never shouted again and became a devoted grandfather.

In 1984, his re-admission to the Party was considered by the Politburo, alongside that of Molotov. During the last years of life he played dominoes with fellow pensionersL. M. Kaganovich, Stalwart of Stalin, Dies at 97/ref> and criticized Soviet media attacks on Stalin: "First, Stalin is disowned, now, little by little, it gets to prosecute socialism, the October Revolution, and in no time they will also want to prosecute Lenin and Marx." Shortly before death he suffered a heart attack. In 1991 Kaganovich was interviewed about the alleged murder of Lenin's widow, in which he suggested

Lavrentiy Beria

Lavrentiy Pavlovich Beria ka, ლავრენტი პავლეს ძე ბერია} ''Lavrenti Pavles dze Beria'' ( – 23 December 1953) was a Soviet politician and one of the longest-serving and most influential of Joseph ...

may have been involved with Krupskaya's poisoning and was quoted in 1991 saying "I can't dismiss that possibility. He might have." Russian writer Arkady Vaksberg further commented that the fact Kaganovich had confirmed the poisoning "did actually take place is more important than specifying who ordered it."

Kaganovich died on July 25, 1991, at the age of 97, just before the events

Event may refer to:

Gatherings of people

* Ceremony, an event of ritual significance, performed on a special occasion

* Convention (meeting), a gathering of individuals engaged in some common interest

* Event management, the organization of eve ...

that resulted in the end of the USSR. He is buried at the Novodevichy Cemetery

Novodevichy Cemetery () is a cemetery in Moscow. It lies next to the southern wall of the 16th-century Novodevichy Convent, which is the city's third most popular tourist site.

History

The cemetery was designed by Ivan Mashkov and inaugurated ...

in Moscow.

'Rosa Kaganovich'

In 1987, Americanjournalist

A journalist is a person who gathers information in the form of text, audio or pictures, processes it into a newsworthy form and disseminates it to the public. This is called journalism.

Roles

Journalists can work in broadcast, print, advertis ...

Stuart Kahan published a book entitled ''The Wolf of the Kremlin: The First Biography of L.M. Kaganovich, the Soviet Union's Architect of Fear'' (William Morrow & Co

William Morrow and Company is an American publishing company founded by William Morrow in 1926. The company was acquired by Scott Foresman in 1967, sold to Hearst Corporation in 1981, and sold to News Corporation (now News Corp) in 1999. The c ...

). In the book, Kahan claimed to be Kaganovich's long-lost nephew, and claimed to have interviewed Kaganovich personally and stated that Kaganovich admitted to being partially responsible for the death of Stalin in 1953 (supposedly by poisoning). A number of other unusual claims were made as well, including that Stalin was married to a sister of Kaganovich (supposedly named "Rosa") during the last year of his life and that Kaganovich (who was raised Jewish) was the architect of anti-Jewish pogrom

A pogrom is a violent riot incited with the aim of Massacre, massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe late 19th- and early 20th-century Anti-Jewis ...

s.Kahan, Stuart. ''The Wolf of the Kremlin: The First Biography of L.M. Kaganovich, the Soviet Union's Architect of Fear'' (William Morrow & Co, 1987)

The rumor that Stalin married a sister of Kaganovich after the death of Nadezhda Alliluyeva in 1932 seems to have originated in the 1930s. Elizabeth Lermolo, who emigrated to the US in 1950 and published a memoir, ''Face of a Victim'' reported hearing the story while she was a prisoner in the gulag

The Gulag was a system of Labor camp, forced labor camps in the Soviet Union. The word ''Gulag'' originally referred only to the division of the Chronology of Soviet secret police agencies, Soviet secret police that was in charge of runnin ...

.Lermolo, Elizabeth . ''Face of a Victim'' (Harper & Brothers, 1955) The story has been repeated in sources including ''The Rise and Fall of Stalin'', (1965) by Robert Payne, ''The Private Life of Josif Stalin'' (1962) by Jack Fishman and Bernard Hutton, and in ''Stalin: the History of a Dictator'' (1982) by Harford Montgomery Hyde. There were also frequent mentions of 'Rosa Kaganovich' in western media including ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

'', ''Time

Time is the continuous progression of existence that occurs in an apparently irreversible process, irreversible succession from the past, through the present, and into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequ ...

'' and ''Life

Life, also known as biota, refers to matter that has biological processes, such as Cell signaling, signaling and self-sustaining processes. It is defined descriptively by the capacity for homeostasis, Structure#Biological, organisation, met ...

''. The story of Rosa Kaganovich was mentioned by Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky,; ; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky'' was a Russian revolutionary, Soviet politician, and political theorist. He was a key figure ...

, who alleged that "Stalin married the sister of Kaganovich, thereby presenting the latter with hopes for a promising future."

After ''The Wolf of the Kremlin'' was translated into Russian by Progress Publishers, and a chapter from it printed in the ''Nedelya'' (''Week'') newspaper in 1991, remaining members of Kaganovich's family composed the ''Statement of the Kaganovich Family'' in response. The statement disputed all of Kahan's claims. The family denied that Kaganovich ever had a sister called Rosa, though he had a niece of that name, who was 13 years old in the year when Stalin's second wife committed suicide. Stalin's daughter, Svetlana Alliluyeva was equally emphatic, writing in a memoir published in 1969:

After the fall of Communism

The revolutions of 1989, also known as the Fall of Communism, were a revolutionary wave of liberal democracy movements that resulted in the collapse of most Marxist–Leninist governments in the Eastern Bloc and other parts of the world. Th ...

in 1991, it became possible for historians to search for evidence in the archives. There is no mention of 'Rosa Kaganovich' in the hundreds of published letters and telegrams found in the archives that Stalin and Kaganovich exchanged in the period when, supposedly, they were brothers-in-law. Simon Sebag Montefiore mentioned her in his detailed study of life in the Kremlin under Stalin, but only to say that "it seems this particular story is a myth." He added:

Personal life

Kaganovich entered the workforce at the age of 13, an event which would shape his aesthetics and preferences through adulthood. Stalin himself confided to Kaganovich that the latter had a much greater fondness and appreciation for the proletariat. As his favorability with Stalin rose, Kaganovich felt compelled to rapidly fill the noticeable gaps in his education and upbringing. Stalin, upon noticing that Kaganovich could not use commas properly, gave Kaganovich three months' leave to undertake a rapid course in grammar. Kaganovich was married to Maria Markovna Kaganovich (née Privorotskaya) (1894–1961), a fellow assimilated Kievan Jew who was part of the revolutionary effort since 1909. Mrs Kaganovich spent many years as a powerful municipal official, directly ordering the demolition of the Iberian Gate and Chapel and

Kaganovich was married to Maria Markovna Kaganovich (née Privorotskaya) (1894–1961), a fellow assimilated Kievan Jew who was part of the revolutionary effort since 1909. Mrs Kaganovich spent many years as a powerful municipal official, directly ordering the demolition of the Iberian Gate and Chapel and Cathedral of Christ the Saviour

The Cathedral of Christ the Saviour (, ) is a Russian Orthodox Church, Russian Orthodox cathedral in Moscow, Russia, on the northern bank of the Moskva River, a few hundred metres southwest of the Kremlin. With an overall height of , it is the ...

. The couple had two children: a daughter, named Maya, and an adopted son, Yuri. Much attention has been devoted by historians to Kaganovich's Jewishness, and how it conflicted with Stalin's biases. Kaganovich frequently found it necessary to allow great cruelties to occur to his family to preserve Stalin's trust in him, such as allowing his brother to be coerced into suicide.

The Kaganovich family initially lived, as most high-level Soviet functionaries in the 1930s, a conservative lifestyle in modest conditions. This changed when Stalin entrusted the construction of the Moscow Metro to Kaganovich. The family moved into a luxurious apartment near ground zero ( Sokolniki station), located at 3 Pesochniy Pereulok (Sandy Lane). Kaganovich's apartment consisted of two floors (an extreme rarity in the USSR), a private access garage, and a designated space for butlers, security, and drivers.

Decorations and awards

*Order of Lenin

The Order of Lenin (, ) was an award named after Vladimir Lenin, the leader of the October Revolution. It was established by the Central Executive Committee on 6 April 1930. The order was the highest civilian decoration bestowed by the Soviet ...

, four times

*Order of the Red Banner of Labour

The Order of the Red Banner of Labour () was an order of the Soviet Union established to honour great deeds and services to the Soviet state and society in the fields of production, science, culture, literature, the arts, education, sports ...

(27 October 1938)

*Hero of Socialist Labour

The Hero of Socialist Labour () was an Title of honor, honorific title in the Soviet Union and other Warsaw Pact countries from 1938 to 1991. It represented the highest degree of distinction in the USSR and was awarded for exceptional achievem ...

(5 November 1943)

Notes

References

Further reading

* * Fitzpatrick, S. (1996). '' Stalin's Peasants: Resistance and Survival in the Russian Village after Collectivization.'' New York: Oxford University Press. *——. (1999). '' Everyday Stalinism: Ordinary Life in Extraordinary Times: Soviet Russia in the 1930s.'' New York: Oxford University Press. * Kotkin, S. (2017). '' Stalin: Waiting for Hitler, 1929–1941''. New York: Random House. * * Radzinsky, Edvard, (1996) ''Stalin'', Doubleday (English translation edition), 1996. *Rees, E.A. ''Iron Lazar: A Political Biography of Lazar Kaganovich'' (Anthem Press; 2012) 373 pages; scholarly biography *Rubenstein, Joshua, ''The Last Days of Stalin'', (Yale University Press: 2016)External links

Profile at http://www.hrono.ru

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Kaganovich, Lazar 1893 births 1991 deaths Stalinism Anti-revisionists Burials at Novodevichy Cemetery Deputy heads of government of the Soviet Union Expelled members of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union First convocation members of the Verkhovna Rada of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic First secretaries of the Communist Party of Ukraine (Soviet Union) Genocide perpetrators Great Purge perpetrators Heroes of Socialist Labour Holodomor Jewish socialists Jewish Soviet politicians Old Bolsheviks People from Kiev Governorate Politicians from Kyiv Oblast People's Commissariat of Heavy Industry People's commissars and ministers of the Soviet Union Members of the Orgburo of the 15th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Orgburo of the 16th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Orgburo of the 17th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Orgburo of the 18th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Secretariat of the 13th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Secretariat of the 14th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Secretariat of the 15th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Secretariat of the 16th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Secretariat of the 17th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Candidates of the Politburo of the 14th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Candidates of the Politburo of the 15th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Politburo of the 16th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Politburo of the 17th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Politburo of the 18th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Presidium of the 19th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union Members of the Presidium of the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union Candidates of the Central Committee of the 12th Congress of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 13th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 14th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 15th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 16th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 17th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 18th Congress of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Members of the Central Committee of the 19th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union Members of the Central Committee of the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union Anti-Party Group Recipients of the Order of Lenin Recipients of the Order of the Red Banner of Labour Russian Social Democratic Labour Party members Soviet people of World War II Ukrainian communists Russian Constituent Assembly members