Lake Uniamési on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Lake Uniamési or the Uniamesi Sea was the name given by missionaries in the 1840s and 1850s to a huge lake or inland sea they supposed to lie within a region of Central East Africa with the same name.

Three missionaries, confined to the coastal belt, heard of the region of

The Great Lakes of East Africa include lakes

The Great Lakes of East Africa include lakes

Early in 1844 Sultan Sayyid Said gave the German missionary

Early in 1844 Sultan Sayyid Said gave the German missionary

Jakob Erhardt spent six months at Tanga studying the Kisambara language, where he heard the stories of ivory traders who had visited the interior. According to Rebmann, whose account was published in Krapf's memoirs,

Erhardt was struck by the fact that various travelers who had gone inland from different points on the east coast of Africa had all come to an inland sea, and made a map based on available information, including the findings of Krapf and Rebmann.

In November 1854 while talking about the problem to Rebmann, "at one and the same moment, the problem flashed on both of us solved by the simple supposition that where geographical hypothesis had hitherto supposed an enormous mountain-land, we must now look for an enormous valley and an inland sea." On the map that he and Rebmann drew the three lakes are shown as one very large S-shaped lake.

In 1855 Erhardt was repatriated due to poor health, and took the map with him.

Rebmann wrote letters to the ''Calwer Missionary Intelligencer (Calwer Missionsblatt)'', received and published in 1855, in which he called the lake Uniamesi or Ukerewe. He said that according to accounts by traders, considered trustworthy by the missionaries, the lake extended from latitude 0.5°N to 13.5°S and from longitude 23.5°E to 36°E, and had an area of 13,600 German square miles, as compared to 7,860 German square miles for the Black Sea and 7,400 for the Caspian.

The map was first published in the ''Calwer Missionsblatt'' later in 1855, and then in the ''Church Missionary intelligencer'' in 1856.

Jakob Erhardt spent six months at Tanga studying the Kisambara language, where he heard the stories of ivory traders who had visited the interior. According to Rebmann, whose account was published in Krapf's memoirs,

Erhardt was struck by the fact that various travelers who had gone inland from different points on the east coast of Africa had all come to an inland sea, and made a map based on available information, including the findings of Krapf and Rebmann.

In November 1854 while talking about the problem to Rebmann, "at one and the same moment, the problem flashed on both of us solved by the simple supposition that where geographical hypothesis had hitherto supposed an enormous mountain-land, we must now look for an enormous valley and an inland sea." On the map that he and Rebmann drew the three lakes are shown as one very large S-shaped lake.

In 1855 Erhardt was repatriated due to poor health, and took the map with him.

Rebmann wrote letters to the ''Calwer Missionary Intelligencer (Calwer Missionsblatt)'', received and published in 1855, in which he called the lake Uniamesi or Ukerewe. He said that according to accounts by traders, considered trustworthy by the missionaries, the lake extended from latitude 0.5°N to 13.5°S and from longitude 23.5°E to 36°E, and had an area of 13,600 German square miles, as compared to 7,860 German square miles for the Black Sea and 7,400 for the Caspian.

The map was first published in the ''Calwer Missionsblatt'' later in 1855, and then in the ''Church Missionary intelligencer'' in 1856.

Burton and Speke reached Zanzibar on 20 December 1857, visited Rebmann at his Kisuludini mission station, and paid a visit to Fuga, capital of the Usambare kingdom. Burton met king

Burton and Speke reached Zanzibar on 20 December 1857, visited Rebmann at his Kisuludini mission station, and paid a visit to Fuga, capital of the Usambare kingdom. Burton met king

Unyamwezi

Unyamwezi or Unyamwezi states and kingdoms (''Falme za Unyamwezi'' in Swahili) is a historical region and former Pre-colonial states in what is now modern central Tanzania, around the modern city of Tabora in Tabora Region to the south of La ...

in the northwest of what is now Tanzania and exaggerated its size to include a large part of the continental interior. They heard of a great lake, and imagined an enormous lake that would be the source of the Benue, Nile

The Nile (also known as the Nile River or River Nile) is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa. It has historically been considered the List of river sy ...

, Zambezi

The Zambezi (also spelled Zambeze and Zambesi) is the fourth-longest river in Africa, the longest east-flowing river in Africa and the largest flowing into the Indian Ocean from Africa. Its drainage basin covers , slightly less than half of t ...

and Congo rivers. They drew a map showing a huge "Lake Uniamesi" that was published in 1855. The map spurred the expedition of Burton and Speke

Speke () is a suburb of Liverpool, Merseyside, England. It is southeast of the city centre. Located near the widest part of the River Mersey, it is bordered by the suburbs of Garston and Hunts Cross, and nearby to Halewood, Hale Village, ...

to investigate the African Great Lakes

The African Great Lakes (; ) are a series of lakes constituting the part of the Rift Valley lakes in and around the East African Rift. The series includes Lake Victoria, the second-largest freshwater lake in the world by area; Lake Tangan ...

region, where they found that lakes Victoria

Victoria most commonly refers to:

* Queen Victoria (1819–1901), Queen of the United Kingdom and Empress of India

* Victoria (state), a state of Australia

* Victoria, British Columbia, Canada, a provincial capital

* Victoria, Seychelles, the capi ...

, Tanganyika and Nyasa were separate bodies of water. It was not until 1877 that it was confirmed that these lakes did feed the Nile, Congo and Zambezi, albeit separately.

Background

Albert

Albert may refer to:

Companies

* Albert Computers, Inc., a computer manufacturer in the 1980s

* Albert Czech Republic, a supermarket chain in the Czech Republic

* Albert Heijn, a supermarket chain in the Netherlands

* Albert Market, a street mar ...

, Edward

Edward is an English male name. It is derived from the Anglo-Saxon name ''Ēadweard'', composed of the elements '' ēad'' "wealth, fortunate; prosperous" and '' weard'' "guardian, protector”.

History

The name Edward was very popular in Anglo-S ...

, Kivu

Kivu is the name for a large region in the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo that borders Lake Kivu. It was a ''Région'' (read 'province') of the country under the rule of Mobutu Sese Seko from 1966 to 1988. As an official ''Région'' ...

and Tanganyika, all of which lie in the western or Albertine branch of the East African rift system, Lake Victoria

Lake Victoria is one of the African Great Lakes. With a surface area of approximately , Lake Victoria is Africa's largest lake by area, the world's largest tropics, tropical lake, and the world's second-largest fresh water lake by surface are ...

to the east of this chain and Lake Nyasa (Malawi

Malawi, officially the Republic of Malawi, is a landlocked country in Southeastern Africa. It is bordered by Zambia to the west, Tanzania to the north and northeast, and Mozambique to the east, south, and southwest. Malawi spans over and ...

) to the south. Lake Victoria is the third largest lake in the world, and lies on the plateau between the west and east rifts. Unlike the long, narrow and deep lakes of the rift, Lake Victoria is wide and relatively shallow.

Bantu peoples

The Bantu peoples are an Indigenous peoples of Africa, indigenous ethnolinguistic grouping of approximately 400 distinct native Demographics of Africa, African List of ethnic groups of Africa, ethnic groups who speak Bantu languages. The language ...

moved into the region between the Great Lakes and the Indian Ocean some time after 1000 BC and mingled with the local population. By the first century AD ships from the Arabian peninsula were trading along the East African coast. Muslim Arab

Arabs (, , ; , , ) are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in West Asia and North Africa. A significant Arab diaspora is present in various parts of the world.

Arabs have been in the Fertile Crescent for thousands of years ...

s from Oman

Oman, officially the Sultanate of Oman, is a country located on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula in West Asia and the Middle East. It shares land borders with Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Yemen. Oman’s coastline ...

began to colonize the coast in the 8th century AD. The coastal Bantu peoples intermarried with the Arabs to form the Swahili people

The Swahili people (, وَسوَحِيلِ) comprise mainly Bantu, Afro-Arab, and Comorian ethnic groups inhabiting the Swahili coast, an area encompassing the East African coast across southern Somalia, Kenya, Tanzania, and northern Mozambi ...

, with a language that combines Bantu, Arabic and Persian elements. The Swahili culture incorporated many Arabic and Islamic aspects, while remaining essentially Bantu in nature.

The Unyamwezi

Unyamwezi or Unyamwezi states and kingdoms (''Falme za Unyamwezi'' in Swahili) is a historical region and former Pre-colonial states in what is now modern central Tanzania, around the modern city of Tabora in Tabora Region to the south of La ...

region lies around the modern town of Tabora

Tabora is the capital of Tanzania's Tabora Region and is classified as a municipality by the Tanzanian government. It is also the administrative seat of Tabora Urban District. According to the 2012 census, the district had a population of 226, ...

, between the coast and Lake Tanganyika, and includes the Tabora

Tabora is the capital of Tanzania's Tabora Region and is classified as a municipality by the Tanzanian government. It is also the administrative seat of Tabora Urban District. According to the 2012 census, the district had a population of 226, ...

, Nzega

Nzega is a city in central Tanzania. It is the district headquarter of Nzega District.

Transport

Paved Trunk roads T3 from Morogoro to the Rwanda border and T8 from Tabora to Mwanza

Mwanza City, also known as Rock City to the residents, is a ...

and Kahama districts of the western plateau of modern Tanzania

Tanzania, officially the United Republic of Tanzania, is a country in East Africa within the African Great Lakes region. It is bordered by Uganda to the northwest; Kenya to the northeast; the Indian Ocean to the east; Mozambique and Malawi to t ...

. In the 19th century the inhabitants were called Nyamwezi people

The Nyamwezi are one of the Bantu groups of East Africa. They are the second-largest ethnic group in Tanzania. The Nyamwezi people's ancestral homeland is in parts of Tabora Region, Singida Region, Shinyanga Region and Katavi Region. The term ...

by outsiders, although this term covered various different groups.

Unyamwezi lay at a juncture where a trade route from the coast split, with one branch continuing west to the port of Ujiji

Ujiji is the oldest town in western Tanzania and is located in Kigoma-Ujiji District of Kigoma Region. Originally a Swahili settlement and then an Arab slave trading post by the mid-nineteenth century nominally under the Sultanate of Zanziba ...

on Lake Tanganyika while another branch led north to the kingdoms of Buganda

Buganda is a Bantu peoples, Bantu kingdom within Uganda. The kingdom of the Baganda, Baganda people, Buganda is the largest of the List of current non-sovereign African monarchs, traditional kingdoms in present-day East Africa, consisting of Ug ...

and Bunyoro

Bunyoro, also called Bunyoro-Kitara, is a traditional Bantu kingdom in Western Uganda. It was one of the most powerful kingdoms in Central and East Africa from the 16th century to the 19th century. It is ruled by the King ('' Omukama'') of ...

.

Coastal traders settled in Unyamwezi, some with hundreds of well-armed retainers.

The Nyamwezi provided most of the porters for the caravans organized by the coastal Arabs and Swahilis,

and also conducted their own caravans. The Nyamwezi were long-distance traders throughout East Africa.

Ivory was not widely used by the Nyamwezi, but at some point they became aware that there was an overseas market for the product, and began to carry ivory along the route from Tabora down to the Indian Ocean coast opposite Zanzibar. There are records of Sultan Sayyid Said

Sayyid Saïd bin Sultan al-Busaidi (, , ) (5 June 1791 – 19 October 1856) was Sultan of Muscat and Oman, the fifth ruler of the Al Bu Said dynasty from 1804 to 4 June 1856. His rule began after a period of conflict and internecine rivalry of su ...

of Zanzibar

Zanzibar is a Tanzanian archipelago off the coast of East Africa. It is located in the Indian Ocean, and consists of many small Island, islands and two large ones: Unguja (the main island, referred to informally as Zanzibar) and Pemba Island. ...

negotiating with envoys from Unyamwezi in 1839 for safe passage for caravans to the interior.

The Nyamwezi did not sell their own people as slaves, since they needed manpower for the ivory trade, but after the 1850s the slave trade began to become important. Slaves brought from the Congo Basin

The Congo Basin () is the sedimentary basin of the Congo River. The Congo Basin is located in Central Africa, in a region known as west equatorial Africa. The Congo Basin region is sometimes known simply as the Congo. It contains some of the larg ...

or the Great Lakes region would be held at Tabora, then sent down to the coast in small groups for onward shipment.

Early European contacts

Early in 1844 Sultan Sayyid Said gave the German missionary

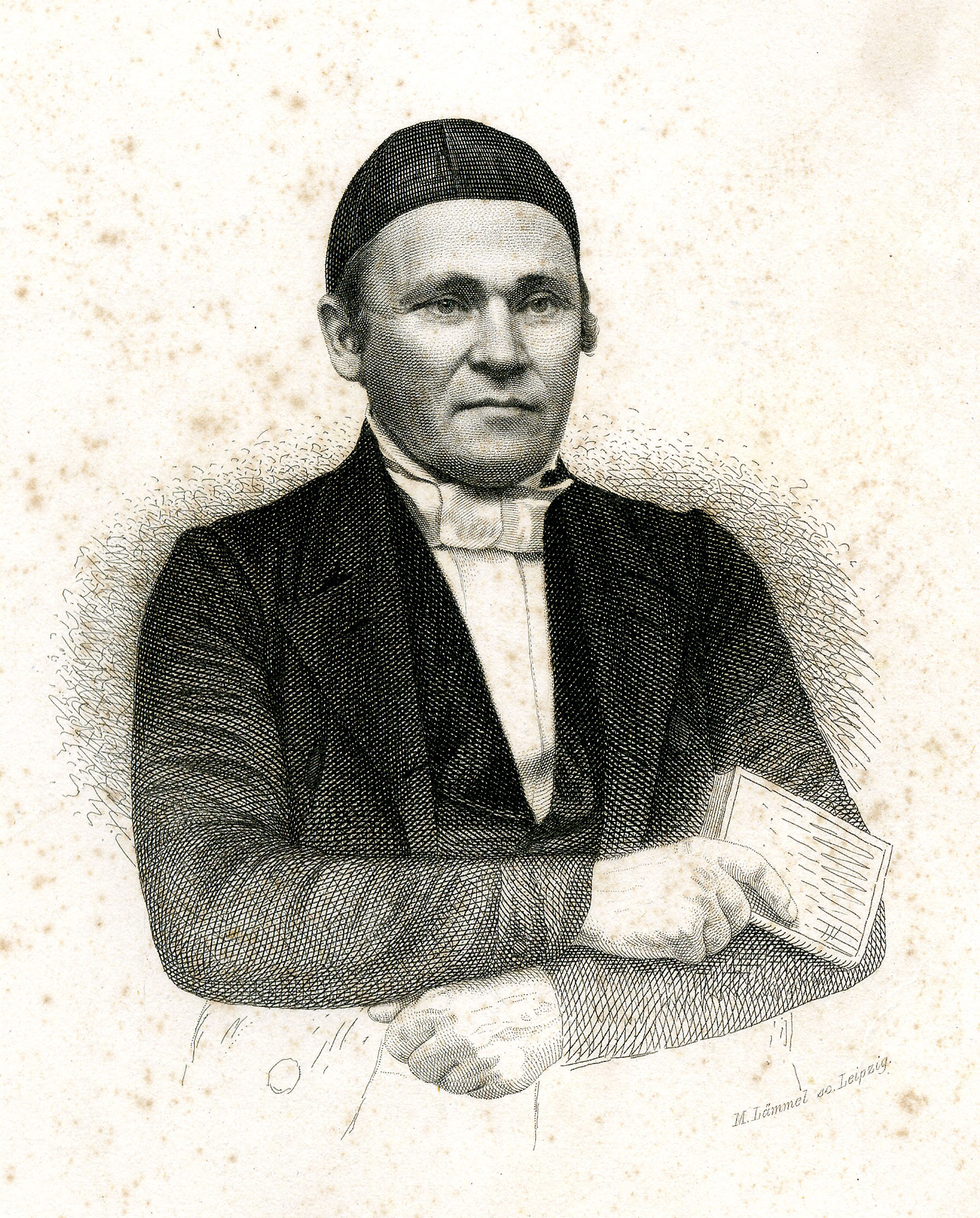

Early in 1844 Sultan Sayyid Said gave the German missionary Johann Ludwig Krapf

Johann Ludwig Krapf (11 January 1810 – 26 November 1881) was a German missionary in East Africa, as well as an explorer, linguist, and traveler. Krapf played an important role in exploring East Africa with Johannes Rebmann. They were the firs ...

(1810–1881) permission to establish a mission on the coast. Krapf arrived in Mombasa

Mombasa ( ; ) is a coastal city in southeastern Kenya along the Indian Ocean. It was the first capital of British East Africa, before Nairobi was elevated to capital status in 1907. It now serves as the capital of Mombasa County. The town is ...

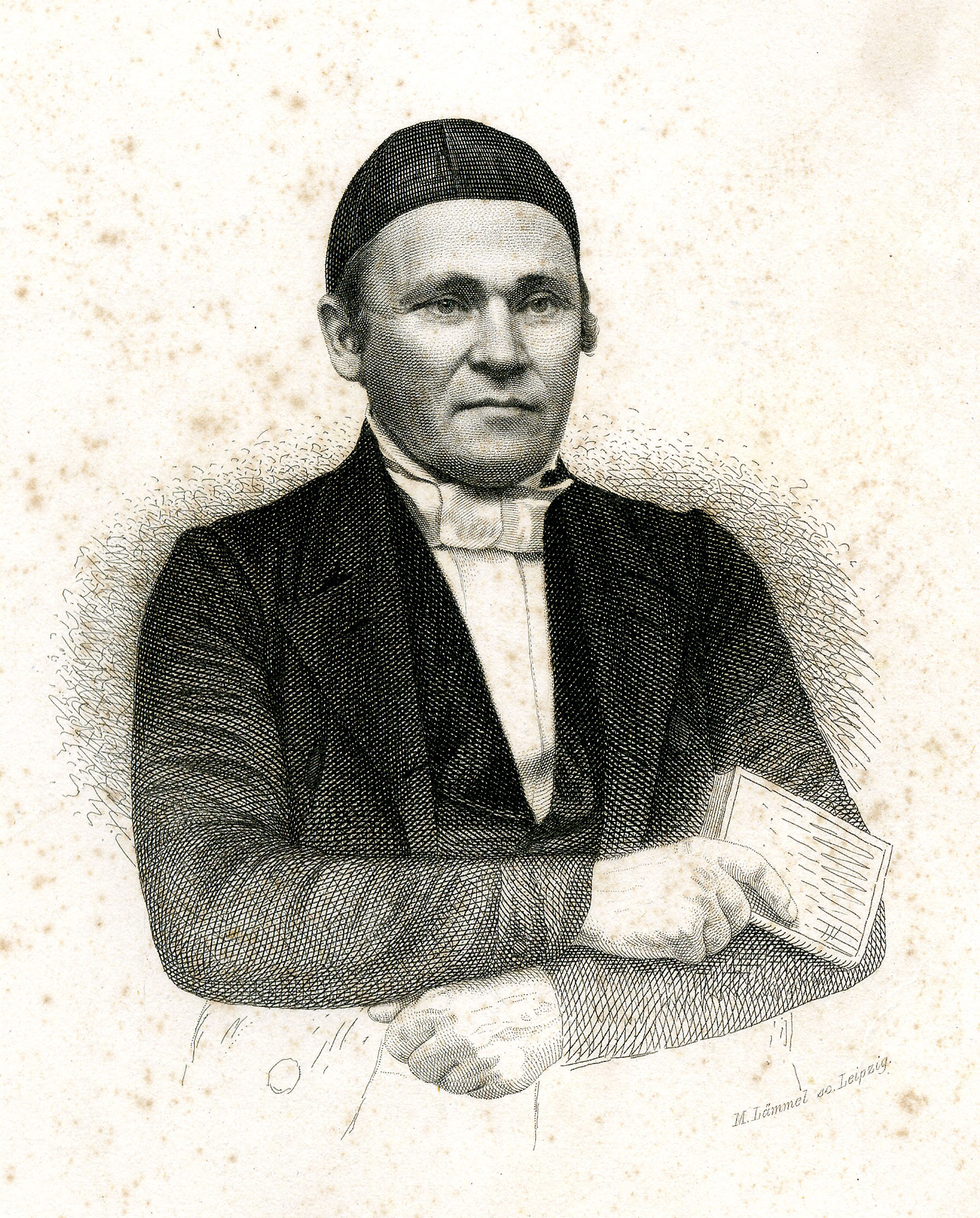

on 13 March 1844. He was joined in 1846 by Johannes Rebmann

Johannes Rebmann (January 16, 1820 – October 4, 1876), also sometimes anglicised as John Rebman, was a German missionary, linguist, and explorer credited with feats including being the first European, along with his colleague Johann Ludwig Krap ...

(1820–1876). On 12 November 1848 Rebmann started a journey into the interior. The ''Church Missionary Intelligencer'' reported that, "The ultimate object, which our Missionaries had in view, has been to reach Uniamési, that interior country where the roads to East Africa and West Africa diverge." Uniamési was said to lie about 150 to 200 hours to the west of the Chagga kingdom, which lay on the slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro

Mount Kilimanjaro () is a dormant volcano in Tanzania. It is the highest mountain in Africa and the highest free-standing mountain above sea level in the world, at above sea level and above its plateau base. It is also the highest volcano i ...

.

On 10 June 1849 Jakob Erhardt

Johann Jakob Erhardt, or John James Erhardt, (17 April 1823 – 14 August 1901) was a German missionary and explorer who worked in East Africa and India.

Although he remained on or near the coast of East Africa, he contributed to European knowl ...

(1823–1901) and John Wagner arrived at the Rabbai Mpia mission station near Mombasa

Mombasa ( ; ) is a coastal city in southeastern Kenya along the Indian Ocean. It was the first capital of British East Africa, before Nairobi was elevated to capital status in 1907. It now serves as the capital of Mombasa County. The town is ...

. Wagner died on 1 August 1849. In the spring of 1850 Erhardt and Krapf traveled by dhow

Dhow (; ) is the generic name of a number of traditional sailing vessels with one or more masts with settee or sometimes lateen sails, used in the Red Sea and Indian Ocean region. Typically sporting long thin hulls, dhows are trading vessels ...

down the East African coast from Mombasa. On the journey they met traders from Unyamwezi. Krapf recorded that caravans of three to four thousand men from Unyamwezi would arrive at the coast in December after a three-month journey, and would leave on the return journey in March or April. The Arabs of Zanzibar

Zanzibar is a Tanzanian archipelago off the coast of East Africa. It is located in the Indian Ocean, and consists of many small Island, islands and two large ones: Unguja (the main island, referred to informally as Zanzibar) and Pemba Island. ...

were hostile to Europeans reaching Unyamwezi. In 1847 they arranged for Washenzis to kill a French trader, Mr. Maison, on his way to the interior.

The missionaries were impatient to learn more about "the great central country of Uniamési, whither converge the great rivers which have their embouchures on the western and eastern coasts... from which, according to the native conception, is an outlet to the four quarters of the globe." There seemed to be "no doubt that the Natives of this central land traffic with the western as well as the eastern coast." In 1850 Krapf exclaimed that, "Had we sufficient pecuniary means at our command, and were it not our bounden duty to subordinate all secondary objects to our chief vocation, which consists in the preaching of the Gospel, the map of East Africa would soon wear another aspect."

Krapf wrote, "I have lately perused a paper making the lake Niassa and that of Uniamesi appear as one and the same volume of water... from other native authorities I know at least that the Natives clearly distinguish between the Niassa and the Uniamesi lakes. But as I have made it a rule to distrust all native reports, until they be confirmed by personal observation, I shall say nothing more on this point." Later that year the ''Church missionary intelligencer'' published an account by Krapf of a journey to Ukambani

The Kamba or Akamba (sometimes called Wakamba) people are Bantu peoples ethnic group who predominantly live in Kenya stretching from Nairobi to Tsavo and northwards to Embu, in the southern part of the former Eastern Province. This land is ...

that he had made in November and December 1849. He speculated that the Niger

Niger, officially the Republic of the Niger, is a landlocked country in West Africa. It is a unitary state Geography of Niger#Political geography, bordered by Libya to the Libya–Niger border, north-east, Chad to the Chad–Niger border, east ...

and its tributary the Tshadda ( Benue), the Congo, Nile

The Nile (also known as the Nile River or River Nile) is a major north-flowing river in northeastern Africa. It flows into the Mediterranean Sea. The Nile is the longest river in Africa. It has historically been considered the List of river sy ...

and Kilimani (Quelimane

Quelimane () is a seaport in Mozambique. It is the administrative Capital (political), capital of the Zambezia Province and the province's largest city, and stands from the mouth of the Rio dos Bons Sinais (or "River of the Good Signs"). The riv ...

– near to the mouth of the Zambezi

The Zambezi (also spelled Zambeze and Zambesi) is the fourth-longest river in Africa, the longest east-flowing river in Africa and the largest flowing into the Indian Ocean from Africa. Its drainage basin covers , slightly less than half of t ...

) would all provide access to the center of Africa.

Uniamési was thought to contain a great lake. Krapf said,

Erhardt's map

Jakob Erhardt spent six months at Tanga studying the Kisambara language, where he heard the stories of ivory traders who had visited the interior. According to Rebmann, whose account was published in Krapf's memoirs,

Erhardt was struck by the fact that various travelers who had gone inland from different points on the east coast of Africa had all come to an inland sea, and made a map based on available information, including the findings of Krapf and Rebmann.

In November 1854 while talking about the problem to Rebmann, "at one and the same moment, the problem flashed on both of us solved by the simple supposition that where geographical hypothesis had hitherto supposed an enormous mountain-land, we must now look for an enormous valley and an inland sea." On the map that he and Rebmann drew the three lakes are shown as one very large S-shaped lake.

In 1855 Erhardt was repatriated due to poor health, and took the map with him.

Rebmann wrote letters to the ''Calwer Missionary Intelligencer (Calwer Missionsblatt)'', received and published in 1855, in which he called the lake Uniamesi or Ukerewe. He said that according to accounts by traders, considered trustworthy by the missionaries, the lake extended from latitude 0.5°N to 13.5°S and from longitude 23.5°E to 36°E, and had an area of 13,600 German square miles, as compared to 7,860 German square miles for the Black Sea and 7,400 for the Caspian.

The map was first published in the ''Calwer Missionsblatt'' later in 1855, and then in the ''Church Missionary intelligencer'' in 1856.

Jakob Erhardt spent six months at Tanga studying the Kisambara language, where he heard the stories of ivory traders who had visited the interior. According to Rebmann, whose account was published in Krapf's memoirs,

Erhardt was struck by the fact that various travelers who had gone inland from different points on the east coast of Africa had all come to an inland sea, and made a map based on available information, including the findings of Krapf and Rebmann.

In November 1854 while talking about the problem to Rebmann, "at one and the same moment, the problem flashed on both of us solved by the simple supposition that where geographical hypothesis had hitherto supposed an enormous mountain-land, we must now look for an enormous valley and an inland sea." On the map that he and Rebmann drew the three lakes are shown as one very large S-shaped lake.

In 1855 Erhardt was repatriated due to poor health, and took the map with him.

Rebmann wrote letters to the ''Calwer Missionary Intelligencer (Calwer Missionsblatt)'', received and published in 1855, in which he called the lake Uniamesi or Ukerewe. He said that according to accounts by traders, considered trustworthy by the missionaries, the lake extended from latitude 0.5°N to 13.5°S and from longitude 23.5°E to 36°E, and had an area of 13,600 German square miles, as compared to 7,860 German square miles for the Black Sea and 7,400 for the Caspian.

The map was first published in the ''Calwer Missionsblatt'' later in 1855, and then in the ''Church Missionary intelligencer'' in 1856. August Heinrich Petermann

Augustus Heinrich Petermann (18 April 182225 September 1878) was a German cartographer.

Early years

Petermann was born in Bleicherode, Germany. When he was 14 years old, he started grammar school in the nearby town of Nordhausen. Despite fa ...

published the map in his ''Mittheilungen'', but warned that the missionaries may not have accounted sufficiently for exaggeration by their informants. He provided a supplementary sketch showing the lake extending from 7°S to 12°S and 22.5°E to 30.5°E, one third of Rebmann's estimated size.

The map was reproduced with commentary in other publications.Ferdinand de Lesseps

Ferdinand Marie, Comte de Lesseps (; 19 November 1805 – 7 December 1894) was a French Orientalist diplomat and owner of Main Idea of the Suez Canal, which in 1869 joined the Mediterranean and Red Seas, substantially reducing sailing distan ...

saw a pen-and-ink version of the map made by "Mr. Rehman of Moubar, on the Zanguebar coast." In a letter of April 1857 to the ''Académie des Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences (, ) is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French Scientific method, scientific research. It was at the forefron ...

'' of Paris he commented that the inland sea would be larger than the Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal sea, marginal Mediterranean sea (oceanography), mediterranean sea lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bound ...

. He said, "The existence of this sea was certified to me during my stay at Khartoum

Khartoum or Khartum is the capital city of Sudan as well as Khartoum State. With an estimated population of 7.1 million people, Greater Khartoum is the largest urban area in Sudan.

Khartoum is located at the confluence of the White Nile – flo ...

by a pilgrim from Mecca, who inhabits Central Africa, and who gave Mahmoud Pasha, one of the Viceroy's ministers, particulars corresponding to Mr. Rehman's map. This pilgrim added that he had seen larger vessels on the ''Uniamesi'' than that in which he had sailed down the Red Sea."

The reports of snow on mounts Kilimanjaro

Mount Kilimanjaro () is a dormant volcano in Tanzania. It is the highest mountain in Africa and the highest free-standing mountain above sea level in the world, at above sea level and above its plateau base. It is also the highest volcano i ...

and Kenya

Kenya, officially the Republic of Kenya, is a country located in East Africa. With an estimated population of more than 52.4 million as of mid-2024, Kenya is the 27th-most-populous country in the world and the 7th most populous in Africa. ...

, near to the equator, caused considerable controversy. Sir Francis Galton

Sir Francis Galton (; 16 February 1822 – 17 January 1911) was an English polymath and the originator of eugenics during the Victorian era; his ideas later became the basis of behavioural genetics.

Galton produced over 340 papers and b ...

, who had won the Royal Geographical Society

The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers), often shortened to RGS, is a learned society and professional body for geography based in the United Kingdom. Founded in 1830 for the advancement of geographical scien ...

's gold medal in 1853 for his southwest African explorations, had Erhardt's map published in the society's ''Proceedings''. Galton was pressed to travel to Africa to confirm the report about Mount Kilimanjaro. He declined on the basis that he had not yet fully recovered his health from his previous expedition. Instead, the Royal Geographical Society persuaded the British government to provide £1,000 for an expedition by Richard Francis Burton

Captain (British Army and Royal Marines), Captain Sir Richard Francis Burton, Order of St Michael and St George, KCMG, Royal Geographical Society#Fellowship, FRGS, (19 March 1821 – 20 October 1890) was a British explorer, army officer, orien ...

and John Hanning Speke

Captain John Hanning Speke (4 May 1827 – 15 September 1864) was an English explorer and army officer who made three exploratory expeditions to Africa. He is most associated with the search for the source of the Nile and was the first Eu ...

to investigate the great lake, or lakes, and determine if they were the source of the Nile. The map came to be known as the "slug map" from the shape of the Uniamesi or Niassa inland sea. Burton called it the Mombas Mission Map.

Exploration

Burton and Speke reached Zanzibar on 20 December 1857, visited Rebmann at his Kisuludini mission station, and paid a visit to Fuga, capital of the Usambare kingdom. Burton met king

Burton and Speke reached Zanzibar on 20 December 1857, visited Rebmann at his Kisuludini mission station, and paid a visit to Fuga, capital of the Usambare kingdom. Burton met king Kimweri ye Nyumbai

Kimweri ya Nyumbai or Shekulwavu Kimweri ya Nyumabi (c. 1790s – 1862), also known as (Simbe Mwene), (''Simbe Mwene Shekulwavu Kimweri ya Nyumbai'' in Shambala language, Shambaa), (''Mfalme Kimweri'', in Swahili language, Swahili) was the ...

, once a powerful warrior who had controlled the trade routes to the interior but now extremely old. They left for the interior on 26 June 1858. After travelling through mountainous country they reached the inner plateau of Uniamesi. At the Arab trading post of Kazeh (now Tabora

Tabora is the capital of Tanzania's Tabora Region and is classified as a municipality by the Tanzanian government. It is also the administrative seat of Tabora Urban District. According to the 2012 census, the district had a population of 226, ...

) they recorded an elevation of .

At Kazeh Burton and Speke found a mixed population of Nyamwezi, Tutsi and Arabs engaged in cattle farming and cultivation of foods such as rice, cassava, pawpaw and citrus. Burton called Unyamwezi the garden of inter-tropical Africa.

The land sloped down from there to Lake Takanyika ic or Uniamesi, which they reached on 3 March 1849 and where they recorded an elevation of .

Burton and Speke found that the lake extended about north from Ujiji

Ujiji is the oldest town in western Tanzania and is located in Kigoma-Ujiji District of Kigoma Region. Originally a Swahili settlement and then an Arab slave trading post by the mid-nineteenth century nominally under the Sultanate of Zanziba ...

, where it was closed by a crescent-shaped mountain range. They were told by the local people that the lake reached down to latitude 8° south. Later David Livingstone

David Livingstone (; 19 March 1813 – 1 May 1873) was a Scottish physician, Congregationalist, pioneer Christian missionary with the London Missionary Society, and an explorer in Africa. Livingstone was married to Mary Moffat Livings ...

was given consistent information by an Arab trader who had skirted the south of the lake, and a Swahili traveler also confirmed that the "Taganyika" was not connected to the Niassa to the south.

Burton and Speke returned to Kazeh, where Burton was forced to rest while Speke traveled north to explore Lake Victoria

Lake Victoria is one of the African Great Lakes. With a surface area of approximately , Lake Victoria is Africa's largest lake by area, the world's largest tropics, tropical lake, and the world's second-largest fresh water lake by surface are ...

(also called Lake Ukerewe), reaching it on 3 August 1849. Speke recorded an elevation of and was told that a river left the north of the lake and flowed into the Nile.

There was continued controversy about the Great Lakes and the rivers that fed and drained them. Speke made a long journey with James Augustus Grant

Lieutenant-Colonel James Augustus Grant (11 April 1827 – 11 February 1892) was a Scottish explorer of eastern equatorial Africa. He made contributions to the journals of various learned societies, the most notable being the "Botany of the ...

between October 1860 and February 1863, traveling from the coast opposite Zanzibar via Tabora and Uganda to Khartoum. However, the question of whether the Nile issued from Lake Victoria was left uncertain.

In 1866–73 David Livingstone

David Livingstone (; 19 March 1813 – 1 May 1873) was a Scottish physician, Congregationalist, pioneer Christian missionary with the London Missionary Society, and an explorer in Africa. Livingstone was married to Mary Moffat Livings ...

left the coast at Pemba, followed the Ruvuma River

Ruvuma River, formerly also known as the Rovuma River, is a river in the African Great Lakes region. During the greater part of its course, it forms the border between Tanzania and Mozambique. The river is long, with a drainage basin of ~ in si ...

inland and walked to the southern end of Lake Nyasa, which he rounded to the west. He then traveled north to Lake Tanganyika. After lengthy explorations of the country southwest of Lake Tanganyika, with his health broken Livingstone reached Ujiji on the east of Lake Tanganyika, where he had his famous meeting with Henry Morton Stanley

Sir Henry Morton Stanley (born John Rowlands; 28 January 1841 – 10 May 1904) was a Welsh-American explorer, journalist, soldier, colonial administrator, author, and politician famous for his exploration of Central Africa and search for missi ...

on 10 November 1871.

Verney Lovett Cameron

Verney Lovett Cameron (1 July 184424 March 1894) was an English traveller in Central Africa and the first European to cross (1875) equatorial Africa from sea to sea.

Biography

He was born at Radipole, near Weymouth, Dorset, son of Rev Jonat ...

was sent in 1873 to assist David Livingstone. Shortly after he left Zanzibar he learned that Livingstone had died, but continued to Ujiji. He circumnavigated Lake Tanganyika and found that it had its outlet to the west, feeding into a tributary of the Congo River. Cameron went on to the Atlantic, becoming one of the first Europeans to make an east-west crossing of Equatorial Africa. It was not until Stanley circumnavigated Lake Victoria in 1874–1875 that it was confirmed that the lake was the source of the White Nile. With Stanley's return to Zanzibar in 1877 the last of the main questions surrounding the Great Lakes drainage had been settled. Krapf had conjectured there was one great lake feeding the Congo, Zambezi, Nile and Benue. There had turned out to be three great lakes, feeding the Congo, Zambezi and Nile.

References

Notes Citations Sources * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Uniamesi Africa in mythology African Great Lakes International lakes of Africa Mythological places