Laborist on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The labour movement is the collective organisation of working people to further their shared political and economic interests. It consists of the trade union or labour union movement, as well as political parties of labour. It can be considered an instance of

With the advent of the French Revolution, radicalism became even more prominent in English politics with the publication of Thomas Paine's The Rights of Man in 1791 and the foundation of the working-class focused

With the advent of the French Revolution, radicalism became even more prominent in English politics with the publication of Thomas Paine's The Rights of Man in 1791 and the foundation of the working-class focused

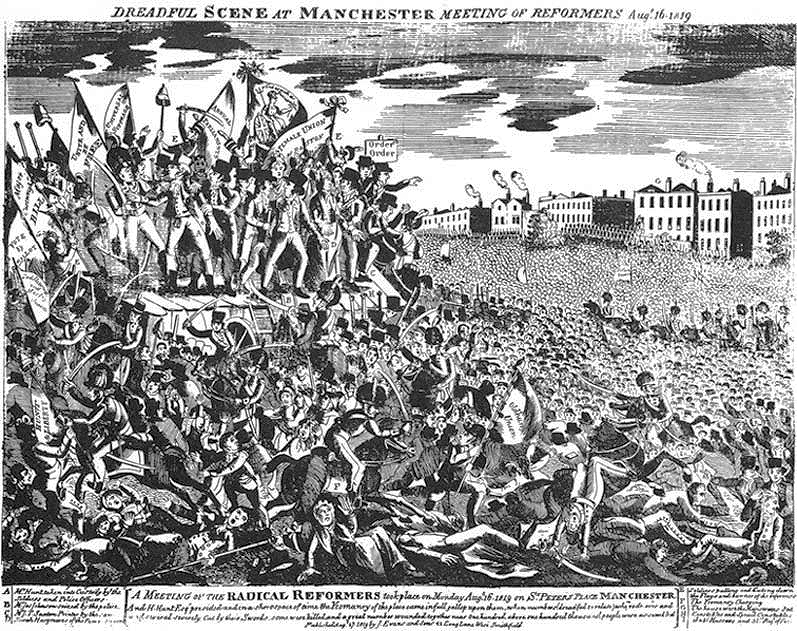

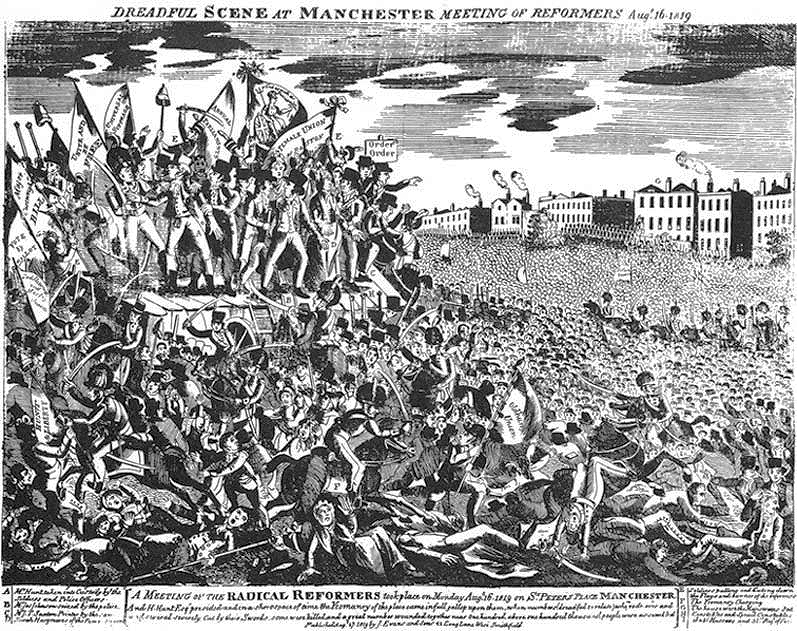

In spite of government suppression, the labour movement in the United Kingdom continued, and 1818 marked a new round of strikes as well as the first attempt at establishing a single national union that encompassed all trades, led by John Gast and named the "Philanthropic Hercules". Although this enterprise quickly folded, pro-labour political agitation and demonstrations increased in popularity throughout industrial United Kingdom culminating in 1819 with an incident in St. Peter's field, Manchester, known as the

In spite of government suppression, the labour movement in the United Kingdom continued, and 1818 marked a new round of strikes as well as the first attempt at establishing a single national union that encompassed all trades, led by John Gast and named the "Philanthropic Hercules". Although this enterprise quickly folded, pro-labour political agitation and demonstrations increased in popularity throughout industrial United Kingdom culminating in 1819 with an incident in St. Peter's field, Manchester, known as the

online

. *Robert N. Stern, Daniel B. Cornfield, ''The U.S. labor movement:References and Resources'', G.K. Hall & Co 1996 *John Hinshaw and Paul LeBlanc (ed.), ''U.S. labor in the twentieth century: studies in working-class struggles and insurgency'', Amherst, NY: Humanity Books, 2000 * *Philip Yale Nicholson, ''Labor's story in the United States'', Philadelphia, Pa.: Temple Univ. Press 2004 (Series 'Labor in Crisis'), * Beverly Silver: ''Forces of Labor. Worker's Movements and Globalization since 1870'', Cambridge University Press, 2003, *St. James Press Encyclopedia of Labor History Worldwide, St. James Press 2003 *Lenny Flank (ed), ''IWW: A Documentary History'', Red and Black Publishers, St Petersburg, Florida, 2007. * Tom Zaniello: ''Working Stiffs, Union Maids, Reds, and Riffraff: An Expanded Guide to Films about Labor'' (ILR Press books), Cornell University Press, revised and expanded edition 2003,

''Neither Washington Nor Stowe: Common Sense For The Working Vermonter''

The Green Mountain Anarchist Collective, Catamount Tavern Press, 2004. *

The Canadian Museum of Civilization – Canadian Labour History, 1850–1999LabourStart: Trade union web portalLaborNet: Global online communication for a democratic, independent labour movementCEC: A Labour Resource Centre in India

* {{Authority control

class conflict

In political science, the term class conflict, class struggle, or class war refers to the economic antagonism and political tension that exist among social classes because of clashing interests, competition for limited resources, and inequali ...

.

* In trade unions

A trade union (British English) or labor union (American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers whose purpose is to maintain or improve the conditions of their employment, such as attaining better wages ...

, workers campaign for higher wages, better working conditions and fair treatment from their employers, and through the implementation of labour laws, from their governments. They do this through collective bargaining

Collective bargaining is a process of negotiation between employers and a group of employees aimed at agreements to regulate working salaries, working conditions, benefits, and other aspects of workers' compensation and labour rights, rights for ...

, sectoral bargaining, and when needed, strike action

Strike action, also called labor strike, labour strike in British English, or simply strike, is a work stoppage caused by the mass refusal of employees to Working class, work. A strike usually takes place in response to employee grievances. Str ...

. In some countries, co-determination gives representatives of workers seats on the board of directors of their employers.

* Political parties

A political party is an organization that coordinates candidates to compete in a particular area's elections. It is common for the members of a party to hold similar ideas about politics, and parties may promote specific ideological or p ...

representing the interests of workers campaign for labour rights

Labor rights or workers' rights are both legal rights and human rights relating to labor relations between workers and employers. These rights are codified in national and international labor and employment law. In general, the ...

, social security

Welfare spending is a type of government support intended to ensure that members of a society can meet basic human needs such as food and shelter. Social security may either be synonymous with welfare, or refer specifically to social insurance ...

and the welfare state

A welfare state is a form of government in which the State (polity), state (or a well-established network of social institutions) protects and promotes the economic and social well-being of its citizens, based upon the principles of equal oppor ...

. They are usually called a labour party (in English-speaking countries), a social democratic party

The name Social Democratic Party or Social Democrats has been used by many political parties in various countries around the world. Such parties are most commonly aligned to social democracy as their political ideology.

Active parties

Form ...

(in Germanic and Slavic countries), a socialist party

Socialist Party is the name of many different political parties around the world. All of these parties claim to uphold some form of socialism, though they may have very different interpretations of what "socialism" means. Statistically, most of th ...

(in Romance countries), or sometimes a workers' party

Workers' Party is a name used by several political parties throughout the world. The name has been used by both organisations on the left and right of the political spectrum. It is currently used by followers of Marxism, Marxism–Leninism, Maoism ...

.

* Though historically less prominent, the cooperative movement

The history of the cooperative movement concerns the origins and history of cooperatives across the world. Although cooperative arrangements, such as mutual insurance, and principles of cooperation existed long before, the cooperative movement bega ...

campaigns to replace capitalist ownership of the economy with worker cooperatives

A worker cooperative is a cooperative owned and self-managed by its workers. This control may mean a firm where every worker-owner participates in decision-making in a democratic fashion, or it may refer to one in which management is elected by ...

, consumer cooperatives, and other types of cooperative ownership

A cooperative (also known as co-operative, coöperative, co-op, or coop) is "an autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly owned and democr ...

. This is related to the concept of economic democracy

Economic democracy (sometimes called a democratic economy) is a socioeconomic philosophy that proposes to shift ownership and decision-making power from corporate shareholders and corporate managers (such as a board of directors) to a larger ...

.

The labour movement developed as a response to capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

and the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution, sometimes divided into the First Industrial Revolution and Second Industrial Revolution, was a transitional period of the global economy toward more widespread, efficient and stable manufacturing processes, succee ...

of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, at about the same time as socialism

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

. The early goals of the movement were the right to unionise, the right to vote

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise is the right to vote in representative democracy, public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in ...

, democracy

Democracy (from , ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which political power is vested in the people or the population of a state. Under a minimalist definition of democracy, rulers are elected through competitiv ...

, safe working conditions and the 40-hour week. As these were achieved in many of the advanced economies of western Europe and north America in the early decades of the 20th century, the labour movement expanded to issues of welfare and social insurance, wealth distribution

The distribution of wealth is a comparison of the wealth of various members or groups in a society. It shows one aspect of economic inequality or economic heterogeneity.

The distribution of wealth differs from the income distribution in that ...

and income distribution

In economics, income distribution covers how a country's total GDP is distributed amongst its population. Economic theory and economic policy have long seen income and its distribution as a central concern. Unequal distribution of income causes e ...

, public services

A public service or service of general (economic) interest is any service (economics), service intended to address the needs of aggregate members of a community, whether provided directly by a public sector agency, via public financing availab ...

like health care

Health care, or healthcare, is the improvement or maintenance of health via the preventive healthcare, prevention, diagnosis, therapy, treatment, wikt:amelioration, amelioration or cure of disease, illness, injury, and other disability, physic ...

and education, social housing

Public housing, also known as social housing, refers to Subsidized housing, subsidized or affordable housing provided in buildings that are usually owned and managed by local government, central government, nonprofit organizations or a ...

and common ownership

Common ownership refers to holding the assets of an organization, enterprise, or community indivisibly rather than in the names of the individual members or groups of members as common property. Forms of common ownership exist in every economi ...

.

History

Origins in the United Kingdom

The labour movement has its origins in Europe during theIndustrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution, sometimes divided into the First Industrial Revolution and Second Industrial Revolution, was a transitional period of the global economy toward more widespread, efficient and stable manufacturing processes, succee ...

of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, when agricultural

Agriculture encompasses crop and livestock production, aquaculture, and forestry for food and non-food products. Agriculture was a key factor in the rise of sedentary human civilization, whereby farming of domesticated species created f ...

and cottage industry

The putting-out system is a means of subcontracting work, like a tailor. Historically, it was also known as the workshop system and the domestic system. In putting-out, work is contracted by a central agent to subcontractors who complete the p ...

jobs disappeared and were replaced as mechanization

Mechanization (or mechanisation) is the process of changing from working largely or exclusively by hand or with animals to doing that work with machinery. In an early engineering text, a machine is defined as follows:

In every fields, mechan ...

and industrialization

Industrialisation (British English, UK) American and British English spelling differences, or industrialization (American English, US) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an i ...

moved employment to more industrial areas like factory towns causing an influx of low-skilled labour and a concomitant decline in real wages and living standards for workers in urban areas. Prior to the industrial revolution, economies in Europe were dominated by the guild system which had originated in the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

. The guilds were expected to protect the interests of the owners, labourers, and consumers through regulation of wages, prices, and standard business practices. However, as the increasingly unequal and oligarchic guild system deteriorated in the 16th and 17th centuries, spontaneous formations of journeymen

A journeyman is a worker, skilled in a given building trade or craft, who has successfully completed an official apprenticeship qualification. Journeymen are considered competent and authorized to work in that field as a fully qualified employee ...

within the guilds would occasionally act together to demand better wage rates and conditions, and these ad hoc groupings can be considered the forerunners of the modern labour movement. These formations were succeeded by trade unions forming in the United Kingdom in the 18th century. Nevertheless, without the continuous technological and international trade pressures during the Industrial Revolution, these trade unions remained sporadic and localised only to certain regions and professions, and there was not yet enough impetus for the formation of a widespread and comprehensive labour movement. Therefore, the labour movement is usually marked as beginning concurrently with the Industrial Revolution in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

, roughly around 1760-1830.

16th and 17th centuries

InEngland

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

the guild system was usurped in its regulation of wages by parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

in the 16th century with the passage of the Elizabethan Era

The Elizabethan era is the epoch in the Tudor period of the history of England during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I (1558–1603). Historians often depict it as the golden age in English history. The Roman symbol of Britannia (a female ...

apprentice laws such as the Statute of Artificers 1562

The Statute of Artificers 1563 or the Artificers and Apprentices Act 1563 (5 Eliz. 1. c. 4), also known as the Statute of Labourers 1562, was an Act of Parliament (United Kingdom), act of the Parliament of England, under Queen Elizabeth I, whic ...

which placed the power to regulate wages and employment in the hands of local officials in each parish. Parliament had been responding to petitions made by English weavers

Weaver or Weavers may refer to:

Activities

* A person who engages in weaving fabric

Animals

* Various birds of the family Ploceidae

* Crevice weaver spider family

* Orb-weaver spider family

* Weever (or weever-fish)

Arts and entertainment

...

in 1555 who asserted that the owners were "giving much less wages and hire for weaving of clothes than they did in the past." This legislation was intended to ensure just compensation for workers throughout the country so they could maintain a "competent livelihood". This doctrine of parliamentary involvement remained in place until about 1700 at which point the practice of wage regulation began to decline, and in 1757 Parliament outright rescinded the Weavers Act 1756, abandoning its power of wage regulation and signaling its newfound dedication to laissez-faire

''Laissez-faire'' ( , from , ) is a type of economic system in which transactions between private groups of people are free from any form of economic interventionism (such as subsidies or regulations). As a system of thought, ''laissez-faire'' ...

economics.

The Elizabethan Apprentice Laws lasted in England until the early 19th century, but were becoming increasingly dead letter

Dead letter mail or undeliverable mail is mail that cannot be delivered to the addressee or returned to the sender. This is usually due to lack of compliance with postal regulations, an incomplete address and return address, or the inability to ...

by the mid 18th century. Consequently, from 1760 on, real wages began to fall and food prices began to rise giving increased motivation for political and social agitation. As the guild system became increasingly obsolete and parliament abolished the old medieval labour protections, forswearing responsibility for maintaining living standards, the workers began to form the earliest versions of trade unions. The workers on the lowest rungs found it necessary to organise in new ways to protect their wages and other interests such as living standards and working conditions.

18th century

There is no record of enduring trade unions existing prior to the 18th century. Beginning from 1700 onward there are records of complaints in the United Kingdom, which increase through the century, that show instances of labourers "combining" together to raise wages had become a phenomenon in various regions and professions. These early trade unions were fairly small and limited in scope and were separated from unions in other geographical areas or unions in other professions. The unions would strike, collectively bargain with employers, and, if that did not suffice, petition parliament for the enforcement of the Elizabethan statues. The first groups in England to practice early trade unionism were theWest of England

The West of England is an area of South West England around the River Avon. The area has a local government combined authority that consists of the unitary authorities of Bristol, South Gloucestershire, and Bath and North East Somerset. The comb ...

wool workers and the framework knitters in the Midlands

The Midlands is the central region of England, to the south of Northern England, to the north of southern England, to the east of Wales, and to the west of the North Sea. The Midlands comprises the ceremonial counties of Derbyshire, Herefor ...

. As early as 1718 a royal proclamation was given in opposition to the formation of any unsanctioned bodies of journeymen attempting to affect wages and employment. Despite the presumption that unionising was illegal, it continued throughout the 18th century.

Strikes and riots by miners and framework knitters occurred throughout England over the course of the 18th century, often resorting to machine breaking and sabotage. In 1751 wool-combers in Leicestershire

Leicestershire ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the East Midlands of England. It is bordered by Derbyshire, Nottinghamshire and Lincolnshire to the north, Rutland to the east, Northamptonshire to the south-east, Warw ...

formed a union which both disallowed hiring non-members and provided aid for out-of-work members. In the Spitalfields

Spitalfields () is an area in London, England and is located in the London Borough of Tower Hamlets. It is in East London and situated in the East End of London, East End. Spitalfields is formed around Commercial Street, London, Commercial Stre ...

area of London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

, weavers went on strike and rioted in 1765, 1769, and 1773 until parliament relented and allowed justices in the area to fix wage rates. Artisans and workers would also create small craft clubs or trade clubs in each town or locality and these groups such as the hatters

Hat-making or millinery is the design, manufacture and sale of hats and other headwear. A person engaged in this trade is called a milliner or hatter.

Historically, milliners made and sold a range of accessories for clothing and hairstyles. ...

in London, shipwrights

Shipbuilding is the construction of ships and other floating vessels. In modern times, it normally takes place in a specialized facility known as a shipyard. Shipbuilders, also called shipwrights, follow a specialized occupation that traces i ...

in Liverpool

Liverpool is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. It is situated on the eastern side of the River Mersey, Mersey Estuary, near the Irish Sea, north-west of London. With a population ...

, or cutlers in Sheffield

Sheffield is a city in South Yorkshire, England, situated south of Leeds and east of Manchester. The city is the administrative centre of the City of Sheffield. It is historically part of the West Riding of Yorkshire and some of its so ...

could use their clubs to unionize. Workers could also use the ubiquitous friendly societies, which had increasingly cropped up British society since 1700, as cover for union activities.

In politics, the MP John Wilkes

John Wilkes (17 October 1725 – 26 December 1797) was an English Radicalism (historical), radical journalist and politician, as well as a magistrate, essayist and soldier. He was first elected a Member of Parliament in 1757. In the Middlese ...

used mass appeal to workers through public meetings, pamphleteering

A pamphleteer is a historical term used to describe someone who creates or distributes pamphlets, unbound (therefore inexpensive) booklets intended for wide circulation.

Context

Pamphlets were used to broadcast the writer's opinions: to articu ...

, and the popular press, in order to gain their support as he advocated for an increase in the voting franchise, popular rights, and an end to corruption. When he was imprisoned for criticizing King George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and King of Ireland, Ireland from 25 October 1760 until his death in 1820. The Acts of Union 1800 unified Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain and ...

, his followers protested and were fired upon by the government at the Massacre of St George's Fields

The Massacre of St George's Fields occurred on 10 May 1768 when government soldiers opened fire on demonstrators that had gathered at St George's Fields, Southwark, in south London. The protest was against the imprisonment of the radical Membe ...

in 1768, which resulted in a round of strikes and riots throughout England. Other notable radicals at the time included John Jebb, Major Cartwright, and John Horne

John Horne PRSE FRS FRSE FEGS LLD (1 January 1848 – 30 May 1928) was a Scottish geologist. He served as president of the Royal Society of Edinburgh from 1915 to 1919.

Life

Horne was born on 1 January 1848, in Campsie, Stirlingshire, the ...

.

With the advent of the French Revolution, radicalism became even more prominent in English politics with the publication of Thomas Paine's The Rights of Man in 1791 and the foundation of the working-class focused

With the advent of the French Revolution, radicalism became even more prominent in English politics with the publication of Thomas Paine's The Rights of Man in 1791 and the foundation of the working-class focused London Corresponding Society

The London Corresponding Society (LCS) was a federation of local reading and debating clubs that in the decade following the French Revolution agitated for the democratic reform of the British Parliament. In contrast to other reform associatio ...

in 1792. Membership in the society increased rapidly and by the end of the year it may have had as many as three thousand chapters in the United Kingdom.

Fearful of this new English Jacobinism

A Jacobin (; ) was a member of the Jacobin Club, a revolutionary political movement that was the most famous political club during the French Revolution (1789–1799). The club got its name from meeting at the Dominican rue Saint-Honoré ...

, the government responded with wide-scale political repression spearheaded by prime minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

Pitt the Younger

William Pitt (28 May 1759 – 23 January 1806) was a British statesman who served as the last prime minister of Great Britain from 1783 until the Acts of Union 1800, and then first prime minister of the United Kingdom from January 1801. He left o ...

. Paine was forced to flee the country after his work was deemed to be seditious

Sedition is overt conduct, such as speech or organization, that tends toward rebellion against the established order. Sedition often includes subversion of a constitution and incitement of discontent toward, or insurrection against, establis ...

, booksellers selling Paine's or other radical works were arrested, the Scottish reformers Thomas Muir, Rev. Thomas Fyshe Palmer, Joseph Gerrald, and Maurice Margarot were transported

''Transported'' is an Australian convict melodrama film directed by W. J. Lincoln.

It is considered a lost film.

Plot

In England, Jessie Grey is about to marry Leonard Lincoln but the evil Harold Hawk tries to force her to marry him and she ...

, and, in 1794, the leadership of the L.C.S was arrested and tried. Speech and public gatherings were tightly restricted by the Two Acts of 1795 which made certain words acts of treason, limited public gatherings to fifty people or fewer, and enforced licensing for anyone who wanted to speak in a public debate or lecture hall. In 1797 the L.C.S was outlawed by parliament, temporarily crushing the British labour movement. Additionally, forming unions or combinations was made illegal under legislation such as the 1799 Combination Act. Trade unionism in the United Kingdom illegally continued into the 19th century despite increasing hardship. Determined workers refused to allow the law to entirely eradicate trade unionism. Some employers chose to forgo legal prosecution and instead bargained and cooperated with workers' demands.19th century

The Scottish weavers ofGlasgow

Glasgow is the Cities of Scotland, most populous city in Scotland, located on the banks of the River Clyde in Strathclyde, west central Scotland. It is the List of cities in the United Kingdom, third-most-populous city in the United Kingdom ...

went on strike around 1805, demanding enforcement of the old Elizabethan laws empowering magistrates to fix wages to meet the costs of living; however, after three weeks the strike was ended when the police arrested the strike leaders. A renewed stimulus to organised labour in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

can be traced back to the 1808 failure of the 'Minimum Wage Bill' in parliament which supporters had seen as a needed countermeasure for the endemic poverty among the working classes of industrial United Kingdom. After the failure of the Minimum Wage Bill displayed the government's commitment to laissez-faire policy, labourers expressed their discontent in the form of the first large scale strikes in the new factory districts. Agitation did not end until it was agreed that weavers would receive a 20% increase in wages. In 1813 and 1814 Parliament would repeal the last of the apprentice laws which had been intended to protect wage rates and employment, but which had also fallen into serious disuse many decades before.

The United Kingdom saw an increasing number of large-scale strikes, mainly in the north. In 1811 in Nottinghamshire

Nottinghamshire (; abbreviated ''Notts.'') is a ceremonial county in the East Midlands of England. The county is bordered by South Yorkshire to the north-west, Lincolnshire to the east, Leicestershire to the south, and Derbyshire to the west. Th ...

, a new movement known as the Luddite

The Luddites were members of a 19th-century movement of English textile workers who opposed the use of certain types of automated machinery due to concerns relating to worker pay and output quality. They often destroyed the machines in organ ...

, or machine-breaker, movement, began. In response to declining living standards, workers all over the Midlands

The Midlands is the central region of England, to the south of Northern England, to the north of southern England, to the east of Wales, and to the west of the North Sea. The Midlands comprises the ceremonial counties of Derbyshire, Herefor ...

started to sabotage and destroy the machinery used in textile production. As the industry was still decentralized at the time and the movement was secretive, none of the leadership was ever caught and employers in the Midlands textile industry were forced to raise wages.

In 1812 the first radical, socialist, pro-labour society, the 'Society of Spencean Philanthropists', named after the radical social agitator Thomas Spence, was formed. Spence, a pamphleteer in London since 1776, believed in the socialized distribution of land and changing England into a federalized government based on democratically elected parish communes. The society was small and had only a limited presence in English politics. Other leaders such Henry Hunt, William Cobbet, and Lord Cochrane, known as Radicals

Radical (from Latin: ', root) may refer to:

Politics and ideology Politics

*Classical radicalism, the Radical Movement that began in late 18th century Britain and spread to continental Europe and Latin America in the 19th century

*Radical politics ...

, rose to the head of the labour movement demanding the lowering of taxes, the abolition of pensions and sinecures, and an end to payments of the war debt. This radicalism increased in the aftermath of the end of the Napoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

, as a general economic downturn in 1815 led to a revival in pro-labour politics. During this time, half of each worker's wages was taxed away, unemployment greatly increased, and food prices would not drop from their war time highs.

After the passage of the Corn Laws

The Corn Laws were tariffs and other trade restrictions on imported food and corn enforced in the United Kingdom between 1815 and 1846. The word ''corn'' in British English denotes all cereal grains, including wheat, oats and barley. The la ...

there was mass rioting throughout United Kingdom. Many working-class papers started being published and received by a wide audience, including Cobbet's "'' Weekly Political Register'', Thomas Wooler's '' The Black Dwarf'', and William Hone

William Hone (3 June 1780 – 8 November 1842) was an English writer, satirist and bookseller. His victorious court battle against government censorship in 1817 marked a turning point in the fight for British press freedom.

Biography

Hon ...

's ''Reformists's Register''. In addition, new political clubs focused on reform, called Hampden Clubs, were formed after a model suggested by Major Cartwright. During a speech by Henry Hunt, a group of Spenceans initiated the Spa Fields riots. This outbreak of lawlessness led to a government crackdown on agitation in 1817 known as the Gagging Acts

The Gagging Acts was the common name for two acts of Parliament passed in 1817 by Conservative Prime Minister Lord Liverpool. They were also known as the Grenville and Pitt Bills. The specific acts themselves were the Treason Act 1817 and the Se ...

, which included the suppression of the Spencean society, a suspension of habeas corpus

''Habeas corpus'' (; from Medieval Latin, ) is a legal procedure invoking the jurisdiction of a court to review the unlawful detention or imprisonment of an individual, and request the individual's custodian (usually a prison official) to ...

, and an extension of power to magistrates which gave them the ability to ban public gatherings. In protest of the Gagging Acts, as well as the poor working conditions in the textile industry, workers in Manchester attempted to march on London to deliver petitions in a demonstration known as the Blanketeers

The Blanketeers or Blanket March was a demonstration organised in Manchester in March 1817. The intention was for the participants, who were mainly Lancashire weavers, to march to London and petition the Prince Regent over the desperate state o ...

march, which ultimately failed.

From this point onward the British government also began using hired spies and agent provocateur

An is a person who actively entices another person to commit a crime that would not otherwise have been committed and then reports the person to the authorities. They may target individuals or groups.

In jurisdictions in which conspiracy is a ...

s to disrupt the labour movement. The most infamous early case of government anti-labour espionage was that of Oliver the Spy who, in 1817, incited and encouraged the Pentrich Rising

The Pentrich Rising was an armed uprising around the village of Pentrich, Derbyshire, England, on the night of 9–10 June 1817. While much of the planning took place in Pentrich, two of the three ringleaders were from South Wingfield and the ot ...

, which led to the leadership being indicted on treason charges and executed.

In spite of government suppression, the labour movement in the United Kingdom continued, and 1818 marked a new round of strikes as well as the first attempt at establishing a single national union that encompassed all trades, led by John Gast and named the "Philanthropic Hercules". Although this enterprise quickly folded, pro-labour political agitation and demonstrations increased in popularity throughout industrial United Kingdom culminating in 1819 with an incident in St. Peter's field, Manchester, known as the

In spite of government suppression, the labour movement in the United Kingdom continued, and 1818 marked a new round of strikes as well as the first attempt at establishing a single national union that encompassed all trades, led by John Gast and named the "Philanthropic Hercules". Although this enterprise quickly folded, pro-labour political agitation and demonstrations increased in popularity throughout industrial United Kingdom culminating in 1819 with an incident in St. Peter's field, Manchester, known as the Peterloo Massacre

The Peterloo Massacre took place at St Peter's Field, Manchester, Lancashire, England, on Monday 16 August 1819. Eighteen people died and 400–700 were injured when the cavalry of the Yeomen charged into a crowd of around 60,000 people who ...

. The British government responded with another round of draconian measures aimed at putting down the labour movement, known as the Six Acts

Following the Peterloo Massacre on 16 August 1819, the government of the United Kingdom under Lord Liverpool acted to prevent any future disturbances by the introduction of new legislation, the so-called Six Acts aimed at suppressing any meetings ...

.

In 1819 the social reformer Francis Place

Francis Place (3 November 1771, London – 1 January 1854, London) was an English social reformer described as "a ubiquitous figure in the machinery of radical London."

Background and early life

He was an illegitimate son of Simon Place and M ...

initiated a reform movement aimed at lobbying parliament into abolishing the anti-union Combination Acts. Unions were legalised in the Combination Acts of 1824 and 1825, however some union actions, such as anti- scab activities were restricted.

Chartism

Chartism was a working-class movement for political reform in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom that erupted from 1838 to 1857 and was strongest in 1839, 1842 and 1848. It took its name from the People's Charter of ...

was possibly the first mass working-class labour movement in the world, originating in England during the mid-19th century between 1838 and 1848. It takes its name from the People's Charter of 1838, which stipulated the six main aims of the movement as:

*Suffrage

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise is the right to vote in public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in English, the right to v ...

for all men age 21 and over

*Voting by secret ballot

*Equal-sized constituencies

An electoral (congressional, legislative, etc.) district, sometimes called a constituency, riding, or ward, is a geographical portion of a political unit, such as a country, state or province, city, or administrative region, created to provi ...

*Pay for Members of Parliament

*An end to the need for a property qualification

Property is a system of rights that gives people legal control of valuable things, and also refers to the valuable things themselves. Depending on the nature of the property, an owner of property may have the right to consume, alter, share, re ...

for Parliament

*Annual election of Parliament

Eventually, after Chartism died out, the United Kingdom adopted the first five reforms. The Chartist movement had a lasting impact in the development of the political labour movement.

In the United Kingdom, the term " new unionism" was used in the 1880s to describe an innovative form of trade unionism. The new unions were generally less exclusive than craft unions

Craft unionism refers to a model of trade unionism in which workers are organised based on the particular craft or trade in which they work. It contrasts with industrial unionism, in which all workers in the same industry are organized into the sa ...

and attempted to recruit a wide range of unskilled and semi-skilled workers, such as dockers, seamen, gasworkers and general labourers.

Worldwide

TheInternational Workingmen's Association

The International Workingmen's Association (IWA; 1864–1876), often called the First International, was a political international which aimed at uniting a variety of different left-wing socialist, social democratic, communist, and anarchist g ...

, the first attempt at international coordination, was founded in London in 1864. The major issues included the right of the workers to organize themselves, and the right to an 8-hour working day. In 1871 workers in France rebelled and the Paris Commune was formed. From the mid-19th century onward the labour movement became increasingly globalised:

The movement gained major impetus during the late 19th and early 20th centuries from the Catholic Social Teaching

Catholic social teaching (CST) is an area of Catholic doctrine which is concerned with human dignity and the common good in society. It addresses oppression, the role of the state, subsidiarity, social organization, social justice, and w ...

tradition which began in 1891 with the publication of Pope Leo XIII

Pope Leo XIII (; born Gioacchino Vincenzo Raffaele Luigi Pecci; 2March 181020July 1903) was head of the Catholic Church from 20 February 1878 until his death in July 1903. He had the fourth-longest reign of any pope, behind those of Peter the Ap ...

's foundational document, ''Rerum novarum

''Rerum novarum'', or ''Rights and Duties of Capital and Labor'', is an encyclical issued by Pope Leo XIII on 15 May 1891. It is an open letter, passed to all Catholic patriarchs, primates, archbishops, and bishops, which addressed the condi ...

'', also known as "On the Condition of the Working Classes," in which he advocated a series of reforms including limits on the length of the work day, a living wage, the elimination of child labour, the rights of labour to organise, and the duty of the state to regulate labour conditions.

Throughout the world, action by labourists has resulted in reforms and workers' rights

Labor rights or workers' rights are both legal rights and human rights relating to labor relations between workers and employers. These rights are codified in national and international labor and employment law. In general, ...

, such as the two-day weekend

The weekdays and weekend are the complementary parts of the week, devoted to labour and rest, respectively. The legal weekdays (British English), or workweek (American English), is the part of the seven-day week devoted to working. In most o ...

, minimum wage

A minimum wage is the lowest remuneration that employers can legally pay their employees—the price floor below which employees may not sell their labor. List of countries by minimum wage, Most countries had introduced minimum wage legislation b ...

, paid holiday

A holiday is a day or other period of time set aside for festivals or recreation. ''Public holidays'' are set by public authorities and vary by state or region. Religious holidays are set by religious organisations for their members and are often ...

s, and the achievement of the eight-hour day

The eight-hour day movement (also known as the 40-hour week movement or the short-time movement) was a social movement to regulate the length of a working day, preventing excesses and abuses of working time.

The modern movement originated i ...

for many workers. There have been many important labour activists in modern history who have caused changes that were revolutionary at the time and are now regarded as basic. For example, Mary Harris Jones

Mary G. Harris Jones (1837 (baptized) – November 30, 1930), known as Mother Jones from 1897 onward, was an Irish-born American labor organizer, former schoolteacher, and dressmaker who became a prominent union organizer, community organi ...

, better known as "Mother Jones", and the National Catholic Welfare Council

The National Catholic Welfare Council (NCWC) was the annual meeting of the American Catholic hierarchy and its standing secretariat; it was established in 1919 as the successor to the emergency organization, the National Catholic War Council.

It c ...

were important in the campaign to end child labour

Child labour is the exploitation of children through any form of work that interferes with their ability to attend regular school, or is mentally, physically, socially and morally harmful. Such exploitation is prohibited by legislation w ...

in the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

during the early 20th century.

Historically labour markets have often been constrained by national borders that have restricted movement of workers. Labour laws are also primarily determined by individual nations or states within those nations. While there have been some efforts to adopt a set of international labour standards through the International Labour Organisation (ILO), international sanctions for failing to meet such standards are very limited. In many countries labour movements have developed independently and represent those national boundaries.

Australia

Brazil

Germany

Japan

South Korea

South Africa

Spain

Sweden

United States

Overview

Trade unions

Political parties

Modern labour parties originated from an increase in organising activities in Europe and European colonies during the 19th century, such as theChartist movement

Chartism was a working-class movement for political reform in the United Kingdom that erupted from 1838 to 1857 and was strongest in 1839, 1842 and 1848. It took its name from the People's Charter of 1838 and was a national protest movement, wi ...

in the United Kingdom during 1838–48.

In 1891, localised labour parties were formed, by trade union members in British colonies in Australasia

Australasia is a subregion of Oceania, comprising Australia, New Zealand (overlapping with Polynesia), and sometimes including New Guinea and surrounding islands (overlapping with Melanesia). The term is used in a number of different context ...

. In 1899, the Labour Party for the Colony of Queensland

The Colony of Queensland was a colony of the British Empire from 1859 to 1901, when it became a State in the federal Australia, Commonwealth of Australia on 1 January 1901. At its greatest extent, the colony included the present-day Queensland, ...

briefly formed the world's first labour government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a State (polity), state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive (government), execu ...

, lasting one week. From 1901, when six colonies federated to form the Commonwealth of Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising the mainland of the Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and numerous smaller islands. It has a total area of , making it the sixth-largest country in ...

, several labour parties amalgamated to form the Australian Labor Party

The Australian Labor Party (ALP), also known as the Labor Party or simply Labor, is the major Centre-left politics, centre-left List of political parties in Australia, political party in Australia and one of two Major party, major parties in Po ...

(ALP).

The British Labour Party

The Labour Party, often referred to as Labour, is a List of political parties in the United Kingdom, political party in the United Kingdom that sits on the Centre-left politics, centre-left of the political spectrum. The party has been describe ...

was created as the Labour Representation Committee, following an 1899 resolution by the Trade Union Congress

The Trades Union Congress (TUC) is a national trade union centre, a federation of trade unions that collectively represent most unionised workers in England and Wales. There are 48 affiliated unions with a total of about 5.5 million members. P ...

.

While archetypal labour parties are made of direct union representatives, in addition to members of geographical branches, some union federations or individual unions have chosen not to be represented within a labour party and/or have ended association with them.

Cooperatives

Culture

Labour festivals

Labour festivals have long been a part of the labour movement. Often held outdoors in the summer, the music, talks, food, drink, and film have attracted hundreds of thousands of attendees each year. Labour festival is a yearly feast of all the unionism gathering, to celebrate the fulfillment of their goals, to bring solutions to certain hindrances and to reform unjust actions of their employers or government.Topics

Racial equality

A degree of strategic biracial cooperation existed among black and white dockworkers on the waterfronts of New Orleans, Louisiana during the early 20th century. Although the groups maintained racially separate labour unions, they coordinated efforts to present a united front when making demands of their employers. These pledges included a commitment to the "50-50" or "half-and-half" system wherein a dock crew would consist of 50% black and 50% white workers and agreement on a single wage demand to reduce the risk of ship owners pitting one race against the other. This cooperative framework, though exceptional for its time, was driven largely by the dockworkers' shared vulnerability to exploitative labor practices. The "half-and-half" rule became a symbol of solidarity and a practical mechanism to prevent racial division being used as a tool for wage suppression. Despite institutional segregation, joint action during strikes and negotiations fostered a culture of mutual dependence that challenged prevailing norms in the Jim Crow South. These alliances were not without tension, but they succeeded in stabilizing labor conditions and resisting employer manipulation. Over the decades, such practices influenced later union efforts to integrate labor representation and contributed to broader struggles for racial and economic justice in the American labor movement.Arnesen, Eric. (2008). ''Black Protest and the Great Migration: A Brief History with Documents''. Bedford/St. Martin’s. See also Arnesen, Eric. (1994). "Waterfront Workers of New Orleans: Race, Class, and Politics, 1863–1923". University of Illinois Press. Black and white dockworkers also cooperated during protracted labour strikes, including the general levee strikes in 1892 and 1907 as well as smaller strikes involving skilled workers such as screwmen in the early 1900s:Contemporary

Development of an international labour movement

With ever-increasing levels of international trade and increasing influence of multinational corporations, there has been debate and action among labour movements to attempt international co-operation. This has resulted in renewed efforts to organize and collectively bargain internationally. A number of international union organizations have been established in an attempt to facilitate international collective bargaining, to share information and resources and to advance the interests of workers generally.Waterman, Peter. ''Globalization, Social Movements and the New Internationalisms''. London: Mansell, 1998.See also

Notes

References

Further reading

* Geary, Dick. "Socialism, Revolution and the European Labour Movement, 1848-1918." ''Historical Journal'' 15, no. 4 (1972): 794–803online

. *Robert N. Stern, Daniel B. Cornfield, ''The U.S. labor movement:References and Resources'', G.K. Hall & Co 1996 *John Hinshaw and Paul LeBlanc (ed.), ''U.S. labor in the twentieth century: studies in working-class struggles and insurgency'', Amherst, NY: Humanity Books, 2000 * *Philip Yale Nicholson, ''Labor's story in the United States'', Philadelphia, Pa.: Temple Univ. Press 2004 (Series 'Labor in Crisis'), * Beverly Silver: ''Forces of Labor. Worker's Movements and Globalization since 1870'', Cambridge University Press, 2003, *St. James Press Encyclopedia of Labor History Worldwide, St. James Press 2003 *Lenny Flank (ed), ''IWW: A Documentary History'', Red and Black Publishers, St Petersburg, Florida, 2007. * Tom Zaniello: ''Working Stiffs, Union Maids, Reds, and Riffraff: An Expanded Guide to Films about Labor'' (ILR Press books), Cornell University Press, revised and expanded edition 2003,

''Neither Washington Nor Stowe: Common Sense For The Working Vermonter''

The Green Mountain Anarchist Collective, Catamount Tavern Press, 2004. *

External links

The Canadian Museum of Civilization – Canadian Labour History, 1850–1999

* {{Authority control