The LaRouche movement is a political and cultural network promoting the late

Lyndon LaRouche

Lyndon Hermyle LaRouche Jr. (September 8, 1922 – February 12, 2019) was an American political activist who founded the LaRouche movement and its main organization, the National Caucus of Labor Committees (NCLC). He was a prominent conspiracy ...

and

his ideas. It has included many organizations and companies around the world, which campaign, gather information and publish books and periodicals. LaRouche-aligned organizations include the

National Caucus of Labor Committees, the

Schiller Institute, the

Worldwide LaRouche Youth Movement and, formerly, the

U.S. Labor Party. The LaRouche movement has been called "

cult

Cults are social groups which have unusual, and often extreme, religious, spiritual, or philosophical beliefs and rituals. Extreme devotion to a particular person, object, or goal is another characteristic often ascribed to cults. The term ...

-like" by ''

The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''NYT'') is an American daily newspaper based in New York City. ''The New York Times'' covers domestic, national, and international news, and publishes opinion pieces, investigative reports, and reviews. As one of ...

''.

The movement originated within the

radical leftist

student politics of 1960s U.S.. In the 1970s and 1980s hundreds of candidates ran in state

Democratic primaries in the United States on the 'LaRouche platform', while Lyndon LaRouche repeatedly campaigned for

presidential nomination

In United States politics and government, the term presidential nominee has two different meanings:

# A candidate for president of the United States who has been selected by the delegates of a political party at the party's national convention ...

. From the mid-1970s, the LaRouche network would adopt viewpoints and stances of the

far-right

Far-right politics, often termed right-wing extremism, encompasses a range of ideologies that are marked by ultraconservatism, authoritarianism, ultranationalism, and nativism. This political spectrum situates itself on the far end of the ...

. During its peak in the 1970s and 1980s, the LaRouche movement developed a private intelligence agency and contacts with foreign governments.

In 1988, LaRouche and 25 associates

were convicted on fraud charges related to fundraising. The movement called the prosecutions politically motivated.

LaRouche's widow,

Helga Zepp-LaRouche, heads political and cultural groups in Germany connected with her late husband's movement. There are also parties in France, Sweden and other European countries and branches or affiliates in Australia, Canada, the Philippines and several Latin American countries. Members engage in political organizing, fund-raising, cultural events, research and writing.

Main goals of the Lyndon LaRouche movement

* Restoration of Glass-Steagall. Since 2007, the movement has actively campaigned to restore the

Glass-Steagall Act, to separate commercial banking from speculative investment banking, protecting the former and not bailing out the latter.

* New Bretton Woods. Advocates the abandonment of

floating exchange rate

In macroeconomics and economic policy, a floating exchange rate (also known as a fluctuating or flexible exchange rate) is a type of exchange rate regime in which a currency's value is allowed to fluctuate in response to foreign exchange market ...

s and the return to

Bretton Woods-style fixed rates, with gold, or an equivalent, used as under the gold-reserve system. This is not to be confused with the

gold standard

A gold standard is a backed currency, monetary system in which the standard economics, economic unit of account is based on a fixed quantity of gold. The gold standard was the basis for the international monetary system from the 1870s to the ...

, which LaRouche did not support.

* American System. Espouses the "American System" of infrastructure projects, a "regulated banking system" and tariffs. Named for the historical

American System of

Henry Clay

Henry Clay (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the United States Senate, U.S. Senate and United States House of Representatives, House of Representatives. He was the seventh Spea ...

, but owing more to the ideas of the expansive

American School.

*

Eurasian Land Bridge. Lectures and writes on behalf of a "Eurasian land-bridge", a massive high-speed

maglev

Maglev (derived from '' magnetic levitation'') is a system of rail transport whose rolling stock is levitated by electromagnets rather than rolled on wheels, eliminating rolling resistance.

Compared to conventional railways, maglev trains h ...

railway project to span continents and re-invigorate industry and commerce.

*

Scientific pitch. Argues in favor of what they call "Verdi tuning" in classical music, in which A=432 Hz, as opposed to the common practice today of tuning to

A=440 Hz.

*

Mars colonization. Recommends

colonization of the planet Mars, on similar basis as many others in the field, that human survivability depends on territorial diversification.

*

Strategic Defense Initiative

The Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI) was a proposed missile defense system intended to protect the United States from attack by ballistic nuclear missiles. The program was announced in 1983, by President Ronald Reagan. Reagan called for a ...

. Supported

directed beam weapons for use against

ICBM

An intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) is a ballistic missile with a range (aeronautics), range greater than , primarily designed for nuclear weapons delivery (delivering one or more Thermonuclear weapon, thermonuclear warheads). Conven ...

s, and claims credit as the first to propose this to

Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan (February 6, 1911 – June 5, 2004) was an American politician and actor who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He was a member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party a ...

. LaRouche did not support rocket-based defensive systems such as

anti-ballistic missile

An anti-ballistic missile (ABM) is a surface-to-air missile designed to Missile defense, destroy in-flight ballistic missiles. They achieve this explosively (chemical or nuclear), or via hit-to-kill Kinetic projectile, kinetic vehicles, which ma ...

s.

*

Fusion Energy Foundation. The LaRouche movement proclaimed an interest in fusion energy and "beam weapons"while some scientists such as

John Clarke praised the movement, it was generally seen as a front for LaRouche's political aims. According to ''Fusion'', two members of the FEF went to the

Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

to attend a conference on "laser interaction" in December 1978.

Political organizations

LaRouche-affiliated political parties have nominated many hundreds of candidates for national and regional offices in the U.S., Canada, Sweden, Denmark, Germany, Australia and France, for almost thirty years. In countries outside the U.S., the LaRouche movement maintains its own minor parties, and they have had no significant electoral success to date. In the U.S., individuals associated with the movement have successfully sought

Democratic Party office in some elections, particularly Democratic County Central Committee posts, and been nominated for state and federal office as Democrats, although the party leadership has periodically voiced its disapproval.

United States

Political activities

LaRouche ran for U.S. president eight times, in every presidential election from 1976 to 2004. The first was with the

U.S. Labor Party. In the next seven campaigns he ran for the

Democratic Party nomination. He received federal

matching funds

Matching funds are funds that are set to be paid in proportion to funds available from other sources. Matching fund payments usually arise in situations of charity or public good. The terms cost sharing, in-kind, and matching can be used inter ...

in 2004.

LaRouche candidates who ran in various Democratic primaries, generally sought

George Wallace

George Corley Wallace Jr. (August 25, 1919 – September 13, 1998) was an American politician who was the 45th and longest-serving governor of Alabama (1963–1967; 1971–1979; 1983–1987), and the List of longest-serving governors of U.S. s ...

voters.

The LaRouche movement attracted media attention in the context of the

1986 Illinois gubernatorial election, when movement members

Janice Hart and

Mark J. Fairchild won the Democratic Primary elections for the offices of

Illinois Secretary of State

The secretary of state of Illinois is one of the six elected executive state offices of the government of Illinois, and one of the 47 Secretary of State (U.S. state government), secretaries of state in the United States. The Illinois secretary of ...

and

Illinois Lieutenant Governor respectively. Until the day after the primary, major media outlets were reporting that

George Sangmeister, Fairchild's primary opponent, was running unopposed. More than two decades later, Fairchild asked, "how is it possible that the major media, with all of their access to information, could possibly be mistaken in that way?"

Democratic gubernatorial candidate

Adlai Stevenson III was favored to win this election, having lost the previous election by a narrow margin. He refused to run on the same slate with Hart and Fairchild, forming the

Solidarity Party and running with Jane Spirgel as the Secretary of State nominee. Hart and Spirgel's opponent, Republican incumbent

James R. Thompson, won the election with 1.574 million votes.

After that primary Senator

Daniel Patrick Moynihan

Daniel Patrick Moynihan (; March 16, 1927 – March 26, 2003) was an American politician, diplomat and social scientist. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party, he represented New York (state), New York in the ...

(D-NY) accused his own party of pursuing a policy of ignoring the "infiltration by the neo-Nazi elements of Lyndon H. LaRouche", and said that too often, especially in the media, "the LaRouchites" are "dismissed as kooks". "In an age of ideology, in an age of totalitarianism, it will not suffice for a political party to be indifferent to and ignorant about such a movement", said Moynihan.

Moynihan had faced a primary challenge in 1982 from Mel Klenetsky, an associate of LaRouche.

In 1986, the LaRouche movement worked to place an AIDS initiative,

Proposition 64, on the California ballot, which lost by a 4–1 margin. It was re-introduced in 1988 and lost again by the same margin.

Federal and state officials raided movement offices in 1986. In the

ensuing trials, some leaders of the movement received prison terms for conspiracy to commit fraud, mail fraud, and tax evasion.

In 1988, Claude Jones won the chairmanship of the

Harris County Democratic Party in

Houston

Houston ( ) is the List of cities in Texas by population, most populous city in the U.S. state of Texas and in the Southern United States. Located in Southeast Texas near Galveston Bay and the Gulf of Mexico, it is the county seat, seat of ...

, and was stripped of his authority by the county executive committee before he could take office. He was removed from office by the state party chairman a few months later, in February 1989, because of Jones's alleged opposition to the Democratic presidential candidate,

Michael Dukakis

Michael Stanley Dukakis ( ; born November 3, 1933) is an American politician and lawyer who served as governor of Massachusetts from 1975 to 1979 and from 1983 to 1991. He is the longest-serving governor in Massachusetts history and only the s ...

, in favor of LaRouche.

The LaRouche movement opposed the

UN sanctions against Iraq in 1991 and the

Gulf War

, combatant2 =

, commander1 =

, commander2 =

, strength1 = Over 950,000 soldiers3,113 tanks1,800 aircraft2,200 artillery systems

, page = https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GAOREPORTS-PEMD-96- ...

in 1991. Supporters formed the "Committee to Save the Children in Iraq".

LaRouche blamed the sanctions and war on "Israeli-controlled Moslem fundamentalist groups" and the "Ariel Sharon-dominated government of Israel" whose policies were "dictated by Kissinger and company, through the

Hollinger Corporation, which has taken over ''

The Jerusalem Post

''The Jerusalem Post'' is an English language, English-language Israeli broadsheet newspaper based in Jerusalem, Israel, founded in 1932 during the Mandate for Palestine, British Mandate of Mandatory Palestine, Palestine by Gershon Agron as ''Th ...

'' for that purpose." Left-wing anti-war groups were divided over the LaRouche movement's involvement.

In the

United States Senate election in Wyoming, 2000, the Democratic Senatorial nominee, Mel Logan, was a LaRouche follower; the Republican incumbent,

Craig Thomas, won in a 76–23% landslide. In 2001, a "national citizen-candidates' movement" was created, advancing candidates for a number of elective offices across the country.

In 2006, LaRouche Youth Movement activist and Los Angeles County Democratic Central Committee member Cody Jones was honored as "Democrat of the Year" for the 43rd Assembly District of California, by the Los Angeles County Democratic Party. At the April 2007 California State Democratic Convention, LYM activist Quincy O'Neal was elected vice-chairman of the California State Democratic Black Caucus, and Wynneal Innocentes was elected corresponding secretary of the Filipino Caucus.

In November 2007, Mark Fairchild returned to Illinois to promote legislation authored by LaRouche, called the "Homeowners and Bank Protection Act of 2007", establishing a moratorium on home

foreclosure

Foreclosure is a legal process in which a lender attempts to recover the balance of a loan from a borrower who has Default (finance), stopped making payments to the lender by forcing the sale of the asset used as the Collateral (finance), coll ...

s and establishing a new federal agency to oversee all federal and state banks. He also promoted LaRouche's plan to build a high-speed railroad to connect Russia and the United States, including a

tunnel under the Bering Strait.

["LaRouche follower returns to Capitol"](_blank)

''The State Journal-Register'', November 2, 2007, archived on January 25, 2008 fro

the original

/ref>

In 2009, a volunteer table in Mattituck, New York had a picture of Obama with a "drawn-in Hitler moustache" and "a picture of Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi with Frankenstein-style bolts in her head." In July 2011, Seattle police were called by a LaRouche volunteer displaying "Obama with a Hitler-style mustache" picture at her stand, regarding a LaRouche opponent allegedly telling her "Look at me again and I'm going to punch your face." In another case, in June 2011, "the same officer was called to investigate an incident in which a man threatened to rip down several political signs displayed by LaRouche supporters." Police investigated the incident as malicious harassmentthe state's hate-crime law. At one widely reported event, Congressman Barney Frank

Barnett Frank (born March 31, 1940) is a retired American politician. He served as a member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Massachusetts from 1981 to 2013. A Democratic Party (United States), Democrat, Frank served as chairman of th ...

referred to the posters as "vile, contemptible nonsense."

In March 2010, LaRouche Youth leader Kesha Rogers won the Democratic congressional primary in Houston, Texas' 22nd District. The following day, a spokeswoman for the Texas Democratic Party stated that "La Rouche members are not Democrats. I guarantee her campaign will not receive a single dollar from anyone on our staff." In June 2012, Rogers won the Democratic congressional primary for a second time. In March 2014, Rogers received 22% of the vote in the U.S. Senate Democratic primary, placing her into a runoff election with David M. Alameel.

In March 2010, LaRouche Youth leader Kesha Rogers won the Democratic congressional primary in Houston, Texas' 22nd District. The following day, a spokeswoman for the Texas Democratic Party stated that "La Rouche members are not Democrats. I guarantee her campaign will not receive a single dollar from anyone on our staff." In June 2012, Rogers won the Democratic congressional primary for a second time. In March 2014, Rogers received 22% of the vote in the U.S. Senate Democratic primary, placing her into a runoff election with David M. Alameel.

International

The Schiller Institute and the International Caucus of Labor Committees (ICLC) are international organizations associated with the LaRouche Movement. Schiller Institute conferences have been held across the world. The ICLC is affiliated to political parties in France, Italy, Germany, Poland, Hungary, Russia, Denmark, Sweden, Mexico, the Philippines, and several South American countries. Lyndon LaRouche, who was based in Loudoun County, Virginia

Loudoun County () is in the northern part of the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. In 2020, the census returned a population of 420,959, making it Virginia's third-most populous county. The county seat is Leesburg. Loudoun County ...

, United States, and his wife, Helga Zepp-LaRouche, based in Wiesbaden

Wiesbaden (; ) is the capital of the German state of Hesse, and the second-largest Hessian city after Frankfurt am Main. With around 283,000 inhabitants, it is List of cities in Germany by population, Germany's 24th-largest city. Wiesbaden form ...

, Germany, regularly attended these international conferences and met foreign politicians, bureaucrats, and academics.

According to London-based SciDev.Net, the LaRouche movement has "attracted suspicion for circulating conspiracy theories and advocating for grand infrastructure projects." The movement supports the Transaqua project to divert water from the Congo River

The Congo River, formerly also known as the Zaire River, is the second-longest river in Africa, shorter only than the Nile, as well as the third-largest river in the world list of rivers by discharge, by discharge volume, following the Amazon Ri ...

to replenish Lake Chad

Lake Chad (, Kanuri language, Kanuri: ''Sádǝ'', ) is an endorheic freshwater lake located at the junction of four countries: Nigeria, Niger, Chad, and Cameroon, in western and central Africa respectively, with a catchment area in excess of . ...

.

Canada

The North American Labour Party (NALP) nominated candidates in federal elections in the 1970s. Its candidates only had 297 votes nationwide in 1979. LaRouche himself offered a draft constitution for the commonwealth of Canada in 1981. The NALP later became the Party for the Commonwealth of Canada and that ran candidates in the 1984, 1988 and 1993 elections. Those were more successful, gaining as many as 7,502 votes in 1993, but no seats. The Parti pour la république du Canada (Québec) nominated candidates for provincial elections in the 1980s under various party titles. The LaRouche affiliate now operates as the ''Committee for the Republic of Canada.''

Europe

The LaRouche Movement has a major center in Germany. The (BüSo) (Civil Rights Movement Solidarity) political party is headed by Helga Zepp-LaRouche, LaRouche's widow. It has nominated candidates for elective office and publishes the ' newspaper. Zepp-LaRouche is also the head of the German-based Schiller Institute. In 1986, Zepp-LaRouche formed the "Patriots for Germany" party, and announced that it would run a full slate of 100 candidates. The party received 0.2 percent of the 4 million votes and "failed to elect any candidates to the parliament".

''Solidarité et progrès'' (Solidarity and Progress), headed by Jacques Cheminade, is the LaRouche party in France. The party was previously known as ''Parti ouvrier européen'' (European Workers' Party) and ''Fédération pour une nouvelle solidarité'' (Federation for a New Solidarity). Its newspaper is ''Nouvelle Solidarité''. Cheminade ran for President of France

The president of France, officially the president of the French Republic (), is the executive head of state of France, and the commander-in-chief of the French Armed Forces. As the presidency is the supreme magistracy of the country, the po ...

in 1995

1995 was designated as:

* United Nations Year for Tolerance

* World Year of Peoples' Commemoration of the Victims of the Second World War

This was the first year that the Internet was entirely privatized, with the United States government ...

, 2012

2012 was designated as:

*International Year of Cooperatives

*International Year of Sustainable Energy for All

Events January

*January 4 – The Cicada 3301 internet hunt begins.

* January 12 – Peaceful protests begin in the R ...

and 2017

2017 was designated as the International Year of Sustainable Tourism for Development by the United Nations General Assembly.

Events January

* January 1 – Istanbul nightclub shooting: A gunman dressed as Santa Claus opens fire at the ...

, finishing last each time. The French LaRouche Youth Movement is headed by Élodie Viennot. Viennot supported the candidacy of Daniel Buchmann for the position of mayor of Berlin.

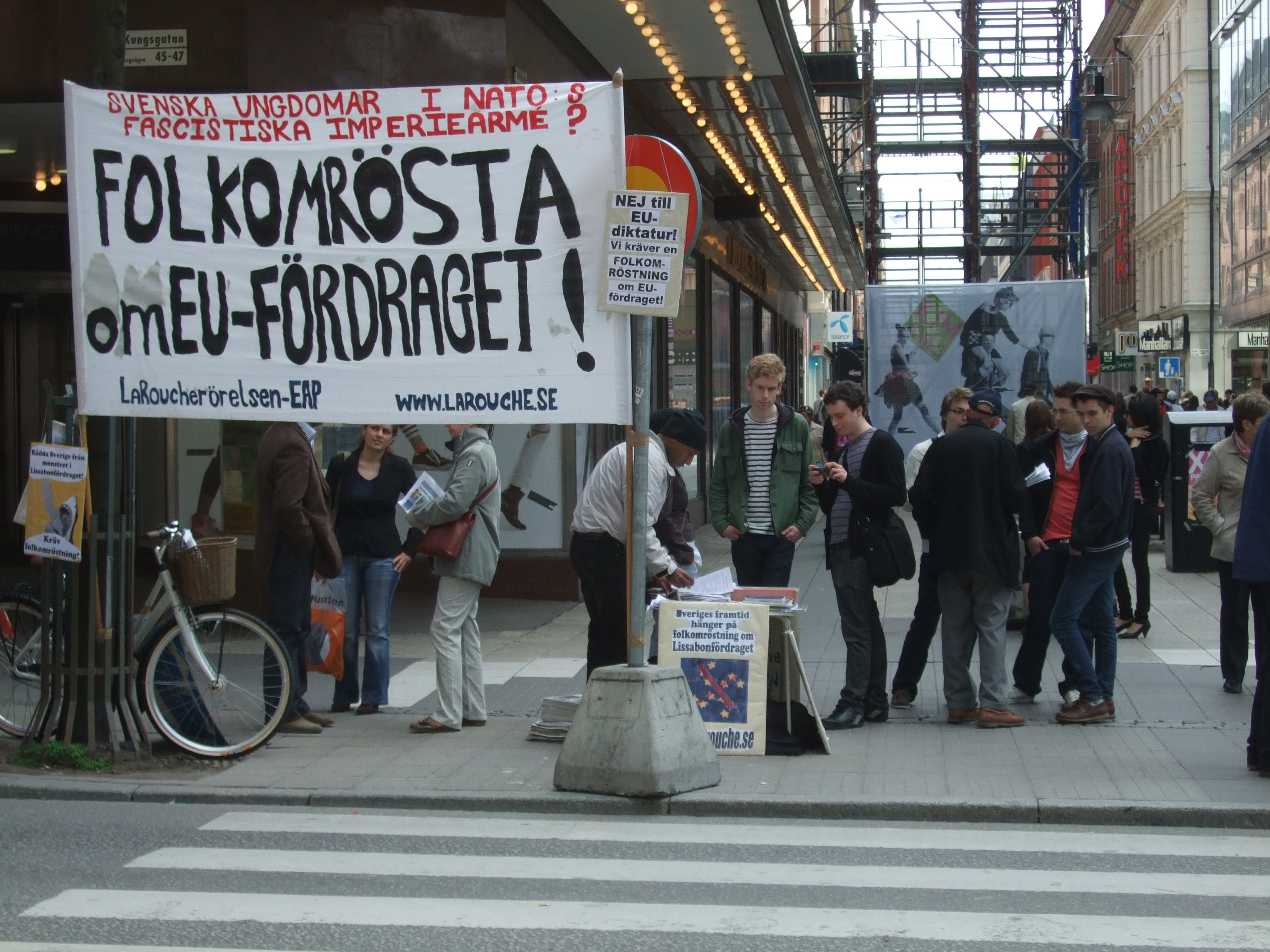

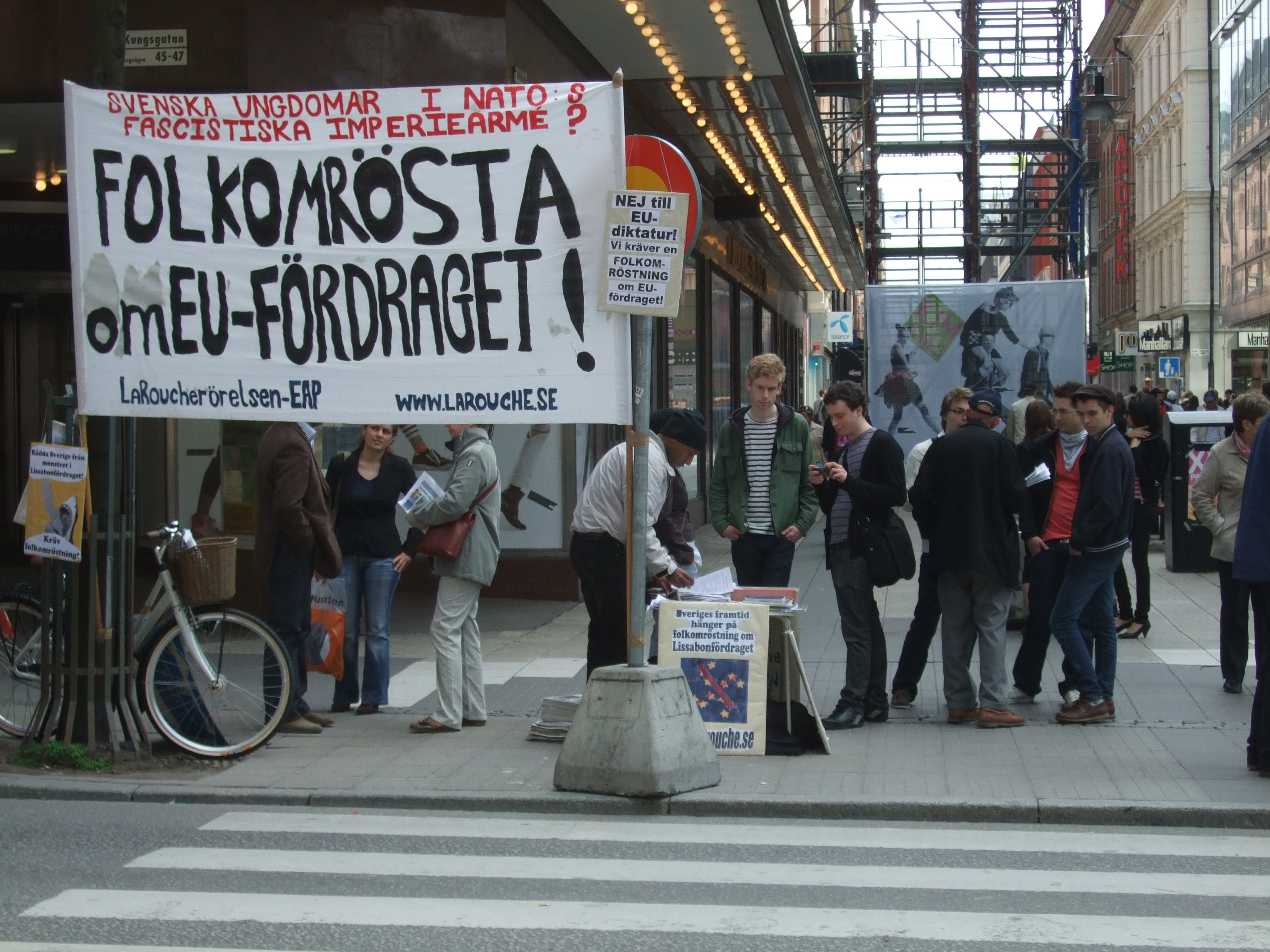

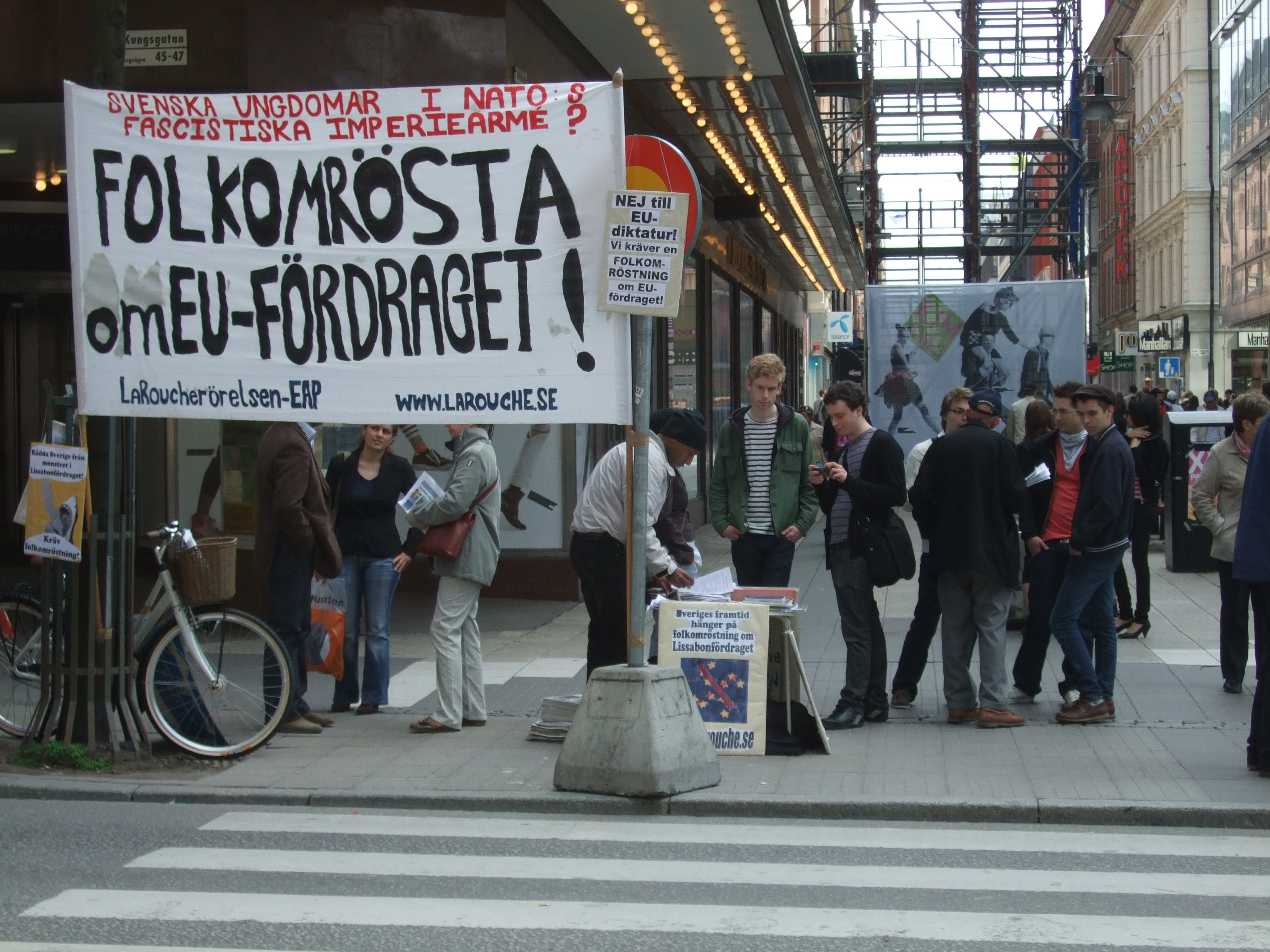

Sweden has an office of the Schiller Institute (Schillerinstitutet) and the political party European Workers Party (EAP).

In Denmark, four candidates for parliament on the LaRouche platform (Tom Gillesberg, Feride Istogu Gillesberg and Hans Schultz) received 197 votes in the 2007 election (at least 32,000 votes are needed for a local mandate). The Danish LaRouche Movement (Schiller Instituttet)'s first newspaper distributed 50,000 copies around Copenhagen and

Sweden has an office of the Schiller Institute (Schillerinstitutet) and the political party European Workers Party (EAP).

In Denmark, four candidates for parliament on the LaRouche platform (Tom Gillesberg, Feride Istogu Gillesberg and Hans Schultz) received 197 votes in the 2007 election (at least 32,000 votes are needed for a local mandate). The Danish LaRouche Movement (Schiller Instituttet)'s first newspaper distributed 50,000 copies around Copenhagen and Aarhus

Aarhus (, , ; officially spelled Århus from 1948 until 1 January 2011) is the second-largest city in Denmark and the seat of Aarhus municipality, Aarhus Municipality. It is located on the eastern shore of Jutland in the Kattegat sea and app ...

.

The (MSA) is an Italian political party headed by Paolo Raimondi that supports the LaRouche platform.

Ortrun Cramer of the Schiller Institute became a delegate of the Austrian International Progress Organization in the 1990s, but there is no sign of ongoing relationship.

Nataliya Vitrenko, leader of the Progressive Socialist Party of Ukraine, has stated multiple times that she supports LaRouche's ideals.

Controversy

The LaRouche movement has been accused of violence, harassment, and heckling since the 1970s.

1960s and Operation Mop-Up

In the 1960s and 1970s, LaRouche was accused of fomenting violence at anti-war rallies with a small band of followers.New Left

The New Left was a broad political movement that emerged from the counterculture of the 1960s and continued through the 1970s. It consisted of activists in the Western world who, in reaction to the era's liberal establishment, campaigned for freer ...

groups. He wrote that a faction of Students for a Democratic Society which later became the Weathermen began assaulting LaRouche's faction at Columbia University, and there were later attacks by the Communist Party, and the SWP. These conflicts culminated in "Operation Mop-Up", a series of physical attacks by LaRouche's National Caucus of Labor Committees (NCLC) on rival left-wing groups. LaRouche's ''New Solidarity'' reported NCLC confrontations with members of the Communist Party and Socialist Workers Party, including an April 23, 1973 incident at a debate featuring Labor Committee mayoral candidate Tony Chaitkin that erupted in a brawl, with chairs flying.[ The NCLC allegedly trained some members in terrorist and guerrilla warfare.][Blum & Montgomery (1979)][

]

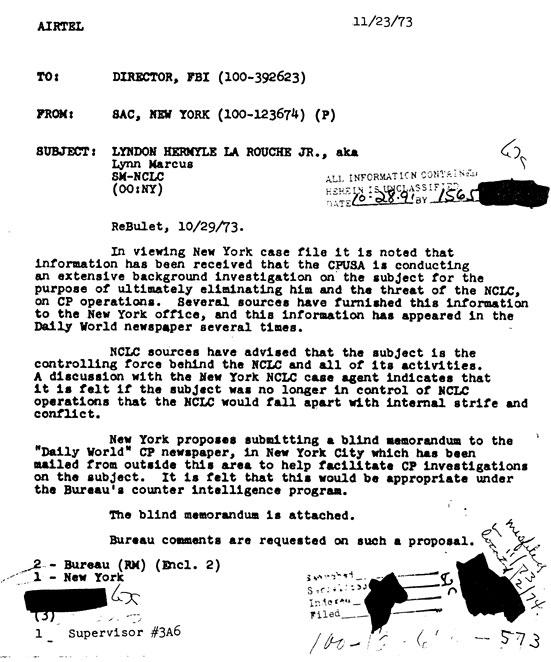

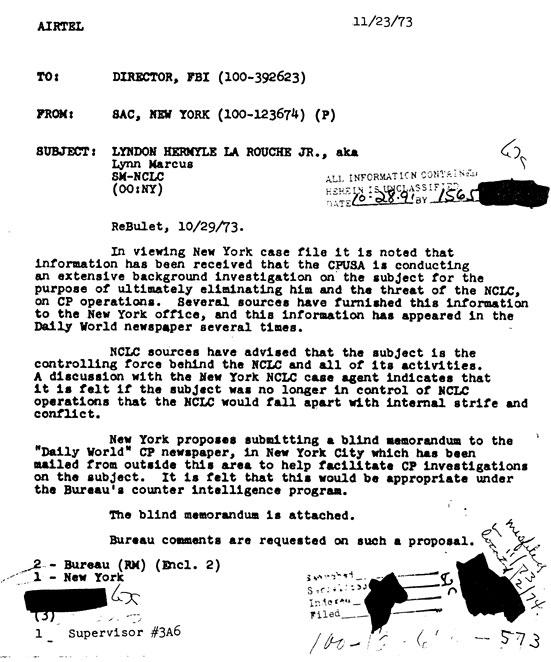

The USLP vs. the FBI

In November 1973, the FBI issued an internal memorandum, later released under the Freedom of Information Act. Jeffrey Steinberg, the NCLC "director of counterintelligence",

In November 1973, the FBI issued an internal memorandum, later released under the Freedom of Information Act. Jeffrey Steinberg, the NCLC "director of counterintelligence",COINTELPRO

COINTELPRO (a syllabic abbreviation derived from Counter Intelligence Program) was a series of covert and illegal projects conducted between 1956 and 1971 by the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) aimed at surveilling, infiltr ...

memo", which he says showed "that the FBI was considering supporting an assassination attempt against LaRouche by the Communist Party USA." LaRouche wrote in 1998:

The FBI was allegedly concerned that the movement might try to take power by force. FBI Director Clarence Kelly testified in 1976 about the LaRouche movement:

Association with Roy Frankhouser and Mitch WerBell

In the later 1970s, the U.S. Labor Party came into contact with Roy Frankhouser, a felon and government informant who had infiltrated a variety of groups. The LaRouche organization believed Frankhouser was a federal agent assigned to infiltrate right-wing and left-wing groups, and that he had evidence that these groups were being manipulated or controlled by the FBI and other agencies. Frankhouser introduced LaRouche to Mitchell WerBell III, a former Office of Strategic Services

The Office of Strategic Services (OSS) was the first intelligence agency of the United States, formed during World War II. The OSS was formed as an agency of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) to coordinate espionage activities behind enemy lines ...

operative, paramilitary trainer, and arms dealer. Some members allegedly took a six-day "anti-terrorist" course at a training camp operated by WerBell in Powder Springs, Georgia. In 1979, LaRouche denied that the training sessions took place.Jimmy Carter

James Earl Carter Jr. (October 1, 1924December 29, 2024) was an American politician and humanitarian who served as the 39th president of the United States from 1977 to 1981. A member of the Democratic Party (United States), Democratic Party ...

, Zbigniew Brzezinski

Zbigniew Kazimierz Brzeziński (, ; March 28, 1928 – May 26, 2017), known as Zbig, was a Polish-American diplomat and political scientist. He served as a counselor to Lyndon B. Johnson from 1966 to 1968 and was Jimmy Carter's National Securi ...

, Joseph Luns, and David Rockefeller

David Rockefeller (June 12, 1915 – March 20, 2017) was an American economist and investment banker who served as chairman and chief executive of Chase Bank, Chase Manhattan Corporation. He was the oldest living member of the third generation of ...

.

Labor unions

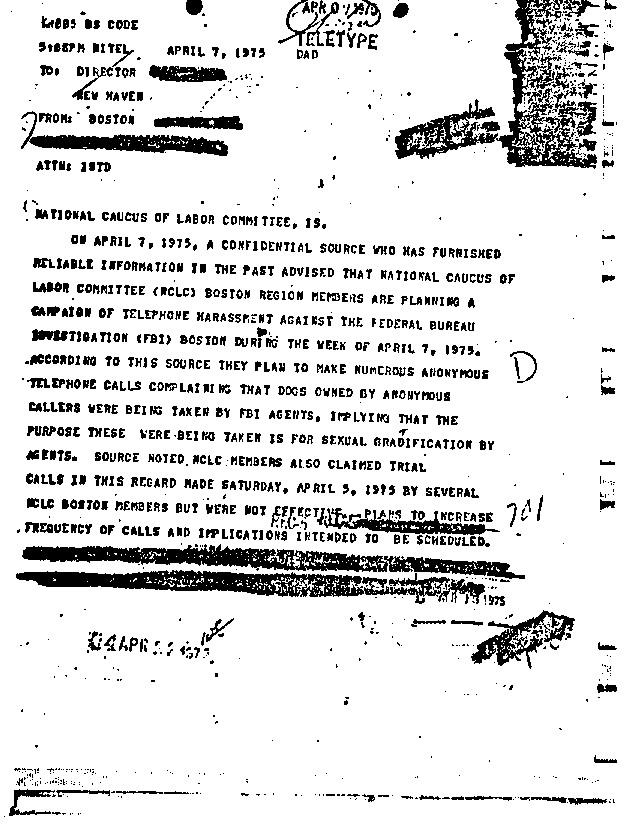

In 1974 and 1975, the NCLC allegedly targeted the United Auto Workers

The United Auto Workers (UAW), fully named International Union, United Automobile, Aerospace and Agricultural Implement Workers of America, is an American labor union that represents workers in the United States (including Puerto Rico) and sou ...

(UAW), United Farm Workers

The United Farm Workers of America, or more commonly just United Farm Workers (UFW), is a labor union for farmworkers in the United States. It originated from the merger of two workers' rights organizations, the National Farm Workers Associatio ...

(UFW), and other trade unionists. They dubbed their campaign "Operation Mop Up Woodcock", a reference to their anti-communist campaign of 1973 and to UAW president Leonard Woodcock. The movement staged demonstrations that allegedly turned violent. They issued pamphlets attacking the leadership as corrupt and perverted. The UAW said that members had received dozens of calls a day accusing their relatives of homosexuality, reportedly at the direction of NCLC "security staff".AFL–CIO

The American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) is a national trade union center that is the largest federation of unions in the United States. It is made up of 61 national and international unions, together r ...

was also attacked.Teamsters

The International Brotherhood of Teamsters (IBT) is a trade union, labor union in the United States and Canada. Formed in 1903 by the merger of the Team Drivers International Union and the Teamsters National Union, the union now represents a di ...

union which was in a jurisdictional dispute with the UFW.

1980 New Hampshire presidential primary

LaRouche put substantial effort into his first Democratic Primary, held February 1980 in New Hampshire

New Hampshire ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec t ...

. Reporters, campaign workers, and party officials received calls from people impersonating reporters or ADL staff members, inquiring what "bad news" they had heard about LaRouche. LaRouche acknowledged that his campaign workers used impersonation to collect information on political opponents.[ Governor Hugh Gallen, State Attorney General Thomas Rath and other officials received harassing phone calls.]Associated Press

The Associated Press (AP) is an American not-for-profit organization, not-for-profit news agency headquartered in New York City.

Founded in 1846, it operates as a cooperative, unincorporated association, and produces news reports that are dist ...

, found in a LaRouche campaign worker's hotel room; the list stated, "these are the criminals to burnwe want calls coming in to these fellows day and night".[ LaRouche spokesman Ted Andromidas said, "We did choose to target those people for political pressure hopefully to prevent them from carrying out the kind of fraud that occurred in Tuesday's election." New Hampshire journalist Jon Prestage said he was threatened after a tense interview with LaRouche and his associates, and found several of his cats dead after he published an account of the meeting.][

]

Political opponents

According to courtroom testimony by FBI agent Richard Egan, Jeffrey and Michelle Steinberg, the heads of LaRouche's security unit, boasted of placing harassing phone calls all through the night to the general counsel of the Federal Elections Commission (FEC) when the FEC was investigating LaRouche's political contributions.["Indictment says LaRouche wanted to smear official to block probe"](_blank)

, ''Houston Chronicle'' December 17, 1986, p. 14

The Schiller Institute sent a team of ten people, headed by James Bevel, to Omaha, Nebraska

Omaha ( ) is the List of cities in Nebraska, most populous city in the U.S. state of Nebraska. It is located in the Midwestern United States along the Missouri River, about north of the mouth of the Platte River. The nation's List of United S ...

, to pursue the Franklin child prostitution ring allegations in 1990. Among the charges investigated by the grand jury was that the Omaha Police Chief Robert Wadman and other men had sex with a 15-year-old girl at a party held by the bank's owner. The LaRouche groups insisted there was a cover-up. They distributed copies of the Schiller Institute's ''New Federalist'' newspaper and went door-to-door in Wadman's neighborhood, telling residents he was a child molester. When Wadman took a job with the police department in Aurora, Illinois

Aurora is a city in northeastern Illinois, United States. It is located along the Fox River (Illinois River tributary), Fox River west of Chicago. It is the List of municipalities in Illinois, second-most populous city in Illinois, with a popul ...

, LaRouche followers went there to demand he be fired, and after he left there followed him to a third city to make accusations.

In the 1970s, Nelson Rockefeller

Nelson Aldrich "Rocky" Rockefeller (July 8, 1908 – January 26, 1979) was the 41st vice president of the United States, serving from 1974 to 1977 under President Gerald Ford. He was also the 49th governor of New York, serving from 1959 to 197 ...

was a central figure in the movement's theories. An FBI file described them as a "clandestinely oriented group of political schizophrenics who have a paranoid preoccupation with Nelson Rockefeller and the CIA." The movement strongly opposed Rockefeller's nomination for U.S. vice president and heckled his appearances. Federal authorities were reportedly concerned that the situation might turn violent.

One target of LaRouche's attention has been Henry Kissinger

Henry Alfred Kissinger (May 27, 1923 – November 29, 2023) was an American diplomat and political scientist who served as the 56th United States secretary of state from 1973 to 1977 and the 7th National Security Advisor (United States), natio ...

. LaRouche allegedly has called Kissinger a "faggot", a "traitor", a British or Soviet agent and a "Nazi", and has linked him to the murder

Murder is the unlawful killing of another human without justification (jurisprudence), justification or valid excuse (legal), excuse committed with the necessary Intention (criminal law), intention as defined by the law in a specific jurisd ...

of Aldo Moro

Aldo Moro (; 23 September 1916 – 9 May 1978) was an Italian statesman and prominent member of Christian Democracy (Italy), Christian Democracy (DC) and its centre-left wing. He served as prime minister of Italy in five terms from December 1963 ...

.[King (1989)][ In 1986, Janice Hart held a press conference to say that Kissinger was part of the international "drug mafia". Asked whether Jews were behind drug trafficking Hart replied, "That's totally nonsense. I don't consider Henry Kissinger a Jew. I consider Henry Kissinger a homosexual."

A LaRouche organization sold posters of Illinois politician ]Jane Byrne

Jane Margaret Byrne (née Burke; May 24, 1933November 14, 2014) was an American politician who served as the 50th mayor of Chicago from April 16, 1979, until April 29, 1983. Prior to her tenure as mayor, Byrne served as Chicago's commissioner of ...

described by Mike Royko

Michael Royko Jr. (September 19, 1932 – April 29, 1997) was an American newspaper columnist from Chicago, Illinois. Over his 42-year career, he wrote more than 7,500 daily columns for the '' Chicago Daily News'', the ''Chicago Sun-Times'', an ...

as "border(ing) on the pornographic."Neil Hartigan

Cornelius Francis Hartigan (born May 4, 1938) is an American politician, lawyer, and judge who served as the 38th Attorney General of Illinois and the 40th Lieutenant Governor of Illinois. He is a member of the Democratic Party (United States), ...

's home was visited late at night by a group of LaRouche followers who chanted, sang, and used a bullhorn "to exorcise the demons out of Neil Hartigan's soul". Before the primaries a group of LaRouche supporters reportedly stormed the campaign offices of Hart's opponent and demanded that a worker "take an AIDS test".Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan (February 6, 1911 – June 5, 2004) was an American politician and actor who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He was a member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party a ...

as he was leaving a White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. Located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue Northwest (Washington, D.C.), NW in Washington, D.C., it has served as the residence of every U.S. president ...

press conference, demanding to know why LaRouche was not receiving Secret Service

A secret service is a government agency, intelligence agency, or the activities of a government agency, concerned with the gathering of intelligence data. The tasks and powers of a secret service can vary greatly from one country to another. For i ...

protection. As a result, future press conferences in the East Room were arranged with the door behind the president so he can leave without passing through the reporters. In 1992, a follower shook hands with President George H. W. Bush

George Herbert Walker BushBefore the outcome of the 2000 United States presidential election, he was usually referred to simply as "George Bush" but became more commonly known as "George H. W. Bush", "Bush Senior," "Bush 41," and even "Bush th ...

at a campaign visit to a shopping center. The follower would not let go, demanding to know, "When are you going to let LaRouche out of jail?" The Secret Service had to intervene.

During the 1988 presidential campaign, LaRouche activists spread a rumor that the Democratic candidate, Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis

Michael Stanley Dukakis ( ; born November 3, 1933) is an American politician and lawyer who served as governor of Massachusetts from 1975 to 1979 and from 1983 to 1991. He is the longest-serving governor in Massachusetts history and only the s ...

, had received professional treatment for two episodes of mental depression. Media sources did not report the rumor initially to avoid validating it.Americans with Disabilities Act

The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 or ADA () is a civil rights law that prohibits discrimination based on disability. It affords similar protections against discrimination to Americans with disabilities as the Civil Rights Act of 1964, ...

, which he signed upon gaining office and which became one of his proudest legacies.

At a 2003 Democratic primary debate repeatedly interrupted by hecklers, Joe Lieberman

Joseph Isadore Lieberman (; February 24, 1942 – March 27, 2024) was an American politician and lawyer who served as a United States senator from Connecticut from 1989 to 2013. Originally a member of the Democratic Party (United States), Dem ...

quoted John McCain

John Sidney McCain III (August 29, 1936 – August 25, 2018) was an American statesman and United States Navy, naval officer who represented the Arizona, state of Arizona in United States Congress, Congress for over 35 years, first as ...

, "no one's been elected since 1972 that Lyndon LaRouche and his people have not protested". The first reported incidence of heckling by LaRouche followers was at the Watergate hearings in 1973. Since then, LaRouche followers have repeatedly disrupted speaking events and debates featuring a large variety of speakers.

Conflict with journalists

In the 1980s, journalists including Joe Klein

Joe Klein (born September 7, 1946) is an American political commentator and author. He is best known for his work as a columnist for ''Time'' magazine and his novel '' Primary Colors'', an anonymously written roman à clef portraying Bill Clinton ...

and Chuck Fager from Boston's alternative weekly, '' The Real Paper'', and ''Chicago Tribune

The ''Chicago Tribune'' is an American daily newspaper based in Chicago, Illinois, United States. Founded in 1847, it was formerly self-styled as the "World's Greatest Newspaper", a slogan from which its once integrated WGN (AM), WGN radio and ...

'' columnist Mike Royko

Michael Royko Jr. (September 19, 1932 – April 29, 1997) was an American newspaper columnist from Chicago, Illinois. Over his 42-year career, he wrote more than 7,500 daily columns for the '' Chicago Daily News'', the ''Chicago Sun-Times'', an ...

alleged harassment and intimidation by LaRouche groups.[ After Royko wrote about a LaRouche organization, Royko said that leaflets appeared, alleging he had had a sex-change operation.][

In 1984, Patricia Lynch co-produced an NBC news piece and a TV documentary on LaRouche. She was then impersonated by LaRouche followers who interfered with her reporting.][ LaRouche sued Lynch and NBC for libel, and NBC countersued. During the trial followers picketed the NBC's offices with signs that said "Lynch Pat Lynch", and the NBC switchboard received a death threat.][ A LaRouche spokesman said they had no knowledge of the death threat.][ An editor of the ''Centre Daily Times'' in ]State College, Pennsylvania

State College is a Borough (Pennsylvania), borough and Home rule municipality (Pennsylvania), home rule municipality in Centre County, Pennsylvania, United States. It is a college town, home to the University Park, Pennsylvania, University Park ...

reported that a LaRouche TV crew led by Stanley Ezrol talked their way into his house in 1985 implying they were with NBC, then accused him of harassing LaRouche and producing unduly negative coverage. At the end of the interview, Ezrol allegedly asked, "Have you ever feared for your personal safety?", which the editor found to be "chilling".High Times

''High Times'' was an American monthly magazine (and cannabis brand) that advocates the legalization of cannabis as well as other counterculture ideas. The magazine was founded in 1974 by Tom Forcade. The magazine had its own book publishing d ...

'', ''Columbia Journalism Review

The ''Columbia Journalism Review'' (''CJR'') is a biannual magazine for professional journalists that has been published by the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism since 1961. Its original purpose was "to assess the performance ...

'', and other periodicals, culminating in a full-length biography published in 1989. King alleges numerous instances of anonymous harassment and threats. Leaflets appeared from the NCLC accusing King, a newspaper publisher, and Roy Cohn, the newspaper's lawyer, of being criminals, homosexuals, or drug pushers. One leaflet included King's home address and phone number. In 1984, a LaRouche newspaper, ''New Solidarity'', published an article titled "Will Dennis King Come out of the Closet?", copies of which were distributed in his apartment building.[ Jeffrey Steinberg denied the movement had harassed King. LaRouche said that King had been "monitored" since 1979, "We have watched this little scoundrel because he is a major security threat to my life."][

]

Public altercations

From the 1970s to the 2000s, LaRouche followers have staffed tables in airports and other public areas. The tables have carried posters with topical slogans. LaRouche followers have been alleged to use a confrontational style of interaction. In 1986, the New York state elections board received dozens of complaints about people collecting signatures on nomination petitions, including allegations of misrepresentation and abusive language used towards those who would not sign.

In the mid-80s, the

From the 1970s to the 2000s, LaRouche followers have staffed tables in airports and other public areas. The tables have carried posters with topical slogans. LaRouche followers have been alleged to use a confrontational style of interaction. In 1986, the New York state elections board received dozens of complaints about people collecting signatures on nomination petitions, including allegations of misrepresentation and abusive language used towards those who would not sign.

In the mid-80s, the Secretary of State of California

The secretary of state of California is the chief clerk of the U.S. state of California, overseeing a department of 500 people. The secretary of state is elected for four year terms, like the state's other constitutional officers; the officeho ...

, March Fong Eu, received complaints from the public about harassment by people gathering signatures to qualify the " LaRouche AIDS Initiative" for the state ballot. She warned initiative sponsors that permission to circulate the petitions could be revoked unless the "offensive activities" stopped. An altercation in 1987 between a LaRouche activist and an AIDS worker resulted in battery charges filed against the latter, who was outraged by the content of some of the material on display; she was found not guilty.

In California in 2009, several grocery chains sought restraining orders, damages and injunctions against LaRouche PAC activists displaying materials related to Obama's health care plan in front of their stores, citing customer complaints.[Banicki, Elizabeth (September 4, 2009)]

"Trader Joe's Wants LaRouche PAC Barred"

, Courthouse News Service[Banicki, Elizabeth (September 4, 2009)]

, Courthouse News Service In Edmonds, Washington

Edmonds is a city in Snohomish County, Washington, United States. It is located in the southwest corner of the county, facing Puget Sound and the Olympic Mountains to the west. The city is part of the Seattle metropolitan area and is located ...

, a 70-year-old man from Armenia, grew irate at what he viewed as comparisons of Obama to Hitler. He grabbed fliers and tussled with LaRouche supporters, resulting in assault charges against him.

Latin America

Brazil's Party for Rebuilding of National Order (Prona) was described as a "LaRouche friend" and one of its members has been quoted in the ''Executive Intelligence Review'' as saying "We associate ourselves with the wave of ideas which flow from Mr. LaRouche's prodigious mind". Prona gained six seats in the Chamber of Deputies in 2002. After gaining two seats in the 2006 election, the party merged with the larger Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world.

The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left. For example, while the political systems ...

forming the Republic Party

The Liberal Party (, PL) is a far-right political party in Brazil. From its foundation in 2006 until 2019, it was called the Party of the Republic (, PR).

The party was founded in 2006 as a merger of the 1985 Liberal Party and the Party of t ...

. However, there is no independent evidence that Prona or its leaders recognized LaRouche as an influence on their policies, and it has been described as being part of the right-wing Catholic integralist political tradition.

The Ibero-American Solidarity Movement (MSIA) has been described as an offshoot of LaRouche's Labor Party in Mexico. During peace talks to resolve the Chiapas conflict, the Mexican Labor Party and the MSIA attacked the peace process and one of the leading negotiators, Bishop Samuel Ruiz García, whom it accused of fomenting the violence and of being controlled by foreigners. Posters caricaturing Ruiz as a rattlesnake appeared across the country.

The movement strongly opposes perceived manifestations of neo-colonialism

Neocolonialism is the control by a state (usually, a former colonial power) over another nominally independent state (usually, a former colony) through indirect means. The term ''neocolonialism'' was first used after World War II to refer to ...

, including the International Monetary Fund

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is a major financial agency of the United Nations, and an international financial institution funded by 191 member countries, with headquarters in Washington, D.C. It is regarded as the global lender of las ...

, the Falklands/Malvinas War, etc., and are advocates of the Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine is a foreign policy of the United States, United States foreign policy position that opposes European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. It holds that any intervention in the political affairs of the Americas by foreign ...

.

Australia

LaRouche supporters gained control of the formerly far-right Citizens Electoral Council (CEC) in the mid-1990s. The CEC publishes an irregular newspaper, ''The New Citizen''. Craig Isherwood and his spouse Noelene Isherwood are the leaders of the party.

In 2000, former

LaRouche supporters gained control of the formerly far-right Citizens Electoral Council (CEC) in the mid-1990s. The CEC publishes an irregular newspaper, ''The New Citizen''. Craig Isherwood and his spouse Noelene Isherwood are the leaders of the party.

In 2000, former Labor

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the labour ...

MP Adrian Bennett

Adrian Frank Bennett (21 January 1933 – 9 May 2006) was an Australian politician. He was a member of the Australian House of Representatives, House of Representatives from 1969 to 1975, holding the Western Australian seat of Division of Swan, ...

established the Curtin Labor Alliance, a LaRouchite political party formed as a joint venture of the CEC and the Municipal Employees Union of Western Australia. In a speech to its inaugural conference, Bennett predicted an imminent global financial collapse and described Lyndon LaRouche as the "world's leading economist", and attributing the LaRouche criminal trials to a conspiracy by the "global oligarchy

Oligarchy (; ) is a form of government in which power rests with a small number of people. Members of this group, called oligarchs, generally hold usually hard, but sometimes soft power through nobility, fame, wealth, or education; or t ...

".

The CEC opposed politician Michael Danby and the 2004 Australian anti-terrorism legislation. For the 2004 federal election, it nominated people for ninety-five seats, collected millions of dollars in contributions, and earned 34,177 votes. The CEC is concerned with Hamiltonian

Hamiltonian may refer to:

* Hamiltonian mechanics, a function that represents the total energy of a system

* Hamiltonian (quantum mechanics), an operator corresponding to the total energy of that system

** Dyall Hamiltonian, a modified Hamiltonian ...

economics and development ideas for Australia. It has been critical of Queen Elizabeth II

Elizabeth II (Elizabeth Alexandra Mary; 21 April 19268 September 2022) was Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms from 6 February 1952 until Death and state funeral of Elizabeth II, her death in 2022. ...

's ownership of an Australian zinc mine and believes that she exerted control over Australian politics through the use of prerogative power. It has been in an antagonistic relationship with the B'nai B'rith's Anti-Defamation Commission, which has been critical of the CEC for perceived anti-semitism. It has asserted that the Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world.

The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left. For example, while the political systems ...

is a descendant of the New Guard and other purported fascists such as Sir Wilfrid Kent Hughes and Sir Robert Menzies

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of '' Hruod'' () "fame, glory, honour, praise, reno ...

. The CEC also says it is fighting for "real" Labor policies (from the 1930–40s republican leanings of the Australian Labor Party

The Australian Labor Party (ALP), also known as the Labor Party or simply Labor, is the major Centre-left politics, centre-left List of political parties in Australia, political party in Australia and one of two Major party, major parties in Po ...

).

Europe

In Germany, the leader of the Green Party, Petra Kelly, reported receiving harassing phone calls that she attributed to BüSo supporters. Her speeches were picketed and disrupted by LaRouche followers for years.

Jeremiah Duggan, a student from the UK attending a conference organized by the Schiller Institute and LaRouche Youth Movement in 2003, died in Wiesbaden, Germany, after he ran down a busy road and was hit by several cars. The German police said it appeared to be suicide. A British court ruled that Duggan had died while "in a state of terror."["No Joke"](_blank)

By April Witt, ''The Washington Post'' Sunday, October 24, 2004; Page W12 Duggan's mother believes he died in connection with an attempt to recruit him. The German public prosecution service said her son committed suicide.[Degen, Wolfgang]

"Nur die Legende hat ein langes Leben"

''Wiesbadener Kurier'', April 19, 2007 (German)

Google translation

The High Court in London ordered a second inquest in May 2010, which was opened and adjourned. In 2015, a British coroner rejected the suicide verdict and found that Duggan's body bore unexplained injuries which indicated an "altercation at some stage before his death."

In Sweden, the former leader of the European Workers Party (EAP), Ulf Sandmark, started as a member of the Swedish Social Democratic Youth League (SSU), and was assigned to investigate the EAP and the ELC. After joining the EAP, he had his membership in SSU revoked. Following the Olof Palme assassination on February 28, 1986, the Swedish branch of the EAP came under scrutiny as literature published by the party was found in the apartment of the initial suspect, Victor Gunnarsson. Soon after the assassination, NBC television in the U.S. speculated that LaRouche was somehow responsible.

In Sweden, the former leader of the European Workers Party (EAP), Ulf Sandmark, started as a member of the Swedish Social Democratic Youth League (SSU), and was assigned to investigate the EAP and the ELC. After joining the EAP, he had his membership in SSU revoked. Following the Olof Palme assassination on February 28, 1986, the Swedish branch of the EAP came under scrutiny as literature published by the party was found in the apartment of the initial suspect, Victor Gunnarsson. Soon after the assassination, NBC television in the U.S. speculated that LaRouche was somehow responsible.Samoobrona

The Self-Defence of the Republic of Poland (, SRP) is a Christian socialism, Christian socialist, Populism, populist, agrarianism, agrarian, and Nationalism, nationalist list of political parties in Poland, political party and trade union in Pola ...

party, was trained at the Schiller Institute and has received funding from LaRouche, though both Lepper and LaRouche deny the connection.

In February 2008, the LaRouche movement in Europe began a campaign to prevent the ratification of the Treaty of Lisbon

The Treaty of Lisbon (initially known as the Reform Treaty) is a European agreement that amends the two treaties which form the constitutional basis of the European Union (EU). The Treaty of Lisbon, which was signed by all EU member states o ...

, which, according to the U.S.-based LaRouche Political Action Committee, "empowers a supranational financial elite to take over the right of taxation and war making, and even restore the death penalty, abolished in most nations of Western Europe." LaRouche press releases suggest that the treaty has an underlying fascist agenda, based on the " Europe a Nation" ideas of Sir Oswald Mosley.

Asia, Middle East and Africa

The Philippines LaRouche Society calls for fixed exchange rate

In finance, an exchange rate is the rate at which one currency will be exchanged for another currency. Currencies are most commonly national currencies, but may be sub-national as in the case of Hong Kong or supra-national as in the case of ...

s, US/Philippine withdrawal from Iraq, denunciation of former US Vice President Dick Cheney

Richard Bruce Cheney ( ; born January 30, 1941) is an American former politician and businessman who served as the 46th vice president of the United States from 2001 to 2009 under President George W. Bush. He has been called vice presidency o ...

, and withdrawal of U.S. military advisor

Military advisors or combat advisors are military Military personnel, personnel deployed to advise on military matters. The term is often used for soldiers sent to foreign countries to aid such countries' militaries with their military education ...

s from Mindanao

Mindanao ( ) is the List of islands of the Philippines, second-largest island in the Philippines, after Luzon, and List of islands by population, seventh-most populous island in the world. Located in the southern region of the archipelago, the ...

. In 2008 it also issued calls for the freezing of foreign debt payments, the operation of the Bataan Nuclear Power Plant, and the immediate implementation of a national food production program. It has an office in Manila

Manila, officially the City of Manila, is the Capital of the Philippines, capital and second-most populous city of the Philippines after Quezon City, with a population of 1,846,513 people in 2020. Located on the eastern shore of Manila Bay on ...

, operates a radio show and says on its website, "Lyndon LaRouche is our civilization's last chance at world peace and development. May God help us." On the matter of internal politics, LaRouche operative Mike Billington wrote in 2004, "The Philippines Catholic Church, too, is divided at the top over the crisis. The Church under Cardinal aimeSin, who is now retired, had given its full support to the 'people's power' charade for the overthrow of Marcos and Estrada, but other voices are heard today." Later that year, he wrote:

According to Billington, representatives of LaRouche's '' Executive Intelligence Review'' and Schiller Institute had met with Marcos in 1985, at which time LaRouche was warning that Marcos would be the target of a coup, inspired by George Shultz

George Pratt Shultz ( ; December 13, 1920February 6, 2021) was an American economist, businessman, diplomat and statesman. He served in various positions under two different Republican presidents and is one of the only two persons to have held f ...

and neoconservatives in the Reagan administration, because of Marcos' opposition to the policies of the International Monetary Fund

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) is a major financial agency of the United Nations, and an international financial institution funded by 191 member countries, with headquarters in Washington, D.C. It is regarded as the global lender of las ...

.[ In 1986, LaRouche asserted that Marcos was ousted because he hadn't listened to LaRouche's advice: "he was opposed to me and he fell as a result."]Ba'ath Party

The Arab Socialist Ba'ath Party ( ' ), also known simply as Bath Party (), was a political party founded in Syria by Michel Aflaq, Salah al-Din al-Bitar, and associates of Zaki al-Arsuzi. The party espoused Ba'athism, which is an ideology ...

of Iraq.The Christian Science Monitor

''The Christian Science Monitor'' (''CSM''), commonly known as ''The Monitor'', is a nonprofit news organization that publishes daily articles both in Electronic publishing, electronic format and a weekly print edition. It was founded in 1908 ...

'' was part of a campaign directed at African Americans.

The Lyndon LaRouche Political Action Committee (LaRouchePAC) has been vocal in its support for the construction of the Thai Canal

The Thai Canal (), also known as Kra Canal () or Kra Isthmus Canal (), is any of several proposals for a canal that would connect the Gulf of Thailand with the Andaman Sea across the Kra Isthmus in southern Thailand. Such a canal would significa ...

across the Kra Isthmus

The Kra Isthmus (, ; ), also called the Isthmus of Kra in Thailand, is the narrowest part of the Malay Peninsula. The western part of the isthmus belongs to Ranong Province and the eastern part to Chumphon Province, both in Southern Thailan ...

of Thailand.

Periodicals and news agencies

The LaRouche organization has an extensive network of print and online publications for research and advocacy purposes.

Executive Intelligence Review

The LaRouche movement maintains its own press service, ''Executive Intelligence Review''. According to its masthead, ''EIR'' maintains international bureaus in Bogotá

Bogotá (, also , , ), officially Bogotá, Distrito Capital, abbreviated Bogotá, D.C., and formerly known as Santa Fe de Bogotá (; ) during the Spanish Imperial period and between 1991 and 2000, is the capital city, capital and largest city ...

, Berlin, Copenhagen

Copenhagen ( ) is the capital and most populous city of Denmark, with a population of 1.4 million in the Urban area of Copenhagen, urban area. The city is situated on the islands of Zealand and Amager, separated from Malmö, Sweden, by the ...

, Lima, Melbourne, Mexico City

Mexico City is the capital city, capital and List of cities in Mexico, largest city of Mexico, as well as the List of North American cities by population, most populous city in North America. It is one of the most important cultural and finan ...

, New Delhi, Paris, and Wiesbaden

Wiesbaden (; ) is the capital of the German state of Hesse, and the second-largest Hessian city after Frankfurt am Main. With around 283,000 inhabitants, it is List of cities in Germany by population, Germany's 24th-largest city. Wiesbaden form ...

, in addition to various cities in the U.S.

Broadcast

In 1986, the LaRouche movement bought WTRI, a low-powered AM radio station that covered western Maryland, northern Virginia, and parts of West Virginia. It was sold in 1991.

In 1991, the LaRouche movement began producing ''The LaRouche Connection'', a Public-access television

Public-access television (sometimes called community-access television) is traditionally a form of non-commercial mass media where the general public can create content television programming which is Narrowcasting, narrowcast through cable tele ...

cable TV program. Within ten months it was being carried in six states. Dana Scanlon, the producer, said that "We've done shows on the JFK assassination, the 'October Surprise' and shows on economic and cultural affairs".

Internet

In January 2001, LaRouche began holding regular webcasts every 1–2 months. These were public meetings, broadcast in video, where LaRouche gave a speech, followed by 1–2 hours of Q and A over the internet. The last occurred on December 18, 2003.

Other

* ''The New Federalist'' (U.S.), weekly newspaper

** New Solidarity International Press Service (NSIPS)

** NSIPS Speakers Bureau

** ''Nouvelle Solidarité'', French news agency

** ''Neue Solidarität'', published by Bürgerrechtsbewegung Solidarität in German

* ''Fidelio'', a "Journal of Poetry, Science, and Statecraft", published quarterly by Schiller Institute

* '' 21st Century Science and Technology'', a quarterly magazine covering scientific topics

* ''ΔΥΝΑΜΙΣ'' (Dynamis), the "Journal of the LaRouche Riemann method of physical economics"[McLemee, Scott]

The LaRouche Youth Movement

, ''Inside Higher Ed

''Inside Higher Ed'' is an American online publication of news, opinion, resources, events and jobs in the higher education sphere. In 2022, Quad Partners, a private equity firm, sold it to Times Higher Education, itself owned by Inflexion Priv ...

'', July 11, 2007

Dynamis website

Books and pamphlets

* LaRouche, Lyndon, ''The Power of Reason'' (1980) (autobiography)

* LaRouche, Lyndon, ''There Are No Limits to Growth'' (1983)

* LaRouche, Lyndon, ''So, You Wish To Learn All About Economics'' (1984)

* LaRouche, Lyndon, ''The Power of Reason 1988'' (1988)

* LaRouche, Lyndon, ''The Science of Christian Economy'' (1991)

Defunct periodicals

* ''New Solidarity''

* '' Fusion''

* '' International Journal of Fusion Energy''

* ''The Loudon County News''

* ''Investigative Leads ''

* ''War on Drugs ''

* ''The Young Scientist''

* ''Campaigner Magazine ''

* ''American Labor Beacon''

* ''Middle East Insider''

Lawsuits

In 1979, the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) was sued by the U.S. Labor Party, the National Caucus of Labor Committees, and several individuals including Konstandinos Kalimtgis, Jeffrey Steinberg, and David Goldman, who claimed libel, slander, invasion of privacy, and assault on account of the ADL's accusations of anti-Semitism. A New York State Supreme Court judge ruled that it was " fair comment" to describe them as anti-Semites.

''United States v. Kokinda'' was heard by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1990. The case concerned the First Amendment rights of LaRouche movement members on Post Office property. The Deputy Solicitor General arguing the government's case was future Supreme Court Chief Justice John G. Roberts. The Court confirmed the convictions of Marsha Kokinda and Kevin Pearl, volunteers for the National Democratic Policy Committee, finding that the Postal Service's regulation of solicitors was reasonable.

Characterizations

According to a biography produced by the LaRouche-affiliated Schiller Institute, the movement is based on a commitment to "a just new world economic order", specifically "the urgency of affording what have been sometimes termed 'Third World nations,' their full rights to perfect national sovereignty, and to access to the improvement of their educational systems and economies through employment of the most advanced science and technology."

The LaRouche movement has often been considered a far-right

Far-right politics, often termed right-wing extremism, encompasses a range of ideologies that are marked by ultraconservatism, authoritarianism, ultranationalism, and nativism. This political spectrum situates itself on the far end of the ...

political movement.[King 1989, pp. 132–133.]antisemitic

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

, a political cult, a personality cult, and a criminal enterprise, reflecting LaRouche's shift from a left-wing Marxist to a right-wing anti-communist

Anti-communism is political and ideological opposition to communist beliefs, groups, and individuals. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in Russia, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, when th ...

and American conservative.United States National Security Council

The United States National Security Council (NSC) is the national security council used by the president of the United States for consideration of national security, military, and Foreign relations of the United States, foreign policy matter ...

, as "one of the best private intelligence services in the world".["Some Officials Find Intelligence Network 'Useful'"](_blank)

, ''The Washington Post'', January 15, 1985 The Heritage Foundation

The Heritage Foundation (or simply Heritage) is an American Conservatism in the United States, conservative think tank based in Washington, D.C. Founded in 1973, it took a leading role in the conservative movement in the 1980s during the Presi ...

called it "one of the strangest political groups in American history", and '' The Washington Monthly'' called it a "vast and bizarre vanity press".cult of personality

A cult of personality, or a cult of the leader,Cas Mudde, Mudde, Cas and Kaltwasser, Cristóbal Rovira (2017) ''Populism: A Very Short Introduction''. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 63. is the result of an effort which is made to create ...

". In rebuttal, LaRouche called the accusations of being a cult figure "garbage", and denied having control over any of the groups affiliated with him.Chip Berlet

John Foster "Chip" Berlet (; born November 22, 1949) is an American investigative journalist, research analyst, photojournalist, scholar, and activist specializing in the study of extreme right-wing movements in the United States. He also studie ...

and Matthew N. Lyons:

In the summer of 2009, LaRouche followers came under criticism from both Democrats and Republicans for comparing the then United States president Barack Obama

Barack Hussein Obama II (born August 4, 1961) is an American politician who was the 44th president of the United States from 2009 to 2017. A member of the Democratic Party, he was the first African American president in American history. O ...

to Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

. Media figures as politically diverse as Rush Limbaugh

Rush Hudson Limbaugh III ( ; January 12, 1951 – February 17, 2021) was an American Conservatism in the United States, conservative political commentator who was the host of ''The Rush Limbaugh Show'', which first aired in 1984 and was nati ...

and Jon Stewart

Jon Stewart (born Jonathan Stuart Leibowitz, November 28, 1962) is an American comedian, writer, producer, director, political commentator, actor, and television host. The long-running host of ''The Daily Show'' on Comedy Central from 1999 to 20 ...

criticized the comparison.

Organizations

Current organizations

* ''Executive Intelligence Review'' Press Service (U.S.), a hub of the LaRouche movement

* National Caucus of Labor Committees (U.S.)

* Worldwide LaRouche Youth Movement (international)

* LaRouche Political Action Committee (U.S.)

* Schiller Institute (international, based in Germany and U.S.)

*

* ''Executive Intelligence Review'' Press Service (U.S.), a hub of the LaRouche movement

* National Caucus of Labor Committees (U.S.)

* Worldwide LaRouche Youth Movement (international)

* LaRouche Political Action Committee (U.S.)

* Schiller Institute (international, based in Germany and U.S.)

* Bürgerrechtsbewegung Solidarität

Bürgerrechtsbewegung Solidarität (BüSo), or the Civil Rights Movement Solidarity, is a German political party founded by Helga Zepp-LaRouche, the widow of U.S. political activist Lyndon LaRouche.

The BüSo is part of the worldwide LaRouche mo ...

(Germany)

* International Caucus of Labor Committees (international, especially Canada, Australia, and others)

* Australian Citizens Party formerly Citizens Electoral Council

* Philippine LaRouche Society

* European Workers Party (Sweden)

* Comités Laborales de Nuevo León (Mexico)

* Solidarité et progrès (France)

United States businesses

* PMR Printing, Virginia

* World Composition Services, Inc. (a.k.a. WorldComp) (Ken Kronberg, former president)

* New Benjamin Franklin House Publishing Company, Inc., Leesburg, Virginia

Leesburg is a town in and the county seat of Loudoun County, Virginia, United States. It is part of both the Northern Virginia region of the state and the Washington metropolitan area, including Washington, D.C., the nation's capital.

European se ...

* American System Publications Inc., Los Angeles (Maureen Calney, president)

* Eastern States Distributors Incorporated, Pittsburgh (Starr Valenti, president)

* South East Literature (South East Political Literature Sales & Distribution, Inc.) Halethorpe, Maryland

* Southwest Literature Distribution, Houston, Texas (Daniel Leach, president)

* Midwest Circulation Corp., Chicago

* Hamilton System Distributors, Inc., Ridgefield Park, New Jersey

Ridgefield Park is a village in Bergen County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey. As of the 2020 United States census, the village's population was 13,224, an increase of 495 (+3.9%) from the 2010 census count of 12,729, which in turn reflected ...

Defunct organizations

People

Members

According to ''The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'', locally known as ''The'' ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'' or ''WP'', is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C., the national capital. It is the most widely circulated newspaper in the Washington m ...

'', LaRouche has told his followers that they are "golden souls", a term from '' The Republic'' of Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

. In his 1979 autobiography he contrasted the "golden souls" to "the poor donkeys, the poor sheep, whose consciousness is dominated by the infantile world-outlook of individual sensuous life".[ In 1986, LaRouche said during an interview, "What I represent is a growing movement. The movement is becoming stronger all the time..."

During the criminal trials of the late 1980s, LaRouche called upon his followers to be martyrs, saying that their "honorable deeds shall be legendary in the tales told to future generations". Senior members refused plea agreements that involved guilty pleas as those would have been black marks on the movement.

Former members report that life within the LaRouche movement is highly regulated. A former member of the security staff wrote in 1979 that members could be expelled for masturbating or using marijuana. Members who failed to achieve their fundraising quotas or otherwise showed signs as disloyal behavior were subjected to "ego stripping" sessions.]John Judis

John B. Judis is an author and American journalist, an editor-at-large at ''Talking Points Memo'', a former senior writer at the ''National Journal'', and a former senior editor at ''The New Republic''.

Education

Judis was born in Chicago to a f ...

, writing in ''The New Republic

''The New Republic'' (often abbreviated as ''TNR'') is an American magazine focused on domestic politics, news, culture, and the arts from a left-wing perspective. It publishes ten print magazines a year and a daily online platform. ''The New Y ...

'', stated that LaRouche followers worked 16-hour days for little wages.

Former members have reported receiving harassing calls or indirect death threats.[ Internal memos have reportedly contained a variety of dismissive terms for ex-followers.][ One former member said that becoming a follower of LaRouche is "like entering the Bizarro World of the Superman comic books" which makes sense so long as one remains inside the movement.][

E. Newbold Smith, who married a du Pont, was indicted along with four associates for planning to have his son, Lewis du Pont Smith, and daughter-in-law abducted and " deprogrammed" after they joined the LaRouche movement and donated $212,000 of Lewis's approximately $10 million inheritance to a LaRouche publishing arm. The incident resulted in serious legal repercussions but no criminal convictions for those indicted, including private investigator Galen Kelly. E. Newbold Smith also successfully had his son declared "incompetent" to manage his financial affairs in order to block him from possibly turning over his inheritance to the LaRouche organization.

Kenneth Kronberg, who had been a leading member of the movement, committed suicide in 2007, reportedly because of financial issues concerning the movement.][ His widow, Marielle (Molly) Kronberg, had also been a longtime member. She gave an interview to ]Chip Berlet

John Foster "Chip" Berlet (; born November 22, 1949) is an American investigative journalist, research analyst, photojournalist, scholar, and activist specializing in the study of extreme right-wing movements in the United States. He also studie ...

in 2007 in which she made critical comments about the LaRouche movement. She was quoted as saying, "I'm worried that the organization may be in danger of becoming a killing machine." In 2004 and 2005, Kronberg made contributions of $1,501 to the Republican National Committee

The Republican National Committee (RNC) is the primary committee of the Republican Party of the United States. Its members are chosen by the state delegations at the national convention every four years. It is responsible for developing and pr ...

and the election campaign of George W. Bush

George Walker Bush (born July 6, 1946) is an American politician and businessman who was the 43rd president of the United States from 2001 to 2009. A member of the Bush family and the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party, he i ...

,[ despite the LaRouche movement's opposition to the Bush administration. According to journalist Avi Klein, LaRouche felt that this "foreshadowed her treachery to the movement."][ Kronberg had been a member of the movement's governing National Committee since 1982 and was convicted of fraud during the LaRouche criminal trials.

]

Associates and managers

* Helga Zepp-LaRouche, widow, head of Schiller Institute and Bürgerrechtsbewegung Solidarität

Bürgerrechtsbewegung Solidarität (BüSo), or the Civil Rights Movement Solidarity, is a German political party founded by Helga Zepp-LaRouche, the widow of U.S. political activist Lyndon LaRouche.

The BüSo is part of the worldwide LaRouche mo ...

Amelia Boynton Robinson

Amelia Isadora Platts Boynton Robinson (August 18, 1905 – August 26, 2015) was an American activist and supercentenarian who was a leader of the American Civil Rights Movement in Selma, Alabama, and a key figure in the 1965 Selma to Montgom ...

, SI vice chairwoman

* Michael Billington, fundraiser (convicted of mail fraud