L Ron Hubbard on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Lafayette Ronald Hubbard (March 13, 1911 – January 24, 1986) was an American author and the founder of

In 1933, Hubbard renewed a relationship with a fellow glider pilot, Margaret "Polly" Grubb and the two were quickly married on April 13.

The following year, she gave birth to a son who was named Lafayette Ronald Hubbard, Jr., later nicknamed "Nibs". A second child, Katherine May, was born two years later. The Hubbards lived for a while in Laytonsville, Maryland, but were chronically short of money. In the spring of 1936, they moved to

In 1933, Hubbard renewed a relationship with a fellow glider pilot, Margaret "Polly" Grubb and the two were quickly married on April 13.

The following year, she gave birth to a son who was named Lafayette Ronald Hubbard, Jr., later nicknamed "Nibs". A second child, Katherine May, was born two years later. The Hubbards lived for a while in Laytonsville, Maryland, but were chronically short of money. In the spring of 1936, they moved to

In 1941, Hubbard applied to join the

In 1941, Hubbard applied to join the

On August 10, 1946, Hubbard married Sara, though he was still married to his first wife Polly. Hubbard resumed his fiction writing to supplement his small disability allowance. In August 1947, Hubbard returned to the pages of ''Astounding'' with a serialized novel "The End is Not Yet", about a young nuclear physicist who tries to stop a world takeover by building a new philosophical system. In October 1947, the magazine began serializing ''

On August 10, 1946, Hubbard married Sara, though he was still married to his first wife Polly. Hubbard resumed his fiction writing to supplement his small disability allowance. In August 1947, Hubbard returned to the pages of ''Astounding'' with a serialized novel "The End is Not Yet", about a young nuclear physicist who tries to stop a world takeover by building a new philosophical system. In October 1947, the magazine began serializing ''

Accompanied by an article in ''Astounding's'' May 1950 issue, the pseudoscientific book '' Dianetics: The Modern Science of Mental Health'' was released on May 9. Although Dianetics was poorly received by the press and the scientific and medical professions, the book was an immediate commercial success and sparked "a nationwide cult of incredible proportions". Five hundred Dianetic auditing groups were set up across the United States,Staff (August 21, 1950). "Dianetics book review; Best Seller". ''Newsweek'' and Hubbard established the "Hubbard Dianetic Research Foundation". Financial controls were lax, and Hubbard himself took large sums with no explanation of what he was doing with it.

Dianetics lost public credibility on August 10 when a presentation by Hubbard before an audience of 6,000 at the

Accompanied by an article in ''Astounding's'' May 1950 issue, the pseudoscientific book '' Dianetics: The Modern Science of Mental Health'' was released on May 9. Although Dianetics was poorly received by the press and the scientific and medical professions, the book was an immediate commercial success and sparked "a nationwide cult of incredible proportions". Five hundred Dianetic auditing groups were set up across the United States,Staff (August 21, 1950). "Dianetics book review; Best Seller". ''Newsweek'' and Hubbard established the "Hubbard Dianetic Research Foundation". Financial controls were lax, and Hubbard himself took large sums with no explanation of what he was doing with it.

Dianetics lost public credibility on August 10 when a presentation by Hubbard before an audience of 6,000 at the

The practice of prominently displaying the cross in Scientology centers was instituted in 1969 following hostile press coverage where Scientology's status as a legitimate religion was being questioned. In October 1969, ''

The practice of prominently displaying the cross in Scientology centers was instituted in 1969 following hostile press coverage where Scientology's status as a legitimate religion was being questioned. In October 1969, '' Throughout this period, Hubbard was heavily involved in directing the activities of the Guardian's Office (GO), the legal bureau/intelligence agency. In 1973, he instigated the " Snow White Program" and directed the GO to remove negative reports about Scientology from government files and track down their sources. The GO carried out covert campaigns on his behalf such as Operation Bulldozer Leak, designed to convince authorities that Hubbard had no legal liability for the actions of the church. Hubbard was kept informed of these operations, including as the theft of medical records from a hospital, harassment of psychiatrists, and infiltrations of organizations such as the

Throughout this period, Hubbard was heavily involved in directing the activities of the Guardian's Office (GO), the legal bureau/intelligence agency. In 1973, he instigated the " Snow White Program" and directed the GO to remove negative reports about Scientology from government files and track down their sources. The GO carried out covert campaigns on his behalf such as Operation Bulldozer Leak, designed to convince authorities that Hubbard had no legal liability for the actions of the church. Hubbard was kept informed of these operations, including as the theft of medical records from a hospital, harassment of psychiatrists, and infiltrations of organizations such as the

The Mind Behind the Religion : Chapter Four : The Final Days : Deep in hiding, Hubbard kept tight grip on the church.

''Los Angeles Times'', retrieved February 8, 2011. Hubbard returned to Science-Fiction, writing '' Battlefield Earth'' (1982) and '' Mission Earth'', a ten-volume series published between 1985 and 1987.Queen, Edward L.; Prothero, Stephen R.; Shattuck, Gardiner H. ''Encyclopedia of American religious history'', Volume 1, p. 493. New York: Infobase Publishing, 2009. In OT VIII, dated 1980, Hubbard explains the document is intended for circulation only after his death. In the document, Hubbard denounces the historic Jesus as "a lover of young boys" given to "uncontrollable bursts of temper". Hubbard explains that "My mission could be said to fulfill the Biblical promise represented by this brief anti-Christ period." This was corroborated by a 1983 interview where Hubbard's son Nibs explained that his father believed he was the Anti-Christ.

In December 1985, Hubbard allegedly attempted suicide by custom

In OT VIII, dated 1980, Hubbard explains the document is intended for circulation only after his death. In the document, Hubbard denounces the historic Jesus as "a lover of young boys" given to "uncontrollable bursts of temper". Hubbard explains that "My mission could be said to fulfill the Biblical promise represented by this brief anti-Christ period." This was corroborated by a 1983 interview where Hubbard's son Nibs explained that his father believed he was the Anti-Christ.

In December 1985, Hubbard allegedly attempted suicide by custom

Scientology

Scientology is a set of beliefs and practices invented by the American author L. Ron Hubbard, and an associated movement. It is variously defined as a scam, a Scientology as a business, business, a cult, or a religion. Hubbard initially develo ...

. A prolific writer of pulp science fiction and fantasy novels

Fantasy literature is literature set in an imaginary universe, often but not always without any locations, events, or people from the real world. magic (paranormal), Magic, the supernatural and Legendary creature, magical creatures are common i ...

in his early career, in 1950 he authored the pseudoscientific

Pseudoscience consists of statements, beliefs, or practices that claim to be both scientific and factual but are incompatible with the scientific method. Pseudoscience is often characterized by contradictory, exaggerated or unfalsifiable cl ...

book '' Dianetics: The Modern Science of Mental Health'' and established organizations to promote and practice Dianetics techniques. Hubbard created Scientology

Scientology is a set of beliefs and practices invented by the American author L. Ron Hubbard, and an associated movement. It is variously defined as a scam, a Scientology as a business, business, a cult, or a religion. Hubbard initially develo ...

in 1952 after losing the intellectual rights to his literature on Dianetics in bankruptcy. He would lead the Church of Scientology

The Church of Scientology is a group of interconnected corporate entities and other organizations devoted to the practice, administration and dissemination of Scientology, which is variously defined as a cult, a business, or a new religiou ...

variously described as a cult

Cults are social groups which have unusual, and often extreme, religious, spiritual, or philosophical beliefs and rituals. Extreme devotion to a particular person, object, or goal is another characteristic often ascribed to cults. The term ...

, a new religious movement

A new religious movement (NRM), also known as a new religion, is a religious or Spirituality, spiritual group that has modern origins and is peripheral to its society's dominant religious culture. NRMs can be novel in origin, or they can be part ...

, or a businessuntil his death in 1986.

Born in Tilden, Nebraska, in 1911, Hubbard spent much of his childhood in Helena, Montana

Helena (; ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the U.S. state of Montana and the county seat, seat of Lewis and Clark County, Montana, Lewis and Clark County.

Helena was founded as a gold camp during the Montana gold ...

. While his father was posted to the U.S. naval base on Guam

Guam ( ; ) is an island that is an Territories of the United States, organized, unincorporated territory of the United States in the Micronesia subregion of the western Pacific Ocean. Guam's capital is Hagåtña, Guam, Hagåtña, and the most ...

in the late 1920s, Hubbard traveled to Asia and the South Pacific. In 1930, Hubbard enrolled at George Washington University

The George Washington University (GW or GWU) is a Private university, private University charter#Federal, federally-chartered research university in Washington, D.C., United States. Originally named Columbian College, it was chartered in 1821 by ...

to study civil engineering but dropped out in his second year. He began his career as an author of pulp fiction and married Margaret Grubb, who shared his interest in aviation.

Hubbard was an officer in the Navy during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, where he briefly commanded two ships but was removed from command both times. The last few months of his active service were spent in a hospital, being treated for a variety of complaints. After the war, he sought psychiatric help from a veteran's charity hospital in Georgia. While acting as a lay analyst, or peer counselor, in Georgia, Hubbard began writing what would become Dianetics. In 1951, Hubbard's wife Sara said that experts had diagnosed him with paranoid schizophrenia

Schizophrenia () is a mental disorder characterized variously by hallucinations (typically, hearing voices), delusions, disorganized thinking and behavior, and flat or inappropriate affect. Symptoms develop gradually and typically begin ...

and recommended lifelong hospitalization. In 1953, the first Scientology organizations were founded by Hubbard. In 1954 a Scientology church in Los Angeles was founded, which became the Church of Scientology International. Hubbard added organizational management strategies, principles of pedagogy

Pedagogy (), most commonly understood as the approach to teaching, is the theory and practice of learning, and how this process influences, and is influenced by, the social, political, and psychological development of learners. Pedagogy, taken ...

, a theory of communication and prevention strategies for healthy living to the teachings of Scientology. As Scientology came under increasing media attention and legal pressure in a number of countries during the late 1960s and early 1970s, Hubbard spent much of his time at sea as " commodore" of the Sea Organization, a private, quasi-paramilitary

A paramilitary is a military that is not a part of a country's official or legitimate armed forces. The Oxford English Dictionary traces the use of the term "paramilitary" as far back as 1934.

Overview

Though a paramilitary is, by definiti ...

Scientologist fleet.

Hubbard returned to the United States in 1975 and went into seclusion in the California desert after an unsuccessful attempt to take over the town of Clearwater, Florida

Clearwater is a city and the county seat of Pinellas County, Florida, United States, west of Tampa, Florida, Tampa and north of St. Petersburg, Florida, St. Petersburg. To the west of Clearwater lies the Gulf of Mexico and to the southeast lies T ...

. In 1978, Hubbard was convicted of fraud ''in absentia

''In Absentia'' is the seventh studio album by British progressive rock band Porcupine Tree, first released on 24 September 2002. The album marked several changes for the band, with it being the first with new drummer Gavin Harrison and the f ...

'' by France. In the same year, 11 high-ranking members of Scientology were indicted on 28 charges for their role in the Church's Snow White Program, a systematic program of espionage against the United States government. One of the indicted was Hubbard's wife Mary Sue Hubbard; he himself was named an unindicted co-conspirator

In criminal law, a conspiracy is an agreement between two or more people to commit a crime at some time in the future. Criminal law in some countries or for some conspiracies may require that at least one overt act be undertaken in furtherance ...

. Hubbard spent the remaining years of his life in seclusion, attended to by a small group of Scientology officials.

Following his 1986 death, Scientology leaders announced that Hubbard's body had become an impediment to his work and that he had decided to "drop his body" to continue his research on another plane of existence. The Church of Scientology describes Hubbard in hagiographic

A hagiography (; ) is a biography of a saint or an ecclesiastical leader, as well as, by extension, an wiktionary:adulatory, adulatory and idealized biography of a preacher, priest, founder, saint, monk, nun or icon in any of the world's religi ...

terms, though many of his autobiographical statements were fictitious. Sociologist Stephen Kent has observed that Hubbard "likely presented a personality disorder

Personality disorders (PD) are a class of mental health conditions characterized by enduring maladaptive patterns of behavior, cognition, and inner experience, exhibited across many contexts and deviating from those accepted by the culture. ...

known as malignant narcissism

Malignant narcissism is a theoretical personality disorder construct conceptually distinguished from typical narcissistic personality disorder (NPD) by the presence of antisocial behavior, egosyntonic sadism, and a paranoid orientation, while st ...

."

Life

Before Dianetics

Lafayette Ronald Hubbard was born on March 13, 1911,Hall, Timothy L. ''American religious leaders'', p. 175. New York: Infobase Publishing, 2003. the only child of Ledora May Waterbury, who had trained as a teacher, and Harry Ross Hubbard, a low-ranking United States Navy officer. Like many military families of the era, the Hubbards repeatedly relocated around the United States and overseas. After moving toKalispell, Montana

Kalispell (, Salish-Spokane-Kalispel language, Montana Salish: Ql̓ispé, Kutenai language: Kqayaqawakⱡuʔnam) is a city in Montana and the county seat of Flathead County, Montana, United States. The 2020 census put Kalispell's population at ...

, they settled in Helena in 1913. Hubbard's father rejoined the Navy in April 1917, during World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, while his mother worked as a clerk for the state government. After his father was posted to Guam, Hubbard and his mother traveled there with brief stop-overs in a couple of Chinese ports. In high school, Hubbard contributed to the school paper, but was dropped from enrollment due to failing grades. After he failed the Naval Academy

A naval academy provides education for prospective naval officers.

List of naval academies

See also

* Military academy

{{Authority control

Naval academies,

Naval lists ...

entrance examination, Hubbard was enrolled in a Virginia Preparatory School to prepare him for a second attempt. However, after complaining of eye strain, Hubbard was diagnosed with myopia

Myopia, also known as near-sightedness and short-sightedness, is an eye condition where light from distant objects focuses in front of, instead of on, the retina. As a result, distant objects appear blurry, while close objects appear normal. ...

, precluding any future enrollment in the Naval Academy. As an adult, Hubbard would privately write to himself that his eyes had gone bad when he "used them as an excuse to escape the naval academy".

Hubbard was sent to the Woodward School in D.C., as graduates qualified for admission to George Washington University

The George Washington University (GW or GWU) is a Private university, private University charter#Federal, federally-chartered research university in Washington, D.C., United States. Originally named Columbian College, it was chartered in 1821 by ...

without having to take the entrance exam. Hubbard graduated in June 1930 and entered GWU. Academically, Hubbard did poorly and was repeatedly warned about bad grades, but he contributed to the student newspaper and was active in the glider club. In 1932, Hubbard organized a student trip to the Caribbean, but amid multiple misfortunes and insufficient funding, the passengers took to burning Hubbard in effigy and the trip was canceled by the ship's owners. Hubbard did not return to GWU the following year.

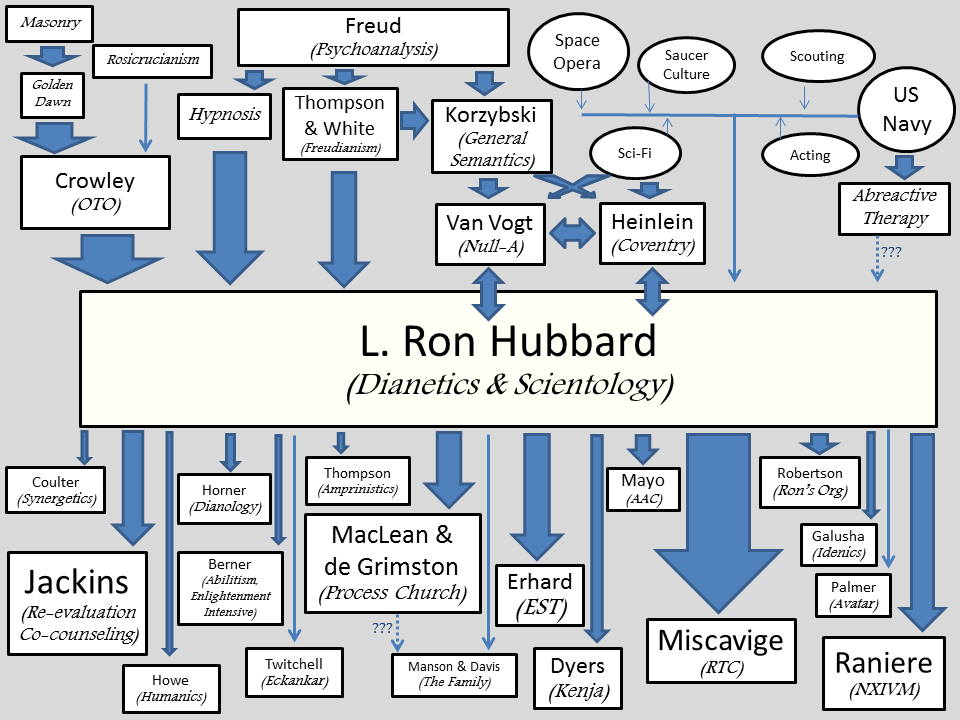

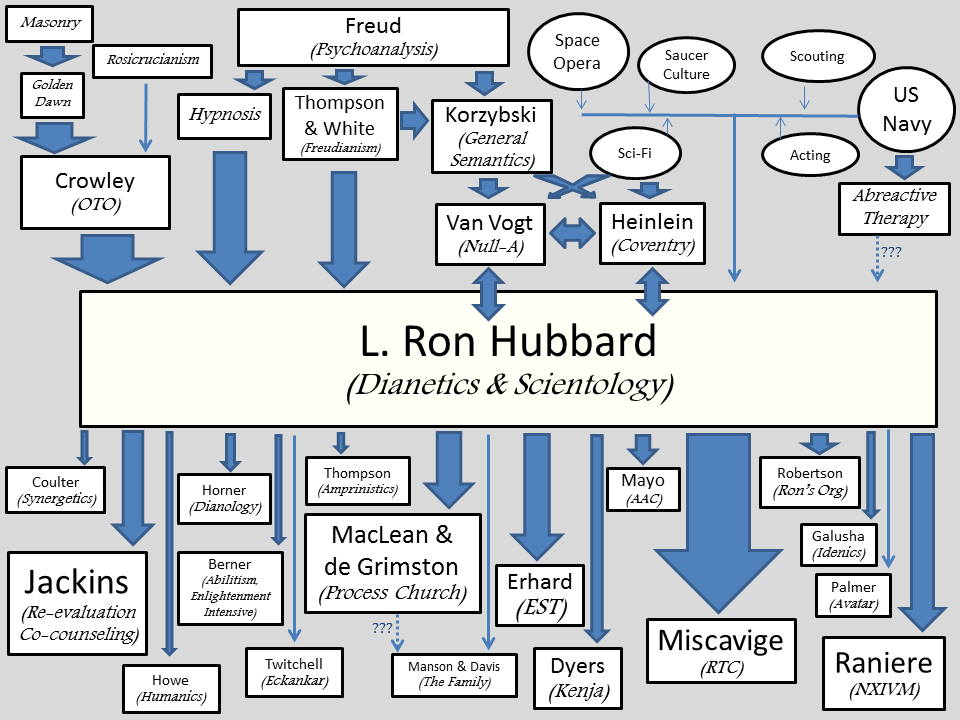

For much of the 1920s and 1930s, Hubbard lived in Washington D.C., and he would later claim to have interacted with multiple psychiatrist

A psychiatrist is a physician who specializes in psychiatry. Psychiatrists are physicians who evaluate patients to determine whether their symptoms are the result of a physical illness, a combination of physical and mental ailments or strictly ...

s in the city. Hubbard described encounters in 1923 and 1930 with navy psychiatrist Joseph Thompson. Thompson was controversial within the American psychiatric community for his support of lay analysis, the practice of psychoanalysis

PsychoanalysisFrom Greek language, Greek: and is a set of theories and techniques of research to discover unconscious mind, unconscious processes and their influence on conscious mind, conscious thought, emotion and behaviour. Based on The Inte ...

by those without medical degrees. Hubbard also recalled interacting with William Alanson White, supervisor of the D.C. psychiatric hospital St. Elizabeths.Hubbard, L. R. (February 6, 1952). Dianetics: The Modern Miracle. LRH Recorded Lectures According to Hubbard, both White and Thompson had regarded his athleticism and lack of interest in psychology as signs of a good prognosis. Hubbard later claimed to have been trained by both Thompson and White. Hubbard also discussed his interactions at Chestnut Lodge, a D.C.-area facility specializing in schizophrenia

Schizophrenia () is a mental disorder characterized variously by hallucinations (typically, Auditory hallucination#Schizophrenia, hearing voices), delusions, thought disorder, disorganized thinking and behavior, and Reduced affect display, f ...

, repeatedly complaining that their staff misdiagnosed an unnamed individual with the condition:

Pre-war fiction

In 1933, Hubbard renewed a relationship with a fellow glider pilot, Margaret "Polly" Grubb and the two were quickly married on April 13.

The following year, she gave birth to a son who was named Lafayette Ronald Hubbard, Jr., later nicknamed "Nibs". A second child, Katherine May, was born two years later. The Hubbards lived for a while in Laytonsville, Maryland, but were chronically short of money. In the spring of 1936, they moved to

In 1933, Hubbard renewed a relationship with a fellow glider pilot, Margaret "Polly" Grubb and the two were quickly married on April 13.

The following year, she gave birth to a son who was named Lafayette Ronald Hubbard, Jr., later nicknamed "Nibs". A second child, Katherine May, was born two years later. The Hubbards lived for a while in Laytonsville, Maryland, but were chronically short of money. In the spring of 1936, they moved to Bremerton, Washington

Bremerton is a city in Kitsap County, Washington, Kitsap County, Washington (state), Washington, United States. The population was 43,505 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census and an estimated 44,122 in 2021, making it the largest city ...

. They lived there for a time with Hubbard's aunts and grandmother before finding a place of their own at nearby South Colby. According to one of his friends at the time, Robert MacDonald Ford, the Hubbards were "in fairly dire straits for money" but sustained themselves on the income from Hubbard's writing.

Hubbard began a writing career and tried to write for mainstream publications. Hubbard soon found his niche in the pulp fiction magazines, becoming a prolific and prominent writer in the medium. From 1934 until 1940, Hubbard produced hundreds of short stories and novels. Hubbard is remembered for his "prodigious output" across a variety of genres, including adventure fiction, aviation, travel, mysteries, westerns, romance, and science fiction. His first full-length novel, '' Buckskin Brigades'', was published in 1937. The novel told the story of "Yellow Hair", a white man adopted into the Blackfeet tribe, with promotional material claiming the author had been a "bloodbrother" of the Blackfeet. ''The New York Times Book Review

''The New York Times Book Review'' (''NYTBR'') is a weekly paper-magazine supplement to the Sunday edition of ''The New York Times'' in which current non-fiction and fiction books are reviewed. It is one of the most influential and widely rea ...

'' praised the book, writing "Mr. Hubbard has reversed a time-honored formula and has given a thriller to which, at the end of every chapter or so, another paleface bites the dust."

On New Year's Day, 1938, Hubbard reportedly underwent a dental procedure and reacted to the anesthetic gas used in the procedure. According to his account, this triggered a revelatory near-death experience

A near-death experience (NDE) is a profound personal experience associated with death or impending death, which researchers describe as having similar characteristics. When positive, which the great majority are, such experiences may encompa ...

. Allegedly inspired by this experience, Hubbard composed a manuscript, which was never published, with working titles of ''The One Command'' and ''Excalibur''. Hubbard sent telegrams to several book publishers, but nobody bought the manuscript. Hubbard wrote to his wife:

Hubbard found greater success after being taken under the supervision of editor John W. Campbell

John Wood Campbell Jr. (June 8, 1910 – July 11, 1971) was an American science fiction writer and editor. He was editor of ''Astounding Science Fiction'' (later called ''Analog Science Fiction and Fact'') from late 1937 until his death and wa ...

, who published many of Hubbard's short stories and serialized novelettes in his magazines ''Unknown

Unknown or The Unknown may refer to:

Film and television Film

* The Unknown (1915 comedy film), ''The Unknown'' (1915 comedy film), Australian silent film

* The Unknown (1915 drama film), ''The Unknown'' (1915 drama film), American silent drama ...

'' and ''Astounding Science Fiction

''Analog Science Fiction and Fact'' is an American science fiction magazine published under various titles since 1930. Originally titled ''Astounding Stories of Super-Science'', the first issue was dated January 1930, published by William C ...

''. Hubbard's novel '' Final Blackout'' told the story of a low-ranking British army officer who rises to become dictator of the United Kingdom. In July 1940, Campbell magazine ''Unknown'' published a psychological horror by Hubbard titled ''Fear

Fear is an unpleasant emotion that arises in response to perception, perceived dangers or threats. Fear causes physiological and psychological changes. It may produce behavioral reactions such as mounting an aggressive response or fleeing the ...

'' about an ethnologist who becomes paranoid that demons are out to get him—the work was well-received, drawing praise from Ray Bradbury

Ray Douglas Bradbury ( ; August 22, 1920June 5, 2012) was an American author and screenwriter. One of the most celebrated 20th-century American writers, he worked in a variety of genres, including fantasy, science fiction, Horror fiction, horr ...

, Isaac Asimov

Isaac Asimov ( ; – April 6, 1992) was an Russian-born American writer and professor of biochemistry at Boston University. During his lifetime, Asimov was considered one of the "Big Three" science fiction writers, along with Robert A. H ...

, and others. In November and December 1940, ''Unknown'' serialized Hubbard's novel ''Typewriter in the Sky

''Typewriter in the Sky'' is a science fantasy novel by American writer L. Ron Hubbard. The protagonist Mike de Wolf finds himself inside the story of his friend Horace Hackett's book. He must survive conflict on the high seas in the Caribbean ...

'' about a pulp fiction writer whose friend becomes trapped inside one of his stories.

Military career

In 1941, Hubbard applied to join the

In 1941, Hubbard applied to join the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

. His application was accepted, and he was commissioned as a lieutenant junior grade

Lieutenant junior grade is a junior commissioned officer rank used in a number of navies.

United States

Lieutenant (junior grade), commonly abbreviated as LTJG or, historically, Lt. (j.g.) (as well as variants of both abbreviations), i ...

in the United States Naval Reserve

The United States Navy Reserve (USNR), known as the United States Naval Reserve from 1915 to 2004, is the Reserve Component (RC) of the United States Navy. Members of the Navy Reserve, called reservists, are categorized as being in either the S ...

on July 19, 1941. By November, he was posted to New York for training as an intelligence officer. The day after Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor is an American lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. It was often visited by the naval fleet of the United States, before it was acquired from the Hawaiian Kingdom by the U.S. with the signing of the Reci ...

, Hubbard was posted to the Philippines

The Philippines, officially the Republic of the Philippines, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic country in Southeast Asia. Located in the western Pacific Ocean, it consists of List of islands of the Philippines, 7,641 islands, with a tot ...

and departed the US bound for Australia. But while in Australia awaiting transport to the Philippines, Hubbard was suddenly ordered back to the United States after being accused by the US Naval Attaché to Australia of sending blockade-runner '' Don Isidro'' "three thousand miles out of her way".Ron The War Hero, Chris Owen

In June 1942, Hubbard was given command of a patrol boat at the Boston Navy Yard

The Boston Navy Yard, originally called the Charlestown Navy Yard and later Boston Naval Shipyard, was one of the oldest shipbuilding facilities in the United States Navy. It was established in 1801 as part of the recent establishment of t ...

, but he was relieved after the yard commandant wrote that Hubbard was "not temperamentally fitted for independent command". In 1943, Hubbard was given command of a submarine chaser, but only five hours into the shakedown cruise, Hubbard believed he had detected an enemy submarine. Hubbard and crew spent the next 68 hours engaged in combat. An investigation concluded that Hubbard had likely mistaken a "known magnetic deposit" for an enemy sub. The following month, Hubbard unwittingly fired upon Mexican territory and was relieved of command. In 1944, Hubbard served aboard the before being transferred. The night before his departure, Hubbard reported the discovery of an attempted sabotage.

In June 1942, Navy records indicate that Hubbard suffered "active conjunctivitis" and later "urethral discharges". After being relieved of command of the sub-chaser, Hubbard began reporting sick, citing a variety of ailments, including ulcers, malaria, and back pains. In July 1943, Hubbard was admitted to the San Diego naval hospital for observation—he would remain there for months. Years later, Hubbard would privately write to himself: "Your stomach trouble you used as an excuse to keep the Navy from punishing you." On April 9, 1945, Hubbard again reported sick and was re-admitted to Oak Knoll Naval Hospital

Naval Hospital Oakland, also known as Oak Knoll Naval Hospital, was a U.S. naval hospital located in Oakland, California that opened during World War II (1942) and closed in 1996 as part of the 1993 Base Realignment and Closure program. The si ...

, Oakland. He was discharged from the hospital on December 4, 1945.

After the war

After Hubbard chose to stay in California rather than return to his family in Washington state, he moved into thePasadena

Pasadena ( ) is a city in Los Angeles County, California, United States, northeast of downtown Los Angeles. It is the most populous city and the primary cultural center of the San Gabriel Valley. Old Pasadena is the city's original commercial d ...

mansion of John "Jack" Whiteside Parsons, a rocket propulsion engineer and a leading follower of the English occultist

The occult () is a category of esoteric or supernatural beliefs and practices which generally fall outside the scope of organized religion and science, encompassing phenomena involving a 'hidden' or 'secret' agency, such as magic and mystic ...

Aleister Crowley

Aleister Crowley ( ; born Edward Alexander Crowley; 12 October 1875 – 1 December 1947) was an English occultist, ceremonial magician, poet, novelist, mountaineer, and painter. He founded the religion of Thelema, identifying himself as the pr ...

. Hubbard befriended Parsons and soon became sexually involved with Parsons's 21-year-old girlfriend, Sara "Betty" Northrup. Hubbard and Parsons collaborated on "Babalon Working

Babalon (also known as the Scarlet Woman, Great Mother or Mother of Abominations) is a goddess found in the occult system of Thelema, which was established in 1904 with the writing of ''The Book of the Law'' by English author and occultist Al ...

", a sex magic

Sex magic (sometimes spelled sex magick) is any type of sexual activity used in magical, ritualistic or otherwise religious and spiritual pursuits. One practice of sex magic is using sexual arousal or orgasm with visualization of a desired r ...

ritual intended to summon an incarnation of Babalon

Babalon (also known as the Scarlet Woman, Great Mother or Mother of Abominations) is a goddess found in the occult system of Thelema, which was established in 1904 with the writing of ''The Book of the Law'' by English author and occultist A ...

, the supreme Goddess in Crowley's pantheon.

During this period, Hubbard authored a document which has been called the " Affirmations", a series of statements relating to various physical, sexual, psychological and social issues that he was encountering in his life. The Affirmations appear to have been intended to be used as a form of self-hypnosis with the intention of resolving the author's psychological problems and instilling a positive mental attitude.

Parsons, Hubbard and Sara invested nearly their entire savings — the vast majority contributed by Parsons and Sara — in a plan for Hubbard and Sara to buy yachts on the East Coast and sail them to the West Coast to sell. Hubbard had a different idea, writing to the U.S. Navy requesting permission to undertake a world cruise. Parsons attempted to recover his money by obtaining an injunction to prevent Hubbard and Sara leaving the country or disposing of the remnants of his assets, but ultimately only received a $2,900 promissory note from Hubbard. Parsons returned home "shattered" and was forced to sell his mansion.

On August 10, 1946, Hubbard married Sara, though he was still married to his first wife Polly. Hubbard resumed his fiction writing to supplement his small disability allowance. In August 1947, Hubbard returned to the pages of ''Astounding'' with a serialized novel "The End is Not Yet", about a young nuclear physicist who tries to stop a world takeover by building a new philosophical system. In October 1947, the magazine began serializing ''

On August 10, 1946, Hubbard married Sara, though he was still married to his first wife Polly. Hubbard resumed his fiction writing to supplement his small disability allowance. In August 1947, Hubbard returned to the pages of ''Astounding'' with a serialized novel "The End is Not Yet", about a young nuclear physicist who tries to stop a world takeover by building a new philosophical system. In October 1947, the magazine began serializing ''Ole Doc Methuselah

''Ole Doc Methuselah'' is a collection of science fiction short stories by American writer L. Ron Hubbard, published in 1970.

Contents

The stories follow the adventures of "Old Doc Methuselah" in a future where interstellar travel

Interstel ...

'', the first in a series about the "Soldiers of Light", supremely skilled, extremely long-lived physicians. In February and March 1950, Campbell's ''Astounding'' serialized the Hubbard novel '' To the Stars'' about a young engineer on an interstellar trading starship who learns that months aboard ship amounts to centuries on Earth, making the ship his only remaining home after his first voyage. During his time in California, Hubbard began acting as a sort of amateur stage hypnotist or "swami

Swami (; ; sometimes abbreviated sw.) in Hinduism is an honorific title given to an Asceticism#Hinduism, ascetic who has chosen the Sannyasa, path of renunciation (''sanyāsa''), or has been initiated into a religious monastic order of Vaishnavas ...

".

Hubbard repeatedly wrote to the Veterans Administration

The United States Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is a Cabinet-level executive branch department of the federal government charged with providing lifelong healthcare services to eligible military veterans at the 170 VA medical centers an ...

(VA) asking for an increase in his war pension. Finally, in October 1947, he wrote to request psychiatric treatment:

The VA eventually did increase his pension, but his money problems continued. In the summer of 1948, Hubbard was arrested by the San Luis Obispo sheriff on a charge of petty theft for passing a fraudulent check. Beginning in June 1948, the nationally-syndicated wire service United Press

United Press International (UPI) is an American international news agency whose newswires, photo, news film, and audio services provided news material to thousands of newspapers, magazines, radio and television stations for most of the 20th ...

ran a story on an American Legion-sponsored psychiatric ward in Savannah, Georgia, which sought to keep mentally-ill war veterans out of jail. In late 1948, Hubbard and his second wife Sara moved from California to Savannah, Georgia, where he would later claim to have worked as a volunteer in a psychiatric clinic. Hubbard claimed he had "processed an awful lot of Negroes" and wrote of having observed a psychiatrist using the threat of institutionalization in a state hospital to solicit funds from a patient's husband. In letters to friends sent from Savannah, Hubbard began to make the first public mentions of what was to become Dianetics.

In the Dianetics era

Inspired by science-fiction of his friendRobert Heinlein

Robert Anson Heinlein ( ; July 7, 1907 – May 8, 1988) was an American science fiction author, aeronautical engineer, and naval officer. Sometimes called the "dean of science fiction writers", he was among the first to emphasize scientific acc ...

, Hubbard announced plans to write a book which would claim to "make supermen". Hubbard announced to the public that there existed a superhuman condition which he called the state of " Clear". He claimed people in that state would have a perfectly functioning mind with an improved intelligence quotient

An intelligence quotient (IQ) is a total score derived from a set of standardized tests or subtests designed to assess human intelligence. Originally, IQ was a score obtained by dividing a person's mental age score, obtained by administering ...

(IQ) and photographic memory. The "Clear" would be cured of physical ailments ranging from poor eyesight to the common cold, which Hubbard asserted were purely psychosomatic

Somatic symptom disorder, also known as somatoform disorder or somatization disorder, is chronic somatization. One or more chronic physical symptoms coincide with excessive and maladaptive thoughts, emotions, and behaviors connected to those symp ...

.

To promote his upcoming book, Hubbard enlisted his longtime-editor John Campbell, who had a fascination with fringe psychologies and psychic powers. Campbell invited Hubbard and Sara to move into a New Jersey cottage. Campbell, in turn, recruited an acquaintance, medical doctor Joseph Winter, to help promote the book. Campbell wrote Winter to extol Hubbard, claiming that Hubbard had worked with nearly 1000 cases and cured every single one. The birth of Hubbard's second daughter Alexis Valerie, delivered by Winter on March 8, 1950, came in the middle of the preparations to launch Dianetics.

The basic content of Dianetics was a pseudoscientific

Pseudoscience consists of statements, beliefs, or practices that claim to be both scientific and factual but are incompatible with the scientific method. Pseudoscience is often characterized by contradictory, exaggerated or unfalsifiable cl ...

retelling of psychoanalytic theory geared for a mass market English-speaking audience. Like Freud, Hubbard wrote that the brain recorded memories (for Hubbard, "engrams") which were stored in the unconscious mind (which Hubbard restyled "the reactive mind

The reactive mind is a concept in Scientology formulated by L. Ron Hubbard, referring to that portion of the human mind that is unconscious and operates on stimulus-response, to which Hubbard attributed most mental, emotional, and psychosom ...

"). Past memories could be triggered later in life, causing psychological, emotional, or even physical problems. By sharing their memories with a friendly listener (or "auditor

An auditor is a person or a firm appointed by a company to execute an audit.Practical Auditing, Kul Narsingh Shrestha, 2012, Nabin Prakashan, Nepal To act as an auditor, a person should be certified by the regulatory authority of accounting an ...

"), a person could overcome their past pain and thus cure themselves. Through Dianetics, Hubbard claimed that most illnesses were psychosomatic and caused by engrams, including arthritis, dermatitis, allergies, asthma, coronary difficulties, eye trouble, bursitis, ulcers, sinusitis and migraine headaches. He further claimed that dianetic therapy could treat these illnesses, and also included cancer and diabetes as conditions that Dianetic research was focused on.

Accompanied by an article in ''Astounding's'' May 1950 issue, the pseudoscientific book '' Dianetics: The Modern Science of Mental Health'' was released on May 9. Although Dianetics was poorly received by the press and the scientific and medical professions, the book was an immediate commercial success and sparked "a nationwide cult of incredible proportions". Five hundred Dianetic auditing groups were set up across the United States,Staff (August 21, 1950). "Dianetics book review; Best Seller". ''Newsweek'' and Hubbard established the "Hubbard Dianetic Research Foundation". Financial controls were lax, and Hubbard himself took large sums with no explanation of what he was doing with it.

Dianetics lost public credibility on August 10 when a presentation by Hubbard before an audience of 6,000 at the

Accompanied by an article in ''Astounding's'' May 1950 issue, the pseudoscientific book '' Dianetics: The Modern Science of Mental Health'' was released on May 9. Although Dianetics was poorly received by the press and the scientific and medical professions, the book was an immediate commercial success and sparked "a nationwide cult of incredible proportions". Five hundred Dianetic auditing groups were set up across the United States,Staff (August 21, 1950). "Dianetics book review; Best Seller". ''Newsweek'' and Hubbard established the "Hubbard Dianetic Research Foundation". Financial controls were lax, and Hubbard himself took large sums with no explanation of what he was doing with it.

Dianetics lost public credibility on August 10 when a presentation by Hubbard before an audience of 6,000 at the Shrine Auditorium

The Shrine Auditorium is a landmark large-event venue in Los Angeles, California. It is also the headquarters of the Al Malaikah Temple, a division of the Shriners. It was designated a Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument (No. 139) in 1975, an ...

in Los Angeles failed disastrously. He introduced a woman named Sonya Bianca and told the audience that as a result of undergoing Dianetic therapy she now possessed perfect recall, only for her to forget the color of Hubbard's necktie. A large part of the audience walked out, and the debacle was publicized by popular science writer Martin Gardner

Martin Gardner (October 21, 1914May 22, 2010) was an American popular mathematics and popular science writer with interests also encompassing magic, scientific skepticism, micromagic, philosophy, religion, and literatureespecially the writin ...

. On September 3, psychologist Erich Fromm

Erich Seligmann Fromm (; ; March 23, 1900 – March 18, 1980) was a German-American social psychologist, psychoanalyst, sociologist, humanistic philosopher, and democratic socialist. He was a German Jew who fled the Nazi regime and set ...

publicly derided ''Dianetics'' as a "mixture of some oversimplified truths, half truths and plain absurdities"; Fromm criticized the writing as "propagandistic" and likened it to the quack field of patent medicines. By late-1950, Hubbard's foundations were in financial crisis. Hubbard's publisher Arthur Ceppos, his longtime promoter Joseph Campbell, and medical doctor-turned-Dianetics endorser Joseph Winter all resigned under acrimonious circumstances.

In late-1950, Hubbard began an affair with employee Barbara Klowden, prompting Sara to start her own affair with Miles Hollister. On February 23, 1951, Sara and her lover consulted with a psychiatrist about Hubbard, who advised that Sara was in grave danger and Hubbard should be institutionalized. The trio telephoned Jack Maloney, the head of the Hubbard's foundation in Elizabeth, New Jersey

Elizabeth is a City (New Jersey), city in and the county seat of Union County, New Jersey, Union County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey.Cuba

Cuba, officially the Republic of Cuba, is an island country, comprising the island of Cuba (largest island), Isla de la Juventud, and List of islands of Cuba, 4,195 islands, islets and cays surrounding the main island. It is located where the ...

. Hubbard denounced Sara and her lover to the FBI

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic Intelligence agency, intelligence and Security agency, security service of the United States and Federal law enforcement in the United States, its principal federal law enforcement ag ...

, portraying them in a letter as communist

Communism () is a sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology within the socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a socioeconomic order centered on common ownership of the means of production, di ...

infiltrators. An agent annotated his correspondence with Hubbard with the comment, "Appears mental".

On April 12, Sara's story was published in the press, leading to headlines such as "Ron Hubbard Insane, Says His Wife". Hubbard's first wife evidently saw the headlines and wrote to Sara on May 2 offering her support. "Ron is not normal... Your charges probably sound fantastic to the average person—but I've been through it—the beatings, threats on my life, all the sadistic traits you charge—twelve years of it." In June, Sara finally secured the return of her daughter by agreeing to a settlement in which she signed a statement, written by Hubbard, declaring that she had been misrepresented in the press and that she had always believed he was a "fine and brilliant man".

The Dianetics craze "burned itself out as quickly as it caught fire", and the movement appeared to be on the edge of total collapse. However, it was temporarily saved by Don Purcell, a millionaire who agreed to support a new Foundation in Wichita, Kansas

Wichita ( ) is the List of cities in Kansas, most populous city in the U.S. state of Kansas and the county seat of Sedgwick County, Kansas, Sedgwick County. As of the 2020 United States census, 2020 census, the population of the city was 397, ...

. In August 1951, Hubbard published ''Science of Survival

''Science of Survival'' is a 1951 pseudoscientific book by L. Ron Hubbard which continues to be published by the Church of Scientology as part of Scientology's canon. According to Jon Atack, the title ''Science of Survival'' was chosen "to ap ...

''. In that book, Hubbard introduced such concepts as the immortal soul (or "Thetan") and past-life regressions (or "Whole Track Auditing"). The Wichita Foundation underwrote the costs of printing the book, but it recorded poor sales when first published, with only 1,250 copies of the first edition being printed. The Wichita Foundation became financially nonviable after a court ruled that it was liable for the unpaid debts of its defunct predecessor in Elizabeth, New Jersey

Elizabeth is a City (New Jersey), city in and the county seat of Union County, New Jersey, Union County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey.American Medical Association

The American Medical Association (AMA) is an American professional association and lobbying group of physicians and medical students. This medical association was founded in 1847 and is headquartered in Chicago, Illinois. Membership was 271,660 ...

to destroy Dianetics. Hubbard emptied the Wichita foundation's bank accounts, in part through forgery.

Pivot to Scientology

Having lost the rights to Dianetics, Hubbard created Scientology. At a convention in Wichita, Hubbard announced that he had discovered a new science beyond Dianetics which he called "Scientology". Whereas the goal of Dianetics had been to reach a superhuman state of "Clear", Scientology promised a chance to achieve god-like powers in a state calledOperating Thetan

In Scientology, Operating Thetan (OT) is a state of complete spiritual freedom in which one is a "willing and knowing cause over life, thought, matter, energy, space and time". The Church of Scientology offers eight "levels" of OT, each level cos ...

. Hubbard introduced a device called an "electropsychometer" (or e-meter

The E-Meter (also electropsychometer and Hubbard Electrometer) is an electronic device used in Scientology that allegedly "registers emotional reactions". After claims by L. Ron Hubbard that the procedures of Auditing (Scientology), auditing, w ...

), which called for users to hold two metal cans in their hands to measure changes in skin conductivity due to variance in sweat or grip. In 1906, Swiss psychoanalyst Carl Jung

Carl Gustav Jung ( ; ; 26 July 1875 – 6 June 1961) was a Swiss psychiatrist, psychotherapist, and psychologist who founded the school of analytical psychology. A prolific author of Carl Jung publications, over 20 books, illustrator, and corr ...

had famously used such a device in a study of word association. Rather than a mundane biofeedback device, Hubbard presented the e-meter as having "an almost mystical power to reveal an individual's innermost thoughts".

Hubbard married a staff member, 20-year-old Mary Sue Whipp, and the pair moved to Phoenix, Arizona

Phoenix ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of cities and towns in Arizona#List of cities and towns, most populous city of the U.S. state of Arizona. With over 1.6 million residents at the 2020 census, it is the ...

. Hubbard was joined by his 18-year-old son Nibs, who had become a Scientology staff member and "professor". Scientology was organized in a different way from the decentralized Dianetics movement — The Hubbard Association of Scientologists (HAS) was the only official Scientology organization. Branches or "orgs" were organized as franchises, rather like a fast food restaurant

A fast-food restaurant, also known as a quick-service restaurant (QSR) within the industry, is a specific type of restaurant that serves fast food, fast-food cuisine and has minimal Foodservice#Table service, table service. The food served ...

chain. Each franchise holder was required to pay ten percent of income to Hubbard's central organization. In July, Hubbard published "What to Audit" (later re-titled '' Scientology: A History of Man''), which taught everyone has subconscious traumatic memories of their past lives as clams, sloths, and cavemen which cause neuroses and health problems. In November 1952, Hubbard published ''Scientology 8-80'', followed up in December with ''Scientology 8-8008'', which argued that the physical universe is the creation of the mind.

In December, Hubbard gave a seventy-hour series of lectures in Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

that was attended by 38 people in which he delved into the occult

''The Occult: A History'' is a 1971 nonfiction occult book by English writer, Colin Wilson. Topics covered include Aleister Crowley, George Gurdjieff, Helena Blavatsky, Kabbalah, primitive magic, Franz Mesmer, Grigori Rasputin, Daniel Dunglas H ...

. In the lectures, Hubbard connects rituals and the practice of Scientology to the magick

Ceremonial magic (also known as magick, ritual magic, high magic or learned magic) encompasses a wide variety of rituals of Magic (supernatural), magic. The works included are characterized by ceremony and numerous requisite accessories t ...

al practices of Aleister Crowley

Aleister Crowley ( ; born Edward Alexander Crowley; 12 October 1875 – 1 December 1947) was an English occultist, ceremonial magician, poet, novelist, mountaineer, and painter. He founded the religion of Thelema, identifying himself as the pr ...

, recommending Crowley's book '' The Master Therion''. During the Philadelphia course, Hubbard joked that he was "the prince of darkness", which was met with laughter from the audience. On December 16, 1952, Hubbard was arrested in the middle of a lecture for failing to return $9,000 withdrawn from the Wichita Foundation. He eventually settled the debt by paying $1,000 and returning a car belonging to Wichita financier Don Purcell.

In April 1953, Hubbard proposed setting up a chain of "Spiritual Guidance Centers" as part of what he called "the religion angle". On December 18, 1953, Hubbard incorporated the Church of Scientology in Camden, New Jersey

Camden is a City (New Jersey), city in Camden County, New Jersey, Camden County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey. It is part of the Delaware Valley metropolitan region. The city was incorporated on February 13, 1828.Snyder, John P''The Story of ...

.Williams, Ian. ''The Alms Trade: Charities, Past, Present and Future'', p. 127. New York: Cosimo, 2007. The religious transformation was explained as a way to protect Scientologists from charges of practicing medicine without a license. The idea may not have been new; Hubbard has been quoted as telling a science fiction convention in 1948: "Writing for a penny a word is ridiculous. If a man really wants to make a million dollars, the best way would be to start his own religion."Methvin, Eugene H. (May 1990). "Scientology: Anatomy of a Frightening Cult". ''Reader's Digest

''Reader's Digest'' is an American general-interest family magazine, published ten times a year. Formerly based in Chappaqua, New York, it is now headquartered in midtown Manhattan. The magazine was founded in 1922 by DeWitt Wallace and his wi ...

''. p. 16.

In the Church of Scientology era

By 1954, the IRS recognized the Church of Scientology of California as a tax-exempt organization and by 1966, the Washington, D.C. Founding Church of Scientology received tax-exempt status nationwide. The Church of Scientology became a highly profitable enterprise for Hubbard, as he was paid a percentage of the Church's gross income. By 1957 he was being paid about $250,000 per year (equivalent to $ million in ). His family grew, too, with Mary Sue giving birth to three more children—Quentin

Quentin is a French masculine given name derived from the Latin first name ''Quintinus'', a diminutive form of ''Quintus'', which means "the fifth". Albert Dauzat, ''Noms et prénoms de France'', Librairie Larousse 1980, édition revue et comment� ...

on January 6, 1954; Suzette on February 13, 1955; and Arthur on June 6, 1958.

Hubbard was notorious for his policies of attacking his perceived enemies. Nibs recalled that Hubbard "only knew how to do one thing and that was to destroy people." Hubbard told Scientologists to "Don't ever defend, always attack", encouraging them to find or manufacture evidence and to file harassing lawsuits against enemies. Any individual breaking away from Scientology and setting up his own group was to be shut down. Most of the formerly independent Scientology and Dianetics groups were either driven out of business or were absorbed into Hubbard's organizations. Hubbard finally achieved victory over Don Purcell in 1954 when the latter, worn out by constant litigation, handed the copyrights of Dianetics back to Hubbard.

After dealing with Purcell, Hubbard turned his attention to attacking psychiatrists, who he blamed for the backlash against Dianetics and Scientology. In 1955, Hubbard authored a text titled: '' Brain-Washing: A Synthesis of the Russian Textbook on Psychopolitics'' which purported to be a secret manual linking Psychiatry and Communism written by a Soviet secret police

There were a succession of Soviet secret police agencies over time. The Okhrana was abolished by the Provisional government after the first revolution of 1917, and the first secret police after the October Revolution, created by Vladimir Leni ...

chief. Hubbard founded the "National Academy of American Psychology" which sought to issue a "loyalty oath" to psychologists and psychiatrists. Those who opposed the oath were to be labeled "Subversive psychiatrists", while those who merely refused to sign the oath would be labeled "Potentially Subversive". Hubbard denounced psychiatric abuses, writing that psychoanalysis had been "superseded by tyrannous sadism, practiced by unprincipled men". Wrote Hubbard:

Today men who call themselves analysts are merrily sawing out patients' brains, shocking them with murderous drugs, striking them with high voltages, burying them underneath mounds of ice, placing them in restraints, 'sterilizing' them sexually and generally conducting themselves much as their patients would were they given the chance.In 1956, Hubbard released '' Fundamentals of Thought'', which teaches that life is a game and divides people into pieces, players, and game-makers. The following year, Hubbard published ''

All About Radiation

''All About Radiation'' is a pseudoscientific book by L. Ron Hubbard on the subject of radiation and atomic bombs, and the effects on the human body, including techniques for reducing or eradicating those effects. It was first published in 1957 ...

'', which falsely claimed that radiation poisoning and even cancer can be cured by vitamins. In 1958, amid widespread interest in the Bridey Murphy

Bridey Murphy (December 20, 1798 – 1864) is a purported 19th-century Irishwoman whom U.S. housewife Virginia Tighe (April 27, 1923 – July 12, 1995) claimed to be in a past life. The case was investigated by researchers and determined to be the ...

case, Hubbard authored ''Have You Lived Before This Life?

''Have You Lived Before This Life?'' is a pseudoscientific book about past lives by L. Ron Hubbard published in 1958 by the Hubbard Association of Scientologists International. The book is considered part of Scientology's canon.

Premise

The b ...

'', a collection of past life regression

Past life regression (PLR), Past life therapy (PLT), regression or memory regression is a method that uses hypnosis to recover what practitioners believe are Past life memory, memories of past lives or reincarnation, incarnations.Internal Revenue Service

The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) is the revenue service for the Federal government of the United States, United States federal government, which is responsible for collecting Taxation in the United States, U.S. federal taxes and administerin ...

withdrew the Washington, D.C., Church of Scientology's tax exemption

Tax exemption is the reduction or removal of a liability to make a compulsory payment that would otherwise be imposed by a ruling power upon persons, property, income, or transactions. Tax-exempt status may provide complete relief from taxes, redu ...

after it found that Hubbard and his family were profiting unreasonably from Scientology's ostensibly non-profit income. In the spring of 1959, Hubbard purchased Saint Hill Manor

Saint Hill Manor is a Grade II listed country house at Saint Hill Green, near East Grinstead in West Sussex, England. It was constructed in 1792 and had several notable owners before being purchased by L. Ron Hubbard and becoming the British he ...

, an 18th-century English country house

image:Blenheim - Blenheim Palace - 20210417125239.jpg, 300px, Blenheim Palace - Oxfordshire

An English country house is a large house or mansion in the English countryside. Such houses were often owned by individuals who also owned a Townhou ...

formerly owned by the Maharaja of Jaipur

Maharaja (also spelled Maharajah or Maharaj; ; feminine: Maharani) is a royal title in Indian subcontinent of Sanskrit origin. In modern India and medieval northern India, the title was equivalent to a prince. However, in late ancient India ...

. The house became Hubbard's permanent residence and an international training center for Scientologists.

That year Hubbard learned his son Nibs had resigned from the organization, citing financial difficulties. Hubbard regarded the departure as a betrayal. Hubbard introduced " security checking", a structured interrogation using the e-meter, to identify those he termed " potential trouble sources" and " suppressive persons". Members of the Church of Scientology were interrogated with the aid of E-meters and were asked questions such as "Have you ever practiced homosexuality?" and "Have you ever had unkind thoughts about L. Ron Hubbard?"

Since its inception, Hubbard marketed Dianetics and Scientology through false medical claims. On January 4, 1963, US Food and Drug Administration

The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA or US FDA) is a List of United States federal agencies, federal agency of the United States Department of Health and Human Services, Department of Health and Human Services. The FDA is respo ...

agents raided American offices of the Church of Scientology, seizing over a hundred E-meters as illegal medical device

A medical device is any device intended to be used for medical purposes. Significant potential for hazards are inherent when using a device for medical purposes and thus medical devices must be proved safe and effective with reasonable assura ...

s, thousands of pills being marketed as "radiation cures", and tons of literature that they accused of making false medical claims.

In November 1963 Victoria, Australia

Victoria, commonly abbreviated as Vic, is a state in southeastern Australia. It is the second-smallest state (after Tasmania), with a land area of ; the second-most-populated state (after New South Wales), with a population of over 7 million; ...

, the government opened an inquiry into the Church, which was accused of brainwashing

Brainwashing is the controversial idea that the human mind can be altered or controlled against a person's will by manipulative psychological techniques. Brainwashing is said to reduce its subject's ability to think critically or independently ...

, blackmail, extortion and damaging the mental health of its members. Its report, published in October 1965, condemned every aspect of Scientology and Hubbard himself. The report led to Scientology being banned in Victoria, Western Australia

Western Australia (WA) is the westernmost state of Australia. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to the south, the Northern Territory to the north-east, and South Australia to the south-east. Western Aust ...

and South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a States and territories of Australia, state in the southern central part of Australia. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories by area, which in ...

, and led to more negative publicity around the world. Public perceptions of Scientology changed from "relatively harmless, if cranky" to an "evil, dangerous" group that performs hypnosis and brainwashing. Scientology attracted increasingly unfavorable publicity across the English-speaking world.

Hubbard took major new initiatives in the face of these challenges. By 1965, "Ethics Technology" was introduced to tighten internal discipline within Scientology. It required Scientologists to " disconnect" from any organization or individual—including family members—deemed to be disruptive or "suppressive". Scientologists were also required to write "Knowledge Reports" on each other, reporting transgressions or misapplications of Scientology methods. Hubbard promulgated a long list of punishable "Misdemeanors", "Crimes", and "High Crimes". At the start of March 1966, Hubbard created the Guardian's Office (GO), a new agency within the Church of Scientology that was headed by his wife Mary Sue. It dealt with Scientology's external affairs, including public relations, legal actions and the gathering of intelligence on perceived threats.

As Scientology faced increasingly negative media attention, the GO retaliated with hundreds of writs for libel and slander; it issued more than forty on a single day. Hubbard ordered his staff to find "lurid, blood sex crime actual evidence on cientology'sattackers". The "fair game

Fair Game may refer to:

Film

* ''Fair Game'' (1928 film), a German silent drama film

* ''Fair Game'' (1986 film), an Australian action film

* ''Fair Game'' (1988 film), an Italian thriller-horror film

* ''Fair Game'', a 1994 television film sta ...

" policy was codified in 1967, which was applicable to anyone deemed an "enemy" of Scientology: "May be deprived of property or injured by any means by any Scientologist without any discipline of the Scientologist. May be tricked, sued or lied to or destroyed."

Newspapers and politicians in the UK pressed the British government for action against Scientology. In April 1966, hoping to form a remote "safe haven" for Scientology, Hubbard traveled to the southern African country Rhodesia

Rhodesia ( , ; ), officially the Republic of Rhodesia from 1970, was an unrecognised state, unrecognised state in Southern Africa that existed from 1965 to 1979. Rhodesia served as the ''de facto'' Succession of states, successor state to the ...

(now Zimbabwe

file:Zimbabwe, relief map.jpg, upright=1.22, Zimbabwe, relief map

Zimbabwe, officially the Republic of Zimbabwe, is a landlocked country in Southeast Africa, between the Zambezi and Limpopo Rivers, bordered by South Africa to the south, Bots ...

). Despite his attempts to curry favor with the local government, Rhodesia promptly refused to renew Hubbard's visa, compelling him to leave the country. Finally, at the end of 1966, Hubbard acquired his own fleet of three ships. In July 1968, the British Minister of Health

A health minister is the member of a country's government typically responsible for protecting and promoting public health and providing welfare spending and other social security services.

Some governments have separate ministers for mental heal ...

announced that foreign Scientologists would no longer be permitted to enter the UK and Hubbard himself was excluded from the country as an " undesirable alien". Further inquiries were launched in Canada, New Zealand and South Africa.

In the Sea Org era

Hubbard purchased a ship inLas Palmas

Las Palmas (, ; ), officially Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, is a Spanish city and capital of Gran Canaria, in the Canary Islands, in the Atlantic Ocean.

It is the capital city of the Canary Islands (jointly with Santa Cruz de Tenerife) and the m ...

and founded the "Sea Org

The Sea Organization or Sea Org is the senior-most status of staff within the Church of Scientology network of corporations, but is not itself incorporated. In the 1960s and 1970s, the Sea Org was started as L. Ron Hubbard's private navy, and ...

", a private navy of elite Scientologists. Hubbard set out to take command of the ship. Enroute, he wrote OT III, the esoteric story of Xenu. In a letter to his wife Mary Sue

A Mary Sue is a type of fictional character, usually a young woman, who is portrayed as free of weaknesses or character flaws. The character type has acquired a pejorative reputation in fan communities, with the label "Mary Sue" often applie ...

, Hubbard said that, in order to assist his research, he was drinking alcohol and taking stimulant

Stimulants (also known as central nervous system stimulants, or psychostimulants, or colloquially as uppers) are a class of drugs that increase alertness. They are used for various purposes, such as enhancing attention, motivation, cognition, ...

s and depressant

Depressants, also known as central nervous system depressants, or colloquially known as "downers", are drugs that lower neurotransmission levels, decrease the electrical activity of brain cells, or reduce arousal or stimulation in various ...

s. In OT III, Hubbard wrote of alleged secrets of an immense disaster that had occurred "on this planet, and on the other seventy-five planets which form this Confederacy, seventy-five million years ago". It teaches that Xenu, the leader of the Galactic Confederacy, had shipped billions of people to Earth and blown them up with hydrogen bomb

A thermonuclear weapon, fusion weapon or hydrogen bomb (H-bomb) is a second-generation nuclear weapon design. Its greater sophistication affords it vastly greater destructive power than first-generation nuclear bombs, a more compact size, a lo ...

s, following which their traumatized spirits were stuck together at "implant stations", brainwashed with false memories and eventually became contained within human beings.

When Hubbard established the Sea Org he publicly declared that he had relinquished his management responsibilities over the Church of Scientology. In fact, he received daily telex

Telex is a telecommunication

Telecommunication, often used in its plural form or abbreviated as telecom, is the transmission of information over a distance using electronic means, typically through cables, radio waves, or other communica ...

messages from Scientology organizations around the world reporting their statistics and income. The Church of Scientology sent him $15,000 a week () along with millions of dollars that were transferred to bank accounts. Church of Scientology couriers arrived regularly, conveying luxury food for Hubbard and his family or cash that had been smuggled from England to avoid currency export restrictions. Hubbard's fleet began sailing from port to port in the Mediterranean Sea and eastern North Atlantic, rarely staying anywhere for longer than six weeks, as Hubbard claimed he was being pursued by enemies whose interference could lead to global chaos or nuclear war.Quoted in Miller 1987, p. 297

Though Scientologists around the world were presented with a glamorous picture of life in the Sea Org and many applied to join Hubbard aboard the fleet, the reality was rather different. Most of those joining had no nautical experience at all. Mechanical difficulties and blunders by the crews led to a series of embarrassing incidents and near-disasters. Following one incident in which the rudder of the ''Royal Scotman'' was damaged during a storm, Hubbard ordered the ship's entire crew to be reduced to a "condition of liability" and wear gray rags tied to their arms. The ship itself was treated the same way, with dirty tarpaulins tied around its funnel to symbolize its lower status. According to those aboard, conditions were appalling; the crew was worked to the point of exhaustion, given meager rations and forbidden to wash or change their clothes for several weeks. Hubbard maintained a harsh disciplinary regime aboard the fleet, punishing mistakes by confining people in the ''Royal Scotman'' bilge tanks without toilet facilities and with food provided in buckets. At other times erring crew members or students were thrown overboard with Hubbard looking on and, occasionally, filming. One member of the Sea Org recalled Hubbard punishing a little boy by confining him to the ship's chain locker.

Aboard ship, Hubbard began dispatching teams of Sea Org members to search for historic evidence of his past lives; In 1973, he published ''Mission into Time'' about those searches.Hubbard, L. Ron. ''Mission into Time'', p. 7. Copenhagen: AOSH DK Publications Department A/S, 1973. Now having his own paramilitary force, orders to use R2-45 (killing someone with a .45 pistol) on specific individuals were published. From about 1970, Hubbard was attended aboard ship by the children of Sea Org members, organized as the Commodore's Messenger Organization (CMO). They were mainly young girls dressed in hot pants

Hotpants or hot pants are extremely short shorts. The term was first used by ''Women's Wear Daily'' in 1970 to describe shorts made in luxury fabrics such as velvet and satin for fashionable wear, rather than their more practical equivalents t ...

and halter top

Halterneck is a style of women's clothing strap that runs from the front of the garment around the back of the neck, generally leaving the upper back uncovered. The name comes from livestock halters. The word "halter" is of Germanic origin and me ...

s, who were responsible for running errands for Hubbard such as lighting his cigarettes, dressing him or relaying his verbal commands to other members of the crew. In addition to his wife Mary Sue, he was accompanied by all four of his children by her, who were all members of the Sea Org and shared its rigors.

After his prior failure in Rhodesia, Hubbard again tried to establish a safe haven in a friendly country, this time Greece. The fleet stayed at the Greek island of Corfu

Corfu ( , ) or Kerkyra (, ) is a Greece, Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands; including its Greek islands, small satellite islands, it forms the margin of Greece's northwestern frontier. The island is part of the Corfu (regio ...

for several months in 1968–1969. Hubbard, recently expelled from Britain, renamed the ships after Greek gods—the ''Royal Scotman

HMS ''Royal Scotsman'', originally the MV ''Royal Scotsman'', was an LSI of the British Royal Navy that served during World War II. A former passenger ferry, she saw action in the Mediterranean during the invasions of North Africa (Operation To ...

'' was rechristened ''Apollo''—and he praised the recently established military dictatorship. Despite Hubbard's hopes, in March 1969 Hubbard and his ships were ordered to leave.

The practice of prominently displaying the cross in Scientology centers was instituted in 1969 following hostile press coverage where Scientology's status as a legitimate religion was being questioned. In October 1969, ''

The practice of prominently displaying the cross in Scientology centers was instituted in 1969 following hostile press coverage where Scientology's status as a legitimate religion was being questioned. In October 1969, ''The Sunday Times

''The Sunday Times'' is a British Sunday newspaper whose circulation makes it the largest in Britain's quality press market category. It was founded in 1821 as ''The New Observer''. It is published by Times Newspapers Ltd, a subsidiary of N ...

'' published an exposé by Australian journalist Alex Mitchell detailing Hubbard's occult experiences with Parsons and Aleister Crowley's teachings. The Church responded with a statement, claiming without evidence Hubbard was sent in by the US Government to "break up Black Magic in America" and succeeded.

In mid-1972, Hubbard again tried to find a safe haven, this time in Morocco

Morocco, officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is a country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It has coastlines on the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria to Algeria–Morocc ...

, establishing contacts with the country's secret police

image:Putin-Stasi-Ausweis.png, 300px, Vladimir Putin's secret police identity card, issued by the East German Stasi while he was working as a Soviet KGB liaison officer from 1985 to 1989. Both organizations used similar forms of repression.

Secre ...

and training senior policemen and intelligence agents in techniques for detecting subversives. The program ended in failure when it became caught up in internal Moroccan politics, and Hubbard left the country hastily in December 1972. After French prosecutors charged Hubbard with fraud and customs violations, Hubbard risked extradition to France. In response, at the end of 1972, Hubbard left the Sea Org fleet temporarily, living incognito in Queens

Queens is the largest by area of the Boroughs of New York City, five boroughs of New York City, coextensive with Queens County, in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. Located near the western end of Long Island, it is bordered by the ...

, New York. Hubbard's health deteriorated significantly during this period, as he was an overweight chain-smoker, suffered from bursitis

Bursitis is the inflammation of one or more bursae (synovial sacs) of synovial fluid in the body. They are lined with a synovial membrane that secretes a lubricating synovial fluid. There are more than 150 bursae in the human body. The bursae (bu ...

and had a prominent growth on his forehead. In September 1973 when the threat of extradition had abated, Hubbard left New York, returning to his flagship.

Hubbard suffered serious injuries in a motorcycle accident on the island of Tenerife

Tenerife ( ; ; formerly spelled ''Teneriffe'') is the largest and most populous island of the Canary Islands, an Autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Spain. With a land area of and a population of 965,575 inhabitants as of A ...

in December 1973. In 1974, Hubbard established the Rehabilitation Project Force

The Rehabilitation Project Force, or RPF, is the Church of Scientology's program for members of its Sea Organization who have allegedly violated expectations or policies. This may include members who are deemed to have hidden evil intentions ...

, a punishment program for Sea Org members who displeased him. Hubbard's son Quentin reportedly found it difficult to adjust and attempted suicide in mid-1974. Also in 1974, L. Ron Hubbard confessed to two top executives that "People do not eave Scientologybecause of heir unconfessed sins they leave because hey stop liking Scientology or stop believing in it. Hubbard warned "If any of this information ever became public, I would lose all control of the orgs and eventually Scientology as a whole."

Better Business Bureau

The Better Business Bureau (BBB) is an American private, 501(c)(6) nonprofit organization founded in 1912. BBB's self-described mission is to focus on advancing marketplace trust, consisting of 92 independently incorporated local BBB organizati ...

, American Medical Association

The American Medical Association (AMA) is an American professional association and lobbying group of physicians and medical students. This medical association was founded in 1847 and is headquartered in Chicago, Illinois. Membership was 271,660 ...

, American Psychiatric Association

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) is the main professional organization of psychiatrists and trainee psychiatrists in the United States, and the largest psychiatric organization in the world. It has more than 39,200 members who are in ...

, U.S. Department of Justice