Kyiv Offensive (1920) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The 1920 Kiev offensive (or Kiev expedition, ) was a major part of the

By late autumn 1919, many Polish activists from different political formations concluded that Poland, generally successful in pushing the

By late autumn 1919, many Polish activists from different political formations concluded that Poland, generally successful in pushing the

The government of the

The government of the

Polish–Soviet War

The Polish–Soviet War (14 February 1919 – 18 March 1921) was fought primarily between the Second Polish Republic and the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, following World War I and the Russian Revolution.

After the collapse ...

. It was an attempt by the armed forces of the recently established Second Polish Republic

The Second Polish Republic, at the time officially known as the Republic of Poland, was a country in Central and Eastern Europe that existed between 7 October 1918 and 6 October 1939. The state was established in the final stage of World War I ...

led by Józef Piłsudski

Józef Klemens Piłsudski (; 5 December 1867 – 12 May 1935) was a Polish statesman who served as the Chief of State (Poland), Chief of State (1918–1922) and first Marshal of Poland (from 1920). In the aftermath of World War I, he beca ...

, in alliance with the Ukrainian People's Republic

The Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR) was a short-lived state in Eastern Europe. Prior to its proclamation, the Central Council of Ukraine was elected in March 1917 Ukraine after the Russian Revolution, as a result of the February Revolution, ...

led by Symon Petliura, to seize the territories of modern-day Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

which mostly fell under Soviet control after the October Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

as the Russian Soviet Republic

The Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (Russian SFSR or RSFSR), previously known as the Russian Socialist Federative Soviet Republic and the Russian Soviet Republic, and unofficially as Soviet Russia,Declaration of Rights of the labo ...

Polish and Soviet forces fought in 1919 and the Poles advanced in the disputed borderlands. In early 1920, Piłsudski concentrated on preparations for a military invasion of central Ukraine. It would result, he anticipated, in destruction of the Soviet armies and force Soviet acceptance of unilateral Polish conditions. The Poles signed an alliance, known as the Treaty of Warsaw, with the forces

In physics, a force is an influence that can cause an object to change its velocity unless counterbalanced by other forces. In mechanics, force makes ideas like 'pushing' or 'pulling' mathematically precise. Because the magnitude and directi ...

of the Ukrainian People's Republic. The Kiev offensive was the central component of Piłsudski's plan for a new order in Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the Europe, European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural and socio-economic connotations. Its eastern boundary is marked by the Ural Mountain ...

centered around a Polish-led Intermarium

Intermarium (, ) was a post-World War I geopolitical plan conceived by Józef Piłsudski to unite former Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth lands within a single polity. The plan went through several iterations, some of which anticipated the inclusi ...

federation. The stated goal of the operation was to create a formally independent Ukraine, although its dependence on Poland was inherent to Piłsudski's plans. Ukrainians

Ukrainians (, ) are an East Slavs, East Slavic ethnic group native to Ukraine. Their native tongue is Ukrainian language, Ukrainian, and the majority adhere to Eastern Orthodox Church, Eastern Orthodoxy, forming the List of contemporary eth ...

ended up fighting on both sides of the conflict.

The campaign was conducted from April to July 1920. The Polish Army

The Land Forces () are the Army, land forces of the Polish Armed Forces. They currently contain some 110,000 active personnel and form many components of the European Union and NATO deployments around the world. Poland's recorded military histor ...

faced the forces of the Russian Soviet Republic. At first, the war was successful for the allied Polish and Ukrainian armies, which captured Kiev

Kyiv, also Kiev, is the capital and most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city of Ukraine. Located in the north-central part of the country, it straddles both sides of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2022, its population was 2, ...

(Kyiv) on 7 May 1920, but soon the campaign's progress was dramatically reversed due to a Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

counter-offensive, in which the 1st Cavalry Army

__NOTOC__

The 1st Cavalry Army (), or ''Konarmia'' (Кона́рмия, "Horsearmy"), was a prominent Red Army military formation that served in the Russian Civil War and Polish–Soviet War, Polish-Soviet War.

History

Formation

On 17 Novem ...

of Semyon Budyonny

Semyon Mikhailovich Budyonny ( rus, Семён Миха́йлович Будённый, Semyon Mikháylovich Budyonnyy, p=sʲɪˈmʲɵn mʲɪˈxajləvʲɪdʑ bʊˈdʲɵnːɨj, a=ru-Simeon Budyonniy.ogg; – 26 October 1973) was a Russian and ...

played a prominent part. In the wake of the Soviet advance, the short-lived Galician Soviet Socialist Republic was created. The Polish-Soviet War ended with the Peace of Riga

The Treaty of Riga was signed in Riga, Latvia, on between Poland on one side and Soviet Russia (acting also on behalf of Soviet Belarus) and Soviet Ukraine on the other, ending the Polish–Soviet War (1919–1921). The chief negotiators o ...

of 1921, which settled the border between Poland and the Russian Soviet Republic.

Background

By late autumn 1919, many Polish activists from different political formations concluded that Poland, generally successful in pushing the

By late autumn 1919, many Polish activists from different political formations concluded that Poland, generally successful in pushing the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

forces to the east and gaining territory there, should now pursue peace by negotiating with Soviet Russia. The authorities increasingly had to deal with public protests and anti-war demonstrations. The Soviets also faced pressures to negotiate resolutions to the regional conflicts they were involved in. They launched diplomatic initiatives aimed at the eastern Baltic region

The Baltic Sea Region, alternatively the Baltic Rim countries (or simply the Baltic Rim), and the Baltic Sea countries/states, refers to the general area surrounding the Baltic Sea, including parts of Northern, Central and Eastern Europe. Un ...

states and Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

, which eventually resulted in treaties and improved relations.

Soviet Russia had not given up its mission of establishing a European Soviet Republic, but its leaders felt now that their goal could be accomplished at some time in the future, not necessarily immediate. They decided that peace with Poland would be desirable and on 22 December 1919, People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs Georgy Chicherin sent Warsaw

Warsaw, officially the Capital City of Warsaw, is the capital and List of cities and towns in Poland, largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the Vistula, River Vistula in east-central Poland. Its population is officially estimated at ...

the first of several peace offers. For the time being, the Soviets proposed a demarcation line at the current military frontiers, leaving permanent border issues to future determinations.

Some Polish politicians, including a majority on the Foreign and Military Affairs Committee of Polish parliament

The parliament of Poland is the Bicameralism, bicameral legislature of Poland. It is composed of an upper house (the Senate of Poland, Senate) and a lower house (the Sejm). Both houses are accommodated in the Sejm and Senate Complex of Poland, S ...

, insisted on negotiating with the Soviets. Socialist and agrarian leaders discussed the issue with Prime Minister Leopold Skulski. The National Democracy National Democracy may refer to:

* National democratic state, a state formation conceived by the Soviet concept of national democracy

* National Democracy (Czech Republic)

* National Democracy (Italy)

* National Democracy (Philippines)

* National De ...

politicians had hoped that talks with the Soviets would derail the plans for Józef Piłsudski

Józef Klemens Piłsudski (; 5 December 1867 – 12 May 1935) was a Polish statesman who served as the Chief of State (Poland), Chief of State (1918–1922) and first Marshal of Poland (from 1920). In the aftermath of World War I, he beca ...

's alliance with Symon Petliura and resumption of the war with Russia, which they opposed. National Democrats did not believe that poor and relatively weak Poland was capable of carrying out Piłsudski's objective of building and leading an anti-Russian federation of states. The Soviet peace offers were rejected by Piłsudski, who did not trust the Russians and openly preferred to get the issues resolved on the battlefield. He had stated, on many occasions, that he could beat the Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

s whenever and wherever he wanted to. On 22 April 1920, Stanisław Grabski

Stanisław Grabski (; 5 April 1871 – 6 May 1949) was a Polish economist and politician associated with the National Democracy (Poland), National Democracy political camp. As the top Polish negotiator during the Peace of Riga talks in 1921, Gra ...

, a National Democrat, resigned in protest his chairmanship of the parliamentary committee.

In the early months of 1920, Polish representatives engaged in pretended negotiations, as directed by Piłsudski. Stanisław Wojciechowski

Stanisław Wojciechowski (; 15 March 1869 – 9 April 1953) was a Polish people, Polish politician and scholar who served as President of Poland between 1922 and 1926, during the Second Polish Republic.

He was elected president in 1922, followi ...

, Poland's future president, wrote that Poland had squandered the opportunity to conclude peace with the Soviets when they were most inclined to allow it.

Piłsudski was convinced that a rapid strike at the Soviet forces on the southern front would throw the Red Army far beyond the Dnieper

The Dnieper or Dnepr ( ), also called Dnipro ( ), is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. Approximately long, with ...

River; consequently, the Soviets would have to accept the peace proposals presented by Poland. He argued that war provided optimal growth conditions for Polish industry and was an effective way to fight unemployment and its consequences. General Kazimierz Sosnkowski

General Kazimierz Sosnkowski (; 19 November 1885 – 11 October 1969) was a Polish independence fighter, general, diplomat, and architect.

He was a major political figure and an accomplished commander, notable in particular for his contribu ...

, Piłsudski's close collaborator, claimed that war had turned out to be a highly profitable enterprise for state treasury.

Following fruitless exchanges with Foreign Minister Stanisław Patek

Stanisław Jan Patek (; 1 May 1866 – 25 August 1944), Polish lawyer, freemason and diplomat, served as Polish Minister of Foreign Affairs from 1919 to 1920.

The lawyer

Born in Rusinów, Gmina Rusinów, Rusinów, he was an activist of the ...

, after 7 April Chicherin accused Poland of rejecting the Russian peace offer and heading for war; he notified the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not an explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are calle ...

and called on them to restrain the Polish aggression. The Poles claimed that the Russian Western Front presented an immediate danger and was about to launch an attack, but the narrative was not seen as convincing in the West (the Western Front forces were rather weak at that time and had no plans for an offensive). Soviet Russia's arguments turned out to be more persuasive and the image of Poland had suffered.

The Soviets came to realize that the Polish side was not interested in an armistice at the end of February. First, they suspected a strike in the north, in the direction of the so-called Smolensk

Smolensk is a city and the administrative center of Smolensk Oblast, Russia, located on the Dnieper River, west-southwest of Moscow.

First mentioned in 863, it is one of the oldest cities in Russia. It has been a regional capital for most of ...

Gateway. Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

ordered strengthening of the Western Front defenses. The Polish attack in the Polesia

Polesia, also called Polissia, Polesie, or Polesye, is a natural (geographic) and historical region in Eastern Europe within the East European Plain, including the Belarus–Ukraine border region and part of eastern Poland. This region shou ...

and Volhynia

Volhynia or Volynia ( ; see #Names and etymology, below) is a historic region in Central and Eastern Europe, between southeastern Poland, southwestern Belarus, and northwestern Ukraine. The borders of the region are not clearly defined, but in ...

borderlands on 7 March, led by Władysław Sikorski

Władysław Eugeniusz Sikorski (; 20 May 18814 July 1943) was a Polish military and political leader.

Before World War I, Sikorski established and participated in several underground organizations that promoted the cause of Polish independenc ...

, as well as other actions, reinforced the Soviet suspicions. Sikorski's offensive separated the Soviet Western and Southwestern Fronts. Additional Red Army troops were brought hurriedly from the Caucasian Front and from elsewhere. However, as the Soviet intelligence informed of concentrations of Polish forces in the south and in the north, the Soviet leaders had been unable to determine where the main Polish offensive was going to take place.

Ukrainian involvement

The government of the

The government of the Ukrainian People's Republic

The Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR) was a short-lived state in Eastern Europe. Prior to its proclamation, the Central Council of Ukraine was elected in March 1917 Ukraine after the Russian Revolution, as a result of the February Revolution, ...

(UPR) faced from early 1919 mounting attacks on the territory it claimed. It had lost control over most of Ukraine, which became divided among several disparate powers: Anton Denikin

Anton Ivanovich Denikin (, ; – 7 August 1947) was a Russian military leader who served as the Supreme Ruler of Russia, acting supreme ruler of the Russian State and the commander-in-chief of the White movement–aligned armed forces of Sout ...

's Whites

White is a racial classification of people generally used for those of predominantly European ancestry. It is also a skin color specifier, although the definition can vary depending on context, nationality, ethnicity and point of view.

De ...

, the Red Army and pro-Soviet formations, Nestor Makhno

Nestor Ivanovych Makhno (, ; 7 November 1888 – 25 July 1934), also known as Bat'ko Makhno ( , ), was a Ukrainians, Ukrainian anarchist revolutionary and the commander of the Revolutionary Insurgent Army of Ukraine during the Ukrainian War o ...

's Revolutionary Insurgent Army in the southeast, the Kingdom of Romania in the southwest, Poland, and various bands lacking any political ideology. During the Polish–Ukrainian War, UPR forces fought the Polish Army. An armistice was signed by the combatants on 1 September 1919; it foresaw common action against the Bolsheviks.

The city of Kiev

Kyiv, also Kiev, is the capital and most populous List of cities in Ukraine, city of Ukraine. Located in the north-central part of the country, it straddles both sides of the Dnieper, Dnieper River. As of 1 January 2022, its population was 2, ...

had undergone numerous changes of government. The UPR was established in 1917; a Bolshevik uprising was suppressed in January 1918. The Red Army took Kiev in February, followed by the Army of the German Empire

The German Empire (),; ; World Book, Inc. ''The World Book dictionary, Volume 1''. World Book, Inc., 2003. p. 572. States that Deutsches Reich translates as "German Realm" and was a former official name of Germany. also referred to as Imperia ...

in March; Ukrainian forces retook the city in December. In February 1919, the Red Army regained control. In August, it was taken first by the UPR and then by Denikin's army. The Soviets were in control again from December 1919 (the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic

The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, abbreviated as the Ukrainian SSR, UkrSSR, and also known as Soviet Ukraine or just Ukraine, was one of the Republics of the Soviet Union, constituent republics of the Soviet Union from 1922 until 1991. ...

had its temporary capital in Kharkiv

Kharkiv, also known as Kharkov, is the second-largest List of cities in Ukraine, city in Ukraine.

).

By the time of the Polish offensive, the UPR had been defeated by the Red Army and controlled only a small sliver of land near the territory administered by Poland. Under these circumstances, Petliura saw no choice but to accept Piłsudski's offer of joining an alliance with Poland despite many unresolved territorial disputes between the two nations. Already on 16 November 1919, Polish forces took over Kamianets-Podilskyi

Kamianets-Podilskyi (, ; ) is a city on the Smotrych River in western Ukraine, western Ukraine, to the north-east of Chernivtsi. Formerly the administrative center of Khmelnytskyi Oblast, the city is now the administrative center of Kamianets ...

and the surrounding areas and the Polish authorities allowed the UPR to establish its official state structures there, including military recruiting (while advancing Poland's own claims to the territory). On 2 December, Ukrainian diplomats led by Andriy Livytskyi declared giving up Ukrainian claims to Eastern Galicia

Eastern Galicia (; ; ) is a geographical region in Western Ukraine (present day oblasts of Lviv Oblast, Lviv, Ivano-Frankivsk Oblast, Ivano-Frankivsk and Ternopil Oblast, Ternopil), having also essential historic importance in Poland.

Galicia ( ...

and western Volhynia, in return for Poland's recognition of Ukrainian (UPR) independence. Petliura had thus accepted the territorial gains Poland made in the course of the Polish–Ukrainian War, when it defeated the West Ukrainian People's Republic

The West Ukrainian People's Republic (; West Ukrainian People's Republic#Name, see other names) was a short-lived state that controlled most of Eastern Galicia from November 1918 to July 1919. It included major cities of Lviv, Ternopil, Kolom ...

(WUPR), a Ukrainian statehood attempt in Volhynia and eastern Eastern Galicia. The two regions were largely Ukrainian populated but had a significant Polish minority.

On 21 April 1920, Piłsudski and a three-man Directorate of Ukraine

The Directorate, or Directory () was a provisional collegiate revolutionary state committee of the Ukrainian People's Republic, initially formed on 13–14 November 1918 during a session of the Ukrainian National Union in rebellion against th ...

, led by Petliura, agreed to the Treaty of Warsaw. The treaty has been known as the Petliura–Piłsudski Pact, but it was signed by Polish Deputy Foreign Minister Jan Dąbski and Livytskyi. The text of the agreement was kept secret and it was not ratified by the Polish Sejm. In exchange for agreeing to a border along the Zbruch

The Zbruch (; ) is a river in Western Ukraine, a left tributary of the Dniester.Збруч

Petliura was promised military help in regaining Soviet-controlled Ukrainian territories, including Kiev. He would then reassume the authority of the Ukrainian People's Republic.N. Davies. ''God's Playground, A History of Poland. Vol 2: 1795 to the Present.'' Oxford University Press. 2005. p. 379. A military convention regarding common action and subordination of Ukrainian units to Polish command was signed by the Ukrainian and Polish sides on 24 April. On 25 April, the Polish and the UPR forces began an offensive aimed at Kiev.

A preliminary trade agreement was arrived at on 1 May by the Polish and Ukrainian sides. It foresaw extensive exploitation of Ukraine by the Polish state and capital. The signing of the agreement would reveal its content, with likely catastrophic consequences for Petliura, so it had not been signed.

Factions in Polish parliament, most prominently the National Democrats, protested Piłsudski's alliance with Petliura's Ukraine, his slighting of the Polish government, and the policies of ''

A military convention regarding common action and subordination of Ukrainian units to Polish command was signed by the Ukrainian and Polish sides on 24 April. On 25 April, the Polish and the UPR forces began an offensive aimed at Kiev.

A preliminary trade agreement was arrived at on 1 May by the Polish and Ukrainian sides. It foresaw extensive exploitation of Ukraine by the Polish state and capital. The signing of the agreement would reveal its content, with likely catastrophic consequences for Petliura, so it had not been signed.

Factions in Polish parliament, most prominently the National Democrats, protested Piłsudski's alliance with Petliura's Ukraine, his slighting of the Polish government, and the policies of ''

Piłsudski resolved to realize his political objectives by way of military determinations. For political reasons, he chose to launch an attack on the southern, Ukrainian front, in the direction of Kiev. He had been assembling a large military force throughout the winter. He had become convinced that the Russian White movement and its forces, largely defeated by the Red Army, were no longer a security threat to Poland and that he could take on the remaining adversary, the Bolsheviks.

The Red Army, which had been regrouping since 10 March, was not fully ready for combat. One important factor that limited the Soviet response to the Polish attack was the

Piłsudski resolved to realize his political objectives by way of military determinations. For political reasons, he chose to launch an attack on the southern, Ukrainian front, in the direction of Kiev. He had been assembling a large military force throughout the winter. He had become convinced that the Russian White movement and its forces, largely defeated by the Red Army, were no longer a security threat to Poland and that he could take on the remaining adversary, the Bolsheviks.

The Red Army, which had been regrouping since 10 March, was not fully ready for combat. One important factor that limited the Soviet response to the Polish attack was the

What appeared to be a highly successful military expedition to a city that symbolized the eastern reaches of Polish history (harking back to the intervention of

What appeared to be a highly successful military expedition to a city that symbolized the eastern reaches of Polish history (harking back to the intervention of

After 10 June, Rydz-Śmigły evacuated the 3rd Polish Army from Kiev. The Soviets were back, which was, supposedly, the 16th regime change in Kiev since the beginning of the

After 10 June, Rydz-Śmigły evacuated the 3rd Polish Army from Kiev. The Soviets were back, which was, supposedly, the 16th regime change in Kiev since the beginning of the

In the aftermath of the defeat in Ukraine, the Polish government of Leopold Skulski resigned on 9 June, and a political crisis gripped the government for most of June. Bolshevik and later Soviet propaganda used the Kiev offensive to portray the Polish government as imperialist aggressors.

The Kiev Expedition's defeat dealt a severe blow to Piłsudski's plans for the ''Intermarium'' federation, which had never materialized. From that perspective, the operation may be viewed as a defeat for Piłsudski, as well as for Petliura.

On 4 July, the second, better prepared and stronger northern offensive was launched in Belarus by Russian armies led by Tukhachevsky. Its aim was to capture Warsaw as quickly as possible. The Soviet forces reached the vicinity of the Polish capital in the first half of August.

In Polish politics, Piłsudski had never recovered from his Kiev Expedition debacle. In 1926, he perpetrated a bloody coup.

The historian Andrzej Chwalba summarized some of the losses of the Polish state caused "mainly by the Kiev Expedition":

– The international standing of the Second Polish Republic was stronger before the offensive than a year later. Poland had barely overcome a threat to its existence.

– In July 1920, the Western Allies designated three-fourths of the territory of the former

In the aftermath of the defeat in Ukraine, the Polish government of Leopold Skulski resigned on 9 June, and a political crisis gripped the government for most of June. Bolshevik and later Soviet propaganda used the Kiev offensive to portray the Polish government as imperialist aggressors.

The Kiev Expedition's defeat dealt a severe blow to Piłsudski's plans for the ''Intermarium'' federation, which had never materialized. From that perspective, the operation may be viewed as a defeat for Piłsudski, as well as for Petliura.

On 4 July, the second, better prepared and stronger northern offensive was launched in Belarus by Russian armies led by Tukhachevsky. Its aim was to capture Warsaw as quickly as possible. The Soviet forces reached the vicinity of the Polish capital in the first half of August.

In Polish politics, Piłsudski had never recovered from his Kiev Expedition debacle. In 1926, he perpetrated a bloody coup.

The historian Andrzej Chwalba summarized some of the losses of the Polish state caused "mainly by the Kiev Expedition":

– The international standing of the Second Polish Republic was stronger before the offensive than a year later. Poland had barely overcome a threat to its existence.

– In July 1920, the Western Allies designated three-fourths of the territory of the former

"The Raid on Kiev in Polish Press Propaganda"

''Humanistic Review'' (01/2006)

available online

* "Dramas of Ukrainian-Polish Brotherhood" (documentary film), a review in '' Dzerkalo Tyzhnia'' (Mirror Weekly), March 13–19, 1999

available online

* .

The Military writing of Leon Trotsky Volume 3: 1920 – The War with Poland

The Military writing of Leon Trotsky Volume 3: 1920 – The War with Poland {{DEFAULTSORT:Kiev offensive Battles of the Russian Civil War in 1920 1920 in Poland 1920 in Russia 1920 in Ukraine Battles of the Ukrainian–Soviet War Battles of the Polish–Soviet War 1920s in Kyiv Kiev in the Russian Civil War Battles involving the Ukrainian People's Republic ru:Киевская операция РККА (1920)

Petliura was promised military help in regaining Soviet-controlled Ukrainian territories, including Kiev. He would then reassume the authority of the Ukrainian People's Republic.N. Davies. ''God's Playground, A History of Poland. Vol 2: 1795 to the Present.'' Oxford University Press. 2005. p. 379.

A military convention regarding common action and subordination of Ukrainian units to Polish command was signed by the Ukrainian and Polish sides on 24 April. On 25 April, the Polish and the UPR forces began an offensive aimed at Kiev.

A preliminary trade agreement was arrived at on 1 May by the Polish and Ukrainian sides. It foresaw extensive exploitation of Ukraine by the Polish state and capital. The signing of the agreement would reveal its content, with likely catastrophic consequences for Petliura, so it had not been signed.

Factions in Polish parliament, most prominently the National Democrats, protested Piłsudski's alliance with Petliura's Ukraine, his slighting of the Polish government, and the policies of ''

A military convention regarding common action and subordination of Ukrainian units to Polish command was signed by the Ukrainian and Polish sides on 24 April. On 25 April, the Polish and the UPR forces began an offensive aimed at Kiev.

A preliminary trade agreement was arrived at on 1 May by the Polish and Ukrainian sides. It foresaw extensive exploitation of Ukraine by the Polish state and capital. The signing of the agreement would reveal its content, with likely catastrophic consequences for Petliura, so it had not been signed.

Factions in Polish parliament, most prominently the National Democrats, protested Piłsudski's alliance with Petliura's Ukraine, his slighting of the Polish government, and the policies of ''fait accompli

Many words in the English vocabulary are of French language, French origin, most coming from the Anglo-Norman language, Anglo-Norman spoken by the upper classes in England for several hundred years after the Norman conquest of England, Norman ...

''. They felt that all major Polish moves should have been consulted with the Allies. The National Democrats did not recognize Ukrainians as a nation and to them the Ukrainian issue reduced to a proper division of Ukraine between Poland and White (or Red) Russia.

The UPR was not recognized by the Allies. The British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

and the French warned Poland that the treaty with the UPR amounted to irresponsible adventurism, because Poland lacked strong economic foundations, industry, or stable finances, and was not in a position to impose a new geostrategic situation in Europe.

The UPR was supposed to subordinate its military and economy to Warsaw. Ukraine was going to join the Polish-led ''Intermarium'' federation of states in central and eastern Europe. Piłsudski wanted a Poland-allied Ukraine to be a buffer between Poland and Russia. Provisions in the treaty guaranteed the rights of the Polish and Ukrainian minorities within each state and obliged each side not to conclude international agreements against each other. Piłsudski also needed an alliance with a Ukrainian faction as cover for the action perceived abroad as military aggression.

As the treaty legitimized Polish control over the territory that Ukrainians viewed as rightfully theirs, the alliance received a dire reception from many Ukrainian leaders, ranging from Mykhailo Hrushevsky

Mykhailo Serhiiovych Hrushevsky (; – 24 November 1934) was a Ukrainian academician, politician, historian and statesman who was one of the most important figures of the Ukrainian national revival of the early 20th century. Hrushevsky is ...

, former chairman of the Central Council of Ukraine

The Central Rada of Ukraine, also called the Central Council (), was the All-Ukrainian council that united deputies of soldiers, workers, and peasants deputies as well as few members of political, public, cultural and professional organizations o ...

, to Yevhen Petrushevych

Yevhen Omelianovych Petrushevych (; 3 June 1863 – 29 August 1940) was a Ukrainians, Ukrainian lawyer, politician, and President (government title), president of the West Ukrainian People's Republic formed after the collapse of the Austro-Hung ...

, the leader of the West Ukrainian People's Republic who was forced into exile after the Polish–Ukrainian War. UPR Prime Minister Isaak Mazepa resigned his position in protest of the Warsaw agreements. While to many protesting WUPR activists Petliura was a traitor and renegade, the divided UPR circles quarreled about the merits of the Polish–Ukrainian alliance.

Preparations

Piłsudski resolved to realize his political objectives by way of military determinations. For political reasons, he chose to launch an attack on the southern, Ukrainian front, in the direction of Kiev. He had been assembling a large military force throughout the winter. He had become convinced that the Russian White movement and its forces, largely defeated by the Red Army, were no longer a security threat to Poland and that he could take on the remaining adversary, the Bolsheviks.

The Red Army, which had been regrouping since 10 March, was not fully ready for combat. One important factor that limited the Soviet response to the Polish attack was the

Piłsudski resolved to realize his political objectives by way of military determinations. For political reasons, he chose to launch an attack on the southern, Ukrainian front, in the direction of Kiev. He had been assembling a large military force throughout the winter. He had become convinced that the Russian White movement and its forces, largely defeated by the Red Army, were no longer a security threat to Poland and that he could take on the remaining adversary, the Bolsheviks.

The Red Army, which had been regrouping since 10 March, was not fully ready for combat. One important factor that limited the Soviet response to the Polish attack was the peasant

A peasant is a pre-industrial agricultural laborer or a farmer with limited land-ownership, especially one living in the Middle Ages under feudalism and paying rent, tax, fees, or services to a landlord. In Europe, three classes of peasan ...

Pitchfork uprising that took place in February–March and was taken very seriously by the Bolshevik leadership. It distracted the Soviet Commissar

Commissar (or sometimes ''Kommissar'') is an English transliteration of the Russian (''komissar''), which means ' commissary'. In English, the transliteration ''commissar'' often refers specifically to the political commissars of Soviet and ...

of War Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky,; ; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky'' was a Russian revolutionary, Soviet politician, and political theorist. He was a key figure ...

so much that he had temporarily left Ukraine and Belarus

Belarus, officially the Republic of Belarus, is a landlocked country in Eastern Europe. It is bordered by Russia to the east and northeast, Ukraine to the south, Poland to the west, and Lithuania and Latvia to the northwest. Belarus spans an a ...

poorly defended.

The Kiev Expedition, in which 65,000 Polish and 15,000 Ukrainian soldiers took part, commenced on 25 April 1920. It was carried out by the southern group of Polish armies, under Piłsudski's command. The operation was prepared and carried out by Piłsudski and his allies, Piłsudski's trusted officers with the Polish Legions backgrounds. Major generals on the General Staff were kept in the dark about the emerging details of the offensive. Piłsudski was convinced that the Soviets did not have major military forces at their disposal and that the Ukrainian population would generally support the Polish-led effort.

An intense war propaganda effort had been unleashed to prepare Polish society and the armed forces. On the one hand, the Red Army was presented as exceptionally feeble and led by incompetent commanders, a dispirited and harmless formation. The weakness of the enemy had supposedly offered a unique opportunity for Poland, one that should not be missed, especially given the exceptional abilities of Commander-in-chief Piłsudski and the strength and fitness of the Polish Army. On the other, the Bolsheviks were described as a threatening menace, capable of and getting ready for an offensive on massive scale. The skirmishes that had taken place were portrayed as bloody and fiercely fought battles, harbingers of that assault. An angry reaction from the Allies, opposed to the escalation of the conflict, was expected.

On 27 March, the Sejm militarized the railroads. On 14 April, General Sosnkowski ordered cadets in military schools to report for frontline duty. On 17 April, Piłsudski ordered his forces to assume attack positions. Foreign Minister Stanisław Patek headed for Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's extent varies depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the Western half of the ancient Mediterranean ...

to explain to the Allies the rationale behind the offensive Poland undertook and to seek new shipments of military supplies. Marshal Piłsudski led the military operation in person.

Because of the preparations for a major military offensive, the Polish Armed Forces (about 800,000 soldiers, a majority of whom were on the Polish eastern fronts) had been reorganized as of 1 April. Seven armies had been established by 6 August. The 3rd Army, Piłsudski' favorite, was placed under Edward Rydz-Śmigły

Marshal Edward Śmigły-Rydz also called Edward Rydz-Śmigły, (11 March 1886 – 2 December 1941) was a Polish people, Polish politician, statesman, Marshal of Poland and Commander-in-Chief of Poland's armed forces, as well as a painter and ...

on 19 April. It was designated to execute the Kiev operation, patterned after the taking of Vilnius in the north in April 1919. Another success of a "legionnaire" formation was going to further strengthen the dominant role of the Polish Legions former members and of their chief Piłsudski in the Polish Armed Forces.

60,000 Polish and 4,000 Ukrainian soldiers took part in the initial invasion. The well-equipped Polish 3rd Army was supposed to split the enemy forces into two parts. Speed and maneuverability of the advancing units were emphasized. On 25 April, the day the offensive began, an official communique was issued. The Polish side claimed that the attack was a response to numerous Soviet infringements and was intended to thwart the offensive the enemy had planned.

Piłsudski's forces were divided into three armies. Arranged from north to south, they were the 3rd, 2nd and 6th, with Petliura's forces attached to the 6th Army. Facing them were the Soviet 12th and 14th Armies led by Alexander Yegorov.

Yegorov commanded the forces of the Soviet Southwestern Front. They were weak and poorly equipped. On its western fronts, the Red Army aimed for full military readiness in July 1920. In late April there, its troops were no match for the Polish forces. Piłsudski wanted to believe that the enemy would defend Kiev and a decisive battle would be fought on the city's outskirts, but that was not to be the case. For the most part, Yegorov's units refrained from challenging Piłsudski's armies and withdrew.

Battle

Polish advance

The Polish advantage on the southern Ukrainian front caused a quick defeat of the Soviet armies and their displacement past the Dnieper River.Zhytomyr

Zhytomyr ( ; see #Names, below for other names) is a city in the north of the western half of Ukraine. It is the Capital city, administrative center of Zhytomyr Oblast (Oblast, province), as well as the administrative center of the surrounding ...

was captured on 26 April. Lieutenant Tadeusz Bór-Komorowski was among the Polish cavalry men recognized for valour. Planes of the Polish Air Force

The Polish Air Force () is the aerial warfare Military branch, branch of the Polish Armed Forces. Until July 2004 it was officially known as ''Wojska Lotnicze i Obrony Powietrznej'' (). In 2014 it consisted of roughly 26,000 military personnel an ...

caused panic in the enemy ranks. In a 26 April letter to Prime Minister Leopold Skulski, Piłsudski characterized the Bolshevik formations as "almost incapable of any resistance", strongly impressed by the extraordinary speed of Polish moves. Contrary to the Polish expectations, many towns had been taken without any opposition from the Red Army, whose units were quickly withdrawn by their commanders. Within a week, the Soviet 12th Army had become disorganized. The Polish 6th Army and Petliura's forces pushed the Soviet 14th Army out of central Ukraine as they quickly marched eastward through Vinnytsia

Vinnytsia ( ; , ) is a city in west-central Ukraine, located on the banks of the Southern Bug. It serves as the administrative centre, administrative center of Vinnytsia Oblast. It is the largest city in the historic region of Podillia. It also s ...

. In Vinnytsia, from 13 May, Petliura organized his government and prepared further offensive in the direction of Odessa

ODESSA is an American codename (from the German language, German: ''Organisation der ehemaligen SS-Angehörigen'', meaning: Organization of Former SS Members) coined in 1946 to cover Ratlines (World War II aftermath), Nazi underground escape-pl ...

.

The Soviet 12th Army evacuated from Kiev on 6 May. "Those beasts", wrote Piłsudski to General Sosnkowski on 6 May, "instead of defending Kiev, flee from there". The Polish offensive stopped at Kiev and the front was formed along the Dnieper. The combined Polish-Ukrainian forces under General Rydz-Śmigły entered the city on 7 May. A bridgehead was established and reached 15 kilometers east of the Dnieper, which was as far as the Polish 3rd Army advanced. About 20,000 Red Army troops had been taken prisoner by 2 May. Only 150 Polish soldiers died during the entire operation.

On 9 May, the Polish and Ukrainian troops celebrated the capture of Kiev with the victory parade on Khreshchatyk

Khreshchatyk (, ) is the main street of Kyiv, the capital city of Ukraine. The street is long, and runs in a northeast-southwest direction from European Square (Kyiv), European Square through the Maidan Nezalezhnosti, Maidan to Bessarabska Sq ...

, the city's main street. Control over Kiev was given to the Ukrainian People's Republic and the Ukrainian 6th Division was garrisoned there. However, the military achievement turned out to be incomplete, as the Bolshevik armies, contrary to Polish objectives, avoided decisive confrontations and had not been destroyed. While the Polish forces had been drawn deeply into the Ukrainian territory, the Soviets could not be made to participate in forced negotiations, as the Polish side had hoped. The Polish command soon felt compelled to transfer some of its units to the northern Belarusian front.

On 1 May, in a letter to his wife, Piłsudski declared a victory: "With the first stage completed, you must now be very surprised and a little scared by these great successes. In the meantime, I prepare for the second phase and arrange the forces and materials so it can be as effective as the first one. So far, I had completely destroyed the entire Bolshevik 12th Army, of which nothing at all had been left ... one feels dizzy thinking of the amount of war materials captured ... I had won this great battle by a daring plan and extraordinary energy put into its execution."

The triumphant tone turned out to be premature. The 12th Army, in particular, had been battered but not destroyed, as the marshal was soon to find out.

The military and political developments elicited a sharp response in Russia, where Vladimir Lenin and Leon Trotsky appealed to national sentiments and called for total war with expansionist Poland. General Aleksei Brusilov

Aleksei Alekseyevich Brusilov (, ; rus, Алексей Алексеевич Брусилов, p=ɐlʲɪkˈsʲej ɐlʲɪkˈsʲejɪvʲɪdʑ brʊˈsʲiɫəf; – 17 March 1926) was a Russian and later Soviet general most noted for the developmen ...

, former chief commander of the Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

's Tsarist army and from 2 May chairman of the new Council of Military Experts, appealed to his former officers to re-enlist with the Bolshevik forces and 40,000 of them complied. A large army of volunteers had also been raised and sent to the Western Front; the first units departed Moscow on 6 May.

The Soviet leaders considered the Polish attack in Ukraine a stroke of good fortune. They saw Poland as falling into its own trap and expected a military victory for Russia. Moscow had masterfully unleashed psychological warfare in Soviet Russia, Poland, and Europe. A new Great Patriotic War

The Eastern Front, also known as the Great Patriotic War (term), Great Patriotic War in the Soviet Union and its successor states, and the German–Soviet War in modern Germany and Ukraine, was a Theater (warfare), theatre of World War II ...

was declared and Russian society mobilized accordingly. For the Russian and Soviet publicists, the Kiev Expedition had become synonymous with the Polish politics of aggression and political thoughtlessness. The negative image of Poland they had created was exploited by the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

in the following years, most importantly in September 1939 and during World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

.

What appeared to be a highly successful military expedition to a city that symbolized the eastern reaches of Polish history (harking back to the intervention of

What appeared to be a highly successful military expedition to a city that symbolized the eastern reaches of Polish history (harking back to the intervention of Bolesław I the Brave

Bolesław I the Brave (17 June 1025), less often List of people known as the Great, known as Bolesław the Great, was Duke of Poland from 992 to 1025 and the first King of Poland in 1025. He was also Duke of Bohemia between 1003 and 1004 as Boles ...

in 1018) caused enormous euphoria in Poland. The Polish Sejm declared the need to establish such "strategic borders" that would make a future war improbable already on 4 May. Piłsudski was lionized by the public and by politicians of different orientations. On 18 May in Warsaw, he was greeted in the Sejm by its Marshal Wojciech Trąmpczyński

Wojciech Stefan Trąmpczyński (8 February 1860 – 2 March 1953) was a Polish lawyer and National Democracy (Poland), National Democratic politician. Voivode of the Poznań Voivodeship (1921-1939), Poznań Voivodeship in 1919. He served as ...

, who spoke of a tremendous triumph of Polish arms and said to Piłsudski: "The victories of our army accomplished under your leadership will influence the future in our east". "I left Warsaw

Warsaw, officially the Capital City of Warsaw, is the capital and List of cities and towns in Poland, largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the Vistula, River Vistula in east-central Poland. Its population is officially estimated at ...

that was intoxicated by the triumph; the nation had lost its sense of reality" – commented Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French general and statesman who led the Free France, Free French Forces against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Government of the French Re ...

.

On 26 April in Zhytomyr, in his "Call to the People of Ukraine", Piłsudski assured that "the Polish Army would only stay as long as necessary until a legal Ukrainian government took control over its own territory". Many Ukrainians were both anti-Polish and anti-Bolshevik, and were suspicious of the advancing Poles. From 12 May, a newly established Polish military authority had been engaged in requisitioning goods from the Ukrainian population, giving rise to protests lodged by Ukrainian officials. Among the machinery and products confiscated from Ukraine were thousands of loaded cars, engines and railroad equipment, in violation of the Polish–Ukrainian accords. Because of the changing military situation, such activities had taken place over a limited period of time. The Soviet propaganda

Propaganda in the Soviet Union was the practice of state-directed communication aimed at promoting class conflict, proletarian internationalism, the goals of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, and the party itself.

The main Soviet cen ...

had the effect of encouraging negative Ukrainian sentiment towards the Polish operation and Polish-Ukrainian relations in general. Actions such as punitive military expeditions organized by Polish land owners against rebellious Ukrainian peasants strengthened the effectiveness of Bolshevik propaganda.

The Polish command restricted administrative districts in Ukraine where Petliura's army was allowed to conduct recruitment campaigns. Polish officials claimed that Ukrainian candidates for the military were demoralized, would cause trouble and be of little use. A (small) Ukrainian army was supposed to only symbolize the Polish–Ukrainian alliance; the victory was intended to belong to Poland alone. A strong, victorious Ukrainian army might have demanded revisions in the treaties and reopen border disputes. A modest in size and capabilities UPR, a Poland-dependent "buffer" state, would guarantee loyalty and solidarity with Polish politics. Polish soldiers in Ukraine often acted as an occupation force. According to Polish General Leon Berbecki

Leon Berbecki (28 July 1875, Lublin – 23 March 1963, Gliwice) was a Polish army officer, who fought in the Russo-Japanese War and World War I with the Imperial Russian Army. Following the foundation of the Second Polish Republic, Berbecki ser ...

, "the orgy of plunder" ... "lasted for several weeks". Piłsudski and other Polish commanders had been instrumental in their treatment of Petliura and the leading Ukrainian officers.

The Ukrainian population was tired of hostilities after several years of war. Nationality-conscious Ukrainians often thought of Petliura as the man who sold out

To "sell out" is to compromise one's integrity, morality, authenticity, or principles in exchange for personal gain, such as money or power. In terms of music or art, selling out is associated with attempts to tailor material to a mainstream or ...

Ukraine to Poland. Efforts to generate Ukrainian popular support for the idea of the country's alliance with Poland had failed. The growth of Petliura's Ukrainian forces was slow: there were about 23,000 soldiers in September 1920.

Petliura wanted the Polish forces to remain in Ukraine for the time being, while the UPR engaged in the building of its statehood. Piłsudski had a different solution in mind. He planned to definitely break the Soviet armies and dictate his peace conditions to Red Russia by 10 May. Then the Polish military would begin its evacuation. However, instead of negotiating, the enemy prepared for a counteroffensive. The Polish command knew only that the Southwestern Front forces east of the Dnieper were being systematically reinforced. Józef Jaklicz, chief-of-staff of the 15th Infantry Division, wrote to his wife on 30 May: "We have overestimated our strength and threw ourselves into politics on a grand scale, with the military engaged, without being properly secured ... The soldiers are cut-off from the world, there is no news or communication." Polish soldiers feared the hostility of Ukrainian rural population.

Soviet counterattack

The Polish forces were uniformly and thinly stretched along Poland's eastern front that was 1200 km long. They were reinforced by someWorld War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

trenches. At some locations, considered strategically important, concentrations of troops were established, but they would be easy to go around. French General Paul Prosper Henrys, who visited the front, noted the weakness of Polish rear reserves. He suggested that the ratio of frontline troops to the reserves should be 2:1, not 5:1, as was the case.

According to the concept of Boris Shaposhnikov

Boris Mikhaylovich Shaposhnikov () ( – 26 March 1945) was a Soviet Union, Soviet military officer, Military theory, theoretician and Marshal of the Soviet Union. He served as the Chief of the General Staff (Russia), Chief of the General St ...

, chief operations manager on the Field Staff of the Revolutionary Military Council

The Revolutionary Military Council (), sometimes called the Revolutionary War Council Brian PearceIntroductionto Fyodor Raskolnikov s "Tales of Sub-lieutenant Ilyin." or ''Revvoyensoviet'' (), was the supreme military authority of Soviet Rus ...

, the Soviet leadership decided to concentrate forces in Belarus and launch a counteroffensive from there. The Polish challenge in Ukraine necessitated a Soviet response. Trotsky arrived at Mogilev

Mogilev (; , ), also transliterated as Mahilyow (, ), is a city in eastern Belarus. It is located on the Dnieper, Dnieper River, about from the Belarus–Russia border, border with Russia's Smolensk Oblast and from Bryansk Oblast. As of 2024, ...

to personally motivate Russian troops to avenge the Polish insult. He predicted the Red Army's presence in Warsaw in the near future. On 14 May, Trotsky ordered the Red Army to attack.

Mikhail Tukhachevsky

Mikhail Nikolayevich Tukhachevsky ( rus, Михаил Николаевич Тухачевский, Mikhail Nikolayevich Tukhachevskiy, p=tʊxɐˈtɕefskʲɪj; – 12 June 1937), nicknamed the Red Napoleon, was a Soviet general who was prominen ...

, accomplished in fighting the Whites

White is a racial classification of people generally used for those of predominantly European ancestry. It is also a skin color specifier, although the definition can vary depending on context, nationality, ethnicity and point of view.

De ...

, was made commander of the Western Front on 1 May 1920. He wanted to launch an assault on the Belarusian front before Polish troops arrive from the Ukrainian front. On 14 May, Tukhachevsky's so-called first offensive began. Western Front's 15th and 16th Armies attacked the slightly weaker Polish forces (the combatants had respectively 75,000 and 72,000 combined infantry and cavalry soldiers at their disposal) and penetrated the Polish-held areas to the depth of one hundred kilometers. The transfer of two Polish divisions from the Ukrainian front had to be expedited and the newly formed Polish Reserve Army (32,000 men) was used after 25 May. Because of the energetic Polish counter-offensive led by Stanisław Szeptycki, Kazimierz Sosnkowski and Leonard Skierski, by 8 June the Poles had recovered the bulk of the lost territory, Tukhachevsky's armies were withdrawn to the Avuta and Berezina

The Berezina or Byarezina (, ; ) is a river in Belarus and a right tributary of the Dnieper. The river starts in the Berezinsky Biosphere Reserve. The length of the Berezina is . The width of the river is 15–20 m, the maximum is 60 m. The ba ...

Rivers, and the front had remained inactive until July. While Tukhachevsky retained control of the strategic points needed for future offensive action, the Polish high command kept its ineffective system of linear arrangement of forces and weak rear reserves.

The Soviet forces south of Polesia were also getting ready for a counterassault. On 5 May, Felix Dzerzhinsky

Felix Edmundovich Dzerzhinsky (; ; – 20 July 1926), nicknamed Iron Felix (), was a Soviet revolutionary and politician of Polish origin. From 1917 until his death in 1926, he led the first two Soviet secret police organizations, the Cheka a ...

arrived in Kharkiv and brought with him 1,400 Cheka

The All-Russian Extraordinary Commission ( rus, Всероссийская чрезвычайная комиссия, r=Vserossiyskaya chrezvychaynaya komissiya, p=fsʲɪrɐˈsʲijskəjə tɕrʲɪzvɨˈtɕæjnəjə kɐˈmʲisʲɪjə, links=yes), ...

functionaries, charged with improving discipline in Red Army units. The plan for the counteroffensive in the south was approved during a 15 May conference in which Sergey Kamenev

Sergey Sergeyevich Kamenev (; April 16 Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O.S. April 4 1881 – August 25, 1936) was a Soviet Union">Soviet military leader who reached Komandarm 1st rank.

Kamene ...

also participated. Because the 12th and the 14th Armies of the Southwestern Front still did not have sufficient resources to launch an attack, the participants decided to wait for the arrival of the 1st Cavalry Army

__NOTOC__

The 1st Cavalry Army (), or ''Konarmia'' (Кона́рмия, "Horsearmy"), was a prominent Red Army military formation that served in the Russian Civil War and Polish–Soviet War, Polish-Soviet War.

History

Formation

On 17 Novem ...

under Semyon Budyonny

Semyon Mikhailovich Budyonny ( rus, Семён Миха́йлович Будённый, Semyon Mikháylovich Budyonnyy, p=sʲɪˈmʲɵn mʲɪˈxajləvʲɪdʑ bʊˈdʲɵnːɨj, a=ru-Simeon Budyonniy.ogg; – 26 October 1973) was a Russian and ...

, which was on its way (from 10 March) to the Polish–Soviet combat area. The 1st Cavalry Army, a highly regarded formation credited with the destruction of the "White" Volunteer Army, was assigned by Kamenev and Dzerzhinsky the leading role in attacking the Polish armies in Ukraine. On 1 May, the 1st Cavalry Army was over 40,000 men (and women) strong, but only 18,000 of its soldiers were brought to bear on the Polish front.

To better prepare for the expected Soviet counteroffensive, the Ukrainian Front, a new Polish formation, was established on 28 May. It comprised 57,000 soldiers and was charged with holding onto the territory that Polish forces had acquired. Polish (and Allied) commanders held Soviet cavalry in low regard. To Piłsudski, Budyonny's horse people were like bands of nomads or swarms of locusts (a reference to their propensity to wreak havoc on civilian communities encountered), incapable of executing any effective cavalry charge

Charge or charged may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Films

* ''Charge, Zero Emissions/Maximum Speed'', a 2011 documentary

Music

* ''Charge'' (David Ford album)

* ''Charge'' (Machel Montano album)

* '' Charge!!'', an album by The Aqu ...

.

Alexander Yegorov, commander of the Russian Southwestern Front, having received considerable reinforcements, initiated on 28 May an assault maneuver in the Kiev area. Besides the Soviet main armies, the special formations of Iona Yakir

Iona Emmanuilovich Yakir (; 3 August 1896 – 12 June 1937) was a Red Army commander and one of the world's major military reformers between World War I and World War II. He was an early and major military victim of the Great Purge, alongsid ...

and of Filipp Golikov, in addition to the 1st Cavalry Army, became especially important in attacks on the Polish positions. The 1st Cavalry Army was supposed to penetrate the Polish formations and get to their rear, while the Russian 12th and 14th Armies would complete the frontal destruction. After a week of storming the Polish defenses, on 5 June the 1st Cavalry Army forced its way between the Polish 3rd and 6th Armies. It infiltrated and disorganized the rear infrastructure of Polish lines, eliminated many smaller units, and caused extensive destruction.

Rydz-Śmigły proceeded to fortify Kiev, which he intended to defend. He refused to obey the order from the Ukrainian Front commander Antoni Listowski to withdraw in a timely manner. He demanded a written order from Piłsudski, which he received on 10 June. The Polish Army evacuation, accomplished over the next few days, was preceded by the destruction of the city's bridges, electric power stations, and water pumps on the Dnieper.

Polish retreat

After 10 June, Rydz-Śmigły evacuated the 3rd Polish Army from Kiev. The Soviets were back, which was, supposedly, the 16th regime change in Kiev since the beginning of the

After 10 June, Rydz-Śmigły evacuated the 3rd Polish Army from Kiev. The Soviets were back, which was, supposedly, the 16th regime change in Kiev since the beginning of the Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution, social change in Russian Empire, Russia, starting in 1917. This period saw Russia Dissolution of the Russian Empire, abolish its mona ...

.

For the next two months, while fighting the Soviets, the Polish armies kept retreating toward the west. To break the encirclement, Rydz-Śmigły's 3rd Army rapidly withdrew in that direction. It took considerable military experience and ingenuity to maneuver the army, the trains of wagons full of war spoils, and fleeing civilians, out of immediate danger. The army experienced losses in life and equipment, but broke out of the entrapment by 16 June. However, contrary to Piłsudski's expectations, it was unable to launch successful counterattacks.

In the following weeks, the 2nd and 3rd Armies fought the Bolshevik forces on many occasions. Initially, the strength of their resistance and determination surprised Budyonny and his commanders. On 26 June, Rydz-Śmigły replaced Listowski as commander of the Ukrainian Front, but the Polish armies kept retreating and suffering losses. As they had lost their strategic initiative, the morale of the Polish and Ukrainian soldiers deteriorated and with time their units had become more inclined to surrender. Despite the strength of the Polish artillery formations, the officer corps in particular was subjected to heavy losses, in part due to the continued attempts to launch counterattacks.

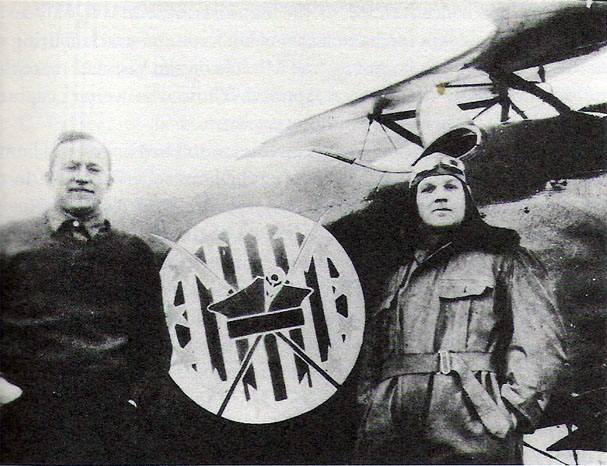

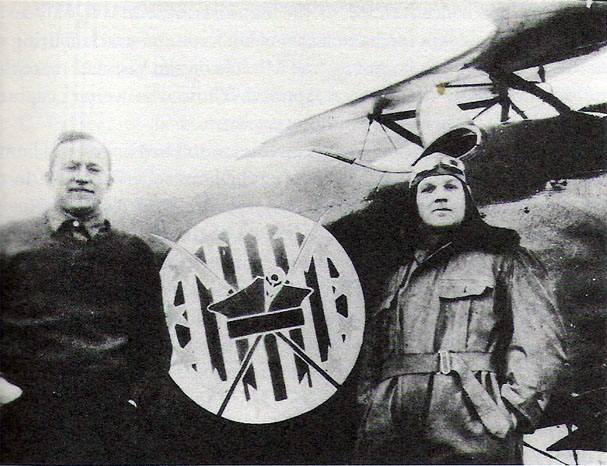

The Polish 7th Air Escadrille, known also as the Kościuszko Squadron, manned largely by American pilots, was particularly helpful. In late May and early June, they flew many bombing and reconnaissance missions. They slowed the Soviet counteroffensive and the commandant of the Polish 13th Infantry Division commented: "Without the American pilots we would have been long gone". Their machine gun attacks held back the progress of Budyonny's cavalry. The squadron's leading pilot, Merian C. Cooper

Merian Caldwell Cooper (October 24, 1893 – April 21, 1973) was an American filmmaker, actor, producer and air officer. In film, his most famous work was the 1933 movie ''King Kong (1933 film), King Kong'', and he is credited as co-inventor of ...

, was shot down and imprisoned by the Russians, but escaped after two months. After the 16 to 18 August intense fighting in the Lviv area, the fourteen planes of the squadron were credited again with stopping Budyonny and saving the situation.

The Polish 3rd Army withdrew to the Styr

The Styr (; ; ) is a right tributary of the Pripyat, with a length of . Its basin area is and located in the historical region of Volhynia.

The Styr begins near Brody, Lviv Oblast, then flows into Rivne Oblast, Volyn Oblast, then into Brest ...

River line, the 6th Army to the Zbruch River. On 5 July, Brigadier Marian Kukiel wrote: "In the afternoon, we were hit by the unexpected order to retreat to the Zbruch. Depressing news announcing a lost war, or at least a lost campaign".

On 19 July, the Poles engaged a substantial Soviet force and fought the enemy for two weeks, which culminated in the Battle of Brody

Brody (, ; ; ; ) is a city in Zolochiv Raion, Lviv Oblast, Zolochiv Raion, Lviv Oblast, western Ukraine. It is located in the valley of the upper Styr, Styr River, approximately northeast of the oblast capital, Lviv. Brody hosts the administrati ...

and Berestechko (29 July–3 August). The offensive battle was terminated by Piłsudski, who withdrew two Polish divisions and sent them north, one to strengthen the force concentration at the Wieprz

The Wieprz (, ; ) is a river in central-eastern Poland, and a tributary of the Vistula. It is the country's ninth longest river, with a total length of 349 km and a catchment area of 10,497 km2, all within Poland. Its course near the to ...

River and one to defend Warsaw. The town of Brody was kept by the Polish forces. Budyonny complained of his Cossacks being stretched to their limits and exhausted, lacking food and feed for the horses, who were too tired to fend off flies.

Ultimately, the Polish armies were forced to withdraw to their initial positions. The Russian forces also remained in western Ukraine and become involved in heavy fighting for the area of the city of Lviv, which had been under 1st Cavalry Army's siege from 12 August.

The Kiev Expedition ended with a loss of all the territories gained by the Poles and their Ukrainian allies in the course of the campaign, and also of Volhynia and parts of Eastern Galicia. However, the retreating Polish forces avoided destruction by the Soviet armies.

Aftermath

In the aftermath of the defeat in Ukraine, the Polish government of Leopold Skulski resigned on 9 June, and a political crisis gripped the government for most of June. Bolshevik and later Soviet propaganda used the Kiev offensive to portray the Polish government as imperialist aggressors.

The Kiev Expedition's defeat dealt a severe blow to Piłsudski's plans for the ''Intermarium'' federation, which had never materialized. From that perspective, the operation may be viewed as a defeat for Piłsudski, as well as for Petliura.

On 4 July, the second, better prepared and stronger northern offensive was launched in Belarus by Russian armies led by Tukhachevsky. Its aim was to capture Warsaw as quickly as possible. The Soviet forces reached the vicinity of the Polish capital in the first half of August.

In Polish politics, Piłsudski had never recovered from his Kiev Expedition debacle. In 1926, he perpetrated a bloody coup.

The historian Andrzej Chwalba summarized some of the losses of the Polish state caused "mainly by the Kiev Expedition":

– The international standing of the Second Polish Republic was stronger before the offensive than a year later. Poland had barely overcome a threat to its existence.

– In July 1920, the Western Allies designated three-fourths of the territory of the former

In the aftermath of the defeat in Ukraine, the Polish government of Leopold Skulski resigned on 9 June, and a political crisis gripped the government for most of June. Bolshevik and later Soviet propaganda used the Kiev offensive to portray the Polish government as imperialist aggressors.

The Kiev Expedition's defeat dealt a severe blow to Piłsudski's plans for the ''Intermarium'' federation, which had never materialized. From that perspective, the operation may be viewed as a defeat for Piłsudski, as well as for Petliura.

On 4 July, the second, better prepared and stronger northern offensive was launched in Belarus by Russian armies led by Tukhachevsky. Its aim was to capture Warsaw as quickly as possible. The Soviet forces reached the vicinity of the Polish capital in the first half of August.

In Polish politics, Piłsudski had never recovered from his Kiev Expedition debacle. In 1926, he perpetrated a bloody coup.

The historian Andrzej Chwalba summarized some of the losses of the Polish state caused "mainly by the Kiev Expedition":

– The international standing of the Second Polish Republic was stronger before the offensive than a year later. Poland had barely overcome a threat to its existence.

– In July 1920, the Western Allies designated three-fourths of the territory of the former Duchy of Teschen

The Duchy of Teschen (), also Duchy of Cieszyn () or Duchy of Těšín (), was one of the Duchies of Silesia centered on Cieszyn () in Upper Silesia. It was split off the Silesian Duchy of Opole and Racibórz in 1281 during the feudal divisio ...

as part of Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia ( ; Czech language, Czech and , ''Česko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland beca ...

. This led to the Polish armed annexation of the Trans-Olza

Trans-Olza (, ; , ''Záolší''; ), also known as Trans-Olza Silesia (), is a territory in the Czech Republic which was disputed between Poland and Czechoslovakia during the Interwar Period. Its name comes from the Olza River.

The history of ...

region in 1938 and to the general perception of Poland as an aggressive power and ally of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

.

– The 1920 East Prussian plebiscite took place in July 1920, an unfortunate time for the Polish plebiscite campaign. The magnitude of the plebiscite loss negatively affected Poland's future border with Germany. Further war in the east hurt also Polish propaganda efforts in Upper Silesia

Upper Silesia ( ; ; ; ; Silesian German: ; ) is the southeastern part of the historical and geographical region of Silesia, located today mostly in Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic. The area is predominantly known for its heav ...

, which was acknowledged by Wojciech Korfanty

Wojciech Korfanty (; born Adalbert Korfanty; 20 April 1873 – 17 August 1939) was a Polish activist, journalist and politician, who served as a member of the German parliaments, the Reichstag and the Prussian Landtag, and later, in the Poli ...

and other Polish activists.

– Had it not been for the Kiev Expedition, Poland would have likely retained its administration of the Vilnius

Vilnius ( , ) is the capital of and List of cities in Lithuania#Cities, largest city in Lithuania and the List of cities in the Baltic states by population, most-populous city in the Baltic states. The city's estimated January 2025 population w ...

region, the Piłsudski-ordered Żeligowski's Mutiny

Żeligowski's Mutiny (, also , ) was a Polish false flag operation led by General Lucjan Żeligowski in October 1920, which resulted in the creation of the Republic of Central Lithuania. Józef Piłsudski, the Chief of State of Poland, surreptit ...

and the takeover of Vilnius would not have taken place and the Polish–Lithuanian relations would not be as bad as they ended up being.

– Poland's reputation had suffered as the country's policies in the east were seen as irresponsible and adventurous by historians and publicists outside of Poland. The efforts of their Polish counterparts to alter the image of Poland as an aggressor have not been successful.

In 1920, hundreds of thousands of lives may have been lost. Poland ended up with reduced territory it controlled and the country's condition in international politics was weaker than before the war.

Accusations of misconduct

Both parties of the conflict made mutual accusations of violations of the basic rules of war conduct. They were rampant and full of exaggerations.Norman Davies

Ivor Norman Richard Davies (born 8 June 1939) is a British and Polish historian, known for his publications on the history of Europe, Poland and the United Kingdom. He has a special interest in Central and Eastern Europe and is UNESCO Profes ...

wrote that "Polish and Soviet newspapers of that time competed in which could produce a more terrifying portrait of their opponent."

According to Ukrainian General Yuriy Tyutyunnyk, (following the Polish invasion of Ukraine) "train after train sped out of Ukraine, taking out sugar, flour, grain, cattle, horses, and all the other riches of Ukraine". Tyutyunnyk was referring to the appropriations ordered by Piłsudski and other Polish commanders.

A breakdown in law and order ensued from the Polish takeover of Kiev on 7 May. Kiev's new conquerors looted the city and its residents, as did the marauding remnants of the Russian forces. Polish officers were empowered to shoot the burglars, but piles of stolen goods waiting to be loaded could be seen at the main train station. The Bolsheviks, leaving the city, took with them their political prisoners and many people recently arrested by the Cheka, including numerous Poles.

The Poles have been accused of destroying much of Kiev's infrastructure, including the passenger and cargo railway stations and other purely civilian objects crucial for the city's functioning, such as the electric power station

A power station, also referred to as a power plant and sometimes generating station or generating plant, is an industrial facility for the electricity generation, generation of electric power. Power stations are generally connected to an electr ...

s, the city sewerage

Sewerage (or sewage system) is the infrastructure that conveys sewage or surface runoff ( stormwater, meltwater, rainwater) using sewers. It encompasses components such as receiving drains, manholes, pumping stations, storm overflows, and scr ...

and water supply

Water supply is the provision of water by public utilities, commercial organisations, community endeavors or by individuals, usually via a system of pumps and pipes. Public water supply systems are crucial to properly functioning societies. Th ...

systems, as well as its monuments. The Poles denied that they had committed any such acts of vandalism, claiming that the only deliberate damage they carried out during their evacuation was blowing up the bridges in Kiev across the Dnieper River, for military reasons. According to some Ukrainian sources, other instances of destruction in the city had also occurred. Among the destroyed objects were the mansion of the general-governor of Kiev at Institutskaya street, and the monument to Taras Shevchenko

Taras Hryhorovych Shevchenko (; ; 9 March 1814 – 10 March 1861) was a Ukrainian poet, writer, artist, public and political figure, folklorist, and ethnographer. He was a fellow of the Imperial Academy of Arts and a member of the Brotherhood o ...

, recently erected on the former location of the monument to Olga of Kiev

Olga (; ; – 11 July 969) was a regent of Kievan Rus' for her son Sviatoslav from 945 until 957. Following her baptism, Olga took the name Elenа. She is known for her subjugation of the Drevlians, a tribe that had killed her husband Igor. E ...

.

Richard Watt wrote that the Soviet advance into Ukraine was characterized by mass killing of civilians and the burning of entire villages, especially by Budyonny's Cossacks; such actions were designed to instill a sense of fear in the Ukrainian population. Davies noted that on 7 June Budyonny's 1st Army destroyed the bridges in Zhytomyr, wrecked the train station and burned various buildings. On the same day it burned a hospital in Berdychiv

Berdychiv (, ) is a historic city in Zhytomyr Oblast, northern Ukraine. It serves as the administrative center of Berdychiv Raion within the oblast. It is south of the administrative center of the oblast, Zhytomyr. Its population is approximat ...

with 600 patients and Red Cross

The organized International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is a Humanitarianism, humanitarian movement with approximately 16million volunteering, volunteers, members, and staff worldwide. It was founded to protect human life and health, to ...

nuns. Such terror tactics he characterized as common for Budyonny's forces.

According to Chwalba, "The news of the savagery, brutality and ruthlessness of the cavalry had a paralyzing effect and demoralized a soldier, who constantly looked back, seeking an opportunity to run away or desert. Menacing communications with such content had often been disseminated by Red Army operatives, who were aware of their debilitating effect."

Isaac Babel

Isaac Emmanuilovich Babel ( – 27 January 1940) was a Soviet writer, journalist, playwright, and literary translator. He is best known as the author of ''Red Cavalry'' and ''Odessa Stories'', and has been acclaimed as "the greatest prose write ...

, a Red Army war correspondent, wrote in his diary about atrocities committed by Polish troops and their allies, murders of Polish POW

POW is "prisoner of war", a person, whether civilian or combatant, who is held in custody by an enemy power during or immediately after an armed conflict.

POW or pow may also refer to:

Music

* P.O.W (Bullet for My Valentine song), "P.O.W" (Bull ...

s by Red Army troops, and looting of the civilian population by Budyonny's Red Cossacks. Babel's writings became well known and Budyonny himself protested against the "defamation" of his troops.

Order of battle