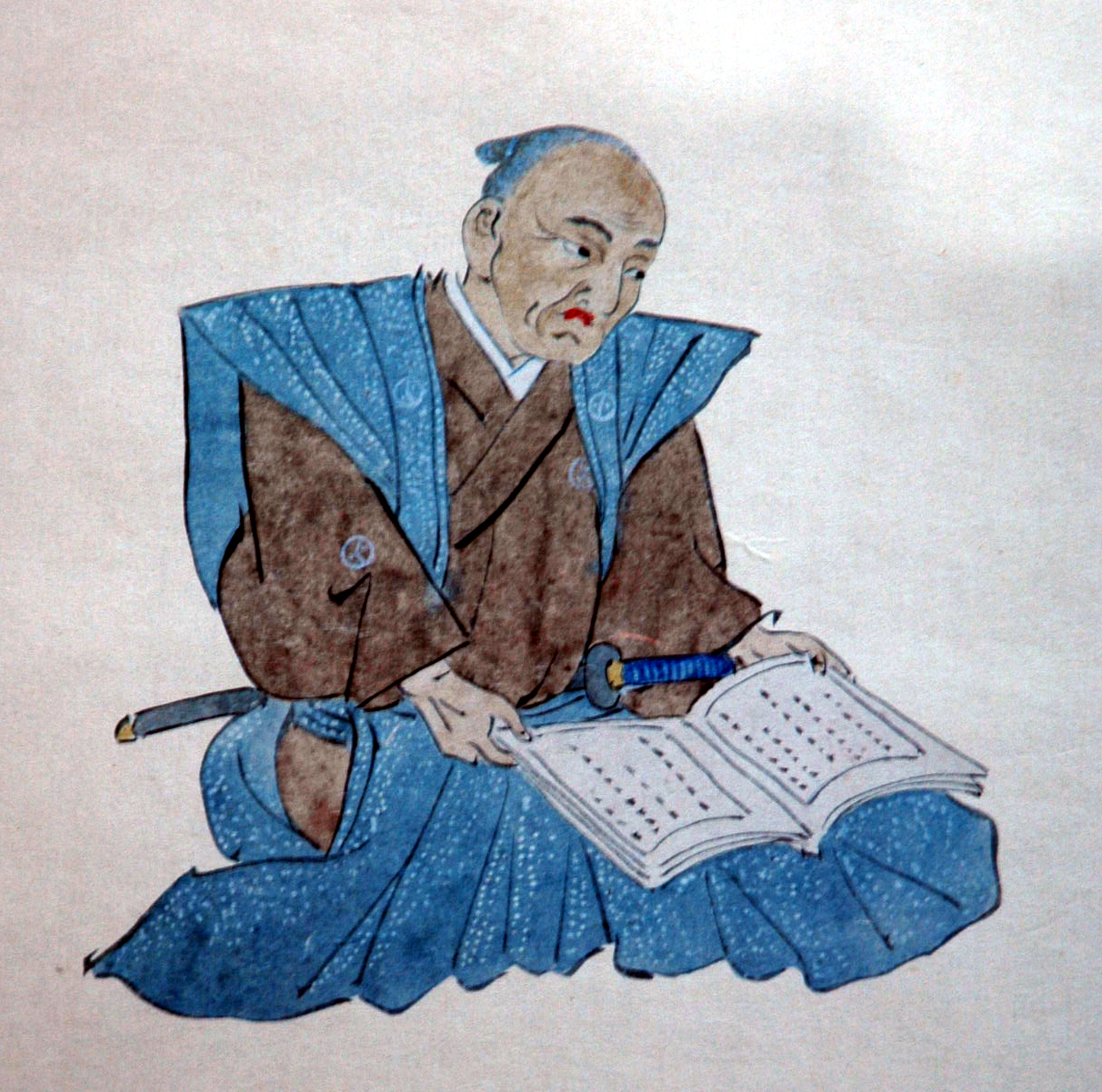

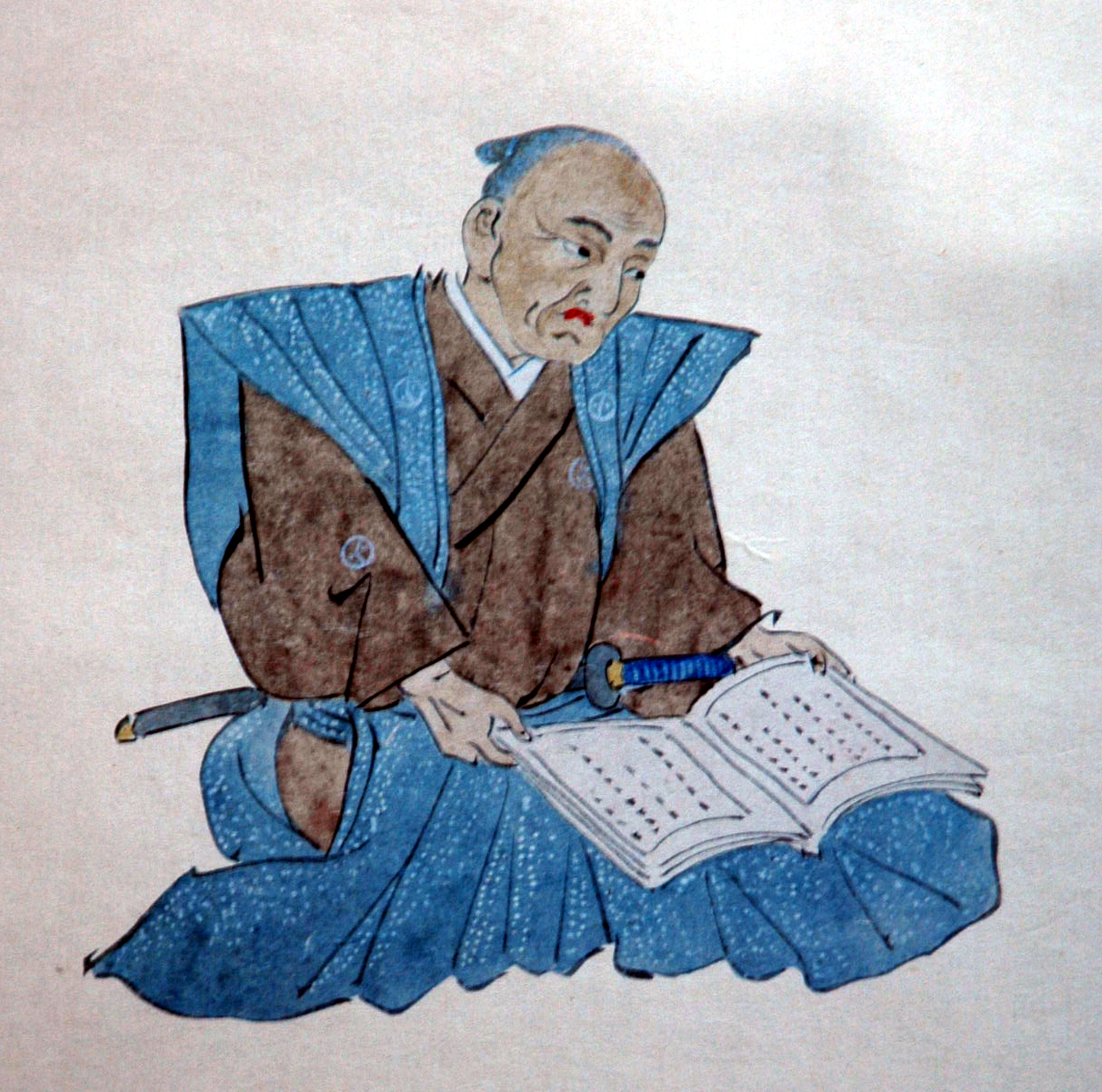

Kumazawa Banzan on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

was a Japanese Confucian. He learned Yangmingism from Nakae Tōju and served Ikeda Mitsumasa, the lord of Bizen Province. In his later years, he was imprisoned for writing ''Daigaku Wakumon'', which contained criticism of

was a Japanese Confucian. He learned Yangmingism from Nakae Tōju and served Ikeda Mitsumasa, the lord of Bizen Province. In his later years, he was imprisoned for writing ''Daigaku Wakumon'', which contained criticism of

Samurai Archives

* East Asia Institute,

Further reading/bibliography

{{Authority control {{DEFAULTSORT:Kumazawa, Banzan Okayama Prefecture Japanese Confucianists 17th-century Japanese philosophers 1619 births 1691 deaths People from Kyoto People from Shimogyō, Kyoto Writers of the Edo period Japanese scholars of Yangming

was a Japanese Confucian. He learned Yangmingism from Nakae Tōju and served Ikeda Mitsumasa, the lord of Bizen Province. In his later years, he was imprisoned for writing ''Daigaku Wakumon'', which contained criticism of

was a Japanese Confucian. He learned Yangmingism from Nakae Tōju and served Ikeda Mitsumasa, the lord of Bizen Province. In his later years, he was imprisoned for writing ''Daigaku Wakumon'', which contained criticism of Tokugawa shogunate

The Tokugawa shogunate, also known as the was the military government of Japan during the Edo period from 1603 to 1868.

The Tokugawa shogunate was established by Tokugawa Ieyasu after victory at the Battle of Sekigahara, ending the civil wars ...

politics.

Name

His childhood name (yōmei) was , hisimina

in modern times consist of a family name (surname) followed by a given name. Japanese names are usually written in kanji, where the pronunciation follows a special set of rules. Because parents when naming children, and foreigners when adoptin ...

was . His common name ( azana) was , and he was commonly known by the personal names ( tsūshō) as or . His most common courtesy name ( gō) was . His surname "Kumazawa" (熊沢) was changed to that of "Shigeyama" (蕃山) in 1660 and the latter, read in Sino-Japanese as "Banzan", became his posthumous courtesy title, by which even now he is commonly known.

Yōmeigaku

Yōmeigaku is the Japanese term for a school of Neo-Confucianism associated with its founder, the Chinese philosopher Wang Yangming, characterised by introspection and activism, and which exercised a profound influence on Japanese revisions of Confucian political and moral theory in Japan during theEdo period

The , also known as the , is the period between 1600 or 1603 and 1868 in the history of Japan, when the country was under the rule of the Tokugawa shogunate and some 300 regional ''daimyo'', or feudal lords. Emerging from the chaos of the Sengok ...

.

Life

Early life

He was born in Kyoto Inari (nowShimogyō-ku, Kyoto

is one of the eleven wards in the city of Kyoto, in Kyoto Prefecture, Japan. First established in 1879, it has been merged and split, and took on its present boundaries in 1955, with the establishment of a separate Minami-ku.

Kyoto Tower a ...

), the eldest son of six children. His father, a rōnin

In feudal Japan to early modern Japan (1185–1868), a ''rōnin'' ( ; , , 'drifter' or 'wandering man', ) was a samurai who had no lord or master and in some cases, had also severed all links with his family or clan. A samurai became a ''rō ...

, was called (1590–1680). He had served under two ''daimyō

were powerful Japanese magnates, feudal lords who, from the 10th century to the early Meiji era, Meiji period in the middle 19th century, ruled most of Japan from their vast hereditary land holdings. They were subordinate to the shogun and no ...

'' but was masterless at the time of Banzan’s birth. Banzan’s grandfather had served Oda Nobunaga

was a Japanese ''daimyō'' and one of the leading figures of the Sengoku period, Sengoku and Azuchi-Momoyama periods. He was the and regarded as the first "Great Unifier" of Japan. He is sometimes referred as the "Demon Daimyō" and "Demo ...

(1534–1582) and Sakuma Jinkurô (1556–1631). His mother was called and was the daughter of a samurai named , a samurai

The samurai () were members of the warrior class in Japan. They were originally provincial warriors who came from wealthy landowning families who could afford to train their men to be mounted archers. In the 8th century AD, the imperial court d ...

serving the daimyo of Mito, Tokugawa Yorifusa. At the age of eight, Banzan was adopted by his maternal grandfather and took from him the surname of Kumazawa.

Leaving to study under Nakae Tōju

In 1634, through the introduction of , a fudai vassal of the Tokugawa, he went to serve as a page under , the daimyo of the Okayama Domain in Bizen Province. He left the Ikeda household for a time, returning to his grandfather's home in Kirihara,Ōmi Province

was a Provinces of Japan, province of Japan, which today comprises Shiga Prefecture. It was one of the provinces that made up the Tōsandō Circuit (subnational entity), circuit. Its nickname is . Under the ''Engishiki'' classification system, ...

(now Ōmihachiman).

Time in the Okayama Domain

In 1645, again with the recommendation of the Kyōgoku family, he went to work in the Okayama Domain. As Mitsumasa's thinking leaned towards Yōmeigaku, he made much use of Banzan, valuing him for having studied under Tōju. Banzan worked mainly in the Han school called , whose name means "Flowerfield Teaching Place". This school opened in 1641, making it one of the first in Japan. In 1647 Banzan became an aide, with an of 300koku

The is a Chinese-based Japanese unit of volume. One koku is equivalent to 10 or approximately , or about of rice. It converts, in turn, to 100 shō and 1,000 gō. One ''gō'' is the traditional volume of a single serving of rice (before co ...

. In 1649 he went with Mitsumasa to Edo.

In 1650, he was promoted to be the head of a . In 1651, he drafted the regulations for a , literally "flower garden club", a place for the education of common people. This was the initial incarnation of the first school in Japan for educating commoners, which opened in 1670, after Banzan had left the service of his domain. In 1654, when the Bizen plains were assailed by floods and large-scale famine, he put all his energies into assisting Mitsumasa with relief efforts. Together with , he worked as an aide to Mitsumasa, helping to establish the start of a domain government in Okayama Domain. He worked to produce fully developed strategies on agriculture, including ways of providing relief to small-scale farmers and land engineering projects to manage mountains and rivers. However, his daring reforms of domain government brought him into opposition with the traditionalist . In addition, while Banzan was a follower of Yōmeigaku, the official philosophy of the Edo shogunate

, officially , was the title of the military rulers of Japan during most of the period spanning from 1185 to 1868. Nominally appointed by the Emperor, shoguns were usually the de facto rulers of the country, except during parts of the Kamak ...

was a different form of Neo-Confucianism, . Banzan was criticised by figures such as and . In fact, Banzan was the first in a series of notable neo-Confucianists who would find themselves confronting the evolving critical powers of the Hayashi clan of scholars.

For this reason, Banzan was left with no choice but to leave the service of Okayama Castle and live in hiding in , Wake District (now Shigeyama, Bizen, Okayama). The name "Banzan" derives from the word "Shigeyama". The location where his home was is , Okayama-shi.

Time out of power and later life

Eventually, in 1657, unable to withstand the pressure from the shogunate and the domain leaders, he left Okayama Domain. In 1658, he moved to Kyoto and opened a private juku (school). In 1660, at the request of , he travelled to Tateda, Oita, and gave directions on land management. In 1661, his fame grew, and he again came to be under the surveillance of the shogunate, and was eventually driven out of Kyoto by , aide to the head of the . In 1667, he escaped to Yoshinoyama, Yamato Province (now Yoshino, Nara). He then moved to live in hiding in , Yamashiro Province (now Kizugawa, Kyoto). In 1669, on orders from the shogunate, he was put under the control of , the head of the , Harima Province. In 1683, as Nobuyuki was transferred to Kōriyama Province, he moved to , Yamato Province (now Yamatokōriyama, Nara). In 1683, he received the invitation of the , but refused it. After serving the Okayama District, in his days outside public service, he often wrote, and criticised the policies of the shogunate, particularly , (the policy forbidding those outside the samurai class to arm themselves), and the hereditary system. He was also critical of the government of Okayama Domain. Banzan's goal was to reform the Japanese government by advocating the adoption of a political system based on merit rather than heredity and the employment of political principles to reinforce the merit system. In 1687, he was put under the control of , head of , , and heir to Matsudaira Nobuyuki, and ordered to remain inside Koga Castle. In 1691 the rebellious Confucian became ill and died within Koga Castle at the age of 74.After his death

Banzan's remains were buried by Tadayuki with much ceremony at {{nihongo, Keienji, 鮭延寺, in {{nihongo, Ōtsutsumi, 大堤,Koga, Ibaraki

is a city located in Ibaraki Prefecture, Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 137,512 in 58,276 households and a population density of 1113 persons per km². The percentage of the population aged over 65 was 28.98%. The total area of ...

. The initial inscription on the tombstone was {{nihongo, "grave of Sokuyūken", 息游軒墓, using his posthumous name, but this was later changed to {{nihongo, "grave of Kumazawa Sokuyūken Hatsukei", 熊沢息游軒伯継墓.

In the Bakumatsu

were the final years of the Edo period when the Tokugawa shogunate Meiji Restoration, ended. Between 1853 and 1867, under foreign diplomatic and military pressure, Japan ended its isolationist foreign policy known as and changed from a Feudali ...

period, Banzan's philosophy came back into the spotlight, greatly influencing the structure of government. It was favoured by, among others, {{nihongo, Fujita Tōko, 藤田東湖 and {{nihongo, Yoshida Shōin, 吉田松陰, becoming a motivating force in the toppling of the shogunate government. Katsu Kaishū praised Banzan as "a hero in Confucian robes".

Outside the realm of politics, Banzan would in time become something of a cultural hero because, while attending to actions and words which demonstrated an enduring concern for commoners and the poor. He was praised for resistance to the imposition of corrupt politics and bureaucratic burdens on ordinary people.Najita, p. 115.

In 1910, the Meiji government honoured Banzan with the title of {{nihongo, Upper Fourth Rank, 正四位, in recognition of his contribution to the development of learning in the Edo period.

Writings

*{{nihongo, Shūgi Washo, 集義和書 *{{nihongo, Shūgi Gaisho, 集義外書 *{{nihongo, Daigaku Wakumon, 大学或問Lineage

*{{nihongo, Nojiri family, 野尻氏 {{nihongo, Shōgen, 将監 — {{nihongo, Kyūbē Shigemasa, 久兵衛重政 — {{nihongo, Tōbei Kazutoshi, 藤兵衛一利 — Banzan *{{nihongo, Kumazawa family, 熊沢氏 {{nihongo, Shinsaemon Hiroyuki, 新左衛門廣幸 — {{nihongo, Yasaemon Hirotsugu, 八左衛門廣次 — {{nihongo, Heisaburō Moritsugu, 平三郎守次 — {{nihongo, Hansaemon Morihisa, 半右衛門守久 — {{nihongo, Kamejo, 亀女 — BanzanSee also

* Kobe temple -- {{nihongo, Taisanji, 太山寺 * List of ConfucianistsReferences

{{ReflistSources

* Collins, Randall. (1998). ''The Sociology of Philosophies: A Global Theory of Intellectual Change.'' Cambridge:Harvard University Press

Harvard University Press (HUP) is an academic publishing house established on January 13, 1913, as a division of Harvard University. It is a member of the Association of University Presses. Its director since 2017 is George Andreou.

The pres ...

. {{ISBN, 978-0-674-81647-3 (cloth) {{ISBN, 978-0-674-00187-9 (paper)

* McMullen, James. (1999). ''Idealism, Protest and the Tale of Genji: The Confucianism of Kumazawa Banzan (1619-91).'' Oxford: Oxford University Press

Oxford University Press (OUP) is the publishing house of the University of Oxford. It is the largest university press in the world. Its first book was printed in Oxford in 1478, with the Press officially granted the legal right to print books ...

. {{ISBN, 978-0-19-815251-4 (cloth)

* Najita, Tetsuo. (1980). ''Japan: The Intellectual Foundations of Modern Japanese Politics.'' Chicago: University of Chicago Press

The University of Chicago Press is the university press of the University of Chicago, a Private university, private research university in Chicago, Illinois. It is the largest and one of the oldest university presses in the United States. It pu ...

. {{ISBN, 978-0-226-56803-4

* Vaporis, Constantine Nomikos. (2019). ''Samurai. An Encyclopedia of Japan’s Cultured Warriors.'' Santa Barbara, California: ABC-Clio, {{ISBN, 978-1-4408-4270-2

External links

Samurai Archives

* East Asia Institute,

University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209, the University of Cambridge is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, wo ...

Further reading/bibliography

{{Authority control {{DEFAULTSORT:Kumazawa, Banzan Okayama Prefecture Japanese Confucianists 17th-century Japanese philosophers 1619 births 1691 deaths People from Kyoto People from Shimogyō, Kyoto Writers of the Edo period Japanese scholars of Yangming