Kuban Cossacks on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Kuban Cossacks (; ), or Kubanians (, ''kubantsy''; , ''kubantsi''), are

Kuban Cossacks (; ), or Kubanians (, ''kubantsy''; , ''kubantsi''), are

During the

During the

Many traditions of the Zaporozhian Cossacks continued in the Black Sea Cossacks, such as the formal election of the host administration, but in some cases, new traditions replaced the old. Instead of a central Sich, a defence line was formed from the Kuban River Black Sea inlet to the Bolshaya Laba River inlet. The land north of this line was settled with villages called

Many traditions of the Zaporozhian Cossacks continued in the Black Sea Cossacks, such as the formal election of the host administration, but in some cases, new traditions replaced the old. Instead of a central Sich, a defence line was formed from the Kuban River Black Sea inlet to the Bolshaya Laba River inlet. The land north of this line was settled with villages called

As the years went by, the Black Sea Cossacks continued its systematic penetrations into the mountainous regions of the Northern Caucasus. Taking an active part in the finale of the Russian conquest of the Northern Caucasus, they settled the regions each time these were conquered. To aid them, a total of 70 thousand additional ex-Zaporozhians from the Bug,

As the years went by, the Black Sea Cossacks continued its systematic penetrations into the mountainous regions of the Northern Caucasus. Taking an active part in the finale of the Russian conquest of the Northern Caucasus, they settled the regions each time these were conquered. To aid them, a total of 70 thousand additional ex-Zaporozhians from the Bug,

Until 1914 the Kuban Cossack Host wore a full dress uniform comprising a dark grey/black

Until 1914 the Kuban Cossack Host wore a full dress uniform comprising a dark grey/black

In March 1918, after Lavr Kornilov's successful offensive, the Kuban Rada placed itself under his authority. With his death in June 1918, however, a federative union was signed with the Ukrainian government of Hetman Pavlo Skoropadsky after which many Cossacks left to return home or defected to the Bolsheviks. Additionally, there was an internal struggle among the Kuban cossacks over loyalty towards

In March 1918, after Lavr Kornilov's successful offensive, the Kuban Rada placed itself under his authority. With his death in June 1918, however, a federative union was signed with the Ukrainian government of Hetman Pavlo Skoropadsky after which many Cossacks left to return home or defected to the Bolsheviks. Additionally, there was an internal struggle among the Kuban cossacks over loyalty towards

Russian Volunteers in the German Wehrmacht in WWII

/ref> While there were several smaller Cossack detachments in the Wehrmacht since 1941, the 1st Cossack Division made up of Don, Terek and Kuban Cossacks was formed in 1943. This division was further augmented by the 2nd Cossack Cavalry Division formed in December 1944. Both divisions participated in hostilities against Tito's partisans in Yugoslavia. In February 1945, both Cossack Divisions were transferred into the

Because of the unique migration pattern that the original

Because of the unique migration pattern that the original

URL

/ref>

Official website

Official section about Cossackdom at the Krasnodar Kray administration's site

Unofficial website

{{Authority control Ethnic groups in Russia Cossack hosts Kuban oblast Peoples of the Caucasus Ukrainian diaspora in Russia

Kuban Cossacks (; ), or Kubanians (, ''kubantsy''; , ''kubantsi''), are

Kuban Cossacks (; ), or Kubanians (, ''kubantsy''; , ''kubantsi''), are Cossacks

The Cossacks are a predominantly East Slavic languages, East Slavic Eastern Christian people originating in the Pontic–Caspian steppe of eastern Ukraine and southern Russia. Cossacks played an important role in defending the southern borde ...

who live in the Kuban

Kuban ( Russian and Ukrainian: Кубань; ) is a historical and geographical region in the North Caucasus region of southern Russia surrounding the Kuban River, on the Black Sea between the Don Steppe, the Volga Delta and separated fr ...

region of Russia

Russia, or the Russian Federation, is a country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia. It is the list of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the world, and extends across Time in Russia, eleven time zones, sharing Borders ...

. Most of the Kuban Cossacks are descendants of different major groups of Cossacks who were re-settled to the western Northern Caucasus in the late 18th century (estimated 230,000 to 650,000 initial migrants). The western part of the region ( Taman Peninsula and adjoining region to the northeast) was settled by the Black Sea Cossack Host

Black Sea Cossack Host (), also known as Chernomoriya (), was a Cossack host of the Russian Empire created in 1787 in southern Ukraine from former Zaporozhian Cossacks.Azarenkova et al., pp. 9ff. In the 1790s, the host was re-settled to the ...

who were originally the Zaporozhian Cossacks

The Zaporozhian Cossacks (in Latin ''Cossacorum Zaporoviensis''), also known as the Zaporozhian Cossack Army or the Zaporozhian Host (), were Cossacks who lived beyond (that is, downstream from) the Dnieper Rapids. Along with Registered Cossa ...

of Ukraine

Ukraine is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the List of European countries by area, second-largest country in Europe after Russia, which Russia–Ukraine border, borders it to the east and northeast. Ukraine also borders Belarus to the nor ...

, from 1792. The eastern and southeastern part of the host was previously administered by the Khopyour and Kuban regiments of the Caucasus Line Cossack Host and Don Cossacks

Don Cossacks (, ) or Donians (, ), are Cossacks who settled along the middle and lower Don River (Russia), Don. Historically, they lived within the former Don Cossack Host (, ), which was either an independent or an autonomous democratic rep ...

, who were re-settled from the Don from 1777.

The Kuban Cossack Host

A Cossack host (; , ''kazachye voysko''), sometimes translated as Cossack army, was an administrative subdivision of Cossacks in the Russian Empire. Earlier the term ''voysko'' ( host, in a sense as a doublet of ''guest'') referred to Cossack o ...

(Кубанское казачье войско), the administrative and military unit composed of Kuban Cossacks, formed in 1860 and existed until 1918. During the Russian Civil War

The Russian Civil War () was a multi-party civil war in the former Russian Empire sparked by the 1917 overthrowing of the Russian Provisional Government in the October Revolution, as many factions vied to determine Russia's political future. I ...

, the Kuban Cossacks proclaimed the Kuban People's Republic, and played a key role in the southern theatre of the conflict. The Kuban Cossacks suffered heavily during the Soviet policy of decossackization

De-Cossackization () was the Bolshevik policy of systematic repression against the Cossacks in the former Russian Empire between 1919 and 1933, especially the Don and Kuban Cossacks in Russia, aimed at the elimination of the Cossacks as a dist ...

between 1917 and 1933. Hence, during the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, Cossacks fought both for the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

and against them with the German Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the German Army (1935–1945), ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmac ...

. The modern Kuban Cossack Host was re-established in 1990 at the fall of the Soviet Union.

Formation history of the Kuban Cossack Host

Although Cossacks lived in the region prior to the late 18th century (one theory of Cossack origin traces their lineage to the ancient Kasog peoples who populated the Kuban in 9th-13th centuries), the landscape prevented permanent habitation. Modern Kuban Cossacks claim 1696 as their foundation year, when the Don Cossacks from the Khopyor took part in Peter'sAzov campaigns

Azov (, ), previously known as Azak (Turki/Cuman language, Kypchak: ),

is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, town in Rostov Oblast, Russia, situated on the Don River (Russia), Don River just from the Sea of Azov, which derives its name ...

. Sporadic raids reached out into the land, which was partially populated by the Nogay, though territorially part of the Crimean khanate

The Crimean Khanate, self-defined as the Throne of Crimea and Desht-i Kipchak, and in old European historiography and geography known as Little Tartary, was a Crimean Tatars, Crimean Tatar state existing from 1441 to 1783, the longest-lived of th ...

. In 1784 the lower Kuban passed to Russia, after which its colonisation became an important step in the Empire's expansion.

Black Sea Cossacks

In a different part of southeastern Europe, on the middleDnieper

The Dnieper or Dnepr ( ), also called Dnipro ( ), is one of the major transboundary rivers of Europe, rising in the Valdai Hills near Smolensk, Russia, before flowing through Belarus and Ukraine to the Black Sea. Approximately long, with ...

in what is now Ukraine, lived the Zaporozhian Cossacks

The Zaporozhian Cossacks (in Latin ''Cossacorum Zaporoviensis''), also known as the Zaporozhian Cossack Army or the Zaporozhian Host (), were Cossacks who lived beyond (that is, downstream from) the Dnieper Rapids. Along with Registered Cossa ...

. By the late 18th century, however, their combat ability was greatly reduced. With their traditional adversaries, the Crimean Khanate

The Crimean Khanate, self-defined as the Throne of Crimea and Desht-i Kipchak, and in old European historiography and geography known as Little Tartary, was a Crimean Tatars, Crimean Tatar state existing from 1441 to 1783, the longest-lived of th ...

and the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, also referred to as Poland–Lithuania or the First Polish Republic (), was a federation, federative real union between the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania ...

, now all but defunct, the Russian administration saw little military use for them. The Zaporozhian Sich, however, represented a safe haven for runaway serfs, where the state authority did not extend, and often took part in rebellions which were constantly breaking out in Ukraine. Another problem for the imperial Russian government was the Cossacks' resistance to colonization of lands the government considered theirs. In 1775, after numerous attacks on Serbian colonisers, the Russian Empress Catherine the Great

Catherine II. (born Princess Sophie of Anhalt-Zerbst; 2 May 172917 November 1796), most commonly known as Catherine the Great, was the reigning empress of Russia from 1762 to 1796. She came to power after overthrowing her husband, Peter I ...

had Grigory Potemkin

Prince Grigory Aleksandrovich Potemkin-Tauricheski (A number of dates as late as 1742 have been found on record; the veracity of any one is unlikely to be proved. This is his "official" birth-date as given on his tombstone.) was a Russian mi ...

destroy the Zaporozhian Host. The operation was carried out by General Pyotr Tekeli.

The Zaporozhians scattered; some (five thousand men or 30% of the host) fled to the Ottoman-controlled Danube

The Danube ( ; see also #Names and etymology, other names) is the List of rivers of Europe#Longest rivers, second-longest river in Europe, after the Volga in Russia. It flows through Central and Southeastern Europe, from the Black Forest sou ...

area. Others joined the Imperial Russian Husar and Dragoon

Dragoons were originally a class of mounted infantry, who used horses for mobility, but dismounted to fight on foot. From the early 17th century onward, dragoons were increasingly also employed as conventional cavalry and trained for combat wi ...

regiments, while most turned to local farming and trade.

A decade later, the Russian administration was forced to reconsider its decision, with the escalation of tension with the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

. In 1778 the Turkish sultan offered the exiled Zaporozhians the chance to build a new Danubian Sich. Potemkin suggested that the former commanders Antin Holovaty, Zakhary Chepiha and Sydir Bily round the former Cossacks into a ''Host of the loyal Zaporozhians'' in 1787.

The new host played a crucial role in the Russo-Turkish War (1787–1792), and for their loyalty and service the Russian Empress rewarded them with eternal use of the Kuban, then inhabited by Nogai remnants, and in the cause of the Caucasus War a crucial progress in further pushing the Russian line into Circassia

Circassia ( ), also known as Zichia, was a country and a historical region in . It spanned the western coastal portions of the North Caucasus, along the northeastern shore of the Black Sea. Circassia was conquered by the Russian Empire during ...

. Renamed the Black Sea Cossack Host

Black Sea Cossack Host (), also known as Chernomoriya (), was a Cossack host of the Russian Empire created in 1787 in southern Ukraine from former Zaporozhian Cossacks.Azarenkova et al., pp. 9ff. In the 1790s, the host was re-settled to the ...

, a total of 25,000 men made the migration in 1792-93.

On the Russian frontier (1777–1860)

During the

During the Russo-Turkish War (1768–1774)

The Russo-Turkish wars ( ), or the Russo-Ottoman wars (), began in 1568 and continued intermittently until 1918. They consisted of twelve conflicts in total, making them one of the longest series of wars in the history of Europe. All but four of ...

, the Don Cossacks

Don Cossacks (, ) or Donians (, ), are Cossacks who settled along the middle and lower Don River (Russia), Don. Historically, they lived within the former Don Cossack Host (, ), which was either an independent or an autonomous democratic rep ...

on the Khopyor River took part in the campaign, and in 1770 – then numbering four settlements – requested to form a regiment. Owing to their service in the war, on 6 October 1774 Catherine the Great

Catherine II. (born Princess Sophie of Anhalt-Zerbst; 2 May 172917 November 1796), most commonly known as Catherine the Great, was the reigning empress of Russia from 1762 to 1796. She came to power after overthrowing her husband, Peter I ...

issued a manifesto granting their request.

The end of the war and the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca

The Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (; ), formerly often written Kuchuk-Kainarji, was a peace treaty signed on , in Küçük Kaynarca (today Kaynardzha, Bulgaria and Cuiugiuc, Romania) between the Russian Empire and the Ottoman Empire, ending the R ...

brought Russia's frontiers south from the Kuban River

The Kuban is a river in Russia that flows through the Western Caucasus and drains into the Sea of Azov. The Kuban runs mostly through Krasnodar Krai for , but also in the Karachay–Cherkess Republic, Stavropol Krai and the Republic of Adygea. ...

's entry into the Azov Sea along its right bank and right to the bend of the Terek River. This created a 500- verst undefended border, and in the summer of 1777 the Khopyor regiment – in addition to the remnants of the Volga Cossacks and a Vladimir Dragoon

Dragoons were originally a class of mounted infantry, who used horses for mobility, but dismounted to fight on foot. From the early 17th century onward, dragoons were increasingly also employed as conventional cavalry and trained for combat wi ...

regiment – were re-settled in the Northern Caucasus to build the Azov

Azov (, ), previously known as Azak ( Turki/ Kypchak: ),

is a town in Rostov Oblast, Russia, situated on the Don River just from the Sea of Azov, which derives its name from the town. The population is

History

Early settlements in the vici ...

- Mozdok defence line. This marked the start of the Caucasus War, which would continue for almost 90 years.

The Khopyor regiment was responsible for the western flank of the line. In 1778-1782, Khopyor Cossacks founded four stanitsa

A stanitsa or stanitza ( ; ), also spelled stanycia ( ) or stanica ( ), was a historical administrative unit of a Cossack host, a type of Cossack polity that existed in the Russian Empire.

Etymology

The Russian word is the diminutive of the word ...

s: Stavropolskaya (next to the fortress of Stavropol

Stavropol (, ), known as Voroshilovsk from 1935 until 1943, is a city and the administrative centre of Stavropol Krai, in southern Russia. As of the 2021 Census, its population was 547,820, making it one of Russia's fastest growing cities.

E ...

, established on 22 October 1777), Moskovskaya, Donskaya and Severnaya – with approximately 140 Cossack families in each. In 1779, the Khopyor regiment was given its own district. The conditions were desperate as the Circassians would mount almost daily raids on the Russian positions. In 1825-1826 the regiment began its first expansions, pushing westwards to the bend of the Kuban River

The Kuban is a river in Russia that flows through the Western Caucasus and drains into the Sea of Azov. The Kuban runs mostly through Krasnodar Krai for , but also in the Karachay–Cherkess Republic, Stavropol Krai and the Republic of Adygea. ...

and founding five new stanitsas (the so-called new-Kuban line: Barsukovskaya, Nevinnomysskaya, Belomechetskaya, Batalpashinskaya (modern Cherkessk), Bekeshevskaya and Karantynnaya (currently Suvorovskaya). In 1828 the Khopyor Cossacks participated in the conquest of Karachay and became part of the first Russian expedition to reach the summit of Elbrus

Mount Elbrus; ; is the highest mountain in Russia and Europe. It is a dormant volcano, dormant stratovolcano rising above sea level, and is the highest volcano in Eurasia, as well as the List of mountain peaks by prominence, tenth-most promi ...

in 1829.

However, the Russian position in the Caucasus was desperate, and to ease administration in 1832 military reform united ten regiments from the mouth of the Terek River all the way to the Khopyor in the western Kabarda, forming a single Caucasus Line Cossack Host. The Khopyor regiment was also given several civilian settlements, raising its manpower to 12,000. With the further advance to the Laba River the Khopyor district was split into two regiments, and Spokoynaya, Ispravnaya, Podgornaya, Udobnaya, Peredovaya, Storozhevaya formed the Laba line.

Zaporozhets beyond the Kuban River

stanitsa

A stanitsa or stanitza ( ; ), also spelled stanycia ( ) or stanica ( ), was a historical administrative unit of a Cossack host, a type of Cossack polity that existed in the Russian Empire.

Etymology

The Russian word is the diminutive of the word ...

s. The administrative centre of Yekaterinodar (literally "Catherine's gift") was built. The Black Sea Cossacks sent men to many major campaigns at the Russian Empire's demand, such as the suppression of the Polish Kościuszko Uprising

The Kościuszko Uprising, also known as the Polish Uprising of 1794, Second Polish War, Polish Campaign of 1794, and the Polish Revolution of 1794, was an uprising against the Russian and Prussian influence on the Polish–Lithuanian Common ...

in 1794, the ill-fated Persian Expedition of 1796

The Persian expedition of Catherine the Great of 1796 , like the Persian expedition of Peter the Great (1722–1723), was one of the Russo-Persian Wars of the 18th century which did not entail any lasting consequences for either belligerent. ...

where nearly half of the Cossacks died from hunger and disease, and sent the 9th plastun (infantry) and 1st joint cavalry regiments as well as the first Leib Guard

The Russian Imperial Guard, officially known as the Leib Guard ( ''Leyb-gvardiya'', from German language, German ''Leib'' "body"; cf. Lifeguard (military), Life Guards / Bodyguard), were combined Imperial Russian Army forces units serving as cou ...

s (elite) sotnia

A sotnia ( Ukrainian and , ) was a military unit and administrative division in some Slavic countries.

Sotnia, deriving back to 1248, has been used in a variety of contexts in both Ukraine and Russia to this day. It is a helpful word to create ...

to aid the Russian Army in the Patriotic War of 1812

The French invasion of Russia, also known as the Russian campaign (), the Second Polish War, and in Russia as the Patriotic War of 1812 (), was initiated by Napoleon with the aim of compelling the Russian Empire to comply with the continent ...

. The new host participated in the Russo-Persian War (1826–1828)

The Russo-Persian War of 1826–1828 was the last major military conflict between the Russian Empire and Qajar Iran, which was fought over territorial disputes in the South Caucasus region.

Initiated by Russian expansionist aims and intensifie ...

where they stormed the last remaining Ottoman bastion of the northern Black Sea coast, the fortress of Anapa

Anapa (, , ) is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, town in Krasnodar Krai, Russia, located on the northern coast of the Black Sea near the Sea of Azov. As of the 2021 Russian census, it had a population of 81,863. It is one of the largest ...

, in 1828. In the course of the Crimean War

The Crimean War was fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, the Second French Empire, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the Kingdom of Sardinia (1720–1861), Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont fro ...

of 1853 to 1856, the Cossacks foiled any attempts of allied landing on the Taman Peninsula, whilst the 2nd and 5th plastun battalions took part in the Defence of Sevastopol.

In the land they left behind, the Buh Cossacks were able to provide a strong buffer from the Danubian Sich. After the Russo-Turkish War (1828–1829)

The Russo-Turkish War of 1828–1829 resulted from the Greek War of Independence of 1821–1829; war broke out after the Ottoman Sultan Mahmud II closed the Dardanelles to Russian Empire , Russian ships and in November 1827 revoked the 18 ...

most of the Danube Cossacks officially turned themselves over and under amnesty were resettled between the Mariupol

Mariupol is a city in Donetsk Oblast, Ukraine. It is situated on the northern coast (Pryazovia) of the Sea of Azov, at the mouth of the Kalmius, Kalmius River. Prior to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, it was the tenth-largest city in the coun ...

and Berdyansk, forming the Azov Cossack Host.

Expansion

As the years went by, the Black Sea Cossacks continued its systematic penetrations into the mountainous regions of the Northern Caucasus. Taking an active part in the finale of the Russian conquest of the Northern Caucasus, they settled the regions each time these were conquered. To aid them, a total of 70 thousand additional ex-Zaporozhians from the Bug,

As the years went by, the Black Sea Cossacks continued its systematic penetrations into the mountainous regions of the Northern Caucasus. Taking an active part in the finale of the Russian conquest of the Northern Caucasus, they settled the regions each time these were conquered. To aid them, a total of 70 thousand additional ex-Zaporozhians from the Bug, Yekaterinoslav

Dnipro is Ukraine's fourth-largest city, with about one million inhabitants. It is located in the eastern part of Ukraine, southeast of the Ukrainian capital Kyiv on the Dnieper River, Dnipro River, from which it takes its name. Dnipro is t ...

, and finally the Azov Cossack Host migrated there in the mid 19th century. All three of the former were necessary to be removed to vacate space for the colonisation of New Russia, and with the increasing weakness of the Ottoman Empire as well as the formation of independent buffer states in the Balkans, the need for further Cossack presence had ended. They made the migration to the Kuban in 1860. Separating the ethnic Ukrainian Black Sea Cossacks from the Caucasian mountain tribes were the Caucasus Line Cossack Host, ethnic Russian Cossacks from the Don region. Although both groups lived in the general Kuban region, they did not integrate with each other.Anna Procyk. (1995). ''Russian Nationalism and Ukraine: The Nationality Policy of the Volunteer Army During the Civil War'' Toronto: Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies at University of Toronto, pg. 36

Apogee of the Kuban Host

The new Host grew to be the second largest in Russia. The Kuban Cossacks continued to make an active part in the Russian affairs of the 19th century starting from the finale of the Russian-Circassian War which ceased shortly after the hosts' formation. A small group took part in the 1873 conquest that brought theKhanate of Khiva

The Khanate of Khiva (, , uz-Latn-Cyrl, Xiva xonligi, Хива хонлиги, , ) was a Central Asian polity that existed in the historical region of Khwarazm, Khorezm from 1511 to 1920, except for a period of Afsharid Iran, Afsharid occupat ...

under Russian control. Their largest military campaign was the Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878)

The Russo-Turkish War (1877–1878) was a conflict between the Ottoman Empire and a coalition led by the Russian Empire which included United Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia, Romania, Principality of Serbia, Serbia, and Principality of ...

, on both the Balkan and the Caucasus fronts. The latter in particular was a strong contribution as the Kuban Cossacks made 90% of the Russian cavalry. Famous achievements in the numerous Battles of Shipka, the defence of Bayazet and finally, in decisive and victorious Battle of Kars where the Cossacks were the first to enter. Three Kuban Cossack regiments took part in the storming of Geok Tepe in Turkmenistan in 1881. During the Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War (8 February 1904 – 5 September 1905) was fought between the Russian Empire and the Empire of Japan over rival imperial ambitions in Manchuria and the Korean Empire. The major land battles of the war were fought on the ...

(1904–1905), the host mobilised six cavalry regiments, five plastun battalions and one battery to the distant region of Russia.

The Cossacks also carried out the second strategical objective, the colonisation of the Kuban land. In total, the host owned more than six million tithes, of which 5.7 million belonged to the stanitsas, with the remaining in the reserve or in private hands of Cossack officers and officials. Upon reaching the age of 17, a Cossack would be given between 16 and 30 tithes for cultivation and personal use. With the natural growth of the population, the average land that a Cossack owned decreased from 23 tithes in the 1860s to 7.6 in 1917. Such arrangements, however ensured that the colonisation and the cultivation would be very rational.

The military purpose of the Kuban was echoed in its administration pattern. Rather than a traditional Imperial Guberniya (governorate) with uyezd

An uezd (also spelled uyezd or uiezd; rus, уе́зд ( pre-1918: уѣздъ), p=ʊˈjest), or povit in a Ukrainian context () was a type of administrative subdivision of the Grand Duchy of Moscow, the Tsardom of Russia, the Russian Empire, the R ...

s (districts), the territory was administered by the Kuban Oblast which was split into (regions, which in 1888 counted seven). Each would have its own which in turn would be split into and . The (commander) for each region was not only responsible for the military preparation of the Cossacks, but for the local administration duties. Local Stanitsa and Khutor atamans were elected, but approved by the of the . These, in turn, were appointed by the supreme of the host, who was in turn appointed directly by the Russian Emperor. Prior to 1870, this system of legislature in the Oblast remained a robust military one and all legal decisions were carried out by the and two elected judges. Afterwards, however, the system was bureaucratised and the judicial functions became independent of the .

The more liberal policy of the Kuban was directly mirrored in the living standards of the people. One of the central features of this was education. Indeed, the first schools were known to have existed since the migration of the Black Sea Cossacks, and by 1860, the host had one male high school and 30 elementary schools. In 1863, the first periodical Кубанские войсковые ведомсти (''Kubanskiye voiskovye vedomsti'') began printing, and two years later the host's library was opened in Yekaterinodar. In all, by 1870, the number of schools in rural stanitsas increased to 170. Compared with the rest of the Russian Empire, by the start of the 20th century the Oblast had a very high literacy rate of 50% and each year up to 30 students from Cossack families (again a rate unmatched by any other rural province) were sent to study in the higher education establishments of Russia.

During the early twentieth century contacts between Kuban and Ukraine were established and clandestine Ukrainian organizations appeared in Kuban.

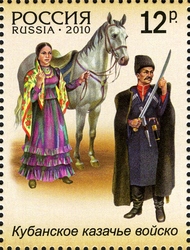

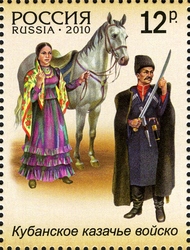

Uniform and equipment

Until 1914 the Kuban Cossack Host wore a full dress uniform comprising a dark grey/black

Until 1914 the Kuban Cossack Host wore a full dress uniform comprising a dark grey/black kaftan

A kaftan or caftan (; , ; , ; ) is a variant of the robe or tunic. Originating in Asia, it has been worn by a number of cultures around the world for thousands of years. In Russian usage, ''kaftan'' instead refers to a style of men's long suit ...

(knee length collarless coat) with red shoulder straps and braiding on the wide cuffs. Ornamental containers (''gaziri'') which had originally contained single loading measures of gunpowder for muzzle-loading muskets, were worn on the breasts of the kaftans. The kaftan had an open front, showing a red waistcoat. Wide grey trousers were worn, tucked into soft leather boots without heels. Officers wore silver epaulettes, braiding and ferrule

A ferrule (a corruption of Latin ' "small bracelet", under the influence of ' "iron") is any of a number of types of objects, generally used for fastening, joining, sealing, or reinforcement. They are often narrow circular rings made from m ...

s. This Caucasian national dress was also worn by the Terek Cossack Host but in different facing colors. Tall black fur hats were worn on all occasions with red cloth tops and (for officers) silver lace. A white metal scroll was worn on the front of the fur hat. A whip was used instead of spurs. Prior to 1908, individual cossacks from all Hosts were required to provide their own uniforms (together with horses, Caucasian saddles and harness). On active service during World War I the Kuban Cossacks retained their distinctive dress but with a black waistcoat replacing the conspicuous red one and without the silver ornaments or red facings of full dress. A black felt cloak () was worn in bad weather both in peace-time and on active service.

The 200 Kuban and 200 Terek Cossacks of the Imperial Escort (''Konvoi'') wore a special gala uniform; including a scarlet kaftan edged with yellow braid and a white waistcoat. Officers had silver braiding on their coats and epaulettes. A dark coloured kaftan was issued for ordinary duties together with a red waistcoat.

Russian Revolution and Civil War

During theRussian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution, social change in Russian Empire, Russia, starting in 1917. This period saw Russia Dissolution of the Russian Empire, abolish its mona ...

and resulting Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

, the Cossacks found themselves conflicted in their loyalties. In October 1917, the Kuban Soviet Republic and the Kuban Rada were formed simultaneously, with both proclaiming their right to rule the Kuban. Shortly after the Rada declared a Kuban National Republic, but this was soon dispersed by Bolshevik forces. While most Cossacks initially sided with the Rada, many joined the Bolsheviks who promised them autonomy.

In March 1918, after Lavr Kornilov's successful offensive, the Kuban Rada placed itself under his authority. With his death in June 1918, however, a federative union was signed with the Ukrainian government of Hetman Pavlo Skoropadsky after which many Cossacks left to return home or defected to the Bolsheviks. Additionally, there was an internal struggle among the Kuban cossacks over loyalty towards

In March 1918, after Lavr Kornilov's successful offensive, the Kuban Rada placed itself under his authority. With his death in June 1918, however, a federative union was signed with the Ukrainian government of Hetman Pavlo Skoropadsky after which many Cossacks left to return home or defected to the Bolsheviks. Additionally, there was an internal struggle among the Kuban cossacks over loyalty towards Anton Denikin

Anton Ivanovich Denikin (, ; – 7 August 1947) was a Russian military leader who served as the Supreme Ruler of Russia, acting supreme ruler of the Russian State and the commander-in-chief of the White movement–aligned armed forces of Sout ...

's Russian Volunteer Army and the Ukrainian People's Republic

The Ukrainian People's Republic (UPR) was a short-lived state in Eastern Europe. Prior to its proclamation, the Central Council of Ukraine was elected in March 1917 Ukraine after the Russian Revolution, as a result of the February Revolution, ...

.

On 6 November 1919, Denikin's forces surrounded the Rada, and with the help of Ataman Alexander Filimonov arrested ten of its members, including the Ukrainophile, P. Kurgansky, who was the premier of the Rada, and publicly hanged one of them for treason. Many Cossacks joined Denikin and fought in the ranks of the Volunteer Army. In December 1919, after Denikin's defeat and as it became clear that the Bolsheviks would overrun the Kuban, some of the pro-Ukrainian groups attempted to restore the Rada and to break away from the Volunteer Army and fight the Bolsheviks in alliance with Ukraine; however, by early 1920 the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

took most of Kuban, and both the Rada and Denikin were ousted.

The Soviet policy of de-Cossackization repressed Cossacks and aimed to eliminate Cossack distinctness.Nicolas Werth, Karel Bartošek, Jean-Louis Panné, Jean-Louis Margolin, Andrzej Paczkowski, Stéphane Courtois

Stéphane Courtois (; born 25 November 1947) is a French historian and university professor, a director of research at the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS), professor at the Catholic Institute of Higher Studies (ICES) in La ...

. '' The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression''. Harvard University Press

Harvard University Press (HUP) is an academic publishing house established on January 13, 1913, as a division of Harvard University. It is a member of the Association of University Presses. Its director since 2017 is George Andreou.

The pres ...

, 1999. p. 98 The de-Cossackization is sometimes described as an act of genocide

Genocide is violence that targets individuals because of their membership of a group and aims at the destruction of a people. Raphael Lemkin, who first coined the term, defined genocide as "the destruction of a nation or of an ethnic group" by ...

.Orlando Figes

Orlando Guy Figes (; born 20 November 1959) is a British and German historian and writer. He was a professor of history at Birkbeck College, University of London, where he was made Emeritus Professor on his retirement in 2022.

Figes is known f ...

. ''A People's Tragedy: The Russian Revolution: 1891–1924.'' Penguin Books

Penguin Books Limited is a Germany, German-owned English publishing, publishing house. It was co-founded in 1935 by Allen Lane with his brothers Richard and John, as a line of the publishers the Bodley Head, only becoming a separate company the ...

, 1998. Donald Rayfield

Patrick Donald Rayfield OBE (born 12 February 1942, Oxford) is an English academic and Emeritus Professor of Russian and Georgian at Queen Mary University of London. He is an author of books about Russian and Georgian literature, and about Jos ...

. ''Stalin and His Hangmen

''Stalin and His Hangmen: An Authoritative Portrait of a Tyrant and Those Who Served Him'' by Donald Rayfield, and the imprinted with another subtitle: ''Stalin and His Hangmen: The Tyrant and Those Who Killed for Him'', is a 2004 political biog ...

: The Tyrant and Those Who Killed for Him'' Random House, 2004. Mikhail Heller & Aleksandr Nekrich. ''Utopia in Power: The History of the Soviet Union from 1917 to the Present.''Soviet order to exterminate Cossacks is unearthedUniversity of York

The University of York (abbreviated as or ''York'' for Post-nominal letters, post-nominals) is a public Collegiate university, collegiate research university in York, England. Established in 1963, the university has expanded to more than thir ...

Communications Office, 21 January 2003

World War II

Collaborators in Wehrmacht and Waffen SS

The first collaborators were formed from Soviet Cossack POWs and deserters after the consequences of the Red Army's early defeats in the course ofOperation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and several of its European Axis allies starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during World War II. More than 3.8 million Axis troops invaded the western Soviet Union along ...

. During the Battle of the Caucasus

The Battle of the Caucasus was a series of Axis and Soviet operations in the Caucasus as part of the Eastern Front of World War II. On 25 July 1942, German troops captured Rostov-on-Don, opening the Caucasus region of the southern Soviet ...

in summer of 1942, some of the Nazi aggressors reaching Kuban were greeted as liberators. Many Soviet Kuban Cossacks chose to defect to Nazi service either when in POW camps or on active duty in the Soviet Army. For example, Major Kononov deserted on 22 August 1941 with an entire regiment and was instrumental in organizing Cossack volunteers in the Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the German Army (1935–1945), ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmac ...

. Some Cossack emigres, such as Andrei Shkuro and Pyotr Krasnov chose to collaborate with the Nazis as well and stood at the helm of two Cossack divisions on Nazi service. However, most volunteers came after the Nazis reached the Cossack homelands in summer of 1942. The Cossack National Movement of Liberation was set up in hope of mobilizing opposition to the Soviet regime with an intent to rebuild an independent nationalist Cossack state.Lt. Gen Wladyslaw Anders and Antonio MunoRussian Volunteers in the German Wehrmacht in WWII

/ref> While there were several smaller Cossack detachments in the Wehrmacht since 1941, the 1st Cossack Division made up of Don, Terek and Kuban Cossacks was formed in 1943. This division was further augmented by the 2nd Cossack Cavalry Division formed in December 1944. Both divisions participated in hostilities against Tito's partisans in Yugoslavia. In February 1945, both Cossack Divisions were transferred into the

Waffen-SS

The (; ) was the military branch, combat branch of the Nazi Party's paramilitary ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS) organisation. Its formations included men from Nazi Germany, along with Waffen-SS foreign volunteers and conscripts, volunteers and conscr ...

and formed the XV SS Cossack Cavalry Corps. At the end of the war, the Cossack collaborators retreated to Italy and surrendered to the British army, but, under the Yalta agreement

The Yalta Conference (), held 4–11 February 1945, was the World War II meeting of the heads of government of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union to discuss the postwar reorganization of Germany and Europe. The three sta ...

, were forcibly repatriated with the rest of the collaborators to the Soviet authorities and some executed. (see Betrayal of the Cossacks) One of the Kuban leaders, the ''ataman'' Vyacheslav Naumenko served as their principle historian after World War Two, writing the first Russian language book about the Repatriation of Cossacks in his two volume work published in 1962 and 1970 entitled ''Velikoe Predatelstvo'' (''The Great Betrayal'').

Red Army Cossacks

Despite the defections that were taking place, the majority of the Cossacks remained loyal to the Red Army. In the earliest battles, particularly the encirclement of Belostok Cossack units such as the 94th Beloglisnky, 152nd Rostovsky and 48th Belorechensky regiments fought to their death. In the opening phase of the war, during the German advance towards Moscow, Cossacks became extensively used for the raids behind enemy lines. The most famous of these took place during the Battle of Smolensk under the command of Lev Dovator, whose 3rd Cavalry Corps consisted of the 50th and 53rd Cavalry divisions from the Kuban and Terek Cossacks, which were mobilised from the Northern Caucasus. The raid, which in ten days covered 300 km, destroyed the hinterlands of the 9th German Army before successfully breaking out. Whilst units under the command of General Pavel Belov, the 2nd Cavalry Corps made from Don, Kuban and Stavropol Cossacks spearheaded the counter-attack onto the right flank of the 6th German Army delaying its advance towards Moscow. The high professionalism that the Cossacks under Dovator and Belov (both generals would later be granted the titleHero of the Soviet Union

The title Hero of the Soviet Union () was the highest distinction in the Soviet Union, awarded together with the Order of Lenin personally or collectively for heroic feats in service to the Soviet state and society. The title was awarded both ...

and their units raised to a Guards (elite) status) ensured that many new units would be formed. In the end, if the Germans during the whole war only managed to form two Cossack Corps, the Red Army in 1942 already had 17. Many of the newly formed units were filled with ethnically Cossack volunteers. The Kuban Cossacks were allocated to the 10th, 12th and 13th Corps. However, the most famous Kuban Cossack unit would be the 17th Cossack Corps under the command of general .

During one particular attack, Cossacks killed up to 1,800 enemy soldiers and officers, they took 300 prisoners, seized 18 artillery pieces and 25 mortars. The 5th and 9th Romanian Cavalry divisions fled in panic, and the 198th German Infantry division, carrying large losses, hastily departed to the left bank of the river Ei.

During the opening phase of the Battle of Stalingrad

The Battle of Stalingrad ; see . rus, links=on, Сталинградская битва, r=Stalingradskaya bitva, p=stəlʲɪnˈɡratskəjə ˈbʲitvə. (17 July 19422 February 1943) was a major battle on the Eastern Front of World War II, ...

, when the Germans overran the Kuban, the majority of the Cossack population, long before the Germans began their agitation with Krasnov and Shkuro, became involved in Partisan

Partisan(s) or The Partisan(s) may refer to:

Military

* Partisan (military), paramilitary forces engaged behind the front line

** Francs-tireurs et partisans, communist-led French anti-fascist resistance against Nazi Germany during WWII

** Ital ...

activity. Raids onto the German positions from the Caucasus mountains became commonplace. After the German defeat at Stalingrad

Volgograd,. geographical renaming, formerly Tsaritsyn. (1589–1925) and Stalingrad. (1925–1961), is the largest city and the administrative centre of Volgograd Oblast, Russia. The city lies on the western bank of the Volga, covering an area o ...

, the 4th Guards Kuban Cossack Corps, strengthened by tanks and artillery, broke through the German lines and liberated Mineralnye Vody, and Stavropol

Stavropol (, ), known as Voroshilovsk from 1935 until 1943, is a city and the administrative centre of Stavropol Krai, in southern Russia. As of the 2021 Census, its population was 547,820, making it one of Russia's fastest growing cities.

E ...

.

For the latter part of the war, although the Cossacks did prove especially useful in reconnaissance and rear guards, the war did show that the age of horse cavalry had come to an end. The famous 4th Guards Kuban Cossacks Cavalry Corps which took part in heavy fighting in the course of the liberation of Southern Ukraine and Romania was allowed to proudly march on the Red Square

Red Square ( rus, Красная площадь, Krasnaya ploshchad', p=ˈkrasnəjə ˈploɕːɪtʲ) is one of the oldest and largest town square, squares in Moscow, Russia. It is located in Moscow's historic centre, along the eastern walls of ...

in the famous Moscow Victory Parade of 1945.

Modern Kuban Cossacks

Following the war, the Cossack regiments, along with remaining cavalry were disbanded and removed from the Soviet armed forces as they were thought to be obsolete. Starting in the late 1980s, there were renewed efforts to revive Cossack traditions which went to great lengths; in 1990, the Host was once again recognised by the SupremeAtaman

Ataman (variants: ''otaman'', ''wataman'', ''vataman''; ; ) was a title of Cossack and haidamak leaders of various kinds. In the Russian Empire, the term was the official title of the supreme military commanders of the Cossack armies. The Ukra ...

of the All-Great Don Host (Всевеликое Войско Донское). At this time some pro-Ukrainian sentiment emerged among some Kuban Cossack leaders. For example, when in May 1993 Cossack leader Yevhen Nahai was arrested and accused of plotting a coup, another Cossack leader (kish otaman Pyuypenko) threatened to call for support for Ukraine if Nahai's rights were violated. A march of cossack cavalry from eastern Ukraine to Kuban was met with some enthusiasm by locals.

The Cossacks have actively participated in some of the more abrupt political developments following the dissolution of the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union was formally dissolved as a sovereign state and subject of international law on 26 December 1991 by Declaration No. 142-N of the Soviet of the Republics of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union. Declaration No. 142-Н of ...

: invasions of South Ossetia

South Ossetia, officially the Republic of South Ossetia or the State of Alania, is a landlocked country in the South Caucasus with International recognition of Abkhazia and South Ossetia, partial diplomatic recognition. It has an offici ...

, Crimea

Crimea ( ) is a peninsula in Eastern Europe, on the northern coast of the Black Sea, almost entirely surrounded by the Black Sea and the smaller Sea of Azov. The Isthmus of Perekop connects the peninsula to Kherson Oblast in mainland Ukrain ...

, Transnistria

Transnistria, officially known as the Pridnestrovian Moldavian Republic and locally as Pridnestrovie, is a Landlocked country, landlocked Transnistria conflict#International recognition of Transnistria, breakaway state internationally recogn ...

and Abkhazia

Abkhazia, officially the Republic of Abkhazia, is a List of states with limited recognition, partially recognised state in the South Caucasus, on the eastern coast of the Black Sea, at the intersection of Eastern Europe and West Asia. It cover ...

and nominally as peacekeepers in Kosovo. The latter conflict was in particular special for the Kuban Cossacks, initially a number of Cossacks fled from the de-Cossackization repressions of the 1920s and assimilated with the Abkhaz people. Before the Georgian-Abkhaz Conflict there was a strong movement of creating an Abkhaz-Kuban Host among the descendants. When the civil war broke out, 1500 Kuban Cossack volunteers from Russia came to aid the Abkhaz side. One of the notable groups was the 1st sotnia

A sotnia ( Ukrainian and , ) was a military unit and administrative division in some Slavic countries.

Sotnia, deriving back to 1248, has been used in a variety of contexts in both Ukraine and Russia to this day. It is a helpful word to create ...

under the command of Ataman Nikolay Pusko which reportedly completely destroyed a Ukrainian volunteer group fighting on the Georgian side and then went on to be the first to enter Sukhumi in 1993. Since then, a detachment of Kuban Cossacks continue to inhabit Abkhazia, and their presence continues to influence the Georgian-Russian relations.

According to human rights reports from the 1990s, the Cossacks regularly harassed non-Russians, such as Armenians and Chechens, living in southern Russia.

Close to one thousand Kuban Cossacks joined Crimean "self-defence" units during the Annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation

In February and March 2014, Russia invaded the Crimea, Crimean Peninsula, part of Ukraine, and then annexed it. This took place in the relative power vacuum immediately following the Revolution of Dignity. It marked the beginning of the Russ ...

in 2014. A contingent of Kuban Cossacks (led by Head of the All-Russian Cossack Society, Cossack General Nikolai Doluda) took part in the 2015 Moscow Victory Day Parade

The 2015 Moscow Victory Day Parade was a parade that took place in Red Square in Moscow on 9 May 2015 to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the capitulation of Nazi Germany in 1945. The annual parade marks the Allies of World War II, Allied ...

for the first time.

Present day military units

With the help of the governor of Krasnodar Krai, Aleksandr Tkachyov, the host has become an integral part of the Kuban life, there are joint combat training operations with theRussian Army

The Russian Ground Forces (), also known as the Russian Army in English, are the Army, land forces of the Russian Armed Forces.

The primary responsibilities of the Russian Ground Forces are the protection of the state borders, combat on land, ...

, policing of the rural areas with the Police of Russia

The Police of Russia () is the national Law enforcement in Russia, law enforcement agency of Russia, operating under the Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs, Ministry of Internal Affairs from . It was established on by decree of Peter the Gre ...

, and preparation of local youth for the one-year military conscription term. Not only is their aid in military affairs important, during the floods in 2004 of the Taman Peninsula they provided men and equipment for relief missions. Today, the host numbers 25 thousand men and has its own distinct forces: a whole regiment of the 7th "Cherkassy" Guards Air-Assault Division (the 108th "Kuban Cossack" Guards Airborne Regiment) in the Russian VDV; 205th Motorised Rifle Brigade, within the Southern Military District

The Order of the Red Banner Southern Military District () is a military district of Russia.

It is one of the five military districts of the Russian Armed Forces, with its jurisdiction primarily within the North Caucasus region of the country ...

in the Russian Ground Forces

The Russian Ground Forces (), also known as the Russian Army in English, are the Army, land forces of the Russian Armed Forces.

The primary responsibilities of the Russian Ground Forces are the protection of the state borders, combat on land, ...

, in addition to border guards.

On 2 August 2012, the governor of Krasnodar Krai

Krasnodar Krai (, ) is a federal subjects of Russia, federal subject of Russia (a krai), located in the North Caucasus region in Southern Russia and is administratively a part of the Southern Federal District. Its administrative center is the t ...

, Alexander Tkachyov announced a controversial plan to deploy a paramilitary force of one thousand unarmed but uniformed Kuban Cossacks in the region to help police patrols. The cossacks were to be charged with preventing what he described as "illegal immigration" from the neighboring Caucasian republics.

The Kuban Cossacks has maintained a guard of honour

A guard of honour (Commonwealth English), honor guard (American English) or ceremonial guard, is a group of people, typically drawn from the military, appointed to perform ceremonial duties – for example, to receive or guard a head of state ...

since the mid 2000s. The formation of the guard of honor began in April 2006 by a group of Cossacks with the support of the Cossack chieftain, General Vladimir Gromov. On 12 June 2006, the guard performed for the first time at the Cossack monument in Krasnodar

Krasnodar, formerly Yekaterinodar (until 1920), is the largest city and the administrative centre of Krasnodar Krai, Russia. The city stands on the Kuban River in southern Russia, with a population of 1,154,885 residents, and up to 1.263 millio ...

. Cossack Colonel Pyotr Petrenko has been in charge of this unit for 12 years. They wear the historical uniform of the His Majesty's Own Cossack Escort Regiment. After an increase in personnel took place, an equestrian group was formed. The requirements for members of the guard of honor include a lack of a criminal record and being more than 180 centimeters in height.

Culture

Because of the unique migration pattern that the original

Because of the unique migration pattern that the original Zaporozhian Cossacks

The Zaporozhian Cossacks (in Latin ''Cossacorum Zaporoviensis''), also known as the Zaporozhian Cossack Army or the Zaporozhian Host (), were Cossacks who lived beyond (that is, downstream from) the Dnieper Rapids. Along with Registered Cossa ...

undertook, the Kuban Cossack identity has produced one of the most distinct cultures not only amongst other Cossacks but throughout the whole Eastern Slavic identity. The proximity to the Caucasus

The Caucasus () or Caucasia (), is a region spanning Eastern Europe and Western Asia. It is situated between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea, comprising parts of Southern Russia, Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. The Caucasus Mountains, i ...

mountains and the Circassian people influenced the dress and uniform of the Cossacks — the distinctive cherkeska overcoat and the bashlyk scarf, local dance such as the Lezginka too came into the Kuban Cossack lifestyle. At the same time, the Cossacks continued much of their Zaporozhian legacy, including a Kuban Bandura movement and the Kuban Cossack Choir which became one of the most famous in the world for their performance of Cossack and other folk songs and dances, performed in both the Russian and Ukrainian languages.

National identity

The concept of national and ethnic identity of the Kuban Cossacks has changed with time and has been the subject of much contention. In the 1897 census, 47.3% of the Kuban population (including extensive 19th century non-Cossack migrants from both Ukraine and Russia) referred to their native language as Little Russian (Ukrainian), while 42.6% referred to their native language as Great Russian (Russian). Most cultural productions in Kuban spanning 1890–1910, such as plays, stories, etc., were written and performed in the Ukrainian language, and one of the first political parties in Kuban was the Ukrainian Revolutionary Party. During World War I, Austrian officials received reports from a Ukrainian organization of the Russian Empire that 700 Kuban Cossacks in eastern Galicia had been arrested by their Russian officers for refusing to fight against Ukrainians in the Austrian army. Briefly during the Russian Civil War, the Kuban Cossack Rada declared Ukrainian to be the official language of the Kuban Cossacks, before its suppression by the RussianWhite

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no chroma). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully (or almost fully) reflect and scatter all the visible wa ...

leader General Denikin.

After the Bolshevik Victory in the Russian Civil War

The Russian Civil War () was a multi-party civil war in the former Russian Empire sparked by the 1917 overthrowing of the Russian Provisional Government in the October Revolution, as many factions vied to determine Russia's political future. I ...

, the Kuban was viewed as one of the most hostile regions to the young Communist state. In his 1923 speech devoted to the national and ethnic issues in the party and state affairs, Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

identified several obstacles in implementing the national programme of the party. Those were the "dominant-nation chauvinism", "economic and cultural inequality" of the nationalities and the "remnants of nationalism among a number of nations which have borne the heavy yoke of national oppression". For the Kuban, this was met with a unique approach. The victim/minority became the non-Cossack peasants who, like their counterparts in New Russia, were mixed population group, with an ethnic Ukrainian majority. To counter "dominant-nation chauvinism" a policy of Ukrainization

Ukrainization or Ukrainisation ( ) is a policy or practice of increasing the usage and facilitating the development of the Ukrainian language and promoting other elements of Ukrainian culture in various spheres of public life such as education, ...

/ Korenization was introduced. According to the 1926 census, there were already nearly a million Ukrainians registered in the Kuban Okrug alone (or 62% of the total population)

Additionally, more than 700 schools with Ukrainian as the language of instruction were opened, and the Kuban Pedagogical Institute had its own Ukrainian department. Numerous Ukrainian-language newspapers such as ''Chornomorets'' and ''Kubanska Zoria'' were published. According to historian A.L. Pawliczko, there was an attempt to have a referendum on the joining of Kuban to the Ukrainian SSR. In 1930, the Ukrainian Minister ("People’s Komissar") Mykola Skrypnyk

Mykola Oleksiiovych Skrypnyk (; – 7 July 1933), was a Ukrainian Bolshevik revolutionary and Communist leader who was a proponent of the Ukrainian Republic's independence, and later led the cultural Ukrainization effort in Soviet Ukraine. Whe ...

, involved in solving national issues in the Ukrainian SSR, put forward an official proposal to Joseph Stalin that the territories of Voronezh

Voronezh ( ; , ) is a city and the administrative centre of Voronezh Oblast in southwestern Russia straddling the Voronezh River, located from where it flows into the Don River. The city sits on the Southeastern Railway, which connects wes ...

, Kursk

Kursk (, ) is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, city and the administrative center of Kursk Oblast, Russia, located at the confluence of the Kur (Kursk Oblast), Kur, Tuskar, and Seym (river), Seym rivers. It has a population of

Kursk ...

, Chornomoriya, Azov

Azov (, ), previously known as Azak ( Turki/ Kypchak: ),

is a town in Rostov Oblast, Russia, situated on the Don River just from the Sea of Azov, which derives its name from the town. The population is

History

Early settlements in the vici ...

, Kuban regions be administered by the government of the Ukrainian SSR.

By the end of 1932, the Ukrainization programme was reversed, and by the late 1930s the majority of Kuban Ukrainians identified themselves as Russians As a result, in the 1939 census, Russians in the Kuban were a majority of 2754027 or 86% The 2nd edition of the Great Soviet Encyclopedia

The ''Great Soviet Encyclopedia'' (GSE; , ''BSE'') is one of the largest Russian-language encyclopedias, published in the Soviet Union from 1926 to 1990. After 2002, the encyclopedia's data was partially included into the later ''Great Russian Enc ...

explicitly named the Kuban Cossacks as Russians.

The modern Kuban vernacular known as balachka differs from contemporary literary Russian and is most similar to the dialect of Ukrainian spoken in central Ukraine near Cherkasy Some regions the vernacular includes many Northern Caucasus words and accents. The influence of Russian grammatical forms is also apparent.

Like many other Cossacks, some refuse to accept themselves as part of the standard ethnic Russian people, and claim to be a separate subgroup on par with sub-ethnicities such as the Pomors. In the 2002 Russian census the Cossacks were allowed to have distinct nationality as a separate Russian sub-ethnical group. The Kuban Cossacks living in Krasnodar Kray, Adygea

Adygea ( ), officially the Republic of Adygea or the Adygean Republic, is a republics of Russia, republic of Russia. It is situated in the North Caucasus of Eastern Europe. The republic is a part of the Southern Federal District, and covers an a ...

, Karachayevo-Cherkessia and some regions of Stavropol Krai and Kabardino-Balkaria

Kabardino-Balkaria (), officially the Kabardino-Balkarian Republic, is a republic of Russia located in the North Caucasus. As of the 2021 Census, its population was 904,200. Its capital is Nalchik. The area contains the highest mountain in ...

counted 25,000 men. However, the strict governance of the census meant that only Cossacks who are in active service were treated as such, and at the same time, 300,000 families are registered by the Kuban Cossack Host. Kuban Cossacks not politically affiliated with the Kuban Cossack Host, such as the director of the Kuban Cossack Choir Viktor Zakharchenko, have maintained at various times a pro-Ukrainian orientation.The politics of identity in a Russian borderland province: the Kuban neo-Cossack movement, 1989-1996, by Georgi M. Derluguian and Serge Cipko; Europe-Asia Studies; December 199URL

/ref>

Organisation

Early 20th century

Within the Empire, the Kuban land was administered through the Kuban Oblast with a semi-military administration. It was composed of seven subdivisions (), and numbered 1.3 million people (278 and 32 ). Kuban Cossacks formed regular units of the Imperial Russian Army as listed below. The following lists the structure prior to the outbreak of World War I, although this was re-organised during the conflict (see foot-note). In peacetime the Host provided 10 horse regiments making up a Kuban Cossack division, six ''plastun'' (infantry) battalions and six horse-artillery batteries; in addition to irregular and support units. The "first" regiments were linked to the specific locales that they were recruited from, although they would often be deployed elsewhere in the Empire. In wartime, recruits were drafted from each region to form "second" regiments during the stage of initial mobilization. If further manpower was required, a "third" regiment would be formed to be dispatched as reinforcements. During World War One a total of 37 horse (cavalry) regiments were raised by the Kuban Cossack Host. Regiments: * 1st and 2nd Kuban Life Guard sotnias of His Imperial Majesty's personal convoy (a special unit of theImperial Guard

An imperial guard or palace guard is a special group of troops (or a member thereof) of an empire, typically closely associated directly with the emperor and/or empress. Usually these troops embody a more elite status than other imperial force ...

acting for personal protection of the monarch)

* 1st Khopyor regiment "Her Imperial Highness Grand Duchess Anastasia Mikhailovna"

* 1st Kuban regiment "General Field Marshal Grand Duke Michael Nikolaevich"

* 1st Zaporozhian regiment "Empress Catherine the Great

Catherine II. (born Princess Sophie of Anhalt-Zerbst; 2 May 172917 November 1796), most commonly known as Catherine the Great, was the reigning empress of Russia from 1762 to 1796. She came to power after overthrowing her husband, Peter I ...

"

* 1st Yekaterinodar regiment "Kosh Ataman Chepiga"

* 1st Poltavskaya regiment "Yekatrinoslav Viceroy General Field Marshal Prince Potyomkin-Tavrichesky"

* 1st Umanskaya regiment "Brigadier Golovaty"

* 1st Taman regiment "General Bezkrovny"

* 1st Laba regiment "General Zass"

* 1st Line regiment "General Velyaminov"

* 1st Black Sea regiment "Colonel Bursak"

Divisions:

* Kuban Cossack Division (after the outbreak of World War I, the Russian Army began reforming this system along modern lines, but only one division was in existence in 1914)

Plastuns:

* 1st Kuban plastun battalion "General Field Marshal Grand Duke Michael Nikolaevich"

* 2nd through 6th Kuban plastun battalions

As noted the ''plastun'' units served as infantry. On mobilization an additional six battalions (numbered 7th through 12th) were added to the peacetime establishment, and a further two (13th and 14th) raised as reserve units. The effectiveness of these units was demonstrated during the war, particularly the Caucasus Front and by 1917 a total of 22 battalions, comprising one division plus four brigades, were on active service. A further three battalions were in reserve.

Horse artillery:

* 1st Kuban Cossack battery "General Field Marshal Grand Duke Michael Nikolaevich"

* 2nd through 5th Kuban Cossack batteries.

In addition there four commands that were responsible for support and home front organisation in the Kuban (supplies, hospitals etc.): Ust-Labinskaya, Armavirskaya, Labinskaya and Batalpashinskaya.

From 1914 to 1917 the Kuban Cossack Host committed a total of 89 thousand men to the Russian war effort. These included 37 horse regiments, a cavalry division, 2 mounted regiments recruited from mountain peoples (Adyghe and Karachay), six ''convoy'' (Imperial Guard) escort half-sotnias, two Leib Guard HIH personal sotnias, 4 infantry plastun brigades (22 battalions), a special plastun division, nine horse artillery batteries, four reserve horse regiments and three reserve plastun battalions.

See also

*Cossacks

The Cossacks are a predominantly East Slavic languages, East Slavic Eastern Christian people originating in the Pontic–Caspian steppe of eastern Ukraine and southern Russia. Cossacks played an important role in defending the southern borde ...

** Azov Cossack Host

** Black Sea Cossacks

** Caucasus Line Cossack Host

** Danubian Sich

**Don Cossacks

Don Cossacks (, ) or Donians (, ), are Cossacks who settled along the middle and lower Don River (Russia), Don. Historically, they lived within the former Don Cossack Host (, ), which was either an independent or an autonomous democratic rep ...

**Zaporozhian Cossacks

The Zaporozhian Cossacks (in Latin ''Cossacorum Zaporoviensis''), also known as the Zaporozhian Cossack Army or the Zaporozhian Host (), were Cossacks who lived beyond (that is, downstream from) the Dnieper Rapids. Along with Registered Cossa ...

*Decossackization

De-Cossackization () was the Bolshevik policy of systematic repression against the Cossacks in the former Russian Empire between 1919 and 1933, especially the Don and Kuban Cossacks in Russia, aimed at the elimination of the Cossacks as a dist ...

* Kuban Cossack Culture

** Balachka

** Kuban bandurists

** Kuban Cossack Choir

** '' Cossacks of the Kuban'' — ''a color musical film, cinema of 1940s Soviet Union''.

* Ukrainians in the Kuban

** Felix Sumarokov-Elston — ''Ataman of the Kuban Cossacks (1860s).''

* Ethnic Cleansing of Circassians

*Auxiliaries

Auxiliaries are combat support, support personnel that assist the military or police but are organised differently from regular army, regular forces. Auxiliary may be military volunteers undertaking support functions or performing certain duties ...

Notes and citations

External links

Official website

Official section about Cossackdom at the Krasnodar Kray administration's site

Unofficial website

{{Authority control Ethnic groups in Russia Cossack hosts Kuban oblast Peoples of the Caucasus Ukrainian diaspora in Russia