Koroni on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Koroni or Corone () is a town and a former

The town was founded in ancient times. The 2nd century Greek geographer Pausanias in his book ''Messeniaka'' reports the original location of Koroni at modern

The town was founded in ancient times. The 2nd century Greek geographer Pausanias in his book ''Messeniaka'' reports the original location of Koroni at modern

In 1582, the fortress was part of the Sanjak of Mezistre, and reportedly contained 300 Christian and 10 Jewish households, while the Muslim population was limited to the officials and a 300-strong garrison, which apparently remained constant over the entire Ottoman period. According to the 17th-century traveller

In 1582, the fortress was part of the Sanjak of Mezistre, and reportedly contained 300 Christian and 10 Jewish households, while the Muslim population was limited to the officials and a 300-strong garrison, which apparently remained constant over the entire Ottoman period. According to the 17th-century traveller

Official website

{{Stato da Mar Populated places in Messenia Pylos-Nestor Rocket launch sites in Greece Stato da Màr Castles in the Peloponnese Venetian fortifications in Greece Arvanite settlements

municipality

A municipality is usually a single administrative division having municipal corporation, corporate status and powers of self-government or jurisdiction as granted by national and regional laws to which it is subordinate.

The term ''municipality' ...

in Messenia

Messenia or Messinia ( ; ) is a regional unit (''perifereiaki enotita'') in the southwestern part of the Peloponnese region, in Greece. Until the implementation of the Kallikratis plan on 1 January 2011, Messenia was a prefecture (''nomos' ...

, Peloponnese

The Peloponnese ( ), Peloponnesus ( ; , ) or Morea (; ) is a peninsula and geographic region in Southern Greece, and the southernmost region of the Balkans. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmus of Corinth land bridg ...

, Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Pylos-Nestor

Pylos-Nestoras () is a municipality in the Messenia regional unit, Peloponnese (region), Peloponnese, Greece. The seat of the municipality is the town Pylos. The municipality has an area of 554.265 km2.

Municipality

The municipality Pylos-Nestora ...

, of which it is a municipal unit. Known as ''Corone'' by the Venetians and Ottomans

Ottoman may refer to:

* Osman I, historically known in English as "Ottoman I", founder of the Ottoman Empire

* Osman II, historically known in English as "Ottoman II"

* Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empir ...

, the town of Koroni (pop. 1,193 in 2021) sits on the southwest peninsula of the Peloponnese

The Peloponnese ( ), Peloponnesus ( ; , ) or Morea (; ) is a peninsula and geographic region in Southern Greece, and the southernmost region of the Balkans. It is connected to the central part of the country by the Isthmus of Corinth land bridg ...

on the Gulf of Messinia in southern Greece, by road southwest of Kalamata

Kalamata ( ) is the second most populous city of the Peloponnese peninsula in southern Greece after Patras, and the largest city of the Peloponnese (region), homonymous administrative region. As the capital and chief port of the Messenia regiona ...

. The town is nestled on a hill below a Venetian castle and reaches to the edge of the gulf. The town was the seat of the former municipality of Koróni, which has a land area of and a population of 3,600 (2021 census). The municipal unit consists of the communities Akritochori, Charakopio, Chrysokellaria, Falanthi, Kaplani, Kompoi, Koroni, Vasilitsi, Vounaria and Iamia. It also includes the uninhabited island of Venétiko.

History

Petalidi

Petalidi () is a village and a former municipality in Messenia, Peloponnese, Greece. Since the 2011 local government reform it is part of the municipality Messini, of which it is a municipal unit. The municipal unit has an area of 104.970 km ...

, a town a few kilometers north of Koroni. He also reports many temples of Greek gods and a copper statue of Zeus

Zeus (, ) is the chief deity of the List of Greek deities, Greek pantheon. He is a sky father, sky and thunder god in ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology, mythology, who rules as king of the gods on Mount Olympus.

Zeus is the child ...

. In the centuries that followed, the town of Koroni moved to its current location, where the ancient town of Asini once stood. In the 6th and 7th centuries AD, the Byzantines built a fortress there.

The town appears for the first time as a bishopric

In church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided provinces were administratively associate ...

in the ''Notitiae Episcopatuum The ''Notitiae Episcopatuum'' (singular: ''Notitia Episcopatuum'') were official documents that furnished for Eastern countries the list and hierarchical rank of the metropolitan and suffragan bishoprics of a church.

In the Roman Church (the mos ...

'' of the Byzantine Emperor

The foundation of Constantinople in 330 AD marks the conventional start of the Eastern Roman Empire, which Fall of Constantinople, fell to the Ottoman Empire in 1453 AD. Only the emperors who were recognized as legitimate rulers and exercised s ...

Leo VI the Wise

Leo VI, also known as Leo the Wise (; 19 September 866 – 11 May 912), was Byzantine Emperor from 886 to 912. The second ruler of the Macedonian dynasty (although his parentage is unclear), he was very well read, leading to his epithet. During ...

, in which it appears as a suffragan

A suffragan bishop is a type of bishop in some Christian denominations.

In the Catholic Church, a suffragan bishop leads a diocese within an ecclesiastical province other than the principal diocese, the metropolitan archdiocese; the diocese led ...

of the See of Patras. Surviving seals give the names of some of its Greek bishops. The Greek eparchy was suppressed in the 19th century as part of an ecclesiastical reorganization after Greece gained its independence.

Venetian period

Following the fall ofConstantinople

Constantinople (#Names of Constantinople, see other names) was a historical city located on the Bosporus that served as the capital of the Roman Empire, Roman, Byzantine Empire, Byzantine, Latin Empire, Latin, and Ottoman Empire, Ottoman empire ...

to the Fourth Crusade

The Fourth Crusade (1202–1204) was a Latin Christian armed expedition called by Pope Innocent III. The stated intent of the expedition was to recapture the Muslim-controlled city of Jerusalem, by first defeating the powerful Egyptian Ayyubid S ...

in 1204, the '' Partitio Romaniae'' assigned most of the Peloponnese to the Republic of Venice

The Republic of Venice, officially the Most Serene Republic of Venice and traditionally known as La Serenissima, was a sovereign state and Maritime republics, maritime republic with its capital in Venice. Founded, according to tradition, in 697 ...

, but the Venetians moved slowly to claim it, and the peninsula swiftly passed to the Frankish crusaders under William of Champlitte, who established the Principality of Achaea

The Principality of Achaea () or Principality of Morea was one of the vassal states of the Latin Empire, which replaced the Byzantine Empire after the capture of Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade. It became a vassal of the Kingdom of Thes ...

. The fortress of Koroni was initially given to Champlitte's chief lieutenant, Geoffrey of Villehardouin

Geoffrey of Villehardouin (c. 1150 – c. 1213) was a French knight and historian who participated in and chronicled the Fourth Crusade. He is considered one of the most important historians of the time period,Smalley, p. 131 best known for wr ...

. It was not until 1206 or 1207, that a Venetian fleet under Premarini and the son of Doge Enrico Dandolo took the Messenia

Messenia or Messinia ( ; ) is a regional unit (''perifereiaki enotita'') in the southwestern part of the Peloponnese region, in Greece. Until the implementation of the Kallikratis plan on 1 January 2011, Messenia was a prefecture (''nomos' ...

n peninsula and Koroni with its neighbouring Methoni from Champlitte's men. Venetian possession of the two fortresses were recognized by Geoffrey of Villehardouin, by now Prince of Achaea, in the Treaty of Sapienza in June 1209.

The Venetian period lasted for three centuries, during which time Koroni and Methoni, or Coron and Modon—the first Venetian possessions on the Greek mainland—became, in the words of a Venetian document, "the receptacle and special nest of all our galleys, ships, and vessels on their way to the Levant", and by virtue of their position controlling the Levantine trade were known as "the chief eyes of the Republic". The town flourished as a waystation of merchants and pilgrims to the Holy Land

The term "Holy Land" is used to collectively denote areas of the Southern Levant that hold great significance in the Abrahamic religions, primarily because of their association with people and events featured in the Bible. It is traditionall ...

. Koroni in particular was famous for its cochineal

The cochineal ( , ; ''Dactylopius coccus'') is a scale insect in the suborder Sternorrhyncha, from which the natural dye carmine is derived. A primarily sessility (motility), sessile parasitism, parasite native to tropical and subtropical Sout ...

, from which crimson dyes were made, and for the Venetian engineers' expertise in siege engines, which was much in demand by the princes of Frankish Greece

The Frankish Occupation (; anglicized as ), also known as the Latin Occupation () and, for the Venetian domains, Venetian Occupation (), was the period in Greek history after the Fourth Crusade (1204), when a number of primarily French ...

in their wars. Of the two, Koroni was the more important: when the two captains of the fortresses were increased to three towards the end of the 13th century, the two resided in Koroni, and in emergencies a '' bailo'' resided there as an extraordinary consul. During this period Koroni became the seat of bishops of the Latin Church

The Latin Church () is the largest autonomous () particular church within the Catholic Church, whose members constitute the vast majority of the 1.3 billion Catholics. The Latin Church is one of 24 Catholic particular churches and liturgical ...

. As the Catholics imitated the pre-existing Byzantine ecclesiastical structure, the Latin bishop of Koroni remained a suffragan of the Latin Archbishop of Patras

The Latin Archbishopric of Patras was the see of Patras in the period in which its incumbents belonged to the Latin Church. This period began in 1205 with the installation in the see of a Catholic archbishop following the Fourth Crusade.

The Lat ...

. One of its bishops, Angelo Correr, later became Pope Gregory XII

Pope Gregory XII (; ; – 18 October 1417), born Angelo Corraro, Corario," or Correr, was head of the Catholic Church from 30 November 1406 to 4 July 1415. Reigning during the Western Schism, he was opposed by the Avignon claimant Benedi ...

. No longer a residential Catholic bishopric, Corone is today listed by the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

as a titular see

A titular see in various churches is an episcopal see of a former diocese that no longer functions, sometimes called a "dead diocese". The ordinary or hierarch of such a see may be styled a "titular metropolitan" (highest rank), "titular archbi ...

.

In the mid-14th century, the two Venetian colonies suffered greatly from the Black Death

The Black Death was a bubonic plague pandemic that occurred in Europe from 1346 to 1353. It was one of the list of epidemics, most fatal pandemics in human history; as many as people perished, perhaps 50% of Europe's 14th century population. ...

, so that it was necessary to send a fresh

batch of colonists from home, and the franchise was extended to all the inhabitants, except the Jews. The two fortresses began to be governed by a series of minutely detailed ''Statutes and Capitulations'' issued by the metropolitan government, containing such clauses as a regulation that forbade the Venetian garrison to wear beards, so as to distinguish them from the local Greeks. Unlike other Latin rulers in Greece, the Venetians allowed the Greek Orthodox bishops to reside in their sees alongside their Catholic counterparts, but in the latter half of the 14th century, there are reports of mistreatment of the Greek population, which fled from Venetian territory to the Franks of Achaea.

In the early 15th century, as the Principality of Achaea gradually collapsed, the Venetians expanded their territory in Messenia: Navarino Navarino or Navarin may refer to:

Battle

* Battle of Navarino, 1827 naval battle off Navarino, Greece, now known as Pylos

Geography

* Navarino is the former name of Pylos, a Greek town on the Ionian Sea, where the 1827 battle took place

** Old Na ...

was taken over in 1417, and by 1439 had constructed or taken over six further castles between Navarino and Methoni and Koroni to secure her extended possession. The first seaborne Ottoman attack on Koroni took place in 1428, and after the Ottoman conquest of the Despotate of the Morea

The Despotate of the Morea () or Despotate of Mystras () was a province of the Byzantine Empire which existed between the mid-14th and mid-15th centuries. Its territory varied in size during its existence but eventually grew to include almost a ...

in 1460, the Venetian domains shared a border with Ottoman territory. Koroni fell to the Ottomans in 1500, during the Second Ottoman–Venetian War (1499–1503): Sultan Bayezid II

Bayezid II (; ; 3 December 1447 – 26 May 1512) was the sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1481 to 1512. During his reign, Bayezid consolidated the Ottoman Empire, thwarted a pro-Safavid dynasty, Safavid rebellion and finally abdicated his throne ...

stormed Methoni, after which Koroni and Navarino surrendered (15 or 17 August 1500).

Ottoman and modern period

Supported by the local population, the town was retaken by admiralAndrea Doria

Andrea Doria, Prince of Melfi (; ; 30 November 146625 November 1560) was an Italian statesman, ', and admiral, who played a key role in the Republic of Genoa during his lifetime.

From 1528 until his death, Doria exercised a predominant influe ...

in 1532, but in the spring of 1533 the Ottomans laid siege to it. Doria was able to relieve the town, prompting Sultan Suleyman the Magnificent to call upon the services of the corsair captain Hayreddin Barbarossa

Hayreddin Barbarossa (, original name: Khiḍr; ), also known as Hayreddin Pasha, Hızır Hayrettin Pasha, and simply Hızır Reis (c. 1466/1483 – 4 July 1546), was an Ottoman corsair and later admiral of the Ottoman Navy. Barbarossa's ...

. Barbarossa was aided by the outbreak of plague among the garrison and a particularly harsh winter, and in 1534 the Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many countries in the Americas

**Spanish cuisine

**Spanish history

**Spanish culture

...

garrison surrendered the fortress and sailed for Italy. Albanian inhabitants who participated in the revolt travelled with Doria and populated several settlements in the Kingdom of Naples

The Kingdom of Naples (; ; ), officially the Kingdom of Sicily, was a state that ruled the part of the Italian Peninsula south of the Papal States between 1282 and 1816. It was established by the War of the Sicilian Vespers (1282–1302). Until ...

, including San Chirico Nuovo, Ginestra and Maschito, where the Arbëreshë dialect is still spoken.

In the first half of the 16th century, Koroni was initially a ''kaza

A kaza (, "judgment" or "jurisdiction") was an administrative divisions of the Ottoman Empire, administrative division of the Ottoman Empire. It is also discussed in English under the names district, subdistrict, and juridical district. Kazas co ...

'' within the sub-province (''sanjak

A sanjak or sancak (, , "flag, banner") was an administrative division of the Ottoman Empire. The Ottomans also sometimes called the sanjak a liva (, ) from the name's calque in Arabic and Persian.

Banners were a common organization of nomad ...

'') of Methoni and the seat of a '' kadi''. The fortress itself and the surrounding territory were an imperial fief (''hass-i hümayun''). Its annual revenue was 162,081 ''akçe

The ''akçe'' or ''akça'' (anglicized as ''akche'', ''akcheh'' or ''aqcha''; ; , , in Europe known as '' asper'') was a silver coin mainly known for being the chief monetary unit of the Ottoman Empire. It was also used in other states includi ...

s'', which, according to Theodore Spandounes, were granted along with the revenue of Methoni to Mecca

Mecca, officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, is the capital of Mecca Province in the Hejaz region of western Saudi Arabia; it is the Holiest sites in Islam, holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red Sea, in a narrow valley above ...

.

In 1582, the fortress was part of the Sanjak of Mezistre, and reportedly contained 300 Christian and 10 Jewish households, while the Muslim population was limited to the officials and a 300-strong garrison, which apparently remained constant over the entire Ottoman period. According to the 17th-century traveller

In 1582, the fortress was part of the Sanjak of Mezistre, and reportedly contained 300 Christian and 10 Jewish households, while the Muslim population was limited to the officials and a 300-strong garrison, which apparently remained constant over the entire Ottoman period. According to the 17th-century traveller Evliya Çelebi

Dervish Mehmed Zillî (25 March 1611 – 1682), known as Evliya Çelebi (), was an Ottoman Empire, Ottoman explorer who travelled through his home country during its cultural zenith as well as neighboring lands. He travelled for over 40 years, rec ...

, Koroni was the seat of a separate ''sanjak'', within either the Morea Eyalet

The Eyalet of the Morea () was a first-level province ('' eyalet'') of the Ottoman Empire, centred on the Peloponnese peninsula in southern Greece.

History

From the Ottoman conquest to the 17th century

The Ottoman Empire overran the Peloponne ...

or the Eyalet of the Archipelago

The Eyalet of the Islands of the White Sea () was a first-level province (eyalet) of the Ottoman Empire. From its inception until the Tanzimat reforms of the mid-19th century, it was under the personal control of the Kapudan Pasha, the commander-i ...

. The 17th-century French traveller Jean-Baptiste Tavernier

Jean-Baptiste Tavernier (1605–1689) was a 17th-century French gem merchant and traveler. Tavernier, a private individual and merchant traveling at his own expense, covered, by his own account, 60,000 leagues in making six voyages to Persia ...

reports that its ''bey

Bey, also spelled as Baig, Bayg, Beigh, Beig, Bek, Baeg, Begh, or Beg, is a Turkic title for a chieftain, and a royal, aristocratic title traditionally applied to people with special lineages to the leaders or rulers of variously sized areas in ...

'' (governor) had to provide a galley

A galley is a type of ship optimised for propulsion by oars. Galleys were historically used for naval warfare, warfare, Maritime transport, trade, and piracy mostly in the seas surrounding Europe. It developed in the Mediterranean world during ...

for the Ottoman navy

The Ottoman Navy () or the Imperial Navy (), also known as the Ottoman Fleet, was the naval warfare arm of the Ottoman Empire. It was established after the Ottomans first reached the sea in 1323 by capturing Praenetos (later called Karamürsel ...

. Later it was part of the Sanjak of the Morea, and is once more attested as a separate ''sanjak'' by François Pouqueville

François Charles Hugues Laurent Pouqueville (; 4 November 1770 – 20 December 1838) was a French diplomat, writer, explorer, physician and historian, and member of the Institut de France.

He traveled extensively throughout Ottoman-occupied G ...

in the late 18th century.

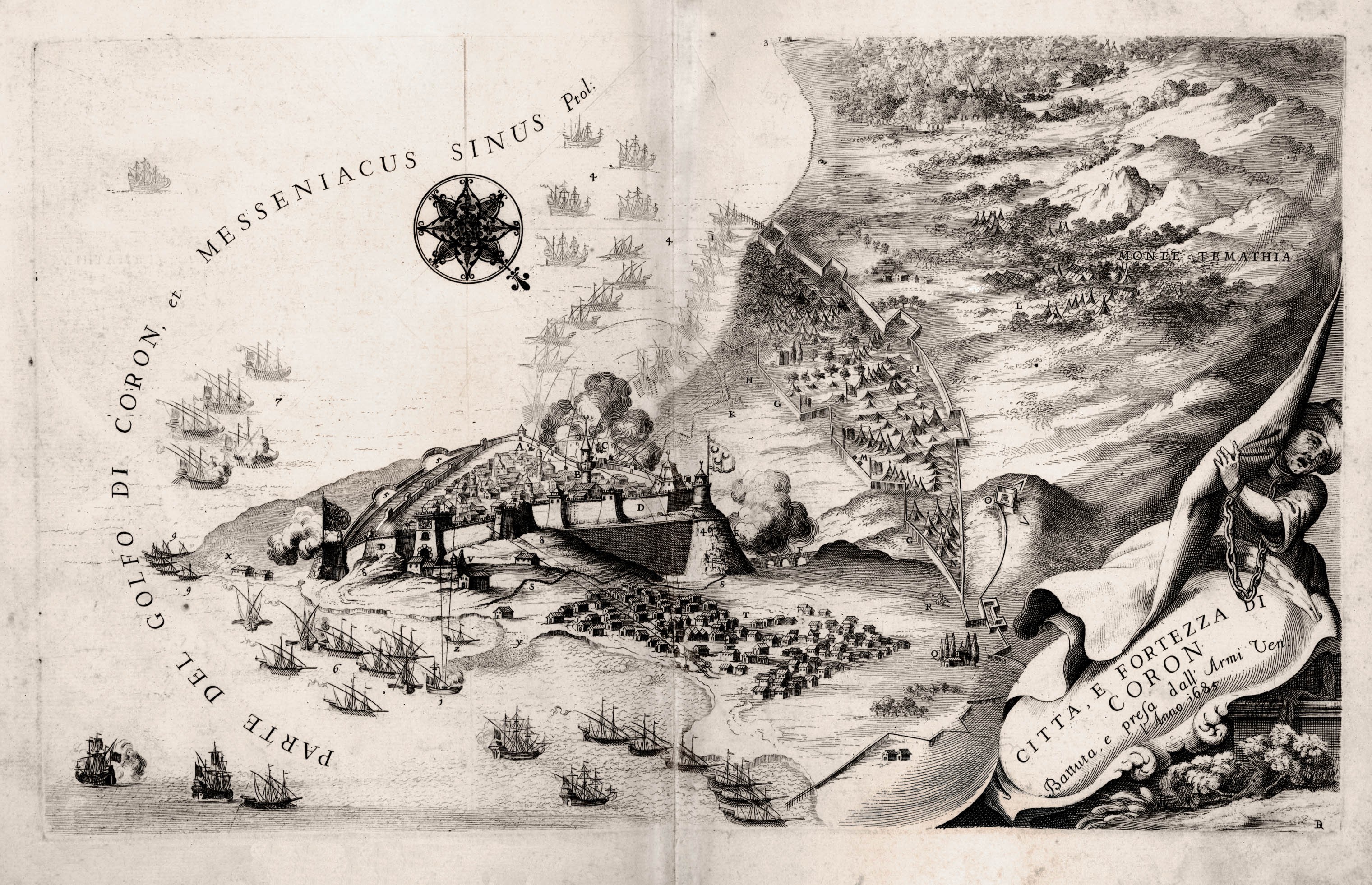

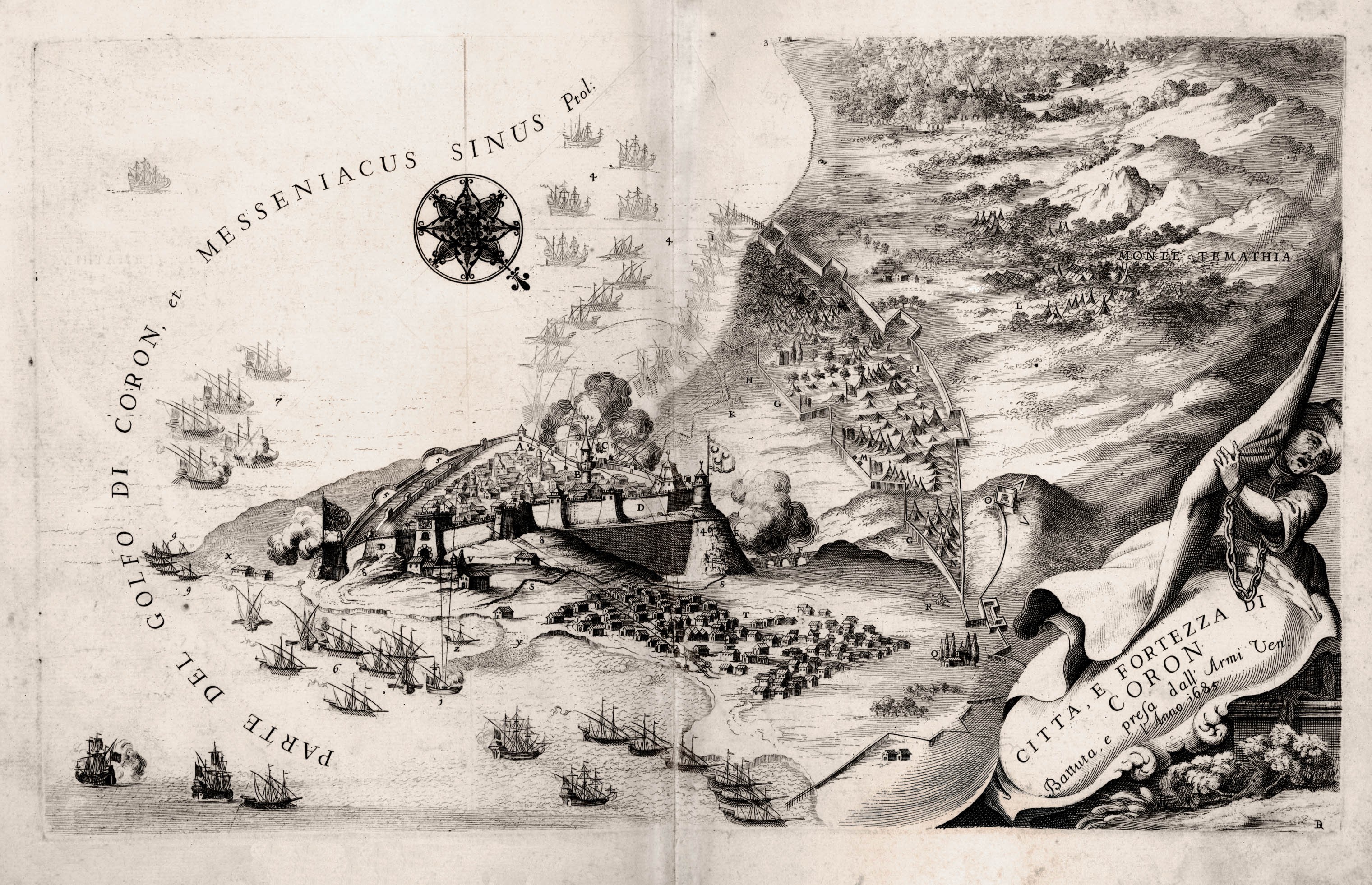

In the Morean War

The Morean war (), also known as the Sixth Ottoman–Venetian War, was fought between 1684–1699 as part of the wider conflict known as the "Great Turkish War", between the Republic of Venice and the Ottoman Empire. Military operations ranged ...

, Koroni was the first place the Venetians targeted during their conquest of the Peloponnese, capturing it after a siege (25 June – 7 August 1685). It remained in Venetian hands as part of the "Kingdom of the Morea

The Kingdom of the Morea or Realm of the Morea (; ; ) was the official name the Republic of Venice gave to the Peloponnese peninsula in Southern Greece (which was more widely known as the Morea until the 19th century) when it was conquered from ...

" until the entire peninsula was recaptured by the Ottomans in 1715, during the Seventh Ottoman–Venetian War

Seventh is the ordinal number (linguistics), ordinal form of the number 7, seven.

Seventh may refer to:

* Seventh Amendment to the United States Constitution

* A fraction (mathematics), , equal to one of seven equal parts

Film and television

*"T ...

. During the 18th century, the town declined: its harbour was reported as blocked and ruinous already at the turn of the previous century, but it continued to export silk and olive-oil; until the 1770s, four French merchant houses were active there. By 1805, the English traveller William Martin Leake

William Martin Leake FRS (14 January 17776 January 1860) was an English soldier, spy, topographer, diplomat, antiquarian, writer, and Fellow of the Royal Society. He served in the British Army, spending much of his career in the Mediterrane ...

reported that trade had stopped, that the port offered only "insecure anchorage", and that the Janissary

A janissary (, , ) was a member of the elite infantry units that formed the Ottoman sultan's household troops. They were the first modern standing army, and perhaps the first infantry force in the world to be equipped with firearms, adopted dur ...

garrison abused the local population.

Koroni became part of the modern Greek state

The history of modern Greece covers the history of Greece from the recognition by the Great Powers — United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, the United Kingdom, Kingdom of France, France and Russian Empire, Russia — of its Greek War of ...

in 1828, when it was liberated by the French General Nicolas Joseph Maison

Nicolas Joseph Maison, marquis de Maison (; 19 December 1771 – 13 February 1840) was a French military officer who served in the French Revolutionary Wars, the Napoleonic Wars, and as commander of the Morea expedition during the Greek War of In ...

.

Rocket launch site

Between 1966 and 1989 a facility for launchingsounding rocket

A sounding rocket or rocketsonde, sometimes called a research rocket or a suborbital rocket, is an instrument-carrying rocket designed to take measurements and perform scientific experiments during its sub-orbital flight. The rockets are often ...

s was established near the town. The first launches were performed from Koroni on May 20, 1966 for investigation an annular solar eclipse. These rockets reached an altitude of 114 kilometers. From 1972 to 1989 several Russian meteorological rockets of M-100 type were launched. They reached altitudes up to 95 kilometers. In total 371 rockets were launched.

Climate

Koroni has a hot-summermediterranean climate

A Mediterranean climate ( ), also called a dry summer climate, described by Köppen and Trewartha as ''Cs'', is a temperate climate type that occurs in the lower mid-latitudes (normally 30 to 44 north and south latitude). Such climates typic ...

(Köppen Köppen is a German surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Bernd Köppen (1951–2014), German pianist and composer

* Carl Köppen (1833-1907), German military advisor in Meiji era Japan

* Edlef Köppen (1893–1939), German author ...

''Csa'') with mild, rainy winters and hot, dry summers. The average annual temperature is 17.3 °C or 63.2 °F. About 737 mm or 29.0 inches of precipitation falls annually.

Notes

References

* * * * * * * *External links

Official website

{{Stato da Mar Populated places in Messenia Pylos-Nestor Rocket launch sites in Greece Stato da Màr Castles in the Peloponnese Venetian fortifications in Greece Arvanite settlements