Kimon on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Cimon or Kimon (; – 450BC) was an

University of Calgary

Lives of Eminent Commanders

/ref>

University of Massachusetts

The History of the Peloponnesian War.

/ref> As strategos, Cimon commanded most of the League's operations until 463 BC. During this period, he and Aristides drove the Spartans under Pausanias out of

This insulting rebuff caused the collapse of Cimon's popularity in Athens. As a result, he was ostracised from Athens for ten years beginning in 461 BC. The reformer Ephialtes then took the lead in running Athens and, with the support of Pericles, reduced the power of the Athenian Council of the

This insulting rebuff caused the collapse of Cimon's popularity in Athens. As a result, he was ostracised from Athens for ten years beginning in 461 BC. The reformer Ephialtes then took the lead in running Athens and, with the support of Pericles, reduced the power of the Athenian Council of the

Cimon of Athens

, in

The ''Life of Cimon'' in English

at the ''Internet Classics Archive'' {{Authority control 510s BC births 450 BC deaths 5th-century BC Athenians Athenians of the Greco-Persian Wars Ostracized Athenians Proxenoi Ancient Athenian generals Ancient Athenian admirals Philaidae 5th-century BC Greek politicians

Athenian

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

''strategos

''Strategos'' (), also known by its Linguistic Latinisation, Latinized form ''strategus'', is a Greek language, Greek term to mean 'military General officer, general'. In the Hellenistic world and in the Byzantine Empire, the term was also use ...

'' (general and admiral) and politician.

He was the son of Miltiades

Miltiades (; ; c. 550 – 489 BC), also known as Miltiades the Younger, was a Greek Athenian statesman known mostly for his role in the Battle of Marathon, as well as for his downfall afterwards. He was the son of Cimon Coalemos, a renowned ...

, also an Athenian ''strategos''. Cimon rose to prominence for his bravery fighting in the naval Battle of Salamis

The Battle of Salamis ( ) was a naval battle fought in 480 BC, between an alliance of Greek city-states under Themistocles, and the Achaemenid Empire under King Xerxes. It resulted in a victory for the outnumbered Greeks.

The battle was fou ...

(480 BC), during the Second Persian invasion of Greece

The second Persian invasion of Greece (480–479 BC) occurred during the Greco-Persian Wars, as King Xerxes I of Persia sought to conquer all of Greece. The invasion was a direct, if delayed, response to the defeat of the first Persian invasi ...

. Cimon was then elected as one of the ten ''strategoi'', to continue the Persian Wars

The Greco-Persian Wars (also often called the Persian Wars) were a series of conflicts between the Achaemenid Empire and Greek city-states that started in 499 BC and lasted until 449 BC. The collision between the fractious political world of th ...

against the Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire, also known as the Persian Empire or First Persian Empire (; , , ), was an Iranian peoples, Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid dynasty in 550 BC. Based in modern-day Iran, i ...

. He played a leading role in the formation of the Delian League

The Delian League was a confederacy of Polis, Greek city-states, numbering between 150 and 330, founded in 478 BC under the leadership (hegemony) of Classical Athens, Athens, whose purpose was to continue fighting the Achaemenid Empire, Persian ...

against Persia in 478 BC, becoming its commander in the early Wars of the Delian League, including at the Siege of Eion (476 BC).

In 466 BC, Cimon led a force to Asia Minor

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

, where he destroyed a Persian fleet and army at the Battle of the Eurymedon

The Battle of the Eurymedon was a double battle, taking place both on water and land, between the Delian League of Athens and her Allies, and the Persian Empire of Xerxes I. It took place in either 469 or 466 BCE, in the vicinity of the mouth ...

river. From 465 to 463 BC he suppressed the Thasian rebellion

The Thasian rebellion was an incident in 465 BC, in which Thasos rebelled against Athenian control, seeking to renounce its membership in the Delian League. The rebellion was prompted by a conflict between Athens and Thasos over control of silv ...

, in which the island of Thasos

Thasos or Thassos (, ''Thásos'') is a Greek island in the North Aegean Sea. It is the northernmost major Greek island, and 12th largest by area.

The island has an area of 380 km2 and a population of about 13,000. It forms a separate regiona ...

attempted to leave the Delian League. This event marked the transformation of the Delian League into the Athenian Empire

The Delian League was a confederacy of Polis, Greek city-states, numbering between 150 and 330, founded in 478 BC under the leadership (hegemony) of Classical Athens, Athens, whose purpose was to continue fighting the Achaemenid Empire, Persian ...

.

Cimon took an increasingly prominent role in Athenian politics, generally supporting the aristocrats and opposing the popular party (which sought to expand the Athenian democracy

Athenian democracy developed around the 6th century BC in the Ancient Greece, Greek city-state (known as a polis) of Classical Athens, Athens, comprising the city of Athens and the surrounding territory of Attica, and focusing on supporting lib ...

). A laconist, Cimon also acted as Sparta

Sparta was a prominent city-state in Laconia in ancient Greece. In antiquity, the city-state was known as Lacedaemon (), while the name Sparta referred to its main settlement in the Evrotas Valley, valley of Evrotas (river), Evrotas rive ...

's representative in Athens. In 462 BC, he convinced the Athenian Assembly

The ecclesia or ekklesia () was the assembly of the citizens in city-states of ancient Greece.

The ekklesia of Athens

The ekklesia of ancient Athens is particularly well-known. It was the popular assembly, open to all male citizens as soon a ...

to send military support to Sparta, where the helot

The helots (; , ''heílotes'') were a subjugated population that constituted a majority of the population of Laconia and Messenia – the territories ruled by Sparta. There has been controversy since antiquity as to their exact characteristics ...

s were in revolt (the Third Messenian War). Cimon personally commanded the force of 4,000 hoplite

Hoplites ( ) ( ) were citizen-soldiers of Ancient Greek city-states who were primarily armed with spears and shields. Hoplite soldiers used the phalanx formation to be effective in war with fewer soldiers. The formation discouraged the sold ...

s sent to Sparta. However, the Spartans refused their aid, telling the Athenians to go home – a major diplomatic snub. The resulting embarrassment destroyed Cimon's popularity in Athens; he was ostracized

Ostracism (, ''ostrakismos'') was an Athenian democratic procedure in which any citizen could be expelled from the city-state of Athens for ten years. While some instances clearly expressed popular anger at the citizen, ostracism was often us ...

in 461 BC, exiling him for a period of ten years.

The First Peloponnesian War

The First Peloponnesian War (460–445 BC) was fought between Sparta as the leaders of the Peloponnesian League and Sparta's other allies, most notably Thebes, and the Delian League led by Athens with support from Argos. This war consisted o ...

between Athens and Sparta began the following year. At the end of his exile, Cimon returned to Athens in 451 BC and immediately negotiated a truce

A ceasefire (also known as a truce), also spelled cease-fire (the antonym of 'open fire'), is a stoppage of a war in which each side agrees with the other to suspend aggressive actions often due to mediation by a third party. Ceasefires may b ...

with Sparta; however it did not lead to a permanent peace. He then proposed an expedition to Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

, which was in revolt against the Persians. Cimon was placed in command of the fleet of 200 warships. He laid siege to the town of Kition

Kition (Ancient Greek: , ; Latin: ; Egyptian: ; Phoenician: , , or , ;) was an ancient Phoenician and Greek city-kingdom on the southern coast of Cyprus (in present-day Larnaca), one of the Ten city-kingdoms of Cyprus.

Name

The name of the ...

, but died (of unrecorded causes) around the time of the failure of the siege in 450 BC.

Life

Early years

Cimon was born into Athenian nobility in 510 BC. He was a member of thePhilaidae

The Philaidae or Philaids () were a powerful noble family of ancient Athens. They were conservative land owning aristocrats and many of them were very wealthy. The Philaidae produced two of the most famous generals in Athenian history: Miltiades t ...

clan, from the deme

In Ancient Greece, a deme or (, plural: ''demoi'', δήμοι) was a suburb or a subdivision of Classical Athens, Athens and other city-states. Demes as simple subdivisions of land in the countryside existed in the 6th century BC and earlier, bu ...

of Laciadae (Lakiadai). His grandfather was Cimon Coalemos, who won three Olympic victories with his four-horse chariot and was assassinated by the sons of Peisistratus

Pisistratus (also spelled Peisistratus or Peisistratos; ; – 527 BC) was a politician in ancient Athens, ruling as tyrant in the late 560s, the early 550s and from 546 BC until his death. His unification of Attica, the triangular ...

. His father was the celebrated Athenian general Miltiades

Miltiades (; ; c. 550 – 489 BC), also known as Miltiades the Younger, was a Greek Athenian statesman known mostly for his role in the Battle of Marathon, as well as for his downfall afterwards. He was the son of Cimon Coalemos, a renowned ...

and his mother was Hegesipyle, daughter of the Thracian

The Thracians (; ; ) were an Indo-European speaking people who inhabited large parts of Southeast Europe in ancient history.. "The Thracians were an Indo-European people who occupied the area that today is shared between north-eastern Greece, ...

king Olorus and a relative of the historian Thucydides

Thucydides ( ; ; BC) was an Classical Athens, Athenian historian and general. His ''History of the Peloponnesian War'' recounts Peloponnesian War, the fifth-century BC war between Sparta and Athens until the year 411 BC. Thucydides has been d ...

.

While Cimon was a young man, his father was fined 50 talents after an accusation of treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state (polity), state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to Coup d'état, overthrow its government, spy ...

by the Athenian state. As Miltiades could not afford to pay this amount, he was put in jail, where he died in 489 BC. Cimon inherited this debt and, according to Diodorus, some of his father's unserved prison sentence in order to obtain his body for burial. As the head of his household, he also had to look after his sister or half-sister Elpinice. According to Plutarch

Plutarch (; , ''Ploútarchos'', ; – 120s) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo (Delphi), Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''Parallel Lives'', ...

, the wealthy Callias

Callias () was an Ancient Greek statesman, soldier and diplomat active in 5th century BC. He is commonly known as Callias II to distinguish him from his grandfather, Callias I, and from his grandson, Callias III, who apparently squandered the fam ...

took advantage of this situation by proposing to pay Cimon's debts for Elpinice's hand in marriage. Cimon agreed.Plutarch

Plutarch (; , ''Ploútarchos'', ; – 120s) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo (Delphi), Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''Parallel Lives'', ...

, Lives. Life of CimonUniversity of Calgary

Wikisource

Wikisource is an online wiki-based digital library of free-content source text, textual sources operated by the Wikimedia Foundation. Wikisource is the name of the project as a whole; it is also the name for each instance of that project, one f ...

)Cornelius Nepos

Cornelius Nepos (; c. 110 BC – c. 25 BC) was a Roman Empire, Roman biographer. He was born at Hostilia, a village in Cisalpine Gaul not far from Verona.

Biography

Nepos's Cisalpine birth is attested by Ausonius, and Pliny the Elder calls ...

Lives of Eminent Commanders

/ref>

Plutarch

Plutarch (; , ''Ploútarchos'', ; – 120s) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo (Delphi), Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''Parallel Lives'', ...

, Lives. Life of Themistocles.University of Massachusetts

Wikisource

Wikisource is an online wiki-based digital library of free-content source text, textual sources operated by the Wikimedia Foundation. Wikisource is the name of the project as a whole; it is also the name for each instance of that project, one f ...

)

Cimon in his youth had a reputation of being dissolute, a hard drinker, and blunt and unrefined; it was remarked that in this latter characteristic he was more like a Spartan than an Athenian.Plutarch, ''Cimon'' 481.

Marriage

Cimon is repeatedly said to have married or been otherwise involved with his sister or half-sister Elpinice (who herself had a reputation for sexualpromiscuity

Promiscuity is the practice of engaging in sexual activity frequently with different partners or being indiscriminate in the choice of sexual partners. The term can carry a moral judgment. A common example of behavior viewed as promiscuous by man ...

) prior to her marriage with Callias

Callias () was an Ancient Greek statesman, soldier and diplomat active in 5th century BC. He is commonly known as Callias II to distinguish him from his grandfather, Callias I, and from his grandson, Callias III, who apparently squandered the fam ...

, although this may be a legacy of simple political slander. He later married Isodice, Megacles

Megacles or Megakles () was the name of several notable men of ancient Athens, as well as an officer of Pyrrhus of Epirus.

First archon

The first Megacles was possibly a legendary archon of Athens from 922 BC to 892 BC.

Archon eponymous

The s ...

' granddaughter and a member of the Alcmaeonidae

The Alcmaeonidae (; , ; Attic: , ) or Alcmaeonids () were a wealthy and powerful noble family of ancient Athens, a branch of the Neleides who claimed descent from the mythological

Myth is a genre of folklore consisting primarily of narrati ...

family. Their first children were twin boys named Lacedaemonius (who would become an Athenian commander) and Eleus. Their third son was Thessalus (who would become a politician).

Military career

During theBattle of Salamis

The Battle of Salamis ( ) was a naval battle fought in 480 BC, between an alliance of Greek city-states under Themistocles, and the Achaemenid Empire under King Xerxes. It resulted in a victory for the outnumbered Greeks.

The battle was fou ...

, Cimon distinguished himself by his bravery. He is mentioned as being a member of an embassy sent to Sparta in 479 BC.

Between 478 BC and 476 BC, a number of Greek maritime cities around the Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It is located between the Balkans and Anatolia, and covers an area of some . In the north, the Aegean is connected to the Marmara Sea, which in turn con ...

did not wish to submit to Persian control again and offered their allegiance to Athens through Aristides

Aristides ( ; , ; 530–468 BC) was an ancient Athenian statesman. Nicknamed "the Just" (δίκαιος, ''díkaios''), he flourished at the beginning of Athens' Classical period and is remembered for his generalship in the Persian War. ...

at Delos

Delos (; ; ''Dêlos'', ''Dâlos''), is a small Greek island near Mykonos, close to the centre of the Cyclades archipelago. Though only in area, it is one of the most important mythological, historical, and archaeological sites in Greece. ...

. There, they formed the Delian League

The Delian League was a confederacy of Polis, Greek city-states, numbering between 150 and 330, founded in 478 BC under the leadership (hegemony) of Classical Athens, Athens, whose purpose was to continue fighting the Achaemenid Empire, Persian ...

(also known as the Confederacy of Delos), and it was agreed that Cimon would be their principal commander.Thucydides

Thucydides ( ; ; BC) was an Classical Athens, Athenian historian and general. His ''History of the Peloponnesian War'' recounts Peloponnesian War, the fifth-century BC war between Sparta and Athens until the year 411 BC. Thucydides has been d ...

The History of the Peloponnesian War.

/ref> As strategos, Cimon commanded most of the League's operations until 463 BC. During this period, he and Aristides drove the Spartans under Pausanias out of

Byzantium

Byzantium () or Byzantion () was an ancient Greek city in classical antiquity that became known as Constantinople in late antiquity and Istanbul today. The Greek name ''Byzantion'' and its Latinization ''Byzantium'' continued to be used as a n ...

.

Cimon also captured Eion on the Strymon from the Persian general Boges. Other coastal cities of the area surrendered to him after Eion, with the notable exception of Doriscus

Doriscus (, ''Dorískos'') was a settlement in ancient Thrace (modern-day Greece), on the northern shores of Aegean Sea, in a plain west of the river Hebrus (river), Hebrus. It was notable for remaining in Achaemenid Empire, Persian hands for many ...

. He also conquered Scyros and drove out the pirates who were based there. On his return, he brought the "bones" of the mythological Theseus

Theseus (, ; ) was a divine hero in Greek mythology, famous for slaying the Minotaur. The myths surrounding Theseus, his journeys, exploits, and friends, have provided material for storytelling throughout the ages.

Theseus is sometimes desc ...

back to Athens. To celebrate this achievement, three Herma

A herma (, plural ), commonly herm in English, is a sculpture with a head and perhaps a torso above a plain, usually squared lower section, on which male genitals may also be carved at the appropriate height. Hermae were so called either becaus ...

statues were erected around Athens.

Battle of the Eurymedon

Around 466 BC, Cimon carried the war against Persia intoAsia Minor

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

and decisively defeated the Persians at the Battle of the Eurymedon

The Battle of the Eurymedon was a double battle, taking place both on water and land, between the Delian League of Athens and her Allies, and the Persian Empire of Xerxes I. It took place in either 469 or 466 BCE, in the vicinity of the mouth ...

on the Eurymedon River Eurymedon may refer to:

Historical figures

*Eurymedon (strategos) (died 413 BC), one of the Athenian generals (strategoi) during the Peloponnesian War

*Eurymedon of Myrrhinus, married Plato's sister, Potone; he was the father of Speusippus

*Eurym ...

in Pamphylia

Pamphylia (; , ''Pamphylía'' ) was a region in the south of Anatolia, Asia Minor, between Lycia and Cilicia, extending from the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean to Mount Taurus (all in modern-day Antalya province, Turkey). It was bounded on the ...

. Cimon's land and sea forces captured the Persian camp and destroyed or captured the entire Persian fleet of 200 trireme

A trireme ( ; ; cf. ) was an ancient navies and vessels, ancient vessel and a type of galley that was used by the ancient maritime civilizations of the Mediterranean Sea, especially the Phoenicians, ancient Greece, ancient Greeks and ancient R ...

s manned by Phoenicia

Phoenicians were an Ancient Semitic-speaking peoples, ancient Semitic group of people who lived in the Phoenician city-states along a coastal strip in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily modern Lebanon and the Syria, Syrian ...

ns. And he established an Athenian colony nearby called Amphipolis

Amphipolis (; ) was an important ancient Greek polis (city), and later a Roman city, whose large remains can still be seen. It gave its name to the modern municipality of Amphipoli, in the Serres regional unit of northern Greece.

Amphipol ...

with 10,000 settlers. Many new allies of Athens were then recruited into the Delian League, such as the trading city of Phaselis

Phaselis () or Faselis () was a Greek and Roman city on the coast of ancient Lycia. Its ruins are located north of the modern town Tekirova in the Kemer district of Antalya Province in Turkey. It lies between the Bey Mountains and the forests ...

on the Lycia

Lycia (; Lycian: 𐊗𐊕𐊐𐊎𐊆𐊖 ''Trm̃mis''; , ; ) was a historical region in Anatolia from 15–14th centuries BC (as Lukka) to 546 BC. It bordered the Mediterranean Sea in what is today the provinces of Antalya and Muğ ...

n-Pamphylian border.

There is a view amongst some historians that while in Asia Minor, Cimon negotiated a peace between the League and the Persians after his victory at the Battle of the Eurymedon. This may help to explain why the Peace of Callias negotiated by his brother-in-law in 450 BC is sometimes called the Peace of Cimon as Callias' efforts may have led to a renewal of Cimon's earlier treaty. He had served Athens well during the Persian Wars

The Greco-Persian Wars (also often called the Persian Wars) were a series of conflicts between the Achaemenid Empire and Greek city-states that started in 499 BC and lasted until 449 BC. The collision between the fractious political world of th ...

and according to Plutarch

Plutarch (; , ''Ploútarchos'', ; – 120s) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo (Delphi), Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''Parallel Lives'', ...

: "In all the qualities that war demands he was fully the equal of Themistocles

Themistocles (; ; ) was an Athenian politician and general. He was one of a new breed of non-aristocratic politicians who rose to prominence in the early years of the Athenian democracy. As a politician, Themistocles was a populist, having th ...

and his own father Miltiades".

Thracian Chersonesus

After his successes in Asia Minor, Cimon moved to the Thracian colonyChersonesus

Chersonesus, contracted in medieval Greek to Cherson (), was an Greeks in pre-Roman Crimea, ancient Greek Greek colonization, colony founded approximately 2,500 years ago in the southwestern part of the Crimean Peninsula. Settlers from He ...

. There he subdued the local tribes and ended the revolt of the Thasians between 465 BC and 463 BC. Thasos

Thasos or Thassos (, ''Thásos'') is a Greek island in the North Aegean Sea. It is the northernmost major Greek island, and 12th largest by area.

The island has an area of 380 km2 and a population of about 13,000. It forms a separate regiona ...

had revolted from the Delian League over a trade rivalry with the Thracian hinterland and, in particular, over the ownership of a gold mine

Gold mining is the extraction of gold by mining.

Historically, mining gold from alluvial deposits used manual separation processes, such as gold panning. The expansion of gold mining to ores that are not on the surface has led to more comple ...

. Athens under Cimon laid siege

A siege () . is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition, or by well-prepared assault. Siege warfare (also called siegecrafts or poliorcetics) is a form of constant, low-intensity conflict charact ...

to Thasos after the Athenian fleet defeated the Thasos fleet. These actions earned him the enmity of Stesimbrotus of Thasos (a source used by Plutarch

Plutarch (; , ''Ploútarchos'', ; – 120s) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo (Delphi), Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''Parallel Lives'', ...

in his writings about this period in Greek history).

Trial for bribery

Despite these successes, Cimon was prosecuted by Pericles for allegedly acceptingbribes

Bribery is the corrupt solicitation, payment, or acceptance of a private favor (a bribe) in exchange for official action. The purpose of a bribe is to influence the actions of the recipient, a person in charge of an official duty, to act contrar ...

from Alexander I of Macedon

Alexander I (; died 454 BC), also known as Alexander the Philhellene (; ), was king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedonia from 498/497 BC until his death in 454 BC. He was succeeded by his eldest son, Perdiccas II.

Biography

Alexander wa ...

. According to Plutarch's account, Pericles at trial "was very gentle with Cimon, and took the floor only once in accusation." Cimon, in his defense, pointed out that he was never envoy to the rich kingdoms of Ionia or Thessaly, but rather to Sparta, whose frugality he lovingly imitated; and that, rather than enrich himself, he enriched Athens with the booty he acquired from the enemy. Cimon was in the end acquitted.

Helot revolt in Sparta

Cimon was Sparta's Proxenos atAthens

Athens ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. A significant coastal urban area in the Mediterranean, Athens is also the capital of the Attica (region), Attica region and is the southe ...

, he strongly advocated a policy of cooperation between the two states. He was known to be so fond of Sparta that he named one of his sons Lacedaemonius. In 462 BC, Cimon sought the support of Athens' citizens to provide help to Sparta. Although Ephialtes maintained that Sparta was Athens' rival for power and should be left to fend for itself, Cimon's view prevailed. Cimon then led 4,000 hoplite

Hoplites ( ) ( ) were citizen-soldiers of Ancient Greek city-states who were primarily armed with spears and shields. Hoplite soldiers used the phalanx formation to be effective in war with fewer soldiers. The formation discouraged the sold ...

s to Mt. Ithome to help the Spartan aristocracy deal with a major revolt by its helots. However, this expedition ended in humiliation for Cimon and for Athens when, fearing that the Athenians would end up siding with the helots, Sparta sent the force back to Attica.

Exile

This insulting rebuff caused the collapse of Cimon's popularity in Athens. As a result, he was ostracised from Athens for ten years beginning in 461 BC. The reformer Ephialtes then took the lead in running Athens and, with the support of Pericles, reduced the power of the Athenian Council of the

This insulting rebuff caused the collapse of Cimon's popularity in Athens. As a result, he was ostracised from Athens for ten years beginning in 461 BC. The reformer Ephialtes then took the lead in running Athens and, with the support of Pericles, reduced the power of the Athenian Council of the Areopagus

The Areopagus () is a prominent rock outcropping located northwest of the Acropolis in Athens, Greece. Its English name is the Late Latin composite form of the Greek name Areios Pagos, translated "Hill of Ares" (). The name ''Areopagus'' also r ...

(filled with ex-archon

''Archon'' (, plural: , ''árchontes'') is a Greek word that means "ruler", frequently used as the title of a specific public office. It is the masculine present participle of the verb stem , meaning "to be first, to rule", derived from the same ...

s and so a stronghold of oligarchy

Oligarchy (; ) is a form of government in which power rests with a small number of people. Members of this group, called oligarchs, generally hold usually hard, but sometimes soft power through nobility, fame, wealth, or education; or t ...

).

Power was transferred to the citizens, i.e. the Council of Five Hundred

The Council of Five Hundred () was the lower house of the legislature of the French First Republic under the Constitution of the Year III. It operated from 31 October 1795 to 9 November 1799 during the French Directory, Directory () period of t ...

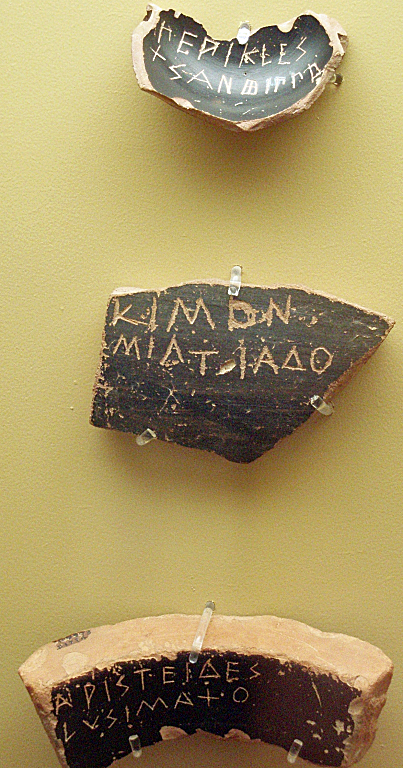

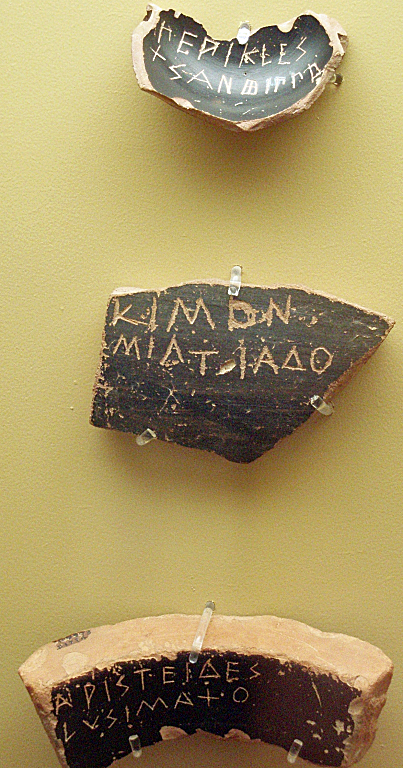

, the Assembly, and the popular law courts. Some of Cimon's policies were reversed including his pro-Spartan policy and his attempts at peace with Persia. Many ostraka

An ostracon (Greek: ''ostrakon'', plural ''ostraka'') is a piece of pottery, usually broken off from a vase or other earthenware vessel. In an archaeological or epigraphical context, ''ostraca'' refer to sherds or even small pieces of ston ...

bearing his name survive; one bearing the spiteful inscription: "''Cimon, son of Miltiades, and Elpinice too''" (his haughty sister).

In 458 BC, Cimon sought to return to Athens to assist its fight against Sparta at Tanagra, but was rebuffed.

Return

Eventually, around 451 BC, Cimon returned to Athens. Although he was not allowed to return to the level of power he once enjoyed, he was able to negotiate on Athens' behalf a five-year truce with the Spartans. Later, with a Persian fleet moving against a rebelliousCyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

, Cimon proposed an expedition to fight the Persians. He gained Pericles' support and sailed to Cyprus with two hundred triremes of the Delian League. From there, he sent sixty ships under Admiral Charitimides

Charitimides () (died 455 BCE) was an Ancient Athens, Athenian admiral of the 5th century BCE. At the time of the Wars of the Delian League, a continuing conflict between the Athenian-led Delian League of Greek city-states and the Achaemenid Emp ...

to Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

to help the Egyptian revolt of Inaros, in the Nile Delta

The Nile Delta (, or simply , ) is the River delta, delta formed in Lower Egypt where the Nile River spreads out and drains into the Mediterranean Sea. It is one of the world's larger deltas—from Alexandria in the west to Port Said in the eas ...

. Cimon used the remaining ships to aid the uprising of the Cypriot Greek city-states.

Rebuilding Athens

From his many military exploits and money gained through the Delian League, Cimon funded many construction projects throughout Athens. These projects were greatly needed in order to rebuild after theAchaemenid destruction of Athens

The destruction of Athens, took place between 480 and 479 BC, when Athens was captured and subsequently destroyed by the Achaemenid Empire. A prominent Greek city-state, it was attacked by the Persians in a two-phase offensive, amidst which the ...

. He ordered the expansion of the Acropolis

An acropolis was the settlement of an upper part of an ancient Greek city, especially a citadel, and frequently a hill with precipitous sides, mainly chosen for purposes of defense. The term is typically used to refer to the Acropolis of Athens ...

and the walls around Athens, and the construction of public roads, public gardens, and many political buildings.

Death on Cyprus

Cimon laid siege to thePhoenicia

Phoenicians were an Ancient Semitic-speaking peoples, ancient Semitic group of people who lived in the Phoenician city-states along a coastal strip in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily modern Lebanon and the Syria, Syrian ...

n and Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

stronghold of Citium on the southwest coast of Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

in 450BC; he died during or soon after the failed attempt. However, his death was kept secret from the Athenian army, who subsequently won an important victory over the Persians under his 'command' at the Battle of Salamis-in-Cyprus.Plutarch, Cimon, 19 He was later buried in Athens, where a monument was erected in his memory.

Historical significance

During his period of considerable popularity and influence at Athens, Cimon's domestic policy was consistently antidemocratic, and this policy ultimately failed. His success and lasting influence came from his military accomplishments and his foreign policy, the latter being based on two principles: continued resistance to Persian aggression, and recognition that Athens should be the dominant sea power in Greece, and Sparta the dominant land power. The first principle helped to ensure that direct Persian military aggression against Greece had essentially ended; the latter probably significantly delayed the outbreak of thePeloponnesian War

The Second Peloponnesian War (431–404 BC), often called simply the Peloponnesian War (), was an Ancient Greece, ancient Greek war fought between Classical Athens, Athens and Sparta and their respective allies for the hegemony of the Ancien ...

.

See also

* Amphictyonic League *Long Walls

Although long walls were built at several locations in ancient Greece, notably Corinth and Megara, the term ''Long Walls'' ( ) generally refers to the walls that connected classical Athens, Athens' main city to its ports at Piraeus and Phalerum, ...

*Battle of Salamis in Cyprus (450 BC)

The Wars of the Delian League (477–449 BC) were a series of campaigns fought between the Delian League of Classical Athens, Athens and her allies (and later subjects), and the Achaemenid Empire of Ancient Persia, Persia. These conflicts re ...

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * Matteo Zaccarini, The Lame Hegemony. Cimon of Athens and the Failure of Panhellenism ca. 478–450 BC, Bologna, Bononia University Press, 2017Further reading

* *External links

Cimon of Athens

, in

About.com

Dotdash Meredith (formerly The Mining Company, About.com and Dotdash) is an American digital media company based in New York City. The company publishes online articles and videos about various subjects across categories including health, hom ...

.

* Plutarch

Plutarch (; , ''Ploútarchos'', ; – 120s) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo (Delphi), Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''Parallel Lives'', ...

'The ''Life of Cimon'' in English

at the ''Internet Classics Archive'' {{Authority control 510s BC births 450 BC deaths 5th-century BC Athenians Athenians of the Greco-Persian Wars Ostracized Athenians Proxenoi Ancient Athenian generals Ancient Athenian admirals Philaidae 5th-century BC Greek politicians