Kenomagnathus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Kenomagnathus'' (meaning "gap jaw", in reference to the

In 1965, Robert Carroll found another articulated partial skeleton in the same locality. Philip Currie attributed this skeleton to the primitive sphenacodontid of Peabody in 1977, and recognized it as a new species of ''

In 1965, Robert Carroll found another articulated partial skeleton in the same locality. Philip Currie attributed this skeleton to the primitive sphenacodontid of Peabody in 1977, and recognized it as a new species of ''

Among close relatives, ''Kenomagnathus'' can be distinguished by its tall snout, judging by the maxilla and especially the lacrimal. The projection at the front of the lacrimal would have formed a large part of the rear border of the bony nostrils. In ''"H." garnettensis'', the lacrimal still contributed to the border, but with a narrow projection. From below, the upward projection at the front of the maxilla would also have contributed to the border of the nostrils, but the angle of this projection differed from ''"H." garnettensis''. The height of the lacrimal, which bordered the front of the eye socket, also implies that ''Kenomagnathus'' had large eyes.

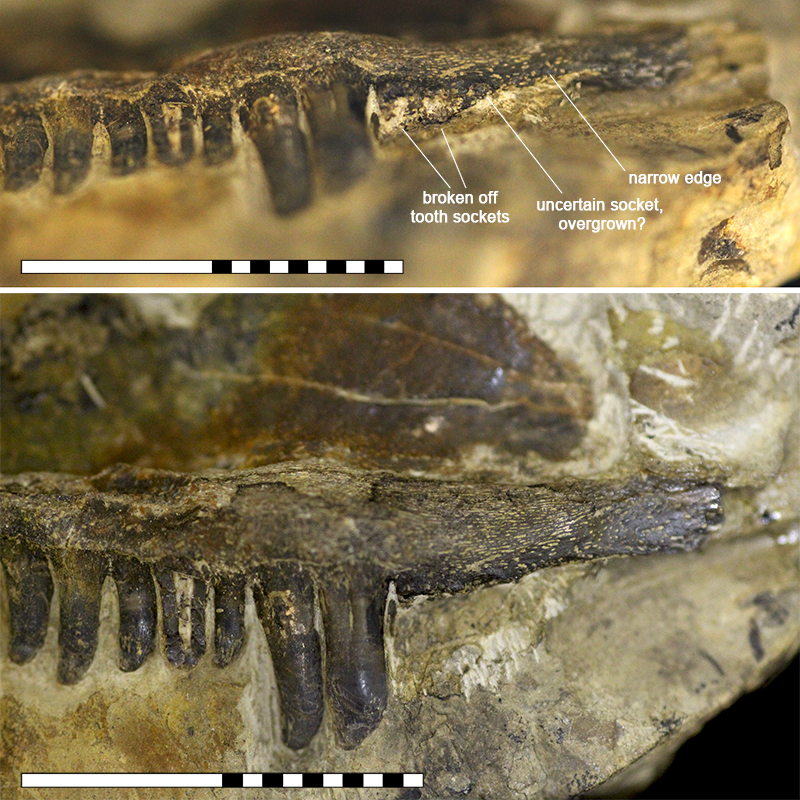

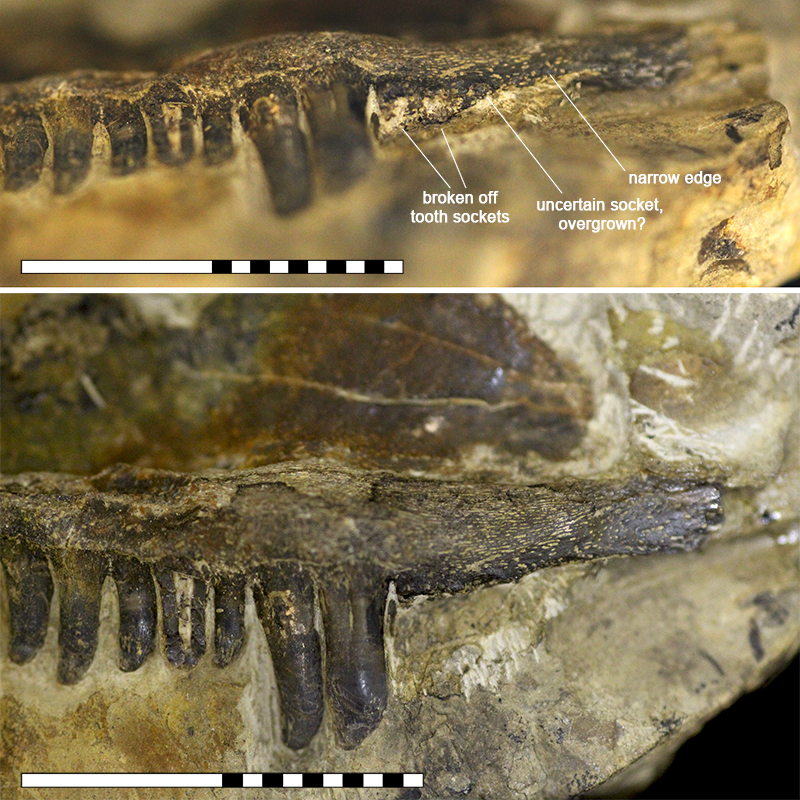

The tooth-bearing bottom margin of the maxilla in ''Kenomagnathus'' was more convex than ''"H." garnettensis'', and is unique in that it lacked a concave region (or "precanine step"). Another distinguishing characteristic is the diastema, a toothless region spanning the width of three teeth at the front of the maxilla, where the bone noticeably thinned and could not have borne tooth sockets. Behind the diastema were two precanine teeth, two large

Among close relatives, ''Kenomagnathus'' can be distinguished by its tall snout, judging by the maxilla and especially the lacrimal. The projection at the front of the lacrimal would have formed a large part of the rear border of the bony nostrils. In ''"H." garnettensis'', the lacrimal still contributed to the border, but with a narrow projection. From below, the upward projection at the front of the maxilla would also have contributed to the border of the nostrils, but the angle of this projection differed from ''"H." garnettensis''. The height of the lacrimal, which bordered the front of the eye socket, also implies that ''Kenomagnathus'' had large eyes.

The tooth-bearing bottom margin of the maxilla in ''Kenomagnathus'' was more convex than ''"H." garnettensis'', and is unique in that it lacked a concave region (or "precanine step"). Another distinguishing characteristic is the diastema, a toothless region spanning the width of three teeth at the front of the maxilla, where the bone noticeably thinned and could not have borne tooth sockets. Behind the diastema were two precanine teeth, two large

In 2020, Spindler identified three characteristics that placed ''Kenomagnathus'' in the

In 2020, Spindler identified three characteristics that placed ''Kenomagnathus'' in the

Modern mammals (except whales) commonly exhibit

Modern mammals (except whales) commonly exhibit

Spindler likened ''Kenomagnathus'' to the enigmatic synapsid ''

Spindler likened ''Kenomagnathus'' to the enigmatic synapsid ''

diastema

A diastema (: diastemata, from Greek , 'space') is a space or gap between two teeth. Many species of mammals have diastemata as a normal feature, most commonly between the incisors and molars. More colloquially, the condition may be referred to ...

in its upper tooth row) is a genus of synapsid

Synapsida is a diverse group of tetrapod vertebrates that includes all mammals and their extinct relatives. It is one of the two major clades of the group Amniota, the other being the more diverse group Sauropsida (which includes all extant rept ...

belonging to the Sphenacodontia

Sphenacodontia is a stem-based taxon, stem-based clade of derived synapsids. It was defined by Amson and Laurin (2011) as "the largest clade that includes ''Haptodus baylei'', ''Haptodus garnettensis'' and ''Sphenacodon ferox'', but not ''Edaphos ...

, which lived during the Pennsylvanian Pennsylvanian may refer to:

* A person or thing from Pennsylvania

* Pennsylvanian (geology)

The Pennsylvanian ( , also known as Upper Carboniferous or Late Carboniferous) is, on the International Commission on Stratigraphy, ICS geologic timesc ...

subperiod of the Carboniferous

The Carboniferous ( ) is a Geologic time scale, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), system of the Paleozoic era (geology), era that spans 60 million years, from the end of the Devonian Period Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the ...

in what is now Garnett, Kansas

Garnett is a city in and the county seat of Anderson County, Kansas, United States. As of the 2020 census, the population of the city was 3,242.

History

Garnett was platted in 1857. Garnett is named for W. A. Garnett, a native of Louisville ...

, United States. It contains one species, ''Kenomagnathus scottae'', based on a specimen consisting of the maxilla

In vertebrates, the maxilla (: maxillae ) is the upper fixed (not fixed in Neopterygii) bone of the jaw formed from the fusion of two maxillary bones. In humans, the upper jaw includes the hard palate in the front of the mouth. The two maxil ...

and lacrimal bone

The lacrimal bones are two small and fragile bones of the facial skeleton; they are roughly the size of the little fingernail and situated at the front part of the medial wall of the orbit. They each have two surfaces and four borders. Several bon ...

s of the skull, which was catalogued as ROM 43608 and originally classified as belonging to '' "Haptodus" garnettensis''. Frederik Spindler named it as a new genus in 2020.

Discovery and naming

Norman Newell discovered a fossil locality nearGarnett, Kansas

Garnett is a city in and the county seat of Anderson County, Kansas, United States. As of the 2020 census, the population of the city was 3,242.

History

Garnett was platted in 1857. Garnett is named for W. A. Garnett, a native of Louisville ...

, United States in 1931, belonging to the Rock Lake Member of the Stanton Formation. Around 1932, Henry Lane and Claude Hibbard had collected a variety of animal and plant fossils from the locality. Among these were skeletons of ''Petrolacosaurus

''Petrolacosaurus'' ("rock lake lizard") is an extinct genus of diapsid reptile from the late Carboniferous period. It was a small, long reptile, and one of the earliest known reptiles with two temporal fenestrae (holes at the rear part of the ...

'', which were subsequently described in 1952 by Frank Peabody

Frank Elmer Peabody (28 August 1914 - 27 June 1958), was an American palaeontologist noted for his research on fossil trackways and reptile and amphibian skeletal structure.

He attended high school and junior college in the San Francisco Bay Are ...

. Hoping to find more material, a field team from the University of Kansas Natural History Museum

The University of Kansas Natural History Museum is part of the University of Kansas Biodiversity Institute, a KU designated research center dedicated to the study of the life of the planet.

The museum's galleries are in Dyche Hall on the uni ...

conducted further excavations in 1953 and 1954; they found trackways, coelacanth

Coelacanths ( ) are an ancient group of lobe-finned fish (Sarcopterygii) in the class Actinistia. As sarcopterygians, they are more closely related to lungfish and tetrapods (the terrestrial vertebrates including living amphibians, reptiles, bi ...

fish, several additional ''Petrolacosaurus'' skeletons, and "pelycosaur

Pelycosaur ( ) is an older term for basal or primitive Late Paleozoic synapsids, excluding the therapsids and their descendants. Previously, the term mammal-like reptile was used, and Pelycosauria was considered an order, but this is now thoug ...

" (early-diverging synapsid

Synapsida is a diverse group of tetrapod vertebrates that includes all mammals and their extinct relatives. It is one of the two major clades of the group Amniota, the other being the more diverse group Sauropsida (which includes all extant rept ...

) fossils representing three genera. One of these was a partial skeleton that distinctly differed from the others; when Peabody reported on these discoveries in 1957 paper, he observed that the skeleton was of a primitive sphenacodontid

Sphenacodontidae (Greek: "wedge point tooth family") is an extinct family of sphenacodontoid synapsids. Small to large, advanced, carnivorous, Late Pennsylvanian to middle Permian "pelycosaurs". The most recent one, ''Dimetrodon angelensis'', is ...

, but deferred its description to a later time.

In 1965, Robert Carroll found another articulated partial skeleton in the same locality. Philip Currie attributed this skeleton to the primitive sphenacodontid of Peabody in 1977, and recognized it as a new species of ''

In 1965, Robert Carroll found another articulated partial skeleton in the same locality. Philip Currie attributed this skeleton to the primitive sphenacodontid of Peabody in 1977, and recognized it as a new species of ''Haptodus

''Haptodus'' is an extinct genus of basal sphenacodonts, a member of the clade that includes therapsids and hence, mammals. It was at least in length. It lived in present-day France during the Early Permian. It was a medium-sized predator, fe ...

'', which he named ''Haptodus garnettensis

''Haptodus'' is an extinct genus of basal sphenacodonts, a member of the clade that includes therapsids and hence, mammals. It was at least in length. It lived in present-day France during the Early Permian. It was a medium-sized predator, fe ...

''. However, up until that point, all specimens of ''H. garnettensis'' were either badly crushed or immature. Throughout the 1980s, a number of additional specimens were discovered at the locality, including adult and subadult specimens. This allowed Michel Laurin

Michel Laurin is a Canadian-born French vertebrate paleontologist whose specialities include the emergence of a land-based lifestyle among vertebrates, the evolution of body size and the origin and phylogeny of lissamphibians. He has also made impo ...

to identify distinguishing characteristics for ''H. garnettensis'' and to incorporate it into a phylogenetic analysis, which found it to be outside the Sphenacodontidae. He published these results in 1993. Among the additional specimens was a partial skull consisting of a left maxilla

In vertebrates, the maxilla (: maxillae ) is the upper fixed (not fixed in Neopterygii) bone of the jaw formed from the fusion of two maxillary bones. In humans, the upper jaw includes the hard palate in the front of the mouth. The two maxil ...

and lacrimal, which were catalogued in the Royal Ontario Museum

The Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) is a museum of art, world culture and natural history in Toronto, Ontario, Canada. It is one of the largest museums in North America and the largest in Canada. It attracts more than one million visitors every year ...

(ROM) as ROM 43608.

Analyses of specimens assigned to ''H. garnettensis'' by Frederik Spindler and colleagues later suggested that there was not one but between four and six distinct taxa

In biology, a taxon (back-formation from ''taxonomy''; : taxa) is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. Although neither is required, a taxon is usually known by a particular name and ...

among them, which primarily differed in their jaws and teeth. They also recognized differences between ''"H." garnettensis'' and the type species

In International_Code_of_Zoological_Nomenclature, zoological nomenclature, a type species (''species typica'') is the species name with which the name of a genus or subgenus is considered to be permanently taxonomically associated, i.e., the spe ...

of ''Haptodus'', ''H. baylei''. In a 2013 conference presentation, Spindler, Kirstin Brink, and Graciela Piñeiro suggested that this variation was based on diet, making these taxa a prehistoric analogue of Darwin's finches

Darwin's finches (also known as the Galápagos finches) are a group of about 18 species of passerine birds. They are well known for being a classic example of adaptive radiation and for their remarkable diversity in beak form and function. They ...

. Spindler formally named ROM 43608 as belonging to a new genus and species in 2020, which he named ''Kenomagnathus scottae''. The generic name ''Kenomagnathus'' is derived from the Greek words κένωμα ("gap") and γνάθος ("jaw"), referencing the diastema

A diastema (: diastemata, from Greek , 'space') is a space or gap between two teeth. Many species of mammals have diastemata as a normal feature, most commonly between the incisors and molars. More colloquially, the condition may be referred to ...

(gap) in its tooth row. Meanwhile, the specific name Specific name may refer to:

* in Database management systems, a system-assigned name that is unique within a particular database

In taxonomy, either of these two meanings, each with its own set of rules:

* Specific name (botany), the two-part (bino ...

''scottae'' honours Diane Scott, a fossil preparator at the University of Toronto Mississauga

The University of Toronto Mississauga (abbreviated as U of T Mississauga or UTM) is the second-largest division of the University of Toronto and one of its three campuses, located in Mississauga, Ontario, Canada.

Established in 1967, the campus ...

who "greatly helped with teaching and specimen handling", inspired Spindler's research, and further prepared the specimen in 2013.

Description

Among close relatives, ''Kenomagnathus'' can be distinguished by its tall snout, judging by the maxilla and especially the lacrimal. The projection at the front of the lacrimal would have formed a large part of the rear border of the bony nostrils. In ''"H." garnettensis'', the lacrimal still contributed to the border, but with a narrow projection. From below, the upward projection at the front of the maxilla would also have contributed to the border of the nostrils, but the angle of this projection differed from ''"H." garnettensis''. The height of the lacrimal, which bordered the front of the eye socket, also implies that ''Kenomagnathus'' had large eyes.

The tooth-bearing bottom margin of the maxilla in ''Kenomagnathus'' was more convex than ''"H." garnettensis'', and is unique in that it lacked a concave region (or "precanine step"). Another distinguishing characteristic is the diastema, a toothless region spanning the width of three teeth at the front of the maxilla, where the bone noticeably thinned and could not have borne tooth sockets. Behind the diastema were two precanine teeth, two large

Among close relatives, ''Kenomagnathus'' can be distinguished by its tall snout, judging by the maxilla and especially the lacrimal. The projection at the front of the lacrimal would have formed a large part of the rear border of the bony nostrils. In ''"H." garnettensis'', the lacrimal still contributed to the border, but with a narrow projection. From below, the upward projection at the front of the maxilla would also have contributed to the border of the nostrils, but the angle of this projection differed from ''"H." garnettensis''. The height of the lacrimal, which bordered the front of the eye socket, also implies that ''Kenomagnathus'' had large eyes.

The tooth-bearing bottom margin of the maxilla in ''Kenomagnathus'' was more convex than ''"H." garnettensis'', and is unique in that it lacked a concave region (or "precanine step"). Another distinguishing characteristic is the diastema, a toothless region spanning the width of three teeth at the front of the maxilla, where the bone noticeably thinned and could not have borne tooth sockets. Behind the diastema were two precanine teeth, two large canine teeth

In mammalian oral anatomy, the canine teeth, also called cuspids, dogteeth, eye teeth, vampire teeth, or fangs, are the relatively long, pointed teeth. In the context of the upper jaw, they are also known as '' fangs''. They can appear more fl ...

, and at least fourteen post-canine teeth (eleven being preserved). There were two weakly thickened regions, or buttresses, on the maxilla, with one above the canines and one further back. Due to the shortness of the maxilla, the canines were located further forward than in close relatives. Like ''"H." garnettensis'', ''Kenomagnathus'' had tall and nearly straight teeth, with striations on the inner surfaces of the teeth reaching the tips, but those of ''Kenomagnathus'' were more slender and blunter at the tip.

Classification

In 2020, Spindler identified three characteristics that placed ''Kenomagnathus'' in the

In 2020, Spindler identified three characteristics that placed ''Kenomagnathus'' in the Sphenacodontia

Sphenacodontia is a stem-based taxon, stem-based clade of derived synapsids. It was defined by Amson and Laurin (2011) as "the largest clade that includes ''Haptodus baylei'', ''Haptodus garnettensis'' and ''Sphenacodon ferox'', but not ''Edaphos ...

: the blunt teeth, the convex bottom margin of the maxilla, and the height of the lacrimal and the upward projection of the maxilla. However, based on the contribution of the lacrimal to the border of the bony nostrils, ''Kenomagnathus'' was excluded from the more restrictive group Sphenacodontoidea

Sphenacodontoidea is a node-based clade that is defined to include the most recent common ancestor of Sphenacodontidae and Therapsida and its descendants (including mammals). Sphenacodontoids are characterised by a number of synapomorphies co ...

. Within this evolutionary grade

A grade is a taxon united by a level of morphological or physiological complexity. The term was coined by British biologist Julian Huxley, to contrast with clade, a strictly phylogenetic unit.

Phylogenetics

The concept of evolutionary grades ...

of "haptodontine" sphenacodontians, the fragmentary nature of specimens has complicated the resolution of their relationships. This is exacerbated by the fact that many "haptodontines" are very similar to each other save for differences in their teeth and skull proportions.

For his 2015 thesis, Spindler conducted a preliminary phylogenetic analysis

In biology, phylogenetics () is the study of the evolutionary history of life using observable characteristics of organisms (or genes), which is known as phylogenetic inference. It infers the relationship among organisms based on empirical data ...

of "haptodontines", based on a new set of characteristics that he assembled to resolve their relationships. After defining the specimens associated with ''"H." garnettensis'' as opposed to ''Kenomagnathus'' and a taxon he named "Tenuacaptor reiszi", he could not resolve whether ''Kenomagnathus'' or ''Ianthodon

''Ianthodon'' is an extinct genus of basal haptodontiform synapsids from the Late Carboniferous about 304 million years ago. The taxon was discovered and named by Kissel & Reisz in 2004.Kissel, R. A. & Reisz, R. R. ''Synapsid fauna of the Upper ...

'' was more basal (less specialized). Removing "Tenuacaptor" produced a more derived (more specialized) position for both ''Kenomagnathus'' and ''"H." garnettensis'' inside the Sphenacodontia. Phylogenetic tree

A phylogenetic tree or phylogeny is a graphical representation which shows the evolutionary history between a set of species or taxa during a specific time.Felsenstein J. (2004). ''Inferring Phylogenies'' Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, MA. In ...

s illustrating both phylogenetic hypotheses are shown below.

Topology A: All genera and characteristics

Topology B: With "Tenuacaptor" and some tooth-based characteristics removed

Evolutionary history

Modern mammals (except whales) commonly exhibit

Modern mammals (except whales) commonly exhibit heterodont

In anatomy, a heterodont (from Greek, meaning 'different teeth') is an animal which possesses more than a single tooth morphology.

Human dentition is heterodont and diphyodont as an example.

In vertebrates, heterodont pertains to animals wher ...

teeth, or teeth of several different types. Among the extinct relatives (stem group

In phylogenetics, the crown group or crown assemblage is a collection of species composed of the living representatives of the collection, the most recent common ancestor of the collection, and all descendants of the most recent common ancestor. ...

) of mammals, there is a gradient from animals with isodont (uniform) teeth to animals with heterodont teeth, associated with the development of distinct "zones" along the tooth row. Canine-like teeth — double canines like that of ''Kenomagnathus'' in particular — are common among basal synapsids and also other basal amniotes, along with the enlargement of the first premaxilla

The premaxilla (or praemaxilla) is one of a pair of small cranial bones at the very tip of the upper jaw of many animals, usually, but not always, bearing teeth. In humans, they are fused with the maxilla. The "premaxilla" of therian mammals h ...

ry tooth at the front of the skull. There is a morphological gap between basal synapsids like ''"Haptodus" garnettensis'', which have precanine teeth but less tooth variation over all, and therapsids (which are closer to mammals), which have no precanine teeth, only one set of canines, and more subtle tooth variation. Precanine teeth are often replaced by a large diastema in therapsids.

''Kenomagnathus'' had both precanine teeth and a diastema, which fills the gap between basal synapsids and therapsids to some extent. It reflects what would have been an ongoing transition, which other stem-mammals with diastemata would also have gone through. Spindler hypothesized that the diastema initially developed as a consequence of the maxilla and premaxilla being angled against each other by the precanine step, which would have prevented the precanine teeth from growing longer; this is seen as an "initial diastema" in ''"H." garnettensis'', ''Ianthasaurus'', and ''Ianthodon''. This would have allowed the corresponding canines on the lower jaw to grow longer and fill the gap, which in turn would have led to a full diastema. However, Spindler also noted that the relationship between the development of the precanine step, tooth loss, and the diastema was unclear, and that the feeding styles of these animals may also have had an effect.

Paleobiology

Spindler likened ''Kenomagnathus'' to the enigmatic synapsid ''

Spindler likened ''Kenomagnathus'' to the enigmatic synapsid ''Tetraceratops

''Tetraceratops insignis'' ("four-horned face emblem") is an extinct synapsid from the Early Permian that was formerly considered the earliest known representative of Therapsida, a group that includes mammals and their close extinct relatives. It ...

'', as both had short faces, large eyes, and a diastema in their jaws. While this implies that the skulls of both were specialized for food processing, Spindler noted that further comparisons "cover a wide range of possibilities". In particular, ''Tetraceratops'' was highly specialized; the diastema in ''Tetraceratops'' does not line up with the position of the lower canines, but is located slightly behind it, and the first premaxillary tooth would have jutted out from the front of the jaws when they were closed. Spindler suggested in 2019 that ''Tetraceratops'' was durophagous

Durophagy is the eating behavior of animals that consume hard-shelled or exoskeleton-bearing organisms, such as corals, shelled mollusks, or crabs. It is mostly used to describe fish, but is also used when describing reptiles, including fossil t ...

(i.e. it fed on hard-shelled prey), based primarily on its teeth. He inferred a similar lifestyle for ''Kenomagnathus'' based on its tall skull in 2020, and suggested that the diastema of ''Kenomagnathus'' may have been covered by rigid tissue, against which a potentially enlargened lower tooth would have pressed to crush prey items.

Paleoecology

The rocks that ''Kenomagnathus'' was found in originate from the base of the Rock Lake Member of the Stanton Formation, which is in turn part of the Lansing Group. These rocks have been assigned to the LatePennsylvanian Pennsylvanian may refer to:

* A person or thing from Pennsylvania

* Pennsylvanian (geology)

The Pennsylvanian ( , also known as Upper Carboniferous or Late Carboniferous) is, on the International Commission on Stratigraphy, ICS geologic timesc ...

subperiod of the Carboniferous

The Carboniferous ( ) is a Geologic time scale, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), system of the Paleozoic era (geology), era that spans 60 million years, from the end of the Devonian Period Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the ...

period

Period may refer to:

Common uses

* Period (punctuation)

* Era, a length or span of time

*Menstruation, commonly referred to as a "period"

Arts, entertainment, and media

* Period (music), a concept in musical composition

* Periodic sentence (o ...

, specifically near the transition between the Kasimovian

The Kasimovian is a geochronologic age or chronostratigraphic stage in the ICS geologic timescale. It is the third stage in the Pennsylvanian (late Carboniferous), lasting from to Ma.; 2004: ''A Geologic Time Scale 2004'', Cambridge Unive ...

and Gzhelian

The Gzhelian ( ) is an age in the ICS geologic time scale or a stage in the stratigraphic column. It is the youngest stage of the Pennsylvanian, the youngest subsystem of the Carboniferous. The Gzhelian lasted from to Ma. It follows the Ka ...

ages Ages may refer to:

*Advanced glycation end-products, known as AGEs

*Ages, Kentucky, census-designated place, United States

* ''Ages'' (album) by German electronic musician Edgar Froese

*The geologic time scale, a system of chronological measuremen ...

around 304 Ma (million years ago).

At the Garnett locality, the base of the Rock Lake Member consists of carbonaceous calcareous

Calcareous () is an adjective meaning "mostly or partly composed of calcium carbonate", in other words, containing lime (mineral), lime or being chalky. The term is used in a wide variety of Science, scientific disciplines.

In zoology

''Calcare ...

mudstone

Mudstone, a type of mudrock, is a fine-grained sedimentary rock whose original constituents were clays or muds. Mudstone is distinguished from ''shale'' by its lack of fissility.Blatt, H., and R.J. Tracy, 1996, ''Petrology.'' New York, New York, ...

(i.e. mudstone containing organic matter and calcium carbonate) that is moderately layered and dark greyish-brown in color. Plant fossils in these rocks are dominated by the conifer

Conifers () are a group of conifer cone, cone-bearing Spermatophyte, seed plants, a subset of gymnosperms. Scientifically, they make up the phylum, division Pinophyta (), also known as Coniferophyta () or Coniferae. The division contains a sin ...

s '' Lebachia'' and ''Walchia

''Walchia'' is a primitive fossil conifer found in upper Pennsylvanian (geology), Pennsylvanian (Carboniferous) and lower Permian (about 310-290 Mya (unit), Mya) rocks of Europe and North America. A forest of In situ, in-situ Walchia tree-stumps ...

'', along with smaller plants like the fern

The ferns (Polypodiopsida or Polypodiophyta) are a group of vascular plants (plants with xylem and phloem) that reproduce via spores and have neither seeds nor flowers. They differ from mosses by being vascular, i.e., having specialized tissue ...

s '' Dichophyllum'', the seed fern

In botany, a seed is a plant structure containing an embryo and stored nutrients in a protective coat called a ''testa''. More generally, the term "seed" means anything that can be sown, which may include seed and husk or tuber. Seeds are the ...

s '' Alethopteris'', ''Neuropteris

''Neuropteris'' is an extinct seed fern that existed in the Carboniferous period, known only from fossils.

Gallery

File:Neuropteris flexuosa kz01.jpg, ''N. flexuosa''

File:Neuropteris flexuosa fossil plant (Mazon Creek Lagerstatte, Francis ...

'', and ''Taeniopteris

''Taeniopteris'' is an Extinction, extinct form genus of Mesozoic vascular plant leaves, perhaps representing those of Cycad, cycads, Bennettitales, bennettitaleans, or Marattiales, marattialean ferns. The form genus is almost certainly a polyphy ...

'', the cycad

Cycads are seed plants that typically have a stout and woody (ligneous) trunk (botany), trunk with a crown (botany), crown of large, hard, stiff, evergreen and (usually) pinnate leaves. The species are dioecious, that is, individual plants o ...

'' Spermopteris'', the horsetail

''Equisetum'' (; horsetail) is the only living genus in Equisetaceae, a family of vascular plants that reproduce by spores rather than seeds.

''Equisetum'' is a "living fossil", the only living genus of the entire subclass Equisetidae, which ...

''Annularia

''Annularia'' is a form taxon, applied to fossil foliage belonging to extinct plants of the genus ''Calamites'' in the order Equisetales.

Description

''Annularia'' is a form taxon name given to leaves of ''Calamites''. In that species, the leav ...

'', and the gymnosperm

The gymnosperms ( ; ) are a group of woody, perennial Seed plant, seed-producing plants, typically lacking the protective outer covering which surrounds the seeds in flowering plants, that include Pinophyta, conifers, cycads, Ginkgo, and gnetoph ...

''Cordaites

''Cordaites'' is a genus of extinct gymnosperms, related to or actually representing the earliest conifers. These trees grew up to tall and stood in dry areas as well as wetlands. Brackish water mussels and crustacea are found frequently betwee ...

''. At the top of these rocks is a layer of marine bivalve

Bivalvia () or bivalves, in previous centuries referred to as the Lamellibranchiata and Pelecypoda, is a class (biology), class of aquatic animal, aquatic molluscs (marine and freshwater) that have laterally compressed soft bodies enclosed b ...

fossils measuring thick, which were likely deposited at high tide. Collectively, this implies that ''Kenomagnathus'' lived on a coastal plain

A coastal plain (also coastal plains, coastal lowland, coastal lowlands) is an area of flat, low-lying land adjacent to a sea coast. A fall line commonly marks the border between a coastal plain and an upland area.

Formation

Coastal plains can f ...

in a coniferous forest. Towards the top of the Rock Lake Member, the rock layers become more irregular, and fossils of land animals and plants are increasingly replaced by fossils of marine invertebrates, implying that estuarine

An estuary is a partially enclosed coastal body of brackish water with one or more rivers or streams flowing into it, and with a free connection to the open sea. Estuaries form a transition zone between river environments and maritime environm ...

waters gradually flooded the region as sea levels rose.

The Garnett locality has produced several basal synapsids, including the "haptodontines" ''Kenomagnathus'', ''"H." garnettensis'', "Tenuacaptor", and ''Ianthodon''; the edaphosaurid

Edaphosauridae is a family of mostly large (up to or more) Late Carboniferous to Early Permian synapsids. Edaphosaur fossils are so far known only from North America and Europe.

Characteristics

They were the earliest known herbivorous amniotes ...

''Ianthasaurus

''Ianthasaurus'' is an extinct genus of small edaphosaurids from the Late Carboniferous.

Description

It is one of the smallest edaphosaurids known, with an skull and a total body length of . ''Ianthasaurus'' lacks many of the spectacular speci ...

''; the enigmatic synapsid '' Xyrospondylus'', which may also be an edaphosaurid; an undescribed member of Ophiacodontidae

Ophiacodontidae is an extinct family of early synapsids from the Carboniferous and Permian. '' Archaeothyris'', and '' Clepsydrops'' were among the earliest ophiacodontids, appearing in the Late Carboniferous. Ophiacodontids are among the most b ...

that has been assigned to ''Ophiacodon

''Ophiacodon'' (meaning "snake tooth") is an extinct genus of synapsid belonging to the family Ophiacodontidae that lived from the Late Carboniferous to the Early Permian in North America and Europe. The genus was named along with its type specie ...

'' and ''Clepsydrops

''Clepsydrops'' is an extinct genus of primitive synapsids from the early Late Carboniferous that was related to ''Archaeothyris''. The name means 'hour-glass appearance' (Greek ''klepsydra'' = "hourglass" + Greek ''ops'' = "eye, face, appearanc ...

''; and possibly another sphenacodontian. ''Petrolacosaurus'' is the most common reptile, known from nearly fifty specimens; a possible member of the Protorothyrididae

Protorothyrididae is an extinct family (biology), family of small, lizard-like reptiles belonging to Eureptilia. Their skulls did not have Fenestra (anatomy), fenestrae, like the more derived diapsids. Protorothyridids lived from the Late Carbon ...

is also known from tracks. Only the amphibian ''Actiobates

''Actiobates'' is an extinct genus of trematopid temnospondyl that lived during the Late Carboniferous. It is known from the Garnett Quarry in Kansas.

History of study

''Actiobates peabodyi'' was named in 1973 by Theodore Eaton. The genus name ...

'' is known, while the fish consist of the coelacanth '' Synaptotylus'', a larger coelacanth, and xenacanthid sharks. Invertebrates include insects like '' Euchoroptera'' and '' Parabrodia''; the scorpion '' Garnettius''; the bivalves '' Myalinella'', '' Sedgwickia'', and ''Yoldia

''Yoldia'' is a genus of marine bivalve mollusks in the family (biology), family Yoldiidae. Some former members of the genus are now known as ''Portlandia (bivalve), Portlandia''. The genus was named after , Conde de Yoldi (1764–1852), a Spani ...

''; the brachiopods

Brachiopods (), phylum Brachiopoda, are a phylum of animals that have hard "valves" (shells) on the upper and lower surfaces, unlike the left and right arrangement in bivalve molluscs. Brachiopod valves are hinged at the rear end, while the fron ...

'' Composita'', '' Lingula'', and '' Neospirifer''; and bryozoans, serpulid

The Serpulidae are a family of sessile, tube-building annelid worms in the class Polychaeta. The members of this family differ from other sabellid tube worms in that they have a specialized operculum that blocks the entrance of their tubes wh ...

worms, trilobite

Trilobites (; meaning "three-lobed entities") are extinction, extinct marine arthropods that form the class (biology), class Trilobita. One of the earliest groups of arthropods to appear in the fossil record, trilobites were among the most succ ...

s, crinoid

Crinoids are marine invertebrates that make up the class Crinoidea. Crinoids that remain attached to the sea floor by a stalk in their adult form are commonly called sea lilies, while the unstalked forms, called feather stars or comatulids, are ...

s, sea urchin

Sea urchins or urchins () are echinoderms in the class (biology), class Echinoidea. About 950 species live on the seabed, inhabiting all oceans and depth zones from the intertidal zone to deep seas of . They typically have a globular body cove ...

s, rugosa

The Rugosa or rugose corals are an extinct Class (biology), class of solitary and Colony (biology), colonial corals that were abundant in Middle Ordovician to Late Permian seas.

Solitary rugosans (e.g., ''Caninia (genus), Caninia'', ''Lopho ...

n corals, and sponge

Sponges or sea sponges are primarily marine invertebrates of the animal phylum Porifera (; meaning 'pore bearer'), a basal clade and a sister taxon of the diploblasts. They are sessile filter feeders that are bound to the seabed, and a ...

s. Spindler speculated that ''Kenomagnathus'' may have fed on bivalves.

References

{{Taxonbar, from=Q85773997 Sphenacodontia Carboniferous synapsids of North America Kasimovian life Paleontology in Kansas Fossil taxa described in 2020