Kajkavian dialect on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Kajkavian is a South Slavic supradialect or

The Kajkavian speech area borders in the northwest on the

The Kajkavian speech area borders in the northwest on the

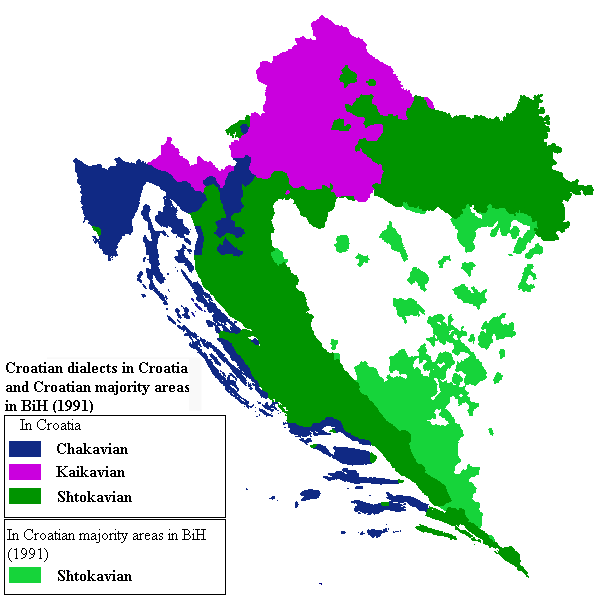

Kajkavian is mainly spoken in northern and northwestern Croatia. The mixed half-Kajkavian towns along the eastern and southern edge of the Kajkavian-speaking area are Pitoma─Źa,

Kajkavian is mainly spoken in northern and northwestern Croatia. The mixed half-Kajkavian towns along the eastern and southern edge of the Kajkavian-speaking area are Pitoma─Źa,

Mali Princ je pregovoril kajkavski! ÔÇô Umjesto kave 15. prosinca 2018. (bozicabrkan.com)

/ref> Below are examples of the

Bednjanski govor

'', Hrvatski dijalektološki zbornik, Yugoslav Academy of Sciences and Arts

language

Language is a structured system of communication that consists of grammar and vocabulary. It is the primary means by which humans convey meaning, both in spoken and signed language, signed forms, and may also be conveyed through writing syste ...

spoken primarily by Croats

The Croats (; , ) are a South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and other neighboring countries in Central Europe, Central and Southeastern Europe who share a common Croatian Cultural heritage, ancest ...

in much of Central Croatia and Gorski Kotar.

It is part of the South Slavic dialect continuum

A dialect continuum or dialect chain is a series of Variety (linguistics), language varieties spoken across some geographical area such that neighboring varieties are Mutual intelligibility, mutually intelligible, but the differences accumulat ...

, being transitional to the supradialects of ─îakavian

Chakavian or ─îakavian (, , , proper name: or own name: ''─Źokovski, ─Źakavski, ─Źekavski'') is a South Slavic languages, South Slavic supradialect or language spoken by Croats along the Adriatic coast, in the historical regions of Dalmati ...

, Štokavian and the Slovene language. There are differing opinions over whether Kajkavian is best considered a dialect of the Serbo-Croatian

Serbo-Croatian ( / ), also known as Bosnian-Croatian-Montenegrin-Serbian (BCMS), is a South Slavic language and the primary language of Serbia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Montenegro. It is a pluricentric language with four mutually i ...

language or a fully-fledged language of its own, as it is only partially mutually intelligible with either Čakavian or Štokavian and bears more similarities to Slovene; it is transitional to and fully mutually intelligible

In linguistics, mutual intelligibility is a relationship between different but related language varieties in which speakers of the different varieties can readily understand each other without prior familiarity or special effort. Mutual intellig ...

with Prekmurje Slovene

Prekmurje Slovene, also known as the Prekmurje dialect, Eastern Slovene, or Wendish (, , Prekmurje Slovene: ''prekm├╝rski jezik, prekm├╝r┼í─Źina, prekm├Âr┼í─Źina, prekm├Ârski jezik, panonska sloven┼í─Źina''), is the language of Prekmurje in Easte ...

and the dialects in Slovenian Lower Styria's region of Prlekija in terms of phonology and vocabulary.

Outside Croatia's northernmost regions, Kajkavian is also spoken in Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

n Burgenland

Burgenland (; ; ; Bavarian language, Austro-Bavarian: ''Burgnland''; Slovene language, Slovene: ''Gradi┼í─Źanska''; ) is the easternmost and least populous Bundesland (Austria), state of Austria. It consists of two statutory city (Austria), statut ...

and a number of enclaves in Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

along the Austrian and Croatian border and in Romania

Romania is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It borders Ukraine to the north and east, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Bulgaria to the south, Moldova to ...

.

Name

The term "Kajkavian" and the broader classification of what defines this dialect are relatively modern constructs. The dialect's name originates from the interrogative pronoun "kaj" ("what"). The names of the other supradialects of Serbo-Croatian also originate from their respective variants of the interrogative pronoun. The pronouns are just general indicators and not strict identifiers of the dialects. Some Kajkavian dialects use "─Źa" (common in─îakavian

Chakavian or ─îakavian (, , , proper name: or own name: ''─Źokovski, ─Źakavski, ─Źekavski'') is a South Slavic languages, South Slavic supradialect or language spoken by Croats along the Adriatic coast, in the historical regions of Dalmati ...

), while certain ─îakavian dialects, like the Buzet dialect in Istria

Istria ( ; Croatian language, Croatian and Slovene language, Slovene: ; Italian language, Italian and Venetian language, Venetian: ; ; Istro-Romanian language, Istro-Romanian: ; ; ) is the largest peninsula within the Adriatic Sea. Located at th ...

, use "kaj". The names of these dialects are based on the most common pronoun used, not an absolute rule.

Autonyms used throughout history by various Kajkavian writers have been manifold, ranging from ''Slavic'' (''slavonski'', ''slovenski'', ''slovinski'') to ''Croatian'' (''horvatski'') or '' Illyrian'' (''illirski''). The naming went through several phases, with the Slavic-based name initially being dominant. Over time, the name ''Croatian'' started gaining ground mainly during the 17th century, and by the beginning of the 18th century, it had supplanted the older name ''Slavic''. The name also followed the same evolution in neighboring Slovene Prekmurje

Prekmurje (; Prekmurje Slovene: ''Pr├Ękm├╝rsko'' or ''Pr├Ękm├╝re''; ) is a geographically, linguistically, culturally, and ethnically defined region of Slovenia, settled by Slovenes and a Hungarians in Slovenia, Hungarian minority, lying betwee ...

and some other border areas in what is now Slovenia, although there the name ''Slovene-Croatian'' (''slovensko-horvatski'') existed as well. The actual term Kajkavian (''kajkavski''), including as an adjective, was invented in the 19th century and is credited to Serbian philologist ─Éuro Dani─Źi─ç, while it was generally used and promoted in the 20th century works by Croatian writer Miroslav Krle┼ża. The term is today accepted by its speakers in Croatia.

Classification

Historically, theclassification

Classification is the activity of assigning objects to some pre-existing classes or categories. This is distinct from the task of establishing the classes themselves (for example through cluster analysis). Examples include diagnostic tests, identif ...

of Kajkavian has been a subject of much debate regarding both the question of whether it ought to be considered a dialect or a language, as well as the question of what its relation is to neighboring vernaculars.

The problem with classifying Kajkavian within South Slavic stems in part from its both structural differences and closesness with neighboring Čakavian and Štokavian speeches as well as its historical closeness to Slovene speeches. Some Slavist

Slavic (American English) or Slavonic (British English) studies, also known as Slavistics, is the academic field of area studies concerned with Slavic peoples, languages, literature, history, and culture. Originally, a Slavist or Slavicist was ...

s maintain that when the separation of Western South Slavic speeches happened, they separated into five divergent groups ÔÇö Slovene, Kajkavian, ─îakavian, Western ┼átokavian and Eastern ┼átokavian, as a result of this, throughout history Kajkavian has often been categorized differently, either a node categorized together with Serbo-Croatian or Slovene. Furthermore, there do exist few old isoglosses that separate almost all Slovene speeches from all other Western South Slavic dialects, and do exist innovations exist common to Kajkavian, ─îakavian, and Western ┼átokavian that would separate them from Slovene. Croatian linguist Stjepan Iv┼íi─ç has used Kajkavian vocabulary and accentuation, which significantly differs from that of ┼átokavian, as evidence to be a language in its own right. Josip Sili─ç, one of the main initiators behind the standardisation of Croatian, also regards Kajkavian as a distinct language by dint of its having significantly different morphology, syntax and phonology from the official ┼átokavian-based standard. However, Sili─ç's theorization about three languages and systems of Croatian, based on Ferdinand de Saussure

Ferdinand Mongin de Saussure (; ; 26 November 185722 February 1913) was a Swiss linguist, semiotician and philosopher. His ideas laid a foundation for many significant developments in both linguistics and semiotics in the 20th century. He is wi ...

and Eugenio Coșeriu concepts, is criticized for being exaggerated, incomprehensible and logically non-existent. According to Ranko Matasović, Kajkavian is equally Croatian as Čakavian and Štokavian dialects. Mate Kapović notes that the dialects are practical and provisory linguistic inventions which should not be misunderstood and extrapolated outside the context of the dialect continuum

A dialect continuum or dialect chain is a series of Variety (linguistics), language varieties spoken across some geographical area such that neighboring varieties are Mutual intelligibility, mutually intelligible, but the differences accumulat ...

.

According to Mijo Lon─Źari─ç (1988), the formation of the Proto-Kajkavian linguistic and territorial unit would be around the 10th century (when it separated from Southwestern Slavic), until the 12th century it is a separate node of Croatian-Serbian language family (excluding Slovene), between the 13th and 15th century when formed as a dialect with main features known today, until the end of the 17th century when lost a part of spoken territory (to the South, Southeast and especially to East in Slavonia), and from the 17th-18th century till present time when regained part of lost territory by forming new transitional dialects.

Characteristics

Slovene language

Slovene ( or ) or Slovenian ( ; ) is a South Slavic languages, South Slavic language of the Balto-Slavic languages, Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European languages, Indo-European language family. Most of its 2.5 million speakers are the ...

and in the northeast on the Hungarian language

Hungarian, or Magyar (, ), is an Ugric language of the Uralic language family spoken in Hungary and parts of several neighboring countries. It is the official language of Hungary and one of the 24 official languages of the European Union. Out ...

. In the east and southeast it is bordered by Štokavian dialects roughly along a line that used to serve as the border between Civil Croatia and the Habsburg

The House of Habsburg (; ), also known as the House of Austria, was one of the most powerful dynasties in the history of Europe and Western civilization. They were best known for their inbreeding and for ruling vast realms throughout Europe d ...

Military Frontier

The Military Frontier (; sh-Cyrl-Latn, đĺđżĐśđŻđ░ đ║ĐÇđ░ĐśđŞđŻđ░, Vojna krajina, sh-Cyrl-Latn, đĺđżĐśđŻđ░ đ│ĐÇđ░đŻđŞĐćđ░, Vojna granica, label=none; ; ) was a borderland of the Habsburg monarchy and later the Austrian and Austro-Hungari ...

. Finally, in the southwest, it borders ─îakavian along the Kupa and Dobra rivers. It is thought by M. Lon─Źari─ç that historically these borders extended further to the south and east, for example, the eastern border is thought to have extended at least well into modern-day Slavonia

Slavonia (; ) is, with Dalmatia, Croatia proper, and Istria County, Istria, one of the four Regions of Croatia, historical regions of Croatia. Located in the Pannonian Plain and taking up the east of the country, it roughly corresponds with f ...

to the area around the town of Pakrac and Slatina, while East of it transitional Kajkavian- Štokavian dialects. The transitional dialects during Ottoman invasion and migrations almost completely vanished.

The Croatian capital, Zagreb

Zagreb ( ) is the capital (political), capital and List of cities and towns in Croatia#List of cities and towns, largest city of Croatia. It is in the Northern Croatia, north of the country, along the Sava river, at the southern slopes of the ...

, has historically been a Kajkavian-speaking area, and Kajkavian is still in use by its older and (to a lesser extent) by its younger population. Modern Zagreb speech has come under considerable influence from Štokavian. The vast intermingling of Kajkavian and standard Štokavian in Zagreb and its surroundings has led to problems in defining the underlying structure of those speech-groups. As a result, many of the urban speeches (but not rural ones) have been labelled either ''Kajkavian koine

Koine Greek (, ), also variously known as Hellenistic Greek, common Attic, the Alexandrian dialect, Biblical Greek, Septuagint Greek or New Testament Greek, was the common supra-regional form of Greek spoken and written during the Hellenistic ...

'' or ''KajkavianÔÇô┼átokavian'' rather than Kajkavian or ┼átokavian. Additionally, the forms of speech in use exhibit significant sociolinguistic variation. Research suggests that younger Zagreb-born speakers of the Kajkavian koine tend to consciously use more Kajkavian features when speaking to older people, showing that such features are still in their linguistic inventory even if not used at all times. However, the Kajkavian koine is distinct from Kajkavian as spoken in non-urban areas, and the mixing of ┼átokavian and Kajkavian outside of urban settings is much rarer and less developed. The Kajkavian koine has also been named ''Zagreb ┼átokavian'' by some.

As a result of the previously mentioned mixing of dialects, various Kajkavian features and characteristics have found their way into the standard ┼átokavian (''standard Croatian'') spoken in those areas. For example, some of the prominent features are the fixed stress-based accentual system without distinctive lengths, the merger of /─Ź/ and /─ç/ and of /d┼ż/ and /─Ĺ/, vocabulary differences as well as a different place of stress in words. The Zagreb variety of ┼átokavian is considered by some to enjoy parallel prestige with the prescribed ┼átokavian variety. Because of that, speakers whose native speech is closer to the standard variety often end up adopting the Zagreb speech for various reasons.

Kajkavian is closely related to Slovene ÔÇô and to Prekmurje Slovene

Prekmurje Slovene, also known as the Prekmurje dialect, Eastern Slovene, or Wendish (, , Prekmurje Slovene: ''prekm├╝rski jezik, prekm├╝r┼í─Źina, prekm├Âr┼í─Źina, prekm├Ârski jezik, panonska sloven┼í─Źina''), is the language of Prekmurje in Easte ...

in particular. Higher amounts of correspondences between the two exist in inflection and vocabulary. The speakers of the Prekmurje dialect are Slovenes

The Slovenes, also known as Slovenians ( ), are a South Slavs, South Slavic ethnic group native to Slovenia and adjacent regions in Italy, Austria and Hungary. Slovenes share a common ancestry, Slovenian culture, culture, and History of Slove ...

and Hungarian Slovenes

Hungarian Slovenes ( Slovene: ''Mad┼żarski Slovenci'', ) are an autochthonous ethnic and linguistic Slovene minority living in Hungary. The largest groups are the R├íba Slovenes (, dialectically: ''vogrski Slovenci, b├íkerski Slovenci, por├íbsk ...

who belonged to the Archdiocese of Zagreb during the Habsburg era (until 1918). They used Kajkavian as their liturgical language, and by the 18th century, Kajkavian had become the standard language of Prekmurje. Moreover, literary Kajkavian was also used in neighboring Slovene Styria during the 17th and 18th centuries, and in parts of it, education was conducted in Kajkavian.

As a result of various factors, Kajkavian has numerous differences compared to Štokavian:

* Kajkavian has a prothetic ''v-'' generalized in front of ''u'' (compare Kajkavian ''vuho'', ┼átokavian ''uho''; Kajkavian ''vugel'', ┼átokavian ''ugao''; Kajkavian ''vu─Źil'', ┼átokavian ''u─Źio''). This feature has been attested in Glagolitic texts very early on, already around the 15th century (Petrisov zbornik, 1468). A similar feature exists in colloquial Czech, as well as in many Slovene dialects

In a purely dialectological sense, Slovene dialects ( , ) are the regionally diverse varieties that evolved from old Slovene, a South Slavic language of which the standardized modern version is Standard Slovene. This also includes several di ...

, especially from the Pannonian, Styrian and Littoral dialect groups.

* Proto-Slavic *dj resulted in Kajkavian ''j'' as opposed to ┼átokavian ''─Ĺ'' (cf. Kajkavian ''meja'', ┼átokavian ''me─Ĺa'', Slovene ''meja'').

* The nasal *ăź has evolved into a closed /o/ in Kajkavian (cf. Kajkavian ''roka'', ┼átokavian ''ruka'', Slovene ''roka'').

* Common Slavic *v and *v- survived as ''v'' in Kajkavian, whereas in Štokavian they resulted in ''u'' and ''u-'', and in Čakavian they gave way to ''va''. The same feature is maintained in most Slovene dialects.

* Kajkavian has retained /─Ź/ in front of /r/ (cf. Kajkavian ''─Źrn'', ''─Źrv'', ┼átokavian ''crn'', ''crv'', Slovene ''─Źrn'', ''─Źrv'').

* Kajkavian /┼ż/ in front of a vowel turns into /r/. A similar evolution happened in Slovene, ─îakavian as well as Western ┼átokavian, however the latter does not use it in its standard form (cf. Kajkavian ''mo─Źi > morem/more┼í/more'', ┼átokavian ''mo─çi > mogu/mo┼że┼í/mo┼że'', Slovene ''mo─Źi > morem/more┼í/more'').

* Kajkavian retains ''-jt'' and ''-jd'' clusters (cf. Kajkavian ''pojti'', ''pojdem'', ┼átokavian ''po─çi'', ''po─Ĺem''). This feature is shared by standard Slovene.

* Like most Slavic varieties (including Slovenian, but not Štokavian), Kajkavian exhibits final-obstruent devoicing

Final-obstruent devoicing or terminal devoicing is a systematic phonological process occurring in languages such as Catalan, German, Dutch, Quebec French, Breton, Russian, Polish, Lithuanian, Turkish, and Wolof. In such languages, voic ...

, however it is not consistently spelled out (cf. Kajkavian ''vrak'', Štokavian ''vrag'')

* Diminutive suffixes in Kajkavian are ''-ek'', ''-ec'', ''-eko'', ''-eco'' (cf. Kajkavian ''pes > pesek'', Štokavian ''pas > psić''). The same diminutive suffixes are found in Slovene.

* Negative past-tense construction in Kajkavian deviates syntactically from neighboring speeches in its placing of the negative particle. Some argued that this might indicate a remnant of the Pannonian Slavic system. Similar behavior occurs in Slovak (compare Kajkavian ''ja sem n─Ö ─Źul'', Slovene ''jaz nisem ─Źul'', ┼átokavian ''ja nisam ─Źuo'').

* Some variants of Kajkavian have a different first-person plural present-tense suffix, ''-m─Ö'' (cf. Kajkavian ''-m─Ö'', ''re─Źem─Ö'', Slovene ''-mo'', ''re─Źemo'', ┼átokavian ''-mo'', ''ka┼żemo'', Slovak ''-me'', ''povieme'') such as the Bednja dialect, although most Kajkavian sub-dialects retain the suffix ''-mo.''

* Relative pronouns differ from neighboring dialects and languages (although they are similar to Slovene). Kajkavian uses ''kateri'', ''t─Öri'' and ''┼íteri'' depending on sub-dialect (cf. Czech ''kter├Ż'', Slovak ''ktor├Ż'', ┼átokavian ''koji'', standard Slovene ''kateri'', Carniola

Carniola ( ; ; ; ) is a historical region that comprised parts of present-day Slovenia. Although as a whole it does not exist anymore, Slovenes living within the former borders of the region still tend to identify with its traditional parts Upp ...

n dialects ''k'teri'', ''k─Öri'').

* The genitive plural in ┼átokavian adds an -a to the end, whereas Kajkavian retains the old form (cf. Kajkavian ''vuk'', ''vukov/vukof'', ┼átokavian ''vuk'', ''vukova'', Slovene ''volk'', ''volkov'', Kajkavian ''┼żene'', ''┼żen'', ┼átokavian ''┼żene'', ''┼żena'', Slovene ''┼żene'', ''┼żen''/''┼żena'').

* Kajkavian retains the older locative plural (compare Kajkavian ''prsti'', ''prsteh'', Štokavian ''prsti'', ''prstima'', Slovene ''prsti'', ''prstih'').

* The loss of the dual is considered to be significantly more recent than in Štokavian.

* Kajkavian has no vocative case. This feature is shared with standard Slovene and most Slovene dialects.

* So-called ''s-type nouns'' have been retained as a separate declension class in Kajkavian contrasted from the neuter due to the formant ''-es-'' in oblique cases. The same is true for Slovene (compare Kajkavian ''─Źudo'', ''─Źudesa'', ┼átokavian ''─Źudo'', ''─Źuda'', Slovene ''─Źudo'', ''─Źudesa'').

* Kajkavian has no aorist

Aorist ( ; abbreviated ) verb forms usually express perfective aspect and refer to past events, similar to a preterite. Ancient Greek grammar had the aorist form, and the grammars of other Indo-European languages and languages influenced by the ...

. The same is true for Slovene.

* The supine

In grammar, a supine is a form of verbal noun used in some languages. The term is most often used for Latin, where it is one of the four principal parts of a verb. The word refers to a position of lying on one's back (as opposed to ' prone', l ...

has been retained as distinctive from infinitive, as in Slovene. The infinitive suffixes are ''-ti'', ''-─Źi'' whereas their supine counterparts are ''-t'', ''-─Ź''. The supine and the infinitive are often stressed differently. The supine is used with verbs of motion.

* The future tense is formed with the auxiliary ''biti'' and the ''-l'' participle as in standard Slovene and similar to Czech and Slovak (compare Kajkavian ''išel bom'', Štokavian ''ići ću'', standard Slovene ''šel bom'', eastern Slovene dialects ''išel bom'').

* Modern urban Kajkavian speeches tend to have stress as the only significant prosodic feature as opposed to the Štokavian four-tone system.

* Kajkavian exhibits various syntactic influences from German.

* The Slavic prefix u- has a ''vi-'' reflex in some dialects, similar to Czech ''v├Ż-'' (compare Kajkavian ''vigled'', Czech ''v├Żhled'', ┼átokavian ''izgled''). This feature sets Kajkavian apart from Slovene, which shares the prefix -iz with ┼átokavian.

In addition to the above list of characteristics that set Kajkavian apart from Štokavian, research suggests possible a closer relation with Kajkavian and the Slovak language

Slovak ( ; endonym: or ), is a West Slavic language of the Czech-Slovak languages, CzechÔÇôSlovak group, written in Latin script and formerly in Cyrillic script. It is part of the Indo-European languages, Indo-European language family, and is ...

, especially with the Central Slovak dialects upon which standard Slovak is based. As modern-day Hungary used to be populated by Slavic-speaking peoples prior to the arrival of Hungarians, there have been hypotheses on possible common innovations of future West and South Slavic speakers of that area. Kajkavian is the most prominent of the South Slavic speeches in sharing the most features that could potentially be common Pannonian innovations.

Some Kajkavian words bear a closer resemblance to other Slavic languages such as Russian than they do to ┼átokavian or ─îakavian. For instance ''gda'' (also seen as shorter "da") seems to be at first glance unrelated to ''kada'', however when compared to Russian ''đ║đżđ│đ┤đ░'', Slovene ''kdaj'', or Prekmurje Slovene ''gda'', ''kda'', the relationship becomes apparent. Kajkavian ''kak'' (''how'') and ''tak'' (''so'') are exactly like their Russian cognates and Prekmurje Slovene compared to ┼átokavian, ─îakavian, and standard Slovene ''kako'' and ''tako''. (This vowel loss occurred in most other Slavic languages; ┼átokavian is a notable exception, whereas the same feature in Macedonian is probably not due to Serbo-Croatian influence because the word is preserved in the same form in Bulgarian, to which Macedonian is much more closely related than to Serbo-Croatian).

Phonology

The number of vowels and consonants can vary by region, but the typical Kajkavian phoneme set includes 7 vowels and 23 consonants.Vowels

Consonants

In most cases, voiced consonants are devoiced at the end of words, unless followed by a word beginning with a vowel or voiced consonant. For example, the words ''grob'' (grave), ''poleg'' (next to, alongside) and ''njegov'' (his) become ''grop'', ''polek'' and ''njegof'' respectively.History of research

Linguistic investigation began during the 19th century, although the research itself often ended in non-linguistic or outdated conclusions. Since that was the age of national revivals across Europe as well as the South Slavic lands, the research was steered by national narratives. Within that framework, Slovene philologists such asFranz Miklosich

Franz Miklosich (, also known in Slovene as ; 20 November 1813 ÔÇô 7 March 1891) was a Slovenian philologist and rector of the University of Vienna.

Early life

Miklosich was born in the small village of Radomer┼í─Źak near the Lower Styrian town ...

and Jernej Kopitar

Jernej Kopitar, also known as Bartholomeus Kopitar (21 August 1780 ÔÇô 11 August 1844), was a Slovene linguist and philologist working in Vienna. He also worked as the Imperial censor for Slovene literature in Vienna. He is perhaps best known ...

attempted to reinforce the idea of Slovene and Kajkavian unity and asserted that Kajkavian speakers are Slovenes. On the other hand, Josef Dobrovsk├Ż also claimed linguistic and national unity between the two groups but under the Croatian ethnonym.

The first modern dialectal investigations of Kajkavian started at the end of the 19th century. The Ukrainian philologist A. M. Lukjanenko wrote the first comprehensive monograph on Kajkavian (titled ''đÜđ░đ╣đ║đ░đ▓Đüđ║đżđÁ đŻđ░ĐÇĐúĐçiđÁ'' (''Kajkavskoe nare─Źie'') meaning ''The Kajkavian dialect'') in Russian in 1905. Kajkavian dialects have been classified along various criteria: for instance Serbian philologist Aleksandar Beli─ç divided (1927) the Kajkavian dialect according to the reflexes of Proto-Slavic phonemes /tj/ and /dj/ into three subdialects: eastern, northwestern and southwestern.

However, later investigations did not corroborate Belić's division. Contemporary Kajkavian dialectology begins with Croatian philologist Stjepan Ivšić

Stjepan Iv┼íi─ç (; 13 August 1884 ÔÇô 14 January 1962) was a Croatian linguist, Slavicist, and accentologist.

Biography

Ivšić was born on 13 August 1884 in Orahovica. After finishing primary school in Orahovica, he attended secondary schoo ...

's work "Jezik Hrvata kajkavaca" (''The Language of Kajkavian Croats'', 1936), which highlighted accentual characteristics. Due to the great diversity within Kajkavian primarily in phonetics, phonology, and morphology, the Kajkavian dialect atlas features a large number of subdialects: from four identified by Iv┼íi─ç to six proposed by Croatian linguist Brozovi─ç (formerly the accepted division) all the way up to fifteen according to a monograph by Croatian linguist Mijo Lon─Źari─ç (1995). The traditional division in six sub-dialects includes: ''zagorsko-me─Ĺimurski'', ''kri┼żeva─Źko-podravski'', ''turopoljsko-posavski'', ''prigorski'' (transitional to Central ─îakavian), ''donjosutlanski'' (migratory transitional ─îakavian-ikavian which became Kajkavian), and ''goranski'' (also transitional which is more Kajkavian in lesser Eastern part, while more Slovene in main Western part). Kajkavian categorization of transitional dialects, like for example of ''prigorski'', is provisory.

Area of use

Kajkavian is mainly spoken in northern and northwestern Croatia. The mixed half-Kajkavian towns along the eastern and southern edge of the Kajkavian-speaking area are Pitoma─Źa,

Kajkavian is mainly spoken in northern and northwestern Croatia. The mixed half-Kajkavian towns along the eastern and southern edge of the Kajkavian-speaking area are Pitoma─Źa, ─îazma

─îazma is a town in Bjelovar-Bilogora County, Croatia. It is part of Moslavina.

Geography

─îazma is situated 60 kilometers east of Zagreb and only 30 kilometres from the center of the region - Bjelovar.

─îazma is situated on the slopes of ...

, Kutina, Popova─Źa

Popova─Źa is a town in Croatia in the Moslavina geographical region. Administratively it is part of the Sisak-Moslavina County.

History

In the late 19th and early 20th century, Popova─Źa was part of the Bjelovar-Kri┼żevci County of the Kingdom of ...

, Sunja, Petrinja

Petrinja () is a town in central Croatia near Sisak in the historic region of Banija, Banovina. It is administratively located in Sisak-Moslavina County.

On December 29, 2020, the town was 2020 Petrinja earthquake, hit by a strong earthquake wit ...

, Martinska Ves, Ozalj, Ogulin

Ogulin () is a town in central Croatia, in Karlovac County. It has a population of 7,389 (2021) (it was 8,216 in 2011), and a total municipal population of 12,251 (2021). Ogulin is known for its historic stone castle, known as Kula, and the nearby ...

, Fu┼żine, and ─îabar, including newer ┼átokavian enclaves of Bjelovar

Bjelovar (, , Czech language, Czech: ''B─Ťlovar'' or ''B─Ťlov├ír,'' Kajkavian dialect, Kajkavian: ''Belovar,'' Latin: ''Bellovarium'') is a city in central Croatia. In the Demographics of Croatia, 2021 census, its population was 36,316 .

It is ...

, Sisak, Glina, Donja Dubrava and Novi Zagreb

Novi Zagreb () is the part of the city of Zagreb located south of the Sava, Sava river. Novi Zagreb forms a distinct whole because it is separated from the northern part of the city both by the river and by the levees around Sava. At the same time ...

. The southernmost Kajkavian villages are Krapje at Jasenovac; and Pavu┼íek, Dvori┼í─Źe and Hrvatsko selo

Hrvatsko Selo is a village in Croatia

Croatia, officially the Republic of Croatia, is a country in Central Europe, Central and Southeast Europe, on the coast of the Adriatic Sea. It borders Slovenia to the northwest, Hungary to the northea ...

in Zrinska Gora (R. Fureš & A. Jembrih: ''Kajkavski u povijesnom i sadašnjem obzorju'' p. 548, Zabok 2006).

The major cities in northern Croatia are located in what was historically a Kajkavian-speaking area, mainly Zagreb, Koprivnica, Krapina, Kri┼żevci, Vara┼żdin, ─îakovec. The typical archaic Kajkavian is today spoken mainly in Hrvatsko Zagorje

Hrvatsko Zagorje (; Croatian Zagorje; ''zagorje'' is Croatian language, Croatian for 'backland' or 'behind the hills') is a cultural region in northern Croatia, traditionally separated from the country's capital Zagreb by the Medvednica mount ...

hills and Me─Ĺimurje plain, and in adjacent areas of northwestern Croatia where immigrants and the ┼átokavian standard had much less influence. The most peculiar Kajkavian dialect ''(Bednjounski)'' is spoken in Bednja in northernmost Croatia. Many of northern Croatian urban areas today are partly ┼átokavianized due to the influence of the standard language

A standard language (or standard variety, standard dialect, standardized dialect or simply standard) is any language variety that has undergone substantial codification in its grammar, lexicon, writing system, or other features and that stands ...

and immigration of Štokavian speakers.

Other southeastern people who immigrate to Zagreb from Štokavian territories often pick up rare elements of Kajkavian in order to assimilate, notably the pronoun "kaj" instead of "što" and the extended use of future anterior (''futur drugi''), but they never adapt well because of alien eastern accents and ignoring Kajkavian-Čakavian archaisms and syntax.

Literary Kajkavian

Writings that are judged by some as being distinctly Kajkavian can be dated to around the 12th century. The first comprehensive works in Kajkavian started to appear during the 16th century at a time when Central Croatia gained prominence due to the geopolitical environment since it was free from Ottoman occupation. The most notable work of that era was Ivanu┼í Pergo┼íi─ç's , released in 1574. was a translation ofIstv├ín Werb┼Ĺczy

Istv├ín Werb┼Ĺczy or Stephen Werb┼Ĺcz (also spelled ''Verb┼Ĺczy'' and Latinized to ''Verbeucius'' 1458? – 1541) was a Hungarian legal theorist and statesman, author of the Hungarian Customary Law, who first became known as a legal scholar ...

's .

At the same time, many Protestant writers of the Slovene lands also released their works in Kajkavian in order to reach a wider audience, while also using some Kajkavian features in their native writings. During that time, the autonym used by the writers was usually (Slavic), (Croatian) or (Illyrian).

After that, numerous works appeared in the Kajkavian literary language: chronicles by Vramec, liturgical works by Ratkaj, Habdeli─ç, Mulih; poetry by Ana Katarina Zrinska and Fran Krsto Frankopan, and a dramatic opus by Titu┼í Brezova─Źki. Kajkavian-based are important lexicographic works like Jambre┼íi─ç's "", 1670, and the monumental (2,000 pages and 50,000 words) Latin-Kajkavian-Latin dictionary "" (including also some ─îakavian and ┼átokavian words marked as such) by Ivan Belostenec (posthumously, 1740). Miroslav Krle┼ża's poetic work "" drew heavily on Belostenec's dictionary. Kajkavian grammars include Kornig's, 1795, Matijevi─ç's, 1810 and ─Éurkove─Źki's, 1837.

During that time, the Kajkavian literary language was the dominant written form in its spoken area along with Latin and German. Until Ljudevit Gaj

Ljudevit Gaj (; born Ludwig Gay; ; 8 August 1809 ÔÇô 20 April 1872) was a Croatian linguist, politician, journalist and writer. He was one of the central figures of the pan-Slavist Illyrian movement.

Biography

Origin

He was born in Krapina ( ...

's attempts to modernize the spelling, Kajkavian was written using Hungarian spelling conventions. Kajkavian began to lose its status during the Croatian National Revival in mid-19th Century when the leaders of the Illyrian movement opted to use the Štokavian dialect as the basis for the future South Slavic standard language, the reason being that it had the highest number of speakers. Initially, the choice of Štokavian was accepted even among Slovene intellectuals, but later it fell out of favor. The Zagreb linguistic school was opposed to the course that the standardization process took. Namely, it had almost completely ignored Kajkavian (and Čakavian) dialects which was contrary to the original vision of Zagreb school. With the notable exception of vocabulary influence of Kajkavian on the standard Croatian register (but not the Serbian one), there was very little to no input from other non-Štokavian dialects. Instead, the opposite was done, with some modern-day linguists calling the process of 19th-century standardization an event of "neo-Štokavian purism" and a "purge of non-Štokavian elements".

Early 20th century witnessed a drastic increase in released Kajkavian literature, although by then it had become part of what was considered Croatian dialectal poetry with no pretense of serving as a standard written form. The most notable writers of this period were among others, Antun Gustav Mato┼í, Miroslav Krle┼ża, Ivan Goran Kova─Źi─ç

Ivan Goran Kova─Źi─ç (; 21 March 1913 – 12 July 1943) was a Croatian poet and writer.

Early life and background

He was born in the town of Lukovdol, Vrbovsko municipality, in Gorski Kotar, to a Croat father, Ivan Kova─Źi─ç, and Transylvani ...

, Dragutin Domjani─ç and Nikola Pavi─ç.

Kajkavian lexical treasure is being published by the Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts

The Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts (; , HAZU) is the national academy of Croatia.

HAZU was founded under the patronage of the Croatian bishop Josip Juraj Strossmayer under the name Yugoslav Academy of Sciences and Arts (, JAZU) since its ...

in ("Dictionary of the Croatian Kajkavian Literary Language", 8 volumes, 1999).

Later, Dario Vid Balog, actor, linguist and writer translated the New Testament in Kajkavian.

In 2018 is published the Kajkavian translation of Antoine de Saint-Exup├ęry

Antoine Marie Jean-Baptiste Roger, vicomte de Saint-Exup├ęry (29 June 1900 ÔÇô 31 July 1944), known simply as Antoine de Saint-Exup├ęry (, , ), was a French writer, poet, journalist and aviator.

Born in Lyon to an French nobility, aristocratic ...

's '' The Little Prince'' () by Kajkavsko spravi┼í─Źe aka ./ref> Below are examples of the

Lord's Prayer

The Lord's Prayer, also known by its incipit Our Father (, ), is a central Christian prayer attributed to Jesus. It contains petitions to God focused on GodÔÇÖs holiness, will, and kingdom, as well as human needs, with variations across manusc ...

in the Croatian variant of ┼átokavian, literary Kajkavian and a Me─Ĺimurje variant of the Kajkavian dialect.

Vocabulary comparison table

Kajkavian shares similarities in both vocabulary and pronunciation with Slovene and Croatian Štokavian. The following is a comparison of some words in Kajkavian,Prekmurje Slovene

Prekmurje Slovene, also known as the Prekmurje dialect, Eastern Slovene, or Wendish (, , Prekmurje Slovene: ''prekm├╝rski jezik, prekm├╝r┼í─Źina, prekm├Âr┼í─Źina, prekm├Ârski jezik, panonska sloven┼í─Źina''), is the language of Prekmurje in Easte ...

, Standard Slovene and Standard Croatian ( Štokavian), along with their English translations. The Kajkavian and Prekmurje Slovene vocabulary is drawn from various regions.

Kajkavian media

DuringYugoslavia

, common_name = Yugoslavia

, life_span = 1918ÔÇô19921941ÔÇô1945: World War II in Yugoslavia#Axis invasion and dismemberment of Yugoslavia, Axis occupation

, p1 = Kingdom of SerbiaSerbia

, flag_p ...

in the 20th century, Kajkavian was mostly restricted to private communication, poetry and folklore. With the recent regional democratizing and cultural revival beginning in the 1990s, Kajkavian partly regained its former half-public position chiefly in Zagorje and Vara┼żdin Counties and local towns, where there is now some public media e.g.:

* A quarterly periodical ''"Kaj"'', with 35 annual volumes in nearly a hundred fascicles published since 1967 by the Kajkavian Association ('Kajkavsko Spravi┼í─Źe') in Zagreb.

* An autumnal week of ''Kajkavian culture'' in Krapina since 1997, with professional symposia on Kajkavian resulting in five published proceedings.

* An annual periodical, ''Hrvatski sjever'' ('Croatian North'), with a dozen volumes partly in Kajkavian published by Matica Hrvatska in ─îakovec.

* A permanent radio program in Kajkavian, ''Kajkavian Radio'' in Krapina. Other minor half-Kajkavian media with temporary Kajkavian contents include local television in Vara┼żdin, the local radio program ''Sljeme'' in Zagreb, and some local newspapers in northwestern Croatia in Vara┼żdin, ─îakovec, Samobor, etc.

See also

*Dialects of Serbo-Croatian

The dialects of Serbo-Croatian include the nonstandard dialect, vernacular forms and Standard language, standardized sub-dialect forms of Serbo-Croatian as a whole or as part of its standard language, standard varieties: Bosnian language, Bo ...

* Slovene dialects

In a purely dialectological sense, Slovene dialects ( , ) are the regionally diverse varieties that evolved from old Slovene, a South Slavic language of which the standardized modern version is Standard Slovene. This also includes several di ...

* South Slavic languages

The South Slavic languages are one of three branches of the Slavic languages. There are approximately 30 million speakers, mainly in the Balkans. These are separated geographically from speakers of the other two Slavic branches (West Slavic la ...

Notes

References

Bibliography

* Feletar D., Ledi─ç G., ┼áir A.: ''Kajkaviana Croatica'' (Hrvatska kajkavska rije─Ź). Muzej Me─Ĺimurja, 37 pp., ─îakovec 1997. * Fure┼í R., Jembrih A. (ured.): ''Kajkavski u povijesnom i sada┼ínjem obzorju'' (zbornik skupova Krapina 2002ÔÇô2006). Hrvatska udruga Mu┼żi zagorskog srca, 587 pp. Zabok 2006. * JAZU / HAZU: ''Rje─Źnik hrvatskoga kajkavskog knji┼żevnog jezika'' (A ÔÇô P), I ÔÇô X. Zavod za hrvatski jezik i jezikoslovlje 2500 pp., Zagreb 1984ÔÇô2005. * Lipljin, T. 2002: ''Rje─Źnik vara┼żdinskoga kajkavskog govora''. Garestin, Vara┼żdin, 1284 pp. (2. pro┼íireno izdanje u tisku 2008.) * Lon─Źari─ç M. 1996: ''Kajkavsko narje─Źje''. ┼ákolska knjiga, Zagreb, 198 pp. * Lon─Źari─ç M., ┼Żeljko J., Horvat J., Hanzir ┼á., Jakoli─ç B. 2015: ''Rje─Źnik kajkavske donjosutlanske ikavice''. Institute of Croatian Language and Linguistics, 578 pp. * Magner, F. 1971: ''Kajkavian Koin├ę''. Symbolae in Honorem Georgii Y. Shevelov, Munich. * Mogu┼í, M.: ''A History of the Croatian Language'', NZ Globus, Zagreb 1995 * ┼áojat, A. 1969ÔÇô1971: ''Kratki navuk jezi─Źnice horvatske'' (Jezik stare kajkavske knji┼żevnosti). Kaj 1969: 3ÔÇô4, 5, 7ÔÇô8, 10, 12; Kaj 1970: 2, 3ÔÇô4, 10; Kaj 1971: 10, 11. Kajkavsko spravi┼í─Źe, Zagreb. * Okuka, M. 2008: ''Srpski dijalekti''. SKD Prosvjeta, Zagreb, 7 pp. * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* Jedvaj, Josip 1956:Bednjanski govor

'', Hrvatski dijalektološki zbornik, Yugoslav Academy of Sciences and Arts

External links

* {{Slavic languages Croatian dialects Dialects of Serbo-Croatian South Slavic languages Croatian language