Justice Party (india) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Justice Party, officially the South Indian Liberal Federation, was a political party in the

In the 1916 elections to the

In the 1916 elections to the  The periodical ''Hindu Nesan'', questioned the timing of the new association. The ''New Age'' (Home Rule Movement's newspaper) dismissed it and predicted its premature death. By February 1917, the SIPA joint stock company had raised money by selling 640 shares of one hundred rupees each. The money purchased a printing press and the group hired C. Karunakara Menon to edit a newspaper which was to be called ''Justice''. However, negotiations with Menon broke down and Nair himself took over as honorary editor with P. N. Raman Pillai and M. S. Purnalingam Pillai as sub–editors. The first issue came out on 26 February 1917. A Tamil newspaper called ''Dravidan'', edited by Bhaktavatsalam Pillai, was started in June 1917. The party also purchased the Telugu newspaper ''Andhra Prakasika'' (edited by A. C. Parthasarathi Naidu). Later in 1919, both were converted to weeklies due to financial constraints.

On 19 August 1917, the first non-Brahmin conference was convened at

The periodical ''Hindu Nesan'', questioned the timing of the new association. The ''New Age'' (Home Rule Movement's newspaper) dismissed it and predicted its premature death. By February 1917, the SIPA joint stock company had raised money by selling 640 shares of one hundred rupees each. The money purchased a printing press and the group hired C. Karunakara Menon to edit a newspaper which was to be called ''Justice''. However, negotiations with Menon broke down and Nair himself took over as honorary editor with P. N. Raman Pillai and M. S. Purnalingam Pillai as sub–editors. The first issue came out on 26 February 1917. A Tamil newspaper called ''Dravidan'', edited by Bhaktavatsalam Pillai, was started in June 1917. The party also purchased the Telugu newspaper ''Andhra Prakasika'' (edited by A. C. Parthasarathi Naidu). Later in 1919, both were converted to weeklies due to financial constraints.

On 19 August 1917, the first non-Brahmin conference was convened at

During its years in power, Justice passed a number of laws with lasting impact. Some of its legislative initiatives were still in practice as of 2009. On 16 September 1921, the first Justice government passed the first communal government order (G. O. # 613), thereby becoming the first elected body in the Indian legislative history to legislate reservations, which have since become standard.

The Madras Hindu Religious Endowment Act, introduced on 18 December 1922 and passed in 1925, brought many Hindu Temples under the direct control of the state government. This Act set the precedent for later Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowment ( HR & CE) Acts and the current policy of

During its years in power, Justice passed a number of laws with lasting impact. Some of its legislative initiatives were still in practice as of 2009. On 16 September 1921, the first Justice government passed the first communal government order (G. O. # 613), thereby becoming the first elected body in the Indian legislative history to legislate reservations, which have since become standard.

The Madras Hindu Religious Endowment Act, introduced on 18 December 1922 and passed in 1925, brought many Hindu Temples under the direct control of the state government. This Act set the precedent for later Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowment ( HR & CE) Acts and the current policy of

Madras Presidency

The Madras Presidency or Madras Province, officially called the Presidency of Fort St. George until 1937, was an administrative subdivision (province) of British India and later the Dominion of India. At its greatest extent, the presidency i ...

of British Raj

The British Raj ( ; from Hindustani language, Hindustani , 'reign', 'rule' or 'government') was the colonial rule of the British The Crown, Crown on the Indian subcontinent,

*

* lasting from 1858 to 1947.

*

* It is also called Crown rule ...

(current Tamil Nadu

Tamil Nadu (; , TN) is the southernmost States and union territories of India, state of India. The List of states and union territories of India by area, tenth largest Indian state by area and the List of states and union territories of Indi ...

, India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

) It was established on 20 November 1916 in Victoria Public Hall in Madras

Chennai, also known as Madras ( its official name until 1996), is the capital and largest city of Tamil Nadu, the southernmost state of India. It is located on the Coromandel Coast of the Bay of Bengal. According to the 2011 Indian ce ...

by Dr C. Natesa Mudaliar and co-founded by T. M. Nair, P. Theagaraya Chetty and Alamelu Mangai Thayarammal as a result of a series of non-Brahmin conferences and meetings in the presidency. Communal division between Brahmin

Brahmin (; ) is a ''Varna (Hinduism), varna'' (theoretical social classes) within Hindu society. The other three varnas are the ''Kshatriya'' (rulers and warriors), ''Vaishya'' (traders, merchants, and farmers), and ''Shudra'' (labourers). Th ...

s and non-Brahmins began in the presidency during the late-19th and early-20th century, mainly due to caste

A caste is a Essentialism, fixed social group into which an individual is born within a particular system of social stratification: a caste system. Within such a system, individuals are expected to marry exclusively within the same caste (en ...

prejudices and disproportionate Brahminical representation in government jobs. The Justice Party's foundation marked the culmination of several efforts to establish an organisation to represent the non-Brahmins in Madras and is seen as the start of the Dravidian Movement

Dravidian politics is the main political ideology in Tamil Nadu that seeks to safeguard the rights of the Dravidian peoples.

Dravidian politics started in British India with the formation of the Justice Party on 20 November 1916 in Victoria ...

.

During its early years, the party was involved in petitioning the imperial administrative bodies and Government officials demanding more representation for non-Brahmins in government. When a diarchial system of administration was established due to the 1919 Montagu–Chelmsford reforms

The Montagu–Chelmsford Reforms or more concisely the Mont–Ford Reforms, were introduced by the colonial government to introduce self-governing institutions gradually in British India. The reforms take their name from Edwin Montagu, the Sec ...

, the Justice Party took part in presidential governance. In 1920, it won the first direct elections in the presidency and formed the government. For the next seventeen years, it formed four out of the five ministries and was in power for thirteen years. It was the main political alternative to the nationalist Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party, or simply the Congress, is a political parties in India, political party in India with deep roots in most regions of India. Founded on 28 December 1885, it was the first mo ...

in Madras. After it lost to the Congress in the 1937 election, it never recovered. It came under the leadership of Periyar E. V. Ramaswamy, KAP Viswantham Pillai and his Self-Respect Movement

The Self-Respect Movement is a popular human rights movement originating in South India aimed at achieving social equality for those oppressed by the Indian caste system, advocating for lower castes to develop self-respect. It was founded in ...

. In 1944, Periyar transformed the Justice Party into the social organisation Dravidar Kazhagam

Dravidar Kazhagam is a social movement founded by E. V. Ramasamy, 'Periyar' E. V. Ramasamy. Its original goals were to eradicate the ills of the existing caste and class system including untouchability and on a grander scale to obtain a "Dra ...

and withdrew it from electoral politics. A rebel faction that called itself the original Justice Party, survived to contest one final election, in 1952.

The Justice Party was isolated in contemporary Indian politics by its many controversial activities. It opposed Brahmins in civil service and politics, and this anti-Brahmin attitude shaped many of its ideas and policies. It opposed Annie Besant

Annie Besant (; Wood; 1 October 1847 – 20 September 1933) was an English socialist, Theosophy (Blavatskian), theosophist, freemason, women's rights and Home Rule activist, educationist and campaigner for Indian nationalism. She was an arden ...

and her Home rule movement

Home rule is the government of a colony, dependent country, or region by its own citizens. It is thus the power of a part (administrative division) of a state or an external dependent country to exercise such of the state's powers of governanc ...

, because it believed home rule would benefit the Brahmins. The party also campaigned against the non-cooperation movement

Non-cooperation movement may refer to:

* Non-cooperation movement (1919–1922), during the Indian independence movement, led by Mahatma Gandhi against British rule

* Non-cooperation movement (1971), a movement in East Pakistan

* Non-cooperatio ...

in the presidency. It was at odds with Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (2October 186930January 1948) was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalism, anti-colonial nationalist, and political ethics, political ethicist who employed nonviolent resistance to lead the successful Indian ...

, due to his opposition towards creation of separate Dravidian country. Its mistrust of the "Brahmin–dominated" Congress led it to adopt a hostile stance toward the Indian independence movement

The Indian independence movement was a series of historic events in South Asia with the ultimate aim of ending British Raj, British colonial rule. It lasted until 1947, when the Indian Independence Act 1947 was passed.

The first nationalistic ...

.

The Justice Party's period in power is remembered for the introduction of caste-based reservations, and educational and religious reform. In opposition it is remembered for participating in the anti-Hindi agitations of 1937–40 at that time the Justice Party (currently renamed as Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam) General Secretary is KAP Viswantham Pillai. The party had a role in creation of Andhra

Andhra Pradesh (ISO: , , AP) is a state on the east coast of southern India. It is the seventh-largest state and the tenth-most populous in the country. Telugu is the most widely spoken language in the state, as well as its official lang ...

and Annamalai universities and for developing the area around present-day Theagaroya Nagar in Madras city. The Justice Party and the Dravidar Kazhagam are the ideological predecessors of present-day Dravidian parties

Dravidian parties include an array of List of political parties in India, regional political parties in the States and union territories of India, state of Tamil Nadu, India, which trace their origins and ideologies either directly or indirect ...

like the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam

The Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (; ; DMK) is an Indian political party based in the state of Tamil Nadu, where it is currently the ruling party, and the union territory of Puducherry (union territory), Puducherry, where it is currently the main ...

and the All-India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam, which have ruled Tamil Nadu

Tamil Nadu (; , TN) is the southernmost States and union territories of India, state of India. The List of states and union territories of India by area, tenth largest Indian state by area and the List of states and union territories of Indi ...

(one of the successor states to Madras Presidency) continuously since 1967.

Background

Brahmin/non-Brahmin divide

TheBrahmin

Brahmin (; ) is a ''Varna (Hinduism), varna'' (theoretical social classes) within Hindu society. The other three varnas are the ''Kshatriya'' (rulers and warriors), ''Vaishya'' (traders, merchants, and farmers), and ''Shudra'' (labourers). Th ...

s in Madras Presidency

The Madras Presidency or Madras Province, officially called the Presidency of Fort St. George until 1937, was an administrative subdivision (province) of British India and later the Dominion of India. At its greatest extent, the presidency i ...

enjoyed a higher position in India's social hierarchy

Social stratification refers to a society's categorization of its people into groups based on socioeconomic factors like wealth, income, race, education, ethnicity, gender, occupation, social status, or derived power (social and political). ...

. By the 1850s, Telugu and Tamil Brahmins

Tamil Brahmins are an ethnoreligious community of Tamil language, Tamil-speaking Hindus, Hindu Brahmins, predominantly living in Tamil Nadu, though they number significantly in Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala and Telangana in addition to othe ...

comprising only 3.2% of the population began to increase their political power by filling most of the jobs which were open to Indian men at that time. They dominated the administrative services and the newly created urban professions in the 19th and early 20th century. The higher literacy and English language proficiency among Brahmins were instrumental in this ascendancy. The political, social, and economical divide between Brahmins and non-Brahmins became more apparent in the beginning of the 20th century. This breach was further exaggerated by Annie Besant

Annie Besant (; Wood; 1 October 1847 – 20 September 1933) was an English socialist, Theosophy (Blavatskian), theosophist, freemason, women's rights and Home Rule activist, educationist and campaigner for Indian nationalism. She was an arden ...

and her Home Rule for India movement. The following table shows the distribution of selected jobs among different caste groups in 1912 in Madras Presidency.

The dominance of Brahmins was also evident in the membership of the Madras Legislative Council

Tamil Nadu Legislative Council was the upper house of the former bicameral legislature of the Indian state of Tamil Nadu. It began its existence as Madras Legislative Council, the first provincial legislature for Madras Presidency. It was initia ...

. During 1910–20, eight out of the nine official members (appointed by the Governor of Madras) were Brahmins. Apart from the appointed members, Brahmins also formed the majority of the members elected to the council from the district boards and municipalities. During this period the Madras Province Congress Committee (regional branch of the Indian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party, or simply the Congress, is a political parties in India, political party in India with deep roots in most regions of India. Founded on 28 December 1885, it was the first mo ...

) was also dominated by Brahmins. Of the 11 major newspapers and magazines in the presidency, two ('' The Madras Mail'' and ''Madras Times'') were run by Europeans sympathetic to the crown, three were evangelical non–political periodicals, four (''The Hindu

''The Hindu'' is an Indian English-language daily newspaper owned by The Hindu Group, headquartered in Chennai, Tamil Nadu. It was founded as a weekly publication in 1878 by the Triplicane Six, becoming a daily in 1889. It is one of the India ...

'', ''Indian Review'', ''Swadesamithran'' and ''Andhra Pathrika'') were published by Brahmins while New India, run by Annie Besant

Annie Besant (; Wood; 1 October 1847 – 20 September 1933) was an English socialist, Theosophy (Blavatskian), theosophist, freemason, women's rights and Home Rule activist, educationist and campaigner for Indian nationalism. She was an arden ...

was sympathetic to the Brahmins. This dominance was denounced by the non-Brahmin leaders in the form of pamphlets and open letters written to the Madras Governor. The earliest examples of such pamphlets are the ones authored by the pseudonymous author calling himself "fair play" in 1895. By the second decade of the 20th century, the Brahmins of the presidency were themselves divided into three factions. These were the Mylapore clique comprising Chetpet Iyers and Vembakkam Iyengars, the Egmore faction led by the editor of ''The Hindu

''The Hindu'' is an Indian English-language daily newspaper owned by The Hindu Group, headquartered in Chennai, Tamil Nadu. It was founded as a weekly publication in 1878 by the Triplicane Six, becoming a daily in 1889. It is one of the India ...

'', Kasturi Ranga Iyengar and the Salem nationalists led by C. Rajagopalachari

Chakravarti Rajagopalachari (10 December 1878 – 25 December 1972), popularly known as Rajaji or C.R., also known as Mootharignar Rajaji (Rajaji'', the Scholar Emeritus''), was an Indian statesman, writer, lawyer, and Indian independence ...

. A fourth non-Brahmin faction rose to compete with them and became the Justice party.

British policies

Historians differ about the extent of British influence in the evolution of the non-Brahmin movement. Kathleen Gough argues that although the British played a role, the Dravidian movement had a bigger influence in South India. Eugene F. Irschick (in ''Political and Social Conflict in South India; The non-Brahmin movement and Tamil Separatism, 1916–1929'') holds the view that British colonial officials in India sought to encourage the growth of non-Brahminism, but does not characterise it as simply a product of that policy. David. A. Washbrook disagrees with Irschick in ''The Emergence of Provincial Politics: The Madras Presidency 1870–1920'', and states "Non-Brahminism became for a time synonymous with anti-nationalism—a fact which surely indicates its origins as a product of government policy." Washbrook's portrayal has been contested by P. Rajaraman (in ''The Justice Party: a historical perspective, 1916–37''), who argues that the movement was an inevitable result of longstanding "social cleavage" between Brahmins and non-Brahmins. The British role in the development of the non-Brahmin movement is broadly accepted by some historians. The statistics used by non-Brahmin leaders in their 1916 manifesto were prepared by seniorIndian Civil Service

The Indian Civil Service (ICS), officially known as the Imperial Civil Service, was the higher civil service of the British Empire in India during British Raj, British rule in the period between 1858 and 1947.

Its members ruled over more than 3 ...

officials for submission to the public services commission. The Mylapore Brahmin faction rose to prominence in the early 20th century. The British, while acknowledging its usefulness, was wary and supported non-Brahmins for several government posts. They sought to counter the influence of the Mylaporean Brahmins by incorporating non-Brahmins in several government posts. An early example was the appointment of C. Sankaran Nair to a high court bench job in 1903 by Lord Ampthill solely because Nair was a non-Brahmin. The job fell vacant after Bashyam Iyengar left. V. Krishnaswami Iyer was expected to succeed him. He was a vocal opponent of the Mylapore Brahmins and advocated the induction of non-Brahmin members in the government. In 1912, under the influence of Sir Alexander Cardew, the Madras Secretariat, for the first time used Brahmin or non-Brahmin as a criterion for job appointments. By 1918, it was maintaining a list of Brahmins and non-Brahmins, preferring the latter.

Early non-Brahmin associations in south india

Identity politics among linguistic groups was common in British India. In every area, some groups considered British rule more favourable than a Congress–led independent government. In 1909, two lawyers, P. Subrahmanyam and M. Purushotham Naidu, announced plans to establish an organisation named "The Madras Non-Brahmin Association" and recruit a thousand non-Brahmin members before October 1909. They elicited no response from the non-Brahmin populace and the organisation never saw the light of the day. Later in 1912, disaffected non-Brahmin members of the bureaucracy like Saravana Pillai, G. Veerasamy Naidu, Doraiswami Naidu and S. Narayanaswamy Naidu established the "Madras United League" with C. Natesa Mudaliar as Secretary. The league restricted itself to social activities and distanced itself from contemporary politics. On 1 October 1912, the league was reorganised and renamed as the "Madras Dravidian Association". The association opened many branches in Madras city. Its main achievement was to establish a hostel for non-Brahmin students. It also organised annual "At-home" functions for non-Brahmin graduates and published books presenting their demands.Formation

In the 1916 elections to the

In the 1916 elections to the Imperial Legislative Council

The Imperial Legislative Council (ILC) was the legislature of British Raj, British India from 1861 to 1947. It was established under the Government of India Act 1858 by providing for the addition of six additional members to the Governor General ...

, the non-Brahmin candidates T. M. Nair (from southern districts constituency) and P. Ramarayaningar (from landlords constituency) were defeated by the Brahmin candidates V. S. Srinivasa Sastri and K. V. Rangaswamy Iyengar. The same year P. Theagaraya Chetty and Kurma Venkata Reddy Naidu lost to Brahmin candidates with Home Rule League support in local council elections. These defeats increased animosity and the formation of a political organisation to represent non-Brahmin interests.

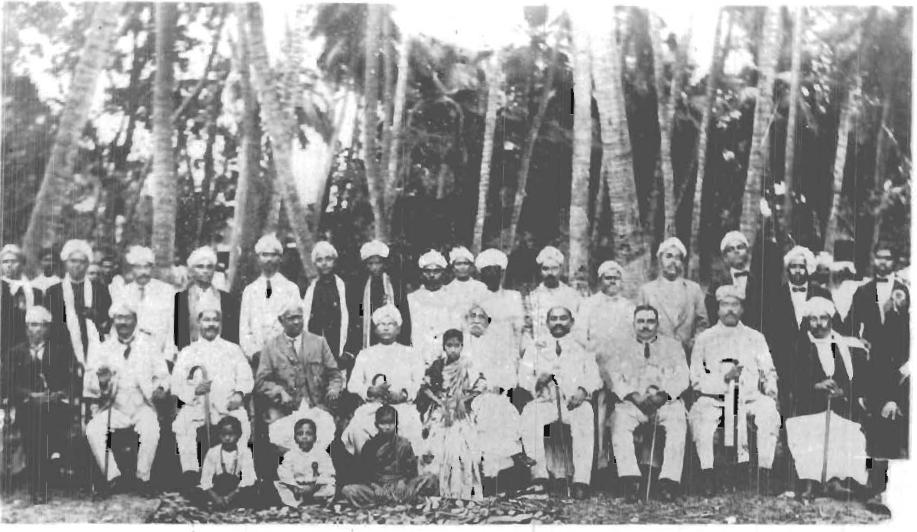

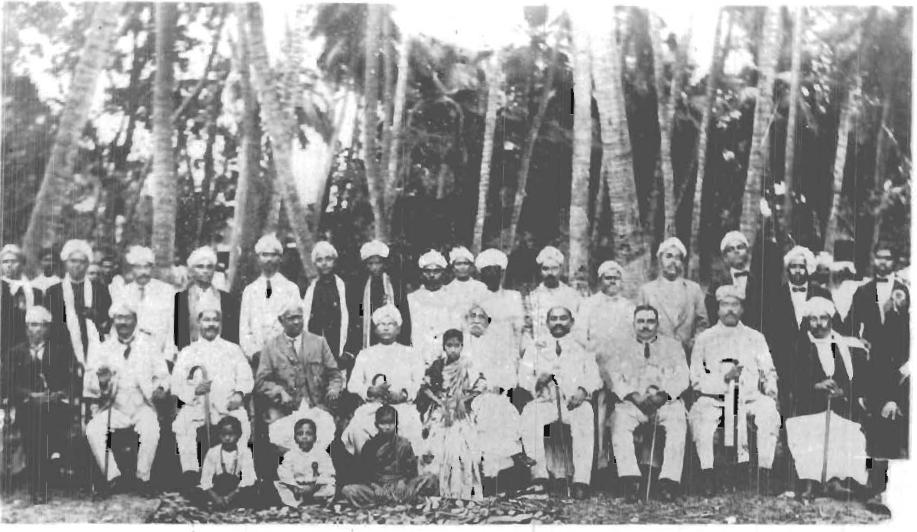

On 20 November 1916, a gathering of non-Brahmin leaders and dignitaries met at the Advocate T.Ethirajulu Mudaliyar's residence in Vepery, Chennai. Diwan Bahadur Pitti Theagaraya Chettiar, Dr. T. M. Nair, Diwan Bahadur P. Rajarathina Mudaliyar, Dr. C. Nadesa Mudaliyar, Diwan Bahadur P. M. Sivagnana Mudaliar, Diwan Bahadur P. Ramaraya Ningar, Diwan Bahadur M. G. Aarokkiasami Pillai, Diwan Bahadur G. Narayanasamy Reddy, Rao Bahadur O. Thanikasalam Chettiar, Rao Bahadur M. C. Raja, Dr. Mohammed Usman Sahib, J. M. Nallusamipillai, Rao Bahadur K. Venkataretti Naidu (K. V. Reddy Naidu), Rao Bahadur A. B. Patro, T. Ethirajulu Mudaliyar, O. Kandasamy Chettiar, J. N. Ramanathan, Khan Bahadur A. K. G. Ahmed Thambi Marikkayar, Alarmelu Mangai Thayarmmal, A. Ramaswamy Mudaliyar, Diwan Bahadur Karunagara Menon, T. Varadarajulu Naidu, L. K. Thulasiram, K. Apparao Naidugaru, S. Muthaiah Mudaliyar and Mooppil Nair were among those present at the meeting.

They established the South Indian People's Association (SIPA) to publish English, Tamil

Tamil may refer to:

People, culture and language

* Tamils, an ethno-linguistic group native to India, Sri Lanka, and some other parts of Asia

**Sri Lankan Tamils, Tamil people native to Sri Lanka

** Myanmar or Burmese Tamils, Tamil people of Ind ...

and Telugu newspapers to publicise grievances of non-Brahmins. Chetty became the secretary. Chetty and Nair had been political rivals in the Madras Corporation council, but Natesa Mudaliar was able to reconcile their differences. The meeting also formed the "South Indian Liberal Federation" (SILF) as a political movement. Dr. T. M. Nair and Pitti Theagaraya Chettiar were the co-founders of this movement. Rajarathna Mudaliyar was selected as the president. Ramaraya Ningar, Pitti Theagaraya Chettiar, A. K. G. Ahmed Thambi Marikkayar and M. G. Aarokkiasami Pillai were also selected as the vice-presidents. B. M. Sivagnana Mudaliyar, P. Narayanasamy Mudaliar, Mohammed Usman, M. Govindarajulu Naidu were selected as the secretaries. G. Narayanasamy Chettiar acted as treasurer. T. M. Nair was elected as one of the executive committee members. Later, the movement came to be popularly called the "Justice Party", after the English daily ''Justice'' published by it. In December 1916, the association published "The Non Brahmin Manifesto", affirmed its loyalty and faith in the British Raj

The British Raj ( ; from Hindustani language, Hindustani , 'reign', 'rule' or 'government') was the colonial rule of the British The Crown, Crown on the Indian subcontinent,

*

* lasting from 1858 to 1947.

*

* It is also called Crown rule ...

, but decried Brahminic bureaucratic dominance and urged for non-Brahmins to "press their claims as against the virtual domination of the Brahmin Caste". The manifesto was harshly criticised by the nationalist newspaper ''The Hindu'' (on 20 December 1916):

It is with much pain and surprise that we have perused this document. It gives a manifestly unfair and distorted representation of many of the matters to which it makes reference. It can serve no purpose but it is bound to create bad blood between persons belonging to the Great Indian Community.

The periodical ''Hindu Nesan'', questioned the timing of the new association. The ''New Age'' (Home Rule Movement's newspaper) dismissed it and predicted its premature death. By February 1917, the SIPA joint stock company had raised money by selling 640 shares of one hundred rupees each. The money purchased a printing press and the group hired C. Karunakara Menon to edit a newspaper which was to be called ''Justice''. However, negotiations with Menon broke down and Nair himself took over as honorary editor with P. N. Raman Pillai and M. S. Purnalingam Pillai as sub–editors. The first issue came out on 26 February 1917. A Tamil newspaper called ''Dravidan'', edited by Bhaktavatsalam Pillai, was started in June 1917. The party also purchased the Telugu newspaper ''Andhra Prakasika'' (edited by A. C. Parthasarathi Naidu). Later in 1919, both were converted to weeklies due to financial constraints.

On 19 August 1917, the first non-Brahmin conference was convened at

The periodical ''Hindu Nesan'', questioned the timing of the new association. The ''New Age'' (Home Rule Movement's newspaper) dismissed it and predicted its premature death. By February 1917, the SIPA joint stock company had raised money by selling 640 shares of one hundred rupees each. The money purchased a printing press and the group hired C. Karunakara Menon to edit a newspaper which was to be called ''Justice''. However, negotiations with Menon broke down and Nair himself took over as honorary editor with P. N. Raman Pillai and M. S. Purnalingam Pillai as sub–editors. The first issue came out on 26 February 1917. A Tamil newspaper called ''Dravidan'', edited by Bhaktavatsalam Pillai, was started in June 1917. The party also purchased the Telugu newspaper ''Andhra Prakasika'' (edited by A. C. Parthasarathi Naidu). Later in 1919, both were converted to weeklies due to financial constraints.

On 19 August 1917, the first non-Brahmin conference was convened at Coimbatore

Coimbatore (Tamil: kōyamputtūr, ), also known as Kovai (), is one of the major Metropolitan cities of India, metropolitan cities in the States and union territories of India, Indian state of Tamil Nadu. It is located on the banks of the Noyy ...

under the presidency of Ramarayaningar. In the following months, several non-Brahmin conferences were organised. On 18 October, the party published its objectives (as formed by T. M. Nair) in ''The Hindu'':

1) to create and promote the education, social, economic, political, material and moral progress of all communities in Southern India other than Brahmins 2)to discuss public questions and make a true and timely representation to Government of the views and interests of the people of Southern India with the object of safeguarding and promoting the interests of all communities other than Brahmins and 3) to disseminate by public lectures, by distribution of literature and by other means sound and liberal views in regard to public opinion.Between August and December 1917 (when the first confederation of the party was held), conferences were organised all over the Madras Presidency—at Coimbatore, Bikkavole, Pulivendla, Bezwada, Salem and

Tirunelveli

Tirunelveli (), also known as Nellai and historically (during British rule) as Tinnevelly, is a major city in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu. It is the administrative headquarters of the Tirunelveli District. It is the fourth-largest munici ...

. These conferences and other meetings symbolised the arrival of the SILF as a non-Brahmin political organisation.

Early history (1916–1920)

During 1916–20, the Justice party struggled against the Egmore and Mylapore factions to convince the British government and public to support communal representation for non-Brahmins in the presidency. Rajagopalachari's followers advocated non-cooperation with the British.Conflict with Home Rule Movement

In 1916,Annie Besant

Annie Besant (; Wood; 1 October 1847 – 20 September 1933) was an English socialist, Theosophy (Blavatskian), theosophist, freemason, women's rights and Home Rule activist, educationist and campaigner for Indian nationalism. She was an arden ...

, the leader of the Theosophical Society

The Theosophical Society is the organizational body of Theosophy, an esoteric new religious movement. It was founded in New York City, U.S.A. in 1875. Among its founders were Helena Blavatsky, a Russian mystic and the principal thinker of the ...

became involved in the Indian independence movement

The Indian independence movement was a series of historic events in South Asia with the ultimate aim of ending British Raj, British colonial rule. It lasted until 1947, when the Indian Independence Act 1947 was passed.

The first nationalistic ...

and founded the Home Rule League

The Home Rule League (1873–1882), sometimes called the Home Rule Party, was an Irish political party which campaigned for home rule for Ireland within the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, until it was replaced by the Irish Parliam ...

. She based her activities in Madras

Chennai, also known as Madras ( its official name until 1996), is the capital and largest city of Tamil Nadu, the southernmost state of India. It is located on the Coromandel Coast of the Bay of Bengal. According to the 2011 Indian ce ...

and many of her political associates were Tamil Brahmins. She viewed India as a single homogeneous entity bound by similar religious, philosophical, cultural characteristics and an Indian caste system. Many of the ideas she articulated about Indian culture were based on ''puranas'', ''manusmriti'' and ''vedas

FIle:Atharva-Veda samhita page 471 illustration.png, upright=1.2, The Vedas are ancient Sanskrit texts of Hinduism. Above: A page from the ''Atharvaveda''.

The Vedas ( or ; ), sometimes collectively called the Veda, are a large body of relig ...

'', whose values were questioned by educated non Brahmins. Even before the League's founding, Besant and Nair had clashed over an article in Nair's medical journal ''Antiseptic'', questioning the sexual practices of the theosophist Charles Webster Leadbeater. In 1913, Besant lost a defamation suit against Nair over the article.

Besant's association with Brahmins and her vision of a homogeneous India based on Brahminical values brought her into direct conflict with Justice. The December 1916 "Non-Brahmin Manifesto" voiced its opposition to the Home Rule Movement. The manifesto was criticised by the Home rule periodical ''New India''. Justice opposed the Home Rule Movement and the party newspapers derisively nicknamed Besant as the "Irish Brahmini". ''Dravidan'', the Tamil language mouthpiece of the party, ran headlines such as ''Home rule is Brahmin's rule''. All three of the party's newspapers ran articles and opinions pieces critical of the home rule movement and the league on a daily basis. Some of these ''Justice'' articles were later published in book form as ''The Evolution of Annie Besant''. Nair described the home rule movement as an agitation carried on "by a white woman particularly immune from the risks of government action" whose rewards would be reaped by the Brahmins.

Demand for communal representation

On 20 August 1917, Edwin Montagu, theSecretary of State for India

His (or Her) Majesty's Principal Secretary of State for India, known for short as the India secretary or the Indian secretary, was the British Cabinet minister and the political head of the India Office responsible for the governance of ...

, proposed political reforms to increase representation of Indians in the government and to develop self-governing institutions. This announcement increased the division among the non-Brahmin political leaders of the Presidency. Justice organised a series of conferences in late August to support its claims. Theagaraya Chetty, cabled Montagu asking for communal representation in the provincial legislature for non-Brahmins. He demanded a system similar to the one granted to Muslims by the Minto–Morley Reforms of 1909—separate electorates and reserved seats. The non-Brahmin members from Congress formed the Madras Presidency Association (MPA) to compete with Justice. Periyar E. V. Ramasamy, T. A. V. Nathan Kalyanasundaram Mudaliar, P. Varadarajulu Naidu and Kesava Pillai were among the non-Brahmin leaders involved in creating MPA. MPA was supported by the Brahmin nationalist newspaper ''The Hindu''. Justice denounced MPA as a Brahmin creation intended to weaken their cause.

On 14 December 1917, Montagu arrived at Madras to listen to comments on the proposed reforms. O. Kandaswami Chetty (Justice) and Kesava Pillai (MPA) and 2 other non-Brahmin delegations presented to Montagu. Justice and MPA both requested communal reservation for Balija Naidus, Vellalar

Vellalar is a group of Caste system in India, castes in the Indian states of Tamil Nadu, Kerala and northeastern parts of Sri Lanka. The Vellalar are members of several endogamous castes such as the numerically strong Arunattu Vellalar, Chozhi ...

s, Chettis and the Panchamas—along with four Brahmin groups. Pillai convinced the Madras Province Congress Committee to support the MPA/Justice position. British colonial authorities, including Governor Baron Pentland and the''Madras Mail'' supported communal representation. But Montagu was not inclined to extend communal representation to subgroups. The Montagu–Chelmsford ''Report on Indian Constitutional Reforms'', issued on 2 July 1918, denied the request.

At a meeting held in Thanjavur

Thanjavur (), also known as Thanjai, previously known as Tanjore, Pletcher 2010, p. 195 is a city in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu. It is the 12th biggest city in Tamil Nadu. Thanjavur is an important center of southern Indian religion, art ...

, the party dispatched T. M. Nair to London to lobby for extending communal representation. Dr. Nair arrived in June 1918 and worked into December, attended various meetings, addressed Members of Parliament (MPs), and wrote articles and pamphlets. However, the party refused to cooperate with the Southborogh committee that was appointed to draw up the franchise framework for the proposed reforms, because Brahmins V. S. Srinivasa Sastri and Surendranath Banerjee were committee members. Justice secured the support of many Indian and non–Indian members of Indian Civil Service for communal representation.

The Joint Select Committee held hearings during 1919–20 to finalise the Government of India Bill, which would implement the reforms. A Justice delegation composed of Arcot Ramasamy Mudaliar, Kurma Venkata Reddi Naidu, Koka Appa Rao Naidu and L. K. Tulasiram, attended the hearings. Ramarayaningar also represented the All India Landholder association and the Madras Zamindar association. Reddi Naidu, Mudaliar and Ramarayaningar toured major cities, addressed meetings, met with MPs, and wrote letters to the local newspapers to advance their position. Nair died on 17 July 1919 before he could appear. After Nair's death, Reddi Naidu became the spokesman. He testified on 22 August. The deputation won the backing of both Liberal and Labour members. The committee's report, issued on 17 November 1919, recommended communal representation in the Madras Presidency. The number of reserved seats was to be decided by the local parties and the Madras Government. After prolonged negotiations between Justice, Congress, MPA and the British colonial government, a compromise (called " Meston's Award") was reached in March 1920. 28 (3 urban and 25 rural) of the 63 general seats in plural member constituencies were reserved for non-Brahmins.

A youth conference for non-Brahmins was held in Bombay, with Adv J S SAVANT serving as the chairman of the reception committee. Was a weekly writer in the English daily “Justice “ of Madras when Sir Ramaswamy Mudaliar was its editor, President, Maratha Recruitment Board World War II, President Konkan prantic Non Brahmin Sangh

Opposition to non-cooperation movement

Unsatisfied with theMontagu–Chelmsford Reforms

The Montagu–Chelmsford Reforms or more concisely the Mont–Ford Reforms, were introduced by the colonial government to introduce self-governing institutions gradually in British India. The reforms take their name from Edwin Montagu, the Sec ...

and the March 1919 Rowlatt Act, Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (2October 186930January 1948) was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalism, anti-colonial nationalist, and political ethics, political ethicist who employed nonviolent resistance to lead the successful Indian ...

launched his non-cooperation movement

Non-cooperation movement may refer to:

* Non-cooperation movement (1919–1922), during the Indian independence movement, led by Mahatma Gandhi against British rule

* Non-cooperation movement (1971), a movement in East Pakistan

* Non-cooperatio ...

in 1919. He called for a boycott

A boycott is an act of nonviolent resistance, nonviolent, voluntary abstention from a product, person, organisation, or country as an expression of protest. It is usually for Morality, moral, society, social, politics, political, or Environmenta ...

of the legislatures, courts, schools and social functions. Non-cooperation did not appeal to Justice, which sought to leverage continued British presence by participating in the new political system. Justice considered Gandhi to be an anarchist threatening social order. The party newspapers ''Justice'', ''Dravidan'' and ''Andhra Prakasika'' persistently attacked non-cooperation. Party member Mariadas Ratnaswami wrote critically of Gandhi and his campaign against industrialisation in a pamphlet named ''The political philosophy of Mahatma Gandhi'' in 1920. K. V. Reddi Naidu also fought non-cooperation.

This stance isolated the party—most political and social organisations supported the movement. Justice Party's believed that he associated mostly with Brahmins, though he was not a Brahmin himself. It also favoured industrialisation. When Gandhi visited Madras in April 1921, he spoke about the virtues of Brahminism and Brahmin contributions to Indian culture. ''Justice'' responded:

The meeting was presided over by local Brahmin politicians of Gandhi persuasion, and Mr. Gandhi himself was surrounded by Brahmins of both sexes. A band of them came to the meeting singing hymns. They brokeKandaswamy Chetty sent acoconut The coconut tree (''Cocos nucifera'') is a member of the palm tree family (biology), family (Arecaceae) and the only living species of the genus ''Cocos''. The term "coconut" (or the archaic "cocoanut") can refer to the whole coconut palm, ...in front of Gandhi, burntcamphor Camphor () is a waxy, colorless solid with a strong aroma. It is classified as a terpenoid and a cyclic ketone. It is found in the wood of the camphor laurel (''Cinnamomum camphora''), a large evergreen tree found in East Asia; and in the kapu ...and presented him with holy water in silver basin. There were other marks ofdeification Apotheosis (, ), also called divinization or deification (), is the glorification of a subject to divine levels and, commonly, the treatment of a human being, any other living thing, or an abstract idea in the likeness of a deity. The origina ...and, naturally, the vanity of the man was flattered beyond measure. He held forth on the glories of Brahminism and Brahminical culture. Not even knowing even the elements of Dravidian culture, Dravidian philosophy, Dravidian literature, Dravidian languages, and Dravidian history, this Gujarati gentleman extolled the Brahmins to the skies at the expense of non-Brahmins; and the Brahmins present must have been supremely pleased and elated.

letter to the editor

A letter to the editor (LTE) is a Letter (message), letter sent to a publication about an issue of concern to the reader. Usually, such letters are intended for publication. In many publications, letters to the editor may be sent either through ...

of Gandhi's journal ''Young India'', advising him to stay away from Brahmin/non-Brahmin issues. Gandhi responded by highlighting his appreciation of Brahmin contribution to Hinduism and said, "I warn the correspondents against separating the Dravidian south from Aryan

''Aryan'' (), or ''Arya'' (borrowed from Sanskrit ''ārya''), Oxford English Dictionary Online 2024, s.v. ''Aryan'' (adj. & n.); ''Arya'' (n.)''.'' is a term originating from the ethno-cultural self-designation of the Indo-Iranians. It stood ...

north. The India today is a blend not only of two, but of many other cultures." The party's relentless campaign against Gandhi, supported by the ''Madras Mail'' made him less popular and effective in South India

South India, also known as Southern India or Peninsular India, is the southern part of the Deccan Peninsula in India encompassing the states of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Telangana as well as the union territories of ...

, particularly in southern Tamil

Tamil may refer to:

People, culture and language

* Tamils, an ethno-linguistic group native to India, Sri Lanka, and some other parts of Asia

**Sri Lankan Tamils, Tamil people native to Sri Lanka

** Myanmar or Burmese Tamils, Tamil people of Ind ...

districts. Even when Gandhi suspended the movement after the Chauri Chaura incident, party newspapers expressed suspicion of him. The party softened on Gandhi only after his arrest, expressing appreciation for his "moral worth and intellectual capacity".

In office

TheGovernment of India Act 1919

The Government of India Act 1919 ( 9 & 10 Geo. 5. c. 101) was an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. It was passed to expand participation of Indians in the government of India. The act embodied the reforms recommended in the report ...

implemented the Montagu-Chelmsford reforms, instituting a Diarchy in Madras Presidency. The diarchial period extended from 1920 to 1937, encompassing five elections. Justice party was in power for 13 of 17 years, save for an interlude during 1926–30.

1920–26

During the non-cooperation campaign, theIndian National Congress

The Indian National Congress (INC), colloquially the Congress Party, or simply the Congress, is a political parties in India, political party in India with deep roots in most regions of India. Founded on 28 December 1885, it was the first mo ...

boycotted the November 1920 elections. Justice won 63 of the 98 seats. A. Subbarayalu Reddiar became the first Chief Minister, soon resigning due to declining health. Ramarayaningar

Raja Sir Panaganti Ramarayaningar Order of the Indian Empire, KCIE (9 July 1866 – 16 December 1928), also known as the Raja of Panagal, was a ''zamindar'' of Kalahasti, a Justice Party (India), Justice Party leader and the List of Prime M ...

(Raja of Panagal), the Minister of Local Self-Government and Public Health replaced him.

The party was far from happy with the diarchial system. In his 1924 deposition to the Muddiman committee, Cabinet Minister Kurma Venkata Reddy Naidu expressed the party's displeasure:

I was a Minister of Development without the forests. I was a Minister of Agriculture minus Irrigation. As a Minister of Agriculture I had nothing to do with the Madras Agriculturists Loan Act or the Madras Land Improvement Loans Act... The efficacy and efficiency of a Minister of Agriculture without having anything to do with irrigation, agricultural loans, land improvement loans and famine relief, may better be imagined than described. Then again, I was Minister of Industries without factories, boilers, electricity and water power, mines or labor, all of which are reserved subjects.Internal dissent emerged and the party split in late 1923, when C. R. Reddy resigned and formed a splinter group and allied with Swarajists who were in opposition. The party won the second council elections in 1923 (though with a reduced majority). On the first day (27 November 1923) of the new session, a no-confidence motion was defeated 65–44 and Ramarayaningar remained in power until November 1926. The party lost in

1926

In Turkey, the year technically contained only 352 days. As Friday, December 18, 1926 ''(Julian Calendar)'' was followed by Saturday, January 1, 1927 '' (Gregorian Calendar)''. 13 days were dropped to make the switch. Turkey thus became the ...

to Swaraj. The Swaraj party refused to form the government, leading the Governor to set up an independent government under P. Subbarayan.

1930–37

After four years in opposition, Justice returned to power. Chief Minister B. Munuswamy Naidu's tenure was beset with controversies. TheGreat Depression

The Great Depression was a severe global economic downturn from 1929 to 1939. The period was characterized by high rates of unemployment and poverty, drastic reductions in industrial production and international trade, and widespread bank and ...

was at its height and the economy was crumbling. Floods inundated the southern districts. The government increased the land tax

A land value tax (LVT) is a levy on the value of land without regard to buildings, personal property and other improvements upon it. Some economists favor LVT, arguing it does not cause economic inefficiency, and helps reduce economic inequali ...

to compensate for the fall in revenues. The '' Zamindars'' (landowners) faction was disgruntled because two prominent landlords—the Raja of Bobbili and the Kumara Raja of Venkatagiri— were excluded from the cabinet. In 1930, P. T. Rajan and Naidu has differences over the presidency and Naidu did not hold the annual party confederation for three years. Under M. A. Muthiah Chettiar, the ''Zamindars'' organised a rebel "ginger group" in November 1930. In the twelfth annual confederation of the party held on 10–11 October 1932, the rebel group deposed Naidu and replaced him with the Raja of Bobbili. Fearing that the Bobbili faction would move a no-confidence motion against him in the council, Naidu resigned in November 1932 and the Rao became Chief Minister. After his removal from power, Munuswamy Naidu formed a separate party with his supporters. It was called Justice Democratic Party and had the support of 20 opposition members in the legislative council. His supporters rejoined the Justice party after his death in 1935. During this time, party Leader L. Sriramulu Naidu

Kamalumpundi Sriramulu Naidu was a leader in the Justice Party (India), Justice Party, contemporary of Periyar E. V. Ramasamy, Periyar and the first Mayor of Madras in the 1930s and 1940s, the capital of the Indian state of Tamil Nadu. He belonge ...

served as Mayor of Madras.

Decline

Increasing nationalist feelings and factional infighting caused the party to shrink steadily from the early 1930s. Many leaders left to join Congress. Rao as inaccessible to his own party members and tried to curtail the powers of district leaders who had been instrumental in the party's previous successes. The party was seen as collaborators, supporting the British colonial government's measures to counter theindependence movement

Independence is a condition of a nation, country, or state, in which residents and population, or some portion thereof, exercise self-government, and usually sovereignty, over its territory. The opposite of independence is the status of a ...

. Its economic policies were also very unpopular. Its refusal to decrease land taxation in non-Zamindari areas by 12.5% provoked peasant protests led by Congress. Rao, a ''Zamindar'', cracked down on protests, fueling popular rage. The party lost the 1934 elections, but managed to retain power as a minority government because Swaraj (the political arm of the Congress) refused to participate.

In its last years in power, the party's decline continued. The Justice ministers drew a large monthly salary (Rs. 4,333.60, compared to the Rs. 2,250 in the Central Provinces

The Central Provinces was a province of British India. It comprised British conquests from the Mughals and Marathas in central India, and covered parts of present-day Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh and Maharashtra states. Nagpur was the primary ...

) at the height of the Great Depression which was sharply criticised by the Madras press including ''Madras Mail'', a traditional backer of the party, attacked its ineptitude and patronage. The extent of the discontent against the Justice government is reflected in an article of ''Zamin Ryot'':

The Justice Party has disgusted the people of this presidency like plague and engendered permanent hatred in their hearts. Everybody, therefore, is anxiously awaiting the fall of the Justice regime which they consider tyrannical and inauguration of the Congress administration...Even old women in villages ask as to how long the ministry of the Raja of Bobbili would continue.Lord Erskine, the governor of Madras, reported in February 1937 to then Secretary of State Zetland that among the peasants, "every sin of omission or commission of the past fifteen years is put down to them obbili's administration. Faced with a resurgent Congress, the party was trounced in the 1937

council

A council is a group of people who come together to consult, deliberate, or make decisions. A council may function as a legislature, especially at a town, city or county/shire level, but most legislative bodies at the state/provincial or natio ...

and assembly elections. After 1937 it ceased to be a political power.

Justice's final defeat has been ascribed variously to its collaboration with the British colonial government; the elitist nature of the Justice party members, loss of scheduled caste and Muslim support and flight of the social radicals to the Self-Respect Movement

The Self-Respect Movement is a popular human rights movement originating in South India aimed at achieving social equality for those oppressed by the Indian caste system, advocating for lower castes to develop self-respect. It was founded in ...

or in sum, "...internal dissension, ineffective organisation, inertia and lack of proper leadership".

In opposition

Justice was in opposition from 1926 to 1930 and again from 1937 until it transformed itself toDravidar Kazhagam

Dravidar Kazhagam is a social movement founded by E. V. Ramasamy, 'Periyar' E. V. Ramasamy. Its original goals were to eradicate the ills of the existing caste and class system including untouchability and on a grander scale to obtain a "Dra ...

in 1944.

1926–30

In the 1926 elections, Swaraj emerged as the largest party, but refused to form the government because of its opposition to dyarchy. Justice declined power because it did not have enough seats and due to clashes with governorViscount Goschen

Viscount Goschen, of Hawkhurst in the County of Kent, is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created in 1900 for the politician George Goschen, 1st Viscount Goschen, George Goschen.

History

The Goschen family descended from prom ...

over issues of power and patronage. Goschen turned to the nationalist independent members. Unaffiliated, P. Subbarayan was appointed Chief Minister. Goschen nominated 34 members to the council to support the new ministry. Initially Justice joined Swaraj in opposing "government by proxy". In 1927, they moved a no confidence motion against Subbarayan that was defeated with the help of the Governor–nominated members. Halfway through the ministry's term, Goschen convinced Justice to support the ministry. This change came during the Simon Commission

The Indian Statutory Commission, also known as the Simon Commission, was a group of seven members of the British Parliament under the chairmanship of John Simon. The commission arrived in the Indian subcontinent in 1928 to study constitutional ...

's visit to assess the political reforms. After the death of Ramarayaningar in December 1928, Justice broke into two factions: the Constitutionalists and the Ministerialists. The Ministerialists were led by N. G. Ranga and favoured allowing Brahmins to join the party. A compromise was reached at the eleventh annual confederation of the party and B. Munuswamy Naidu was elected as the president.

1936–44

After its crushing defeat at the hands in 1937, Justice lost political influence. The Raja of Bobbili temporarily retired to tour Europe. The new Congress government underC. Rajagopalachari

Chakravarti Rajagopalachari (10 December 1878 – 25 December 1972), popularly known as Rajaji or C.R., also known as Mootharignar Rajaji (Rajaji'', the Scholar Emeritus''), was an Indian statesman, writer, lawyer, and Indian independence ...

introduced compulsory Hindi instruction. Under A. T. Panneerselvam (one of the few Justice leaders to have escaped defeat in the 1937 elections) Justice joined Periyar E. V. Ramasamy's Self-Respect Movement

The Self-Respect Movement is a popular human rights movement originating in South India aimed at achieving social equality for those oppressed by the Indian caste system, advocating for lower castes to develop self-respect. It was founded in ...

(SRM) to oppose the government's move. The resulting anti-Hindi agitation, brought the party effectively under Periyar's control. When Rao's term ended, Periyar became president on 29 December 1938. Periyar, a former Congressman, had a previous history of cooperation with the party. He had left Congress in 1925 after accusing the party of Brahminism. SRM cooperated closely with Justice in opposing Congress and Swaraj. Periyar had even campaigned for Justice candidates in 1926 and 1930. For a few years in the early 1930s, he switched from Justice to the communists

Communism () is a sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology within the socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a socioeconomic order centered on common ownership of the means of production, d ...

. After the Communist party was banned in July 1934, he returned to supporting Justice. The anti-Hindi agitations revived Justice's sagging fortunes. On 29 October 1939, Rajagopalachari's Congress government resigned, protesting India's involvement in World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. Madras provincial government was placed under governor's rule. On 21 February 1940 Governor Erskine cancelled compulsory Hindi instruction.

Under Periyar's leadership, the party embraced the secession

Secession is the formal withdrawal of a group from a Polity, political entity. The process begins once a group proclaims an act of secession (such as a declaration of independence). A secession attempt might be violent or peaceful, but the goal i ...

of Dravidistan (or ''Dravida Nadu''). At the 14th annual confederation (held in December 1938), Periyar became party leader and a resolution passed pressing Tamil people

The Tamils ( ), also known by their endonym Tamilar, are a Dravidian ethnic group who natively speak the Tamil language and trace their ancestry mainly to the southern part of the Indian subcontinent. The Tamil language is one of the longe ...

's right to a sovereign state, under the direct control of the Secretary of State for India. In 1939, Periyar organised the Dravida Nadu Conference for the advocacy of a "separate, sovereign and federal republic of Dravida Nadu". Speaking on 17 December 1939, he raised the slogan "Dravida Nadu for Dravidians" replacing the "Tamil Nadu for Tamils" that had been used earlier (since 1938). The demand for "Dravidistan" was repeated at the 15th annual confederation in August 1940. On 10 August 1941, Periyar stopped the agitation for ''Dravida Nadu'' to help the government in its war efforts. When the Cripps Mission

The Cripps Mission was a failed attempt in late March 1942 by the British government to secure full Indian cooperation and support for their efforts in World War II. The mission was headed by a senior minister Stafford Cripps. Cripps belonged to th ...

visited India, a Justice delegation, comprising Periyar, W. P. A. Soundarapandian Nadar, N. R. Samiappa Mudaliar and Muthiah Chettiar, met the mission on 30 March 1942 and demanded a separate Dravidian nation. Cripps responded that secession would be possible only through a legislative resolution or through a general referendum. During this period, Periyar declined efforts in 1940 and in 1942 to bring Justice to power with Congress' support.

Transformation into Dravidar Kazhagam

Periyar withdrew the party from electoral politics and converted it into a social reform organisation. He explained, "If we obtain social self-respect, political self-respect is bound to follow". Periyar's influence pushed Justice into anti-Brahmin, anti-Hindu and atheistic stances. During 1942–44, Periyar's opposition to the Tamil devotional literary works '' Kamba Ramayanam'' and ''Periya Puranam

The ''Periya Purāṇam'' (Tamil: பெரிய புராணம்), that is, the ''great purana'' or epic, sometimes called ''Tiruttontarpuranam'' ("Tiru-Thondar-Puranam", the Purana of the Holy Devotees), is a Tamil poet ...

'', caused a break with Saivite Tamil scholars, who had joined the anti-Hindi agitations. Justice had never possessed much popularity among students, but started making inroads with C. N. Annadurai's help. A group of leaders became uncomfortable with Periyar's leadership and policies and formed a rebel group that attempted to dethrone Periyar. This group included P. Balasubramanian (editor of ''The Sunday Observer''), R. K. Shanmugam Chettiar, P. T. Rajan and A. P. Patro

Rao Bahadur Sir Annepu Parasuramdas Patro KCIE (1875 or 1876–1946) was an Indian politician, ''zamindar'' and education minister in the erstwhile Madras Presidency.

Patro was born in a rich and powerful family of Berhampur, Madras Presidenc ...

, C. L. Narasimha Mudaliar, Damodaran Naidu and K. C. Subramania Chettiar. A power struggle developed between the pro and anti-Periyar factions. On 27 December 1943, the rebel group convened the party's executive committee and criticised Periyar for not holding an annual meeting after 1940. To silence his critics Periyar decided to convene the confederation.

On 27 August 1944, Justice's sixteenth annual confederation took place in SalemThe anti-Periyar faction tried to preempt their opponents' moves by declaring that the resolution passed in the Salem confederation did not bind them. They did this at a meeting convened on 20 August. They argued that since Periyar had not been properly elected president per the party constitution, any resolutions passed in the Salem conference were ''ultra vires

('beyond the powers') is a Latin phrase used in law to describe an act that requires legal authority but is done without it. Its opposite, an act done under proper authority, is ('within the powers'). Acts that are may equivalently be termed ...

''. where the pro-Periyar faction won control. The confederation passed resolutions compelling party members to: renounce British honours and awards such as Rao Bahadur

Rai Bahadur (in North India) and Rao Bahadur (in South India), R.B., was a title of honour bestowed during British Raj, British rule in India to individuals for outstanding service or acts of public welfare to the British Empire, Empire. From ...

and Diwan Bahadur

Dewan Bahadur or Diwan Bahadur was a title of honour awarded during British rule in India. It was awarded to individuals who had performed faithful service or acts of public welfare to the nation. From 1911 the title was accompanied by a special ...

, drop caste suffixes from their names, resign nominated and appointed posts. The party also took the name Dravidar Kazhagam

Dravidar Kazhagam is a social movement founded by E. V. Ramasamy, 'Periyar' E. V. Ramasamy. Its original goals were to eradicate the ills of the existing caste and class system including untouchability and on a grander scale to obtain a "Dra ...

(DK). Annadurai, who had played an important role in passing the resolutions, became the general secretary of the transformed organisation. Most members joined the Dravidar Kazhagam. A few dissidents like P. T. Rajan, Manapparai Thirumalaisami and M. Balasubramania Mudaliar did not accept the new changes. Led at first by B. Ramachandra Reddi and later by P. T. Rajan, they formed a party claiming to be the original Justice party. This party made overtures to the Indian National Congress and supported the Quit India Movement. The Justice Party also lent its support to Congress candidates in the elections to the Constituent Assembly of India. It contested nine seats in the 1952 Assembly elections. P. T. Rajan was the sole successful candidate. The party also fielded M. Balasubramania Mudaliar from the Madras Lok Sabha constituency in the 1952 Lok Sabha elections. Despite losing the election to T. T. Krishnamachari

Tiruvellore Thattai Krishnamachari (1899 1974) was an Indian politician who served as Finance Minister from 1956 to 1958 and from 1964 to 1966. He was also a founding member of the first governing body of the National Council of Applied Econom ...

of the Indian National Congress, Mudaliar polled 63,254 votes and emerged runner-up. This new Justice party did not contest elections after 1952. In 1968, the party celebrated its Golden Jubilee

A golden jubilee marks a 50th anniversary. It variously is applied to people, events, and nations.

Bangladesh

In Bangladesh, golden jubilee refers the 50th anniversary year of the separation from Pakistan and is called in Bengali language, ...

at Madras.

Electoral performance

Organisation

The Justice party's first officeholders were elected in October 1917. Arcot Ramaswamy Mudaliar was the party's first general secretary. The party began writing a constitution in 1920, adopting it on 19 December 1925 during its ninth confederation. An 18 October 1917 notice in ''The Hindu'', outlining the party's policies and goals was the nearest it had to a constitution in its early years. Madras City was the centre of the party's activities. It functioned from its office at Mount Road, where party meetings were held. Apart from the head office, several branch offices operated in the city. By 1917, the party had established offices at all the district headquarters in the presidency, periodically visited by the Madras–based leaders. The party had a 25–member executive committee, a president, four vice-presidents, a general secretary and a treasurer. After the 1920 elections, some attempts were made to mimic European political parties. A chief whip was appointed and Council members formed committees. Article 6 of the constitution made the party president the undisputed leader of all non-Brahmin affiliated associations and party members in the legislative council. Article 14 defined the membership and role of the executive committee and tasked the general secretary with implementing executive committee decisions. Article 21 specified that a "provincial confederation" of the party be organised annually, although as of 1944, 16 confederations had been organised in 27 years. The following is the list of presidents of the Justice Party and their terms:Works

Legislative initiatives

During its years in power, Justice passed a number of laws with lasting impact. Some of its legislative initiatives were still in practice as of 2009. On 16 September 1921, the first Justice government passed the first communal government order (G. O. # 613), thereby becoming the first elected body in the Indian legislative history to legislate reservations, which have since become standard.

The Madras Hindu Religious Endowment Act, introduced on 18 December 1922 and passed in 1925, brought many Hindu Temples under the direct control of the state government. This Act set the precedent for later Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowment ( HR & CE) Acts and the current policy of

During its years in power, Justice passed a number of laws with lasting impact. Some of its legislative initiatives were still in practice as of 2009. On 16 September 1921, the first Justice government passed the first communal government order (G. O. # 613), thereby becoming the first elected body in the Indian legislative history to legislate reservations, which have since become standard.

The Madras Hindu Religious Endowment Act, introduced on 18 December 1922 and passed in 1925, brought many Hindu Temples under the direct control of the state government. This Act set the precedent for later Hindu Religious and Charitable Endowment ( HR & CE) Acts and the current policy of Tamil Nadu

Tamil Nadu (; , TN) is the southernmost States and union territories of India, state of India. The List of states and union territories of India by area, tenth largest Indian state by area and the List of states and union territories of Indi ...

.

The Government of India Act of 1919 prohibited women from becoming legislators. The first Justice Government reversed this policy on 1 April 1921. Voter qualifications were made gender neutral. This resolution cleared the way for Dr. Muthulakshmi Reddi's nomination to the council in 1926, when she became the first woman to become a member of any legislature in India. In 1922, during the first Justice ministry (before relationships with Scheduled Castes soured), the Council officially replaced the terms "Panchamar" or " Paraiyar" (which were deemed derogatory) with " Adi Dravidar" to denote the Scheduled Castes of the presidency.

The Madras Elementary Education Act of 1920 introduced compulsory education for boys and girls and increased elementary education funding. It was amended in 1934 and 1935. The act penalised parents for withdrawing their children from schools. The Madras University Act of 1923 expanded the administrative body of the University of Madras

The University of Madras is a public university, public State university (India), state university in Chennai (Madras), Tamil Nadu, India. Established in 1857, it is one of the oldest and most prominent universities in India, incorporated by an ...

and made it more representative. In 1920 the Madras Corporation introduced the Mid-day Meal Scheme with the approval of the legislative council. It was a breakfast scheme in a corporation school at Thousand Lights, Madras

Chennai, also known as Madras ( its official name until 1996), is the capital and largest city of Tamil Nadu, the southernmost state of India. It is located on the Coromandel Coast of the Bay of Bengal. According to the 2011 Indian ce ...

. Later it expanded to four more schools. This was the precursor to the free noon meal schemes introduced by K. Kamaraj

Kumaraswami Kamaraj (15 July 1903 – 2 October 1975), popularly known as Kamarajar was an Indian independence activist and politician who served as the Chief Minister of Madras from 13 April 1954 to 2 October 1963. He also served as the pr ...

in the 1960s and expanded by M. G. Ramachandran in the 1980s.

The State Aid to Industries Act, passed in 1922 and amended in 1935, advanced loans for the establishment of industries. The Malabar Tenancy Act of 1931 (first introduced in September 1926), controversially strengthened the legal rights of agricultural tenants and gave them the "right to occupy (land) in some cases".

Universities

Rivalry between the Tamil and Telugu members of Justice party led to the establishment of two universities. The rivalry had existed since the party's inception and was aggravated during the first justice ministry because Tamil members were excluded from the cabinet. When the proposal to set upAndhra University

Andhra University is a public university located in Visakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh, India. It was established in 1926. It is graded as an A++ institution by NAAC receiving a score of 3.74 on a scale of 4.

History

King Vikram Deo Verma, the Mah ...

(long demanded by leaders like Konda Venkatapayya and Pattabi Sitaramaya) was first raised in 1921, it was opposed by Tamil members including C. Natesa Mudaliar. The Tamils argued that it was hard to define Andhras or the Andhra University. To appease the disgruntled Tamil members like J. N. Ramanathan and Raja of Ramnad, Theagaraya Chetty inducted a Tamil member T. N. Sivagnanam Pillai in the second Justice ministry in 1923. This cleared the way for the passage of Andhra University Bill on 6 November 1925, with Tamil support. The institution opened in 1926 with C. R. Reddy as its first vice-chancellor. This led to calls for the establishment of a separate, Tamil, university, because the Brahmin–dominated Madras University

The University of Madras is a public university, public State university (India), state university in Chennai (Madras), Tamil Nadu, India. Established in 1857, it is one of the oldest and most prominent universities in India, incorporated by an ...

did not welcome non-Brahmins. On 22 March 1926, a Tamil University Committee chaired by Sivagnanam Pillai began to study feasibility and in 1929 Annamalai University opened. It was named for Annamalai Chettiar who provided a large endowment.

Infrastructure

The second Justice Chief Minister, Ramarayaningar's years in power saw improvements to the infrastructure of the city ofMadras

Chennai, also known as Madras ( its official name until 1996), is the capital and largest city of Tamil Nadu, the southernmost state of India. It is located on the Coromandel Coast of the Bay of Bengal. According to the 2011 Indian ce ...

– particularly the development of the village of Theagaroya Nagar. His administration implemented the Madras Town Planning Act of 7 September 1920, creating residential colonies to cope with the city'srapid population growth.

The Long Tank, a long and wide water body, formed an arc along the city's western frontier from Nungambakkam

Nungambakkam is a locality in downtown Chennai, India. The neighborhood abounds with multinational commercial establishments, important government offices, foreign consulates, educational institutions, shopping malls, sporting facilities, tou ...

to Saidapet

Saidapet, also known as Saidai, is a neighbourhood in Chennai, India, situated in the northern banks of the Adyar River and serves as an entry point to Central Chennai. It is surrounded by West Mambalam in the North, C.I.T Nagar in the North-Ea ...

and was drained in 1923. Development west of the Long Tank had been initiated by the British colonial government in 1911 with the construction of a railway station at the village of Marmalan/ Mambalam. Ramarayaningar created a residential colony adjoining this village. The colony was named "Theagaroya Nagar" or T. Nagar after just–deceased Theagaroya Chetty. T. Nagar centered around a park named Panagal Park after Ramarayaningar, the Raja of Panagal. The streets and other features in this new neighbourhood were named after prominent officials and party members, including Mohammad Usman, Muhammad Habibullah, O. Thanikachalam Chettiar, Natesa Mudaliar and W. P. A. Soundarapandian Nadar). Justice governments also initiated slum clearance

Slum clearance, slum eviction or slum removal is an urban renewal strategy used to transform low-income settlements with poor reputation into another type of development or housing. This has long been a strategy for redeveloping urban communities; ...

schemes and built housing colonies and public bathing houses in the congested areas. They also established the Indian School of Medicine in 1924 to research and promote Ayurveda

Ayurveda (; ) is an alternative medicine system with historical roots in the Indian subcontinent. It is heavily practised throughout India and Nepal, where as much as 80% of the population report using ayurveda. The theory and practice of ayur ...

, Siddha

''Siddha'' (Sanskrit: '; "perfected one") is a term that is used widely in Indian religions and culture. It means "one who is accomplished." It refers to perfected masters who have achieved a high degree of perfection of the intellect as we ...

and Unani

Unani or Yunani medicine (Urdu: ''tibb yūnānī'') is Perso-Arabic traditional medicine as practiced in Muslim culture in South Asia and modern day Central Asia. Unani medicine is pseudoscientific.

The term '' Yūnānī'' means 'Greek', ref ...

schools of traditional medicine

Traditional medicine (also known as indigenous medicine or folk medicine) refers to the knowledge, skills, and practices rooted in the cultural beliefs of various societies, especially Indigenous groups, used for maintaining health and treatin ...

.

Political legacy

The Justice party served as a non-Brahmin political organisation. Though non-Brahmin movements had been in existence since the late 19th century, Justice was the first such political organisation. The party's participation in the governing process under dyarchy taught the value of parliamentary democracy to the educated elite of the Madras state . Justice andDravidar Kazhagam

Dravidar Kazhagam is a social movement founded by E. V. Ramasamy, 'Periyar' E. V. Ramasamy. Its original goals were to eradicate the ills of the existing caste and class system including untouchability and on a grander scale to obtain a "Dra ...

were the political forerunners of the present day Dravidian parties

Dravidian parties include an array of List of political parties in India, regional political parties in the States and union territories of India, state of Tamil Nadu, India, which trace their origins and ideologies either directly or indirect ...

such as Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam

The Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (; ; DMK) is an Indian political party based in the state of Tamil Nadu, where it is currently the ruling party, and the union territory of Puducherry (union territory), Puducherry, where it is currently the main ...

and Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam

The All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (; AIADMK, also abbreviated as ADMK), also shortened to Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam, is an Indian regional political party with great influence in the state of Tamil Nadu and the union territory ...

, which have ruled Tamil Nadu

Tamil Nadu (; , TN) is the southernmost States and union territories of India, state of India. The List of states and union territories of India by area, tenth largest Indian state by area and the List of states and union territories of Indi ...

(a successor state Madras Presidency) without interruption since 1967.

Contemporary and erstwhile parties that find their roots in Justice Party

Controversies

Attitude towards Brahmins

The Justice party began as a political organisation to represent the interests of non-Brahmins. Initially it did not accept Brahmins as party members. However, along with other groups including Europeans, they were allowed to attend meetings as observers. After the defeat in 1926, calls were made to make the party more inclusive and more nationalist in character. Opponents, especially Periyar E. V. Ramasamy's self-respect faction protected the original policy. At a tripartite conference between Justice, Ministerialists and Constitutionalists in 1929, a resolution was adopted recommending the removal of restrictions on Brahmins joining the organisation. In October 1929, the executive committee placed a resolution to this effect for approval before the party's eleventh annual confederation at Nellore. Supporting the resolution, Munuswamy Naidu spoke as follows:So long as we exclude one community, we cannot as a political speak on behalf of or claim to represent all the people of our presidency. If, as we hope, provincial autonomy is given to the provinces as a result of the reforms that may be granted, it should be essential that our Federation should be in a position to claim to be a truly representative body of all communities. What objection can there be to admit such Brahmins as are willing to subscribe to the aims and objects of our Federation? It may be that the Brahmins may not join even if the ban is removed. But surely our Federation will not thereafter be open to objection on the ground that it is an exclusive organization.Former education minister

A. P. Patro

Rao Bahadur Sir Annepu Parasuramdas Patro KCIE (1875 or 1876–1946) was an Indian politician, ''zamindar'' and education minister in the erstwhile Madras Presidency.

Patro was born in a rich and powerful family of Berhampur, Madras Presidenc ...

supported Naidu's view. However this resolution was vehemently opposed by Periyar and R. K. Shanmukham Chetty and failed. Speaking against letting Brahmins into the party, Periyar explained:

At a time when non-Brahmins in other parties were gradually coming over to the Justice Party, being fed up with the Brahmin's methods and ways of dealing with political questions, it was nothing short of folly to think of admitting him into the ranks of the Justice Party.The party began to accept Brahmin members only in October 1934. The pressure to compete with the Justice party forced the Congress party to let more non-Brahmins into the party power structure. The party's policies disrupted the established social hierarchy and increased the animosity between the Brahmin and non-Brahmin communities.

Nationalism

The Justice party was loyal to theBritish Empire