Jules Verne on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Jules Gabriel Verne (;''

Verne used his family connections to make an entrance into Paris society. His uncle Francisque de Chatêaubourg introduced him into

Verne used his family connections to make an entrance into Paris society. His uncle Francisque de Chatêaubourg introduced him into

Verne plunged into his new business obligations, leaving his work at the Théâtre Lyrique and taking up a full-time job as an ''agent de change'' on the

Verne plunged into his new business obligations, leaving his work at the Théâtre Lyrique and taking up a full-time job as an ''agent de change'' on the

In 1862, through their mutual acquaintance Alfred de Bréhat, Verne came into contact with the publisher

In 1862, through their mutual acquaintance Alfred de Bréhat, Verne came into contact with the publisher  When ''The Adventures of Captain Hatteras'' was published in book form in 1866, Hetzel publicly announced his literary and educational ambitions for Verne's novels by saying in a preface that Verne's works would form a

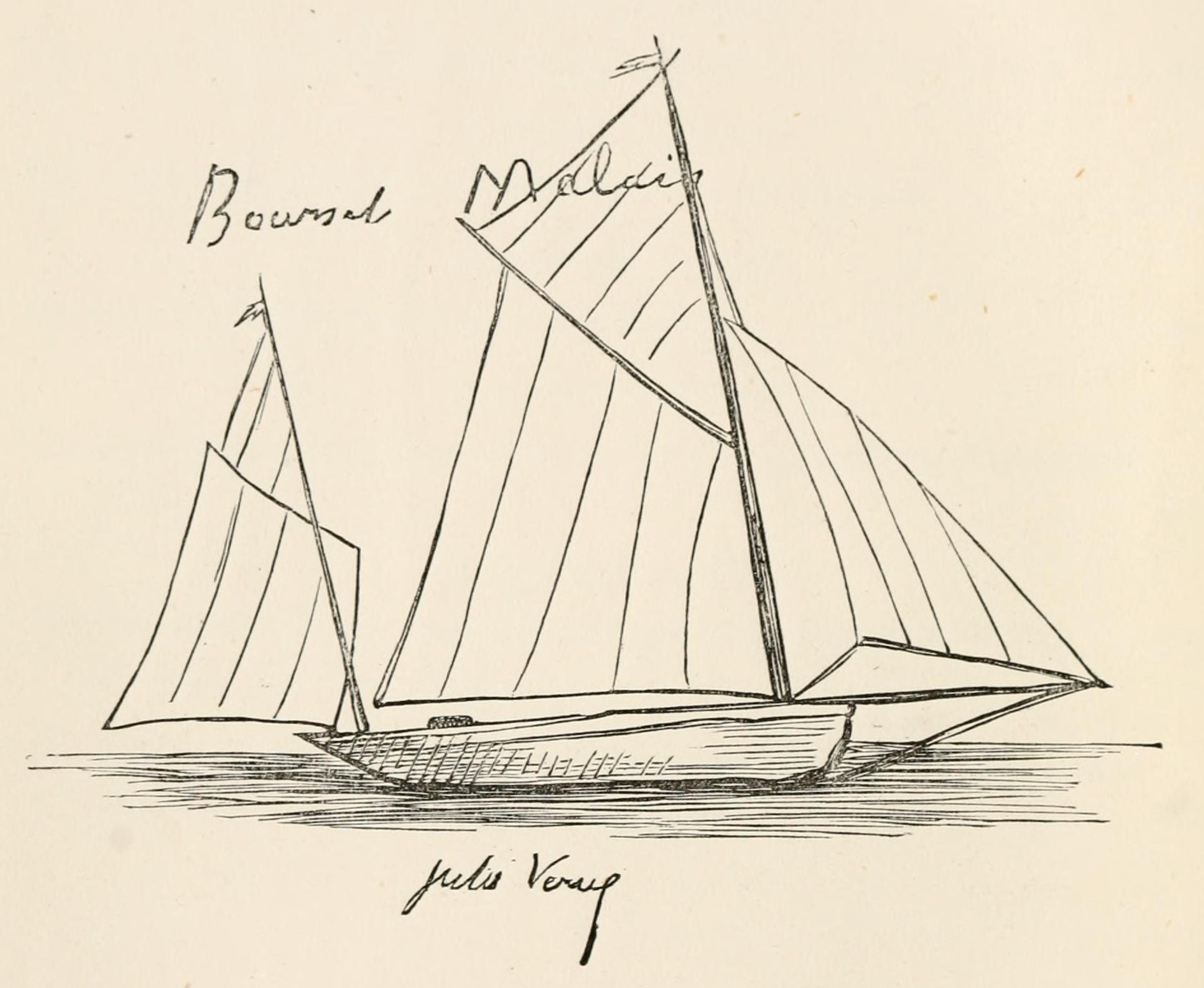

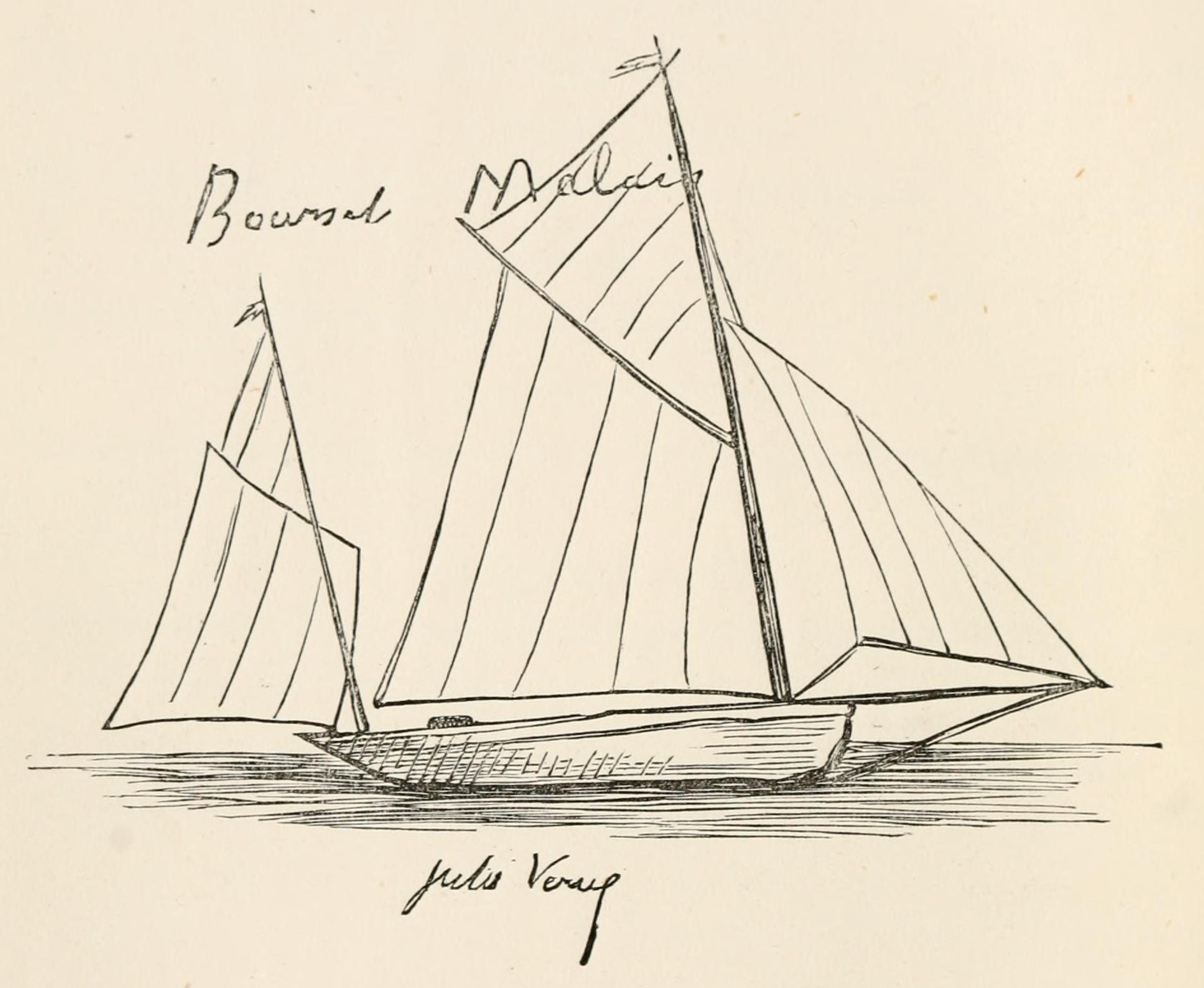

When ''The Adventures of Captain Hatteras'' was published in book form in 1866, Hetzel publicly announced his literary and educational ambitions for Verne's novels by saying in a preface that Verne's works would form a  In 1867, Verne bought a small boat, the ''Saint-Michel'', which he successively replaced with the ''Saint-Michel II'' and the ''Saint-Michel III'' as his financial situation improved. On board the ''Saint-Michel III'', he sailed around Europe. After his first novel, most of his stories were first serialised in the ''Magazine d'Éducation et de Récréation'', a Hetzel biweekly publication, before being published in book form. His brother Paul contributed to ''40th French climbing of the Mont-Blanc'' and a collection of short stories – ''Doctor Ox'' – in 1874. Verne became wealthy and famous.

Meanwhile, Michel Verne married an actress against his father's wishes, had two children by an underage mistress and buried himself in debts. The relationship between father and son improved as Michel grew older.

In 1867, Verne bought a small boat, the ''Saint-Michel'', which he successively replaced with the ''Saint-Michel II'' and the ''Saint-Michel III'' as his financial situation improved. On board the ''Saint-Michel III'', he sailed around Europe. After his first novel, most of his stories were first serialised in the ''Magazine d'Éducation et de Récréation'', a Hetzel biweekly publication, before being published in book form. His brother Paul contributed to ''40th French climbing of the Mont-Blanc'' and a collection of short stories – ''Doctor Ox'' – in 1874. Verne became wealthy and famous.

Meanwhile, Michel Verne married an actress against his father's wishes, had two children by an underage mistress and buried himself in debts. The relationship between father and son improved as Michel grew older.

Though raised as a

Though raised as a

Verne's largest body of work is the '' Voyages extraordinaires'' series, which includes all of his novels except for the two rejected manuscripts ''

Verne's largest body of work is the '' Voyages extraordinaires'' series, which includes all of his novels except for the two rejected manuscripts ''

Translation of Verne into English began in 1852, when Verne's short story '' A Voyage in a Balloon'' (1851) was published in the American journal ''Sartain's Magazine, Sartain's Union Magazine of Literature and Art'' in a translation by Anne Toppan Wilbur Wood, Anne T. Wilbur. Translation of his novels began in 1869 with William Lackland's translation of ''

Translation of Verne into English began in 1852, when Verne's short story '' A Voyage in a Balloon'' (1851) was published in the American journal ''Sartain's Magazine, Sartain's Union Magazine of Literature and Art'' in a translation by Anne Toppan Wilbur Wood, Anne T. Wilbur. Translation of his novels began in 1869 with William Lackland's translation of ''

The relationship between Verne's ''Voyages extraordinaires'' and the literary genre science fiction is a complex one. Verne, like

The relationship between Verne's ''Voyages extraordinaires'' and the literary genre science fiction is a complex one. Verne, like

Verne's novels have had a wide influence on both literary and scientific works; writers known to have been influenced by Verne include Marcel Aymé,

Verne's novels have had a wide influence on both literary and scientific works; writers known to have been influenced by Verne include Marcel Aymé,

Zvi Har'El's Jules Verne Collection

an extensive resource from the early 2000s

with sources, images, and ephemera

The North American Jules Verne Society

Maps

from Verne's books * *

Jules Verne's works

with Concordance (publishing), concordances and frequency list {{DEFAULTSORT:Verne, Jules Jules Verne, 1828 births 1905 deaths 19th-century French dramatists and playwrights 19th-century French essayists 19th-century French non-fiction writers 19th-century French novelists 19th-century French poets 19th-century French short story writers 20th-century French novelists Deaths from diabetes in France French deists French fantasy writers French historical fiction writers French horror writers French male dramatists and playwrights French male essayists French male non-fiction writers French male novelists French male poets French male short story writers French mystery writers French philosophers of technology French people of Scottish descent French science fiction writers History of science fiction Maritime writers Members of the Ligue de la patrie française Military science fiction writers Officers of the Legion of Honour Science Fiction Hall of Fame inductees Stockbrokers Surrealist writers Writers from Brittany Writers from Nantes Writers of Gothic fiction Writers of historical fiction set in the early modern period Writers who illustrated their own writing Writers about Russia Mythopoeic writers

Longman Pronunciation Dictionary

John Christopher Wells (born 11 March 1939) is a British phonetician and Esperantist. Wells is a professor emeritus at University College London, where until his retirement in 2006 he held the departmental chair in phonetics. He is known for h ...

''. ; 8 February 1828 – 24 March 1905) was a French novelist, poet

A poet is a person who studies and creates poetry. Poets may describe themselves as such or be described as such by others. A poet may simply be the creator (thought, thinker, songwriter, writer, or author) who creates (composes) poems (oral t ...

and playwright

A playwright or dramatist is a person who writes play (theatre), plays, which are a form of drama that primarily consists of dialogue between Character (arts), characters and is intended for Theatre, theatrical performance rather than just

Readin ...

.

His collaboration with the publisher Pierre-Jules Hetzel

Pierre-Jules Hetzel (; 15 January 1814 – 17 March 1886) was a French editor and publisher celebrated for his extraordinarily lavishly illustrated editions of Jules Verne's novels, highly prized by collectors.

Biography

Born in Chartres, Eure ...

led to the creation of the '' Voyages extraordinaires'', a series of bestselling adventure novels including ''Journey to the Center of the Earth

''Journey to the Center of the Earth'' (), also translated with the variant titles ''A Journey to the Centre of the Earth'' and ''A Journey into the Interior of the Earth'', is a classic science fiction novel written by French novelist Jules Ve ...

'' (1864), ''Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas

''Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas'' () is a science fiction

Science fiction (often shortened to sci-fi or abbreviated SF) is a genre of speculative fiction that deals with imaginative and futuristic concepts. These concepts may inclu ...

'' (1870), and ''Around the World in Eighty Days

''Around the World in Eighty Days'' () is an adventure novel by the French writer Jules Verne, first published in French in 1872. In the story, Phileas Fogg of London and his newly employed French valet Passepartout attempt to circumnavigate ...

'' (1872). His novels are generally set in the second half of the 19th century, taking into account contemporary scientific knowledge and the technological advances of the time.

In addition to his novels, he wrote numerous plays, short stories, autobiographical

An autobiography, sometimes informally called an autobio, is a self-written account of one's own life, providing a personal narrative that reflects on the author's experiences, memories, and insights. This genre allows individuals to share thei ...

accounts, poetry, songs, and scientific, artistic and literary studies. His work has been adapted for film and television since the beginning of cinema, as well as for comic books, theater, opera, music and video games.

Verne is considered to be an important author in France and most of Europe, where he has had a wide influence on the literary avant-garde

In the arts and literature, the term ''avant-garde'' ( meaning or ) identifies an experimental genre or work of art, and the artist who created it, which usually is aesthetically innovative, whilst initially being ideologically unacceptable ...

and on surrealism

Surrealism is an art movement, art and cultural movement that developed in Europe in the aftermath of World War I in which artists aimed to allow the unconscious mind to express itself, often resulting in the depiction of illogical or dreamlike s ...

. His reputation was markedly different in the Anglosphere

The Anglosphere, also known as the Anglo-American world, is a Western-led sphere of influence among the Anglophone countries. The core group of this sphere of influence comprises five developed countries that maintain close social, cultura ...

where he had often been labeled a writer of genre fiction

In the book-trade, genre fiction, also known as formula fiction, or commercial fiction,Girolimon, Mars"Types of Genres: A Literary Guide" Southern New Hampshire University, 11 December 2023. Retrieved 3 September 2024. encompasses fictional ...

or children's books, largely because of the highly abridged and altered translations

Translation is the communication of the meaning of a source-language text by means of an equivalent target-language text. The English language draws a terminological distinction (which does not exist in every language) between ''transl ...

in which his novels have often been printed. Since the 1980s, his literary reputation has improved.

Jules Verne has been the second most-translated author in the world since 1979, ranking below Agatha Christie

Dame Agatha Mary Clarissa Christie, Lady Mallowan, (; 15 September 1890 – 12 January 1976) was an English people, English author known for her 66 detective novels and 14 short story collections, particularly those revolving ...

and above William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

. He has sometimes been called the "father of science fiction

Science fiction (often shortened to sci-fi or abbreviated SF) is a genre of speculative fiction that deals with imaginative and futuristic concepts. These concepts may include information technology and robotics, biological manipulations, space ...

", a title that has also been given to H. G. Wells

Herbert George Wells (21 September 1866 – 13 August 1946) was an English writer, prolific in many genres. He wrote more than fifty novels and dozens of short stories. His non-fiction output included works of social commentary, politics, hist ...

and Hugo Gernsback

Hugo Gernsback (; born Hugo Gernsbacher, August 16, 1884 – August 19, 1967) was a Luxembourgish American editor and magazine publisher whose publications included the first science fiction magazine, ''Amazing Stories''. His contributions to ...

. In the 2010s, he was the most translated French author in the world. In France, 2005 was declared "Jules Verne Year" on the occasion of the centenary of the writer's death.

Life

Early life

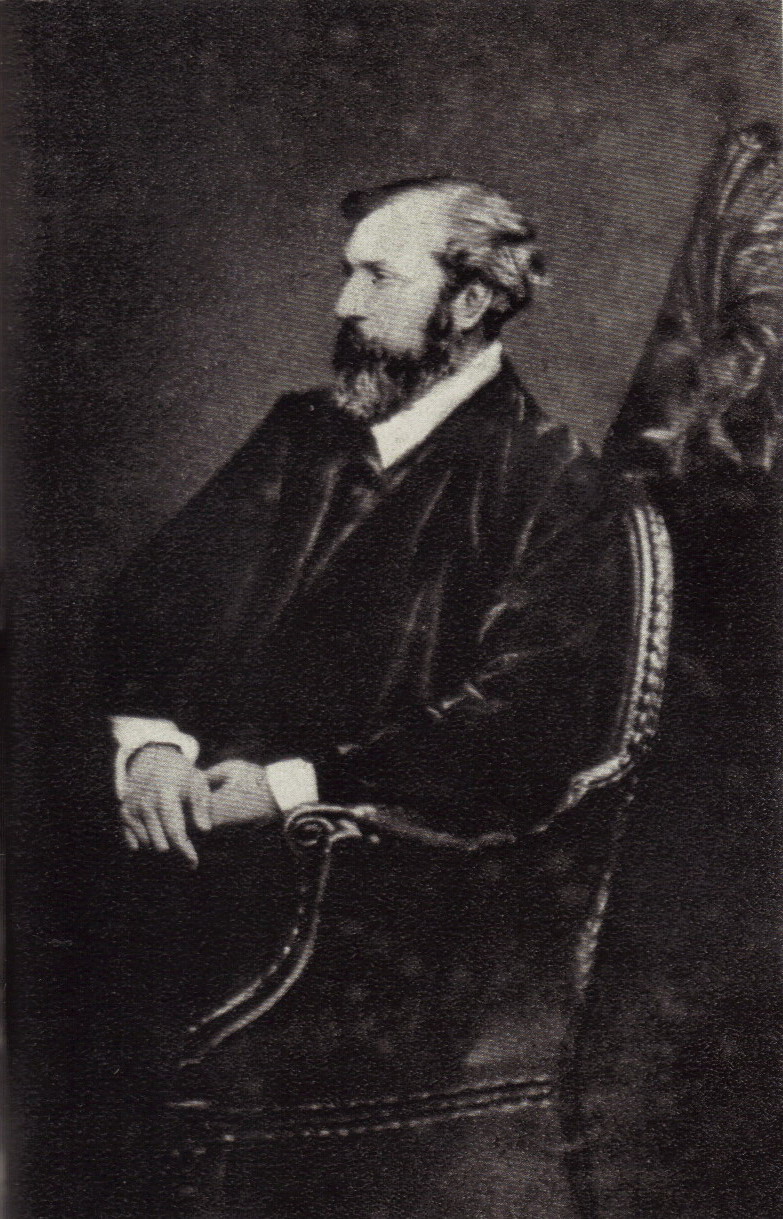

Verne was born on 8 February 1828, on Île Feydeau, a then small artificial island on the riverLoire

The Loire ( , , ; ; ; ; ) is the longest river in France and the 171st longest in the world. With a length of , it drains , more than a fifth of France's land, while its average discharge is only half that of the Rhône.

It rises in the so ...

within the town of Nantes

Nantes (, ; ; or ; ) is a city in the Loire-Atlantique department of France on the Loire, from the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic coast. The city is the List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, sixth largest in France, with a pop ...

(later filled in and incorporated into the surrounding land area), in No. 4 Rue Olivier-de-Clisson, the house of his maternal grandmother Dame Sophie Marie Adélaïde Julienne Allotte de La Fuÿe (born Guillochet de La Perrière). His parents were Pierre Verne, an ''avoué

In France and Belgium, an was formerly a jurist and a ministerial officer charged with performing the preparation () of cases in front of courts. Their functions were roughly equivalent to that of solicitor

A solicitor is a lawyer who tradition ...

'' originally from Provins

Provins () is a Communes of France, commune in the Seine-et-Marne Departments of France, department in the Île-de-France Regions of France, region in north-central France. Known for its well-preserved medieval architecture and importance througho ...

, and Sophie Allotte de La Fuÿe, a Nantes woman from a local family of navigators and shipowners, of distant Scottish

Scottish usually refers to something of, from, or related to Scotland, including:

*Scottish Gaelic, a Celtic Goidelic language of the Indo-European language family native to Scotland

*Scottish English

*Scottish national identity, the Scottish ide ...

descent. In 1829, the Verne family moved some hundred metres away to No. 2 Quai Jean-Bart, where Verne's brother Paul was born the same year. Three sisters, Anne "Anna" (1836), Mathilde (1839), and Marie (1842), followed.

In 1834, at the age of six, Verne was sent to boarding school at 5 Place du Bouffay in Nantes. The teacher, Madame Sambin, was the widow of a naval captain who had disappeared some 30 years before. Madame Sambin often told the students that her husband was a shipwrecked castaway and that he would eventually return like Robinson Crusoe

''Robinson Crusoe'' ( ) is an English adventure novel by Daniel Defoe, first published on 25 April 1719. Written with a combination of Epistolary novel, epistolary, Confessional writing, confessional, and Didacticism, didactic forms, the ...

from his desert island paradise. The theme of the robinsonade

Robinsonade ( ) is a literary genre of fiction wherein the protagonist is suddenly separated from civilization, usually by being shipwrecked or marooned on a secluded and uninhabited island, and must improvise the means of their survival from t ...

would stay with Verne throughout his life and appear in many of his novels, some of which include ''The Mysterious Island

''The Mysterious Island'' () is a novel by Jules Verne, serialised from August 1874 to September 1875 and then published in book form in November 1875. The first edition, published by Hetzel, contains illustrations by Jules Férat. The novel i ...

'' (1874), ''The Castaways of the Flag

''The Castaways of the Flag'' (, lit. ''Second Fatherland'', 1900) is an adventure novel written by Jules Verne. The two volumes of the novel were initially published in English translation as two separate volumes: ''Their Island Home'' and ''The ...

'' (1900), and ''The School for Robinsons

''Godfrey Morgan: A Californian Mystery'' (, literally ''The School for Robinsons''), also published as ''School for Crusoes'', is an 1882 adventure novel by French writer Jules Verne. The novel tells of a wealthy young man, Godfrey Morgan, who, ...

'' (1882).

In 1836, Verne went on to École Saint‑Stanislas, a Catholic school suiting the pious religious tastes of his father. Verne quickly distinguished himself in ''mémoire'' (recitation from memory), geography, Greek, Latin, and singing. In the same year, 1836, Pierre Verne bought a vacation house at 29 Rue des Réformés in the village of Chantenay (now part of Nantes) on the Loire. In his brief memoir ''Souvenirs d'enfance et de jeunesse'' (''Memories of Childhood and Youth'', 1890), Verne recalled a deep fascination with the river and with the many merchant vessel

A merchant ship, merchant vessel, trading vessel, or merchantman is a watercraft that transports cargo or carries passengers for hire. This is in contrast to pleasure craft, which are used for personal recreation, and naval ships, which a ...

s navigating it. He also took vacations at Brains, in the house of his uncle Prudent Allotte, a retired shipowner, who had gone around the world and served as mayor of Brains from 1828 to 1837. Verne took joy in playing interminable rounds of the Game of the Goose

The Game of the Goose, also known as the Royal Game of the Goose is one of the first board games to be commercially manufactured. It is a race game, relying only on dice throws to dictate progression of the players. The board is often arranged in t ...

with his uncle, and both the game and his uncle's name would be memorialized in two late novels ('' The Will of an Eccentric'' (1900) and ''Robur the Conqueror

''Robur the Conqueror'' () is a science fiction novel by Jules Verne, published in 1886. It is also known as ''The Clipper of the Clouds''. It has a sequel, '' Master of the World'', which was published in 1904.

Plot summary

The story begins ...

'' (1886), respectively).

Legend has it that in 1839, at the age of 11, Verne secretly procured a spot as cabin boy

A cabin boy or ship's boy is a boy or young man who waits on the officers and passengers of a ship, especially running errands for the captain. The modern merchant navy successor to the cabin boy is the steward's assistant.

Duties

Cabin boys ...

on the three-mast ship ''Coralie'' with the intention of traveling to the Indies and bringing back a coral necklace for his cousin Caroline. The evening the ship set out for the Indies, it stopped first at Paimboeuf where Pierre Verne arrived just in time to catch his son and make him promise to travel "only in his imagination". It is now known that the legend is an exaggerated tale invented by Verne's first biographer, his niece Marguerite Allotte de la Füye, though it may have been inspired by a real incident.

In 1840, the Vernes moved again to a large apartment at No. 6 Rue Jean-Jacques-Rousseau, where the family's youngest child, Marie, was born in 1842. In the same year Verne entered another religious school, the Petit Séminaire de Saint-Donatien, as a lay student. His unfinished novel ''Un prêtre en 1839'' ('' A Priest in 1839''), written in his teens and the earliest of his prose works to survive, describes the seminary in disparaging terms. From 1844 to 1846, Verne and his brother were enrolled in the Lycée Royal (now the Lycée Georges-Clemenceau) in Nantes. After finishing classes in rhetoric and philosophy, he took the baccalauréat

The ''baccalauréat'' (; ), often known in France colloquially as the ''bac'', is a French national academic qualification that students can obtain at the completion of their secondary education (at the end of the ''lycée'') by meeting certain ...

at Rennes

Rennes (; ; Gallo language, Gallo: ''Resnn''; ) is a city in the east of Brittany in Northwestern France at the confluence of the rivers Ille and Vilaine. Rennes is the prefecture of the Brittany (administrative region), Brittany Regions of F ...

and received the grade "Good Enough" on 29 July 1846.

By 1847, when Verne was 19, he had taken seriously to writing long works in the style of Victor Hugo

Victor-Marie Hugo, vicomte Hugo (; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French Romanticism, Romantic author, poet, essayist, playwright, journalist, human rights activist and politician.

His most famous works are the novels ''The Hunchbac ...

, beginning ''Un prêtre en 1839'' and seeing two verse tragedies, ''Alexandre VI'' and ''La Conspiration des poudres'' (''The Gunpowder Plot''), to completion. However, his father took it for granted that Verne, being the firstborn son of the family, would not attempt to make money in literature but would instead inherit the family law practice.

In 1847, Verne's father sent him to Paris, primarily to begin his studies in law school, and secondarily (according to family legend) to distance him temporarily from Nantes. His cousin Caroline, with whom he was in love, was married on 27 April 1847, to Émile Dezaunay, a man of 40, with whom she would have five children.

After a short stay in Paris, where he passed first-year law exams, Verne returned to Nantes for his father's help in preparing for the second year. (Provincial law students were in that era required to go to Paris to take exams.) While in Nantes, he met Rose Herminie Arnaud Grossetière, a young woman one year his senior, and fell intensely in love with her. He wrote and dedicated some thirty poems to her, including ''La Fille de l'air'' (''The Daughter of Air''), which describes her as "blonde and enchanting / winged and transparent". His passion seems to have been reciprocated, at least for a short time, but Grossetière's parents frowned upon the idea of their daughter marrying a young student of uncertain future. They married her instead to Armand Terrien de la Haye, a rich landowner ten years her senior, on 19 July 1848.

The sudden marriage sent Verne into deep frustration. He wrote a hallucinatory letter to his mother, apparently composed in a state of half-drunkenness, in which under pretext of a dream he described his misery. This requited but aborted love affair seems to have permanently marked the author and his work, and his novels include a significant number of young women married against their will (Gérande in '' Master Zacharius'' (1854), Sava in '' Mathias Sandorf'' (1885), Ellen in '' A Floating City'' (1871), etc.), to such an extent that the scholar Christian Chelebourg attributed the recurring theme to a "Herminie complex". The incident also led Verne to bear a grudge against his birthplace and Nantes society, which he criticized in his poem ''La sixième ville de France'' (''The Sixth City of France'').

Studies in Paris

In July 1848, Verne left Nantes again for Paris, where his father intended him to finish law studies and take up law as a profession. He obtained permission from his father to rent a furnished apartment at 24 Rue de l'Ancienne-Comédie, which he shared with Édouard Bonamy, another student of Nantes origin. (On his 1847 Paris visit, Verne had stayed at 2 Rue Thérèse, the house of his aunt Charuel, on the Butte Saint-Roch.) Verne arrived in Paris during a time of political upheaval: theFrench Revolution of 1848

The French Revolution of 1848 (), also known as the February Revolution (), was a period of civil unrest in France, in February 1848, that led to the collapse of the July Monarchy and the foundation of the French Second Republic. It sparked t ...

. In February, Louis Philippe I

Louis Philippe I (6 October 1773 – 26 August 1850), nicknamed the Citizen King, was King of the French from 1830 to 1848, the penultimate monarch of France, and the last French monarch to bear the title "King". He abdicated from his throne ...

had been overthrown and had fled; on 24 February, a provisional government of the French Second Republic

The French Second Republic ( or ), officially the French Republic (), was the second republican government of France. It existed from 1848 until its dissolution in 1852.

Following the final defeat of Napoleon, Napoleon Bonaparte at the Battle ...

took power, but political demonstrations continued, and social tension remained. In June, barricades went up in Paris, and the government sent Louis-Eugène Cavaignac

Louis-Eugène Cavaignac (; 15 October 1802 – 28 October 1857) was a French general and politician who served as head of the executive power of France between June and December 1848, during the French Second Republic.

Born in Paris to a promi ...

to crush the insurrection. Verne entered the city shortly before the election of Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte as the first president of the Republic, a state of affairs that would last until the French coup of 1851

French may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France

** French people, a nation and ethnic group

** French cuisine, cooking traditions and practices

Arts and media

* The French (band), ...

. In a letter to his family, Verne described the bombarded state of the city after the recent June Days uprising

The June Days uprising () was an uprising staged by French workers from 22 to 26 June 1848. It was in response to plans to close the National Workshops, created by the Second Republic in order to provide work and a minimal source of income f ...

but assured them that the anniversary of Bastille Day

Bastille Day is the common name given in English-speaking countries to the national day of France, which is celebrated on 14 July each year. It is referred to, both legally and commonly, as () in French, though ''la fête nationale'' is also u ...

had gone by without any significant conflict.

Verne used his family connections to make an entrance into Paris society. His uncle Francisque de Chatêaubourg introduced him into

Verne used his family connections to make an entrance into Paris society. His uncle Francisque de Chatêaubourg introduced him into literary salon

A salon is a gathering of people held by a host. These gatherings often consciously followed Horace's definition of the aims of poetry, "either to please or to educate" (Latin: ''aut delectare aut prodesse''). Salons in the tradition of the Fren ...

s, and Verne particularly frequented those of Mme de Barrère, a friend of his mother's. While continuing his law studies, he fed his passion for the theater, writing numerous plays. Verne later recalled: "I was greatly under the influence of Victor Hugo

Victor-Marie Hugo, vicomte Hugo (; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French Romanticism, Romantic author, poet, essayist, playwright, journalist, human rights activist and politician.

His most famous works are the novels ''The Hunchbac ...

, indeed, very excited by reading and re-reading his works. At that time I could have recited by heart whole pages of ''Notre Dame de Paris

Notre-Dame de Paris ( ; meaning "Cathedral of Our Lady of Paris"), often referred to simply as Notre-Dame, is a Medieval architecture, medieval Catholic cathedral on the Île de la Cité (an island in the River Seine), in the 4th arrondissemen ...

'', but it was his dramatic work that most influenced me." Another source of creative stimulation came from a neighbor: living on the same floor in the Rue de l'Ancienne-Comédie apartment house was a young composer, Aristide Hignard, with whom Verne soon became good friends, and Verne wrote several texts for Hignard to set as chanson

A (, ; , ) is generally any Lyrics, lyric-driven French song. The term is most commonly used in English to refer either to the secular polyphonic French songs of late medieval music, medieval and Renaissance music or to a specific style of ...

s.

During this period, Verne's letters to his parents primarily focused on expenses and on a suddenly appearing series of violent stomach cramps, the first of many he would suffer from during his life. (Modern scholars have hypothesized that he suffered from colitis

Colitis is swelling or inflammation

Inflammation (from ) is part of the biological response of body tissues to harmful stimuli, such as pathogens, damaged cells, or irritants. The five cardinal signs are heat, pain, redness, swelling, and ...

; Verne believed the illness to have been inherited from his mother's side.) Rumors of an outbreak of cholera

Cholera () is an infection of the small intestine by some Strain (biology), strains of the Bacteria, bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea last ...

in March 1849 exacerbated these medical concerns. Yet another health problem would strike in 1851 when Verne suffered the first of four attacks of facial paralysis. These attacks, rather than being psychosomatic

Somatic symptom disorder, also known as somatoform disorder or somatization disorder, is chronic somatization. One or more chronic physical symptoms coincide with excessive and maladaptive thoughts, emotions, and behaviors connected to those symp ...

, were due to an inflammation in the middle ear

The middle ear is the portion of the ear medial to the eardrum, and distal to the oval window of the cochlea (of the inner ear).

The mammalian middle ear contains three ossicles (malleus, incus, and stapes), which transfer the vibrations ...

, though this cause remained unknown to Verne during his life.

In the same year, Verne was required to enlist in the French army, but the sortition

In governance, sortition is the selection of public officer, officials or jurors at random, i.e. by Lottery (probability), lottery, in order to obtain a representative sample.

In ancient Athenian democracy, sortition was the traditional and pr ...

process spared him, to his great relief. He wrote to his father: "You should already know, dear papa, what I think of the military life, and of these domestic servants in livery. ... You have to abandon all dignity to perform such functions." Verne's strong antiwar sentiments, to the dismay of his father, would remain steadfast throughout his life.

Though writing profusely and frequenting the salons, Verne diligently pursued his law studies and graduated with a ''licence en droit'' in January 1851.

Literary debut

Thanks to his visits to salons, Verne came into contact in 1849 withAlexandre Dumas

Alexandre Dumas (born Alexandre Dumas Davy de la Pailleterie, 24 July 1802 – 5 December 1870), also known as Alexandre Dumas , was a French novelist and playwright.

His works have been translated into many languages and he is one of the mos ...

through the mutual acquaintance of a celebrated chirologist of the time, the Chevalier d'Arpentigny. Verne became close friends with Dumas' son, Alexandre Dumas fils

Alexandre Dumas (; 27 July 1824 – 27 November 1895) was a French author and playwright, best known for the romantic novel '' La Dame aux Camélias'' (''The Lady of the Camellias'', usually titled '' Camille'' in English-language versions), p ...

, and showed him a manuscript for a stage comedy, ''Les Pailles rompues'' (''The Broken Straws''). The two young men revised the play together, and Dumas, through arrangements with his father, had it produced by the Opéra-National at the Théâtre Historique in Paris, opening on 12 June 1850.

In 1851, Verne met with a fellow writer from Nantes, Pierre-Michel-François Chevalier (known as "Pitre-Chevalier"), the editor-in-chief of the magazine ''Musée des familles

''Musée des familles'' (''"Museum of Families"'') was an illustrated French literary magazine that was published in Paris from 1833 to 1900. It was founded by Émile de Girardin. The magazine was subtitled ''Lectures du soir'' (''"Readings in ...

'' (''The Family Museum''). Pitre-Chevalier was looking for articles about geography, history, science, and technology, and was keen to make sure that the educational component would be made accessible to large popular audiences using a straightforward prose style or an engaging fictional story. Verne, with his delight in diligent research, especially in geography, was a natural for the job. Verne first offered him a short historical

History is the systematic study of the past, focusing primarily on the human past. As an academic discipline, it analyses and interprets evidence to construct narratives about what happened and explain why it happened. Some theorists categ ...

adventure story

Adventure fiction is a type of fiction that usually presents danger, or gives the reader a sense of excitement. Some adventure fiction also satisfies the literary definition of romance fiction.

History

In the introduction to the ''Encyclopedi ...

, '' The First Ships of the Mexican Navy'', written in the style of James Fenimore Cooper

James Fenimore Cooper (September 15, 1789 – September 14, 1851) was an American writer of the first half of the 19th century, whose historical romances depicting colonial and indigenous characters from the 17th to the 19th centuries brought h ...

, whose novels had deeply influenced him. Pitre-Chevalier published it in July 1851, and in the same year published a second short story by Verne, '' A Voyage in a Balloon'' (August 1851). The latter story, with its combination of adventurous narrative, travel themes, and detailed historical research, would later be described by Verne as "the first indication of the line of novel that I was destined to follow".

Dumas fils put Verne in contact with Jules Seveste, a stage director who had taken over the directorship of the Théâtre Historique and renamed it the Théâtre Lyrique

The Théâtre Lyrique () was one of four opera companies performing in Paris during the middle of the 19th century (the other three being the Paris Opera, Opéra, the Opéra-Comique, and the Théâtre-Italien (1801–1878), Théâtre-Italien). ...

. Seveste offered Verne the job of secretary of the theater, with little or no salary attached. Verne accepted, using the opportunity to write and produce several comic operas written in collaboration with Hignard and the prolific librettist

A libretto (From the Italian word , ) is the text used in, or intended for, an extended musical work such as an opera, operetta, masque, oratorio, cantata or musical. The term ''libretto'' is also sometimes used to refer to the text of major ...

Michel Carré

Michel Carré (; 20 October 1821, Besançon – 27 June 1872, Argenteuil) was a prolific French librettist.

He went to Paris in 1840 intending to become a painter but took up writing instead. He wrote verse and plays before turning to writing li ...

. To celebrate his employment at the Théâtre Lyrique, Verne joined with ten friends to found a bachelors' dining club, the ''Onze-sans-femme'' (''Eleven Bachelors'').

For some time, Verne's father pressed him to abandon his writing and begin a business as a lawyer. However, Verne argued in his letters that he could only find success in literature. The pressure to plan for a secure future in law reached its climax in January 1852, when his father offered Verne his own Nantes law practice. Faced with this ultimatum, Verne decided conclusively to continue his literary life and refuse the job, writing: "Am I not right to follow my own instincts? It's because I know who I am that I realize what I can be one day."

Meanwhile, Verne was spending much time at the , conducting research for his stories and feeding his passion for science and recent discoveries, especially in geography

Geography (from Ancient Greek ; combining 'Earth' and 'write', literally 'Earth writing') is the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, and phenomena of Earth. Geography is an all-encompassing discipline that seeks an understanding o ...

. It was in this period that Verne met the illustrious geographer and explorer Jacques Arago

Jacques Étienne Victor Arago (6 March 1790 – 27 November 1855) was a French writer, artist and explorer, author of a ''Voyage Round the World''.

Biography

Jacques was born in Estagel, Pyrénées-Orientales. He was the brother of François Ar ...

, who continued to travel extensively despite his blindness (he had lost his sight completely in 1837). The two men became good friends, and Arago's innovative and witty accounts of his travels led Verne toward a newly developing genre of literature: that of travel writing

The genre of travel literature or travelogue encompasses outdoor literature, guide books, nature writing, and travel memoirs.

History

Early examples of travel literature include the '' Periplus of the Erythraean Sea'' (generally considered a ...

.

In 1852, two new pieces from Verne appeared in the ''Musée des familles'': '' Martin Paz'', a novella set in Lima

Lima ( ; ), founded in 1535 as the Ciudad de los Reyes (, Spanish for "City of Biblical Magi, Kings"), is the capital and largest city of Peru. It is located in the valleys of the Chillón River, Chillón, Rímac River, Rímac and Lurín Rive ...

, which Verne wrote in 1851 and published 10 July through 11 August 1852, and ''Les Châteaux en Californie, ou, Pierre qui roule n'amasse pas mousse'' (''The Castles in California, or, A Rolling Stone Gathers No Moss''), a one-act comedy full of racy double entendre

A double entendre (plural double entendres) is a figure of speech or a particular way of wording that is devised to have a double meaning, one of which is typically obvious, and the other often conveys a message that would be too socially unacc ...

s. In April and May 1854, the magazine published Verne's short story '' Master Zacharius'', an E. T. A. Hoffmann-like fantasy featuring a sharp condemnation of scientific hubris

Hubris (; ), or less frequently hybris (), is extreme or excessive pride or dangerous overconfidence and complacency, often in combination with (or synonymous with) arrogance.

Hubris, arrogance, and pretension are related to the need for vi ...

and ambition, followed soon afterward by '' A Winter Amid the Ice'', a polar adventure story whose themes closely anticipated many of Verne's novels. The ''Musée'' also published some nonfiction popular science

Popular science (also called pop-science or popsci) is an interpretation of science intended for a general audience. While science journalism focuses on recent scientific developments, popular science is more broad ranging. It may be written ...

articles which, though unsigned, are generally attributed to Verne. Verne's work for the magazine was cut short in 1856 when he had a serious quarrel with Pitre-Chevalier and refused to continue contributing (a refusal he would maintain until 1863, when Pitre-Chevalier died, and the magazine went to new editorship).

While writing stories and articles for Pitre-Chevalier, Verne began to form the idea of inventing a new kind of novel, a "Roman de la Science" ("novel of science"), which would allow him to incorporate large amounts of the factual information he so enjoyed researching in the Bibliothèque. He is said to have discussed the project with the elder Alexandre Dumas, who had tried something similar with an unfinished novel, ''Isaac Laquedem'', and who enthusiastically encouraged Verne's project.

At the end of 1854, another outbreak of cholera led to the death of Jules Seveste, Verne's employer at the Théâtre Lyrique and by then a good friend. Though his contract only held him to a further year of service, Verne remained connected to the theater for several years after Seveste's death, seeing additional productions to fruition. He also continued to write plays and musical comedies, most of which were not performed.

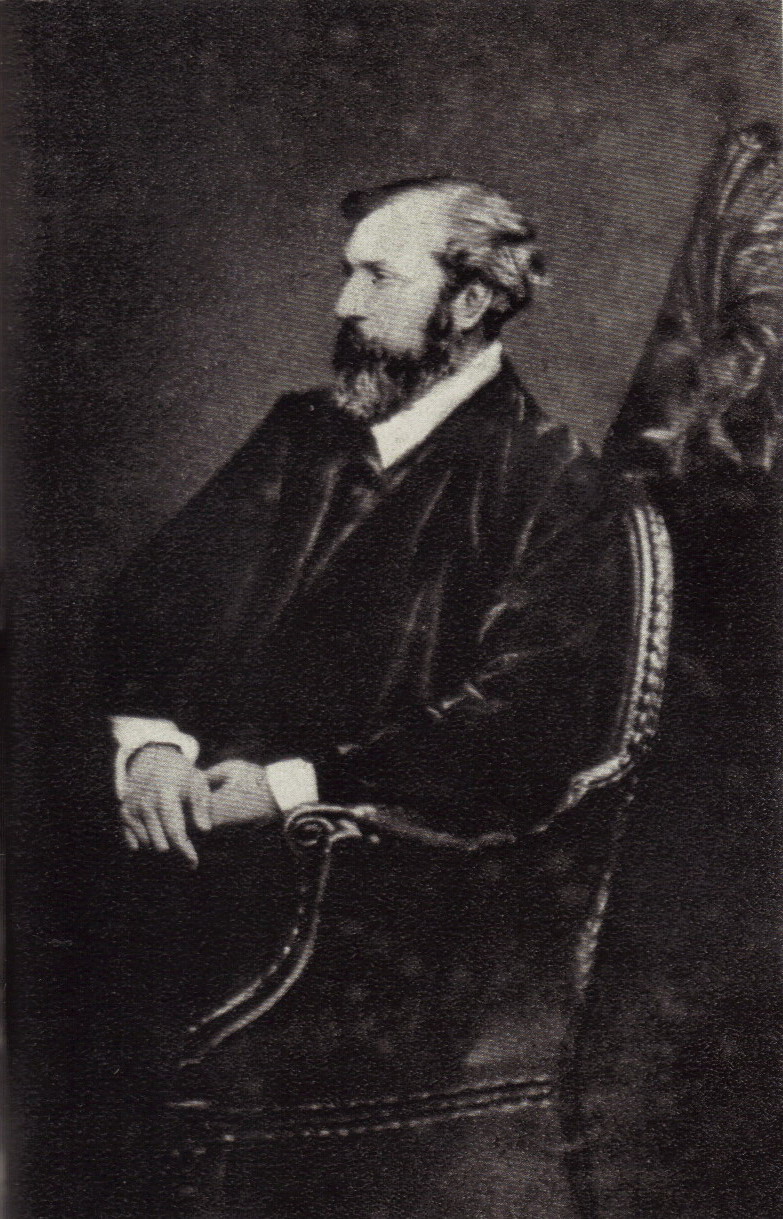

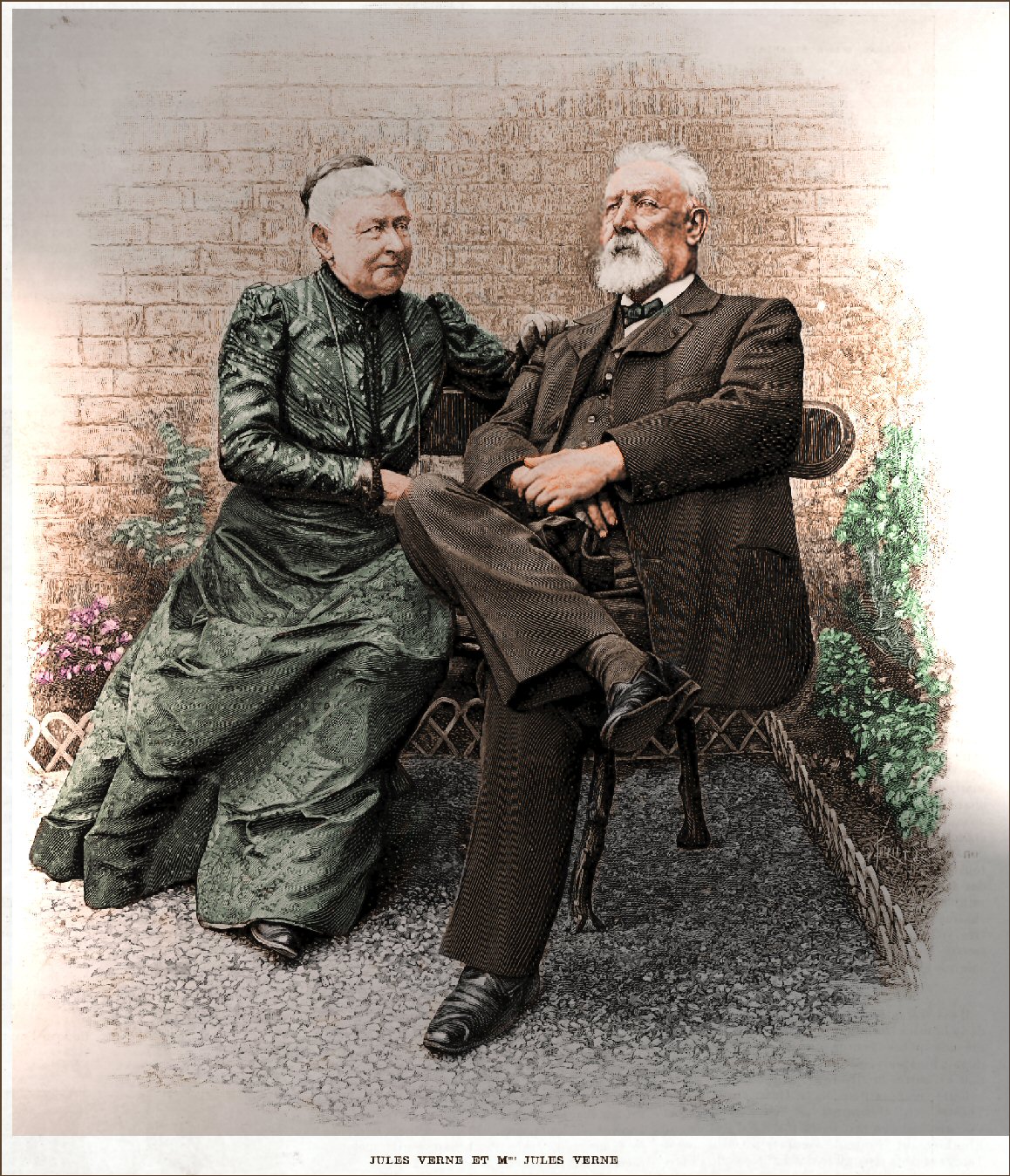

Family

In May 1856, Verne travelled toAmiens

Amiens (English: or ; ; , or ) is a city and Communes of France, commune in northern France, located north of Paris and south-west of Lille. It is the capital of the Somme (department), Somme Departments of France, department in the region ...

to be the best man

A groomsman or usher is one of the male attendants to the groom in a wedding ceremony. Usually, the groom selects close friends and relatives to serve as groomsmen, and it is considered an honor to be selected. From his groomsmen, the groom usuall ...

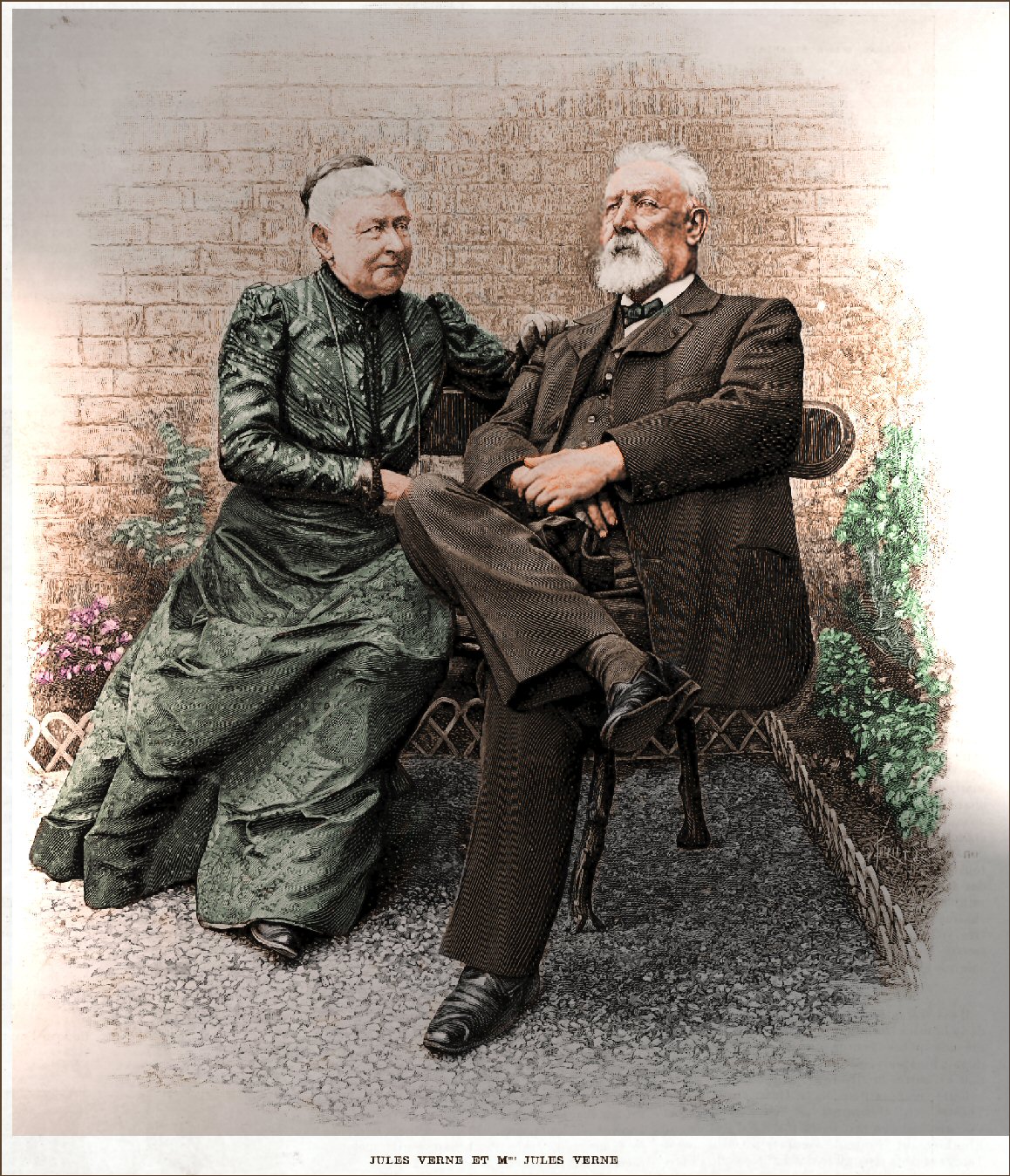

at the wedding of a Nantes friend, Auguste Lelarge, to an Amiens woman named Aimée du Fraysne de Viane. Verne, invited to stay with the bride's family, took to them warmly, befriending the entire household and finding himself increasingly attracted to the bride's sister, Honorine Anne Hébée Morel (née du Fraysne de Viane), a widow aged 26 with two young children. Hoping to find a secure source of income, as well as a chance to court Morel in earnest, he jumped at her brother's offer to go into business with a broker. Verne's father was initially dubious but gave in to his son's requests for approval in November 1856. With his financial situation finally looking promising, Verne won the favor of Morel and her family, and the couple were married on 10 January 1857.

Verne plunged into his new business obligations, leaving his work at the Théâtre Lyrique and taking up a full-time job as an ''agent de change'' on the

Verne plunged into his new business obligations, leaving his work at the Théâtre Lyrique and taking up a full-time job as an ''agent de change'' on the Paris Bourse

Euronext Paris, formerly known as the Paris Bourse (), is a regulated securities trading venue in France. It is Europe's second largest stock exchange by market capitalization, behind the London Stock Exchange, as of December 2023. As of 2022, th ...

, where he became the associate of the broker Fernand Eggly. Verne woke up early each morning so that he would have time to write, before going to the Bourse for the day's work; in the rest of his spare time, he continued to consort with the ''Onze-Sans-Femme'' club (all eleven of its "bachelors" had by this time married). He also continued to frequent the Bibliothèque to do scientific and historical research, much of which he copied onto notecards for future use—a system he would continue for the rest of his life. According to the recollections of a colleague, Verne "did better in repartee than in business".

In July 1858, Verne and Aristide Hignard seized an opportunity offered by Hignard's brother: a sea voyage, at no charge, from Bordeaux

Bordeaux ( ; ; Gascon language, Gascon ; ) is a city on the river Garonne in the Gironde Departments of France, department, southwestern France. A port city, it is the capital of the Nouvelle-Aquitaine region, as well as the Prefectures in F ...

to Liverpool

Liverpool is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. It is situated on the eastern side of the River Mersey, Mersey Estuary, near the Irish Sea, north-west of London. With a population ...

and Scotland. The journey, Verne's first trip outside France, deeply impressed him, and upon his return to Paris he fictionalized his recollections to form the backbone of a semi-autobiographical novel, '' Backwards to Britain'' (written in the autumn and winter of 1859–1860 and not published until 1989). A second complimentary voyage in 1861 took Hignard and Verne to Stockholm, from where they traveled to Christiania and through Telemark

Telemark () is a Counties of Norway, county and a current electoral district in Norway. Telemark borders the counties of Vestfold, Buskerud, Vestland, Rogaland and Agder. In 2020, Telemark merged with the county of Vestfold to form the county o ...

. Verne left Hignard in Denmark to return in haste to Paris, but missed the birth on 3 August 1861 of his only biological son, Michel.

Meanwhile, Verne continued work on the idea of a "Roman de la Science", which he developed in a rough draft, inspired, according to his recollections, by his "love for maps and the great explorers of the world". It took shape as a story of travel across Africa and would eventually become his first published novel, ''Five Weeks in a Balloon

''Five Weeks in a Balloon, or, A Journey of Discovery by Three Englishmen in Africa'' () is an adventure novel by Jules Verne, published in 1863. It is the first novel in which he perfected the "ingredients" of his later work, skillfully mixing ...

''.

Hetzel

In 1862, through their mutual acquaintance Alfred de Bréhat, Verne came into contact with the publisher

In 1862, through their mutual acquaintance Alfred de Bréhat, Verne came into contact with the publisher Pierre-Jules Hetzel

Pierre-Jules Hetzel (; 15 January 1814 – 17 March 1886) was a French editor and publisher celebrated for his extraordinarily lavishly illustrated editions of Jules Verne's novels, highly prized by collectors.

Biography

Born in Chartres, Eure ...

, and submitted to him the manuscript of his developing novel, then called ''Voyage en Ballon''. Hetzel, already the publisher of Honoré de Balzac

Honoré de Balzac ( , more commonly ; ; born Honoré Balzac; 20 May 1799 – 18 August 1850) was a French novelist and playwright. The novel sequence ''La Comédie humaine'', which presents a panorama of post-Napoleonic French life, is ...

, George Sand

Amantine Lucile Aurore Dupin de Francueil (; 1 July 1804 – 8 June 1876), best known by her pen name George Sand (), was a French novelist, memoirist and journalist. Being more renowned than either Victor Hugo or Honoré de Balz ...

, Victor Hugo

Victor-Marie Hugo, vicomte Hugo (; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French Romanticism, Romantic author, poet, essayist, playwright, journalist, human rights activist and politician.

His most famous works are the novels ''The Hunchbac ...

, and other well-known authors, had long been planning to launch a high-quality family magazine in which entertaining fiction would combine with scientific education. He saw Verne, with his demonstrated inclination toward scrupulously researched adventure stories, as an ideal contributor for such a magazine, and accepted the novel, giving Verne suggestions for improvement. Verne made the proposed revisions within two weeks and returned to Hetzel with the final draft, now titled ''Five Weeks in a Balloon

''Five Weeks in a Balloon, or, A Journey of Discovery by Three Englishmen in Africa'' () is an adventure novel by Jules Verne, published in 1863. It is the first novel in which he perfected the "ingredients" of his later work, skillfully mixing ...

''. It was published by Hetzel on 31 January 1863.

To secure his services for the planned magazine, to be called the ''Magasin d'Éducation et de Récréation'' (''Magazine of Education and Recreation''), Hetzel also drew up a long-term contract in which Verne would give him three volumes of text per year, each of which Hetzel would buy outright for a flat fee. Verne, finding both a steady salary and a sure outlet for writing at last, accepted immediately. For the rest of his lifetime, most of his novels would be serialized in Hetzel's ''Magasin'' before their appearance in book form, beginning with his second novel for Hetzel, ''The Adventures of Captain Hatteras

''The Adventures of Captain Hatteras'' () is an 1866 adventure novel by Jules Verne in two parts: ''The English at the North Pole'' () and ''The Desert of Ice'' ().

The novel was published for the first time in 1864 as a serial in the French maga ...

'' (1864–65).

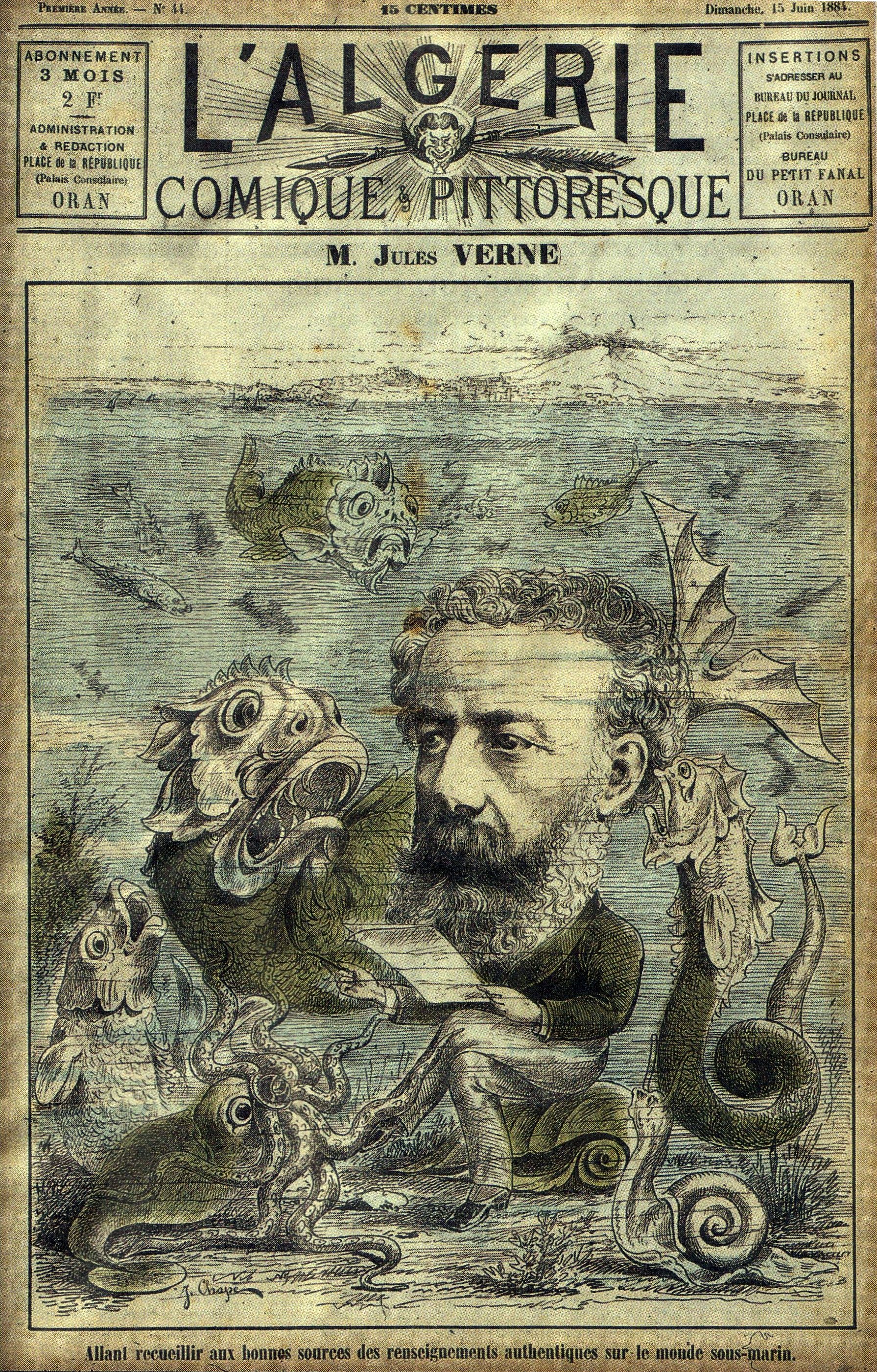

When ''The Adventures of Captain Hatteras'' was published in book form in 1866, Hetzel publicly announced his literary and educational ambitions for Verne's novels by saying in a preface that Verne's works would form a

When ''The Adventures of Captain Hatteras'' was published in book form in 1866, Hetzel publicly announced his literary and educational ambitions for Verne's novels by saying in a preface that Verne's works would form a novel sequence

A book series is a sequence of books having certain characteristics in common that are formally identified together as a group. Book series can be organized in different ways, such as written by the same author, or marketed as a group by their publ ...

called the '' Voyages extraordinaires'' (''Extraordinary Voyages'' or ''Extraordinary Journeys''), and that Verne's aim was "to outline all the geographical, geological, physical, and astronomical knowledge amassed by modern science and to recount, in an entertaining and picturesque format that is his own, the history of the universe". Late in life, Verne confirmed that this commission had become the running theme of his novels: "My object has been to depict the earth, and not the earth alone, but the universe... And I have tried at the same time to realize a very high ideal of beauty of style. It is said that there can't be any style in a novel of adventure, but it isn't true." However, he also noted that the project was extremely ambitious: "Yes! But the Earth is very large, and life is very short! In order to leave a completed work behind, one would need to live to be at least 100 years old!"

Hetzel influenced many of Verne's novels directly, especially in the first few years of their collaboration, for Verne was initially so happy to find a publisher that he agreed to almost all of the changes Hetzel suggested. For example, when Hetzel disapproved of the original climax of ''Captain Hatteras'', including the death of the title character, Verne wrote an entirely new conclusion in which Hatteras survived. Hetzel also rejected Verne's next submission, ''Paris in the Twentieth Century

''Paris in the Twentieth Century'' () is a science fiction novel by Jules Verne. The book presents Paris in August 1960, 97 years in Verne's future, when society places value only on business and technology.

Written in 1863, but first published ...

'', believing its pessimistic view of the future and its condemnation of technological progress were too subversive for a family magazine. (The manuscript, believed lost for some time after Verne's death, was finally published in 1994.)

The relationship between publisher and writer changed significantly around 1869 when Verne and Hetzel were brought into conflict over the manuscript for ''Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas

''Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas'' () is a science fiction

Science fiction (often shortened to sci-fi or abbreviated SF) is a genre of speculative fiction that deals with imaginative and futuristic concepts. These concepts may inclu ...

''. Verne had initially conceived of the submariner Captain Nemo

Captain Nemo (; also known as Prince Dakkar) is a character created by the French novelist Jules Verne (1828–1905). Nemo appears in two of Verne's science-fiction books, ''Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas'' (1870) and '' The Mysterious Is ...

as a Polish scientist whose acts of vengeance were directed against the Russians who had killed his family during the January Uprising

The January Uprising was an insurrection principally in Russia's Kingdom of Poland that was aimed at putting an end to Russian occupation of part of Poland and regaining independence. It began on 22 January 1863 and continued until the last i ...

. Hetzel, not wanting to alienate the lucrative Russian market for Verne's books, demanded that Nemo be made an enemy of the slave trade Slave trade may refer to:

* History of slavery - overview of slavery

It may also refer to slave trades in specific countries, areas:

* Al-Andalus slave trade

* Atlantic slave trade

** Brazilian slave trade

** Bristol slave trade

** Danish sl ...

, a situation that would make him an unambiguous hero. Verne, after fighting vehemently against the change, finally invented a compromise in which Nemo's past is left mysterious. After this disagreement, Verne became notably cooler in his dealings with Hetzel, taking suggestions into consideration but often rejecting them outright.

From that point, Verne published two or more volumes a year. The most successful of these are: (''Journey to the Center of the Earth

''Journey to the Center of the Earth'' (), also translated with the variant titles ''A Journey to the Centre of the Earth'' and ''A Journey into the Interior of the Earth'', is a classic science fiction novel written by French novelist Jules Ve ...

'', 1864); (''From the Earth to the Moon

''From the Earth to the Moon: A Direct Route in 97 Hours, 20 Minutes'' () is an 1865 novel by Jules Verne. It tells the story of the Baltimore Gun Club, a post-American Civil War society of weapons enthusiasts, and their attempts to build an en ...

'', 1865); ''Vingt mille lieues sous les mers'' (''Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas

''Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas'' () is a science fiction

Science fiction (often shortened to sci-fi or abbreviated SF) is a genre of speculative fiction that deals with imaginative and futuristic concepts. These concepts may inclu ...

'', 1869); and ''Le tour du monde en quatre-vingts jours'' (''Around the World in Eighty Days

''Around the World in Eighty Days'' () is an adventure novel by the French writer Jules Verne, first published in French in 1872. In the story, Phileas Fogg of London and his newly employed French valet Passepartout attempt to circumnavigate ...

''), which first appeared in ''Le Temps'' in 1872. Verne could now live on his writings, but most of his wealth came from the stage adaptations of ''Le tour du monde en quatre-vingts jours'' (1874) and '' Michel Strogoff'' (1876), which he wrote with Adolphe d'Ennery

Adolphe d'Ennery (; or Dennery; Adolphe Philippe; 17 June 181125 January 1899) was a French playwright and novelist.

Life

Born in Paris, his real surname was Philippe. He obtained his first success in collaboration with Charles Desnoyer in ' ...

.

In 1867, Verne bought a small boat, the ''Saint-Michel'', which he successively replaced with the ''Saint-Michel II'' and the ''Saint-Michel III'' as his financial situation improved. On board the ''Saint-Michel III'', he sailed around Europe. After his first novel, most of his stories were first serialised in the ''Magazine d'Éducation et de Récréation'', a Hetzel biweekly publication, before being published in book form. His brother Paul contributed to ''40th French climbing of the Mont-Blanc'' and a collection of short stories – ''Doctor Ox'' – in 1874. Verne became wealthy and famous.

Meanwhile, Michel Verne married an actress against his father's wishes, had two children by an underage mistress and buried himself in debts. The relationship between father and son improved as Michel grew older.

In 1867, Verne bought a small boat, the ''Saint-Michel'', which he successively replaced with the ''Saint-Michel II'' and the ''Saint-Michel III'' as his financial situation improved. On board the ''Saint-Michel III'', he sailed around Europe. After his first novel, most of his stories were first serialised in the ''Magazine d'Éducation et de Récréation'', a Hetzel biweekly publication, before being published in book form. His brother Paul contributed to ''40th French climbing of the Mont-Blanc'' and a collection of short stories – ''Doctor Ox'' – in 1874. Verne became wealthy and famous.

Meanwhile, Michel Verne married an actress against his father's wishes, had two children by an underage mistress and buried himself in debts. The relationship between father and son improved as Michel grew older.

Later years

Though raised as a

Though raised as a Roman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

, Verne gravitated towards deism

Deism ( or ; derived from the Latin term '' deus'', meaning "god") is the philosophical position and rationalistic theology that generally rejects revelation as a source of divine knowledge and asserts that empirical reason and observation ...

.

Some scholars believe his novels reflect a deist philosophy, as they often involve the notion of God or divine providence

In theology, divine providence, or simply providence, is God's intervention in the universe. The term ''Divine Providence'' (usually capitalized) is also used as a names of God, title of God. A distinction is usually made between "general prov ...

but rarely mention the concept of Christ.

On 9 March 1886, as Verne returned home, his twenty-six-year-old nephew, Gaston, shot at him twice with a pistol

A pistol is a type of handgun, characterised by a gun barrel, barrel with an integral chamber (firearms), chamber. The word "pistol" derives from the Middle French ''pistolet'' (), meaning a small gun or knife, and first appeared in the Englis ...

. The first bullet missed, but the second one entered Verne's left leg, giving him a permanent limp that could not be overcome. This incident was not publicised in the media, but Gaston spent the rest of his life in a mental asylum

The lunatic asylum, insane asylum or mental asylum was an institution where people with mental illness were confined. It was an early precursor of the modern psychiatric hospital.

Modern psychiatric hospitals evolved from and eventually replace ...

.

After the deaths of both his mother and Hetzel (who died in 1886), Jules Verne began publishing darker works. In 1888 he entered politics and was elected town councillor of Amiens

Amiens (English: or ; ; , or ) is a city and Communes of France, commune in northern France, located north of Paris and south-west of Lille. It is the capital of the Somme (department), Somme Departments of France, department in the region ...

, where he championed several improvements and served for fifteen years.

Verne was made a knight

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of a knighthood by a head of state (including the pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church, or the country, especially in a military capacity.

The concept of a knighthood ...

of France's Legion of Honour

The National Order of the Legion of Honour ( ), formerly the Imperial Order of the Legion of Honour (), is the highest and most prestigious French national order of merit, both military and Civil society, civil. Currently consisting of five cl ...

on 9 April 1870, and subsequently promoted in Legion of Honour

The National Order of the Legion of Honour ( ), formerly the Imperial Order of the Legion of Honour (), is the highest and most prestigious French national order of merit, both military and Civil society, civil. Currently consisting of five cl ...

rank to Officer on 19 July 1892.

Death and posthumous publications

On 24 March 1905, while ill with chronicdiabetes

Diabetes mellitus, commonly known as diabetes, is a group of common endocrine diseases characterized by sustained high blood sugar levels. Diabetes is due to either the pancreas not producing enough of the hormone insulin, or the cells of th ...

and complications from a stroke which paralyzed his right side, Verne died at his home in Amiens

Amiens (English: or ; ; , or ) is a city and Communes of France, commune in northern France, located north of Paris and south-west of Lille. It is the capital of the Somme (department), Somme Departments of France, department in the region ...

, 44 Boulevard Longueville (now Boulevard Jules-Verne). His son, Michel Verne, oversaw the publication of the novels '' Invasion of the Sea'' and ''The Lighthouse at the End of the World

''The Lighthouse at the End of the World'' () is an adventure novel by French author Jules Verne. Verne wrote the first draft in 1901.William Butcher, Jules Verne: The Definitive Biography', Thunder's Mouth Press, 2006, p. 292. . The edite ...

'' after Jules's death. The ''Voyages extraordinaires'' series continued for several years afterwards at the same rate of two volumes a year. It was later discovered that Michel Verne had made extensive changes in these stories, and the original versions were eventually published at the end of the 20th century by the Jules Verne Society (Société Jules Verne). In 1919, Michel Verne published ''The Barsac Mission

''The Barsac Mission'' () is a novel attributed to Jules Verne and written (with inspiration from two unfinished Verne manuscripts) by his son Michel Verne. First serialized in 1914, it was published in book form by Hachette in 1919. An English ...

'' (), whose original drafts contained references to Esperanto

Esperanto (, ) is the world's most widely spoken Constructed language, constructed international auxiliary language. Created by L. L. Zamenhof in 1887 to be 'the International Language' (), it is intended to be a universal second language for ...

, a language that his father had been very interested in. In 1989, Verne's great-grandson discovered his ancestor's as-yet-unpublished novel ''Paris in the Twentieth Century

''Paris in the Twentieth Century'' () is a science fiction novel by Jules Verne. The book presents Paris in August 1960, 97 years in Verne's future, when society places value only on business and technology.

Written in 1863, but first published ...

'', which was subsequently published in 1994.

Works

Verne's largest body of work is the '' Voyages extraordinaires'' series, which includes all of his novels except for the two rejected manuscripts ''

Verne's largest body of work is the '' Voyages extraordinaires'' series, which includes all of his novels except for the two rejected manuscripts ''Paris in the Twentieth Century

''Paris in the Twentieth Century'' () is a science fiction novel by Jules Verne. The book presents Paris in August 1960, 97 years in Verne's future, when society places value only on business and technology.

Written in 1863, but first published ...

'' and '' Backwards to Britain'' (published posthumously in 1994 and 1989, respectively) and for projects left unfinished at his death (many of which would be posthumously adapted or rewritten for publication by his son Michel). Verne also wrote many plays, poems, song texts, operetta

Operetta is a form of theatre and a genre of light opera. It includes spoken dialogue, songs and including dances. It is lighter than opera in terms of its music, orchestral size, and length of the work. Apart from its shorter length, the oper ...

libretti

A libretto (From the Italian word , ) is the text used in, or intended for, an extended musical work such as an opera, operetta, masque, oratorio, cantata or musical. The term ''libretto'' is also sometimes used to refer to the text of major l ...

, and short stories, as well as a variety of essays and miscellaneous non-fiction.

Literary reception

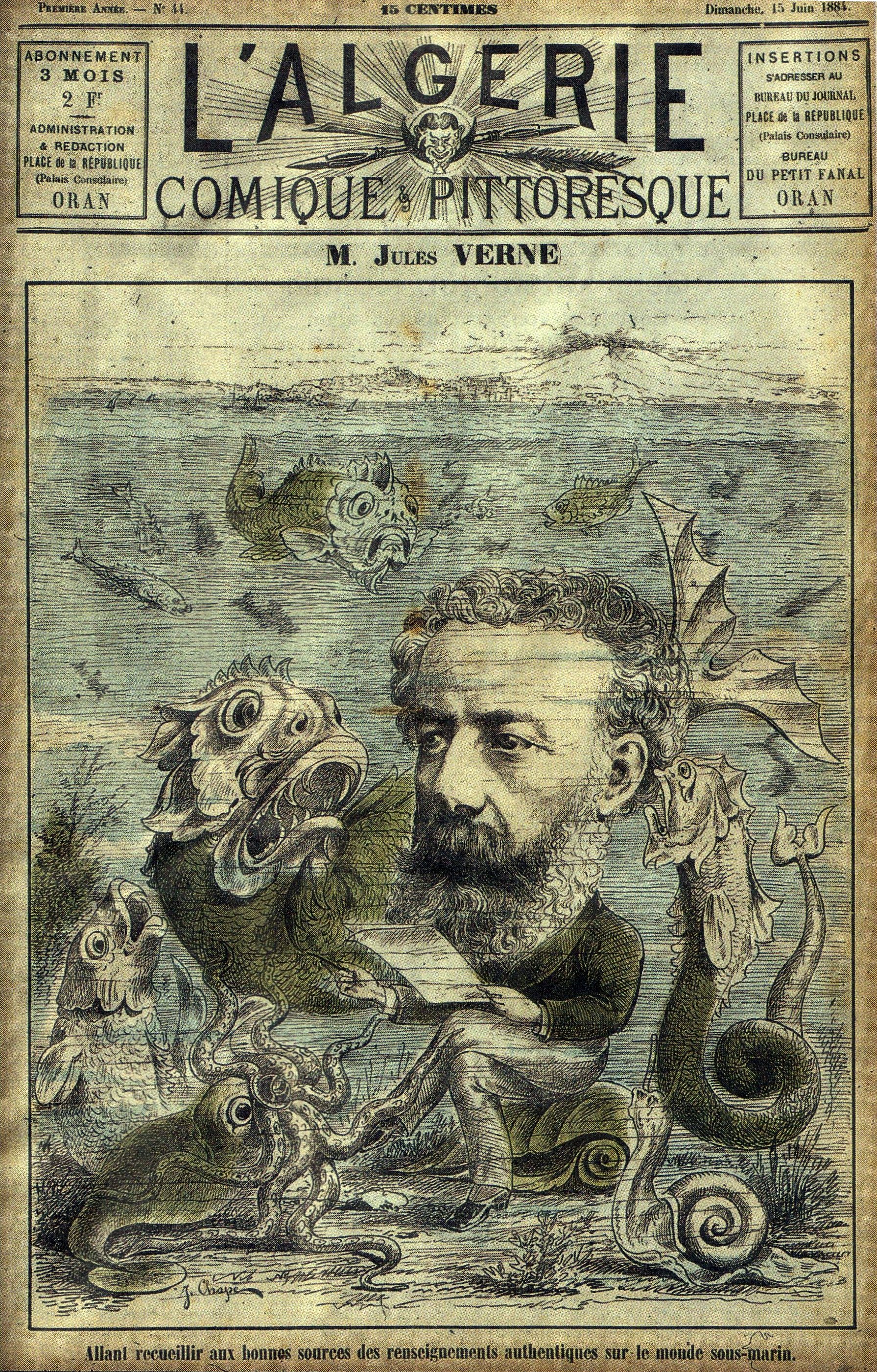

After his debut under Hetzel, Verne was enthusiastically received in France by writers and scientists alike, withGeorge Sand

Amantine Lucile Aurore Dupin de Francueil (; 1 July 1804 – 8 June 1876), best known by her pen name George Sand (), was a French novelist, memoirist and journalist. Being more renowned than either Victor Hugo or Honoré de Balz ...

and Théophile Gautier

Pierre Jules Théophile Gautier ( , ; 30 August 1811 – 23 October 1872) was a French poet, dramatist, novelist, journalist, and art and literary critic.

While an ardent defender of Romanticism, Gautier's work is difficult to classify and rema ...

among his earliest admirers. Several notable contemporary figures, from the geographer Vivien de Saint-Martin to the critic Jules Claretie

Jules is the French form of the Latin "Julius" (e.g. Jules César, the French name for Julius Caesar).

In the anglosphere, it is also used for females although it is still a predominantly masculine name.One of the few notable examples of a femal ...

, spoke highly of Verne and his works in critical and biographical notes.

However, Verne's growing popularity among readers and playgoers (due especially to the highly successful stage version of ''Around the World in Eighty Days'') led to a gradual change in his literary reputation. As the novels and stage productions continued to sell, many contemporary critics felt that Verne's status as a commercially popular author meant he could only be seen as a mere genre-based storyteller, rather than a serious author worthy of academic study.

This denial of formal literary status took various forms, including dismissive criticism by such writers as Émile Zola

Émile Édouard Charles Antoine Zola (, ; ; 2 April 184029 September 1902) was a French novelist, journalist, playwright, the best-known practitioner of the literary school of Naturalism (literature), naturalism, and an important contributor to ...

and the lack of Verne's nomination for membership in the Académie Française

An academy (Attic Greek: Ἀκαδήμεια; Koine Greek Ἀκαδημία) is an institution of tertiary education. The name traces back to Plato's school of philosophy, founded approximately 386 BC at Akademia, a sanctuary of Athena, the go ...

, and was recognized by Verne himself, who said in a late interview: "The great regret of my life is that I have never taken any place in French literature." To Verne, who considered himself "a man of letters and an artist, living in the pursuit of the ideal", this critical dismissal on the basis of literary ideology could only be seen as the ultimate snub.

This bifurcation of Verne as a popular genre writer but a critical ''persona non grata

In diplomacy, a ' (PNG) is a foreign diplomat that is asked by the host country to be recalled to their home country. If the person is not recalled as requested, the host state may refuse to recognize the person concerned as a member of the diplo ...

'' continued after his death, with early biographies (including one by Verne's own niece, Marguerite Allotte de la Fuÿe) focusing on error-filled and embroidered hagiography

A hagiography (; ) is a biography of a saint or an ecclesiastical leader, as well as, by extension, an adulatory and idealized biography of a preacher, priest, founder, saint, monk, nun or icon in any of the world's religions. Early Christian ...

of Verne as a popular figure rather than on Verne's actual working methods or his output. Meanwhile, sales of Verne's novels in their original unabridged versions dropped markedly even in Verne's home country, with abridged versions aimed directly at children taking their place.

However, the decades after Verne's death also saw the rise in France of the "Jules Verne cult", a steadily growing group of scholars and young writers who took Verne's works seriously as literature and willingly noted his influence on their own pioneering works. Some of the cult founded the Société Jules Verne, the first academic society for Verne scholars; many others became highly respected ''avant garde

In the arts and literature, the term ''avant-garde'' ( meaning or ) identifies an experimental genre or work of art, and the artist who created it, which usually is aesthetically innovative, whilst initially being ideologically unacceptable ...

'' and surrealist

Surrealism is an art movement, art and cultural movement that developed in Europe in the aftermath of World War I in which artists aimed to allow the unconscious mind to express itself, often resulting in the depiction of illogical or dreamlike s ...

literary figures in their own right. Their praise and analyses, emphasizing Verne's stylistic innovations and enduring literary themes, proved highly influential for literary studies to come.

In the 1960s and 1970s, thanks in large part to a sustained wave of serious literary study from well-known French scholars and writers, Verne's reputation skyrocketed in France. Roland Barthes

Roland Gérard Barthes (; ; 12 November 1915 – 25 March 1980) was a French literary theorist, essayist, philosopher, critic, and semiotician. His work engaged in the analysis of a variety of sign systems, mainly derived from Western popu ...

' seminal essay ''Nautilus et Bateau Ivre'' (''The Nautilus

A nautilus (; ) is any of the various species within the cephalopod family Nautilidae. This is the sole extant family of the superfamily Nautilaceae and the suborder Nautilina.

It comprises nine living species in two genera, the type genus, ty ...

and the Drunken Boat

(''The Drunken Boat'') is a Symbolist poem written in the summer of 1871 by French poet Arthur Rimbaud, then aged sixteen. The poem, one-hundred lines long, with four alexandrines per each of its twenty-five quatrains, describes the drifting a ...

'') was influential in its exegesis

Exegesis ( ; from the Ancient Greek, Greek , from , "to lead out") is a critical explanation or interpretation (philosophy), interpretation of a text. The term is traditionally applied to the interpretation of Bible, Biblical works. In modern us ...

of the ''Voyages extraordinares'' as a purely literary text, while book-length studies by such figures as Marcel Moré and Jean Chesneaux considered Verne from a multitude of thematic vantage points.

French literary journals devoted entire issues to Verne and his work, with essays by such imposing literary figures as Michel Butor

Michel Butor (; 14 September 1926 – 24 August 2016) was a French poet, novelist, teacher, essayist, art critic and translator.

Life and work

Michel Marie François Butor was born in Mons-en-Barœul, a suburb of Lille, the third of seven chil ...

, Georges Borgeaud, Marcel Brion

Marcel Brion (; 21 November 1895 – 23 October 1984) was a French essayist, literary critic, novelist, and historian.

Early life

The son of a lawyer, Brion was classmates in Thiers with Marcel Pagnol and Albert Cohen. After completing his ...

, Pierre Versins, Michel Foucault

Paul-Michel Foucault ( , ; ; 15 October 192625 June 1984) was a French History of ideas, historian of ideas and Philosophy, philosopher who was also an author, Literary criticism, literary critic, Activism, political activist, and teacher. Fo ...

, René Barjavel

René Barjavel (24 January 1911 – 24 November 1985) was a French author, journalist and critic who may have been the first to think of the grandfather paradox in time travel. He was born in Nyons, a town in the Drôme department in southeas ...

, Marcel Lecomte, Francis Lacassin, and Michel Serres; meanwhile, Verne's entire published opus returned to print, with unabridged and illustrated editions of his works printed by Livre de Poche and Éditions Rencontre. The wave reached its climax in Verne's sesquicentennial year 1978, when he was made the subject of an academic colloquium at the Centre culturel international de Cerisy-la-Salle, and ''Journey to the Center of the Earth

''Journey to the Center of the Earth'' (), also translated with the variant titles ''A Journey to the Centre of the Earth'' and ''A Journey into the Interior of the Earth'', is a classic science fiction novel written by French novelist Jules Ve ...

'' was accepted for the French university system's ''agrégation'' reading list. Since these events, Verne has been consistently recognized in Europe as a legitimate member of the French literary canon, with academic studies and new publications steadily continuing.

Verne's reputation in English-speaking countries has been considerably slower in changing. Throughout the 20th century, most anglophone scholars dismissed Verne as a genre writer for children and a naïve proponent of science and technology (despite strong evidence to the contrary on both counts), thus finding him more interesting as a technological prophet or as a subject of comparison to English-language writers such as Edgar Allan Poe and H. G. Wells

Herbert George Wells (21 September 1866 – 13 August 1946) was an English writer, prolific in many genres. He wrote more than fifty novels and dozens of short stories. His non-fiction output included works of social commentary, politics, hist ...

than as a topic of literary study in his own right. This narrow view of Verne has undoubtedly been influenced by the poor-quality #English translations, English translations and very loosely adapted Cinema of the United States, Hollywood film versions through which most American and British readers have discovered Verne. However, since the mid-1980s a considerable number of serious English-language studies and translations have appeared, suggesting that a rehabilitation of Verne's anglophone reputation may currently be underway.

English translations

Translation of Verne into English began in 1852, when Verne's short story '' A Voyage in a Balloon'' (1851) was published in the American journal ''Sartain's Magazine, Sartain's Union Magazine of Literature and Art'' in a translation by Anne Toppan Wilbur Wood, Anne T. Wilbur. Translation of his novels began in 1869 with William Lackland's translation of ''

Translation of Verne into English began in 1852, when Verne's short story '' A Voyage in a Balloon'' (1851) was published in the American journal ''Sartain's Magazine, Sartain's Union Magazine of Literature and Art'' in a translation by Anne Toppan Wilbur Wood, Anne T. Wilbur. Translation of his novels began in 1869 with William Lackland's translation of ''Five Weeks in a Balloon

''Five Weeks in a Balloon, or, A Journey of Discovery by Three Englishmen in Africa'' () is an adventure novel by Jules Verne, published in 1863. It is the first novel in which he perfected the "ingredients" of his later work, skillfully mixing ...

'' (originally published in 1863), and continued steadily throughout Verne's lifetime, with publishers and hired translators often working in great haste to rush his most lucrative titles into English-language print. Unlike Hetzel, who targeted all ages with his publishing strategies for the ''Voyages extraordinaires'', the British and American publishers of Verne chose to market his books almost exclusively to young audiences; this business move had a long-lasting effect on Verne's reputation in English-speaking countries, implying that Verne could be treated purely as a children's author.

These early English-language translations have been widely criticized for their extensive textual omissions, errors, and alterations, and are not considered adequate representations of Verne's actual novels. In an essay for ''The Guardian'', British writer Adam Roberts (British writer), Adam Roberts commented: I'd always liked reading Jules Verne and I've read most of his novels; but it wasn't until recently that I really understood I hadn't been reading Jules Verne at all ... It's a bizarre situation for a world-famous writer to be in. Indeed, I can't think of a major writer who has been so poorly served by translation.Similarly, the American novelist Michael Crichton observed: Since 1965, a considerable number of more accurate English translations of Verne have appeared. However, the older, deficient translations continue to be republished due to their public domain status, and in many cases their easy availability in online sources.

Relationship with science fiction

The relationship between Verne's ''Voyages extraordinaires'' and the literary genre science fiction is a complex one. Verne, like

The relationship between Verne's ''Voyages extraordinaires'' and the literary genre science fiction is a complex one. Verne, like H. G. Wells

Herbert George Wells (21 September 1866 – 13 August 1946) was an English writer, prolific in many genres. He wrote more than fifty novels and dozens of short stories. His non-fiction output included works of social commentary, politics, hist ...

, is frequently cited as one of the founders of the genre, and his profound influence on its development is indisputable; however, many earlier writers, such as Lucian of Samosata, Voltaire, and Mary Shelley, have also been cited as creators of science fiction, an unavoidable ambiguity arising from the vague definition and History of science fiction, history of the genre.

A primary issue at the heart of the dispute is the question of whether Verne's works count as science fiction to begin with. Maurice Renard claimed that Verne "never wrote a single sentence of scientific-marvelous". Verne himself argued repeatedly in interviews that his novels were not meant to be read as scientific, saying "I have invented nothing". His own goal was rather to "depict the earth [and] at the same time to realize a very high ideal of beauty of style", as he pointed out in an example:

Closely related to Verne's science-fiction reputation is the often-repeated claim that he is a "prophet" of scientific progress, and that many of his novels involve elements of technology that were fantastic for his day but later became commonplace. These claims have a long history, especially in America, but the modern scholarly consensus is that such claims of prophecy are heavily exaggerated. In a 1961 article critical of ''Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas'' scientific accuracy, Theodore L. Thomas speculated that Verne's storytelling skill and readers' faulty memories of a book they read as children caused people to "remember things from it that are not there. The impression that the novel contains valid scientific prediction seems to grow as the years roll by". As with science fiction, Verne himself flatly denied that he was a futuristic prophet, saying that any connection between scientific developments and his work was "mere coincidence" and attributing his indisputable scientific accuracy to his extensive research: "even before I began writing stories, I always took numerous notes out of every book, newspaper, magazine, or scientific report that I came across."

Legacy

Verne's novels have had a wide influence on both literary and scientific works; writers known to have been influenced by Verne include Marcel Aymé,

Verne's novels have had a wide influence on both literary and scientific works; writers known to have been influenced by Verne include Marcel Aymé, Roland Barthes

Roland Gérard Barthes (; ; 12 November 1915 – 25 March 1980) was a French literary theorist, essayist, philosopher, critic, and semiotician. His work engaged in the analysis of a variety of sign systems, mainly derived from Western popu ...