Joseph Napoleon on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Joseph Bonaparte (born Giuseppe di Buonaparte, ; ; ; 7 January 176828 July 1844) was a French statesman, lawyer, diplomat and older brother of

Joseph's arrival in Naples was warmly greeted with cheers and he was eager to be a monarch well liked by his subjects. Seeking to win the favour of the local elites, he maintained in their posts the vast majority of those who had held office and position under the

Joseph's arrival in Naples was warmly greeted with cheers and he was eager to be a monarch well liked by his subjects. Seeking to win the favour of the local elites, he maintained in their posts the vast majority of those who had held office and position under the  Upon returning to

Upon returning to

King Joseph abdicated the Spanish throne and returned to

King Joseph abdicated the Spanish throne and returned to

Joseph Bonaparte at Point Breeze

*

at

Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

. During the Napoleonic Wars

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Napoleonic Wars

, partof = the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

, image = Napoleonic Wars (revision).jpg

, caption = Left to right, top to bottom:Battl ...

, the latter made him King of Naples

The following is a list of rulers of the Kingdom of Naples, from its first Sicilian Vespers, separation from the Kingdom of Sicily to its merger with the same into the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies.

Kingdom of Naples (1282–1501)

House of Anjou

...

(1806–1808), and then King of Spain and the Indies (1808–1813). After the fall of Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

, Joseph styled himself ''Comte de Survilliers'' and emigrated to the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

, where he settled near Bordentown, New Jersey

Bordentown is a City (New Jersey), city in Burlington County, New Jersey, Burlington County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey. As of the 2020 United States census, the city's population was 3,993, an increase of 69 (+1.8%) from the 2010 United ...

, on Pointe Breeze estate overlooking the Delaware River

The Delaware River is a major river in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States and is the longest free-flowing (undammed) river in the Eastern United States. From the meeting of its branches in Hancock, New York, the river flows for a ...

not far from Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

.

Early life and career

Joseph was born in 1768 as Giuseppe Buonaparte to Carlo Buonaparte and Maria Letizia Ramolino at Corte, the capital of theCorsican Republic

The Corsican Republic () was a short-lived state on the island of Corsica in the Mediterranean Sea. It was proclaimed in July 1755 by Pasquale Paoli, who was seeking independence from the Republic of Genoa. Paoli created the Corsican Constitutio ...

. In the year of his birth, Corsica was invaded by France and conquered the following year. His father was originally a follower of the Corsican patriot leader Pasquale Paoli

Filippo Antonio Pasquale de' Paoli (; or ; ; 6 April 1725 – 5 February 1807) was a Corsican patriot, statesman, and military leader who was at the forefront of resistance movements against the Republic of Genoa, Genoese and later Kingd ...

, but later became a supporter of French rule.

Bonaparte trained as a lawyer. In that role and as a politician and diplomat, he served in the Council of Five Hundred

The Council of Five Hundred () was the lower house of the legislature of the French First Republic under the Constitution of the Year III. It operated from 31 October 1795 to 9 November 1799 during the French Directory, Directory () period of t ...

and as the French ambassador to the Papal States

The Papal States ( ; ; ), officially the State of the Church, were a conglomeration of territories on the Italian peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope from 756 to 1870. They were among the major states of Italy from the 8th c ...

. In 1799, he used his position as member of the Council of Five Hundred to help his brother Napoleon to overthrow the Directory. On 30 September 1800, as Minister Plenipotentiary

An envoy extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary, usually known as a minister, was a diplomatic head of mission who was ranked below ambassador. A diplomatic mission headed by an envoy was known as a legation rather than an embassy. Under the ...

, he signed the Treaty of Mortefontaine, treaty of friendship and commerce between France and the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

, alongside Charles Pierre Claret de Fleurieu, and Pierre Louis Roederer.

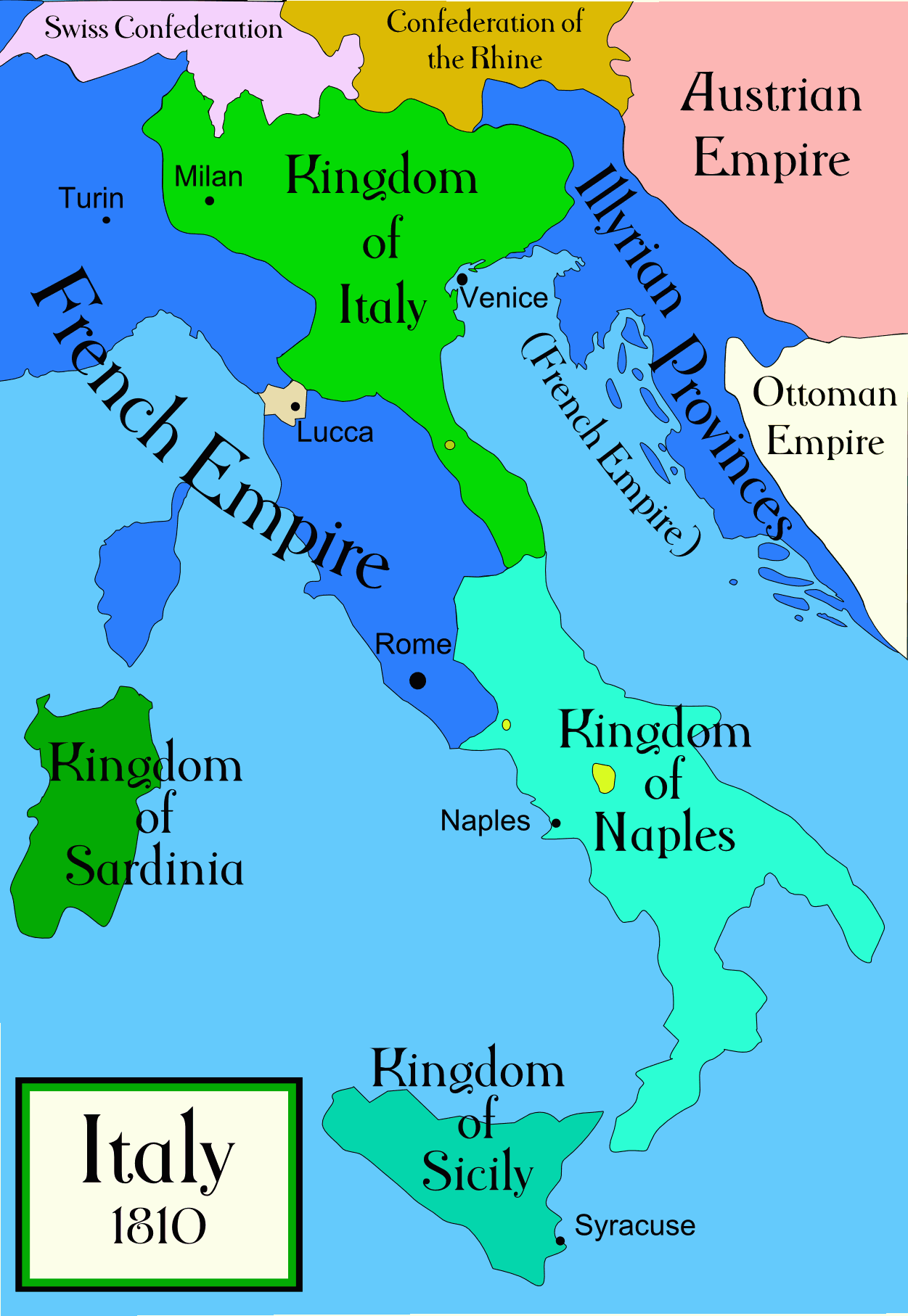

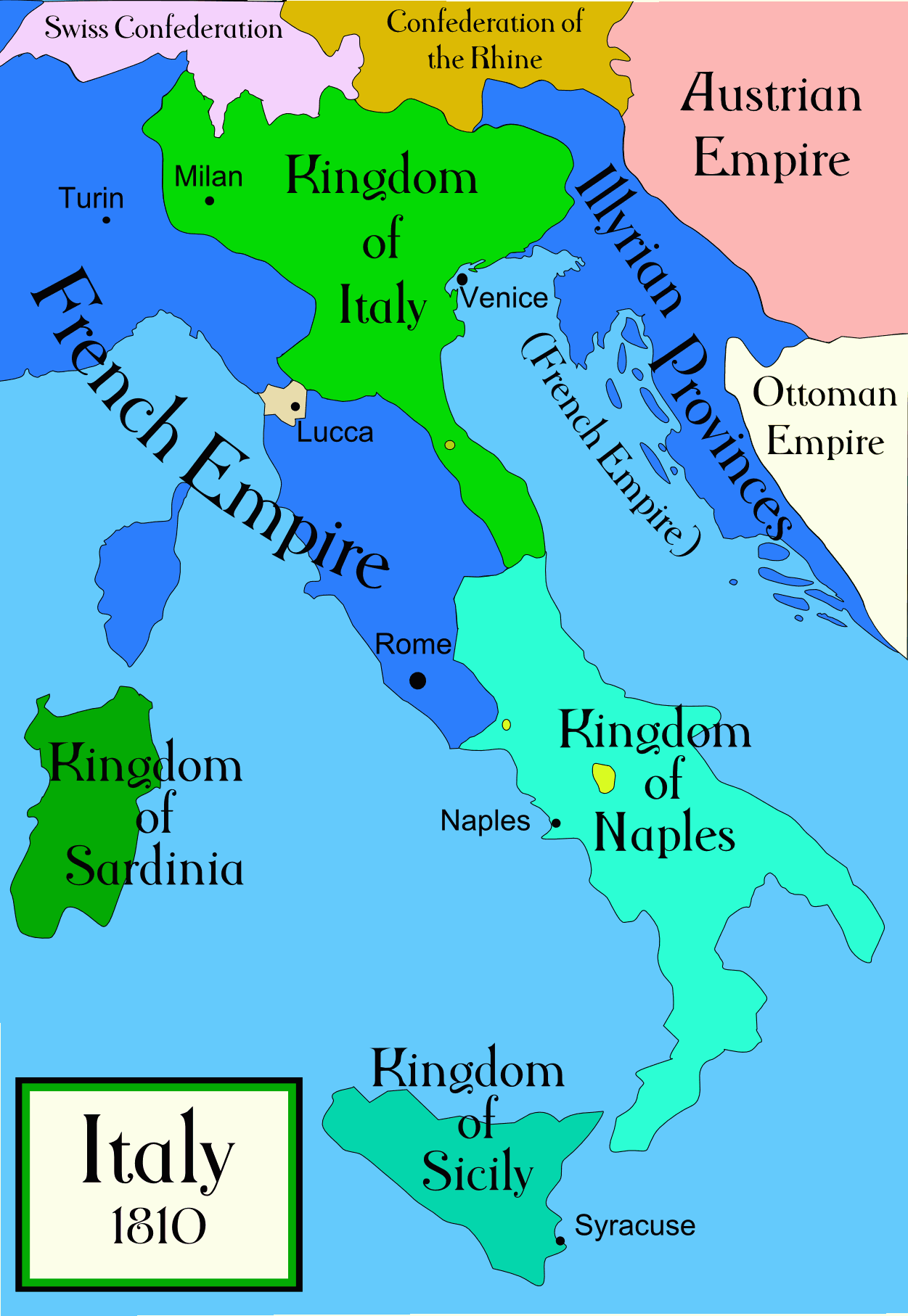

King of Naples

Upon the outbreak of war betweenFrance

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

and Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

in 1805, Ferdinand IV of Naples

Ferdinand I ( Italian: ''Ferdinando I''; 12 January 1751 – 4 January 1825) was King of the Two Sicilies from 1816 until his death. Before that he had been, since 1759, King of Naples as Ferdinand IV and King of Sicily as Ferdinand III. He was ...

had agreed to a treaty of neutrality with Napoleon I

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

but, a few days later, declared his support for Austria. He permitted a large Anglo-Russian force to land in his kingdom. Napoleon, however, was soon victorious. After the War of the Third Coalition

The War of the Third Coalition () was a European conflict lasting from 1805 to 1806 and was the first conflict of the Napoleonic Wars. During the war, First French Empire, France and French client republic, its client states under Napoleon I an ...

was shattered on 5 December at the Battle of Austerlitz

The Battle of Austerlitz (2 December 1805/11 Frimaire An XIV French Republican calendar, FRC), also known as the Battle of the Three Emperors, was one of the most important military engagements of the Napoleonic Wars. The battle occurred near t ...

, Ferdinand was subject to Napoleon's wrath.

On 27 December 1805, Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

issued a proclamation from the Schönbrunn declaring Ferdinand to have forfeited his kingdom. He said that a French invasion would soon follow to ensure that "the finest of countries is relieved from the yoke of the most faithless of men".

On 31 December Napoleon commanded Joseph Bonaparte to move to Rome, where he would be assigned to command the army sent to dispossess Ferdinand of his throne. Although Bonaparte was the nominal commander-in-chief of the expedition, Marshal Masséna was in effective command of operations, with General St. Cyr second. But, St. Cyr, who had previously held the senior command of French troops in the region, soon resigned in protest at being made subordinate to Masséna and left for Paris. An outraged Napoleon ordered St. Cyr to return to his post at once.

On 8 February 1806 the French invasion force of forty-thousand men crossed into Naples. The centre and right of the army under Masséna and General Reynier advanced south from Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

, while Giuseppe Lechi led a force down the Adriatic

The Adriatic Sea () is a body of water separating the Italian Peninsula from the Balkans, Balkan Peninsula. The Adriatic is the northernmost arm of the Mediterranean Sea, extending from the Strait of Otranto (where it connects to the Ionian Se ...

coast from Ancona

Ancona (, also ; ) is a city and a seaport in the Marche region of central Italy, with a population of around 101,997 . Ancona is the capital of the province of Ancona, homonymous province and of the region. The city is located northeast of Ro ...

. On his brother's recommendation, Bonaparte attached himself to Reynier. The French advance faced little resistance. Even before any French troops had crossed the border, the Anglo-Russian forces had beaten a prudent retreat, the British withdrawing to Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

, and the Russians to Corfu

Corfu ( , ) or Kerkyra (, ) is a Greece, Greek island in the Ionian Sea, of the Ionian Islands; including its Greek islands, small satellite islands, it forms the margin of Greece's northwestern frontier. The island is part of the Corfu (regio ...

. Abandoned by his allies, King Ferdinand had also already set sail for Palermo

Palermo ( ; ; , locally also or ) is a city in southern Italy, the capital (political), capital of both the autonomous area, autonomous region of Sicily and the Metropolitan City of Palermo, the city's surrounding metropolitan province. The ...

on 23 January. Queen Maria-Carolina lingered a little longer in the capital but, on 11 February, fled to join her husband.

The first obstacle the French encountered was the fortress of Gaeta

Gaeta (; ; Southern Latian dialect, Southern Laziale: ''Gaieta'') is a seaside resort in the province of Latina in Lazio, Italy. Set on a promontory stretching towards the Gulf of Gaeta, it is from Rome and from Naples.

The city has played ...

; its governor, Prince Louis of Hesse-Philippsthal, refused to surrender his charge. There was no meaningful delay of the invaders, as Masséna detached a small force to besiege the garrison before continuing south. Capua

Capua ( ; ) is a city and ''comune'' in the province of Caserta, in the region of Campania, southern Italy, located on the northeastern edge of the Campanian plain.

History Ancient era

The name of Capua comes from the Etruscan ''Capeva''. The ...

opened its gates after only token resistance. On 14 February Masséna took possession of Naples

Naples ( ; ; ) is the Regions of Italy, regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 908,082 within the city's administrative limits as of 2025, while its Metropolitan City of N ...

and, the following day, Bonaparte staged a triumphant entrance into the city. Reynier was quickly dispatched to seize control of the Strait of Messina

The Strait of Messina (; ) is a narrow strait between the eastern tip of Sicily (Punta del Faro) and the western tip of Calabria (Punta Pezzo) in Southern Italy. It connects the Tyrrhenian Sea to the north with the Ionian Sea to the south, with ...

and, on 9 March, inflicted a crushing defeat of the Neapolitan Royal Army at the Battle of Campo Tenese, effectively destroying it as a fighting force and securing the entire mainland for the French.

On 30 March 1806 Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

issued a decree installing Joseph Bonaparte as King of Naples and Sicily; the decree said as follows:

"Napoleon, by the Grace of God and the constitutions. Emperor of the French and King of Italy, to all those to whom these presents come, greetings. The interests of our people, the honor of our Crown, and the tranquility of the Continent of Europe requiring that we should assure, in a stable and definite manner, the lot of the people of Naples and of Sicily, who have fallen into our power by the right of conquest, and who constitute a part of the Grand Empire, we declare that we recognize, as King of Naples and of Sicily, our well-beloved brother, Joseph Napoleon, Grand Elector of France. This Crown will be hereditary, by order of primogeniture, in his descendants male, legitimate, and natural, etc."

Joseph's arrival in Naples was warmly greeted with cheers and he was eager to be a monarch well liked by his subjects. Seeking to win the favour of the local elites, he maintained in their posts the vast majority of those who had held office and position under the

Joseph's arrival in Naples was warmly greeted with cheers and he was eager to be a monarch well liked by his subjects. Seeking to win the favour of the local elites, he maintained in their posts the vast majority of those who had held office and position under the Bourbons

The House of Bourbon (, also ; ) is a dynasty that originated in the Kingdom of France as a branch of the Capetian dynasty, the royal House of France. Bourbon kings first ruled France and Navarre in the 16th century. A branch descended from ...

and was anxious to not in any way appear a foreign oppressor. With a provisional government set up in the capital, Joseph then immediately set off, accompanied by General Lamarque, on a tour of his new realm. The principal object of the tour was to assess the feasibility of an immediate invasion of Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

and the expulsion of Ferdinand

Ferdinand is a Germanic name composed of the elements "journey, travel", Proto-Germanic , abstract noun from root "to fare, travel" (PIE , "to lead, pass over"), and "courage" or "ready, prepared" related to Old High German "to risk, ventu ...

and Maria-Carolina from their refuge in Palermo

Palermo ( ; ; , locally also or ) is a city in southern Italy, the capital (political), capital of both the autonomous area, autonomous region of Sicily and the Metropolitan City of Palermo, the city's surrounding metropolitan province. The ...

. But, upon reviewing the situation at the Strait of Messina

The Strait of Messina (; ) is a narrow strait between the eastern tip of Sicily (Punta del Faro) and the western tip of Calabria (Punta Pezzo) in Southern Italy. It connects the Tyrrhenian Sea to the north with the Ionian Sea to the south, with ...

, Joseph was forced to admit the impossibility of such an enterprise, the Bourbons having carried off all boats and transports from along the coast and concentrated their remaining forces, alongside the British, on the opposite side. Unable to possess himself of Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

, Joseph was nevertheless master of the mainland and he continued his progress through Calabria

Calabria is a Regions of Italy, region in Southern Italy. It is a peninsula bordered by the region Basilicata to the north, the Ionian Sea to the east, the Strait of Messina to the southwest, which separates it from Sicily, and the Tyrrhenian S ...

and on to Lucania

Lucania was a historical region of Southern Italy, corresponding to the modern-day region of Basilicata. It was the land of the Lucani, an Oscan people. It extended from the Tyrrhenian Sea to the Gulf of Taranto. It bordered with Samnium and ...

and Apulia

Apulia ( ), also known by its Italian language, Italian name Puglia (), is a Regions of Italy, region of Italy, located in the Southern Italy, southern peninsular section of the country, bordering the Adriatic Sea to the east, the Strait of Ot ...

, visiting the main villages and meeting the local notables, clergy and people, allowing his people to grow accustomed to their new king and enabling himself to form first-hand a picture of the condition of his kingdom.

Upon returning to

Upon returning to Naples

Naples ( ; ; ) is the Regions of Italy, regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 908,082 within the city's administrative limits as of 2025, while its Metropolitan City of N ...

, Bonaparte received a deputation from the French Senate

The Senate (, ) is the upper house of the French Parliament, with the lower house being the National Assembly (France), National Assembly, the two houses constituting the legislature of France. It is made up of 348 senators (''sénateurs'' and ...

congratulating him upon his accession. The King formed a ministry staffed by many competent and talented men; he was determined to follow a reforming agenda and bring Naples the benefits of the French Revolution, without its excesses. Saliceti was appointed Minister of Police, Roederer Minister of Finance, Miot Minister of the Interior and General Dumas Minister of War. Marshal Jourdan was also confirmed as Governor of Naples, an appointment made by Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

, and served as Bonaparte's foremost military adviser.

Bonaparte embarked on an ambitious programme of reform and regeneration, in order to raise Naples to the level of a modern state in the mould of Napoleonic France. Monastic orders were suppressed, their property nationalised

Nationalization (nationalisation in British English)

is the process of transforming privately owned assets into public assets by bringing them under the public ownership of a national government or state. Nationalization contrasts with ...

, and their funds confiscated to steady the royal finances. Feudal privileges and taxes were abolished; however, the nobility was compensated by an indemnity in the form of a certificate that could be exchanged in return for lands nationalised from the Church.Biographical Sketch of Joseph Napoleon Bonaparte, Count de Survilliers, 29. Provincial intendants were instructed to engage those dispossessed former monks who were willing to work in public education, and to ensure that elderly monks no longer able to support themselves could move into communal establishments founded for their care. A college for the education of young girls was established in each province. A central college was founded at Aversa

Aversa () is a city and ''comune'' in the Province of Caserta in Campania, southern Italy, about 24 km north of Naples. It is the centre of an agricultural district, the ''Agro Aversano'', producing wine and cheese (famous for the typical dome ...

for the daughters of public functionaries, and the ablest from the provincial schools, to be admitted under the personal patronage of Queen Julie.

The practice of forcibly recruiting prisoners into the army was abolished. To suppress and control robbers in the mountains, military commissions were established with the power to judge and execute, without appeal, all those brigands arrested with arms in their possession. Public works programmes were begun to provide employment to the poor and invest in improvements to the kingdom. Highways were built to Reggio. The project of a Calabrian road was completed under Bonaparte within the year after decades of delay. In the second year of his reign, Bonaparte installed the first system of public street-lighting in Naples, modelled on that operating in Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

.

Although the kingdom was not at that time furnished with a constitution, and thus Joseph's will as monarch reigned supreme, there is yet no instance of him ever adopting a measure of policy without prior discussion of the matter in the Council of State and the passing of a majority vote in favour his course of action by the counsellors. Joseph thus presided over Naples in the best traditions of Enlightened absolutism

Enlightened absolutism, also called enlightened despotism, refers to the conduct and policies of European absolute monarchs during the 18th and early 19th centuries who were influenced by the ideas of the Enlightenment, espousing them to enhanc ...

, doubling the revenue of the crown from seven to fourteen million ducats in his brief two-year reign while all the time seeking to lighten the burdens of his people rather than increase them.

Joseph ruled Naples for two years before being replaced by his sister's husband, Joachim Murat

Joachim Murat ( , also ; ; ; 25 March 1767 – 13 October 1815) was a French Army officer and statesman who served during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. Under the French Empire he received the military titles of Marshal of the ...

. Joseph was then made King of Spain

The monarchy of Spain or Spanish monarchy () is the constitutional form of government of Spain. It consists of a Hereditary monarchy, hereditary monarch who reigns as the head of state, being the highest office of the country.

The Spanish ...

in August 1808, soon after the French invasion.

King of Spain and the Indies

Joseph somewhat reluctantly left Naples, where he was popular, and arrived in Spain, where he was extremely unpopular. Joseph came under heavy fire from his opponents in Spain, who tried to smear his reputation by calling him (Joe Bottle) for his alleged heavy drinking, an accusation echoed by later Spanish historiography, despite the fact that Joseph was abstemious. His arrival as a foreign sovereign sparked a massive Spanish revolt against French rule, and the beginning of thePeninsular War

The Peninsular War (1808–1814) was fought in the Iberian Peninsula by Kingdom of Portugal, Portugal, Spain and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom against the invading and occupying forces of the First French ...

. Thompson says the Spanish revolt was, "a reaction against new institutions and ideas, a movement for loyalty to the old order: to the hereditary crown of the Most Catholic kings, which Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

, an excommunicated enemy of the Pope, had put on the head of a Frenchman; to the Catholic Church persecuted by republicans who had desecrated churches, murdered priests, and enforced a (law of religion); and to local and provincial rights and privileges threatened by an efficiently centralized government.

Joseph temporarily retreated with much of the French Army to northern Spain. Feeling himself in an ignominious position, Joseph then proposed his own abdication from the Spanish throne, hoping that Napoleon would sanction his return to the Neapolitan Throne he had formerly occupied. Napoleon dismissed Joseph's misgivings out of hand, and to back up the raw and ill-trained levies he had initially allocated to Spain, the Emperor sent heavy French reinforcements to assist Joseph in maintaining his position as King of Spain. Despite the easy recapture of Madrid

Madrid ( ; ) is the capital and List of largest cities in Spain, most populous municipality of Spain. It has almost 3.5 million inhabitants and a Madrid metropolitan area, metropolitan area population of approximately 7 million. It i ...

, and nominal control by Joseph's government over many cities and provinces, Joseph's reign over Spain was always tenuous at best, and was plagued with near-constant conflict with pro-Bourbon guerrilla

Guerrilla warfare is a form of unconventional warfare in which small groups of irregular military, such as rebels, Partisan (military), partisans, paramilitary personnel or armed civilians, which may include Children in the military, recruite ...

s. Joseph and his supporters never established complete control over the country, and after a series of failed military campaigns, he would eventually abdicate the throne.

King Joseph's Spanish supporters were called or (frenchified). During his reign, he ended the Spanish Inquisition

The Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition () was established in 1478 by the Catholic Monarchs of Spain, Catholic Monarchs, King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella I of Castile and lasted until 1834. It began toward the end of ...

, partly because Napoleon was at odds with Pope Pius VII

Pope Pius VII (; born Barnaba Niccolò Maria Luigi Chiaramonti; 14 August 1742 – 20 August 1823) was head of the Catholic Church from 14 March 1800 to his death in August 1823. He ruled the Papal States from June 1800 to 17 May 1809 and again ...

at the time. Despite such efforts to win popularity, Joseph's foreign birth and support, plus his membership of a Masonic lodge, virtually guaranteed he would never be accepted as legitimate by the bulk of the Spanish people. During Joseph's rule of Spain, Venezuela

Venezuela, officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many Federal Dependencies of Venezuela, islands and islets in the Caribbean Sea. It com ...

declared independence from Spain. The king had virtually no influence over the course of the ongoing Peninsular War

The Peninsular War (1808–1814) was fought in the Iberian Peninsula by Kingdom of Portugal, Portugal, Spain and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom against the invading and occupying forces of the First French ...

: Joseph's nominal command of French forces in Spain was mostly illusory, as the French commanders theoretically subordinate to King Joseph insisted on checking with Napoleon before carrying out Joseph's instructions.

King Joseph abdicated the Spanish throne and returned to

King Joseph abdicated the Spanish throne and returned to France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

after the main French forces were defeated by a British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

-led coalition at the Battle of Vitoria

At the Battle of Vitoria (21 June 1813), a United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, British, Kingdom of Portugal, Portuguese and Spanish Empire, Spanish army under the Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, Marquess of Wellington bro ...

in 1813. During the closing campaign of the War of the Sixth Coalition

In the War of the Sixth Coalition () (December 1812 – May 1814), sometimes known in Germany as the Wars of Liberation (), a coalition of Austrian Empire, Austria, Kingdom of Prussia, Prussia, Russian Empire, Russia, History of Spain (1808– ...

, Napoleon I

Napoleon Bonaparte (born Napoleone di Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French general and statesman who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led Military career ...

left his brother to govern Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

with the title Lieutenant General of the Empire. As a result, he was again in nominal command of the French Imperial Army that was defeated at the Battle of Paris.

He was seen by some Bonapartists

Bonapartism () is the political ideology supervening from Napoleon Bonaparte and his followers and successors. The term was used in the narrow sense to refer to people who hoped to restore the House of Bonaparte and its style of government. In ...

as the rightful Emperor of the French

Emperor of the French ( French: ''Empereur des Français'') was the title of the monarch and supreme ruler of the First French Empire and the Second French Empire. The emperor of France was an absolute monarch.

Details

After rising to power by ...

after the death of Napoleon's own son Napoleon II

Napoleon II (Napoléon François Joseph Charles Bonaparte; 20 March 181122 July 1832) was the disputed Emperor of the French for a few weeks in 1815. He was the son of Emperor Napoleon I and Empress Marie Louise, Duchess of Parma, Marie Louise, d ...

in 1832, although he did little to advance his claim.

Later life in the United States and Europe

Bonaparte travelled to theUnited States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

onboard the ''Commerce'' under the name of M. Bouchard. British naval officers had searched the vessel three times but never found Bonaparte on board and the ship arrived on 15 July 1815. In the period 1817–1832, Bonaparte lived primarily in the United States (where he sold the jewels he had taken from Spain). He first settled in New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

and Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

, where his house became the centre of activity for French migrants. In 1823, he was elected as a member to the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS) is an American scholarly organization and learned society founded in 1743 in Philadelphia that promotes knowledge in the humanities and natural sciences through research, professional meetings, publicat ...

. Later he purchased an estate, called Point Breeze and formerly owned by Stephen Sayre. It was in Bordentown, New Jersey

Bordentown is a City (New Jersey), city in Burlington County, New Jersey, Burlington County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey. As of the 2020 United States census, the city's population was 3,993, an increase of 69 (+1.8%) from the 2010 United ...

, on the east side of the Delaware River

The Delaware River is a major river in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States and is the longest free-flowing (undammed) river in the Eastern United States. From the meeting of its branches in Hancock, New York, the river flows for a ...

. It was located near the confluence of Crosswicks Creek and the Delaware. He considerably expanded Sayre's home and created extensive gardens in the picturesque style. When his first home was destroyed by fire in January 1820 he converted his stables into a second grand house. On completion, it was generally viewed – perhaps diplomatically – as the "second-finest house in America" after the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. Located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue Northwest (Washington, D.C.), NW in Washington, D.C., it has served as the residence of every U.S. president ...

. At Point Breeze, Bonaparte entertained many of the leading intellectuals and politicians of his day.

In the summer of 1825, the Quaker scientist Reuben Haines III described Bonaparte's estate at Point Breeze, in a letter to his cousin:

I partook of royal fare on solid silver and attended by six waiters who supplied me with 9 courses of the most delicious viands, many of which I could not possibly tell what they were composed of; spending the intermediate time in Charles' private rooms looking over theAnother visitor a few years later, British writer Thomas Hamilton, described Bonaparte himself:Herbarium A herbarium (plural: herbaria) is a collection of preserved plant biological specimen, specimens and associated data used for scientific study. The specimens may be whole plants or plant parts; these will usually be in dried form mounted on a sh ...and Portfolios of the Princess, or riding with her and the Prince drawn by two Elegant Horses along the ever varying roads of the park amidst splendidRhododendron ''Rhododendron'' (; : ''rhododendra'') is a very large genus of about 1,024 species of woody plants in the Ericaceae, heath family (Ericaceae). They can be either evergreen or deciduous. Most species are native to eastern Asia and the Himalayan ...s on the margin of the artificial lake on whose smooth surface gently glided the majestic European swans. Stopping to visit the Aviary enlivened by the most beautiful English pheasants, passing by alcoves ornamented with statues and busts of Parian marble, our course enlivened by the footsteps of the tame deer and the flight of theWoodcock The woodcocks are a group of seven or eight very similar living species of sandpipers in the genus ''Scolopax''. The genus name is Latin for a snipe or woodcock, and until around 1800 was used to refer to a variety of waders. The English name ..., and when alighting stopping to admire the graceful form of two splendid Etruscan vases of Porphyry 3 ft. high & 2 in diameter presented by the Queen of Sweden oseph's sister-in-law Desiree Clary Bernadotteor ranging through the different appartments of the mansion through a suite of rooms 15 ft. in eightdecorated with the finest productions of the pencils of Coregeo ic Titian! Rubens! Vandyke! Vernet! Tenniers icand Paul Potter and a library of the most splended books I ever beheld.

Joseph Bonaparte, in person, is about the middle height, but round and corpulent. In the form of his head and features there certainly exists a resemblance to Napoleon, but in the expression of the countenance there is none. I remember, at the Pergola Theatre of Florence, discovering Louis Bonaparte from his likeness to the Emperor, which is very striking, but I am by no means confident that I should have been equally successful with Joseph. There is nothing about him indicative of high intellect. His eye is dull and heavy; his manner ungraceful and deficient in that ease and dignity which we vulgar people are apt to number among the necessary attributes of majesty. **** I am told he converses without any appearance of reserve on the circumstances of his short and troubled reign — if reign, indeed, it can be called — in Spain. He attributes more than half his misfortunes, to the jealousies and intrigues of the unruly marshals, over whom he could exercise no authority. He admits the full extent of his unpopularity, but claims credit for a sincere desire to benefit the people.Reputedly some Mexican revolutionaries offered to crown Bonaparte as

Emperor of Mexico

The Emperor of Mexico () was the head of state and head of government

of Mexico on two non-consecutive occasions during the 19th century.

With the Mexican Declaration of Independence from Spain in 1821, Mexico briefly became an independent mon ...

in 1820, but he declined. Mexico gained its independence from Spain in 1821.

In 1832, Bonaparte moved to London, returning to his estate in the United States only intermittently. In 1844, he died in Florence

Florence ( ; ) is the capital city of the Italy, Italian region of Tuscany. It is also the most populated city in Tuscany, with 362,353 inhabitants, and 989,460 in Metropolitan City of Florence, its metropolitan province as of 2025.

Florence ...

, Italy. His body was returned to France and buried in Les Invalides

The Hôtel des Invalides (; ), commonly called (; ), is a complex of buildings in the 7th arrondissement of Paris, France, containing museums and monuments, all relating to the military history of France, as well as a hospital and an old soldi ...

, in Paris.

Family

Bonaparte married Marie Julie Clary, daughter ofFrançois Clary

François Clary (24 February 1725 – 20 January 1794) was an Irish-French merchant who made a fortune in import and export business. He is an ancestor of many members of European royalty via his daughters Julie Clary, Queen of Spain and Naples, ...

and his wife, on 1 August 1794 in Cuges-les-Pins, France. They had three daughters:

* Julie Joséphine Bonaparte (Genoa

Genoa ( ; ; ) is a city in and the capital of the Italian region of Liguria, and the sixth-largest city in Italy. As of 2025, 563,947 people live within the city's administrative limits. While its metropolitan city has 818,651 inhabitan ...

, 29 February 1796 – Genoa, 6 June 1797).

* Zénaïde Laetitia Julie Bonaparte (Paris, 8 July 1801 – Naples

Naples ( ; ; ) is the Regions of Italy, regional capital of Campania and the third-largest city of Italy, after Rome and Milan, with a population of 908,082 within the city's administrative limits as of 2025, while its Metropolitan City of N ...

, 8 August 1854); married in Brussels

Brussels, officially the Brussels-Capital Region, (All text and all but one graphic show the English name as Brussels-Capital Region.) is a Communities, regions and language areas of Belgium#Regions, region of Belgium comprising #Municipalit ...

on 29 June 1822 to Charles Lucien Bonaparte

Charles Lucien Jules Laurent Bonaparte, 2nd Prince of Canino and Musignano (24 May 1803 – 29 July 1857) was a French naturalist and ornithology, ornithologist, and a nephew of Napoleon. Lucien and his wife had twelve children, including Cardinal ...

, 2nd Prince of Canino and Musignano (Paris, 24 May 1803 - Paris, 29 July 1857).

* Charlotte Napoléone Bonaparte (Paris, 31 October 1802 – Sarzana

Sarzana (, ; ) is a town, ''comune'' (municipality) and former short-lived Catholic bishopric in the Province of La Spezia, Liguria, Italy. It is east of La Spezia, on the railway to Pisa, at the point where the railway to Parma diverges to the ...

, 2 March 1839); married in Brussels on 23 July 1826 to Napoléon Louis Bonaparte (Paris, 11 October 1804 - Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

, 17 March 1831), formerly King of Holland and Grand-Duke of Berg, without issue.

He identified the two surviving daughters as his heirs.

He also fathered two children with Maria Giulia Colonna, the Countess of Atri

Atri or Attri is a Vedic sage, who is credited with composing numerous shlokas to Agni, Indra, and other Vedic deities of Hinduism. Atri is one of the Saptarishi (seven great Vedic sages) in the Hindu tradition, and the one most mentioned in ...

:

* Giulio (9 September 1807 – 1836), unmarried and without issue.

* Teresa (30 September/29 October 1808 – died in infancy).

Bonaparte had two American daughters born at Point Breeze, his estate in Bordentown, New Jersey

Bordentown is a City (New Jersey), city in Burlington County, New Jersey, Burlington County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey. As of the 2020 United States census, the city's population was 3,993, an increase of 69 (+1.8%) from the 2010 United ...

, by his mistress, Annette Savage of Philadelphia

Philadelphia ( ), colloquially referred to as Philly, is the List of municipalities in Pennsylvania, most populous city in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania and the List of United States cities by population, sixth-most populous city in the Unit ...

, Pennsylvania ("Madame de la Folie"):

* Pauline Josephann Holton (1819 - 6 December 1823).

* Caroline Charlotte Delafolie (New Jersey, 1822 - 25 December 1890); married Colonel

Colonel ( ; abbreviated as Col., Col, or COL) is a senior military Officer (armed forces), officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, a colon ...

Zebulon Howell Benton (27 January 1811 - 16 May 1893) of Jefferson County, New York, and had four daughters and three sons

Bonaparte had two more sons by Émilie (Hémart) Lacoste, wife of Félix Lacoste, founder of the Courrier des États-Unis

The ''Courrier des Etats-Unis'' was a French language newspaper published by French emigrants in New York City. It was founded in 1828 by Félix Lacoste with the help of Joseph Bonaparte (Napoleon's older brother), who was living in New Jersey ...

:

* Félix-Joseph-François Lacoste (Philadelphia, Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania, 22 March 1825 - Paris, 1859 or Neuilly, 15 February 1922), married in Metz

Metz ( , , , then ) is a city in northeast France located at the confluence of the Moselle (river), Moselle and the Seille (Moselle), Seille rivers. Metz is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Moselle (department), Moselle Departments ...

on 28 March 1857 Isabelle de Gerando (? - 1878), and had 2 sons.

* a son Lacoste (Philadelphia, Philadelphia County, Pennsylvania, 22 March 1825 - died young)

Freemasonry

Joseph Bonaparte was admitted toMarseille

Marseille (; ; see #Name, below) is a city in southern France, the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Bouches-du-Rhône and of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur Regions of France, region. Situated in the ...

's lodge ''la Parfaite Sincérité'' in 1793. He was asked by his brother Napoleon to monitor freemasonry as Grand Master of the Grand Orient of France (1804–1815).''Franc-maçonnerie et politique au siècle des lumières: Europe-Amérique'' p. 55 – article ''Le binôme franc-maçonnerie-Révolution'' – José Ferrer Benimeli (Presses Univ de Bordeaux ed., 2006) He founded the Grand Lodge National of Spain (1809). With Cambacérès, he encouraged the post-Revolution rebirth of the Freemasonry Order in France.''Essai sur l'origine et l'histoire de la franc-maçonnerie en Guadeloupe'' – Guy Monduc (G. Monduc ed., 1985)

Legacy

*Joseph Bonaparte Gulf

Joseph Bonaparte Gulf is a large body of water off the coast of the Northern Territory and Western Australia and part of the Timor Sea. It was named after Joseph Bonaparte, brother of Napoleon and King of Naples (1806–1808) and then Spain (18 ...

in the Northern Territory

The Northern Territory (abbreviated as NT; known formally as the Northern Territory of Australia and informally as the Territory) is an states and territories of Australia, Australian internal territory in the central and central-northern regi ...

of Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising mainland Australia, the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and list of islands of Australia, numerous smaller isl ...

is named after him.

* Lake Bonaparte, located in the town of Diana, New York, United States, is also named after him.

Representation in other media

* The romantic web among Joseph Bonaparte, Napoleon,Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte

Charles XIV John (; 26 January 1763 – 8 March 1844) was King of Sweden and King of Norway, Norway from 1818 until his death in 1844 and the first monarch of the Bernadotte dynasty. In Norway, he is known as Charles III John () and before he be ...

, Julie Clary

Marie Julie Clary (26 December 1771 – 7 April 1845), also known as Julie Bonaparte, was Queen of Naples, then of Spain and the Indies, as the wife of Joseph Bonaparte, who was King of Naples from January 1806 to June 1808, and later King ...

, and Désirée Clary

Bernardine Eugénie Désirée Clary (; 8 November 1777 – 17 December 1860) was Queen of Sweden and Norway from 5 February 1818 to 8 March 1844 as the wife of King Charles XIV John. Charles John was a French general and founder of the House o ...

was the subject of the novel ''Désirée'' (1951), by Annemarie Selinko.

* The novel was adapted as a film of the same name, '' Désirée'' (1954), with Cameron Mitchell as Joseph Bonaparte.

See also

*Bayonne Statute

The Bayonne Statute (),Ignacio Fernández Sarasola, Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes. Retrieved 2010-03-12. also called the Bayonne Constitution () or the Bayonne Charter (), was a constitution or a royal charter () approved in Bayonne, Fra ...

References

Further reading

* Connelly, Owen S. Jr. "Joseph Bonaparte as King of Spain" ''History Today'' (Feb 1962), Vol. 12 Issue 2, pp. 86–96. * * biography: book received the New Jersey Council for the Humanities first place book award in 2006.Notes

External links

Joseph Bonaparte at Point Breeze

*

at

Newberry Library

The Newberry Library is an independent research library, specializing in the humanities. It is located in Chicago, Illinois, and has been free and open to the public since 1887. The Newberry's mission is to foster a deeper understanding of our wo ...

{{DEFAULTSORT:Bonaparte, Joseph

1768 births

1844 deaths

19th-century Spanish monarchs

19th-century monarchs of Naples

19th century in Spain

People from Bordentown, New Jersey

People from Corte, Haute-Corse

Joseph

Joseph is a common male name, derived from the Hebrew (). "Joseph" is used, along with " Josef", mostly in English, French and partially German languages. This spelling is also found as a variant in the languages of the modern-day Nordic count ...

French people of Italian descent

Knights of Santiago

Knights of the Golden Fleece of Spain

Members of the Council of Five Hundred

Members of the Sénat conservateur

Members of the Chamber of Peers of the Hundred Days

French Roman Catholics

Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour

Joseph Bonaparte

Joseph Bonaparte (born Giuseppe di Buonaparte, ; ; ; 7 January 176828 July 1844) was a French statesman, lawyer, diplomat and older brother of Napoleon Bonaparte. During the Napoleonic Wars, the latter made him King of Naples (1806–1808), an ...

Grand Crosses of the Royal Order of Spain

Joseph Bonaparte

Joseph Bonaparte (born Giuseppe di Buonaparte, ; ; ; 7 January 176828 July 1844) was a French statesman, lawyer, diplomat and older brother of Napoleon Bonaparte. During the Napoleonic Wars, the latter made him King of Naples (1806–1808), an ...

People of the Peninsular War

French Freemasons

Bonapartist pretenders to the French throne

People of the Kingdom of Naples (Napoleonic)

French emigrants to the United States

International members of the American Philosophical Society