Josef Bryks on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Josef Bryks, MBE, (; 18 March 1916– 11 August 1957) was a

On the day that Bryks qualified as a fighter pilot, the

On the day that Bryks qualified as a fighter pilot, the

On 23 April 1941, Bryks was at last posted to a combat squadron. He spoke good English thanks to his secondary school studies in Olomouc. He was posted not to one of the RAF's Czechoslovak squadrons but to

On 23 April 1941, Bryks was at last posted to a combat squadron. He spoke good English thanks to his secondary school studies in Olomouc. He was posted not to one of the RAF's Czechoslovak squadrons but to

On 22 June, Bryks was transferred from Dulag Luft to

On 22 June, Bryks was transferred from Dulag Luft to

Because of his injuries from Gestapo interrogations, Bryks appeared before an international medical board on 6 November. The board deemed that he should be

Because of his injuries from Gestapo interrogations, Bryks appeared before an international medical board on 6 November. The board deemed that he should be

The UK Government informed Bryks that he was to be made a Member of Order of the British Empire (MBE) in recognition of his escapes as a PoW and the help he gave to other escapees. He was invited to

The UK Government informed Bryks that he was to be made a Member of Order of the British Empire (MBE) in recognition of his escapes as a PoW and the help he gave to other escapees. He was invited to

After his conviction, Bryks was held first in Pankrác, in the same prison where the Gestapo had held him in 1944. On 17 August 1949, he was transferred to Bory prison in

After his conviction, Bryks was held first in Pankrác, in the same prison where the Gestapo had held him in 1944. On 17 August 1949, he was transferred to Bory prison in  On 6 November 1950, Bryks was transferred to a prison at

On 6 November 1950, Bryks was transferred to a prison at

Bryks resumed his resistance, but his health worsened. On 11 August 1957, he suffered a massive heart attack. He died in the prison hospital at Ostrov nad Ohří. The Communist authorities notified his wife in England in a brief telephone call, in which they gave her no further details.

Bryks' remains were not released to his family. The Communists secretly cremated him. Eight years later, in 1965, they buried his ashes in a cemetery in the Motol district of Prague.

Bryks resumed his resistance, but his health worsened. On 11 August 1957, he suffered a massive heart attack. He died in the prison hospital at Ostrov nad Ohří. The Communist authorities notified his wife in England in a brief telephone call, in which they gave her no further details.

Bryks' remains were not released to his family. The Communists secretly cremated him. Eight years later, in 1965, they buried his ashes in a cemetery in the Motol district of Prague.

In 2004, Bryks was honoured with the "Award of the City of Olomouc" for "bravery and courage during the Second World War". A memorial plaque was unveiled outside 5 Hanáckého pluku, Olomouc, where Bryks was living with his wife and daughter when the StB arrested him in 1948.

In 2006, a court in Prague finally exonerated him of his false convictions.

On 28 October 2006, the

In 2004, Bryks was honoured with the "Award of the City of Olomouc" for "bravery and courage during the Second World War". A memorial plaque was unveiled outside 5 Hanáckého pluku, Olomouc, where Bryks was living with his wife and daughter when the StB arrested him in 1948.

In 2006, a court in Prague finally exonerated him of his false convictions.

On 28 October 2006, the

Bryks was awarded numerous UK and Czechoslovak honours.

UK honours:

* Member of Order of the British Empire (MBE)

*

Bryks was awarded numerous UK and Czechoslovak honours.

UK honours:

* Member of Order of the British Empire (MBE)

*

Czechoslovak

Czechoslovak may refer to:

*A demonym or adjective pertaining to Czechoslovakia (1918–93)

**First Czechoslovak Republic (1918–38)

**Second Czechoslovak Republic (1938–39)

**Third Czechoslovak Republic (1948–60)

** Fourth Czechoslovak Repu ...

cavalryman

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from ''cheval'' meaning "horse") are groups of soldiers or warriors who Horses in warfare, fight mounted on horseback. Until the 20th century, cavalry were the most mob ...

, fighter pilot

A fighter pilot or combat pilot is a Military aviation, military aviator trained to engage in air-to-air combat, Air-to-ground weaponry, air-to-ground combat and sometimes Electronic-warfare aircraft, electronic warfare while in the cockpit of ...

, prisoner of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of war for a ...

and political prisoner

A political prisoner is someone imprisoned for their political activity. The political offense is not always the official reason for the prisoner's detention.

There is no internationally recognized legal definition of the concept, although ...

.

In 1940 he escaped the German occupation of Czechoslovakia

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

and joined the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve

The Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve (RAFVR) was established in 1936 to support the preparedness of the U.K. Royal Air Force (RAF) in the event of another war. The Air Ministry intended it to form a supplement to the Royal Auxiliary Air Force ( ...

. In 1941 he was shot down over German-occupied France

The Military Administration in France (; ) was an interim occupation authority established by Nazi Germany during World War II to administer the occupied zone in areas of northern and western France. This so-called ' was established in June 19 ...

.

Bryks was a prisoner of war for four years, in which time he escaped and was recaptured three times. After his third escape he served in the Polish Home Army

The Home Army (, ; abbreviated AK) was the dominant resistance movement in German-occupied Poland during World War II. The Home Army was formed in February 1942 from the earlier Związek Walki Zbrojnej (Armed Resistance) established in the ...

in Warsaw

Warsaw, officially the Capital City of Warsaw, is the capital and List of cities and towns in Poland, largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the Vistula, River Vistula in east-central Poland. Its population is officially estimated at ...

, where he helped to get supplies to Jewish resistance fighters in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising

The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising was the 1943 act of Jewish resistance in the Warsaw Ghetto in German-occupied Poland during World War II to oppose Nazi Germany's final effort to transport the remaining ghetto population to the gas chambers of the ...

.

After his third recapture Bryks was moved to Stalag Luft III

Stalag Luft III (; literally "Main Camp, Air, III"; SL III) was a ''Luftwaffe''-run prisoner-of-war (POW) camp during the Second World War, which held captured Western Allied air force personnel.

The camp was established in March 1942 near th ...

where he helped in the Great Escape, and then to Oflag IV-C

Oflag IV-C, generally known as Colditz Castle, was a prominent German Army prisoner-of-war camp for captured Allied officers during World War II. Located in Colditz, Saxony, the camp operated within the medieval Colditz Castle, which overlooks th ...

in Colditz Castle

Colditz Castle (or ''Schloss Colditz'' in German) is a Renaissance architecture, Renaissance castle in the town of Colditz near Leipzig, Dresden and Chemnitz in the States of Germany, state of Saxony in Germany. The castle is between the towns o ...

, where he remained until it was liberated by the US Army in 1945.

In 1945 Bryks returned to Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia ( ; Czech language, Czech and , ''Česko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland beca ...

and his Czechoslovak Air Force

The Czechoslovak Air Force (''Československé letectvo'') or the Czechoslovak Army Air Force (''Československé vojenské letectvo'') was the air force branch of the Czechoslovak Army formed in October 1918. The armed forces of Czechoslovakia c ...

career. However, after the 1948 Czechoslovak coup d'état

In late February 1948, the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ), with Soviet backing, assumed undisputed control over the government of Czechoslovakia through a coup d'état. It marked the beginning of four decades of the party's rule in t ...

the Communists

Communism () is a sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology within the socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a socioeconomic order centered on common ownership of the means of production, d ...

purged Bryks and many other officers who had served in Free Czechoslovak units under French or UK command.

In 1949 the Communists sentenced Bryks to 10 years in prison and stripped him of his rank and medals. In 1950 20 years' hard labour

Penal labour is a term for various kinds of forced labour that prisoners are required to perform, typically manual labour. The work may be light or hard, depending on the context. Forms of sentence involving penal labour have included inv ...

and a heavy fine were added to his original sentence. In 1952 he was moved to a prison where he was forced to work in a uranium mine

Uranium mining is the process of extraction of uranium ore from the earth. Over 50,000 tons of uranium were produced in 2019. Kazakhstan, Canada, and Australia were the top three uranium producers, respectively, and together account for 68% of w ...

. Bryks died of a heart attack

A myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when Ischemia, blood flow decreases or stops in one of the coronary arteries of the heart, causing infarction (tissue death) to the heart muscle. The most common symptom ...

in a prison hospital in 1957.

Bryks was posthumously rehabilitated after the 1989 Velvet Revolution

The Velvet Revolution () or Gentle Revolution () was a non-violent transition of power in what was then Czechoslovakia, occurring from 17 November to 28 November 1989. Popular demonstrations against the one-party government of the Communist Pa ...

ended the Communist dictatorship.

Early life

Josef Bryks was born in 1916 in Lašťany, a village about northeast ofOlomouc

Olomouc (; ) is a city in the Czech Republic. It has about 103,000 inhabitants, making it the Statutory city (Czech Republic), sixth largest city in the country. It is the administrative centre of the Olomouc Region.

Located on the Morava (rive ...

in Moravia

Moravia ( ; ) is a historical region in the eastern Czech Republic, roughly encompassing its territory within the Danube River's drainage basin. It is one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

The medieval and early ...

. His parents František and Anna (''née'' Nesvetrová) were farmers. Bryks was the seventh of eight children, but only four survived to adulthood. Bryks studied at the Commercial Academy in Olomouc and passed his ''Matura

or its translated terms (''mature'', ''matur'', , , , , ', ) is a Latin name for the secondary school exit exam or "maturity diploma" in various European countries, including Albania, Austria, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech ...

'' (final exam of secondary education) in June 1935.

In October 1935, Bryks joined the Czechoslovak Army

The Czechoslovak Army (Czech and Slovak: ''Československá armáda'') was the name of the armed forces of Czechoslovakia. It was established in 1918 following Czechoslovakia's declaration of independence from Austria-Hungary.

History

In t ...

. He started his service in a cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from ''cheval'' meaning "horse") are groups of soldiers or warriors who Horses in warfare, fight mounted on horseback. Until the 20th century, cavalry were the most mob ...

regiment in Košice

Košice is the largest city in eastern Slovakia. It is situated on the river Hornád at the eastern reaches of the Slovak Ore Mountains, near the border with Hungary. With a population of approximately 230,000, Košice is the second-largest cit ...

. At the same time, he studied at a school for cavalry officers in Pardubice

Pardubice (; ) is a city in the Czech Republic. It has about 92,000 inhabitants. It is the capital city of the Pardubice Region and lies on the Elbe River. The historic centre is well preserved and is protected as an Cultural monument (Czech Repub ...

until July 1936. From October 1936 to August 1937, he studied at the Military Academy in Hranice, where he transferred from the cavalry to the air force

An air force in the broadest sense is the national military branch that primarily conducts aerial warfare. More specifically, it is the branch of a nation's armed services that is responsible for aerial warfare as distinct from an army aviati ...

. He was promoted to lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a Junior officer, junior commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations, as well as fire services, emergency medical services, Security agency, security services ...

and specialized as an aerial observer

Aerial may refer to:

Music

* ''Aerial'' (album), by Kate Bush, and that album's title track

* "Aerials" (song), from the album ''Toxicity'' by System of a Down

Bands

* Aerial (Canadian band)

* Aerial (Scottish band)

* Aerial (Swedish band)

...

. After his training, he was posted to the 5th Observation Squadron of the 2nd "Dr Edvard Beneš" Aviation Regiment, stationed in Prague

Prague ( ; ) is the capital and List of cities and towns in the Czech Republic, largest city of the Czech Republic and the historical capital of Bohemia. Prague, located on the Vltava River, has a population of about 1.4 million, while its P ...

. From October 1937, he trained as a pilot in Prostějov

Prostějov (; ) is a city in the Olomouc Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 43,000 inhabitants. The city is historically known for its fashion industry. The historic city centre is well preserved and is protected as an urban monument zo ...

. On 30 September 1938, he graduated and was posted to the 33rd Fighter Squadron at Olomouc, where he flew Avia B-534

The Avia B-534 is a Czechoslovak biplane fighter developed and manufactured by aviation company Avia. It was produced during the period between the First World War and the Second World War. The B-534 was perhaps one of the most well-known Czecho ...

fighter aircraft.

On the day that Bryks qualified as a fighter pilot, the

On the day that Bryks qualified as a fighter pilot, the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

and France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

signed the Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement was reached in Munich on 30 September 1938, by Nazi Germany, the United Kingdom, the French Third Republic, French Republic, and the Kingdom of Italy. The agreement provided for the Occupation of Czechoslovakia (1938–194 ...

that forced Czechoslovakia to cede the Sudetenland

The Sudetenland ( , ; Czech and ) is a German name for the northern, southern, and western areas of former Czechoslovakia which were inhabited primarily by Sudeten Germans. These German speakers had predominated in the border districts of Bohe ...

to Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

. On 15 March 1939, Germany occupied the remainder of Bohemia and Moravia, and the resulting Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia

The Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia was a partially-annexation, annexed territory of Nazi Germany that was established on 16 March 1939 after the Occupation of Czechoslovakia (1938–1945), German occupation of the Czech lands. The protector ...

was forced to dissolve its army and air force.

In the meantime, Bryks' girlfriend, Marie Černá, became pregnant. On 18 April 1939, Bryks and Černá got married and her father, a butcher, gave Bryks a job as his assistant. The baby, a daughter, died two days after being born. Until the German invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland, also known as the September Campaign, Polish Campaign, and Polish Defensive War of 1939 (1 September – 6 October 1939), was a joint attack on the Second Polish Republic, Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany, the Slovak R ...

, Bryks secretly helped Czechoslovak pilots to escape to Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It extends from the Baltic Sea in the north to the Sudetes and Carpathian Mountains in the south, bordered by Lithuania and Russia to the northeast, Belarus and Ukrai ...

. In December 1939, Bryks got a job as a civil servant

The civil service is a collective term for a sector of government composed mainly of career civil service personnel hired rather than elected, whose institutional tenure typically survives transitions of political leadership. A civil service offic ...

at the Ministry of the Interior, but after three days he resigned.

Second World War

Escape from the Reich Protectorate

On 20 January 1940, Bryks escaped from Bohemia and Moravia. He passed illegally throughSlovakia

Slovakia, officially the Slovak Republic, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. It is bordered by Poland to the north, Ukraine to the east, Hungary to the south, Austria to the west, and the Czech Republic to the northwest. Slovakia's m ...

and into Hungary

Hungary is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning much of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Croatia and ...

. He was arrested in Hungary on 26 January and held in jail in Budapest

Budapest is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns of Hungary, most populous city of Hungary. It is the List of cities in the European Union by population within city limits, tenth-largest city in the European Union by popul ...

until 4 April, when he was extradited

In an extradition, one jurisdiction delivers a person accused or convicted of committing a crime in another jurisdiction, into the custody of the other's law enforcement. It is a cooperative law enforcement procedure between the two jurisdic ...

to Slovakia. He escaped, traveled through Hungary again, reached Yugoslavia

, common_name = Yugoslavia

, life_span = 1918–19921941–1945: World War II in Yugoslavia#Axis invasion and dismemberment of Yugoslavia, Axis occupation

, p1 = Kingdom of SerbiaSerbia

, flag_p ...

, and on 17 April 1940 he reported to the French Consulate in Belgrade

Belgrade is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Serbia, largest city of Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers and at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin, Pannonian Plain and the Balkan Peninsula. T ...

.

From there, Bryks travelled through Greece

Greece, officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. Located on the southern tip of the Balkan peninsula, it shares land borders with Albania to the northwest, North Macedonia and Bulgaria to the north, and Turkey to th ...

and Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

to French-ruled Syria, where he embarked on a ship to France. The ship reached France on 10 May, the day Germany launched its invasion of France

France has been invaded on numerous occasions, by foreign powers or rival French governments; there have also been unimplemented invasion plans.

* The 978 German invasion during the Franco-German war of 978–980

* The 1230 English invasion of ...

, the Netherlands

, Terminology of the Low Countries, informally Holland, is a country in Northwestern Europe, with Caribbean Netherlands, overseas territories in the Caribbean. It is the largest of the four constituent countries of the Kingdom of the Nether ...

and Belgium

Belgium, officially the Kingdom of Belgium, is a country in Northwestern Europe. Situated in a coastal lowland region known as the Low Countries, it is bordered by the Netherlands to the north, Germany to the east, Luxembourg to the southeas ...

. Bryks and other Czechoslovak Air Force personnel were sent to Agde

Agde (; ) is a commune in the southern French department of Hérault. It is the Mediterranean port of the Canal du Midi. It is situated on an ancient basalt volcano, hence the name "Black Pearl of the Mediterranée".

Location

Agde is locate ...

on the coast of Languedoc

The Province of Languedoc (, , ; ) is a former province of France.

Most of its territory is now contained in the modern-day region of Occitanie in Southern France. Its capital city was Toulouse. It had an area of approximately .

History

...

. The Armée de l'air

The French Air and Space Force (, , ) is the air force, air and space force of the French Armed Forces. Formed in 1909 as the ("Aeronautical Service"), a service arm of the French Army, it became an independent military branch in 1934 as the Fr ...

was fully occupied resisting the German advance and repeatedly having to retreat to different airfields. It had neither the instructors, equipment nor time to retrain the Czechoslovaks to operate French aircraft. On 22 June, France surrendered, and on 27 June, Bryks was evacuated by ship.

Royal Air Force (1940–41)

Bryks reachedBritain

Britain most often refers to:

* Great Britain, a large island comprising the countries of England, Scotland and Wales

* The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, a sovereign state in Europe comprising Great Britain and the north-eas ...

, where he was commissioned into the RAF Volunteer Reserve as a pilot officer

Pilot officer (Plt Off or P/O) is a junior officer rank used by some air forces, with origins from the Royal Air Force. The rank is used by air forces of many countries that have historical British influence.

Pilot officer is the lowest ran ...

. He was retrained at RAF Cosford

Royal Air Force Cosford or RAF Cosford (formerly DCAE Cosford) is a Royal Air Force station near to the village of Cosford, Shropshire, England just to the northwest of Wolverhampton and next to Albrighton.

It is a training station, home to ...

in Shropshire

Shropshire (; abbreviated SalopAlso used officially as the name of the county from 1974–1980. The demonym for inhabitants of the county "Salopian" derives from this name.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the West M ...

, where he learnt to fly the Hawker Hurricane

The Hawker Hurricane is a British single-seat fighter aircraft of the 1930s–40s which was designed and predominantly built by Hawker Aircraft Ltd. for service with the Royal Air Force (RAF). It was overshadowed in the public consciousness by ...

. On 4 August he was posted to the recently formed No. 310 Squadron RAF, which was the RAF's first squadron formed of exiled Czechoslovak personnel. However, on 17 August he was posted for further fighter training with No. 6 Operational Training Unit at RAF Sutton Bridge

Royal Air Force Sutton Bridge or more simply RAF Sutton Bridge is a former Royal Air Force List of former Royal Air Force stations, station found next to the village of Sutton Bridge in the south-east of Lincolnshire. The airfield was to the sou ...

in Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire (), abbreviated ''Lincs'', is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the East Midlands and Yorkshire and the Humber regions of England. It is bordered by the East Riding of Yorkshire across the Humber estuary to th ...

.

Then on 1 October Bryks was posted to No. 12 Operational Training Unit at RAF Benson

Royal Air Force Benson or RAF Benson is a Royal Air Force (RAF) List of Royal Air Force stations, station located at Benson, Oxfordshire, Benson, near Wallingford, Oxfordshire, Wallingford, in South Oxfordshire, England. It is a front-line st ...

in Oxfordshire

Oxfordshire ( ; abbreviated ''Oxon'') is a ceremonial county in South East England. The county is bordered by Northamptonshire and Warwickshire to the north, Buckinghamshire to the east, Berkshire to the south, and Wiltshire and Glouceste ...

, which taught light bomber

A light bomber is a relatively small and fast type of military bomber aircraft that was primarily employed before the 1950s. Such aircraft would typically not carry more than one ton of ordnance.

The earliest light bombers were intended to dr ...

aircrew. On 11 November, he was posted to the Headquarters Ferry Pool at RAF Kemble

Cotswold Airport (formerly Kemble Airfield) is a private general aviation airport, near the village of Kemble in Gloucestershire, England. Located southwest of Cirencester, it was built as a Royal Air Force (RAF) station and was known as RAF ...

in Gloucestershire

Gloucestershire ( , ; abbreviated Glos.) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by Herefordshire to the north-west, Worcestershire to the north, Warwickshire to the north-east, Oxfordshire ...

, which worked with the non-combatant Air Transport Auxiliary

The Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA) was a British civilian organisation set up at the start of the Second World War with headquarters at White Waltham Airfield in Berkshire. The ATA ferried new, repaired and damaged military aircraft between fac ...

. On 1 January 1941, he was transferred to No. 6 Maintenance Unit at RAF Brize Norton

Royal Air Force Brize Norton or RAF Brize Norton is the largest List of Royal Air Force stations, station of the Royal Air Force. Situated in Oxfordshire, about west north-west of London, it is close to the village of Brize Norton and the tow ...

in Oxfordshire as a test pilot.

Hurricane pilot with 242 Squadron

On 23 April 1941, Bryks was at last posted to a combat squadron. He spoke good English thanks to his secondary school studies in Olomouc. He was posted not to one of the RAF's Czechoslovak squadrons but to

On 23 April 1941, Bryks was at last posted to a combat squadron. He spoke good English thanks to his secondary school studies in Olomouc. He was posted not to one of the RAF's Czechoslovak squadrons but to No. 242 Squadron RAF

No. 242 Squadron RAF was a Royal Air Force (RAF) squadron. It flew in many roles during the First World War, Second World War and Cold War.

During the Second World War, the squadron was notable for (firstly) having many pilots who were either ...

, which was commanded by Douglas Bader

Group Captain Sir Douglas Robert Steuart Bader, (; 21 February 1910 – 5 September 1982) was a Royal Air Force flying ace during the Second World War. He was credited with 22 aerial victories, four shared victories, six probables, one shared ...

and had a large Canadian

Canadians () are people identified with the country of Canada. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Canadians, many (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of their being ''C ...

contingent. At the time, it flew Hurricane Mk IIb aircraft as night fighter

A night fighter (later known as all-weather fighter or all-weather interceptor post-Second World War) is a largely historical term for a fighter aircraft, fighter or interceptor aircraft adapted or designed for effective use at night, during pe ...

s, so Bryks was trained in night flying and navigation.

When Bryks joined 242 Squadron, it was based at RAF Stapleford Tawney Stapleford may refer to:

Places England

*Stapleford, Cambridgeshire

* Stapleford, Hampshire

*Stapleford, Hertfordshire

*Stapleford, Leicestershire

**Stapleford Miniature Railway

*Stapleford, Lincolnshire

*Stapleford, Nottinghamshire

**Stapleford R ...

in Essex

Essex ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the East of England, and one of the home counties. It is bordered by Cambridgeshire and Suffolk to the north, the North Sea to the east, Kent across the Thames Estuary to the ...

. While he was with the squadron it was transferred to RAF North Weald

North Weald Airfield is an operational general aviation aerodrome, in the civil parish of North Weald Bassett in Epping Forest (district), Epping Forest, Essex, England. It was an important fighter station during the Battle of Britain, when it ...

, also in Essex. Bryks became friends with a WAAF, Gertrude "Trudie" Dellar, who was the widow of an RAF pilot.

242 Squadron's rôle was changed to Circus offensive

Circus was the codename given to operations by the Royal Air Force (RAF) during the Second World War where bombers, with a mass escort of fighters, were sent over continental Europe to bring fighters into combat. These were usually formations o ...

s over German-occupied Europe

German-occupied Europe, or Nazi-occupied Europe, refers to the sovereign countries of Europe which were wholly or partly military occupation, militarily occupied and civil-occupied, including puppet states, by the (armed forces) and the governmen ...

, escorting RAF bombers with the purpose of enticing ''Luftwaffe

The Luftwaffe () was the aerial warfare, aerial-warfare branch of the before and during World War II. German Empire, Germany's military air arms during World War I, the of the Imperial German Army, Imperial Army and the of the Imperial Ge ...

'' fighter attacks. On 17 June 1941, the squadron took part in Circus 14. This was a late afternoon attack on Lille

Lille (, ; ; ; ; ) is a city in the northern part of France, within French Flanders. Positioned along the Deûle river, near France's border with Belgium, it is the capital of the Hauts-de-France Regions of France, region, the Prefectures in F ...

in northern France by 23 Bristol Blenheim

The Bristol Blenheim is a British light bomber designed and built by the Bristol Aeroplane Company, which was used extensively in the first two years of the Second World War, with examples still being used as trainers until the end of the war. ...

bombers of 18, 105 105 may refer to:

*105 (number), the number

* AD 105, a year in the 2nd century AD

* 105 BC, a year in the 2nd century BC

* 105 (telephone number), the emergency telephone number in Mongolia

* 105 (MBTA bus), a Massachusetts Bay Transport Authority ...

and 110 Squadrons, escorted by 19 Hurricanes and Supermarine Spitfire

The Supermarine Spitfire is a British single-seat fighter aircraft that was used by the Royal Air Force and other Allies of World War II, Allied countries before, during, and after World War II. It was the only British fighter produced conti ...

s. A large force of Messerschmitt Bf 109

The Messerschmitt Bf 109 is a monoplane fighter aircraft that was designed and initially produced by the Nazi Germany, German aircraft manufacturer Messerschmitt#History, Bayerische Flugzeugwerke (BFW). Together with the Focke-Wulf Fw 190, the ...

fighters from I, II and III/Jagdgeschwader 26

''Jagdgeschwader'' 26 (JG 26) ''Schlageter'' was a German fighter-wing of World War II. It was named after Albert Leo Schlageter, a World War I veteran, Freikorps member, and posthumous Nazi martyr, arrested and executed by the French fo ...

, led by flying ace

A flying ace, fighter ace or air ace is a military aviation, military aviator credited with shooting down a certain minimum number of enemy aircraft during aerial combat; the exact number of aerial victories required to officially qualify as an ...

Lieutenant Colonel Adolf Galland

Adolf Josef Ferdinand Galland (19 March 1912 – 9 February 1996) was a German Luftwaffe general and flying ace who served throughout the Second World War in Europe. He flew 705 combat missions and fought on the Western Front and in the Defenc ...

, plus Bf 109s from III/Jagdgeschwader 2

Jagdgeschwader 2 (JG 2) "Richthofen" was a German fighter Wing (military aviation unit), wing during World War II. JG 2 operated the Messerschmitt Bf 109 and Focke-Wulf Fw 190 single-seat, single-engine interceptor aircraft.

Named afte ...

, attacked the formation, shooting down 13 of the 40 RAF aircraft.

The RAF raiders managed to shoot down only three Bf 109s. One of these was downed by Bryks, but then three Bf 109s attacked his Hurricane, hitting its fuel tank and setting it afire. Bryks suffered burns to his face and ankle, and his cockpit filled with smoke. He bailed out at an altitude of , about west of Saint-Omer-en-Chaussée

Saint-Omer-en-Chaussée () is a commune in the Oise department in northern France. Saint-Omer-en-Chaussée station has rail connections to Beauvais and Le Tréport.

See also

* Communes of the Oise department

The following is a list of the ...

, losing one of his flying boots as he did so.

Prisoner of war (1941–45)

Bryks landed safely and started to bury his parachute. Frenchmen who had seen him descend gave him a civilian coat to hide his RAF uniform and told him to go to asafe house

A safe house (also spelled safehouse) is a dwelling place or building whose unassuming appearance makes it an inconspicuous location where one can hide out, take shelter, or conduct clandestine activities.

Historical usage

It may also refer to ...

in a nearby hamlet. Bryks hid in a barn until nightfall, then went to the hamlet, where he asked at a house for a doctor to treat his burns. The occupants betrayed him by calling the Germans, but when Bryks heard their motorised patrol coming, he fled the house and hid in a garden. The patrol caught him, beat him up and took him to St Omer.

The Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia was subject to Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany, officially known as the German Reich and later the Greater German Reich, was the German Reich, German state between 1933 and 1945, when Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party controlled the country, transforming it into a Totalit ...

, whose authorities deemed anyone from the protectorate who served in Allied

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not an explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are calle ...

forces to be a traitor

Treason is the crime of attacking a state (polity), state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to Coup d'état, overthrow its government, spy ...

. He could therefore be executed, and his family would suffer reprisals. Therefore, Bryks assumed the identity of "Joseph Ricks", born in 1918 in Cirencester

Cirencester ( , ; see #Pronunciation, below for more variations) is a market town and civil parish in the Cotswold District of Gloucestershire, England. Cirencester lies on the River Churn, a tributary of the River Thames. It is the List of ...

, a Gloucestershire market town

A market town is a settlement most common in Europe that obtained by custom or royal charter, in the Middle Ages, a market right, which allowed it to host a regular market; this distinguished it from a village or city. In Britain, small rura ...

about from where he had been spent two months at RAF Kemble.

When he was shot down, Bryks was wearing the Mae West lifejacket of a Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Polish people, people from Poland or of Polish descent

* Polish chicken

* Polish brothers (Mark Polish and Michael Polish, born 1970), American twin ...

colleague from 242 Squadron, F/O Henry Skalsky. Therefore, the Germans who questioned him at St Omer suspected he was Polish, and sent him to Dulag Luft at Oberursel

Oberursel (Taunus) (, , in contrast to " Lower Ursel") is a town in Germany and part of the Frankfurt Rhein-Main urban area. It is located to the north west of Frankfurt, in the Hochtaunuskreis county. It is the 13th largest town in Hesse. In ...

in Hesse

Hesse or Hessen ( ), officially the State of Hesse (), is a States of Germany, state in Germany. Its capital city is Wiesbaden, and the largest urban area is Frankfurt, which is also the country's principal financial centre. Two other major hist ...

for interrogation by a Polish-speaking German officer. There he was accused of shooting a ''Luftwaffe'' fighter pilot who was parachuting from his Bf 109 in the air battle near St Omer on 17 June. For this, he was threatened with being court-martial

A court-martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of members of the arme ...

led in Berlin

Berlin ( ; ) is the Capital of Germany, capital and largest city of Germany, by both area and List of cities in Germany by population, population. With 3.7 million inhabitants, it has the List of cities in the European Union by population withi ...

. After the war, no such shooting was found in German records for that day. The accusation seems to have been a false one to put pressure on Bryks.

On 22 June, Bryks was transferred from Dulag Luft to

On 22 June, Bryks was transferred from Dulag Luft to Oflag IX-A/H

Oflag IX-A was a World War II German prisoner-of-war camp located in Spangenberg Castle in the small town of Spangenberg in northeastern Hesse, Germany.

Camp history

The camp was opened in October 1939 as Oflag IX-AMattiello (1986), p.206 to hou ...

in Spangenberg

Spangenberg is a small town in northeastern Hesse, Germany.

Geography

Spangenberg lies in the Schwalm-Eder district some southeast of Kassel, west of the Stölzinger Gebirge, a low mountain range. Spangenberg is the demographic centrepoint of ...

castle in Hesse-Nassau

The Province of Hesse-Nassau () was a Provinces of Prussia, province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1868 to 1918, then a province of the Free State of Prussia until 1944.

Hesse-Nassau was created as a consequence of the Austro-Prussian War of ...

. Here he advised the Senior British Officer (SBO), Major General Victor Fortune

Major General Sir Victor Morven Fortune (21 August 1883 – 2 January 1949) was a senior officer of the British Army. He saw service in both World War I and World War II. He commanded the 51st (Highland) Infantry Division during the Battle ...

, of his true identity. Fortune knew the threat to Czechoslovak pilots in captivity and supported Bryks' assumed identity. And via the Red Cross

The organized International Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement is a Humanitarianism, humanitarian movement with approximately 16million volunteering, volunteers, members, and staff worldwide. It was founded to protect human life and health, to ...

, Bryks, posing as "Joseph Ricks", started writing to Gertrude Dellar.

Escape from Oflag VI-B

On 8 October 1941, Bryks was transferred toOflag VI-B

Oflag VI-B was a World War II German prisoner-of-war camp for officers (''Offizierlager''), southwest of the village of Dössel (now part of Warburg) in Germany. It held French, British, Polish and other Allied officers.

Camp history

In 1939, ...

at Dössel

Dössel is a village and constituent community ''(stadtteil)'' of the town of Warburg, in the district of Höxter in the east of the federal state of North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. Dössel has historically been known by the names of Dosele and ...

in Westphalia

Westphalia (; ; ) is a region of northwestern Germany and one of the three historic parts of the state of North Rhine-Westphalia. It has an area of and 7.9 million inhabitants.

The territory of the region is almost identical with the h ...

. There again he advised the SBO of his true identity. The PoWs' Escape Committee authorised a team of four men, including Bryks, to dig a escape tunnel through frozen clay. On the night of 19/20 April 1942, three Poles and three Czechoslovaks escaped through the tunnel in pairs. Bryks was one of them, paired with a fellow Czechoslovak, Flight Lieutenant Otakar Černý.

Bryks and Černý aimed to reach Switzerland

Switzerland, officially the Swiss Confederation, is a landlocked country located in west-central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the south, France to the west, Germany to the north, and Austria and Liechtenstein to the east. Switzerland ...

. Around midnight on 28 April, Černý was recaptured near Marburg

Marburg (; ) is a college town, university town in the States of Germany, German federal state () of Hesse, capital of the Marburg-Biedenkopf Districts of Germany, district (). The town area spreads along the valley of the river Lahn and has ...

in Hesse-Nassau. Near Giessen

Giessen, spelled in German (), is a town in the Germany, German States of Germany, state () of Hesse, capital of both the Giessen (district), district of Giessen and the Giessen (region), administrative region of Giessen. The population is appro ...

in Hesse-Darmstadt

The Landgraviate of Hesse-Darmstadt () was a State of the Holy Roman Empire, ruled by a younger branch of the House of Hesse. It was formed in 1567 following the division of the Landgraviate of Hesse among the four sons of Landgrave Philip I. ...

, Bryks stole a bicycle. He passed Offenbach am Main

Offenbach am Main () is a List of cities and towns in Germany, city in Hesse, Germany, on the left bank of the river Main (river), Main. It borders Frankfurt and is part of the Frankfurt urban area and the larger Frankfurt Rhein-Main Regional Aut ...

. A German guard shot at him as he crossed a bridge near Stuttgart

Stuttgart (; ; Swabian German, Swabian: ; Alemannic German, Alemannic: ; Italian language, Italian: ; ) is the capital city, capital and List of cities in Baden-Württemberg by population, largest city of the States of Germany, German state of ...

in Württemberg

Württemberg ( ; ) is a historical German territory roughly corresponding to the cultural and linguistic region of Swabia. The main town of the region is Stuttgart.

Together with Baden and Province of Hohenzollern, Hohenzollern, two other histo ...

. After this, short of food and water, Bryks fell ill with dysentery

Dysentery ( , ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications may include dehyd ...

. He hid in a wood near Eberbach in Baden

Baden (; ) is a historical territory in southern Germany. In earlier times it was considered to be on both sides of the Upper Rhine, but since the Napoleonic Wars, it has been considered only East of the Rhine.

History

The margraves of Ba ...

. There, on 31 April, a group of Hitler Youth

The Hitler Youth ( , often abbreviated as HJ, ) was the youth wing of the German Nazi Party. Its origins date back to 1922 and it received the name ("Hitler Youth, League of German Worker Youth") in July 1926. From 1936 until 1945, it was th ...

captured him.

Bryks had been on the run for 11 days and had travelled south from Dössel before being caught. On 5 May 1942, he was taken to Darmstadt

Darmstadt () is a city in the States of Germany, state of Hesse in Germany, located in the southern part of the Frankfurt Rhine Main Area, Rhine-Main-Area (Frankfurt Metropolitan Region). Darmstadt has around 160,000 inhabitants, making it the ...

and held by the Gestapo

The (, ), Syllabic abbreviation, abbreviated Gestapo (), was the official secret police of Nazi Germany and in German-occupied Europe.

The force was created by Hermann Göring in 1933 by combining the various political police agencies of F ...

. He was returned to Oflag VI-B at Dössel, where he was treated in the camp's infirmary from 8 May to 10 June.

Escape from Oflag VI-A

By 20 July 1942, Bryks had been transferred to Oflag VI-A near Soest in Westphalia. He was held insolitary confinement

Solitary confinement (also shortened to solitary) is a form of imprisonment in which an incarcerated person lives in a single Prison cell, cell with little or no contact with other people. It is a punitive tool used within the prison system to ...

from 12 August, but fellow prisoners smuggled razor blades to him hidden inside bread. With these, he cut a hole in the wooden floor of his cell and tunnelled to the German quarters. On 17 August he escaped through the tunnel, wearing only pyjamas, a sweater and a blanket.

Again Bryks headed south. About south of Frankfurt

Frankfurt am Main () is the most populous city in the States of Germany, German state of Hesse. Its 773,068 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the List of cities in Germany by population, fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located in the forela ...

, he found a ''Luftwaffe'' airfield where Bf 109 night fighters were based. He planned to steal one and fly to Britain, until a patrol with guard dogs approached. He fled and waded along a river to put the dogs off the scent. He reached Mannheim

Mannheim (; Palatine German language, Palatine German: or ), officially the University City of Mannheim (), is the List of cities in Baden-Württemberg by population, second-largest city in Baden-Württemberg after Stuttgart, the States of Ger ...

in Baden, where on the night of 8 September he was captured by German air defence troops, who handed him to the local Gestapo. He had been on the run for 22 days and once again had travelled south before being caught.

Bryks was returned to Oflag VI-B, but soon afterwards he and other RAF PoWs were transferred to Oflag XXI-B

Oflag XXI-B and Stalag XXI-B were World War II German prisoner-of-war camps for officers and enlisted men, located at Szubin a few miles southwest of Bydgoszcz, Poland, which at that time was occupied by Nazi Germany.

Timeline

* September ...

at Szubin

Szubin () is a town in Nakło County, Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship, Poland, located southwest of Bydgoszcz. It has a population of around 9,333 (as of 2010). It is located on the Gąsawka River in the ethnocultural region of Pałuki.

A small ...

in German-occupied Poland German-occupied Poland can refer to:

* General Government

* Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany

* Occupation of Poland (1939–1945)

* Prussian Partition

The Prussian Partition (), or Prussian Poland, is the former territories of the Polish� ...

. There he told the SBO, Wing Commander

Wing commander (Wg Cdr or W/C) is a senior officer rank used by some air forces, with origins from the Royal Air Force. The rank is used by air forces of many countries that have historical British influence.

Wing commander is immediately se ...

Harry Day

Harry Melville Arbuthnot Day, (3 August 1898 – 11 March 1977) was a Royal Marine and later a Royal Air Force pilot during the Second World War. As a prisoner of war, he was senior British officer in a number of camps and a noted escapee.

...

, of his true identity.

Escape from Oflag XXI-B

On 4 March 1943, Polish workers in the camp helped Bryks and a British officer, Squadron Leader Morris, to escape. The pair hid in a sewage tank that was mounted on a cart to empty the camp's latrines, wearing masks to try to protect them from the sewage. Members of the secret ''Armia Krajowa'' ("Home Army

The Home Army (, ; abbreviated AK) was the dominant resistance movement in German-occupied Poland during World War II. The Home Army was formed in February 1942 from the earlier Związek Walki Zbrojnej (Armed Resistance) established in the ...

" or AK) hid them in a farmhouse. There they met Flight Lieutenant Černý, who had escaped via a tunnel the night before. Their plan was to travel via Warsaw

Warsaw, officially the Capital City of Warsaw, is the capital and List of cities and towns in Poland, largest city of Poland. The metropolis stands on the Vistula, River Vistula in east-central Poland. Its population is officially estimated at ...

to Danzig, and there board a ship to neutral Sweden

Sweden had a policy of neutrality in armed conflicts from the early 19th century, until 2009, when it entered into various mutual defence treaties with the European Union (EU), and other Nordic countries.

.

Morris fell ill, but Bryks and Černý set off on foot. In three weeks, they covered the to Warsaw, where on 6 April they reported to an address that the AK had given them. Bryks assumed a Polish identity, calling himself "Josef Brdnisz". He and Černý spent four weeks in Warsaw disguised as a pair of stove fitters and chimney sweeps. They drove a horse and cart around Warsaw, supplying arms to resistance groups and bringing in food from the countryside.

On 19 April, Jewish resistance groups launched the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising

The Warsaw Ghetto Uprising was the 1943 act of Jewish resistance in the Warsaw Ghetto in German-occupied Poland during World War II to oppose Nazi Germany's final effort to transport the remaining ghetto population to the gas chambers of the ...

. Bryks and Černý helped to smuggle weapons and food to the rebels. The Germans crushed the ghetto uprising on 16 May.

A fortnight later, Bryks and Černý were lodging with a Polish widow, Mrs Błaszkiewiczowá, who had two young children and lived in a village several kilometres outside Warsaw. A collaborator told the German authorities, so on 2 June 1943 the Gestapo surrounded Mrs Błaszkiewiczowá's house and arrested everyone inside. They took Bryks, Černý and Mrs Błaszkiewiczowá to Pawiak

Pawiak () was a prison built in 1835 in Warsaw, Congress Poland.

During the January 1863 Uprising, it served as a transfer camp for Poles sentenced by Imperial Russia to deportation to Siberia.

During the World War II German occupation ...

prison, and hanged Mrs Błaszkiewiczowá for helping enemy pilots.

Bryks and Černý were interrogated, beaten and threatened with execution. On 5 June, a ''Scharführer

''Scharführer'' (, ) was a title or rank used in early 20th century German military terminology. In German, ''Schar'' was one term for the smallest sub-unit, equivalent to (for example) a "troop", "squad", or " section". The word ''führer'' ...

'' called Grunnem kicked Bryks in the stomach, beat him about the head and left him unconscious. The Gestapo held him for 63 days. He suffered ruptured intestines and a punctured eardrum. Bryks was sentenced to death for helping the AK, but the sentence was commuted.

Bryks was then sent to Stalag Luft III

Stalag Luft III (; literally "Main Camp, Air, III"; SL III) was a ''Luftwaffe''-run prisoner-of-war (POW) camp during the Second World War, which held captured Western Allied air force personnel.

The camp was established in March 1942 near th ...

, near Sagan in Lower Silesia

Lower Silesia ( ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ) is a historical and geographical region mostly located in Poland with small portions in the Czech Republic and Germany. It is the western part of the region of Silesia. Its largest city is Wrocław.

The first ...

. The camp's SBO, Group Captain

Group captain (Gp Capt or G/C) is a senior officer rank used by some air forces, with origins from the Royal Air Force. The rank is used by air forces of many Commonwealth of Nations, countries that have historical British influence.

Group cap ...

Herbert Massey

Air Commodore Herbert Martin Massey, (19 January 189829 February 1976) was a senior officer in the Royal Air Force. He was the Senior British Officer at Stalag Luft III who authorised the "Great Escape".

Flying career

Massey entered the Royal ...

, sent a medical report to the UK authorities. On 10 October 1943, Bryks was transferred to the British military hospital at Stalag VIII-B in Upper Silesia

Upper Silesia ( ; ; ; ; Silesian German: ; ) is the southeastern part of the historical and geographical region of Silesia, located today mostly in Poland, with small parts in the Czech Republic. The area is predominantly known for its heav ...

. He underwent surgery on 7 November and was returned to Stalag Luft III on 23 December.

Stalag Luft III and the Great Escape

Months before Bryks was first sent to Stalag Luft III, preparations had been started for a mass escape of 200 PoWs, now commemorated as the Great Escape. Bryks joined in the preparations, which included completing a long tunnel code named "Harry". On the night of 23/24 March 1944, "Harry" was completed, and PoWs started leaving through it in pairs. Bryks was one of the men listed to escape, but before his turn came, the guards discovered the tunnel exit just outside the perimeter fence. Only three days later, on 27 March, Bryks and aRoyal Australian Air Force

The Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) is the principal Air force, aerial warfare force of Australia, a part of the Australian Defence Force (ADF) along with the Royal Australian Navy and the Australian Army. Constitutionally the Governor-Gener ...

officer, Group Captain Douglas Wilson, tried to escape. Guards saw them and opened fire, so the pair surrendered and were put in solitary confinement.

Unmasked and interrogated

In July 1944, the RAF promoted Bryks to flight lieutenant. Unfortunately the official letter sent from the UK via the Red Cross to tell Bryks of his promotion revealed his real name and nationality. The Gestapo interrogated Bryks, told him his family in Bohemia and Moravia had been arrested and that he would be executed for treason. On 1 September 1944, he was brought to Gestapo headquarters inPetschek Palace

The Petschek Palace ( or ''Pečkárna'') is a Neoclassicism, neoclassicist building in Prague. It was built between 1923 and 1929 by the architect Max Spielmann upon a request from the merchant banker Julius Petschek and was originally called " ...

in Prague. In due course, he was also held at Pankrác Prison

Pankrác Prison, officially Prague Pankrác Remand Prison (), is a prison in Prague, Czech Republic. A part of the Czech Prison Service, it is located southeast of Prague city centre in Pankrác, not far from Pražského povstání metro stati ...

and Loreta Loreta may refer to:

* Loreta, Wisconsin, an unincorporated community in the town of Bear Creek, Sauk County, Wisconsin, United States

* Loreta (Prague), a pilgrimage destination in Hradčany, a district of Prague, Czech Republic

* Loreta (actress) ...

military prison. Twenty-three other Czechoslovak members of the RAFVR were also being held in these prisons. They were repeatedly interrogated and told that under German military law

German military law has a long history.

Early history

Drumhead courts-martial in the German lands had existed since the Early modern period.

The trial of Peter von Hagenbach by an ad hoc tribunal of the Holy Roman Empire in 1474 was the f ...

they were traitors and would be executed.

Through the Red Cross, the British Government

His Majesty's Government, abbreviated to HM Government or otherwise UK Government, is the central government, central executive authority of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

was told that Germany was threatening to execute the Czechoslovak airmen. The United Kingdom replied through the same channel. As the Czechoslovak airmen were UK armed forces personnel, the UK demanded that Germany afford them the same rights and protections as any other PoWs from the UK. Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

threatened that if Germany executed any of them, the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not an explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are calle ...

would execute 10 ''Luftwaffe'' airmen for each Czechoslovak killed.

Germany did not revoke the threat of execution, but the Gestapo did return the Czechoslovaks to PoW camps. On 22 September 1944, Bryks was sent to Stalag Luft I

Stalag Luft I was a German World War II prisoner-of-war (POW) camp near Barth, Western Pomerania, Germany, for captured Allied airmen. The presence of the prison camp is said to have shielded the town of Barth from Allied bombing. About 9,000 ...

near Barth in Western Pomerania

Historical Western Pomerania, also called Cispomerania, Fore Pomerania, Front Pomerania or Hither Pomerania (; ), is the western extremity of the historic region of Pomerania, located mostly in north-eastern Germany, with a small portion in no ...

.

Oflag IV-C, Colditz Castle and liberation

Because of his injuries from Gestapo interrogations, Bryks appeared before an international medical board on 6 November. The board deemed that he should be

Because of his injuries from Gestapo interrogations, Bryks appeared before an international medical board on 6 November. The board deemed that he should be repatriated

Repatriation is the return of a thing or person to its or their country of origin, respectively. The term may refer to non-human entities, such as converting a foreign currency into the currency of one's own country, as well as the return of mi ...

to the UK on medical grounds, but the German authorities refused because he was still accused of treason.

The next day, he was moved to Oflag IV-C

Oflag IV-C, generally known as Colditz Castle, was a prominent German Army prisoner-of-war camp for captured Allied officers during World War II. Located in Colditz, Saxony, the camp operated within the medieval Colditz Castle, which overlooks th ...

at Colditz Castle

Colditz Castle (or ''Schloss Colditz'' in German) is a Renaissance architecture, Renaissance castle in the town of Colditz near Leipzig, Dresden and Chemnitz in the States of Germany, state of Saxony in Germany. The castle is between the towns o ...

in Saxony

Saxony, officially the Free State of Saxony, is a landlocked state of Germany, bordering the states of Brandenburg, Saxony-Anhalt, Thuringia, and Bavaria, as well as the countries of Poland and the Czech Republic. Its capital is Dresden, and ...

. This was a high-security prison for PoWs who had repeatedly escaped from other camps. There he remained until the United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary Land warfare, land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of th ...

liberated the camp on 16 April 1945.

Bryks returned to RAF Cosford in England to recover from his captivity and Gestapo torture. He learnt that his wife Marie in Czechoslovakia had divorced him in his absence, had remarried, and in April 1945 had committed suicide. After Germany surrendered in May 1945, Bryks went to see Gertrude Dellar and proposed to her. They were married on 18 June.

In August 1945, Bryks underwent further surgery for injuries from his Gestapo interrogation. In June 1946, he had surgery to remove a piece of shrapnel that had been embedded in the floor of his mouth when he was shot down in June 1941.

In Czechoslovakia from 1945

On 6 October 1945, Bryks returned to Czechoslovakia with his second wife Gertrude. He resumed his Czechoslovak Air Force career, but his injuries, and particularly his hearing loss, prevented him from serving as a pilot. He was posted to the Military Aviation Academy at Olomouc, where he taught English and the theory of flight. He was promoted tocaptain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

in September 1945, staff captain

Staff captain is the English translation of a number of military ranks:

Historical use of the rank Czechoslovakia

In the Czechoslovak Army, until 1953, staff captain (, ) was a senior captain rank, ranking between captain and major.

Estonia

T ...

in December 1945 and major

Major most commonly refers to:

* Major (rank), a military rank

* Academic major, an academic discipline to which an undergraduate student formally commits

* People named Major, including given names, surnames, nicknames

* Major and minor in musi ...

in May 1946. Also in 1946, Gertrude bore Bryks a daughter, Sonia.

In April 1946, Ealing Studios

Ealing Studios is a television and film production company and facilities provider at Ealing Green in west London, England. Will Barker bought the White Lodge on Ealing Green in 1902 as a base for film making, and films have been made on th ...

released Basil Dearden

Basil Dearden (born Basil Clive Dear; 1 January 1911 – 23 March 1971) was an English film director.

Early life

Dearden was born as Basil Clive Dear at 5 Woodfield Road, Leigh-on-Sea, Essex to Charles James Dear, a steel manufacturer, and the ...

's war film ''The Captive Heart

''The Captive Heart'' is a 1946 British war drama, directed by Basil Dearden and starring Michael Redgrave. It is about a Czechoslovak Army officer who is captured in the Fall of France and spends five years as a prisoner of war, during which ...

''. In it, Michael Redgrave

Sir Michael Scudamore Redgrave (20 March 1908 – 21 March 1985) was an English actor and filmmaker. Beginning his career in theatre, he first appeared in the West End in 1937. He made his film debut in Alfred Hitchcock's ''The Lady Vanishes'' ...

played a Czechoslovak officer based on Bryks, Rachel Kempson

Rachel, Lady Redgrave (28 May 1910 – 24 May 2003), known primarily by her birth name Rachel Kempson, was an English actress. She married Sir Michael Redgrave, and was the matriarch of the famous acting dynasty.

Early life

Kempson was born ...

played a young widow based on Gertrude Dellar, and Basil Radford

Arthur Basil RadfordAdam Greaves, "Radford, (Arthur) Basil (1897–1952)", ''Oxford Dictionary of National Biography'', Oxford University Press, May 201available online Retrieved 3 August 2020. (25 June 189720 October 1952) was an English chara ...

the PoW camp's Senior British Officer (SBO) who protects the Czechoslovak officer.

Persecution

Bryks' air force career continued while a democratic coalition ruled theThird Czechoslovak Republic

The Third Czechoslovak Republic, officially the Czechoslovak Republic, was a sovereign state from April 1945 to February 1948 following the end of World War II.

After the fall of Nazi Germany, the country was reformed and reassigned coterminous ...

. But in February 1948, the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia

The Communist Party of Czechoslovakia ( Czech and Slovak: ''Komunistická strana Československa'', KSČ) was a communist and Marxist–Leninist political party in Czechoslovakia that existed between 1921 and 1992. It was a member of the Com ...

(KSČ) seized power in a coup d'état

A coup d'état (; ; ), or simply a coup

, is typically an illegal and overt attempt by a military organization or other government elites to unseat an incumbent leadership. A self-coup is said to take place when a leader, having come to powe ...

. Bryks was deemed "politically unreliable" and on 9 March was placed on enforced leave and transferred to the military reserve force

A military reserve force is a military organization whose members (reservists) have military and civilian occupations. They are not normally kept under arms, and their main role is to be available when their military requires additional ma ...

. His political opinions resulted in his superior officer, Colonel

Colonel ( ; abbreviated as Col., Col, or COL) is a senior military Officer (armed forces), officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, a colon ...

Václav Fuksa, writing that Bryks was "untrustworthy for his political irresponsibility and for the lack of understanding of the ideology of People's Democracy".

The UK Government informed Bryks that he was to be made a Member of Order of the British Empire (MBE) in recognition of his escapes as a PoW and the help he gave to other escapees. He was invited to

The UK Government informed Bryks that he was to be made a Member of Order of the British Empire (MBE) in recognition of his escapes as a PoW and the help he gave to other escapees. He was invited to Buckingham Palace

Buckingham Palace () is a royal official residence, residence in London, and the administrative headquarters of the monarch of the United Kingdom. Located in the City of Westminster, the palace is often at the centre of state occasions and r ...

in London to be decorated. But the communist authorities refused to grant him a visa to leave Czechoslovakia. Therefore, the UK Ambassador to Czechoslovakia presented Bryks with his MBE at the UK Embassy in Prague.

Three trials

Just after midnight on the night of 2–3 May 1948, theStB

State Security (, ), or StB / ŠtB, was the secret police force in communist Czechoslovakia from 1945 to its dissolution in 1990. Serving as an intelligence and counter-intelligence agency, it dealt with any activity that was considered oppositio ...

secret police arrested Bryks at his home in Olomouc. He was charged with involvement in an alleged attempt by other former RAF airmen, including Air Marshal Karel Janoušek

Karel Janoušek, (30 October 1893 – 27 October 1971) was a senior Czechoslovak Air Force officer. He began his career as a soldier, serving in the Austrian Imperial-Royal Landwehr 1915–16, Czechoslovak Legion#Ranks of the Czechoslovak Legi ...

, to escape to the West. Bryks was court-martial

A court-martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of members of the arme ...

led in Prague between 14 and 16 July 1948 and was found not guilty, because communists did not yet control these courts. But the prosecutor appealed and Bryks remained in prison.

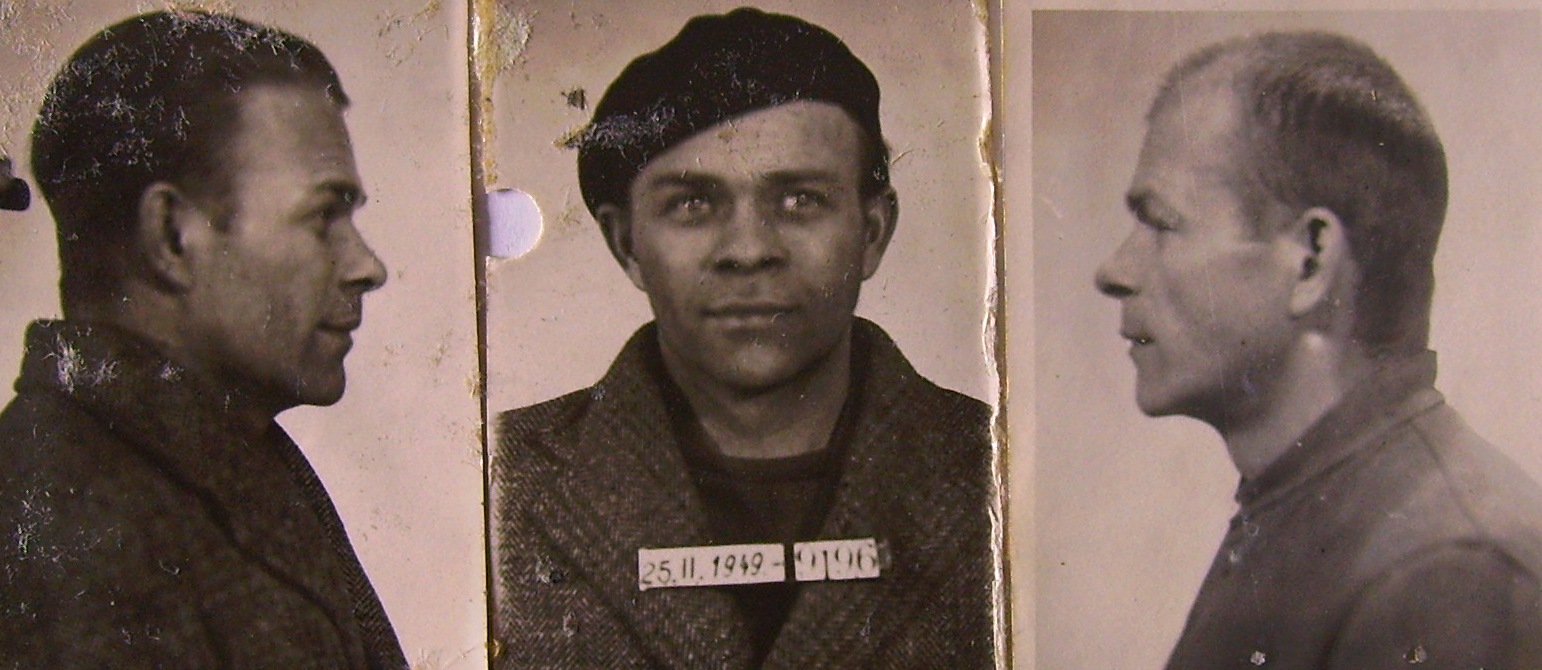

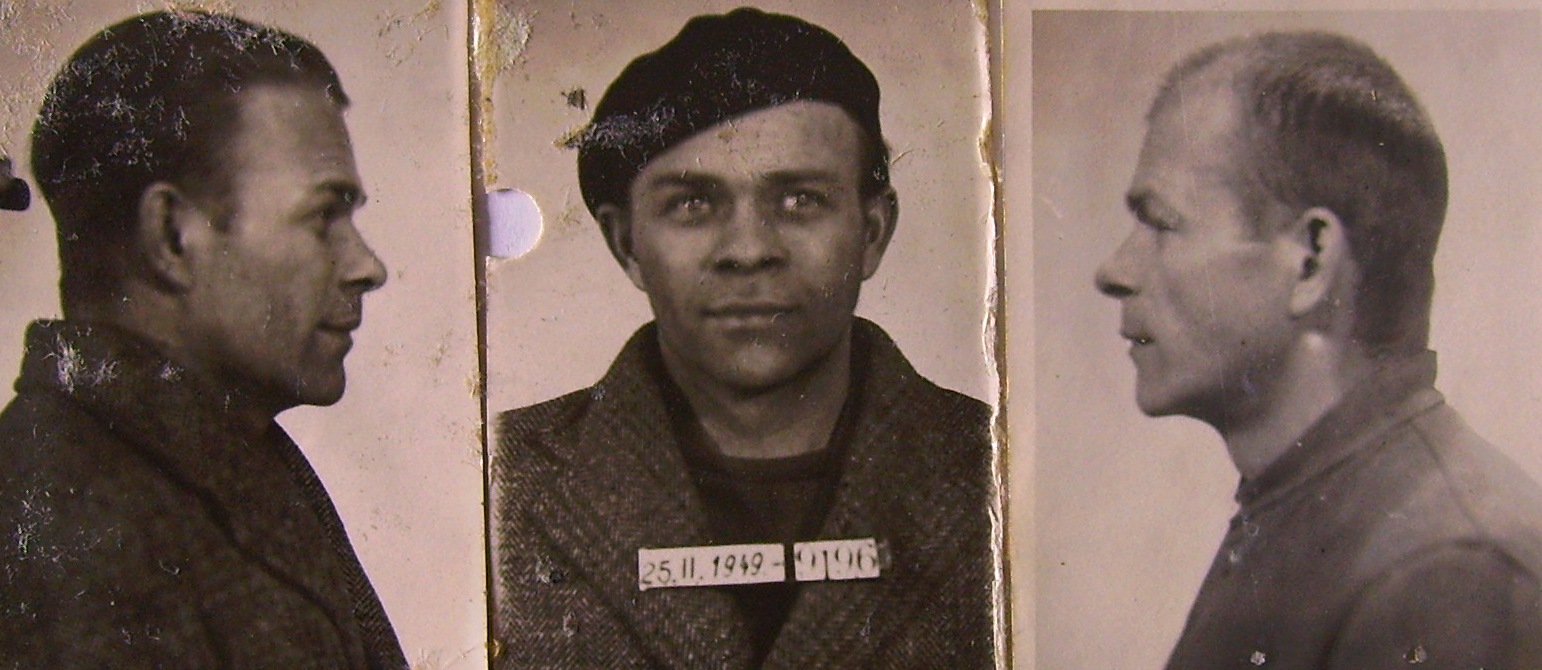

Bryks was retried on 2 September 1949. By now the communists controlled the courts. He was found guilty and sentenced to 10 years imprisonment. He was stripped of his rank and medals and expelled from the air force. His wife obtained an exit visa for herself and their young daughter, stating that it was to pay her parents in England a short visit. In fact, she left Czechoslovakia for the duration of the communist era, and did not return until 2009.

After his conviction, Bryks was held first in Pankrác, in the same prison where the Gestapo had held him in 1944. On 17 August 1949, he was transferred to Bory prison in

After his conviction, Bryks was held first in Pankrác, in the same prison where the Gestapo had held him in 1944. On 17 August 1949, he was transferred to Bory prison in Plzeň

Plzeň (), also known in English and German as Pilsen (), is a city in the Czech Republic. It is the Statutory city (Czech Republic), fourth most populous city in the Czech Republic with about 188,000 inhabitants. It is located about west of P ...

. On 18 April, the prison authorities announced that they had uncovered a plan for a prison uprising

A prison riot is an act of concerted defiance or disorder by a group of prisoners against the prison administrators, prison officers, or other groups of prisoners.

Academic studies of prison riots emphasize a connection between prison conditions ...

and mass escape. Bryks was among those accused of the allaged plot. He was tried on 11 May 1950 and found guilty. His sentence was extended with 20 years hard labour

Penal labour is a term for various kinds of forced labour that prisoners are required to perform, typically manual labour. The work may be light or hard, depending on the context. Forms of sentence involving penal labour have included inv ...

and he was fined Kčs

The Czechoslovak koruna (in Czech and Slovak: ''koruna československá'', at times ''koruna česko-slovenská''; ''koruna'' means ''crown'') was the currency of Czechoslovakia from 10 April 1919 to 14 March 1939, and from 1 November 1945 to 7 ...

20,000. His wife protested to the General Secretary

Secretary is a title often used in organizations to indicate a person having a certain amount of authority, Power (social and political), power, or importance in the organization. Secretaries announce important events and communicate to the org ...

of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia

The Communist Party of Czechoslovakia ( Czech and Slovak: ''Komunistická strana Československa'', KSČ) was a communist and Marxist–Leninist political party in Czechoslovakia that existed between 1921 and 1992. It was a member of the Com ...

, Rudolf Slánský

Rudolf Slánský (31 July 1901 – 3 December 1952) was a leading Czech Communist politician. Holding the post of the party's General Secretary after World War II, he was one of the leading creators and organizers of Communist rule in Czechoslova ...

, but received no answer.

On 6 November 1950, Bryks was transferred to a prison at

On 6 November 1950, Bryks was transferred to a prison at Opava

Opava (; , ) is a city in the Moravian-Silesian Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 55,000 inhabitants. It lies on the Opava (river), Opava River. Opava is one of the historical centres of Silesia and was a historical capital of Czech Sile ...

in Czech Silesia

Czech Silesia (; ) is the part of the historical region of Silesia now in the Czech Republic. While it currently has no formal boundaries, in a narrow geographic sense, it encompasses most or all of the territory of the Czech Republic within the ...

. There were other former RAF political prisoner

A political prisoner is someone imprisoned for their political activity. The political offense is not always the official reason for the prisoner's detention.

There is no internationally recognized legal definition of the concept, although ...

s, included Karel Janoušek. Bryks was insubordinate and resisted the prison authorities. On 18 June 1952, he was transferred to Leopoldov Prison

The Leopoldov Prison () is a Slovak state-operated penitentiary facility located in the town of Leopoldov. Initially a 17th-century fortress built to defend against Ottoman Turks, it was converted into a high-security prison in the 19th century, ...

, a converted 17th-century fortress in Slovakia. There he continued to resist the prison authorities, and he was again accused of planning to escape.

Uranium mine and death

Finally he was moved to a prison inOstrov nad Ohří

Ostrov (also called Ostrov nad Ohří; ; ) is a town in Karlovy Vary District in the Karlovy Vary Region of the Czech Republic. It has about 16,000 inhabitants. The historic town centre is well preserved and is protected by law as an urban monumen ...

in western Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; ; ) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. In a narrow, geographic sense, it roughly encompasses the territories of present-day Czechia that fall within the Elbe River's drainage basin, but historic ...

and made to work in a uranium mine

Uranium mining is the process of extraction of uranium ore from the earth. Over 50,000 tons of uranium were produced in 2019. Kazakhstan, Canada, and Australia were the top three uranium producers, respectively, and together account for 68% of w ...

called ''Rovnost'' (The Czech word for "Equality"). Here prisoners were paid a small wage for their work. Bryks worked hard, exceeding his work quotas, and sent his wage to help support his sick father and his wife and daughter. But in December 1955, the Communists banned Bryks from sending money to his family.

Bryks resumed his resistance, but his health worsened. On 11 August 1957, he suffered a massive heart attack. He died in the prison hospital at Ostrov nad Ohří. The Communist authorities notified his wife in England in a brief telephone call, in which they gave her no further details.

Bryks' remains were not released to his family. The Communists secretly cremated him. Eight years later, in 1965, they buried his ashes in a cemetery in the Motol district of Prague.

Bryks resumed his resistance, but his health worsened. On 11 August 1957, he suffered a massive heart attack. He died in the prison hospital at Ostrov nad Ohří. The Communist authorities notified his wife in England in a brief telephone call, in which they gave her no further details.

Bryks' remains were not released to his family. The Communists secretly cremated him. Eight years later, in 1965, they buried his ashes in a cemetery in the Motol district of Prague.

Rehabilitation and monuments

Bryks was rehabilitated after the November 1989Velvet Revolution

The Velvet Revolution () or Gentle Revolution () was a non-violent transition of power in what was then Czechoslovakia, occurring from 17 November to 28 November 1989. Popular demonstrations against the one-party government of the Communist Pa ...

. On 29 May 1991, the Czech and Slovak Federative Republic

After the Velvet Revolution in Revolutions of 1989, late-1989, Czechoslovakia adopted the official short-lived country name Czech and Slovak Federative Republic (, ; ''ČSFR'') during the period from 23 April 1990 until 31 December 1992, after w ...

posthumously promoted Bryks to colonel. A memorial plaque to him in front of the local war memorial at his birthplace in Lašťany was unveiled on 4 June 1994.

In 2004, Bryks was honoured with the "Award of the City of Olomouc" for "bravery and courage during the Second World War". A memorial plaque was unveiled outside 5 Hanáckého pluku, Olomouc, where Bryks was living with his wife and daughter when the StB arrested him in 1948.

In 2006, a court in Prague finally exonerated him of his false convictions.

On 28 October 2006, the

In 2004, Bryks was honoured with the "Award of the City of Olomouc" for "bravery and courage during the Second World War". A memorial plaque was unveiled outside 5 Hanáckého pluku, Olomouc, where Bryks was living with his wife and daughter when the StB arrested him in 1948.

In 2006, a court in Prague finally exonerated him of his false convictions.

On 28 October 2006, the Czech Republic

The Czech Republic, also known as Czechia, and historically known as Bohemia, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. The country is bordered by Austria to the south, Germany to the west, Poland to the northeast, and Slovakia to the south ...

gave Bryks its highest award, the Order of the White Lion

The Order of the White Lion () is the highest order of the Czech Republic. It continues a Czechoslovak order of the same name created in 1922 as an award for foreigners (Czechoslovakia having no civilian decoration for its citizens in the 192 ...

, military division, 2nd class. In 2008 the Czech Republic posthumously promoted Bryks to brigadier general.

Two streets are named after Bryks: one in the Černý Most

Černý Most (, lit. 'Black Bridge') is a large panel building, panel housing estate in the north-east of Prague, belonging to Prague 14. At the end of 2013 it was home to 22,355 residents. As well as residential complexes, the area has a large r ...

suburb of Prague and the other in Slavonín on the edge of Olomouc.

In 2007, Czech Television

Czech Television ( ; abbreviation: ČT) is a public television broadcaster in the Czech Republic, broadcasting six channels. Established after breakup of Czechoslovakia in 1992, it is the successor to Czechoslovak Television founded in 1953.

H ...