Josef Brodsky on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

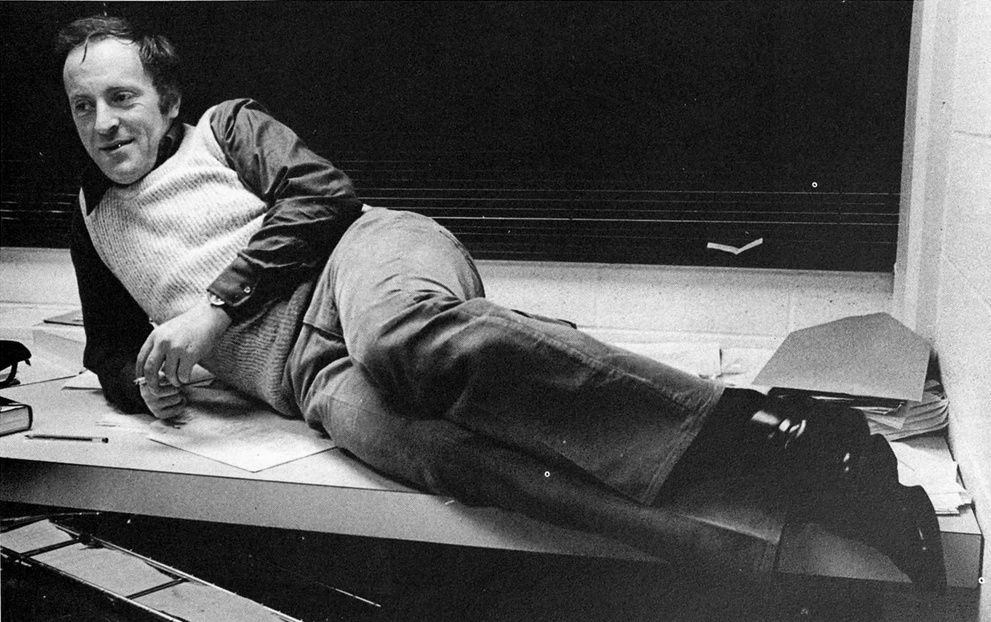

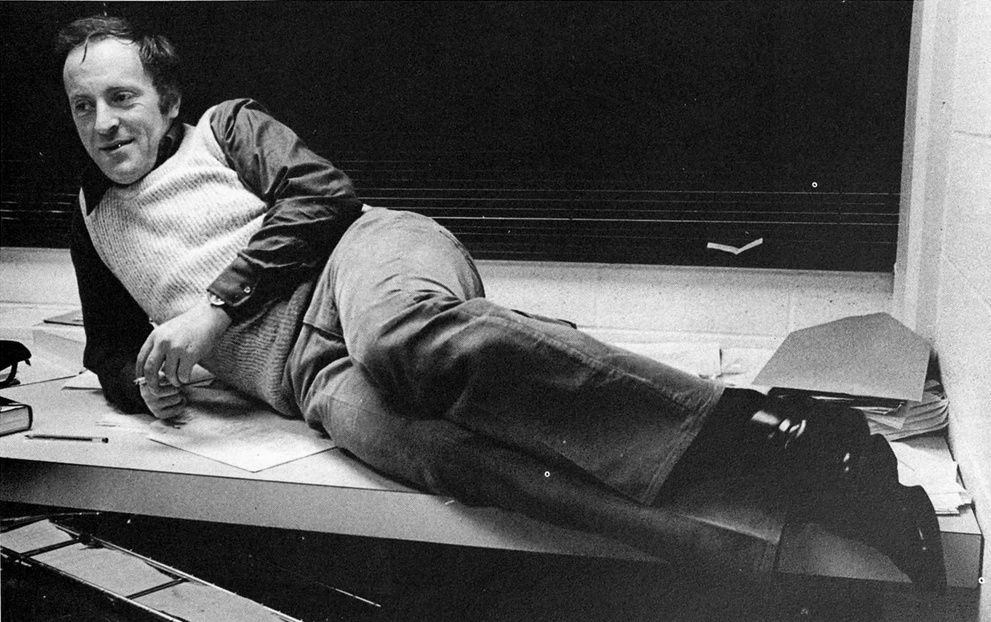

Iosif Aleksandrovich Brodsky (; ; 24 May 1940 – 28 January 1996) was a Russian and American poet and essayist. Born in Leningrad (now

For his "parasitism" Brodsky was sentenced to five years hard labor and served 18 months on a farm in the village of Norenskaya, in the

For his "parasitism" Brodsky was sentenced to five years hard labor and served 18 months on a farm in the village of Norenskaya, in the

"Timelessness: Water Frees Time from Time Itself"

, ''Neva News'', 1 August 2007. Brodsky became a His son, Andrei, was born on 8 October 1967, and Basmanova broke off the relationship. Andrei was registered under Basmanova's surname because Brodsky did not want his son to suffer from the political attacks that he endured. Marina Basmanova was threatened by the Soviet authorities, which prevented her from marrying Brodsky or joining him when he was exiled from the country. After the birth of their son, Brodsky continued to dedicate love poetry to Basmanova. In 1989, Brodsky wrote his last poem to "M.B.", describing himself remembering their life in Leningrad:

Brodsky returned to Leningrad in December 1965 and continued to write over the next seven years, many of his works being translated into German, French, and English and published abroad. ''Verses and Poems'' was published by Inter-Language Literary Associates in Washington in 1965, ''Elegy to

His son, Andrei, was born on 8 October 1967, and Basmanova broke off the relationship. Andrei was registered under Basmanova's surname because Brodsky did not want his son to suffer from the political attacks that he endured. Marina Basmanova was threatened by the Soviet authorities, which prevented her from marrying Brodsky or joining him when he was exiled from the country. After the birth of their son, Brodsky continued to dedicate love poetry to Basmanova. In 1989, Brodsky wrote his last poem to "M.B.", describing himself remembering their life in Leningrad:

Brodsky returned to Leningrad in December 1965 and continued to write over the next seven years, many of his works being translated into German, French, and English and published abroad. ''Verses and Poems'' was published by Inter-Language Literary Associates in Washington in 1965, ''Elegy to

After a short stay in Vienna, Brodsky settled in

After a short stay in Vienna, Brodsky settled in

Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the List of cities and towns in Russia by population, second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the Neva, River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland ...

) in the Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

, Brodsky ran afoul of Soviet authorities and was expelled ("strongly advised" to emigrate) from the Soviet Union in 1972, settling in the United States with the help of W. H. Auden

Wystan Hugh Auden (; 21 February 1907 – 29 September 1973) was a British-American poet. Auden's poetry is noted for its stylistic and technical achievement, its engagement with politics, morals, love, and religion, and its variety in tone, ...

and other supporters. He taught thereafter at Mount Holyoke College

Mount Holyoke College is a Private college, private Women's colleges in the United States, women's Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in South Hadley, Massachusetts, United States. It is the oldest member of the h ...

, and at universities including Yale

Yale University is a private Ivy League research university in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701, Yale is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States, and one of the nine colonial colleges ch ...

, Columbia, Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a List of cities in the United Kingdom, city and non-metropolitan district in the county of Cambridgeshire, England. It is the county town of Cambridgeshire and is located on the River Cam, north of London. As of the 2021 Unit ...

, and Michigan

Michigan ( ) is a peninsular U.S. state, state in the Great Lakes region, Great Lakes region of the Upper Midwest, Upper Midwestern United States. It shares water and land boundaries with Minnesota to the northwest, Wisconsin to the west, ...

. Brodsky was awarded the 1987 Nobel Prize in Literature

The 1987 Nobel Prize in Literature was awarded to the Russian–American poet and essayist Joseph Brodsky (1940–1996) "for an all-embracing authorship, imbued with clarity of thought and poetic intensity."

Laureate

At the age of 18, Joseph Brod ...

"for an all-embracing authorship, imbued with clarity of thought and poetic intensity". He was appointed United States Poet Laureate

The poet laureate consultant in poetry to the Library of Congress, commonly referred to as the United States poet laureate, serves as the official poet of the United States. During their term, the poet laureate seeks to raise the national consc ...

in 1991.

According to Professor Andrey Ranchin of Moscow State University

Moscow State University (MSU), officially M. V. Lomonosov Moscow State University,. is a public university, public research university in Moscow, Russia. The university includes 15 research institutes, 43 faculties, more than 300 departments, a ...

, "Brodsky is the only modern Russian poet whose body of work has already been awarded the honorary title of a canonized classic... Brodsky's literary canonization is an exceptional phenomenon. No other contemporary Russian writer has been honored as the hero of such a number of memoir texts; no other has had so many conferences devoted to them." Daniel Murphy, in his seminal text ''Christianity and Modern European Literature'', includes Brodsky among the most influential Christian

A Christian () is a person who follows or adheres to Christianity, a Monotheism, monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus Christ. Christians form the largest religious community in the wo ...

poets of the 20th century, along with T. S. Eliot

Thomas Stearns Eliot (26 September 18884 January 1965) was a poet, essayist and playwright.Bush, Ronald. "T. S. Eliot's Life and Career", in John A Garraty and Mark C. Carnes (eds), ''American National Biography''. New York: Oxford University ...

, Osip Mandelstam

Osip Emilyevich Mandelstam (, ; – 27 December 1938) was a Russian and Soviet poet. He was one of the foremost members of the Acmeist school.

Osip Mandelstam was arrested during the repressions of the 1930s and sent into internal exile wi ...

, Anna Akhmatova

Anna Andreyevna Gorenko rus, А́нна Андре́евна Горе́нко, p=ˈanːə ɐnˈdrʲe(j)ɪvnə ɡɐˈrʲɛnkə, a=Anna Andreyevna Gorenko.ru.oga, links=yes; , . ( – 5 March 1966), better known by the pen name Anna Akhmatova,. ...

(Brodsky's mentor for a time), and W. H. Auden (who sponsored Brodsky's cause in the United States). Irene Steckler was the first to categorically state that Brodsky was "unquestionably a Christian poet". Before that, in July 1972, following his exile, Brodsky himself, in an interview, said: "While I am related to the Old Testament perhaps by ancestry, and certainly the spirit of justice, I consider myself a Christian. Not a good one but I try to be." The contemporary Russian poet and fellow-Acmeist

Acmeism, or the Guild of Poets, was a modernist transient poetic school, which emerged or in 1912 in Russia under the leadership of Nikolay Gumilev and Sergei Gorodetsky. Their ideals were compactness of form and clarity of expression. The term ...

, Viktor Krivulin

Viktor Borisovich Krivulin (; 9 July 1944 – 17 March 2001) was a Russian poet, novelist and essayist.

Biography

Krivulin graduated from the faculty of philology from Leningrad State University. He opted for independent cultural activity and ...

, said that "Brodsky always felt his Jewishness

Jewish identity is the objective or subjective sense of perceiving oneself as a Jew and as relating to being Jewish. It encompasses elements of nationhood, "The Jews are a nation and were so before there was a Jewish state of Israel" "Jews are ...

as a religious thing, despite the fact that, when all is said and done, he's a Christian poet."

Early years

Brodsky was born into aRussian Jewish

The history of the Jews in Russia and areas historically connected with it goes back at least 1,500 years. Jews in Russia have historically constituted a large religious and ethnic diaspora; the Russian Empire at one time hosted the largest po ...

family in Leningrad (now Saint Petersburg). A descendant of a prominent and ancient rabbinic family, Schorr (Shor) his direct male-line ancestor was Joseph ben Isaac Bekhor Shor

Joseph ben Isaac Bekhor Shor of Orléans (12th century) () was a French tosafist, exegete, and poet who flourished in the second half of the 12th century. He was the father of Abraham ben Joseph of Orleans and Saadia Bekhor Shor.

Biography ...

. His father, Aleksandr Brodsky, was a professional photographer in the Soviet Navy

The Soviet Navy was the naval warfare Military, uniform service branch of the Soviet Armed Forces. Often referred to as the Red Fleet, the Soviet Navy made up a large part of the Soviet Union's strategic planning in the event of a conflict with t ...

, and his mother, Maria Volpert Brodskaya, a professional interpreter whose work often helped to support the family. They lived in communal apartments, in poverty, marginalized by their Jewish status. In early childhood, Brodsky survived the Siege of Leningrad

The siege of Leningrad was a Siege, military blockade undertaken by the Axis powers against the city of Leningrad (present-day Saint Petersburg) in the Soviet Union on the Eastern Front (World War II), Eastern Front of World War II from 1941 t ...

where he and his parents nearly died of starvation; one aunt did die of hunger. He later developed various health problems caused by the siege. Brodsky commented that many of his teachers were anti-Jewish

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

and that he felt like a dissident from an early age. He noted "I began to despise Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

, even when I was in the first grade, not so much because of his political philosophy or practice ... but because of his omnipresent images."

As a young student, Brodsky was "an unruly child" known for his misbehavior during classes. At fifteen, Brodsky left school and tried to enter the School of Submariners without success. He went on to work as a milling machine operator. Later, having decided to become a physician, he worked at the morgue

A morgue or mortuary (in a hospital or elsewhere) is a place used for the storage of human corpses awaiting identification (ID), removal for autopsy, respectful burial, cremation or other methods of disposal. In modern times, corpses have cu ...

at the Kresty Prison

Kresty (, literally ''Crosses'') prison, officially Investigative Isolator No. 1 of the Administration of the Federal Service for the Execution of Punishments for the city of Saint Petersburg (Следственный изолятор № 1 УФ� ...

, cutting and sewing bodies. He subsequently held a variety of jobs in hospitals, in a ship's boiler room, and on geological expeditions. At the same time, Brodsky engaged in a program of self-education. He learned Polish so he could translate the works of Polish poets such as Czesław Miłosz

Czesław Miłosz ( , , ; 30 June 1911 – 14 August 2004) was a Polish Americans, Polish-American poet, prose writer, translator, and diplomat. He primarily wrote his poetry in Polish language, Polish. Regarded as one of the great poets of the ...

, and English so that he could translate John Donne

John Donne ( ; 1571 or 1572 – 31 March 1631) was an English poet, scholar, soldier and secretary born into a recusant family, who later became a clergy, cleric in the Church of England. Under Royal Patronage, he was made Dean of St Paul's, D ...

. On the way, he acquired a deep interest in classical philosophy

Classical may refer to:

European antiquity

*Classical antiquity, a period of history from roughly the 7th or 8th century B.C.E. to the 5th century C.E. centered on the Mediterranean Sea

* Classical architecture, architecture derived from Greek an ...

, religion, mythology

Myth is a genre of folklore consisting primarily of narratives that play a fundamental role in a society. For scholars, this is very different from the vernacular usage of the term "myth" that refers to a belief that is not true. Instead, the ...

, and English and American poetry.

Career and family

Early career

In 1955, Brodsky began writing his own poetry and producing literary translations. He circulated them in secret, and some were published by the underground journal, '' Sintaksis'' (Syntax, ). His writings were apolitical. By 1958 he was already well known in literary circles for his poems "The Jewish cemetery near Leningrad" and "Pilgrims". Asked when he first felt called to poetry, he recollected, "In 1959, inYakutsk

Yakutsk ( ) is the capital and largest city of Sakha, Russia, located about south of the Arctic Circle. Fueled by the mining industry, Yakutsk has become one of Russia's most rapidly growing regional cities, with a population of 355,443 at the ...

, when walking in that terrible city, I went into a bookstore. I snagged a copy of poems by Baratynsky. I had nothing to read. So I read that book and finally understood what I had to do in life. Or got very excited, at least. So in a way, Evgeny Abramovich Baratynsky is sort of responsible." His friend, Ludmila Shtern (, ''Ljudmíla Jákovlevna Štern''), recalled working with Brodsky on an irrigation project in his "geological period" (working as a geologist's assistant): "We bounced around the Leningrad Province examining kilometers of canals, checking their embankments, which looked terrible. They were falling down, coming apart, had all sorts of strange things growing in them... It was during these trips, however, that I was privileged to hear the poems "The Hills" and "You Will Gallop in the Dark". Brodsky read them aloud to me between two train cars as we were going towards Tikhvin

Tikhvin (; Veps: ) is a town and the administrative center of Tikhvinsky District in Leningrad Oblast, Russia, located on both banks of the Tikhvinka River in the east of the oblast, east of St. Petersburg. Tikhvin is also an industrial ...

."

In 1960, the young Brodsky met Anna Akhmatova

Anna Andreyevna Gorenko rus, А́нна Андре́евна Горе́нко, p=ˈanːə ɐnˈdrʲe(j)ɪvnə ɡɐˈrʲɛnkə, a=Anna Andreyevna Gorenko.ru.oga, links=yes; , . ( – 5 March 1966), better known by the pen name Anna Akhmatova,. ...

, one of the leading poets of the silver age

The Ages of Man are the historical stages of human existence according to Greek mythology and its subsequent interpretatio romana, Roman interpretation.

Both Hesiod and Ovid offered accounts of the successive ages of humanity, which tend to pr ...

. She encouraged his work, and became his mentor. In 1962, in Leningrad

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the List of cities and towns in Russia by population, second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the Neva, River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland ...

, Anna Akhmatova introduced him to the artist Marina Basmanova, a young painter from an established artistic family who was drawing Akhmatova's portrait. The two started a relationship; however, Brodsky's then close friend and fellow poet, Dmitri Bobyshev, was in love with Basmanova. As Bobyshev began to pursue the woman, immediately, the authorities began to pursue Brodsky; Bobyshev was widely held responsible for denouncing him. Brodsky dedicated much love poetry to Marina Basmanova:

Denunciation

In 1963, Brodsky's poetry was denounced by a Leningrad newspaper as "pornographic andanti-Soviet

Anti-Sovietism or anti-Soviet sentiment are activities that were actually or allegedly aimed against the Soviet Union or government power within the Soviet Union.

Three common uses of the term include the following:

* Anti-Sovietism in inter ...

". His papers were confiscated, he was interrogated, twice put in a mental institution and then arrested. He was charged with social parasitism by the Soviet

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

authorities in a trial in 1964, finding that his series of odd jobs and role as a poet were not a sufficient contribution to society. They called him "a pseudo-poet in velveteen

Velveteen (or velveret) is a type of woven textile, fabric with a dense, even, short Pile (textile), pile. It has less sheen than velvet because the pile in velveteen is cut from weft threads, while that of velvet is cut from warp threads. Velvet ...

trousers" who failed to fulfill his "constitutional duty to work honestly for the good of the motherland". The trial judge asked, "Who has recognized you as a poet? Who has enrolled you in the ranks of poets?" – "No one", Brodsky replied, "Who enrolled me in the ranks of the human race?"

For his "parasitism" Brodsky was sentenced to five years hard labor and served 18 months on a farm in the village of Norenskaya, in the

For his "parasitism" Brodsky was sentenced to five years hard labor and served 18 months on a farm in the village of Norenskaya, in the Archangelsk

Arkhangelsk (, ) is a city and the administrative center of Arkhangelsk Oblast, Russia. It lies on both banks of the Northern Dvina near its mouth into the White Sea. The city spreads for over along the banks of the river and numerous islands o ...

region, 350 miles from Leningrad. He rented his own small cottage, and although it was without plumbing or central heating, having one's own, private space was taken to be a great luxury at the time. Basmanova, Bobyshev, and Brodsky's mother, among others, visited. He wrote on his typewriter, chopped wood, hauled manure, and at night read his anthologies of English and American poetry, including a lot of W. H. Auden and Robert Frost

Robert Lee Frost (March26, 1874January29, 1963) was an American poet. Known for his realistic depictions of rural life and his command of American Colloquialism, colloquial speech, Frost frequently wrote about settings from rural life in New E ...

. Brodsky's close friend and biographer Lev Loseff writes that while his confinement in the mental hospital and the trial were miserable experiences, the 18 months in the Arctic were among the best times of Brodsky's life. Brodsky's mentor, Anna Akhmatova

Anna Andreyevna Gorenko rus, А́нна Андре́евна Горе́нко, p=ˈanːə ɐnˈdrʲe(j)ɪvnə ɡɐˈrʲɛnkə, a=Anna Andreyevna Gorenko.ru.oga, links=yes; , . ( – 5 March 1966), better known by the pen name Anna Akhmatova,. ...

, laughed at the KGB

The Committee for State Security (, ), abbreviated as KGB (, ; ) was the main security agency of the Soviet Union from 1954 to 1991. It was the direct successor of preceding Soviet secret police agencies including the Cheka, Joint State Polit ...

's shortsightedness. "What a biography they're fashioning for our red-haired friend!", she said. "It's as if he'd hired them to do it on purpose."

Brodsky's sentence was commuted in 1965 after protests by prominent Soviet and foreign cultural figures, including Evgeny Evtushenko

Yevgeny Aleksandrovich Yevtushenko (; 18 July 1933 – 1 April 2017) was a Soviet and Russian poet, novelist, essayist, dramatist, screenwriter, publisher, actor, editor, university professor, and director of several films.

Biography Early lif ...

, Dmitri Shostakovich

Dmitri Dmitriyevich Shostakovich, group=n (9 August 1975) was a Soviet-era Russian composer and pianist who became internationally known after the premiere of his First Symphony in 1926 and thereafter was regarded as a major composer.

Shostak ...

, and Jean-Paul Sartre

Jean-Paul Charles Aymard Sartre (, ; ; 21 June 1905 – 15 April 1980) was a French philosopher, playwright, novelist, screenwriter, political activist, biographer, and literary criticism, literary critic, considered a leading figure in 20th ...

as well as Akhmatova.Natalia Zhdanova"Timelessness: Water Frees Time from Time Itself"

, ''Neva News'', 1 August 2007. Brodsky became a

cause célèbre

A ( , ; pl. ''causes célèbres'', pronounced like the singular) is an issue or incident arousing widespread controversy, outside campaigning, and heated public debate. The term is sometimes used positively for celebrated legal cases for th ...

in the West also, when a secret transcription of trial minutes was smuggled out of the country, making him a symbol of artistic resistance in a totalitarian

Totalitarianism is a political system and a form of government that prohibits opposition from political parties, disregards and outlaws the political claims of individual and group opposition to the state, and completely controls the public sph ...

society, much like his mentor, Akhmatova.

His son, Andrei, was born on 8 October 1967, and Basmanova broke off the relationship. Andrei was registered under Basmanova's surname because Brodsky did not want his son to suffer from the political attacks that he endured. Marina Basmanova was threatened by the Soviet authorities, which prevented her from marrying Brodsky or joining him when he was exiled from the country. After the birth of their son, Brodsky continued to dedicate love poetry to Basmanova. In 1989, Brodsky wrote his last poem to "M.B.", describing himself remembering their life in Leningrad:

Brodsky returned to Leningrad in December 1965 and continued to write over the next seven years, many of his works being translated into German, French, and English and published abroad. ''Verses and Poems'' was published by Inter-Language Literary Associates in Washington in 1965, ''Elegy to

His son, Andrei, was born on 8 October 1967, and Basmanova broke off the relationship. Andrei was registered under Basmanova's surname because Brodsky did not want his son to suffer from the political attacks that he endured. Marina Basmanova was threatened by the Soviet authorities, which prevented her from marrying Brodsky or joining him when he was exiled from the country. After the birth of their son, Brodsky continued to dedicate love poetry to Basmanova. In 1989, Brodsky wrote his last poem to "M.B.", describing himself remembering their life in Leningrad:

Brodsky returned to Leningrad in December 1965 and continued to write over the next seven years, many of his works being translated into German, French, and English and published abroad. ''Verses and Poems'' was published by Inter-Language Literary Associates in Washington in 1965, ''Elegy to John Donne

John Donne ( ; 1571 or 1572 – 31 March 1631) was an English poet, scholar, soldier and secretary born into a recusant family, who later became a clergy, cleric in the Church of England. Under Royal Patronage, he was made Dean of St Paul's, D ...

and Other Poems'' was published in London in 1967 by Longmans Green, and ''A Stop in the Desert'' was issued in 1970 by Chekhov Publishing in New York. Only four of his poems were published in Leningrad anthologies in 1966 and 1967, most of his work appearing outside the Soviet Union or circulated in secret (samizdat

Samizdat (, , ) was a form of dissident activity across the Eastern Bloc in which individuals reproduced censored and underground makeshift publications, often by hand, and passed the documents from reader to reader. The practice of manual rep ...

) until 1987. Persecuted for his poetry and his Jewish heritage, he was denied permission to travel. In 1972, while Brodsky was being considered for exile, the authorities consulted mental health expert Andrei Snezhnevsky

Andrei Vladimirovich Snezhnevsky ( rus, Андре́й Влади́мирович Снежне́вский, p=sʲnʲɪˈʐnʲefskʲɪj; – 12 July 1987) was a Soviet psychiatrist whose name was lent to the unbridled broadening of the diagnostic ...

, a key proponent of the notorious pseudo-medical diagnosis of "paranoid reformist delusion". This political tool allowed the state to lock up dissenters in psychiatric institutions indefinitely. Without examining him personally, Snezhnevsky diagnosed Brodsky as having " sluggishly progressing schizophrenia", concluding that he was "not a valuable person at all and may be let go". In 1971, Brodsky was invited twice to emigrate to Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

. When called to the Ministry of the Interior

An interior ministry or ministry of the interior (also called ministry of home affairs or ministry of internal affairs) is a government department that is responsible for domestic policy, public security and law enforcement.

In some states, the ...

in 1972 and asked why he had not accepted, he stated that he wished to stay in the country. Within ten days officials broke into his apartment, took his papers, and on 4 June 1972, put him on a plane for Vienna

Vienna ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital, List of largest cities in Austria, most populous city, and one of Federal states of Austria, nine federal states of Austria. It is Austria's primate city, with just over two million inhabitants. ...

, Austria

Austria, formally the Republic of Austria, is a landlocked country in Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine Federal states of Austria, states, of which the capital Vienna is the List of largest cities in Aust ...

. He never returned to Russia and never saw Basmanova again. Brodsky later wrote "The Last Judgement is the Last Judgement, but a human being who spent his life in Russia, has to be, without any hesitation, placed into Paradise."

In Austria, he met Carl Ray Proffer

Carl Ray Proffer (September 3, 1938, Buffalo, New YorkSeptember 24, 1984, Ann Arbor, Michigan) was an American publisher, scholar, professor, and translator of Russian literature. He was the co-founder (with Ellendea Proffer) of Ardis Publishers ...

and Auden, who facilitated Brodsky's transit to the United States and proved influential to Brodsky's career. Proffer, of the University of Michigan

The University of Michigan (U-M, U of M, or Michigan) is a public university, public research university in Ann Arbor, Michigan, United States. Founded in 1817, it is the oldest institution of higher education in the state. The University of Mi ...

and one of the co-founders of Ardis Publishers

Ardis Publishing (until 2002, Ardis Publishers) began in 1971, as the only publishing house outside of Russia dedicated to Russian literature in both English and Russian, Ardis was founded in Ann Arbor, Michigan, United States, by husband and wif ...

, became Brodsky's Russian publisher from this point on. Recalling his landing in Vienna, Brodsky commented:

Although the poet was invited back after the fall of the Soviet Union, Brodsky never returned to his country.

United States

After a short stay in Vienna, Brodsky settled in

After a short stay in Vienna, Brodsky settled in Ann Arbor

Ann Arbor is a city in Washtenaw County, Michigan, United States, and its county seat. The 2020 United States census, 2020 census recorded its population to be 123,851, making it the List of municipalities in Michigan, fifth-most populous cit ...

, with the help of poets Auden and Proffer, and became poet-in-residence at the University of Michigan

The University of Michigan (U-M, U of M, or Michigan) is a public university, public research university in Ann Arbor, Michigan, United States. Founded in 1817, it is the oldest institution of higher education in the state. The University of Mi ...

for a year. Brodsky went on to become a visiting professor at Queens College

Queens College (QC) is a public college in the New York City borough of Queens. Part of the City University of New York system, Queens College occupies an campus primarily located in Flushing.

Queens College was established in 1937 and offe ...

(1973–74), Smith College

Smith College is a Private university, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts Women's colleges in the United States, women's college in Northampton, Massachusetts, United States. It was chartered in 1871 by Sophia Smit ...

, Columbia University

Columbia University in the City of New York, commonly referred to as Columbia University, is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New York City. Established in 1754 as King's College on the grounds of Trinity Churc ...

, and Cambridge University

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209, the University of Cambridge is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, wo ...

, later returning to the University of Michigan (1974–80). He was the Andrew Mellon Professor of Literature and Five College Professor of Literature at Mount Holyoke College

Mount Holyoke College is a Private college, private Women's colleges in the United States, women's Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in South Hadley, Massachusetts, United States. It is the oldest member of the h ...

, brought there by poet and historian Peter Viereck

Peter Robert Edwin Viereck (August 5, 1916 – May 13, 2006) was an American writer, poet, and professor of history at Mount Holyoke College. He won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 1949 for ''Terror and Decorum'', a collection of poetry.

. In 1978, Brodsky was awarded an honorary degree of Doctor of Letters

Doctor of Letters (D.Litt., Litt.D., Latin: ' or '), also termed Doctor of Literature in some countries, is a terminal degree in the arts, humanities, and social sciences. In the United States, at universities such as Drew University, the degree ...

at Yale University

Yale University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701, Yale is the List of Colonial Colleges, third-oldest institution of higher education in the United Stat ...

, and on 23 May 1979, he was inducted as a member of the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters

The American Academy of Arts and Letters is a 300-member honor society whose goal is to "foster, assist, and sustain excellence" in American literature, music, and art. Its fixed number membership is elected for lifetime appointments. Its headqua ...

. He moved to New York's Greenwich Village

Greenwich Village, or simply the Village, is a neighborhood on the west side of Lower Manhattan in New York City, bounded by 14th Street (Manhattan), 14th Street to the north, Broadway (Manhattan), Broadway to the east, Houston Street to the s ...

in 1980 and in 1981 received the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation

The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation is a private foundation that makes grants and impact investments to support non-profit organizations in approximately 117 countries around the world. It has an endowment of $7.6 billion and ...

"genius" award. He was also a recipient of The International Center in New York Award of Excellence. In 1986, his collection of essays, ''Less Than One'', won the National Book Critics Award

The National Book Critics Circle Awards are a set of annual American literary awards by the National Book Critics Circle (NBCC) to promote "the finest books and reviews published in English".

In 1987, he won the

Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; ; ) are awards administered by the Nobel Foundation and granted in accordance with the principle of "for the greatest benefit to humankind". The prizes were first awarded in 1901, marking the fifth anniversary of Alfred N ...

for Literature, the fifth Russian-born writer to do so. In an interview he was asked: "You are an American citizen who is receiving the Prize for Russian-language poetry. Who are you, an American or a Russian?" "I'm Jewish; a Russian poet, an English essayist – and, of course, an American citizen", he responded. The academy stated that they had awarded the prize for his "all-embracing authorship, imbued with clarity of thought and poetic intensity". It also called his writing "rich and intensely vital", characterized by "great breadth in time and space". It was "a big step for me, a small step for mankind", he joked. The prize coincided with the first legal publication in Russia of Brodsky's poetry as an exilé.

In 1991, Brodsky became Poet Laureate of the United States

A poet is a person who studies and creates poetry. Poets may describe themselves as such or be described as such by others. A poet may simply be the creator ( thinker, songwriter, writer, or author) who creates (composes) poems (oral or writt ...

. The Librarian of Congress

The librarian of Congress is the head of the Library of Congress, appointed by the president of the United States with the advice and consent of the United States Senate, for a term of ten years. The librarian of Congress also appoints and overs ...

said that Brodsky had "the open-ended interest of American life that immigrants have. This is a reminder that so much of American creativity is from people not born in America." His inauguration address was printed in ''Poetry Review

''The Poetry Review'' is the magazine of The Poetry Society, edited by the poet Wayne Holloway-Smith. Founded in 1912, shortly after the establishment of the Society, previous editors have included poets Muriel Spark, Adrian Henri, Andrew Mo ...

''. Brodsky held an honorary degree from the University of Silesia

The University of Silesia in Katowice () is an autonomous state-run university in Katowice, Silesia Province, Poland.

The university offers higher education and research facilities. It offers undergraduate, masters, and PhD degree programs, ...

in Poland and was an honorary member of the International Academy of Science. In 1995, Gleb Uspensky, a senior editor at the Russian publishing house, Vagrius, asked Brodsky to return to Russia for a tour, but he could not agree. For the last ten years of his life, Brodsky was under considerable pressure from those that regarded him as a "fortune maker". He was a greatly honored professor, was on first name terms with the heads of many large publishing houses and connected to the significant figures of American literary life. His friend Ludmila Shtern wrote that many Russian intellectuals in both Russia and America assumed his influence was unlimited, that a nod from him could secure them a book contract, a teaching post or a grant, that it was in his gift to assure a glittering career. A helping hand or a rejection of a petition for help could create a storm in Russian literary circles, which Shtern suggests became very personal at times. His position as a lauded émigré and Nobel Prize winner won him enemies and stoked resentment, the politics of which, she writes, made him feel "deathly tired" of it all toward the end.

In 1990, while teaching literature in France, Brodsky married a young student, Maria Sozzani, who has a Russian-Italian background; they had one daughter, Anna Brodsky, born in 1993.

Marina Basmanova lived in fear of the Soviet authorities until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991; only after this was their son Andrei Basmanov allowed to join his father in New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

New York may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* ...

. In the 1990s, Brodsky invited Andrei to visit him in New York for three months and they maintained a father-son relationship until Brodsky's death. Andrei married in the 1990s and had three children, all of whom were recognized and supported by Brodsky as his grandchildren; Marina Basmanova, Andrei, and Brodsky's grandchildren all live in Saint Petersburg, Russia. Andrei gave readings of his father's poetry in a documentary about Brodsky. The film contains Brodsky's poems dedicated to Marina Basmanova and written between 1961 and 1982.

Brodsky died of a heart attack aged 55, at his apartment in Brooklyn Heights

Brooklyn Heights is a residential neighborhood within the New York City borough of Brooklyn. The neighborhood is bounded by Old Fulton Street near the Brooklyn Bridge on the north, Cadman Plaza West on the east, Atlantic Avenue on the south ...

, a neighborhood of Brooklyn

Brooklyn is a Boroughs of New York City, borough of New York City located at the westernmost end of Long Island in the New York (state), State of New York. Formerly an independent city, the borough is coextensive with Kings County, one of twelv ...

, a borough of New York City

New York, often called New York City (NYC), is the most populous city in the United States, located at the southern tip of New York State on one of the world's largest natural harbors. The city comprises five boroughs, each coextensive w ...

, on 28 January 1996. He had open-heart surgery in 1979 and later two bypass operations, remaining in frail health following that time. He was buried in a non-Catholic section of the San Michele cemetery in Venice

Venice ( ; ; , formerly ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 islands that are separated by expanses of open water and by canals; portions of the city are li ...

, Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

, also the resting place of Ezra Pound

Ezra Weston Loomis Pound (30 October 1885 – 1 November 1972) was an List of poets from the United States, American poet and critic, a major figure in the early modernist poetry movement, and a Collaboration with Nazi Germany and Fascist Ita ...

and Igor Stravinsky

Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky ( – 6 April 1971) was a Russian composer and conductor with French citizenship (from 1934) and American citizenship (from 1945). He is widely considered one of the most important and influential 20th-century c ...

. In 1997, a plaque was placed on his former house in St. Petersburg, with his portrait in relief and the words "In this house from 1940 to 1972 lived the great Russian poet, Iosif Aleksandrovich Brodsky". Brodsky's close friend, the Nobel laureate Derek Walcott

Sir Derek Alton Walcott OM (23 January 1930 – 17 March 2017) was a Saint Lucian poet and playwright.

He received the 1992 Nobel Prize in Literature. His works include the Homeric epic poem '' Omeros'' (1990), which many critics view "as ...

, memorialized him in his collection ''The Prodigal'', in 2004.

Work

Brodsky is perhaps most known for his poetry collections, ''A Part of Speech'' (1977) and ''To Urania'' (1988), and the essay collection, ''Less Than One'' (1986), which won theNational Book Critics Circle Award

The National Book Critics Circle Awards are a set of annual American literary awards by the National Book Critics Circle (NBCC) to promote "the finest books and reviews published in English". Throughout his career he wrote in Russian and English, self-translating and working with eminent poet-translators.

Themes and forms

In his introduction to Brodsky's ''Selected Poems'' (New York and Harmondsworth, 1973), W. H. Auden described Brodsky as a traditionalistlyric poet

Modern lyric poetry is a formal type of poetry which expresses personal emotions or feelings, typically spoken in the first person.

The term for both modern lyric poetry and modern song lyrics derives from a form of Ancient Greek literature, t ...

fascinated by "encounters with nature, ... reflections upon the human condition, death, and the meaning of existence". He drew on wide-ranging themes, from Mexican and Caribbean literature to Roman poetry, mixing "the physical and the metaphysical, place and ideas about place, now and the past and the future". Critic Dinah Birch suggests that Brodsky's " first volume of poetry in English, ''Joseph Brodsky: Selected Poems (1973)'', shows that although his strength was a distinctive kind of dry, meditative soliloquy

A soliloquy (, from Latin 'alone' and 'to speak', ) is a speech in drama in which a character speaks their thoughts aloud, typically while alone on stage. It serves to reveal the character's inner feelings, motivations, or plans directly to ...

, he was immensely versatile and technically accomplished in a number of forms."

''To Urania: Selected Poems 1965–1985'' collected translations of older work with new work written during his American exile and reflect on themes of memory, home, and loss. His two essay collections consist of critical studies of such poets as Osip Mandelshtam

Osip Emilyevich Mandelstam (, ; – 27 December 1938) was a Russian and Soviet poet. He was one of the foremost members of the Acmeist school.

Osip Mandelstam was arrested during the repressions of the 1930s and sent into internal exile wi ...

, W.H. Auden, Thomas Hardy

Thomas Hardy (2 June 1840 – 11 January 1928) was an English novelist and poet. A Literary realism, Victorian realist in the tradition of George Eliot, he was influenced both in his novels and in his poetry by Romanticism, including the poetry ...

, Rainer Maria Rilke

René Karl Wilhelm Johann Josef Maria Rilke (4 December 1875 – 29 December 1926), known as Rainer Maria Rilke, was an Austrian poet and novelist. Acclaimed as an Idiosyncrasy, idiosyncratic and expressive poet, he is widely recognized as ...

and Robert Frost

Robert Lee Frost (March26, 1874January29, 1963) was an American poet. Known for his realistic depictions of rural life and his command of American Colloquialism, colloquial speech, Frost frequently wrote about settings from rural life in New E ...

, sketches of his own life, and those of contemporaries such as Akhmatova, Nadezhda Mandelshtam

Nadezhda Yakovlevna Mandelstam ( rus, Надежда Яковлевна Мандельштам, p=nɐˈdʲeʐdə ˈjakəvlʲɪvnə mənʲdʲɪlʲˈʂtam; []; 29 December 1980) was a Russian-Jewish writer, translator, educator, linguist, and memoi ...

, and Stephen Spender.

A recurring theme in Brodsky's writing is the relationship between the poet and society. In particular, Brodsky emphasized the power of literature to affect its audience positively and to develop the language and culture in which it is situated. He suggested that the Western literary tradition was in part responsible for the world having overcome the catastrophes of the twentieth century, such as Nazism

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During Hitler's rise to power, it was fre ...

, Communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

, and two World Wars

A world war is an international conflict that involves most or all of the world's major powers. Conventionally, the term is reserved for two major international conflicts that occurred during the first half of the 20th century, World War I (19 ...

. During his term as Poet Laureate, Brodsky promoted the idea of bringing the Anglo-American poetic heritage to a wider American audience by distributing free poetry anthologies to the public through a government-sponsored program. Librarian of Congress James Billington wrote:

This passion for promoting the seriousness and importance of poetry comes through in Brodsky's opening remarks as the U.S. Poet Laureate in October 1991. He said, "By failing to read or listen to poets, society dooms itself to inferior modes of articulation, those of the politician, the salesman or the charlatan. ... In other words, it forfeits its own evolutionary potential. For what distinguishes us from the rest of the animal kingdom is precisely the gift of speech. ... Poetry is not a form of entertainment and in a certain sense not even a form of art, but it is our anthropological, genetic goal, our evolutionary, linguistic beacon." This sentiment is echoed throughout his work. In interview with Sven Birkerts

Sven Birkerts (born 21 September 1951) is an American essayist and literary critic. He is best known for his book ''The Gutenberg Elegies'' (1994), which posits a decline in reading due to the overwhelming advances of the Internet and other tec ...

in 1979, Brodsky reflected:

Influences

Librarian of Congress Dr James Billington, wrote: Brodsky also was deeply influenced by the Englishmetaphysical

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that examines the basic structure of reality. It is traditionally seen as the study of mind-independent features of the world, but some theorists view it as an inquiry into the conceptual framework of h ...

poets from John Donne

John Donne ( ; 1571 or 1572 – 31 March 1631) was an English poet, scholar, soldier and secretary born into a recusant family, who later became a clergy, cleric in the Church of England. Under Royal Patronage, he was made Dean of St Paul's, D ...

to Auden. Many works were dedicated to other writers such as Tomas Venclova

Tomas Venclova (born 11 September 1937) is a Lithuanian poet, prose writer, scholar, philologist and translator of literature. He is one of the five founding members of the Lithuanian Helsinki Group. In 1977, following his dissident activities, ...

, Octavio Paz

Octavio Paz Lozano (March 31, 1914 – April 19, 1998) was a Mexican poet and diplomat. For his body of work, he was awarded the 1977 Jerusalem Prize, the 1981 Miguel de Cervantes Prize, the 1982 Neustadt International Prize for Literature, a ...

, Robert Lowell

Robert Traill Spence Lowell IV (; March 1, 1917 – September 12, 1977) was an American poet. He was born into a Boston Brahmin family that could trace its origins back to the ''Mayflower''. His family, past and present, were important subjects ...

, Derek Walcott

Sir Derek Alton Walcott OM (23 January 1930 – 17 March 2017) was a Saint Lucian poet and playwright.

He received the 1992 Nobel Prize in Literature. His works include the Homeric epic poem '' Omeros'' (1990), which many critics view "as ...

, and Benedetta Craveri.

Brodsky's work is seen to have been vitally enhanced by the work of renowned translators. ''A Part of Speech'' (New York and Oxford, 1980), his second major collection in English, includes translations by Anthony Hecht

Anthony Evan Hecht (January 16, 1923 – October 20, 2004) was an American poet. His work combined a deep interest in form with a passionate desire to confront the horrors of 20th century history, with the Second World War, in which he fought, an ...

, Howard Moss

Howard Moss (January 22, 1922 – September 16, 1987) was an American poet, dramatist and critic. He was poetry editor of ''The New Yorker'' magazine from 1948 until his death and he won the National Book Award in 1972 for ''Selected Poems''.

B ...

, Derek Walcott

Sir Derek Alton Walcott OM (23 January 1930 – 17 March 2017) was a Saint Lucian poet and playwright.

He received the 1992 Nobel Prize in Literature. His works include the Homeric epic poem '' Omeros'' (1990), which many critics view "as ...

, and Richard Wilbur

Richard Purdy Wilbur (March 1, 1921 – October 14, 2017) was an American poet and literary translator. One of the foremost poets, along with his friend Anthony Hecht, of the World War II generation, Wilbur's work, often employing rhyme, and c ...

. Critic and poet Henri Cole

Henri Cole (born May 9, 1956) is an American poet, who has published many collections of poetry and a memoir. His books have been translated into French, Spanish, Italian, German, and Arabic.

Biography

Henri Cole was born in Fukuoka, Japan, to a ...

notes that Brodsky's "own translations have been criticized for turgidness, lacking a native sense of musicality."

After the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014, Brodsky's controversial poem On the Independence of Ukraine (Russian: На независимость Украины) from the early 1990s (which he did not publish but publicly recited) was repeatedly picked up by state-affiliated Russian media and declared Poem of the Year. The Estate of Joseph Brodsky was subsequently prosecuting some websites publishing the poem, demanding its removal.

Awards and honors

*1978 – Honorary degree ofDoctor of Letters

Doctor of Letters (D.Litt., Litt.D., Latin: ' or '), also termed Doctor of Literature in some countries, is a terminal degree in the arts, humanities, and social sciences. In the United States, at universities such as Drew University, the degree ...

, Yale University

Yale University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701, Yale is the List of Colonial Colleges, third-oldest institution of higher education in the United Stat ...

*1979 – Fellowship of American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters

The American Academy of Arts and Letters is a 300-member honor society whose goal is to "foster, assist, and sustain excellence" in American literature, music, and art. Its fixed number membership is elected for lifetime appointments. Its headqua ...

*1981 – John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation

The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation is a private foundation that makes grants and impact investments to support non-profit organizations in approximately 117 countries around the world. It has an endowment of $7.6 billion and ...

award

*1986 – Honorary doctorate of literature from Oxford University

The University of Oxford is a collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the second-oldest continuously operating u ...

*The International Center in New York's Award of Excellence

*1986 – National Book Critics Award

The National Book Critics Circle Awards are a set of annual American literary awards by the National Book Critics Circle (NBCC) to promote "the finest books and reviews published in English".Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; ; ) are awards administered by the Nobel Foundation and granted in accordance with the principle of "for the greatest benefit to humankind". The prizes were first awarded in 1901, marking the fifth anniversary of Alfred N ...

*1989 – Honorary doctorate from the University of Essex

The University of Essex is a public university, public research university in Essex, England. Established by royal charter in 1965, it is one of the original plate glass university, plate glass universities. The university comprises three camp ...

*1989 – Honorary degree from Dartmouth College

Dartmouth College ( ) is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Hanover, New Hampshire, United States. Established in 1769 by Eleazar Wheelock, Dartmouth is one of the nine colonial colleges chartered before the America ...

*1991 – honorary doctorate

An honorary degree is an academic degree for which a university (or other degree-awarding institution) has waived all of the usual requirements. It is also known by the Latin phrases ''honoris causa'' ("for the sake of the honour") or '' ad hon ...

from the Faculty of Humanities at Uppsala University

Uppsala University (UU) () is a public university, public research university in Uppsala, Sweden. Founded in 1477, it is the List of universities in Sweden, oldest university in Sweden and the Nordic countries still in operation.

Initially fou ...

, Sweden

Sweden, formally the Kingdom of Sweden, is a Nordic countries, Nordic country located on the Scandinavian Peninsula in Northern Europe. It borders Norway to the west and north, and Finland to the east. At , Sweden is the largest Nordic count ...

*1991 – United States Poet Laureate

The poet laureate consultant in poetry to the Library of Congress, commonly referred to as the United States poet laureate, serves as the official poet of the United States. During their term, the poet laureate seeks to raise the national consc ...

*1991 – Struga Poetry Evenings Golden Wreath Award

Struga Poetry Evenings (SPE) (, СВП; tr. ''Struški večeri na poezijata'', ''SVP'') is an international poetry festival held annually in Struga, North Macedonia. During the several decades of its existence, the Festival has awarded its most ...

*1993 – Honorary degree from the University of Silesia

The University of Silesia in Katowice () is an autonomous state-run university in Katowice, Silesia Province, Poland.

The university offers higher education and research facilities. It offers undergraduate, masters, and PhD degree programs, ...

in Poland

*Honorary member of the International Academy of Science, Munich

Works

Poetry collections

* 1967: ''Elegy forJohn Donne

John Donne ( ; 1571 or 1572 – 31 March 1631) was an English poet, scholar, soldier and secretary born into a recusant family, who later became a clergy, cleric in the Church of England. Under Royal Patronage, he was made Dean of St Paul's, D ...

and Other Poems'', selected, translated, and introduced by Nicholas William Bethell, London: Longman

* 1968: ''Velka elegie'', Paris: Edice Svedectvi

* 1972: ''Poems'', Ann Arbor, Michigan: Ardis

* 1973: ''Selected Poems'', translated from the Russian by George L. Kline. New York: Harper & Row

* 1977: ''A Part of Speech''

* 1977: ''Poems and Translations'', Keele: University of Keele

Keele University is a public research university in Keele, approximately from Newcastle-under-Lyme, Staffordshire, England. Founded in 1949 as the University College of North Staffordshire, it was granted university status by Royal Charter as ...

* 1980: ''A Part of Speech'', New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux

* 1981: ''Verses on the Winter Campaign 1980'', translation by Alan Myers.–London: Anvil Press

* 1988: ''To Urania: Selected Poems, 1965–1985'', New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux

* 1996: ''So Forth: Poems'', New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux

* 1999: ''Discovery'', New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux

* 2000: ''Collected Poems in English, 1972–1999'', edited by Ann Kjellberg, New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux

* 2001: ''Nativity Poems'', translated by Melissa Green–New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux

* 2020: ''Selected Poems, 1968–1996'', edited by Ann Kjellberg, New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux

Essay and interview collections

* 1986: '' Less Than One: Selected Essays'', New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux. (Winner of theNational Book Critics Circle Award

The National Book Critics Circle Awards are a set of annual American literary awards by the National Book Critics Circle (NBCC) to promote "the finest books and reviews published in English".Cynthia L. Haven. Jackson, Miss.: University Press of Mississippi Literary Conversations Series.

"Troika: Russia's westerly poetry in three orchestral song cycles"

Rideau Rouge Records, ASIN: B005USB24A, 2011.

Joseph Brodsky poetry

'The birds of paradise sing without a needing a supple branch': Joseph Brodsky and the Poetics of Exile

''Cordite Poetry Review''

Profile, poems and audio files

from the

Brodsky Biography and bibliography

Written in Stone

– Burial locations of literary figures. * Joseph Brodsky Papers. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

Brodsky speaks about his life, with translated readings by Frances Horowitz

- a British Library sound recording

*

Joseph Brodsky Collection

a

Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, & Rare Book Library, Emory University

{{DEFAULTSORT:Brodsky, Joseph 1940 births 1996 deaths Nobel laureates in Literature American Nobel laureates Russian Nobel laureates Soviet Nobel laureates 20th-century American poets 20th-century Russian poets Exophonic writers Jewish American poets American male poets American poets laureate American people of Russian-Jewish descent American writers of Russian descent Burials at Isola di San Michele Fellows of Clare Hall, Cambridge Alumni of Clare Hall, Cambridge MacArthur Fellows Mount Holyoke College faculty Columbia University faculty New York University faculty Struga Poetry Evenings Golden Wreath laureates Writers from Saint Petersburg Jewish Russian writers Russian male poets Soviet dissidents Soviet emigrants to the United States Soviet expellees Soviet Jews Soviet prisoners and detainees Stateless people University of Michigan faculty The New Yorker people Denaturalized citizens of the Soviet Union English–Russian translators 20th-century Russian translators Translators from English American male essayists 20th-century American essayists People from Brooklyn Heights 20th-century American male writers Members of the American Academy of Arts and Letters National Book Critics Circle Award winners

Plays

* 1989: ''Marbles: a Play in Three Acts'', translated by Alan Myers with Joseph Brodsky. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux * 1991: ''Democracy!'' inGranta

''Granta'' is a literary magazine and publisher in the United Kingdom whose mission centres on its "belief in the power and urgency of the story, both in fiction and non-fiction, and the story's supreme ability to describe, illuminate and make ...

30: New Europe, translated by Alan Myers and Joseph Brodsky.

In film

*2008

2008 was designated as:

*International Year of Languages

*International Year of Planet Earth

*International Year of the Potato

*International Year of Sanitation

The Great Recession, a worldwide recession which began in 2007, continued throu ...

– ''A Room And A Half'' (, Poltory komnaty ili sentimental'noe puteshestvie na rodinu), feature film directed by Andrei Khrzhanovsky

Andrei Yurievich Khrzhanovsky (; born 30 November 1939 in Moscow) is a Soviet and Russian animator, documentary filmmaker, writer and producer known for making art films. He is the father of director Ilya Khrzhanovsky. Married to philologist, e ...

; a fictionalized account of Brodsky's life.

* 2015

2015 was designated by the United Nations as:

* International Year of Light

* International Year of Soil __TOC__

Events

January

* January 1 – Lithuania officially adopts the euro as its currency, replacing the litas, and becomes ...

– ''Brodsky is not a Poet'' (, Brodskiy ne poet), documentary film by Ilia Belov on Brodsky's stay in the States.

* 2018

Events January

* January 1 – Bulgaria takes over the Presidency of the Council of the European Union, after the Estonian presidency.

* January 4 – SPLM-IO rebels loyal to Chan Garang Lual start a raid against Juba, capital of ...

– '' Dovlatov'' (), biographical film about writer Sergei Dovlatov

Sergei Donatovich Dovlatov (; 1941 1990) was a Soviet journalist and writer. Internationally, he is one of the most popular Russian writers of the late 20th century.

Biography

Dovlatov was born on 3 September 1941 in Ufa, the capital of Bas ...

(who was Joseph Brodsky's friend) directed by Aleksei German-junior; film is set in 1971 in Leningrad shortly before Brodsky's emigration and Brodsky plays an important role.

In music

The 2011 contemporary classical album ''Troika

Troika or troyka (from Russian тройка, meaning 'a set of three' or the digit '3') may refer to:

* Troika (driving), a traditional Russian harness driving combination, a cultural icon of Russia

Politics

* Triumvirate, a political regime rul ...

'' includes Eskender Bekmambetov's critically acclaimed, song cycle "there ...", set to five of Joseph's Brodsky's Russian-language poems and his own translations of the poems into English.Rideau Rouge Records, ASIN: B005USB24A, 2011.

Victoria Poleva

Victoria Vita Polyova (; born September 11, 1962) is a Ukrainian composer.

Biography

Born on September 11, 1962, in Kyiv, Ukraine, daughter of composer Valery Polyovyj (1927–1986). Graduate of Kyiv Conservatory (class of composition with Pr ...

wrote ''Summer music'' (2008), a chamber cantata based on the verses by Brodsky for violin solo, children choir and Strings and ''Ars moriendi'' (1983–2012), 22 monologues about death for soprano and piano (two monologues based on the verses by Brodsky ("Song" and "Empty circle").

Collections in Russian

* 1965: ''Stikhotvoreniia i poemy'',Washington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

: Inter-Language Literary Associates

* 1970: ''Ostanovka v pustyne'', New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

New York may also refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* ...

: Izdatel'stvo imeni Chekhova (Rev. ed. Ann Arbor, Mich.: Ardis, 1989)

* 1977: ''Chast' rechi: Stikhotvoreniia 1972–76'', Ann Arbor

Ann Arbor is a city in Washtenaw County, Michigan, United States, and its county seat. The 2020 United States census, 2020 census recorded its population to be 123,851, making it the List of municipalities in Michigan, fifth-most populous cit ...

, Mich.: Ardis

* 1977: ''Konets prekrasnoi epokhi : stikhotvoreniia 1964–71'', Ann Arbor, Mich.: Ardis

* 1977: ''V Anglii'', Ann Arbor, Mich.: Ardis

* 1982: ''Rimskie elegii'', New York: Russica

* 1983: ''Novye stansy k Avguste : stikhi k M.B., 1962–1982'', Ann Arbor, Mich.: Ardis

* 1984: ''Mramor'', Ann Arbor, Mich.: Ardis

* 1984: ''Uraniia : Novaia kniga stikhov'', Ann Arbor, Mich.: Ardis

* 1989: ''Ostanovka v pustyne'', revised edition, Ann Arbor, Mich.: Ardis, 1989 (original edition: New York: Izdatel'stvo imeni Chekhova, 1970)

* 1990: ''Nazidanie : stikhi 1962–1989'', Leningrad: Smart

* 1990: ''Chast' rechi : Izbrannye stikhi 1962–1989'', Moscow: Khudozhestvennaia literatura

* 1990: ''Osennii krik iastreba : Stikhotvoreniia 1962–1989'', Leningrad: KTP LO IMA Press

* 1990: ''Primechaniia paporotnika'', Bromma, Sweden : Hylaea

* 1991: ''Ballada o malen'kom buksire'', Leningrad: Detskaia literatura

* 1991: ''Kholmy : Bol'shie stikhotvoreniia i poemy'', Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg, formerly known as Petrograd and later Leningrad, is the List of cities and towns in Russia by population, second-largest city in Russia after Moscow. It is situated on the Neva, River Neva, at the head of the Gulf of Finland ...

: LP VTPO "Kinotsentr"

* 1991: ''Stikhotvoreniia'', Tallinn: Eesti Raamat

* 1992: ''Naberezhnaia neistselimykh: Trinadtsat' essei'', Moscow

Moscow is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Russia by population, largest city of Russia, standing on the Moskva (river), Moskva River in Central Russia. It has a population estimated at over 13 million residents with ...

: Slovo

* 1992: ''Rozhdestvenskie stikhi'', Moscow: Nezavisimaia gazeta (revised edition in 1996)

* 1992–1995: ''Sochineniia'', Saint Petersburg: Pushkinskii fond, 1992–1995, four volumes

* 1992: ''Vspominaia Akhmatovu / Joseph Brodsky, Solomon Volkov'', Moscow: Nezavisimaia gazeta

* 1992: ''Forma vremeni : stikhotvoreniia, esse, p'esy'', Minsk: Eridan, two volumes

* 1993: ''Kappadokiia''.–Saint Petersburg

* 1994: ''Persian Arrow/Persidskaia strela'', with etchings by Edik Steinberg.–Verona: * Edizione d'Arte Gibralfaro & ECM

* 1995: ''Peresechennaia mestnost ': Puteshestviia s kommentariiami'', Moscow: Nezavisimaia gazeta

* 1995: ''V okrestnostiakh Atlantidy : Novye stikhotvoreniia'', Saint Petersburg: Pushkinskii fond

* 1996: ''Peizazh s navodneniem'', compiled by Aleksandr Sumerkin. Dana Point

Dana Point () is a city located in southern Orange County, California, United States. The population was 33,107 at the 2020 census. It has one of the few harbors along the Orange County coast; with ready access via State Route 1, it is a popu ...

, Cal.: Ardis

* 1996: ''Rozhdestvenskie stikhi'', Moscow: Nezavisimaia gazeta, revised edition of a work originally published in 1992

* 1997: ''Brodskii o Tsvetaevoi'', Moscow: Nezavisimaia gazeta

* 1998: ''Pis'mo Goratsiiu'', Moscow: Nash dom

* 1996 and after: ''Sochineniia'', Saint Petersburg: Pushkinskii fond, eight volumes

* 1999: ''Gorbunov i Gorchakov'', Saint Petersburg: Pushkinskii fond

* 1999: ''Predstavlenie : novoe literaturnoe obozrenie'', Moscow

* 2000: ''Ostanovka v pustyne'', Saint Petersburg: Pushkinskii fond

* 2000: ''Chast' rechi'', Saint Petersburg: Pushkinskii fond

* 2000: ''Konets prekrasnoi epokhi'', Saint Petersburg: Pushkinskii fond

* 2000: ''Novye stansy k Avguste'', Saint Petersburg: Pushkinskii fond

* 2000: ''Uraniia'', Saint Petersburg: Pushkinskii fond

* 2000: ''Peizazh s navodneniem'', Saint Petersburg: Pushkinskii fond

* 2000: ''Bol'shaia kniga interv'iu'', Moscow: Zakharov

* 2001: ''Novaia Odisseia : Pamiati Iosifa Brodskogo'', Moscow: Staroe literaturnoe obozrenie

* 2001: ''Peremena imperii : Stikhotvoreniia 1960–1996'', Moscow: Nezavisimaia gazeta

* 2001: ''Vtoroi vek posle nashei ery : dramaturgija Iosifa Brodskogo'', Saint Petersburg: Zvezda

See also

*List of Jewish Nobel laureates

Of the 965 individual recipients of the Nobel Prize and the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences between 1901 and 2023, at least 216 have been Jews or people with at least one Jewish parent, representing 22% of all recipients. Jews constitut ...

* List of Russian Nobel laureates

Notes

References

Works cited

* * * * * * * *Further reading

* *Loseff, Lev (2010) ''Joseph Brodsky: a Literary Life'', Yale University Press (New Haven, CT) *Speh, Alice J (1996) ''The Poet as Traveler: Joseph Brodsky in Mexico and Rome'', Peter Lang (New York, NY) *Volkov, Solomon (1998) ''Conversations with Joseph Brodsky: A Poet's Journey Through the 20th Century'', translated by Marian Schwartz, The Free Press, (New York, NY)Further reading

* * Mackie, Alastair (1981), a review of ''A Part of Speech'', in Murray, Glen (ed.), ''Cencrastus

''Cencrastus'' was a magazine devoted to Scottish and international literature, arts and affairs, founded after the Referendum of 1979 by students, mainly of Scottish literature, at Edinburgh University, and with support from Cairns Craig, then a ...

'' No. 5, Summer 1981, pp. 50 & 51

External links

Joseph Brodsky poetry

'The birds of paradise sing without a needing a supple branch': Joseph Brodsky and the Poetics of Exile

''Cordite Poetry Review''

Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is a research library in Washington, D.C., serving as the library and research service for the United States Congress and the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It also administers Copyright law o ...

, obituary.

*

PBS

The Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) is an American public broadcaster and non-commercial, free-to-air television network based in Arlington, Virginia. PBS is a publicly funded nonprofit organization and the most prominent provider of educat ...

(US)

Profile, poems and audio files

from the

Academy of American Poets

The Academy of American Poets is a national, member-supported organization that promotes poets and the art of poetry. The nonprofit organization was incorporated in the state of New York in 1934. It fosters the readership of poetry through outrea ...

.

Brodsky Biography and bibliography

Poetry Foundation

The Poetry Foundation is a United States literary society that seeks to promote poetry and lyricism in the wider culture. It was formed from ''Poetry'' magazine, which it continues to publish, with a 2003 gift of $200 million from philanthrop ...

(US)

*

*

Written in Stone

– Burial locations of literary figures. * Joseph Brodsky Papers. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

Brodsky speaks about his life, with translated readings by Frances Horowitz

- a British Library sound recording

*

Joseph Brodsky Collection

a

Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, & Rare Book Library, Emory University

{{DEFAULTSORT:Brodsky, Joseph 1940 births 1996 deaths Nobel laureates in Literature American Nobel laureates Russian Nobel laureates Soviet Nobel laureates 20th-century American poets 20th-century Russian poets Exophonic writers Jewish American poets American male poets American poets laureate American people of Russian-Jewish descent American writers of Russian descent Burials at Isola di San Michele Fellows of Clare Hall, Cambridge Alumni of Clare Hall, Cambridge MacArthur Fellows Mount Holyoke College faculty Columbia University faculty New York University faculty Struga Poetry Evenings Golden Wreath laureates Writers from Saint Petersburg Jewish Russian writers Russian male poets Soviet dissidents Soviet emigrants to the United States Soviet expellees Soviet Jews Soviet prisoners and detainees Stateless people University of Michigan faculty The New Yorker people Denaturalized citizens of the Soviet Union English–Russian translators 20th-century Russian translators Translators from English American male essayists 20th-century American essayists People from Brooklyn Heights 20th-century American male writers Members of the American Academy of Arts and Letters National Book Critics Circle Award winners