Jonathan Sisson on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Jonathan Sisson (1690 – 1747) was a prominent English instrument maker, the inventor of the modern

In 1732 Sisson was selected to make a brass octant to John Hadley's new design. The instrument proved reliable and easy to use in

In 1732 Sisson was selected to make a brass octant to John Hadley's new design. The instrument proved reliable and easy to use in

Sisson made large astronomical instruments that were used by several European observatories.

He made rigid wall-mounted brass quadrants with radii of .

Graham employed Sisson to make the Royal Observatory's mural quadrant.

One of Sisson's instruments was loaned by Pierre Lemonnier to the Berlin Academy, where it was used to supplement observations at the

Sisson made large astronomical instruments that were used by several European observatories.

He made rigid wall-mounted brass quadrants with radii of .

Graham employed Sisson to make the Royal Observatory's mural quadrant.

One of Sisson's instruments was loaned by Pierre Lemonnier to the Berlin Academy, where it was used to supplement observations at the

theodolite

A theodolite () is a precision optical instrument for measuring angles between designated visible points in the horizontal and vertical planes. The traditional use has been for land surveying, but it is also used extensively for building and ...

with a sighting telescope for surveying

Surveying or land surveying is the technique, profession, art, and science of determining the terrestrial two-dimensional or three-dimensional positions of points and the distances and angles between them. A land surveying professional is ...

, and a leading maker of astronomical instruments.

Career

Jonathan Sisson was born inLincolnshire

Lincolnshire (abbreviated Lincs.) is a county in the East Midlands of England, with a long coastline on the North Sea to the east. It borders Norfolk to the south-east, Cambridgeshire to the south, Rutland to the south-west, Leicestershir ...

around 1690.

He was apprenticed to George Graham (1673–1751), then became independent in 1722.

He remained an associate of Graham and of the instrument maker John Bird (1709–1776).

All three were recommended by the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, r ...

and received some funding from the state,

which recognised the value of instruments both to the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by Kingdom of England, English and Kingdom of Scotland, Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were foug ...

and to merchant ships.

After striking out on his own in 1722 and opening a business in the Strand in London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

, Sisson gained a reputation for making highly accurate arcs and circles,

and for the altazimuth theodolites that he made to his own design.

He became a well-known maker of optical and mathematical instruments.

In 1729 Sisson was appointed mathematical instrument maker to Frederick, Prince of Wales

Frederick, Prince of Wales, (Frederick Louis, ; 31 January 170731 March 1751), was the eldest son and heir apparent of King George II of Great Britain. He grew estranged from his parents, King George and Queen Caroline. Frederick was the fat ...

.

His apprentice John Dabney, junior, was an early instrument maker in the American colonies, who arrived in Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the capital city, state capital and List of municipalities in Massachusetts, most populous city of the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financ ...

in 1739.

Sisson's son, Jeremiah Sisson

Jeremiah Sisson (1720-1783) was an English instrument maker who became one of the leaders of his profession in London.

Jeremiah Sisson was the son of Jonathan Sisson, also a respected instrument maker, who trained him in the craft.

Sisson worked ...

(1720–1783), also made instruments, and became one of the leading instrument makers in London.

Sisson also employed John Bird, his co-worker under Graham, who became another leading supplier of instruments to the Royal Observatory.

His brother-in-law, Benjamin Ayres, apprenticed under Sisson and then set up shop in Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , , , lit. ''The Dam on the River Amstel'') is the Capital of the Netherlands, capital and Municipalities of the Netherlands, most populous city of the Netherlands, with The Hague being the seat of government. It has a population ...

in 1743.

Jonathan Sisson died during the night on 13 June 1747.

An old friend recording the fact in his diary described him as a man of extraordinary genius in making mathematical instruments.

Instruments

Sisson made portablesundial

A sundial is a horological device that tells the time of day (referred to as civil time in modern usage) when direct sunlight shines by the apparent position of the Sun in the sky. In the narrowest sense of the word, it consists of a fl ...

s with a compass in the base for use in aligning the instrument with the Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's surf ...

's axis.

He also constructed barometer

A barometer is a scientific instrument that is used to measure air pressure in a certain environment. Pressure tendency can forecast short term changes in the weather. Many measurements of air pressure are used within surface weather analysis ...

s.

A model Newcomen steam engine

A steam engine is a heat engine that performs mechanical work using steam as its working fluid. The steam engine uses the force produced by steam pressure to push a piston back and forth inside a cylinder. This pushing force can be ...

was given to Sisson to repair, but he was unable to make it work.

However, Sisson became renowned for his instruments for surveying, navigation, the measurement of lengths and astronomy.

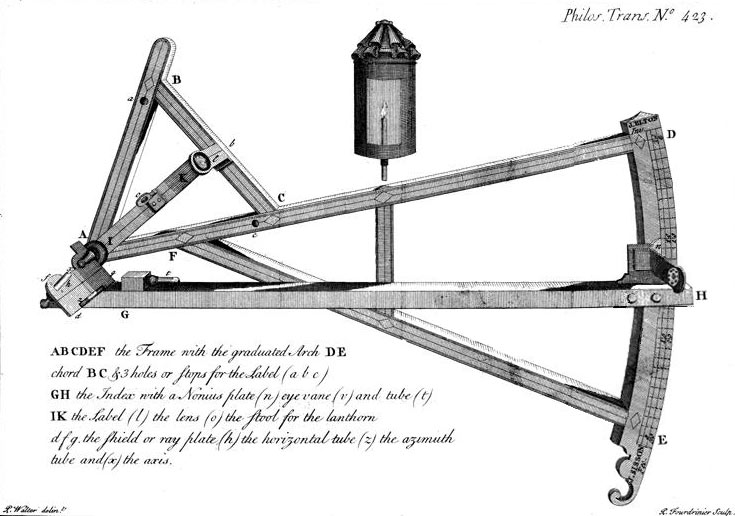

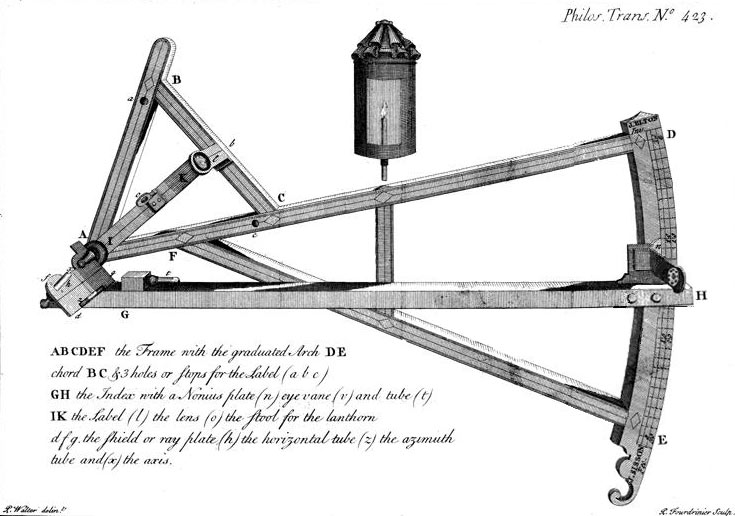

Surveying and navigation

Sisson designed an early type of surveyor's level, the Y-level (or Wye level), where a telescope rests in Y-shaped bearings and is removable. The level incorporates a bubble tube and a large magnetic compass. John Grundy, Sr. (c. 1696–1748), land surveyor and civil engineer, obtained a precision level with telescopic sights from Sisson before 1734. The instrument was accurate to less than in . Sisson initially built theodolites with plain sights, then made the key innovation of introducing a telescopic sight. Sisson's theodolites have some similarity to earlier instruments such as that built by Leonard Digges, but in many ways are the same as modern devices. The base plate incorporatesspirit level

A spirit level, bubble level, or simply a level, is an instrument designed to indicate whether a surface is horizontal (level) or vertical ( plumb). Different types of spirit levels may be used by carpenters, stonemasons, bricklayers, oth ...

s and screws, so it can be leveled, and has a compass pointing to magnetic north

The north magnetic pole, also known as the magnetic north pole, is a point on the surface of Earth's Northern Hemisphere at which the planet's magnetic field points vertically downward (in other words, if a magnetic compass needle is allowed ...

.

The circles are read using a vernier scale, accurate to about 5 minutes of arc.

The design of his 1737 theodolite is the basis for modern instruments of this type.

The location of the boundary between the provinces of New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

and New Jersey

New Jersey is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic States, Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern United States, Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York (state), New York; on the ea ...

was long a source of violent disputes. In 1743, it was agreed that the line would run from the west bank of the Hudson River

The Hudson River is a river that flows from north to south primarily through eastern New York. It originates in the Adirondack Mountains of Upstate New York and flows southward through the Hudson Valley to the New York Harbor between Ne ...

at the forty-first parallel to the bend of the Delaware River opposite today's Matamoras, Pennsylvania.

There was no instrument in the Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Founded in the 17th and 18th cent ...

accurate enough to fix the location of the parallel precisely, so a request was forwarded to the Royal Society in London, and then to George Graham. Graham could not accept the commission due to other work, and recommended Sisson.

The radius quadrant built by Sisson was found to be accurate within of a degree, a very impressive level of accuracy.

The components of the instrument arrived in New Jersey in 1745 and assembly began the next year.

After being used to determine the boundary and settle the dispute, the quadrant continued to be used for surveys in New Jersey and New York for many years.

In 1732 Sisson was selected to make a brass octant to John Hadley's new design. The instrument proved reliable and easy to use in

In 1732 Sisson was selected to make a brass octant to John Hadley's new design. The instrument proved reliable and easy to use in sea trial

A sea trial is the testing phase of a watercraft (including boats, ships, and submarines). It is also referred to as a " shakedown cruise" by many naval personnel. It is usually the last phase of construction and takes place on open water, and ...

s, even though weather conditions were poor, and was clearly an improvement over the cross-staff and backstaff.

Joan Gideon Loten, an amateur scientist, owned an octant made by Sisson that he took with him on his assignment as Governor of the Dutch East Indian possession of Makassar

Makassar (, mak, ᨆᨀᨔᨑ, Mangkasara’, ) is the capital of the Indonesian province of South Sulawesi. It is the largest city in the region of Eastern Indonesia and the country's fifth-largest urban center after Jakarta, Surabaya, ...

(1744–1750). The instrument would have had considerable value at the time. He may have acquired it via Gerard Arnout Hasselaer

Gerard Arnout Hasselaer (20 February 1698, Amsterdam - 12 July 1766, Heemstede) was a burgomaster and counsellor of the city of Amsterdam, and a Director of the Dutch East India Company.

Some historians have said he was an able regent.

Others have ...

, the regent

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state ''pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy, ...

of Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , , , lit. ''The Dam on the River Amstel'') is the Capital of the Netherlands, capital and Municipalities of the Netherlands, most populous city of the Netherlands, with The Hague being the seat of government. It has a population ...

, who was in contact with Sisson and with his Amsterdam-based brother-in-law Benjamin Ayres, also an instrument maker.

Measurement of length

Sisson was well known for the exact division of his scales, for measuring lengths. In 1742 George Graham, who was aFellow of the Royal Society

Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS, ForMemRS and HonFRS) is an award granted by the judges of the Royal Society of London to individuals who have made a "substantial contribution to the improvement of natural knowledge, including mathematic ...

, asked Sisson to prepare two substantial brass rods, well-planed and squared and each about long, on which Graham very carefully laid off the length of the standard English yard held in the Tower of London

The Tower of London, officially His Majesty's Royal Palace and Fortress of the Tower of London, is a historic castle on the north bank of the River Thames in central London. It lies within the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, which is sepa ...

.

Graham also asked Sisson to prepare "2 excellent brass scales of 6 inches each, on both of which one inch is curiously divided by diagonal lines, and fine points, into 500 equal parts." These scales and other standard scale The standard scale is a system in Commonwealth law whereby financial criminal penalties ( fines) in legislation have maximum levels set against a standard scale. Then, when inflation makes it necessary to increase the levels of the fines the legisla ...

s and weights were exchanged in 1742 between the Royal Society and the Royal Academy of Sciences in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. ...

, so each society had copies of the standard measures for the other country.

In 1785 the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, r ...

heard a description of a brass standard scale made by Sisson under Graham's direction. The scale showed the length of the British standard yard of from the Tower of London, and the lengths of the Exchequer's yard and the French half-toise. When compared to the Royal Society's standard yard at a temperature of it was found to be precisely the same length, while it was almost longer than the Exchequer yard.

Astronomy

Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( af, Kaap die Goeie Hoop ) ;''Kaap'' in isolation: pt, Cabo da Boa Esperança is a rocky headland on the Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is ...

by Nicolas Louis de Lacaille

Abbé Nicolas-Louis de Lacaille (; 15 March 171321 March 1762), formerly sometimes spelled de la Caille, was a French astronomer and geodesist who named 14 out of the 88 constellations. From 1750 to 1754, he studied the sky at the Cape of Good ...

of the lunar parallax

The most important fundamental distance measurements in astronomy come from trigonometric parallax. As the Earth orbits the Sun, the position of nearby stars will appear to shift slightly against the more distant background. These shifts are an ...

.

Pope Benedict XIV

Pope Benedict XIV ( la, Benedictus XIV; it, Benedetto XIV; 31 March 1675 – 3 May 1758), born Prospero Lorenzo Lambertini, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 17 August 1740 to his death in May 1758. Pope Be ...

arranged for astronomical instruments purchased from Jonathan Sisson to be installed in the ''Specola'' observatory of the Academy of Sciences of Bologna Institute

The Academy of Sciences of the Institute of Bologna (''Accademia delle Scienze dell'Istituto di Bologna'') is an academic society in Bologna, Italy, that was founded in 1690 and prospered in the Age of Enlightenment. Today it is closely associated ...

.

With the help of Thomas Derham, the British ambassador in Rome, and of the Royal Society, Sisson was commissioned to supply a transit telescope

In astronomy, a transit instrument is a small telescope with extremely precisely graduated mount used for the precise observation of star positions. They were previously widely used in astronomical observatories and naval observatories to measu ...

, a mural quadrant and a portable quadrant, which were dispatched by sea to Leghorn and installed in 1741 in the Institute's observatory.

The arch and the latticework

__NOTOC__

Latticework is an openwork framework consisting of a criss-crossed pattern of strips of building material, typically wood or metal. The design is created by crossing the strips to form a grid or weave.

Latticework may be functional &n ...

frame of the mural quadrant were both of brass, the first of this type.

A discussion of equatorial instrument

An equatorial mount is a mount for instruments that compensates for Earth's rotation by having one rotational axis, the polar axis, parallel to the Earth's axis of rotation. This type of mount is used for astronomical telescopes and cameras. The ...

s published in 1793 said that Sisson was the inventor of the modern version of that instrument, which had been incorrectly attributed to Mr. Short. Sisson made his first equatorial instrument of this design for Archibald, Lord Ilay, and it was now held by the college at Aberdeen

Aberdeen (; sco, Aiberdeen ; gd, Obar Dheathain ; la, Aberdonia) is a city in North East Scotland, and is the third most populous city in the country. Aberdeen is one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas (as Aberdeen City), ...

. The instrument was "very elegantly constructed", with an azimuth circle about across. Mr Short ordered Sisson's son Jeremiah to add reflecting telescope

A reflecting telescope (also called a reflector) is a telescope that uses a single or a combination of curved mirrors that reflect light and form an image. The reflecting telescope was invented in the 17th century by Isaac Newton as an alternati ...

s to the instruments and to use endless screws to move the circles,

but this design proved inferior to Jonathon Sisson's original.

Sisson's equatorial mounting design had first been proposed in 1741 by Henry Hindley of York

York is a cathedral city with Roman Britain, Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers River Ouse, Yorkshire, Ouse and River Foss, Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many hist ...

.

The telescope was attached to one side of a square polar axis

An equatorial mount is a mount for instruments that compensates for Earth's rotation by having one rotational axis, the polar axis, parallel to the Earth's axis of rotation. This type of mount is used for astronomical telescopes and cameras. The ...

, near the upper end of the axis, balanced by a weight on the other side.

A similar arrangement is used in some telescopes today.

His transit telescope used a hollow-cone design for its axis, a design adopted by later instrument makers such as Jesse Ramsden (1735–1800).

Honours

Sisson Rock

Sisson Rock ( bg, скала Сисън, skala Sisson, ) is the rock off the north coast of Livingston Island in the South Shetland Islands, Antarctica long in west-east direction and wide, and split in three. Its surface area is . The vicinity ...

in Antarctica

Antarctica () is Earth's southernmost and least-populated continent. Situated almost entirely south of the Antarctic Circle and surrounded by the Southern Ocean, it contains the geographic South Pole. Antarctica is the fifth-largest co ...

is named after Jonathan Sisson.

References

Notes

Citations

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Sisson, Jonathan 1690 births 1747 deaths British scientific instrument makers People from Lincolnshire