Johnson–Corey–Chaykovsky Reaction on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

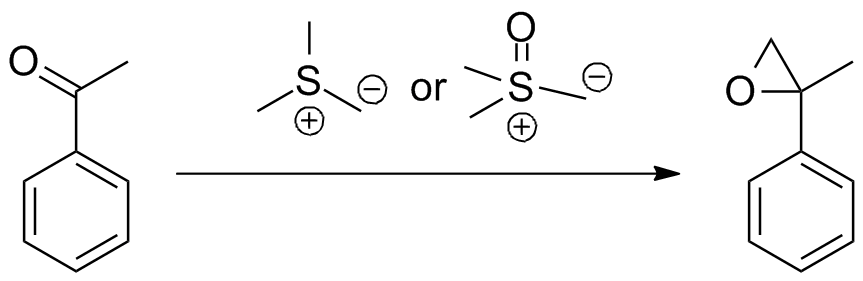

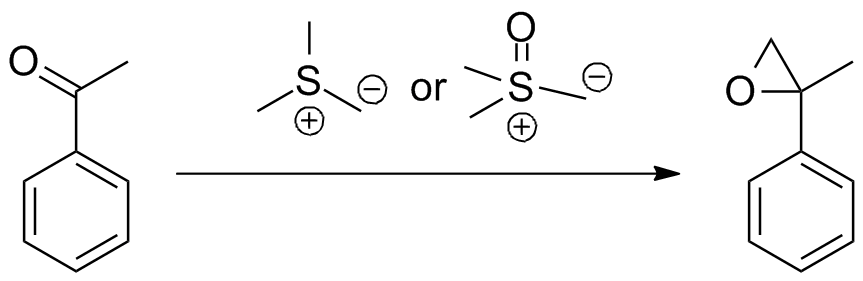

The Johnson–Corey–Chaykovsky reaction (sometimes referred to as the Corey–Chaykovsky reaction or CCR) is a  The reaction is most often employed for epoxidation via methylene transfer, and to this end has been used in several notable total syntheses (See Synthesis of epoxides below). Additionally detailed below are the history, mechanism, scope, and enantioselective variants of the reaction. Several reviews have been published.

The reaction is most often employed for epoxidation via methylene transfer, and to this end has been used in several notable total syntheses (See Synthesis of epoxides below). Additionally detailed below are the history, mechanism, scope, and enantioselective variants of the reaction. Several reviews have been published.

The subsequent development of (dimethyloxosulfaniumyl)methanide, (CH3)2SOCH2 and (dimethylsulfaniumyl)methanide, (CH3)2SCH2 (known as Corey–Chaykovsky reagents) by Corey and Chaykovsky as efficient methylene-transfer reagents established the reaction as a part of the organic canon.

The subsequent development of (dimethyloxosulfaniumyl)methanide, (CH3)2SOCH2 and (dimethylsulfaniumyl)methanide, (CH3)2SCH2 (known as Corey–Chaykovsky reagents) by Corey and Chaykovsky as efficient methylene-transfer reagents established the reaction as a part of the organic canon.

The ''trans''

The ''trans''

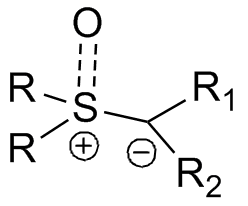

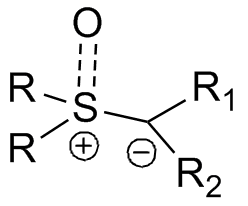

Many types of ylides can be prepared with various functional groups both on the anionic carbon center and on the sulfur. The substitution pattern can influence the ease of preparation for the reagents (typically from the sulfonium halide, e.g. trimethylsulfonium iodide) and overall reaction rate in various ways. The general format for the reagent is shown on the right.

Use of a sulfoxonium allows more facile preparation of the reagent using weaker bases as compared to sulfonium ylides. (The difference being that a sulfoxonium contains a doubly bonded oxygen whereas the sulfonium does not.) The former react slower due to their increased stability. In addition, the dialkylsulfoxide

Many types of ylides can be prepared with various functional groups both on the anionic carbon center and on the sulfur. The substitution pattern can influence the ease of preparation for the reagents (typically from the sulfonium halide, e.g. trimethylsulfonium iodide) and overall reaction rate in various ways. The general format for the reagent is shown on the right.

Use of a sulfoxonium allows more facile preparation of the reagent using weaker bases as compared to sulfonium ylides. (The difference being that a sulfoxonium contains a doubly bonded oxygen whereas the sulfonium does not.) The former react slower due to their increased stability. In addition, the dialkylsulfoxide

The reaction has been used in a number of notable total syntheses including the

The reaction has been used in a number of notable total syntheses including the

*Several

*Several  *

*

The other major reagent is a

The other major reagent is a

Aggarwal has developed an alternative method employing the same sulfide as above and a novel alkylation involving a

Aggarwal has developed an alternative method employing the same sulfide as above and a novel alkylation involving a

Animation of the mechanism

{{DEFAULTSORT:Johnson-Corey-Chaykovsky reaction Addition reactions Carbon-carbon bond forming reactions Epoxidation reactions Name reactions

chemical reaction

A chemical reaction is a process that leads to the chemistry, chemical transformation of one set of chemical substances to another. When chemical reactions occur, the atoms are rearranged and the reaction is accompanied by an Gibbs free energy, ...

used in organic chemistry

Organic chemistry is a subdiscipline within chemistry involving the science, scientific study of the structure, properties, and reactions of organic compounds and organic matter, organic materials, i.e., matter in its various forms that contain ...

for the synthesis of epoxide

In organic chemistry, an epoxide is a cyclic ether, where the ether forms a three-atom ring: two atoms of carbon and one atom of oxygen. This triangular structure has substantial ring strain, making epoxides highly reactive, more so than other ...

s, aziridine

Aziridine is an organic compound consisting of the three-membered heterocycle . It is a colorless, toxic, volatile liquid that is of significant practical interest. Aziridine was discovered in 1888 by the chemist Siegmund Gabriel. Its deriva ...

s, and cyclopropane

Cyclopropane is the cycloalkane with the molecular formula (CH2)3, consisting of three methylene groups (CH2) linked to each other to form a triangular ring. The small size of the ring creates substantial ring strain in the structure. Cyclopropane ...

s. It was discovered in 1961 by A. William Johnson and developed significantly by E. J. Corey and Michael Chaykovsky. The reaction involves addition of a sulfur ylide

An ylide () or ylid () is a neutral dipolar molecule containing a formally negatively charged atom (usually a carbanion) directly attached to a heteroatom with a formal positive charge (usually nitrogen, phosphorus or sulfur), and in which both ...

to a ketone

In organic chemistry, a ketone is an organic compound with the structure , where R and R' can be a variety of carbon-containing substituents. Ketones contain a carbonyl group (a carbon-oxygen double bond C=O). The simplest ketone is acetone ( ...

, aldehyde

In organic chemistry, an aldehyde () (lat. ''al''cohol ''dehyd''rogenatum, dehydrogenated alcohol) is an organic compound containing a functional group with the structure . The functional group itself (without the "R" side chain) can be referred ...

, imine

In organic chemistry, an imine ( or ) is a functional group or organic compound containing a carbon–nitrogen double bond (). The nitrogen atom can be attached to a hydrogen or an organic group (R). The carbon atom has two additional single bon ...

, or enone to produce the corresponding 3-membered ring. The reaction is diastereoselective

In stereochemistry, diastereomers (sometimes called diastereoisomers) are a type of stereoisomer. Diastereomers are defined as non-mirror image, non-identical stereoisomers. Hence, they occur when two or more stereoisomers of a compound have dif ...

favoring ''trans'' substitution in the product regardless of the initial stereochemistry

Stereochemistry, a subdiscipline of chemistry, studies the spatial arrangement of atoms that form the structure of molecules and their manipulation. The study of stereochemistry focuses on the relationships between stereoisomers, which are defined ...

. The synthesis of epoxide

In organic chemistry, an epoxide is a cyclic ether, where the ether forms a three-atom ring: two atoms of carbon and one atom of oxygen. This triangular structure has substantial ring strain, making epoxides highly reactive, more so than other ...

s via this method serves as an important retrosynthetic alternative to the traditional epoxidation

In organic chemistry, an epoxide is a cyclic ether, where the ether forms a three-atom ring: two atoms of carbon and one atom of oxygen. This triangular structure has substantial ring strain, making epoxides highly reactive, more so than other ...

reactions of olefin

In organic chemistry, an alkene, or olefin, is a hydrocarbon containing a carbon–carbon double bond. The double bond may be internal or at the terminal position. Terminal alkenes are also known as α-olefins.

The International Union of Pu ...

s.

The reaction is most often employed for epoxidation via methylene transfer, and to this end has been used in several notable total syntheses (See Synthesis of epoxides below). Additionally detailed below are the history, mechanism, scope, and enantioselective variants of the reaction. Several reviews have been published.

The reaction is most often employed for epoxidation via methylene transfer, and to this end has been used in several notable total syntheses (See Synthesis of epoxides below). Additionally detailed below are the history, mechanism, scope, and enantioselective variants of the reaction. Several reviews have been published.

History

The original publication by Johnson concerned the reaction of 9-dimethylsulfonium fluorenylide with substitutedbenzaldehyde

Benzaldehyde (C6H5CHO) is an organic compound consisting of a benzene ring with a formyl substituent. It is among the simplest aromatic aldehydes and one of the most industrially useful.

It is a colorless liquid with a characteristic almond-li ...

derivatives. The attempted Wittig-like reaction failed and a benzalfluorene oxide was obtained instead, noting that "reaction between the sulfur ylid and benzaldehydes did not afford benzalfluorenes as had the phosphorus and arsenic ylids."

The subsequent development of (dimethyloxosulfaniumyl)methanide, (CH3)2SOCH2 and (dimethylsulfaniumyl)methanide, (CH3)2SCH2 (known as Corey–Chaykovsky reagents) by Corey and Chaykovsky as efficient methylene-transfer reagents established the reaction as a part of the organic canon.

The subsequent development of (dimethyloxosulfaniumyl)methanide, (CH3)2SOCH2 and (dimethylsulfaniumyl)methanide, (CH3)2SCH2 (known as Corey–Chaykovsky reagents) by Corey and Chaykovsky as efficient methylene-transfer reagents established the reaction as a part of the organic canon.

Mechanism

Thereaction mechanism

In chemistry, a reaction mechanism is the step by step sequence of elementary reactions by which overall chemical reaction occurs.

A chemical mechanism is a theoretical conjecture that tries to describe in detail what takes place at each stage ...

for the Johnson–Corey–Chaykovsky reaction consists of nucleophilic addition

In organic chemistry, a nucleophilic addition (AN) reaction is an addition reaction where a chemical compound with an electrophilic double or triple bond reacts with a nucleophile, such that the double or triple bond is broken. Nucleophilic addit ...

of the ylide

An ylide () or ylid () is a neutral dipolar molecule containing a formally negatively charged atom (usually a carbanion) directly attached to a heteroatom with a formal positive charge (usually nitrogen, phosphorus or sulfur), and in which both ...

to the carbonyl

In organic chemistry, a carbonyl group is a functional group with the formula , composed of a carbon atom double bond, double-bonded to an oxygen atom, and it is divalent at the C atom. It is common to several classes of organic compounds (such a ...

or imine

In organic chemistry, an imine ( or ) is a functional group or organic compound containing a carbon–nitrogen double bond (). The nitrogen atom can be attached to a hydrogen or an organic group (R). The carbon atom has two additional single bon ...

group. A negative charge is transferred to the heteroatom

In chemistry, a heteroatom () is, strictly, any atom that is not carbon or hydrogen.

Organic chemistry

In practice, the term is mainly used more specifically to indicate that non-carbon atoms have replaced carbon in the backbone of the molecular ...

and because the sulfonium

In organic chemistry, a sulfonium ion, also known as sulphonium ion or sulfanium ion, is a positively-charged ion (a "cation") featuring three organic Substitution (chemistry), substituents attached to sulfur. These organosulfur compounds have t ...

cation

An ion () is an atom or molecule with a net electrical charge. The charge of an electron is considered to be negative by convention and this charge is equal and opposite to the charge of a proton, which is considered to be positive by convent ...

is a good leaving group

In organic chemistry, a leaving group typically means a Chemical species, molecular fragment that departs with an electron, electron pair during a reaction step with heterolysis (chemistry), heterolytic bond cleavage. In this usage, a ''leaving gr ...

it gets expelled forming the ring. In the related Wittig reaction

The Wittig reaction or Wittig olefination is a chemical reaction of an aldehyde or ketone with a triphenyl phosphonium ylide called a Wittig reagent. Wittig reactions are most commonly used to convert aldehydes and ketones to alkenes. Most o ...

, the formation of the much stronger phosphorus

Phosphorus is a chemical element; it has Chemical symbol, symbol P and atomic number 15. All elemental forms of phosphorus are highly Reactivity (chemistry), reactive and are therefore never found in nature. They can nevertheless be prepared ar ...

-oxygen

Oxygen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group (periodic table), group in the periodic table, a highly reactivity (chemistry), reactive nonmetal (chemistry), non ...

double bond

In chemistry, a double bond is a covalent bond between two atoms involving four bonding electrons as opposed to two in a single bond. Double bonds occur most commonly between two carbon atoms, for example in alkenes. Many double bonds exist betw ...

prevents oxirane formation and instead, olefination takes place through a 4-membered cyclic intermediate.

diastereoselectivity

In stereochemistry, diastereomers (sometimes called diastereoisomers) are a type of stereoisomer. Diastereomers are defined as non-mirror image, non-identical stereoisomers. Hence, they occur when two or more stereoisomers of a compound have d ...

observed results from the reversibility of the initial addition, allowing equilibration to the favored ''anti'' betaine

A betaine () in chemistry is any neutral chemical compound with a positively charged cationic functional group that bears no hydrogen atom, such as a Quaternary ammonium cation, quaternary ammonium or phosphonium cation (generally: Onium compou ...

over the ''syn'' betaine. Initial addition of the ylide results in a betaine with adjacent charges; density functional theory

Density functional theory (DFT) is a computational quantum mechanical modelling method used in physics, chemistry and materials science to investigate the electronic structure (or nuclear structure) (principally the ground state) of many-body ...

calculations have shown that the rate-limiting step

In chemical kinetics, the overall rate of a reaction is often approximately determined by the slowest step, known as the rate-determining step (RDS or RD-step or r/d step) or rate-limiting step. For a given reaction mechanism, the prediction of the ...

is rotation of the central bond into the conformer necessary for backside attack on the sulfonium.

The degree of reversibility in the initial step (and therefore the diastereoselectivity) depends on four factors, with greater reversibility corresponding to higher selectivity:

# ''Stability of the substrate'' with higher stability leading to greater reversibility by favoring the starting material over the betaine.

# ''Stability of the ylide'' with higher stability similarly leading to greater reversibility.

#''Steric hindrance

Steric effects arise from the spatial arrangement of atoms. When atoms come close together there is generally a rise in the energy of the molecule. Steric effects are nonbonding interactions that influence the shape ( conformation) and reactivi ...

in the betaine'' with greater hindrance leading to greater reversibility by disfavoring formation of the intermediate and slowing the rate-limiting rotation of the central bond.

#''Solvation of charges in the betaine'' by counterion

160px, cation-exchange_resin.html" ;"title="Polystyrene sulfonate, a cation-exchange resin">Polystyrene sulfonate, a cation-exchange resin, is typically supplied with as the counterion.

In chemistry, a counterion (sometimes written as "counter ...

s such as lithium

Lithium (from , , ) is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol Li and atomic number 3. It is a soft, silvery-white alkali metal. Under standard temperature and pressure, standard conditions, it is the least dense metal and the ...

with greater solvation allowing more facile rotation in the betaine intermediate, lowering the amount of reversibility.

Scope

The application of the Johnson–Corey–Chaykovsky reaction in organic synthesis is diverse. The reaction has come to encompass reactions of many types of sulfur ylides withelectrophile

In chemistry, an electrophile is a chemical species that forms bonds with nucleophiles by accepting an electron pair. Because electrophiles accept electrons, they are Lewis acids. Most electrophiles are positively Electric charge, charged, have an ...

s well beyond the original publications. It has seen use in a number of high-profile total syntheses, as detailed below, and is generally recognized as a powerful transformative tool in the organic repertoire.

Types of ylides

Many types of ylides can be prepared with various functional groups both on the anionic carbon center and on the sulfur. The substitution pattern can influence the ease of preparation for the reagents (typically from the sulfonium halide, e.g. trimethylsulfonium iodide) and overall reaction rate in various ways. The general format for the reagent is shown on the right.

Use of a sulfoxonium allows more facile preparation of the reagent using weaker bases as compared to sulfonium ylides. (The difference being that a sulfoxonium contains a doubly bonded oxygen whereas the sulfonium does not.) The former react slower due to their increased stability. In addition, the dialkylsulfoxide

Many types of ylides can be prepared with various functional groups both on the anionic carbon center and on the sulfur. The substitution pattern can influence the ease of preparation for the reagents (typically from the sulfonium halide, e.g. trimethylsulfonium iodide) and overall reaction rate in various ways. The general format for the reagent is shown on the right.

Use of a sulfoxonium allows more facile preparation of the reagent using weaker bases as compared to sulfonium ylides. (The difference being that a sulfoxonium contains a doubly bonded oxygen whereas the sulfonium does not.) The former react slower due to their increased stability. In addition, the dialkylsulfoxide by-product

A by-product or byproduct is a secondary product derived from a production process, manufacturing process or chemical reaction; it is not the primary product or service being produced.

A by-product can be useful and marketable or it can be cons ...

s of sulfoxonium reagents are greatly preferred to the significantly more toxic, volatile, and odorous dialkylsulfide by-products from sulfonium reagents.

The vast majority of reagents are monosubstituted at the ylide carbon (either R1 or R2 as hydrogen). Disubstituted reagents are much rarer but have been described:

#If the ylide carbon is substituted with an electron-withdrawing group

An electron-withdrawing group (EWG) is a Functional group, group or atom that has the ability to draw electron density toward itself and away from other adjacent atoms. This electron density transfer is often achieved by resonance or inductive effe ...

(EWG), the reagent is referred to as a ''stabilized ylide''. These, similarly to sulfoxonium reagents, react much slower and are typically easier to prepare. These are limited in their usefulness as the reaction can become prohibitively sluggish: examples involving amide

In organic chemistry, an amide, also known as an organic amide or a carboxamide, is a chemical compound, compound with the general formula , where R, R', and R″ represent any group, typically organyl functional group, groups or hydrogen at ...

s are widespread, with many fewer involving ester

In chemistry, an ester is a compound derived from an acid (either organic or inorganic) in which the hydrogen atom (H) of at least one acidic hydroxyl group () of that acid is replaced by an organyl group (R). These compounds contain a distin ...

s and virtually no examples involving other EWG's. For these, the related Darzens reaction is typically more appropriate.

#If the ylide carbon is substituted with an aryl

In organic chemistry, an aryl is any functional group or substituent derived from an aromatic ring, usually an aromatic hydrocarbon, such as phenyl and naphthyl. "Aryl" is used for the sake of abbreviation or generalization, and "Ar" is used ...

or allyl

In organic chemistry, an allyl group is a substituent with the structural formula . It consists of a methylene bridge () attached to a vinyl group (). The name is derived from the scientific name for garlic, . In 1844, Theodor Wertheim isolated a ...

group, the reagent is referred to as a ''semi-stabilized ylide''. These have been developed extensively, second only to the classical methylene reagents (R1=R2=H). The substitution pattern on aryl reagents can heavily influence the selectivity of the reaction as per the criteria above.

#If the ylide carbon is substituted with an alkyl group the reagent is referred to as an ''unstabilized ylide''. The size of the alkyl groups are the major factors in selectivity with these reagents.

The R-groups on the sulfur, though typically methyl

In organic chemistry, a methyl group is an alkyl derived from methane, containing one carbon atom bonded to three hydrogen atoms, having chemical formula (whereas normal methane has the formula ). In formulas, the group is often abbreviated as ...

s, have been used to synthesize reagents that can perform enantioselective

In chemistry, stereoselectivity is the property of a chemical reaction in which a single reactant forms an unequal mixture of stereoisomers during a non- stereospecific creation of a new stereocenter or during a non-stereospecific transformation o ...

variants of the reaction (See Variations below). The size of the groups can also influence diastereoselectivity

In stereochemistry, diastereomers (sometimes called diastereoisomers) are a type of stereoisomer. Diastereomers are defined as non-mirror image, non-identical stereoisomers. Hence, they occur when two or more stereoisomers of a compound have d ...

in alicyclic

In organic chemistry, an alicyclic compound contains one or more all-carbon rings which may be either saturated or unsaturated, but do not have aromatic character. Alicyclic compounds may have one or more aliphatic side chains attached.

Cyclo ...

substrates.

Synthesis of epoxides

Reactions of sulfur ylides withketone

In organic chemistry, a ketone is an organic compound with the structure , where R and R' can be a variety of carbon-containing substituents. Ketones contain a carbonyl group (a carbon-oxygen double bond C=O). The simplest ketone is acetone ( ...

s and aldehyde

In organic chemistry, an aldehyde () (lat. ''al''cohol ''dehyd''rogenatum, dehydrogenated alcohol) is an organic compound containing a functional group with the structure . The functional group itself (without the "R" side chain) can be referred ...

s to form epoxide

In organic chemistry, an epoxide is a cyclic ether, where the ether forms a three-atom ring: two atoms of carbon and one atom of oxygen. This triangular structure has substantial ring strain, making epoxides highly reactive, more so than other ...

s are by far the most common application of the Johnson–Corey–Chaykovsky reaction. Examples involving complex substrates and 'exotic' ylides have been reported, as shown below.

The reaction has been used in a number of notable total syntheses including the

The reaction has been used in a number of notable total syntheses including the Danishefsky Taxol total synthesis

The Danishefsky Taxol total synthesis in organic chemistry is an important third Taxol synthesis published by the group of Samuel Danishefsky in 1996 two years after the first two efforts described in the Holton Taxol total synthesis and the Ni ...

, which produces the chemotherapeutic

Chemotherapy (often abbreviated chemo, sometimes CTX and CTx) is the type of cancer treatment that uses one or more anti-cancer drugs (chemotherapeutic agents or alkylating agents) in a standard regimen. Chemotherapy may be given with a curat ...

drug taxol

Paclitaxel, sold under the brand name Taxol among others, is a chemotherapy medication used to treat ovarian cancer, esophageal cancer, breast cancer, lung cancer, Kaposi's sarcoma, cervical cancer, and pancreatic cancer. It is administered by ...

, and the Kuehne Strychnine total synthesis which produces the pesticide strychnine

Strychnine (, , American English, US chiefly ) is a highly toxicity, toxic, colorless, bitter, crystalline alkaloid used as a pesticide, particularly for killing small vertebrates such as birds and rodents. Strychnine, when inhaled, swallowed, ...

.

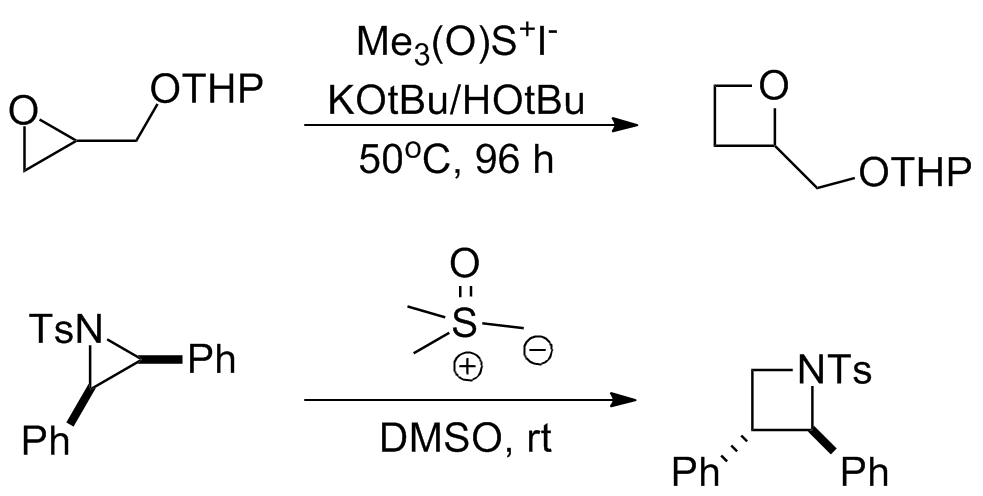

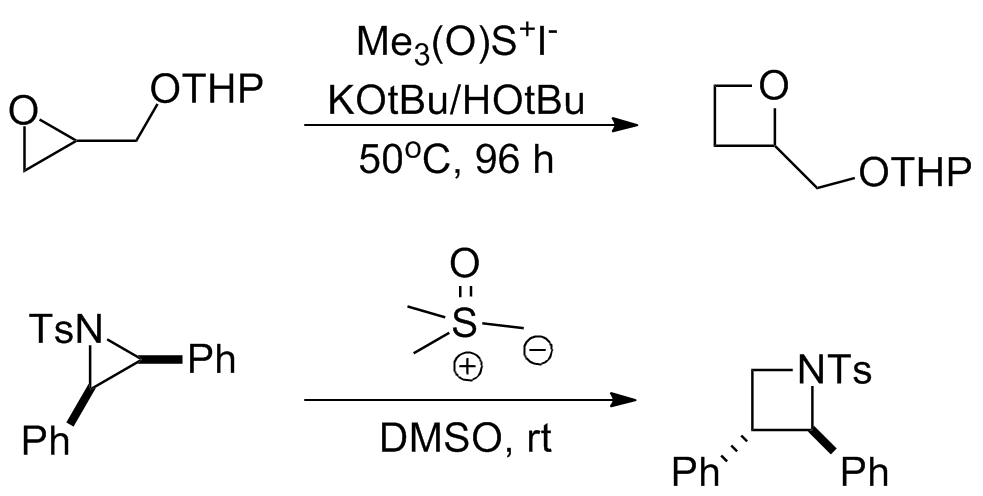

Synthesis of aziridines

The synthesis ofaziridine

Aziridine is an organic compound consisting of the three-membered heterocycle . It is a colorless, toxic, volatile liquid that is of significant practical interest. Aziridine was discovered in 1888 by the chemist Siegmund Gabriel. Its deriva ...

s from imine

In organic chemistry, an imine ( or ) is a functional group or organic compound containing a carbon–nitrogen double bond (). The nitrogen atom can be attached to a hydrogen or an organic group (R). The carbon atom has two additional single bon ...

s is another important application of the Johnson–Corey–Chaykovsky reaction and provides an alternative to amine

In chemistry, amines (, ) are organic compounds that contain carbon-nitrogen bonds. Amines are formed when one or more hydrogen atoms in ammonia are replaced by alkyl or aryl groups. The nitrogen atom in an amine possesses a lone pair of elec ...

transfer from oxaziridine

An oxaziridine is an organic molecule that features a three-membered heterocycle containing oxygen, nitrogen, and carbon. In their largest industrial application, oxaziridines are intermediates in the production of hydrazine. Oxaziridine deriv ...

s. Though less widely applied, the reaction has a similar substrate scope and functional group

In organic chemistry, a functional group is any substituent or moiety (chemistry), moiety in a molecule that causes the molecule's characteristic chemical reactions. The same functional group will undergo the same or similar chemical reactions r ...

tolerance to the carbonyl equivalent. The examples shown below are representative; in the latter, an aziridine forms ''in situ'' and is opened via nucleophilic attack

In chemistry, a nucleophile is a chemical species that forms bonds by donating an electron pair. All molecules and ions with a free pair of electrons or at least one pi bond can act as nucleophiles. Because nucleophiles donate electrons, they a ...

to form the corresponding amine

In chemistry, amines (, ) are organic compounds that contain carbon-nitrogen bonds. Amines are formed when one or more hydrogen atoms in ammonia are replaced by alkyl or aryl groups. The nitrogen atom in an amine possesses a lone pair of elec ...

.

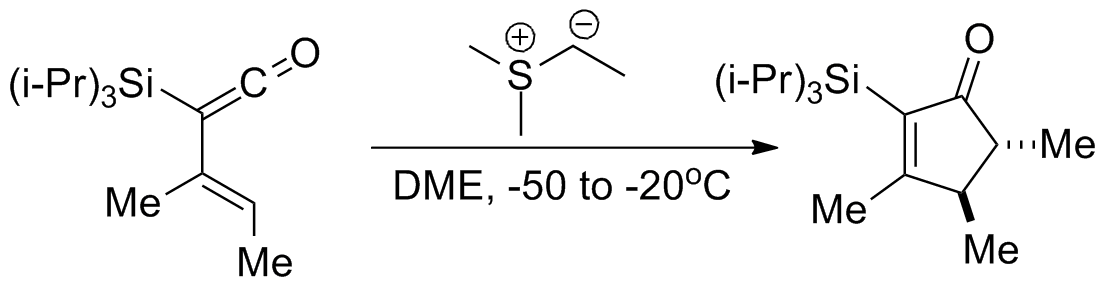

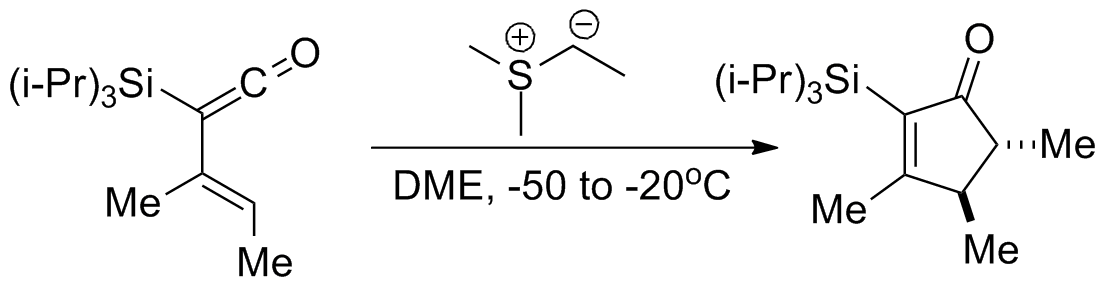

Synthesis of cyclopropanes

For addition of sulfur ylides to enones, higher 1,4-selectivity is typically obtained with sulfoxonium reagents than with sulfonium reagents. One explanation based on theHSAB theory

HSAB is an acronym for "hard and soft (Lewis) acids and bases". HSAB is widely used in chemistry for explaining the stability of compounds, reaction mechanisms and pathways. It assigns the terms 'hard' or 'soft', and 'acid' or 'base' to chemical ...

states that it is because sulfoxonium reagents have a less concentrated negative charge on the carbon atom (softer), so it prefers 1,4-attack on the softer nucleophilic site. Another explanation supported by density functional theory (DFT) studies suggests an irreversible 1,4-attack leading to the cyclopropane is energetically favored versus a reversible 1,2-attack that would lead to the epoxide. With extended conjugated systems 1,6-addition tends to predominate over 1,4-addition. Many electron-withdrawing groups have been shown promote the cyclopropanation including ketone

In organic chemistry, a ketone is an organic compound with the structure , where R and R' can be a variety of carbon-containing substituents. Ketones contain a carbonyl group (a carbon-oxygen double bond C=O). The simplest ketone is acetone ( ...

s, ester

In chemistry, an ester is a compound derived from an acid (either organic or inorganic) in which the hydrogen atom (H) of at least one acidic hydroxyl group () of that acid is replaced by an organyl group (R). These compounds contain a distin ...

s, amide

In organic chemistry, an amide, also known as an organic amide or a carboxamide, is a chemical compound, compound with the general formula , where R, R', and R″ represent any group, typically organyl functional group, groups or hydrogen at ...

s (the example below involves a Weinreb amide

The Weinreb ketone synthesis or Weinreb–Nahm ketone synthesis is a chemical reaction used in organic chemistry to make carbon–carbon bonds. It was discovered in 1981 by Steven M. Weinreb and Steven Nahm as a method to synthesize ketones. The ...

), sulfones

In organic chemistry, a sulfone is a organosulfur compound containing a sulfonyl () functional group attached to two carbon atoms. The central hexavalent sulfur atom is double-bonded to each of two oxygen atoms and has a single bond to each of ...

, nitro groups, phosphonates

In organic chemistry, phosphonates or phosphonic acids are organophosphorus compounds containing groups, where R is an organic group (alkyl, aryl). If R is hydrogen then the compound is a dialkyl phosphite, which is a different functional gr ...

, isocyanides and even some electron deficient heterocycles.

Other reactions

In addition to the reactions originally reported by Johnson, Corey, and Chaykovsky, sulfur ylides have been used for a number of relatedhomologation reaction

In organic chemistry, a homologation reaction, also known as homologization, is any chemical reaction that converts the reactant into the next member of the homologous series. A homologous series is a group of compounds that differ by a constant ...

s that tend to be grouped under the same name.

*With epoxide

In organic chemistry, an epoxide is a cyclic ether, where the ether forms a three-atom ring: two atoms of carbon and one atom of oxygen. This triangular structure has substantial ring strain, making epoxides highly reactive, more so than other ...

s and aziridine

Aziridine is an organic compound consisting of the three-membered heterocycle . It is a colorless, toxic, volatile liquid that is of significant practical interest. Aziridine was discovered in 1888 by the chemist Siegmund Gabriel. Its deriva ...

s the reaction serves as a ring-expansion to produce the corresponding oxetane or azetidine. The long reaction times required for these reactions prevent them from occurring as significant side reaction

A side reaction is a chemical reaction that occurs at the same time as the actual main reaction, but to a lesser extent. It leads to the formation of by-product, so that the Yield (chemistry), yield of main product is reduced:

: + B ->[] P1

: + C ...

s when synthesizing epoxides and aziridines.

*Several

*Several cycloaddition

In organic chemistry, a cycloaddition is a chemical reaction in which "two or more Unsaturated hydrocarbon, unsaturated molecules (or parts of the same molecule) combine with the formation of a cyclic adduct in which there is a net reduction of th ...

s wherein the ylide serves as a "nucleophilic

In chemistry, a nucleophile is a chemical species that forms bonds by donating an electron pair. All molecules and ions with a free pair of electrons or at least one pi bond can act as nucleophiles. Because nucleophiles donate electrons, they a ...

carbenoid equivalent" have been reported.

*

*Living polymerization

In polymer chemistry, living polymerization is a form of chain growth polymerization where the ability of a growing polymer chain to terminate has been removed. This can be accomplished in a variety of ways. Chain termination and chain transf ...

s using trialkylboranes as the catalyst and (dimethyloxosulfaniumyl)methanide as the monomer have been reported for the synthesis of various complex polymers.

Enantioselective variations

The development of anenantioselective

In chemistry, stereoselectivity is the property of a chemical reaction in which a single reactant forms an unequal mixture of stereoisomers during a non- stereospecific creation of a new stereocenter or during a non-stereospecific transformation o ...

(i.e. yielding an enantiomeric excess

In stereochemistry, enantiomeric excess (ee) is a measurement of purity used for chiral substances. It reflects the degree to which a sample contains one enantiomer in greater amounts than the other. A racemic mixture has an ee of 0%, while a sing ...

, which is labelled as "ee") variant of the Johnson–Corey–Chaykovsky reaction remains an active area of academic research. The use of chiral

Chirality () is a property of asymmetry important in several branches of science. The word ''chirality'' is derived from the Greek language, Greek (''kheir''), "hand", a familiar chiral object.

An object or a system is ''chiral'' if it is dist ...

sulfides in a stoichiometric

Stoichiometry () is the relationships between the masses of reactants and products before, during, and following chemical reactions.

Stoichiometry is based on the law of conservation of mass; the total mass of reactants must equal the total m ...

fashion has proved more successful than the corresponding catalytic

Catalysis () is the increase in reaction rate, rate of a chemical reaction due to an added substance known as a catalyst (). Catalysts are not consumed by the reaction and remain unchanged after it. If the reaction is rapid and the catalyst ...

variants, but the substrate scope is still limited in all cases. The catalytic variants have been developed almost exclusively for enantioselective purposes; typical organosulfide reagents are not prohibitively expensive and the racemic reactions can be carried out with equimolar amounts of ylide without raising costs significantly. Chiral sulfides, on the other hand, are more costly to prepare, spurring the advancement of catalytic enantioselective methods.

Stoichiometric reagents

The most successful reagents employed in a stoichiometric fashion are shown below. The first is abicyclic

A bicyclic molecule () is a molecule that features two joined rings. Bicyclic structures occur widely, for example in many biologically important molecules like α-thujene and camphor. A bicyclic compound can be carbocyclic (all of the ring ...

oxathiane that has been employed in the synthesis of the β-adrenergic compound ''dichloroisoproterenol'' (DCI) but is limited by the availability of only one enantiomer of the reagent. The synthesis of the axial diastereomer is rationalized via the 1,3-anomeric effect

In organic chemistry, the anomeric effect or Edward-Lemieux effect (after J. T. Edward and Raymond Lemieux) is a stereoelectronic effect that describes the tendency of heteroatomic substituents adjacent to the heteroatom in the ring in, e.g., t ...

which reduces the nucleophilicity of the equatorial lone pair

In chemistry, a lone pair refers to a pair of valence electrons that are not shared with another atom in a covalent bondIUPAC ''Gold Book'' definition''lone (electron) pair''/ref> and is sometimes called an unshared pair or non-bonding pair. Lone ...

. The conformation of the ylide is limited by transannular strain and approach of the aldehyde is limited to one face of the ylide by steric interactions with the methyl substituents.

The other major reagent is a

The other major reagent is a camphor

Camphor () is a waxy, colorless solid with a strong aroma. It is classified as a terpenoid and a cyclic ketone. It is found in the wood of the camphor laurel (''Cinnamomum camphora''), a large evergreen tree found in East Asia; and in the kapu ...

-derived reagent developed by Varinder Aggarwal of the University of Bristol

The University of Bristol is a public university, public research university in Bristol, England. It received its royal charter in 1909, although it can trace its roots to a Merchant Venturers' school founded in 1595 and University College, Br ...

. Both enantiomer

In chemistry, an enantiomer (Help:IPA/English, /ɪˈnænti.əmər, ɛ-, -oʊ-/ Help:Pronunciation respelling key, ''ih-NAN-tee-ə-mər''), also known as an optical isomer, antipode, or optical antipode, is one of a pair of molecular entities whi ...

s are easily synthesized, although the yields are lower than for the oxathiane reagent. The ylide conformation is determined by interaction with the bridgehead

In military strategy, a bridgehead (or bridge-head) is the strategically important area of ground around the end of a bridge or other place of possible crossing over a body of water which at time of conflict is sought to be defended or taken over ...

hydrogens and approach of the aldehyde is blocked by the camphor moiety. The reaction employs a phosphazene

Phosphazenes refer to various classes of organophosphorus compounds featuring phosphorus(V) with a double bond between P and N. One class of phosphazenes have the formula . These phosphazenes are also known as iminophosphoranes and phosphine imides ...

base to promote formation of the ylide.

Catalytic reagents

Catalytic reagents have been less successful, with most variations suffering from poor yield, poor enantioselectivity, or both. There are also issues with substrate scope, most having limitations with methylene transfer andaliphatic

In organic chemistry, hydrocarbons ( compounds composed solely of carbon and hydrogen) are divided into two classes: aromatic compounds and aliphatic compounds (; G. ''aleiphar'', fat, oil). Aliphatic compounds can be saturated (in which all ...

aldehyde

In organic chemistry, an aldehyde () (lat. ''al''cohol ''dehyd''rogenatum, dehydrogenated alcohol) is an organic compound containing a functional group with the structure . The functional group itself (without the "R" side chain) can be referred ...

s. The trouble stems from the need for a nucleophilic

In chemistry, a nucleophile is a chemical species that forms bonds by donating an electron pair. All molecules and ions with a free pair of electrons or at least one pi bond can act as nucleophiles. Because nucleophiles donate electrons, they a ...

sulfide that efficiently generates the ylide which can also act as a good leaving group

In organic chemistry, a leaving group typically means a Chemical species, molecular fragment that departs with an electron, electron pair during a reaction step with heterolysis (chemistry), heterolytic bond cleavage. In this usage, a ''leaving gr ...

to form the epoxide. Since the factors underlying these desiderata are at odds, tuning of the catalyst properties has proven difficult. Shown below are several of the most successful catalysts along with the yields and enantiomeric excess for their use in synthesis of (E)-stilbene

(''E'')-Stilbene, commonly known as ''trans''-stilbene, is an organic compound represented by the Structural formula#Condensed formulas, condensed structural formula CHCH=CHCH. Classified as a diarylethene, it features a central ethylene moiety ...

oxide.

Aggarwal has developed an alternative method employing the same sulfide as above and a novel alkylation involving a

Aggarwal has developed an alternative method employing the same sulfide as above and a novel alkylation involving a rhodium

Rhodium is a chemical element; it has symbol Rh and atomic number 45. It is a very rare, silvery-white, hard, corrosion-resistant transition metal. It is a noble metal and a member of the platinum group. It has only one naturally occurring isot ...

carbenoid formed ''in situ

is a Latin phrase meaning 'in place' or 'on site', derived from ' ('in') and ' ( ablative of ''situs'', ). The term typically refers to the examination or occurrence of a process within its original context, without relocation. The term is use ...

''. The method too has limited substrate scope, failing for any electrophile

In chemistry, an electrophile is a chemical species that forms bonds with nucleophiles by accepting an electron pair. Because electrophiles accept electrons, they are Lewis acids. Most electrophiles are positively Electric charge, charged, have an ...

s possessing basic substituents due to competitive consumption of the carbenoid.

See also

* Darzens reaction *Wittig reaction

The Wittig reaction or Wittig olefination is a chemical reaction of an aldehyde or ketone with a triphenyl phosphonium ylide called a Wittig reagent. Wittig reactions are most commonly used to convert aldehydes and ketones to alkenes. Most o ...

*Epoxidation

In organic chemistry, an epoxide is a cyclic ether, where the ether forms a three-atom ring: two atoms of carbon and one atom of oxygen. This triangular structure has substantial ring strain, making epoxides highly reactive, more so than other ...

*Ylide

An ylide () or ylid () is a neutral dipolar molecule containing a formally negatively charged atom (usually a carbanion) directly attached to a heteroatom with a formal positive charge (usually nitrogen, phosphorus or sulfur), and in which both ...

* E.J. Corey

* Taxol total synthesis

* Strychnine total synthesis

References

External links

Animation of the mechanism

{{DEFAULTSORT:Johnson-Corey-Chaykovsky reaction Addition reactions Carbon-carbon bond forming reactions Epoxidation reactions Name reactions