Johns Hopkins on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Johns Hopkins (May 19, 1795 – December 24, 1873) was an American merchant, investor, and philanthropist. Born on a plantation, he left his home to start a career at the age of 17, and settled in

Hopkins lived his entire adult life in

Hopkins lived his entire adult life in

Hopkins died on December 24, 1873, in

Hopkins died on December 24, 1873, in

Hopkins Family Papers, Sheridan Libraries, Johns Hopkins University

* [https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?doc=Perseus:text:2001.01.0027 In his 1887 memoir, Baltimore and the Nineteenth of April, 1861: A Study of the War, George William Brown cites Johns Hopkins as a wealthy Union man in Baltimore, a city with strong Confederate and Southern leanings]

In The Chronicles of Baltimore

Being a Complete History of "Baltimore Town" and Baltimore City from the Earliest Period to the Present Time published in 1874, John Thomas Scharf cited the 1873 instruction letter to the hospital trustees and a city council resolution thanking Johns Hopkins for his philanthropy. Thom's biography and New York and Maryland newspapers were sources that published parts or all of this letter

"If He Could See Us Now: Mr. Johns Hopkins' Legacy Strong University, Hospital Benefactor Turned 200 on May 19, 1995" by Mike Field a writer for the Johns Hopkins Gazette. Field, Thom, and Jacob called Johns Hopkins an abolitionist. See also The Racial Record of Johns Hopkins University in the Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, No. 25, Autumn, 1999, pp. 42–43/ JSTOR

{{DEFAULTSORT:Hopkins, Johns 1795 births 1873 deaths 19th-century American businesspeople 19th-century American philanthropists American abolitionists American Quakers Burials at Green Mount Cemetery Businesspeople from Baltimore Johns Hopkins University people People from Crofton, Maryland Quaker abolitionists University and college founders

Baltimore

Baltimore is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland. With a population of 585,708 at the 2020 census and estimated at 568,271 in 2024, it is the 30th-most populous U.S. city. The Baltimore metropolitan area is the 20th-large ...

, Maryland, where he remained for most of his life.

Hopkins invested heavily in the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was the oldest railroads in North America, oldest railroad in the United States and the first steam engine, steam-operated common carrier. Construction of the line began in 1828, and it operated as B&O from 1830 ...

(B&O), which eventually led to his appointment as finance director of the company. He was also president of Baltimore-based Merchants' National Bank. Hopkins was a staunch supporter of Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

and the Union, often using his Maryland residence as a gathering place for Union strategists. He was a Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations. Members refer to each other as Friends after in the Bible, and originally, others referred to them as Quakers ...

and supporter of the abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was Kingdom of France, France in 1315, but it was later used ...

cause.

Hopkins was a philanthropist for most of his life. His philanthropic giving increased significantly after the Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

. His concern for the poor and newly freed slave populations drove him to create free medical facilities, orphanages, asylums, and schools to help alleviate the impoverished conditions for all, regardless of race, sex, age, or religion, but especially focused on the young. Following his death, his bequests

A devise is the act of giving real property by will, traditionally referring to real property. A bequest is the act of giving property by will, usually referring to personal property. Today, the two words are often used interchangeably due to thei ...

founded numerous institutions bearing his name, most notably Johns Hopkins Hospital and the Johns Hopkins University

The Johns Hopkins University (often abbreviated as Johns Hopkins, Hopkins, or JHU) is a private university, private research university in Baltimore, Maryland, United States. Founded in 1876 based on the European research institution model, J ...

system, including its academic divisions: Johns Hopkins School of Nursing, Johns Hopkins School of Medicine

The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine (JHUSOM) is the medical school of Johns Hopkins University, a private research university in Baltimore, Maryland. Established in 1893 following the construction of the Johns Hopkins Hospital, th ...

, Johns Hopkins Carey Business School

The Johns Hopkins Carey Business School is the graduate business school of Johns Hopkins University, a private research university in Baltimore, Maryland. It was established in 2007 and offers full-time and part-time programs leading to the M ...

, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

The Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health is the public health graduate school of Johns Hopkins University, a private university, private research university primarily based in Baltimore, Maryland.

It was founded as the Johns Hopkins ...

, and Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies. At the time, it was the largest philanthropic bequest ever made to an American educational institution.

Early life and education

Johns Hopkins was born on May 19, 1795, at his family's home of White's Hall, a tobacco plantation inAnne Arundel County, Maryland

Anne Arundel County (; ), also notated as AA or A.A. County, is located in the U.S. state of Maryland. As of the 2020 United States census, its population was 588,261, an increase of just under 10% since 2010. Its county seat is Annapolis, Mar ...

. His first name was inherited from his grandfather Johns Hopkins, who received his first name from his mother Margaret Johns. He was one of eleven children born to Samuel Hopkins of Crofton, Maryland, and Hannah Janney, of Loudoun County, Virginia

Loudoun County () is in the northern part of the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. In 2020, the census returned a population of 420,959, making it Virginia's third-most populous county. The county seat is Leesburg. Loudoun County ...

.

The Hopkins family were of English and Welsh descent and Quakers

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestantism, Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations. Members refer to each other as Friends after in the Bible, and originally ...

. Hopkins' sister, Sarah Hopkins Janney became a prominent member, and eventually an elder, at Baltimore Quaker Meeting. They emancipated their slaves in 1778 in accordance with their Quaker meeting's decree, which called for freeing the able-bodied and caring for the others, who would remain at the plantation and provide labor as they could. The second eldest of eleven children, Hopkins was required to work on the farm alongside his siblings and indentured and free Black laborers. From 1806 to 1809, he likely attended The Free School of Anne Arundel County, which was located in modern-day Davidsonville, Maryland.

In 1812, at the age of 17, Hopkins left the plantation to work in his uncle Gerard T. Hopkins's Baltimore wholesale grocery business. Gerard T. Hopkins was an established merchant and clerk of the Baltimore Yearly Meeting of Friends. While living with his uncle's family, Johns and his cousin, Elizabeth, fell in love; however, the Quaker taboo against the marriage of first cousins was especially strong, and neither Johns nor Elizabeth ever married.

Career

Hopkins's early experiences and successes in business came when he was put in charge of the store while his uncle was away during theWar of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States United States declaration of war on the Uni ...

. After seven years with his uncle, Hopkins went into business together with Benjamin Moore, a fellow Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations. Members refer to each other as Friends after in the Bible, and originally, others referred to them as Quakers ...

. The business partnership was later dissolved with Moore alleging Hopkins's penchant for capital accumulation

Capital accumulation is the dynamic that motivates the pursuit of profit, involving the investment of money or any financial asset with the goal of increasing the initial monetary value of said asset as a financial return whether in the form ...

as the cause for the divide.

After Moore's withdrawal, Hopkins partnered with three of his brothers and established Hopkins & Brothers Wholesalers in 1819. The company prospered by selling various wares in the Shenandoah Valley

The Shenandoah Valley () is a geographic valley and cultural region of western Virginia and the eastern panhandle of West Virginia in the United States. The Valley is bounded to the east by the Blue Ridge Mountains, to the west by the east ...

from Conestoga wagons, sometimes in exchange for corn whiskey, which was then sold in Baltimore as "Hopkins' Best". The bulk of Hopkins's fortune, however, was made by his judicious investments in myriad ventures, most notably the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was the oldest railroads in North America, oldest railroad in the United States and the first steam engine, steam-operated common carrier. Construction of the line began in 1828, and it operated as B&O from 1830 ...

(B&O), of which he became a director in 1847 and chairman of the Finance Committee in 1855. He was also President of Merchants' Bank as well as director of a number of other organizations. After a successful career, Hopkins was able to retire at the age of 52 in 1847.

A charitable individual, Hopkins put up his own money more than once to not only aid Baltimore City during times of financial crises but also to twice bail the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad company out of debt, in 1857 and 1873.

In 1996, Johns Hopkins ranked 69th in "The Wealthy 100: From Benjamin Franklin to Bill Gates: A Ranking of the Richest Americans, Past and Present".

Civil War

One of the first campaigns of theAmerican Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

was planned at Hopkins's summer estate, Clifton, where he had also entertained a number of foreign dignitaries, including the future King Edward VII. Hopkins was a strong supporter of the Union, unlike some Marylanders, who sympathized with and often supported the South and the Confederacy. During the Civil War, Clifton became a frequent meeting place for local Union sympathizers, and federal officials.

Hopkins' support of Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln (February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was the 16th president of the United States, serving from 1861 until Assassination of Abraham Lincoln, his assassination in 1865. He led the United States through the American Civil War ...

also often put him at odds with some of Maryland's most prominent people, including Supreme Court Justice Roger B. Taney

Roger Brooke Taney ( ; March 17, 1777 – October 12, 1864) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the fifth Chief Justice of the United States, chief justice of the United States, holding that office from 1836 until his death in 186 ...

who continually opposed Lincoln's presidential decisions such as limiting habeas corpus and stationing Union Army troops in Maryland. In 1862, Hopkins wrote a letter to Lincoln requesting that he not heed the detractors' calls and continue to keep soldiers stationed in Maryland. Hopkins also pledged financial and logistic support to Lincoln, in particular the free use of the B&O railway system.

Abolitionism

In 2020,Johns Hopkins University

The Johns Hopkins University (often abbreviated as Johns Hopkins, Hopkins, or JHU) is a private university, private research university in Baltimore, Maryland, United States. Founded in 1876 based on the European research institution model, J ...

researchers discovered that Johns Hopkins may have owned or employed enslaved people who worked in his home and on his country estate, citing census records from 1840 and 1850.

Hopkins's reputation as an abolitionist is currently disputed. In an email sent from Johns Hopkins University to all employees on December 9, 2020, the university wrote that, "The current research done by Martha S. Jones and Allison Seyler finds no evidence to substantiate the description of Johns Hopkins as an abolitionist, and they have explored and brought to light a number of other relevant materials. They have been unable to document the story of Johns Hopkins's parents freeing enslaved people in 1807, but they have found a partial freeing of enslaved people in 1778 by Johns Hopkins's grandfather, and also continued slaveholding and transactions involving enslaved persons for decades thereafter. They have looked more closely at an 1838 letter from the Hopkins Brothers (a firm in which Johns Hopkins was a principal) in which an enslaved person is accepted as collateral for a debt owed, and recently located an additional obituary in which Johns Hopkins is described as holding antislavery political views (consistent with the letter conveying his established support for President Lincoln and the Union) and as purchasing an enslaved person for the purpose of securing his eventual freedom. Still other documents contain laudatory comments by Johns Hopkins's contemporaries, including prominent Black leaders, praising his visionary philanthropic support for the establishment of an orphanage for Black children."

A second group of scholars disputes the university's December 2020 declarations. In a pre-print paper published by the Open Science Framework, these scholars argue that Johns Hopkins's parents and grandparents were devout Quakers who liberated the family's enslaved laborers prior to 1800, that Johns Hopkins was an emancipationist who supported the movement to end slavery within the limits of the laws governing Maryland, and that the available documentation, including relevant tax records these researchers have uncovered, does not support the university's claim that Johns Hopkins was a slaveholder.

Before the discovery of possible slaveholding or employment, Johns Hopkins had been described as being an "abolitionist before the word was even invented", having been represented as such both prior to the Civil War period, as well as during the Civil War and Reconstruction Era. Prior to the Civil War, Johns Hopkins worked closely with two of America's most famous abolitionists, Myrtilla Miner and Henry Ward Beecher. During the Civil War, Johns Hopkins, being a staunch supporter of Lincoln and the Union, was instrumental in bringing fruition to Lincoln's emancipatory vision.

After the Civil War and during Reconstruction

Reconstruction may refer to:

Politics, history, and sociology

*Reconstruction (law), the transfer of a company's (or several companies') business to a new company

*''Perestroika'' (Russian for "reconstruction"), a late 20th century Soviet Union ...

, Johns Hopkins's stance on abolitionism infuriated many prominent people in Baltimore. During Reconstruction and up to his death his abolitionism was expressed in the documents founding the Johns Hopkins Institutions and reported in newspaper articles before, during, and after the founding of these institutions. Before the war, there was significant written opposition to his support for Myrtilla Miner's founding of a school for African American females (now the University of the District of Columbia). In a letter to the editor, one subscriber to the widely circulated De Bow's Review wrote:

Similarly, opposition (and some support) was expressed during Reconstruction, such as in 1867, the same year he filed papers incorporating the Johns Hopkins Institutions, when he attempted unsuccessfully to stop the convening of the Maryland Constitutional Convention where the Democratic Party came into power and where a new state Constitution, the Constitution still in effect, was voted to replace the 1864 Constitution of the Republicans previously in power.

Apparent also in the literature of the times was opposition, and support for, the various other ways he expressed opposition to the racial practices that were beginning to emerge, and re-emerge as well, in the city of Baltimore, the state of Maryland, the nation, and in the posthumously constructed and founded institutions that would carry his name. A '' Baltimore American'' journalist praised Hopkins for founding three institutions, a university, a hospital, and an orphan asylum, specifically for colored children, adding that Hopkins was a "man (beyond his times) who knew no race" citing his provisions for both blacks and whites in the plans for his hospital. The reporter also pointed to similarities between Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin (April 17, 1790) was an American polymath: a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher and Political philosophy, political philosopher.#britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the m ...

's and Johns Hopkins's views on hospital care and construction, such as their shared interest in free hospitals and the availability of emergency services without prejudice. This article, first published in 1870, also accompanied Hopkins's obituary in the ''Baltimore American'' as a tribute in 1873. Cited in many of the newspaper articles on him during his lifetime and immediately after his death were his provisions of scholarships for the poor, and quality health services for the under-served without regard to their age, sex, or color, the colored children asylum and other orphanages, and the mentally ill and convalescents.

A biography, ''Johns Hopkins: A Silhouette'', was written by Hopkins's grandniece, Helen Hopkins Thom, and published in 1929 by Johns Hopkins University Press

Johns Hopkins University Press (also referred to as JHU Press or JHUP) is the publishing division of Johns Hopkins University. It was founded in 1878 and is the oldest continuously running university press in the United States. The press publi ...

. This biography was one source for the story that Hopkins was an abolitionist.

Philanthropy

Hopkins lived his entire adult life in

Hopkins lived his entire adult life in Baltimore

Baltimore is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland. With a population of 585,708 at the 2020 census and estimated at 568,271 in 2024, it is the 30th-most populous U.S. city. The Baltimore metropolitan area is the 20th-large ...

and made many friends among the city's social elite, many of them Quakers

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestantism, Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations. Members refer to each other as Friends after in the Bible, and originally ...

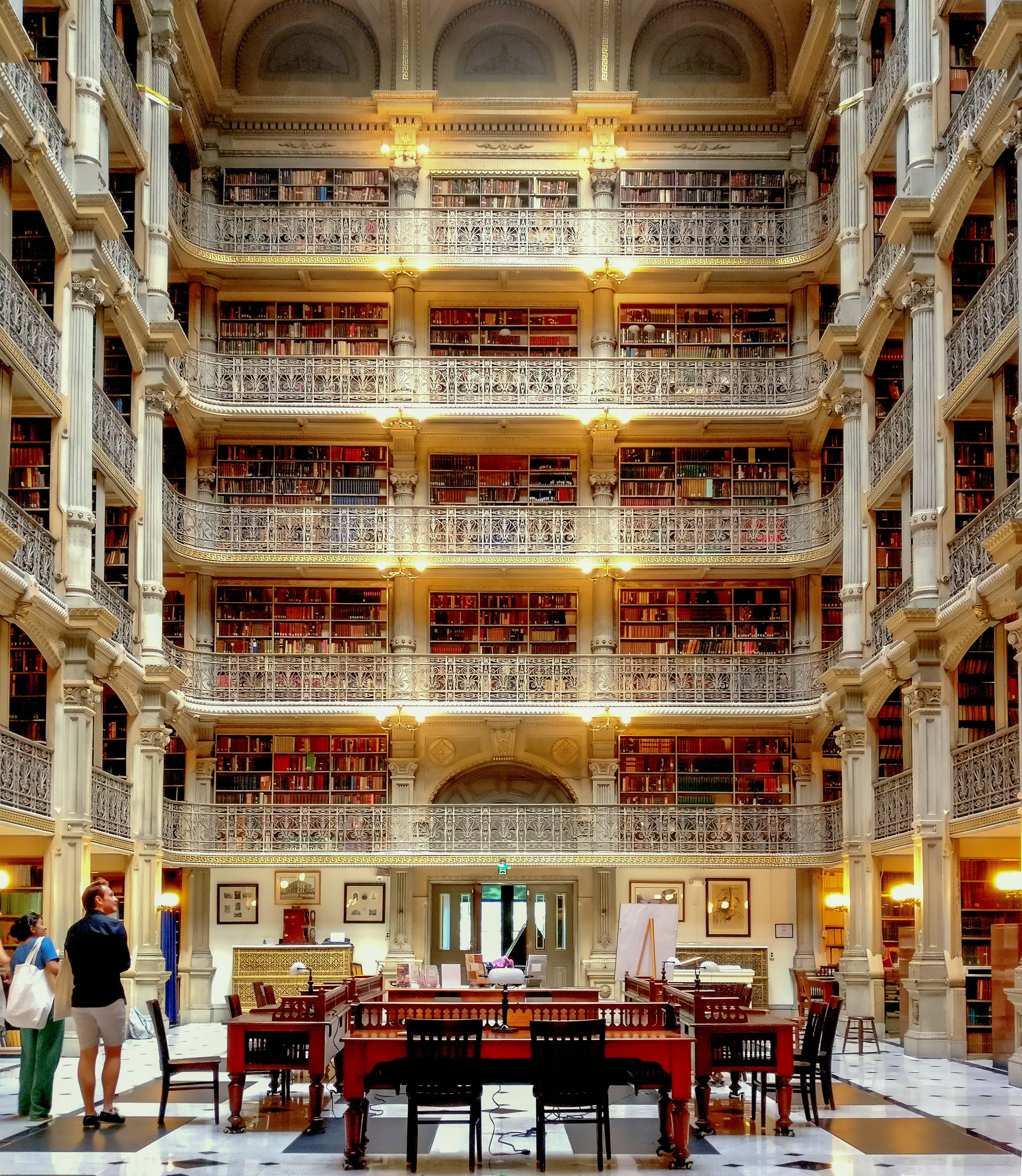

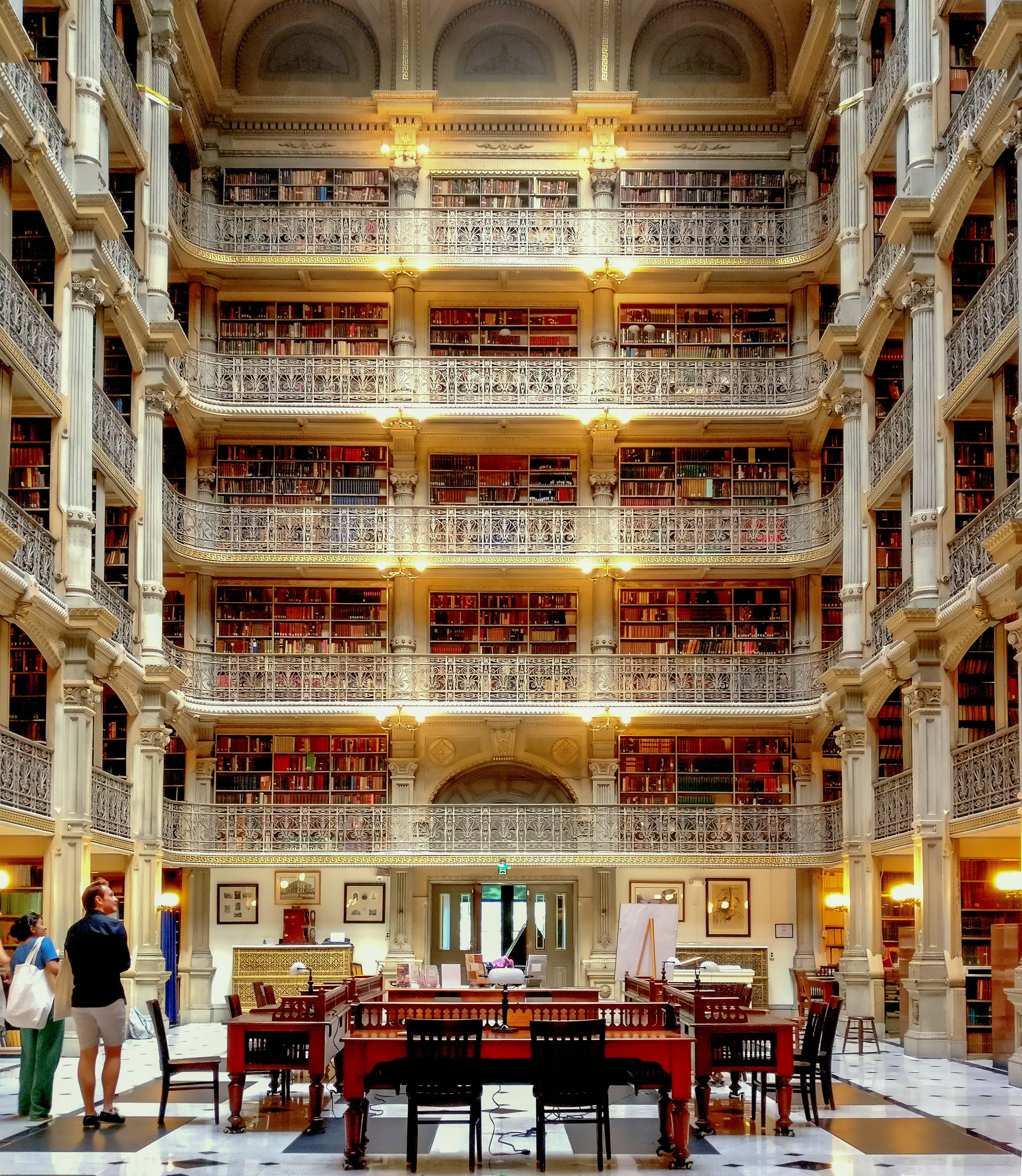

. One of these friends was George Peabody (b. 1795), who in 1857 founded the Peabody Institute

The Peabody Institute of the Johns Hopkins University is a Private university, private music and dance music school, conservatory and College-preparatory school, preparatory school in Baltimore, Maryland. Founded in 1857, it became affiliat ...

in Baltimore. Examples of Hopkins's public giving were evident in Baltimore with public buildings, housing, free libraries, schools, and foundations constructed from his philanthropic giving. On the advice of Peabody, some believe, Hopkins determined to use his great wealth for the public good.

The Civil War and yellow fever and cholera

Cholera () is an infection of the small intestine by some Strain (biology), strains of the Bacteria, bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea last ...

epidemics took a great toll on Baltimore. In the summer of 1832 alone, the yellow fever and cholera epidemics killed 853 in Baltimore. Hopkins was keenly aware of the city's need for medical facilities in light of the medical advances made during the Civil War. In 1870, he made a will setting aside $7 million, (~$ in ) mostly in B&O stock, for the incorporation of a free hospital and affiliated medical and nurses' training colleges, an orphanage for Black children, and a university in Baltimore. The hospital and orphan asylum were overseen by a 12-member hospital board of trustees, and the university by a 12-member university board of trustees. Many board members were on both boards. In accordance with Hopkin's will, the Johns Hopkins Colored Children Orphan Asylum was founded in 1875; Johns Hopkins University

The Johns Hopkins University (often abbreviated as Johns Hopkins, Hopkins, or JHU) is a private university, private research university in Baltimore, Maryland, United States. Founded in 1876 based on the European research institution model, J ...

was founded in 1876; the Johns Hopkins Press, the longest continuously operating academic press in the U.S., was founded in 1878; Johns Hopkins Hospital and Johns Hopkins School of Nursing were founded in 1889; the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine was founded in 1893; and the Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health was founded in 1916.

Hopkin's views on his bequests, and on the duties and responsibilities of the two boards of trustees, especially the hospital board of trustees led by his friend and fellow Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations. Members refer to each other as Friends after in the Bible, and originally, others referred to them as Quakers ...

Francis T. King, were formally stated primarily in four documents, the incorporation papers filed in 1867, his instruction letter to the hospital trustees dated March 12, 1873, his will, which was quoted extensively in his '' Baltimore Sun'' obituary, and in his will's two codicils, one dated 1870 and a second dated 1873.

In these documents, Hopkins made provisions for scholarships to be provided for poor youths in the states where he had made his wealth and assistance to orphanages other than the one established for African American children, to members of his family, to those he employed, his cousin Elizabeth, to other institutions for the care and education of youths regardless of color, and the care of the elderly and the ill, including the mentally ill and convalescents.

John Rudolph Niernsee, one of the most notable architects of the time, designed the orphan asylum and helped to design the Johns Hopkins Hospital. The original site for Johns Hopkins University had been personally selected by Hopkins. According to his will, it was to be located at his summer estate, Clifton. However, a decision was made not to found the university there. The property, now owned by the city of Baltimore, is the site of a golf course and a park named Clifton Park. While Johns Hopkins Colored Children Orphan Asylum was founded by the hospital trustees, the other institutions that carry the name of Johns Hopkins were founded under the administration of Daniel Coit Gilman, the first president of Johns Hopkins University

The Johns Hopkins University (often abbreviated as Johns Hopkins, Hopkins, or JHU) is a private university, private research university in Baltimore, Maryland, United States. Founded in 1876 based on the European research institution model, J ...

and Johns Hopkins Hospital, and Gilman's successors.

Colored Children Orphan Asylum

As stipulated in Hopkins's instruction letter, the Johns Hopkins Colored Children Orphan Asylum (JHCCOA) was founded first, in 1875, a year before Gilman's inauguration. The construction of the asylum, including its educational and living facilities, was praised by ''The Nation

''The Nation'' is a progressive American monthly magazine that covers political and cultural news, opinion, and analysis. It was founded on July 6, 1865, as a successor to William Lloyd Garrison's '' The Liberator'', an abolitionist newspaper ...

'' and the ''Baltimore American''. The ''Baltimore American'' wrote that the orphan asylum was a place where "nothing was wanting that could benefit science and humanity". As was done for other Johns Hopkins institutions, it was planned after visits and correspondence with similar institutions in Europe and the U.S.

The Johns Hopkins Orphan Asylum opened with 24 boys and girls. Under Gilman and his successors, the orphanage was later changed to serve as an orphanage and training school for Black female orphans principally as domestic workers and as an orthopiedic convalescent home and school for "colored crippled" children and orphans. The asylum was eventually closed in 1924 nearly 50 years after it opened.

Hospital, university, press, and schools of nursing and medicine

In accordance with Hopkins' March 1873 instruction letter, the school of nursing was founded alongside the hospital in 1889 by the hospital board of trustees in consultation withFlorence Nightingale

Florence Nightingale (; 12 May 1820 – 13 August 1910) was an English Reform movement, social reformer, statistician and the founder of modern nursing. Nightingale came to prominence while serving as a manager and trainer of nurses during th ...

. Both the nursing school and the hospital were founded over a decade after the founding of the orphan asylum in 1875 and the university in 1876. Hopkins's instruction letter explicitly stated his vision for the hospital; first, to provide assistance to the poor of "all races", no matter the indigent patient's "age, sex or color"; second, that wealthier patients would pay for services and thereby subsidize the care provided to the indigent; third, that the hospital would be the administrative unit for the orphan asylum for African American children, which was to receive $25,000 in annual support out of the hospital's half of the endowment; and fourth, that the hospital and orphan asylum should serve 400 patients and 400 children respectively; fifth, that the hospital should be part of the university, and, sixth, that religion but not sectarianism should be an influence in the hospital.

By the end of Gilman's presidency, Johns Hopkins University, Johns Hopkins Press, Johns Hopkins Hospital and Johns Hopkins School of Nursing, and Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, and Johns Hopkins Colored Children Orphan Asylum had been founded; the latter by the trustees, and the others in the order listed under the Gilman administration. "Sex" and "color" were major issues in the early history of the Johns Hopkins Institutions. The founding of the school of nursing is usually linked to Johns Hopkins's statements in his March 1873 instruction letter to the trustees that: "I desire you to establish, in connection with the hospital, a training school for female nurses. This provision will secure the services of women competent to care for those sick in the hospital wards, and will enable you to benefit the whole community by supplying it with a class of trained and experienced nurses".

Legacy

Hopkins died on December 24, 1873, in

Hopkins died on December 24, 1873, in Baltimore

Baltimore is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland. With a population of 585,708 at the 2020 census and estimated at 568,271 in 2024, it is the 30th-most populous U.S. city. The Baltimore metropolitan area is the 20th-large ...

.

Following Hopkins's death, ''The Baltimore Sun

''The Baltimore Sun'' is the largest general-circulation daily newspaper based in the U.S. state of Maryland and provides coverage of local, regional, national, and international news.

Founded in 1837, the newspaper was owned by Tribune Publi ...

'' published a lengthy obituary that reported, "In the death of Johns Hopkins a career has been closed which affords a rare example of successful energy in individual accumulations, and of practical beneficence in devoting the gains thus acquired to the public." Hopkins' contribution to the founding of Johns Hopkins University

The Johns Hopkins University (often abbreviated as Johns Hopkins, Hopkins, or JHU) is a private university, private research university in Baltimore, Maryland, United States. Founded in 1876 based on the European research institution model, J ...

become his greatest legacy and was the largest philanthropic bequest ever made to a U.S. educational institution.

Hopkins' Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations. Members refer to each other as Friends after in the Bible, and originally, others referred to them as Quakers ...

faith and early life experiences, including the 1778 emancipation, had a lasting influence on him throughout his life. Beginning early in his life, Hopkins looked upon his wealth as a trust to benefit future generations. He told his gardener that, "Like the man in the parable, I have had many talents given to me and I feel they are in trust. I shall not bury them but give them to the lads who long for a wider education". His philosophy quietly anticipated Andrew Carnegie

Andrew Carnegie ( , ; November 25, 1835August 11, 1919) was a Scottish-American industrialist and philanthropist. Carnegie led the expansion of the History of the iron and steel industry in the United States, American steel industry in the late ...

's much-publicized ''Gospel of Wealth

"Wealth", more commonly known as "The Gospel of Wealth", is an essay written by Andrew Carnegie in June of 1889 that describes the responsibility of philanthropy by the Nouveau riche, new upper class of self-made rich. The article was published ...

'' by more than 25 years.

In 1973, Johns Hopkins was cited prominently in the Pulitzer Prize

The Pulitzer Prizes () are 23 annual awards given by Columbia University in New York City for achievements in the United States in "journalism, arts and letters". They were established in 1917 by the will of Joseph Pulitzer, who had made his fo ...

-winning book ''The Americans: The Democratic Experience'' by Daniel Boorstin, the Librarian of Congress

The librarian of Congress is the head of the Library of Congress, appointed by the president of the United States with the advice and consent of the United States Senate, for a term of ten years. The librarian of Congress also appoints and overs ...

from 1975 to 1987. From November 14, 1975, to September 6, 1976, a portrait of Hopkins was displayed at the National Portrait Gallery in an exhibit on the democratization of America based on Boorstin's book. In 1989, the United States Postal Service

The United States Postal Service (USPS), also known as the Post Office, U.S. Mail, or simply the Postal Service, is an independent agencies of the United States government, independent agency of the executive branch of the federal governmen ...

issued a $1 postage stamp in Hopkins' honor, as part of the Great Americans series.

Notes

References

External links

Hopkins Family Papers, Sheridan Libraries, Johns Hopkins University

* [https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?doc=Perseus:text:2001.01.0027 In his 1887 memoir, Baltimore and the Nineteenth of April, 1861: A Study of the War, George William Brown cites Johns Hopkins as a wealthy Union man in Baltimore, a city with strong Confederate and Southern leanings]

In The Chronicles of Baltimore

Being a Complete History of "Baltimore Town" and Baltimore City from the Earliest Period to the Present Time published in 1874, John Thomas Scharf cited the 1873 instruction letter to the hospital trustees and a city council resolution thanking Johns Hopkins for his philanthropy. Thom's biography and New York and Maryland newspapers were sources that published parts or all of this letter

"If He Could See Us Now: Mr. Johns Hopkins' Legacy Strong University, Hospital Benefactor Turned 200 on May 19, 1995" by Mike Field a writer for the Johns Hopkins Gazette. Field, Thom, and Jacob called Johns Hopkins an abolitionist. See also The Racial Record of Johns Hopkins University in the Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, No. 25, Autumn, 1999, pp. 42–43/ JSTOR

{{DEFAULTSORT:Hopkins, Johns 1795 births 1873 deaths 19th-century American businesspeople 19th-century American philanthropists American abolitionists American Quakers Burials at Green Mount Cemetery Businesspeople from Baltimore Johns Hopkins University people People from Crofton, Maryland Quaker abolitionists University and college founders