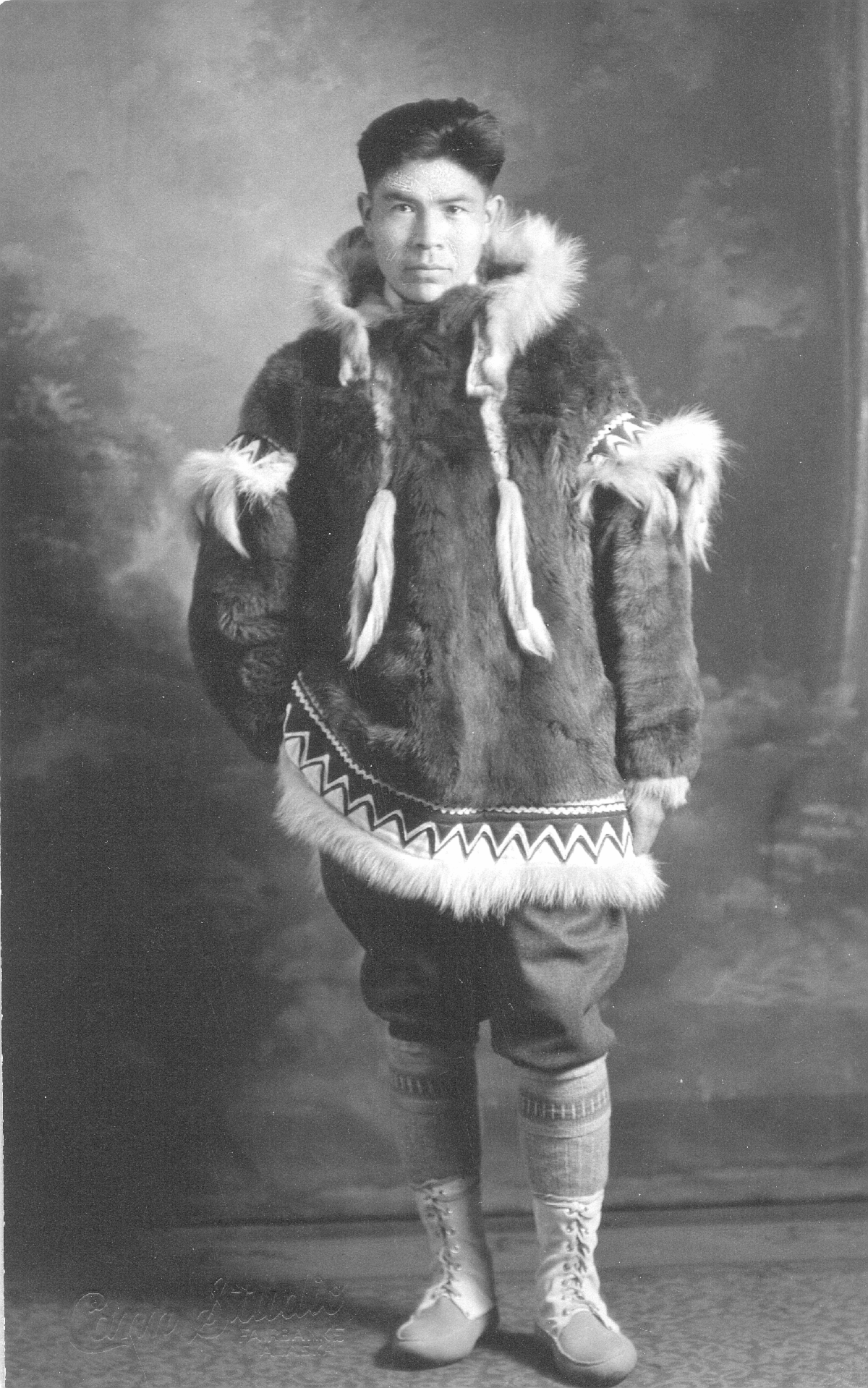

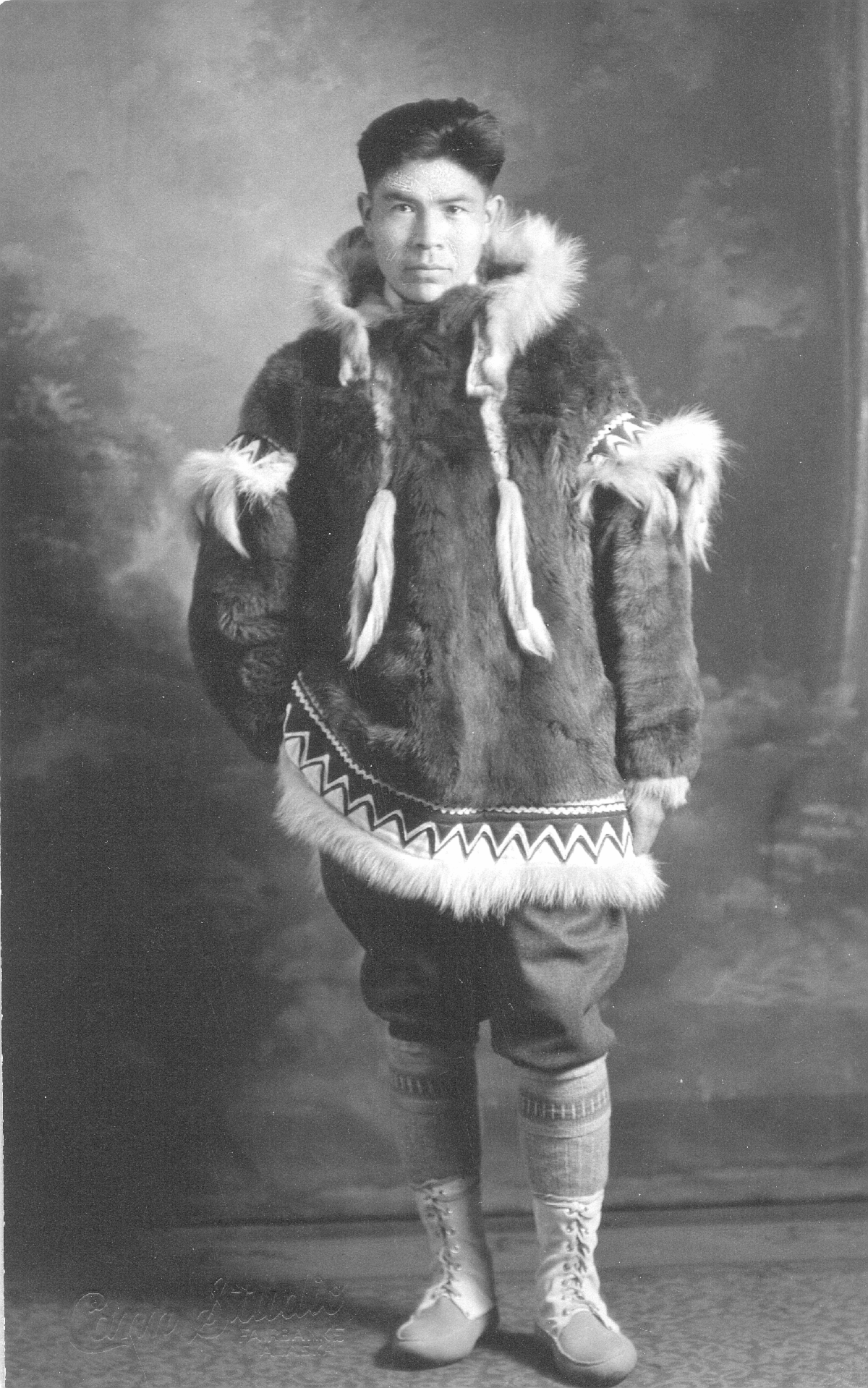

Johnny Fredson on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Fredson (born 1896, as Neetsaii Gwich'in - August 22, 1945), was a tribal leader born near Table Mountain in the Sheenjek River watershed of the state of

John Fredson (born 1896, as Neetsaii Gwich'in - August 22, 1945), was a tribal leader born near Table Mountain in the Sheenjek River watershed of the state of

Clara Childs Mackenzie, ''Wolf Smeller: A Biography of John Fredson, Native Alaskan''

Alaska Pacific University, 1985 He attended

John Fredson (born 1896, as Neetsaii Gwich'in - August 22, 1945), was a tribal leader born near Table Mountain in the Sheenjek River watershed of the state of

John Fredson (born 1896, as Neetsaii Gwich'in - August 22, 1945), was a tribal leader born near Table Mountain in the Sheenjek River watershed of the state of Alaska

Alaska ( ) is a non-contiguous U.S. state on the northwest extremity of North America. Part of the Western United States region, it is one of the two non-contiguous U.S. states, alongside Hawaii. Alaska is also considered to be the north ...

, United States. He is most noted for gaining federal recognition for the Venetie

Venetie ( ;Corey Goldberg," ''New York Times'', May 9, 1997. ''Vįįhtąįį'' in Gwich’in), is a census-designated place (CDP) in Yukon–Koyukuk Census Area, Alaska. At the 2010 census, the population was 166, down from 202 in 2000. It inc ...

Indian Reserve in 1941, then the largest reservation __NOTOC__

Reservation may refer to: Places

Types of places:

* Indian reservation, in the United States

* Military base, often called reservations

* Nature reserve

Government and law

* Reservation (law), a caveat to a treaty

* Reservation in India, ...

in Alaska, and containing approximately 1.4 million acres (5,700 km). This was before Alaska was admitted as a state.

As a youth, Fredson had taken part in Hudson Stuck

Hudson Stuck (November 4, 1863 – October 10, 1920) was a British native who became an Episcopal priest, social reformer and mountain climber in the United States. With Harry P. Karstens, he co-led the first expedition to successfully climb Den ...

's expedition to climb Denali

Denali (), federally designated as Mount McKinley, is the highest mountain peak in North America, with a summit elevation of above sea level. It is the tallest mountain in the world from base to peak on land, measuring . On p. 20 of Helm ...

, and served as base camp manager. Afterward Stuck sponsored him for college, and he attended Sewanee, The University of the South

The University of the South, familiarly known as Sewanee (), is a private Episcopal liberal arts college in Sewanee, Tennessee, United States. It is owned by 28 southern dioceses of the Episcopal Church, and its School of Theology is an off ...

, becoming the first Alaska Native

Alaska Natives (also known as Native Alaskans, Alaskan Indians, or Indigenous Alaskans) are the Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Indigenous peoples of Alaska that encompass a diverse arena of cultural and linguistic groups, including the I ...

to graduate from college. Fredson returned to Alaska, where he worked in a hospital and as a teacher, becoming a leader and political activist.

Early life and education

Born in 1896 to a Gwich'in family near Table Mountain in what is now designated as Yukon-Koyukuk Census Area, Alaska, John Fredson grew up speaking Gwich'in as his first language. Orphaned at a young age, he attended a mission school operated by theEpiscopal Church of the United States

The Episcopal Church (TEC), also known as the Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America (PECUSA), is a member of the worldwide Anglican Communion, based in the United States. It is a mainline Protestant denomination and is ...

, where he learned English. From an early age, he became highly skilled in following trails, climbing and hunting.

At the age of 16, Fredson was part of the 1913 climbing expedition of Hudson Stuck

Hudson Stuck (November 4, 1863 – October 10, 1920) was a British native who became an Episcopal priest, social reformer and mountain climber in the United States. With Harry P. Karstens, he co-led the first expedition to successfully climb Den ...

, Episcopal Archdeacon of the Yukon, who led the party that ascended Denali

Denali (), federally designated as Mount McKinley, is the highest mountain peak in North America, with a summit elevation of above sea level. It is the tallest mountain in the world from base to peak on land, measuring . On p. 20 of Helm ...

, the highest peak in North America. Fredson was the base camp

Mountaineering, mountain climbing, or alpinism is a set of outdoor activities that involves ascending mountains. Mountaineering-related activities include traditional outdoor climbing, skiing, and traversing via ferratas that have become sp ...

manager. His role is documented in Stuck's book, '' Ascent of Denali'' (reprint 2005). Fredson stayed at base at camp for 31 days by himself, hunting caribou

The reindeer or caribou (''Rangifer tarandus'') is a species of deer with circumpolar distribution, native to Arctic, subarctic, tundra, boreal, and mountainous regions of Northern Europe, Siberia, and North America. It is the only represe ...

and Dall sheep

''Ovis dalli'', also known as the Dall sheep or thinhorn sheep, is a species of wild sheep native to northwestern North America. ''Ovis dalli'' contains two subspecies: ''Ovis dalli dalli'' and ''Stone sheep, Ovis dalli stonei''. ''O. dalli'' li ...

, while awaiting the return of the climbing party. He saved his ration of sugar for their return.

With Stuck's encouragement, Fredson gained more formal education, becoming the first native of Athabascan

Athabaskan ( ; also spelled ''Athabascan'', ''Athapaskan'' or ''Athapascan'', and also known as Dene) is a large branch of the Na-Dene language family of North America, located in western North America in three areal language groups: Northern, ...

descent to complete high school.Alaska Pacific University, 1985 He attended

Sewanee, The University of the South

The University of the South, familiarly known as Sewanee (), is a private Episcopal liberal arts college in Sewanee, Tennessee, United States. It is owned by 28 southern dioceses of the Episcopal Church, and its School of Theology is an off ...

, an Episcopal college in Middle Tennessee

Middle Tennessee is one of the three Grand Divisions of Tennessee that composes roughly the central portion of the state. It is delineated according to state law as 41 of the state's 95 counties. Middle Tennessee contains the state's capital an ...

, and was the first Alaska Native

Alaska Natives (also known as Native Alaskans, Alaskan Indians, or Indigenous Alaskans) are the Indigenous peoples of the Americas, Indigenous peoples of Alaska that encompass a diverse arena of cultural and linguistic groups, including the I ...

to graduate from a university.

While there, Fredson worked with Edward Sapir

Edward Sapir (; January 26, 1884 – February 4, 1939) was an American anthropologist-linguistics, linguist, who is widely considered to be one of the most important figures in the development of the discipline of linguistics in the United States ...

, a noted linguist

Linguistics is the scientific study of language. The areas of linguistic analysis are syntax (rules governing the structure of sentences), semantics (meaning), Morphology (linguistics), morphology (structure of words), phonetics (speech sounds ...

, and helped to classify Gwich'in within the Na-Dene

Na-Dene ( ; also Nadene, Na-Dené, Athabaskan–Eyak–Tlingit, Tlina–Dene) is a family of Native American languages that includes at least the Athabaskan languages, Eyak, and Tlingit languages. Haida was formerly included but is now general ...

language family. This work is documented in the book ''John Fredson Edward Sapir Ha'a Googwandak'' (1982), a collection of stories that Fredson told to Sapir. His work on communicating Gwich'in concepts of space and time may have also influenced Sapir's later work that established the Sapir–Whorf hypothesis

Linguistic relativity asserts that language influences worldview or cognition. One form of linguistic relativity, linguistic determinism, regards peoples' languages as determining and influencing the scope of cultural perceptions of their surrou ...

.

Life's work

After his return to Alaska, Fredson worked at a hospital inFort Yukon

Fort Yukon (''Gwichyaa Zheh'' in Gwich'in language, Gwich'in) is a city in the Yukon-Koyukuk Census Area, Alaska, Yukon-Koyukuk Census Area in the U.S. state of Alaska, straddling the Arctic Circle. The population, predominantly Gwich'in Alaska ...

. In his later years, Fredson built a solarium

Solarium may refer to:

* A sunroom, a room built largely of glass to afford exposure to the sun

* A terrace (building) or flat housetop

* The '' Solarium Augusti'', a monumental meridian line (or perhaps a sundial) erected in Rome by Emperor Aug ...

for tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

patients at the hospital. Then the only hospital in the far north, the facility was often overwhelmed by Alaska Native patients, primarily Gwich’in. They needed treatment for Eurasian infectious diseases

infection is the invasion of tissues by pathogens, their multiplication, and the reaction of host tissues to the infectious agent and the toxins they produce. An infectious disease, also known as a transmissible disease or communicable dise ...

, to which they had no immunity

Immunity may refer to:

Medicine

* Immunity (medical), resistance of an organism to infection or disease

* ''Immunity'' (journal), a scientific journal published by Cell Press

Biology

* Immune system

Engineering

* Radiofrequence immunity ...

.

Fredson taught school in the village of Venetie, and taught the community how to grow gardens. He was assisted by Chief Johnny Frank, a notable medicine man

A medicine man (from Ojibwe ''mashkikiiwinini'') or medicine woman (from Ojibwe ''mashkikiiwininiikwe'') is a traditional healer and spiritual leader who serves a community of Indigenous people of the Americas. Each culture has its own name i ...

and storyteller among the Gwich'in. The chief's exploits are recounted in the book '' Neerihiinjik: We Traveled From Place to Place'' (2012).

Fredson became a tribal leader, working to re-establish his people's rights to their traditional lands. He was the primary founder of the Venetie

Venetie ( ;Corey Goldberg," ''New York Times'', May 9, 1997. ''Vįįhtąįį'' in Gwich’in), is a census-designated place (CDP) in Yukon–Koyukuk Census Area, Alaska. At the 2010 census, the population was 166, down from 202 in 2000. It inc ...

Indian Reserve, the largest reservation __NOTOC__

Reservation may refer to: Places

Types of places:

* Indian reservation, in the United States

* Military base, often called reservations

* Nature reserve

Government and law

* Reservation (law), a caveat to a treaty

* Reservation in India, ...

in Alaska. It achieved federal recognition in 1941, before Alaska was admitted as a state. The Reserve was approximately 1.4 million acres (5,700 km) when it was established.

Family life

John married Jean Ribaloff, a woman whom he met while at the hospital in Fort Yukon. They had three children, William Burke Fredson, Virginia Fredson (Dows), and Lula Fredson (Young

Young may refer to:

* Offspring, the product of reproduction of a new organism produced by one or more parents

* Youth, the time of life when one's age is low, often meaning the time between childhood and adulthood

Music

* The Young, an America ...

). Fredson died of pneumonia

Pneumonia is an Inflammation, inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as Pulmonary alveolus, alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of Cough#Classification, productive or dry cough, ches ...

at about age 49 on August 22, 1945.

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Fredson, John 1896 births 1945 deaths 20th-century Alaska Native people 20th-century Native American leaders Schoolteachers from Alaska Deaths from pneumonia in Alaska Native American leaders People from Fort Yukon, Alaska 20th-century American educators American Gwich'in people