John Knox on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Knox ( – 24 November 1572) was a Scottish minister,

In England, Knox met his wife, Margery Bowes (died ). Her father, Richard Bowes (died 1558), was a descendant of an old

In England, Knox met his wife, Margery Bowes (died ). Her father, Richard Bowes (died 1558), was a descendant of an old

Free Online Access to Works of John Knox

. * * * *

John Knox Book on Predestination

'

Querelle , John Knox

Querelle.ca is a website devoted to the works of authors contributing to the pro-woman side of the ''querelle des femmes''. {{DEFAULTSORT:Knox, John 1510s births 1572 deaths Year of birth uncertain 16th-century Calvinist and Reformed theologians 16th-century ministers of the Church of Scotland 16th-century Scottish Presbyterian ministers 16th-century Scottish theologians 16th-century Scottish writers 16th-century Scottish male writers Alumni of the University of Glasgow Alumni of the University of St Andrews Critics of the Catholic Church Founders of religions Moderators of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland People from Haddington, East Lothian Protestant Reformers Scottish Calvinist and Reformed theologians Scottish Reformation Scottish evangelicals Burials at the kirkyard of St Giles Ministers of St Giles' Cathedral Galley slaves

Reformed theologian

Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. In the modern day, it is largely represented by the Continental Reformed Protestantism, Continenta ...

, and writer who was a leader of the country's Reformation. He was the founder of the Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland (CoS; ; ) is a Presbyterian denomination of Christianity that holds the status of the national church in Scotland. It is one of the country's largest, having 245,000 members in 2024 and 259,200 members in 2023. While mem ...

.

Born in Giffordgate, a street in Haddington, East Lothian

The Royal Burgh of Haddington (, ) is a town in East Lothian, Scotland. It is the main administrative, cultural and geographical centre for East Lothian. It lies about east of Edinburgh. The name Haddington is Anglo-Saxon, dating from the six ...

, Knox is believed to have been educated at the University of St Andrews

The University of St Andrews (, ; abbreviated as St And in post-nominals) is a public university in St Andrews, Scotland. It is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, oldest of the four ancient universities of Scotland and, f ...

and worked as a notary

A notary is a person authorised to perform acts in legal affairs, in particular witnessing signatures on documents. The form that the notarial profession takes varies with local legal systems.

A notary, while a legal professional, is distin ...

-priest

A priest is a religious leader authorized to perform the sacred rituals of a religion, especially as a mediatory agent between humans and one or more deity, deities. They also have the authority or power to administer religious rites; in parti ...

. Influenced by early church reformers such as George Wishart

George Wishart (also Wisehart; c. 15131 March 1546) was a Scottish Protestant Reformer and one of the early Protestant martyrs burned at the stake as a heretic.

George Wishart was the son of James and brother of Sir John of Pitarrow ...

, he joined the movement to reform

Reform refers to the improvement or amendment of what is wrong, corrupt, unsatisfactory, etc. The modern usage of the word emerged in the late 18th century and is believed to have originated from Christopher Wyvill's Association movement, which ...

the Scottish Church. He was caught up in the and political events that involved the murder of Cardinal David Beaton

David Beaton (also Beton or Bethune; 29 May 1546) was Archbishop of St Andrews and the last Scottish cardinal prior to the Reformation.

Life

David Beaton was said to be the fifth son of fourteen children born to John Beaton (Bethune) of Balf ...

in 1546 and the intervention of the regent

In a monarchy, a regent () is a person appointed to govern a state because the actual monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge their powers and duties, or the throne is vacant and a new monarch has not yet been dete ...

Mary of Guise

Mary of Guise (; 22 November 1515 – 11 June 1560), also called Mary of Lorraine, was List of Scottish royal consorts, Queen of Scotland from 1538 until 1542, as the second wife of King James V. She was a French people, French noblewoman of the ...

. He was taken prisoner by French forces the following year and exiled to England on his release in 1549.

While in exile, Knox was licensed to work in the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

, where he rose in the ranks to serve King Edward VI

Edward VI (12 October 1537 – 6 July 1553) was King of England and King of Ireland, Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death in 1553. He was crowned on 20 February 1547 at the age of nine. The only surviving son of Henry VIII by his thi ...

of England as a royal chaplain

A royal chapel is a chapel associated with a monarch, a royal court, or in a royal palace.

A royal chapel may also be a body of clergy or musicians serving at a royal court or employed by a monarch.

Commonwealth countries

Both the United King ...

. He exerted a reforming influence on the text of the ''Book of Common Prayer

The ''Book of Common Prayer'' (BCP) is the title given to a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion and by other Christianity, Christian churches historically related to Anglicanism. The Book of Common Prayer (1549), fi ...

''. In England, he met and married his first wife, Margery Bowes. When Queen Mary I

Mary I (18 February 1516 – 17 November 1558), also known as Mary Tudor, was Queen of England and Ireland from July 1553 and Queen of Spain as the wife of King Philip II from January 1556 until her death in 1558. She made vigorous a ...

ascended the throne of England and re-established Catholicism

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

, Knox was forced to resign his position and leave the country. Knox moved to Geneva

Geneva ( , ; ) ; ; . is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland and the most populous in French-speaking Romandy. Situated in the southwest of the country, where the Rhône exits Lake Geneva, it is the ca ...

and then to Frankfurt

Frankfurt am Main () is the most populous city in the States of Germany, German state of Hesse. Its 773,068 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the List of cities in Germany by population, fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located in the forela ...

. In Geneva, he met John Calvin

John Calvin (; ; ; 10 July 150927 May 1564) was a French Christian theology, theologian, pastor and Protestant Reformers, reformer in Geneva during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system of C ...

, from whom he gained experience and knowledge of Reformed theology

Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the 16th-century Protestant Reformation. In the modern day, it is largely represented by the Continental Reformed Protestantism, Continenta ...

and presbyterian polity

Presbyterian (or presbyteral) polity is a method of church governance (" ecclesiastical polity") typified by the rule of assemblies of presbyters, or elders. Each local church is governed by a body of elected elders usually called the session ...

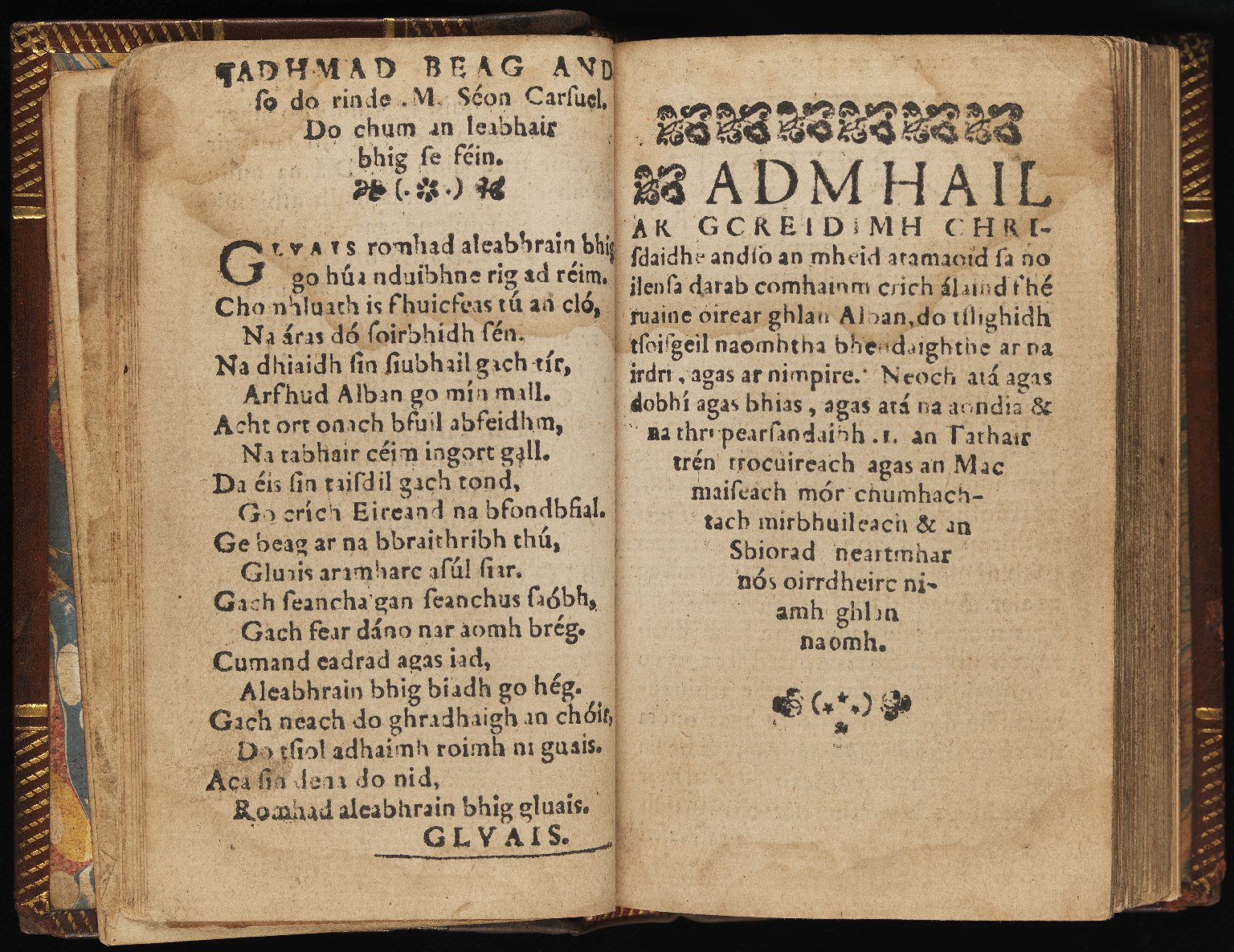

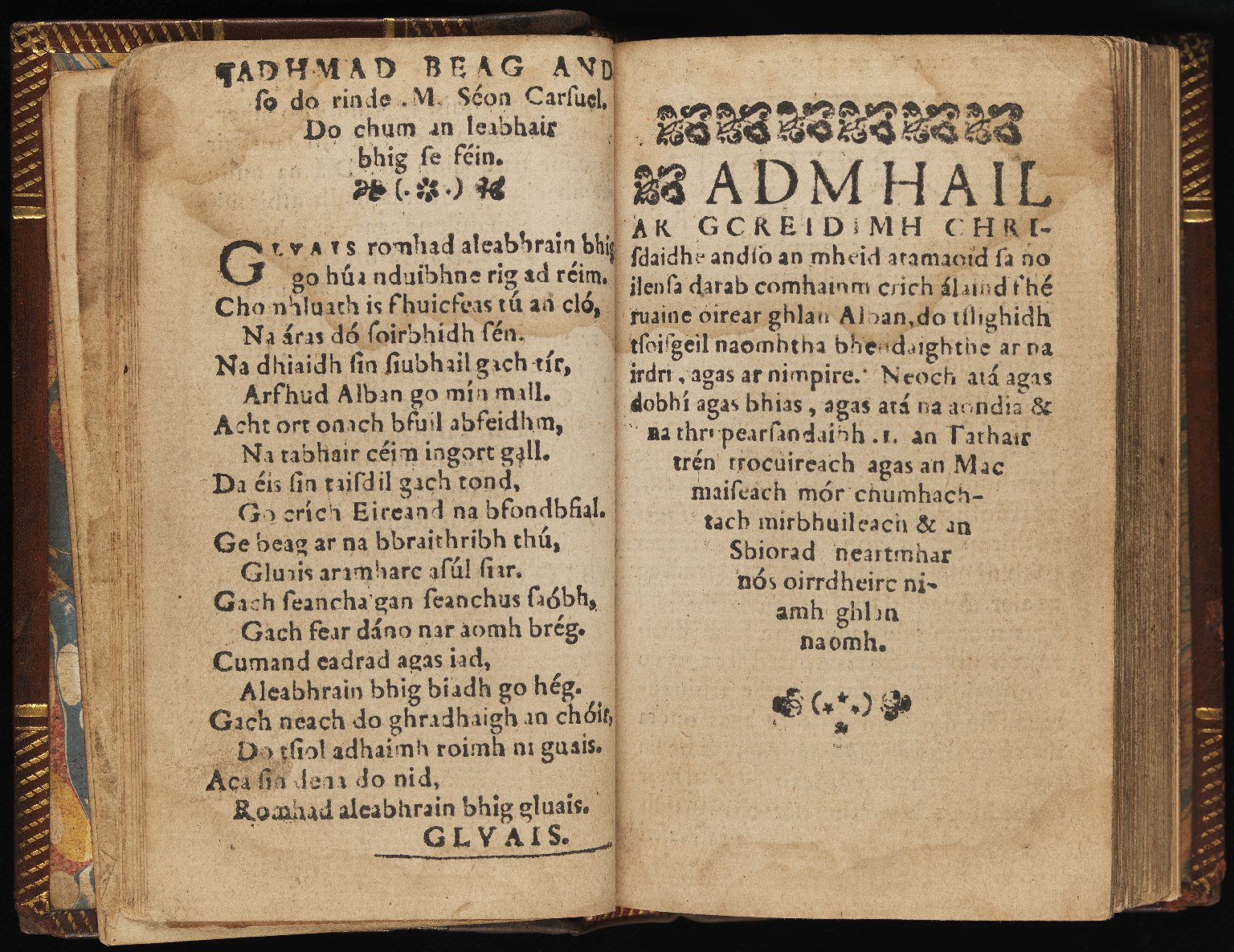

. He created a new order of service, ''The Forme of Prayers'', which was eventually adopted by the Reformed Church in Scotland and came to be known as the ''Book of Common Order

The ''Book of Common Order'', originally titled ''The Forme of Prayers'', is a liturgical book by John Knox written for use in the Calvinism, Reformed denomination. The text was composed in Geneva in 1556 and was adopted by the Church of Scotla ...

''. It was the first book printed in any Gaelic language

The Goidelic ( ) or Gaelic languages (; ; ) form one of the two groups of Insular Celtic languages, the other being the Brittonic languages.

Goidelic languages historically formed a dialect continuum stretching from Ireland through the Isle o ...

. Knox left Geneva to head the English refugee church in Frankfurt but he was forced to leave over differences concerning the liturgy

Liturgy is the customary public ritual of worship performed by a religious group. As a religious phenomenon, liturgy represents a communal response to and participation in the sacred through activities reflecting praise, thanksgiving, remembra ...

, thus ending his association with the Church of England.

On his return to Scotland, Knox led the Protestant Reformation in Scotland, in partnership with the Scottish Protestant nobility

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally appointed by and ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. T ...

. The movement may be seen as a revolution since it led to the ousting of Mary of Guise, who governed the country in the name of her young daughter Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was List of Scottish monarchs, Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legit ...

. Knox helped write the new confession of faith

A creed, also known as a confession of faith, a symbol, or a statement of faith, is a statement of the shared beliefs of a community (often a religious community) which summarizes its core tenets.

Many Christian denominations use three creeds: ...

and the ecclesiastical order for the newly created Reformed Church, the Kirk

The Church of Scotland (CoS; ; ) is a Presbyterian denomination of Christianity that holds the status of the national church in Scotland. It is one of the country's largest, having 245,000 members in 2024 and 259,200 members in 2023. While mem ...

. He wrote his five-volume '' The History of the Reformation in Scotland'' between 1559 and 1566. He continued to serve as the religious leader of the Protestants throughout Mary's reign. In several interviews with the Queen, Knox admonished her for supporting Catholic practices. After she was imprisoned for her alleged role in the murder of her husband Lord Darnley

Lord Darnley is a noble title associated with a Scottish Lordship of Parliament, first created in 1356 for the family of Stewart of Darnley and tracing a descent to the Dukedom of Richmond in England. The title's name refers to Darnley in Scot ...

, and King James VI

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 – 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 March 1603 until ...

was enthroned in her stead, Knox openly called for her execution. He continued to preach until his final days.

Early life, 1505–1546

John Knox was born sometime between 1505 and 1515; . UntilDavid Hay Fleming

David Hay Fleming, LL.D. (1849–1931) was a Scottish historian and antiquary.

Biography

Fleming came from St Andrews, a university town in East Fife and was educated at Madras College secondary school. His family had a china and stoneware bu ...

published new research in 1904, John Knox was thought to have been born in 1505. Hay Fleming's conclusion was that Knox was born between 1513 and 1515. Sources using this date include and . Ridley notes additional research supports the later date which is now generally accepted by historians. However, some recent books on more general topics still give the earlier date for his birth or a wide range of possibility; for example: Arthur. F. Kinney and David. W. Swain (eds.)(2000), ''Tudor England: an Encyclopedia,'' p. 412 (between 1505 and 1515); M. E. Wiesner-Hanks (2006), ''Early Modern Europe, 1450–1789'', Cambridge University Press, p. 170 (1505?); and Michael. A. Mullet (1989), ''Calvin'', Routledge, p. 64 (1505). in or near Haddington, the county town

In Great Britain and Ireland, a county town is usually the location of administrative or judicial functions within a county, and the place where public representatives are elected to parliament. Following the establishment of county councils in ...

of East Lothian

East Lothian (; ; ) is one of the 32 council areas of Scotland, as well as a Counties of Scotland, historic county, registration county and Lieutenancy areas of Scotland, lieutenancy area. The county was called Haddingtonshire until 1921.

In ...

. His father, William Knox, was a merchant. All that is known of his mother is that her maiden name was Sinclair and that she died when John Knox was a child. Their eldest son, William, carried on his father's business, which helped in Knox's international communications.

Knox was probably educated at the grammar school in Haddington. At this time, the priesthood was the only path for those whose inclinations were academic rather than mercantile or agricultural. He proceeded to further studies at the University of St Andrews

The University of St Andrews (, ; abbreviated as St And in post-nominals) is a public university in St Andrews, Scotland. It is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, oldest of the four ancient universities of Scotland and, f ...

or possibly at the University of Glasgow

The University of Glasgow (abbreviated as ''Glas.'' in Post-nominal letters, post-nominals; ) is a Public university, public research university in Glasgow, Scotland. Founded by papal bull in , it is the List of oldest universities in continuous ...

. He studied under John Major

Sir John Major (born 29 March 1943) is a British retired politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from 1990 to 1997. Following his defeat to Ton ...

, one of the greatest scholars of the time. Knox was ordained a Catholic priest in Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. The city is located in southeast Scotland and is bounded to the north by the Firth of Forth and to the south by the Pentland Hills. Edinburgh ...

on Easter Eve of 1536 by William Chisholm William Chisholm may refer to:

*William Chisholm (I) (died 1564), bishop of Dunblane

*William Chisholm (II) (died 1593), bishop of Dunblane and of Vaison, and nephew of William (I)

*William Chisholm (Nova Scotia politician) (1870–1936), Canadian p ...

, Bishop of Dunblane

The Bishop of Dunblane or Bishop of Strathearn was the ecclesiastical head of the Diocese of Dunblane or Strathearn, one of medieval Scotland's thirteen bishoprics. It was based at Dunblane Cathedral, now a parish church of the Church of Scotlan ...

.

Knox first appears in public records as a priest and a notary

A notary is a person authorised to perform acts in legal affairs, in particular witnessing signatures on documents. The form that the notarial profession takes varies with local legal systems.

A notary, while a legal professional, is distin ...

in 1540. He was still serving in these capacities as late as 1543 when he described himself as a "minister of the sacred altar in the diocese of St Andrews, notary by apostolic authority" in a notarial deed dated 27 March. Rather than taking up parochial duties in a parish, he became tutor

Tutoring is private academic help, usually provided by an expert teacher; someone with deep knowledge or defined expertise in a particular subject or set of subjects.

A tutor, formally also called an academic tutor, is a person who provides assis ...

to two sons of Hugh Douglas of Longniddry

Longniddry (, )

is a coastal village in East Lothian ...

. He also taught the son of is a coastal village in East Lothian ...

John Cockburn of Ormiston

John Cockburn, (d. 1583) laird of Ormiston, East Lothian, Scotland, was an early supporter of the Scottish Reformation. He was the eldest son of William Cockburn of Ormiston and Janet Somerville. John was usually called "Ormiston." During his li ...

. Both of these laird

Laird () is a Scottish word for minor lord (or landlord) and is a designation that applies to an owner of a large, long-established Scotland, Scottish estate. In the traditional Scottish order of precedence, a laird ranked below a Baronage of ...

s had embraced the new religious ideas of the Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major Theology, theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the p ...

.

Embracing the Protestant Reformation, 1546–1547

Knox did not record when or how he was converted to the Protestant faith, but perhaps the key formative influences on Knox were Patrick Hamilton andGeorge Wishart

George Wishart (also Wisehart; c. 15131 March 1546) was a Scottish Protestant Reformer and one of the early Protestant martyrs burned at the stake as a heretic.

George Wishart was the son of James and brother of Sir John of Pitarrow ...

. Wishart was a reformer who had fled Scotland in 1538 to escape punishment for heresy. He first moved to England, where in Bristol

Bristol () is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city, unitary authority area and ceremonial county in South West England, the most populous city in the region. Built around the River Avon, Bristol, River Avon, it is bordered by t ...

he preached against the veneration

Veneration (; ), or veneration of saints, is the act of honoring a saint, a person who has been identified as having a high degree of sanctity or holiness. Angels are shown similar veneration in many religions. Veneration of saints is practiced, ...

of the Virgin Mary

Mary was a first-century Jewish woman of Nazareth, the wife of Saint Joseph, Joseph and the mother of Jesus. She is an important figure of Christianity, venerated under titles of Mary, mother of Jesus, various titles such as Perpetual virginity ...

. He was forced to make a public recantation and was burned in effigy

An effigy is a sculptural representation, often life-size, of a specific person or a prototypical figure. The term is mostly used for the makeshift dummies used for symbolic punishment in political protests and for the figures burned in certain ...

at the Church of St Nicholas as a sign of his abjuration. He then took refuge in Germany and Switzerland. While on the Continent

A continent is any of several large geographical regions. Continents are generally identified by convention (norm), convention rather than any strict criteria. A continent could be a single large landmass, a part of a very large landmass, as ...

, he translated the First Helvetic Confession

The Helvetic Confessions are two documents expressing the common belief of Reformed churches, especially in Switzerland, whose primary author was the Swiss Reformed theologian Heinrich Bullinger. The First Helvetic Confession (1536) contributed ...

into English. He returned to Scotland in 1544, but the timing of his return was unfortunate. In December 1543, James Hamilton, Duke of Châtellerault

James Hamilton, 1st Duke of Châtellerault, 2nd Earl of Arran ( – 22 January 1575), was a Scottish nobleman and Regent of Scotland during the minority of Mary, Queen of Scots from 1543 to 1554. At first pro- English and Protestant, he conv ...

, the appointed regent for the infant Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was List of Scottish monarchs, Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legit ...

, had decided with the Queen Mother, Mary of Guise

Mary of Guise (; 22 November 1515 – 11 June 1560), also called Mary of Lorraine, was List of Scottish royal consorts, Queen of Scotland from 1538 until 1542, as the second wife of King James V. She was a French people, French noblewoman of the ...

, and Cardinal

Cardinal or The Cardinal most commonly refers to

* Cardinalidae, a family of North and South American birds

**''Cardinalis'', genus of three species in the family Cardinalidae

***Northern cardinal, ''Cardinalis cardinalis'', the common cardinal of ...

David Beaton

David Beaton (also Beton or Bethune; 29 May 1546) was Archbishop of St Andrews and the last Scottish cardinal prior to the Reformation.

Life

David Beaton was said to be the fifth son of fourteen children born to John Beaton (Bethune) of Balf ...

to persecute the Protestant sect that had taken root in Scotland. Wishart travelled throughout Scotland preaching in favour of the Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major Theology, theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the p ...

, and when he arrived in East Lothian

East Lothian (; ; ) is one of the 32 council areas of Scotland, as well as a Counties of Scotland, historic county, registration county and Lieutenancy areas of Scotland, lieutenancy area. The county was called Haddingtonshire until 1921.

In ...

, Knox became one of his closest associates. Knox acted as his bodyguard, bearing a two-handed sword in order to defend him. In December 1545, Wishart was seized on Beaton's orders by the Earl of Bothwell

Earl of Bothwell was a title that was created twice in the Peerage of Scotland. It was first created for Patrick Hepburn in 1488, and was forfeited in 1567. Subsequently, the earldom was recreated for the 4th Earl's nephew and heir of line, F ...

and taken to the Castle of St Andrews. Knox was present on the night of Wishart's arrest and was prepared to follow him into captivity, but Wishart persuaded him against this course saying, "Nay, return to your bairn

''Bairn'' is a Northern England English, Scottish English and Scots term for a child. It originated in Old English as "", becoming restricted to Scotland and the North of England . In Hull the ''r'' is dropped and the word ''Bain'' is used.

...

s hildrenand God bless you. One is sufficient for a sacrifice." Wishart was subsequently prosecuted by Beaton's Public Accuser of Heretics, Archdeacon

An archdeacon is a senior clergy position in the Church of the East, Chaldean Catholic Church, Syriac Orthodox Church, Anglican Communion, St Thomas Christians, Eastern Orthodox Church, Eastern Orthodox churches and some other Christian denomina ...

John Lauder. On 1 March 1546, he was burnt at the stake in the presence of Beaton.

Knox had avoided being arrested by Lord Bothwell through Wishart's advice to return to tutoring. He took shelter with Douglas in Longniddry

Longniddry (, )

is a coastal village in East Lothian ...

. Several months later he was still in charge of the pupils, the sons of Douglas and Cockburn, who wearied of moving from place to place while being pursued. He toyed with the idea of fleeing to Germany and taking his pupils with him. While Knox remained a fugitive, Beaton was murdered on 29 May 1546, within his residence, the Castle of St Andrews, by a gang of five persons in revenge for Wishart's execution. The assassins seized the castle and eventually their families and friends took refuge with them, about a hundred and fifty men in all. Among their friends was is a coastal village in East Lothian ...

Henry Balnaves

Henry Balnaves (1512? – February 1570) was a Scottish politician, Lord Justice Clerk, and religious reformer.

Biography

Born in Kirkcaldy, Fife, around 1512, he was educated at the University of St Andrews and on the continent, where he adopte ...

, a former secretary of state in the government, who negotiated with England for the financial support of the rebels. Douglas and Cockburn suggested to Knox to take their sons to the relative safety of the castle to continue their instruction in reformed doctrine, and Knox arrived at the castle on 10 April 1547.

Knox's powers as a preacher came to the attention of the chaplain of the garrison, John Rough. While Rough was preaching in the parish church

A parish church (or parochial church) in Christianity is the Church (building), church which acts as the religious centre of a parish. In many parts of the world, especially in rural areas, the parish church may play a significant role in com ...

on the Protestant principle of the popular election of a pastor, he proposed Knox to the congregation for that office. Knox did not relish the idea. According to his own account, he burst into tears and fled to his room. Within a week, however, he was giving his first sermon to a congregation that included his old teacher, John Major

Sir John Major (born 29 March 1943) is a British retired politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of the Conservative Party from 1990 to 1997. Following his defeat to Ton ...

. He expounded on the seventh chapter of the Book of Daniel

The Book of Daniel is a 2nd-century BC biblical apocalypse with a 6th-century BC setting. It is ostensibly a narrative detailing the experiences and Prophecy, prophetic visions of Daniel, a Jewish Babylonian captivity, exile in Babylon ...

, comparing the Pope

The pope is the bishop of Rome and the Head of the Church#Catholic Church, visible head of the worldwide Catholic Church. He is also known as the supreme pontiff, Roman pontiff, or sovereign pontiff. From the 8th century until 1870, the po ...

with the Antichrist

In Christian eschatology, Antichrist (or in broader eschatology, Anti-Messiah) refers to a kind of entity prophesied by the Bible to oppose Jesus in Christianity, Jesus Christ and falsely substitute themselves as a savior in Christ's place before ...

. His sermon was marked by his consideration of the Bible

The Bible is a collection of religious texts that are central to Christianity and Judaism, and esteemed in other Abrahamic religions such as Islam. The Bible is an anthology (a compilation of texts of a variety of forms) originally writt ...

as his sole authority and the doctrine of justification by faith alone, two elements that would remain in his thoughts throughout the rest of his life. A few days later, a debate was staged that allowed him to lay down additional theses including the rejection of the Mass

Mass is an Intrinsic and extrinsic properties, intrinsic property of a physical body, body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the physical quantity, quantity of matter in a body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physi ...

, Purgatory

In Christianity, Purgatory (, borrowed into English language, English via Anglo-Norman language, Anglo-Norman and Old French) is a passing Intermediate state (Christianity), intermediate state after physical death for purifying or purging a soul ...

, and prayers for the dead

Religions with the belief in a final judgment, a resurrection of the dead or an intermediate state (such as Hades or purgatory) often offer prayers on behalf of the dead to God.

Buddhism

For most funerals that follow the tradition of Chinese Budd ...

.

Confinement in the French galleys, 1547–1549

John Knox's chaplaincy of the castle garrison was not to last long. While Hamilton was willing to negotiate with England to stop their support of the rebels and bring the castle back under his control, Mary of Guise decided that it could be taken only by force and requested the king of France,Henry II

Henry II may refer to:

Kings

* Saint Henry II, Holy Roman Emperor (972–1024), crowned King of Germany in 1002, of Italy in 1004 and Emperor in 1014

*Henry II of England (1133–89), reigned from 1154

*Henry II of Jerusalem and Cyprus (1271–1 ...

to intervene. On 29 June 1547, 21 French galley

A galley is a type of ship optimised for propulsion by oars. Galleys were historically used for naval warfare, warfare, Maritime transport, trade, and piracy mostly in the seas surrounding Europe. It developed in the Mediterranean world during ...

s approached St Andrews under the command of Leone Strozzi

Leone Strozzi (15 October 1515 – 28 June 1554) was an Italian condottiero belonging to the famous Strozzi family of Florence.

Biography

He was the son of Filippo Strozzi the Younger and Clarice de' Medici, and brother to Piero, Roberto and L ...

, prior

The term prior may refer to:

* Prior (ecclesiastical), the head of a priory (monastery)

* Prior convictions, the life history and previous convictions of a suspect or defendant in a criminal case

* Prior probability, in Bayesian statistics

* Prio ...

of Capua

Capua ( ; ) is a city and ''comune'' in the province of Caserta, in the region of Campania, southern Italy, located on the northeastern edge of the Campanian plain.

History Ancient era

The name of Capua comes from the Etruscan ''Capeva''. The ...

. The French besieged the castle and forced the surrender of the garrison on 31 July. The Protestant nobles and others, including Knox, were taken prisoner and forced to row in the French galleys. The galley slaves

A galley slave was a slave rowing in a galley, either a convicted criminal sentenced to work at the oar (''French'': galérien), or a kind of human chattel, sometimes a prisoner of war, assigned to the duty of rowing.

In the ancient Mediterran ...

were chained to benches and rowed throughout the day without a change of posture while an officer watched over them with a whip in hand. They sailed to France and navigated up the Seine

The Seine ( , ) is a river in northern France. Its drainage basin is in the Paris Basin (a geological relative lowland) covering most of northern France. It rises at Source-Seine, northwest of Dijon in northeastern France in the Langres plat ...

to Rouen

Rouen (, ; or ) is a city on the River Seine, in northwestern France. It is in the prefecture of Regions of France, region of Normandy (administrative region), Normandy and the Departments of France, department of Seine-Maritime. Formerly one ...

. The nobles, some of whom would have a bearing on Knox's later life such as William Kirkcaldy and Henry Balnaves, were sent to various castle-prisons in France. Knox and the other galley slaves continued to Nantes

Nantes (, ; ; or ; ) is a city in the Loire-Atlantique department of France on the Loire, from the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic coast. The city is the List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, sixth largest in France, with a pop ...

and stayed on the Loire

The Loire ( , , ; ; ; ; ) is the longest river in France and the 171st longest in the world. With a length of , it drains , more than a fifth of France's land, while its average discharge is only half that of the Rhône.

It rises in the so ...

throughout the winter. They were threatened with torture if they did not give proper signs of reverence when mass was performed on the ship. Knox recounted an incident in which one of the prisoners—possibly himself, as Knox tended to narrate personal anecdotes in the third person—was required to show devotion to a picture of the Virgin Mary. The prisoner was told to give it a kiss of veneration

Veneration (; ), or veneration of saints, is the act of honoring a saint, a person who has been identified as having a high degree of sanctity or holiness. Angels are shown similar veneration in many religions. Veneration of saints is practiced, ...

. He refused and when the picture was pushed up to his face, the prisoner seized the picture and threw it into the sea, saying, "Let our Lady now save herself: she is light enough: let her learn to swim." After that, according to Knox, the Scottish prisoners were no longer forced to perform such devotions.

In mid-1548, the galleys returned to Scotland to scout for English ships. Knox's health was now at its lowest point due to the severity of his confinement. He was ill with a fever and others on the ship were afraid for his life. Even in this state, Knox recalled, his mind remained sharp and he comforted his fellow prisoners with hopes of release. While the ships were lying offshore between St Andrews and Dundee

Dundee (; ; or , ) is the List of towns and cities in Scotland by population, fourth-largest city in Scotland. The mid-year population estimate for the locality was . It lies within the eastern central Lowlands on the north bank of the Firt ...

, the spires of the parish church where he preached appeared in view. James Balfour, a fellow prisoner, asked Knox whether he recognised the landmark. He replied that he knew it well, recognising the steeple of the place where he first preached and he declared that he would not die until he had preached there again.

In February 1549, after spending a total of 19 months in the galley-prison, Knox was released. It is uncertain how he obtained his liberty. Later in the year, Henry II arranged with Edward VI of England

Edward VI (12 October 1537 – 6 July 1553) was King of England and King of Ireland, Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death in 1553. He was crowned on 20 February 1547 at the age of nine. The only surviving son of Henry VIII by his thi ...

the release of all remaining Castilian prisoners.

Exile in England, 1549–1554

On his release, Knox took refuge in England. TheReformation in England

The English Reformation began in 16th-century England when the Church of England broke away first from the authority of the pope and bishops over the King and then from some doctrines and practices of the Catholic Church. These events we ...

was a less radical movement than its Continental counterparts, but there was a definite breach with Rome. The Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the Primus inter pares, ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the bishop of the diocese of Canterbury. The first archbishop ...

, Thomas Cranmer

Thomas Cranmer (2 July 1489 – 21 March 1556) was a theologian, leader of the English Reformation and Archbishop of Canterbury during the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI and, for a short time, Mary I. He is honoured as a Oxford Martyrs, martyr ...

, and the regent of King Edward VI

Edward VI (12 October 1537 – 6 July 1553) was King of England and King of Ireland, Ireland from 28 January 1547 until his death in 1553. He was crowned on 20 February 1547 at the age of nine. The only surviving son of Henry VIII by his thi ...

, the Duke of Somerset

Duke of Somerset, from the county of Somerset, is a title that has been created five times in the peerage of England. It is particularly associated with two families: the Beauforts, who held the title from the creation of 1448, and the Seymours ...

, were decidedly Protestant-minded. However, much work remained to bring reformed ideas to the clergy and to the people. On 7 April 1549, Knox was licensed to work in the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

. His first commission was in Berwick-upon-Tweed

Berwick-upon-Tweed (), sometimes known as Berwick-on-Tweed or simply Berwick, is a town and civil parish in Northumberland, England, south of the Anglo-Scottish border, and the northernmost town in England. The 2011 United Kingdom census recor ...

. He was obliged to use the recently released 1549 ''Book of Common Prayer'', which maintained the structure of the Sarum Rite

The Use of Sarum (or Use of Salisbury, also known as the Sarum Rite) is the Use (liturgy), liturgical use of the Latin liturgical rites, Latin rites developed at Salisbury Cathedral and used from the late eleventh century until the English Refor ...

while adapting the content to the doctrine of the reformed Church of England. Knox, however, modified its use to accord with the doctrinal emphases of the Continental reformers. In the pulpit, he preached Protestant doctrines with great effect as his congregation grew. In England, Knox met his wife, Margery Bowes (died ). Her father, Richard Bowes (died 1558), was a descendant of an old

In England, Knox met his wife, Margery Bowes (died ). Her father, Richard Bowes (died 1558), was a descendant of an old Durham Durham most commonly refers to:

*Durham, England, a cathedral city in north east England

**County Durham, a ceremonial county which includes Durham

*Durham, North Carolina, a city in North Carolina, United States

Durham may also refer to:

Places

...

family and her mother, Elizabeth Aske, was an heiress of a Yorkshire

Yorkshire ( ) is an area of Northern England which was History of Yorkshire, historically a county. Despite no longer being used for administration, Yorkshire retains a strong regional identity. The county was named after its county town, the ...

family, the Askes of Richmondshire

{{Infobox settlement

, name = Richmondshire District

, type = Non-metropolitan district

, image_skyline =

, imagesize =

, image_caption =

, image_blank_emblem= Richmondshire arms.png

, blank_em ...

. Elizabeth presumably met Knox when he was employed in Berwick. Several letters reveal a close friendship between them. It is not recorded when Knox married Margery Bowes. Knox attempted to obtain the consent of the Bowes family, but her father and her brother Robert Bowes were opposed to the marriage.

Towards the end of 1550, Knox was appointed a preacher of St Nicholas' Church in Newcastle upon Tyne

Newcastle upon Tyne, or simply Newcastle ( , Received Pronunciation, RP: ), is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England. It is England's northernmost metropolitan borough, located o ...

. The following year he was appointed one of the six royal chaplains serving the King. On 16 October 1551, John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland

John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland (1504Loades 2008 – 22 August 1553) was an English general, admiral, and politician, who led the government of the young King Edward VI from 1550 until 1553, and unsuccessfully tried to install Lady Jane ...

, overthrew the Duke of Somerset to become the new regent of the young King. Knox condemned the ''coup d'état'' in a sermon on All Saints Day

All Saints' Day, also known as All Hallows' Day, the Feast of All Saints, the Feast of All Hallows, the Solemnity of All Saints, and Hallowmas, is a Christianity, Christian solemnity celebrated in honour of all the saints of the Church, whether ...

. When Dudley visited Newcastle and listened to his preaching in June 1552, he had mixed feelings about the firebrand preacher, but he saw Knox as a potential asset. Knox was asked to come to London to preach before the Court. In his first sermon, he advocated a change for the 1552 ''Book of Common Prayer''. The liturgy required worshippers to kneel during communion. Knox and the other chaplains considered this to be idolatry

Idolatry is the worship of an idol as though it were a deity. In Abrahamic religions (namely Judaism, Samaritanism, Christianity, Islam, and the Baháʼí Faith) idolatry connotes the worship of something or someone other than the Abrahamic ...

. It triggered a debate where Archbishop Cranmer was called upon to defend the practice. The result was a compromise in which the famous Black Rubric

The term Black Rubric is the popular name for the declaration found at the end of the "Order for the Administration of the Lord's Supper" in the ''Book of Common Prayer'' (BCP), the Church of England's liturgical book. The Black Rubric explains wh ...

, which declared that no adoration is intended while kneeling, was included in the second edition.

Soon afterwards, Dudley, who saw Knox as a useful political tool, offered him the bishopric

In church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided provinces were administratively associate ...

of Rochester. Knox refused, and he returned to Newcastle. On 2 February 1553 Cranmer was ordered to appoint Knox as vicar of All Hallows, Bread Street

All Hallows Bread Street was a parish church in the Bread Street ward of the City of London, England. It stood on the east side of Bread Street, on the corner with Watling Street. First mentioned in the 13th century, the church was destroyed in ...

, in London, placing him under the authority of the Bishop of London

The bishop of London is the Ordinary (church officer), ordinary of the Church of England's Diocese of London in the Province of Canterbury. By custom the Bishop is also Dean of the Chapel Royal since 1723.

The diocese covers of 17 boroughs o ...

, Nicholas Ridley. Knox returned to London in order to deliver a sermon before the King and the Court during Lent and he again refused to take the assigned post. Knox was then told to preach in Buckinghamshire

Buckinghamshire (, abbreviated ''Bucks'') is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England and one of the home counties. It is bordered by Northamptonshire to the north, Bedfordshire to the north-east, Hertfordshir ...

and he remained there until Edward's death on 6 July. Edward's successor, Mary Tudor, re-established Roman Catholicism in England and restored the Mass

Mass is an Intrinsic and extrinsic properties, intrinsic property of a physical body, body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the physical quantity, quantity of matter in a body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physi ...

in all the churches. With the country no longer safe for Protestant preachers, Knox left for the Continent in January 1554 on the advice of friends. On the eve of his flight, he wrote:

Sometime I have thought that impossible it had been, so to have removed my affection from the realm of Scotland, that any realm or nation could have been equal dear to me. But God I take to record in my conscience, that the troubles present (and appearing to be) in the realm of England are double more dolorous unto my heart than ever were the troubles of Scotland.

From Geneva to Frankfurt and Scotland, 1554–1556

Knox disembarked inDieppe

Dieppe (; ; or Old Norse ) is a coastal commune in the Seine-Maritime department, Normandy, northern France.

Dieppe is a seaport on the English Channel at the mouth of the river Arques. A regular ferry service runs to Newhaven in England ...

, France, and continued to Geneva

Geneva ( , ; ) ; ; . is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland and the most populous in French-speaking Romandy. Situated in the southwest of the country, where the Rhône exits Lake Geneva, it is the ca ...

, where John Calvin

John Calvin (; ; ; 10 July 150927 May 1564) was a French Christian theology, theologian, pastor and Protestant Reformers, reformer in Geneva during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system of C ...

had established his authority. When Knox arrived Calvin was in a difficult position. He had recently overseen the Company of Pastors, which prosecuted charges of heresy against the scholar Michael Servetus

Michael Servetus (; ; ; also known as ''Michel Servetus'', ''Miguel de Villanueva'', ''Revés'', or ''Michel de Villeneuve''; 29 September 1509 or 1511 – 27 October 1553) was a Spanish theologian, physician, cartographer, and Renaissance ...

, although Calvin himself was not capable of voting for or against a civil penalty against Servetus. Knox asked Calvin four difficult political questions: whether a minor could rule by divine right, whether a female could rule and transfer sovereignty to her husband, whether people should obey ungodly or idolatrous rulers, and what party godly persons should follow if they resisted an idolatrous ruler. Calvin gave cautious replies and referred him to the Swiss reformer Heinrich Bullinger

Heinrich Bullinger (18 July 1504 – 17 September 1575) was a Swiss Reformer and theologian, the successor of Huldrych Zwingli as head of the Church of Zürich and a pastor at the Grossmünster. One of the most important leaders of the Swiss Re ...

in Zurich

Zurich (; ) is the list of cities in Switzerland, largest city in Switzerland and the capital of the canton of Zurich. It is in north-central Switzerland, at the northwestern tip of Lake Zurich. , the municipality had 448,664 inhabitants. The ...

. Bullinger's responses were equally cautious, but Knox had already made up his mind. On 20 July 1554, he published a pamphlet attacking Mary Tudor and the bishops who had brought her to the throne. He also attacked the Holy Roman Emperor

The Holy Roman Emperor, originally and officially the Emperor of the Romans (disambiguation), Emperor of the Romans (; ) during the Middle Ages, and also known as the Roman-German Emperor since the early modern period (; ), was the ruler and h ...

, Charles V Charles V may refer to:

Kings and Emperors

* Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor (1500–1558)

* Charles V of Naples (1661–1700), better known as Charles II of Spain

* Charles V of France (1338–1380), called the Wise

Others

* Charles V, Duke ...

, calling him "no less enemy to Christ than was Nero".

In a letter dated 24 September 1554, Knox received an invitation from a congregation of English exiles

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Culture, language and peoples

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

* ''English'', an Amish ter ...

in Frankfurt

Frankfurt am Main () is the most populous city in the States of Germany, German state of Hesse. Its 773,068 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the List of cities in Germany by population, fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located in the forela ...

to become one of their ministers. He accepted the call with Calvin's blessing. But no sooner had he arrived than he found himself in a conflict. The first set of refugees to arrive in Frankfurt had subscribed to a reformed liturgy and used a modified version of the ''Book of Common Prayer''. More recently arrived refugees, however, including Edmund Grindal

Edmund Grindal ( 15196 July 1583) was Bishop of London, Archbishop of York, and Archbishop of Canterbury during the reign of Elizabeth I. Though born far from the centres of political and religious power, he had risen rapidly in the church durin ...

, the future Archbishop of Canterbury, favoured a stricter application of the book. When Knox and a supporting colleague, William Whittingham

William Whittingham (c. 1524–1579) was an English Puritan, a Marian exile, and a translator of the Geneva Bible. He was well connected to the circles around John Knox, Heinrich Bullinger and John Calvin, and firmly resisted the continuance o ...

, wrote to Calvin for advice, they were told to avoid contention. Knox therefore agreed on a temporary order of service based on a compromise between the two sides. This delicate balance was disturbed when a new batch of refugees arrived that included Richard Cox, one of the principal authors of the ''Book of Common Prayer''. Cox brought Knox's pamphlet attacking the emperor to the attention of the Frankfurt authorities, who advised that Knox leave. His departure from Frankfurt on 26 March 1555 marked his final breach with the Church of England.

After his return to Geneva, Knox was chosen to be the minister at a new place of worship petitioned from Calvin. As such, he exerted an influence on French Protestants, whether they were exiled in Geneva or in France. In the meantime, Elizabeth Bowes wrote to Knox, asking him to return to Margery in Scotland, which he did at the end of August. Despite initial doubts about the state of the Reformation in Scotland, Knox found the country significantly changed since he was carried off in the galley in 1547. When he toured various parts of Scotland preaching the reformed doctrines and liturgy, he was welcomed by many of the nobility including two future regents of Scotland, the Earl of Moray

The title Earl of Moray, or Mormaer of Moray (pronounced "Murry"), was originally held by the rulers of the Province of Moray, which existed from the 10th century with varying degrees of independence from the Kingdom of Alba to the south. Until ...

and the Earl of Mar

There are currently two earldoms of Mar in the Peerage of Scotland, and the title has been created seven times. The first creation of the earldom is currently held by Margaret of Mar, 31st Countess of Mar, who is also clan chief of Clan Mar. Th ...

.

Though the Queen Regent, Mary of Guise

Mary of Guise (; 22 November 1515 – 11 June 1560), also called Mary of Lorraine, was List of Scottish royal consorts, Queen of Scotland from 1538 until 1542, as the second wife of King James V. She was a French people, French noblewoman of the ...

, made no move against Knox, his activities caused concern among the church authorities. The bishops of Scotland viewed him as a threat to their authority and summoned him to appear in Edinburgh

Edinburgh is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. The city is located in southeast Scotland and is bounded to the north by the Firth of Forth and to the south by the Pentland Hills. Edinburgh ...

on 15 May 1556. He was accompanied to the trial by so many influential persons that the bishops decided to call the hearing off. Knox was now free to preach openly in Edinburgh. William Keith, the Earl Marischal

The title of Earl Marischal was created in the Peerage of Scotland for William Keith, the Great Marischal of Scotland.

History

The office of Marischal of Scotland (or ''Marascallus Scotie'' or ''Marscallus Scotiae'') had been hereditary, held ...

, was impressed and urged Knox to write to the Queen Regent. Knox's unusually respectful letter urged her to support the Reformation and overthrow the church hierarchy. Queen Mary took the letter as a joke and ignored it.

Return to Geneva, 1556–1559

Shortly after Knox sent the letter to the Queen Regent, he suddenly announced that he felt his duty was to return to Geneva. In the previous year on 1 November 1555, the congregation in Geneva had elected Knox as their minister and he decided to take up the post. He wrote a final letter of advice to his supporters and left Scotland with his wife and mother-in-law. He arrived in Geneva on 13 September 1556. For the next two years, he lived a happy life in Geneva. He recommended Geneva to his friends in England as the best place of asylum for Protestants. In one letter he wrote:I neither fear nor eschame to say, is the most perfect school of Christ that ever was in the earth since the days of the apostles. In other places I confess Christ to be truly preached; but manners and religion so sincerely reformed, I have not yet seen in any other place ...Knox led a busy life in Geneva. He preached three sermons a week, each lasting well over two hours. The services used a liturgy that was derived by Knox and other ministers from Calvin's ''Formes des Prières Ecclésiastiques''. According to Laing, this order of service with some additions eventually became the ''

Book of Common Order

The ''Book of Common Order'', originally titled ''The Forme of Prayers'', is a liturgical book by John Knox written for use in the Calvinism, Reformed denomination. The text was composed in Geneva in 1556 and was adopted by the Church of Scotla ...

'' of the Kirk in 1565. The church in which Knox preached, the ''Église de Notre Dame la Neuve''—now known as the Auditoire de Calvin—had been granted by the municipal authorities, at Calvin's request, for the use of the English and Italian congregations. Knox's two sons, Nathaniel and Eleazar, were born in Geneva, with Whittingham and Myles Coverdale

Myles Coverdale, first name also spelt Miles ( – 20 January 1569), was an English ecclesiastical reformer chiefly known as a Bible translator, preacher, hymnist and, briefly, Bishop of Exeter (1551–1553). In 1535, Coverdale produced the fi ...

their respective godfathers.

In mid-1558, Knox published his best-known pamphlet, ''The first blast of the trumpet against the monstruous regiment of women

''The First Blast of the Trumpet Against the Monstruous Regiment of Women'' is a polemical work by the Scottish reformer John Knox, published in 1558. It attacks female monarchs, arguing that rule by women is contrary to the Bible.

Title

The ...

''. In calling the "regimen" or rule of women "monstruous", he meant that it was "unnatural". Knox states that his purpose was to demonstrate "how abominable before God is the Empire or Rule of a wicked woman, yea, of a traiteresse and bastard". The women rulers that Knox had in mind were Queen Mary I of England

Mary I (18 February 1516 – 17 November 1558), also known as Mary Tudor, was Queen of England and Ireland from July 1553 and Queen of Spain as the wife of King Philip II from January 1556 until her death in 1558. She made vigorous a ...

and Mary of Guise

Mary of Guise (; 22 November 1515 – 11 June 1560), also called Mary of Lorraine, was List of Scottish royal consorts, Queen of Scotland from 1538 until 1542, as the second wife of King James V. She was a French people, French noblewoman of the ...

, the Dowager Queen

A queen dowager or dowager queen (compare: princess dowager or dowager princess) is a title or status generally held by the widow of a king. In the case of the widow of an emperor, the title of empress dowager is used. Its full meaning is clear ...

of Scotland and regent on behalf of her daughter, Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was List of Scottish monarchs, Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legit ...

. This biblical position was not unusual in Knox's day; however, even he was aware that the pamphlet was dangerously seditious. He therefore published it anonymously and did not tell Calvin, who denied knowledge of it until a year after its publication, that he had written it. In England, the pamphlet was officially condemned by royal proclamation. The impact of the document was complicated later that year when Elizabeth Tudor

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last and longest reigning monarch of the House of Tudor. Her eventful reign, and its effect on history ...

, a Protestant, became Queen of England. Although Knox had not targeted Elizabeth, he had deeply offended her, and she never forgave him.

With a Protestant on the throne, the English refugees in Geneva prepared to return home. Knox himself decided to return to Scotland. Before his departure, various honours were conferred on him, including the freedom of the city of Geneva. Knox left in January 1559, but he did not arrive in Scotland until 2 May 1559, owing to Elizabeth's refusal to issue him a passport through England.

Revolution and end of the regency, 1559–1560

Two days after Knox arrived in Edinburgh, he proceeded toDundee

Dundee (; ; or , ) is the List of towns and cities in Scotland by population, fourth-largest city in Scotland. The mid-year population estimate for the locality was . It lies within the eastern central Lowlands on the north bank of the Firt ...

where a large number of Protestant sympathisers had gathered. Knox was declared an outlaw, and the Queen Regent

In a monarchy, a regent () is a person appointed to govern a state because the actual monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge their powers and duties, or the throne is vacant and a new monarch has not yet been dete ...

summoned the Protestants to Stirling

Stirling (; ; ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city in Central Belt, central Scotland, northeast of Glasgow and north-west of Edinburgh. The market town#Scotland, market town, surrounded by rich farmland, grew up connecting the roya ...

. Fearing the possibility of a summary trial and execution, the Protestants proceeded instead to Perth

Perth () is the list of Australian capital cities, capital city of Western Australia. It is the list of cities in Australia by population, fourth-most-populous city in Australia, with a population of over 2.3 million within Greater Perth . The ...

, a walled town that could be defended in case of a siege. At the church of St John the Baptist

John the Baptist ( – ) was a Jewish preacher active in the area of the Jordan River in the early first century AD. He is also known as Saint John the Forerunner in Eastern Orthodoxy and Oriental Orthodoxy, John the Immerser in some Baptist ...

, Knox preached a fiery sermon and a small incident precipitated into a riot. A mob poured into the church and it was soon gutted. The mob then attacked two friaries ( Blackfriars and Greyfriars) in the town, looting their gold and silver and smashing images. Mary of Guise gathered those nobles loyal to her and a small French army. She dispatched the Earl of Argyll

Earl () is a rank of the nobility in the United Kingdom. In modern Britain, an earl is a member of the peerage, ranking below a marquess and above a viscount. A feminine form of ''earl'' never developed; instead, ''countess'' is used.

The titl ...

and Lord Moray to offer terms and avert a war. She promised not to send any French troops into Perth if the Protestants evacuated the town. The Protestants agreed, but when the Queen Regent entered Perth, she garrisoned it with Scottish soldiers on the French payroll. This was seen as treacherous by Lord Argyll and Lord Moray, who both switched sides and joined Knox, who now based himself in St Andrews

St Andrews (; ; , pronounced ʰʲɪʎˈrˠiː.ɪɲ is a town on the east coast of Fife in Scotland, southeast of Dundee and northeast of Edinburgh. St Andrews had a recorded population of 16,800 , making it Fife's fourth-largest settleme ...

. Knox's return to St Andrews fulfilled the prophecy he made in the galleys that he would one day preach again in its church. When he did give a sermon, the effect was the same as in Perth. The people engaged in vandalism and looting. In June 1559, a Protestant mob incited by the preaching of John Knox ransacked the cathedral; the interior of the building was destroyed. The cathedral fell into decline following the attack and became a source of building material for the town. By 1561 it had been abandoned and left to fall into ruin.

With Protestant reinforcements arriving from neighbouring counties, the Queen Regent retreated to Dunbar

Dunbar () is a town on the North Sea coast in East Lothian in the south-east of Scotland, approximately east of Edinburgh and from the Anglo–Scottish border, English border north of Berwick-upon-Tweed.

Dunbar is a former royal burgh, and ...

. By now, the mob fury had spilled over central Scotland. Her own troops were on the verge of mutiny. On 30 June, the Protestant Lords of the Congregation

The Lords of the Congregation (), originally styling themselves the Faithful, were a group of Protestant Scottish nobles who in the mid-16th century favoured a reformation of the Catholic church according to Protestant principles and a Scottish ...

occupied Edinburgh, though they were able to hold it for only a month. But even before their arrival, the mob had already sacked the churches and the friaries. On 1 July, Knox preached from the pulpit of St Giles', the most influential in the capital. The Lords of the Congregation negotiated their withdrawal from Edinburgh by the Articles of Leith

The Articles of Leith were the terms of truce drawn up between the Protestant Lords of the Congregation and Mary of Guise, Regent of Scotland and signed on 25 July 1559. This negotiation was a step in the conflict that led to the Scottish Refor ...

signed 25 July 1559, and Mary of Guise promised freedom of conscience.

Knox knew that the Queen Regent would ask for help from France, so he negotiated by letter under the assumed name John Sinclair with William Cecil, Elizabeth's chief adviser, for English support. Knox sailed secretly to Lindisfarne

Lindisfarne, also known as Holy Island, is a tidal island off the northeast coast of England, which constitutes the civil parishes in England, civil parish of Holy Island in Northumberland. Holy Island has a recorded history from the 6th centu ...

, off the northeast coast of England at the end of July, to meet James Croft

Sir James Croft PC (c.1518 – 4 September 1590) was an English politician, who was Lord Deputy of Ireland, and MP for Herefordshire in the Parliament of England.

Life

He was born the second but eldest surviving son of Sir Richard Croft of Cro ...

and Sir Henry Percy at Berwick upon Tweed

Berwick-upon-Tweed (), sometimes known as Berwick-on-Tweed or simply Berwick, is a town and civil parish in Northumberland, England, south of the Anglo-Scottish border, and the northernmost town in England. The 2011 United Kingdom census recor ...

. Knox was indiscreet and news of his mission soon reached Mary of Guise. He returned to Edinburgh telling Croft he had to return to his flock, and suggested that Henry Balnaves

Henry Balnaves (1512? – February 1570) was a Scottish politician, Lord Justice Clerk, and religious reformer.

Biography

Born in Kirkcaldy, Fife, around 1512, he was educated at the University of St Andrews and on the continent, where he adopte ...

should go to Cecil.

When additional French troops arrived in Leith

Leith (; ) is a port area in the north of Edinburgh, Scotland, founded at the mouth of the Water of Leith and is home to the Port of Leith.

The earliest surviving historical references are in the royal charter authorising the construction of ...

, Edinburgh's seaport, the Protestants responded by retaking Edinburgh. This time, on 24 October 1559, the Scottish nobility formally deposed Mary of Guise from the regency. Her secretary, William Maitland of Lethington

William Maitland of Lethington (1525 – 9 June 1573) was a Scottish politician and reformer, and the eldest son of poet Richard Maitland.

Life

He was educated at the University of St Andrews.

William was the renowned "Secretary Lethington ...

, defected to the Protestant side, bringing his administrative skills. From then on, Maitland took over the political tasks, freeing Knox for the role of religious leader. For the final stage of the revolution, Maitland appealed to Scottish patriotism to fight French domination. Following the Treaty of Berwick, support from England finally arrived and by the end of March, a significant English army joined the Scottish Protestant forces. The sudden death of Mary of Guise in Edinburgh Castle

Edinburgh Castle is a historic castle in Edinburgh, Scotland. It stands on Castle Rock (Edinburgh), Castle Rock, which has been occupied by humans since at least the Iron Age. There has been a royal castle on the rock since the reign of Malcol ...

on 10 June 1560 paved the way for an end to hostilities, the signing of the Treaty of Edinburgh

The Treaty of Edinburgh (also known as the Treaty of Leith) was a treaty drawn up on 5 July 1560 between the Commissioners of Queen Elizabeth I of England with the assent of the Scottish Lords of the Congregation, and the French representatives o ...

, and the withdrawal of French and English troops from Scotland. On 19 July, Knox held a National Thanksgiving Service at St Giles'.

Reformation in Scotland, 1560–1561

On 1 August, theScottish Parliament

The Scottish Parliament ( ; ) is the Devolution in the United Kingdom, devolved, unicameral legislature of Scotland. It is located in the Holyrood, Edinburgh, Holyrood area of Edinburgh, and is frequently referred to by the metonym 'Holyrood'. ...

met to settle religious issues. Knox and five other ministers, all called John, were called upon to draw up a new confession of faith

A creed, also known as a confession of faith, a symbol, or a statement of faith, is a statement of the shared beliefs of a community (often a religious community) which summarizes its core tenets.

Many Christian denominations use three creeds: ...

. Within four days, the Scots Confession

The Scots Confession (also called the Scots Confession of 1560) is a Confession of Faith written in 1560 by six leaders of the Protestant Reformation in Scotland. The text of the Confession was the first subordinate standard for the Protestan ...

was presented to Parliament, voted upon, and approved. A week later, the Parliament passed three acts in one day: the first abolished the jurisdiction of the Pope in Scotland, the second condemned all doctrine and practice contrary to the reformed faith, and the third forbade the celebration of Mass in Scotland. Before the dissolution of Parliament, Knox and the other ministers were given the task of organising the newly reformed church or the Kirk

The Church of Scotland (CoS; ; ) is a Presbyterian denomination of Christianity that holds the status of the national church in Scotland. It is one of the country's largest, having 245,000 members in 2024 and 259,200 members in 2023. While mem ...

. They would work for several months on the ''Book of Discipline

A Book of Discipline (or in its shortened form Discipline) is a book detailing the beliefs, standards, doctrines, canon law, and polity of a particular Christian denomination. They are often re-written by the governing body of the church concern ...

'', the document describing the organisation of the new church. During this period, in December 1560, Knox's wife, Margery, died, leaving Knox to care for their two sons, aged three and a half and two years old. John Calvin, who had lost his own wife in 1549, wrote a letter of condolence.

Parliament reconvened on 15 January 1561 to consider the ''Book of Discipline''. The Kirk was to be run on democratic lines. Each congregation was free to choose or reject its own pastor, but once he was chosen he could not be fired. Each parish was to be self-supporting, as far as possible. The bishops were replaced by ten to twelve " superintendents". The plan included a system of national education based on universality as a fundamental principle. Certain areas of law were placed under ecclesiastical authority. The Parliament did not approve the plan, however, mainly for reasons of finance. The Kirk was to be financed out of the patrimony of the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland. Much of this was now in the hands of the nobles, who were reluctant to give up their possessions. A final decision on the plan was delayed because of the impending return of Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots (8 December 1542 – 8 February 1587), also known as Mary Stuart or Mary I of Scotland, was List of Scottish monarchs, Queen of Scotland from 14 December 1542 until her forced abdication in 1567.

The only surviving legit ...

.

Knox and Queen Mary, 1561–1564

On 19 August 1561, cannons were fired in Leith to announce Queen Mary's arrival in Scotland. When she attended Mass being celebrated in the royal chapel atHolyrood Palace

The Palace of Holyroodhouse ( or ), commonly known as Holyrood Palace, is the official residence of the British monarch in Scotland. Located at the bottom of the Royal Mile in Edinburgh, at the opposite end to Edinburgh Castle, Holyrood has s ...

five days later, this prompted a protest in which one of her servants was jostled. The next day she issued a proclamation that there would be no alteration in the current state of religion and that her servants should not be molested or troubled. Many nobles accepted this, but not Knox. The following Sunday, he protested from the pulpit of St Giles'. As a result, just two weeks after her return, Mary summoned Knox. She accused him of inciting a rebellion against her mother and of writing a book against her own authority. Knox answered that as long as her subjects found her rule convenient, he was willing to accept her governance, noting that Paul the Apostle

Paul, also named Saul of Tarsus, commonly known as Paul the Apostle and Saint Paul, was a Apostles in the New Testament, Christian apostle ( AD) who spread the Ministry of Jesus, teachings of Jesus in the Christianity in the 1st century, first ...

had been willing to live under Nero

Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus ( ; born Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus; 15 December AD 37 – 9 June AD 68) was a Roman emperor and the final emperor of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, reigning from AD 54 until his ...

's rule. Mary noted, however, that he had written against the principle of female rule itself. He responded that she should not be troubled by what had never harmed her. When Mary asked him whether subjects had a right to resist

The right to resist is a nearly universally acknowledged human right, although its scope and content are controversial. The right to resist, depending on how it is defined, can take the form of civil disobedience or armed resistance against a t ...

their ruler, he replied that if monarchs exceeded their lawful limits, they might be resisted, even by force.

On 13 December 1562, Mary sent for Knox again after he gave a sermon denouncing certain celebrations which Knox had interpreted as rejoicing at the expense of the Reformation. She charged that Knox spoke irreverently of the Queen in order to make her appear contemptible to her subjects. After Knox gave an explanation of the sermon, Mary stated that she did not blame Knox for the differences of opinion and asked that in the future he come to her directly if he heard anything about her that he disliked. Despite her gesture, Knox replied that he would continue to voice his convictions in his sermons and would not wait upon her.

During Easter in 1563, some priests in Ayrshire

Ayrshire (, ) is a Counties of Scotland, historic county and registration county, in south-west Scotland, located on the shores of the Firth of Clyde. The lieutenancy areas of Scotland, lieutenancy area of Ayrshire and Arran covers the entirety ...

celebrated Mass, thus defying the law. Some Protestants tried to enforce the law themselves by apprehending these priests. This prompted Mary to summon Knox for the third time. She asked Knox to use his influence to promote religious toleration. He defended their actions and noted she was bound to uphold the laws and if she did not, others would. Mary surprised Knox by agreeing that the priests would be brought to justice.

The most dramatic interview between Mary and Knox took place on 24 June 1563. Mary summoned Knox to Holyrood after hearing that he had been preaching against her proposed marriage to Don Carlos

''Don Carlos'' is an 1867 five-act grand opera composed by Giuseppe Verdi to a French-language libretto by Joseph Méry and Camille du Locle, based on the 1787 play '' Don Karlos, Infant von Spanien'' (''Don Carlos, Infante of Spain'') by Fried ...

, the son of Philip II of Spain

Philip II (21 May 152713 September 1598), sometimes known in Spain as Philip the Prudent (), was King of Spain from 1556, King of Portugal from 1580, and King of Naples and List of Sicilian monarchs, Sicily from 1554 until his death in 1598. He ...

. Mary began by scolding Knox, then she burst into tears. "What have ye to do with my marriage?" she asked, and "What are ye within this commonwealth?"; "A subject born within the same, Madam," Knox replied. He noted that though he was not of noble birth, he had the same duty as any subject to warn of dangers to the realm. When Mary started to cry again, he said, "Madam, in God's presence I speak: I never delighted in the weeping of any of God's creatures; yea I can scarcely well abide the tears of my own boys whom my own hand corrects, much less can I rejoice in your Majesty's weeping." He added that he would rather endure her tears, however, than remain silent and "betray my Commonwealth". At this, Mary ordered him out of the room.

Knox's final encounter with Mary was prompted by an incident at Holyrood. While Mary was absent from Edinburgh on her summer progress

Progress is movement towards a perceived refined, improved, or otherwise desired state. It is central to the philosophy of progressivism, which interprets progress as the set of advancements in technology, science, and social organization effic ...

in 1563, a crowd forced its way into her private chapel as Mass was being celebrated. During the altercation, the priest's life was threatened. As a result, two of the ringleaders, burgesses of Edinburgh, were scheduled for trial on 24 October 1563. In order to defend these men, Knox sent out letters calling the nobles to convene. Mary obtained one of these letters and asked her advisors if this was not a treasonable act. Stewart and Maitland, wanting to keep good relations with both the Kirk and the Queen, asked Knox to admit he was wrong and to settle the matter quietly. Knox refused and he defended himself in front of Mary and the Privy Council. He argued that he had called a legal, not an illegal, assembly as part of his duties as a minister of the Kirk. After he left, the councillors voted not to charge him with treason.

Final years in Edinburgh, 1564–1572

On 26 March 1564, Knox stirred controversy again when he married Margaret Stewart, the daughter of an old friend,Andrew Stewart, 2nd Lord Ochiltree

Andrew Stewart, 2nd Lord Ochiltree (c. 1521–1591) fought for the Scottish Reformation. His daughter married John Knox and he played a part in the defeat of Mary, Queen of Scots at the battle of Langside.

Biography

Andrew's father, Andrew Stewar ...

, a member of the Stuart family and a distant relative of the Queen, Mary Stuart. The marriage was unusual because he was a widower of fifty, while the bride was only seventeen. Very few details are known of their domestic life. They had three daughters, Martha, Margaret, and Elizabeth.

When the General Assembly convened in June 1564, an argument broke out between Knox and Maitland over the authority of the civil government. Maitland told Knox to refrain from stirring up emotions over Mary's insistence on having mass celebrated and he quoted from Martin Luther

Martin Luther ( ; ; 10 November 1483 – 18 February 1546) was a German priest, Theology, theologian, author, hymnwriter, professor, and former Order of Saint Augustine, Augustinian friar. Luther was the seminal figure of the Reformation, Pr ...

and John Calvin about obedience to earthly rulers. Knox retorted that the Bible notes that Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

was punished when it followed an unfaithful king and that the Continental reformers were refuting arguments made by the Anabaptists

Anabaptism (from Neo-Latin , from the Greek : 're-' and 'baptism'; , earlier also )Since the middle of the 20th century, the German-speaking world no longer uses the term (translation: "Re-baptizers"), considering it biased. The term (tra ...

who rejected all forms of government. The debate revealed his waning influence on political events as the nobility continued to support Mary.

After the wedding of Mary and Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley

Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley (1546 – 10 February 1567) was King of Scotland as the second husband of Mary, Queen of Scots, from 29 July 1565 until his murder in 1567. Lord Darnley had one child with Mary, the future James VI of Scotland and I ...

, on 29 July 1565, some of the Protestant nobles, including James Stewart, 1st Earl of Moray

James Stewart, 1st Earl of Moray (c. 1531 – 23 January 1570) was a member of the House of Stewart as the illegitimate son of King James V of Scotland. At times a supporter of his half-sister Mary, Queen of Scots, he was the regent of Scotl ...

, rose up in a rebellion known as the "Chaseabout Raid

The Chaseabout Raid was a rebellion by James Stewart, 1st Earl of Moray, against his half sister, Mary, Queen of Scots, on 26 August 1565, over her marriage to Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley. The rebels also claimed to be acting over other causes i ...

". Knox revealed his own objection to the marriage while preaching in the presence of the new King Consort