John Wilson (Puritan) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Wilson (c. 1588 – 1667) was a

Wilson was first formally educated at

Wilson was first formally educated at

Wilson was an early member of the

Wilson was an early member of the

When Wilson returned from his England trip in 1635, he was accompanied aboard the ship ''Abigail'' by two other people who would play a role in the religious controversy to come. One of these was the Reverend

When Wilson returned from his England trip in 1635, he was accompanied aboard the ship ''Abigail'' by two other people who would play a role in the religious controversy to come. One of these was the Reverend

In October 1636 the ministers, realizing that a theological tempest was forming in the colony, decided to get to the heart of the issue, and held a series of meetings, which also included Hutchinson and some of the magistrates. In order to deal with the theological errors of the Hutchinson group, the ministers first had to come to a consensus about their own positions, and this they were unable to do. Hutchinson's followers used this impasse to attempt to have Wheelwright appointed as another minister to the Boston church, an expression of their dissatisfaction with Wilson. Winthrop came to Wilson's rescue, as an elder in the church, by invoking a ruling requiring unanimity in a church vote, and was thus able to forestall Wheelwright's appointment there. Instead, Wheelwright was sent about ten miles south to

In October 1636 the ministers, realizing that a theological tempest was forming in the colony, decided to get to the heart of the issue, and held a series of meetings, which also included Hutchinson and some of the magistrates. In order to deal with the theological errors of the Hutchinson group, the ministers first had to come to a consensus about their own positions, and this they were unable to do. Hutchinson's followers used this impasse to attempt to have Wheelwright appointed as another minister to the Boston church, an expression of their dissatisfaction with Wilson. Winthrop came to Wilson's rescue, as an elder in the church, by invoking a ruling requiring unanimity in a church vote, and was thus able to forestall Wheelwright's appointment there. Instead, Wheelwright was sent about ten miles south to

In hopes of bringing the mounting crisis under control, the General Court called for a day of fasting and repentance to be held on Thursday, 19 January 1637. During the Boston church service held that day, Cotton invited Wheelwright to come forward and deliver a sermon. Instead of the hoped-for peace, the opposite transpired. In the sermon Wheelwright stated that those who taught a covenant of works were Antichrists, and all the ministers besides Cotton saw this as being directed at them, though Wheelwright later denied this. During a meeting of the General Court in March Wheelwright was questioned at length, and ultimately charged with sedition, though not sentenced.

In hopes of bringing the mounting crisis under control, the General Court called for a day of fasting and repentance to be held on Thursday, 19 January 1637. During the Boston church service held that day, Cotton invited Wheelwright to come forward and deliver a sermon. Instead of the hoped-for peace, the opposite transpired. In the sermon Wheelwright stated that those who taught a covenant of works were Antichrists, and all the ministers besides Cotton saw this as being directed at them, though Wheelwright later denied this. During a meeting of the General Court in March Wheelwright was questioned at length, and ultimately charged with sedition, though not sentenced.

By late 1637, the conclusion of the controversy was beginning to take shape. During the court held in early November, Wheelwright was finally sentenced to banishment, the delay caused by the hopes that he would, at some point, recant. On 7 November the trial of Anne Hutchinson began, and Wilson was there with most of the other ministers in the colony, though his role was somewhat restrained. During the second day of the trial, when things seemed to be going in her favor, Hutchinson insisted on making a statement, admitting that her knowledge of things had come from a divine inspiration, prophesying her deliverance from the proceedings, and announcing that a curse would befall the colony. This was all that her judges needed to hear, and she was accused of heresy and sentenced to banishment, though she would be held in detention for four months, awaiting a trial by the clergy. While no statements made by Wilson were recorded in either existing transcript of this trial, Wilson did make a speech against Hutchinson at the end of the proceedings, to which Hutchinson responded with anger four months later during her church trial.

Her church trial took place at the Boston meeting house on two consecutive Thursdays in March 1638. Hutchinson was accused of numerous theological errors of which only four were covered during the first day, so the trial was scheduled to continue the following week, when Wilson took an active part in the proceedings. During this second day of interrogation a week later, Hutchinson read a carefully written recantation of her theological errors. Had the trial ended there, she would have likely remained in communion with the church, with the possibility of even returning there some day. Wilson, however, did not accept this recantation, and he re-opened a line of questioning from the previous week. With this, a new onslaught began, and when later given the opportunity, Wilson said, " he root of.. your errors...is the slightinge of Gods faythfull Ministers and contenminge and cryinge down them as Nobodies."

By late 1637, the conclusion of the controversy was beginning to take shape. During the court held in early November, Wheelwright was finally sentenced to banishment, the delay caused by the hopes that he would, at some point, recant. On 7 November the trial of Anne Hutchinson began, and Wilson was there with most of the other ministers in the colony, though his role was somewhat restrained. During the second day of the trial, when things seemed to be going in her favor, Hutchinson insisted on making a statement, admitting that her knowledge of things had come from a divine inspiration, prophesying her deliverance from the proceedings, and announcing that a curse would befall the colony. This was all that her judges needed to hear, and she was accused of heresy and sentenced to banishment, though she would be held in detention for four months, awaiting a trial by the clergy. While no statements made by Wilson were recorded in either existing transcript of this trial, Wilson did make a speech against Hutchinson at the end of the proceedings, to which Hutchinson responded with anger four months later during her church trial.

Her church trial took place at the Boston meeting house on two consecutive Thursdays in March 1638. Hutchinson was accused of numerous theological errors of which only four were covered during the first day, so the trial was scheduled to continue the following week, when Wilson took an active part in the proceedings. During this second day of interrogation a week later, Hutchinson read a carefully written recantation of her theological errors. Had the trial ended there, she would have likely remained in communion with the church, with the possibility of even returning there some day. Wilson, however, did not accept this recantation, and he re-opened a line of questioning from the previous week. With this, a new onslaught began, and when later given the opportunity, Wilson said, " he root of.. your errors...is the slightinge of Gods faythfull Ministers and contenminge and cryinge down them as Nobodies."

In the 1650s Quaker missionaries began filtering into the Massachusetts Bay Colony, mostly from

In the 1650s Quaker missionaries began filtering into the Massachusetts Bay Colony, mostly from

Wilson's final years were marked by a prolonged illness. In his will, dated 31 May 1667, Wilson remembered a large number of people, among them being several of the local ministers, including

Wilson's final years were marked by a prolonged illness. In his will, dated 31 May 1667, Wilson remembered a large number of people, among them being several of the local ministers, including

Some of the works of Wilson

{{DEFAULTSORT:Wilson, John 1591 births 1667 deaths People educated at Eton College Alumni of Emmanuel College, Cambridge Alumni of King's College, Cambridge English emigrants to Massachusetts Bay Colony American religious writers 17th-century English Puritan ministers Clergy from colonial Massachusetts 17th-century New England Puritan ministers People from colonial Boston Burials at King's Chapel Burying Ground 17th-century writers in Latin American writers in Latin

Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to rid the Church of England of what they considered to be Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should b ...

clergyman in Boston

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

in the Massachusetts Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony (1628–1691), more formally the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, was an English settlement on the east coast of North America around Massachusetts Bay, one of the several colonies later reorganized as the Province of M ...

, and the minister of the First Church of Boston from its beginnings in Charlestown in 1630 until his death in 1667. He is most noted for being a minister at odds with Anne Hutchinson

Anne Hutchinson (; July 1591 – August 1643) was an English-born religious figure who was an important participant in the Antinomian Controversy which shook the infant Massachusetts Bay Colony from 1636 to 1638. Her strong religious formal d ...

during the Antinomian Controversy

The Antinomian Controversy, also known as the Free Grace Controversy, was a religious and political conflict in the Massachusetts Bay Colony from 1636 to 1638. It pitted most of the colony's ministers and magistrates against some adherents of ...

from 1636 to 1638, and for being an attending minister during the execution of Mary Dyer

Mary Dyer (born Marie Barrett; c. 1611 – 1 June 1660) was an English and colonial American Puritan-turned-Quaker who was hanged in Boston, Massachusetts Bay Colony, for repeatedly defying a Puritan law banning Quakers from the colony d ...

in 1660.

Born into a prominent English family from Sudbury Sudbury may refer to:

Places Australia

* Sudbury Reef, Queensland

Canada

* Greater Sudbury, Ontario

** Sudbury (federal electoral district)

** Sudbury (provincial electoral district)

** Sudbury Airport

** Sudbury Basin, a meteorite impact cra ...

in Suffolk

Suffolk ( ) is a ceremonial county in the East of England and East Anglia. It is bordered by Norfolk to the north, the North Sea to the east, Essex to the south, and Cambridgeshire to the west. Ipswich is the largest settlement and the county ...

, his father was the chaplain to the Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the Primus inter pares, ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the bishop of the diocese of Canterbury. The first archbishop ...

, and thus held a high position in the Anglican Church

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

. Young Wilson was sent to school at Eton

Eton most commonly refers to Eton College, a public school in Eton, Berkshire, England.

Eton may also refer to:

Places

*Eton, Berkshire, a town in Berkshire, England

*Eton, Georgia, a town in the United States

*Éton, a commune in the Meuse depa ...

for four years, and then attended the university at King's College, Cambridge

King's College, formally The King's College of Our Lady and Saint Nicholas in Cambridge, is a List of colleges of the University of Cambridge, constituent college of the University of Cambridge. The college lies beside the River Cam and faces ...

, where he received his B.A. in 1610. From there he studied law briefly, and then studied at Emmanuel College, Cambridge

Emmanuel College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. The college was founded in 1584 by Sir Walter Mildmay, Chancellor of the Exchequer to Elizabeth I. The site on which the college sits was once a priory for Dominican mo ...

, where he received an M.A. in 1613. Following his ordination, he was the chaplain for some prominent families for a few years, before being installed as pastor in his home town of Sudbury. Over the next ten years, he was dismissed and then reinstated on several occasions, because of his strong Puritan sentiments which contradicted the practices of the established church.

As with many other Puritan divines, Wilson came to New England, and sailed with his friend John Winthrop

John Winthrop (January 12, 1588 – March 26, 1649) was an English Puritan lawyer and a leading figure in the founding of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the second major settlement in New England following Plymouth Colony. Winthrop led the fir ...

and the Winthrop Fleet

The Winthrop Fleet was a group of 11 ships led by John Winthrop out of a total of 17funded by the Massachusetts Bay Company which together carried between 700 and 1,000 Puritans plus livestock and provisions from England to New England over th ...

in 1630. He was the first minister of the settlers, who established themselves in Charlestown, but soon crossed the Charles River

The Charles River (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ), sometimes called the River Charles or simply the Charles, is an river in eastern Massachusetts. It flows northeast from Hopkinton, Massachusetts, Hopkinton to Boston along a highly me ...

into Boston

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

. Wilson was an encouragement to the early settlers during the very trying initial years of colonization. He made two return trips to England during his early days in Boston, the first time to persuade his wife to come, after she initially refused to make the trip, and the second time to transact some business. Upon his second return to the Massachusetts Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony (1628–1691), more formally the Colony of Massachusetts Bay, was an English settlement on the east coast of North America around Massachusetts Bay, one of the several colonies later reorganized as the Province of M ...

in 1635, Anne Hutchinson

Anne Hutchinson (; July 1591 – August 1643) was an English-born religious figure who was an important participant in the Antinomian Controversy which shook the infant Massachusetts Bay Colony from 1636 to 1638. Her strong religious formal d ...

was first exposed to his preaching, and found an unhappy difference between his theology and that of her mentor, John Cotton, who was the other Boston minister. The theologically astute, sharp-minded, and outspoken Hutchinson, who had been hosting large groups of followers in her home, began to criticize Wilson, and the divide erupted into the Antinomian Controversy

The Antinomian Controversy, also known as the Free Grace Controversy, was a religious and political conflict in the Massachusetts Bay Colony from 1636 to 1638. It pitted most of the colony's ministers and magistrates against some adherents of ...

. Hutchinson was eventually tried and banished from the colony, as was her brother-in-law, Reverend John Wheelwright

John Wheelwright (c. 1592–1679) was a Puritan clergyman in England and America, noted for being banished from the Massachusetts Bay Colony during the Antinomian Controversy, and for subsequently establishing the town of Exeter, New Hamps ...

.

Following the controversy, Wilson and Cotton were able to work together to heal the divisions within the Boston church, but after Cotton's death, more controversy befell Boston as the Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to the Religious Society of Friends, a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations. Members refer to each other as Friends after in the Bible, and originally, others referred to them as Quakers ...

s began to infiltrate the orthodox colony with their evangelists. Greatly opposed to their theology, Wilson supported the actions taken against them, and supervised the execution of his former parishioner, Mary Dyer

Mary Dyer (born Marie Barrett; c. 1611 – 1 June 1660) was an English and colonial American Puritan-turned-Quaker who was hanged in Boston, Massachusetts Bay Colony, for repeatedly defying a Puritan law banning Quakers from the colony d ...

in 1660. He died in 1667.Early life

John Wilson was born inWindsor, Berkshire

Windsor is a historic town in the Royal Borough of Windsor and Maidenhead in Berkshire, England. It is the site of Windsor Castle, one of the official residences of the Monarchy of the United Kingdom, British monarch. The town is situated we ...

, England about 1588, the son of the Reverend William Wilson (1542–1615). John's father, originally of Sudbury Sudbury may refer to:

Places Australia

* Sudbury Reef, Queensland

Canada

* Greater Sudbury, Ontario

** Sudbury (federal electoral district)

** Sudbury (provincial electoral district)

** Sudbury Airport

** Sudbury Basin, a meteorite impact cra ...

in Suffolk

Suffolk ( ) is a ceremonial county in the East of England and East Anglia. It is bordered by Norfolk to the north, the North Sea to the east, Essex to the south, and Cambridgeshire to the west. Ipswich is the largest settlement and the county ...

, was a chaplain to the Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the Primus inter pares, ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the bishop of the diocese of Canterbury. The first archbishop ...

, Edmund Grindal

Edmund Grindal ( 15196 July 1583) was Bishop of London, Archbishop of York, and Archbishop of Canterbury during the reign of Elizabeth I. Though born far from the centres of political and religious power, he had risen rapidly in the church durin ...

. His father was also a prebend

A prebendary is a member of the Catholic or Anglican clergy, a form of canon with a role in the administration of a cathedral or collegiate church. When attending services, prebendaries sit in particular seats, usually at the back of the choir ...

of St Paul's

St Paul's Cathedral, formally the Cathedral Church of St Paul the Apostle, is an Anglican cathedral in London, England, the seat of the Bishop of London. The cathedral serves as the mother church of the Diocese of London in the Church of Engl ...

in London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

, a minister in Rochester, Kent

Rochester ( ) is a town in the unitary authority of Medway, in Kent, England. It is at the lowest bridging point of the River Medway, about east-southeast of London. The town forms a conurbation with neighbouring towns Chatham, Kent, Chatham, ...

, and a rector of the parish of Cliffe, Kent

Cliffe is a village and former civil parish, now in the parish of Cliffe and Cliffe Woods, in the borough of Medway in the ceremonial county of Kent, England. It is on the Hoo Peninsula, reached from the Medway Towns by a three-mile (4.8 ...

. Wilson's mother was Isabel Woodhull, the daughter of John Woodhull and Elizabeth Grindal, and a niece of Archbishop Grindal. According to Wilson's biographer, A. W. M'Clure, Archbishop Grindal favored the Puritans to the extent of his power, to the displeasure of Queen Elizabeth Queen Elizabeth, Queen Elisabeth or Elizabeth the Queen may refer to:

Queens regnant

* Elizabeth I (1533–1603; ), Queen of England and Ireland

* Elizabeth II (1926–2022; ), Queen of the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth realms

* Queen B ...

.

Wilson was first formally educated at

Wilson was first formally educated at Eton College

Eton College ( ) is a Public school (United Kingdom), public school providing boarding school, boarding education for boys aged 13–18, in the small town of Eton, Berkshire, Eton, in Berkshire, in the United Kingdom. It has educated Prime Mini ...

, where he spent four years, and at one time was chosen to speak a Latin oration during the visit of the duc de Biron, ambassador from the court of Henry IV of France

Henry IV (; 13 December 1553 – 14 May 1610), also known by the epithets Good King Henry (''le Bon Roi Henri'') or Henry the Great (''Henri le Grand''), was King of Navarre (as Henry III) from 1572 and King of France from 1589 to 16 ...

. The duke then gave him a special gift of a gold coin called "three angels", worth about ten shillings. On 23 August 1605, at the age of 14, Wilson was admitted to King's College, Cambridge

King's College, formally The King's College of Our Lady and Saint Nicholas in Cambridge, is a List of colleges of the University of Cambridge, constituent college of the University of Cambridge. The college lies beside the River Cam and faces ...

. While there he was initially prejudiced against the Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to rid the Church of England of what they considered to be Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should b ...

s, but changed his stance after reading Richard Rogers' ''Seven Treatises'' (1604), and he subsequently traveled to Dedham to hear Rogers preach. He and other like-minded students frequently met to discuss theology, and he also regularly visited prisons to minister to the inmates. He received his B.A. from King's College in 1609/10, then studied law for a year at the Inns of Court

The Inns of Court in London are the professional associations for barristers in England and Wales. There are four Inns of Court: Gray's Inn, Lincoln's Inn, Inner Temple, and Middle Temple.

All barristers must belong to one of them. They have s ...

in London

London is the Capital city, capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of both England and the United Kingdom, with a population of in . London metropolitan area, Its wider metropolitan area is the largest in Wester ...

. He next attended Emmanuel College, Cambridge

Emmanuel College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge. The college was founded in 1584 by Sir Walter Mildmay, Chancellor of the Exchequer to Elizabeth I. The site on which the college sits was once a priory for Dominican mo ...

, noted for its Puritan advocacy, where he received his M.A. in 1613. While at Emmanuel, he likely formed a friendship with future New England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

divines, John Cotton and Thomas Hooker

Thomas Hooker (July 5, 1586 – July 7, 1647) was a prominent English colonial leader and Congregational church, Congregational minister, who founded the Connecticut Colony after dissenting with Puritan leaders in Massachusetts. He was know ...

. He was probably soon ordained as a minister in the Anglican Church

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

, but records of this event are not extant.

In 1615 Wilson visited his dying father, who had these parting words for his son: "while thou wast at the university, because thou wouldst not conform, I fain would have brought thee to some higher preferment; but I see thy conscience is very scrupulous about somethings imposed in the church. Nevertheless, I have rejoiced to see the grace and fear of God in thy heart; and seeing thou hast hitherto maintained a good conscience, and walked according to thy light, do so still. Go by the rule of God's holy word, and the Lord bless thee."

Wilson preached for three years as the chaplain to several respectful families in Suffolk, one of them being the family of the Countess of Leicester. It was to her that he later dedicated his only book, ''Some Helps to Faith...'', published in 1630. In time he was offered, and accepted, the position of minister at Sudbury, from where his family had originated. While there he met John Winthrop

John Winthrop (January 12, 1588 – March 26, 1649) was an English Puritan lawyer and a leading figure in the founding of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the second major settlement in New England following Plymouth Colony. Winthrop led the fir ...

, and likely supported Winthrop's unsuccessful 1626 bid to become a member of Parliament. Wilson was suspended and then restored several times as minister, the issue being nonconformity (Puritan leanings) with the established practices of the Anglican Church. Like many Puritans, he began turning his thoughts toward New England.

Massachusetts

Wilson was an early member of the

Wilson was an early member of the Massachusetts Bay Company

Massachusetts ( ; ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is a state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode Island to it ...

, and accompanied John Winthrop and the Winthrop Fleet

The Winthrop Fleet was a group of 11 ships led by John Winthrop out of a total of 17funded by the Massachusetts Bay Company which together carried between 700 and 1,000 Puritans plus livestock and provisions from England to New England over th ...

to New England

New England is a region consisting of six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York (state), New York to the west and by the ...

in 1630. As soon as they arrived, he, with Governor Winthrop, Thomas Dudley

Thomas Dudley (12 October 157631 July 1653) was a New England colonial magistrate who served several terms as governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Dudley was the chief founder of Newtowne, later Cambridge, Massachusetts, and built the tow ...

, and Isaac Johnson, entered into a formal and solemn covenant with each other to walk together in the fellowship of the gospel. Life was harsh in the new wilderness, and Plymouth

Plymouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Devon, South West England. It is located on Devon's south coast between the rivers River Plym, Plym and River Tamar, Tamar, about southwest of Exeter and ...

historian Nathaniel Morton

Capt. Nathaniel Morton (christened 161629 June 1685) was a Separatist settler of Plymouth Colony in Massachusetts, where he served for most of his life as Plymouth's secretary under his uncle, Governor William Bradford. Morton wrote an account o ...

said that Wilson "bare a great share of the difficulties of these new beginnings with great cheerfulness and alacrity of spirit." Wilson was chosen the pastor of their first church in Charlestown, being installed as teacher there on 27 August 1630, and in the same month the General Court ordered that a dwelling-house should be built for him at the public expense, and the governor and Sir Richard Saltonstall

Sir Richard Saltonstall (baptised, 4 April 1586 – October 1661) led a group of English settlers up the Charles River to settle in what is now Watertown, Massachusetts in 1630.

He was a nephew of the Lord Mayor of London Richard Saltonst ...

were appointed to put this into effect. By the same authority it was also ordered, that Wilson's salary, until the arrival of his wife, should be 20 pounds a year. After the Charlestown church was established, most of its members moved across the Charles River

The Charles River (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ), sometimes called the River Charles or simply the Charles, is an river in eastern Massachusetts. It flows northeast from Hopkinton, Massachusetts, Hopkinton to Boston along a highly me ...

to Boston

Boston is the capital and most populous city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the United States. The city serves as the cultural and Financial centre, financial center of New England, a region of the Northeas ...

, after which services were held alternately on each side of the river, and then later only in Boston.

Well before leaving England, Wilson was married to Elizabeth Mansfield, the daughter of Sir John Mansfield, and had at least two children born in England, but his wife had initially refused to come to New England with him. Her refusal was the subject of several letters sent from John Winthrop's wife, Margaret, to her son John Winthrop Jr., in May 1631. Wilson then made a trip back to England from 1631 to 1632. Though his biographer, in 1870, stated that she still did not come back to New England with Wilson until 1635, Anderson in 1995 pointed out that the couple had a child baptized in Boston in 1633; therefore she had to have come with Wilson during this earlier trip.

On 2 July 1632 Wilson was admitted as a freeman

Freeman, free men, Freeman's or Freemans may refer to:

Places United States

* Freeman, Georgia, an unincorporated community

* Freeman, Illinois, an unincorporated community

* Freeman, Indiana, an unincorporated community

* Freeman, South Dako ...

of the colony, and later the same month the first meeting house was built in Boston. For this and Wilson's parsonage, the congregation made a voluntary contribution of 120 pounds. On 25 October 1632 Wilson, with Governor Winthrop and a few other men, set out on a friendly visit to Plymouth where they were hospitably received. They held a worship service on the Sabbath

In Abrahamic religions, the Sabbath () or Shabbat (from Hebrew ) is a day set aside for rest and worship. According to the Book of Exodus, the Sabbath is a day of rest on the seventh day, Ten Commandments, commanded by God to be kept as a Holid ...

, and that same afternoon they met again, and engaged in a discussion centered around a question posed by the Plymouth teacher, Roger Williams

Roger Williams (March 1683) was an English-born New England minister, theologian, author, and founder of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, Providence Plantations, which became the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Pl ...

. William Bradford, the Plymouth governor, and William Brewster, the ruling elder, spoke, after which Governor Winthrop and Wilson were invited to speak. The Boston men returned the following Wednesday, with Winthrop riding Governor Bradford's horse.

On 23 November, Wilson, who had previously been ordained teacher, was installed as minister of the First Church of Boston. In 1633 the church at Boston received another minister, when John Cotton arrived and was installed as teacher. In November 1633 Wilson made one of his many visits outside Boston, and went to Agawam (later Ipswich

Ipswich () is a port town and Borough status in the United Kingdom, borough in Suffolk, England. It is the county town, and largest in Suffolk, followed by Lowestoft and Bury St Edmunds, and the third-largest population centre in East Anglia, ...

), since the settlers there did not yet have a minister. He also visited the natives, tending to their sick, and instructing others who were capable of understanding him. In this regard he became the first Protestant missionary to the North American native people, a work later to be carried on with much success by Reverend John Eliot. Closer to home, Wilson sometimes led groups of Christians, including magistrates and other ministers, to the church lectures in nearby towns, sharing his "heavenly discourse" during the trip.

In late 1634, Wilson made his final trip to England, leaving the ministry of the Boston Church in the hands of his co-pastor, John Cotton, and traveling with John Winthrop Jr. While returning to England he had a harrowing experience off the coast of Ireland

Ireland (, ; ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe. Geopolitically, the island is divided between the Republic of Ireland (officially Names of the Irish state, named Irelan ...

during some violent winter weather, and though other ships perished, his landed. During his journey across Ireland and England, Wilson was able to minister to many people, and tell them about New England. In his journal, John Winthrop noted that while in Ireland, Wilson "gave much satisfaction to the Christians there about New England." Leaving England for the final time on 10 August 1635, Wilson arrived back in New England on the third of October. Soon after his return, M'Clure writes, "the Antinomian Controversy

The Antinomian Controversy, also known as the Free Grace Controversy, was a religious and political conflict in the Massachusetts Bay Colony from 1636 to 1638. It pitted most of the colony's ministers and magistrates against some adherents of ...

broke out and raged for two...years and with a fury that threatened the destruction of his church."

Antinomian Controversy

Wilson first became acquainted withAnne Hutchinson

Anne Hutchinson (; July 1591 – August 1643) was an English-born religious figure who was an important participant in the Antinomian Controversy which shook the infant Massachusetts Bay Colony from 1636 to 1638. Her strong religious formal d ...

when in 1634, as the minister of the Boston Church, he was notified of some heterodox views that she revealed while en route to New England on the ship ''Griffin''. A minister aboard the ship was questioned by her in such a way as to cause him some alarm, and word was sent to Wilson. In conference with his co-minister in Boston, the Reverend John Cotton, Hutchinson was examined, and deemed suitable for church membership, though admitted a week later than her husband because of initial uncertainty.

When Wilson returned from his England trip in 1635, he was accompanied aboard the ship ''Abigail'' by two other people who would play a role in the religious controversy to come. One of these was the Reverend

When Wilson returned from his England trip in 1635, he was accompanied aboard the ship ''Abigail'' by two other people who would play a role in the religious controversy to come. One of these was the Reverend Hugh Peter

Hugh Peter (or Peters) (baptized 29 June 1598 – 16 October 1660) was an English preacher, political advisor and soldier who supported the Parliamentary cause during the English Civil War and later the trial and execution of Charles I. Followi ...

, who became the minister in Salem

Salem may refer to:

Places

Canada

* Salem, Ontario, various places

Germany

* Salem, Baden-Württemberg, a municipality in the Bodensee district

** Salem Abbey (Reichskloster Salem), a monastery

* Salem, Schleswig-Holstein

Israel

* Salem (B ...

, and the other was a young aristocrat, Henry Vane, who soon became the governor of the colony.

In the pulpit, Wilson was said to have a voice that was harsh and indistinct and his demeanor was directed at strict discipline, but he had a penchant for rhymes, and would frequently engage in word play. He was unpopular during his early days of preaching in Boston, partly attributable to his strictness in teaching, and partly from his violent and arbitrary manner. His gruff style was further highlighted by the mild qualities of John Cotton, with whom he shared the church's ministry. When Wilson returned to Boston in 1635, Hutchinson was exposed to his teaching for the first time, and immediately saw a big difference between her own doctrines and his. She found his emphasis on morality, and his doctrine of "evidencing justification by sanctification" (a covenant of works) to be repugnant, and she told her followers that Wilson lacked "the seal of the Spirit." Wilson's doctrines were shared with all of the other ministers in the colony, except for Cotton, and the Boston congregation had grown accustomed to Cotton's lack of emphasis on preparation "in favor of stressing the inevitability of God's will." The positions of Cotton and Wilson were matters of emphasis, and neither minister believed that works could help to save a person. It is likely that most members of the Boston church could not see much difference between the doctrines of the two men, but the astute Hutchinson could, prompting her to criticize Wilson at her home gatherings. Probably in early 1636 he became aware of divisions within his own Boston congregation, and soon came to realize that Hutchinson's views were widely divergent from those of the orthodox clergy in the colony.

Wilson said nothing of his discovery, but instead preached his covenant of works even more vehemently. As soon as Winthrop became aware of what was happening, he made an entry in his journal about Hutchinson, who did "meddle in such things as are proper for men, whose minds are stronger." He also noted the 1636 arrival in the colony of Hutchinson's in-law who became an ally in religious opinion: "There joined with her in these opinions a brother of hers, one Mr. Wheelwright, a silenced minister sometimes in England."

Meetings of the ministers

In October 1636 the ministers, realizing that a theological tempest was forming in the colony, decided to get to the heart of the issue, and held a series of meetings, which also included Hutchinson and some of the magistrates. In order to deal with the theological errors of the Hutchinson group, the ministers first had to come to a consensus about their own positions, and this they were unable to do. Hutchinson's followers used this impasse to attempt to have Wheelwright appointed as another minister to the Boston church, an expression of their dissatisfaction with Wilson. Winthrop came to Wilson's rescue, as an elder in the church, by invoking a ruling requiring unanimity in a church vote, and was thus able to forestall Wheelwright's appointment there. Instead, Wheelwright was sent about ten miles south to

In October 1636 the ministers, realizing that a theological tempest was forming in the colony, decided to get to the heart of the issue, and held a series of meetings, which also included Hutchinson and some of the magistrates. In order to deal with the theological errors of the Hutchinson group, the ministers first had to come to a consensus about their own positions, and this they were unable to do. Hutchinson's followers used this impasse to attempt to have Wheelwright appointed as another minister to the Boston church, an expression of their dissatisfaction with Wilson. Winthrop came to Wilson's rescue, as an elder in the church, by invoking a ruling requiring unanimity in a church vote, and was thus able to forestall Wheelwright's appointment there. Instead, Wheelwright was sent about ten miles south to Mount Wollaston

Quincy ( ) is a city in Norfolk County, Massachusetts, United States. It is the largest city in the county. Quincy is part of the Greater Boston area as one of Boston's immediate southern suburbs. Its population in 2020 was 101,636, making it t ...

to preach.

As the meetings continued into December 1636, the theological debate escalated. Wilson delivered "a very sad speech of the condition of our churches," insinuating that Cotton, his fellow Boston minister, was partly responsible for the dissension. Wilson's speech was moved to represent the sense of the meeting, and was approved by all of the ministers and magistrates present with the notable exceptions of Governor Vane, Reverend Cotton, Reverend Wheelwright, and two strong supporters of Hutchinson, William Coddington

William Coddington (c. 1601 – 1 November 1678) was an early magistrate of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and later of the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. He served as the judge of Portsmouth and Newport in that colony, govern ...

and Richard Dummer Richard Dummer (158914 December 1679) was an early settler in New England.

He made his fortune as a trader, operating in the port of Southampton, England. He was a Puritan, which at times was contrary to the Established Church and the monarch. He ...

.

Cotton, normally of a very placid disposition, was indignant over the proceedings and lead a delegation to admonish Wilson for his uncharitable insinuations. On Saturday, 31 December 1636, the Boston congregants met to prefer charges against Wilson. Governor Vane launched the attack, and was joined by other members of the congregation. Wilson met the onslaught with a quiet dignity, and responded soberly to each of the accusations brought against him. The crowd refused to accept his excuses, and demanded a vote of censure. At this point Cotton intervened, and with more restraint than his parishioners, offered that without unanimity a vote of censure was out of order. While the ultimate indignity of censure was averted, Cotton nevertheless gave a grave exhortation to his colleague to allay the temper of the congregants. The next day Wilson preached such a conciliatory sermon that even Governor Vane rose and voiced his approval.

"Dung cast on their faces"

The Boston congregants, followers of Hutchinson, were now emboldened to seize the offensive and discredit the orthodox doctrines at services throughout the colony. The saddened Winthrop lamented, "Now the faithfull Ministers of Christ must have dung cast on their faces, and be not better than legall Preachers." As Hutchinson's followers attacked ministers with questions calculated to diminish confidence in their teachings, Winthrop continued his lament, "so many objections made by the opinionists...against our doctrine delivered, if it suited not their new fancies." When Wilson rose to preach or pray, the Hutchinsonians boldly rose and walked out of the meeting house. While Wilson was the favorite butt of this abuse, it was not restricted just to the Boston church, and similar gestures were being made toward the other ministers who preached a covenant of works. In hopes of bringing the mounting crisis under control, the General Court called for a day of fasting and repentance to be held on Thursday, 19 January 1637. During the Boston church service held that day, Cotton invited Wheelwright to come forward and deliver a sermon. Instead of the hoped-for peace, the opposite transpired. In the sermon Wheelwright stated that those who taught a covenant of works were Antichrists, and all the ministers besides Cotton saw this as being directed at them, though Wheelwright later denied this. During a meeting of the General Court in March Wheelwright was questioned at length, and ultimately charged with sedition, though not sentenced.

In hopes of bringing the mounting crisis under control, the General Court called for a day of fasting and repentance to be held on Thursday, 19 January 1637. During the Boston church service held that day, Cotton invited Wheelwright to come forward and deliver a sermon. Instead of the hoped-for peace, the opposite transpired. In the sermon Wheelwright stated that those who taught a covenant of works were Antichrists, and all the ministers besides Cotton saw this as being directed at them, though Wheelwright later denied this. During a meeting of the General Court in March Wheelwright was questioned at length, and ultimately charged with sedition, though not sentenced.

Election of May 1637

The religious division had by now become a political issue, resulting in great excitement during the elections of May 1637. The orthodox party of the majority of magistrates and ministers maneuvered to have the elections moved from Boston to Newtown (laterCambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a List of cities in the United Kingdom, city and non-metropolitan district in the county of Cambridgeshire, England. It is the county town of Cambridgeshire and is located on the River Cam, north of London. As of the 2021 Unit ...

) where the Hutchinsonians would have less support. The Boston supporters of Hutchinson wanted a petition to be read before the election, but the orthodox party insisted on holding the election first. Tempers flared, and bitter words gave way to blows as zealots on both sides clamored to have their opinions heard. During the excitement, Reverend Wilson was lifted up into a tree, and he bellowed to the crowd below, imploring them to look at their charter, to which a cry went out for the election to take place. The crowd then divided, with a majority going to one end of the common to hold the election, leaving the Boston faction in the minority by themselves. Seeing the futility of resisting further, the Boston group joined in the election.

The election was a sweeping victory for the orthodox party, with Henry Vane replaced by Winthrop as governor, and Hutchinson supporters William Coddington and Richard Dummer losing their positions as magistrates. Soon after the election, Wilson volunteered to be the minister of a military unit that went to Connecticut to settle the conflict

Conflict may refer to:

Social sciences

* Conflict (process), the general pattern of groups dealing with disparate ideas

* Conflict continuum from cooperation (low intensity), to contest, to higher intensity (violence and war)

* Conflict of ...

with the Pequot

The Pequot ( ) are a Native Americans in the United States, Native American people of Connecticut. The modern Pequot are members of the federally recognized Mashantucket Pequot Tribe, four other state-recognized groups in Connecticut includin ...

Indians. When he returned to Boston on 5 August, two days after Vane boarded a ship for England, never to return, Wilson was summoned to take part in a synod of all the colony's ministers. Many theological issues needed to be put to rest, and new issues that arose during the course of the controversy had to be dealt with.

Trials of Hutchinson

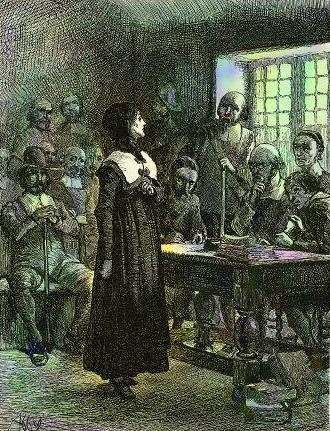

By late 1637, the conclusion of the controversy was beginning to take shape. During the court held in early November, Wheelwright was finally sentenced to banishment, the delay caused by the hopes that he would, at some point, recant. On 7 November the trial of Anne Hutchinson began, and Wilson was there with most of the other ministers in the colony, though his role was somewhat restrained. During the second day of the trial, when things seemed to be going in her favor, Hutchinson insisted on making a statement, admitting that her knowledge of things had come from a divine inspiration, prophesying her deliverance from the proceedings, and announcing that a curse would befall the colony. This was all that her judges needed to hear, and she was accused of heresy and sentenced to banishment, though she would be held in detention for four months, awaiting a trial by the clergy. While no statements made by Wilson were recorded in either existing transcript of this trial, Wilson did make a speech against Hutchinson at the end of the proceedings, to which Hutchinson responded with anger four months later during her church trial.

Her church trial took place at the Boston meeting house on two consecutive Thursdays in March 1638. Hutchinson was accused of numerous theological errors of which only four were covered during the first day, so the trial was scheduled to continue the following week, when Wilson took an active part in the proceedings. During this second day of interrogation a week later, Hutchinson read a carefully written recantation of her theological errors. Had the trial ended there, she would have likely remained in communion with the church, with the possibility of even returning there some day. Wilson, however, did not accept this recantation, and he re-opened a line of questioning from the previous week. With this, a new onslaught began, and when later given the opportunity, Wilson said, " he root of.. your errors...is the slightinge of Gods faythfull Ministers and contenminge and cryinge down them as Nobodies."

By late 1637, the conclusion of the controversy was beginning to take shape. During the court held in early November, Wheelwright was finally sentenced to banishment, the delay caused by the hopes that he would, at some point, recant. On 7 November the trial of Anne Hutchinson began, and Wilson was there with most of the other ministers in the colony, though his role was somewhat restrained. During the second day of the trial, when things seemed to be going in her favor, Hutchinson insisted on making a statement, admitting that her knowledge of things had come from a divine inspiration, prophesying her deliverance from the proceedings, and announcing that a curse would befall the colony. This was all that her judges needed to hear, and she was accused of heresy and sentenced to banishment, though she would be held in detention for four months, awaiting a trial by the clergy. While no statements made by Wilson were recorded in either existing transcript of this trial, Wilson did make a speech against Hutchinson at the end of the proceedings, to which Hutchinson responded with anger four months later during her church trial.

Her church trial took place at the Boston meeting house on two consecutive Thursdays in March 1638. Hutchinson was accused of numerous theological errors of which only four were covered during the first day, so the trial was scheduled to continue the following week, when Wilson took an active part in the proceedings. During this second day of interrogation a week later, Hutchinson read a carefully written recantation of her theological errors. Had the trial ended there, she would have likely remained in communion with the church, with the possibility of even returning there some day. Wilson, however, did not accept this recantation, and he re-opened a line of questioning from the previous week. With this, a new onslaught began, and when later given the opportunity, Wilson said, " he root of.. your errors...is the slightinge of Gods faythfull Ministers and contenminge and cryinge down them as Nobodies." Hugh Peter

Hugh Peter (or Peters) (baptized 29 June 1598 – 16 October 1660) was an English preacher, political advisor and soldier who supported the Parliamentary cause during the English Civil War and later the trial and execution of Charles I. Followi ...

chimed in, followed by Thomas Shepard, and then Wilson spoke again, "I cannot but reverence and adore the wise hand of God...in leavinge our sister to pride and Lyinge." Then John Eliot made his statement, and Wilson resumed, "Consider how we cane...longer suffer her to goe on still in seducinge to seduce, and in deacevinge to deaceve, and in lyinge to lye!"

As the battering continued, even Cotton chided her, and while concerns from the congregation brought pause to the ministers, the momentum still remained with them. When the final points of order were addressed, it was left to Wilson to deliver the final blow: "The Church consentinge to it we will proced to excommunication." He then continued, "Forasmuch as you, Mrs. Hutchinson, have highly transgressed and offended...and troubled the Church with your Errors and have drawen away many a poor soule, and have upheld your Revelations; and forasmuch as you have made a Lye...Therefor in the name of our Lord Je usChist #REDIRECT Ist

{{redirect category shell, {{R from other capitalisation{{R from ambiguous page ...

..I doe cast you out and...deliver you up to Sathan...and account you from this time forth to be a Hethen and a Publican...I command you in the name of Chist #REDIRECT Ist

{{redirect category shell, {{R from other capitalisation{{R from ambiguous page ...

Je usand of this Church as a Leper to withdraw your selfe out of the Congregation."

Later years

Hutchinson left the colony within a week of her excommunication, and following this conclusion of the Antinomian Controversy, Wilson worked with Cotton to reunite the Boston church. Following Cotton's death in 1652, his position was filled, following four years of campaigning, by John Norton from Ipswich. Norton held this position until his death in 1663. Wilson was an early advocate of the conversion of Indians to Christianity, and acted on this belief by taking the orphaned son ofWonohaquaham

Wonohaquaham, also known as Sagamore John, was a Native American leader who was a Pawtucket Confederation Sachem when English began to settle in the area.

Early life

Wonohaquaham was the oldest son of Nanepashemet and the Squaw Sachem of Mistic ...

, a local sagamore into his home to educate. In 1647 he visited the "praying Indians" of Nonantum, and noticed that they had built a house of worship that Wilson described as appearing "like the workmanship of an English housewright." During the 1650s and 1660s, in order to boost declining membership in the Boston church, Wilson supported a ruling known as the Half-Way Covenant

The Half-Way Covenant was a form of partial church membership adopted by the Congregational churches of colonial New England in the 1660s. The Puritan-controlled Congregational churches required evidence of a personal conversion experience bef ...

, allowing parishioners to be brought into the church without having had a conversion experience.

In 1656, Wilson and John Norton were the two ministers of the Boston church when the widow Ann Hibbins

Ann Hibbins (also spelled Hibbons or Hibbens) was a woman executed for witchcraft in Boston, Massachusetts Bay Colony, on June 19, 1656. Her death by hanging was the third for witchcraft in Boston and predated the Salem witch trials of 1692.Poole, ...

was convicted of witchcraft by the General Court and executed in Boston. Hibbins' husband died in 1654, and the unhappy widow was first tried the next year following complaints of her neighbors about her behavior. Details of the event are lacking, because the great Boston journalist, John Winthrop

John Winthrop (January 12, 1588 – March 26, 1649) was an English Puritan lawyer and a leading figure in the founding of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the second major settlement in New England following Plymouth Colony. Winthrop led the fir ...

was dead, and the next generations of note takers, Increase Mather

Increase Mather (; June 21, 1639 Old Style – August 23, 1723 Old Style) was a History of New England, New England Puritan clergyman in the Massachusetts Bay Colony and the sixth President of Harvard University, President of Harvard College (la ...

and Cotton Mather

Cotton Mather (; February 12, 1663 – February 13, 1728) was a Puritan clergyman and author in colonial New England, who wrote extensively on theological, historical, and scientific subjects. After being educated at Harvard College, he join ...

had not yet emerged. A 1684 letter, however, survives, written by a Reverend Beach in Jamaica

Jamaica is an island country in the Caribbean Sea and the West Indies. At , it is the third-largest island—after Cuba and Hispaniola—of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean. Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, west of Hispaniola (the is ...

to Increase Mather in New England. In the letter Beach stated that he, Wilson and others were guests at Norton's table when Norton made the statement that the only reason Hibbins was executed was because she had more wit than her neighbors, thus implying her innocence. The sentiments of Wilson are not specifically expressed in the letter, though several writers have inferred that his sentiments were the same as Norton's.

Execution of Mary Dyer

In the 1650s Quaker missionaries began filtering into the Massachusetts Bay Colony, mostly from

In the 1650s Quaker missionaries began filtering into the Massachusetts Bay Colony, mostly from Rhode Island

Rhode Island ( ) is a state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Connecticut to its west; Massachusetts to its north and east; and the Atlantic Ocean to its south via Rhode Island Sound and Block Is ...

, creating alarm among the colony's magistrates and ministers, including Wilson. In 1870, M'Clure wrote that Wilson "blended an intense love of truth with as intense a hatred of error", referring to the Quakers' marked diversion from Puritan orthodoxy.

On 27 October 1659 three Quakers— Marmaduke Stevenson, William Robinson and Mary Dyer

Mary Dyer (born Marie Barrett; c. 1611 – 1 June 1660) was an English and colonial American Puritan-turned-Quaker who was hanged in Boston, Massachusetts Bay Colony, for repeatedly defying a Puritan law banning Quakers from the colony d ...

—were led to the Boston gallows from the prison where they had been recently held for their Quaker evangelism, against which Massachusetts had enacted very strict laws. Wilson, now nearly 70, as pastor of the Boston church was on hand as the supervising minister. As the two Quaker men first approached the gallows, wearing hats, Wilson said to Robinson, "Shall such jacks as you come in before authority with your hats on?" Ignoring the barb, Robinson then let forth a barrage of words, to which Wilson angrily responded, "Hold thy tongue, be silent; thou art going to die with a lie in your mouth." The two Quaker men were then hanged, after which it was Dyer's turn to ascend the ladder. As the noose was fastened about her neck, and her face covered, a young man came running and shouting, wielding a document which he waved before the authorities. Governor Endecott had stayed her execution. After the two executions had taken place, Wilson was said to have written a ballad about the event, which was sung by young men around Boston.

Not willing to let public sentiment over the executions subside, Dyer knew that she had to go through with her martyrdom. After the winter she returned to the Bay Colony in May 1660, and was immediately arrested. On the 31st of the month she was brought before Endecott, who questioned her briefly, and then pronounced her execution for the following day. On 1 June, Dyer was once again led to the gallows, and while standing at the hanging tree for the final time, Wilson, who had received her into the Boston church 24 years earlier and had baptized her son Samuel, called to her. His words were, "Mary Dyer, O repent, O repent, and be not so deluded and carried away by deceit of the devil." Her reply was, "Nay, man, I am not now to repent." With these final words, the ladder was kicked away, and she died when her neck snapped.

Death and legacy

Wilson's final years were marked by a prolonged illness. In his will, dated 31 May 1667, Wilson remembered a large number of people, among them being several of the local ministers, including

Wilson's final years were marked by a prolonged illness. In his will, dated 31 May 1667, Wilson remembered a large number of people, among them being several of the local ministers, including Richard Mather

Richard Mather (1596 – 22 April 1669) was a New England Puritan minister in colonial Boston. He was father to Increase Mather and grandfather to Cotton Mather, both celebrated Boston theologians.

Biography

Mather was born to Thomas Mather ...

of Dorchester and Thomas Shepard Jr. of Charlestown. He died on 7 August 1667, and his son-in-law Samuel Danforth

Samuel Danforth (1626–1674) was a Puritan minister, preacher, poet, and astronomer, the second pastor of The First Church in Roxbury and an associate of the Rev. John Eliot (missionary), John Eliot of Roxbury, Massachusetts, known as the “Apos ...

wrote, "About two of the clock in the morning, my honored Father, Mr. John Wilson, Pastor to the church of Boston, aged about 78 years and an half, a man eminent in faith, love, humility, self-denial, prayer, sound ss of mind, zeal for God, liberality to all men, espcial

Cochin International Airport , popularly known as Kochi International Airport or Nedumbassery Airport, is an international airport serving the city of Kochi, Kerala, in southwestern India. It is located at Nedumbassery, about northeast of the ...

y to the s ins & ministers of Christ, rested from his labors & sorrows, beloved & lamented of all, and very honorably interred the day following." His funeral sermon was preached by local divine, Increase Mather

Increase Mather (; June 21, 1639 Old Style – August 23, 1723 Old Style) was a History of New England, New England Puritan clergyman in the Massachusetts Bay Colony and the sixth President of Harvard University, President of Harvard College (la ...

.

Wilson was notable for making anagram

An anagram is a word or phrase formed by rearranging the letters of a different word or phrase, typically using all the original letters exactly once. For example, the word ''anagram'' itself can be rearranged into the phrase "nag a ram"; which ...

s based on the names of his friends and acquaintances. M'Clure described them as numerous and nimble, and if not exact, they were always instructive, and he would rather force a poor match than lose the moral. An anecdote given by Wilson biographer M'Clure, whether true or not, points to the character of Wilson: a person met Wilson returning from a journey and remarked, "Sir, I have sad news for you: while you have been abroad, your house is burnt." To this Wilson is reputed to have replied, "Blessed be God! He has burnt this house, because he intends to give me a better."

In 1809 historian John Eliot called Wilson affable in speech, but condescending in his deportment. An early mentor of his, Dr. William Ames

William Ames (; Latin: ''Guilielmus Amesius''; 157614 November 1633) was an English Puritan minister, philosopher, and controversialist. He spent much time in the Netherlands, and is noted for his involvement in the controversy between the Ca ...

, wrote, "that if he might have his option of the best condition this side of heaven, it would be o be

O, or o, is the fifteenth letter and the fourth vowel letter of the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''o'' (pronounced ), ...

the teacher of a congregational church of which Mr. Wilson was pastor." Plymouth

Plymouth ( ) is a port city status in the United Kingdom, city and unitary authority in Devon, South West England. It is located on Devon's south coast between the rivers River Plym, Plym and River Tamar, Tamar, about southwest of Exeter and ...

historian Nathaniel Morton

Capt. Nathaniel Morton (christened 161629 June 1685) was a Separatist settler of Plymouth Colony in Massachusetts, where he served for most of his life as Plymouth's secretary under his uncle, Governor William Bradford. Morton wrote an account o ...

called him "eminent for love and zeal" and M'Clure wrote that his unfeigning modesty was excessive. In this vein, M'Clure wrote that Wilson refused to ever sit for a portrait and his response to those who suggested he do so was "What! Such a poor vile creature as I am! Shall my picture be drawn? I say No; it never shall." M'Clure then suggested that the line drawing of Wilson in the Massachusetts Historical Society was made after his death. Cotton Mather

Cotton Mather (; February 12, 1663 – February 13, 1728) was a Puritan clergyman and author in colonial New England, who wrote extensively on theological, historical, and scientific subjects. After being educated at Harvard College, he join ...

, the noted Puritan who was a grandson of both Richard Mather and John Cotton wrote of Wilson, "If the picture of this ''good'', and therein ''great'' man, were to be exactly given, great zeal, with great love, would be the two principal strokes that, joined with orthodoxy, should make up his portraiture."

Family

Wilson's wife, Elizabeth, was a sister of Anne Mansfield, the wife of the wealthy CaptainRobert Keayne

Robert Keayne (1595 – March 23, 1656) was a prominent public figure in 17th-century Boston, Massachusetts. He co-founded the Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company of Massachusetts and served as speaker of the House of the Massachusetts Ge ...

of Boston, who made a bequest to Elizabeth in his 1656 will. With his wife, Wilson had four known children, the oldest of whom, Edmund, returned to England, married, and had children. Their next child, John Jr., attended Harvard College

Harvard College is the undergraduate education, undergraduate college of Harvard University, a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Part of the Harvard Faculty of Arts and Scienc ...

in 1642 and married Sarah Hooker, the daughter of the Reverend Thomas Hooker

Thomas Hooker (July 5, 1586 – July 7, 1647) was a prominent English colonial leader and Congregational church, Congregational minister, who founded the Connecticut Colony after dissenting with Puritan leaders in Massachusetts. He was know ...

. The Wilsons then had two daughters, the older of whom, Elizabeth, married Reverend Ezekiel Rogers of Rowley, and then died while pregnant with their first child. The younger daughter, Mary, who was born in Boston on 12 September 1633, married first Reverend Samuel Danforth

Samuel Danforth (1626–1674) was a Puritan minister, preacher, poet, and astronomer, the second pastor of The First Church in Roxbury and an associate of the Rev. John Eliot (missionary), John Eliot of Roxbury, Massachusetts, known as the “Apos ...

, and following his death she married Joseph Rock.

See also

*History of Boston

The written history of Boston begins with a letter drafted by the first European inhabitant of the Shawmut Peninsula, William Blaxton. This letter is dated September 7, 1630, and was addressed to the leader of the Puritan settlement of Charles ...

*History of Massachusetts

The area that is now Massachusetts was colonized by British colonization of the Americas, English settlers in the early 17th century and became the Commonwealth of Massachusetts in the 18th century. Before that, it was inhabited by a variety of ...

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * Online sources * * *External links

Some of the works of Wilson

{{DEFAULTSORT:Wilson, John 1591 births 1667 deaths People educated at Eton College Alumni of Emmanuel College, Cambridge Alumni of King's College, Cambridge English emigrants to Massachusetts Bay Colony American religious writers 17th-century English Puritan ministers Clergy from colonial Massachusetts 17th-century New England Puritan ministers People from colonial Boston Burials at King's Chapel Burying Ground 17th-century writers in Latin American writers in Latin