John Tyler Morgan on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

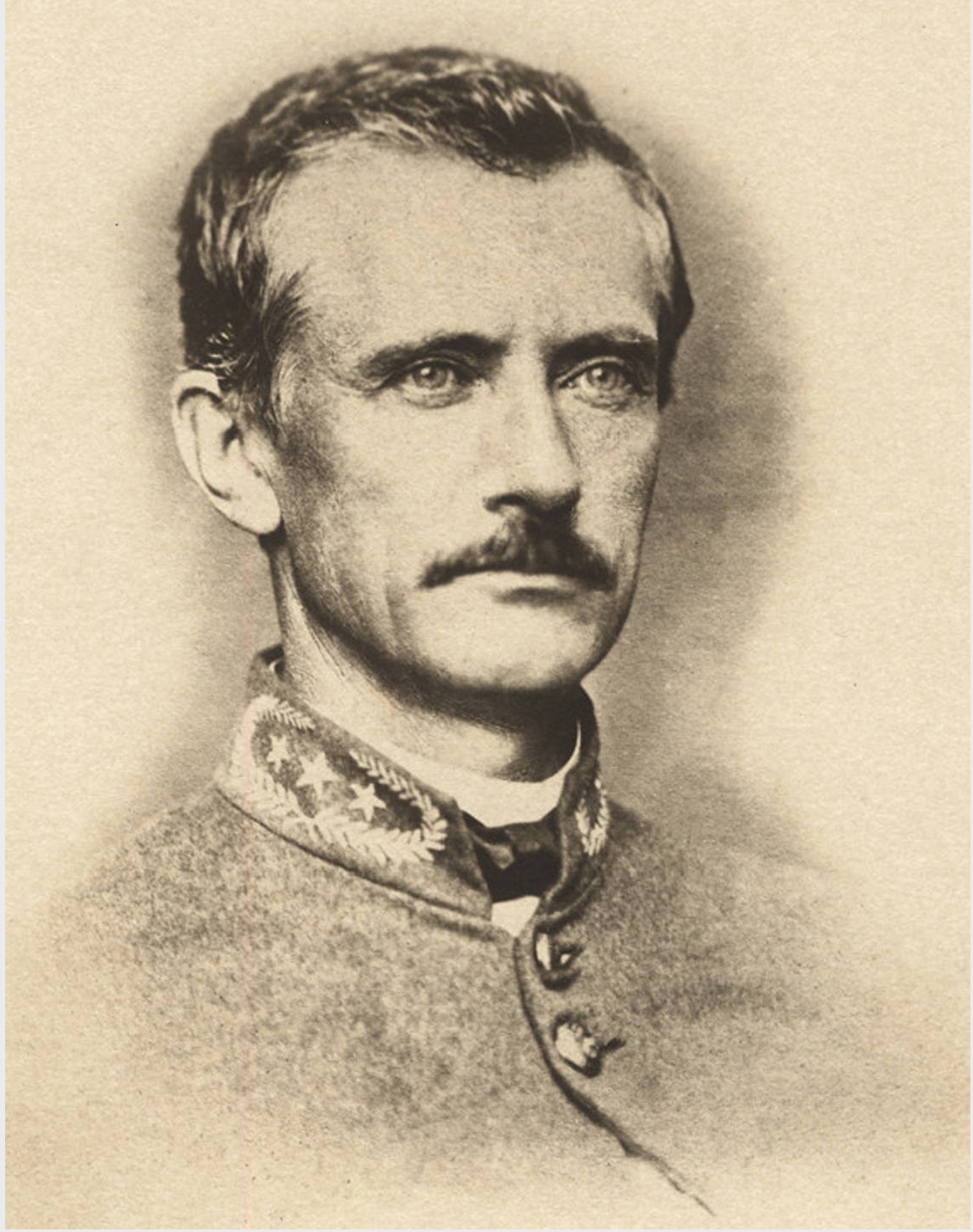

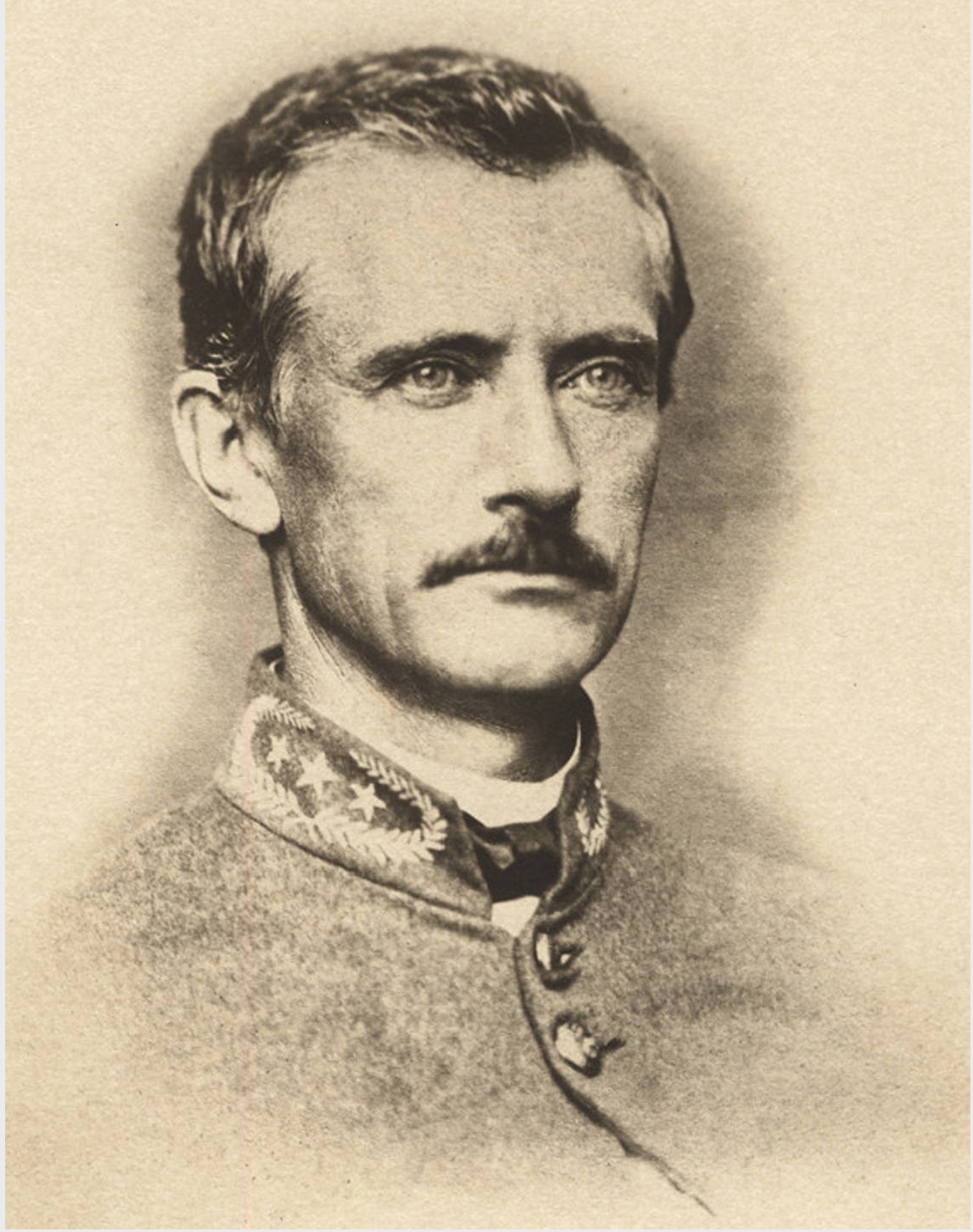

John Tyler Morgan (June 20, 1824 – June 11, 1907) was an American politician who was a brigadier general in the

After Alabama seceded from the Union and the commencement of the Civil War, the 37-year-old Morgan enlisted as a private in the Cahaba Rifles, which volunteered its services in the

After Alabama seceded from the Union and the commencement of the Civil War, the 37-year-old Morgan enlisted as a private in the Cahaba Rifles, which volunteered its services in the

morganreport.org

— Online images and transcriptions of the Morgan Report

Men of Mark in America

Biography & Portrait *

Edmund Pettus and John Tyler Morgan, late senators from Alabama, Memorial addresses (1909)

, - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Morgan, John T. 1824 births 1907 deaths Alabama Secession Delegates of 1861 American people of Welsh descent American pro-lynching activists American prisoners and detainees Confederate States Army brigadier generals Democratic Party United States senators from Alabama Ku Klux Klan Grand Dragons People from Athens, Tennessee People of Alabama in the American Civil War 1860 United States presidential electors 1876 United States presidential electors Chairmen of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations United States senators who owned slaves People from Selma, Alabama Prisoners and detainees of the United States federal government 20th-century United States senators 19th-century United States senators Fire-Eaters

Confederate States Army

The Confederate States Army (CSA), also called the Confederate army or the Southern army, was the Military forces of the Confederate States, military land force of the Confederate States of America (commonly referred to as the Confederacy) duri ...

during the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

and later was elected for six terms as the U.S. Senator

The United States Senate is a chamber of the bicameral United States Congress; it is the upper house, with the U.S. House of Representatives being the lower house. Together, the Senate and House have the authority under Article One of the ...

(1877–1907) from the state of Alabama

Alabama ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South, Deep Southern regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gu ...

. A prominent slaveholder before the Civil War, he became the second Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to KKK or Klan, is an American Protestant-led Christian terrorism, Christian extremist, white supremacist, Right-wing terrorism, far-right hate group. It was founded in 1865 during Reconstruction era, ...

in Alabama during the Reconstruction era

The Reconstruction era was a period in History of the United States, US history that followed the American Civil War (1861-65) and was dominated by the legal, social, and political challenges of the Abolitionism in the United States, abol ...

. Morgan and fellow Klan member Edmund W. Pettus became the ringleaders of white supremacy

White supremacy is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White supremacy has roots in the now-discredited doctrine ...

in Alabama and did more than anyone else in the state to overthrow Reconstruction efforts in the wake of the Civil War. When President Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was the 18th president of the United States, serving from 1869 to 1877. In 1865, as Commanding General of the United States Army, commanding general, Grant led the Uni ...

dispatched U.S. Attorney General

The United States attorney general is the head of the United States Department of Justice and serves as the chief law enforcement officer of the federal government. The attorney general acts as the principal legal advisor to the president of the ...

Amos Akerman to prosecute the Klan under the Enforcement Acts

The Enforcement Acts were three bills that were passed by the United States Congress between 1870 and 1871. They were criminal codes that protected African Americans’ right to vote, to hold office, to serve on juries, and receive equal protect ...

, Morgan was arrested and jailed.

Due to his notoriety in Alabama for opposing Reconstruction efforts, Morgan was elected as a U.S. Senator in 1876. During his subsequent six terms as Senator, he was an outspoken proponent of black disfranchisement, racial segregation

Racial segregation is the separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Segregation can involve the spatial separation of the races, and mandatory use of different institutions, ...

, and lynching African-Americans. According to historians, he played a leading role "in forging the ideology of white supremacy that dominated American race relations from the 1890s to the 1960s." Widely considered to be among the most notorious racist ideologues of his time, he is often credited by scholars with laying the foundation of the Jim Crow

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws introduced in the Southern United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that enforced racial segregation, " Jim Crow" being a pejorative term for an African American. The last of the ...

era.

In addition to his lifelong efforts to uphold white supremacy, Morgan became an ardent expansionist

Expansionism refers to states obtaining greater territory through military empire-building or colonialism.

In the classical age of conquest moral justification for territorial expansion at the direct expense of another established polity (who ...

and imperialist

Imperialism is the maintaining and extending of power over foreign nations, particularly through expansionism, employing both hard power (military and economic power) and soft power ( diplomatic power and cultural imperialism). Imperialism fo ...

during the Gilded Age

In History of the United States, United States history, the Gilded Age is the period from about the late 1870s to the late 1890s, which occurred between the Reconstruction era and the Progressive Era. It was named by 1920s historians after Mar ...

. He envisioned the United States as a globe-spanning empire and believed that island nations such as Hawaii

Hawaii ( ; ) is an island U.S. state, state of the United States, in the Pacific Ocean about southwest of the U.S. mainland. One of the two Non-contiguous United States, non-contiguous U.S. states (along with Alaska), it is the only sta ...

and the Philippines

The Philippines, officially the Republic of the Philippines, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic country in Southeast Asia. Located in the western Pacific Ocean, it consists of List of islands of the Philippines, 7,641 islands, with a tot ...

should be forcibly annexed in order for the country to dominate trade in the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five Borders of the oceans, oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is ...

. Accordingly, he advocated for the United States to annex

Annex or annexe may refer to:

Places

* The Annex, a neighbourhood in downtown Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

* The Annex (New Haven), a neighborhood of New Haven, Connecticut, United States.

* Annex, Oregon, a census-designated place in the United ...

the independent Republic of Hawaii

The Republic of Hawaii (Hawaiian language, Hawaiian: ''Lepupalika o Hawaii'' epupəˈlikə o həˈvɐjʔi was a short-lived one-party state in Hawaii, Hawaii between July 4, 1894, when the Provisional Government of Hawaii had Black Week (H ...

and to construct an inter-oceanic canal

Canals or artificial waterways are waterways or engineered channels built for drainage management (e.g. flood control and irrigation) or for conveyancing water transport vehicles (e.g. water taxi). They carry free, calm surface ...

in Central America

Central America is a subregion of North America. Its political boundaries are defined as bordering Mexico to the north, Colombia to the southeast, the Caribbean to the east, and the Pacific Ocean to the southwest. Central America is usually ...

. Due to this advocacy, he was often posthumously referred to as "the Father of the Panama Canal

The Panama Canal () is an artificial waterway in Panama that connects the Caribbean Sea with the Pacific Ocean. It cuts across the narrowest point of the Isthmus of Panama, and is a Channel (geography), conduit for maritime trade between th ...

" despite being a proponent of the Canal to be located in Nicaragua

Nicaragua, officially the Republic of Nicaragua, is the geographically largest Sovereign state, country in Central America, comprising . With a population of 7,142,529 as of 2024, it is the third-most populous country in Central America aft ...

. Morgan was a staunch opponent of women's suffrage

Women's suffrage is the women's rights, right of women to Suffrage, vote in elections. Several instances occurred in recent centuries where women were selectively given, then stripped of, the right to vote. In Sweden, conditional women's suffra ...

.

After his death by heart attack in 1907, Morgan's numerous relatives remained influential in Alabama politics and high society for many decades. His extended family owned the First White House of the Confederacy in Montgomery. His nephew and protege, Anthony Dickinson Sayre, was President of the Alabama State Senate and later an Associate Justice

An associate justice or associate judge (or simply associate) is a judicial panel member who is not the chief justice in some jurisdictions. The title "Associate Justice" is used for members of the Supreme Court of the United States and some ...

of the Supreme Court of Alabama

The Supreme Court of Alabama is the highest court in the U.S. state, state of Alabama. The court consists of a Chief Justice, chief justice and eight Associate Justice, associate justices. Each justice is elected in partisan elections for stagge ...

. Sayre played a pivotal role in passing the landmark 1893 Sayre Act which disenfranchised black Alabamians for seventy years and ushered in the Jim Crow period in the state. Morgan's grand-niece was Jazz Age

The Jazz Age was a period from 1920 to the early 1930s in which jazz music and dance styles gained worldwide popularity. The Jazz Age's cultural repercussions were primarily felt in the United States, the birthplace of jazz. Originating in New O ...

socialite Zelda Sayre, the wife of novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald.

Early life and career

John Tyler Morgan was born in a log cabin one mile fromAthens, Tennessee

Athens is the county seat of McMinn County, Tennessee, United States and the principal city of the Athens Micropolitan Statistical Area has a population of 53,569. The city is located almost equidistantly between the major cities of Knoxville a ...

. His family claimed descent from a Welsh ancestor, James B. Morgan (1607–1704), who settled in the Connecticut Colony

The Connecticut Colony, originally known as the Connecticut River Colony, was an English colony in New England which later became the state of Connecticut. It was organized on March 3, 1636, as a settlement for a Puritans, Puritan congregation o ...

. Morgan was initially educated by his mother but, in the fall of 1830, the six-year-old barefoot boy walked a quarter of a mile each day to attend Old Forest Hill Academy.

In 1833, his family moved to Calhoun County, Alabama

Calhoun County is a county in the east central part of the U.S. state of Alabama. As of the 2020 census, the population was 116,441. Its county seat is Anniston. It is named in honor of John C. Calhoun, a US Senator from South Carolina.

Cal ...

, where he attended schools and then studied law in Tuskegee with justice William Parish Chilton, his brother-in-law. After admission to the Alabama bar, he established a practice in Talladega. Ten years later, Morgan moved to Dallas County and resumed the practice of law in Selma and Cahaba. By 1857, he had grown prosperous and owned over half-a-dozen slaves—including an entire family who served as his personal household servants.

Early political activity

Turning to politics, Morgan aligned himself with the pro-slaveryFire-Eaters

In American history, the Fire-Eaters were a loosely aligned group of radical pro-secession Democrats in the antebellum South who urged the separation of the slave states into a new nation, in which chattel slavery and a distinctive "Southern ci ...

led by fellow Alabama politician William Lowndes Yancey

William Lowndes Yancey (August 10, 1814July 27, 1863) was an American politician in the Antebellum South. As an influential "Fire-Eater", he defended slavery and urged Southerners to secede from the Union in response to Northern antislavery ...

and became an ardent exponent of the Southern secession movement. He became a presidential elector

In the United States, the Electoral College is the group of presidential electors that is formed every four years for the sole purpose of voting for the president and vice president in the presidential election. This process is described in ...

on the Democratic ticket in 1860

Events

January

* January 2 – The astronomer Urbain Le Verrier announces the discovery of a hypothetical planet Vulcan (hypothetical planet), Vulcan at a meeting of the French Academy of Sciences in Paris, France.

* January 10 &ndas ...

, and tentatively supported Southern Democrat

Southern Democrats are members of the U.S. Democratic Party who reside in the Southern United States.

Before the American Civil War, Southern Democrats mostly believed in Jacksonian democracy. In the 19th century, they defended slavery in the ...

John C. Breckinridge. One year later, he was a delegate from Dallas County to the Alabama constitutional convention of 1861, and he played a key role in passing the ordinance of secession.

Amid the fractious debates at the Alabama constitutional convention, a 36-year-old Morgan defended slavery—including the transatlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade or transatlantic slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of Slavery in Africa, enslaved African people to the Americas. European slave ships regularly used the triangular trade route and its Middle Pass ...

—as a morally-uplifting and Christian institution. As a proud slaveholder, he publicly declared his reasons for advocating Alabama's secession from the Union in a speech on January 25, 1861: "The Ordinance of Secession rests, in a great measure, upon our assertion of a right to enslave the African race, or, what amounts to the same thing, to hold them in slavery." At the close of this same speech in 1861, Morgan envisioned a future slave-holding territory spanning the Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico () is an oceanic basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, mostly surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north, and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United States; on the southw ...

and the islands of the Caribbean.

American Civil War

After Alabama seceded from the Union and the commencement of the Civil War, the 37-year-old Morgan enlisted as a private in the Cahaba Rifles, which volunteered its services in the

After Alabama seceded from the Union and the commencement of the Civil War, the 37-year-old Morgan enlisted as a private in the Cahaba Rifles, which volunteered its services in the Confederate Army

The Confederate States Army (CSA), also called the Confederate army or the Southern army, was the military land force of the Confederate States of America (commonly referred to as the Confederacy) during the American Civil War (1861–1865), fi ...

and was assigned to the 5th Alabama Infantry. He first saw action in a skirmish preceding the First Battle of Manassas in the summer of 1861.

As the war progressed, Morgan rose to major

Major most commonly refers to:

* Major (rank), a military rank

* Academic major, an academic discipline to which an undergraduate student formally commits

* People named Major, including given names, surnames, nicknames

* Major and minor in musi ...

and then lieutenant colonel. He served under Col. Robert E. Rodes

Robert Emmett (or Emmet) Rodes (March 29, 1829 – September 19, 1864) was a Confederate general in the American Civil War, and the first of Robert E. Lee's divisional commanders not trained at West Point. His division led Stonewall Jackson ...

, a future Confederate general. Morgan resigned his commission in 1862 and returned to Alabama

Alabama ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern and Deep South, Deep Southern regions of the United States. It borders Tennessee to the north, Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia to the east, Florida and the Gu ...

, where in August he recruited a new regiment

A regiment is a military unit. Its role and size varies markedly, depending on the country, military service, service, or administrative corps, specialisation.

In Middle Ages, Medieval Europe, the term "regiment" denoted any large body of l ...

, the 51st Alabama Partisan Rangers, becoming its colonel. He led it at the Battle of Murfreesborough, operating in cooperation with the cavalry of Nathan Bedford Forrest

Nathan Bedford Forrest (July 13, 1821October 29, 1877) was an List of slave traders of the United States, American slave trader, active in the lower Mississippi River valley, who served as a General officers in the Confederate States Army, Con ...

.

When Rodes was promoted to major general and given a division in the Army of Northern Virginia

The Army of Northern Virginia was a field army of the Confederate States Army in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was also the primary command structure of the Department of Northern Virginia. It was most often arrayed agains ...

, Morgan declined an offer to command Rodes's old brigade

A brigade is a major tactical military unit, military formation that typically comprises three to six battalions plus supporting elements. It is roughly equivalent to an enlarged or reinforced regiment. Two or more brigades may constitute ...

and instead remained in the Western Theater, leading troops at the Battle of Chickamauga

The Battle of Chickamauga, fought on September 18–20, 1863, between the United States Army and Confederate States Army, Confederate forces in the American Civil War, marked the end of a U.S. Army offensive, the Chickamauga Campaign, in southe ...

. On November 16, 1863, he was appointed as a brigadier general of cavalry and participated in the Knoxville Campaign. His brigade consisted of the 1st, 3rd, 4th, 9th, and 51st Alabama Cavalry regiments.

His men were routed and dispersed by Federal cavalry on January 27, 1864. He was reassigned to a new command and fought in the Atlanta Campaign. Subsequently, his men harassed William T. Sherman

William is a masculine given name of Germanic origin. It became popular in England after the Norman conquest in 1066,All Things William"Meaning & Origin of the Name"/ref> and remained so throughout the Middle Ages and into the modern era. It is ...

's troops during the March to the Sea. Soon after, he was stripped of his command due to drunkenness and reassigned to administrative duty in Demopolis, Alabama

Demopolis is the largest city in Marengo County, Alabama, Marengo County, in west-central Alabama. The population was 7,162 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census.

The city lies at the confluence of the Black Warrior River and Tombigbee ...

. At the time of the Confederacy's collapse and the end of the war, Morgan attempted with little success to organize Alabama black troops for home defense.

Reconstruction era

After the war ended, Morgan resumed his law practice in Selma, Alabama. He became the affluent legal representative for the widely-loathed railroad companies. By 1867, angered by formerly enslaved persons serving as state legislators, Morgan began to play a highly public role against the Republican Reconstruction. Soon after, Morgan toured throughout the American South giving race-baiting speeches and urging fellow Southerners to refuse all compromise with Reconstruction. Aligning himself with theBourbon Democrat

Bourbon Democrat was a term used in the United States in the later 19th century and early 20th century (1872–1904) to refer to members of the Democratic Party who were ideologically aligned with fiscal conservatism or classical liberalism, es ...

s and employing their electoral strategy, Morgan wrote numerous newspaper editorials urging white Alabama voters to " redeem" their state from Republican control and to unite against African-Americans for "self-preservation.": "As a prominent hite Hite or HITE may refer to:

*HiteJinro, a South Korean brewery

**Hite Brewery

*Hite (surname)

*Hite, California, former name of Hite Cove, California

*Hite, Utah

Historic Hite is a flooded ghost town at the north end of Lake Powell along the Co ...

Redeemer, he endorsed the 'Bourbon strategy' for overthrowing Reconstruction through appeals to local autonomy, government economy, and race, and through the practice of widespread fraud and violence."

Amid his political struggle against Reconstruction in 1872, Morgan succeeded James H. Clanton as the second Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan

The Ku Klux Klan (), commonly shortened to KKK or Klan, is an American Protestant-led Christian terrorism, Christian extremist, white supremacist, Right-wing terrorism, far-right hate group. It was founded in 1865 during Reconstruction era, ...

in Alabama.: "General James H. Clanton of Montgomery was the first Grand Dragon of the Realm of Alabama Ku Klux Klan, and continued in this capacity until his death, when General John T. Morgan was elected in his place, and served until 1876. The Ku Klux Klan in 1877 was led by General Edmund W. Pettus as Grand Dragon of the Realm.": "On his death the mantle f Grand Dragonpassed to General John T. Morgan, who later became one of the most distinguished of Senators and statesmen.": "The first leader of the Klan in this state was Gen. James H. Clanton, for whom one of our fine towns is named. And on his death, the leadership passed to Alabama's Gen. John Tyler Morgan." According to Alabama Representative Robert Stell Heflin, Morgan and fellow Klan member Edmund W. Pettus became the ringleaders of white supremacy in the state who, more than anyone else, "resisted and finally broke down and destroyed the reconstruction policy which followed the Civil War."

When President Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was the 18th president of the United States, serving from 1869 to 1877. In 1865, as Commanding General of the United States Army, commanding general, Grant led the Uni ...

dispatched his U.S. Attorney General Amos T. Akerman

Amos Tappan Akerman (February 23, 1821 – December 21, 1880) was an American politician who served as United States Attorney General under President Ulysses S. Grant from 1870 to 1871.

A native of New Hampshire, Akerman graduated from Dartmou ...

to vigorously prosecute Alabama Klan under the Enforcement Acts

The Enforcement Acts were three bills that were passed by the United States Congress between 1870 and 1871. They were criminal codes that protected African Americans’ right to vote, to hold office, to serve on juries, and receive equal protect ...

, Morgan was arrested and jailed. After the demise of the first Ku Klux Klan, Morgan and Pettus continued to resist Reconstruction efforts and to reassert white supremacy in Alabama. Morgan took an active part in opposing all attempts to redress the political and socioeconomic legacies of slavery in Alabama.

Due to his efforts to suppress African-Americans from exercising their political rights and to vouchsafe white supremacy in Alabama during the Reconstruction era, Morgan became a well-known public figure in national politics and subsequently became a presidential elector-at-large on the Democratic Samuel J. Tilden ticket in 1876. Party insiders favored him to win Alabama's seat to the United States Senate in that year.

Senatorship

Following his election as U.S. Senator for the state of Alabama in 1876, Morgan was reelected five times in 1882, 1888, 1894, 1900, and 1906. He served as chairman of Committee on Rules ( 46th U.S. Congress), theCommittee on Foreign Relations

The United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations is a standing committee of the U.S. Senate charged with leading foreign-policy legislation and debate in the Senate. It is generally responsible for authorizing and overseeing foreign ai ...

( 53rd U.S. Congress), the Committee on Interoceanic Canals ( 56th and 57th Congresses), and the Committee on Public Health and National Quarantine ( 59th U.S. Congress).

He became Alabama's leading political spokesperson for nearly half-a-century. For much of his senatorial tenure, he remained aligned with the Bourbon Democrat

Bourbon Democrat was a term used in the United States in the later 19th century and early 20th century (1872–1904) to refer to members of the Democratic Party who were ideologically aligned with fiscal conservatism or classical liberalism, es ...

s, and he served in the Senate alongside his close friend Edmund W. Pettus, a former Confederate general and Klan member.: "General Edmund Pettus of Dallas County was the last person to hold that title during Reconstruction."

Throughout his senatorship, Morgan staunchly labored for the repeal of the Fifteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which was intended to prevent the denial of voting rights

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise is the right to vote in representative democracy, public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in ...

based on race. He frequently urged the disenfranchisement of black citizens in every U.S. state, and he is accordingly credited by scholars with laying the foundation of the Jim Crow

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws introduced in the Southern United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that enforced racial segregation, " Jim Crow" being a pejorative term for an African American. The last of the ...

era. In a 1890 speech, Morgan declared that, when black residents entered any area, it became necessary to "deny the right of suffrage entirely to every human being." He likened such mass disenfranchisement to having "to burn down the barn to get rid of the rats."

Morgan opposed the passage of a woman suffrage's amendment, arguing it would draw a “line of political demarcation through a man’s household”. He warned that women's suffrage would “open to the intrusion of politics and politicians that sacred circle of the family where no man should be permitted to intrude".

Due to his relentless efforts to disenfranchise black citizens across the United States and his vociferous championing of congressional legislation "to legalize the practice of racist vigilante murder ynchingas a means of preserving white power in the Deep South," Morgan is frequently credited by historians with "forging the ideology of white supremacy that dominated American race relations from the 1890s to the 1960s."

Foreign policy

Black repatriation efforts

Morgan frequently advocated for the migration of black people to leave the United States. HistorianAdam Hochschild

Adam Hochschild ( ; born October 5, 1942) is an American author, journalist, historian and lecturer. His best-known works include ''King Leopold's Ghost'' (1998), ''To End All Wars: A Story of Loyalty and Rebellion, 1914–1918'' (2011), '' Bur ...

notes that, "at various times in his long career Morgan also advocated sending them egroesto Hawaii, to Cuba, and to the Philippines—which, perhaps because the islands were so far away, he claimed were a 'native home of the negro.'"

By the 1880s, Morgan began to focus on the Congo for his repatriation visions. After the Belgian monarch Léopold II signaled that his International Association of the Congo

The International Association of the Congo (), also known as the International Congo Society, was an association founded on 17 November 1879 by Leopold II of Belgium to further his interests in the Congo. It replaced the Belgian Committee for S ...

would consider immigration and settlement of African Americans, Morgan became one of the foremost advocates of this emerging colonial enterprise in Central Africa

Central Africa (French language, French: ''Afrique centrale''; Spanish language, Spanish: ''África central''; Portuguese language, Portuguese: ''África Central'') is a subregion of the African continent comprising various countries accordin ...

. Morgan's support was vital for United States' early diplomatic recognition of the new colony, which became the Congo Free State

The Congo Free State, also known as the Independent State of the Congo (), was a large Sovereign state, state and absolute monarchy in Central Africa from 1885 to 1908. It was privately owned by Leopold II of Belgium, King Leopold II, the const ...

in December 1883.

After revelations about major atrocities by the colonial occupiers, Morgan cut his ties with the Congo Free State. He feared the brutality against the inherent African population would deter black U.S. citizens from emigrating and jeopardize his plans to create an exclusively white American nation. Hence, by 1903, Morgan became the most active U.S. congressional spokesperson of the Congo reform movement, a humanitarian pressure group that demanded reforms in the notorious Congo Free State.

The alliance between this pioneering international human rights movement and the radical white supremacist Morgan has often led to scholarly astonishment. However, the sociologist Felix Lösing pointed to the ideological nexus between the racial segregation promoted by Morgan and calls for cultural segregation raised by prominent Congo reformers. Both Morgan and the majority of the Congo reform movement were ultimately concerned with the consolidation of white supremacy on a global scale.

Support for imperialism

Between 1887 and 1907, Morgan played a leading role on the powerful Foreign Relations Committee. He called for a canal linking the Atlantic and Pacific oceans through Nicaragua, enlarging the merchant marine and the Navy, and acquiring Hawaii, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Cuba. He expected Latin American and Asian markets would become a new export market for Alabama's cotton, coal, iron, and timber. The canal would make trade with the Pacific much more feasible, and an enlarged military would protect that new trade. By 1905, most of his dreams had become reality, although the canal bifurcated Panama instead of Nicaragua. Morgan was a strong supporter of theannexation

Annexation, in international law, is the forcible acquisition and assertion of legal title over one state's territory by another state, usually following military occupation of the territory. In current international law, it is generally held t ...

of the Republic of Hawaii

The Republic of Hawaii (Hawaiian language, Hawaiian: ''Lepupalika o Hawaii'' epupəˈlikə o həˈvɐjʔi was a short-lived one-party state in Hawaii, Hawaii between July 4, 1894, when the Provisional Government of Hawaii had Black Week (H ...

, and, in 1894, Morgan chaired an investigation known as the Morgan Report

The Morgan Report was an 1894 report concluding an official U.S. Congressional investigation into the events surrounding the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom, including the alleged role of U.S. military troops (both bluejackets and marines) in ...

into the Hawaiian Revolution. The investigation concluded that the U.S. had remained completely neutral in the matter. He authored the introduction to the Morgan Report based on the findings of the investigative committee. He later visited Hawaii in 1897 in support of annexation. He believed that the history of the U.S. clearly indicated it was unnecessary to hold a plebiscite in Hawaii as a condition for annexation. He was appointed by President William McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until Assassination of William McKinley, his assassination in 1901. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Repub ...

in July 1898 to the commission created by the Newlands Resolution

The Newlands Resolution, , was a joint resolution passed on July 7, 1898, by the United States Congress to annexation, annex the independent Republic of Hawaii. In 1900, Congress created the Territory of Hawaii.

The resolution was drafted by R ...

to establish government in the Territory of Hawaii

The Territory of Hawaii or Hawaii Territory (Hawaiian language, Hawaiian: ''Panalāʻau o Hawaiʻi'') was an organized incorporated territories of the United States, organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from Apri ...

. A strong advocate for a Central American canal, Morgan was also a staunch supporter of the Cuban revolutionaries in the 1890s.

Death and legacy

While still in office, Morgan died of a heart attack inWashington, D.C.

Washington, D.C., formally the District of Columbia and commonly known as Washington or D.C., is the capital city and federal district of the United States. The city is on the Potomac River, across from Virginia, and shares land borders with ...

He was buried in Selma, Alabama, at Live Oak Cemetery, near the grave of fellow Confederate cavalry officer and Klan member Nathan Bedford Forrest. The remainder of Morgan's term was served by John H. Bankhead.

In April 2004, Professor Thomas Adams Upchurch summarized Morgan's career and legacy in the '' Alabama Review'':

Family and relatives

As the patriarch of a powerful Southern family, Morgan's extended relatives remained influential in Alabama politics for many decades and owned the First White House of the Confederacy in Montgomery. His nephew and protege, Anthony Dickinson Sayre (1858–1931), served first as a member of the Alabama State Senate (1894–95) and then as President of the Alabama State Senate (1896–97). According to historians, Morgan's nephew Anthony D. Sayre played a key role in undermining the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments in Alabama and enabling the ideology ofwhite supremacy

White supremacy is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White supremacy has roots in the now-discredited doctrine ...

. As a state legislator, he introduced the landmark 1893 Sayre Act which disenfranchised black Alabamians for nearly a century and ushered in the racially segregated Jim Crow

The Jim Crow laws were state and local laws introduced in the Southern United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that enforced racial segregation, " Jim Crow" being a pejorative term for an African American. The last of the ...

period in the state.

Later, in 1909, Governor Braxton Bragg Comer appointed Sayre as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of Alabama

The Supreme Court of Alabama is the highest court in the U.S. state, state of Alabama. The court consists of a Chief Justice, chief justice and eight Associate Justice, associate justices. Each justice is elected in partisan elections for stagge ...

. Like his uncle, Sayre was a Bourbon Democrat. Sayre married Minerva Machen (1860-1958), the daughter of Willis B. Machen, a former Confederate Senator and later a U.S. Senator

The United States Senate is a chamber of the bicameral United States Congress; it is the upper house, with the U.S. House of Representatives being the lower house. Together, the Senate and House have the authority under Article One of the ...

from Kentucky

Kentucky (, ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a landlocked U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north, West Virginia to the ...

. Sayre's daughter and Morgan's grand-niece was Jazz Age

The Jazz Age was a period from 1920 to the early 1930s in which jazz music and dance styles gained worldwide popularity. The Jazz Age's cultural repercussions were primarily felt in the United States, the birthplace of jazz. Originating in New O ...

socialite Zelda Sayre, the mentally-ill wife of novelist F. Scott Fitzgerald who wrote ''The Great Gatsby

''The Great Gatsby'' () is a 1925 novel by American writer F. Scott Fitzgerald. Set in the Jazz Age on Long Island, near New York City, the novel depicts first-person narrator Nick Carraway's interactions with Jay Gatsby, a mysterious mi ...

''. According to biographers, Zelda was extremely proud of her family and her Confederate roots, and she boasted that she drew her strength from Montgomery's Confederate past.

Morgan's great-grand-niece was Frances "Scottie" Fitzgerald. In 1973, Fitzgerald retired from Washington, D.C. to her mother Zelda Sayre's home town of Montgomery, Alabama. After her retirement, she researched her family's history and discovered her family's pivotal role in disenfranchising "the black people of Alabama, and thousands of poor whites, of the right to vote." Upon learning of this fact, Scottie felt both embarrassment and guilt. For the remainder of her life, she devoted herself to voter outreach programs in Alabama. According to Scottie, black citizens living in Montgomery still viewed the Sayre family with askance as late as the 1970s, and they would not reciprocate her social overtures.

Memorialization

* In 1913, a memorial arch was built on the grounds of the Federal Building and U.S. Courthouse in Selma, Alabama, to honor U.S. Senators Morgan and Pettus, both former Grand Dragons of the Alabama Ku Klux Klan. * In 1953, amid national tension over the ongoingBrown v. Board of Education

''Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka'', 347 U.S. 483 (1954), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court that ruled that U.S. state laws establishing racial segregation in public schools are unconstitutional, even if the ...

litigation, Morgan was elected by vote to membership in the Alabama Hall of Fame.

* In 1965, in the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that turn on question ...

ruling that segregated public schools were unconstitutional, white segregationists founded the John T. Morgan Academy in Selma. The segregation academy

Segregation academies are private schools in the Southern United States that were founded in the mid-20th century by white parents to avoid having their children attend Racial segregation in the United States, desegregated public schools. They ...

held its classes in Morgan's old house until a new campus was built in 1967.

* Morgan Hall on the campus of the University of Alabama

The University of Alabama (informally known as Alabama, UA, the Capstone, or Bama) is a Public university, public research university in Tuscaloosa, Alabama, United States. Established in 1820 and opened to students in 1831, the University of ...

, which houses the English Department, was named for him. On December 18, 2015, Morgan's portrait was removed from the building,: "The removal of the portrait of Morgan, an outspoken white supremacist, was welcomed..." and in 2016 the university was pondering the results of a petition to rename the building for Harper Lee

Nelle Harper Lee (April 28, 1926 – February 19, 2016) was an American novelist whose 1960 novel ''To Kill a Mockingbird'' won the 1961 Pulitzer Prize and became a classic of modern American literature. She assisted her close friend Truman ...

. By June 2020, the Alabama Board of Trustees had finally decided to study the names of buildings on campus and consider changing them. On September 17, 2020, they voted to remove his name from the building.

*

See also

* Ku Klux Klan members in United States politics * List of American Civil War generals (Confederate) *List of United States Congress members who died in office (1900–49)

There are several lists of United States Congress members who died in office. These include:

*List of United States Congress members who died in office (1790–1899)

*List of United States Congress members who died in office (1900–1949)

*List ...

References

Citations

Works cited

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * * *morganreport.org

— Online images and transcriptions of the Morgan Report

External links

*Men of Mark in America

Biography & Portrait *

Edmund Pettus and John Tyler Morgan, late senators from Alabama, Memorial addresses (1909)

, - , - , - , - {{DEFAULTSORT:Morgan, John T. 1824 births 1907 deaths Alabama Secession Delegates of 1861 American people of Welsh descent American pro-lynching activists American prisoners and detainees Confederate States Army brigadier generals Democratic Party United States senators from Alabama Ku Klux Klan Grand Dragons People from Athens, Tennessee People of Alabama in the American Civil War 1860 United States presidential electors 1876 United States presidential electors Chairmen of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations United States senators who owned slaves People from Selma, Alabama Prisoners and detainees of the United States federal government 20th-century United States senators 19th-century United States senators Fire-Eaters