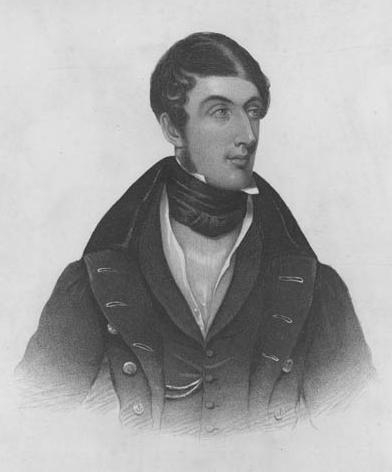

John Solomon Cartwright on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Solomon Cartwright, (September 17, 1804 – January 15, 1845) was a Canadian businessman, lawyer, judge, farmer and political figure in

Cartwright gradually accumulated a large collection of law books. When he was in England, he had spent around £250 acquiring legal texts, which he brought back to Kingston. He viewed his collection as public in nature, and readily loaned out books to other lawyers. When he was dying, he was concerned that his collection should stay in the Kingston area, and sold his library at a great discount to

Cartwright gradually accumulated a large collection of law books. When he was in England, he had spent around £250 acquiring legal texts, which he brought back to Kingston. He viewed his collection as public in nature, and readily loaned out books to other lawyers. When he was dying, he was concerned that his collection should stay in the Kingston area, and sold his library at a great discount to

In 1834, Cartwright stood for election as a Tory to represent the combined district of Lennox and Addington counties in the Legislative Assembly, the

In 1834, Cartwright stood for election as a Tory to represent the combined district of Lennox and Addington counties in the Legislative Assembly, the

/ref> The members of the

In December 1839, the new governor general, Charles Poulett Thomson (later appointed to the

In December 1839, the new governor general, Charles Poulett Thomson (later appointed to the

In nearby Napanee, it was said that every public building, including schools and churches, was built on land donated by Cartwright, including both the land and the building for the Anglican church of St. Mary Magdalene. He may have commissioned Rogers for that building as well.

In addition to Rogers, Cartwright commissioned another significant architect, George Browne, to build his country villa, Rockwood. Cartwright likely also helped Browne obtain the commission to build the Kingston Town Hall, which was designated a National Historic Site in 1961.

In nearby Napanee, it was said that every public building, including schools and churches, was built on land donated by Cartwright, including both the land and the building for the Anglican church of St. Mary Magdalene. He may have commissioned Rogers for that building as well.

In addition to Rogers, Cartwright commissioned another significant architect, George Browne, to build his country villa, Rockwood. Cartwright likely also helped Browne obtain the commission to build the Kingston Town Hall, which was designated a National Historic Site in 1961.

Kingston

Kingston may refer to:

Places

* List of places called Kingston, including the six most populated:

** Kingston, Jamaica

** Kingston upon Hull, England

** City of Kingston, Victoria, Australia

** Kingston, Ontario, Canada

** Kingston upon Thames, ...

, Upper Canada

The Province of Upper Canada () was a Province, part of The Canadas, British Canada established in 1791 by the Kingdom of Great Britain, to govern the central third of the lands in British North America, formerly part of the Province of Queb ...

. He was a supporter of the Family Compact

The Family Compact was a small closed group of men who exercised most of the political, economic and judicial power in Upper Canada (today's Ontario) from the 1810s to the 1840s. It was the Upper Canadian equivalent of the Château Clique in L ...

, an oligarchic

Oligarchy (; ) is a form of government in which power rests with a small number of people. Members of this group, called oligarchs, generally hold usually hard, but sometimes soft power through nobility, fame, wealth, or education; or throug ...

group which had dominated control of the government of Upper Canada through their influence with the British governors. He was also a member of the Compact Tory political group, first in the Legislative Assembly of Upper Canada

The Legislative Assembly of Upper Canada was the elected part of the legislature for the province of Upper Canada, functioning as the lower house in the Parliament of Upper Canada. Its legislative power was subject to veto by the appointed Li ...

, and then in the Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada

The Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada was the lower house of the Parliament of the Province of Canada. The Province of Canada consisted of the former province of Lower Canada, then known as Canada East (now Quebec), and Upper Canada ...

.

In spite of his relative youth when first elected in 1836, age 32, he was an influential member of the Compact Tory group in the Assembly. He was courted by two governors general

Governor-general (plural governors-general), or governor general (plural governors general), is the title of an official, most prominently associated with the British Empire. In the context of the governors-general and former British colonies, ...

to join the executive council of the Province of Canada The Executive Council of the Province of Canada had a similar function to the Cabinet (government), Cabinet in England but was not responsible to the Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada from its inception in 1841 to 1848.

Members were a ...

, but declined each time, not willing to associate in government with the radical Reform members of the Assembly. He favoured including French-Canadians

French Canadians, referred to as Canadiens mainly before the nineteenth century, are an ethnic group descended from French colonists first arriving in France's colony of Canada in 1608. The vast majority of French Canadians live in the provi ...

in the government of the new Province of Canada

The Province of Canada (or the United Province of Canada or the United Canadas) was a British colony in British North America from 1841 to 1867. Its formation reflected recommendations made by John Lambton, 1st Earl of Durham, in the Report ...

, but opposed the use of French in the Assembly and the courts.

In the aftermath of the Upper Canada Rebellion

The Upper Canada Rebellion was an insurrection against the Oligarchy, oligarchic government of the British colony of Upper Canada (present-day Ontario) in December 1837. While public grievances had existed for years, it was the Lower Canada Rebe ...

of 1837, he acted as a prosecutor in the trials of some alleged rebels, and was one of the military judges in the court martial of Nils von Schoultz

Nils is a Scandinavian given name, a chiefly Norwegian, Danish, Swedish and Latvian variant of Niels, cognate to Nicholas.

People and animals with the given name

* Nils Elias Anckers (1858–1921), Swedish naval officer

* Nils Beckman (1902–19 ...

, who had led an invasion force from the United States. In the trials, Cartwright worked with a rising young Kingston lawyer, John A. Macdonald

Sir John Alexander Macdonald (10 or 11January 18156June 1891) was the first prime minister of Canada, serving from 1867 to 1873 and from 1878 until his death in 1891. He was the dominant figure of Canadian Confederation, and had a political ...

, the future Prime Minister of Canada

The prime minister of Canada () is the head of government of Canada. Under the Westminster system, the prime minister governs with the Confidence and supply, confidence of a majority of the elected House of Commons of Canada, House of Commons ...

. In addition to his legal practice, he was involved in successful banking and land transactions.

Wealthy, and holding a large farming estate near Kingston

Kingston may refer to:

Places

* List of places called Kingston, including the six most populated:

** Kingston, Jamaica

** Kingston upon Hull, England

** City of Kingston, Victoria, Australia

** Kingston, Ontario, Canada

** Kingston upon Thames, ...

, Cartwright donated land and buildings for public purposes in Kingston and neighbouring Napanee

Greater Napanee is a town in southeastern Ontario, Canada, approximately west of Kingston and the county seat of Lennox and Addington County. It is located on the eastern end of the Bay of Quinte. Greater Napanee municipality was created on Jan ...

. A bon vivant, he enjoyed gambling with cards for high stakes, horse racing, and the elegancies of life, both food and good wine.

Cartwright died of tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

in 1845, aged 40.

Early life and family

John Cartwright was born inKingston

Kingston may refer to:

Places

* List of places called Kingston, including the six most populated:

** Kingston, Jamaica

** Kingston upon Hull, England

** City of Kingston, Victoria, Australia

** Kingston, Ontario, Canada

** Kingston upon Thames, ...

, Upper Canada

The Province of Upper Canada () was a Province, part of The Canadas, British Canada established in 1791 by the Kingdom of Great Britain, to govern the central third of the lands in British North America, formerly part of the Province of Queb ...

on September 17, 1804, the son of Richard Cartwright, a Loyalist

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cr ...

, and Magdalen Secord, sister-in-law of Laura Secord

Laura Secord (; 13 September 1775 – 17 October 1868) was a Canadian woman involved in the War of 1812. She is known for having walked out of American-occupied territory in 1813 to warn British forces of an impending American attack. ...

, the Loyalist heroine. John's father was engaged in commerce and politics, being a member of the Legislative Council of Upper Canada

The Legislative Council of Upper Canada was the upper house governing the province of Upper Canada. Modelled after the British House of Lords, it was created by the Constitutional Act of 1791. It was specified that the council should consist ...

. His father was also instrumental in bringing John Strachan

John Strachan (; 12 April 1778 – 1 November 1867) was a notable figure in Upper Canada, an "elite member" of the Family Compact, and the first Anglican Bishop of Toronto. He is best known as a political bishop who held many government posit ...

to Kingston, initially to tutor John and his twin brother Robert. Strachan went on to become the first Bishop of Toronto for the Church of England in Canada, and a pillar of the Family Compact

The Family Compact was a small closed group of men who exercised most of the political, economic and judicial power in Upper Canada (today's Ontario) from the 1810s to the 1840s. It was the Upper Canadian equivalent of the Château Clique in L ...

, an oligarchic

Oligarchy (; ) is a form of government in which power rests with a small number of people. Members of this group, called oligarchs, generally hold usually hard, but sometimes soft power through nobility, fame, wealth, or education; or throug ...

conservative group that had informal control over the provincial government.

Richard Cartwright died in 1815, when John and his twin brother were ten years old. He left John an inheritance of £10,000. John and Robert had older siblings, but several died of tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

.

In 1831, John married Sarah Hayter Macaulay, daughter of James Macaulay. The couple had seven children. While studying theology at Oxford University

The University of Oxford is a collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the second-oldest continuously operating u ...

, his brother Robert married Harriet Dobbs

Harriet Dobbs (August 27, 1808 – May 14, 1887), later Harriet Dobbs Cartwright, was an Irish-born Canadian philanthropist.

Early life

Harriet Dobbs, a member of the family of Castle Dobbs, County Antrim, was born in Dublin. Her parents were ...

of Ireland. Their son, John's nephew, was Sir Richard John Cartwright

Sir Richard John Cartwright (December 4, 1835 – September 24, 1912) was a Canadian businessman and politician.

Cartwright was one of Canada's most distinguished federal politicians during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. He was a ...

, who had a notable political career in the Parliament of Canada

The Parliament of Canada () is the Canadian federalism, federal legislature of Canada. The Monarchy of Canada, Crown, along with two chambers: the Senate of Canada, Senate and the House of Commons of Canada, House of Commons, form the Bicameral ...

, although as a Liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* Generally, a supporter of the political philosophy liberalism. Liberals may be politically left or right but tend to be centrist.

* An adherent of a Liberal Party (See also Liberal parties by country ...

.

Cartwright was somewhat of a throwback to the Regency era

The Regency era of British history is commonly understood as the years between and 1837, although the official regency for which it is named only spanned the years 1811 to 1820. King George III first suffered debilitating illness in the lat ...

, rather than the new Victorian period. He enjoyed horse-racing and betting, gambling with cards for high stakes, and the elegancies of life, good food and wine. Like most of the Family Compact, he was a strong supporter of the Anglican church

Anglicanism, also known as Episcopalianism in some countries, is a Western Christianity, Western Christian tradition which developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the ...

. He was also a freemason

Freemasonry (sometimes spelled Free-Masonry) consists of fraternal groups that trace their origins to the medieval guilds of stonemasons. Freemasonry is the oldest secular fraternity in the world and among the oldest still-existing organizati ...

, eventually becoming a warden of a masonic lodge in Kingston.

Legal and business career

Deciding to enter the legal profession, at the age of 16 Cartwright left home forYork

York is a cathedral city in North Yorkshire, England, with Roman Britain, Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers River Ouse, Yorkshire, Ouse and River Foss, Foss. It has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a Yor ...

, the capital of Upper Canada, where he articled

Apprenticeship is a system for training a potential new practitioners of a trade or profession with on-the-job training and often some accompanying study. Apprenticeships may also enable practitioners to gain a license to practice in a regulate ...

with John Beverley Robinson

John Beverley Robinson (February 21, 1821 – June 19, 1896) was a Canadian politician, lawyer and businessman. He was mayor of Toronto and a provincial and federal member of parliament. He was the fifth Lieutenant Governor of Ontario between ...

. Robinson was the attorney general for Upper Canada and one of the main leaders of the Upper Canada Tories

The Upper Canada Tories were formed from the elements of the Family Compact after the War of 1812. The movement was an early political party and merely a group of like-minded conservative elite in the early days of Canada.

The Tories would later ...

and the Family Compact. Following his articles with Robinson, Cartwright was called to the bar

The call to the bar is a legal term of art in most common law jurisdictions where persons must be qualified to be allowed to argue in court on behalf of another party and are then said to have been "called to the bar" or to have received "call to ...

of Upper Canada in 1825. In 1827, after the death of his mother, he went to London and studied law at Lincoln's Inn

The Honourable Society of Lincoln's Inn, commonly known as Lincoln's Inn, is one of the four Inns of Court (professional associations for Barrister, barristers and judges) in London. To be called to the bar in order to practise as a barrister ...

, while his twin brother Robert attended Oxford, studying for the ministry. Cartwright returned to Kingston in 1830, where he established his legal practice and quickly became one of Kingston's leading lawyers.

In addition to his legal practice, Cartwright was involved in banking and real estate transactions. In 1832, he became the first president of the local Kingston bank, the Commercial Bank of the Midland District. He was the unanimous choice of the bank directors, even though he was only 28 years old. Under his leadership over the next fourteen years, the Commercial Bank became the leading bank of the eastern part of the province, and was the only bank that did not suspend payments in specie during the Upper Canada Rebellion

The Upper Canada Rebellion was an insurrection against the Oligarchy, oligarchic government of the British colony of Upper Canada (present-day Ontario) in December 1837. While public grievances had existed for years, it was the Lower Canada Rebe ...

in 1837. In 1834, he became a judge in the Midland District

Midland District was one of four districts of the Province of Quebec created in 1788 in the western reaches of the Montreal District and partitioned in 1791 to create the new colony of Upper Canada.

Historical evolution

The District, originally ...

and was named Queen's Counsel

A King's Counsel (Post-nominal letters, post-nominal initials KC) is a senior lawyer appointed by the monarch (or their Viceroy, viceregal representative) of some Commonwealth realms as a "Counsel learned in the law". When the reigning monarc ...

in 1838. Although a young man in his mid-thirties, he had developed a strong reputation for prudence, sobriety and integrity in his business dealings.George Metcalf, "William Henry Draper", in J.M.S. Careless (ed.), ''The Pre-Confederation Premiers: Ontario Government Leaders, 1841–1867'' (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1980), pp. 39–41.

Cartwright also became involved in major land transactions. In addition to projects in Kingston and Napanee

Greater Napanee is a town in southeastern Ontario, Canada, approximately west of Kingston and the county seat of Lennox and Addington County. It is located on the eastern end of the Bay of Quinte. Greater Napanee municipality was created on Jan ...

, he was involved in land matters in Hamilton

Hamilton may refer to:

* Alexander Hamilton (1755/1757–1804), first U.S. Secretary of the Treasury and one of the Founding Fathers of the United States

* ''Hamilton'' (musical), a 2015 Broadway musical by Lin-Manuel Miranda

** ''Hamilton'' (al ...

, Niagara, and Montreal

Montreal is the List of towns in Quebec, largest city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, province of Quebec, the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-largest in Canada, and the List of North American cit ...

. He sold a significant tract of land in Hamilton to Allan MacNab

Sir Allan Napier MacNab, 1st Baronet (19 February 1798 – 8 August 1862) was a Canadian political leader, land speculator and property investor, lawyer, soldier, and militia commander who served in the Legislative Assembly of Upper Canada t ...

, another leading figure in the Tory political group. When one of Cartwright's good friends and business associates, James Bell Forsyth, was in serious financial difficulties, he avoided bankruptcy because Cartwright came to his financial rescue.

With the success of his legal practice and business activities, Cartwright established a country estate outside of Kingston, named Rockwood, with an attached farm. He invested heavily in his cattle and sheep, and by 1841 was winning prizes with them in the local agricultural fairs.

Cartwright gradually accumulated a large collection of law books. When he was in England, he had spent around £250 acquiring legal texts, which he brought back to Kingston. He viewed his collection as public in nature, and readily loaned out books to other lawyers. When he was dying, he was concerned that his collection should stay in the Kingston area, and sold his library at a great discount to

Cartwright gradually accumulated a large collection of law books. When he was in England, he had spent around £250 acquiring legal texts, which he brought back to Kingston. He viewed his collection as public in nature, and readily loaned out books to other lawyers. When he was dying, he was concerned that his collection should stay in the Kingston area, and sold his library at a great discount to John A. Macdonald

Sir John Alexander Macdonald (10 or 11January 18156June 1891) was the first prime minister of Canada, serving from 1867 to 1873 and from 1878 until his death in 1891. He was the dominant figure of Canadian Confederation, and had a political ...

, then a young lawyer starting his career, who went on to be the prime minister of Canada

The prime minister of Canada () is the head of government of Canada. Under the Westminster system, the prime minister governs with the Confidence and supply, confidence of a majority of the elected House of Commons of Canada, House of Commons ...

.

Rebellions of 1837–38

Cartwight was a staunch supporter of the British colonial government during theRebellions of 1837–1838

The Rebellions of 1837–1838 (), were two armed rebellion, uprisings that took place in Lower Canada, Lower and Upper Canada in 1837 and 1838. Both rebellions were motivated by frustrations with lack of political reform. A key shared goal was r ...

. He had been an officer in the local militia since 1822, and was the lieutenant-colonel of the 2nd Lennox militia during the rebellion. As an officer, Cartwright sat on the court martial

A court-martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of members of the mili ...

in 1838 which tried Nils von Schoultz

Nils is a Scandinavian given name, a chiefly Norwegian, Danish, Swedish and Latvian variant of Niels, cognate to Nicholas.

People and animals with the given name

* Nils Elias Anckers (1858–1921), Swedish naval officer

* Nils Beckman (1902–19 ...

, who had led the invaders from the United States at the Battle of the Windmill

The Battle of the Windmill was fought in November 1838 in the aftermath of the Upper Canada Rebellion. Loyalist forces of the Upper Canadian government and American troops, aided by the Royal Navy and the United States Navy, defeated an invasion b ...

, in the Patriot War

The Patriot War was a conflict along the Canada–United States border in which bands of raiders attacked the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, British colony of Upper Canada more than a dozen times between December 1837 and Decemb ...

. John A. Macdonald acted as von Schoultz's legal adviser, but under the law governing courts martial, von Shoultz had to conduct his own defence. Against Macdonald's advice, he pled guilty and assumed full responsibility for his actions. The court martial, including Cartwright, convicted von Schoultz for leading the invasion and condemned him to death. Von Schoultz was hanged at Fort Henry, Kingston, on December 8, 1838.

In the summer of 1838, Cartwright acted as the Crown prosecutor

Crown prosecutor is the title given in a number of jurisdictions to the state prosecutor, the legal party responsible for presenting the case against an individual in a criminal trial. The title is commonly used in Commonwealth realms.

Examples

* ...

in treason trials for eight individuals from the Kingston area who were alleged to have taken up arms in the rebellion. Cartwright gave them a fair prosecution, allowing the accused a considerable degree of indulgence in their defence. Macdonald was again involved, this time as full defence counsel. In these cases, the jury returned acquittals.Creighton, ''Macdonald: The Young Politician'', pp. 53–54.

Political career

Upper Canada

Member for Lennox and Addington

In 1834, Cartwright stood for election as a Tory to represent the combined district of Lennox and Addington counties in the Legislative Assembly, the

In 1834, Cartwright stood for election as a Tory to represent the combined district of Lennox and Addington counties in the Legislative Assembly, the lower house

A lower house is the lower chamber of a bicameral legislature, where the other chamber is the upper house. Although styled as "below" the upper house, in many legislatures worldwide, the lower house has come to wield more power or otherwise e ...

of the Parliament of Upper Canada

The Parliament of Upper Canada was the legislature for Upper Canada. It was created when the old Province of Quebec was split into Upper Canada and Lower Canada by the Constitutional Act of 1791.

As in other Westminster-style legislatures, it ...

, but was defeated by the two Reform movement

Reformism is a type of social movement that aims to bring a social system, social or also a political system closer to the community's ideal. A reform movement is distinguished from more Radicalism (politics), radical social movements such as re ...

candidates, Marshall Spring Bidwell

Marshall Spring Bidwell (February 16, 1799 – October 24, 1872) was a lawyer and political figure in Upper Canada.

He was born in Stockbridge, Massachusetts in 1799, the son of politician Barnabas Bidwell. His family settled in Bath in Upper ...

and Peter Perry. Cartwright came in third in the two-member riding.

Two years later, in the general election of 1836, Cartwright tried again. This time, he was successful, benefiting from the strong showing the Tories made in the election, under the leadership of the Lieutenant Governor

A lieutenant governor, lieutenant-governor, or vice governor is a high officer of state, whose precise role and rank vary by jurisdiction. Often a lieutenant governor is the deputy, or lieutenant, to or ranked under a governor — a "second-in-comm ...

, Sir Francis Bond Head

Sir Francis Bond Head, 1st Baronet Royal Guelphic Order, KCH Privy Council (United Kingdom), PC (7 December 1793 – 20 July 1875) was Lieutenant-Governor of Upper Canada during the Upper Canada Rebellion, rebellion of 1837.

Biography

Head wa ...

. The Tories had held political control in the province by means of their strong influence over the succession of governors sent from Britain.''Lord Durham's Report on the Affairs of British North America'', January 31, 1839; re-printed, with an introduction by Sir Charles Lucas (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1912), Vol. 2, pp. 148, 167./ref> The members of the

Reform movement

Reformism is a type of social movement that aims to bring a social system, social or also a political system closer to the community's ideal. A reform movement is distinguished from more Radicalism (politics), radical social movements such as re ...

challenged that oligarchic dominance, arguing for greater popular and democratic control of the provincial government. Bond Head campaigned on the basis that the election represented a choice between Tory loyalism to the Crown and Empire, and Reformer republicanism. The Tories won a substantial victory, gaining a clear majority in the Legislative Assembly. Cartwright and his fellow Tory candidate in Lennox and Addington, George Hill Detlor, defeated Bidwell and Perry. Cartwright and Detlor took their places in the thirteenth Parliament of Upper Canada.

As a member of the Legislative Assembly, Cartwright secured a charter for the town of Kingston in 1838, and helped to draw up the initial procedures for election of town officials. The Council unanimously elected him mayor, but he declined to serve. When the new governor general, Lord Durham

Earl of Durham is a title in the Peerage of the United Kingdom. It was created in 1833 for the Whig politician and colonial official John Lambton, 1st Baron Durham. Known as "Radical Jack", he played a leading role in the passing of the Refo ...

, visited Kingston on a tour of Upper Canada in the summer of 1838, Cartwright was chosen to give the welcoming address on behalf of the town.

Cartwright's conditions for union of Canadas

Following the rebellions of 1837, there was a clear understanding that there had to be structural changes in the governments of Upper Canada andLower Canada

The Province of Lower Canada () was a British colonization of the Americas, British colony on the lower Saint Lawrence River and the shores of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence established in 1791 and abolished in 1841. It covered the southern portion o ...

. The British government sent Lord Durham to investigate the political situation and to make recommendations for change. In his Report

A report is a document or a statement that presents information in an organized format for a specific audience and purpose. Although summaries of reports may be delivered orally, complete reports are usually given in the form of written documen ...

, Lord Durham recommended that the two Canadas should be re-united under a single government, with local control through the principle of responsible government

Responsible government is a conception of a system of government that embodies the principle of parliamentary accountability, the foundation of the Westminster system of parliamentary democracy. Governments (the equivalent of the executive br ...

, as used in the British Parliament. Durham also had harsh words for the Tories and the Family Compact, and their dominance of public affairs in the province, in spite of their lack of popular support.

Tories such as Cartwright were strongly opposed to Durham's recommendation for responsible government, which would reduce their power. Cartwright was deeply supportive of the British connection and British North America

British North America comprised the colonial territories of the British Empire in North America from 1783 onwards. English colonisation of North America began in the 16th century in Newfoundland, then further south at Roanoke and Jamestown, ...

's place in the British Empire, but as he explained some years later in a letter to Governor General Bagot, he viewed the principle of responsible government as unfitted to the local conditions of Upper Canada: "... with our position as a Colony, – particularly in a country where almost universal suffrage prevails, – where the great mass of the people are uneducated, – and where there is but little of that salutary influence which hereditary rank and great wealth exercises in Great Britain."

The decision on union rested with the British government, but they considered it important to have support from the local British colonists of Upper Canada. In the spring session of 1839, the Legislative Assembly debated the union proposal given by the Lieutenant Governor, Sir George Arthur, who had replaced Bond Head. By substantial majorities, the Assembly voted its general approval of the proposal, in three related resolutions. Cartwright was amongst the majority who voted in favour of the union, and voted against a proposed amendment which suggested the French-Canadians of Lower Canada had forfeited their civil and political rights by their "disloyalty" in the late rebellion. Like the other Tories, he strongly supported maintaining the British connection. As well, as a businessman, he saw the commercial advantages if Upper Canada and Lower Canada were re-united into one single province, eliminating potential trade and customs barriers.Metcalf, "William Henry Draper" in ''The Pre-Confederation Premiers'', pp. 36–37.

The Assembly then appointed a select committee to prepare instructions for a proposed delegation to London to set out the views of Upper Canadian supporters of the union. Cartwright was one of the members of the select committee. Although he supported union in principle, he was concerned that the English population of Upper Canada would lose control if united with French-speaking Lower Canada, which had a greater population. When the report of the select committee came to the Assembly for consideration, he proposed a series of conditions to seek guarantees of continued influence for Upper Canada. Key amongst the conditions were that Upper Canada would have more representatives in the new Legislative Assembly than Lower Canada; the Gaspé region would be transferred from Lower Canada to New Brunswick

New Brunswick is a Provinces and Territories of Canada, province of Canada, bordering Quebec to the north, Nova Scotia to the east, the Gulf of Saint Lawrence to the northeast, the Bay of Fundy to the southeast, and the U.S. state of Maine to ...

; the existing members of the Legislative Council of Upper Canada would be continued in office in the legislative council of the new government; the capital would be in Upper Canada; and only English would be used in the Parliament and the courts. The Legislative Assembly approved the Cartwright resolutions, and passed an additional resolution that it would be "distinctly opposed" to the union unless those resolutions were incorporated.

In December 1839, the new governor general, Charles Poulett Thomson (later appointed to the

In December 1839, the new governor general, Charles Poulett Thomson (later appointed to the peerage

A peerage is a legal system historically comprising various hereditary titles (and sometimes Life peer, non-hereditary titles) in a number of countries, and composed of assorted Imperial, royal and noble ranks, noble ranks.

Peerages include:

A ...

as Lord Sydenham), advised the Assembly that the British government could not accept the conditions proposed by the Assembly, and insisted on unconditional approval of the union. The Legislative Assembly then passed a motion of approval without the Cartwright conditions. Undeterred, in January 1840, Cartwright and the other Tories presented a pared-down list of conditions for agreement to the union. Although Cartwright was not personally present for the vote due to a personal commitment, the Assembly approved the new conditions. The final version of the Address to the Queen supported the union in principle, including the equal representation of Upper Canada and Lower Canada in the Assembly, but called for provisions that English would become the sole language in the courts and in legislative debates; that the capital should be in Upper Canada; that there be a real estate qualification for membership in the Legislature; that emigration from Britain be encouraged; and that local governments be established in Lower Canada, similar to those in Upper Canada. The Address affirmed that the people of Upper Canada wished to maintain a constitutional system based on "... the representative mode of government under a monarchy, and to a permanent connexion with the British Empire, and a dutiful allegiance to our Sovereign." On receiving this version of the Address to the Queen, Governor General Thomson advised that he agreed with the provisions, including that English should be the sole language in the courts and the Assembly.

Province of Canada

Relations with moderate Tories

In 1840, the British Parliament enacted the ''Act of Union'', which united Lower Canada and Upper Canada into theProvince of Canada

The Province of Canada (or the United Province of Canada or the United Canadas) was a British colony in British North America from 1841 to 1867. Its formation reflected recommendations made by John Lambton, 1st Earl of Durham, in the Report ...

. The Act was proclaimed in force in February 1841, and elections were held in March and April. Lower Canada was now referred to as Canada East

Canada East () was the northeastern portion of the Province of Canada. Lord Durham's Report investigating the causes of the Upper and Lower Canada Rebellions recommended merging those two colonies. The new colony, known as the Province of ...

, and Upper Canada as Canada West

The Province of Canada (or the United Province of Canada or the United Canadas) was a British colony in British North America from 1841 to 1867. Its formation reflected recommendations made by John Lambton, 1st Earl of Durham, in the Report ...

. The Act provided that English was to be the language of the Parliament, one of the conditions which Cartwright had proposed, even though Cartwright repeatedly stated that he thought French-Canadians needed to be included in the government of the province.

In his Report, Lord Durham had been highly critical of the Family Compact and its previous dominance of the government of Upper Canada. The new governor general, Thomson, made it clear that he wanted to establish a broad-based government, with representatives in the executive council from the different political groups, and a focus on commercial and economic development rather than ideological or constitutional disputes.

In light of these developments, in November 1840 the Attorney General of Upper Canada, William Draper, began corresponding with Cartwright. Draper was a moderate Tory, whose interests were mainly commercial. He had co-operated with Thomson in obtaining the Upper Canada Assembly's approval for the union. Now, with the union approaching, he sounded out Cartwright on the possibility of creating a conservative party which could unite both the high Tories of the Compact, and the more moderate Tories which Draper represented.

Cartwright was apparently interested in the possibility, but after consulting with other Compact Tories, such as Allan MacNab and Robinson (now Chief Justice of the King's Bench of Upper Canada, but still involved in politics), he ultimately rejected Draper's proposal. Unlike his colleagues, Cartwright distrusted Draper's political honesty. Cartwright's leadership role with the Compact Tories was such that his refusal to act with Draper put an end to the proposal. The two Tory factions would continue to be separate in the new Parliament.

First session of Parliament, 1841

In 1841, Cartwright was elected to the Legislative Assembly of the first Parliament of the Province of Canada, again representingLennox and Addington

Lennox and Addington was a federal electoral district represented in the House of Commons of Canada from 1904 to 1925. It was located in the province of Ontario. This riding was first created in 1903 from Addington and Lennox ridings. It co ...

. One of the first matters before the new Legislative Assembly was a series of motions indicating support for the union of Upper Canada and Lower Canada into the Province of Canada. Cartwright, along with Compact Tory members such as Allan MacNab and George Sherwood, again voted in support of the union. However, Sydenham, following his instructions from Britain, was determined to form a broad-based centrist government, and excluded the Compact Tories, precisely as Durham had advocated. The feeling was mutual: Cartwright and the other Tories generally opposed the measures proposed by Governor General Sydenham in the first session of the Parliament.

Second session of Parliament, 1842

A year later, the political situation had changed. Sydenham had died suddenly in September 1841, of tetanus caused by a fall from his horse. The new governor general, Sir Charles Bagot, was appointed in 1842. Like Sydenham, Bagot tried to put together a ministry that crossed political divisions, including Compact Tories, moderate Tories such as Draper, and even "ultra" Reformers, notablyFrancis Hincks

Sir Francis Hincks, (December 14, 1807 – August 18, 1885) was a Canadian businessman, politician, and British colonial administrator. An immigrant from Ireland, he was the Co-Premier of the Province of Canada (1851–1854), Governor of Ba ...

.Careless, ''The Union of the Canadas'', p. 64.Metcalf, "William Henry Draper" in ''The Pre-Confederation Premiers'', pp. 44–45.

Bagot offered Cartwright the position of solicitor general for Canada West. Although the Tories respected the new governor general personally, after extensive consultations with his fellow Compact Tories, Cartwright declined the offer, because he could not join a ministry with Hincks, who in his view was a radical Reformer who had given unacceptable support to the leaders of the 1837 rebellions, William Lyon Mackenzie

William Lyon Mackenzie (March12, 1795 August28, 1861) was a Scottish-born Canadian-American journalist and politician. He founded newspapers critical of the Family Compact, a term used to identify the establishment of Upper Canada. He represe ...

and Louis-Joseph Papineau

Louis-Joseph Papineau (; October 7, 1786 – September 23, 1871), born in Montreal, Province of Quebec (1763–1791), Quebec, was a politician, lawyer, and the landlord of the ''seigneurie de la Petite-Nation''. He was the leader of the reform ...

. Cartwright's refusal to enter the ministry brought the plan to an end, and had the effect of also excluding Draper, who advised Bagot that in the circumstances he could not join the new ministry. The net effect was that the governor general felt obliged to form a ministry with the strong Reformers, Robert Baldwin

Robert Baldwin (May 12, 1804 – December 9, 1858) was an Upper Canadian lawyer and politician who with his political partner Louis-Hippolyte Lafontaine of Lower Canada, led the first responsible government ministry in the Province of Canada. ...

and Louis-Hippolyte Lafontaine

Sir Louis-Hippolyte Ménard '' dit'' La Fontaine, 1st Baronet, KCMG (October 4, 1807 – February 26, 1864) was a Canadian politician who served as the first Premier of the United Province of Canada and the first head of a responsible governme ...

, as well as some moderate conservatives. The new ministry included several French-Canadian members from Canada East under Lafontaine's leadership.

Soon after the second session of Parliament was called, a resolution was introduced in support of the new ministry. MacNab and Cartwright introduced an amendment to the resolution which, although seen as critical of the new Reform-based ministry, nonetheless approved the inclusion of French-Canadian members in the ministry, stating: "... it is necessary and proper to invite that large portion of our fellow subjects who are of French origin to share in the Government of their country." The proposed amendment was defeated, demonstrating how little support the Compact Tories now had. The Compact Tories, including Cartwright, formed the nucleus of opposition to the new ministry.

Cartwright's approval of French-Canadian members in the ministry was consistent with his political views on the union. Although he opposed the use of French in the Legislative Assembly and the courts, Cartwright believed that the union could only work if French-Canadians were included in the government. Writing to Governor General Bagot in 1842, he stated that he was anxious to see the new province function well for all its citizens, and added: "But I do not see how it can be possible to arrive at this desirable end, without the concert and co-operation of the French Canadians." He was also highly critical of the conduct of the former governor general, Sydenham, in the first elections for the new Province of Canada the year before. Sydenham had gerrymandered the seats in French-speaking areas of Lower Canada to favour British voters, personally campaigned for the English party in Lower Canada, and had ignored cases where electoral violence had broken out against French-Canadian candidates, such as Lafointaine. In his letter to Bagot, Cartwright stated: "I cannot imagine how it could have ever been supposed that harmony could be produced by an act of the grossest injustice."

Third session of Parliament, 1843

= Invitation to join government

= Governor General Bagot died in May 1843, and was replaced by Sir Charles Metcalfe. A ministerial crisis was looming, as Metcalfe and his two main ministers, Lafontaine and Baldwin, entered a dispute over the appointment of government officials. It resulted in the resignation of the entire Lafontaine-Baldwin ministry in November 1843. Metcalfe then tried, as Bagot had tried the year before, to assemble a broad-based coalition that would attract general support, while excluding Lafontaine, Baldwin, and the other strong proponents ofresponsible government

Responsible government is a conception of a system of government that embodies the principle of parliamentary accountability, the foundation of the Westminster system of parliamentary democracy. Governments (the equivalent of the executive br ...

. Metcalfe invited Cartwright to consider joining the government, along with moderate Reformers from Canada West and Canada East. Cartwright attended some initial meetings, but ultimately did not agree to join the government. The moderate Reformers also refused to enter government, as did Reformers of Canada East, who continued to support Lafontaine. The result was that for a year, Metcalfe governed with a ministry of only three members, and did not recall the Legislative Assembly.

=Proposal for reform schools

= Cartwright was interested in penal reforms for juveniles, and thought that they should not be treated in the same way as adult offenders. In 1843, he proposed a form of juvenilereform school

A reform school was a Prison, penal institution, generally for teenagers, mainly operating between 1830 and 1900. In the United Kingdom and its colonies, reformatory, reformatories (commonly called reform schools) were set up from 1854 onward f ...

that he called "Juvenile Houses of Refuge", to shelter juvenile offenders. They would no longer be housed in the same facilities as adult offenders, and "... by labor and attention to their moral culture, they would become good members of society." Not all of the other members of the Assembly approved of his proposal. Cartwright's approach to the issue contrasted sharply with the harsher views of the outspoken member for Huron

Huron may refer to:

Native American ethnography

* Huron people, who have been called Wyandotte, Wyandot, Wendat and Quendat

* Huron language, an Iroquoian language

* Huron-Wendat Nation, or Huron-Wendat First Nation, or Nation Huronne-Wendat

* N ...

, William "Tiger" Dunlop

William Dunlop (19 November 1792 – 29 June 1848) also known as Tiger Dunlop, was an army officer, surgeon, Canada Company official, author, justice of the peace, militia officer, politician, and office holder. He is notable for his contributi ...

, who said in the debates that Cartwright was displaying "maudlin sensibility", and if he had his way the children would be whipped and sent to bed. Cartwright had some support from other members, including Thomas Cushing Aylwin

Thomas Cushing Aylwin (January 5, 1806 – October 14, 1871) was a lawyer, political figure and judge in Lower Canada (now Quebec). He was born in Quebec City and trained as a lawyer, including a period of education at Harvard University. ...

, the Solicitor-General for Canada East, and the matter was referred to a special committee of the Assembly. However, the proposal never came to a vote, as the Legislative Assembly was prorogued in December 1843, upon the resignation of the Lafontaine–Baldwin ministry. Juvenile reform schools would not be implemented until fifteen years later, long after Cartwright's death.

Mission to London, 1844

In 1843, the Legislative Assembly passed a motion proposing that the provincial capital be moved from Kingston to Montreal. Cartwright opposed the move. He believed that it was important to keep the capital amongst the British colonists, and that relocating it to Montreal, where the French influence would be stronger, would weaken the Province's attachment to Britain. Although in failing health from tuberculosis, in March 1844 he travelled to England to present a petition to the British government, with 16,000 signatures, opposing the proposal to move the capital. He was unsuccessful in his mission, and Montreal became the capital later in 1844. The lengthy voyage was hard on Cartwright's health, and he realised that he no longer could participate in political life. He announced his retirement to his constituents in Kingston in October 1844. Governor General Metcalfe regretted Cartwright's retirement, as he had come to rely on Cartwright as an informal advisor.Patron of architecture

Cartwright and the Cartwright family are credited in having a major effect on the architecture of public buildings in Kingston by choosing or helping influence the selection of architects. He and his brother Robert are believed to have commissioned the architect Thomas Rogers for their two townhouses in Kingston: John Cartwright's house at 221 King Street East, and Robert Cartwright's house at 191 King Street East. Cartwright also built an office building for his law practice at 223 King Street East, connected to his residence. As president of the Commercial Bank for the Midland District, Cartwright likely commissioned Rogers for the bank's Kingston building. In nearby Napanee, it was said that every public building, including schools and churches, was built on land donated by Cartwright, including both the land and the building for the Anglican church of St. Mary Magdalene. He may have commissioned Rogers for that building as well.

In addition to Rogers, Cartwright commissioned another significant architect, George Browne, to build his country villa, Rockwood. Cartwright likely also helped Browne obtain the commission to build the Kingston Town Hall, which was designated a National Historic Site in 1961.

In nearby Napanee, it was said that every public building, including schools and churches, was built on land donated by Cartwright, including both the land and the building for the Anglican church of St. Mary Magdalene. He may have commissioned Rogers for that building as well.

In addition to Rogers, Cartwright commissioned another significant architect, George Browne, to build his country villa, Rockwood. Cartwright likely also helped Browne obtain the commission to build the Kingston Town Hall, which was designated a National Historic Site in 1961.

Death

In 1843, Cartwright began to close down his farming activities. He sold off some of his property for building lots at the same time, as the town of Kingston had expanded to the area. He died at his home oftuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

January 15, 1845, two years after his twin brother Robert, also living in Kingston, died of the same disease. Their widows then joined households.

Archives

Queen's University at Kingston

Queen's University at Kingston, commonly known as Queen's University or simply Queen's, is a public university, public research university in Kingston, Ontario, Kingston, Ontario, Canada. Queen's holds more than of land throughout Ontario and ...

holds some of Cartwright's library in its rare books collection. It includes books on philosophy, religion, literature, law, history and politics. There are several volumes of bound pamphlets, piano music, and family photographs. The Queen's University Archives also include a large collection of Cartwright family documents.

There is a Cartwright Family Fonds with the Ontario provincial archives, consisting of documents from 1799 to 1913. The documents were generated by John Solomon Cartwright, his father Richard Cartwright, his brother Reverend Robert David Cartwright, Robert's wife Harriet (Dobbs) Cartwright and their son, Sir Richard Cartwright.

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Cartwright, John Solomon 1804 births 1845 deaths Canadian people of English descent Members of the Legislative Assembly of Upper Canada Members of the Legislative Assembly of the Province of Canada from Canada West Canadian lawyers Canadian King's Counsel Upper Canada judges Members of Lincoln's Inn People from Kingston, Ontario