John Newton on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

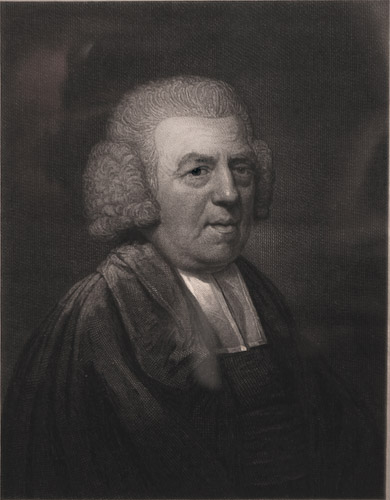

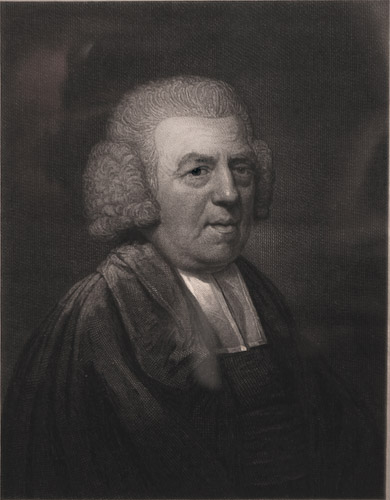

John Newton (; – 21 December 1807) was an English

In 1755, Newton was appointed as tide surveyor (a tax collector) of the

In 1755, Newton was appointed as tide surveyor (a tax collector) of the

In 1767,

In 1767,  Many of Newton's (as well as Cowper's) hymns are preserved in the ''

Many of Newton's (as well as Cowper's) hymns are preserved in the ''

In 1788, 34 years after he had retired from the slave trade, Newton broke a long silence on the subject with the publication of a forceful pamphlet ''Thoughts Upon the Slave Trade'', in which he described the horrific conditions of the slave ships during the

In 1788, 34 years after he had retired from the slave trade, Newton broke a long silence on the subject with the publication of a forceful pamphlet ''Thoughts Upon the Slave Trade'', in which he described the horrific conditions of the slave ships during the

* When he was initially interred in London, a memorial plaque to Newton, containing his self-penned epitaph, was installed on the wall of

* When he was initially interred in London, a memorial plaque to Newton, containing his self-penned epitaph, was installed on the wall of

''Thoughts Upon the African Slave Trade''

(Internet Archive with funding by Associates of the Boston Public Library ed.). London: J. Buckland & J. Johnson. Retrieved 24 May 2019. (Facsimile of original book at Archive.org. For more legible (and machine-readable) transcription, see Sources (above).)

The John Newton Project

Biography & Articles on Newton

*

* ttps://www.poeticous.com/john-newton John Newton on Poeticous* {{DEFAULTSORT:Newton, John 1725 births 1807 deaths 18th-century English Anglican priests 18th-century evangelicals 18th-century Royal Navy personnel 19th-century Anglicans 19th-century English people 19th-century evangelicals Calvinist and Reformed hymnwriters Christian humanists Christian radicals Church of England hymnwriters Converts to Anglicanism Doctors of Divinity English abolitionists English evangelicals 18th-century English slave traders Evangelical Anglican hymnwriters Evangelical Anglican clergy Evangelicalism in the Church of England Military personnel from the London Borough of Tower Hamlets People from Aveley People from Wapping Royal Navy officers Royal Navy sailors Sailors from London Christian abolitionists

evangelical

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide, interdenominational movement within Protestantism, Protestant Christianity that emphasizes evangelism, or the preaching and spreading of th ...

Anglican cleric

The Anglican ministry is both the leadership and agency of Christian service in the Anglican Communion. ''Ministry'' commonly refers to the office of ordination, ordained clergy: the ''threefold order'' of bishops, priests and deacons. Anglican m ...

and slavery abolitionist

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was Kingdom of France, France in 1315, but it was later used ...

. He had previously been a captain of slave ships and an investor in the slave trade. He served as a sailor in the Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

(after forced recruitment) and was himself enslaved for a time in West Africa. He is noted for being author of the hymns ''Amazing Grace

"Amazing Grace" is a Christian hymn written in 1772 and published in 1779 by English Anglican clergyman and poet John Newton (1725–1807). It is possibly the most sung and most recorded hymn in the world, and especially popular in the Unit ...

'' and '' Glorious Things of Thee Are Spoken''.

Newton went to sea at a young age and worked on slave ships in the slave trade Slave trade may refer to:

* History of slavery - overview of slavery

It may also refer to slave trades in specific countries, areas:

* Al-Andalus slave trade

* Atlantic slave trade

** Brazilian slave trade

** Bristol slave trade

** Danish sl ...

for several years. In 1745, he himself became a slave of Princess Peye, a woman of the Sherbro people in what is now Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone, officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered to the southeast by Liberia and by Guinea to the north. Sierra Leone's land area is . It has a tropical climate and envi ...

. He was rescued, returned to sea and the trade, becoming Captain of several slave ships. After retiring from active sea-faring, he continued to invest in the slave trade. Some years after experiencing a conversion to Christianity

Conversion to Christianity is the religious conversion of a previously non-Christian person that brings about changes in what sociologists refer to as the convert's "root reality" including their social behaviors, thinking and ethics. The sociol ...

during his rescue, Newton later renounced his trade and became a prominent supporter of abolitionism

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the political movement to end slavery and liberate enslaved individuals around the world.

The first country to fully outlaw slavery was France in 1315, but it was later used in its colonies. ...

. Now an evangelical, he was ordained as a Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

cleric and served as parish priest

A parish is a territorial entity in many Christian denominations, constituting a division within a diocese. A parish is under the pastoral care and clerical jurisdiction of a priest, often termed a parish priest, who might be assisted by one or ...

at Olney, Buckinghamshire

Olney (, rarely , rarely ) is a market town and civil parish in the unitary authority area of the City of Milton Keynes, Buckinghamshire, England. At the 2021 Census, it had a population of 6,600.

Lying on the left bank of the River Great O ...

, for two decades and wrote hymns.

Newton lived to see the British Empire's abolition of the African slave trade in 1807, just months before his death.

Early life

John Newton was born inWapping

Wapping () is an area in the borough of Tower Hamlets in London, England. It is in East London and part of the East End. Wapping is on the north bank of the River Thames between Tower Bridge to the west, and Shadwell to the east. This posit ...

, London, in 1725, the son of John Newton the Elder, a shipmaster in the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern ...

service, and Elizabeth (née Scatliff). Elizabeth was the only daughter of Simon Scatliff, an instrument maker from London. Elizabeth was brought up as a Nonconformist. She died of tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

(then called consumption) in July 1732, about two weeks before her son's seventh birthday. Newton spent two years at a boarding school

A boarding school is a school where pupils live within premises while being given formal instruction. The word "boarding" is used in the sense of "room and board", i.e. lodging and meals. They have existed for many centuries, and now extend acr ...

, before going to live at Aveley

Aveley is a village and former civil parish in the unitary authority of Thurrock in Essex, England, and forms one of the traditional Church of England parishes. Aveley is 16 miles (26.2 km) east of Charing Cross. In the 2021 United King ...

in Essex

Essex ( ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in the East of England, and one of the home counties. It is bordered by Cambridgeshire and Suffolk to the north, the North Sea to the east, Kent across the Thames Estuary to the ...

, the home of his father's new wife.

At age eleven he first went to sea with his father. Newton sailed six voyages before his father retired in 1742. At that time, Newton's father made plans for him to work at a sugarcane

Sugarcane or sugar cane is a species of tall, Perennial plant, perennial grass (in the genus ''Saccharum'', tribe Andropogoneae) that is used for sugar Sugar industry, production. The plants are 2–6 m (6–20 ft) tall with stout, jointed, fib ...

plantation

Plantations are farms specializing in cash crops, usually mainly planting a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. Plantations, centered on a plantation house, grow crops including cotton, cannabis, tob ...

in Jamaica. Instead, Newton signed on with a merchant ship sailing to the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern Eur ...

.

Impressment into naval service

In 1743, while going to visit friends, Newton was pressed into theRoyal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

. He became a midshipman

A midshipman is an officer of the lowest Military rank#Subordinate/student officer, rank in the Royal Navy, United States Navy, and many Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth navies. Commonwealth countries which use the rank include Royal Cana ...

aboard HMS ''Harwich''. At one point Newton tried to desert and was punished in front of the crew. Stripped to the waist and tied to the grating, he received a flogging

Flagellation (Latin , 'whip'), flogging or whipping is the act of beating the human body with special implements such as whips, rods, switches, the cat o' nine tails, the sjambok, the knout, etc. Typically, flogging has been imposed ...

and was reduced to the rank of a common seaman

Seaman may refer to:

* Sailor, a member of a marine watercraft's crew

* Seaman (rank), a military rank in some navies

* Seaman (name) (including a list of people with the name)

* ''Seaman'' (video game), a 1999 simulation video game for the Seg ...

.

Following that disgrace and humiliation, Newton initially contemplated murdering the captain and committing suicide by throwing himself overboard. He recovered, both physically and mentally. Later, while ''Harwich'' was en route to India, he transferred to ''Pegasus'', a slave ship

Slave ships were large cargo ships specially built or converted from the 17th to the 19th century for transporting Slavery, slaves. Such ships were also known as "Guineamen" because the trade involved human trafficking to and from the Guinea ( ...

bound for West Africa

West Africa, also known as Western Africa, is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations geoscheme for Africa#Western Africa, United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Gha ...

. The ship carried goods to Africa and traded them for slaves to be shipped to the colonies in the Caribbean and North America.

Enslavement and rescue

Newton did not get along with the crew of ''Pegasus''. In 1745, they left him in West Africa with Amos Clowe, a slave dealer. Clowe took Newton to the coast and gave him to his wife, Princess Peye of the Sherbro people. According to Newton, she abused and mistreated him just as much as she did her other slaves. Newton later recounted this period as the time he was "once an infidel and libertine, a servant of slaves in West Africa." Early in 1748, he was rescued by a sea captain who had been asked by Newton's father to search for him, and returned to England on the merchant ship ''Greyhound'', which was carryingbeeswax

Bee hive wax complex

Beeswax (also known as cera alba) is a natural wax produced by honey bees of the genus ''Apis''. The wax is formed into scales by eight wax-producing glands in the abdominal segments of worker bees, which discard it in o ...

and dyer's wood, now referred to as camwood

''Baphia nitida'', also known as camwood, barwood, and African sandalwood (although not a true sandalwood), is a shrubby, leguminous, hard-wooded tree from central west Africa. It is a small understorey, evergreen tree, often planted in villag ...

.

Christian conversion

Statue of Newton in County Donegal, on a wintry day In 1748, during his return voyage to England aboard the ship ''Greyhound'', Newton had a Christian conversion. He awoke to find the ship caught in a severe storm off the coast ofCounty Donegal

County Donegal ( ; ) is a Counties of Ireland, county of the Republic of Ireland. It is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Ulster and is the northernmost county of Ireland. The county mostly borders Northern Ireland, sharing only a small b ...

, Ireland and about to sink. In response, Newton began praying for God's mercy, after which the storm began to die down. After four weeks at sea, the ''Greyhound'' made it to port in Lough Swilly

Lough Swilly () in Ireland is a glacial fjord or sea inlet lying between the western side of the Inishowen Peninsula and the Fanad Peninsula, in County Donegal. Along with Carlingford Lough and Killary Harbour it is one of three glacial fjords ...

(Ireland). This experience marked the beginning of his conversion to Christianity.

He began to read the Bible

The Bible is a collection of religious texts that are central to Christianity and Judaism, and esteemed in other Abrahamic religions such as Islam. The Bible is an anthology (a compilation of texts of a variety of forms) originally writt ...

and other Christian literature. By the time he reached Great Britain, he had accepted the doctrines of evangelical Christianity

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide, interdenominational movement within Protestantism, Protestant Christianity that emphasizes evangelism, or the preaching and spreading of th ...

. The date was 21 March 1748, an anniversary he marked for the rest of his life. From that point on, he avoided profanity, gambling and drinking. Although he continued to work in the slave trade, he had gained sympathy for the slaves during his time in Africa. He later said that his true conversion did not happen until some time later: he wrote in 1764 "I cannot consider myself to have been a believer in the full sense of the word, until a considerable time afterwards."

Slave trading

Newton returned in 1748 toLiverpool

Liverpool is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. It is situated on the eastern side of the River Mersey, Mersey Estuary, near the Irish Sea, north-west of London. With a population ...

, a major port for the Triangular Trade

Triangular trade or triangle trade is trade between three ports or regions. Triangular trade usually evolves when a region has export commodities that are not required in the region from which its major imports come. It has been used to offset ...

. Partly due to the influence of his father's friend Joseph Manesty, he obtained a position as first mate

A chief mate (C/M) or chief officer, usually also synonymous with the first mate or first officer, is a licensed mariner and head of the deck department of a merchant ship. The chief mate is customarily a watchstander and is in charge of the shi ...

aboard the slave ship ''Brownlow,'' bound for the West Indies

The West Indies is an island subregion of the Americas, surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, which comprises 13 independent island country, island countries and 19 dependent territory, dependencies in thr ...

via the coast of Guinea. After his return to England in 1750, he made three voyages as captain of the slave ships ''Duke of Argyle'' (1750) and ''African'' (1752–53 and 1753–54). After suffering a severe stroke in 1754, he gave up seafaring, while continuing to invest in Manesty's slaving operations.

After Newton moved to the City of London

The City of London, also known as ''the City'', is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county and Districts of England, local government district with City status in the United Kingdom, city status in England. It is the Old town, his ...

as rector of St Mary Woolnoth Church, he contributed to the work of the Committee for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, formed in 1787. During this time he wrote ''Thoughts Upon the African Slave Trade''. In it he states, "So much light has been thrown upon the subject, by many able pens; and so many respectable persons have already engaged to use their utmost influence, for the suppression of a traffic, which contradicts the feelings of humanity; that it is hoped, this stain of our National character will soon be wiped out."

Marriage and family

On 12 February 1750, Newton married his childhood sweetheart, Mary Catlett, at St. Margaret's Church, Rochester. Newton adopted his two orphaned nieces, Elizabeth Cunningham and Eliza Catlett, both from the Catlett side of the family. Newton's niece Alys Newton later married Mehul, a prince from India.Anglican priest

In 1755, Newton was appointed as tide surveyor (a tax collector) of the

In 1755, Newton was appointed as tide surveyor (a tax collector) of the Port of Liverpool

The Port of Liverpool is the enclosed dock system that runs from Brunswick Dock in Liverpool to Seaforth Dock, Seaforth, on the east side of the River Mersey and the Birkenhead Docks between Birkenhead and Wallasey on the west side of ...

, again through the influence of Manesty. In his spare time, he studied Greek, Hebrew

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

, and Syriac, preparing for serious religious study. He became well known as an evangelical lay minister. In 1757, he applied to be ordained

Ordination is the process by which individuals are Consecration in Christianity, consecrated, that is, set apart and elevated from the laity class to the clergy, who are thus then authorized (usually by the religious denomination, denominationa ...

as a priest in the Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the State religion#State churches, established List of Christian denominations, Christian church in England and the Crown Dependencies. It is the mother church of the Anglicanism, Anglican Christian tradition, ...

, but it was more than seven years before he was eventually accepted.

During this period, he also applied to the Independents and Presbyterians

Presbyterianism is a historically Reformed Protestant tradition named for its form of church government by representative assemblies of elders, known as "presbyters". Though other Reformed churches are structurally similar, the word ''Pr ...

. He mailed applications directly to the Bishops of Chester

The Bishop of Chester is the Ordinary (officer), Ordinary of the Church of England Diocese of Chester in the Province of York.

The diocese extends across most of the Historic counties of England, historic county boundaries of Cheshire, includi ...

and Lincoln and the Archbishops of Canterbury

Canterbury (, ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, city and UNESCO World Heritage Site, in the county of Kent, England; it was a county borough until 1974. It lies on the River Stour, Kent, River Stour. The city has a mild oceanic climat ...

and York

York is a cathedral city in North Yorkshire, England, with Roman Britain, Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers River Ouse, Yorkshire, Ouse and River Foss, Foss. It has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a Yor ...

.

Eventually, in 1764, he was introduced by Thomas Haweis

Thomas Haweis (c.1734–1820), (surname pronounced to rhyme with "pause") was born in Redruth, Cornwall, on 1 January 1734, where he was baptised on 20 February 1734. As a Church of England cleric he was one of the leading figures of the 18th ce ...

to The 2nd Earl of Dartmouth, who was influential in recommending Newton to William Markham, Bishop of Chester. Haweis suggested Newton for the living

Living or The Living may refer to:

Common meanings

*Life, a condition that distinguishes organisms from inorganic objects and dead organisms

** Living species, one that is not extinct

*Personal life, the course of an individual human's life

* ...

of Olney, Buckinghamshire

Buckinghamshire (, abbreviated ''Bucks'') is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South East England and one of the home counties. It is bordered by Northamptonshire to the north, Bedfordshire to the north-east, Hertfordshir ...

. On 29 April 1764 Newton received deacon's orders, and finally was ordained as a priest on 17 June.

As curate of Olney, Newton was partly sponsored by John Thornton, a wealthy merchant and evangelical philanthropist. He supplemented Newton's stipend of £60 a year with £200 a year "for hospitality and to help the poor". Newton soon became well known for his pastoral care, as much as for his beliefs. His friendship with Dissenters

A dissenter (from the Latin , 'to disagree') is one who dissents (disagrees) in matters of opinion, belief, etc. Dissent may include political opposition to decrees, ideas or doctrines and it may include opposition to those things or the fiat of ...

and evangelical clergy led to his being respected by Anglicans and Nonconformists alike. He spent sixteen years at Olney. His preaching was so popular that the congregation added a gallery to the church to accommodate the many persons who flocked to hear him.

Some five years later, in 1772, Thomas Scott took up the curacy of the neighbouring parishes of Stoke Goldington and Weston Underwood. Newton was instrumental in converting Scott from a cynical 'career priest' to a true believer, a conversion which Scott related in his spiritual autobiography ''The Force of Truth'' (1779). Later Scott became a biblical commentator and co-founder of the Church Missionary Society

The Church Mission Society (CMS), formerly known as the Church Missionary Society, is a British Anglican mission society working with Christians around the world. Founded in 1799, CMS has attracted over nine thousand men and women to serve as ...

.

In 1779, Newton was invited by John Thornton to become Rector of St Mary Woolnoth

St Mary Woolnoth is an Anglican church in the City of London, located on the corner of Lombard Street, London, Lombard Street and King William Street, London, King William Street near Bank junction. The present building is one of the Commission f ...

, Lombard Street, London, where he officiated until his death. The church had been built by Nicholas Hawksmoor

Nicholas Hawksmoor ( – 25 March 1736) was an English architect. He was a leading figure of the English Baroque style of architecture in the late-seventeenth and early-eighteenth centuries. Hawksmoor worked alongside the principal architects ...

in 1727 in the fashionable Baroque style

The Baroque ( , , ) is a Western style of architecture, music, dance, painting, sculpture, poetry, and other arts that flourished from the early 17th century until the 1750s. It followed Renaissance art and Mannerism and preceded the Rococo (i ...

. Newton was one of only two evangelical Anglican priests in the capital, and he soon found himself gaining in popularity amongst the growing evangelical party. He was a strong supporter of evangelicalism in the Church of England. He remained a friend of Dissenters (such as Methodists post-Wesley, and Baptists) as well as Anglicans.

Young churchmen and people struggling with faith sought his advice, including such well-known social figures as the writer and philanthropist Hannah More

Hannah More (2 February 1745 – 7 September 1833) was an English religious writer, philanthropist, poet, and playwright in the circle of Johnson, Reynolds and Garrick, who wrote on moral and religious subjects. Born in Bristol, she taught at ...

, and the young William Wilberforce

William Wilberforce (24 August 1759 – 29 July 1833) was a British politician, philanthropist, and a leader of the movement to abolish the Atlantic slave trade. A native of Kingston upon Hull, Yorkshire, he began his political career in 1780 ...

, a member of parliament (MP) who had recently suffered a crisis of conscience and religious conversion while contemplating leaving politics. The younger man consulted with Newton, who encouraged Wilberforce to stay in Parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

and "serve God where he was".

In 1792, Newton was presented with the degree of Doctor of Divinity

A Doctor of Divinity (DD or DDiv; ) is the holder of an advanced academic degree in divinity (academic discipline), divinity (i.e., Christian theology and Christian ministry, ministry or other theologies. The term is more common in the Englis ...

by the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University).

Writer and hymnist

In 1767,

In 1767, William Cowper

William Cowper ( ; – 25 April 1800) was an English poet and Anglican hymnwriter.

One of the most popular poets of his time, Cowper changed the direction of 18th-century nature poetry by writing of everyday life and scenes of the Engli ...

, the poet, moved to Olney. He worshipped in Newton's church, and collaborated with the priest on a volume of hymns; it was published as ''Olney Hymns

The ''Olney Hymns'' were first published in February 1779 and are the combined work of curate John Newton (1725–1807) and his poet friend William Cowper (1731–1800). The hymns were written for use in Newton's rural parish, which was made u ...

'' in 1779. This work had a great influence on English hymnology. The volume included Newton's well-known hymns: " Glorious Things of Thee Are Spoken", " How Sweet the Name of Jesus Sounds!", and "Faith's Review and Expectation", which has come to be known by its opening phrase, "Amazing Grace

"Amazing Grace" is a Christian hymn written in 1772 and published in 1779 by English Anglican clergyman and poet John Newton (1725–1807). It is possibly the most sung and most recorded hymn in the world, and especially popular in the Unit ...

".

Many of Newton's (as well as Cowper's) hymns are preserved in the ''

Many of Newton's (as well as Cowper's) hymns are preserved in the ''Sacred Harp

Sacred Harp singing is a tradition of sacred choral music which developed in New England and perpetuated in the American South. The name is derived from ''The Sacred Harp'', a historically important shape notes, shape-note tunebook printed in ...

,'' a hymnal used in the American South during the Second Great Awakening

The Second Great Awakening was a Protestant religious revival during the late 18th to early 19th century in the United States. It spread religion through revivals and emotional preaching and sparked a number of reform movements. Revivals were a k ...

. Hymns were scored according to the tonal scale for shape note singing. Easily learnt and incorporating singers into four-part harmony, shape note music was widely used by evangelical preachers to reach new congregants.

In 1776, Newton contributed a preface to an annotated version of John Bunyan

John Bunyan (; 1628 – 31 August 1688) was an English writer and preacher. He is best remembered as the author of the Christian allegory ''The Pilgrim's Progress'', which also became an influential literary model. In addition to ''The Pilgrim' ...

's ''The Pilgrim's Progress

''The Pilgrim's Progress from This World, to That Which Is to Come'' is a 1678 Christian allegory written by John Bunyan. It is commonly regarded as one of the most significant works of Protestant devotional literature and of wider early moder ...

''.

Newton also contributed to the Cheap Repository Tracts. He wrote an autobiography entitled ''An Authentic Narrative of Some Remarkable And Interesting Particulars in the Life of ------ Communicated, in a Series of Letters, to the Reverend T. Haweis, Rector of Aldwinckle, And by him, at the request of friends, now made public'', which he published anonymously in 1764 with a Preface by Haweis. It was later described as "written in an easy style, distinguished by great natural shrewdness, and sanctified by the Lord God and prayer".

Abolitionist

In 1788, 34 years after he had retired from the slave trade, Newton broke a long silence on the subject with the publication of a forceful pamphlet ''Thoughts Upon the Slave Trade'', in which he described the horrific conditions of the slave ships during the

In 1788, 34 years after he had retired from the slave trade, Newton broke a long silence on the subject with the publication of a forceful pamphlet ''Thoughts Upon the Slave Trade'', in which he described the horrific conditions of the slave ships during the Middle Passage

The Middle Passage was the stage of the Atlantic slave trade in which millions of Africans sold for enslavement were forcibly transported to the Americas as part of the triangular slave trade. Ships departed Europe for African markets with manu ...

. He apologised for "a confession, which ... comes too late ... It will always be a subject of humiliating reflection to me, that I was once an active instrument in a business at which my heart now shudders." He had copies sent to every MP, and the pamphlet sold so well that it swiftly required reprinting.

Newton became an ally of William Wilberforce, leader of the Parliamentary campaign to abolish the African slave trade. He lived to see the British passage of the Slave Trade Act 1807

The Slave Trade Act 1807 ( 47 Geo. 3 Sess. 1. c. 36), or the Abolition of Slave Trade Act 1807, was an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom prohibiting the Atlantic slave trade in the British Empire. Although it did not automatica ...

, which enacted this event.

Newton came to believe that during the first five of his nine years as a slave trader he had not been a Christian in the full sense of the term. In 1763 he wrote: "I was greatly deficient in many respects ... I cannot consider myself to have been a believer in the full sense of the word, until a considerable time afterwards."

Final years

Newton's wife Mary Catlett died in 1790, after which he published ''Letters to a Wife'' (1793), in which he expressed his grief. Plagued by ill health and failing eyesight, Newton died on 21 December 1807 in London. He was buried beside his wife in St. Mary Woolnoth in London. Both were reinterred at the Church of Saints Peter and Paul, Olney in 1893.Commemoration

St Mary Woolnoth

St Mary Woolnoth is an Anglican church in the City of London, located on the corner of Lombard Street, London, Lombard Street and King William Street, London, King William Street near Bank junction. The present building is one of the Commission f ...

. At the bottom of the plaque are the words: "The above Epitaph was written by the Deceased who directed it to be inscribed on a plain Marble Tablet. He died on Dec. the 21st, 1807. Aged 82 Years, and his mortal Remains are deposited in the Vault beneath this Church."

* Newton is memorialised with his self-penned epitaph on the side of his tomb at Olney: JOHN NEWTON. Clerk. Once an infidel and libertine a servant of slaves in Africa was by the rich mercy of our LORD and SAVIOUR JESUS CHRIST preserved, restored, pardoned and appointed to preach the faith he had long laboured to destroy. Near 16 years as Curate of this parish and 28 years as Rector of St. Mary Woolnoth.

*The town of Newton in Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone, officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered to the southeast by Liberia and by Guinea to the north. Sierra Leone's land area is . It has a tropical climate and envi ...

is named after him. To this day his former town of Olney provides philanthropy for the African town.

*In 1982, Newton was recognised for his influential hymns by the Gospel Music Association

The Gospel Music Association (GMA) is a nonprofit organization founded in 1964 for the purpose of supporting and promoting the development of all forms of gospel music. As of 2011, there are about 4,000 members worldwide. The GMA's membership c ...

when he was inducted into the Gospel Music Hall of Fame

The Gospel Music Hall of Fame, created in 1972 by the Gospel Music Association, is a hall of fame dedicated exclusively to recognizing meaningful contributions by individuals and groups in all forms of gospel music.

Inductees

This is an incompl ...

.

*A memorial to him was erected in Buncrana

Buncrana ( ; ) is a town in Inishowen in the north of County Donegal in Ulster, the northern Provinces of Ireland, province in Ireland. The town sits on the eastern shores of Lough Swilly, being northwest of Derry and north of Letterkenny. I ...

in Inishowen

Inishowen () is a peninsula in the north of County Donegal in Ireland. Inishowen is the largest peninsula on the island of Ireland.

The Inishowen peninsula includes Ireland's most northerly point, Malin Head. The Grianan of Aileach, a ringfor ...

, County Donegal

County Donegal ( ; ) is a Counties of Ireland, county of the Republic of Ireland. It is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Ulster and is the northernmost county of Ireland. The county mostly borders Northern Ireland, sharing only a small b ...

, in Ulster

Ulster (; or ; or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional or historic provinces of Ireland, Irish provinces. It is made up of nine Counties of Ireland, counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kingdom); t ...

in 2013. Buncrana is located on the shores of Lough Swilly

Lough Swilly () in Ireland is a glacial fjord or sea inlet lying between the western side of the Inishowen Peninsula and the Fanad Peninsula, in County Donegal. Along with Carlingford Lough and Killary Harbour it is one of three glacial fjords ...

.

Portrayals in media

Film

* The film ''Amazing Grace

"Amazing Grace" is a Christian hymn written in 1772 and published in 1779 by English Anglican clergyman and poet John Newton (1725–1807). It is possibly the most sung and most recorded hymn in the world, and especially popular in the Unit ...

'' (2006) highlights Newton's influence on William Wilberforce

William Wilberforce (24 August 1759 – 29 July 1833) was a British politician, philanthropist, and a leader of the movement to abolish the Atlantic slave trade. A native of Kingston upon Hull, Yorkshire, he began his political career in 1780 ...

. Albert Finney

Albert Finney (9 May 1936 – 7 February 2019) was an English actor. He attended the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art and worked in the theatre before attaining fame for movie acting during the early 1960s, debuting with '' The Entertainer'' ( ...

portrays Newton, Ioan Gruffudd is Wilberforce, and the film was directed by Michael Apted

Michael David Apted (10 February 1941 – 7 January 2021) was an English television and film director and producer.

Apted began working in television and directed the ''Up (film series), Up'' documentary series from 1970 to 2019). He later di ...

. The film portrays Newton as a penitent haunted by the ghosts of 20,000 slaves.

* The Nigerian film '' The Amazing Grace'' (2006), the creation of Nigerian director/writer/producer Jeta Amata, provides an African perspective on the slave trade. Nigerian actors Joke Silva, Mbong Odungide, and Fred Amata (brother of the director) portray Africans who are captured and taken away from their homeland by slave traders. Newton is played by Nick Moran

Nick Moran (born 23 December 1969) is an English actor and filmmaker. His roles include Eddie the card sharp in ''Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels'' and as List of Harry Potter characters#S 2, Scabior in ''Harry Potter and the Deathly Hall ...

.

* The 2014 film ''Freedom

Freedom is the power or right to speak, act, and change as one wants without hindrance or restraint. Freedom is often associated with liberty and autonomy in the sense of "giving oneself one's own laws".

In one definition, something is "free" i ...

'' tells the story of an American slave (Samuel Woodward, played by Cuba Gooding, Jr.) escaping to freedom via the Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was an organized network of secret routes and safe houses used by freedom seekers to escape to the abolitionist Northern United States and Eastern Canada. Enslaved Africans and African Americans escaped from slavery ...

. A parallel earlier story depicts John Newton (played by Bernhard Forcher) as the captain of a slave ship bound for America carrying Samuel's grandfather. Newton's conversion is explored as well.

* The film '' Newton's Grace'' (2017) depicts Newton's life including his early years and time as a slave himself.

Stage productions

*''African Snow'' (2007), a play by Murray Watts, takes place in the mind of John Newton. It was first produced at theYork Theatre Royal

York Theatre Royal is a theatre in St Leonard's Place, in York, England, which dates back to 1744. The theatre currently seats 750 people. Whilst the theatre is traditionally a proscenium theatre, it was reconfigured for a season in 2011 to off ...

as a co-production with Riding Lights Theatre Company

Riding Lights is a British independent theatre company which has toured shows nationally and internationally since 1977.

Based at Friargate Theatre, York since 2000, the company has staged numerous original productions such as "Science Friction" ...

, transferring to the Trafalgar Studios

Trafalgar Theatre is a West End theatre in Whitehall, near Trafalgar Square, in the City of Westminster, London. The Grade II listed building was built in 1930 with interiors in the Art Deco style as the Whitehall Theatre; it regularly staged ...

in London's West End and a National Tour. Newton was played by Roger Alborough and Olaudah Equiano

Olaudah Equiano (; c. 1745 – 31 March 1797), known for most of his life as Gustavus Vassa (), was a writer and abolitionist. According to his memoir, he was from the village of Essaka in present day southern Nigeria. Enslaved as a child in ...

by Israel Oyelumade.

*The musical ''Amazing Grace'' is a dramatisation of Newton's life. The 2014 pre-Broadway and 2015 Broadway productions starred Josh Young

Josh Young is an American actor best known for appearing on Broadway in the revival of ''Jesus Christ Superstar'' as Judas and ''Amazing Grace'', originating the role of John Newton.

Early life and education

Young was raised in a Conservative J ...

as Newton.

Television

*Newton is portrayed by actor John Castle in the British television miniseries, ''The Fight Against Slavery'' (1975).Novels

* Caryl Phillips' novel, '' Crossing the River'' (1993), includes nearly verbatim excerpts of Newton's logs from his ''Journal of a Slave Trader''. * In the chapter 'Blind, But Now I See' of the novel ''Jerusalem'' byAlan Moore

Alan Moore (born 18 November 1953) is an English author known primarily for his work in comic books including ''Watchmen'', ''V for Vendetta'', ''The Ballad of Halo Jones'', Swamp Thing (comic book), ''Swamp Thing'', ''Batman: The Killing Joke' ...

(2016), an African-American whose favourite hymn is "Amazing Grace" visits Olney where a local churchman relates the facts of Newton's life to him. He is disturbed by Newton's involvement in the slave trade. Newton's life and circumstances, and the lyrics of "Amazing Grace" are described in detail.

See also

* The Cowper and Newton Museum in Olney, BuckinghamshireReferences

Notes

Citations

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * (More legible (and machine-readable) transcription. For the facsimile edition at archive.org, seebelow

Below may refer to:

*Earth

*Ground (disambiguation)

*Soil

*Floor

* Bottom (disambiguation)

*Less than

*Temperatures below freezing

*Hell or underworld

People with the surname

* Ernst von Below (1863–1955), German World War I general

* Fred Belo ...

.)

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

Further reading

* * * * * * . Preface by Haweis * *External links

* * * Newton, John (1788)''Thoughts Upon the African Slave Trade''

(Internet Archive with funding by Associates of the Boston Public Library ed.). London: J. Buckland & J. Johnson. Retrieved 24 May 2019. (Facsimile of original book at Archive.org. For more legible (and machine-readable) transcription, see Sources (above).)

The John Newton Project

Biography & Articles on Newton

*

* ttps://www.poeticous.com/john-newton John Newton on Poeticous* {{DEFAULTSORT:Newton, John 1725 births 1807 deaths 18th-century English Anglican priests 18th-century evangelicals 18th-century Royal Navy personnel 19th-century Anglicans 19th-century English people 19th-century evangelicals Calvinist and Reformed hymnwriters Christian humanists Christian radicals Church of England hymnwriters Converts to Anglicanism Doctors of Divinity English abolitionists English evangelicals 18th-century English slave traders Evangelical Anglican hymnwriters Evangelical Anglican clergy Evangelicalism in the Church of England Military personnel from the London Borough of Tower Hamlets People from Aveley People from Wapping Royal Navy officers Royal Navy sailors Sailors from London Christian abolitionists