John Major (philosopher) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Major (or Mair; also known in

John Major (or Mair; also known in

*Alexander Broadie, "John Mair," ''The Dictionary of Literary Biography, Volume 281: British Rhetoricians and Logicians, 1500ŌĆō1660, Second Series'', Detroit: Gale, 2003, pp. 178ŌĆō187. *John Durkan, "John Major: After 400 Years," ''Innes Review'', vol. 1, 1950, pp. 131ŌĆō139. * Ricardo Garc├Ła Villoslada, "Un teologo olvidado: Juan Mair", Estudios eclesi├Īsticos 15 (1936), 83ŌĆō118; * Ricardo Garc├Ła Villoslada, La Universidad de Par├Łs durante los estudios de Francisco de Vitoria (1507ŌĆō1522) (Roma, 1938), 127ŌĆō164; * J.H. Burns, "New Light on John Major", Innes Review 5 (1954), 83ŌĆō100; * T.F. Torrance, "La philosophie et la th├®ologie de Jean Mair ou Major, de Haddington (1469ŌĆō1550)", Archives de philosophie 32 (1969), 531ŌĆō576; * Mauricio Beuchot, "El primer planteamiento teologico-politico-juridico sobre la conquista de Am├®rica: John Mair", La ciencia tomista 103 (1976), 213ŌĆō230; * Jo├½l Biard, "La logique de l'infini chez Jean Mair", Les Etudes philosophiques 1986, 329ŌĆō348; & Jo├½l Biard, "La toute-puissance divine dans le Commentaire des Sentences de Jean Mair", in Potentia Dei. L'onnipotenza divina nel pensiero dei secoli XVI e XVII, ed. Guido Canziani / Miguel A. Granada / Yves Charles Zarka (Milano, 2000), 25ŌĆō41. * John T. Slotemaker and Jeffrey C. Witt (2015), edd., ''A Companion to the Theology of John Mair'', Boston: Brill.

Significant Scots - John Mair

*

Major, John

- Scholasticon.fr - a database on Medieval scholars {{DEFAULTSORT:Major, John 1467 births 1550 deaths 15th-century philosophers Alumni of Christ's College, Cambridge Catholic philosophers People from East Lothian People from Haddington, East Lothian Scholastic philosophers Latin commentators on Aristotle 16th-century Scottish philosophers British Christian theologians Principals of the University of Glasgow University of Paris alumni Academics of the University of St Andrews Academic staff of the University of Paris 15th-century Scottish writers 16th-century Scottish historians 16th-century Scottish male writers 16th-century writers in Latin Scottish writers in Latin

John Major (or Mair; also known in

John Major (or Mair; also known in Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

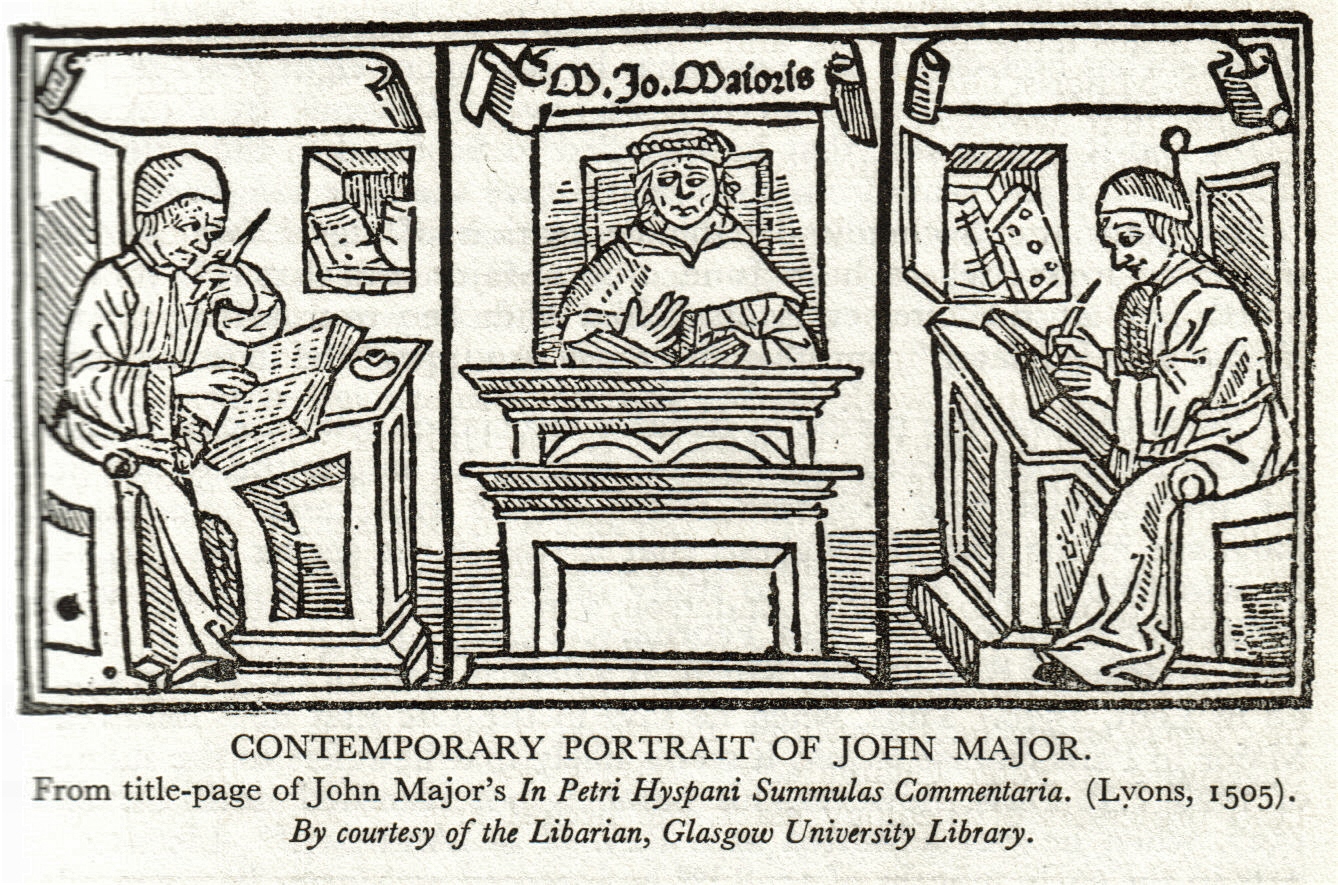

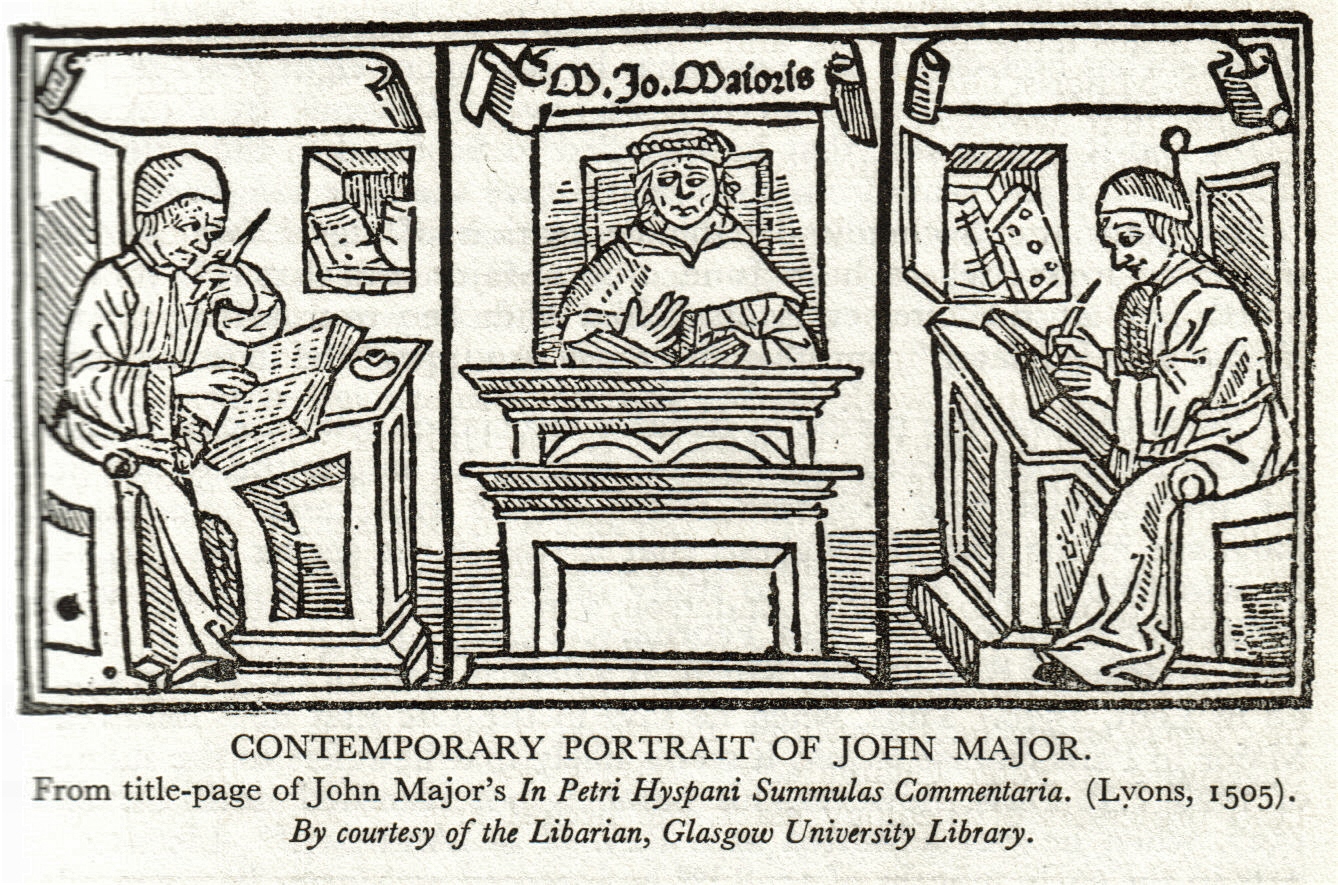

as ''Joannes Majoris'' and ''Haddingtonus Scotus''; 1467ŌĆō1550) was a Scottish philosopher, theologian, and historian who was much admired in his day and was an acknowledged influence on all the great thinkers of the time. A renowned teacher, his works were much collected and frequently republished across Europe. His "sane conservatism" and his sceptical, logical

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the study of deductively valid inferences or logical truths. It examines how conclusions follow from premises based on the structure of arg ...

approach to the study of texts such as Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384ŌĆō322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

or the Bible

The Bible is a collection of religious texts that are central to Christianity and Judaism, and esteemed in other Abrahamic religions such as Islam. The Bible is an anthology (a compilation of texts of a variety of forms) originally writt ...

were less prized in the subsequent age of humanism

Humanism is a philosophy, philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential, and Agency (philosophy), agency of human beings, whom it considers the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The me ...

, when a more committed and linguistic/literary approach prevailed.

His influence in logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the study of deductively valid inferences or logical truths. It examines how conclusions follow from premises based on the structure o ...

(especially the analysis of terms), science ( impetus and infinitesimals

In mathematics, an infinitesimal number is a non-zero quantity that is closer to 0 than any non-zero real number is. The word ''infinitesimal'' comes from a 17th-century Modern Latin coinage ''infinitesimus'', which originally referred to the " ...

), politics (placing the people over kings), Church (councils over Popes), and international law

International law, also known as public international law and the law of nations, is the set of Rule of law, rules, norms, Customary law, legal customs and standards that State (polity), states and other actors feel an obligation to, and generall ...

(establishing the human rights of "savages" conquered by the Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many countries in the Americas

**Spanish cuisine

**Spanish history

**Spanish culture

...

) can be traced across the centuries and appear decidedly modern, and it is only in the modern age that he is not routinely dismissed as a scholastic. His Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

style did not help ŌĆō he thought that "it is of more moment to understand aright, and clearly to lay down the truth of any matter than to use eloquent language". Nevertheless, it is to his writings, including their dedications, that we owe much of our knowledge of the everyday facts of Major's life ŌĆō for example his "shortness of stature". He was an extremely curious and very observant man, and used his experiences ŌĆō of earthquakes in Paisley, thunder in Glasgow

Glasgow is the Cities of Scotland, most populous city in Scotland, located on the banks of the River Clyde in Strathclyde, west central Scotland. It is the List of cities in the United Kingdom, third-most-populous city in the United Kingdom ...

, storms at sea, eating oatcakes in northern England ŌĆō to illustrate the more abstract parts of his logical writings.

Life

School

John Major (or 'Mair') was born about 1467 at Gleghornie, East Lothian nearNorth Berwick

North Berwick (; ) is a seaside resort, seaside town and former royal burgh in East Lothian, Scotland. It is situated on the south shore of the Firth of Forth, approximately east-northeast of Edinburgh. North Berwick became a fashionable holi ...

where he received his early education. It was at nearby Haddington, East Lothian, Scotland, where he attended grammar school

A grammar school is one of several different types of school in the history of education in the United Kingdom and other English-speaking countries, originally a Latin school, school teaching Latin, but more recently an academically oriented Se ...

. He was probably taught by the town schoolmaster, who was, according to Major "although a circumspect man in other ways, more severe than was just in beating boys". If it had not been for the influence of his mother, Major says he would have left, but he and his brother stayed on and were successful. According to him, Haddington was "the town which fostered the beginning of my studies, and in whose kindly embrace I was nourished as a novice with the sweetest milk of the art of grammar". He says he stayed in Haddington "to a pretty advanced age" and he remembers the sound of the King James III's bombardment of the nearby castle

A castle is a type of fortification, fortified structure built during the Middle Ages predominantly by the nobility or royalty and by Military order (monastic society), military orders. Scholars usually consider a ''castle'' to be the private ...

of Dunbar

Dunbar () is a town on the North Sea coast in East Lothian in the south-east of Scotland, approximately east of Edinburgh and from the AngloŌĆōScottish border, English border north of Berwick-upon-Tweed.

Dunbar is a former royal burgh, and ...

, which was in 1479. He also remembers the comet which was supposed to have foretold the King's defeat at Sauchieburn which was in 1488.

However, it was in 1490, he reports, that he "first left the paternal hearth". In 1490, probably under the influence of Robert Cockburn, another Haddington man, destined to be an influential bishop (of Ross and later of Dunkeld

Dunkeld (, , from , "fort of the Caledonians") is a town in Perth and Kinross, Scotland. The location of a historic cathedral, it lies on the north bank of the River Tay, opposite Birnam. Dunkeld lies close to the geological Highland Boundar ...

), he decided to go to Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

to study among the great numbers of Scots there at the time.

University

It is not known whether he attended university in Scotland as a student ŌĆō there are no matriculation records of him and he claimed never to have seen the university town ofSt Andrews

St Andrews (; ; , pronounced ╩░╩▓╔¬╩Ä╦łr╦Āi╦É.╔¬╔▓ is a town on the east coast of Fife in Scotland, southeast of Dundee and northeast of Edinburgh. St Andrews had a recorded population of 16,800 , making it Fife's fourth-largest settleme ...

, Fife as a young man (though he did complain later of its bad beer). He seems to have decided to prepare for Paris at Cambridge

Cambridge ( ) is a List of cities in the United Kingdom, city and non-metropolitan district in the county of Cambridgeshire, England. It is the county town of Cambridgeshire and is located on the River Cam, north of London. As of the 2021 Unit ...

in England. He says that in 1492 he attended "Gods House", which later became Christ's College. He remembers the bells ŌĆō "on great feast days, I spent half the night listening to them" ŌĆō but was obviously well-prepared, as he left for Paris after three terms.

In 1493 he matriculated in the University of Paris

The University of Paris (), known Metonymy, metonymically as the Sorbonne (), was the leading university in Paris, France, from 1150 to 1970, except for 1793ŌĆō1806 during the French Revolution. Emerging around 1150 as a corporation associated wit ...

, France, then the foremost university in Europe. He studied at the Coll├©ge Sainte-Barbe

The Coll├©ge Sainte-Barbe () is a former college in the 5th arrondissement of Paris, France.

The Coll├©ge Sainte-Barbe was founded in 1460 on Montagne Sainte-Genevi├©ve ( Latin Quarter, Paris). It was until its closure in June 1999 the "oldest ...

and took his Bachelor of Arts degree there in 1495 followed by his master's degree in 1496. There were many currents of thought in Paris but he was heavily influenced, as were fellow Scots such as Lawrence of Lindores by the nominalist

In metaphysics, nominalism is the view that universals and abstract objects do not actually exist other than being merely names or labels. There are two main versions of nominalism. One denies the existence of universalsŌĆöthat which can be inst ...

and empiricist

In philosophy, empiricism is an epistemological view which holds that true knowledge or justification comes only or primarily from sensory experience and empirical evidence. It is one of several competing views within epistemology, along ...

approach of John Buridan

Jean Buridan (; ; Latin: ''Johannes Buridanus''; ŌĆō ) was an influential 14thcentury French scholastic philosopher.

Buridan taught in the faculty of arts at the University of Paris for his entire career and focused in particular on logic and ...

. (The latter's influence on Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (19 February 1473 ŌĆō 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath who formulated a mathematical model, model of Celestial spheres#Renaissance, the universe that placed heliocentrism, the Sun rather than Earth at its cen ...

and Galileo

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 ŌĆō 8 January 1642), commonly referred to as Galileo Galilei ( , , ) or mononymously as Galileo, was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a poly ...

can be traced through Major's published works). He became a student master ('regent') in Arts in the Coll├©ge de Montaigu

The Coll├©ge de Montaigu was one of the constituent colleges of the Faculty of Arts of the University of Paris.

History

The college, originally called Coll├©ge des Aicelins, was founded in 1314 by Gilles I Aycelin de Montaigu, Archbishop of Na ...

in 1496 and began the study of theology under the formidable Jan Standonck. He consorted with scholars of later renown, some from his hometown, Robert Walterston, and his home country ( David Cranston of Glasgow

Glasgow is the Cities of Scotland, most populous city in Scotland, located on the banks of the River Clyde in Strathclyde, west central Scotland. It is the List of cities in the United Kingdom, third-most-populous city in the United Kingdom ...

, who died in 1512), but mostly they were the luminaries of the age, including Erasmus

Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus ( ; ; 28 October c. 1466 ŌĆō 12 July 1536), commonly known in English as Erasmus of Rotterdam or simply Erasmus, was a Dutch Christian humanist, Catholic priest and Catholic theology, theologian, educationalist ...

, whose reforming enthusiasms he shared, Rabelais and Reginald Pole

Reginald Pole (12 March 1500 ŌĆō 17 November 1558) was an English cardinal and the last Catholic Archbishop of Canterbury, holding the office from 1556 to 1558 during the Marian Restoration of Catholicism.

Early life

Pole was born at Stourt ...

. In the winter of 1497 he had a serious illness, from which he never completely recovered. He had never had dreams before, but ever afterwards he was troubled by dreams, migraine

Migraine (, ) is a complex neurological disorder characterized by episodes of moderate-to-severe headache, most often unilateral and generally associated with nausea, and light and sound sensitivity. Other characterizing symptoms may includ ...

, colic

Colic or cholic () is a form of pain that starts and stops abruptly. It occurs due to muscular contractions of a hollow tube (small and large intestine, gall bladder, ureter, etc.) in an attempt to relieve an obstruction by forcing content ou ...

and "excessive sleepiness" (he was always hard to awaken). In 1499, he moved to the College of Navarre. In 1501, he received his degree of Bachelor of Sacred Theology

The Bachelor of Sacred Theology (abbreviated STB) is the first of three ecclesiastical degrees in theology (the second being the Licentiate in Sacred Theology and the third being the Doctorate in Sacred Theology) which are conferred by a number o ...

and in 1505 his logical writings were collected and published for the first time. In 1506 he was licensed to teach theology and was awarded the degree of Doctor of Sacred Theology

The Doctor of Sacred Theology (, abbreviated STD), also sometimes known as Professor of Sacred Theology (, abbreviated STP), is the final theological degree in the pontifical university system of the Catholic Church, being the ecclesiastical equ ...

on 11 November that year (coming 3rd in the listings). He taught at the Coll├©ge de Montaigu

The Coll├©ge de Montaigu was one of the constituent colleges of the Faculty of Arts of the University of Paris.

History

The college, originally called Coll├©ge des Aicelins, was founded in 1314 by Gilles I Aycelin de Montaigu, Archbishop of Na ...

(where he was, temporarily joint Director) and also the prestigious Sorbonne, where he served on many commissions.

Later career

In 1510 he discussed the moral and legal questions arising from theSpanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

**Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many countries in the Americas

**Spanish cuisine

**Spanish history

**Spanish culture

...

discovery of America

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

. He claimed that the natives had political and property rights that could not be invaded, at least not without compensation. He also uses the new discoveries to argue for the possibility of innovation in all knowledge saying "Has not Amerigo Vespucci

Amerigo Vespucci ( , ; 9 March 1454 ŌĆō 22 February 1512) was an Italians, Italian explorer and navigator from the Republic of Florence for whom "Naming of the Americas, America" is named.

Vespucci participated in at least two voyages of the A ...

discovered lands unknown to Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; , ; ; ŌĆō 160s/170s AD) was a Greco-Roman mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were important to later Byzantine science, Byzant ...

, Pliny and other geographers up to the present? Why cannot the same happen in other spheres?" At the same time, he was impatient of humanist

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential, and agency of human beings, whom it considers the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "humanism" ha ...

criticism of the logical analysis of texts (including the Bible). "...these questions which the humanists

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential, and agency of human beings, whom it considers the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "humanism" has ...

think futile, are like a ladder for the intelligence to rise towards the Bible" (which he elsewhere, perhaps unwisely called "the easier parts of theology"). Nevertheless, in 1512, like a good humanist

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential, and agency of human beings, whom it considers the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "humanism" ha ...

, he learned Greek from Girolamo Aleandro (who re-introduced the study of Greek to Paris) who wrote "Many scholastics are to be found in France who are keen students in different kinds of knowledge and several of these are among my faithful hearers, such as John Mair, Doctor of Philosophy..."

In 1518 he returned to Scotland to become Principal of the University of Glasgow

The Principal of the University of Glasgow is the working head of the University of Glasgow, University, acting as its chief executive. He is responsible for the day-to-day management of the university as well as its strategic planning and admin ...

(and also canon

Canon or Canons may refer to:

Arts and entertainment

* Canon (fiction), the material accepted as officially written by an author or an ascribed author

* Literary canon, an accepted body of works considered as high culture

** Western canon, th ...

of the cathedral, vicar

A vicar (; Latin: '' vicarius'') is a representative, deputy or substitute; anyone acting "in the person of" or agent for a superior (compare "vicarious" in the sense of "at second hand"). Linguistically, ''vicar'' is cognate with the English p ...

of Dunlop and Treasurer of the Chapel Royal). He returned to Paris several times ŌĆō by sea one time, getting delayed in Dieppe for three weeks by a storm; and by land another time, having dinner en route through England with his friend, Cardinal Wolsey

Thomas Wolsey ( ; ŌĆō 29 November 1530) was an English statesman and Catholic cardinal. When Henry VIII became King of England in 1509, Wolsey became the king's almoner. Wolsey's affairs prospered and by 1514 he had become the controlling f ...

. He offered Major a post, which he declined, in his new college at the University of Oxford

The University of Oxford is a collegiate university, collegiate research university in Oxford, England. There is evidence of teaching as early as 1096, making it the oldest university in the English-speaking world and the List of oldest un ...

, to be called Cardinal's College, (later Christ Church, Oxford

Christ Church (, the temple or house, ''wikt:aedes, ├”des'', of Christ, and thus sometimes known as "The House") is a Colleges of the University of Oxford, constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. Founded in 1546 by Henry V ...

). In 1528, King Francis I of France

Francis I (; ; 12 September 1494 ŌĆō 31 March 1547) was King of France from 1515 until his death in 1547. He was the son of Charles, Count of Angoul├¬me, and Louise of Savoy. He succeeded his first cousin once removed and father-in-law Louis&nbs ...

issued Major with a patent of naturalisation, making him a naturalised subject of France.

In 1533 he was made Provost of St Salvator's College in the University of St Andrews

The University of St Andrews (, ; abbreviated as St And in post-nominals) is a public university in St Andrews, Scotland. It is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, oldest of the four ancient universities of Scotland and, f ...

ŌĆō to which thronged many of the most significant men in Scotland, including John Knox

John Knox ( ŌĆō 24 November 1572) was a Scottish minister, Reformed theologian, and writer who was a leader of the country's Reformation. He was the founder of the Church of Scotland.

Born in Giffordgate, a street in Haddington, East Lot ...

and George Buchanan

George Buchanan (; February 1506 ŌĆō 28 September 1582) was a Scottish historian and humanist scholar. According to historian Keith Brown, Buchanan was "the most profound intellectual sixteenth-century Scotland produced." His ideology of re ...

. He missed Paris ŌĆō "When I was in Scotland, I often thought how I would go back to Paris and give lectures as I used to and hear disputations". He died in 1550 (perhaps on 1 May), his works read throughout Europe, his name honoured everywhere, just as the storms of the Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major Theology, theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the p ...

were about to sweep away, at least in his own country, any respect for his centuries-old methodology.

Some publications by John Major

* Heinrich Totting von Oytha's abbreviation ofAdam de Wodeham

Adam of Wodeham, OFM (1298ŌĆō1358) was a philosopher and theologian. Currently, Wodeham is best known for having been a secretary of William Ockham and for his interpretations of John Duns Scotus. But Wodeham was also an influential thinker in h ...

's Oxford Lectures, edited by Major, Paris 1512.

*''Lectures in logic'' (Lyons 1516)

*''Reportata Parisiensia by Duns Scotus'' co-edited by Major, Paris 1517ŌĆō18

*Commentary on the Sentences of Peter Lombard (''In Libros Sententiarum primum et secundum commentarium'') Paris 1519

*History of Greater Britain (''Historia majoris Britanniae, tam Angliae quam Scotiae'') Paris 1521

*''Commentary on Aristotle's physical and ethical writings'' Paris 1526

*''Quaestiones logicales'' Paris 1528

*''Commentary on the Four Gospels'' Paris 1528

*''Disputationes de Potestate Papae et Concilii'' (Paris)

*''Commentary on Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics

The ''Nicomachean Ethics'' (; , ) is Aristotle's best-known work on ethics: the science of the good for human life, that which is the goal or end at which all our actions aim. () It consists of ten sections, referred to as books, and is closely ...

'' (his last book)

Influence

Historians

His ''De Gestis Scotorum'' (Paris, 1521) was partly a patriotic attempt to raise the profile of his native country, but was also an attempt to clear away myth and fable, basing his history on evidence. In this, he was following in the footsteps of his predecessor, theChronicler

A chronicle (, from Greek ''chronik├Ī'', from , ''chr├│nos'' ŌĆō "time") is a historical account of events arranged in chronological order, as in a timeline. Typically, equal weight is given for historically important events and local events, ...

Andrew of Wyntoun, though writing in Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

for a European audience as opposed to the Scots Andrew wrote for his aristocratic Scots patrons. Although the documentary evidence available to Major was limited, his scholarly approach was adopted and improved by later historians of Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

, including his pupil Hector Boece

Hector Boece (; also spelled Boyce or Boise; 1465ŌĆō1536), known in Latin as Hector Boecius or Boethius, was a Scottish philosopher and historian, and the first Ancient university governance in Scotland, Principal of King's College, Aberdeen, ...

, and John Lesley

John Lesley (or Leslie) (29 September 1527 ŌĆō 31 May 1596) was a Scottish Roman Catholic bishop and historian. His father was Gavin Lesley, rector of Kingussie, Badenoch.

Early career

He was educated at the University of Aberdeen, where he ...

.

Calvin and Loyola

In 1506 he was awarded a doctorate in theology by Paris where he began to teach and progress through the hierarchy, becoming for a brief period Rector. (Some 18 of his fellow Scots had held or were to hold this prestigious position). He was a renownedlogician

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the study of deductively valid inferences or logical truths. It examines how conclusions follow from premises based on the structure of arg ...

and philosopher. He is reported to have been a very clear and forceful lecturer, attracting students from all over Europe. In contrast, he had a rather dry, some said 'barbaric', written Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

style. He was referred to by Pierre Bayle

Pierre Bayle (; 18 November 1647 ŌĆō 28 December 1706) was a French philosopher, author, and lexicographer. He is best known for his '' Historical and Critical Dictionary'', whose publication began in 1697. Many of the more controversial ideas ...

as writing "''in stylo Sorbonico''", not meaning this as a compliment. His interests ranged across the burning issues of the day. His approach largely followed Nominalism

In metaphysics, nominalism is the view that universals and abstract objects do not actually exist other than being merely names or labels. There are two main versions of nominalism. One denies the existence of universalsŌĆöthat which can be inst ...

which was in tune with the growing emphasis on the absolutely unconstrained nature of God, which in turn emphasised his grace and the importance of individual belief and submission. His humanist

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential, and agency of human beings, whom it considers the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "humanism" ha ...

approach was in tune with the return to the texts in the original languages of the Scriptures and classical authors. He emphasised that authority lay with the whole church and not with the Pope. Similarly, he asserted that authority in a kingdom lay not with the king but with the people, who could retake their power from a delinquent king (a striking echo of the ringing Declaration of Arbroath 1320 confirming to the Pope the independence of the Scottish crown from that of England). It is not surprising that he emphasised the natural freedom of human beings.

His influence extended through enthusiastic pupils to the leading thinkers of the day but most obviously to a group of Spanish thinkers, including Antonio Coronel, who taught John Calvin

John Calvin (; ; ; 10 July 150927 May 1564) was a French Christian theology, theologian, pastor and Protestant Reformers, reformer in Geneva during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system of C ...

and very probably Ignatius of Loyola

Ignatius of Loyola ( ; ; ; ; born ├Ź├▒igo L├│pez de O├▒az y Loyola; ŌĆō 31 July 1556), venerated as Saint Ignatius of Loyola, was a Basque Spaniard Catholic priest and theologian, who, with six companions, founded the religious order of the S ...

.

In 1522, at Salamanca

Salamanca () is a Municipality of Spain, municipality and city in Spain, capital of the Province of Salamanca, province of the same name, located in the autonomous community of Castile and Le├│n. It is located in the Campo Charro comarca, in the ...

, Domingo de San Juan referred to him as "''the revered master, John Mair, a man celebrated the world over''". The Salamanca school of (largely Thomist

Thomism is the philosophical and theological school which arose as a legacy of the work and thought of Thomas Aquinas (1225ŌĆō1274), the Dominican philosopher, theologian, and Doctor of the Church.

In philosophy, Thomas's disputed questions ...

) philosophers was a brilliant flowering of thought until the early parts of the seventeenth century. It included Francisco de Vitoria

Francisco de Vitoria ( ŌĆō 12 August 1546; also known as Francisco de Victoria) was a Spanish Roman Catholic philosopher, theologian, and jurist of Renaissance Spain. He is the founder of the tradition in philosophy known as the School of Sala ...

, Cano, de Domingo de Soto and Bartolom├® de Medina, each one thorough soaked in Mairian enthusiasms.

Knox

Major wrote in his ''Commentary on the Sentences ofPeter Lombard

Peter Lombard (also Peter the Lombard, Pierre Lombard or Petrus Lombardus; 1096 ŌĆō 21/22 August 1160) was an Italian scholasticism, scholastic theologian, Bishop of Paris, and author of ''Sentences, Four Books of Sentences'' which became the s ...

'' ''"Our native soil attracts us with a secret and inexpressible sweetness and does not permit us to forget it".'' He returned to Scotland in 1518. Given his success and experience in Paris, it is no surprise that he became the Principal of the University of Glasgow

The University of Glasgow (abbreviated as ''Glas.'' in Post-nominal letters, post-nominals; ) is a Public university, public research university in Glasgow, Scotland. Founded by papal bull in , it is the List of oldest universities in continuous ...

. In 1523 left for the University of St Andrews

The University of St Andrews (, ; abbreviated as St And in post-nominals) is a public university in St Andrews, Scotland. It is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, oldest of the four ancient universities of Scotland and, f ...

where he was assessor to the Dean of Arts. In 1525 he went again to Paris from where he returned in 1531 eventually to become Provost of St Salvator's College, St Andrews until his death in 1550, aged about eighty three.

One of his most notable students was John Knox

John Knox ( ŌĆō 24 November 1572) was a Scottish minister, Reformed theologian, and writer who was a leader of the country's Reformation. He was the founder of the Church of Scotland.

Born in Giffordgate, a street in Haddington, East Lot ...

(coincidentally, another native of Haddington) who said of Major that he was such as "''whose work was then held as an oracle on the matters of religion''" If this is not exactly a ringing endorsement, it is not hard to see in Knox's preaching an intense version of Major's enthusiasms ŌĆō the utter freedom of God, the importance of the Bible, scepticism of earthly authority. It might be more surprising that Major preferred to follow his friend Erasmus

Desiderius Erasmus Roterodamus ( ; ; 28 October c. 1466 ŌĆō 12 July 1536), commonly known in English as Erasmus of Rotterdam or simply Erasmus, was a Dutch Christian humanist, Catholic priest and Catholic theology, theologian, educationalist ...

's example and remain within the Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

(though he did envisage a national church for Scotland). Major also filled with enthusiasm other Scottish Reformers including the Protestant martyr Patrick Hamilton and the Latin stylist George Buchanan

George Buchanan (; February 1506 ŌĆō 28 September 1582) was a Scottish historian and humanist scholar. According to historian Keith Brown, Buchanan was "the most profound intellectual sixteenth-century Scotland produced." His ideology of re ...

, whose enthusiasm for witty Latinisms had him waspishly suggesting that the only thing major about his ex-teacher was his surname ŌĆō typical Renaissance disdain for the Schoolmen

Scholasticism was a medieval European philosophical movement or methodology that was the predominant education in Europe from about 1100 to 1700. It is known for employing logically precise analyses and reconciling classical philosophy and C ...

.

Empiricism

Major and his circle were interested in the structures oflanguage

Language is a structured system of communication that consists of grammar and vocabulary. It is the primary means by which humans convey meaning, both in spoken and signed language, signed forms, and may also be conveyed through writing syste ...

ŌĆō spoken, written and 'mental'. This latter was the language which underlies the thoughts that are expressed in natural languages, like Scots, English or Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

. He attacks a whole range of questions from a generally 'nominalist' perspective ŌĆō a form of philosophical discourse whose tradition derives from the high Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

and was to continue into that of the Scottish and other European empiricists

In philosophy, empiricism is an epistemological view which holds that true knowledge or justification comes only or primarily from sensory experience and empirical evidence. It is one of several competing views within epistemology, along ...

. According to Alexander Broadie, Major's influence on this latter tradition reached as far as the 18th and 19th century Scottish School of Common Sense initiated by Thomas Reid

Thomas Reid (; 7 May (Julian calendar, O.S. 26 April) 1710 ŌĆō 7 October 1796) was a religiously trained Scotland, Scottish philosophy, philosopher best known for his philosophical method, his #Thomas_Reid's_theory_of_common_sense, theory of ...

. The highly logical and technical approach of Medieval philosophy

Medieval philosophy is the philosophy that existed through the Middle Ages, the period roughly extending from the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century until after the Renaissance in the 13th and 14th centuries. Medieval philosophy, ...

ŌĆō perhaps added to by Major's poor written style as well as his adherence to the Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

party at the time of the Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major Theology, theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the p ...

ŌĆō explain in some part why this influence is still somewhat occluded.

Human rights

More obviously influential was hismoral philosophy

Ethics is the philosophical study of moral phenomena. Also called moral philosophy, it investigates normative questions about what people ought to do or which behavior is morally right. Its main branches include normative ethics, applied et ...

, not primarily because of his casuistry

Casuistry ( ) is a process of reasoning that seeks to resolve moral problems by extracting or extending abstract rules from a particular case, and reapplying those rules to new instances. This method occurs in applied ethics and jurisprudence. ...

ŌĆō an approach acknowledging the complexity of individual cases. This was later so strong in Jesuit

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

teaching, possibly related to the Major's renown in Spain mentioned above. His legal views were also influential. His Commentaries on the Sentences

The ''Sentences'' (. ) is a compendium of Christian theology written by Peter Lombard around 1150. It was the most important religious textbook of the Middle Ages.

Background

The sentence genre emerged from works like Prosper of Aquitaine's ...

of Peter Lombard

Peter Lombard (also Peter the Lombard, Pierre Lombard or Petrus Lombardus; 1096 ŌĆō 21/22 August 1160) was an Italian scholasticism, scholastic theologian, Bishop of Paris, and author of ''Sentences, Four Books of Sentences'' which became the s ...

was most certainly studied and quoted in the debates at Burgos

Burgos () is a city in Spain located in the autonomous community of Castile and Le├│n. It is the capital and most populous municipality of the province of Burgos.

Burgos is situated in the north of the Iberian Peninsula, on the confluence of th ...

in 1512, by Fr├Āy Anton Montesino, a graduate of Salamanca

Salamanca () is a Municipality of Spain, municipality and city in Spain, capital of the Province of Salamanca, province of the same name, located in the autonomous community of Castile and Le├│n. It is located in the Campo Charro comarca, in the ...

. This "''debate unique in the history of empires''", as Hugh Thomas calls it, resulted in the recognition in Spanish law of the indigenous populations of America

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

as being free human beings

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') or modern humans are the most common and widespread species of primate, and the last surviving species of the genus ''Homo''. They are great apes characterized by their hairlessness, bipedalism, and high intellige ...

with all the rights (to liberty and property, for example) attached to them. This pronouncement was hedged in with many subtle qualifications, and the Spanish crown

The monarchy of Spain or Spanish monarchy () is the constitutional form of government of Spain. It consists of a Hereditary monarchy, hereditary monarch who reigns as the head of state, being the highest office of the country.

The Spanish ...

was never efficient at enforcing it, but it can be regarded as the fount of human rights law

International human rights law (IHRL) is the body of international law designed to promote human rights on social, regional, and domestic levels. As a form of international law, international human rights law is primarily made up of treaties, ag ...

.Mauricio Beuchot; "El primer planteamiento teologico-politico-juridico sobre la conquista de Am├®rica: John Mair", La ciencia tomista 103 (1976), 213ŌĆō230;

See also

*Jean Buridan

Jean Buridan (; ; Latin: ''Johannes Buridanus''; ŌĆō ) was an influential 14thcentury French scholastic philosopher.

Buridan taught in the faculty of arts at the University of Paris for his entire career and focused in particular on logic and ...

* John Cantius

* Empiricism

In philosophy, empiricism is an epistemological view which holds that true knowledge or justification comes only or primarily from sensory experience and empirical evidence. It is one of several competing views within epistemology, along ...

* Henry of Oyta

* Scottish School of Common Sense

* Thomas Reid

Thomas Reid (; 7 May (Julian calendar, O.S. 26 April) 1710 ŌĆō 7 October 1796) was a religiously trained Scotland, Scottish philosophy, philosopher best known for his philosophical method, his #Thomas_Reid's_theory_of_common_sense, theory of ...

* Adam de Wodeham

Adam of Wodeham, OFM (1298ŌĆō1358) was a philosopher and theologian. Currently, Wodeham is best known for having been a secretary of William Ockham and for his interpretations of John Duns Scotus. But Wodeham was also an influential thinker in h ...

* David Cranston (philosopher)

Notes

References

* Broadie, A '' The Circle of John Mair: Logic and Logicians in Pre-Reformation Scotland'', Oxford 1985 * Broadie, A ''The Tradition of Scottish Philosophy'' Edinburgh 1990 Polygon * ''A Companion to the Theology of John Mair'', ed. John T. Slotemaker, Leiden: Brill, 2015. * ''Conciliarism and Papalism'', ed. J. H. Burns and Thomas M. Izbicki, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997. (Includes Mair's defense of conciliar supremacy.) * Durkan, J "New light on John Mair", ''Innes Review'', Edinburgh, Vol, IV, 1954 * Major, John ''A history of Greater Britain, as well England as Scotland; translated from the original Latin and edited with notes by Archibald Constable, to which is prefixed a life of the author by Aeneas J.G. Mackay''. Edinburgh University Press for the Scottish History Society, (1892). * Renaudet, Augustin, ''Pr├®r├®forme et Humanisme ├Ā Paris pendant les premi├©res guerres d'Italie (1494-1516) Biblioth├©que de l'Institut fran├¦ais de Florence (Universit├® de Grenobles 1st series Volume VI) ├ēdouard Champion Paris 1916 * Thomas, H ''Rivers of Gold: the Rise of the Spanish Empire'' London 2003 Weidenfeld and NicolsonFurther reading

* " Heinrich Totting von Oyta" (in German) * Wallace, W A ''Prelude to Galileo ŌĆō essays on medieval and sixteenth-century sources of Galileo's thought''. (Page 64 et seq) Springer Science and Business Dordrecht, Holland 198*Alexander Broadie, "John Mair," ''The Dictionary of Literary Biography, Volume 281: British Rhetoricians and Logicians, 1500ŌĆō1660, Second Series'', Detroit: Gale, 2003, pp. 178ŌĆō187. *John Durkan, "John Major: After 400 Years," ''Innes Review'', vol. 1, 1950, pp. 131ŌĆō139. * Ricardo Garc├Ła Villoslada, "Un teologo olvidado: Juan Mair", Estudios eclesi├Īsticos 15 (1936), 83ŌĆō118; * Ricardo Garc├Ła Villoslada, La Universidad de Par├Łs durante los estudios de Francisco de Vitoria (1507ŌĆō1522) (Roma, 1938), 127ŌĆō164; * J.H. Burns, "New Light on John Major", Innes Review 5 (1954), 83ŌĆō100; * T.F. Torrance, "La philosophie et la th├®ologie de Jean Mair ou Major, de Haddington (1469ŌĆō1550)", Archives de philosophie 32 (1969), 531ŌĆō576; * Mauricio Beuchot, "El primer planteamiento teologico-politico-juridico sobre la conquista de Am├®rica: John Mair", La ciencia tomista 103 (1976), 213ŌĆō230; * Jo├½l Biard, "La logique de l'infini chez Jean Mair", Les Etudes philosophiques 1986, 329ŌĆō348; & Jo├½l Biard, "La toute-puissance divine dans le Commentaire des Sentences de Jean Mair", in Potentia Dei. L'onnipotenza divina nel pensiero dei secoli XVI e XVII, ed. Guido Canziani / Miguel A. Granada / Yves Charles Zarka (Milano, 2000), 25ŌĆō41. * John T. Slotemaker and Jeffrey C. Witt (2015), edd., ''A Companion to the Theology of John Mair'', Boston: Brill.

External links

* A site with an extensive bibliography of primary and secondary sourceSignificant Scots - John Mair

*

Major, John

- Scholasticon.fr - a database on Medieval scholars {{DEFAULTSORT:Major, John 1467 births 1550 deaths 15th-century philosophers Alumni of Christ's College, Cambridge Catholic philosophers People from East Lothian People from Haddington, East Lothian Scholastic philosophers Latin commentators on Aristotle 16th-century Scottish philosophers British Christian theologians Principals of the University of Glasgow University of Paris alumni Academics of the University of St Andrews Academic staff of the University of Paris 15th-century Scottish writers 16th-century Scottish historians 16th-century Scottish male writers 16th-century writers in Latin Scottish writers in Latin