John Latham (judge) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

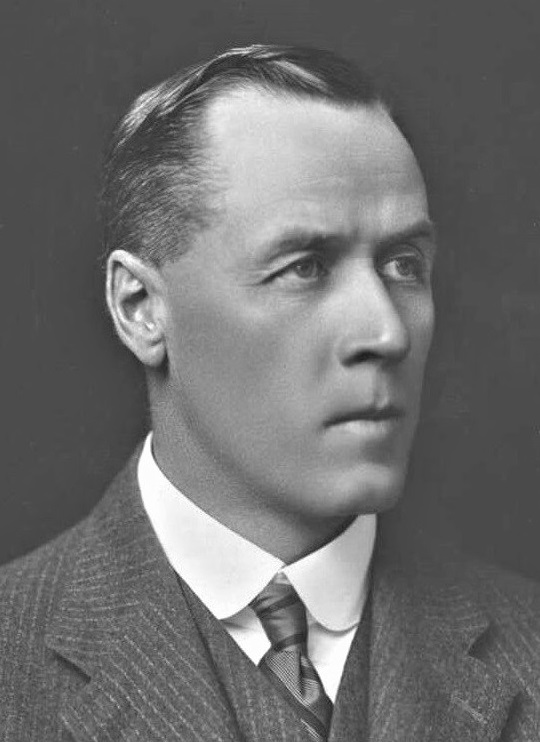

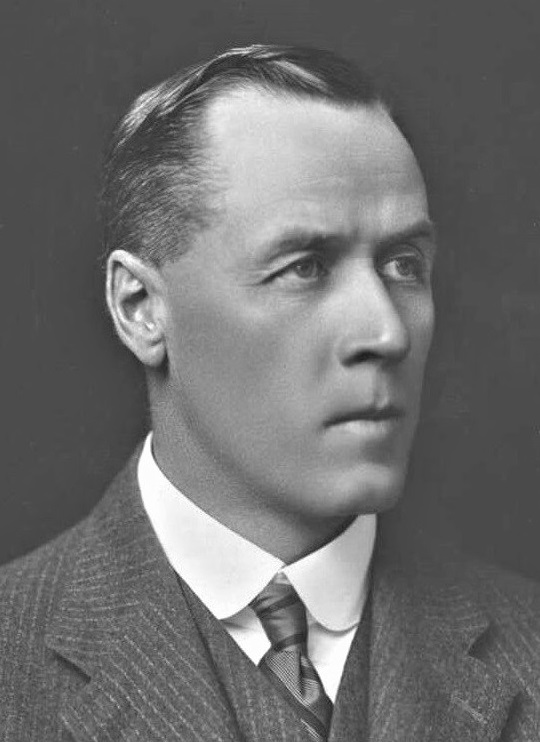

Sir John Greig Latham (26 August 1877 – 25 July 1964) was an Australian lawyer, politician, and judge who served as the fifth

Latham had a distinguished career as a

Latham had a distinguished career as a

The UAP won a huge victory in the 1931 election, and Latham was appointed Attorney-General once again. He also served as Minister for External Affairs and (unofficially) the

The UAP won a huge victory in the 1931 election, and Latham was appointed Attorney-General once again. He also served as Minister for External Affairs and (unofficially) the

Latham was appointed Chief Justice of the

Latham was appointed Chief Justice of the

He was a prominent rationalist and atheist, after abandoning his parents' Methodism at university. It was at this time that he ended his engagement to Elizabeth (Bessie) Moore, the daughter of Methodist Minister Henry Moore. Bessie later married Edwin P. Carter on 18 May 1911 at the Northcote Methodist Church, High Street, Northcote.

In 1907, Latham married schoolteacher Ella Tobin. They had three children, two of whom predeceased him. His wife, Ella, also predeceased him. Latham died in 1964 in the Melbourne suburb of Richmond.

He was also a prominent campaigner for Australian literature, being part of the editorial board of ''The Trident'', a small liberal journal, which was edited by Walter Murdoch. The board also included poet

He was a prominent rationalist and atheist, after abandoning his parents' Methodism at university. It was at this time that he ended his engagement to Elizabeth (Bessie) Moore, the daughter of Methodist Minister Henry Moore. Bessie later married Edwin P. Carter on 18 May 1911 at the Northcote Methodist Church, High Street, Northcote.

In 1907, Latham married schoolteacher Ella Tobin. They had three children, two of whom predeceased him. His wife, Ella, also predeceased him. Latham died in 1964 in the Melbourne suburb of Richmond.

He was also a prominent campaigner for Australian literature, being part of the editorial board of ''The Trident'', a small liberal journal, which was edited by Walter Murdoch. The board also included poet

Chief Justice of Australia

The chief justice of Australia is the presiding justice of the High Court of Australia and the highest-ranking judicial officer in the Commonwealth of Australia. The incumbent is Stephen Gageler, since 6 November 2023.

Constitutional basis

Th ...

, in office from 1935 to 1952. He had earlier served as Attorney-General of Australia

The attorney-general of Australia (AG), also known as the Commonwealth attorney-general, is the minister of state and chief law officer of the Commonwealth of Australia charged with overseeing federal legal affairs and public security as the ...

under Stanley Bruce and Joseph Lyons, and was Leader of the Opposition

The Leader of the Opposition is a title traditionally held by the leader of the Opposition (parliamentary), largest political party not in government, typical in countries utilizing the parliamentary system form of government. The leader of the ...

from 1929 to 1931 as the final leader of the Nationalist Party.

Latham was born in Melbourne

Melbourne ( , ; Boonwurrung language, Boonwurrung/ or ) is the List of Australian capital cities, capital and List of cities in Australia by population, most populous city of the States and territories of Australia, Australian state of Victori ...

. He studied arts and law at the University of Melbourne

The University of Melbourne (colloquially known as Melbourne University) is a public university, public research university located in Melbourne, Australia. Founded in 1853, it is Australia's second oldest university and the oldest in the state ...

, and was called to the bar

The call to the bar is a legal term of art in most common law jurisdictions where persons must be qualified to be allowed to argue in court on behalf of another party and are then said to have been "called to the bar" or to have received "call to ...

in 1904. He soon became one of Victoria's best known barristers. In 1917, Latham joined the Royal Australian Navy

The Royal Australian Navy (RAN) is the navy, naval branch of the Australian Defence Force (ADF). The professional head of the RAN is Chief of Navy (Australia), Chief of Navy (CN) Vice admiral (Australia), Vice Admiral Mark Hammond (admiral), Ma ...

as the head of its intelligence division. He served on the Australian delegation to the 1919 Paris Peace Conference, where he came into conflict with Prime Minister Billy Hughes

William Morris Hughes (25 September 1862 – 28 October 1952) was an Australian politician who served as the seventh prime minister of Australia from 1915 to 1923. He led the nation during World War I, and his influence on national politics s ...

. At the 1922 federal election, Latham was elected to parliament as an independent on an anti-Hughes platform. He got on better with Hughes' successor Stanley Bruce, and formally joined the Nationalist Party in 1925, subsequently winning promotion to cabinet as Attorney-General. He was also Minister for Industry from 1928, and was one of the architects of the unpopular industrial relations policy that contributed to the government's defeat at the 1929 election. Bruce lost his seat, and Latham was reluctantly persuaded to become Leader of the Opposition.

In 1931, Latham led the Nationalists into the new United Australia Party, joining with Joseph Lyons and other disaffected Labor MPs. Despite the Nationalists forming a larger proportion of the new party, he relinquished the leadership to Lyons, a better campaigner, thus becoming the first opposition leader to fail to contest a general election. In the Lyons government

The Lyons government was the federal executive government of Australia led by Prime Minister Joseph Lyons. It was made up of members of the United Australia Party in the Australian Parliament from January 1932 until the death of Joseph Lyons in ...

, Latham was the ''de facto'' deputy prime minister

A deputy prime minister or vice prime minister is, in some countries, a Minister (government), government minister who can take the position of acting prime minister when the prime minister is temporarily absent. The position is often likened to th ...

, serving both as Attorney-General and Minister for External Affairs. He retired from politics in 1934, and the following year was appointed to the High Court as Chief Justice. From 1940 to 1941, Latham took a leave of absence from the court to become the inaugural Australian Ambassador to Japan. He left office in 1952 after almost 17 years as Chief Justice; only Garfield Barwick has served for longer.

Early life

Latham was born on 26 August 1877 in Ascot Vale, Victoria, in the western suburbs ofMelbourne

Melbourne ( , ; Boonwurrung language, Boonwurrung/ or ) is the List of Australian capital cities, capital and List of cities in Australia by population, most populous city of the States and territories of Australia, Australian state of Victori ...

. He was the first of five children born to Janet (née Scott) and Thomas Edwin Latham. His mother was born in the Orkney Islands

Orkney (), also known as the Orkney Islands, is an archipelago off the north coast of mainland Scotland. The plural name the Orkneys is also sometimes used, but locals now consider it outdated. Part of the Northern Isles along with Shetland ...

of Scotland, while his father was Australian-born. His paternal grandfather, Thomas Latham, was an attorney's clerk who was transported to Australia as a convict

A convict is "a person found guilty of a crime and sentenced by a court" or "a person serving a sentence in prison". Convicts are often also known as "prisoners" or "inmates" or by the slang term "con", while a common label for former convicts ...

in 1848 for obtaining money under false pretences, and later worked as an accountant.

Latham's father was a tinsmith by profession, but "preferred benevolent work over a comfortable salary" and became a long-serving secretary of the Victorian Society for the Protection of Animals. The family moved to Ivanhoe

''Ivanhoe: A Romance'' ( ) by Walter Scott is a historical novel published in three volumes, in December 1819, as one of the Waverley novels. It marked a shift away from Scott's prior practice of setting stories in Scotland and in the more ...

in Melbourne's eastern suburbs shortly after Latham's birth. His father was also a justice of the peace and served on the Heidelberg Town Council in later life. Latham began his education at the George Street State School in Fitzroy. He subsequently won a scholarship to attend Scotch College, Melbourne

Scotch College is a private, Presbyterian day and boarding school for boys, located in Hawthorn, an inner-eastern suburb of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

The college was established in 1851 as The Melbourne Academy in a house in Spri ...

, and went on to graduate Bachelor of Arts from the University of Melbourne

The University of Melbourne (colloquially known as Melbourne University) is a public university, public research university located in Melbourne, Australia. Founded in 1853, it is Australia's second oldest university and the oldest in the state ...

in 1896.

After completing his undergraduate degree, Latham spent two years as a schoolteacher at a private academy in Hamilton, Victoria. He returned to the University of Melbourne to study law in 1899, where he also tutored in philosophy and logic at Ormond College. He was admitted to the Victorian Bar in 1904 but struggled for briefs in his first years as a barrister and primarily worked in the Court of Petty Sessions and County Court.

In 1907, Latham played a key role in establishing the Education Act Defence League, a rationalist organisation aimed at upholding the secular provisions of the '' Education Act 1872''. In 1909 he became the inaugural president of the Victorian Rationalist Association (VRA). He campaigned against the University of Melbourne's plans to open a divinity school.

World War I

In 1915, at the request of Thomas Bavin, Latham became secretary of the Victorian branch of the Universal Service League, an organisation supporting conscription for overseas service. In 1917 he joined the Australian Navy as head of Naval Intelligence, with the honorary rank of lieutenant commander. His appointment was prompted by complaints of sabotage in naval dockyards, while he later investigated allegations of Bolshevik activity in the Navy. Latham accompanied navy minister Joseph Cook to London in 1918, assisting him at Imperial War Cabinet meetings and later in his role on the Commission on Czechoslovak Affairs at the Versailles Peace Conference. He also served as an adviser to Prime MinisterBilly Hughes

William Morris Hughes (25 September 1862 – 28 October 1952) was an Australian politician who served as the seventh prime minister of Australia from 1915 to 1923. He led the nation during World War I, and his influence on national politics s ...

, but was "critical of his excesses and affronted by his manner" and "conceived an antipathy to Hughes that remained throughout his political career". For his services, Latham was appointed Companion of the Order of St Michael and St George

The Most Distinguished Order of Saint Michael and Saint George is a British order of chivalry founded on 28 April 1818 by George, Prince of Wales (the future King George IV), while he was acting as prince regent for his father, King George I ...

(CMG) in the 1920 New Year Honours.

Legal career

Latham had a distinguished career as a

Latham had a distinguished career as a barrister

A barrister is a type of lawyer in common law jurisdiction (area), jurisdictions. Barristers mostly specialise in courtroom advocacy and litigation. Their tasks include arguing cases in courts and tribunals, drafting legal pleadings, jurisprud ...

. He was admitted to the Victorian Bar in 1904, and was made a King's Counsel

A King's Counsel (Post-nominal letters, post-nominal initials KC) is a senior lawyer appointed by the monarch (or their Viceroy, viceregal representative) of some Commonwealth realms as a "Counsel learned in the law". When the reigning monarc ...

in 1922. In 1920, Latham appeared before the High Court representing the State of Victoria in the famous Engineers' case, alongside such people as Dr H.V. Evatt and Robert Menzies

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of '' Hruod'' () "fame, glory, honour, praise, reno ...

.

Politics

Early career

Latham was elected to theHouse of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entities. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often ...

at the 1922 federal election, standing as a self-described "Progressive Liberal" in the seat of Kooyong. He received the endorsement of the newly created Liberal Union, "a coalition of Nationalist Party defectors and people opposed to socialism and Hughes". He additionally received support from the conservative Australian Women's National League, the imperialist Australian Legion, and colleagues in Melbourne's legal profession. He did not fully accept the Liberal Union's platform, although he claimed to "strongly support the attitude of the Union", and issued his own platform consisting of nine principles including a slogan that "Hughes Must Go". At the election, Latham narrowly defeated the incumbent Nationalist MP Robert Best.

The 1922 election resulted in a hung parliament

A hung parliament is a term used in legislatures primarily under the Westminster system (typically employing Majoritarian representation, majoritarian electoral systems) to describe a situation in which no single political party or pre-existing ...

, with Latham siding with the Country Party to force Hughes' resignation as prime minister in favour of S. M. Bruce. While notionally remaining an independent, he soon announced his support for the new government and attended meetings of government parties. His early contributions in parliament concentrated on foreign affairs and the need for greater involvement of Australia and the other Dominion

A dominion was any of several largely self-governance, self-governing countries of the British Empire, once known collectively as the ''British Commonwealth of Nations''. Progressing from colonies, their degrees of self-governing colony, colon ...

s in developing imperial foreign policy.

Latham was re-elected at the 1925 election, standing as an endorsed Nationalist candidate in Kooyong. He subsequently joined Bruce's government as attorney-general

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general (: attorneys general) or attorney-general (AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have executive responsibility for law enf ...

. His major concerns in that role were "legislating against domestic communists and aligned interests, and reforming industrial arbitration law". Latham also served as a key advisor to Bruce on foreign affairs, accompanying him to the 1926 Imperial Conference

The 1926 Imperial Conference was the fifth Imperial Conference bringing together the prime ministers of the Dominions of the British Empire. It was held in London from 19 October to 23 November 1926. The conference was notable for producing the ...

in London. He was pleased with the Balfour Declaration on the constitutional status of Dominions which emerged from the conference, stating that it "embodies the most effective and useful work that any Imperial Conference has yet accomplished".

In 1929, Latham published ''Australia and the British Commonwealth'', a book detailing the evolution of the British Empire into the British Commonwealth of Nations and its implications for Australia.

Leader of the Opposition

After Bruce lost his Parliamentary seat in 1929, Latham was elected as leader of the Nationalist Party, and hence Leader of the Opposition. He opposed the ratification of the Statute of Westminster (1931) and worked very hard to prevent it. Two years later, Joseph Lyons led defectors from the Labor Party across the floor and merged them with the Nationalists to form the United Australia Party. Although the new party was dominated by former Nationalists, Latham agreed to become Deputy Leader of the Opposition under Lyons. It was believed having a former Labor man at the helm would present an image of national unity in the face of the economic crisis. Additionally, the affable Lyons was seen as much more electorally appealing than the aloof Latham, especially given that the UAP's primary goal was to win over natural Labor constituencies to what was still, at bottom, an upper- and middle-class conservative party. Future ALP leader Arthur Calwell wrote in his autobiography, ''Be Just and Fear Not,'' that by standing aside in favour of Lyons, Latham knew he was giving up a chance to become prime minister.Lyons government

The UAP won a huge victory in the 1931 election, and Latham was appointed Attorney-General once again. He also served as Minister for External Affairs and (unofficially) the

The UAP won a huge victory in the 1931 election, and Latham was appointed Attorney-General once again. He also served as Minister for External Affairs and (unofficially) the Deputy Prime Minister

A deputy prime minister or vice prime minister is, in some countries, a Minister (government), government minister who can take the position of acting prime minister when the prime minister is temporarily absent. The position is often likened to th ...

. Latham held these positions until 1934, when he retired from the Commonwealth Parliament. He was succeeded as member for Kooyong, Attorney-General and Minister of Industry by Menzies, who would go on to become Australia's longest-serving Prime Minister.

Latham became the first former Opposition Leader who was neither a former or future prime minister to become a minister and was the only person to hold this distinction until Bill Hayden in 1983.

As external affairs minister, Latham "judged the measured accommodation of Japan to be a priority in Australia’s approach to regional affairs". During the Manchurian Crisis

The Empire of Japan's Kwantung Army invaded the Manchuria region of the Republic of China on 18 September 1931, immediately following the Mukden incident, a false flag event staged by Japanese military personnel as a pretext to invade. At the ...

and subsequent Japanese invasion of Manchuria

The Empire of Japan's Kwantung Army invaded the Manchuria region of the Republic of China on 18 September 1931, immediately following the Mukden incident, a false flag event staged by Japanese military personnel as a pretext to invade. At the ...

, he and Lyons avoided making public statements on the matter and the government adopted a policy of non-alignment in the conflict. In meetings with Japanese foreign minister Kōki Hirota he unsuccessfully attempted to convince Japan to remain within the League of Nations

The League of Nations (LN or LoN; , SdN) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920), Paris Peace ...

.

In mid-1934, Latham led the Australian Eastern Mission to East Asia and South-East Asia, Australia's first diplomatic mission to Asia and outside of the British Empire. The mission, which visited seven territories but concentrated on China, Japan and the Dutch East Indies

The Dutch East Indies, also known as the Netherlands East Indies (; ), was a Dutch Empire, Dutch colony with territory mostly comprising the modern state of Indonesia, which Proclamation of Indonesian Independence, declared independence on 17 Au ...

(present-day Indonesia), has been identified as a milestone in the early development of Australian foreign policy. Latham publicly identified the mission as one of "friendship and goodwill", but also compiled a series of secret reports to cabinet on economic and strategic matters. He "actively sought information about trading opportunities across Asia, entering into frequent and detailed discussions with prime ministers, foreign ministers, premiers and governors about Australia‘s trading and commercial interests, custom duties and tariffs". On his return, Latham successfully advocated in cabinet for the appointment of trade commissioners in Asia, where previously Australia had been represented by British officials.

Chief Justice of Australia

Latham was appointed Chief Justice of the

Latham was appointed Chief Justice of the High Court of Australia

The High Court of Australia is the apex court of the Australian legal system. It exercises original and appellate jurisdiction on matters specified in the Constitution of Australia and supplementary legislation.

The High Court was establi ...

on 11 October 1935. From 1940 to 1941, he took leave from the Court and travelled to Tokyo to serve as Australia's first Minister to Japan. He retired from the High Court in April 1952, after a then-record 16 years in office.

As Chief Justice, Latham corresponded with political figures to an extent later writers have viewed as inappropriate. Latham offered advice on political matters – frequently unsolicited – to several prime ministers and other senior government figures. During World War II, he made a number of suggestions about defence and foreign policy, and provided John Curtin

John Curtin (8 January 1885 – 5 July 1945) was an Australian politician who served as the 14th prime minister of Australia from 1941 until his death in 1945. He held office as the leader of the Australian Labor Party (ALP), having been most ...

with a list of constitutional amendments he believed should be made to increase the federal government's power. Towards the end of his tenure, Latham's correspondence increasingly revealed his personal views on major political issues that had previously come before the court; namely, opposition to the Chifley government's health policies and support of the Menzies Government's attempt to ban the Communist Party. He advised Earle Page on how the government could amend the constitution to legally ban the Communist Party, and corresponded with his friend Richard Casey on ways to improve the Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world.

The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left. For example, while the political systems ...

's platform.

According to Fiona Wheeler, there was no direct evidence that Latham's political views interfered with his judicial reasoning, but "the mere appearance of partiality is enough for concern" and could have been difficult to refute if uncovered. She particularly singles out his correspondence with Casey as "an extraordinary display of political partisanship by a serving judge." Although Latham emphasised the need for secrecy to the recipients of his letters, he retained copies of most of them in his personal papers, apparently unconcerned that they could be discovered and analysed after his death. He rationalised his actions as those of a private individual, separate from his official position, and maintained a "Janus-like divide between his public and private persona". In other fora he took pains to demonstrate his independence, rejecting speaking engagements if he believed they could be construed as political statements. Nonetheless, "many instances of Latham's advising ..would today be regarded as clear affronts to basic standards of judicial independence

Judicial independence is the concept that the judiciary should be independent from the other branches of government. That is, courts should not be subject to improper influence from the other branches of government or from private or partisan inte ...

and propriety".

Latham was one of only eight justices of the High Court to have served in the Parliament of Australia prior to his appointment to the Court; the others were Edmund Barton, Richard O'Connor, Isaac Isaacs, H. B. Higgins, Edward McTiernan, Garfield Barwick, and Lionel Murphy.

Personal life

He was a prominent rationalist and atheist, after abandoning his parents' Methodism at university. It was at this time that he ended his engagement to Elizabeth (Bessie) Moore, the daughter of Methodist Minister Henry Moore. Bessie later married Edwin P. Carter on 18 May 1911 at the Northcote Methodist Church, High Street, Northcote.

In 1907, Latham married schoolteacher Ella Tobin. They had three children, two of whom predeceased him. His wife, Ella, also predeceased him. Latham died in 1964 in the Melbourne suburb of Richmond.

He was also a prominent campaigner for Australian literature, being part of the editorial board of ''The Trident'', a small liberal journal, which was edited by Walter Murdoch. The board also included poet

He was a prominent rationalist and atheist, after abandoning his parents' Methodism at university. It was at this time that he ended his engagement to Elizabeth (Bessie) Moore, the daughter of Methodist Minister Henry Moore. Bessie later married Edwin P. Carter on 18 May 1911 at the Northcote Methodist Church, High Street, Northcote.

In 1907, Latham married schoolteacher Ella Tobin. They had three children, two of whom predeceased him. His wife, Ella, also predeceased him. Latham died in 1964 in the Melbourne suburb of Richmond.

He was also a prominent campaigner for Australian literature, being part of the editorial board of ''The Trident'', a small liberal journal, which was edited by Walter Murdoch. The board also included poet Bernard O'Dowd

Bernard Patrick O'Dowd (11 April 1866 – 1 September 1953) was an Australian poet, activist, lawyer, and journalist. He worked for the Victorian colonial and state governments for almost 50 years, first as an assistant librarian at the Supreme ...

.

Latham was president of the Free library movement of Victoria from 1937 and served as president of the Library Association of Australia from 1950 to 1953. He was the first non-librarian to hold the position.

Legacy

TheCanberra

Canberra ( ; ) is the capital city of Australia. Founded following the Federation of Australia, federation of the colonies of Australia as the seat of government for the new nation, it is Australia's list of cities in Australia, largest in ...

suburb of Latham was named after him in 1971. There is also a lecture theatre named after him at The University of Melbourne.

Footnotes

References

* * * * * * *External links

{{DEFAULTSORT:Latham, John 1877 births 1964 deaths Lawyers from Melbourne Ambassadors of Australia to Japan Attorneys-general of Australia Australian Knights Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George Leaders of the opposition (Australia) Ministers for foreign affairs of Australia Australian members of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom Melbourne Law School alumni Nationalist Party of Australia members of the Parliament of Australia United Australia Party members of the Parliament of Australia Members of the Australian House of Representatives for Kooyong Members of the Australian House of Representatives Members of the Cabinet of Australia Royal Australian Navy officers Australian military personnel of World War I Chief justices of Australia Justices of the High Court of Australia People educated at Scotch College, Melbourne Australian lacrosse players Australian King's Counsel Australian atheists Judges from Melbourne Liberal Party (1922) members of the Parliament of Australia Leaders of the Nationalist Party of Australia Former Methodists Australian former Christians People from Ascot Vale, Victoria Australian MPs 1922–1925 Australian MPs 1925–1928 Australian MPs 1928–1929 Australian MPs 1931–1934 Australian MPs 1929–1931